Abstract

This study represents the development of an innovative solid-phase microextraction (SPME) adsorbent based on the in situ electro-polymerized polyaniline on the carbon fiber felt (PANI@CFF). The combination of PANI and CFF resulted in a synergistic enhancement of adsorption capacity, creating a novel thin film SPME adsorbent. The adsorbent was characterized using FTIR, FE-SEM, XRD, and EDX techniques. The resulting 3D adsorbent represented high porosity, chemical stability in organic solvents, easy modification, and simple operation, making it an efficient platform for preconcentration applications. The PANI@CFF was utilized to efficiently extract non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), demonstrating exceptional performance due to its unique structural properties and multifunctional groups. All of the key extraction parameters were optimized using a one-variable-at-a-time approach. The developed SPME combined with HPLC–UV offered a wide linear range (0.05–1000 µg L⁻1, R2 ≥ 0.995), high sensitivity with LOD values less than 0.03 µg L⁻1, and excellent precision (RSDs ≤ 5.7%). The excellent preconcentration factor (PF = 458‒821) and robustness of the designed adsorbent make the method suitable for trace analysis of NSAIDs in biological and environmental matrices. The proposed protocol was validated by analysis of some real samples, achieving recoveries of 80.0–113.4%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are one of the most widely used pain relievers. They inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 and are used to treat pain, arthritis, osteoarthritis, and other diseases1,2. Compared to glucocorticoid steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs are a safer, side-effect-free alternative to corticosteroids3. However, prolonged use may cause potential gastrointestinal hazards, heart attack, kidney disease, and indigestion4. NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac acid, and mefenamic acid not only pose risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health due to contamination from misuse by humans and animals, but also are known to be isolated as a persistent contaminant and have attracted the attention of scientists5,6. The analysis of NSAIDs in biological samples is very important for clinical screening and pharmacokinetic studies7. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an efficient and selective microextraction method for detecting NSAID residues8. In recent years, advanced sorbents and extraction strategies have been developed to improve selectivity and environmental compatibility9,10,11.

The intricate biological sample matrix and low drug concentrations impact the sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of detection methods. Selecting a suitable extraction technique for sample preparation, along with purification and concentration, can also decrease expenses, time, and the amount of leftover organic solvent generated as trash12. The thin-layer strategy in solid-phase microextraction (SPME) enhances extraction efficiency due to the high surface-to-volume ratio in the extraction phase13. In the area of microextraction applications, a wide range of conducting polymers such as polyaniline (PANI), polythiophene (PTh), polypyrrole (PPy), and their derivatives have been investigated for their potential applications14,15,16. Among conducting polymers, polyaniline (PANI) has gained significant attention from researchers due to its affordability, strong environmental stability, ease of production, customizable characteristics17, and distinctive physicochemical properties. PANI possesses a high density of activenitrogen-containing sites and tunable redox states, which provide versatile interaction mechanisms such as π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic attractions to the wide range of target analytes. Compared with other conducting polymers such as polypyrrole or polythiophene, these characteristics render PANI especially effective in microextraction applications. Numerous studies have demonstrated that PANI-based sorbents and coatings in solid-phase and liquid-phase microextraction systems exhibit superior extraction efficiency, enhanced selectivity, and high reusability18,19, underlining the pivotal role of PANI in advancing microextraction technologies.

The conventional chemical synthesis of PANI is based on mixing aniline with an oxidant in aqueous or nonaqueous acidic media20. Among the various methods used to synthesize PANI, electrochemical polymerization produces a polymeric material with a unique morphology distinct from granular and agglomerated bulk structures, which is different from what is obtained by conventional chemical oxidation or surface polymerization methods21. The growing attention to PANI is due not only to manifold applications, such as gas sensors, electrochemical capacitors, catalysis, memory devices, and separation, but also to exploring the mechanism of nanofiber formation in relation to other conducting polymers22. The combination of conductive polymers and carbon-based materials to diversify in PANI properties has attracted considerable attention in recent years23.

Carbon fiber felt (CFF) is a three-dimensional nonwoven material composed of randomly oriented carbon fibers thermally bonded into a mechanically stable porous network. These fibers, typically derived from PANI or pitch precursors through carbonization and graphitization, exhibit a turbostratic graphitic microstructure with a high degree of conjugated π electrons. This arrangement imparts excellent electrical conductivity, chemical resistance, and thermal stability to the material. Owing to these properties, CFF has emerged as a promising substrate for electrochemical reactions, making it an ideal choice for applications such as redox batteries, supercapacitors, lithium-ion batteries, fuel cells, and thermal insulation layers24.

The interconnected fibrous network creates hierarchical porosity, ranging from micro- to macropores, which significantly increases the specific surface area and facilitates efficient mass transfer. This porous architecture not only enhances the adsorption capacity of CFF toward a wide range of organic and inorganic pollutants but also provides abundant active sites for capturing target compounds, thereby improving the efficiency of environmental remediation procedures and expanding the dynamic range of analytical methodologies25. Beyond its role in electrochemical and environmental systems, the combination of high surface area, hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and mechanical robustness positions CFF as a multifunctional material bridging biotechnology and industrial technologies. It serves as a stable support for catalysts in energy conversion processes, a reliable scaffold for microbial colonization and biofilm formation in biotechnological applications, a lightweight, thermally stable material in high-temperature industries, aerospace, and advanced composites. Thus, CFF should be considered not merely as a passive substrate but as an active, tunable interface at the intersection of biotechnology, environmental science, energy technology, and advanced industry26,27.

