Abstract

Pre-performance emotions (PPE) are complex and multifaceted, shaped by a dynamic interplay of internal and external stimuli. Most prior research has focused on univalent negative PPE, particularly music performance anxiety (MPA). This study contributes by examining the complexity of PPE states and adopting a mixed-emotion perspective. Its aims were to: (a) identify the categories, sources, and complexity of PPE in solo performance among young adult musicians; (b) explain the functional significance of PPE profiles for performance quality and satisfaction; and (c) compare PPE profiles in relation to situational factors (self-efficacy beliefs about emotion regulation and performance skills) and dispositional factors (emotional awareness and regulation, MPA vulnerability). Before a solo performance, 124 students from the Polish Music Academy used the Emomix electronic form to assess their self-efficacy beliefs and describe their emotions. Following the performance, subjective and objective ratings of performance quality were collected. Dispositional variables were measured using the Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale, the Brief-COPE, and the Kenny-MPAI inventories. The findings align with previous research on PPE in adolescents and demonstrate its multifaceted nature. Participants reported an average of eight emotions, with hope, curiosity, and fear being the most frequently mentioned. Content analysis identified 34 sources of PPE. Four emotional clusters were extracted as follows: Epistemic emotions and joy, Curiosity and positive emotions, Fear and hope, Shame and negative emotions. The highest self-efficacy and performance satisfaction scores were observed in the first two clusters. Participants exhibited moderate MPA vulnerability, comparable emotional regulation skills, and moderate-to-high performance quality ratings. Considering these balanced baseline characteristics, differences in performance satisfaction appear to be driven more by situational variables than by the dispositional variables assessed in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Observations from psychological counselling for musicians indicate that when they assess their satisfaction with a performance, they consider both the performance quality and their emotional well-being prior to the performance. The occurrence of negative emotions before going on stage followed by a high-level performance, raises important questions about the complex relationship between pre-performance emotions and artistic excellence1,2. The aim of this article is to address these questions by analysing the variety of musicians’ pre-performance emotional states and cognitions, comparing individuals with different emotional profiles and dispositional factors such as vulnerability to music performance anxiety and emotion regulation skills in terms of performance quality and satisfaction.

Variety and dynamic of pre-performance emotions

Pre-performance emotions (PPE) are often complex and multifaceted, shaped by a dynamic interplay of internal and external stimuli3,4. Musicians may experience anxiety, excitement, and hope - emotions that interact to define their psychological state just before going on stage. This emotional complexity aligns with Gross’s modal model of emotion and his process model of emotion regulation5, which provide a useful theoretical framework for understanding the stages of emotional experience and regulation strategies. According to Gross’s model, the emotional process begins with a triggering situation – either real or imagined – that individuals appraise cognitively in relation to their goals. This appraisal elicits an emotional response involving physiological, behavioural, and cognitive components. Importantly, this emotional reaction itself becomes part of a new psychological situation, creating a dynamic cycle of emotions influenced by ongoing attention and interpretation. Although the present study does not directly test Gross’s model or its specific regulatory pathways, it draws on this framework to interpret the diversity of pre-performance emotional experiences, especially in relation to their cognitive aspects. The live performance setting may evoke primary emotions that arise instinctively (e.g. fear, joy) and/or more cognitively saturated secondary emotions (e.g. courage, hope)6,7,8, including self-conscious emotions9 (e.g. pride, shame), and epistemic emotions (e.g. curiosity, surprise)10. These emotions can shift rapidly depending on the performer’s attentional focus and cognitive appraisals5,11, and can be experienced by musicians as a mixture of emotions. Research on mixed emotions, defined as “the co-occurrence of any two or more same-valence or opposite-valence emotions"12, highlights different ways of experiencing these states in significant life situations: sequentially one after another, simultaneously with one emotion dominant and the other weak, or with both emotions equally intense13. Experiencing heterogeneous feelings enhances attentional engagement and enables the processing of affective stimuli in relation to one’s knowledge of self and world, positively affecting well-being14–16 and physical health17. By applying a mixed-emotion approach, this study seeks to identify components of musicians’ pre-performance emotional states and to explore the functional meaning of their configuration for performance achievement.

Structure of PPE and performance-related beliefs, performance quality and satisfaction

The prevalence of articles on univalent negative PPE, especially music performance anxiety (MPA)2,18 highlights the field’s predominant focus. Opportunities to examine the link between successful performance and positive emotions (such as flow19,20, performance boost21, joy and self-confidence18,22,23) remain relatively less examined.

A few studies have examined both positive and negative emotions using the Strong Experience with Music (SEM) system24. The results show co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions, but the emotions of listeners and performers are not considered separately25. Using the same methodology, Lamont22 identified four emotional pathways for performers’ well-being during strong music performing experiences. Two positive emotion groups were based on engagement with others and personal growth through music, while two negative-to-positive pathways showed emotional shifts from performance anxiety to relaxation, enjoyment, and confidence. Unfortunately, the analyses remain at the level of valence rather than capturing the diversity of emotions.

To date, only two studies have been conducted in which a mixed-emotions approach allowed analysis of the structure and complexity of musicians’ PPE states26,27. The studies - one investigating the role of different pre-performance emotional experiences in the quality of solo performances among middle adolescents26, the other linking PPE in younger musicians with beliefs related to MPA - deserve elaboration, as they form the basis of my own study27.

