Abstract

To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) combined with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) toward fatty liver disease. This cross-sectional study was conducted between October and November 2024 across multiple centers in the Chongqing region. Data collection and KAP score assessment were performed through questionnaire. The analysis included 477 valid questionnaires. The average knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 8.24 ± 5.05 (possible range: 0–18, 45.78%), 34.87 ± 2.93 (possible range: 9–45, 77.49%), and 32.02 ± 4.67 (possible range: 8–40, 80.05%), indicating poor knowledge, moderately positive attitudes, and relatively proactive practices. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that knowledge score (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.05–1.16), attitude score (OR = 1.27, 95% CI:1.16–1.39), body mass index (OR = 0.91,95% CI: 0.84–0.99), obesity/overweight (OR = 2.82, 95% CI: 1.60–4.97), diabetes (OR = 4.55, 95% CI: 2.14–9.70), hypertension (OR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.21–0.81), hyperlipidemia (OR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.17–0.73), hyperuricemia (OR = 3.00, 95% CI: 1.44–6.25), coronary heart disease (OR = 27.60, 95% CI:4.92–155), exercising (OR = 0.21–0.43, 95% CI:0.10–0.70) were independently associated with the practice scores. In the structural equation model, knowledge influenced attitude (β = 0.23, P < 0.001) and practices (β = 0.23, P < 0.001), and attitudes influenced practices (β = 0.41, P < 0.001). Patients with CHB and MAFLD display poor knowledge, positive attitudes, and proactive practices toward fatty liver. Although patients already demonstrated relatively proactive practices, further improvements could be achieved through education aimed at enhancing knowledge and attitudes. In clinical practice, healthcare providers should integrate structured patient education, such as individualized counseling during outpatient visits, educational materials on CHB–MAFLD interactions, and multidisciplinary lifestyle support including diet, exercise, and psychological guidance, into routine management. These targeted interventions could help close key knowledge gaps, strengthen attitudes, and reinforce sustainable health behaviors in this high-risk population.

Registry: Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, TRN: ChiCTR2400095024, Registration date: 31 December 2024.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global public health issue, with approximately 240 million people worldwide suffering from chronic hepatitis B (CHB)1 and around 800,000 deaths annually due to HBV-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1,2,3. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is characterized by hepatic steatosis with cardiometabolic dysfunction, and is associated with a spectrum ranging from mild steatosis to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma4. In recent years, the proportion of hepatitis B patients complicated with fatty liver has increased year by year with the increase of the proportion of obese population5, and MAFLD is associated with a higher risk of liver-related events and mortality. Patients with CHB combined with MAFLD are more prone to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC compared to those with CHB alone6. This comorbidity further complicates disease management and exacerbates liver injury6,7. Some studies suggest that HBV infection may have a protective effect against MAFLD development8,9, while others report that concurrent MAFLD may worsen outcomes in patients with CHB6,10, suggesting a complex interaction between the two conditions.

The treatment of CHB combined with MAFLD requires not only conventional antiviral therapy but also effective patient self-management. Indeed, although the management of CHB is mainly pharmacological, the management of MAFLD is mainly based on lifestyle habit changes, including diet, exercise, weight loss, eliminating alcohol consumption, and increasing coffee consumption11,12. Nevertheless, patients with MAFLD generally have poor lifestyle habits and insufficient disease management efficacy13,14. In addition, the proper self-management of CHB requires medication adherence and persistence, attending medical visits and examinations, and remaining vigilant regarding complications and signs of progression15. Available research on self-management and self-efficacy among patients with CHB or MAFLD remains limited16 and difficult to generalize to patients with CHB combined with MAFLD6. Thus, clinical intervention research targeting this population is lacking.

The knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) model is a widely used research framework in the healthcare field. It assesses individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning a specific health issue17,18. Through KAP studies, the knowledge level, attitudinal tendencies, and health behaviors of the target population can be understood, thereby aiding the development of targeted health education and intervention measures17,18. Few studies examined the KAP toward fatty liver disease19,20, and none in patients with CHB and MAFLD.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the current KAP of patients with CHB combined with MAFLD regarding fatty liver disease. The study could provide a foundation for developing targeted health education and clinical intervention strategies.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October and November 2024 across multiple centers in the Chongqing region, specifically in infectious disease or gastroenterology and hepatology departments of hospitals at or above the district level. The study participants were consecutively recruited outpatients in the relevant departments at each participating center. Research assistants screened and invited eligible patients during routine clinic visits based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients were informed about the study purpose, and informed consent was obtained prior to participation. All eligible patients who agreed to participate were included. To minimize selection bias, recruitment was carried out across various hospital levels and regions within Chongqing. The inclusion criteria were (1) 18–60 years of age, regardless of gender, (2) hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and/or HBV DNA positive for > 6 months, (3) diagnosed with hepatic steatosis through imaging or biopsy, along with at least one of the following conditions: (i) overweight/obesity, (ii) abnormal glucose tolerance/type 2 diabetes, and (iii) evidence of metabolic dysregulation (≥ 2 cardiovascular metabolic risk factors). The participants were excluded if they had pure fatty liver, pure hepatitis B, hepatitis B combined with other metabolic diseases, hepatitis B combined with non-metabolic-associated fatty liver from other hepatitis viruses, human immunodeficiency virus infection, autoimmune liver disease, drug-induced liver injury, Wilson’s disease, hyperthyroidism with liver injury, cardiogenic liver injury, genetic metabolic liver disease, or other factors leading to liver injury. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Army Medical University (approval #KY2024162) as the lead center, as well as by the committees of the participating centers. All participants were informed about the study protocol and provided written informed consent to participate in the study. I confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. While the sample was limited to the Chongqing region, the participating centers included both urban and rural areas and multiple hospital levels, which may enhance the generalizability to the broader CHB + MAFLD patient population in China. No patients were excluded due to cognitive or literacy limitations. When needed, trained research assistants provided assistance by reading the questionnaire items aloud and recording the participants’ responses objectively, without offering guidance or influencing their answers.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was designed based on the “Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B (2022 Edition)”21, the “Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic-Related (Non-Alcoholic) Fatty Liver Disease (2024 Edition)”22, the “Expert Consensus on Health Education for the Prevention and Control of Adult Metabolic Syndrome”, and the “Expert Consensus on Comprehensive Management of the Entire Population with Hepatitis B (2023)”, along with related literature. After initial drafting, the questionnaire was modified based on feedback from three senior experts in hepatology and public health. A pilot test was conducted with 44 participants to assess clarity and feasibility. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. In the pilot test with 44 participants, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.8756, indicating good reliability. The expert panel review and subsequent modifications were considered as evidence of content validity.

The final questionnaire, in Chinese (Supplementary material 1), consisted of four sections: demographic data (gender, age, education level, etc.), knowledge dimension, attitude dimension, and practices dimension. The knowledge dimension included nine questions, with scoring options of very well understood (2 points), heard of (1 point), and unclear (0 points), for a total possible score range of 0–18 points. The attitude dimension contained nine questions using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from very positive (5 points) to very negative (1 point), with a score range of 9–45 points. The practices dimension included eight questions, also using a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly agree (5 points) to strongly disagree (1), with a score range of 8–40 points. KAP scores < 60% were considered poor, scores of 60%-80% were considered moderate, and scores > 80% were considered good23,24. These cut-off values have been widely adopted in previous public health and behavioral KAP studies as general criteria to classify participants’ performance levels. Although these thresholds have been adopted from existing literature, their specific clinical implications for CHB + MAFLD patients have not been validated and should be interpreted cautiously.

Data collection and quality control

The principal investigator met the person in charge of each liver disease center during the 2024 Annual Meeting of Chongqing Infectious Liver Disease to present the study and enrollment criteria. Initially, 15 centers were invited, and five centers eventually participated. Ten research assistants who passed the GCP training participated in data collection, with at least one research assistant per participating center.

The questionnaires could be filled out electronically or on paper. The paper questionnaire was printed when needed. The electronic questionnaire was hosted on Sojump (http://www.sojump.com), an online survey platform. The questionnaire link was distributed to participants via a Quick Response (QR) Code or through a WeChat group. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaire on the spot at the hospital. The research assistants were available to answer questions about unclear statements or instructions but could not interfere or suggest responses. In the electronic questionnaire, the participants were required to click the option “I agree to participate in this study” at the beginning of the e-questionnaire to gain access to the questionnaire itself. For the paper questionnaire, the participants first completed the informed consent form before being handled the questionnaire.

All data were collected anonymously, and to prevent duplication, IP restriction was applied, allowing only one survey completion from a single IP address. The questionnaires were checked for consistency. Questionnaires with logic errors were excluded.

