Abstract

There are close to 100 million combustible tobacco users in India. This study was conducted to assess the national and state-level estimates for smoking quit ratio and identify the factors associated with quitting smoking among life-time combustible tobacco users aged 45 years and above in India. A cross-sectional analysis of a representative sample of 11,920 lifetime combustible tobacco users aged ≥ 45 years extracted from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) was conducted. Quit ratio was defined as the ratio of individuals who quit smoking to lifetime combustible tobacco users. Descriptive estimates for quit ratios at the national and state levels were computed. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) using binary logistic regression analysis were computed to identify the factors associated with quitting smoking. The smoking quit ratio at the country level was estimated as 21.1%. Among major states, Kerala (49.0%, 95% CI = 48.9–49.1) had the highest quit ratio. Individuals aged 61 years and above (AOR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.46–2.03), healthcare visits (AOR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.09–1.53), diagnosis with non-communicable diseases like cancer, lung disease, heart disease or stroke (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.52–2.30) had significantly higher odds of successfully quitting smoking. Individuals consuming alcohol at least once a month (AOR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.42–0.71) had lower odds of quitting smoking compared to their counterparts. The less-than-optimal quit ratios at national and state levels among lifetime combustible tobacco users in India are reflective of the bottlenecks in tobacco cessation support availability, access, and use. A higher quit ratio was observed in states that invested in strengthening tobacco control systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, over a billion individuals smoke tobacco products, and eight million die annually due to reasons attributable to smoking1. Quitting smoking is known to have immediate and long-term health benefits to individuals, save costs, and add to overall economic productivity2. Smoking cessation has long been a global health priority, and the 2019 World Health Organization’s (WHO) report on the global tobacco epidemic emphasizes promoting smoking cessation as integral for achieving tobacco control targets3. India accounts for around 10% of the global smoking burden with an estimated 100 million adults smoking combustible tobacco products. Annually, more than one million Indians die due to smoking and associated causes. In recent decades, India witnessed a substantial drop in the number of tobacco users, with the smoking prevalence among adults decreasing from 14.0 to 10.7%4. Indicators like awareness about the health effects of smoking and availability of the WHO-recommended approaches to quit smoking are on par with the developed economies5, however, the smoking quit behaviors are not optimal. Nations like the United Kingdom and the United States reported over a 45% prevalence of 12-month quit attempts among combustible tobacco users6, while the same was around 38% in India7. The 2016–17 Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) reported that less than 15% of the combustible tobacco users who attempted quitting used cessation services like counselling, nicotine replacement therapy, and prescription medicines8, whereas in the United States, the cessation service use during the same period was over 30%9,10. India also had the lowest smoking quit rates, with estimates indicating that only 14.2% of life-time combustible tobacco users were able to successfully quit smoking11.

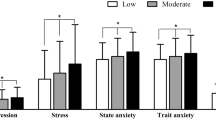

Quitting smoking is defined as stopping the use of combustible tobacco products (such as bidi, cigarette, cigars, etc.) and continual abstinence without a relapse for an extended period of time. Research based on large-scale surveys defined successful quitting as smoking abstinence for at least 12 months12. Further, staying quit for 12 months is considered as long-term abstinence and a better indicator for successful quitting, particularly in studies measuring point prevalence13,14. Quit ratio is defined as the proportion of former users to people who are life-time combustible tobacco users and serves as an indicator for the long-term effectiveness of tobacco control programmes5. The smoking quit rates are influenced by an individual’s socio-demographic profile, health behaviors, health status, and healthcare use15,16. Geographical differentials in smoking quit rates within India were observed, with the states in the southern region reporting double the quit rates than the states in the northern region17. Among the individuals who smoke, it was found that those in younger age groups had a higher prevalence of quit attempts, but those over 45 years are more likely to quit compared to their younger counterparts15,16. Also, the demographic characteristics like education, wealth index, and place of residence were found to be associated with cessation behavior among tobacco users in India16. Higher quit rates were reported among individuals with poor health status, chronic disease diagnosis, and access to a healthcare provider9. While health behaviors such as alcohol use, smokeless tobacco use, were associated with continual of smoking, participation in positive health behaviors like yoga and meditation were associated with abstinence from smoking (see Fig. 1)18,19,20.

