Abstract

The fabrication of ternary nanocomposites attracts great interest in scientific research worldwide. PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are prepared by the casting method with various proportions of AgONPs. Analysis of XRD and FTIR spectra exhibited that the structural parameters of PVC/PMMA blend have been affected with increasing nanofiller content. UV–Vis spectra analysis showed that the direct/indirect energy gap are decreased from (5.21/4.92) to (4.86/3.90) eV and the dispersion and oscillation (Ed/Eo) energies are increased from (1.186/4.437) to (73.323/13.638) eV with increasing the content of AgONPs. Linear/nonlinear optical parameters of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are enhanced upon increasing AgONPs content. This study also showed that the antibacterial activity of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites against Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, B. subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) is enhanced. Generally, PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites show promising potential in the field of flexible optoelectronic devices due to the structure-dependent adjustable optical energy gap and in the medical field for their pronounced antibacterial activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is one of the most common polymeric materials and is widely used in plastic production due to its reasonable cost, suitable mechanical properties, ease of manufacturing, long life, versatility, low price and sufficient strength. Moreover, PVC is a flame-retardant, hydrophobic and recoverable polymer. The applications of PVC include microelectronics, building construction, packaging, medical equipment and high-dose measuring devices [1]. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), commonly known as acrylic, is a rigid polymer with interesting toughness, corrosion resistance, and optical clarity. PMMA is an excellent host material for doping because of its optical homogeneity and good transparency, which can play a significant role in the construction of advanced optical materials. Therefore, it is widely used in microphotonics, batteries, solar cells, optical devices, lenses, dosimetry, detection of α-particles, and as a base for nanofilters for blocking γ and UV rays [2, 3]. PMMA is mostly used as light guide panel (LGP) in the liquid crystal displays (LCDs) screens due to its transparency and optical clarity [4].

Nowadays, blending technology has gained a lot of academic and commercial importance. Polymer blends mostly exhibit superior properties over any of their component polymers. The miscibility of the component polymers determines the blend structure which in turn will affect the blend properties. It is found that miscibility depends on many factors such as preparation method, polymer tacticity, etc. and hence a lot of contradictory results have been reported about the predictability of miscibility [5,6,7,8]. Hence, blending or mixing the two components, PVC and PMMA, can result in a blend with enhanced optical and mechanical properties. The miscibility of PVC/PMMA polymer blend is due to the hydrogen bonding formation. Such bonding is occurred between α-hydrogen of PVC and C = O groups of PMMA [9].

Nowadays, the interest in silver oxide nanoparticles (AgONPs) as a common metal oxide is gradually increasing with great strength due to its prevalent presence in a variety of potential applications such as magneto-optical storage systems, photovoltaic devices, nanoelectronics fabrication, optical devices, sensors, optical switching, biomedicine and silver oxide/zinc batteries [10,11,12]. Silver can form a variety of oxides by its reaction with oxygen, and since silver is a multivalent metal, such reactions produce AgO, Ag2O, Ag2O3, and Ag3O4. It is evident from the literature that among all the above silver oxides, AgO and Ag2O have technologically important applications. Polymers or polymer blends are suitable hosts for inorganic nanoparticles (INPs). The incorporation of INPs can significantly affect the optical and electrical properties of the polymeric materials [13, 14]. The properties of polymer-inorganic nanocomposites depend on the type of INPs, concentration, size, shape, and interaction of the INPs with the polymer matrix. Nanocomposites composed of inorganic nanoparticles and polymers are receiving increasing attention with regard to value-added areas derived from their outstanding thermal, optical, magnetic, electrical and antibacterial properties [15,16,17,18,19].

Our current work is aimed to prepare PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites by casting method and to investigate the morphology of these nanocomposites using SEM, structural behavior via XRD analysis, chemical interactions via FTIR spectroscopy and optical properties through UV/Vis spectroscopy analysis. The selected nanofiller material (AgONPs) exhibits distinctive properties such as low optical band gap, high refractive index and dielectric constant. Thus, we expect an improvement in the recently reported physical properties of the pure polymer blend of PVC/PMMA which can expand its applications in anti-reflection for solar cell application, photovoltaic coatings and semiconductors. Also, the antibacterial activity of these PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites against different types of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is evaluated.

Experimental work

Materials

PVC with molecular weight of ~ 100,000 g/mol is obtained from BDH Chemicals Ltd., Poole, (UK) and PMMA with molecular weight of ~ 93.000 g/mol is obtained from Polysci., Inc., (USA).

Material preparation

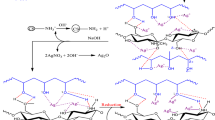

A 0.05 M silver ion solution (Ag+) and a 0.1 M NaOH solution are prepared to obtain silver oxide nanoparticles (AgONPs) using chemical reduction technique. In order to prevent the nanoparticles from aggregating and maintain their smallest size, sodium tricitrate is used as a dispersant. A glass beaker is filled with 100 mL of silver solution and 0.5 g of sodium tricitrate is added. The solution is then heated to boiling with continuous stirring. After that, 20 mL of 0.1 M NaOH solution is gradually added dropwise, resulting in a noticeable color change from transparent to brown. The brown precipitate is filtered and washed many times with deionized water for removing any residual by-products.

PVC/PMMA polymer blend samples are prepared using casting method by dissolving each polymer separately in the desired weight ratio (0.5/0.5g) in dimethylformamide (DMF). The two solutions are mixed with silver oxide nanoparticles in different proportions in an acetic acid under continuous stirring for a period of time until a homogeneous solution is obtained. The mixture is then poured onto a glass substrate in an oven at 333 K for several days to completely evaporate the solvent from the films. The thickness of the prepared films ranged from 40 to 60 μm as measured by digital micrometer (Mitutoyo No. 293-521-30, Japan). The schematic diagram of the interaction between PVC/PMMA blend and AgO nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 1.

Characterization methods

The surface morphology of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites is investigated using JSM-IT500HR (JEOL, Japan). XRD measurements are carried out at a current of 50 mA and voltage of 40 kV using Bruker D8 advance powder XRD with a CuKα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Ǻ) with a scan rate of 3°/min in the whole range of measurements from 2θ = 5° to 80°. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is performed in the range from 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 1 cm−1 in ambient air at room temperature by Thermo Scientific iD5 ATR spectrometer. UV/Vis measurements are performed in the range from 200 to 1100 nm by UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1601 PC, Shimadzu, Japan).