In a first cited study26 just before a school concert 94 students aged 15–18 completed the UMACL University Mood Adjective Checklist. After the concert, the performance quality was evaluated using music teachers’ ratings (Polish education standard 25-point scale) and a subjective level of performers’ satisfaction measures (10-point scale). The dominating result was sadness, with over 80% of participants reporting depression and gloom. However, over 70% of the students marked adjectives describing positive emotions: bright, optimistic and active, suggesting a counterbalancing positive mood and energy. To understand the structural relationship between different emotional categories, a cluster analysis was performed. The results revealed six emotional profiles: from negative (High MPA-exhaustion, marked by anxiety and helplessness), through mixed (Moderate MPA, Calm, Impatience-Mixed emotions, Joy with background fatigue), to positive (Excitement, marked by optimism, happiness, and satisfaction).

These results highlight the functional importance of positive and mixed emotional profiles. The highest levels of self-reported performance quality and satisfaction were observed in the Excitement profile (marked by a high level of positive emotions) and the Impatience-Mixed emotions profile (characterised by high levels of positive emotions, anxiety, and impatience). According to teacher evaluations, the highest performance quality was associated with the Excitement profile and the Joy with background fatigue profile (showing medium levels of all emotions, with a predominance of satisfaction and fatigue).

The study of the younger musicians (9–12)27 examined the link between PPE and beliefs related to MPA. Emotions were elicited with a guided imagery induction, in which 222 musicians recalled their most recent concert memory. They described their emotions from the list of 18 emotions and answered three questions measuring MPA utility beliefs, MPA regulation beliefs, and audience attitude beliefs. Young musicians most often chose the terms insecure, uptight (over 60% of respondents) and worried, afraid (over 45%) to describe their pre-performance state. At the same time, about 30% of respondents chose positive emotions (confident, brave, calm). The results of the cluster analysis revealed five emotional profiles, ranging from negative emotions of fear and sadness (High MPA), through a mixture of positive and negative emotions (Moderate MPA, Hesitation, Ambivalence), to positive emotions of confidence, courage and happiness (Composure-Confidence). Beliefs that MPA has a negative impact on performance, beliefs of inefficiency in managing MPA, and perceived audience pressure rather than support were associated with High and Moderate MPA profiles. Interestingly, positive beliefs were associated with both positive and mixed emotional profiles.

Two studies cited above show a continuum of pre-performance emotional states and provide evidence that the pre-performance emotional experience has a mixed and complex structure. One of them26 highlights the benefits of experiencing positive and mixed emotions for performance quality and satisfaction. Further research will expand the developmental perspective by including a new age group – young adult musicians. It is also worth considering other explanatory variables.

Key dispositional and situational variables related to musician’s pre-performance emotional state

The emotions experienced during a performance are also influenced by biologically determined emotional traits (e.g., anxiety vulnerability), as well as the self-efficacy and emotion regulation developed throughout life28,29. A possible vulnerability affecting a musician’s well-being onstage is music performance anxiety (MPA). This is defined as an excessively intense, persistent anxiety reaction occurring in front of an audience, interfering with satisfactory performance, and accompanied by physiological, cognitive and behavioural features30. Research findings consistently show three higher-order factors contributing to MPA vulnerability31: the early relationship context (linked to biology and early social experiences); psychological vulnerability (related to life experiences including negative self-concept, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, depressed mood and difficult parent relationships); and proximal performance concerns (related to somatic anxiety, negative cognition about performance, and ability to function emotionally). Interestingly, MPA vulnerability does not always correlate with musicians’ onstage emotions32, indicating a possible mediatory role for emotion regulation skills.

Recognising and managing emotions improve performance quality for musicians, in everyday practice33 and onstage22,28. Higher emotional awareness enables the precise identification and description of emotional states with discrete vocabulary that captures their complexity34. Emotional awareness develops gradually, from awareness of bodily sensations and simple response tendencies, to recognition of unidimensional emotions, and finally to awareness of secondary and mixed emotions35. Recognising secondary, self-conscious emotions9, or a mixed emotional state (e.g. fear and hope), indicates the highest level of emotional awareness and plays a crucial role in effective emotional regulation36,37. The opportunity to place a more specific focus on musicians in regard to this issue invites valuable exploration.

Effective emotion regulation involves possessing a sophisticated repertoire of emotional strategies, with the skill to use them flexibly - according to the characteristics of the situation, and individual personality traits, conditions, needs, and goals38. In music performance psychology, emotion regulation strategies are primarily studied in connection with MPA. Professional orchestral musicians report the most useful strategies for managing MPA as increased practice (technological), relaxation techniques, cognitive reinterpretation, social support (psychological), and substance use (pharmacological)39. Measuring MPA regulation using the Brief-COPE inventory yielded an unexpected correlation: in advanced music students and professional musicians40, MPA vulnerability was positively linked with accessing both social support and avoidance strategies. It is surprising that MPA vulnerability correlates with social support seeking, since the latter is normally the most common long-term strategy for countering it41. This reading, however, shows how the need for reassurance or positive evaluation from others may be accentuated40. MPA vulnerability correlated negatively with using perspective change strategies, but positively with problem-focused strategies29. Such strategies may be adaptive, when the possibility of controlling the problem is high, but become maladaptive when controllability is low42. Thus, the direction of the relationship between MPA and emotional well-being may depend on performers’ self-efficacy beliefs about their performance and emotion regulation skills43,44.

Self-efficacy (SE) beliefs refer to an individual’s judgements about their abilities to organise and control actions that lead to a desired level of performance45. SE has emerged as the key variable in predicting musicians’ achievements on stage43,44. SE beliefs influence thoughts and feelings that can prevent negative emotions and help a person to remain calm when dealing with challenging tasks45. The results indicate a strong negative correlation between SE and MPA, and their role (positive – SE, negative – MPA) in predicting performance quality46. Because SE is context-sensitive, it should be measured in relation to the characteristics of the specific domain of activity47. Two further factors deserve attention with regard to pre-performance emotions: performance SE beliefs and the emotion regulation SE beliefs. Research by Spahn et al.19 on flow and MPA in solo performance situations indicated a negative relationship between flow and symptoms of MPA, and highlighted the crucial role of performance SE beliefs and MPA regulation SE beliefs in experiencing a positive emotional state of flow.

