Abstract

The composite materials are widely used across industries however, these materials are prone to damages like cracking and delamination due to its complexity. The Electromechanical Impedance (EMI) technique offers a reliable non-destructive solution for detecting such damage using piezoelectric sensors and enabling effective structural health monitoring and enhancing safety and durability. This study explores the application of the EMI technique for monitoring damages in composite fibre concrete specimens. The specimens were prepared using Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), fly ash, and polypropylene, glass fiber mixture, water, fine and coarse aggregates. The Piezoelectric sensors were employed to record conductance and susceptance signatures, enabling early detection and quantification of damages. The severity of damages were assessed using statistical indices such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Mean Absolute Percentage Deviation (MAPD), and Correlation Coefficient (CC) revealing higher sensitivity. A notable leftward shift in EMI signatures with increasing damage was confirmed progressive structural degradation. Additionally, structural parameters equivalent stiffness and equivalent damping were evaluated, demonstrating a decrease in stiffness and an increase in damping with greater damage depth. Temperature effects on EMI responses were also investigated, necessitating compensation for reliable analysis. An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model was trained using Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm and implemented to predict conductance values and damage depth. The developed ANN showed high accuracy, with strong agreement between experimental and predicted results. Overall, the findings confirm the EMI technique’s potential for SHM of composite fiber concrete and integration with machine learning for improved predictive its durability assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Composite materials offer advantages such as lightweight, high strength, and corrosion resistance. However, their complex and heterogeneous nature make structural integrity assessment challenging. The damages like delamination and matrix cracking are difficult to detect with conventional methods, highlighting the need for advanced health monitoring techniques. It is not possible to apply the traditional techniques like ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) test, rebound hammer on composite fibre concrete structures. Apart from this, global technique can not be applied on these type of structure. Hence, the EMI technique is best option for the composite fibre concrete structures. Effective multi-damage detection strategies are crucial to ensure the reliability and longevity of these structures.

The fiber-reinforced concrete is increasingly being used as a construction material because it has better mechanical properties than unreinforced concrete, and it can improve the mechanical performance of conventionally reinforced concrete. An experimental study incorporating plastic waste into concrete cubes, with plastic content varying from 0% to 3% was presented1. Polypropylene fiber, a synthetic material characterized by its low density, fine diameter, and low modulus of elasticity, was used. This fiber boasts high strength, ductility, durability, abundant availability, low cost, and the ability to undergo physical and chemical modifications as needed. Consequently, it has significant potential for widespread use in concrete products2,3. Polypropylene fiber parameters significantly improved the fracture properties of the composite concrete containing 6% silica fume and 15% fly ash upon addition to the concrete composite4,5. These parameters included midspan deflection, fracture, critical crack opening displacement, fracture energy, and maximum crack opening displacement for three-point bending beam specimens6,7,8,9.

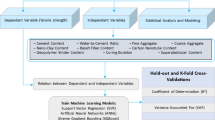

This study investigated the influence of unlike amounts of glass and polypropylene fiber content on the concrete properties by measuring multi-damage detection and durability of composite structures using the Electromechanical Impedance (EMI) technique as shown in Fig. 1.

Numerous NDT techniques have been developed to inspect civil structures. These techniques can be broadly divided into two categories: contact and non-contact methods. Contact methods, such as traditional ultrasonic testing, eddy current testing, and electro-magnetic testing10,11,12,13,14,15, require a sensor to be physically attached to the structure to obtain reliable data. Smart sensors collect data about damage and durability, which is analyzed and sent to user devices. Structural damage health monitoring (SDHM) detects early stages of concrete deterioration and predicts its lifespan as shown in Table 116,17,18. On the other hand, non-contact methods involve technologies such as infrared, radiography, thermography, and holography19,20,21,22, offering an advantage in situations where physical contact with the tested structure is not feasible. Various studies have employed the EMI based non-destructive technique to evaluate fibre content in steel fibre concrete (SFC) structures, investigate the early-age performance of the Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP)–steel interface, and optimize coated PZT sensors for structural health monitoring of hybrid fibre-reinforced concrete beams23,24,25.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Initially, the theoretical study of the EMI technique and its relevance for detection of the depth of multiple damages in composite fibre concrete specimens are presented. This is followed by a detailed description of the experimental setup designed to simulate multiple damage depths in concrete specimens. Subsequently, the analysis of conductance and susceptance signatures were carried out. Conventional statistical indicators, including root mean square deviation (RMSD), correlation coefficient (CC), and mean absolute percentage deviation (MAPD), were employed to quantify varying damage depths using a machine learning approach, specifically an artificial neural network (ANN) model. Finally, a methodology for localizing the depth of damage and evaluating its severity were proposed for composite fiber-reinforced concrete specimens of different grades, and the results are validated through both experimental and ANN-based approaches.

