Abstract

Ultra-low-power active filters have received increasing attention in recent years due to emerging applications such as bio-signal sensing and wearable electronic devices, where they are employed in the analog front-end to eliminate interference noise. This paper presents a novel voltage-mode shadow universal filter based on multiple-input operational transconductance amplifiers (MI-OTAs). The multiple-input functionality of the OTA is implemented using the multiple-input bulk-driven MOS transistor (MIBD-MOST) technique, which enables low supply voltage operation and a wide input voltage swing. Additionally, the use of subthreshold operation contributes to the low-power consumption of the OTA. The proposed shadow filter is implemented using a voltage-mode universal filter, in which the low-pass section is employed to control the natural frequency through an external amplifier. The proposed filter provides both non-inverting and inverting transfer functions of low-pass filter (LPF), high-pass filter (HPF), band-pass filter (BPF), band-stop filter (BSF), and all-pass filter (APF). The circuit was designed and simulated using Cadence Virtuoso, utilizing TSMC’s 65-nm 1P9M CMOS technology. The total silicon area of the MI-OTA measured 148 μm × 89 μm. Operating at a supply voltage of 0.5 V and a cutoff frequency of 31.2 Hz, the filter achieved an overall power consumption of 350 nW. Experimental validation was conducted using a prototype implemented with commercially available LM13700N integrated circuits, confirming the filter’s functionality and effectiveness. The proposed design is well suited for low-voltage, low-power applications, particularly low-frequency bio-signal processing such as EEG and EGG acquisition systems, as well as sensor interface systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shadow filters are a technique used to control key parameters such as the natural frequency and quality factor of second-order filters–namely, low-pass (LPF), high-pass (HPF), and band-pass filters (BPF)–through the use of external amplifiers1,2,3. Typically, conventional second-order filters control the natural frequency and quality factor through internal parameters used in their realization, such as transconductance, parasitic resistance, resistors, and capacitors4,5,6,7,8. However, varying these active or passive component values can adversely affect filter performance, including dynamic range, linearity, and operating frequency. To mitigate these effects, shadow filters adjust the natural frequency and quality factor using external parameters, such as amplifiers or attenuators. Consequently, the ideal performance characteristics of the original second-order filters are preserved.

Numerous shadow filters and other types of agile filters have been proposed in the literature9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Various circuit topologies implement these filters using different active devices, including current conveyors (CC)9, current backward transconductance amplifiers (CBTA)10, current-feedback operational amplifiers (CFOA)11,12, operational floating current conveyors (OFCC)12, and operational trans-resistance amplifiers (OTRA)14. However, shadow filters based on these active devices generally lack electronic tuning capabilities.

To address this limitation, various circuit topologies have been proposed that implement shadow filters using electronically tunable active elements such as current-controlled conveyors15,16, current conveyor cascaded transconductance amplifier (CCCTA)17,18, current differencing transconductance amplifiers (CDTA)19,20,21,22,23, differential current conveyor cascaded transconductance amplifier (DCCCTA)24, differential difference transconductance amplifiers (DDTA)25,26,27, operational transconductance amplifiers (OTA)28,29, voltage differencing differential difference amplifiers (VDDDA)30, voltage differencing gain amplifiers (VDGA)31, voltage differencing transconductance amplifiers (VDTA)32,33,34,35,36.

These shadow filters offer electronic tuning capability; however, they still exhibit several drawbacks. First, most of them do not provide all five standard filtering functions–LPF, HPF, BPF, BSP, and APF–within a single topology9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,19,20,21,22,26,28,31,32,33,34,35,36. Second, tuning the natural frequency or quality factor using external amplifiers often affects the passband gain of the filter responses9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36. Although the shadow filters presented in27,29 introduce techniques for passband gain compensation without requiring manual adjustment, none of the existing designs can provide both inverting and non-inverting transfer functions for LPF, HPF, BPF, BSP, and APF within a single unified topology.

Filters play a crucial role in various system applications by suppressing out-of-band high-frequency components and defining the effective bandwidth, with applications in optical communications37 and telecommunications38,39,40,41. This work specifically addresses filters for low-frequency applications, such as bio-signal processing. Consequently, the filter design must operate with low supply voltage and low power consumption.

Operational transconductance amplifiers (OTAs) are fundamental active elements commonly used in the realization of analog signal processing circuits. They offer several advantages, including electronic tunability and a simple structure that facilitates implementation using either bipolar junction transistor (BJT) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technologies with the same basic configuration. Moreover, OTA-based circuits typically require a minimal number of passive resistors, making them well-suited for integrated circuit (IC) implementation. Several discrete-component OTA integrated circuits (ICs), such as the CA3080, LM13600, and LM13700, are commercially available. These OTAs can be configured to realize multiple-input OTA structures by appropriately connecting their output terminals, and multiple-output OTA structures by suitably connecting their input terminals.

This paper presents a novel shadow universal filter based on multiple-input operational transconductance amplifiers (MI-OTAs). The multiple-input of the OTA is realized using the multiple-input bulk-driven MOS transistor (MIBD-MOST) technique. Owing to the multiple-input structure, the proposed filter topology can simultaneously provide both inverting and non-inverting transfer functions for five standard responses: LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF, within a single configuration. In this work, a low-pass filter-controlled shadow universal filter is implemented, where the natural frequency of the filters can be electronically tuned via an external amplifier. Furthermore, variations in the natural frequency do not affect the passband gain, as it is automatically compensated, ensuring consistent filter performance. The proposed circuit was designed and simulated using Cadence Virtuoso with TSMC 65-nm 1P9M CMOS technology at a supply voltage of 0.5 V. Its functionality and effectiveness were further verified experimentally using a prototype implemented with commercially available LM13700N integrated circuits. The proposed design is well-suited for low-voltage, low-power applications, particularly in low-frequency biosignal processing and sensor interface systems.

