Abstract

Although basic activities of daily living (BADL) have been associated with quality of life in older adults, the differences in BADL between urban and rural residency in Central China are not fully clear. This study aimed to assess and compare the prevalence and influencing factors of BADL among older adults in urban versus rural areas. A cross-sectional on-site study among urban and rural older adults (≥ 60 years old) was conducted in Central China in 2022. Participants were included using multistage cluster random sampling. Sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyles, health conditions, and BADL were assessed using questionnaires. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify the factors associated with BADL. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to explore the association between urban versus rural older residency and BADL limitations. In total, 31,534 participants (81.76% from rural areas) were included, and the prevalence of BADL limitations was 12.30% (95% CI 11.94–12.67%). The urban participants (14.59%, 95% CI 13.68–15.50%) showed a significantly (P < 0.001) higher prevalence of BADL limitations than their rural counterparts (11.79%, 95% CI 11.39–12.18%). Living alone (aOR 1.420, 95% CI 1.288–1.567) and type 2 diabetes (aOR 1.146, 95% CI 1.025–1.281) were factors associated with BADL only among the rural participants. PSM analysis revealed a 6.06% difference in BADL limitations between the urban and rural participants. Older females showed a significantly (P < 0.05) higher prevalence of BADL limitations than older males in both rural and urban areas. In Central China, urban older adults had a higher prevalence of BADL limitations than their rural counterparts. There were differences in factors associated with BADL between urban versus rural older adults. BADL limitations affected more older females than males in both rural and urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population aging has changed the demographic structure worldwide and poses an unprecedented threat to global health1. Promoting healthy aging is widely recognized as one of the most cost-effective public health strategies for coping with this challenge2. Within this strategy, self-care ability deserves significant attention as it forms the foundation of mental health and social adaptability3. Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) are important components of self-care ability4. BADL limitations refer to the inability to perform daily life activities independently5. It has been identified as a significant threat to public health and healthy aging6. Moreover, the impact of BADL limitations on decreased quality of life in older people has been well-studied7,8.

Maintaining and improving BADL is a major concern in healthy aging. Exploration of factors associated with BADL in older people is a necessary step to achieve this goal9. According to previous studies, various factors have been associated with BADL, including lifestyles10, educational level11, economic conditions12, family structures13, and systemic or chronic diseases14. As research deepened, it has been gradually realized that the factors influencing BADL in older individuals might differ across different populations and countries15. Some studies have shown that socioeconomic factors and transportation facilities predominantly influence BADL in rural older people16, whereas urban areas are mainly affected by chronic diseases caused by over-industrialization17. However, such information is still unclear for urban and rural China. Additionally, there may be differences in the prevalence of BADL limitations between urban and rural older adults18. In India, rural older adults showed a lower level of BADL than those living in central urban areas16. In contrast, the rates of recovery from mild functional limitations in rural areas appear to be higher than those in urban areas19. In China, the result on BADL of older people differed across provinces20,21. However, studies are relatively lacking on the differences in BADL between urban and rural areas in China. These issues may affect the accurate formulation and implementation of policies, which may hinder the achievement of high-level healthy aging22. Therefore, to meet the challenges posed by population aging, it is crucial to address the threat of BADL in both urban and rural areas.

There are many obstacles to achieving healthy aging in China. One of the most prominent features is the urban-rural dual social structure, which signifies that artificial separation is set between urban and rural areas by household registration23. Under these circumstances, concerns have arisen that China’s urban-rural differences in many conditions may potentially impact BADL, such as education, cohabitation, impoverished households, and lifestyle24. Based on this, it was speculated that differences might exist in the prevalence and factors associated with BADL limitations between urban and rural older Chinese people. Therefore, this cross-sectional study was conducted with two objectives: (1) to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with BADL among urban and rural older adults in China, and (2) to analyze the association between rural versus urban residency and BADL limitations.