From GATS 2009–10 to GATS 2016–17, despite India scoring highly across the tobacco control indicators, smoking quit rates improved only marginally from 12.1 to 14.2% of the ever users11,16. Moreover, the available evidence on quit rates is confined to region specific studies, studies among healthcare providers, and randomized controlled trials evaluating effectiveness of smoking cessation strategies21,22,23. Nationally representative evidence on smoking quit ratio that can inform public policy is limited. Further, there is a wide variation amongst the Indian states with respect to the demographic distribution, disease profile, tobacco use, availability of tobacco cessation support, and the preparedness of the healthcare system to tackle non-communicable diseases. Evidence on successful quitting among adults 45 years and above will be critical for tobacco control policy in India as more than half of those who currently smoke are from this age group7.

This study was conducted to assess the national and state-level prevalence of smoking quit ratio among life-time combustible tobacco users aged 45 years and above in India. It also seeks to identify the role of socio-demographic, behavioral, health status, and healthcare use factors in quitting smoking.

Methods

A cross-sectional analysis of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) wave 1 survey (2017–18) was conducted. The LASI survey is a collaborative effort of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and the University of Southern California24.

LASI is a nationally representative household survey conducted with an objective to study ageing, health, and health behaviors among individuals aged 45 years and above. It surveyed a total of 72,250 adults, with the sample comprising of adults aged 45 years and above and their spouses of any age. The survey employed a multi-stage stratified area probability cluster sampling design. In each state, the sampling in rural areas followed a three-stage model (sub-districts, villages, and households) and in urban areas a four-stage model (sub-districts, urban wards, census enumeration blocks, and households). From each household, all individuals 45 years and above and their spouses were sampled. The LASI survey reports and support documents provide details of survey methodology, sampling designs, questionnaire, and data quality checks24. The LASI data set used in this analysis was obtained from the IIPS through a formal request.

Based on the response to the items “ever smoked or used smokeless tobacco” and “type of tobacco product”, a sample of 12,057 life-time users of combustible tobacco products (cigarettes, bidis, cigars, cheroot) was extracted. Further, after filtering for age of the respondent, we included a sample of 11,920 individuals who are self-reported to be life-time combustible tobacco users aged 45 years and above (see Fig. 2). This study included participants sampled from all Indian states except Sikkim.

Study variables

Quitting smoking was defined as self-reported quitting and abstinence from smoking tobacco products (cigarettes, bidis, cigars, cheroot) for at least one year at the time of survey. The quit status of the respondent was derived based on two components: (i) being a person who formerly smoked, and (ii) having a period of continual abstinence for at least one year. An individual was considered to be a person who formerly smoked if he/she reported “no, I quit” to the item “currently smoke any tobacco products”. The period of abstinence was computed based on responses to the items: (i) “age of the respondent”, (ii) “age when respondent completely stop smoking”, (ii) “year when respondent quit smoking”, and (iv) “years ago respondent totally stopped smoking”. The duration of abstinence was calculated based on: (i) the difference between the age of respondent and age when respondent completely stops smoking, (ii) respondent reported year of quitting smoking during or before 2016 (considering 2017 as LASI survey year), or (iii) self-reported number of years since the respondent quit smoking.

The independent variables were identified through a review of tobacco cessation literature, the LASI survey questionnaire, and survey data. The independent variables were grouped as socio-demographic variables, behavioral factors, and health status. Socio-demographic factors included (i) age, (ii) sex, (iii) place of residence, (iv) highest education, (v) caste, and (vi) wealth index. Health behaviors included (i) alcohol consumption, (ii) smokeless tobacco consumption, (iii) involvement in yoga, meditation, asana, and pranayamas. Health status included (i) diagnosis with hypertension or diabetes, (ii) diagnosis with cancer/lung disease/heart disease/stroke, (iii) physician consultation in the last 12 months, and (iv) self-reported health status.