Sample size

The minimal sample size was estimated using Cochran’s sample size formula for survey studies25, \(\:n=\frac{{Z}^{2}\times\:p(1-p)}{{e}^{2}}\). Parameters were set a priori as follows: Z = 1.96 for a two-sided 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), p = 0.50 to maximize the required sample size under uncertainty, and margin of error e = 0.05. This yields n0 = 1.962 × 0.25/0.052 = 384.16, rounded to 385. Because the target outpatient population across participating centers was large, no finite population correction was applied. As the primary aim was to estimate KAP proportions with a prespecified precision rather than to test a specific hypothesis, an effect-size–based power calculation was not applicable to the primary outcome. Secondary analyses (e.g., logistic regression and SEM) were exploratory; no a priori power analysis was performed for these models. The final valid sample (n = 477) exceeded the minimum requirement.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed using STATA 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs), and categorical variables were presented as n (%). Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution were tested using t-tests or ANOVA. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between KAP dimensions. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to explore the influencing factors of practice scores. The total practice score ranged from 8 to 40 points. For logistic regression, the practice scores were dichotomized based on the percentage threshold: participants scoring >80% of the total possible score (i.e., >32 points out of 40) were classified as having “good” practices, while those scoring ≤32 points were classified as having “non-good” practices. A structural equation model (SEM) was established using AMOS 24.0 (IBM, NY, United States). Model fit was assessed using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean residual (SRMR), TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), and CFI (comparative fit index). Two-tailed P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

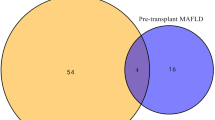

A total of 517 questionnaires were collected from five centers, but a total of 40 invalid questionnaires were excluded, including 6 patients younger than 18 years old, 2 patients with abnormal BMI and waist-to-hip ratio calculation data, 27 patients with abnormal options on demographic characteristics of item 5/12/17, and 5 patients who disagreed with this study. Ultimately, 477 valid questionnaires were included. In the formal survey, the Cronbach’s alpha for the entire questionnaire was calculated to be 0.889, further confirming the internal consistency of the instrument. Construct validity was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.899 (P<0.001). Among the 477 participants, 351 (73.58%) were male, age was 45.55 ± 10.37 years (range: 23–81), BMI was 25.80 ± 3.47 kg/m2, and the waist-to-hip ratio was 0.90 ± 0.16. Obesity or overweight was observed in 201 (42.14%) participants, while diabetes was reported in 55 (11.53%), hypertension in 76 (15.93%), hyperlipidemia in 60 (12.58%), hyperuricemia in 48 (10.06%), coronary heart disease in 11 (2.31%), and cerebral infarction in four (0.84%). The majority of the participants were living in urban areas (67.51%), has a vocational education or below (64.78%), were married (92.03%), had a non-medical employment (51.78%), had a monthly income of 2000–5000 CNY (38.36%), had CHB for > 5 years (41.51%), had MAFLD for > 5 years (22.43%), were not smoking (67.92%), were not drinking alcohol (75.47%), were not drinking sugary drinks (67.09%), had no family history of CHB (54.30%), had no family history of MAFLD (70.86%), and did not exercise (35.22%) (Tables 1 and 2).

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices

The average knowledge score was 8.24 ± 5.05 (/18, 45.78%), the average attitude score was 34.87 ± 2.93 (/45, 77.49%), and the average practice score was 32.02 ± 4.67 (/40, 80.05%), indicating poor knowledge, moderate attitudes, and proactive practices (Table 1). The knowledge scores were associated with gender (P = 0.002), diabetes (P = 0.037), coronary heart disease (P = 0.002), place of residence (P < 0.001), education level (P < 0.001), occupation (P = 0.002), income (P = 0.001), CHB duration (P < 0.001), MAFLD duration (P < 0.001), and exercise (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The items with the lowest rate of correct responses were K8 (16.56%; “Patients with hepatitis B and metabolic-associated fatty liver should rest during active hepatitis and exercise during the recovery phase.”), K4 (16.98%; “There is currently no specific drug to treat metabolic-associated fatty liver.”), and K6 (16.98%; “Hepatitis B and fatty liver can mutually accelerate liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer, working together in the progression of liver disease.”). The item with the highest level of understanding was K2 (41.51%; “Hepatitis B virus is hard to eliminate, and the disease is difficult to cure completely, but with proper treatment, it can be well-controlled long-term.”) (Table S1).