Antibacterial activity

The anti-bacterial activity of the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites is conducted against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli). The paper discs soaked in the desired concentration of the complex solution are placed aseptically in the petri dishes containing nutrient agar media (agar 20g + beef extract 3g + peptone 5g) seeded with S. aureus, B. subtilis and E. coli. The petri dishes are incubated at 36 °C and after 24 h of incubation, the inhibition zones are recorded.

Results and discussion

SEM

Scanning electron microscope reflects the microscopic structure of polymer blends, the dispersion state of each individual component in the films and the regularity of their phase distribution. SEM is used to investigate the surface morphology of PVC/PMMA blend and their nanocomposites doped with various concentrations of AgO, as shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2a illustrates the SEM micrograph of PVC/PMMA blend. The smooth surface of the polymer blend film exhibited homogeneous dispersion of the blend matrix.

Figure 2(b and c) displays SEM micrographs of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites loaded with 1 and 10 wt% of AgO nanoparticles. These micrographs confirmed the incorporating and homogeneous distribution of AgO nanoparticles with cylindrical shape within the host matrix of PVC/PMMA blend with an average size of 98.43 nm, as shown in Fig. 2d. The chemical composition of the prepared AgONPs is investigated using EDX analysis. The EDX spectrum of AgONPs in the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites loaded with 1 and 10 wt% of AgO nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 3(a and b). According to the Fig. 3, a sharp peak is obtained confirming the existence of Ag and O elements in the EDX spectrum. In addition, other elements such as C and Cl are observed.

Roughness

Figure 4(a–c) depicts the surface roughness of pure PVC/PMMA blend and PVC/PMMA loaded with various concentrations of AgONPs. The roughness is investigated using Image J software and the roughness parameters are extracted from roughness curves, and Table 1 demonstrates the results. It is worth noting that Ra refers to the average height, Rq is the root mean square height of the profile, Rp is the maximum peak height, and Rz is the average maximum height. It is observed from Table 1 that all roughness parameters are significantly affected by increasing the content of AgONPs in the matrix of PVC/PMMA blend.

X-ray diffraction

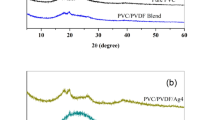

XRD is an important tool to evaluate the crystal structure. It is used to calculate the crystal size and lattice parameters. XRD pattern of AgO, PVC/PMMA blend and their nanocomposites doped with different concentrations of AgO is demonstrated in Fig. 5(a and b). XRD pattern of AgO showed several peaks such as, 14.88°, 17.20°, 21.67°, 23.87°, 27.56°, 31.32°, 32.01°, 38.10°, 41.80°, 44.14°, 48.42°, 57.54°, 64.53° and 77.47°. Since sodium tricitrate is used as a dispersant to prepare AgONPs, the Bragg’s angles at 14.88°, 17.20° and 21.67° are assigned as trisilver citrate corresponding to (020), (112) and (122) planes, whereas, the Bragg’s angles at 38.10°, 44.14°, 64.53° and 77.47°, are indexed to (111), (200), (220) and (311), planes of pure Ag (JCPDS card No.04- 0783) [20]. Also, the Bragg’s angles at 27.56°, 32.01°, 48.42° and 57.54° correspond to the planes of (100), (− 111), (200) and (220) respectively, confirming the presence of AgO nanoparticles and in agreement with JCPDS (01–076–1489) [20]. On the other hand, the amorphous nature of the PVC/PMMA blend sample is confirmed by the presence of the broad peak in the range 10–30°, as shown in Fig. 5b [21]. XRD pattern of the nanocomposite samples showed several diffraction peaks at 16.90, 23.87, 27.56, 32.01, 40.23, 48.42 and 57.54° with various intensities. The sample crystallite size (D), internal lattice strain (ε) and the intercrystallite distance (R) are evaluated using Debye-Scherer formula using full width at the half maximum (FWHM) of the high-intensity peak (− 111), as follows and demonstrated in Table 2.

where λ is the x-ray wavelength and β is the FWHM and is measured in radians. Other lattice parameters such as, dislocation density (δ), stacking fault (SF), and the crystallites number per unit area (Nc) are calculated as follows [22]:

where d is the sample thickness. The lattice parameters are estimated and presented in Table 2. It is found that the crystal size is ranged from 32.85 to 78.41 nm.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy is a powerful method for investigating the vibrational modes of the polymers and the interaction between the functional groups of the polymer blend matrix and the nanofiller. FTIR spectra of PVC/PMMA blend and PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 6(a and b). The characteristic absorption peaks of both PVC and PMMA are observed.

The characteristic bands of PVC are generally classified into three regions. The first region ranged from 2970 to 1250 cm−1 represents the C–H modes, the second region ranged from 1200 to 900 cm−1 is called C–C stretching and the third region ranged from 700 to 600 cm−1 is called the C–Cl stretching, respectively. The peaks at 2994 and 2949 cm−1 are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibration of C–H, in methyl (–CH3) and methylene (= CH2) groups, respectively [20, 23, 24]. The bands at 1726 cm−1, 1434 cm−1, 1386 cm−1 and 1330 cm−1 are attributed to C = O stretching vibrations, C–H aliphatic bending vibrations, bending vibration of CH3 and to CH2 deformation, respectively [25, 26]. The absorption bands between 1500 and 1380 cm−1 are assigned to C–H deformation modes of methyl subunits. The bands at 1241 cm−1, 1190 cm−1, 1146 cm−1 and 1060 cm−1 are assigned to bending bond of C–H near Cl, skeletal vibrations coupled to C–H deformation, O–CH3 stretching vibration and C–C backbone of PVC, respectively [27,28,29]. The peaks at 964 and 912 cm−1 are assigned to trans CH wagging and C–H rocking mode, respectively [30]. The bands at 842 cm−1, 751 cm−1, 690 cm−1 and at 613 cm−1 are due to CH2 rocking methylene rocking mode, bending vibrational of C–H functional group, C–Cl stretching vibration and cis CH wagging, respectively [31,32,33]. The peak at 527 cm−1 refers to the existence of AgONPs [34]. The characteristic peaks of PVC and PMMA are listed in Table 3.