Participant’s self-reported age at last birthday was grouped into two categories: (i) 45–60 years, and (ii) 61 years and above. Participant’s self-reported education was categorized as (i) never attended schooling, (ii) up to primary education, (iii) middle and secondary schooling, and (iv) higher secondary and above. The self-reported alcohol consumption of at least once a month was computed based on two variables: (i) “ever consumed alcoholic beverages” and (ii) “number of times respondent had alcohol”. Diagnosis with hypertension or diabetes was developed by combining two separate variables, individually capturing the details of self-reported previous diagnoses with hypertension and diabetes, respectively. Similarly, a previous diagnosis of cancer/lung disease/heart disease/stroke was based on individual binary items capturing the self-reported diagnosis with at least one of these chronic diseases. An outline of the LASI source variables and the study variables developed is reported in the supplementary file.

Data analysis

Data cleaning and analysis were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 27 (IBM Corp., Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), and STATA version 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The data cleaning process involved the development of a dependent variable from the source variables, cleaning for missing data, and transformation of study variables according to the plan for operationalization (see supplementary file). Analysis was conducted after applying the relevant sample weights (national and state sample weights) provided with the LASI dataset.

Data was analyzed descriptively by computing prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of smoking quit ratios at the national and state levels. Bivariate comparisons of the quit ratio by individual independent variables were made. Multivariable analysis employing binary logistic regression was conducted to assess the factors associated with the quit ratio. The main effects, and interaction effects of independent variables on the quit ratio were computed. The discriminative ability of the logistic regression models was assessed employing the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were computed as a measure of association and to address confounding bias. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was computed to assess multicollinearity between the independent variables in the regression model. The average VIF of the regression model was obtained to be 1.34. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess the model fit. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

Results

The study sample were majorly males (88.8%) and rural residents (79.0%). Around a quarter (25.3%) reported being diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes, and 15.9% reported a diagnosis of cancer/ lung disease/ heart disease/stroke. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of study samples across the independent variables.

Smoking quit ratio

At the national level, around 21.1% of life-time combustible tobacco users aged 45 years and above quit smoking. The quit ratio varied by states, with the states of Kerala (49.0%, 95% CI = 48.9–49.1), Jharkhand (45.6, 95% CI = 45.4–45.7), and Bihar (36.5%, 95% CI = 36.5–36.6) leading among the major states (i.e., with at least 33 million population). Table 2 outlines the state-wise prevalence of the smoking quit ratio.

Factors associated with the quit ratio

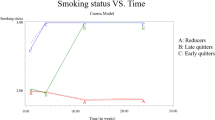

Quitting smoking varied by socio-demographic, health, and behavioral factors. Individuals aged 61 years and above (AOR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.46–2.03), education level of higher secondary and above (AOR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.69–3.31), individuals belonging to other backward classes (AOR = 1.32, 95%CI = 1.07–1.64), individuals reporting consuming smokeless tobacco (AOR = 1.94, 95%CI = 1.56–2.40), individuals involved in yoga, meditation, asana, pranayama (AOR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.06–1.66), individuals diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes (AOR = 1.50, 95%CI = 1.25–1.80) and those with an NCD diagnosis such as cancer, lung disease, heart disease or stroke (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.52–2.30) had significantly higher odds of successfully quitting smoking. Males (AOR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.57–0.97), rural residents (AOR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.62–0.92), and those consuming alcohol at least once a month (AOR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.42–0.71) had lower odds of quitting smoking (see Table 3). The logistic regression model had an acceptable model fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow test, p = 0.770), and an AUROC of 0.686, indicating a moderate discriminative ability of the model (see Fig. 3a).

Adjusting for the interaction effects, those aged 61 years and above (AOR = 2.00, 95%CI = 1.38–2.89), educated at higher secondary and above level (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.73–3.09), individuals with a diagnosis of hypertension or diabetes (AOR = 2.14, 95%CI = 1.21–3.78), and those with interaction of the independent factors of older age 61 years and above, having a physician consultation, a fair health status, and diagnosis with hypertension/diabetes/cancer/lung disease/heart disease/stroke (AOR = 4.06, 95% CI = 1.03–15.97) had significantly higher odds of quitting smoking (see Table 4). The logistic regression model had an acceptable model fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow test, p = 0.734), and an AUROC of 0.690, indicating a moderate discriminative ability of the model (see Fig. 3b).