The paper is organized as follows: “Proposed circuit” presents the MI-OTA structure realized using the MIBD-MOST technique, the proposed universal filters, the shadow universal filter, and the non-ideality analysis. “Results” discusses the simulation results of the MI-OTA and the proposed universal filters, along with their experimental verification. Finally, “Conclusions” concludes the paper.

Proposed circuit

Multiple-input operational transconductance amplifier

The symbolic representation of the proposed MI-OTA with three inputs is depicted in Fig. 1 (a). Ideally, its current-voltage behavior can be described by the following expression:

Here, \(\:{I}_{o}\) denotes the output current, \(\:{g}_{m}\) is the transconductance, and \(\:{V}_{+}\), \(\:{V}_{-}\) correspond to the non-inverting and inverting input voltages, respectively. As evident from Eq. (1), the output current is directly related to the differential sum of voltages applied across the OTA’s input terminals.

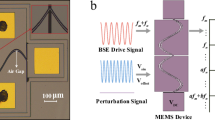

Figure 1(b) illustrates the conventional approach for realizing a multiple-input OTA, which requires multiple transconductors with their outputs connected together. This method results in increased chip area, higher power consumption, and greater design complexity compared to the proposed MI-OTA, which utilizes a single core OTA, with multiple inputs achieved through passive components, as explained later.

Figure 2 shows the CMOS implementation of the MI-OTA tailored for the target application. The proposed design employs a current-mirror OTA topology with input stage linearization (M1, M2, M11, M12) based on the Krummenacher–Joehl technique42. This linearization approach has been modified for use with bulk-driven (BD) MOSFETs operating in the subthreshold region, allowing for effective operation at reduced supply voltages and power levels. Transistors M11 and M12, biased in the triode region, combine with M1 and M2 to form a linearized differential input pair, which is in turn biased via current sources M7/7c and M8/8c.

The remaining transistors in the circuit are configured as self-cascode (SC) structures—specifically, (M3/3c) through (M10/10c), and (M13/13c)—to enhance output resistance and thereby increase voltage gain. The circuit’s multiple-input capability is achieved using capacitive voltage dividers (\(\:{C}_{B}\)) at the input, a technique that incurs no additional power consumption43,44. These capacitors are paired with high-value resistances, implemented using MOS transistors (MR) biased in cutoff mode with their gate and source terminals shorted (i.e., \(\:{V}_{GS}\) = 0), to establish appropriate DC biasing.

While similar OTA topologies have previously been fabricated using 0.18 μm CMOS technology44, the current design leverages 65 nm process capabilities. Specifically, the SC structures incorporate low-threshold voltage (LVT) transistors (\(\:{V}_{TH}\)=+266/-268 mV) as cascode devices and standard-threshold transistors (\(\:{V}_{TH}\)=410/-406mV) as main devices45. This choice ensures that the lower transistors in the SC pairs operate with a drain-source voltage (\(\:{V}_{DS}\)) around 100 mV, positioning them at the boundary between saturation and linear regions–closely resembling traditional cascode operation. This technique helps counteract the inherently low intrinsic gain of 65 nm BD MOSFETs, which is further reduced by the capacitive divider at the input.

The large-signal quasi-static current-voltage characteristic of one input pair (\(\:{V}_{i+}\), \(\:{V}_{i-}\), \(\:i\) =1, 2, 3) (with the other grounded) is expressed as44:

In this equation:

\(\:{n}_{p}\) is the subthreshold slope factor for PMOS,

\(\:{U}_{T}\) is the thermal voltage,

\(\:\eta\:=\left({n}_{p}-1\right)={g}_{mb(\text{M}1,\text{M}2)}/{g}_{m(\text{M}1,\text{M}2)}\), where \(\:{g}_{mb(\text{M}1,\text{M}2)}\) and \(\:{g}_{m(\text{M}1,\text{M}2)}\), are the bulk and gate transconductance of the transistors M1 and M2, respectively.

\(\:m\) = (W11/L12)/(W1/L1) represents the aspect ratio between matched transistor pairs M11/12 and M1/2,

\(\:\beta\:\) is the voltage gain from the capacitive divider, approximately 0.33 for identical \(\:{C}_{B}\) capacitors under ideal conditions.

For optimal linearity, \(\:m\) should be set to 0.5, consistent with gate-driven OTA input stages operating in weak inversion46.

From Eq. (2), the small-signal transconductance of the MI-OTA is given by:

Substituting \(\:\beta\:\) =0.33 and \(\:m\) =0.5 this simplifies to:

This shows that \(\:{g}_{m}\) is linearly dependent on the bias current \(\:{I}_{set}\). The low-frequency voltage gain is given by:

with output resistance:

The SC topology substantially increases the output resistance and, thus, the gain–especially when both transistors in each SC pair are biased near the saturation threshold. While the capacitive voltage divider does increase the input-referred noise, the input signal amplitude is proportionally increased by the same ratio, resulting in an unchanged dynamic range (DR). The main advantage of this design is that it maintains a high DR despite operating at very low supply voltages–an achievement made possible by techniques such as multiple-input OTA and bulk-driven operation. The detailed noise performance of this OTA topology can be found in44.

