Abstract

Exponential kernels have been used considerably in statistics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence for tasks such as kernel principal component analysis (Kernel PCA), support vector machines(SVM), visualization, clustering, and pattern recognition. Selecting different bandwidth parameters for the exponential kernel can lead to varying insights about the data. Hence, understanding the theoretical impact of the bandwidth parameter is crucial. This paper investigates the influence of the exponential kernel’s bandwidth parameter on the approximation of continuous operators by their empirical counterparts, supported by some experimental algorithms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exponential kernels are widely recognized as an effective choice in kernel-based methods. In learning algorithms and artificial intelligence, choosing an appropriate bandwidth parameter for a kernel is as important as selecting the kernel itself1,2. In most cases, statistical learning and data analysis depend on estimating the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the kernel matrix, which represents the empirical version of a continuous operator. This is because we mostly use kernel functions to map the data to a large space, where the dimension could be infinite, and thus we need to deal with continuous functions. In the last decades, several works studied the connection between the two operators using perturbation theory. The first study that involved defining an integral operator by a kernel appeared in 1998 by Koltchinskii and in 2000 by Koltchinskii and Giné, where they studied the connection between the spectrum of the integral operator and the sectrum of their empirical counterpart. In 2010, another study by Rosasco3, which was focusing on any positive definite kernel has shown how close the egienvalues of the two operators to each other and the eigenvectors to their continuous counterpart. In a recent study, we were able to apply the same technique to Gaussian kernels4. We have shown the impact of the bandwidth parameter of the Gaussian kernels on the closeness of the two versions of the operators.

In this paper, we focus on exponential kernels and their bandwidth parameter. Therefore, it is essential to discuss the Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space(RKHS) of the exponential kernel and shows its orthonormal basis(ONB) explicitly. With the help of Steinnwart’s results, we were able to derive an explicit description of the RKHS induced by the exponential kernel5, which is crucial in obtaining some bounds in the following sections. We then study the convergence of certain operators defined by the exponential kernel on the RKHS, and make some bounds that can be extended to the convergence of eigenvalues and eigenfunctions. To support our theoretical results and examine the impact of the exponential kernel’s bandwidth parameter, we provide some examples using support vector machine(SVM). These examples illustrate how the bandwidth parameter affects the performance of the nonlinear classifier in support vector machines.

Settings and preliminaries

In this section, we introduce some notations and discuss some properties of the exponential kernel and its corresponding reproducing kernel Hilbert space.

Reproducing Kernel Hilbert spaces induced by exponential kernels

Let \(\mathcal {X}\) be a nonempty subset of \(\mathbb {R}^d\), and let \(k_\lambda :\mathcal {X} \times \mathcal {X} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be the exponential kernel6 given by

where \(\lambda\) is the bandwidth parameter of \(k_\lambda\). Then, the feature map \(\Phi (\textbf{x}_1): \mathcal {X} \rightarrow \mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X})\) of the Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS) \(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X})\) induced by \(k_\lambda (\textbf{x}_1,\textbf{x}_2)\) is given by

\(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X})\) admits the dot product as follows

The reproducing property of the kernel \(k_\lambda\) can be defined by

Set

Therefore, all evaluation functions are bounded7,8, that is

Integral operators defined by exponential reproducing kernel

Exponential kernels are commonly used in machine learning applications and learning algorithms. The bandwidth parameters chosen for exponential kernels have a significant impact on the performance of these algorithms. For that reason, our contribution is to provide a theoretical analysis of the extent of this effect. In 20103, Rosasco considered the case of a positive kernel and established some bounds on eigenvalues and spectral projections; however, he did not investigate the impact of the kernel parameter. In our case, the analysis will be centered on exponential kernels. We derive some bounds that illustrate the effect of these parameters.