Research objectives

This investigation aims to apply the EMI technique for detecting, identifying, and quantifying multiple depths of damage in concrete structures. By analyzing conductance and susceptance signatures obtained from surface-bonded PZT patches, the research accurately assesses the damage severity. Statistical indicators such as RMSD, CC, and MAPD were employed to distinguish between healthy and damaged states, with results validated through ANN model. The proposed methodology enhances early-stage damage detection, contributing to more reliable structural health monitoring (SHM). Additionally, the study aims to apply EMI to real-life structures for predicting remaining service life based on depth of damages, develop experimental setups to determine key structural parameters (e.g., equivalent damping and stiffness), and implement SHM strategies tailored to the unique demands of high-strength concrete structures.

Fundamental of electro-mechanical impedance technique (EMI)

In the EMI technique, the PZT patch is bonded to concrete surface, The bonding area is cleaned with sandpaper and isopropyl alcohol to remove any dust and ensure proper bonding of the patch with structure. A two-part epoxy adhesive (Araldite) was used for its high stiffness and strong bonding. The PZT patches are pressed onto the prepared surface with uniform pressure to avoid air gaps and left to cure at room temperature for 24 h. For calibration, baseline admittance signatures are recorded using an impedance analyzer (LCR meter) with a 30–400 kHz frequency range. The EMI technique is extremely sensitive to incipient damage and is not acceptable to be affected by interference of mechanical and electrical noise. This approach is served as reference signals for detecting damage-induced deviations during experiments and robust against variations in distant boundary conditions and mass loads by Bhalla and Soh 2003, 2004.

When a concrete structure undergoes damage such as cracks or corrosion, its mechanical impedance (dynamic response) alters, leading to changes in the electromechanical admittance (inverse impedance) signal describes the electrical response of the PZT transducer influenced by the mechanical properties of the structure. This is effectively captured using a surface-bonded PZT patch excited at frequencies above 30 kHz with an input voltage of around 1 V as shown in Fig. 2. Accurate modeling of PZT–structure interaction requires consideration of both extensional and longitudinal vibrations, utilizing the full set of piezoelectric equations to capture both direct and converse effects36,37.

where D3 represents the electric displacement in the Z-direction of a Cartesian coordinate system. The piezoelectric strain constants in the X and Z directions are denoted by d31 and d33, respectively; T1, and T3 refer to the stress and while S1, and S3 indicate the strain in X and Z directions, respectively; the Poisson’s ratios denote ν13 and ν33; By referencing established definitions of effective mechanical impedance and introduce the motion equations governing the interection between the patch and structure using Eq. 1,Eq. 2 and Eq. 3), the admittance formula Y(ω)is derived to characteries the impedance model of the surface PZT transducer can be references in detail as38:

where l represents the length, b represents the width, and h represents the thickness of the patch, respectively; V and I are denote the instantaneous voltage and current across the PZT patch.

Zs,eff = effective impedance of the host the structure.

Za,eff = effective impedance of the PZT transducer.

YE = YE (1 + jη) = Complex Young’s modulus of elasticity at constant electric field.

\(\:\stackrel{-}{{\epsilon\:}_{33}^{T}}=\:\stackrel{-}{{\epsilon\:}_{33}^{T}}\:(1-\:\text{j}{\updelta\:})\:\:\)= Complex electrical permittivity at constant stress of the PZT.

\(\:\delta\:\) =Dielectric loss factor.

\(\:\upsilon\:\) =Poisons ratio.

\(\:\eta\:\) =Mechanical loss factor.

n = the coupling degree represent between the longitudinal and extensional vibration modes of the PZT patch.

\(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\)=Complex tangent ratio.

ω = angular frequency.

It is evident from Eq. (4) that any related change in the structural properties such as stiffness, and damping causes a change in the impedance, that is affected by cracks or damages. Hence damages in structure which were examined by analyzing changes the admittance signature \(\:\stackrel{-}{Y}\) (consisting of the real part is conductance and imaginary part is susceptance) indicating damage.

The passive component remains unaffected by structural damage as it relies solely on patch parameters, while the active component shows the interactive coupling between the patch and the structure that results actively diagnosing damage. This is achieved by substituting the effective mechanical impedance of the host structure and the PZT transducer, i.e., Zs, eff = xs + jys, and Za, eff = xa + jya, into Eq. (4), the real parts and imaginary parts of impedance structure, i.e., xs and ys can be obtained as follow :

where GA and BA are the real and imaginary parts of the YA, and M and N are the real and imaginary parts of the parameter \(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\:,\:\)with no specific meaning other than simplification. The parameters \(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\:\)is given by \(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\:=M+{N}_{j\:\:\:\:}\) and is defined as: \(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\:=M+{N}_{j\:\:\:\:}=\frac{4j\omega\:bl}{h}\:\:\left[\frac{\stackrel{-}{{Y}^{E}}\:\:({d}_{31}\:+\:n{d}_{33})\:{d}_{31\:}{Z}_{a,eff}}{\left(\:1-\:n\:{v}_{13}\right)({Z}_{a,eff}+{Z}_{s,eff})}\left(\frac{\text{tan}{\mathbb{k}}_{l}}{{\mathbb{k}}_{l}l}\right)\:\right]\:\) but only for the simplification using Eq. 5 and Eq. 6. Following the process, the parameters are computed from the raw admittance signature and used for damage analysis respectively in Table 2.