The above findings highlight the importance of investigating the structure of PPE in relation to key musicians’ SE beliefs, MPA vulnerability and emotion regulation when explaining effective on-stage functioning. The aims of the current research were to:

-

1.

Identify the categories, sources, and complexity of pre-performance emotional states in solo performance conditions in young adult musicians;

-

2.

Explain the functional meaning of different emotional profiles for musical performance quality and level of satisfaction with performance;

-

3.

Compare pre-performance emotional profiles based on dispositional (emotional awareness and emotion regulation abilities, MPA vulnerability) and situational (SE beliefs about emotion regulation and performance skills) factors.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 124 Polish music academy students, aged 18–32 years (M = 22.32, SD = 3.29), 71% in the age group 19–23 years. There were 90 females (73%) and 34 males (27%). The sample included 12% of vocalists and 88% of instrumentalists, comprising string players (25%), pianists (22%), wind players (10%) and players of other instruments (31%). Three-quarters of the research group had been participants in previously published research29, nonetheless, data on situational variables had not previously been analysed. The Pedagogical University of Cracow Institute of Psychology Ethical Committee approved the study design, including all relevant details (approval number 01/6/2022). All parts of the experiment were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Materials

Situational measures

The two cited studies used different scales. One measured mood (UMACL)26, and the other assessed pre-performance emotions expressed in child-friendly language as nine pairs of opposite emotions27. This made it difficult to compare their results and apply the list of emotions to adults. Therefore, I created a new instrument - the Emomix list of emotions - which included the most universal ones6,7,8,9,10: six primary emotions (anger, fear, joy, sadness, disgust, surprise), two self-conscious emotions (pride, shame), two epistemic emotions (curiosity, boredom), and two secondary emotions relevant to the performance situation (hope, courage). Designed to measure musicians’ PPE and SE beliefs, the Emomix electronic form also offers convenience, consistent with the habits of smartphone and tablet users.

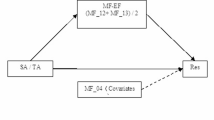

The first task included four open-ended statements about musicians’SE beliefs related to performance, each rated on a 5-point response scale:

1) perceived task difficulty – “I perceive this piece of music to be …” – very easy (1) – very difficult (5);

2) level of preparation belief – “My level of preparation for this piece of music for today is …” – very low (1) – very high (5);

3) belief in performance ability – “I believe that in this situation I will be able to perform as well as I want to…” – strongly disagree (1) – strongly agree (5);

4) belief in emotion regulation – “I believe that in this situation I will be able to manage my performance emotions…” – strongly disagree (1) – strongly agree (5).

The second task consisted of an interactive list of twelve emotional nouns and a neutral state (interpreted as not feeling any specific emotion):

Step 1: participants selected one or more emotions they were actually feeling;

Step 2: they rated the intensity of the selected emotions on a five-point scale, from 1 (very little) to 5 (extremely);

Step 3: they typed the accompanying thoughts. An open-ended prompt – “I felt this emotion because I thought to myself …”- was included to capture qualitative data that complemented the quantitative responses.

This procedure was repeated in a loop, allowing for the measurement of pre-concert emotions over a ten-minute period.

Immediately after the performance, participants were asked to answer two questions:

(1) Self-assessment – “How satisfied are you with your own performance?” rated on a 10-point scale (1 = not at all satisfied, 10 = extremely satisfied).

(2) Emotion rating – “To what extent were the emotions you felt now similar to the emotions experienced while waiting for a real concert setting?” rated on a 10-point scale (1 = not at all similar, 10 = extremely similar).

During a separate meeting, the recordings were rated by experts (academics teaching vocalists and relevant instrumentalists) using a standard 25-point scale total score employed in Polish music education.

Dispositional measures

The Polish version of the revised Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory31,48 was used to measure MPA vulnerability. Forty items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with higher scores representing higher performance anxiety (total score). The scale has three subscales: proximal performance concerns, psychological vulnerability, and early parental relationship context. The K-MPAI-R has high internal (Cronbach’s alpha .89) and test-retest reliability, as well as cross-cultural validity49.

The Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale35,50 is a written, qualitative, projective instrument for describing the anticipated emotions of the self and another person in each of 20 scenes. The scoring criteria make it possible to assess the degree of differentiation and integration of words describing emotions (total score). The modified version of LEAS used in the research contained ten scenes related to music performance and had satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s alpha .7129). The possible score range is 0–50 points, with higher scores indicating better emotion recognition skills.

The Brief-COPE inventory51,52 was used to measure emotion management skills. It contains 28 statements representing 14 coping strategies. Although the scale originates in stress research, it offers a broader assessment of regulatory flexibility than existing Polish tools, which typically cover only three to five strategies. It includes several strategies previously shown to be important in managing MPA29,40,41. Items are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (I don’t do this at all) to 3 (I do this a lot). The Polish version yielded satisfactory psychometric parameters (Cronbach’s alpha for each scale .62-.8952). The results can be grouped into five higher-order strategy groups: problem orientation, support seeking, perspective change, emotional release, and resignation (Cronbach’s alpha for each scale .66-.8229).

Procedure

Participation in the research project was voluntary, with written informed consent obtained. The procedure involved two meetings: preparation and implementation. During the first meeting, participants were introduced to the performance conditions (researcher, piano type, acoustics, procedure, etc.), the Emomix form, and completed self-report inventories. They were then asked to prepare a piece of music of their choice to ensure comfortable experimental conditions.