Proposed universal filter

The proposed universal filter based on MI-OTAs is illustrated in Fig. 3 (a), with its corresponding circuit symbol shown in Fig. 3 (b). The terminals \(\:{V}_{1}\), \(\:{V}_{2}\), and \(\:{V}_{3}\) serve as input voltage nodes, while \(\:{V}_{o1}\), \(\:{V}_{o2}\), \(\:{V}_{o3}\), \(\:{V}_{o4}\), and \(\:{V}_{o5}\) represent the output voltage nodes. By appropriately applying the input voltages \(\:{V}_{1}\) and \(\:{V}_{2}\), both non-inverting and inverting transfer functions of LPF, HPF, BPF, BSP, and APF can be realized. The output voltages of these filtering functions can be expressed as

The realization of various filtering functions is summarized in Table 1. In this configuration, terminal \(\:{V}_{3}\) is not utilized and is reserved for potential use in shadow filter applications.

.

The natural frequency (\(\:{\omega\:}_{o}\)) and the quality factor (\(\:Q\)) of universal filter can be given by

The natural frequency can be controlled by \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\), specifically when \(\:{g}_{m1}\)=\(\:{g}_{m2}\),while the quality factor is determined by the ratio \(\:{C}_{1}/{C}_{2}\).

Proposed shadow universal filter

The basic shadow filter configuration, shown in Fig. 4(a)1, is adopted to implement the proposed shadow filter. The general block diagram of a shadow filter consists of a universal filter, which serves as the core of the circuit. This universal filter has outputs for various filter responses, such as low-pass (LP), high-pass (HP), and band-pass (BP). A summing circuit, which combines the input signal with the feedback signal. An external amplifier, which amplifies the output of one of the core filter’s stages (e.g., the low-pass output) before feeding it back to the summing circuit. This design is based on an LPF-controlled shadow filter, where the output voltage of the LPF is amplified and fed back to be summed with the input voltage. The natural frequency of second-order filters, such as the LPF and BPF, can be tuned by adjusting the gain of an external amplifier \(\:A\).

The proposed shadow universal filter is shown in Fig. 4(b), where the second-order filter block in Fig. 4(a) is replaced by the universal filter configuration presented in Fig. 3. The amplifier is realized using transconductance \(\:{g}_{mA}\) and a resistor \(\:{R}_{1}\). The voltage \(\:{V}_{o1}\) from the LPF is amplified by a factor of \(\:{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) and the resulting signal is fed back to terminal \(\:{V}_{3}\). The non-inverting and inverting filtering functions of the LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF in the shadow filter configuration can be realized by appropriately applying input voltages \(\:{V}_{in1}\) and \(\:{V}_{in2}\).

The LPF obtained at terminal \(\:{V}_{LPF}\). Its natural frequency can be tuned by a factor of \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\). However, adjusting the natural frequency also affects the passband gain of the LPF. To compensate for the passband gain, the voltages \(\:{V}_{in3}\) and \(\:{V}_{in4}\) are appropriately applied by input signal. Consequently, the inverting LPF configuration can be achieved by setting \(\:{V}_{in1}\)=\(\:{V}_{in3}\)=\(\:{V}_{in}\), while the non-inverting LPF configuration is realized by setting \(\:{V}_{in2}\)=\(\:{V}_{in4}\)=\(\:{V}_{in}\). All unused inputs should be properly grounded. The output voltage \(\:{V}_{LPF}\) can be expressed as

The HPF and BPF can be obtained at terminals \(\:{V}_{HPF}\) and \(\:{V}_{BPF}\), respectively. The non-inverting filtering function is obtained by applying the input voltage to \(\:{V}_{in1}\) while the inverting filtering function is obtained by applying the input voltage to \(\:{V}_{in2}\). In this case, adjusting the natural frequency by a factor of \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) does not affect the passband gain. Therefore, the inputs \(\:{V}_{in3}\), \(\:{V}_{in4}\), \(\:{V}_{in5}\) are not utilized and are connected to ground. The output voltages \(\:{V}_{HPF}\) and \(\:{V}_{BPF}\) can be expressed, respectively, as

The BSF and APF are obtained at terminals \(\:{V}_{BSF}\) and \(\:{V}_{APF}\), respectively. In the LPF case, the passband gain is compensated to its nominal value by a factor of \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\). However, this factor also increases the passband gain in the frequency range above the natural frequency, which corresponds to the HPF section. Therefore, to reduce the passband gain in the frequency range above the natural frequency to nominal value, the input \(\:{V}_{in5}\) is connected to \(\:{V}_{o2}\). The non-inverting BSF configuration can be achieved by setting \(\:{V}_{in1}\)=\(\:{V}_{in3}\)=\(\:{V}_{in}\), while the inverting LPF configuration is realized by setting \(\:{V}_{in2}\) = \(\:{V}_{in4}\) = \(\:{V}_{in}\). The output voltages \(\:{V}_{BSF}\) and \(\:{V}_{APF}\) can be given respectively as

In the cases of the BSP and APF, the factor \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) does not influence the tuning of the natural frequency; instead, it serves to adjust the quality factor. However, modifying the quality factor may lead to an increased peak at the natural frequency of the APF due to the asymmetry introduced by the middle terms in the numerator and denominator of (18).