The coordination interaction between the two oxygen atoms in –COO−moieties and Ag(II) ions in various coordination modes has been elucidated. The characteristic bands related to carboxylate groups appear in the ranges 1535–1618 cm−1 and 1349–1467 cm−1 for asymmetric and symmetric stretching, respectively [35]. Over the increase of AgONPs content, the symmetric stretching (COO−) is decreased, while, the asymmetric stretching peak (COO−) appears at 1537 cm−1 with an increase in intensity based on AgONPs content [36]. Subsequently, the coordination interaction between COO–Ag can be proceeded via different coordination modes (monodentate or bidentate). Additionally, the effect of AgONPs on the vibration modes can be seen in terms of intensity change, broadening of the bands and shifting of the bands to higher or lower wavenumber. It is clear that many of the characteristic peaks of PVC/PMMA blend have been affected upon the increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. The peaks at 1386 cm−1, 1060 cm−1 and 690 cm−1 are blue shifted to 1396 cm−1, 1065 cm−1 and 698 cm−1 with shift order of 9 cm−1, 5 cm−1 and 8 cm−1, respectively. On the other hand, the peaks at 1146 cm−1, 842 cm−1, 751 cm−1 and 613 cm cm−1 are red shifted to 1142 cm−1, 834 cm−1, 739 cm−1 and 607 cm−1 with shift order of 4 cm−1, 8 cm−1, 12 cm−1 and 6 cm−1, respectively. Also, the intensity of most these peaks is increased with increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. The shift in the peak position to the lower or higher wavenumber may be attributed to the coordination between the Ag2+ and Cl atoms of vinyl groups of PVC and may be due to the cross-link’s formation between the Ag2+ and ester oxygen atoms in PMMA [37].

UV/Vis spectroscopy

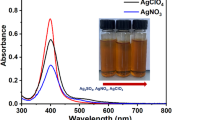

The absorption spectra of PVC/PMMA blend and PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are illustrated in Fig. 7a. It is clear that the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites displayed a considerably strong absorption in comparison to pure PVC/PMMA blend over the whole range of UV/Vis spectra, due to the high absorption coefficient of AgONPs. The spectrum of PVC/PMMA blend exhibited a strong absorption peak at 227 nm is attributed to the electronic transition in C = O groups of the ester-attached to the repeat units in PVC/PMMA main-chain and can be assigned to π-π* transition [27].

On the other hand, the absorption in the entire wavelength range is enhanced upon increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. This enhancement in absorption is attributed to the high absorptivity of AgONPs which in turn will increase the refractive index of the nanocomposite samples due to the rise in the polarization. Also, the absorption peak of the PVC/PMMA blend is shifted to appear at 236 nm with a red shift in the order of 9 nm in the spectra of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites. This shift can be related to the complexation between AgONPs and the host matrix of the blend. Further, a new broad peak is observed at 445 nm in PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO nanocomposite sample and shifted to 479 nm upon increasing the AgONPs content. This peak is a typical of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and its shift to higher wavelength is indicating to the existence of larger nanoparticles [38]. The absorption coefficient (α = 2.303A/d, where A is the absorbance and d is the sample thickness) is plotted versus the photon energy, as illustrated in Fig. 7b. By extrapolating the linear part of the plot to intersect the x-axis at α = 0, the absorption edge values (Eed) are evaluated and demonstrated in Table 4. It is clear that the incorporating AgO decreased the absorption edge of PVC/PMMA matrix from 5.12 to 4.52 eV. The decreasing in Eed (red shift) indicated that new localized states are created in the band gap of the blend matrix after embedding AgONPs. This behavior confirms that doping with AgO nanoparticles reduced the optical bandgap. The absorption coefficient (α) displays an exponential dependent on photon energy (hυ) near the absorption edge and is expressed according to Urbach’s equation as follows [39]:

where αo is a constant and EU is the Urbach tail energy, which is defined as the localized states width in the optical bandgap. Figure 7c shows the variation of ln α versus hυ for our investigated samples. The EU values are simply estimated from the slopes of the fitted lines of Fig. 7c and given in Table 4. It is found that EU is increased from 0.31 to 1.30 eV with increasing the content of AgONPs. The increase in EU indicates that the disorder in the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposite samples is increased. Density of defects (DOD) and relaxation of the distorted bonds are estimated in terms of steepness parameter (β) and strength of electron–phonon interaction (Ee-p), using the following equations [40]:

where kB and T are the Boltezman’s constant and room temperature, respectively. The calculated values of β and Ee-p are presented in Table 4. It is clear that as the steepness parameter is decreases, Ee-p increases upon increasing the AgONPs content. This behavior confirms that the defect density states have increased near the absorption edge [41].

The extinction coefficient (k = αλ/4π) of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites is plotted versus the wavelength as demonstrated in Fig. 8a. It is found that k decreases sharply in UV region whereas it starts to increase again in the visible region upon increasing the wavelength. It is also clear that, upon increasing AgO content in the nanocomposites, k increased, indicating increased energy loss due to absorption and scattering by AgO nanoparticles. These significant interactions between AgONPs and the polymer blend induce structural changes, thus affecting the band structure and absorption ratio. The rise in k linearly upon increasing the wavelength for the highly doped samples in the visible region makes PVC/PMMA/AgO nanostructures useful in many optical applications such as, sensing application in Vis–NIR region.

Figure 8(b and c) represents the variation of the transmittance and reflectance of PVC/PMMA blend and their nanocomposites. It is clear that the transmittance is increased sharply in the UV region due to the fact that the high energy of the incident photons can excite electrons from valence band to the conduction band.

On the other side, at λ = 600 nm in the visible region, the transmittance is reduced from 97.99% for PVC/PMMA blend to 35.22% upon increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles, where they act as centers of absorption and scattering for the incident photons. This wide range of transmittance of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites makes them suitable for a wide range of applications such as, optical coating purposes. On the other hand, at the same wavelength the reflectance is increased from 1.29 to 20.27%.