First of all, let \(\mathcal {X} \subset \mathbb {R}^d\) and \(k_\lambda :\mathcal {X} \times \mathcal {X} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be the exponential reproducing kernel defined by

Let \(\rho\) be a probability measure on \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )\) be the space of square-integrable functions with the norm \(\Vert f\Vert _{\mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )} = \langle f, f \rangle _{\mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )} = \int _\mathcal {X} |f(\textbf{x}_1)|^2 d\rho (\textbf{x}_1)\). Let \(L_{k_\lambda }: \mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho ) \rightarrow \mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )\) be an integral operator defined by

for all \(\textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal {X}\), \(\lambda \in \mathbb {R}^+\), and \(f \in \mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )\). We know that \(e^{\frac{\langle \textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2 \rangle }{\lambda }} \le \kappa _\lambda\) for all \(\textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal {X}\). Therefore, \(L_{k_\lambda }\) is a bounded operator.

Now assume that we are given a set of points \(\{ \textbf{x}_1,\ldots ,\textbf{x}_n\} \subset \mathbb {R}^d\) sampled i.id. according to \(\rho\). The entries of the \(n \times n\) kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\) are computed by \(K_{i,j} = \frac{1}{n} e^{\frac{\langle \textbf{x}_i, \textbf{x}_j \rangle }{\lambda }}\). Let \(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X})\) be the exponential reproducing kernel Hilbert space and define the operators \(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}, \mathcal {T}_n: \mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X}) \rightarrow \mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X})\) by

Donate the inclusion map \(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathcal {X}) \hookrightarrow \mathbb {L}^2(\mathcal {X},\rho )\) and its adjoint operator by \(\mathcal {I}_n\), \(\mathcal {I}_n^*\) respectively.

Results

In this section, we begin by introducing an explicit orthonormal basis of the exponential reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS), as stated in the following proposition. The result is deduced from Steinwart’s results5 for the Gaussian kernel.

Proposition 1

Let \(n_1,\ldots ,n_d \in \mathbb {N}\) and \(\textbf{u}:= (n_1,\ldots , n_d)\). Define \(e_{n_j}: \mathbb {R} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\), as follows,

Then, the system \(e_u(x) = e_{n_1}(x_1)\otimes \cdots \otimes e_{n_d}(x_d)\) serves an orthonormal basis of \(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathbb {R}^d)\), with \(k_\lambda (\textbf{x}_1,\textbf{x}_2)= e^{\frac{\langle \textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2 \rangle }{\lambda }}\) being its reproducing kernel.

Proof

Let us prove that \(k_\lambda (\textbf{x}_1,\textbf{x}_2)\) is the reproducing kernel of \(\mathcal {H}_{k_\lambda }(\mathbb {R}^d)\), while the reader can easily verify that the system forms an orthonormal basis using the same technique as in the Gaussian RKHS case5. To proceed, let \(\textbf{x}_1,\textbf{x}_2 \in \mathbb {R}^d\) with \(\textbf{x}_1= (x_{11}, x_{12}\ldots ,x_{1d})\) and \(\textbf{x}_2=(x_{21}, x_{22}\ldots ,x_{2d})\) then the orthonormal basis we obtain

\(\square\)

Now, the above proposition leads us to another proposition in which we can compute the exact norm of the Hilbert-Schmidt operator \(\mathcal {T}_\mathcal {N}\) (7).

Proposition 2

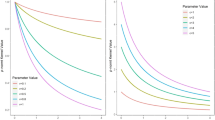

Let \(\mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}\), and \(\rho (x_1)\) be a normal distribution with a density \(\phi _\sigma (x_1) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi }} e^{-\frac{x_1^2}{2 \sigma ^2}}\). Given the assumptions stated above, \(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\) is a Hilbert-Schmidt operator, and \(\Vert \mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\Vert _{HS}^2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-4\frac{\sigma ^4}{\lambda ^2}}}\).

Proof

First of all, for all \(x_1, x_2 \in \mathbb {R}\) we have

Recall

We know that \(\{e_n(x_1)= \sqrt{\frac{1}{\lambda ^{n} \cdot n!}} x_1^n, \ n=0,1,\ldots \}\) is an orthonormal basis for the exponential RKHS \(\mathcal {H}_{\kappa _\lambda }(\mathbb {R})\). Now we can find the exact value of \(\Vert \mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\Vert _{HS}^2\) as follows,

\(\square\)

Corollary 1

If \(\mathcal {X}=\mathbb {R}^d\), then \(\Vert \mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\Vert ^2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 -4 \frac{\sigma ^4}{\lambda ^2}}}\).

