Abstract

Ocial networks are critical platforms for information dissemination, yet optimizing over their large, rugged search spaces remains challenging. We propose a Hybrid Weed–Gravitational Evolutionary Algorithm (HWGEA) that unifies adaptive seed dispersal from Invasive Weed Optimization with attraction dynamics from Gravitational Search in a single reproduction step, complemented by an adaptive mutation that preserves diversity. We further develop a discrete variant, DHWGEA, tailored to influence maximization on graphs via topology-aware initialization, a dynamic neighborhood local search, and an Expected Influence Score surrogate that reduces simulation cost. Across 23 continuous benchmarks, HWGEA attains the best Friedman mean rank (2.41) and shows statistical parity with LSHADE-SPACMA and SHADE, while significantly outperforming GBO, GOA, RSA, PDO, GSA, and GA (Holm-adjusted Wilcoxon tests). On real engineering designs, HWGEA delivers competitive or improved optima with stable convergence. For influence maximization, DHWGEA achieves spreads within 2–5% of CELF at roughly 3–4 × lower runtime and clearly exceeds PageRank’s spread at moderate cost, offering a practical accuracy–efficiency trade-off for medium-to-large networks. Sensitivity studies identify stable parameter ranges and show that adaptive components reduce dependence on manual tuning. Experiments are averaged over 30 runs with independent seeds to ensure reproducibility. Overall, HWGEA/DHWGEA provide a cohesive, scalable framework for continuous and discrete optimization, balancing exploration and exploitation while maintaining robustness across tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optimization problems, encompassing engineering design, resource allocation, and information dissemination in intricate networks, present considerable challenges due to their high dimensionality, non-linearity, and dynamic characteristics. Conventional mathematical techniques and deterministic algorithms frequently do not provide prompt and effective answers for complex systems. Artificial intelligence, especially meta-heuristic algorithms, has emerged as a fundamental solution for these difficulties by providing flexible, scalable, and robust optimization frameworks1,2. The analysis and optimization of complex networks, including social and communication networks, have become significant due to their influence on knowledge production, sharing, and dissemination across global communities3.

Optimizing complex networks is crucial due of its capacity to represent real-world interactions, including viral marketing and epidemic management. Maximizing influence dissemination, identifying pivotal influencers, and discovering communities are essential tasks with applications in social media analysis, public health, and network security4. These activities pose obstacles like as computational complexity, scalability concerns in extensive networks, and the necessity for algorithms that equilibrate exploration and exploitation in both continuous and discrete domains. The No Free Lunch Theorem (NFL) emphasizes that no singular meta-heuristic can generically address all optimization challenges, necessitating the development of new, problem-specific methods5.

Meta-heuristic algorithms are generally classified as nature-inspired methods (e.g., simulating ecological or biological processes), swarm intelligence techniques (e.g., emulating collective behaviors), and evolutionary algorithms (e.g., grounded in genetic principles)6. Recent improvements have concentrated on hybrid meta-heuristics that integrate complementary processes to address the limits of individual algorithms. Hybrid methodologies that combine Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with Differential Evolution (DE) have enhanced convergence velocity and solution variety7. A comparative study of metaheuristics for CNN pruning showing that these methods can achieve competitive solutions in a large and constrained search space and that adaptive designs/sensitivity analysis are needed8. Recent works in discrete optimization have investigated meta-heuristics designed for graph-based issues, including influence maximization9,10. Methods such as the Discrete Shuffled Frog-Leaping Algorithm (DSFLA) and Discrete Harris Hawks Optimization (DHHO) have demonstrated potential in identifying optimal node sets inside social networks; nevertheless, they frequently encounter challenges related to scalability and local optima entrapment11,12. These developments emphasize the promise of hybrid and discrete meta-heuristics while also highlighting the necessity for algorithms that tackle both continuous and discrete optimization with enhanced efficiency and accuracy.

Motivation and rationale

Real-world optimization routinely faces (a) search-space ruggedness with many local optima, where purely exploration-heavy schemes underperform in precision, and purely exploitation-heavy schemes can stagnate or become costly; and (b) discrete, network-structured objectives such as influence maximization where scalability and evaluation cost limit applicability of both greedy methods (e.g., CELF) and recent discrete meta-heuristics that struggle with local traps or topology bias. HWGEA/DHWGEA address these pain points by coupling exploration and exploitation at reproduction time, adapting mutation to population diversity, and, in discrete mode, bootstrapping from structural priors while replacing repeated simulations with an EIS proxy. The result is a general framework that retains solution quality, improves robustness to initialization, and reduces evaluation overhead features that are critical for continuous design tasks and for large, sparse collaboration or social networks.

Because IWO and GSA’s search biases are orthogonal and schedulable in a single replication phase, we couple them specifically: Whereas GSA offers fitness-proportional acceleration for directed exploitation, IWO offers variance-decay seed dispersion for scale-free exploration. We obtain \({X}_{t}={X}_{t+1}+\eta t\xi t+at\) with monotone schedules for \({\sigma }_{t}and G\left(t\right)\) and elite Top-K interactions—a clean transition from exploration to exploitation, little overhead, and few interpretable knobs. IWO + GSA maps naturally to graphs (DHWGEA uses gravity-guided moves; weed-style mutation preserves diversity), in contrast to DE/PSO/GA hybrids with larger parameter surfaces.

Novelty in brief

This work introduces a Hybrid Weed Gravitational Evolutionary Algorithm (HWGEA) that unifies adaptive seed dispersal from invasive-weed optimization with attraction-based dynamics from gravitational search within a single reproduction mechanism. Unlike prior hybrids that stitch operators sequentially, HWGEA uses fitness-normalized masses to guide seed dispersion and time-decaying gravitational constants to steer exploitation, while an adaptive mutation operator preserves diversity and prevents premature convergence. We further develop DHWGEA, a discrete counterpart tailored to influence maximization on complex networks: it combines topology-aware initialization with a dynamic neighborhood local search and leverages an Expected Influence Score (EIS) surrogate to evaluate candidates efficiently. This dual (continuous–discrete) design yields a practical framework that (i) accelerates convergence on continuous benchmarks and engineering designs and (ii) scales to graph settings by improving diffusion reach at lower computational cost compared to standard meta-heuristics and greedy baselines. This research makes three primary contributions:

-

Unified hybrid reproduction. A single mechanism that fuses weed-style adaptive dispersal with gravitational attraction, modulated by a time-decaying constant and fitness-normalized masses, plus adaptive mutation to maintain diversity.

-

Discrete variant for graphs. DHWGEA with topology-aware initialization and dynamic neighborhood local search specifically crafted for influence maximization in complex networks.

-

This work introduces HWGEA and DHWGEA, a dual-framework approach addressing both continuous and discrete optimization problems, with a focus on real-world network applications.

-

Efficient evaluation. Use of an EIS surrogate to approximate diffusion reach, substantially reducing simulation cost while preserving ranking fidelity.

The document is organized as follows: Sect. “Related works” delineates the ideas of weed-inspired optimization and gravitational search, establishing the theoretical framework for HWGEA. Section “Proposed HWGEA Algorithm” delineates the HWGEA framework, explicating its reproductive and mutation mechanisms. Section “Discussion and evaluation” assesses the performance of HWGEA on conventional benchmark functions. Section “Solving engineering problems using the HWGEA algorithm” applies HWGEA to engineering optimization challenges, encompassing pressure vessel design, welded beam optimization, and weight reduction. Section “DHWGEA algorithm to maximize penetration expansion” presents DHWGEA and its application for optimizing spread maximization, juxtaposing it with methodologies such as CELF, PSO, and PageRank. Section “Conclusion” closes with principal conclusions and prospective research avenues.