The skin depth is an optical parameter that describes the loss of electromagnetic radiation when transmitted through materials and is considered as a measure of how deeply incoming photons can penetrate a material [42]. The fluctuation in the skin depth of both pure polymer blend and their nanocomposites as a function of photon energy is seen in Fig. 8d. The exponential decay of the incident photon in the material is expressed by the φ parameter, which is represented as follows:

From Fig. 8d, skin depth decreases as the AgONPs content and photon energy increases. Low energy photons are less likely to be absorbed while for photons of shorter wavelengths (higher energies), several interaction modes are possible, where electrons can undergo HOMO to LUMO transitions upon absorption of high energy photons. Hence, φ decreases for higher energy photons.

The band gap between highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) can be evaluated near the absorption edge by examining the absorption data. The optical band gap (Eg) energy of the samples is calculated using the following eq. [43]:

where B is a constant and s is an exponent describes the transition nature and equals to 1/2 and 2 for allowed direct and allowed indirect transitions, respectively. Figure 9(a and b) depicts the dependence of (αhυ)2 and (αhυ)0.5 of the prepared samples on hυ. It is clear that both (αhυ)2 and (αhυ)0.5 exhibited a linear behavior at the higher values of photon energy (hυ), meaning that both direct and indirect transitions are achievable. The extrapolation of these linear portions to the hυ-axis at (αhυ)2 and (αhυ)0.5 = 0, gives direct (Egd) and indirect (Egi) energy values and listed in Table 4. It is found that the incorporating of AgO nanoparticles affects the band structure of the blend and decreases the (Egd/Egi) from 5.21/4.92 eV for pure PVC/PMMA to 4.86/3.90 eV for PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO nanocomposite sample.

The decreasing in the optical bandgap values upon increasing the content of AgONPs confirmed that the electronic structure of PVC/PMMA blend is modified and new localized states are created in the band gap which in turn facilitates the electronic transition between valance band and conduction band. Our findings are in good agreement with the previously published data in the literature [44]. Hence, the embedding of AgONPs enhances the semiconducting properties of polymeric nanocomosites for use in many device applications [45]. The carbon cluster (Ncc) of nanocomposite samples is calculated using the following formula [46]:

It is clear that Ncc is enhanced (see Table 4) and increased from 48 for PVC/PMMA blend to 77 for PVC/PMMA/10 wt%AgO nanocomposite. The enhancement of Ncc is attributed to the creation of more defects and localized states in the host matrix of polymer blend upon increasing AgONPs content, which led to a decreasing in the optical bandgap, hence, Ncc values will be improved. Similar results are reported for previously for polymeric nanocomposites [47].

Single oscillator model

Apart from the design of some optical devices, the refractive index (n) of materials has a necessary role in optical communication system. The refractive index depends on the material’s density, bond’s strength and molecular weight and is directly related to the reflectance and extinction coefficient as follow [48]:

The refractive index of pure polyblend and its nanocomposites is represented in Fig. 10a. It is clear that the refractive index is enhanced upon increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles due to the structure modification and formation of nanoparticles agglomerations and clusters within PVC/PMMA matrix. The refractive index of pure polyblend at λ = 700 nm in the visible region is increased from 1.252 to 2.629 for PVC/PMMA/10 wt%AgO nanocomposite sample. The rise in the refractive index with an increase in the content of AgO nanoparticles make the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are useful in many optical approaches. The refractive index dispersion observed in Fig. 10a is interpreted by applying the single oscillator model (SOM). Refractive index dispersion below the absorption edge with the incident photon energy is represented as follow [48]:

where E0 is the oscillator energy and gives quantitative information about the overall band structural of the materials, and Ed is the dispersion energy and estimates the optical transition strength between bands associated with structural order degree of the materials. Figure 10b demonstrates the variation of (n2-1)−1 against (hυ)2, and the parameters E0 and Ed are calculated using intercept (E0/Ed) and slope (− 1/ E0 Ed) of the fitted curves of Fig. 10b and given in Table 5.

It is clear from Table 5 that both E0 and Ed are increased upon increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. Based on the calculated values of E0 and Ed, the interaction strength (f) between electromagnetic radiation and material, static refractive index (n0), static dielectric constant (εs) of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are estimated by the following equations and represented in Table 5 [48].

It is found that all these parameters are improved with increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles, indicating that the microstructure of PVC/PMMA matrix has been improved, and thus the optical response of the PVC/PMMA will be enhanced. The transition moments of the optical dispersion spectra (M–1) and (M–3) are evaluated to investigate the material-light interaction process by the following equations:

and

It is found the M–1 and M–3 are enhanced with increasing AgO content. Since, these parameters depend on Ed and Eo, and Ed is larger than Eo, so, M–1 and M–3 should have the similar trend of Ed. Moreover, M–1 and M–3 are found to increase with decreasing the band gap energy. This is due to the fact that, the oscillator energy (Eo) is proportional to the frequency of the optical transition [40]. Since Ed is related to the chemical bonding and charges distribution in each unit cell and which ensures the dependence of the optical properties on the structure of the material. Thus, the high values of Ed and transition moments indicate that the structure of PVC/PMMA matrix is modified. This will enhance the light-materials optical response.

In the infinite wavelength range, the UV/Vis spectra are analyzed to evaluate other optical parameters such as, average interband oscillator wavelength (λo) and average oscillator strength (So). Thus, the data below the absorption edge are taken into account for the analysis after introducing the single term Sellmeier oscillator as follows [49]:

and

Based on Eq. 12, (n2-1)−1 is plotted against λ−2, as shown in Fig. 10c. According to Eqns. (12) and (13) values of λo and So are determined from slope and intercept of fitted curves of Fig. 10c and demonstrated in Table 5. The lattice dielectric constant (εL) is estimated in terms of the refractive index data of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites, as follows:

where e is the electronic charge, c is the light speed, εo is the free space permittivity, N is the charge carriers concentration, and m* is the electron effective mass, respectively. Figure 11a represents the behavior of n2 against λ2 for our investigated samples. εL and (N/m*) values are calculated from intercepts and slopes of the fitted curves of Fig. 11a, and tabulated in Table 5. From Table 5, we can see that values of εL are higher than the values of εs. This difference between them can be related to the increased concentration of charge carriers and polarization that results after exposing the material to the incident photons, as reported previously for polymeric materials [50]. The obvious change in the values of Eo, Ed, εs and n0 indicates an increase in charge transfer between PVC/PMMA blend and AgO nanoparticles and an increase in the degree of disorder in the PVC/PMMA host matrix. When the electron damping coefficient < < ω in the transparency range, the Eq. (14) will take the following form:

where ωp and ω are the plasma frequency and angular frequency, respectively. ωp values are evaluated using the following eqn. and listed in Table 5.