At the second meeting, participants performed after a ten-minute waiting period, during which they used the Emomix form to track emotional changes and thoughts (the three-step task loop) and were also free to behave as they normally would during such a waiting period. Then the musicians performed solo in front of a video camera and researcher. Post-performance evaluation included subjective and objective measures of performance quality: the immediate ratings of the musician’s satisfaction and the delayed expert ratings of the recordings. Each participant was paid €10 for their participation.

Data analysis

I analysed the data in four phases using PS IMAGO PRO 9.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 29) and JASP 0.16.2. First, I performed a frequency analysis to assess how often each pre-performance emotion was reported. For each participant, I calculated the frequency of an emotion as a percentage: the ratio of the number of times a given emotion was mentioned to the total number of emotions selected within ten minutes. I calculated the intensity of an emotion as the average of its intensity indicators. To obtain an index of saturation with the emotion, I multiplied frequency by intensity, which allowed me to use multiple emotion choices in further analyses.

I analysed qualitative data using content analysis53, developing categories of meaning among the emotion-accompanied thoughts described by the musicians. To identify pre-performance emotion profiles, I conducted a K-means cluster analysis. Finally, to compare the profiles in terms of dispositional and situational variables, I ran a series of Kruskal–Wallis H-tests, followed by Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Figner pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Frequency analysis

Throughout the ten-minute waiting period, participants made an average of eight emotional selections to characterise their emotional state (M = 8.26, SD = 5.78). Most participants (81%) made between two and twelve emotional selections; extreme selections of 1 or 40 were rare (0.8% of participants on either side).

Participants most frequently selected four of twelve emotional categories (M = 4.61, SD = 1.74). The majority of participants’ choices fell within the range of two to seven categories (94% of respondents); extreme choices of 1 or 9 categories were rare (1.6% of respondents on either side). The number of emotion categories correlated with the LEAS emotion awareness score (r =.210, p <.05).

The participants most frequently used the nouns hope (83%), curiosity (81%), and fear (77%) to describe their emotional state before the performance. Only five participants used the term disgust; therefore, this emotion was excluded from further analysis. Most respondents did not use the term neutral (68% of respondents), a few (21%) used it one to four times during the ten-minute period. The largest proportions of all emotions reported were fear (29%), hope (25%) and curiosity (24%), and the smallest, anger (12%). Hope and curiosity had the highest intensity indices (3.75 and 3.73 respectively). The results are presented in Table 1.

The emotions felt in the experimental conditions were rated by participants as quite similar to those felt in real concert settings (M = 6.56; SD = 2.16; 1–10 range).

Content analysis

Almost half of the participants (N = 59) described thoughts accompanying emotions by completing the open-ended sentence (Emomix, Step 3) “I felt this emotion because I thought to myself...“. The qualitative data were analysed using a content analysis procedure comprising four stages: decontextualization, recontextualization, categorization, and compilation53. After an initial, open-minded reading of the material, I identified meaning units and grouped them into key categories, from which I derived conclusions about the sources of different pre-performance emotions. Reporting the frequency of categories and meaning units made it possible to integrate a qualitative approach with elements of quantitative methodology54. The results of the content analysis conducted for the individual emotions are presented in Table 2.

Most of the descriptions were related to the emotions of fear, curiosity, hope and joy. The results of the analysis indicate numerous potential sources of pre-performance emotions (34 categories), including personal or others’ expectations, somatic symptoms, felt emotions, individual goals, memories, actual conditions, and emotional attitudes towards the performed piece of music.

Cluster analysis

The results of the K-means cluster analysis revealed four pre-performance emotion profiles, which are presented in the Supplementary Table 1. and graphically in Fig. 1. I determined the optimal number of clusters (four) by examining a plot of inertia values for configurations ranging from two to five clusters, using the elbow method.

The pre-performance emotion profiles were labelled as follows:

(1) Curiosity and positive emotions – with a prevalence of curiosity, courage, joy and pride; fear and negative emotions are at the lowest level compared to other clusters.

(2) Fear and hope – a mixture of negative and positive emotional states, with a medium level of shame and sadness.

(3) Shame and negative emotions – extremely negative states associated with shame, anger, sadness; pride, hope and fear were at a medium level, with a low level of curiosity.

(4) Epistemic emotions and joy – with the prevalence of two ambivalent states, boredom and surprise, accompanied by a medium-to-high level of joy and a low level of curiosity.

Comparison analysis

The comparison of the four pre-performance emotional profiles with regard to the situational variables shows statistically significant differences between the clusters for all the situational variables, except for Experts’ evaluation. In turn, pairwise comparisons between clusters did not show statistically significant differences for Emotion regulation belief. Cluster 4 participants scored higher in Performance ability belief than participants in Cluster 3 (p =.086) and Cluster 2 (p =.062), but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

In the case of Perceived task difficulty, participants in Cluster 3 scored significantly higher than participants in Cluster 1 (p <.001), Cluster 4 (p =.012), and Cluster 2 on a tendency level (p =.051). Participants in Cluster 4 scored significantly higher on Level of preparation belief compared to Cluster 2 (p =.046). In Satisfaction with performance, participants in Cluster 3 scored significantly lower than participants in Cluster 1 (p =.039) and Cluster 4 (p =.048). The results are presented in Table 3.

The comparison of the four pre-performance emotional profiles with regard to dispositional variables showed no statistically significant differences in the LEAS and K-MPAI-R levels (Table 4).

In the case of the COPE results, the only statistically significant difference was observed for the Resignation scale. Pairwise comparisons showed that participants in Cluster 3 had higher scores on the Resignation scale than those in Cluster 4 (p <.05).