Methods

Procedures and study participants

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zhengzhou University, and the research content and process of this study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (ZZUIRB No. 2022-07). All participants were informed of the details of the study before participation, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A preliminary investigation that lasted 28 days in Henan Province, China, was conducted to estimate the sample size. A total of 14 local cooperating communities were included in the preliminary investigation using simple random sampling. The procedures, questionnaires and participant selection criteria were the same in the preliminary investigation and formal survey. Totally, 3245 older adults were included and BADL limitations affected 14.33% of them. The preliminary investigation showed that, after excluding the objective items, the KMO of the questionnaire was 0.969, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.932. The sample size was estimated using the following formula:

P represented the prevalence of BADL limitations from the preliminary investigation (P = 14.33%), α represented the Type I error probability (α = 0.05), and d represented the error margin (d = 0.01). To assume a 20% dropout rate, the sample size for the formal study was calculated to be 4717 × 120%≈5661.

The formal on-site questionnaire survey was conducted in Central China using multistage cluster random sampling between March and October 2022: First, Henan province was divided into central, eastern, western, southern, and northern regions based on geographical location. Second, in each region, 1/10 of the communities were randomly selected as sampling points for the survey. A total of 635 communities were included as sampling points (462 from rural areas, 72.76%). The community committees provided a list of local residents. The names of the residents were pre-numbered to protect their privacy. Based on this list, 5% of older adults were randomly selected at each sampling point. An additional 1% of older adults were subsequently included each time to reach sample size saturation, The invited older adults were notified through phone calls, home visits, or verbal contact.

Older adults were included if they were (1) ≥ 60 years old, (2) permanent residents (at least 2.5 years), and (3) conscious. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) less than 60 years (N = 726) and (2) uncooperative or unable to complete the survey due to communication disorders or psychological problems (N = 382). To ensure the representativeness of the sample, sample saturation monitoring was introduced. Saturation referred to the point at which the rate of BADL limitations no longer significantly changed as the sample size increased25. The sample began to saturate when the sample size reached 28,023. The investigation was concluded after two weeks. The participants were suggested to carry their ID cards and the latest physical examination or medical records. We also obtained cooperation from local primary health institutions to access participants’ health records with their authorization.

Assessments

The type of residence was identified based on the participants’ location and China’s administrative divisions, under which people were categorized into urban and rural residents. A detailed instruction of China’s administrative divisions is shown in Appendix. Specifically, there were several conditions to determine urban areas: (1) permanent residents > 2,000, (2) non-agricultural residents accounting for > 50%, (3) and the presence of residential, industrial, commercial, and administrative functions.

There are various tools available for assessing BADL in older adults, including the Katz Index and the Modified Barthel Index26. These tools typically focus on areas such as eating, toileting, dressing, bathing, and mobility. In China, the Assessment Form for Older Adults’ Basic Abilities of Daily Living is widely available, easy to use, culturally adapted, and reliable27. Therefore, it was used in this study to assess BADL dependency. There were 6 items: feeding, toileting, dressing, bathing, moving, and continence of defecation. For each item, choices were given as independent, assistance required, and fully dependent. Participants with all choices being “independent” were considered to have no BADL limitations, and those with one choice being “assistance required” or “fully dependent” were considered to have BADL limitations. During the assessment, participants were instructed to answer independently. Staff were allowed to provide non-directive semantic explanations. Communication with accompanying personnel only occurred when the participant expressed a need.

The following information was collected as covariates for analysis: (a) sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, cohabitation, and impoverished households; (b) lifestyles, including daily exercise, smoking, and alcohol intake; and (c) health condition, including body mass index, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, movement disorders, hearing impairment, cerebrovascular diseases, vascular diseases, heart diseases, and ocular diseases.

Age, gender, and ethnicity were based on the ID card. Poverty proof authorized by the County Civil Administration Department was used to identify impoverished households. The remaining sociodemographic information and lifestyle were based on self-reports. Health condition was based on physical examination results or electronic medical records, with self-reports used to provide supplementary information. This study has reached a collaboration with primary healthcare centers to access participants’ electronic medical records with their consent. Living with at least one person for at least five days per week was considered as “living with others” in cohabitation. Doing exercise more than 2.5 h per week for at least 6 months were considered as “Yes” in daily exercise, where the exercise was defined as brisk walking or activities with higher intensity28. At least one cigarette a day or at least drinking once a week for at least six months was considered as “Yes” in smoking or alcohol intake29,30. Body weight and height were measured on-site to calculate the body mass index. Movement disorders were assessed using a series of on-site tasks that the participants were required to complete independently, including sitting down and standing up, grasping and holding items, balancing and turning, bending, squatting, and rising. Those unable to complete were considered as “Yes” for movement disorders.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and proportions [n (%)]. Chi-square tests were conducted on total, urban, and rural samples to explore the differences between participants with and without BADL limitations, respectively. Variables with significance in one of these chi-square tests were included in the regression analysis. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to explore the factors associated with BADL limitations in urban versus rural participants. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted separately for urban and rural older people. Then, Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was used to reduce selection bias and balance observed covariates, since they did not randomize and were not blinded. The set of covariates included variables that were significant in the rural or urban multivariate logistic regression models. The samples were matched 1:1 without replacement (caliper = 0.05), and the propensity score (\(\:e\)) was calculated based on the logistic regression:

The distance metric is the propensity score difference in the Euclidean Distance. Cases with > 10% missing data or missing BADL information were excluded. Other missing data were handled using multiple imputations. STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of BADL limitations and characteristics among participants

In total, 32,167 older adults met the selection criteria and were invited. Among them, 202 individuals did not finish the BADL assessment, 352 withdrew from the questionnaire halfway, and 79 were excluded for missing data. Finally, 31,534 participants (81.76% from rural areas) were included in the study. A flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. In the total sample, there were 3380 cases with BADL limitations, with a prevalence of 12.30% (95%CI: 11.94%-12.67%). The prevalence of BADL limitations was significantly higher in the urban participants than their rural counterparts [(839/5751, 14.59%, 95%CI: 13.68%-15.50%) vs. (3041/25783 11.79%, 95%CI: 11.39%-12.18%), P < 0.001]. The risk ratio was 1.28 for urban older adults. Chi-square tests were conducted for the total sample, rural participants, and urban participants to analyze the differences in sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyles, and health conditions, as shown in Table 1.

Factors associated with BADL disability among urban and rural participants

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression showed that age, gender, educational level, impoverished households, daily exercise, alcohol intake, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, movement disorders, hearing impairment, cerebrovascular diseases, vascular diseases, and ocular diseases were factors associated with BADL limitations for both the urban and rural participants (all P < 0.05). Moreover, we discovered that living alone (aOR = 1.420, 95% CI: 1.288–1.567) and type 2 diabetes (aOR = 1.146, 95% CI:1.025–1.281) were factors associated with BADL limitations only for rural participants. These variables were included in the set of covariates for the subsequent matching. The univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 2.

Propensity score matching analysis

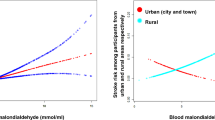

In total, 10,314 samples were matched using PSM from the 31,534 participants. After PSM, there were no statistically significant differences between the urban and rural participants for all covariates (P > 0.05). The PSM balance tests and Kernel Density Curves are shown in Appendix. After PSM, the prevalence of BADL limitations was still significantly higher in the urban samples than the rural participants (14.59% vs. 8.53%, P < 0.001). The difference was 6.06% and the risk ratio was 1.71 for the urban samples, as shown in Fig. 2. In addition, the prevalence of BADL limitations was significantly higher among females than males across age groups in both urban and rural participants (P < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence and factors associated with BADL limitations among urban and rural older people in Central China. Our findings indicated that BADL limitations affected 12.30% of the total sample, and the prevalence of BADL limitations was 14.59% and 11.79% for urban and rural participants, respectively. Monitoring the sample saturation enhanced the stability and representativeness of the results25. We used two separate regression models to select as many potential confounding variables as possible. PSM was used to reduce potential bias and more accurately compare the differences in BADL limitations between urban and rural older adults, thereby enhancing the reliability of the conclusions. The post-matching difference in BADL limitation rates between urban and rural participants increased from 2.80 to 6.06%, while the risk ratio increased from 1.28 to 1.71. Additionally, the BADL limitation rate was higher among females than males across age groups in both urban and rural participants.