For example, our previous work successfully used AT-CFF (acid-treated carbon fiber felt) as an SPME sorbent for monitoring PAHs in water, rice, and soil samples28. Additionally, carbon quantum dots decorated CFF (CQDs@CFF) composites are used as SPME coatings for the separation of bisphenol A (BPA) from a variety of samples, such as mineral water, bottled water, packaged milk, and thermal paper29. This innovative approach demonstrates the versatility of CFF as an adsorbent material comparable to other carbon-based materials. Furthermore, the adaptability of CFF allows it to be tailored for specific applications by modifying its surface chemistry or incorporating functional groups that enhance its interaction with target analytes. This flexibility makes CFF a valuable tool in environmental monitoring and analytical chemistry, where the detection of contaminants is critical. The unique properties of CFF make for use in microextraction and open new avenues for further research and development in various fields. Its potential as an effective adsorbent underscores the importance of carbon-based materials in advancing extraction methodologies and improving analytical techniques. Herein, we utilized an electrochemical synthesis approach to create PANI on a CFF substrate. The resulting modified fibers possess unique properties such as specific surface area, adsorption capability, functional groups, and tunable charge properties, which make them suitable for the co-extraction of NSAIDs. Finally, PANI@CFF was used to extract and preconcentrate residual NSAIDs and their metabolites from urine and plasma samples. HPLC–UV was employed to separate and quantify them.

Experimental

Reagents and apparatus

Aniline, n-hexane, acetone, hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, sodium hydroxide, and sodium chloride (analytical grade) were purchased from Merck Chemicals Co, (Darmstadt, Germany). All solvents used in this study, including acetonitrile and methanol, were HPLC grade and purchased from Carlo Erba (Valdreuil, France). The CFF was supplied from the Beijing Great Wall Co. Ltd. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Diclofenac (Dic), Ibuprofen (Ibu), Mefenamic acid (Mef) as a model analyte (> 98% purity for each) were provided from Sigma- Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The structure and corresponding physicochemical features of the NSAIDs can be seen in Table S1. The stock standard solutions of NSAIDs were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the compounds in 10 mL of methanol. Stock and working standards were stored at 4 °C and protected from light. Fresh working standard solutions were prepared daily from the stock solutions by sufficient dilution with deionized water.

The study on the synthesis of PANI coating on CFF was performed via aniline electro-polymerization using a three-electrode electrochemical cell including saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE), platinum wire as the counter electrode (Azar Electrode, Iran) and CFF as the working electrode. The surface morphology of the fibers was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, MIRA III, Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV with magnifications in the range of 1000–50,000 × . In addition, the elemental composition was analyzed by an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscope (EDS, MIRA II SAMX detector, France) attached to the FESEM. The functional groups and/or chemical bonds of the sorbents were identified using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Bruker VERTEX 22, Germany) in the range of 500–4000 cm⁻1, with a resolution of 4 cm⁻1 and averaging 32 scans. The samples were analyzed in the form of KBr pellets. At room temperature, powder X-ray diffraction was performed following the Bragg–Brentano geometry (θ–2θ), Philips X’pert 1710 diffractometer (Netherlands) with Cu − Kα radiation (α = 1.54056 Å). Separation and identification of analytes were performed using a JASCO (Japan) HPLC system. The HSS 2000 software (JASCO) with LC-Net II/ADC interface and BORWIN processor (version 1.50) controlled the chromatograph. The HPLC was connected to an ODS UV–Vis detector (K-2600, Knauer) from Germany and consisted of an isocratic pump (PU-158), a Rheodyne 77225i injector, a 20 μL stainless steel sample ring (Rheodyne, Cota, CA-15 mm- spectrophones), and a column (mmA spectrophones). ID, 5 μm) from MZ-Analysentechnik, Germany. A mixture of phosphate buffer (0.02 M, pH = 5) and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) that flowed isocratic at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min was the mobile phase. Detection of NSAIDs was performed at 210 nm wavelength. Sonication was performed by a FALC ultrasonic device model LBS2 (Italy), and pH measurement of the solutions was performed with a Metrom pH meter model 744 (Switzerland).

Growth of PANI on the CFF nanofibers skeleton

PANI was synthesized via an electrochemical synthesis method in a one-step process on CFF, similar to the previously published procedure30. Key operational parameters, including acid type, monomer concentration, and stirring speed, were systematically investigated and optimized to achieve improved performance (see Section “Conditions optimization” for details). To prepare PANI@CFF, the surface of CFF was first activated by cyclic voltammetry to create more hydrophilicity. This operation was performed in the potentialrange − 0.5–1.8 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s in 100 mL 0.1 M H2SO4 for several cycles. Then, the activated CFF was placed in an aniline solution of 0.1 M and scanned in two potential ranges: I) from− 0.2 V to 0.9 V at a scan rate of 2 mV/s for two cycles for effective starting of electro-polymerization, and II) from− 0.2 V to 0.7 V at a scan rate of 5 mV/s for another 18 cycles for the polymer film growing. Finally, the CFF was washed with distilled water and dried in an oven at 100 °C for 3 h to be used as a sorbent in the SPME method.

Preparation of real samples

Drug-free human plasma samples were obtained from the Blood Transfusion Organization (Tabriz, Iran). 3 mL of acetonitrile was mixed with 3 mL of the plasma sample and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Then, it was vortexed vigorously for 15 min and centrifuged at 4500 rpm (10 min)31. The collected 3 mL of supernatant was diluted tenfold with disodium hydrogen phosphate buffer (pH = 4). Urine samples were collected from a 43-year-old female volunteer who had taken oral doses of a 400 mg ibuprofen tablet and a 250 mg mefenamic acid capsule. Urine samples were collected once before drug administration. Subsequently, urine samples were collected from the volunteers for 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 24 h after drug administration. Any suspended solids in the samples were removed by centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 10 min, and the samples were stored at − 20 °C. Finally, 3 mL of the urine sample was diluted 10 times with disodium hydrogen phosphate buffer (pH = 4) before the assay.