It is standard procedure to calculate the RMSD % root mean square deviation to statistically measure the changes and it is given by Eq. (7)

Where\(\:\:{G}_{i}^{1}\) is the damaged (post-damage) state at the i-th frequency point and\(\:{G}_{i}^{0}\) is the pristine (pre-damage) state at the i-th frequency point of a conductance value. The ‘N’ represents a number of observations. The root-mean-square deviation value can also be shown as a sub-frequency interval approach, in which the different signature is compared to the baseline signature separately for unlike frequency ranges13.

Experimental setup

Specification of material used with proportions for concrete mixing and casting specimen

The experiment was conducted on the concrete specimens that were prepared using OPC cement having 28-day compressive strength of 43 MPa, meeting IS 10262:2019 requirements, and other properties detail given in Table 3. The fly ash, with less than 11% lime content, was sourced from a thermal power plant. River sand from local riverbeds, IS sieve of fine aggregate meeting IS: 383–2016 grading zone-II, with a fineness modulus of 2.95, specific gravity of 2.64, and 1% water absorption, was employed. The machine-crushed angular aggregate of 20 mm size, conforming to IS: 383–2016, with a specific gravity of 2.81, fineness-modulus of 7.3, and 0.5% water absorption, was used. SIKAPLAST-HE2002, a super-plasticizer conforming to IS 9103, was employed to maintain workability with a constant w/b ratio. It had a 41% solids content, pH of 5.8, and specific gravity of 1.08. Crimped polypropylene fibers, as depicted in Fig. 3 and detail in Table 4, were incorporated in the study.

The study utilized concrete mixture proportions detailed in Table 5. Eighteen concrete mixtures were formulated based on a water to binder ratio (w/b) of 0.27 and a fine-to-coarse aggregate ratio (F/C) of 0.72. Mixing was performed using a tilting drum-type mixer of 30-liter capacity, and specimens were cast using steel moulds, specifically standard cube 150 × 150 × 150 mm moulds. The experimental setup for monitoring is depicted in Figs. 5 and 6. Fresh concrete mixtures were compacted in moulds using a table vibrator, and the specimens after 24 h were demoulded, and subsequently water-cured until testing at 7 and 28 days, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

The plot of compressive strength of mixes M60 and M65 for the a set of cube 1, cube 2 and cube 3 at 7-days and 28-days is shown in Fig. 5. For each grade, a set of three cubes was tested: one set of cubes was used for EMI monitoring to detect fine damages, while the other 2 sets of three cubes were tested for compressive strength at 7 and 28 days as shown in Fig. 5.

The experiment was conducted using a 150 × 150 × 150 mm composite fire concrete cube specimens. The healthy state signatures were recorded of each specimens. The conductance vs. frequency and susceptance vs. frequency signatures were developed. The control damages were induced on one side near the PZT patch, which was bonded on the top surface of the cube at distances of 50 mm and 100 mm from the corner. In first stage, a damage of 2 mm deep crack at 50 mm from the corner was created and the signature of the conductance vs. frequency and susceptance vs. frequency signatures were recorded. Subsequently, additional 2 mm deep cracks were introduced at 100 mm. The nomenclatures of damages were given as damage location 1 having depth 2 mm represents as damage 1_2mm. Similarly damage location 2 having depth 8 mm represents as damage 2_8mm etc. The damage depth was increased to 6 mm at location 1(50 mm from corner) named 1_6mm. The damage 2_8 mm was generated increasing the damage depth of 8 mm at location 1. Similarly, damages of damages 2_2mm. 2_6 mm and damage 2_8mm were developed by generating the damages of 2 mm, 6 mm and 8 mm at location 2 (100 from corner).

With increasing damage severity (2 mm, 6 mm, and 8 mm), as shown in Fig. 6, a noticeable leftward shift in the conductance signature was observed. These signatures were recorded using a LCR meter over a frequency range of 30–400 kHz. At the healthy state, a 1-volt excitation was applied to the PZT patch to obtain the baseline signature as shown in Fig. 7. The extent of the shift varies with the damage level, for damage exceeding 8 mm, the curve shifts further to the left, as depicted in Figs. 8 and 9, and Fig. 10.