The following theorem will provide a new bound that depends on \(\sigma\) and the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) for the difference \(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N} -\mathcal {T}_n\).

Theorem 1

\(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_n\) are Hilbert-Schmidt operators. Given the assumptions stated above with probability \(1 - 2 e^{-\tau }\)

Proof

Assume that we have a sequence of random variables \((\eta )_{i=1}^n\) in the Hilbert space of Hilbert-Schmidt operators given by

It is obvious that the mean of the random variable \(\eta _i\) is zero, i.e. \(E(\eta _i)=0\). We can compute that

From Proposition 2, we have \(\Vert \mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N} \Vert _{HS} = \left( \frac{1}{1- 4 \frac{\sigma ^4}{\lambda ^2}} \right) ^\frac{1}{4}\) and follows

Now, we apply Pinelis’s9 results on concentration inequalities in Hilbert spaces with confidence \(1- 2 e^{-\tau }\)

\(\square\)

As can be seen in Theorem 1, the Hilbert-Schmidt operator of the difference between the operators \(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_n\) has been bounded. As a result, we introduce the next proposition, which bounds the \(\ell _2\)-distance between the spectrum of \(\mathbb {K}_n\) and the spectrum of \(L_{k_\lambda }\).

Proposition 3

There are extended enumerations \(\{ \beta _j\}_{j \ge 1}\), \(\{ \hat{\beta _j}\}_{j\ge 1}\) of discrete eigenvalues for the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\), \(\mathbb {K}_n\) respectively such that

with a probability greater than \(1-2 e^{-\tau }\).

Proof

First, the extended enumerations \(\{ \beta _j\}_{j \ge 1}\), \(\{ \hat{\beta _j}\}_{j\ge 1}\) of discrete eigenvalues for the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\), \(\mathbb {K}_n\) respectively, are also extended enumerations of discrete eigenvalues for \(\mathcal {T}_\mathbb {N}\), and \(\mathcal {T}_n\) respectively3. Thus, the following inequality holds

Now, from Theorem 1 we obtain the following

\(\square\)

It is evident that Proposition 3 provides us with a bound that contains influential factors such as the number of examples n and the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\). Minimizing this bound means that we minimize the difference between the eigenvalues of the operators of \(\mathbb {K}n\) and \(L_{k_\lambda }\), which means that they become closer to each other. For example, when n reaches infinity, the eigenvalues will be almost the same. We can also minimize the targeted bound by maximizing the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\). We should remember that approximating the integral operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) by its empirical version, which is the kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\) is necessary to have a theoretical understanding of what happens in learning algorithms. Since, Proposition 3 shows how we can estimate the eigenvalues of \(L_{k_\lambda }\) by the eigenvalues of \(\mathbb {K}_n\), the following theorem will show how we estimate the eigenfunctions of \(L_{k_\lambda }\) by the eigenvectors of \(\mathbb {K}_n\).

Theorem 2

Assume that \(\mathcal {M}\) is the number of the first distinct eigenvalues of the operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) with a total number of multiplicities r that satisfy \(\beta _1 \ge \cdots \ge \beta _r > \beta _{r+1}\), and the rank of the kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\) is q. Let \(\hat{\textbf{u}}_1,\ldots ,\hat{\textbf{u}}_q\) be the eigenvectors of \(\mathbb {K}_n\), which correspond to the nonzero eigenvalues in a nonincreasing order, and \(\hat{v}_1,\ldots ,\hat{v}_q\) be the eigenfunctions of \(\mathcal {T}_n\) obtained by the Nyström extension.

Denote by \(\mathcal {A}_M\) the orthogonal projection from the Hilbert space of square integrable functions \(\mathbb {L}^2(\mathbb {R}^d,\rho )\) onto the span of the eigenfunctions corresponding to the eigenvalues \(\beta _1,\ldots ,\beta _q\). Assume that we are given \(\tau >0\), and n number of examples such that

then the following inequality holds true

with confidence at least \(1- 2 e^{-\tau }\).