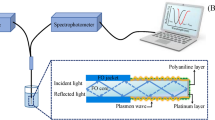

SPME procedure

A daily preparation of a 20 mL working standard solution of NSAIDs was conducted, achieving a concentration of 20 µg/L from a stock solution of 100 µg/L. Subsequently, the PANI@CFF adsorbent was completely immersed in the working solution (pH = 4) for 10 min. After removing the adsorbent from the sample solution, it was placed in a microtube containing 700 μL of methanol as desorption solvent. The methanol was then evaporated under a gentle nitrogen stream. Subsequently, 40 µL of fresh methanol solvent was added to redissolve the target analytes. Finally, 25.0 μL of this solution was injected into the HPLC–UV system for analysis of the analytes. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the proposed method. Real samples, including plasma and urine, were analyzed using this method to determine the content of NSAIDs. The proposed method was also validated by examining relative recovery experiments.

Statement

All experiments and methods conducted throughout this study strictly adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations. In addition, it is confirmed that written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Furthermore, it is declared that all research and methods involving human subjects were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Tabriz, Iran, under Ethical ID. IR.AZARUNIV.REC.1404.015, granted on May 7th, 2021. Before their participation, the volunteers received comprehensive information about the experimental aspects of the study. They were assured of anonymity in the experimental process and also the publication of results exclusively for scientific purposes. Since written informed consent was obtained from all participants, a waiver of informed consent was not required.

Results and discussion

Choice of the best sorbent

Developing new sorbent materials for thin film SPME is of great importance to achieve high extraction efficiency and selectivity. Pristine CFF, acid-treated CFF, and PANI@CFF sorbents were evaluated and compared to select the most suitable sorbent for the SPME process for simultaneous separation and preconcentration of NSAIDs analytes. As seen in Fig. 2, the PANI@CFF sorbent showed the highest extraction performance. The combination of PANI thin film with the AT-CFF represents a synergistic effect in the extraction process. This may be due to the effective π-π and acid–base interactions between the sorbent and NSAIDs. The number of adsorptive sites may also be increased when the surface of AT-CFF fibers is coated with polymeric nanoparticles, providing a more suitable platform for the extraction process.

Characterization of SPME sorbent

The FTIR spectra of the adsorbents (Fig. 3A), including the original CFF (blue curve) and AT-CFF (yellow curve), showed specific peaks in the FTIR spectrum of the PANI@CFF adsorbent (green curve). In the IR range, a peak attributed to the stretching vibrations of the C = C bond in the six-membered ring structures of both the original sample and AT-CFF was observed at 957 cm−1. Also, a distinct band at 2087 cm−1 was observed, which is related to the C-H bond stretching vibration in the methyl (–CH3) and methylene (–CH2) groups. It seems that the small and light alkoxy groups are removed under acidic conditions during the hydrolysis process and can be replaced by hydroxyl and carbonyl functional groups. The presence of hydroxyl (–OH) groups was indicated by the O–H bond stretching vibration. In the textures of both samples, bands at 3333 and 3414 cm−1 are observed, indicating the presence of –OH groups. The absorption band at 1649 cm⁻1 is also attributed to the stretching vibration of the C = O double bond in the carbonyl groups. For the AT − CFF sample, bands at around 1303 cm⁻1 are observed, which are related to the stretching vibration of the C − O bond in the ester functional groups. These assignments are consistent with previous reports on carbon-based materials28,29.

FT − IR (A) spectra of pristine CFF (blue curve), AT-CFF (pink curve), PANI@CFF (green curve); (B) XRD pattern of pristine CFF (green curve) and PANI@CFF (blue curve); FE − SEM images of different sorbent types: Pristine CFF(C), AT-CFF (D), and PANI@CFF with different magnifications (E1-E4); EDX spectra of PANI@CFF (D), and the inset to this Figure shows elemental mapping.

Following in the green curve, adsorption peaks at 1590–1600 cm−1 are associated with the C = C stretching vibrations of benzoid and quinoid rings in PANI chains, corroborating the existence of a protonated emeraldine state (conducting state) in PANI. The peaks at 1300–1320 cm−1 are ascribed to the C–N stretching vibrations of the benzene ring and the C = N stretching vibrations of the quinoid ring. Other peaks at 1100–1150 cm−1 are attributed to the aromatic C–H deformation vibrations32,33

XRD analysis of both bare carbon fiber felt and PANI-coated CFF reveals distinct peaks at approximately 25.8° and a weak peak near 43°, as illustrated in Fig. 3B. In the case of PANI-coated CFF, additional peaks appeared at 18.8° and 24.0°, corresponding to the (011) and (200) crystal planes of PANI34. Notably, the peak around 25° is attributed to the characteristic emeraldine salt form of PANI35. Additional small peaks at angles such as 32–38° may be related to crystallization processes within the polymer matrix.