Discussion

An estimated 21.1% of life-time combustible tobacco users aged 45 years and older in India successfully quit smoking. The quit ratio estimates in our study are higher than those reported in the studies based on GATS surveys11,16, which could be attributed to the demographic focus of the study. However, the quit ratio was comparatively less than what was observed in the high-income settings like the United States which reported quit ratios > 52%25. Smoking cessation follows a continuum with instances of intention to quit, quit attempts, and ultimately culminating with successful quitting26. Previous studies in India reported that younger adults had a higher intention to quit and attempted quit attempts compared to older individuals who smoke27,28, whereas our study presents that older individuals, specifically those over 61 years are more likely to quit smoking. Quitting smoking tend to increase with age, however quit ratio among 61 years and above is only 26.8% indicating that a substantial progress in smoking cessation is yet to be made in India29. While the overall tobacco use prevalence is high among males7, men were less likely to quit smoking. Despite females exhibiting a slightly higher quit ratio (23.4%) compared to males (21.1%), the small difference suggests that the overall clinical significance is limited.

Diagnosis with chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer, lung disease, heart disease and stroke were associated with a higher likelihood of smoking cessation, with over one-third of individuals with these diagnoses reporting that they had quit smoking. These findings suggest that many smokers in India successfully quit after receiving a diagnosis for a chronic condition8. A recent qualitative study of tobacco users and cessation providers in India reported that a chronic disease diagnosis serves as a motivator to quit tobacco use30. Older age and chronic non-communicable diseases translate into a higher frequency of health worker interactions, which could have also contributed to better quit ratios31. Concurring with the existing evidence reporting that the healthcare professional’s advice to quit servs as a motivator to quit tobacco use15,16, we found that 25.3% of individuals reporting a physician consultation in the last 12 months reporting to have quit tobacco use. The interactions among older age, physician consultation, and a diagnosis of a chronic condition showed significant impact on quitting smoking. Smoking cessation rates in India are very low, and are predominantly concentrated among older individuals or those already experiencing health issues. Younger smokers who could benefit the most from quitting32, remain to have low quit rates. Individuals in the age group of 15–44 years account for 48% of smokers in India, yet only 7.9% reported quitting in this age group16. The concentration of quitting among older groups with health issues, coupled with very low quit rates among younger demographics explain the marginal improvement of smoking quit rates from GATS-1 (2009–10) to GATS-2 (2016–17), despite a marked increase in awareness about health effects of tobacco4,11,16. While India scores high with respect to offering cessation support3,5, a large proportion of population remain unreached by current cessation initiatives. In 2014–15, over half of those visiting healthcare providers were not advised to stop smoking33. In 2016–17, fewer than 10% of tobacco users attempting to quit utilized cessation services like NRT15. Further, in 2023–24, less than 1% of tobacco users in India accessed quitline services34, underscoring the urgent need to bolster cessation programs and enhance their adoption to improve smoking cessation rates.

Among major states, Kerala had the highest quit ratio (49.0%), which can be attributed to the tobacco control efforts in the state. In addition to the 15 tobacco cessation centers (TCC) established as part of the National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP), the state has established 100 additional smoking cessation centers at the family health center level35. Other states like Bihar and Punjab, which reported quit ratios of over 30%, established deaddiction centers or TCCs in addition to those under the NTCP35. These indicate that states that invested in improving the availability and accessibility of cessation support, in addition to those provided under the NTCP, had better quit ratios. A major challenge, however, in the provision of tobacco cessation services is the limited availability of TCC, their integration into routine healthcare ecosystem, and use by tobacco users29,35. The Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centers (HWCs) could serve to address these bottlenecks. The HWCs are a strategic intervention to provide comprehensive health and wellness services at the grassroots, with over 150,000 functional HWCs across the country36. Providing tobacco cessation services at HWCs and integrating them with the tobacco control ecosystem (such as tobacco cessation centers, government-supported mCessation programmes, and government-supported quitline and counselling programmes) could improve the quit ratio.

Our findings reflect the positive impact of education level on tobacco use and cessation behaviors similar to what has been previously reported16,33. However, tobacco use in India continues to be concentrated among individuals with limited education, who are documented to have low levels of perceived risk concerning tobacco use and a limited awareness about cessation support37,38. A recent study of the National Tobacco Quit Line services (NTQLS) in India reported that a substantial percentage of tobacco users calling the toll-free quitline were not aware that the quitline number that they called was for the purpose of seeking cessation support39. Further tobacco use is concentrated in rural settings, which have a limited availability of cessation support and awareness among the people, which could be translating to rural–urban differentials in tobacco quit ratios16,25,38.