The imaginary part (εi) of the dielectric constant can be expressed in terms of the incident photon wavelength as follow:

where τ is the relaxation time. Figure 11b represents the dependence of εi on λ3. The relaxation time (τ) values of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites are calculated using slope of the fitted lines of Fig. 11b according to Eq. 17 and listed in Table 5. Also, the values of optical mobility (μopt) and optical resistivity (ρopt) are estimated and summarized in Table 5 using the following eqns. [51]:

Linear/Nonlinear optical parameters

Sufficiently intense illumination of materials induces a nonlinear polarization response to the electric field of light. It is important to determine the nonlinear optical parameters of materials when fabricating frequency conversion and optical switching devices, which constitute an important sector of integrated photonics. The nonlinear polarization as a function of the electric field is represented as follows [52]:

where χ(1) is the first order linear optical susceptibility whereas, χ(2) and χ(3) are the second and third order nonlinear optical susceptibilities. χ(3) is taken into account as a very important nonlinear optical coefficient for many applications such as high-capacity communication systems [53]. Based on Miller’s rule, different empirical relations are conducted to estimate these optical parameters, as follows [54]:

and

The values of χ(1), χ(3) and n2 are demonstrated in Table 6 as a function of AgO nanoparticles.

Figure 12 displays the behavior of χ(1), χ(3) and n2 against AgONPs content. It can be noticed that the χ(1), χ(3) and n2 are raised nonlinearly upon increasing the AgONPs content. This behavior refers to the increase in linear/nonlinear optical properties with increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. This can be attributed to the increased number of free carriers in the PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites. The high values of linear/nonlinear parameters can make the materials we studied a good candidate for fabrication the low-power devices for the communication applications.

Optical dielectric properties

The dielectric properties of polymeric materials have been studied to suggest their possible use in related fields such as super-capacitor and energy storage devices. Complex dielectric constant (ε*) is expressed as follows:

where εr and εi are the real and imaginary components of the complex dielectric constant and are represented as follows [55]:

It is known that (εr) relates to the dispersion of traveling light associated with the movement of electrons within the material, while (εi) describes the rate of dissipated energy of electromagnetic radiation transmitted throughout the material.

Figure 13(a and b) represents the dependence of εr and εi on the wavelength. It is clear from the plot, εr has higher values in the UV region and then decreased upon increasing the wavelength. Also, as the AgO nanoparticles content increased, εr of the nanocomposite samples is increased compared to the pure PVC/PMMA blend. The change in εr values of PVC/PMMA upon loading with AgO nanoparticles is attributed to the increase in both charge carriers and density of localized states formed between HOMO and LUMO after doping. It is also found that εi increases with increasing wavelength as well as increasing AgO nanoparticle content. The change in εi values is due to the change in the dipole motion [14].

Electrical susceptibility

The electrical susceptibility (χe) and relative permittivity (εre) of the materials can be evaluated using the following Equations. [56]:

Figure 14(a and b) represents the variation of χe and εre against wavelength of the PVC/PMMA blend and PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposite samples. It is observed that both χe and εre generally decrease with increasing wavelength values, while they increase upon increasing AgO content. This increase is due to increased electron mobility and more defects between HOMO-LOMO gap leading to an increased density of localized states [57].

VELF and SELF

In addition, the volume and surface energy loss functions (VELF and SELF) reveal a lot of information about electron transfers across the bulk and surface of the materials, respectively. VELF and SELF are estimated using the following eqns. [48]:

The dependence of VELF and SELF on wavelength is plotted in Fig. 15(a and b). It is clear that both VELF and SELF are decreased sharply in the UV region and started to increase again with the wavelength in the visible region. Generally, VELF values are found to be higher than the SELF values for all samples. Incorporation of AgO nanoparticles may lead to modification in the structure of the blend which in turn may affect the dipole mobility of the polymer and the interactions of the polymer electrons with light.

It is worth noting that the VELF and SELF values are enhanced upon increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles in the PVC/PMMA host matrix, confirming that the increase in the number of defects is due to the strong interactions of AgO nanoparticles with the host polymer. Similar behavior has been reported for the polymeric material previously in the literature [58].

Optical conductivity

Optical conductivity (σopt) is one of the most important optical parameters for studying the electronic states of the materials. It expresses the response of the material in terms of increasing conductivity upon absorption of electromagnetic radiations. The optical conductivity (σopt) and electrical conductivity (σe) of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomosites are evaluated using the following eqns. [59]:

Figure 16(a and b) displays the dependence of σopt and σe on the wavelength. It is noted that optical and electrical conductivities change differently. It is found that the highest value of optical conductivity is at the shortest wavelengths, while it decreases with increasing wavelength. At lower wavelength (higher photon energy), a higher absorption value leads to an increase in charge transfer excitation and hence an increase in the optical conductivity.

It is also worth noting that as the AgO nanoparticles content increases, the optical conductivity values increase from 1.34 × 1011 s−1 for PVC/PMMA blend to 3 × 1012 s−1 for PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO nanocomposite at λ = 700 nm in the visible region. Hence, due to the strong interactions between AgONPs and PVC/PMMA matrix, the σopt is enhanced. The enhancement of σopt with AgO nanoparticles content is related to the higher density of the localized states in the band structure. The rise in σopt of the PVC/PMMA blend upon increasing AgONPs content could be related to the reduction of optical band gap and increased absorption coefficient [60]. The optical conductivity performance of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites makes these nanostructures suitable for many nanoelectronics and optical devices. On the other hand, the electrical conductivity is enhanced with increasing in both wavelength and the AgONPs content, and the highest value of electrical conductivity in the order of 125 S/m, as shown in the Fig. 16b, confirms the semi-conductive nature of these samples.