FE-SEM and EDX analyses were performed to characterize the morphological features and elemental composition of PANI-CFF. The FE-SEM images of pristine CFF and AT-CFF (Fig. 3C, D) reveal a network-like structure with interwoven fibers. Although no major morphological changes are observed, the acidic treatment is likely to introduce subtle surface modifications and chemical activation, which enhance analyte adsorption and lead to better extraction performance than the pristine CFF. Further, acid treatment of CFF may introduce polar functional groups on the carbon fiber surface, which may facilitate the polymerization of PANI and provide additional active sites for adsorption. Figure 3(E1–E4) presents the FE-SEM images of a complex carbon fiber structure completely covered with PANI. The PANI coating not only increases the surface area of the carbon fiber but also creates a porous and nanostructured platform that significantly enhances the adsorption capacity. In these images, PANI can be seen as a thin and uniform film accumulated on the CFF. This coating could provide active and accessible surface sites, enabling interlayer interactions with analytes. The resulting three-dimensional structure increases the availability of active sites, thereby enhancing adsorption and preconcentration efficiency. As shown in Fig. 3(E1–E4), the combination of CFF with PANI produces a porous structure that adopts a nanofibrous morphology. This facilitates the passage of sample solution and solvent through the compact adsorbent and offers a large number of active sites for NSAID extraction via π-π and acid–base interactions, ultimately improving the adsorption efficiency. Consequently, among the three types of CFF investigated, the PANI@CFF adsorbent demonstrates the best performance in adsorption and preconcentration processes due to its unique structure and improved properties.

EDS analysis of the sorbent confirms the presence of the main elements, oxygen (O), carbon (C), and nitrogen (N), indicating successful incorporation of PANI. Elemental mapping (inset to Fig. 3F) shows that nitrogen is distributed homogeneously across the CFF layers, demonstrating a uniform coverage of PANI throughout the sorbent. These findings are consistent with the expected morphology of PANI-coated carbon fibers observed in SEM analysis.

Conditions optimization

This research examines how two groups of parameters influence extraction efficiency: (i) the fiber preparation parameters and (ii) the SPME extraction parameters. Both sets of factors were systematically investigated and optimized in the assay of Ibuprofen (Ibu), Diclofenac (Dic), and Mefenamic acid (Mef). The one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach was employed to optimize these parameters.

Optimization of fiber preparation parameters

During the PANI@CFF fiber fabrication stage, the parameters of acid type and concentration, monomer concentration, and stirring speed were investigated and optimized to achieve the best adsorption performance. The use of an acid as a dopant to protonate the polymer during the fabrication of PANI@CFF fibers is crucial for initiating polymerization, resulting in enhanced conductivity and absorption properties of the fibers. The acids tested at this stage were H₂SO₄, HCl, and HNO₃. Among these, H₂SO₄ was chosen as the best one, which maximizes the absorption efficiency. This enhancement may be due to uniform polymer growth in the presence of H₂SO₄ as a suitable dopant and strong electrostatic interactions with the carboxylate groups of NSAIDs. The effects of the acid type on fiber performance were shown in Fig. S2A.

In order to evaluate the effect of acid concentration on the electrochemical synthesis of PANI@CFF, sulfuric acid solutions of 0.05, 0.10, and 0.20 M were prepared and tested. Among these values, the concentration of 0.1 M H₂SO₄ showed the highest extraction performance (Fig. S2B), and it was selected as the optimized concentration. Sulfuric acid concentrations lower or larger than 0.1 M result in decreased extraction performance. At lower concentrations (0.05 M), the protonation of polyaniline may be incomplete, resulting in a weak electrical conductivity and polymer film growth. On the other hand, higher concentrations (0.2 M) may cause instability in the polymer structure, inhibiting polymer growth. In addition to determining the optimal monomer concentration, aniline solutions with concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, and 0.5 M were prepared and subjected to the same electropolymerization conditions. Then, the resulting adsorbents were applied to extraction experiments. The desired performance was observed for a 0.1 M aniline solution, which was considered the optimum value. Lower or higher monomer concentrations result in poor extraction efficiency (Fig. S2C ). These observations may be due to the insufficient thickness of the PANI film formed at low monomer concentrations, and an unstructured/unstable polymer film was formed at high concentrations under acute conditions, where the time scale was not enough to create a regular and stabilized PANI film.

Solution stirring rate during electropolymerization is one of the effective experimental factors that should be optimized. The effect of several stirring speeds of the electrolyte solution (0, 200, 300, 400, 500, and 700 rpm) was investigated on the electrochemical synthesis of PANI@CFF and its extraction performance (Fig. S2D). At moderate stirring speeds, the highest extraction performance was observed, while for low and high stirring speeds, the extraction performance was depressed. It seems that at low stirring conditions, the film formation growth is restricted by monomer mass transfer limitations, providing a thin polymer film thickness, leading to a low extraction efficiency. On the other hand, high stirring conditions reduce restrictions on mass transfer and increase film formation rate, and form a relatively unstable polymer film. It means that the polymeric material could not be stabilized on the CFF surface in high polymerization conditions. At moderate stirring rates, the influencing factors are balanced, and a polymeric film was formed with suitable thickness and stability. Therefore, a stirring speed of 300 RPM was selected as the optimum value.

Optimization of SPME extraction parameters

To achieve the highest extraction efficiency, optimization of the fruitful parameters in thin film SPME will be necessary. This research (illustrated in detail in Fig. 4) examines how various factors affect the extraction efficiency and need to be optimized in the assay of Ibuprofen (Ibu), Diclofenac (Dic), and Mefenamic acid (Mef). Influencing factors include extraction time, desorption solvent type, and its volume, desorption time, pH, and salt percentage (%), which should be optimized to extract the maximum amount of target analytes36. In this study, different extraction times ranging from 2 to 25 min were investigated. As can be seen in Fig. 4A, equilibrium was reached within 10 min, indicating the fast adsorption kinetics of NSAIDs onto PANI@CFF sorbent.