Among health behaviors, the individuals practicing yoga/asanas/meditation/pranayama had higher quit ratios. The use of yoga, meditation, and mindfulness to facilitate quit attempts was previously documented40,41,42. Given that most smoking quit attempts in India are unassisted, our findings hint at the potential for yoga, meditation, and mindfulness approaches to facilitate unassisted quitting. However, further research is required in this direction. Those reporting to be current users of smokeless tobacco products had a significantly greater odds of quitting. Co-use of smoking and smokeless tobacco is prevalent in India, with approximately 9% of the population in this age group reporting co-use of tobacco products43. Individuals who may have quit smoking could be continuing to use smokeless tobacco, which may explain our finding. Further, smokeless tobacco is perceived to be a less harmful alternative44,45, and substitution of smoking products with smokeless tobacco has been documented as a means of attempting to quit smoking in India46. Tobacco alcohol co-use is known to be associated with nicotine addiction47,48,49, which explains our finding of the low smoking quit ratios among alcohol users.

Quit ratio among life-time combustible tobacco users is primarily driven by older age, healthcare provider visits, and chronic disease diagnosis. Despite the apparent benefits of quitting smoking at an early age, the quit ratio among middle-aged adults (45–60 years) is substantially less. The findings indicate the need to improve accessibility of tobacco cessation services, in terms of the tobacco cessation centers, quitline services, and counselling among all tobacco users irrespective of their age and disease status. Given that most smoking quit attempts in India are unaided5, developing culturally relevant smoking cessation self-help tool-kits to support unassisted quit attempts could be helpful. Considering the role of the healthcare provider in facilitating quitting, interventions to integrate tobacco use screening and cessation advice to routine clinical care could aid to improve quit ratio.

Conclusions

The less-than-optimal quit ratios at the national and state level among people who are life-time combustible tobacco users in India are reflective of the bottlenecks in tobacco cessation support availability, access and use. Better financing and management of tobacco cessation centers and focused community awareness programmes, and mechanisms to aid unassisted quitting can aid to improving quitting. Further, integrating the tobacco control efforts with HWCs, and ensuring the integration of “Ask”, “Advice”, and “Refer” for tobacco cessation in routine clinical care irrespective of the disease status of the individuals are needed.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings provide robust, policy-relevant evidence on smoking quit ratios at both state and national levels in India, highlighting the significant influence of socio-demographic characteristics, health status, and health behaviors. A major strength of this study is its use of data from the most recent Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, which offers invaluable insights into the smoking cessation trends within this age group. While the research is limited by its cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reported information, and the potential for response bias in socially desirable behaviors, the evidence presented remains crucial. Despite the limitations, our study contributes important insights for shaping effective smoking cessation and tobacco control policies in India.

Data availability

The data used in this study was obtained from the International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai which was the nodal agency for LASI India survey. The dataset can be accessed from the IIPS through a formal request to the investigators of the LASI project through the LASI data catalogue available at (https://www.iipsdata.ac.in/datacatalog_detail/5).

References

WHO. Tobacco. [10th March 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco?form=MG0AV3 (2023).

Baker, C. L. et al. Benefits of quitting smoking on work productivity and activity impairment in the United States, the European Union and China. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 71(1), e12900 (2017).

WHO, WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2019: offer help to quit tobacco use (World Health Organisation, 2019).

TISS Mumbai, et al. Global Adult Tobacco Survey FACT SHEET|INDIA 2016–17. Available from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/india/health-topic-pdf/tobacco/gats-india-2016-17-factsheet.pdf?sfvrsn=27b93d0e_2 (2017).

Sreeramareddy, C. T. & Kuan, L. P. Smoking cessation and utilization of cessation assistance in 13 low- and middle-income countries - changes between Two Survey Rounds of Global Adult Tobacco Surveys, 2009–2021. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 14(3), 1257–1267 (2024).

Hummel, K. et al. Quitting activity and use of cessation assistance reported by smokers in eight European countries: Findings from the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob. Induc. Dis. 16(Suppl 2), 6 (2018).