The realization of various filtering functions is summarized in Table 2. It can be observed that the proposed shadow filter provides both inverting and non-inverting responses for LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF functions through appropriate application of the input signal. Furthermore, the passband gain of each filter can be compensated to achieve normalized gain levels.

The natural frequency (\(\:{\omega\:}_{os1}\)) and quality factor (\(\:{Q}_{s1}\)) of the LPF, HPF, and BPF can be given by

The parameter \(\:{\omega\:}_{os1}\) of the LPF, HPF, and BPF can be tuned by the factor \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\); however, any adjustment to this factor simultaneously alters the value of \(\:{Q}_{s1}\). To mitigate this effect, it is necessary to adjust the bias currents to achieve an appropriate ratio of \(\:{g}_{m2}/{g}_{m1}\).

The natural frequency (\(\:{\omega\:}_{os2}\)) and quality factor (\(\:{Q}_{s2}\)) of BSF and APF can be expressed by

Here, the factor \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) can be used to tune the parameter \(\:{Q}_{s2}\) of the BSF and APF without affecting the parameters \(\:{\omega\:}_{os2}\).

Non-idealities analysis

In the first case, since the circuit operates at low frequencies, the parasitic parameters of the MI-OTA, such as resistance and capacitances, can be neglected in the non-ideal analysis. Consequently, only the non-ideal behavior of the OTA transconductance is considered.

Near the cutoff frequency, the non-ideal transconductance \(\:{g}_{mn}\) of the MI-OTA can be expressed as follows47:

where \(\:{T}_{o}=1/{\omega\:}_{gm}\) and \(\:{\omega\:}_{gm}\) represents the first pole frequency of \(\:{g}_{m}\).

Considering the non-idealities in (22) for \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\) (while neglecting \(\:{g}_{m3}\), \(\:{g}_{m4}\), \(\:{g}_{m5}\), and \(\:{g}_{mA}\)), the non-idealities can be approximated as \(\:{g}_{mn1}\left(s\right)\cong\:{g}_{m1}\left(1-{T}_{o1}s\right)\) and \(\:{g}_{mn2}\left(s\right)\cong\:{g}_{m2}\left(1-{T}_{o2}s\right)\), and the denominator \(\:{D\left(s\right)}_{1}\) of transfer functions can be then written as follows:

The denominator \(\:{D\left(s\right)}_{2}\) of transfer functions can be then written as

These conditions can be achieved by appropriately selecting the values of \(\:{g}_{m1}\), \(\:{g}_{m2}\), and the capacitances \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) to establish large time constants that significantly exceed the smaller time constants associated with non-ideal effects.

In the second case, when the circuit operates at high frequencies, the parasitic parameters of the MI-OTA, such as resistances, capacitances, are included in the non-ideal analysis. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the output parasitic impedances of \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\) affect the natural frequency of filter. Specifically, the output parasitic capacitances of \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\) are denoted as \(\:{C}_{o1}\) and \(\:{C}_{o2}\), respectively, while the output parasitic resistances are denoted as \(\:{R}_{o1}\) and \(\:{R}_{o2}\).

When the parasitic capacitances \(\:{C}_{o1}\) and \(\:{C}_{o2}\) are taken into account, \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) become \(\:{C}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\) = \(\:{C}_{1}+{C}_{o1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\) = \(\:{C}_{2}+{C}_{o2}\), respectively. Consequently, the pole frequencies of filter are given by \(\:{g}_{m1}/{C}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\), \(\:{g}_{m2}/{C}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\), \(\:1/\left({R}_{o1}{C}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\), and \(\:1/\left({R}_{o2}{C}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\). Therefore, in high-frequency response, the pole frequencies \(\:{g}_{m1}/{C}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}/{C}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\) determine the filter’s cut-off frequency, as the pole frequencies associated with \(\:1/{R}_{o1}{C}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:1/{R}_{o2}{C}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\) lie at much higher frequency. However, the parasitic capacitances \(\:{C}_{o1}\) and \(\:{C}_{o2}\) cause a deviation in the filter’s natural frequency. This effect can be compensated by adjusting \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\), or mitigated by choosing \(\:{C}_{1}\gg\:{C}_{o1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\gg\:{C}_{o2}\).

Results

Post-layout simulation result

The circuit was designed and simulated using Cadence Virtuoso, employing the TSMC 65-nm 1P9M CMOS technology. A supply voltage of 0.5 V (± 0.25 V) was used. The key transistor sizing parameters utilized in the design are provided in Table 3. Figure 5 shows the layout of the three-input OTA, with a total silicon area of 148 μm × 89 μm. Owing to the compact CMOS structure and operation in the low-frequency range, the pre-layout and post-layout simulation results exhibit good agreement.

Figure 6(a) presents the transient responses of the MI-OTA with \(\:{I}_{set}\) = 7 nA for various input voltage amplitudes under a 1 kHz sinusoidal excitation, while Fig. 6(b) illustrates the total harmonic distortion (THD) as a function of input voltage amplitude. The results demonstrate that the MI-OTA achieves a low THD of 0.36% at an input voltage of 250 mV, confirming the rail-to-rail operation capability of the proposed design. Additionally, the total power consumption of the MI-OTA is only 70 nW, highlighting its suitability for ultra-low-power applications.