Experimental result of surface PZTs for damage identification

Typically, baseline measurements were obtained for a new structure and saved for future comparison with subsequent data to detect any damage. Any changes in the newly acquired signature data relative to the baseline signature data were used to determine any damage in the structure. One of the challenges with using baseline subtraction techniques to evaluate a system’s structural response is that it is often difficult to distinguish between structural changes and the effects of altering environmental and operational factors. Environmental and operational factors such as fluctuations in temperature, changes in surface moisture, and variations in loading conditions can all cause the structure’s response to deviate significantly from the baseline measurement.

The plot shows several lines in Fig. 8, each of which corresponds to a different state of the resonance peak of conductance shift. The lines labeled “healthy state” and “damage 1_2mm”, “damage 2_2mm”, “damage 1_6mm”, “damage 2_6mm”, “damage 1_8mm” and “damage 2_8mm” likely correspond to different amounts of depth of damage in the cube specimens. A consistent shift is observed in the conductance signature from the baseline up to an 8 mm depth of damage as shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

The parameters were measured by the LCR meter for each frequency, including G and B. Typically, the admittance signature recorded after damage is depicted in Figs. 8 and 9, comparative to the pristine signature. The consistent curves of B vs. f shift suggests that the PZT patch remains intact all throughout from the baseline up to an 8 mm depth of damage, as shown in Figs. 10 and 11, aligning with established diagnostic criteria21. A consistent shift is observed in the conductance signature from the baseline up to an 8 mm depth of damage.

Additionally, RMSD, MAPD, CC indexes were computed for various dimensions of damages for mixes M60 and M 65. The RMSD, MAPD, CC plots with the induced dimentions were analyzed. It was observed that If dimention of the damages increases, the values of the RMSD index increases, indicating the greater sensitivity of the sensor to a depth of damage. A plot was prepared between the depth of damages and corresponding change in the value of RMSD, MAPD, CC and shown in Figs. 12 and 13.

Evaluation based on equivalent stiffness and damping characteristics

The concept of “impedance-based identification” offers a more precise understanding of damage, a well-established principle within EMI technique, proven to be superior to merely demonstrating the measuring conductance signature changes. This approach involves generating Zs, eff = (x + yj) through the computational method outlined in39,40. Subsequently, the frequency variation of components ‘x’ and ‘y’ are compared with that of different conventional systems using Eq. 8. Mechanical impedance components ‘x’ and ‘y’ are explain from the G and B plots, as illustrated in Fig. 14, and Fig. 15, displaying their fluctuations with frequency (f) (Table 6). Initially, identifying frequency ranges indicative of a suitable mechanical system is followed by examining ‘x’ and ‘y’ as damage increases within these frequency ranges. Comparison along the Hixon table (Hixson, 2001) reveals that depth of damage 1 and depth of damage 2 adhere to a combination of spring and damper in parallel, as described in Table 7.

while, the depth of damages conforms to a parallel combination of spring and damper, represented by the following equations. Structural parameters, such as equivalent damping and equivalent stiffness, were computed based on these equations for all depths of damages. In the experimental plot, the value of ‘x’ varies with frequency, thus an average value was chosen in Figs. 14 and 15. The equivalent stiffness ‘k’ decreases with increases depth of damage 1 and 2, illustrated in Figs. 16 and 18. On the other hand, the equivalent damping ‘c’ increases as the depth of damage 1 and 2 damage increases, as depicted in Figs. 17 and 19, and follow the combination of Table 7. This trend is attributed to the development of microscopic pores within the material as cracks propagate, leading to an increase in equivalent damping.

The table provides polynomial functions along with their corresponding R-squared values for two different concrete mixtures, M60 and M65. The polynomial functions represent the relationship between the depth of damage and two parameters: equivalent stiffness (k) and equivalent damping (c) as shown in Table 7.

The polynomial function for equivalent stiffness (k) is given in Table 7k = 1E + 06d2 – 2E + 07d + 2E + 09, where d represents the depth of damage in mm. The R-squared value associated with this function is R² = 0.9712, indicating a strong correlation between the depth of damage and equivalent stiffness. Similarly, the polynomial function for equivalent damping (c) is provided in Table 7c = 16.164d2 – 71.264d + 5327.7, with an R-squared value of R2 = 0.9642, suggesting a high degree of correlation between the depth of damage and equivalent damping.

The quadratic term in the equivalent stiffness (k) polynomial reflects the nonlinear variation of stiffness with frequency. A large positive coefficient, such as 1 × 106 in M60, indicates a rapid change in stiffness at higher frequencies, likely due to dynamic effects or the initiation of micro-damage. The linear term governs the rate of change, while the constant term corresponds to the initial static stiffness. For equivalent damping (c), the M60 polynomial c = 16.164d2 – 71.264d + 5327.7 shows a dip followed by an increase in damping, suggesting energy dissipation due to internal friction or micro-cracks. Similarly, M65 exhibits high-magnitude coefficients (1 × 106d2), indicating strong nonlinear damping behavior.