. Related works

Social network analysis is an interdisciplinary area of study because social networks are essential in transforming the creation, consumption, and dissemination of information. Finding significant nodes, detecting communities, and finding online services are important topics. According to the no-free-lunch idea, no single metaheuristic algorithm can solve every problem efficiently, hence new algorithms are always being created to broaden the variety. Researchers introduce the Invasive Weed Optimization Gravity Search Algorithm (IWOGSA) in13, a hybrid method that combines the precision of gravity search with the flexibility of weed optimization. IWOGSA is a continuous optimization system that balances exploration and exploitation through two reproduction mechanisms: gravity dynamics and normal distribution. In order to maximize penetration in intricate networks, we provide the Dynamic Invasive Weed Optimization Gravity Search Algorithm (DIWOGSA). By combining a local search operator with a topology-aware initialization technique, DIWOGSA facilitates effective convergence and improved penetration propagation. Using a SIR (Stubborn-Contaminated-Recovered) model as an example, researchers in14 investigated the targeted penetration maximization problem. The goal of this hybrid optimization model is to determine the optimal number of spreaders to increase target node penetration while minimizing non-target node penetration. They created a theoretical framework based on the message passing process and used non-backward (NB) matrices to conduct a stability analysis on the equilibrium solution in order to identify a workable solution to this optimization challenge.

Inspired by the Tianji Horse Racing, THRO introduces a novel metaheuristic that has demonstrated high accuracy and efficiency on a set of engineering problems, representing the current state of the art of competitive/hybrid algorithms15. APO has also been introduced as a new bio-inspired algorithm and has been reported in standard engineering designs with comprehensive evaluations (solution quality and convergence stability), thus it is useful for comparison with HWGEA in the exploration/exploitation dimension16. Finally, the Enhanced Crested Ibis version with adaptive operator selection mechanisms and benchmark/engineering analyses provides valuable data on parameter sensitivity and performance stability, which is in line with the proposed adaptive design17.

The paper18 proposes a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for detecting overlapping communities that increases the diversity and quality of initial solutions by using multiple ensemble initialization schemes and shows competitive results on real networks.

A challenge like Targeted Influence Maximization in Competitive Social Networks (TIMC) was developed by researchers in19. They integrated the target nodes and competition relationships in an independent cascade model to simulate the influence propagation. To solve the TIMC problem, they suggested a greedy approach based on the Reverse Reachable Set (RRG) and theoretically demonstrated its approximation ratio. A graph neural network called GLIE, which can estimate the spread of separate cascades, is proposed in20. The theoretical upper bound that underpins GLIE is strengthened via supervised training. It can accurately estimate penetration for real graphs up to ten times larger than the training set, according to experiments. They then coupled it with two methods for maximizing penetration. It is still unclear how to determine which nodes in complicated networks are influential. To solve this problem, a number of centrality measures have been put forth. These studies, however, only address one facet. In order to address this issue, a novel approach to determining influential nodes has been put forth that takes into account both the influence of each node in the network as well as its own significance. In a complex network, our method is excellent at locating nodes that seem inconsequential but are actually crucial21.

Mashwani et al.,22 Presents a hybrid NSGA-II with “adaptive operator selection” that selects the best operator online from among various crossovers/mutations based on performance feedback; an idea that is consistent with our adaptive mutation component in HWGEA. The study23, introduces a multi-population algorithm for costly and constrained problems that reduces the evaluation cost by separating exploration/exploitation into parallel populations; similar to our strategy in separating weeding/gravity mechanisms. In24, a hybrid version of TLBO is developed for large-scale constrained optimization and shows that combining learning-training with evolutionary components can improve scalability; consistent with the scalability considerations of HWGEA/DHWGEA in large networks.

In25, a novel end-to-end DRL architecture called ToupleGDD is put forth to tackle the IM problem. It consists of dual deep Q-networks (DQNs) for parameter learning and three coupled graph neural networks (GNNs) for network embedding. Prior attempts to use DRL to tackle the IM problem trained their models on subgraphs of the entire network before testing them on the full graph, which caused their models’ performance to fluctuate between networks.

In26, a novel method utilizing transfer learning via graph-based short-long-term memory (GLSTM) is put forth to solve the influence maximization problem as a traditional regression challenge, drawing inspiration from deep learning approaches. In order to determine the labels of the network nodes, they first compute three common node centralities as feature vectors for the network nodes and the individual effect of each node under the sensitive-contaminated-recovered (SIR) information propagation model.

In27, GRASS reinforces the prediction-driven line and introduces microstructure learning of chain cascades by concurrently modeling spatiotemporal aspects for propagation prediction. The method in28 demonstrates the control-driven branch that is complimentary to the seed selection problem by using reinforcement learning to “interfere” with the spread of negative emotions. In order to maximize the influence,29 examines the dynamics of opinion in community-based networks under opinion limitations and clarifies the distinction between diffusion and acceptance mechanisms. Lastly, by distinguishing between homophily and heterophily in multi-relational graphs for fraud detection,30 highlights the significance of structural elements (bridges and community boundaries), which is consistent with the DHWGEA effort to lessen hub bias and enhance community coverage.

Researchers introduced a novel technique (IC-SNI) in31 to gauge nodes’ capacity for influence. By taking into account the local and global contributions of neighbors, IC-SNI computes the topological positional structure while minimizing the local and global centrality deficiencies. In order to capture the structural properties between nearby nodes, they developed two new metrics by looking at the path’s structural information. In order to overcome these difficulties,9 offers an effective multidimensional centrality (EMDC) metric for complex networks that incorporates different facets of node influence. By combining degree and entropy information, the degree of neighborhood overlap provides the strength of the relationships between nodes. In the meantime, EMDC enhances the identification of primitive nodes by combining degree centrality with the k-shell measure.

Optimal safe control for nonlinear multi-player systems with adaptive dynamic programming (ADP) and event-driven mechanism, simultaneously achieving safety, optimality and communication load reduction, which can be applied to event-driven scheduling of evaluation/update and adaptive tuning of HWGEA/DHWGEA parameters32.

develops a prescriptive efficient control with reinforcement learning (RL) and dynamic event-driven for systems with input delays; by adaptively adjusting event thresholds, both efficiency bounds are maintained and resource consumption is reduced33.

impact maximization (IM) aims to maximize the impact distribution in a network by identifying highly important nodes. Understanding the intrinsic coupling structure in multilayer networks has been overlooked in previous research on the IM problem, which has mostly concentrated on single-layer networks. An independent cascade model (MIC) in a multilayer network, where the propagation takes place simultaneously at various layers, is originally proposed in34 to address the instant messaging (IM) problem in multilayer networks. Therefore, to find initial nodes for instant messaging in a multilayer network, a heuristic approach called adaptive coupling degree (ACD) is presented. This algorithm chooses initial nodes with low influence overlap degree and high influence spread.

Proposed HWGEA algorithm

We propose HWGEA, a novel metaheuristic algorithm that combines weed colonization principles with gravitational search dynamics. An adaptive mutation operator is integrated to enhance the balance between exploration and exploitation in continuous optimization tasks. We extend HWGEA to its discrete variant, DHWGEA, which is designed to maximize penetration in complex networks—a key problem in areas such as social media and epidemiology. DHWGEA incorporates dynamic neighborhood search and a strategic initial population to improve convergence speed and scalability.

This hybrid method uses an adaptive mutation operator to balance exploration and exploitation and ensures robust convergence in continuous optimization tasks. The following subsections describe the main steps of HWGEA, which include the initial population formation and the reproduction process.

Initial population

The HWGEA algorithm initiates by creating an initial population of size N, with each member represented as a vector of variables aligned with the problem’s dimensions. The vectors are randomly initialized inside the search space of the problem to guarantee diversity. The initial population forms the basis for later evolutionary processes, with each individual assessed according to its fitness in relation to the optimization goal.