Figure 7(a) shows the AC response of the MI-OTA’s output current for \(\:{I}_{set}\) = 7 nA, obtained through a Monte Carlo (MC) mismatch analysis with 200 runs. Figure 7(b) shows the histogram of the AC response from Fig. 7(a) at 10 Hz, where the mean value is − 166.6 dB and the standard deviation is 235 mdB. Figure 7(c) illustrates the AC response under different process corners, including Typical-Typical (TT), Fast-Fast (FF), Fast-Slow (FS), Slow-Fast (SF), and Slow-Slow (SS) MOSFET corner conditions. As evident from the plots, the curves are closely aligned and fall within an acceptable tolerance range, indicating robust performance under both mismatch and process variation.

The universal filter structure based on MI-OTAs, as depicted in Fig. 3(a), was analyzed using a bias current of \(\:{I}_{set1-5}\) = 7 nA and capacitors \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) each set to 20 pF. The frequency response, shown in Fig. 8, reveals a cutoff frequency of 31.2 Hz, while the overall power consumption was calculated as 350 nW. The dashed line in Fig. 8 represents the pre-layout simulation, while the continuous line represents the post-layout simulation. As shown, the curves from the pre-layout and post-layout simulations overlap due to the negligible impact of parasitic effects on circuit performance, which is attributed to operation in a low-frequency range. In addition, the ideal responses are provided for comparison in the results.

To explore the tuning flexibility, Fig. 9 illustrates the filter response when \(\:{I}_{set3-5}\) is held constant at 7 nA, and \(\:{I}_{set\text{1,2}}\) is varied among 3.5 nA, 7 nA, and 14 nA. These settings produced cutoff frequencies of 16.7 Hz, 31.2 Hz, and 59.5 Hz, respectively.

For the shadow filter design shown in Fig. 4(b), the transconductance amplifier (\(\:{g}_{mA}\)) generates output currents in the nanoampere range. To achieve unity gain under such conditions, high-value resistor in the megaohm range is required. In this design, \(\:{R}_{1}\) was chosen as 100 MΩ, representing a balance between resistance size and power consumption. Increased amplifier bias current lowers the necessary resistance, but leads to higher power usage, highlighting a critical design trade-off. The filter’s frequency response under varying amplifier currents (\(\:{I}_{gmA}\) = 14 nA, 28 nA, and 56 nA) and constant \(\:{I}_{set1-5}\) = 7 nA is shown in Fig. 10. The total power consumption of the shadow filter is 490 nW when \(\:{I}_{gmA}\) = 14 nA and \(\:{I}_{set1-5}\) = 7 nA. It can be observed that the passband gain of the filters is unity. However, a peak appears in the gain of the all-pass filter at the center frequency due to a high-quality factor that given by factor \(\:1+{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\). Conversely, the response becomes flatter when a lower quality factor is selected.

Figure 11 illustrates the transient response of the LPF under specific biasing conditions. In Fig. 11(a), the LPF’s output is shown when \(\:{I}_{gmA}\) = 14 nA and \(\:{I}_{set1-5}\) = 7 nA. A sinusoidal input signal with an amplitude of 20 mV and a frequency of 5 Hz was applied. Under these conditions, the total harmonic distortion (THD) was 0.3%. Figure 11(b) presents the variation of THD with respect to different input amplitudes, demonstrating the filter’s linearity characteristics across a range of signal levels.

Figure 12 shows the output voltage noise of the LPF. The integrated output noise over the 0.1–53 Hz bandwidth is calculated to be 392 µV, resulting in a dynamic range of 40 dB for 1% total harmonic distortion.

Experimental result

To verify the functionality of the proposed universal shadow filter, the topology was experimentally tested. The prototype circuit was implemented using commercially available integrated circuits (ICs), specifically the LM13700N48. A parallel configuration of OTAs, as shown in Fig. 1(b), utilizing the LM13700N, was employed to realize the MI-OTA.

The circuit was powered by symmetric supply voltages of \(\:{V}_{DD}\) = \(\:{-V}_{SS}\) = 5 V. A sinusoidal input signal was applied, and the corresponding output waveforms were measured using a KEYSIGHT DSOX1204G oscilloscope. The circuit was implemented on a prototyping board to validate the functionality and performance of the proposed design of the shadow filter.

For determining the transconductance value, the bias input pin of the LM13700N was connected to ground through a suitably chosen resistance. In accordance with the proposed filter configurations shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the transconductances \(\:{g}_{m3}\), \(\:{g}_{m4}\), \(\:{g}_{m5}\), and \(\:{g}_{mA}\) were set to 0.496 mS by using a resistance value of 150 kΩ. The transconductances \(\:{g}_{m1}\) and \(\:{g}_{m2}\) were set to 1.46 mS using 50 kΩ resistors. The capacitance values \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) were selected as 220 nF. Based on these parameters, the theoretical natural frequency (\(\:{f}_{o}\)) is calculated to be approximately 1.056 kHz. To allow for convenient adjustment during experimental testing, a resistor \(\:{R}_{1}\) was used to vary the voltage gain \(\:{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\).