To explore the relationships between the variables, additional correlation matrix analyses were performed for all the studied variables with Satisfaction with performance and Experts’ evaluation. The results are presented in the Supplementary Table 2. For Experts’ evaluation, significant correlations were found only with Performance ability belief (r =.225, p <.05), while for Satisfaction with performance significant correlations were found with Performance ability belief (r =.413, p <.001), Emotion regulation belief (r =.341, p <.001), Resignation (r = −.225, p <.05), and Perspective Change (r =.183, p <.05). It is worth noting that the correlation between Experts’ evaluation and Self-evaluation was positive, low, and not statistically significant (r =.112, p =.223).

Discussion

The aims of the current study were to explore the components of musicians’ pre-performance emotional states and compare different emotional profiles in relation to both situational factors (self-efficacy beliefs, performance quality and satisfaction) and dispositional factors (vulnerability to music performance anxiety and emotion regulation skills).

Categories and sources of pre-performance emotions

The results from young adult musicians align with previous research on adolescents26,27, demonstrating their ability to experience pre-performance emotions in a complex way. During the ten-minute wait before performing, most adult musicians reported feeling between two and seven emotional categories: fear, hope, and curiosity were the most common emotions, while disgust and anger were rare. The latter was in line with the previous study on young musicians27. Higher emotional recognition skills correlated with the number of observed PPE, supporting existing theories34,35.

The results of the content analysis show 34 categories of meaning. The potential sources of pre-performance emotions are: performance conditions, own emotional feelings and physical sensations, level of preparation, own and others’ expectations regarding the quality of the performance, one’s own abilities and skills as a musician, performance goals, methods of self-regulation, and personal life events. Clear performance goals and positive self-evaluation lead to the emotions of curiosity, hope, joy, and courage, and may help to manage fear and worry about the future outcome.

The variety of identified factors suggests that musicians need to be prepared with skills to effect cognitive change and techniques for attention management34, which aligns with Gross’s theoretical framework of emotion regulation5. Research on interventions based on CBT55,56, ACT57, and mindfulness58,59 provides evidence of the effectiveness of these techniques in reducing anxiety and increasing self-efficacy in emotional regulation and emotional well-being in musicians.

The structure of pre-performance emotional experience

The four identified emotional profiles can be positioned along a continuum from the most positively to the most negatively saturated: Curiosity and positive emotions, Epistemic emotions and joy, Fear and hope, Shame and negative emotions. Direct comparison of the findings from these and previous studies26,27 is challenging due to methodological differences; however, they converge on a common overarching conclusion: even seemingly univalent emotional experiences involve a range of emotional categories. In addition, the analysis of musicians’ statements reveals the presence of meta-emotions, for example anger due to fear, surprise due to calmness, or pride due to courage. A mixed-emotion approach to studying pre-performance emotions thus appears to offer deeper insight into performers’ emotional worlds than single-dimensional measures of anxiety, shame, or self-confidence.

The interpretation of emotion configurations was carried out with consideration of cognitive data from the qualitative part of the study and compared with existing research: the Curiosity profile, including curiosity, courage, joy, and pride. Curiosity, an epistemic emotion, arises from a desire for new experiences or filling knowledge gaps60, often leading to joy. Courage, rooted in personal values and goals, helps to manage fear, as fear is a prerequisite for courage61. Pride, a self-conscious emotion⁹, is rooted in a sense of self-esteem. In our research, pride appears in two forms: authentic (e.g., satisfaction from seizing opportunities), which is adaptive and prosocial, and hubristic (e.g., belief in unique achievement), which leans towards narcissism62. The adaptive positive emotions in this profile can broaden the scope of attention, cognition, and action14, and can help in MPA regulation.

The Epistemic emotions and joy profile includes the ambivalent states of boredom and surprise, accompanied by joy. These epistemic emotions relate to knowledge quality and information processing10. In our research, surprise emerged from discrepancies between expected and actual performance conditions and a positive emotional response to the task. Mild surprises can deepen cognitive processing63; boredom was linked to long waits in unchallenging conditions64 and fatigue from daily tasks, sometimes leading to disengagement, which helps to maintain emotional distance. Joy stemmed from the opportunity to share the beauty of a favourite piece of music with listeners.

Previous research found a similar Joy combined with fatigue profile to be related to performance quality26. Because of the inclusion of a new group of epistemic and self-consciousness emotions, the comparison of these two profiles with previous research26,27 brings additional challenges.

The Fear and hope profile reflects mixed emotions – fear of failure alongside hope for a successful performance. This contrast itself serves as an emotion regulation strategy, involving cognitive reinterpretation and a focus on positive aspects15,65. Hope is the perceived ability to find pathways to goals and stay motivated to pursue them66. Closely linked to self-efficacy, hope is consistently associated with better outcomes in academics, sports, health, and psychological well-being67.

The Shame and negative emotions profile includes negative emotions of shame, anger, and sadness. Shame arises from judging oneself against internalised standards68, while anger and sadness serve as meta-emotional responses to this evaluation. Sadness reflects loss or failure to progress towards goals, fostering helplessness, resignation, and self-focus69. The last two profiles seem to be consistent with the MPA conceptualisation1,30. Given its emphasis on evaluation, incorporating self-conscious emotions like shame into MPA research could provide valuable insights.

The functional meaning of different pre-performance emotional profiles

At the outset, it is important to note that the profiles did not differ significantly in MPA vulnerability, with the entire group scoring moderately based on the K-MPAI-R cut-offs49. Regarding emotional skills, all profiles showed a comparable, moderate level of emotion recognition. Significant differences in emotion management skills were found only in the frequency of strategies used by the Resignation group. This higher-order factor includes avoidance and cessation strategies, such as self-blame, behavioural withdrawal, denial, and substance use29. Musicians in the Shame and negative emotions profile used these strategies more frequently than those in the Epistemic emotions and joy profile, which is consistent with Biasutti and Concina’s findings on MPA40.