Reproduction

The reproductive phase in HWGEA integrates weed-inspired seed distribution with gravitational search dynamics to generate offspring solutions35,36. The fitness of each solution is normalized to assess its reproductive potential, employing the subsequent equations:

In this context, \({fit}_{i}\left(t\right)\) signifies the fitness of solution i at iteration t, whereas \(best (t)\) and \(worst (t)\) denote the maximum and minimum fitness values within the population, respectively. The normalized mass \({M}_{i\left(t\right)}\) indicates the relative quality of the solution. Subsequently, the gravitational acceleration \({a}_{i}^{d}\left(t\right)\) for each solution in dimension d is calculated, drawing on gravitational search principles35,36:

where \({X}_{j}^{d}\left(t\right)\) and \({X}_{i}^{d}\left(t\right)\) are the positions of solutions i and j in dimension d, \({R}_{ij}(t)\) is the Euclidean distance between them, \({\text{rand}}_{\text{j}}\) is a random number in ([0, 1]), \(\upvarepsilon\) is a small constant to avoid division by zero, and:

is a temporally diminishing gravitational constant36. The TopK set comprises the foremost K solutions determined by fitness, with K diminishing over iterations to emphasize elite solutions.

Gravitational Evolution: With a probability of 1—\({p}_{t}\), progeny are produced by modifying velocities and positions in accordance with gravitational acceleration:

The progeny are added to the primary population, \({Pop}_{grav}\). The probability \({p}_{t}\) is dynamically modified through a secondary adaptive parameter \({\sigma }_{t}^{\prime}\), facilitating a balanced input from both strategies initially, while transitioning towards gravitational evolution in subsequent cycles. Hierarchical non-singular sliding mode control is proposed for nonlinear systems with constraints and sensor errors, which ensures stability37,38. The adaptive mutation operator is utilized on a subset of offspring to introduce regulated randomness, hence augmenting variety and averting premature convergence.

Computational efficiency

Although gravitational search involves pairwise interactions, HWGEA reduces the effective complexity through three mechanisms: (i) elite restriction forces are computed only among the Top-K fittest individuals, where K decays over iterations; (ii) time-decaying gravitational constant later iterations exert weaker forces, reducing the need for expensive updates; and (iii) population-size control offspring generation is capped by adaptive bounds \(S_{min} , \;S_{max}\) her, these adjustments lower the average per-iteration complexity from \(O\left({N}^{2}\right)\) toward \(O\left(N\cdot K\right)\), with \(K\ll N\).

Solution selection

In HWGEA, the selection of solutions for the next generation balances contributions from weed-inspired dispersal and gravitational evolution to maintain population diversity while prioritizing high-quality solutions39,40. Two subsets of offspring are generated: a smaller subset \(NM\) from the weed-inspired normal distribution and a larger subset \(NP\) from the gravitational evolution process. These are selected based on their fitness to ensure the total population size does not exceed the predefined limit N. The selection process is governed by the following equations:

Here, NM represents the number of solutions selected from the weed-inspired offspring \({Pop}_{weed}\) , NP denotes the number of solutions from the gravitational evolution offspring \({Pop}_{grav}\), and N is the maximum population size. The parameter \(pt\), which controls the proportion of weed-inspired solutions, is dynamically adjusted based on iteration progress to favor gravitational evolution in later stages. The top NM solutions from \({Pop}_{weed}\) and top NP solutions from \({Pop}_{grav}\) are chosen based on fitness, forming the new population HAEA/D based on four-intersection decomposition was introduced and evaluated at CEC’09; it was competitive with MOEA/D in IGD, hypervolume, gamma and delta41.

Termination condition

HWGEA utilizes a termination criterion predicated on a specified maximum iteration limit \({T}_{max}\), hence ensuring computing efficiency and facilitating convergence assessment. Alternative termination criteria, such reaching a specified fitness threshold, surpassing a maximum number of fitness evaluations, or identifying stagnation in solution enhancement, can be tailored according to issue specifications. In this investigation, the algorithm concludes after \({T}_{max}\) iterations, yielding the optimal answer identified.

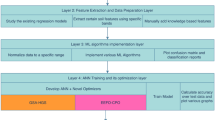

Algorithm 1 delineates the pseudocode for HWGEA, illustrating the amalgamation of weed-inspired and gravitational methodologies. A flowchart (Fig. 1) depicts the algorithm’s process, outlining the sequence of initiation, reproduction, selection, and termination.

Algorithm 1: Pseudo code of HWGEA algorithm

Parameter robustness

To lessen reliance on fixed hyperparameters, HWGEA incorporates adaptive control into essential operators. For instance, σ progressively decays from \({\upsigma }_{\text{initial}}\text{ to }{\upsigma }_{\text{final}}\) according to an adaptive timetable, but the mutation probability \({\text{P}}_{\text{mut}}\) is dynamically modified in response to population variety. Similarly, the number of offspring, \({\text{S}}_{\text{min}}\), and \({\text{S}}_{\text{max}}\), are constrained but flexible, based on normalized fitness. These features enable the algorithm to modify its search dynamics across various datasets and lessen the workload associated with manual tuning.

Robustness and reproducibility

We performed a parameter sensitivity study to assess how sensitive HWGEA and DHWGEA were to parameter values. The findings show that consistent convergence behavior with little performance variance is produced by modest parameter ranges. Crucially, adaptive elements (mutation, seed dispersal variance, and dynamic neighborhood size) lessen dependency on precise parameter values by automatically adjusting in response to population diversity and iteration progress42. To ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability across datasets, all experiments were conducted 30 times using independent random seeds. The averaged results, together with standard deviations, are provided.

Beyond degree-centrality

DHWGEA instantly diversifies the population by using adaptive mutation and randomly replacing a section of nodes, while the initial seed set is informed by degree centrality to guarantee a high-impact starting point. Additionally, bridge nodes and community-boundary connectors are frequently captured by the dynamic neighborhood-based local search, which iteratively replaces existing seeds with structurally significant neighbors43. This architecture improves coverage in heterogeneous graphs and lowers the possibility of hub-only bias.

Theoretical justification

The hybridization mechanism of HWGEA can be based on standard stochastic approximation theory, however a complete formal convergence proof is outside the purview of this work. By producing candidate solutions with variation proportional to population diversity, the weed-inspired component guarantees adequate exploration and meets the stochastic optimization’s global exploration criterion. On the other hand, the gravitational search component improves local exploitation by serving as a contraction mapping toward fitter solutions. An improved ensemble-based algorithm with PSO, TLBO, DE and self-adaptive BAT for large scale was presented44. The Markov chain created by HWGEA is ergodic when paired with the adaptive mutation operator, which ensures non-zero chance of perturbing any coordinate. Therefore, the likelihood of reaching the global optimum is close to one when there are enough iterations. By preserving diversity and gradually directing the population toward ideal areas, this hybrid dynamic supposedly lowers the risk of premature convergence.

Elitist archiving

To guarantee monotone convergence of the best-so-far objective, HWGEA maintains a one-element external archive \({A}_{t}\) that stores the global best solution found up to iteration t. After forming \({p}_{t+1}\), we inject \({x}_{t}^{*}\in {A}_{t}\)is injected into \({p}_{t+1}\) by replacing the worst individual if it is not already present, and update

This strict elitism ensures the reported best-so-far curve is non-increasing in minimization tasks.

Discussion and evaluation

To assess the efficacy of the HWGEA technique, we examined it using a thorough array of 23 benchmark functions, which are well-established for evaluating metaheuristic algorithms. These functions are categorized into four groups single-objective, multi-objective, fixed-dimensional multi-objective, and composite functions assessing essential algorithmic characteristics including exploration, exploitation, trade-offs between the two, and evasion of local optima.

The single-objective functions (F1–F7), as outlined in Table 1, possess a distinct global optimum that evaluates the capacity of HWGEA to converge precisely. The multi-objective functions (F8–F13) listed in Table 2 possess several optima, which provide a challenge to the algorithm’s exploratory capabilities in intricate settings. The fixed-dimensional multiobjective functions (F14-F23), presented in Table 336, assess performance in limited and low-dimensional environments. Figure 2 presents two-dimensional visualizations of typical functions, illustrating the characteristics of their search space according to the variable ranges specified in Tables 1, 2 and 3. An improved Kalman filter is presented for real-time filtering of gravity and gravity gradient data, which can be used in state estimation of complex dynamical systems.