The attitude scores were associated with obese/overweight (P = 0.014), diabetes (P = 0.034), place of residence (P = 0.006), education level (P = 0.010), occupation P < 0.001), CHB duration (P = 0.049), MAFLD duration (P = 0.043), drinking sugary beverages (P = 0.001), family history of CHB (P = 0.017), family history of MAFLD (P = 0.001), and exercise (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The item with the poorest attitude was A7 (55.55%; “You are concerned that exercise might worsen your hepatitis B, so you are reluctant to exercise even with fatty liver.” (negative)), while the item with the most favorable attitude was A2 (96.86%; “You fully trust your doctor’s professional judgment regarding the treatment of hepatitis B and fatty liver.”) (Table S2).

The practice scores were associated with gender (P = 0.016), diabetes (P < 0.001), smoking (P = 0.007), drinking sugary beverages (P < 0.001), and exercise (P < 0.001) (Tables 1 and 2). The practice item with the poorest score was P8 (63.31%; “You take measures to manage stress when you feel pressured by your illness (e.g., talking with friends/family, seeking help from a therapist).”) while the item with the most proactive score was P6 (93.29%; “You regularly go to the hospital for check-ups, such as liver function tests.”) (Table S3).

Correlations

The knowledge scores were correlated to the attitude (r = 0.35, P < 0.001) and practices (r = 0.31, P < 0.001) scores. The attitude scores were correlated to the practice scores (r = 0.36, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

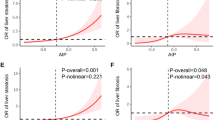

Multivariable analysis of practices

The knowledge scores (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.05–1.16, P < 0.001), attitude scores (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.16–1.39, P < 0.001), BMI (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84–0.99, P = 0.033), obesity/overweight (OR = 2.82, 95% CI: 1.60–4.97, P < 0.001), diabetes (OR = 4.55, 95% CI: 2.14–9.70, P < 0.001), hypertension (OR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.21–0.81, P = 0.010), hyperlipidemia (OR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.17–0.73, P = 0.005), hyperuricemia (OR = 3.00, 95% CI: 1.44–6.25, P = 0.003), coronary heart disease (OR = 27.60, 95% CI: 4.92–155, P < 0.001), exercising 3–4 times/week (OR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.10–0.45, P < 0.001), and not exercising (OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.26–0.70, P = 0.001) were independently associated with the practice scores (Table S4 and Fig. 1).

Structural equation modeling

The SEM analysis showed excellent fit, as shown by an RMSEA of 0, an SRMR of 0, a TLI of 1, and a CFI of 1 (Table S5). However, the model used in this study was a saturated model (i.e., degrees of freedom = 0), meaning the number of estimated parameters exactly equals the number of data points. As such, the model is just-identified and reproduces the data perfectly by definition. Consequently, fit indices such as RMSEA, CFI, and TLI are automatically set to values indicating perfect fit and should not be interpreted as evidence of substantive model quality. In this context, the primary focus should be on the estimated path coefficients, which provide information about the strength and direction of the relationships among knowledge, attitudes, and practices. In the SEM, knowledge influenced attitude (β = 0.23, P < 0.001) and practices (β = 0.23, P < 0.001), and attitudes influenced practices (β = 0.41, P < 0.001) (Table 4; Fig. 2). In the mediation analysis, knowledge directly influenced attitudes (β = 0.22, P < 0.001) and practices (β = 0.22, P < 0.001), attitudes directly influenced practices (β = 0.41, P < 0.001), and knowledge indirectly influenced practices (β = 0.09, P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

This cross-sectional multicenter study assessed the KAP of patients with CHB combined with MAFLD toward fatty liver disease. The results suggest that patients with CHB and MAFLD display poor knowledge but moderate attitudes and proactive practices toward fatty liver. Although patient practices were already relatively proactive, there remains room for improvement through enhanced knowledge and attitude-focused education.