A national study has shown that the standardized prevalence of self-care disability among adults aged 65 and older in China is approximately 10.91%31, similar to this study. This indicated that the BADL situation in Central China was comparable to the national average. The population, economic development level, and degree of industrialization in Central China are lower than in the Eastern region but higher than in the Western region. The per capita GDP in this region is also comparable to the national average. The region’s unique social exposure factors, such as urban-rural disparities, economic development level, and healthcare accessibility, are closely related. These factors are common across the country, leading to the similarity in the BADL limitation prevalence between Central China and the national average. A cohort study in Japan reported a baseline BADL impairment rate of 12.66%32, and this rate in Spain was 11.1%33, consistent with our findings. The reason might be that the extent of aging in these regions is similar, and their governments are committed to the expansion of social healthcare coverage, improving the accessibility of medical resources, and ensuring equitable distribution34. One study has pointed out that the prevalence of BADL limitations is higher among older adults in low- and middle-income countries35. However, the standardized data for cross-country comparisons is still insufficient.

Both the total sample and matching results indicated that the prevalence of BALD limitations among older adults was significantly higher in urban areas than rural areas. A previous study has concluded that there were significant socioeconomic differences between urban and rural China, which might be an important reason for the differences in physical function among older people6. Urban areas tend to have more sedentary lifestyles36, limited green spaces37, and more reliance on transportation for mobility38,39. In contrast, rural areas may have more opportunities for physical activity through daily chores, farming, and walking long distances40, which could contribute to better physical health among older rural adults. Moreover, rural communities often have tighter-knit social structures where older adults may receive more informal caregiving and support from family, friends, and neighbors41. This support can help mitigate limitations in daily activities. Urban areas, however, might have more fragmented social networks, potentially leading to fewer people helping older adults with daily tasks42. Due to population gathering and industrialization, urban areas are more affected by environmental pollution. which has been associated with poor psychological and physiological health43. These long-term health risks may lead to BADL limitations later in life. Moreover, the growth of the food industry has become more developed in urban China. Urban residents tend to consume higher amounts of processed foods rich in oil, sugar, and sodium. Such dietary habits increase the risk of metabolic syndrome and can, in turn, affect BADL44. In addition, there might be some regional characteristics in Central China: Population aging is severe while the economic development is moderate. This has led to a higher incidence of delayed retirement among older individuals in urban areas. Therefore, urban older adults might face greater lifestyle risks such as lack of exercise, as well as higher risks of chronic diseases. The rural participants in this study showed a lower prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia than the urban participants, which reinforced the aforementioned point. Most participants (81.76%) were from rural areas, which may influence the generalizability of the findings. The urban-rural differences in BADL limitations observed in Central China might be attributable to various factors such as geographic location, economic development, and population structure. These findings warrant further investigation to better understand the complex relationship between urbanization, aging, and functional limitations across regions.

There were more urban participants living alone or with type 2 diabetes than the rural participants. However, living alone and type 2 diabetes were associated with BADL limitations only in rural older adults, similar to the findings of a study in Shanghai45. This indicated that, although older adults in urban areas were more likely to have diabetes and live alone, these factors did not have a significant impact on BADL. Older living-alone people living alone generally lack social activities and interpersonal support. Urban areas offer better transportation, internet quality, and recreational activities. This can facilitate communication between older adults and their relatives, enabling them to receive support and enrich their lives. These resources may help alleviate the negative effects of living alone46. Medical resources are more developed in urban areas, and older urban adults may have easier access to healthcare services. It is also easier to provide rehabilitation facilities and assistive tools to meet the needs of older adults in urban areas. These can reduce the impact of chronic diseases and decrease the risk of daily accidents, such as falls, thereby helping maintain BADL. Therefore, we recommend that governments and primary health systems provide social and medical assistance to older rural people.