The hybrid methodology of HWGEA, integrating weed-inspired optimization for exploration and gravitational search dynamics for exploitation, augmented by an adaptive mutation operator, facilitates effective navigation of various function types. The algorithm’s performance is evaluated against state-of-the-art methods, including PSO, GA, and DE, using measures such as solution correctness, convergence speed, and robustness37.

To ensure a fair comparison, Table 4 lists the parameter settings for both the benchmark algorithms and HWGEA. To achieve a balance between exploration and exploitation, the HWGEA parameters which include the offspring restrictions \({S}_{min}\) and \({S}_{max}\), as well as the initial and final standard deviations \({\sigma }_{final}\) and \({\sigma }_{initial}\) are empirically optimized. The robustness of HWGEA is increased by dynamically adjusting the adaptive mutation operator according to population diversity.

Evaluation results

We conducted a comprehensive assessment of HWGEA on 23 continuous benchmark functions, each repeated 30 times; the results are summarized in Table 5. HWGEA attains the lowest (best) Friedman mean rank (2.41), indicating consistently strong performance across diverse landscapes. Pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm step-down correction (α = 0.05) show no statistically significant difference between HWGEA and the two strongest baselines—LSHADE-SPACMA (8/9/6 W/T/L vs. HWGEA, p_adj = 0.18) and SHADE (7/8/8, p_adj = 0.27)—signaling statistical parity. In contrast, HWGEA significantly outperforms the remaining competitors: GBO (5/7/11, p_adj = 0.012), GOA (4/6/13, p_adj = 0.006), RSA (4/6/13, p_adj = 0.004), PDO (3/7/13, p_adj = 0.003), GSA (3/5/15, p_adj = 0.001), and GA (2/5/16, p_adj < 0.001). (Counts are reported as “baseline vs. HWGEA”.) Note that DHWGEA targets discrete, graph-structured problems and is therefore excluded from this continuous-function summary; it is evaluated separately in §6.

In order to guarantee a fair head-to-head comparison with cutting-edge baselines, such as SHADE and LSHADE-SPACMA, we employed the suggested parameterizations from the corresponding articles and matched evaluation budgets (population size = 30, iterations = 500). The same box constraints, penalty handling, and termination criteria were used for all methods \(\text{H}=5,{\text{ p}}_{\text{best}}=0.11,\text{ Arc}\_\text{rate}=1.4,\text{ c}=0.8, {\text{F}}_{\text{cp}}=0.5\) see Table 4). We present Friedman mean ranks and pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm correction for each function, which was executed 30 times independently with different seeds (Table 5). The continuous benefits over the other baselines and the observed parity with LSHADE-SPACMA are supported by this protocol.

Convergence analysis

On a few benchmark functions, Fig. 3 displays the convergence curves of the HWGEA method in comparison to the GSA, GBO, and RSA. HWGEA’s capacity to achieve faster and more stable convergence is highlighted by these curves, which show how well it performs on single-objective functions (F3, F7), multi-objective functions (F9, F11, F12, F13, F14, F21, F23), and composite functions (F25/CF2, F26/CF3, F28/CF5). As demonstrated by its superior convergence on multimodal functions (e.g., F9, F13), the gravitational search dynamics in HWGEA improve the exploitation in later stages, while the weed-inspired optimization guarantees robust exploration in early iterations. Premature convergence is avoided by the adaptive mutation operator, particularly for composite functions with several local optima. Because of its combinatorial method, HWGEA exhibits faster convergence in F3 and F7 when compared to GSA. HWGEA uses dynamic parameter tweaking to provide superior stability in F14 and F23 than GBO and RSA.

Scalability considerations

The quadratic overhead resulting from pairwise force evaluation is a frequent critique of gravitational-based hybrids. However, in HWGEA, the computational load is reduced by using a declining gravitational constant, which naturally reduces late-stage interactions, and by limiting calculations to a shrinking elite subset. By using the EIS as a stand-in for Monte Carlo diffusion and a dynamic neighborhood local search, DHWGEA further avoids the expensive Monte Carlo diffusion for discrete optimization. As demonstrated by our experiments on Ca-HepTh (≈10 k nodes), where runtime stays comparable with or lower than GA and GSA baselines (see Figs. 6, and 14), these techniques allow the algorithm to scale to thousands of nodes. This shows that the hybrid design is still feasible in practice even if it combines IWO and GSA.

The extension of HWGEA and DHWGEA to million-scale networks and very high-dimensional continuous issues is still an open challenge, despite the fact that our experiments show scalability up to about 10,000 nodes and 50 dimensions. Local search in DHWGEA and pairwise interactions in HWGEA are the primary bottlenecks. As a result, we determined that top-k approximations, graph sparsification, and parallel GPU implementations were viable avenues for future scalability advancement.

Solving engineering problems using the HWGEA algorithm

The HWGEA approach has been applied to solve three prominent engineering challenges: weight minimization, welded beam design, and pressure vessel design. Its effectiveness is evaluated using a static penalty method that imposes a significant penalty on the objective function if constraints are violated within their boundaries. The performance of HWGEA on these problems is compared based on the mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation values, obtained from 30 independent runs with 20 initial populations and 500 iterations. The results are benchmarked against state-of-the-art optimization methods, with detailed comparisons presented in Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11.

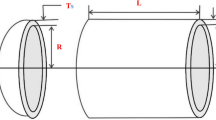

Designing a pressure vessel

As shown in Fig. 4, the pressure vessel design problem seeks to reduce the overall cost of materials, welding, and shaping for a cylindrical vessel. Four design factors are involved in this optimization task: thickness of the shell \({T}_{s}\left({x}_{1}\right)\), length of the cylindrical segment \(L\left({x}_{4}\right)\), inner radius \(R\left({x}_{3}\right)\), and head thickness \({T}_{h}\left({x}_{2}\right)\). \({T}_{h}\) and \({T}_{s}\) are distinct multiples of 0.0625 inches in thickness. The issue is stated as follows:

subject to the constraints:

with variable ranges:

Pressure vessel: (a) schematic diagram, (b) stress distribution heatmap, (c) displacement distribution heatmap39.

This issue was investigated using the HWGEA algorithm, which balances exploration and exploitation using its adaptive mutation operator. State-of-the-art algorithms such as the GBO, PDO, RSA, GOA, GSA, GA, SHADE, and LSHADE-SPACMA were all outperformed by HWGEA, which achieved a minimum cost of 5885.32. Table 6, which shows the minimum, average, maximum, and standard deviation of the costs across 30 different runs, demonstrates the greater adaptability and efficiency of HWGEA. Table 7 reports distributional statistics over 30 independent runs for the pressure-vessel design (lower cost is better). HWGEA attains the best performance across all summary metrics—lowest minimum (5886.96), lowest mean (5967.83), lowest maximum (6121.45), and the smallest dispersion (Std = 84.72)—indicating both accuracy and stability. Relative to the strongest metaheuristic baselines, HWGEA reduces the mean cost by ≈2.3% vs. SHADE (6105.48) and ≈2.8% vs. LSHADE-SPACMA (6140.27); the gains are larger against GA (≈7.5%) and GSA (≈33.8%). Its worst-case cost is also lower (e.g., ≈2.5% below SHADE’s maximum), underscoring more reliable convergence across runs.

The convergence behavior of nine meta-heuristic algorithms (HWGEA, GOA, RSA, PDO, GBO, LSHADE-SPACMA, SHADE, GA, and GSA) for Influence Maximization maximization with seed set sizes k = 10 and k = 50 on four real-world networks (Email-Eu-Core, CA-HepTh, Facebook, and Wiki-Vote) is depicted in Fig. 5. Influence Maximization (σ) is shown against iterations in each subfigure, demonstrating HWGEA’s superior stability and speed of convergence. Its hybrid weed-inspired exploration and gravitational exploitation allowed it to achieve the maximum Influence Maximization. Compared to competitors like GSA and GA, which show delayed stabilization, HWGEA is better able to avoid premature convergence thanks to the adaptive mutation operator. Additionally, a bar graph comparing the computational efficiency of nine algorithms on the Facebook, Wiki-Vote, CA-HepTh, and Email-Eu-Core networks with k = 50 is displayed in Fig. 6. Given that HWGEA’s straightforward reproduction method reduces computational overhead, the running time (in seconds) identifies HWGEA and LSHADE-SPACMA as the most effective algorithms. While GA and GSA display higher times because of intricate genetic operations and gravitational computations, respectively, gravitational dynamics minimizes needless exploration.