Based on these equations, structural parameters such as equivalent damping, and equivalent stiffness were calculated for all types of cube specimens. In the experimental table plot, the values of parameters k and c change with the increased depth of damage. This leads to varying percentage changes in the parameters, which are tabulated in Tables 8 and 9. Specifically, the equivalent stiffness of a value ‘k’ decreases with the depth of damage increases, are tabulated in Tables 8 and 9 for cube specimens M60 and M65. The equivalent damping of value ‘c’ increases with the depth of damage, as Illustrated in the Table for cube specimens M60 and M65.

Temperature effect evaluation using EMI technique

To study temperature effects the Electro-Mechanical Impedance (EMI) response of composite fibre concrete for M60 and M65, an experimental setup, composite fibre concrete specimens with PZT sensors were placed inside a controlled-temperature chamber of electric thermostatic drying oven. The sensor wires were carefully extended outside the chamber to allow signal monitoring without disturbing the internal environment. After positioning the specimens, the chamber door was closed, and the temperature was gradually increased. After reaching a target temperature, the system was maintained at that level for 2.5 h to ensure uniform heating throughout each specimen. This procedure were repeated for three different temperature settings: 35 °C, 45 °C, and 55 °C. Subsequent conductance measurements indicated that the sensor responses changed with temperature as shown in Fig. 20. Specifically, the resonant peaks in the conductance signatures shifted towards lower frequencies as the temperature increased. This trend was observed in the composite fibre concrete specimens.

The graph illustrates Fig. 21 the effect of temperature on EMI-based statistical metrics (RMSD, MAPD, CC, and R²) for M60 and M65 composite concrete. As temperature increases from 35 °C to 55 °C, all metrics show a rising trend, indicating that temperature significantly influences EMI signatures. Therefore, in practical structural health monitoring applications using PZT-based EMI techniques, it is essential to incorporate temperature compensation strategies to ensure accurate damage detection. The observed RMSD, MAPD and CC values were corrected considering these temperature effects. For values of temperature other than 35 °C, 45 °C and 55 °C, the values of RMSD, MAPD and CC were determined using linear interpolation.

Artificial neural network experimental results for damage identification

An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is a model inspired by the structure and function of the human brain. They are comprised of interconnected layers of artificial neurons, also known as units or processing elements41. The input layer receives raw data, which is then processed by one or more hidden layers. These hidden layers extract complex features and patterns from the data using activation functions. Finally, the output layer produces the network’s prediction or classification. ANNs have the ability to learn complex relationships within the data. However, they can be computationally expensive and require large datasets for effective training42,43.

The effectively predict the depth of damage in concrete using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Initially, a range of variables is tested to enhance network performance. After testing various methods, the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) training method is identified as the most suitable for predicting the depth of damage to concrete. In the present study, an ANN model is developed using an experimental dataset to predict the depth of damage to composite concrete. The dataset is categorized based on frequency and percentage change of conductance signature in term as RMSD, MAPD and CC for different damagelevels: damage_1_2mm, damage_2_2mm, damage_1_6mm, damage_2_6mm, damage_1_8mm, and damage_2_8mm.

The plot as depicted in Figs. 22 and 23 predicted the depth of damage with respect to given dataset of frequency vs. conductance signature. The different lines represent the actual damage and predicted conductance signature for healthy state and various depth of damage (damage 1–2 mm depth data, damage 2–2 mm depth data, damage_1_2mm, damage_2_2mm, damage_1_6mm, damage_2_6mm, damage_1_8mm, damage_2_8mm) as depicted in Figs. 21 and 22.

An artificial neural network (ANN) model was developed to predict damage in composite concrete using data from the EMI technique. The change in conductance signature in term of RMSD, MPAD and CC are used as input parameters, with the damage level as the output. Before training, The dataset was pre-processed by normalizing input features between 0 and 1 and removing outliers. It was split into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. The ANN architecture included an input layer with two neurons, two hidden layers with 16 and 8 neurons (both using ReLU activation), and an output layer with a single neuron using a linear activation function. The model was trained with the Adam optimizer over 500 epochs, applied early stopping based to prevent overfitting and incorporating dropout layers with a 20% rate for improved generalization. Performance was evaluated using R², RMSE, and MAE to ensure prediction accuracy as shown in Table 10. This detailed ANN framework ensures reliable and efficient prediction of structural damage using EMI data.