Gawde, N. C. & Quazi Syed, Z. Determinants of quit attempts and short-term abstinence among smokers in India: Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2016–17. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 24(7), 2279–2288 (2023).

Ruhil, R. Correlates of the use of different tobacco cessation methods by smokers and smokeless tobacco users according to their socio-demographic characteristics: Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) India 2009–10. Indian J. Community Med. 41(3), 190–197 (2016).

Henley, S. J. et al. Smoking cessation behaviors among older U.S. adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 16, 100978 (2019).

Leventhal, A. M., Dai, H. & Higgins, S. T. Smoking cessation prevalence and inequalities in the United States: 2014–2019. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 114(3), 381–390 (2022).

Giovino, G. A. et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: An analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet 380(9842), 668–679 (2012).

Demissie, H. S. et al. Factors associated with quit attempt and successful quitting among adults who smoke tobacco in Ethiopia: Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2016. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 8, 12 (2022).

Hughes, J. R., Carpenter, M. J. & Naud, S. Do point prevalence and prolonged abstinence measures produce similar results in smoking cessation studies? A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12(7), 756–762 (2010).

Piper, M. E. et al. Defining and measuring abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions: An updated review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22(7), 1098–1106 (2020).

Mini, G. K. et al. Factors influencing tobacco cessation in India: Findings from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey-2. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 24(11), 3749–3756 (2023).

Tripathy, J. P. Socio-demographic correlates of quit attempts and successful quitting among smokers in India: Analysis of Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2016–17. Indian J. Cancer 58(3), 394–401 (2021).

Corsi, D. J. et al. Tobacco use, smoking quit rates, and socioeconomic patterning among men and women: A cross-sectional survey in rural Andhra Pradesh, India. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21(10), 1308–1318 (2020).

Cramer, H. et al. Is the practice of yoga or meditation associated with a healthy lifestyle? Results of a national cross-sectional survey of 28,695 Australian women. J. Psychosom. Res. 101, 104–109 (2017).

Cartwright, T. et al. Yoga practice in the UK: A cross-sectional survey of motivation, health benefits and behaviours. BMJ Open 10(1), e031848 (2020).

Rodríguez-Cano, R. et al. Hazardous alcohol drinking as predictor of smoking relapse (3-, 6-, and 12-Months follow-up) by gender. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 71, 79–84 (2016).

Hejjaji, V. et al. A combined community health worker and text messagingbased intervention for smoking cessation in India: Project MUKTI - A mixed methods study. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 7, 23 (2021).

Kruse, G. R. et al. Tobacco use and subsequent cessation among hospitalized patients in Mumbai, India: A longitudinal study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22(3), 363–370 (2020).

Mathew, B. et al. Can cancer diagnosis help in quitting tobacco? Barriers and enablers to tobacco cessation among head and neck cancer patients from a tertiary cancer center in South India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42(4), 346–352 (2020).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), et al. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave-1, 2017–18, India Report. (International Institute of Population Sciences, 2020).

Parker, M. A. et al. Trends in rural and urban cigarette smoking quit ratios in the US from 2010 to 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 5(8), e2225326–e2225326 (2022).

Mbulo, L. et al. Contrasting trends of smoking cessation status: Insights from the stages of change theory using repeat data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey, Thailand (2009 and 2011) and Turkey (2008 and 2012). Prev. Chronic Dis. 14, E42 (2017).

Dhumal, G. G. et al. Quit history, intentions to quit, and reasons for considering quitting among tobacco users in India: Findings from the Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation India Wave 1 Survey. Indian J. Cancer 51(Suppl 1), S39-45 (2014).

Verma, M., Tripathy, J. P. & Kumar, M. Intention to quit tobacco due to media advertisements in India: Findings from Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2016–17. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 25(6), 1969–1975 (2024).

Gupta, R. et al. Tobacco cessation in India-Current status, challenges, barriers and solutions. Indian J. Tuberc. 68, S80–S85 (2021).

Sequeira, M. et al. Perspectives of smokers, smokeless tobacco users and cessation practitioners in India: A qualitative study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 51, 194–200 (2024).

Assari, S. & Sheikhattari, P. Smokers with multiple chronic disease are more likely to quit cigarette. Glob. J. Epidemol. Infect. Dis. 4(1), 60–68 (2024).