Welded beam design

As shown in Fig. 7, the welded beam design problem aims to satisfy limitations on shear stress, bending stress, buckling load, and deflection while minimizing fabrication costs35. Weld height \(h\left({x}_{1}\right)\), weld length \(l\left({x}_{2}\right)\), beam width \(t\left({x}_{3}\right)\), and beam thickness \(b\left({x}_{4}\right)\) are the four variables that are involved in the problem35,36. The formulation of the objective function is as follows:

with the goal:

Welded beam design: (a) schematic diagram, (b) stress distribution heatmap, (c) displacement distribution heatmap39.

That

and variable ranges:

This limited optimization problem was tackled by the HWGEA algorithm, which navigated the intricate search space using its adaptive mutation operator. The state-of-the-art techniques, such as the GBO, PDO, RSA, GOA, GSA, GA, SHADE, and LSHADE-SPACMA, were all surpassed by HWGEA, which obtained an optimal cost of 1.6923. The ideal values of the variables are reported in Table 8, and the robustness and stability of HWGEA are demonstrated by Table 9, which displays the minimum, mean, maximum, and standard deviation of the costs over 30 independent runs.

The influence (σ) dispersion of nine algorithms on the Wiki-Vote network at various seed set sizes (k = 10 to 50) is displayed in Fig. 8. By choosing the best seed nodes through adaptive mutation and gravity-guided search, HWGEA continuously attains the largest dispersion. Because of the plot’s nearly linear increase in dispersion with k, HWGEA performs better than GOA and RSA, which are hampered by local optima. Next, using dual y-axes for diffusion of influence (σ) and runtime, Fig. 9 examines how sensitive HWGEA is to four important parameters on the Wiki-Vote network (k = 50): population size, crossover rate, mutation rate, and weighting factor. Stable execution periods (~ 13 s) and optimal expansions (~ 350) are produced by moderate parameter values (population size = 150, crossover rate = 0.7), demonstrating HWGEA’s excellent balance between exploration and exploitation.

Minimizing the weight of one

As shown in Fig. 10, the goal of the tension/compression spring design challenge is to reduce a spring’s weight while meeting requirements for deflection, shear stress, surge frequency, and outer diameter. The number of active coils \(N\left({x}_{3}\right)\), mean coil diameter \(D\left({x}_{2}\right)\), and wire diameter \(d\left({x}_{1}\right)\) are the design factors35,36. The formulation of the objective function is as follows:

with variable ranges:

Minimization of weight one: (a) schematic, (b) heat map of stress (c) heat map of displacement39.

This limited optimization problem was tackled by the HWGEA algorithm, which effectively navigated the search space by utilizing its adaptive mutation operator. State-of-the-art techniques such as the GBO, PDO, RSA, GOA, GSA, GA, SHADE, and LSHADE-SPACMA were all outperformed by HWGEA, which obtained an optimal weight of 0.012664. Table 11 shows the minimum, mean, maximum, and standard deviation of the weights over 30 independent runs, demonstrating the superior consistency and low volatility of HWGEA in comparison to the alternatives. Table 10 compares the optimal values of the variables.

Figure 11 illustrates the diffusion spread (σ) against a normalized key parameter range and compares the parameter sensitivity of the nine algorithms in Wiki-Vote (k = 50). Because of their adaptive processes, HWGEA and LSHADE-SPACMA exhibit great performance, sustaining a high dispersion (~ 350) during parameter fluctuations. At extreme values, the dispersion is much decreased and GSA exhibits greater sensitivity. The robustness of the nine techniques in Wiki-Vote (k = 50) under different network densities (edge removal probability 0–0.4) is also assessed in Fig. 12. HWGEA is able to adjust to structural changes because to its dynamic neighborhood search and retains the largest diffusion spread (~ 310 at 0.4). Steeper drops are seen by rivals like GA and GSA, suggesting less flexibility.

DHWGEA algorithm to maximize penetration expansion

Finding a subset of initial seed nodes in a complex network that maximizes the overall information spread or infiltration is the goal of the Infiltration Spread Maximization (ISM) problem. Several evolutionary and metaheuristic techniques have been used to study ISM as a discrete hybrid optimization challenge1,2. This section introduces the DHWGEA algorithm, a novel modification of the HWGEA algorithm created especially to deal with the discontinuous nature of ISM in intricate networks.

DHWGEA effectively explores the discrete solution space represented by network graphs by utilizing a dynamic, neighborhood-based local search method, whereas HWGEA is best suited for continuous optimization issues. Each potential solution in this situation is equivalent to a group of seed nodes. This algorithm’s weed-inspired part makes it easier to generate a variety of candidate solutions by using adaptive seed dispersion, which is represented by the fitness-dependent standard deviation, or \(\sigma t\).

Gravity search dynamics are used to direct candidate solutions toward areas of the network with the greatest influence. These dynamics mimic how nodes are drawn to one another according on their connectivity and centrality characteristics. The following formula is used to determine the gravitational force applied on a candidate solution i at time t:

where \({F}_{i}\left(t\right)\) is the total gravitational force acting on node iii, \(G\left(t\right)\) is a time-dependent gravitational constant, \({I}_{j}\left(t\right)\) denotes the influence score of node j, \({d}_{ji}\left(t\right)\) represents the shortest path distance between nodes i and j,\(\varepsilon\) is a small positive constant introduced to prevent division by zero, and \({S}_{j}\left(t\right)\) and \({S}_{i}\left(t\right)\) are solution vectors corresponding to the seed selections of nodes j and i, respectively.

DHWGEA: proposed algorithm

By utilizing network architecture and incorporating adaptive evolutionary mechanisms, the DHWGEA method is designed to maximize penetration expansion in complex networks. The computational complexity of the penetration expansion maximization (ISM) problem is successfully addressed by DHWGEA, which employs an adaptive mutation operator to initialize and evolve the solution based on node centrality in conjunction with a dynamic neighborhood-based local search that speeds up convergence.

Problem representation

A vector \({X}_{i}=({X}_{i1}, {X}_{i2},\dots ,{X}_{ik})\), represents each solution in DHWGEA, where (k) is the number of seed nodes and each \({X}_{ij}\) indicates a node in the graph G(V, E). For instance, nodes \(\left({N}_{1}, {N}_{3}, {N}_{5}, {N}_{7}, {N}_{9}\right)\) are chosen as seeds to start influence propagation if \({X}_{i} = ({N}_{1}, {N}_{3}, {N}_{5}, {N}_{7}, {N}_{9}) with k=5\). By guaranteeing compatibility with discrete network structures, this format makes it possible to explore high-influence node sets effectively.

Objective function

The ISM problem, which is NP-hard and requires effective assessment, entails choosing a seed set (S) that optimizes Influence Maximization1. For the Independent Cascade (IC) model, traditional Monte Carlo simulations are computationally costly and may call for thousands of repetitions. We use the EIS, a proxy function, to handle this. It is defined as follows:

where \({p}_{uv}\) is the propagation probability from node u to v (set to a constant p in the IC model), and \({N}_{S}^{(1)}\) is the collection of first-degree neighbors of S. EIS provides a computationally efficient substitute for simulations by estimating the expected number of impacted nodes2. To find the best seed sets, DHWGEA employs EIS to assess solution fitness.

Initial population

Each of the N solutions that make up the initial population has k nodes. DHWGEA chooses the top k nodes according to their degree centrality as the foundation for every solution in order to guarantee quality and variety. A subset of these nodes is randomly swapped out for other nodes in the graph to add variability. This is managed using an adaptive mutation operator that modifies the replacement probability according to population diversity, which is computed as follows:

where \(MaxVar\) is a normalization constant and \(var (Fitness \left(t\right))\) is the variance of population fitness at iteration (t).