The x-axis represents the target value, while the y-axis represents the output value. The green line shows a linear fit between the target and output, with an R-squared value of 0.99218. This high R-squared value indicates a very strong correlation between the target and output values as shown in Fig. 24 (a). The R-squared value of the linear fit is 0.99218. An R-squared value of 0.99218 indicates a very strong positive correlation between the target values and the output values. The y-axis label says “Output ~ 0.99, Target + 6.9e-06”. This equation suggests that the output is linearly related to the target, with a slope of 0.99 and a y-intercept of 6.9e-06 as shown in Fig. 24 (b) .The R-squared value of the linear fit is 0.99218. An R-squared value close to 1 indicates a very strong positive correlation between the target values and the output values of the model. In other words, the model’s predictions are very close to the actual target values as shown in Fig. 24 (c). An R-squared value close to 1 indicates a very strong positive correlation between the target and the output values of the model as shown in Fig. 24 (d).

The blue line shows the decrease in error on the training data, while the green line represents the validation error. Evaluation of validation error is crucial for assessing the network’s ability to generalize. The red line indicates the error on the test data, providing an independent measure of the model’s generalization to the data and its performance during and after training (Fig. 25). Prediction errors (residuals) based on the training set help assess the model fit, while errors from the validation set measure the model’s ability to predict new data.

Discussions

The experimental results presented in Tables 8 and 9 indicate that, for both M60 and M65 composite fiber concrete, equivalent stiffness (k) decreases while equivalent damping (c) increases as crack depth progresses. For M60 concrete, the % change in stiffness reduced from 2.34 × 10⁹ N/m in its healthy state to 2.30 × 10⁹ N/m at an 8 mm crack depth, representing a reduction of 1.35%. Meanwhile, the % change in equivalent damping increased from 5.253 × 10⁻⁵ Ns/m to 5.649 × 10⁻⁵ Ns/m, showing a 7.55% increase. In the case of M65 concrete, the reduction in stiffness was more pronounced, dropping from 2.31 × 10⁹ N/m to 1.00 × 10⁹ N/m, which equates to a 5.67% decrease. Damping for M65 increased from 6.102 Ns/m to 6.593 Ns/m, reflecting an 8.05% rise. These findings suggest that higher-grade concrete (M65) experiences greater equivalent stiffness degradation with damage, while equivalent damping proves to be more sensitive in detecting early-stage cracks. Temperature studies, illustrated in Figs. 20 and 21, showed a distinct leftward shift in conductance peaks and a consistent increase in statistical indices (RMSD, MAPD, CC, R²) as the temperature rise from 35 °C to 55 °C. This indicates that thermal effects significantly influence EMI technique responses, even in the absence of mechanical damage. Consequently, it is essential to incorporate temperature compensation strategies for reliable PZT-based structural health monitoring (SHM) applications. Additionally, the percentage of RMSD values is influenced by the severity of the damage. A polynomial function has been created using the percentage of RMSD values to represent a curve line correlation could be expressed as:

where y denotes the % RMSD of the conductance signatures and x is the depth of the damage in the as Eq. 9 and Eq. 10. The introduction section explains various causes of damage in cubes. Cracks are one of the processes of damage in cubes that can be effectively monitored using the EMI technique. Similar to cracks in any concrete structure, damage can be measured accordingly.

The Figs. 26 and 27 depict the percentage variation in predictions generated by the ANN model across different depth of damage states in composite fibre concrete cube specimens. As the number of damage depth states increases, the percentage variance in ANN predictions correspondingly decreases. The decreasing prediction variance with deeper damage levels reflects the ANN model’s heightened sensitivity to structural changes. This suggests that the model can reliably differentiate and assess varying degrees of damage in composite fibre concrete specimens.

Limitations

The PZT patch is brittle, so it cannot be removed from the host structure without breaking. Its sensing zone is limited, with a range typically between 0.4 and 2 m depending on the material’s shape, size, and properties. There are various limitations of the PZT patch, including aging, mechanical, electrical, and thermal factors.

Conclusions

The baseline signature is an important reference for future damage analysis and structural rehabilitation efforts. Both conductance signatures and susceptance signatures are closely related to the strength degradation of the concrete specimen. In this study, the EMI technique was utilized to evaluate the sustainability of concrete structures. Surface-bonded PZT patches were employed to extract conductance and susceptance signatures from the fibre concrete cube specimens under investigation. The conductance signature consistently shifted with increased damage, with a noticeable leftward shift signifying more severe damage. Following are the specific conclusions from the investigation.

-

1.

The composite concrete structure can be monitored successfully using EMI technique.

-

2.

The analysis revealed a strong connection between the damage severity and RMSD, MAPD, and CC indices that confirming effective damage detection and prediction its severity.

-

3.

The EMI response was significantly influenced by temperature, indicating the necessity of temperature compensation for accurate damage quantification. The ANN model consistently tracked temperature effects with reliable R² values across M60 and M65 specimens.

-

4.