Le, T. T. T., Mendez, D. & Warner, K. E. The benefits of quitting smoking at different ages. Am. J. Prev. Med. 67(5), 684–688 (2024).

Pradhan, M. R. & Patel, S. K. Correlates of tobacco quit attempts and missed opportunity for tobacco cessation among the adult population in India. Addict. Behav. 95, 82–90 (2019).

NTCP. National Tobacco Control Programme-Total Number of persons who received counselling. Available from: https://ntcp.mohfw.gov.in/dashboard (2024).

NTCP, Details of Tobacco Cessation Centres/Facilities. (National Tobacco Control Programme, New Delhi, 2018).

Lahariya, C. Health & wellness centers to strengthen primary health care in India: Concept, progress and ways forward. Indian J. Pediatr. 87(11), 916–929 (2020).

Veena, K. P. et al. Trends and correlates of hardcore smoking in India: Findings from the Global Adult Tobacco Surveys 1 & 2. Wellcome Open Res. 6, 353 (2021).

Kankaria, A., Sahoo, S. S. & Verma, M. Awareness regarding the adverse effect of tobacco among adults in India: Findings from secondary data analysis of Global Adult Tobacco Survey. BMJ Open 11(6), e044209 (2021).

Kumar, R. et al. Quitting tobacco through quitline services: Impact in India. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2024.2976 (2024).

Jackson, S. et al. Mindfulness for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4(4), Cd013696 (2022).

Girishankara, K. S. M. et al. Effect of mind sound resonance technique on pulmonary function and smoking behavior among smokers - A prospective randomized control trial. Int. J. Yoga 17(3), 222–231 (2024).

Black, D. S. & Kirkpatrick, M. G. Effect of a mindfulness training app on a cigarette quit attempt: an investigator-blinded, 58-county randomized controlled trial. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 7(6), pkad095 (2023).

Bharati, B., Sahu, K. S. & Pati, S. Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use in India and its association with various occupations: A LASI study. Front. Public Health 11, 1005103 (2023).

Ravi, P. et al. Qualitative analysis of opinions and beliefs associated with the use of tobacco dentifrice among individuals attending a tobacco counselling session. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 24(12), 4293–4300 (2023).

Chatterjee, N., Gupte, H. A. & Mandal, G. A qualitative study of perceptions and practices related to areca nut use among adolescents in Mumbai, India. Nicotine Tob. Res. 23(10), 1793–1800 (2021).

Deepak, K. G. et al. Smokeless tobacco use among patients with tuberculosis in Karnataka: The need for cessation services. Natl. Med. J. India 25(3), 142–145 (2012).

Oswal, K. et al. Prevalence of use of tobacco, alcohol consumption and physical activity in the North East region of India. J. Cancer Policy 27, 100270 (2021).

Singh, P. K. et al. Mapping the triple burden of smoking, smokeless tobacco and alcohol consumption among adults in 28,521 communities across 640 districts of India: A sex-stratified multilevel cross-sectional study. Health Place 69, 102565 (2021).

Benowitz, N. L. Nicotine addiction. Prim. Care 26(3), 611–631 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge the support of IIPS, Mumbai, and the LASI working group for permitting us to use the LASI microdata for our work. Additionally, the first author is a visiting scholar at the University of California San Francisco, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education and received support from the United States-India Educational Foundation through the Fulbright-Nehru Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PBK, KM & EP conceptualized the study, PBK sourced the data, and conducted the analysis. PBK developed Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and Figs. 1, 2, 3. PBK, EM & EP prepared and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the finalized version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author/s declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was an analysis of the deidentified secondary data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India. The data was publicly available, and does not include any form of personally identifiable information. The original LASI survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Indian Council for Medical Research. Informed consent and the consent to use data for the purpose of secondary research was obtained from participants during the survey. The data cleaning, analysis and the procedures reporting findings ensured protecting participant privacy. The deidentified data used in this analysis was obtained through a formal application to the LASI nodal agency, thus no additional ethics committee approval was requested.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kodali, P.B., Maniyara, K. & Palle, E. Smoking cessation among middle-aged and older adults in India. Sci Rep 15, 40017 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23584-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23584-w