Figure 13 shows the measured magnitude and phase responses of the proposed circuit, configured as the universal filter shown in Fig. 3, with a natural frequency of \(\:{f}_{o}\)=1.05 kHz and a quality factor \(\:Q\approx\:1\). The results confirm the filter functionalities summarized in Table 1, demonstrating that applying the input signal to \(\:{V}_{1}\) (\(\:{V}_{1}\)=\(\:{V}_{in}\)), yields an inverting response and non-inverting responses for the LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF.

Figure 14 shows the measured magnitude and phase responses of the proposed circuit configurated as the universal shadow filter in Fig. 4(a). In this experiment, the resistor \(\:{R}_{1}\) was set to 10 kΩ, resulting in a voltage gain of \(\:{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) = 4.97. These results validate the shadow filter behavior in Eqs. (19)-(22), confirming that the voltage gain control both the natural frequency and quality factor of LPF, HPF, and BPF responses, while controlling only the quality factor of BSF and APF. In these results, the natural frequency of the LPF, HPF, and BPF is 2.58 kHz, while the natural frequency of BSF and APF remains at 1.05 kHz.

The universal shadow filter was tested by varying the voltage gain \(\:{g}_{mA}{R}_{1}\) through adjustments of the resistor \(\:{R}_{1}.\) Fig. 15 shows the measured magnitude responses of the LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF for \(\:{R}_{1}\) resistor values of 5.1 kΩ, 10 kΩ, and 20 kΩ. For these values, the natural frequencies of the LPF, HPF, and BPF were 1.98 kHz, 2.58 kHz, and 9.49 kHz, respectively, corresponding to \(\:{R}_{1}\) values of 5.1 kΩ, 10 kΩ, and 20 kΩ, respectively. Meanwhile, the natural frequencies of the BSF and APF remained constant at 1.05 kHz, while their quality factors changed to 3.5, 5.9, and 10.8 for \(\:{R}_{1}\)values of 5.1 kΩ, 10 kΩ, and 20 kΩ, respectively.

From Fig. 15, it can be concluded that for the proposed shadow filter, both the natural frequency and quality factor of the LPF, HPF, and BPF responses can be varied using an external amplifier, whereas only the quality factor of the BSF and APF responses can be adjusted in this way. This behavior is consistent with the theoretical predictions given in Eqs. (19)–(22). It should also be noted that both simulation and experimental results are in good agreement, confirming the validity of the proposed theory.

The proposed shadow filter is compared with previous works22,23,24,29,30, as summarized in Table 4. All referenced designs offer electronic tuning capability but lack support for inverting input signals. The filter presented in22 operates in current-mode and features a BPF-controlled shadow configuration. However, the output currents of the LPF, HPF, and BPF do not exhibit high output impedance, necessitating the use of additional buffer circuits. The filter in23 operates in current-mode, while the filters in29,30 operate in voltage-mode. These designs employ LPF- and BPF-controlled shadow filter structures. The filter in24 operates in multi-mode, allowing both voltage and current signals as inputs, and is based on an LPF-controlled shadow filter configuration. Compared to all previous works, the proposed shadow filter provides the most comprehensive set of transfer functions, including both non-inverting and inverting configurations of LPF, HPF, BPF, BSP, and APF filters. In contrast to the filters presented in22,23,24,30, the proposed design allows independent electronic tuning of the natural frequency and the quality factor (in the case of BSP and APF) without affecting the passband gain. The shadow filter’s low-power operation, simplicity, and ability to provide precise low-frequency filtering make it particularly well-suited for processing biosignals such as ECG and EEG, as well as for conditioning sensor outputs. Its design flexibility and robustness against process variations further enhance its practicality in real-world, low-frequency, and low-voltage scenarios common in these fields.

Conclusions

This paper presents a novel voltage-mode, low-pass controlled shadow universal filter based on multiple-input operational transconductance amplifiers. Leveraging the multiple-input capability of the OTAs, the proposed filter topology simultaneously supports both inverting and non-inverting transfer functions for various responses, including LPF, HPF, BPF, BSF, and APF filtering. A key feature of the design is that the passband gain of all filter responses can be compensated during the tuning of the natural frequency and quality factor, simply by appropriately configuring the input signals. The use of multiple-input bulk-driven MOS transistors operating in the subthreshold region enables the OTAs to function at low supply voltages, with low power consumption, and a wide input voltage swing. Due to its low-power operation and suitability for low-frequency applications, the proposed filter is especially well-suited for bio-signal processing tasks and sensor interfaces. Experimental results obtained using the LM13700 IC validate the proposed theory.

Data availability

Key data of all results is provided within the manuscript. Supplementary data (datasets of computer-aided analysis of circuits and detailed measurement results) can be shared with readers based on their reasonable request (addressed to corresponding author).

References

Lakys, Y. & Fabre, A. Shadow filters–new family of second-order filters. Electron. Lett. 46, 276–277. https://doi.org/10.1049/el.2010.3249 (2010).

Biolkova, V. & Biolek, D. Shadow filters for orthogonal modification of characteristic frequency and bandwidth. Electron. Lett. 46, 830–831. https://doi.org/10.1049/el.2010.0717 (2010).

Abuelma’atti, M. T. & Almutairi, N. R. New current-feedack operational-amplifier based shadow filters. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 86, 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10470-016-0691-7 (2016).