Equivalent stiffness decreased while damping increased with increasing damage depth, aligning with theoretical expectations. The Experimental analysis showed gradual percentage variations in stiffness and damping parameters, reaching up to 7.55% with increased damage depth.

-

5.

The ANN model achieved high predictive accuracy with an R² of 0.9893, supporting its application in automated damage detection systems for composite fiber concrete structures.

Future work will focus on implementing real-time monitoring using embedded PZT sensors in large-scale concrete structures, integrating temperature compensation algorithms, and enhancing the ANN model with larger datasets for improved generalization. Additionally, exploring hybrid machine learning approaches and validating the system under field conditions will strengthen its practical applicability in structural health monitoring.

Data availability

Data availability statementAll data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Salahaldein Alsadey. Effect of polypropylene fiber reinforced on properties of concrete. J. Adv. Res. Mech. Civil Eng. 3 (4), 2208–2379 (2016).

Shakir, A. & Maha, E. Effect of polypropylene fibers on properties of mortar containing crushed brick as aggregate. Eng. Tech. 26 (12), 1508–1513 (2008).

Im, H., Hong, S., Lee, Y., Lee, H. & Kim, S. A colorimetric multifunctional sensing method for structural-durability-health monitoring systems. Adv. Mater. (2019).

Im, H. et al. A highly sensitive ultrathin-film iron corrosion sensor encapsulated by an anion exchange membrane embedded in mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 506–514. (2017).

Taheri, S. A review on five key sensors for monitoring of concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 204, 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.172 (2019).

Zhang, P. & Li, Q. Fracture properties of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete containing fly Ash and silica fume. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 5 (2), 665–670 (2013).

Wandowski, T., Malinowski, P. & Ostachowicz, W. Improving the EMI-based damage detection in composites by calibration of AD5933 chip. Measurement 171, 108806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108806 (2021).

Chandramouli, K., Srinivasa, P., Rao, R. & Srinivasa Rao Narayanan, Pannirselvam strength properties of glass fiber concrete. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 5 (4), 1–6 (2010).

Enfedaque, A., Alberti, M., Gálvez, J. & Domingo, J. Numerical simulation of the fracture behaviour of glass fibre reinforced cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 136, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.130 (2017).

Aymerich, F. & Meili, S. Ultrasonic evaluation of matrix damage in impacted composite laminates. Compos. Part. B–Eng. 31, 1–6 (2000).

Huang, J., He, Z., Khan, M. B. E., Zheng, X. & Luo, Z. Flexural behaviour and evaluation of ultra-high-performance fibre reinforced concrete beams cured at room temperature. Sci. Rep. 11, 19069. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98502-x (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. The improvement of mechanical properties of conventional concretes using carbon nanoparticles using molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 11, 20265. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99616-y (2021).

Gao, J., Wu, J., Li, J. & Zhao, X. Monitoring of corrosion in reinforced concrete structure using Bragg grating sensing. NDT&E Int. 44 (2), 202–205 (2011).

Bernachy-Barbe, F., Sayari, T., Dewynter-Marty, V. & Hostis, L. Using X-ray microtomography to study the initiation of chloride-induced reinforcement corrosion in cracked concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 119574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119574 (2020).

Kırlangıç, A. S. Nonlinear vibration-based Estimation of corrosion-induced deterioration in reinforced concrete. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 10 (4), 639–651 (2020).

Rekha, S. A. & Hui, Q. Active damage detection of LNG tank under different static pressure using piezoelectric sensors. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 25 (5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01048-2 (2024).

Singh, S. & Shanker, R. Wireless sensor networks for Bridge structural health monitoring: a novel approach. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 1425–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00578-5 (2023).

Singh, S. & Shanker, R. Development of a robust structural health monitoring system: a wireless sensor network approach. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 1129–1137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-022-00537-6 (2023).

Avdelidis, N. P. & Moropoulou, A. Applications of infrared thermography for the investigation of historic structures. J. Cult. Herit. 5, 119–127 (2004).

Wang, J. & Ueda, T. Automatic damage detection and segmentation using deep learning algorithms in reinforced concrete structure inspections. Struct. Concrete. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202400722 (2024).

Negi, P., Chhabra, R., Kaur, N. & Bhalla, S. Health monitoring of reinforced concrete structures under impact using multiple piezo-based configurations. Constr. Building Mater. 222, 371–389 (2019).

Dos Santo, J. A. et al. M.J.M. Damage localization in laminated composite plates using mode shapes measured by pulsed TV holography. Compos. Struct. 76, 272–281 (2006).

Yang, Z. et al. A novel electromechanical impedance-based method for non-destructive evaluation of concrete fiber content. Constr. Build. Mater. 351, 128972 (2022).

Shivangi, Singh, P. & Mohammed, B. S. Optimizing coated PZT sensors for structural health monitoring in hybrid Fibre-Reinforced concrete beams. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-025-01755-z (2025).