Lifestyles and health conditions were associated with BADL limitations. Alcohol intake can cause health problems such as liver function damage, nervous system damage, and cardiovascular diseases, which may affect BADL. A previous study showed that alcohol intake was associated with falls and injuries in older people, which can easily cause long-term BADL limitations47. Lack of exercise can lead to muscle weakness and atrophy, joint stiffness, decreases in heart and lung function, and osteoporosis, which are associated with decreased BADL48. Poor health conditions caused by various diseases can weaken physical function. As people age, a decline in compensatory abilities can exacerbate this impact and increase the risk of BADL limitations49. Based on this, we advocate focusing on promoting healthy lifestyles, and policymakers can guide social resources toward supporting healthy aging. Additionally, we discovered that females expressed more BADL limitations than males regardless of the type of residence and age group. The gap in healthy life expectancy between men and women can be attributed to various factors, including gender differences in health outcomes and the caregiving roles that women often assume. Women’s primary caregiving responsibilities might impact their own health and well-being. Cultural and social expectations often place pressure on women to prioritize the care of others, sometimes at the expense of their own health50. These factors contribute to the gender-based disparities in health, highlighting the need for more attention to the unique challenges faced by women in maintaining their health. Psychologically, females are more likely to face challenges in their mental health, such as depression and anxiety, which may affect the self-care ability and motivation of older females, which in turn can cause BADL limitations51. Biologically, there are physiological differences between females and males, such as relatively low bone density and muscle strength52. These biological differences may lead to greater challenges for older females in maintaining muscle strength, balance ability, and skeletal health, thereby increasing the risk of BADL limitations. Additionally, a meta-analysis revealed that sociocultural factors, including gender roles and social support, are important in causing gender differences in BADL limitation among older adults53.

This study had some limitations. First, some information was based on self-report. This might have caused recall and social desirability biases. Second, the cross-sectional design hindered the exploration of causal relationships. Therefore, we can only discover correlations between the variables. The explanations for the results also lacked direct data support. Third, the proportion of rural participants in our sample was much higher than that of urban participants. A possible reason might be that the population differences across communities were not considered when we randomly selected sampling points. The reliability of this study in exploring the prevalence and influencing factors of BADL disability in urban areas might be relatively low. Fourth, the participants were mainly from Central China, which decreased their representation. Rural areas such as Henan typically face challenges, including limited medical facilities and rehabilitation services. Therefore, this study may not fully reflect the conditions of rural areas in more developed regions, or the status of other health economic systems. Additionally, some covariates were defined based on research conventions, and the classification might not be entirely reliable. Although PSM reduced bias, it cannot handle all potential unobserved confounders. These issues are to be addressed through randomization.

Conclusions

The prevalence of BADL limitations among older adults in Central China is approximately 12.30%. Older urban residents showed a higher prevalence of BADL limitations than their rural counterparts. In both rural and urban areas, older women showed higher risks of BADL limitations than older men across age groups.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author Zeng Xi on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BADL:

-

Basic activities of daily living

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

References

Gong, J. et al. Nowcasting and forecasting the care needs of the older population in china: analysis of data from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Lancet Public. Health. 7 (12), e1005–e1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00203-1 (2022).

Chen, X. X. et al. The path to healthy ageing in china: a Peking University-Lancet commission. Lancet 400 (10367), 1967–2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X (2022).

Jaarsma, T., Riegel, B. & Strömberg, A. Self-care: a well-known but yet elusive concept. A discussion of theories, concepts, interventions, and measurement. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nur. 24 (1), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae124 (2025).

Zeng, H. et al. Reliability and validity of the geriatric Self-Care scale among Chinese older adults. Ann. Med. 57 (1), 2478480. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2025.2478480 (2025).

Mahoney, F. I. & Barthel, D. W. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Maryland State Med. J. 14, 61–65 (1965).

Guo, Y. et al. Prevalence of self-care disability among older adults in China. Bmc Geriatr. 22 (1), 775. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03412-w (2022).

Boccaccio, D. E., Cenzer, I. & Covinsky, K. E. Life satisfaction among older adults with impairment in activities of daily living. Age Ageing. 50 (6), 2047–2054. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab172 (2021).

Grassi, L. et al. Quality of life, level of functioning, and its relationship with mental and physical disorders in the elderly: results from the MentDis_ICF65 + study. Health Qual. Life Out. 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01310-6 (2020).

Chang, A. Y. et al. Measuring population ageing: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Public. Health. 4 (3), E159–E167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30019-2 (2019).

Sjölund, B. M. et al. Incidence of ADL disability in older persons, physical activities as a protective factor and the need for informal and formal Care - Results from the SNAC-N project. Plos One 10 (9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138901 (2015).

Ping, R. R. & Oshio, T. Education level as a predictor of the onset of health problems among China’s middle-aged population: Cox regression analysis. Front. Public. Health 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187336 (2023).

Liu, H. & Wang, M. Socioeconomic status and ADL disability of the older adults: cumulative health effects, social outcomes and impact mechanisms. Plos One. 17 (2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262808 (2022).