Kumngern, M. & Junnapiya, S. OTA-based voltage-mode universal biquadratic filter with single-input multiple-output, IEEE International Conference on Cyber Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Bangkok, Thailand, 2012, pp. 152–155, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/CYBER.2012.6392544

Langhammer, L., Sotner, R., Dvorak, J., Jerabek, J. & Zapletal, M. Fully-Differential Universal Frequency Filter with Dual-Parameter Control of the Pole Frequency and Quality Factor, IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Florence, Italy, 27–30 May 2018, pp. 1–5, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS.2018.8351005

Pandey, N., Pandey, R., Anurag, R. & Vijay, R. A class of Differentiator-Based multifunction biquad filters using OTRAs. Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. 18, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.15598/aeee.v18i1.3363 (2020).

Faseehuddin, M., Herencsar, N., Shireen, S., Tangsrirat, W. & Md Ali, S. H. Voltage differencing buffered Amplifier-Based novel truly Mixed-Mode biquadratic universal filter with versatile Input/Output features. Appl. Sci. 12 (1229). https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031229 (2022).

Bunrueangsak, S. et al. Synthesis of electronically tunable multifunction biquad filter using voltage differencing differential input buffered amplifiers. ETRI J. 47, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.4218/etrij.2023-0391 (2025).

Khateb, F., Jaikla, W., Kulej, T., Kumngern, M. & Kubánek, D. Shadow filters based on DDCC. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 11, 631–637. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-cds.2016.0522 (2017).

Chhabra, K., Singhal, S. & Pandey, N. Realisation of CBTA Based Current Mode Frequency Agile Filter, In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 7–8 March 2019, pp. 1076–1081. https://doi.org/10.1109/spin.2019.8711586

Abuelma’Atti, M. T. & Almutairi, N. New voltage-mode bandpass shadow filter, In Proceedings of the 2016 13th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Leipzig, Germany, 21–24 March 2016, pp. 412–415. https://doi.org/10.1109/ssd.2016.7473695

AbuelmaAtti, M. T. & Almutairi, N. New CFOA-based shadow banpass filter, In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communications (ICEIC), Danang, Vietnam, 27–30 January 2016, pp. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1109/elinfocom.2016.7562969

Nand, D. & Pandey, N. New configuration for OFCC-Based CM SIMO filter and its application as shadow filter. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 43, 3011–3022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-017-3058-1 (2018).

Anurag, R., Pandey, R., Pandey, N., Singh, M. & Jain, M. OTRA based shadow filters, In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON), New Delhi, India, 17–20 December 2015, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/indicon.2015.7443524

Lakys, Y. & Fabre, A. Shadow filters generalisation to nth-class. Electron. Lett. 46 https://doi.org/10.1049/el.2010.0452 (2010).

Rami, R. et al. Low power agile active filter with digitally controlled center-frequency, In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Multimedia Computing and Systems (ICMCS), Marrakech, Morocco, 14–16 April 2014, pp. 1528–1534. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMCS.2014.6911353

Singh, D. & Paul, S. K. Mixed-mode universal filter using FD-CCCTA and its extension as shadow filter. Informacije MIDEM. 52, 239–262. https://doi.org/10.33180/InfMIDEM2022.404 (2022).

Singh, D. & Paul, S. K. Improved current mode biquadratic shadow universal filter. Informacije MIDEM. 52, 51–66. https://doi.org/10.33180/InfMIDEM2022.106 (2022).

Pandey, N., Pandey, R., Choudhary, R., Sayal, A. & Tripathi, M. Realization of CDTA based frequency agile filter, In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Computing and Control (ISPCC), Solan, India, 26–28 September 2013, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ispcc.2013.6663403

Alaybeyoğlu, E., Guney, A., Altun, M. & Kuntman, H. Design of positive feedback driven current-mode amplifiers Z-Copy CDBA and CDTA, and filter applications. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 81, 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10470-014-0345-6 (2014).

Atasoyu, M. et al. European Conference on Circuit Theory and Design of current-mode class 1 frequency-agile filter employing CDTAs, In Proceedings of the (ECCTD), Trondheim, Norway, 24–26 August 2015, pp. 1–4, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/ecctd.2015.7300066

Alaybeyoğlu, E. & Kuntman, H. A new frequency agile filter structure employing CDTA for positioning systems and secure communications, Analog Integrated Circuits and Signal Processing, vol. 89, pp. 693–703, 2016, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10470-016-0770-9

Singh, D. & Paul, S. K. Realization of current mode universal shadow filter. AEU-International J. Electron. Commun. 117, 117, 153088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2020.153088 (2020).

Singh, D. & Paul, S. K. Realization of multi-mode universal shadow filter and its application as a frequency-hopping filter. Memories-Materials Devices Circuits Syst. 4, 100049, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memori.2023.100049 (2023).

Khateb, F., Kumngern, M., Kulej, T. & Ranjan, R. K. 0.5 V multiple-input multiple-output differential difference transconductance amplifier and its applications to shadow filter and oscillator. IEEE Access. 11, 31212–31227. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3260146 (2023).

Kumngern, M., Khateb, F. & Kulej, T. Shadow filters using multiple-input differential difference transconductance amplifiers. Sensors 23, pp. (1526). https://doi.org/10.3390/s23031526 (2023).

Kumngern, M., Khateb, F. & Kulej, T. Novel Multiple-Input Single-Output shadow filter with improved passband gain using Multiple-Input Multiple-Output DDTAs. Electronics 14, 1417, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071417 (2025).