No previous studies have examined the KAP of patients with CHB and MAFLD toward liver disease, but previous studies have examined the KAP of various populations toward fatty liver19,20. Fan et al. showed that Harbin (China) residents had poor knowledge of fatty liver, with only 32% of patients with MAFLD and 25% of the general population having adequate knowledge of fatty liver but a favorable attitude (90% and 85%); practices were lower in patients with MAFLD (49%) than in the normal population (71%). In Saudi Arabia, 45% of the participants from the general population had a poor knowledge of fatty liver, but 64% exhibited a favorable attitude19. Hegazy et al. revealed a moderate knowledge of MAFLD in Egypt despite a growing prevalence. A study of 5000 adults in New York (USA) showed that most were unaware of MAFLD. A study in Malaysia on the KAP toward liver diseases showed that about half of the participants had knowledge of HBV infection, and about a third had knowledge about fatty liver diseases20. Therefore, the poor knowledge observed in the present study is not surprising. It could be supposed that patients with MAFLD would be aware of their disease through discussions with their physicians or self-seeking information through curiosity, but it is not the case. Those results are supported by Fan et al., who also showed that the knowledge level of patients with MAFLD was not significantly different from the general population in Harbin. The present study revealed that all knowledge items would benefit from educational interventions, including the definition of CHB, the prognosis of CHB, the complications of MAFLD, the management of MAFLD, the manifestations of MAFLD combined with CHB, the interaction of CHB and MAFLD, the impact of body weight on MAFLD, the importance of exercise, and diet. Nevertheless, the participants displayed favorable attitudes, as supported by Fan et al., and proactive practices. These results suggest that participants were actively engaged in managing their condition, potentially contributing to better long-term outcomes, but also that they followed the instructions from their physicians without understanding them and that they were probably not really motivated with disease management, except living. This pattern suggests that their health behaviors may be less the result of internalized knowledge and more the outcome of external instruction. In China, particularly among patients with chronic diseases such as hepatitis B, physician guidance plays a central role in shaping health-related behavior due to patients’ limited health literacy and high trust in medical authority26,27. Rather than making informed decisions, patients may comply with recommendations during routine clinic visits, thus achieving good practices without a strong personal understanding of disease mechanisms. This underscores the need not only for more accessible health education, but also for improved communication strategies that help patients connect recommended behaviors with underlying medical reasoning. Indeed, the self-management of CHB and MAFLD involves adopting adequate lifestyle habits to prevent further liver damage and the progression of fatty liver11,12. Surprisingly, the present study showed that substantial proportions of the participants were still smoking and drinking alcohol and sugary beverages despite recommendations11,12. Smoking, alcohol, and sugary beverages are habits that are notoriously hard to break because they are usually associated with pleasure and reward28,29. It is possible that the patients want to keep pleasurable actions in their lives despite their disease. In addition, MAFLD has few physical manifestations, and the risk of progression to cirrhosis or HCC can be too abstract to encourage the patients to change their lifestyle habits. Additional studies should examine the reasons supporting the changes in lifestyle habits in patients with CHB and MAFLD. Nevertheless, as supported by the SEM, improving knowledge should also translate into better attitudes and practices. Education could take many forms, including pamphlets, posters, videos, public teaching, etc. Such educational programs should be designed and tested. Educational interventions should first address the major knowledge gaps identified in this study, but all knowledge about CHB and MAFLD should be covered. Improving patients’ knowledge may help enhance their practices, which in turn has the potential to contribute to better health management and clinical outcomes. Such interventions should be examined in the future. It could take the form of a longitudinal study in which the KAP could be assessed at enrollment, during, and after the educational intervention. If proven beneficial, such intervention could be exported to other centers.

The multivariable analysis showed that obesity/overweight, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and different levels of exercise frequency were significantly associated with practice scores. Interestingly, hypertension and hyperlipidemia showed negative associations, while obesity/overweight and diabetes were associated with relatively better practice scores. This contrast may reflect differences in symptom visibility, clinical management, and patient perception of disease urgency. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia are silent diseases without overt symptoms, and their management also involves changes in lifestyle habits30. Patients may underestimate their seriousness or delay lifestyle modification in the absence of symptoms. In contrast, conditions such as obesity and diabetes may receive more clinical attention and education due to their visibility and well-known health risks, which can lead to improved health awareness and adherence to self-management practices. This has been observed in intervention studies where health literacy efforts and exercise-based programs among diabetes patients in China resulted in better glycemic control and sustained self-care behaviors31. Moreover, disease-specific health literacy has been significantly associated with self-management behaviors, including medication adherence, among diabetic patients32. Taken together, these findings suggest that enhanced clinical engagement and targeted educational strategies may help explain the more proactive health practices observed among patients with obesity and diabetes. On the other hand, coronary heart disease can make an individual realize that life can be short, and hyperuricemia can manifest as gout, prompting patients to adopt a healthier lifestyle. The extremely high OR for coronary heart disease (27.60, 95% CI: 4.92–155) should be interpreted with caution. This result may be partly explained by the very small number of participants with coronary heart disease (n=11, 2.31%), which could have produced unstable estimates and wide confidence intervals. It is also possible that patients with coronary heart disease received more intensive health education and follow-up from clinicians, which may have promoted better practice behaviors. Nevertheless, this association should be interpreted carefully and validated in larger samples in future studies. Nevertheless, these results suggest that specific categories of patients might benefit more than others from educational and motivational interventions.