Proof

Assume that the elements of the set \(\{u_1, u_2, u_3,\ldots .\}\) are orthonormal eigenfunctions of the operator \(L_{\kappa _\lambda }\) with corresponding eigenvalues \(\{\beta _1, \beta _2, \beta _3,\ldots . \}\) that are strictly positive, and the elements of the set \(\{v_1, v_2, v_3,\ldots .\}\) are the corresponding orthonormal eigenfunctions of the operator \(\mathcal {T}_\mathcal {N}\). Let \(\{\hat{v}_1, \hat{v}_2,\ldots ,\hat{v}_q\}\) be another set of orthonormal eigenfunctions of \(\mathcal {T}_\mathcal {N}\). Assume that the number of examples we are given is n, and

Using Theorem 1, Kato’s theorem10,11, and Zwald’s results12, with high confidence we derive

Define the orthogonal projections \(\mathcal {A}^{\mathcal {T}_\mathcal {H}}\), and \(\mathcal {A}^{\mathcal {T}_\mathcal {N}}\) as follows

Then, we yield

Now, each one of \(\{v_1, v_2, v_3,\ldots \}\), and \(\{\hat{v}_1, \hat{v}_2,\hat{v}_3,\ldots \}\) is an orthonormal basis for \(\mathcal {H}_{\kappa _\lambda }(\mathbb {R}^d)\). Therefore, we obtain

Now, we apply Mercer’s theorem to obtain the following

and

\(\square\)

As can be seen in Theorem 2, the relationship between the eigenfunctions of the operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) and the eigenfunctions of the operator \(\mathbb {K}_n\) is similar to the relationship between their eigenvalues. The impact of the number of examples n and the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) on the closeness between the eigenfunctions is almost the same.

Learning algorithms using the exponential kernel

In this section, we provide some examples to test the performance of the exponential kernel at different bandwidth values. In fact, the exponential kernel can be used in many learning algorithms, and sometimes performs better than any other kernels. This would depend heavily on how we select the value of the bandwidth parameter. In addition, it is essential that our experiments include testing performance across different learning algorithms. Therefore, we have chosen support vector machine (SVM), and kernel principal component analysis (kernel PCA) as examples for our study. The experiments are conducted on both synthetic and real data.

Support vector machine experiment using the exponential kernel

In machine learning, support vector classifiers are a learning algorithm used to classify data when it has two separable classes. The main idea of support vector classifiers is to construct the optimal hyperplane that best separates the two classes. The hyperplane can take two forms: linear, when the data are linearly separable, and nonlinear, when the data are not linearly separable. In the non-linear case, we need to use a kernel function that embeds the data into a feature space that admits the “dot product” as a similarity measure. Through the kernel functions, the data are mapped to a reproducing kernel Hilbert space, where the dot product between two elements can be easily computed. Therefore, in order to understand the efficiency of any kernel, it is important to study its mathematical properties. In other words, we need to place the arguments about kernel performance in a mathematical framework. In this paper, our goal is to provide a mathematical explanation for the performance of a particular kernel “the exponential kernel(1)” when using different values for its bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\). Support vector classifiers are considered the best choice for our experiment. This is due to the fact that the support vector machine is a highly useful tool in machine learning, and also because the bandwidth parameter significantly affects its efficiency. Now, we are in a suitable position to introduce the support vector classifier algorithm with the exponential kernel, and show some examples with different values for the bandwidth parameter.

Support vector classifier algorithm using the exponential kernel

Suppose that our training data are a set of vectors \(\{ \textbf{x}_1,\ldots , \textbf{x}_n \}, \textbf{x}_i, \textbf{x}_j \in \mathbb {R}^d, i,j \in \{1,\ldots , n\}\) with two classes \(y_j \in \{ -1, +1 \}\). Since we are dealing with exponential kernels, we will assume that the input data are not linearly separable. Our goal is to construct a hyperplane that separates the two classes, but in practice it might not exist due to the overlapping points. As a consequence, soft-margin hyperplanes are introduced to allow the violating points to lie within the margin. This is done by adding what they call “slack variables” to the optimization problem of support vector classifiers1,13, which can be seen below.