A key step in all SPME systems is the desorption of analytes from the adsorbent surface. The appropriate elution solvent should be strong enough to remove the analyte completely or as much as possible from the adsorbent coating37. In this study, methanol, DMSO, acetonitrile, and DMF were tested as desorption solvents. Based on the results (Fig. 4B) obtained, methanol was selected as the appropriate elution solvent to obtain the highest signal intensity.

Although using a large volume of desorption solvent can enhance the efficiency of the desorption process, the excessive use of desorption solvent has no positive effect on improving the preconcentration yield, and is not in compliance with green chemistry requirements. So, the desorption solvent needs to be optimized. So, the utilized volumes of methanol varied from 300 to 2000 µL. The extraction efficiency increases from 300 to 700 µL and stabilizes at higher values. Therefore, 700 µL was selected as the optimal volume of the desorption solvent (Fig. 4C).

To desorb all analytes from the sorbent surfaces, the duration of the desorption process can significantly impact the efficient release of analytes from the sorbent surface38. The effect of desorption duration on extraction efficiency was assessed for periods ranging from 2 to 15 min, and the results are presented in Fig. 4D. Accordingly, no significant increase in the desorption efficiency of the target analytes is observed after 2 min. Therefore, it can be concluded that the removal of analytes from the sorbent surface is fast. So, the optimal desorption time was considered to be 2 min, and this time was used in subsequent experiments.

The pH level plays an important role in the extraction process of NSAIDs39. The solution pH values were considered in the range 3 − 11, and based on the results, pH 4 showed the most extraction efficiency (see Fig. 4E). This finding is consistent with the pKa values of the analytes (see Table 1). In an acidic medium, the drugs are mainly in their molecular form, allowing them to interact more effectively with the PANI@CFF extracting phase. Finally, another experimental factor affecting the extraction efficiency is the presence of various salts in the sample solution. In general, the solubility of nonpolar organic compounds in water decreases with increasing ionic strength of the solution, leading to better extraction according to the well-known process of “salt effect”. Similarly, the presence of salt affects the diffusion coefficient of the analyte and its distribution between the sample solution and the PANI@CFF, leading to an increase in the viscosity of the solution. On the other hand, the salt or its constituent ions may be immobilized on the PANI@CFF structure and disrupt the extraction process. The extraction results will show the result of these various effects. In this study, the extraction process was carried out in the absence and presence of NaCl with different amounts between 0.0 and 20.0% (w/v). The extraction efficiency decreased significantly with changing the NaCl concentration between 0.0 and 20%, and then remained constant for higher NaCl concentrations. According to Fig. 4F, the highest extraction efficiency was obtained in the absence of NaCl (0.0%; w/v). Therefore, all experiments for the preconcentration of NSAIDs were performed without the addition of salt.

Evaluation of adsorption capacity

Kinetic study of the adsorption process

To evaluate the kinetics of thetarget analytes extraction process on the proposed adsorbent, the rate constants and regression coefficients as kinetic data were calculated and fitted in pseudo-first and pseudo-second order models. According to the results presented in Table S2, the adsorption of NSAIDs by the proposed PANI@CFF sorbent obeyed the pseudo-second order model.

Equilibrium studies of the adsorption process

To evaluate adsorption equilibrium, 25 mg of the adsorbent was added to 100 mL of sample solutions at pH 4 with concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 mg L⁻1. After stirring the mixtures for 10 min at 298 K, the sorbent was separated, the remaining analytes were quantified, and the adsorption capacity per gram of adsorbent (qₑ) was determined. Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were used to fit the data to describe the adsorption process. Equations (1, 2) express the basic form of the Langmuir isotherm and its linear form:

where qm is the adsorbent capacity (mg g−1) and Ka (mg−1) is the Langmuir isotherm constant. Also, the basic form is given by Eqs. (3) and (4):

where KF ((mg g−1)(1/mg)1/n) is the Freundlich isotherm constant.

The amount of analyte adsorbed per gram of adsorbent (qₑ) was also calculated. The experimental data were fitted with the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms to describe the adsorption process. Equations (1) and (2) present the basic and linear forms of the Langmuir isotherm, where qₘ is the adsorption capacity (mg/g) and Kₐ is the Langmuir constant (L mg/g). Similarly, the basic form of the Freundlich isotherm is expressed by Eqs. (3) and (4), where KF is the Freundlich constant ((mg/g)(1/mg)1⁄ⁿ). According to the obtained results summarized in Table S3, it is shown that the adsorption processes of NADSI follow the Langmuir isotherm, in which the adsorbed molecules form a monolayer coating on the adsorbent surface, all adsorption sites are equivalent, and each site interacts with one adsorbed molecule.

Extraction mechanism

The predicted adsorption mechanism has been schematically presented (Fig.S1). It illustrates π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions between protonated PANI (–NH⁺) and the carboxylate groups of NSAIDs (ibuprofen, diclofenac, and mefenamic acid). Because polyaniline contains aromatic benzene rings along its backbone, π–π stacking interactions with the aromatic moieties of NSAIDs are also expected, complementing hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. Additionally, the protonation of PANI is pH-dependent, with the –NH groups becoming increasingly protonated under acidic conditions, enhancing electrostatic attraction toward the anionic carboxylate groups of NSAIDs. Conversely, at higher pH, deprotonation reduces this contribution, making π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding the dominant.