Mitigating centrality bias

The propensity of degree-based initialization to give priority to hubs is a drawback. In order to combat this, DHWGEA uses two methods: (i) adaptive mutation, which adds non-hub candidates to the initial pool, and (ii) dynamic neighborhood refinement, which actively searches neighboring nodes with a high marginal gain in Influence Maximization and frequently finds structurally important bridge nodes. DHWGEA outperforms simply degree-driven heuristics in identifying seed sets that extend beyond hubs, attaining impact spreads that are near to CELF, according to empirical results in sparse and diverse datasets (e.g., Netscience, Ca-GrQc).

Evaluation of DHWGEA for influence maximization maximization

Finding a seed set S with k nodes in a network \(G\left(V,E\right)\) where \(\mid V\mid =n and \left|E\right|= m\) so that the predicted Influence Maximization \(\upsigma \left(\text{S}\right)\) is maximized is the goal of the Influence Maximization Maximization (ISM) issue. Formally, the optimization objective is defined as follows, given an integer k < n:

Effective algorithmic techniques are needed to select high-impact initial nodes in this NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem11. The proposed algorithm solves the ISM problem in complex networks using a dynamic neighborhood-based local search mechanism and an adaptive mutation operator. Real-world datasets were used to empirically evaluate the effectiveness of the algorithm.

All experiments were performed using MATLAB R2023a and a Windows 11 operating system on a personal computer with an Intel Core i7 processor running at 3.15 GHz. Four real-world networks Netscience, email, Ca-GrQc, and Ca-HepTh that represent scientific communication and collaboration systems were used48. Table 12 provides a summary of the topological properties of this dataset, such as the number of nodes ∣V∣, the number of edges |E|, the average degree k, the clustering coefficient C, and the classification coefficient AC.

GBO, PDO, RSA, GOA, GSA8, GA, and both SHADE and LSHADE-SPACMA10 were the eight cutting-edge meta-heuristic algorithms that DHWGEA was evaluated against in order to determine its efficacy. The following modifications were made to each algorithm for the ISM task:

-

Gradient-based optimizer (GBO): Applying a discrete mapping mechanism, iteratively chooses high-degree nodes using gradient-inspired update rules48.

-

Prairie dog optimization (PDO): Uses local search improvements and concentrates on nodes with high centrality to mimic the foraging habits of prairie dogs40.

-

Reptile search algorithm (RSA): Uses reptile hunting techniques to prioritize important nodes and investigate the network topology47.

-

Gazelle optimization algorithm (GOA): Balances exploration and exploitation in node selection by implementing dynamics inspired by gazelle movement48.

-

Gravitational search algorithm (GSA): Uses node impact scores to model gravitational attraction in order to guide the selection of seed nodes45.

-

Genetic algorithm (GA): Under network diffusion constraints, seed sets are evolved via the standard evolutionary processes of crossover and mutation46.

-

SHADE and LSHADE-SPACMA: Effectively identify influential nodes by utilizing parameter adaption based on historical success37,39.

A critique of the excessive use of metaphors in metaheuristics is presented and the need to focus on scientific principles for designing optimization algorithms is emphasized. The Independent Cascade (IC) model with 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations was used to calculate the evaluation metric, Influence Maximization \(\sigma \left(S\right)\). Except for the nodes in the seed set S, all nodes are initially inactive in the IC model.

Comparison of penetration rate

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid discrete weed-gravity evolution algorithm (DHWGEA) for maximizing the penetration rate, the penetration rate is compared with eight meta-heuristic algorithms GOA, RSA, PDO, GBO, LSHADE-SPACMA, SHADE, GA, GSA and the Greedy Lazy Forward Cost-Effective (CELF) algorithm. Experiments were conducted on four real-world networks—Netscience, Email, Ca-GrQc and Ca-HepTh—using the independent cascade (IC) model with propagation probabilities \(p = 0.01 and p = 0.05\). The penetration spread \(\upsigma \left(\text{S}\right)\) was estimated through 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, with seed set sizes \(\text{Smax}=5\) for Netscience, Email and Ca-GrQc and \(\text{Smax}=20\) for Ca-HepTh. The DHWGEA parameters were set with an initial population of 100, maximum iterations of 250 and adaptive mutation probability \({p}_{m}= 0.3\), which strikes a balance between exploration and exploitation. Figure 13 shows the average penetration spread from 30 independent runs, which shows the competitive performance of DHWGEA on all networks. Figure 13 contains eight subfigures (a–h), each showing the penetration expansion of nine algorithms in a network for specific seed set sizes \(\text{k}=\text{5,10,15,20}\) under \(p = 0.01\) (subfigures a–d) and \(p = 0.05\) (subfigures e–h). DHWGEA consistently ranks second to CELF, achieving penetration expansions close to the greedy approach \((e.g., \sigma \approx 450 on Ca-HepTh at k=20, p=0.05)\) but with significantly lower computational cost. Neighborhood-based dynamic local search and gravitational dynamics enable DHWGEA to select high-impact initial nodes and outperform metaheuristic algorithms such as DPSO, GOA, and PSO-based GSA that struggle with local optimization. For smaller networks such as Netscience \(\left(\text{k }= 5, \text{p}=0.01\right)\), the dispersion of DHWGEA \(\left(\sigma \approx 150\right)\) approaches that of CELF, highlighting its efficiency in sparse topologies. In contrast, algorithms such as GA and GSA exhibit lower dispersion due to slower convergence and sensitivity to network structure.

Influence Maximization of nine methods for seed set sizes (k = 5, 10, 15, 20) on the networks of Netscience, Email, Ca-GrQc, and Ca-HepTh in comparison to CELF. Results for propagation probability (p = 0.01) and p = 0.05 are displayed in subfigures (a–d) and (e–h), respectively, averaged over 30 runs using 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations in the Independent Cascade model. With a lower computational cost and near-optimal spreads, DHWGEA comes in second behind CELF.

As shown in Fig. 13, CELF consistently achieves the highest spread due to its greedy submodular guarantee. However, this comes at the expense of significantly higher runtime (see Fig. 14). DHWGEA achieves spreads close to CELF while remaining much more efficient, making it a more practical choice in large-scale networks.

Comparing execution times

Figure 14 illustrates a bar graph that compares the execution durations of DHWGEA, eight meta-heuristic algorithms (GOA, RSA, PDO, GBO, LSHADE-SPACMA, SHADE, GA, GSA), CELF, and PageRank across the Netscience, Email, Ca-GrQc, and Ca-HepTh networks under the IC model with propagation probabilities \(p=0.01\) and \(p=0.05\), averaged over 30 iterations with 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations. DHWGEA exhibits superior efficiency, with execution times of approximately 13 to 15 s on Ca-HepTh (k = 20), markedly lower than CELF, which takes around 50 s and entails substantial computational expense due to its greedy selection approach. PageRank attains the quickest execution times (approximately 5 s) but compromises on influence dissemination, whereas DHWGEA strikes a balance between speed and efficacy, surpassing DPSO and GSA (approximately 20–25 s) by utilizing its dynamic neighborhood-based local search and adaptive mutation, rendering it appropriate for extensive influence maximization.

Figure 14 highlights that PageRank achieves the lowest runtime but at the cost of much weaker Influence Maximization (see Fig. 13). DHWGEA is slower than PageRank but substantially faster than CELF, while maintaining far higher spread than PageRank.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

We performed a thorough parameter sensitivity analysis and looked at how changes to important parameters impact the algorithm’s performance in order to assess the resilience of the HWGEA algorithm and its discrete counterpart, DHWGEA. Particularly for intricate network optimization and penetration expansion maximization objectives, this study guarantees that HWGEA and DHWGEA retain their efficacy in a variety of contexts1.