Nontarak, J. et al. The association of sociodemographic variables and unhealthy behaviors with limitations in activities of daily living among Thai older adults: Cross-sectional study and projected trends over the next 20 years. Asian/Pacific Island Nurs. J. 7, e42205. https://doi.org/10.2196/42205 (2023).

Zeng, H. et al. Influence of comorbidity of chronic diseases on basic activities of daily living among older adults in china: a propensity score-matched study. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1292289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1292289 (2024).

Sagari, A. et al. Causes of changes in basic activities of daily living in older adults with long-term care needs. Australas J. Ageing. 40 (1), E54–E61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12848 (2021).

Halder, M. et al. Functional disability and its associated factors among the elderly in rural India using LASI wave 1 data. J. Public. Health-Heid. 32 (6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01890-9 (2024).

Liu, H. Determining the effect of air quality on activities of daily living disability: using tracking survey data from 122 cities in China. Bmc Public. Health 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13240-7 (2022).

Li, Z. H. et al. Trends in the incidence of activities of daily living disability among Chinese older adults from 2002 to 2014. J. Gerontol. a-Biol. 75 (11), 2113–2118. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz221 (2020).

Hou, C. B. et al. Disability transitions and health expectancies among elderly people aged 65 years and over in china: A nationwide longitudinal study. Aging Dis. 10 (6), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2019.0121 (2019).

Lin, S. Functional disability among Middle-Aged and older adults in china: the intersecting roles of ethnicity, social class, and urban/rural residency. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 96 (3), 350–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150221092129 (2023).

Yan, Y. M. et al. Physical function, ADL, and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly: evidence from the CHARLS. Front. Public. Health 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1017689 (2023).

Hanlon, N. et al. Place integration through efforts to support healthy aging in resource frontier communities: the role of voluntary sector leadership. Health Place. 29, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.07.003 (2014).

Li, H. M. et al. Urban-rural disparities in the healthy ageing trajectory in china: a population-based study. Bmc Public. Health 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13757-x (2022).

Anand, S. et al. Health system reform in China 5 4 china’s human resources for health: quantity, quality, and distribution. Lancet 372 (9651), 1774–1781. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61363-X (2008).

Wu, J. et al. How urban versus rural residency relates to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A large-scale National Chinese study. Soc. Sci. Med. 320 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115695 (2023).

Pashmdarfard, M. & Azad, A. Assessment tools to evaluate activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in older adults: A systematic review. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran. 34, 33. https://doi.org/10.34171/mjiri.34.33 (2020).

Zhang, Y. C. et al. The activity of daily living (ADL) subgroups and health impairment among Chinese elderly: a latent profile analysis. Bmc Geriatr. 21 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01986-x (2021).

Aung, T. et al. Determinants of Health-Related quality of life among Community-Dwelling Thai older adults in Chiang mai, Northern Thailand. Risk Manag Healthc. P. 15, 1761–1774. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S370353 (2022).

Lee, S. J. et al. Health-Screening-Based chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its effect on cardiovascular disease risk. J. Clin. Med. 11 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113181 (2022).

Gutiérrez-Pliego, L. E. et al. Dietary patterns associated with body mass index (BMI) and lifestyle in Mexican adolescents. Bmc Public. Health 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3527-6 (2016).

Su, B. B. et al. Activities of daily Living-Related functional impairment among population aged 65 and Older-China, 2011–2050. China Cdc Wkly. 5 (27), 593–598. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2023.114 (2023).

Nagata, H. et al. Relationship of Higher-level functional capacity with Long-term mortality in Japanese older people: NIPPON DATA90. J. Epidemiol. 33 (3), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20210077 (2023).

Carmona-Torres, J. M. et al. Disability for basic and instrumental activities of daily living in older individuals. Plos One 14 (7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220157 (2019).

Bairoliya, N. & Miller, R. Social insurance, demographics, and rural-urban migration in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 91 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2020.103615 (2021).

Salinas-Rodríguez, A. et al. Severity levels of disability among older adults in Low- and Middle-Income countries: results from the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE). Front. Med-Lausanne 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.562963 (2020).

Wang, R. Y. et al. Is lifestyle a Bridge between urbanization and overweight in china?? Cities 99 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102616 (2020).