Method validation

Analytical figures of merit such as coefficient of determination (R2), relative standard deviations (RSDs%) (intra-day, inter-day, and film-to-film), linear dynamic ranges (LDRs), limits of quantification (LOQs), limits of detection (LODs), extraction recoveries (ERs%), and preconcentration factors (PFs) were considered as indicators to judge the analytical efficiency of the thin film SPME-HPLC–UV technique. The results summarized in Table 1 were obtained under optimal conditions in two media, ultrapure water and plasma samples. For Ibu, Dic, and Mef, the wide LDRs ranges (R2 ≥ 0.995) were attained in the range of 0.05–1000.0 and 0.2–1000.0 µg L−1 for the water and plasma samples, respectively. Consequently, the LOD values were calculated as 0.02–0.03 µg L−1 and 0.03–0.07 µg L−1 in water and plasma samples, respectively. The limit of quantification (LOQ) values for water and plasma samples were determined to be 0.05–0.1 and 0.1–0.2 µg L−1, respectively. Repeatability in terms of intra-day, inter-day, and film-to-film operation was calculated with RSD values being ≤ 4.3%, 4.9%, and 5.7%, respectively. The ERs% and PFs in water samples ranged from 63.1% to 91.1% and 677 to 821, respectively. In plasma samples, the corresponding values were 47.3% to 63.8% for ERs% and 458 to 691 for PFs.

Analysis of real samples

The effectiveness of the proposed adsorbent (PANI@CFF) for the SPME method should be evaluated by analyzing samples with complex matrices. For this purpose, urine and plasma samples were selected. Urine samples were analyzed before and 4 h after drug administration with three-level analyte concentration. Plasma samples were analyzed after preparation (see section preparation of real samples), both before and after spiking with three-level analyte concentrations (Fig. 5). The values of RSD% as precision and relative recovery (RRs%) as accuracy of the proposed method were calculated for three replicate measurements (Table 2). The time of drug excretion from the body fluids was monitored (24 h) by drawing chromatograms at different times after drug administration. Figure 5A shows chromatograms obtained by using PANI@CFF preconcentration sorbent for urine samples and after different elapsed times of drug administration. As can be seen, the highest drug levels in urine were observed after 4 h, and it was exerted during a 24 h period. Monitoring of target drugs in drug-free urine samples (no drug administration), and 3-level spiked urine samples (Fig. 5B) clearly illustrate that the analytical signal corresponds to the spiked values. Figure 5C was obtained for a similar experiment performed on a urine sample collected after 4 h of drug administration. Analytical signals related to the target analytes appeared for this urine sample and increased after spiking. Finally, Plasma sample analysis before and after the addition of three concentrations of analytes is displayed in Fig. 5. Additionally, the relative recovery (RR) was determined using the Eq. (5):

where Creal is the concentration of the analyte in the real sample, Cadded is the concentration of the analyte spiked into the real sample, and Cfound is the concentration of the analyte after spiking a known amount of standard in the real sample. The experimental RR values for a variety of target analytes were calculated to be in the range of 80.0–113.4%, as presented in Table 2. These results confirm the lack of matrix effect on the analytical data, indicating the accuracy of the proposed protocol.

Shows (A) chromatograms after target drugs administration recorded for 24-h collecting and monitoring of urine samples; (B, C) Target drugs monitoring in non-spiked and 3-level spiked urine samples without drug administration (B), and after 4 h of drugs administration (C). Plasma sample analysis before and after target analytes spiking at 3 concentration levels (D). All samples were preconcentrated using PANI@CFF sorbent.

Additionally, the Matrix Effect (ME%) was determined using the Eq. (6):

where As and An are the raw data of peak areas from spiked and non-spiked real samples of any analytes, and Aw is the same response but in aqueous solution. The calculated ME% is tabulated in Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed strategy (SPME-HPLC–UV) of NSAIDs with other published methods

This study highlights several advantages of the PANI@CFF sorbent, including a simple and rapid one-step electrochemical fabrication method, durability, low cost, and an extended shelf life. Table 3 summarizes the articles in which NSAIDs were extracted and analyzed using various methods. As shown, the SPME-HPLC–UV method either has a faster extraction time or performs comparably to other methods. This approach requires no highly sensitive analytical detectors like mass spectrometry (MS) and avoids consecutive extractions. Instead, it achieves low limits of detection (LODs), a wide linear range, and the ability to extract from samples with complex matrices, all while maintaining acceptable relative standard deviations (RSDs). Notable advantages of this method include a short extraction time of 10 min, minimal requirement for organic solvent (only 700.0 μL), and a small amount of sorbent, which together form a thin yet flexible three-dimensional (3D) material layer. These features contribute to the method’s superiority over others.

Conclusions

Using a simple and one-step electrochemical synthesis method, a PANI film was successfully synthesized on AT-CFF. Considering the unique characteristics of this sorbent, including its porous structure and high conductivity, which lead to the creation and emergence of multiple adsorption sites for the extraction of NSAIDs. These findings suggest that the combination of PANI and CFF properties can enhance the extraction and preconcentration efficiency of these drugs. In addition to low energy consumption, small sample requirement, minimal waste generation, and operational simplicity, employing this adsorbent in the method rendered it a green and sustainable approach. Furthermore, it demonstrated excellent performance in extracting and quantifying NSAIDs from real samples, offering advantages such as a low detection limit (less than 0.03 µg L⁻1), a wide linear range (0.05–1000 µg L⁻1), and a good recovery rate (80.0–113.4%).Overall, the results of this research demonstrate the high potential of PANI@CFF adsorbent for environmental applications and chemical analysis, and contribute to the development of new and efficient methods for the measurement of NSAIDs.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Nejabati, F. & Ebrahimzadeh, H. A novel sorbent based on electrospun for electrically-assisted solid phase microextraction of six non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, followed by quantitation with HPLC-UV in human plasma samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 1287, 341839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2023.341839 (2024).

He, X. Q., Cui, Y. Y., Lin, X. H. & Yang, C. X. Fabrication of polyethyleneimine modified magnetic microporous organic network nanosphere for efficient enrichment ofnon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs from wastewater samples prior to HPLC-UV analysis. Talanta 233, 122471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122471 (2021).