In order to compute the support vector classifier using the exponential kernel, the decision function will take the form,

where \(\alpha _i \in \mathbb {R}^d\), and b is a real number called the threshold. To compute the optimal support vector classifier that accepts some violating points, we need to solve the following optimization problem for some \(C > 0\),

The elements of the sequence \(\xi _1,\ldots ,\xi _n\) are called slack variables. A point \(( \mathbf {x_i}, y_i)\) satisfying the constraint 14 at \(\xi _i = 0\) will not be considered a margin error, while the non-zero \(\xi _i\) corresponds to a margin error. The vector \(\textbf{w}\) can be calculated as follows:

where the coefficient \(\alpha _i\) takes zero if the corresponding point \((\textbf{x}_i, y_i)\) does not meet the constraint 14. In order to compute the coefficients \(\alpha _i\), we need to solve the following quadratic problem:

The threshold b can be calculated using the following equation:

Support vector classifier experiment

In this experiment, our goal is to evaluate the performance of the exponential kernel 1 when using different values of its bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) with the support vector classifier. Therefore, we randomly generate sets of points \(*\)’s and \(+\)’s within the unit circle, labeling those in the first and third quadrants as \(+1\), and those in the second and fourth quadrants as \(-1\). First, we create 100 points in each quadrant and train the support vector classifier at three different values of \(\lambda\): 0.2, 0.6, and 1. Second, we create 150 points in each quadrant and train the support vector classifier using the same values of \(\lambda\). The dataset used in this paper is based on synthetic data created with Simulink (Mathworks, Natick, MA)14, and modified by the author to fit our findings. These modifications include control signals such as the number of examples in which the hyperplane classifiers are constructed using the exponential kernel with different bandwidth parameters.

As we can see in Figs. 1, 2, and 3, the number of examples is 100 in each quadrant, and the support vector classifiers are the blue lines that separate the green stars from the red pluses. The values we have chosen for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) are 0.20, 0.60 and 1.00, and the out-of-sample misclassification rates are \(4.50\%\), \(4.75\%\) and \(5.70\%\) respectively. These rates indicate that the exponential kernel performs well for the three different values, but also indicate that decreasing the value of \(\lambda\) leads to overfitting, while increasing its value leads to underfitting. In practical applications, it is very important to choose a value for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) that helps constructing the best hyperplanes for generalizations. In our case, 0.60 seems to be the best value we can choose for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) from the three values, and we avoid 0.2, and 1.00 due to overfitting and underfitting respectively.

On the other hand, our theoretical results show how the closeness between the integral operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) and the operator \(\mathbb {K}_n\) can be controlled by the value of \(\lambda\) and the number of examples n. We know that the operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) works on a large space, which is the Hilbert space of square integrable functions \(\mathbb {L}^2(\mathbb {R}^d,\rho )\). Mapping data into that space means that we can use a high dimensional space that helps detecting more information about data. Kernel functions including the exponential kernel are used to embed the data into a high dimensional space. The kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\) is just an empirical version of the operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\). As previously noted that the closeness between the two operators increases by increasing the number of examples. In Figs. 4, 5, and 6, we have increased the number of examples from 100 to 150 using the same values of \(\lambda\), which has decreased the out-of-sample misclassification rates from \(4.50\%\), \(4.75\%\), and \(5.70\%\) to \(3.67\%\), \(3.67\%\), and \(4.50\%\) respectively.

In terms of our theoretical results on the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) and how they clarify the variation in the performance of support vector classifiers when using different values of \(\lambda\), we have stated in “Results” that increasing the value of the bandwidth would minimize the norm of the difference between the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\) and \(\mathbb {K}_n\), which means we succeeded in embedding the data into high dimensional space, but they are mapped very closely. As a consequence, the ability of the exponential kernel of detecting any information about the data will be nearly lost. For instance, if \(\lambda\) goes to infinity, the exponential kernel will be equal to 1, and will be no longer able to distinguish between any two points. On the other hand, a very small value of \(\lambda\) increases the difference between the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\) and \(\mathbb {K}_n\), but it leads to very high values for the exponential kernel that are not appropriate to learn about the data. One of the significant advantages of our theoretical results is that we can select the optimal value for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) by avoiding values that can make a huge impact on the difference between the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\), and \(\mathbb {K}_n\). Therefore, in our examples we have avoided the values that are very close to zero or larger than one due to the fact that they can make a significant undesirable change in the performance of support vector classifiers.