There were also no statistically significant differences between the profiles in the experts’ ratings, as the entire group performed at a medium-to-high level. One possible explanation for this uniformity in both the aspects of feelings and performance level, is the voluntary nature of participation in the study, as well as the freedom to choose their own repertoire – allowing participants to select pieces in which they felt more confident and comfortable. Based on these findings, it can be inferred that the participants showed moderate vulnerability to MPA, possessed comparable emotional regulation skills, and demonstrated generally high performance abilities. Given these relatively balanced baseline characteristics, the observed differences in performance satisfaction may be more strongly influenced by situational factors rather than individual dispositions measured in this study.

The results of the current study suggest that musicians who experienced mixed emotional states dominated by positive emotions (as seen in the Epistemic emotions and joy and Curiosity and positive emotions profiles) exhibited higher self-efficacy beliefs related to performance abilities and preparation, and reported greater satisfaction with their solo performances. This supports the conclusions of Spahn et al.19 regarding the influence of self-efficacy beliefs on levels of MPA and performance quality.

The association with performance satisfaction aligns with the findings of Kaleńska-Rodzaj’s study26, where both positive and mixed emotional profiles were linked to higher levels of performers’ satisfaction. At this point, it is useful to compare the structure of these emotional profiles across the two studies. In the adolescent group, the Excitement profile of positive emotions included optimism, happiness, and satisfaction. In contrast, in the adult group, the Curiosity and positive emotions profile comprised curiosity, courage, joy, and pride. The Impatience-mixed emotions profile among adolescents consisted of optimism, happiness, satisfaction, anxiety, and impatience, whereas in adults it featured boredom and surprise, accompanied by joy. Despite the differences in methodology and the resulting variation in emotional configurations, it is important to emphasise the role of positive emotions in both age groups regarding satisfaction with performance, as well as the role of epistemic emotions (curiosity, surprise, boredom) in describing pre-performance emotional states in the adult group. Future research should continue to include emotions from the epistemic category.

The findings also highlight the functional disadvantages of the Shame and negative emotions profile for performance satisfaction. Musicians with the Shame… profile perceived the chosen piece of music as more difficult than participants with other profiles. It is possible that they chose a more challenging repertoire, thus giving themselves less chance to perform with emotionally comfortable conditions. In previous studies, the High MPA and Moderate MPA profiles demonstrated specific emotional structures marked by fear, helplessness, and fatigue in the adolescent group26, and by fear, low self-confidence, and sadness among younger musicians27. In the present study, the only profile that was distinctly negatively saturated was the Shame… profile, which may offer a novel, self-evaluative perspective for MPA research.

To sum up, the results are consistent with research on goal-directed activity, which indicates that positive and mixed emotions enhance performance14, while negative emotions alone reduce performance quality and satisfaction14,26,70.

Additional analyses suggest a weak correlation between musicians’ self-assessment and expert evaluations. This implies that self-evaluations may not always align with external assessments and could be influenced by factors such as emotional regulation skills. It is important to consider both objective and subjective performance indicators in evaluating outcomes, although these results require further confirmation through additional research.

Strengths and weaknesses

It is worth mentioning that this study is still exploratory in nature. Its key contribution is its focus on the complexity of pre-performance emotional states, highlighting the value of a mixed-emotion approach. This method goes beyond the univalent positive (confidence) or negative (MPA) pre-performance emotions and introduces intermediate states, offering new insights. By studying musicians across different age groups, the research also expands the developmental perspective, which will enable the application of the findings in developing emotional education and MPA prevention programmes for musicians of different ages.

The qualitative findings connect emotional labels with their cognitive meanings in the solo performance context. Understanding the sources of these emotions can be valuable for musicians, educators, and psychologists, helping to foster hope, courage, and positive attitudes in performance settings. This knowledge provides insights into how to help musicians maintain focus on the helpful aspects of the situation and task.

Standardising research with Emomix pre-performance emotion list would enable better comparison and more definitive conclusions, which, at present, are only general due to previous studies26,27. Nonetheless, this research reveals a variety of emotional profiles and their links to self-efficacy and performance outcomes. Future studies should unify the music task and incorporate strategies for practice to better explain the relationships between pre-performance emotions and performance satisfaction.

Research conducted in live performance situations carries the risk of attention depletion between preparation and emotion-monitoring1,2,20. Verbalising thoughts may also be demanding, which could explain why cognitive interpretation was only obtained from half of the subjects. Although participants reported emotions similar to those experienced during actual performances, repeating the study in a real concert setting (not only camera and researcher), with an improved procedure and Emomix measurement tool, would be valuable.

Lastly, future research should consider increasing sample size and balancing gender proportions to explore potential gender differences in the measured variables.

Practical implications

The results from musicians with moderate MPA vulnerability, emotion regulation skills, and high performance quality explain differences in performance satisfaction through self-efficacy beliefs and the structure of pre-performance emotional experience. Notably, musicians with the Shame… profile face the most difficult psychological situation, as they tend to use resignation strategies, select more challenging repertoire, and report lower satisfaction despite high performance quality. This is a common reason why high-achieving musicians seek psychological support, often citing excessive emotional costs and a lack of satisfaction with performances.

An important task to enhance well-being during performances is developing musicians’ emotional regulation skills. Educators and psychologists should help musicians to recognise and accurately label emotions, focusing on helpful emotions like hope, joy, and curiosity alongside fear. By understanding their pre-performance emotional experience, musicians can use emotions to shape their musical interpretation, rather than suppressing them.