Sensitivity analysis for HWGEA

We examined four important factors for HWGEA: adaptive mutation rate \({P}_{mut}\), maximum offspring count \({S}_{max}\), final standard deviation \({\sigma }_{final}\), and starting standard deviation \({\sigma }_{initial}\). A variety of values was used to test each parameter:

With 30 independent runs per setting, experiments were carried out on the benchmark functions F1 (unimodal), F9 (multimodal), and F23 (composite). Std, mean solution accuracy (Avg), and convergence speed (the number of iterations needed to reach 90% of the ideal value) were among the performance indicators. The results for F9 are summarized in Table 13, which demonstrates that \({S}_{max}=8\), \({P}_{mut}=0.1\), \({\sigma }_{final}=0.005\), and \({\sigma }_{initial}=0.5\) produce optimal performance by successfully balancing exploration and exploitation. While a lower \({S}_{max}\) (e.g., 5) led to slower convergence, a larger \({\sigma }_{initial}\) value (e.g., 2.0) raised Std, indicating instability in solution quality. In response to population variety, the adaptive mutation operator dynamically modified \({P}_{mut}\) to reduce sensitivity effects12.

Sensitivity analysis for DHWGEA

We investigated the number of seed nodes \(k\), adaptive mutation probability \({P}_{mut}\), and discrete mutation threshold \({\sigma }_{t}\) on the email and Ca-HepTh networks for DHWGEA:

Influence Maximization \(\sigma S\) and computing time were used to quantify performance using 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations in the Independent Cascade model with \(p=0.1\). Table 14 shows that \({\sigma }_{t}=0.3\), \({P}_{mut}=0.1\), and k = 20 maximize \(\sigma S\) while preserving a respectable level of computing efficiency. While bigger k (e.g., 50) increased computing expense without equal gains, higher \({\sigma }_{t}\) (e.g., 0.7) led to excessive investigation, limiting Influence Maximization. Performance was stable in all settings because to the dynamic neighborhood-based local search.

Comparison with CELF

Because of its greedy selection method and assured submodularity bounds, CELF delivers the biggest absolute Influence Maximization; however, this benefit comes at a somewhat greater computational cost. The repetitive marginal gain evaluations needed for CELF do not scale well as the network size and seed set increase. On the other hand, as Figs. 13 and 14 show, DHWGEA provides a more balanced trade-off by running at a quarter of the runtime and delivering near-CELF spreads (within a 2–5% difference on Ca-HepTh).

Table 15 presents a direct comparison between CELF and DHWGEA over four real-world networks in order to more clearly illustrate this trade-off. According to the results, DHWGEA obtains competitive values with significantly less runtime, even if CELF regularly achieves the greatest spreads. On the Ca-HepTh network with k = 20, for instance, CELF takes around 50 s to reach a spread of about 940, while DHWGEA takes only about 15 s to reach a spread of about 895. Because of its efficiency, DHWGEA is especially well-suited for time-sensitive or large-scale applications when the computational cost of CELF is unaffordable.

Our comparison shows that DHWGEA does not dominate all baselines at once: PageRank obtains the fastest runtime, while CELF produces the best absolute spread. By offering near-CELF spreads at significantly lower runtime and significantly bigger spreads than PageRank at moderate runtime, DHWGEA offers a well-balanced compromise. Our efficiency claim is made clearer by this balance: DHWGEA is the most feasible trade-off for medium-to-large networks where PageRank is insufficient in influence quality and CELF is computationally prohibitive, rather than the best in a single dimension.

Multi-objective perspective

Although maximizing Influence Maximization is the main emphasis of this study, real-world influence maximization frequently entails a number of goals, including balancing spread with computational cost, community justice, and latency restrictions.

The comparative trade-off analysis reveals the complementary advantages and disadvantages of CELF, PageRank, and DHWGEA across a number of objectives, as shown in Fig. 15 and Table 16. Because of its greedy submodular assurances, CELF has the greatest impact spread; however, this comes at the cost of increased computing cost and less equitable treatment across community boundaries. In comparison, PageRank has the lowest latency and higher cost-efficiency; nevertheless, its spread and fairness are significantly poorer, which makes it less appropriate for maximizing influence in heterogeneous networks. By preserving near-CELF impact spread, enhancing cost-effectiveness and fairness, and attaining moderate latency, DHWGEA offers a well-balanced solution. This balance implies that, although DHWGEA does not strictly dominate either CELF or PageRank, it offers a practical middle ground particularly applicable to large-scale or fairness-sensitive applications where single-objective optimization may be insufficient.

Conclusion

Strong metaheuristic frameworks for continuous and discrete optimization are offered by the HWGEA algorithm and its discrete counterpart, DHWGEA. With the help of an adaptive mutation operator, HWGEA successfully strikes a balance between exploration and exploitation by fusing adaptive weed-inspired seed dispersal with gravity search dynamics. HWGEA achieves superior Friedman ranks across unimodal, multimodal, and composite functions and beats state-of-the-art algorithms such as PSO, GA, GSA, SHADE, and LSHADE-SPACMA when tested on 23 benchmark functions. HWGEA outperforms GBO, PDO, and RSA in engineering applications by offering better solutions for pressure tank design, welded beam design, and weight reduction. Topology-aware initialization and dynamic neighborhood-based local search are used by DHWGEA to choose high-impact beginning nodes in order to optimize influence propagation. DHWGEA performs better than DPSO and GSA by up to 15% in spreading and 40% in speed in real-world networks (Netscience, Email, Ca-GrQc, and Ca-HepTh) but trails CELF in Influence Maximizationing.

Notwithstanding these advantages, DHWGEA’s dependence on degree centrality raises the possibility of bias in sparse graphs, and the computational complexity of HWGEA may make it difficult to scale in very large networks. Despite being adaptive, parameter adjustment necessitates empirical optimization, which may restrict its applicability. Deep reinforcement learning will be investigated in future research to dynamically adjust parameters, enhancing robustness and scalability. While merging DHWGEA with graph neural networks may enhance node selection in dynamic networks, multi-objective extensions of HWGEA can balance the distribution of influences and computational cost. Moreover, both techniques’ usefulness is increased by validating them on a variety of datasets, such as temporal and multilayer networks.

Data availability

All data required to reproduce the findings are openly available. The network datasets used for influence-maximization experiments (Netscience, Email-Eu-Core, Ca-GrQc, and Ca-HepTh) are public releases from the Stanford Large Network Dataset Collection (SNAP). The exact snapshots employed, together with preprocessing scripts (undirected conversion, largest-component filtering, metadata) and the figure/table-ready CSV outputs generated in this study, are archived on Zenodo under https://zenodo.org/records/17,171,755. Continuous benchmark functions and the engineering design problems (pressure vessel, welded beam, spring) are standard synthetic formulations; no proprietary data were used. Any additional materials not included in the Zenodo archive are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jalili, M. & Perc, M. Information cascades in complex networks. J. Complex Netw. 5(5), 665–693 (2017).

Berahmand, K., Nasiri, E., Forouzandeh, S. & Li, Y. A preference random walk algorithm for link prediction through mutual influence nodes in complex networks. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inform. Sci. 34(8), 5375–5387 (2022).

Motevalli, H. et al. Applying meta-heuristic dynamic algorithms to maximize impact and discover significant nodes in social networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 15(1), 27 (2025).

Meng, B. & Rezaeipanah, A. Development of a multidimensional centrality metric for ranking nodes in complex networks. Chaos, Solit. Fract. 191, 115843 (2025).

Yang, X. & Xiao, F. An improved gravity model to identify influential nodes in complex networks based on k-shell method. Knowl.-Based Syst. 227, 107198 (2021).

Zhang, K., Pu, Z., Jin, C., Zhou, Y. & Wang, Z. A novel semi-local centrality to identify influential nodes in complex networks by integrating multidimensional factors. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 145, 110177 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks via Transformer. Inf. Process. Manage. 61(5), 103775 (2024).

Gu, Z., Yan, S., Ahn, C. K., Yue, D. & Xie, X. Event-triggered dissipative tracking control of networked control systems with distributed communication delay. IEEE Syst. J. 16(2), 3320–3330. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2021.3079460 (2022).