A multi-class support vector classifier experiment

In this section, we have so far explained only a binary classification, where the class labels can be only \(+1\) or \(-1\). However, in many cases, real data can have more than two classes. Therefore, it is important to test the impact of the value of the bandwidth parameter on the performance of the exponential kernel when dealing with multiple classes. It is known that the multi-class support vector classifiers are just an extension of the binary classification technique.

As can be seen in the Figs. 7 and 8, the Fisher Iris dataset was used to construct a support vector classifier that separates three species of 150 flowers, which are setosa, versicolor, and virginica with the colors red, blue, and green consecutively15. We applied the SV classifier using the exponential kernel at two different values for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\), which are 0.29 and 2. At \(\lambda = 0.29\), the SV classifier achieved an accuracy rate of \(78\%\), which is very reasonable because the noise is significant, as we can see the interference between the blue and green points in Fig. 7, and the three groups are represented in a 2-dimensional space16. In Fig. 8, we increased \(\lambda\) to 2, which decreased the accuracy rate to \(71\%\). This is because the large values of \(\lambda\) lead to almost a linear boundary decision that separates the data sets with more errors.

Note that an accuracy rate of more than \(95\%\) can be easily achieved when representing the data in a 3-dimensional space, but testing the performance of the exponential kernel when dealing a lot of noise is important. In this example, the results show that small values for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) lead to overfitting, while large values lead to underfitting, which is consistent with our example on the binary classification. In both examples, the optimal values for \(\lambda\) were between 0.2 and 0.7. The relationship between the results of this example and the theoretical results is similar to what we have explained in the binary classification case.

Kernel principal component analysis experiment

Our second choice of a kernel-based method for our experiment is kernel principal component analysis (kernel PCA). This is because kernel PCA is a very useful technique, in which we compute principal components in high-dimensional spaces that are related to input space by kernels, which means reducing the dimensionality of nonlinear data. The exponential kernel is one of the best options for kernel PCA method. Furthermore, different values of the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) can show different information about the data. In this section, we present some experiments on kernel PCA using the exponential kernel on two datasets which are Fisher Iris dataset and Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset. The fisher Iris dataset has 150 samples from three species, which are setosa, versicolor, and virginica with colors blue, orange, and green consecutively15. The Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset contains 569 samples and 30 features, and the samples are labeled as malignant or benign with color blue and red consecutively17.

First, we computed the first eigenvectors of the exponential kernel matrix in which we projected the original data for visualization. In the case of Iris dataset, the first eigenvectors were computed at three different values for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\), which are 3.33, 5, and, 11.11 as can be seen in Figs. 9, 10, and 11 consecutively16. Clearly, this shows that a small value of \(\lambda\) tells us more about clusters, while a large value tells us more about the locations, and improves the separability of the data. In the case of Breast Cancer Wisconson dataset, a similar result were observed in Figs. 12, and 13, where the data exhibited a high degree of clustering at \(\lambda = 100\), and a high degree of separability at \(\lambda = 100000\).

The interpretation of our theoretical results for these observations is that a small value of \(\lambda\) leads to a high clustering, because the data are mapped into a Hilbert space very closely. Meanwhile, a large value of \(\lambda\) shows more variability and improves the separability of the data. This is because the data are embedded into a high-dimensional Hilbert space while preserving the differences among the examples. In the theoretical sense, increasing the value of \(\lambda\) leads to a high closeness between the kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\), and the operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\), which is obvious from the bound of their difference in the previous section.

Conclusion and future scope

In this paper, we investigated the impact of the bandwidth parameter of the exponential kernel on estimating the integral operator \(L_{k_\lambda }\) by its empirical version, which is the kernel matrix \(\mathbb {K}_n\) as well as the number of examples from a theoretical perspective. Therefore, we have established a bound that controls the difference between their eigenvalues, and another bound controls the difference between their eigenfunctions. These bounds contain the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\), and the number of examples n, which means we can use them to reach the targeted bound for many learning algorithms. In fact, the more examples we use the more closeness between the two operators we obtain, while selecting small values for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) can enlarge the difference between the operators.