Rodriguez-Saldana, V., Castro-Garcia, C., Rodriguez-Maese, R. & Leal-Quezada, L. O. Advances in the extraction methods for the environmental analysis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2023.117409 (2023).

Bindu, S., Mazumder, S. & Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 180, 114147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114147 (2020).

Lakshmi, S. D., Geetha, B. V. & Vibha, M. From prescription to pollution: The ecological consequences of NSAIDs in aquatic ecosystems. Toxicol Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2024.101775 (2024).

Banerjee, S. & Maric, F. Mitigating the environmental impact of NSAIDs—Physiotherapy as a contribution to one Health and the SDGs. Eur. J. Physiother. 25(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2021.1976272 (2023).

Jia, Y. et al. Biotransformation of ibuprofen in biological sludge systems: Investigation of performance and mechanisms. Water Res. 170, 115303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.115303 (2020).

Gao, J., Mfuh, A., Amako, Y. & Woo, C. M. Small molecule interactome mapping by photoaffinity labeling reveals binding site hotspots for the NSAIDs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140(12), 4259–4268. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b11639 (2018).

Arabi, M. et al. Strategies of molecular imprinting-based solid-phase extraction prior to chromatographic analysis. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 128, 115923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2020.115923 (2020).

Arabi, M. et al. Molecular imprinting: Green perspectives and strategies. Adv. Mater. 33(30), 2100543. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202100543 (2021).

Wen, Y. et al. The metal-and covalent-organic frameworks-based molecularly imprinted polymer composites for sample pretreatment. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 178, 117830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2024.117830 (2024).

Zare, F., Ghaedi, M. & Daneshfar, A. Solid phase extraction of antidepressant drugs amitriptyline and nortriptyline from plasma samples using core-shell nanoparticles of the type Fe₃O₄@ZrO₂@N-cetylpyridinium, and their subsequent determination by HPLC with UV detection. Microchim Acta 182, 1893–1902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2020.07.053 (2015).

Barabi, A. et al. Electrochemically synthesized NiFe layered double hydroxide modified Cu (OH)₂ needle-shaped nanoarrays: A novel sorbent for thin-film solid-phase microextraction of antifungal drugs. Anal. Chim. Acta 1131, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2020.07.053 (2020).

Sereshti, H., Karami, F., Nouri, N. & Farahani, A. Electrochemically controlled solid phase microextraction based on a conductive polyaniline-graphene oxide nanocomposite for extraction of tetracyclines in milk and water. J. Sci. Food Agric. 101(6), 2304–2311. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.10851 (2021).

Sowa, I., Wójciak, M., Tyszczuk-Rotko, K., Klepka, T. & Dresler, S. Polyaniline and polyaniline-based materials as sorbents in solid-phase extraction techniques. Materials 15(24), 8881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15248881 (2022).

Zhang, J., Dang, X., Dai, J., Hu, Y. & Chen, H. Simultaneous detection of eight phenols in food contact materials after electrochemical assistance solid-phase microextraction based on amino functionalized carbon nanotube/polypyrrole composite. Anal. Chim. Acta 1183, 338981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2021.338981 (2021).

Poddar, A. K., Patel, S. S. & Patel, H. D. Synthesis, characterization and applications of conductive polymers: A brief review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 32(12), 4616–4641. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.5483 (2021).

Yamini Y, Tajik M, Baharfar M (2022) Cleanup and remediation based on conductive polymers. InConductive Polymers in Analytical Chemistry. ACS 91

Roostaie, A., Haddad, R. & Mohammadiazar, S. Aniline-naphthylamine copolymer as the solid phase microextraction (SPME) fiber coating for the determination of chlorobenzenes by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Anal. Lett. 56(8), 1338–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00032719.2022.2129666 (2023).

Bianchi, C. L., Djellabi, R., Della Pina, C. & Falletta, E. Doped-polyaniline based sorbents for the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and dyes from water: Unravelling the role of synthesis method and doping agent. Chemosphere 286, 131941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131941 (2022).

Marinangeli, A., Chianella, I., Radicchi, E., Maniglio, D. & Bossi, A. M. Molecularly imprinted polymers electrochemical sensing: The effect of inhomogeneous binding sites on the measurements a comparison between imprinted polyaniline versus nanoMIP-Doped polyaniline electrodes for the EIS detection of 17β-Estradiol. ACS Sens. 9(9), 4963–4973. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.4c01787 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Electropolymerization of polyaniline as high-performance binder free electrodes for flexible supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 376, 138037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2021.138037 (2021).

Graves, D. A. et al. Enhanced electrochemical properties of polyaniline (PANI) films electrodeposited on carbon fiber felt (CFF): Influence of monomer/acid ratio and deposition time parameters in energy storage applications. Electrochim. Acta 454, 142388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2023.142388 (2023).

Zhang, W. J. et al. Pseudocapacitive brookite phase vanadium dioxide assembled on carbon fiber felts for flexible supercapacitor with outstanding electrochemical performance. J. Energy Storage 47, 103593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.103593 (2022).

Guo, P. et al. Ultralight carbon fiber felt reinforced monolithic carbon aerogel composites with excellent thermal insulation performance. Carbon 183, 525–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021.07.027 (2021).

Chen, S., Qiu, L. & Cheng, H. M. Carbon-based fibers for advanced electrochemical energy storage devices. Chem. Rev. 120(5), 2811–2878. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00466 (2020).

Peng, L. et al. Degradation of methylisothiazolinone biocide using a carbon fiber felt-based flow-through electrode system (FES) via anodic oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 384, 123239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123239 (2020).