Antibacterial activity

Figure 17(a–c) displays the antibacterial activity of PVC/PMMA and PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites against Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria and Gram-positive (S. aureus and B. subtilis) bacteria. The inhibition zone diameter (inhibition length) is used to estimate the antibacterial ability of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites against Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria and Gram-positive (S. aureus and B. subtilis) bacteria as illustrated in Fig. 18(a–c). The bacterial cell consists of a negatively charged membrane due to the presence of phospholipids and teichoic acids in the Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively.

It can be seen that pure PVC/PMMA polymer blend displays no visible antibacterial activity. In contrast, the nanocomposite samples containing AgONPs exhibited significantly enhanced antibacterial performance. It is found that AgONPs are more efficient against E. coli than S. aureus and B. subtilis. This difference in activity against these different types of bacteria is related to the chemical and structural compositional differences of the surface of the cells. Gram-negative bacteria are characterized by having a complex cell wall structure, as well as the presence of a layer of peptidoglycan between the outer membrane and the cytoplasmic membrane, while Gram-positive bacteria have a single cytoplasmic membrane and a thick wall containing multilayered peptidoglycan [61]. However, the results depend mainly on the shape and size of nanoparticles. As expected, the antimicrobial activity will enhanced with increasing the content of AgONPs. Similar behavior is published previously in the literature [62,63,64].

The antimicrobial activity of silver oxide nanoparticles may be related to various reasons. First, AgONPs can lead to DNA damage within bacteria. Second, the dissolution of silver nanoparticles leads to the production of antimicrobial Ag2+ ions, which react with thiol-containing proteins in the cell wall and thus will affect their functions. Third, AgONPs are likely to adhere to the bacterial surface and thus change the properties of the membrane [65].

When AgONPs come into contact with bacterial strains, they produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2, OH− and O2−, as shown in Fig. 19. These ROS can destabilize the plasma membrane potential of bacteria, deplete intracellular adenosine triphosphate levels, and ultimately lead to bacterial cell death. The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a strong oxidizing agent and is more reactive than oxygen molecules, which is harmful to the cells of living organisms. The generated H2O2 destroys the bacteria cell membrane, produces a type of infection, and inhibits cell growth or kills them [66].

Conclusion

The structure, optical and antibacterial properties of the PVC/PMMA blend are controlled by the AgO nanoparticles content. XRD analysis exhibited that the crystal size of AgONPs is ranged from 32.85 to 78.41 nm. Investigation of FTIR spectra exhibited that the characteristic bands of PVC/PMMA blend are strongly affected in their position and intensity. This behavior is attributed to the interaction between the AgONPs and the functional groups of the polymer blend. Analysis of UV/Vis spectra exhibited a significant decrease in the transmission and an increase in the absorption of the nanocomposite samples with increasing the content of AgONPs. The incorporation of AgO nanofillers into the host matrix of PVC/PMMA blend resulted in a reduction of the direct/indirect energy gap from (5.21/4.92) to (4.86/3.90) eV, making these nanocomposites strong candidates for polymer-optoelectronics applications. This reduction is attributed to the creation of new localized states. The analysis of SOM showed that linear and nonlinear optical parameters are PVC/PMMA/AgO nancomposites are increased nonlinearly upon increasing the content of AgO. The highest values of εr and σopt are obtained for PVC/PMMA blend with increasing the content of AgO nanoparticles. PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites also exhibited higher values of SELF and VELF in the UV/visible range. Many fields, including, telecommunications, materials science and biophotonics can be nominated for loaded polymer blend. The study of antibacterial activity of PVC/PMMA/AgO nanocomposites against Gram positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli) revealed that the antibacterial of these nanocomposites is improved with increasing the content of AgONPs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Massey, L. K. Permeability Properties of Plastics and Elastomers: a Guide to Packaging and Barrier Materials (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Li, Z. et al. PMMA/MWCNT nanocomposite for proton radiation shielding applications. Nanotechnology 27, 234001 (2016).

Cao, D. et al. Gamma radiation shielding properties of poly (methyl methacrylate)/Bi2O3 composites. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 2613–2619 (2020).

Kikuchi, Y. et al. Design of recycling system for poly (methyl methacrylate)(PMMA). Part 2: process hazards and material flow analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 19, 307–319 (2014).

Migahed, M. D., Ishra, M., El-Khodary, A. & Fahmy, T. Compatibility of polyacrylonitrile-butadiene with polyvinylchloride as explored by thermally stimulated depolarization current. Polym. Test 12, 335–349 (1993).

Ahmed, M. T. & Fahmy, T. Distributed relaxations in PVC/PEMA polymer blends as revealed by thermostimulated depolarization current. Polym. Test. 18, 589–599 (1999).

Fahmy, T. & Ahmed, M. T. Alpha relaxation study in poly(vinyl chloride)/ poly(ethyl methacrylate) blends using thermally stimulated currents. Polym. Int. 49, 669–677 (2000).

Ahmed, M. T. & Fahmy, T. Study of the relaxation phenomenon of Poly(vinyl chloride-co-vinylacetate-co-2-hydroxypropyl acrylate)/Poly(methyl methacrylate) blends using TSDC-TS technique: dipole-dipole interaction approach. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 59, 98–104 (2011).

Varnell, D. F., Moskala, E. J., Painter, P. C. & Coleman, M. M. On the application of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to the elucidation of specific interactions in miscible polyester-poly(vinyl chloride) blends. Polym. Eng. Sci. 23, 658–662 (1983).

Rita, A., Sivakumar, A., Dhas, S. S. J. & Dhas, S. A. M. B. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of silver oxide (AgO) nanoparticles at shocked conditions. J. Nanostr. Chem. 10, 309–316 (2020).

Limbitot, M., Kalyane, S., Sharanappa, N., Manjula, S. & Evale, B. Electrical and dielectric studies of silver oxide doped polyaniline [AgO/PANI] nanocomposite. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 3, 87–93 (2018).

Sagadevan, S. Synthesis, Structural, surface morphology, optical and electrical properties of silver oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 9, 37–49 (2016).