Lin, C. S. & Wu, L. F. Green and blue space availability and Self-Rated health among seniors in china: evidence from a National survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020545 (2021).

Zhu, Z. et al. Subjective well-being in china: how much does commuting matter? Transportation 46 (4), 1505–1524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-017-9848-1 (2019).

Zhu, W. F., Chi, A. P. & Sun, Y. L. Physical activity among older Chinese adults living in urban and rural areas: A review. J. Sport Health Sci. 5 (3), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.07.004 (2016).

Fan, J. X., Wen, M. & Kowaleski-Jones, L. Rural-Urban differences in objective and subjective measures of physical activity: findings from the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2003–2006. Prev. Chronic Dis. 11 https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.140189 (2014).

Xia, M., Lu, Z. Y. & Wang, F. Multi-Modal social media analytics: A sentiment Perception-Driven framework in Nanjing districts. Ieee Access. 13, 12603–12622. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3531769 (2025).

Wendt, A. et al. Rural-urban differences in physical activity and TV-viewing in Brazil. Rural Remote Health 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH6937 (2022).

Sumaira, S. H. Industrialization, energy consumption, and environmental pollution: evidence from South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut R. 30 (2), 4094–4102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22317-0 (2023).

Ivancovsky-Wajcman, D. et al. Ultra-processed food is associated with features of metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 41 (11), 2635–2645. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14996 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. W L, J D, An analysis of urban-rural difference of self-care ability of seniors-an empirical analysis based on CHARLS population. Development 28 (04), 129–142 (2022).

Burnette, D. et al. Living alone, social cohesion, and quality of life among older adults in rural and urban china: a conditional process analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 33 (5), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001210 (2021).

Hwang, J. S. & Kim, S. H. Severe ground fall injury associated with alcohol consumption in geriatric patients. Healthcare-Basel 10 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061111 (2022).

Cunningham, C. et al. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Spor. 30 (5), 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13616 (2020).

van der Vorst, A. et al. The impact of multidimensional frailty on dependency in activities of daily living and the moderating effects of protective factors. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 78, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.017 (2018).

Iseme-Ondiek, R. et al. The association between food production, food security, household consumer behaviour and waist-hip ratio amongst women in smallholder farming households in Kilifi county, Kenya. Nutr. Bull. 50 (1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12718 (2025).

Halliday, A. J., Kern, M. L. & Turnbull, D. A. Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Ment Health Phys. Act. 16, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.02.003 (2019).

Kim, K. M. et al. Longitudinal changes in muscle mass and strength, and bone mass in older adults: Gender-Specific associations between muscle and bone losses. J. Gerontol. a-Biol. 73 (8), 1062–1069. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx188 (2018).

Cappelli, M. et al. Social vulnerability underlying disability amongst older adults: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 50 (6), e13239. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13239 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants and collaborators.

Funding

The study was funded by National Key R&D Program for Active Health and Aging Science and Technology Response Key Special Project and Henan Provincial Department of Science and Technology Key R&D Special Project. The article process charge would be partially covered by The application-based research on the mechanism of action of Jichuan Decoction combined with acupuncture point embedding intervention in slow-transit constipation rats based on the “brain-gut-microbiome” axis and SCF/C-Kit signaling pathway (SKYD2023086).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen Zhang, Huizhen Sun, Mengxue Liu, Rui Wang, Xi ZengData curation: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen Zhang, Huizhen Sun, Mengxue Liu, Rui WangFormal analysis: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen ZhangFunding acquisition: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen ZhangInvestigation: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen Zhang, Huizhen Sun, Mengxue Liu, Rui Wang, Xi ZengMethodology: Rui Wang, Xi ZengProject administration: Xi ZengResources: Xi ZengSoftware: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen ZhangSupervision: Rui Wang, Xi ZengValidation: Xi ZengVisualization: Jiawei MiWriting—original draft: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen ZhangWriting—review & editing: Jiawei Mi, Renquan Zhu, Chen Zhang, Huizhen Sun, Mengxue Liu, Rui Wang, Xi Zeng.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

I have obtained written consent to publish from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mi, J., Zhu, R., Zhang, C. et al. How urban versus rural residency relates to basic activities of daily living among older people in Central China. Sci Rep 15, 35901 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19739-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19739-4