Deng, J., Wu, X., Li, X., Qin, Y. & Zhong, K. Automatic assessment of CFRP-steel interfacial performance under adhesive curing using PZT-based EMI-integrated deep learning technique. Thin-Walled Struct. 209, 112894 (2025).

Yan, W. & Yuan, L. Damage Detection in Structural Systems Using a Hybrid Method Integrating EMI with ANN. Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Chengdu, China 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/APPEEC.2010.5448696 (2010).

Ai, D., Mo, F., Yang, F. & Zhu, H. Electromechanical impedance-based concrete structural damage detection using principal component analysis incorporated with neural network. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 33 (17), 2241–2256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X221077440 (2022).

Nelon, C. M., Myers, O. J. & Hall, A. The intersection of damage evaluation of fiber-reinforced composite materials with machine learning: A review. J. Compos. Mater. 56 (9), 1417–1452. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219983211037048 (2022).

Wandowski, T. & Malinowski, P. Electromechanical impedance data fusion for damage detection. In: (eds Rizzo, P. & Milazzo, A.) European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring. EWSHM 2020. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering 128. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64908-1_54 (2021).

Oliver, G. A., Ancelotti, A. C. & Gomes, G. F. Neural network-based damage identification in composite laminated plates using frequency shifts. Neural Comput. Applic. 33, 3183–3194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05180-3 (2021).

Qian, C. et al. Application of artificial neural networks for quantitative damage detection in unidirectional composite structures based on lamb waves. Adv. Mech. Eng. 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814020914732 (2014).

Crivelli, D., Guagliano, M. & Monici, A. Development of an artificial neural network processing technique for the analysis of damage evolution in pultruded composites with acoustic emission. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 56, 948–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.09.005 (2013).

Shao, Y-F., Guo, F., Jiang, P., Li, W. & Zhang, W-Q. Damage detection and classification of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composite materials based on acoustic emission and convolutional recurrent neural network. Struct. Health Monit. 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217241270883 (2024).

Kansizoglou, G. M., Naoum, I., Papadopoulos, M. C., Chalioris, C. E. & N. A., & A deep learning approach for autonomous compression damage identification in Fiber-Reinforced concrete using piezoelectric lead. Zirconate Titanate Transducers. 24 (2), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24020386 (2024).

Tawie, R., Park, H. B., Baek, J. & Na, W. S. Damage detection performance of the electromechanical impedance (EMI) technique with various attachment methods on glass fibre composite plates. Sensors 19 (5), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/S19051000 (2019).

Annamdas, V. G. M. & Soh, C. K. Embedded piezoelectric ceramic transducers in sandwiched beams. Smart Mater. Struct. 15 (2), 538–549 (2006).

Negi, P., Chakraborty, T., Kaur, N. & Bhalla, S. Investigation on effectiveness of embedded PZT patches at varying orientations for monitoring concrete hydration using EMI technique. Constr. Build. Mater. (2018).

Ai, D., Zhu, H. & Luo, H. Sensitivity of embedded active PZT sensor for concrete structural impact damage detection. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 348–357 (2016).

Bhalla, S. & Soh, C. K. Structural impedance based damage diagnosis by piezo-transducers. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 32 (12), 1897–1916. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.307 (2003).

Bhalla, S. & Soh, C. K. Electromechanical impedance modeling for adhesively bonded Piezo-Transducers. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 15 (12), 955–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X04046309 (2004).

Jiang, X., Zhang, X., Tang, T. & Zhang, Y. Electromechanical impedance based self-diagnosis of piezoelectric smart structure using principal component analysis and LibSVM. Sci. Rep. 11, 11345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90567-y (2021).

Haq, M., Bhalla, S. & Naqvi, T. Piezo-impedance based fatigue damage monitoring of restrengthened concrete frames. Compos. Struct. 280 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114868 (2022).

Sharma, A. K., Sharma, R. K. & Kasana, H. S. Prediction of first lactation 305-day milk yield in Karan Fries dairy cattle using ANN modeling. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 7 (3), 1112–1120 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to gratefully thank the Department of Civil Engineering of the Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology Allahabad, Prayagraj, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Maheshwari Sonker contributed to the writing of the manuscript by preparing the original draft, organizing the experimental methodology, analyzing the data, and editing the final version. She also conducted the experimental work and implemented machine learning integration for data interpretation.B. Rama Shanker contributed significantly to the writing process by reviewing the manuscript, providing critical revisions, and offering expert guidance throughout the study. He was also responsible for the conceptualization of the research framework.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sonker, M., Shanker, R. Smart monitoring of composite concrete damage using EMI technique with temperature effects compensation and ANN integration. Sci Rep 15, 38318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22251-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22251-4