Nie, S. et al. Thermal oxidative degradation kinetics of novel intumescent flame-retardant polypropylene composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 120, 1183–1191 (2015).

Abdelfattah, E. M. et al. Enhancement of the structure, thermal, linear/nonlinear optical properties, and antibacterial activity of poly (vinyl alcohol)/Chitosan/ZnO nanocomposites for Eco-friendly applications. Polymers 15, 4282–4325 (2023).

Wang, W., Zhang, B., Jiang, S., Bai, H. & Zhang, S. Use of CeO2 nanoparticles to enhance UV-shielding of transparent regenerated cellulose films. Polymers 11, 458–514 (2019).

Bharathi, D., Ranjithkumar, R., Chandarshekar, B. & Bhuvaneshwari, V. Preparation of chitosan coated zinc oxide nanocomposite for enhanced antibacterial and photocatalytic activity: as a bionanocomposite. Inter. J. Biological Macromole. 129, 989–996 (2019).

Su, Z. et al. Chitosan/silver nanoparticle/graphene oxide nanocomposites with multi-drug release, antimicrobial, and photothermal conversion functions. Materials 14, 2351–2417 (2021).

Strzałka, M. Z. et al. Silver nanoparticles on chitosan/silica nanofibers: characterization and antibacterial activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 166–220 (2020).

Shinde, S. et al. Synthesis of chitosan-coated silver nanoparticle bioconjugates and their antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Appl. Sci. 11, 9340 (2021).

Fahmy, T. & Ahmed, M. T. Thermal induced structural change investigations in PVC/PEMA polymer blend. Polym. Test. 20, 477–484 (2001).

Kumar, G. A., Reddy, M.V.R., Reddy, K. N., Structural and Optical Properties of AgO Thin Films Grown by RF Reactive Magnetron Sputtering Technique. Proceedings of the "International conference on Advanced Nanomaterials & Emerging Engineering technologies (ICANMEET-2013) organized by Sathyabama Uni., Chennai, India In association with DRDO, New Delhi, India, 24-26th, July, (2013)

Suresh, R., Ponnuswamy, V. & Mariappan, R. Effect of annealing temperature on the microstructural, optical and electrical properties of CeO2 nanoparticles by chemical precipitation method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 273, 457–464 (2013).

Rajendran, S. & Uma, T. Effect of ZrO2 on conductivity of PVC–LiBF4–DBP polymer electrolytes. Mater. Lett. 44(3–4), 208–214 (2000).

Li, Y. H., Shang, X. Y. & Li, Y. J. Fabrication and characterization of TiMoCu/PMMA composite for biomedical application. Mater. Lett. 270, 127744 (2020).

Sain, S. et al. Synthesis and Characterization of PMMA-Cellulose Nanocomposites by In Situ Polymerization Technique. Synthesis and characterization of PMMA-cellulose nanocomposites by in situ polymerization technique. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 126, 127–134 (2012).

Soman, V. V. & Kelkar, D. S. FTIR studies of doped PMMA-PVC blend system. Macromol. Symp. 277, 152–161 (2009).

Abdel-Fattah, E., Alharthi, A. I. & Fahmy, T. Spectroscopic, optical and thermal characterization of polyvinyl chloride-based plasma-functionalized MWCNTs composite thin films. Appl. Phys. A 125, 475–478 (2019).

Ramesh, S., Leen, K. H., Kumutha, K. & Arof, A. K. FTIR studies of PVC/PMMA blend based polymer electrolytes. Spectrochimica Acta Part A 66, 1237–1242 (2007).

Lu, P. & Hsieh, H. L. Cellulose nanocrystal-filled poly(acrylic acid) nanocomposite fibrous membranes. Nanotechnol. 20, 415604 (2009).

Ennis, C. P. & Kaiser, R. I. Mechanistical studies on the electron-induced degradation of polymethylmethacrylate and Kapton. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 14902–14915 (2010).

Wu, J. et al. TG/FTIR analysis on co-pyrolysis behavior of PE. PVC PS Waste Manag. 34, 676–682 (2014).

Trinh, K. T. L., Thai, D. A., Chae, W. R. & Lee, N. Y. Rapid fabrication of poly (methyl methacrylate) devices for lab-on-a-chip applications using acetic acid and UV treatment. ACS Omega 5, 17396–17404 (2020).

Nooma, S. & Magaraphan, R. Core–shell natural rubber and its effect on toughening and mechanical properties of poly (methyl methacrylate). Polym. Bull. 76, 3329–3354 (2019).

Manikandan, V. et al. Green synthesis of silver oxide nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against dental pathogens. Biotech 7, 72–80 (2017).

Cabrera, L. A., García, P. F. & Berensmeier, S. Bio-nano interactions: binding proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids onto magnetic nanoparticles. Biomaterials Res. 25, 12–18 (2021).

Uznanski, P., Zakrzewska, J., Favier, F., Kazmierski, S. & Bryszewska, E. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from (bis)alkylamine silver carboxylate precursors. J. Nanopart. Res. 19, 121 (2017).

Nadimicherla, R., Kalla, R., Muchakayala, R. & Guo, X. Effects of potassium iodide (KI) on crystallinity, thermal stability, and electrical properties of polymer blend electrolytes (PVC/PEO:KI). Solid State Ionics 278, 260–267 (2015).

Vellingiri, M. M. et al. Mycofabrication of AgONPs derived from Aspergillus terreus FC36AY1 and its potent antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-angiogenesis activities. Molecul. Bio. Reports 48, 7933–7946 (2021).

Urbach, F. The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids. Phys. Rev. 92, 1324 (1953).

Borah, D. J. & Mostako, A. T. T. Investigation on dispersion parameters of Molybdenum Oxide thin films via Wemple–DiDomenico (WDD) single oscillator model. Appl. Phys. A 126, 818–913 (2020).

Rahman, M. M. et al. Investigation of the post-annealing electromagnetic response of Cu-Co oxide coatings via optical measurement and computational modelling. RSC Adv. 7, 16826–16835 (2017).

Baraker, B. M. & Lobo, B. Dispersion parameters of cadmium chloride doped PVA-PVP blend films. J. Polym. Res. 24, 84 (2017).