Sheikhi, T., Razmi, H. & Mohammadiazar, S. Carbon fiber felt as a novel sorbent for the easy detection of environmental pollutants: Application to the analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Food Compos. Anal. 142, 107416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2025.107416 (2025).

Sheikhi, T., Razmi, H. & Mohammadiazar, S. In situ synthesis of carbon quantum dots on carbon felt fibers as a new solid-phase microextraction sorbent for chromatographic analysis of bisphenol A. Microchem. J. 204, 110842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2024.110842 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Anthraquinone (AQS)/polyaniline (PANI) modified carbon felt (CF) cathode for selective H₂O₂ generation and efficient pollutant removal in electro-Fenton. J. Environ. Manage. 304, 114315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114315 (2022).

Khodayari, P., Jalilian, N., Ebrahimzadeh, H. & Amini, S. Trace-level monitoring of anti-cancer drug residues in wastewater and biological samples by thin-film solid-phase micro-extraction using electrospun polyfam/Co-MOF-74 composite nanofibers prior to liquid chromatography analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 1655, 462484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462484 (2021).

Wickramasinghe, D., Oh, J. M., McGraw, S., Senecal, K. & Chow, K. F. Electrochemical effects of depositing iridium oxide nanoparticles onto conductive woven and nonwoven flexible substrates. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2(1), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.8b01404 (2018).

Tokgoz, S. R., Firat, Y. E., Akkurt, N., Pat, S. & Peksoz, A. Energy storage and semiconductingproperties of polyaniline/graphene oxide hybrid electrodes synthesized by one-pot electrochemical method. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 15(135), 106077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2021.106077 (2021).

El-Sawy, A. M., Moa’mena, H. A., Darweesh, M. A. & Salahuddin, N. A. Synthesis of modified PANI/CQDs nanocomposite by dimethylglyoxime for removal of Ni(II) from aqueous solution. Surf. Interfaces 26, 101392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101392 (2021).

Palaniappan, S. & Srinivas, P. Nano fiber polyaniline containing long chain and small molecule dopants and carbon composites for supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 95, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2013.02.040 (2013).

Alipour, F., Raoof, J. B. & Ghani, M. Determination of quercetin via thin film microextraction using the in situ growth of Co–Al-layered double hydroxide nanosheets on an electrochemically anodized aluminum substrate followed by HPLC. Anal. Methods 12(6), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9AY02528F (2020).

Zandian, F. K., Balalaie, S., Amiri, K. & Bagheri, H. Mesoporous organosilicas with highly-content tyrosine framework as extractive phases for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in aquatic media. Anal. Chim. Acta 1290, 342206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2024.342206 (2024).

Jõul, P., Vaher, M. & Kuhtinskaja, M. Carbon aerogel-based solid-phase microextraction coating for the analysis of organophosphorus pesticides. Anal. Methods 13(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0AY02002H (2021).

Moradi, N., Soufi, G., Kabir, A., Karimi, M. & Bagheri, H. Polyester fabric-based nano copper-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes sorbent for thin film extraction of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Anal. Chim. Acta 1270, 341461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2023.341461 (2023).

Yu, Q. W. et al. Automated analysis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in human plasma and water samples by in-tube solid-phase microextraction coupled to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry based on a poly (4-vinylpyridine-co-ethylene dimethacrylate) monolith. Anal. Methods 4(6), 1538–1545. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1AY05412K (2011).

Li, N., Chen, J.& Shi, Y. P. Magnetic polyethyleneimine functionalized reduced graphene oxide as a novel magnetic sorbent for the separation of polar non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in waters. Talanta 191, 526–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2018.09.006 (2019).

Abdi, M. R. & Sarlak, N. Utilization of CoFe₂O₄@HKUST-1 for Solid-phase microextraction and HPLC-UV determination of NSAIDs in serum, plasma, and urine samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. Res. 12(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.22036/abcr.2025.488638.2220 (2025).

Amiri, A. & Ghaemi, F. Solid-phase extraction of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in human plasma and water samples using sol–gel-based metal-organic framework coating. J. Chromatogr. A 1648, 462168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462168 (2021).

Shamsadin-Azad, Z., Taher, M. A. & Beitollahi, H. A simple voltammetric method for rapid sensing of daunorubicin in the presence of dacarbazine by graphene oxide/metal–organic framework-235 nanocomposite-modified carbon paste electrode. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 21(10), 2623–2633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-024-03092-w (2024).

Darvishnejad, F., Raoof, J. B. & Ghani, M. In-situ synthesis of nanocubic cobalt oxide@ graphene oxide nanocomposite reinforced hollow fiber-solid phase microextraction for enrichment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs from human urine prior to their quantification via high-performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1641, 461984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2021.461984 (2021).

Liu, H., Fan, H., Dang, S., Li, M. & Yu, H. A Zr-MOF@ GO-coated fiber with high specific surface areas for efficient, green, long-life solid-phase microextraction of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in water. Chromatographia 83, 1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10337-020-03930-y (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University for the support of the project.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tahereh Sheikhi: Performed the measurements, processed the experimental data, drafted the manuscript and designed the figures, wrote the manuscript, and performed the final revision with input from all authors. Habib Razmi: Devised the project, the main conceptual ideas, and the proof outline. Sirwan Mohammadiazar: Contributed to the planning and supervised the work, aided in interpreting the results, and worked on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikhi, T., Razmi, H. & Mohammadiazar, S. In situ electro-polymerized polyaniline thin film on highly porous carbon fiber felt for extraction and chromatographic detection of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Sci Rep 16, 280 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25302-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25302-y