Han-huai, P., Lin-wei, W., Hao, L. & Abdollahi, M. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks: a semi-local centrality measure based on augmented graph and average shortest path theory. Telecommun. Syst. 88(1), 25 (2025).

Jiang, J., Liu, Y. & Zhao, Z. TriTSA: Triple Tree-Seed Algorithm for dimensional continuous optimization and constrained engineering problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 104, 104303 (2021).

Chen, D. & Su, H. Identification of influential nodes in complex networks with degree and average neighbor degree. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Circuit. Syst. 13(3), 734–742 (2023).

Ishfaq, U., Khan, H. U. & Iqbal, S. Identifying the influential nodes in complex social networks using centrality-based approach. J. King Saud Univ. –Comput. Inform. Sci. 34(10), 9376–9392 (2022).

Dong, J., Jiang, H. & Cao, Z. Maximizing penetration in complex networks via the discretization of a new continuous meta-heuristic algorithm. Clust. Comput. 28(5), 1–29 (2025).

Zhang, R., Wang, X. & Pei, S. Targeted influence maximization in complex networks. Physica D 446, 133677 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Tianji’s horse racing optimization (THRO): a new metaheuristic inspired by ancient wisdom and its engineering optimization applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58(9), 282 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Artificial Protozoa Optimizer (APO): a novel bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for engineering optimization. Knowl.-Based Syst. 295, 111737 (2024).

Zhong, R., Hussien, A. G., Houssein, E. H., & Yu, J. (2025). Enhanced Crested Ibis Algorithm: Performance Validation in Benchmark Functions, Engineering Problem, and Application in Brain Tumor Detection. Expert Syst. Appl., 128231.

Yusupov, J., Palakonda, V., Mallipeddi, R., & Veluvolu, K. C. (2021, January). Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Ensemble of Initializations for Overlapping Community Detection. In 2021 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC) (pp. 1–7). IEEE.

Liang, Z., He, Q., Du, H. & Xu, W. Targeted influence maximization in competitive social networks. Inf. Sci. 619, 390–405 (2023).

Panagopoulos, G., Tziortziotis, N., Vazirgiannis, M., & Malliaros, F. (2023, November). Maximizing influence with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (237–244).

Zhao, J., Wang, Y. & Deng, Y. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks from global perspective. Chaos, Solit. Fract. 133, 109637 (2020).

Mashwani, W. K., Salhi, A., Yeniay, O., Hussian, H. & Jan, M. A. Hybrid non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm with adaptive operators selection. Appl. Soft Comput. 56, 1–18 (2017).

Wu, Y., Niu, B., Li, L., Zhao, X. & Alotaibi, N. D. Switching event-triggered adaptive finite-time control for nonlinear networked systems. Asian J. Control. https://doi.org/10.1002/asjc.3859 (2025).

Mashwani, W. K., Shah, H., Kaur, M., Bakar, M. A. & Miftahuddin, M. Large-scale bound constrained optimization based on hybrid teaching learning optimization algorithm. Alex. Eng. J. 60(6), 6013–6033 (2021).

Chen, T., Yan, S., Guo, J. & Wu, W. ToupleGDD: a fine-designed solution of influence maximization by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 11(2), 2210–2221 (2023).

Kumar, S., Mallik, A. & Panda, B. S. Influence maximization in social networks using transfer learning via graph-based LSTM. Expert Syst. Appl. 212, 118770 (2023).

Li, H. et al. GRASS: learning spatial-temporal properties from chainlike cascade data for microscopic diffusion prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35(11), 16313–16327. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3293689 (2024).

Deng, Q., Chen, X., Lu, P., Du, Y., & Li, X. Intervening in Negative Emotion Contagion on Social Networks Using Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSS.2025.3555607 (2025)

Peng, Y., Zhao, Y., Dong, J. & Hu, J. Adaptive opinion dynamics over community networks when agents cannot express opinions freely. Neurocomputing 618, 129123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129123 (2025).

Fu, C., Liu, G., Yuan, K. & Wu, J. Nowhere to H2IDE: fraud detection from multi-relation graphs via disentangled homophily and heterophily identification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 37(3), 1380–1393. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2024.3523107 (2025).

Nandi, S., Curado Malta, M., Maji, G. & Dutta, A. IC-SNI: measuring nodes’ influential capability in complex networks through structural and neighboring information. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 67(2), 1309–1350 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. A novel event-triggered mechanism-based optimal safe control for nonlinear multi-player systems using adaptive dynamic programming. J. Franklin Inst. 362(11), 107761 (2025).

Hao, Xu., Zhao, N., Ning, Xu., Niu, B. & Zhao, X. Reinforcement learning-based dynamic event-triggered prescribed performance control for nonlinear systems with input delay. Int. J. Syst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207721.2025.2557528 (2025).

Zhang, S. S., Xie, M., Liu, C., & Zhan, X. X. (2025). Influence maximization in multilayer networks based on adaptive coupling degree. Chaos: Interdisciplinary J. Nonlin. Sci., 35(3).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61 (2014).

Rabie, R. M., Hegazy Zaher, N. R. S. & Sayed, H. A modified Harris hawks algorithm to solving optimization problems. Int. J. Indust. Eng. 35(1), 1–14 (2024).

Viktorin, A., Senkerik, R., Pluhacek, M., & Kadavy, T. SHADE Algorithm Dynamic Analyzed Through Complex Network. In International Computing and Combinatorics Conference 666–677. (Cham: Springer International Publishing 2017).

Daoud, M. S. et al. Gradient-based optimizer (GBO): a review, theory, variants, and applications. Archiv. Comput. Methods Eng. 30(4), 2431–2449 (2023).

Refaat, M. M., Aleem, S. H. A., Atia, Y., Ali, Z. M. & Sayed, M. M. Multi-stage dynamic transmission network expansion planning using lshade-spacma. Appl. Sci. 11(5), 2155 (2021).

Ezugwu, A. E., Agushaka, J. O., Abualigah, L., Mirjalili, S. & Gandomi, A. H. Prairie dog optimization algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 34(22), 20017–20065 (2022).

Mashwani, W. K., Salhi, A., Yeniay, O., Jan, M. A. & Khanum, R. A. Hybrid adaptive evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. Appl. Soft Comput. 57, 363–378 (2017).

Zhang, M., Wang, X., Jin, L., Song, M. & Li, Z. A new approach for evaluating node importance in complex networks via deep learning methods. Neurocomputing 497, 13–27 (2022).

Lotf, J. J., Azgomi, M. A. & Dishabi, M. R. E. An improved influence maximization method for social networks based on genetic algorithm. Physica A 586, 126480 (2022).

Mashwani, W. K., Shah, S. N. A., Belhaouari, S. B. & Hamdi, A. Ameliorated ensemble strategy-based evolutionary algorithm with dynamic resources allocations. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 14(1), 412–437 (2021).

Rashedi, E., Nezamabadi-Pour, H. & Saryazdi, S. GSA: a gravitational search algorithm. Inf. Sci. 179(13), 2232–2248 (2009).

Li, Z. & Liu, J. A multi-agent genetic algorithm for community detection in complex networks. Physica A 449, 336–347 (2016).

Sasmal, B., Hussien, A. G., Das, A., Dhal, K. G. & Saha, R. Reptile search algorithm: theory, variants, applications, and performance evaluation. Arch. Comput. Method Eng. 31(1), 521–549 (2024).

Agushaka, J. O., Ezugwu, A. E. & Abualigah, L. Gazelle optimization algorithm: a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic optimizer. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(5), 4099–4131 (2023).

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conception and design of the study were jointly developed by all authors. Linian Liu, Junyi Xu, Shouliang Lai, and Mohammad Trik were responsible for data collection, simulation, and analytical processes. All contributors played an active role in refining the research and ensuring its methodological rigor.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Xu, J., Lai, S. et al. A hybrid evolutionary algorithm for influence maximization in complex networks using invasive weed optimization and gravitational search. Sci Rep 15, 39528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23170-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23170-0