Combining this emotional awareness with knowledge of one’s personality traits and skills allows a performer to regulate their emotions effectively by flexibly using a wide range of strategies71. Self-efficacy beliefs are crucial for musicians’ emotional well-being and satisfaction with their performance. Therefore, supporting musicians in developing self-efficacy in emotion regulation, preparation (effective practice), and performance on stage is an essential task for music educators and psychologists.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request. Data cannot be shared openly to protect study participant privacy (qualitative study part).

References

Kenny, D. T. Oxford University Press, Oxford,. The role of negative emotions in performance anxiety. in Handbook of music and emotion: theory, research, applications. (eds. Juslin P. N. & Sloboda J. A.) 425–451 (2010).

Herman, R. J. & Clark, T. It’s not a virus! reconceptualising and de-pathologising music performance anxiety. Front. Psychol. 14, 1194873 (2023).

Clark, T., Lisboa, T. & Williamon, A. An investigation into musicians’ thoughts and perceptions during performance. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 36, 19–37 (2014).

Buma, L. A., Bakker, F. C. & Oudejans, R. R. D. Exploring the thoughts and focus of attention of elite musicians under pressure. Psychol. Music. 49, 459–472 (2015).

Gross, J. J. & Thompson, R. A. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations. in Handbook of emotion regulation (ed. Gross J. J.) 3–24The Guilford Press, New York, (2007).

Ekman, P. Basic emotions. in Handbook of cognition and emotion (eds. Dalgleish T. & Power M. J.) 45–60 (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, (1999).

Izard, C. E. Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion-cognition relations. Psychol. Rev. 99, 561–565 (1992).

Plutchik, R. A psychoevolutionary theory of emotions. Social Sci. Inform. 21, 529–553 (1982).

Lewis, M. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. in Handbook of Emotions (3rd ed.) (eds Lewis, M. & Haviland-Jones, J. M.) (2008). & Barrett L. F.) 742–756 (The Guilford Press.

Pekrun, R. & Stephens, E. J. Academic emotions. In APA Educational Psychology handbook, Vol 2: Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors 3–31 (American Psychological Association, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1037/13274-001.

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. Music performance anxiety and pre-performance emotions in the light of psychology of emotion and emotion regulation. Psychol. Music. 49, 1758–1774 (2021).

Larsen, J. T. & McGraw, A. P. The case for mixed emotions. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass. 8, 263–274 (2014).

Oceja, L. & Carrera, P. Beyond a single pattern of mixed emotional experience. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 25, 58–67 (2009).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226 (2001).

Folkman, S. & Moskowitz, J. T. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am. Psychol. 55, 647–654 (2000).

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L. & Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 131, 803–855 (2005).

Hershfield, H. E., Scheibe, S., Sims, T. L. & Carstensen, L. L. When feeling bad can be good: mixed emotions benefit physical health across adulthood. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 4, 54–61 (2013).

Perdomo-Guevara, E. & Dibben, N. Cultivating meaning and self-transcendence to increase positive emotions and decrease anxiety in music performance. Psychol. Music. 53, 337–354 (2024).

Spahn, C., Krampe, F. & Nusseck, M. Live music performance: the relationship between flow and music performance anxiety. Front. Psychol. 12, 725569 (2021).

Guyon, A. et al. How audience and general music performance anxiety affect classical music students’ flow experience: a close look at its dimensions. Front. Psychol. 13, 959190 (2022).

Simoens, V. L., Puttonen, S. & Tervaniemi, M. Are music performance anxiety and performance boost perceived as extremes of the same continuum? Psychol. Music. 43, 171–187 (2015).

Lamont, A. Emotion, engagement and meaning in strong experiences of music performance. Psychol. Music. 40, 574–594 (2012).

Marin, M. M. & Bhattacharya, J. Getting into the musical zone: trait emotional intelligence and amount of practice predict flow in pianists. Front. Psychol. 4, 853 (2013).

Gabrielsson, A. Emotion in strong experiences with music. in Music and emotion: Theory and research (eds. Juslin P. N. & Sloboda J. A.), 431–449 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001). (2001).

Gabrielsson, A. & Lindström Wik, S. Strong experiences related to music: A descriptive system. Musicae Sci. 7, 157–217 (2003).

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. Waiting for the Concert. Pre-Performance emotions and the performance success of teenage music school students. Pol. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.24425/119499 (2018).

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. Pre-performance emotions and music performance anxiety beliefs in young musicians. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 42, 77–93 (2020).

Rakei, A., Tan, J. & Bhattacharya, J. Flow in contemporary musicians: individual differences in flow proneness, anxiety, and emotional intelligence. PLoS One. 17, e0265936 (2022).

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. Emotionality and performance: an emotion-regulation approach to music performance anxiety. Musicae Sci. 27, 842–861 (2023).

Kenny, D. T. The Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Kantor-Martynuska, J. & Kenny, D. T. Psychometric properties of the Kenny-Music performance anxiety inventory modified for general performance anxiety. Pol. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.24425/119500 (2023).

Spahn, C., Tenbaum, P., Immerz, A., Hohagen, J. & Nusseck, M. Dispositional and performance-specific music performance anxiety in young amateur musicians. Front. Psychol. 14, 1208311 (2023).

McPherson, G. E., Osborne, M. S., Evans, P. & Miksza, P. Applying self-regulated learning microanalysis to study musicians’ practice. Psychol. Music. 47, 18–32 (2019).

Barrett, L. F. Feelings or words? Understanding the content in Self-Report ratings of experienced emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 266–281 (2004).

Lane, R. D. & Schwartz, G. E. Levels of emotional awareness: a cognitive-developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. Am. J. Psychiatry. 144, 133–143 (1987).