In our experiments, increasing the number of examples have shown clear improvement in the performance of support vector classifiers. The value of the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) would be the value that ensures the bound between the operators \(L_{k_\lambda }\) and \(\mathbb {K}_n\) is not too large or too small. In the mathematical sense, the data should be mapped to the perfect locations in a high dimensional space that are suitable for learning. In kernel PCA experiments, we can use small values for the bandwidth parameter \(\lambda\) to learn about clusters, and large values to learn about differences and separability in the data. Minimizing the closeness between the operators \(\mathbb {K}_n\) and \(L_{k_\lambda }\) can be obtained by increasing the value of \(\lambda\), which preserves and highlights the differences, providing a better visualization.

Our future studies will be extended to other kernels such as the rational quadratic kernel and the spherical kernel. These studies will provide a deep understanding of the Hilbert spaces established by such kernels as well as the impact of their bandwidth parameters on learning algorithms. These techniques are very important to improve the performance of any kernel in any kernel-based method.

Data availability

All the datasets are available online. We have used three datasets one of them is synthetic and two are real as follows : 1. The synthetic dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available at https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/support-vector-machines-for-binary-classification.html#buax656-1. 2. The second dataset is Fisher’s Iris dataset. It is available on: https://scikit-learn.org/1.5/auto_examples/datasets/plot_iris_dataset.html. 3. The third dataset is Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset. It is available on: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.dataset.load_breast_cancer.html.

References

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (Springer, New York, 2009).

Shawe-Taylor, J. & Cristianini, N. Kernel Methods for Pattern Analysis (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2004).

Rosasco, L., Belkin, M. & Vito, E. D. On learning with integral operators. J. Mach. Res. 11, 905–934 (2010).

Almahadawi, M. A. & Cabrera, O. D. Learning with multiple kernels. IEEE Access 12, 56973–56980 (2024).

Steinwart, I., Hush, D. & Scovel, C. An explicit description of the reproducing kernel hilbert spaces of gaussian rbf kernels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 35, 4635–4643 (2006).

Isteinwart, I. & Andreas, C. (eds) Support Vector Machines (Springer, New York, 2008).

Aronszajn, N. Theory of reproducing kernels. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 68, 337–404 (1950).

Cucker, F. & Zhou, D. X. LEARNING THEORY: An Approximation Theory Viewpoint (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2007).

Pinelis, I. An approach to inequalities for the distributions of infinite-dimensional martingales. In: Dudley, R.M., Hahn, M.G., Kuelbs, J. (eds.) Probability in Banach Spaces, 8: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference, vol. 30, pp. 128–134. Birkhäuser Boston, Boston, MA (1992).

Kato, T. Variation of discrete spectra. Commun. Math. Phys. 111, 501–504 (1987).

Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators (Springer, Berlin, 1966).

Zwald, L. & Blanchard, G. On the convergence of eigenspaces in kernel principal component analysis. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 18 (eds Weiss, Y. et al.) 1649–1656 (MIT Press, Combridge, MA, 2006).

Schölkopf, B. & Smola, J. A. Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond (MIT Press, Combridge, MA, 2002).

The MathWorks, I. Support Vector Machines for Binary Classification, 25.1, (2025). https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/support-vector-machines-for-binary-classification.html#buax656-1.

Anderson, E. The species problem in irirs. Ann. Missouri Bot. 23, 457–509 (1936).

Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G. & Gramfort, A., et, a. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Wolberg, W., Mangasarian, O., Street, N. & Street, W. Breast Cancer Wisconson (Diagnostic)[Dataset].UCI Machine Learning Repository, 3.13.1, (1995). https://doi.org/10.24432/C5HP4Z.

Funding

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP: 995-156-2025). The author, therefore, acknowledges with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work is done by Mahdi A. Almahdawi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almahdawi, M.A. The impact of the exponential Kernel’s bandwidth parameter on learning algorithms. Sci Rep 15, 40936 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24761-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24761-7