Tauc, J. Amorphous and Liquid Semiconductors (Plenum Press, 1974).

Malimabe, M. A. et al. Characterization of the incorporated ZnO doped and co-doped with Ce3þ and Eu3þ nanophosphor powders into PVC polymer matrix. J. Mol. Struc. 1202, 1227339 (2023).

Rajanna, K., Madhukar, B. S., Babu, S. D., Lokesh, Y. V. & Ningappa, K. S. Investigation of UV-blocking and photon-down conversion characteristics of PMMA@ CH3NH3PbBr3:WO3 polymer nanocomposites. J. Luminescence. 277, 120977 (2025).

Fink, D. et al. Carbonaceous clusters in irradiated polymers as revealed by UV-Vis spectrometry. Radiat. Eff. Def. Solids 133, 193–208 (1995).

Ahmed, M. T. et al. Linear and Non-linear optical parameters of copper chloride doped Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) for Optoelectronic applications. Egypt. J. Chem. 65, 99–108 (2022).

Wemple, S. H. Refractive-index behavior of amorphous semiconductors and glasses. Phys. Rev. B. 7, 3767 (1973).

Wemple, S. H. & Domenico, M. D. Behavior of the electronic dielectric constant in covalent and ionic materials. Phys. Rev. B. 3, 1338 (1971).

Elmahdy, M. M., Ahmed, M. T., Aldhafeeri, K. A., Azzam, M. A. & Fahmy, T. Thermal degradation and optical characteristics of plasticized poly(vinyl chloride-co-vinyl acetate-co-2- hydroxypropyl acrylate) terpolymer. J. Mater. Sci: Mater Electron. 33, 23639–23658 (2022).

Domenico, M. D. & Wemple, S. H. Oxygen-octahedra ferroelectrics I theory of electro-optical and nonlinear optical effects. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 720–734 (1969).

Frumar, M., Jedelský, J., Frumarova, B., Wagner, T. & Hrdliˇcka, M. Optically and thermally induced changes of structure, linear and non-linear optical properties of chalcogenides thin films. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 326, 399–404 (2003).

Cotter, D. et al. Nonlinear optics for high-speed digital information processing. Science 286, 1523–1528 (1999).

Ticha, H. & Tichy, L. J. Semiempirical relation between non-linear susceptibility (refractive index), linear refractive index and optical gap and its application to amorphous chalcogenides. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 4(2), 381–386 (2002).

Habib, A., Metwally, M. M., Fahmy, T. & Sarhan, A. Enhancement of optical and piezoelectric properties of P(Vinylidene fluoridehexafluoropropylene)/N,N-Dimethyl-4-nitro-4-Stilbenamine composites for optoelectronic applications. Polymer-Plastics Technol. Mater. 61, 2001–2015 (2022).

Braslavsky, S. E. Glossary of terms used in photochemistry (IUPAC recommendations 2006). Pure Appl. Chem. 79, 293 (2007).

Elhendawi, H., Ramadan, R. M., Abdel-Aziz, M. S., Fahmy, T. & Ali, A. M. Enhancement of the structure and linear/nonlinear optical properties of PVA/chitosan/Ag nanocomposites for optoelectronic and antibacterial applications. Sci. Rep. 15, 27235–27319 (2025).

Elsharkawy, W. B., Elzanaty, H., Elqahtani, Z. M., Fahmy, T. & Sarhan, A. Investigation of thermal, optical properties, AC conductivity and broadband dielectric spectroscopy of poly(ethyl methacrylate)/poly(vinyl chloride) polymer blend. Results Mater. 23, 100621–100622 (2024).

Banerjee, M., Jain, A. & Mukherjee, G. S. Spectroscopic evaluation of optical parameters of a transition metal salt filled polymer material. Def. Sci. J. 68, 225–231 (2018).

Sharma, N., Sharda, S., Sharma, V. & Sharma, P. Optical analysis of Ge19Se81− xSbx thin films using single transmission spectrum. Mater. Chem. Phys. 136, 967–972 (2012).

Ma, X. Y. & Zhang, W. D. Effects of flower-like ZnO nanowhiskers on the mechanical, thermal and antibacterial properties of waterborne polyurethane. Polym. Deg. Stab. 94, 1103–1109 (2009).

Khan, M. et al. Search for effective approaches to fight microorganisms causing high losses in agriculture: application of P. lilacinum metabolites and mycosynthesised silver nanoparticles. Biomolecules 12, 174–213 (2022).

Lange, A. et al. Nanocomposites of graphene oxide-silver nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial activity: mechanism of action and medical textiles coating. Materials 15, 3122–3217 (2022).

Sarhan, A. & Fahmy, T. Optical properties, antibacterial activity, and relaxation behavior investigation of chitosan/green synthesized silver nanoparticles by thermally stimulated depolarization current technique. Polym. Sci. Series B 63, 578–590 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of guanidinylated chitosan. Carbohydrate Polym. 67, 66–72 (2007).

Chen, S. J. et al. Structural and optical properties of uniform ZnO nanosheets. Adv. Mater. 17, 586–590 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdoulaziz university project number: PSAU/2025/1447. Also, Z. M. Elqahtani expresses her gratitude to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (Grant No. PNURSP2025R124), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Funding will be provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, Validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation: W. B. Elsharkawy, A. M. Elnemr, Z. M. Elqahtani, H. Elhendawi, M. M. Metwally, T. Fahmy; Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, writing—review and editing: W. B. Elsharkawy, A. M. Elnemr, T. Fahmy; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsharkawy, W.B., Elnemr, A.M., Elqahtani, Z.M. et al. Tuning the structural, optical properties and antibacterial activity of poly(vinyl chloride)/poly(methyl methacrylate)/silver oxide nanocomposites for potential optoelectronic and medical applications. Sci Rep 15, 41722 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23164-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23164-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Immobilization of a New Synthesized Hydrazine-Pyrazole Based onto Chitosan Biopolymer for Efficient Uptake of Copper Ions

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2026)

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA,

PVC/PMMA,  PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/1 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,

PVC/PMMA/7.5 wt% AgO,  PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.

PVC/PMMA/10 wt% AgO.