The strengths of this study included the relatively large sample size and the enrollment of patients from multiple centers. Still, the study also had limitations. The questionnaire was designed by the investigators. Although it was designed based on guidelines and the literature, it could be influenced by local practices, culture, and policies. In addition, while the sampling included both urban and rural centers within Chongqing, it was limited to a single geographic region. Therefore, generalizability to other regions or countries may be limited, and future studies should consider broader national or international samples. Additionally, although both paper-based and electronic questionnaires were used for data collection, the responses were anonymized and not marked by mode of administration. As a result, we could not assess whether the method of questionnaire delivery affected participant responses or data quality. Future studies may consider tracking questionnaire mode to explore its potential impact on response behavior or participation. The study was cross-sectional, preventing the analysis of causality. A SEM analysis was performed as a surrogate of causality, but such analysis must be taken cautiously since the causality is statistically inferred rather than observed33. In addition, no follow-up was performed to examine the changes in KAP in time. The study relied on self-reported data. A limited understanding of the disease concepts studied here could limit the participants’ capacity to understand the questions and reply adequately. At the same time, it is one of the aspects that KAP studies seek to evaluate. The clinical data were also self-reported, which could be affected by recall bias. Furthermore, all qualitative studies are at risk of social desirability bias, in which the participants can be tempted to answer what they know they should think or do instead of what they are actually thinking and doing34. Nevertheless, considering the poor knowledge scores, it is unlikely that the high practice scores were due to that bias. In addition, although recruitment involved multiple hospital levels, all participants were from a single region (Chongqing), which may limit the representativeness of the sample and introduce potential selection bias. These factors, together with the reliance on self-reported data, should be considered when interpreting the findings. Nevertheless, any bias in the KAP dimensions could affect the relationship among KAP dimensions. Another limitation is that the thresholds used to interpret KAP scores (< 60% = poor, 60–80% = moderate, ≥ 80% = good) were cited from the literature but have not been validated specifically in CHB + MAFLD patients. Therefore, their clinical meaningfulness for this population remains uncertain. Future studies should also include objective parameters and consider validating cutoff values in the target population.

In conclusion, patients with CHB and MAFLD display poor knowledge but moderate attitudes and proactive practices toward fatty liver. Although patients already demonstrated relatively proactive practices, further improvements could be achieved through patient education to improve knowledge and attitudes. In clinical practice, healthcare providers, especially hepatologists, infectious disease physicians, and nurses, should incorporate structured education into routine care for this population. Education could include individualized counseling during outpatient visits, printed or digital educational materials explaining the interaction of CHB and MAFLD, lifestyle modification workshops, and the establishment of multidisciplinary care teams (including dietitians, exercise specialists, and psychologists). Tailored interventions could focus on key knowledge gaps identified in this study, such as disease mechanisms, complications, and the importance of sustained exercise and dietary changes. Strengthening patient knowledge may not only improve attitudes and practices but also enhance long-term adherence to lifestyle and pharmacological management, ultimately improving clinical outcomes. Future studies should design educational activities and examine their effect on patients’ KAP.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Terrault NA et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 67, 1560–1599 (2018).

Szpakowski, J. L. & Tucker, L. Y. Causes of death in patients with hepatitis B: a natural history cohort study in the united States. Hepatology 58, 21–30 (2013).

Trepo, C., Chan, H. L., Lok, A. & Hepatitis B Virus Infect. Lancet 384, 2053–2063 (2014).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann. Hepatol. 29, 101133 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. MAFLD criteria May overlook a subtype of patient with steatohepatitis and significant fibrosis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 14, 3417–3425 (2021).

Huang, S. C. & Liu, C. J. Chronic hepatitis B with concurrent metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: challenges and perspectives. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, 320–331 (2023).