Varshney, G., Pandey, N. & Pandey, R. Generalization of shadow filters in fractional domain. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 49, 3248–3265. https://doi.org/10.1002/cta.3054 (2021).

Kumngern, M., Khateb, F., Kulej, T. & Wattikornsirikul, N. Design of shadow filter using Low-Voltage Multiple-Input operational transconductance amplifiers. Appl. Sci. 15 (781). https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020781 (2025).

Huaihongthong, P. et al. Single-input multiple-output voltage-mode shadow filter based on VDDDAs. AEU–International J. Electron. Commun. 103, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2019.02.013 (2019).

Moonmuang, P., Pukkalanun, T. & Tangsrirat, W. Voltage Differencing Gain Amplifier-Based Shadow Filter: A Comparison Study, In Proceedings of 2020 6th International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Technology (ICEAST), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1–4 July 2020, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/iceast50382.2020.9165352

Alaybeyoğlu, E. & Kuntman, H. CMOS implementations of VDTA based frequency agile filters for encrypted communications. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 89, 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10470-016-0760-y (2016).

Buakaew, S., Narksarp, W. & Wongtaychatham, C. Fully Active and Minimal Shadow Bandpass Filter, International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences, and Technology (ICEAST), Phuket, Thailand, 4–7 July 2018, pp. 1–4, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEAST.2018.8434448

Buakaew, S., Narksarp, W. & Wongtaychatham, C. Shadow Bandpass Filter with Q-improvement, 5th International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Technology (ICEAST), Luang Prabang, Laos, 2–5 July 2019, pp. 1–4, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEAST.2019.8802535

Buakaew, S., Narksarp, W. & Wongtaychatham, C. High Quality-Factor Shadow Bandpass Filters with Orthogonality to the Characteristic Frequency, In Proceedings of the 2020 17th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Phuket, Thailand, 24–27 June 2020, pp. 372–375. https://doi.org/10.1109/ECTI-CON49241.2020.9158304

Buakaew, S. & Wongtaychatham, C. Boosting the quality factor of the shadow bandpass filter. J. Circuits Syst. Computers. 31, 2250248, https://doi.org/10.1142/s0218126622502486 (2022).

Mishra, P. et al. 8.7 A 112Gb/s ADC-DSP-Based PAM-4 Transceiver for Long-Reach Applications with > 40dB Channel Loss in 7nm FinFET, 2021 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, pp. 138–140, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSCC42613.2021.9365929

Wyville, M. W., Smiley, R. C. & Wight, J. S. Frequency agile RF filter for interference attenuation, 2012 IEEE Radio and Wireless Symposium, Santa Clara, CA, USA, pp. 399–402, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/RWS.2012.6175382

Metin, B., Basaran, Y. & Cicekoglu, O. MOSFET-C current mode filter for secure communication applications. AEU-International J. Electron. Commun. 143, 154017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2021.154017 (2022).

Lakys, Y. & Fabre, A. A fully active frequency agile filter for multistandard transceivers, 2011 International Conference on Applied Electronics, Pilsen, Czech Republic, pp. 1–7. (2011).

Atasoyu, M., Metin, B., Kuntman, H. & Herencsar, N. New Current-Mode class 1 Frequency-Agile filter for multi protocol GPS application. Elektronika ir. Elektrotechnika. 21, 35–39. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.eee.21.5.13323 (2015).

Krummenacher, F. & Joehl, N. A 4-MHz CMOS continuous-time filter with on-chip automatic tuning. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 23, 750–758. https://doi.org/10.1109/4.315 (1988).

Khateb, F., Kulej, T., Kumngern, M. & Psychalinos, C. Multiple-input bulk-driven MOS transistor for low-voltage low-frequency applications. Circuits Syst. Signal. Process. 38, 2829–2845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-018-0999-x (2019).

Khateb, F., Kulej, T., Akbari, M. & Tang, K. T. A 0.5-V multiple-input bulk-driven OTA in 0.18-µm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. VLSI Syst. 30, 1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVLSI.2022.3203148 (2022).

Shah, M. O., Privitera, M., Ballo, A., Alioto, M. & Pennisi, S. 0.4-V nW-Power High-Gain Bulk-Driven Two-Stage OTA with Self-Cascode composite transistors and intrinsic Current-Buffer miller compensation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I: Regul. Papers (Early Access). 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2025.3570542 (2025).

Furth, P. M. & Andreou, A. G. Linearised differential transconductors in subthreshold CMOS, Electronics Letters, vol. 31, pp. 545–547, 1995, (1995). https://doi.org/10.1049/el:19950376

Nevárez-Lozano, H. & Sánchez-Sinencio, E. Minimum parasitic effects biquadratic OTA-C filter architectures. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 1, 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00239678 (1991).

Texas Instruments & LM13700. : Dual Operational Transconductance Amplifier with Linearizing Diodes and Buffers, URL (2015). http://www.ti.com/product/LM13700.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Defence, Brno, within the Organization Development Project VAROPS.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. paper preparation, methodology, experiments; F.K. paper preparation, methodology, simulations; T.K. paper preparation, review; editingD.A. paper preparation, software; reviewAll authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumngern, M., Khateb, F., Kulej, T. et al. A 0.5-V MI-OTA-based shadow universal filter with integrated passband gain compensation and low-pass control for low-frequency applications. Sci Rep 15, 37403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21325-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21325-7