Barrett, L. F. & Gross, J. J. Emotional intelligence: a process model of emotion representation and regulation. in Emotions: current issues and future directions (eds. Mayne T. J. & Bonanno G. A.) 286–310Guilford Press, New York, (2001).

Kuppens, P. & Verduyn, P. Looking at emotion regulation through the window of emotion dynamics. Psychol. Inq. 26, 72–79 (2015).

Kobylińska, D. & Kusev, P. Flexible emotion regulation: how situational demands and individual differences influence the effectiveness of regulatory strategies. Front. Psychol. 10, 72 (2019).

Kenny, D., Driscoll, T. & Ackermann, B. Psychological well-being in professional orchestral musicians in australia: A descriptive population study. Psychol. Music. 42, 210–232 (2014).

Biasutti, M. & Concina, E. The role of coping strategy and experience in predicting music performance anxiety. Musicae Sci. 18, 189–202 (2014).

Fehm, L. & Schmidt, K. Performance anxiety in gifted adolescent musicians. J. Anxiety Disord. 20, 98–109 (2006).

Penley, J. A., Tomaka, J. & Wiebe, J. S. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J. Behav. Med. 25, 551–603 (2002).

McCormick, J. & McPherson, G. The role of Self-Efficacy in a musical performance examination: an exploratory structural equation analysis. Psychol. Music. 31, 37–51 (2003).

McPherson, G. E. & McCormick, J. Self-efficacy and music performance. Psychol. Music. 34, 322–336 (2006).

Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: the Exercise of Control (Freeman, 1997).

González, A., Blanco-Piñeiro, P. & Díaz-Pereira, M. P. Music performance anxiety: exploring structural relations with self-efficacy, boost, and self-rated performance. Psychol. Music. 46, 831–847 (2018).

Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. in Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (eds. Pajares F. & Urdan T.) 307–337 (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, (2006).

Kenny, D. T. The factor structure of the Revised Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory. in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Performance Science (ed. Williamon A.) 37–41 (Association Européenne des Conservatoires, Utrecht, (2009).

Kenny, D. T. The Kenny music performance anxiety inventory (K-MPAI): scale construction, cross-cultural validation, theoretical underpinnings, and diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Front. Psychol. 14, 1143359 (2023).

Szczygieł, D. & Kolańczyk, A. Skala Poziomów Świadomości Emocji – adaptacja Skali lane’a i Schwartza [The Polish adaptation of the levels of emotional awareness Scale]. Roczniki Psychologiczne. 3, 155–179 (2000).

Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: consider the brief Cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 4, 92–100 (1997).

Juczyński, Z. & Ogińska-Bulik, N. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu I Radzenia Sobie Ze Stresem [NPSR. Tools for Measuring Stress & Coping with Stress] (Pracownia testów Psychologicznych PTP, 2009).

Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2, 8–14 (2016).

Krippendorff, K. Content analysis: an Introduction To its Methodology (SAGE Publications, Inc., 2019).

Burin, A. B. & Osorio, F. L. Interventions for music performance anxiety: results from a systematic literature review. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry. 43, 116–131 (2016).

Osborne, M. S., Greene, D. J. & Immel, D. T. Managing performance anxiety and improving mental skills in Conservatoire students through performance psychology training: a pilot study. Psychol. Well Being. 4, 18 (2014).

Juncos, D. G. Universal Publishers, Irvine, & de Paiva e Pona, E. ACT for Musicians: A Guide for Using Acceptance & Commitment Training to Enhance Performance, Overcome Performance Anxiety, and Improve Well-Being. (2022).

Farnsworth-Grodd, V. A. Mindfulness and the self-regulation of music performance anxiety. Preprint at http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz (2012).

Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V. & Midlarsky, E. Silent illumination: a study on Chan (Zen) meditation, anxiety, and musical performance quality. Psychol. Music. 36, 139–155 (2008).

Markey, A. & Loewenstein, G. Curiosity. in International handbook of emotions in education (eds. Pekrun R. & Linnenbrink-Garcia L.) 228–245 (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, (2014).

Rachman, S. J. Fear and Courage (2nd Ed) (W. H. Freeman and Compan, 1990).

Tracy, J. L. & Robins, R. W. The psychological structure of pride: A Tale of two facets. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 506–525 (2007).

Munnich, E. & Ranney, M. A. Learning from surprise: Harnessing a metacognitive surprise signal to build and adapt belief networks. Top. Cogn. Sci. 11, 164–177 (2019).

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R. & Graesser, A. Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learn. Instr. 29, 153–170 (2014).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer, 1984).

Snyder, C. R. The Psychology of Hope: You Can Get There from Here (Free, 1994).

Snyder, C. R. Hope theory: rainbows in the Mind. Psychol. Inq. 13, 249–275 (2002).

Stuewig, J. & Tangney, J. P. Shame and guilt in antisocial and risky behaviours. in The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (eds. Tracy L., Robins R. W. & Tangney J. P.) 371–388The Guilford Press, (2007).

Ellsworth, P. C. & Smith, C. A. Shades of joy: patterns of appraisal differentiating pleasant emotions. Cogn. Emot. 2, 301–331 (1988).

Lazarus, R. S. Emotion and Adaptation (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Moral-Bofill, L., de la López, A., Pérez-Llantada, M. C. & Holgado-Tello, F. P. Development of flow state Self-Regulation skills and coping with musical performance anxiety: design and evaluation of an electronically implemented psychological program. Front. Psychol. 13, 899621 (2022).

Funding

Julia Kaleńska-Rodzaj, University of the National Education Commission, Krakow, WPBU/2022/04/00195.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Julia Kaleńska-Rodzaj have performed all the experiments and approved the Final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaleńska-Rodzaj, J. Exploring the structure and functional meaning of pre-performance emotions in young adult musicians. Sci Rep 15, 43553 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27406-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27406-x