Hong, S. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of significant fibrosis in CHB patients with concurrent MASLD. Ann. Hepatol. 101589 (2024).

Cheng, Y. M., Hsieh, T. H., Wang, C. C. & Kao, J. H. Impact of HBV infection on clinical outcomes in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 5, 100836 (2023).

Liou, W. L. & Kumar, R. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis B: friends, foes or strangers. Digestive Med. Research 4, (2021).

van Kleef, L. A. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease increases risk of adverse outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. JHEP Rep. 3, 100350 (2021).

Tacke, F. et al. EASL–EASD–EASO clinical practice guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 81, 492–542 (2024).

Rinella, M. E. et al. AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 77, 1797–1835 (2023).

Attia, A., Labib, N. A., Abdelzaher, N. E. E., Musa, S. & Atef, M. Lifestyle determinants as predictor of severity of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). Egypt. Liver J. 13, 47 (2023).

Keating, S. E., Chawla, Y., De, A. & George, E. S. Lifestyle intervention for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: a 24-h integrated behavior perspective. Hepatol. Int. 18, 959–976 (2024).

Kong, L. N. et al. Self-management behaviors in adults with chronic hepatitis B: A structural equation model. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 116, 103382 (2021).

Ma, G. X. et al. Examining the influencing factors of chronic hepatitis B monitoring behaviors among Asian americans: application of the information-motivation-behavioral model. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, (2022).

Andrade, C., Menon, V., Ameen, S. & Kumar Praharaj, S. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in psychiatry: practical guidance. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 478–481 (2020).

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596176_eng.pdf. Accessed November 22, 20222008.

Someili, A. M. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and determinants of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among adults in Jazan province: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 16, e66837 (2024).

Mohamed, R., Yip, C. & Singh, S. Understanding the knowledge, awareness, and attitudes of the public towards liver diseases in Malaysia. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 742–752 (2023).

You, H. et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (version 2022). J. Clin. Transl Hepatol. 11, 1425–1442 (2023).

Chinese Society of Hepatology CMA. [Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated (non-alcoholic) fatty liver disease (Version 2024)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang. Bing Za Zhi. 32, 418–434 (2024).

Kaliyaperumal, K. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice. AECS Illumination. 4, 7–9 (2004).

Sitotaw, B. & Philipos, W. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) on antibiotic use and disposal ways in sidama region, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional survey. Sci. World J.. 8774634 (2023). (2023).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques 3rd edn (Wiley, 1977).

Liu, L., Qian, X., Chen, Z. & He, T. Health literacy and its effect on chronic disease prevention: evidence from china’s data. BMC Public. Health. 20, 690 (2020).

Lu, X. & Zhang, R. Impact of Physician-Patient communication in online health communities on patient compliance: Cross-Sectional questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e12891 (2019).

Botwright, S. et al. Which interventions for alcohol use should be included in a universal healthcare benefit package? An umbrella review of targeted interventions to address harmful drinking and dependence. BMC Public. Health. 23, 382 (2023).

Le Foll, B. et al. Tobacco and nicotine use. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 8, 19 (2022).

Rippe, J. M. Lifestyle strategies for risk factor reduction, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 13, 204–212 (2019).

Wei, Y. et al. Health literacy and exercise interventions on clinical outcomes in Chinese patients with diabetes: a propensity score-matched comparison. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care 8, (2020).

Yeh, J-Z. et al. Disease-specific health literacy, disease knowledge, and adherence behavior among patients with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan. BMC Public. Health. 18, 1062 (2018).

Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Fifth Edition) (The Guilford Press, 2023).

Bergen, N. & Labonte, R. Everything is perfect, and we have no problems: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huimin Liu, Xuqing Zhang, and Jie Xia carried out the studies, and Huimin Liu, Qian Li and Yongping Qiu participated in collecting data and drafted the manuscript. Huimin Liu, Lijian Ran, Yan Guo, Xin Lu, Maolan Fu, Lang Xiao and Hongli Deng participated in the acquisition and collecting data. Huimin Liu, Lang Xiao and Shilian Li participated in the analysis, interpretation of data, or performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital, Army Medical University, PLA [No:(A) KY2024162]. All participants were informed about the study protocol and provided written informed consent to participate in the study. I confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Qiu, Y., Xiao, L. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward fatty liver disease in patients with hepatitis B combined fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 15, 35448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19369-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19369-w