Abstract

As part of the industrial revolution, the collaborative robot (cobot) has become increasingly important in Industry 5.0. However, the most significant barrier for the industry to adopt the cobot is a lack of knowledge and skills. Therefore, e-learning should be designed to support high-performance learning. The purpose of this study is to incorporate the concept of gamification and a mental model learning structure into the design of a cobot training system and investigate its effectiveness. The experiments were divided into three conditions: current e-learning, gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and gamification based on a mental model structure. The results showed differences in effectiveness in terms of the success rate of using the cobot after training. Participants who were trained by current e-learning, gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and gamification based on the mental model structure achieved success rates of using the cobot for a basic pick-and-place task of 15%, 53%, and 74%, respectively. Besides, participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure spent less time on the task and made fewer errors than the participants who learned through the other conditions. Regression analyses supported the structural relationships proposed in Technology Acceptance Model, demonstrating the role of Attitude Towards, together with Perceived Usefulness, in predicting Behavioral Intention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, the industrial revolution has transitioned to Industry 5.0, with human–robot collaboration as one of its key focuses1. This revolution has introduced the concept of a collaborative robot or cobot. However, the most significant barrier for the industry to adopt the cobot is a lack of knowledge and skills2,3. Therefore, training could be a key factor in the adoption of cobots by the industry1,4,5.

Traditional training for cobots has been conducted through the learning factory (LF)5,6,7,8. This requires an investment in LF resources, but LF remains limited to specific locations6,9. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the training was adapted to e-learning platforms. Although e-learning is a service that helps users to learn from any place at any time and provides flexibility, it is not guaranteed that it will be successful in transferring knowledge. Improper e-learning is an ineffective learning process that leads to confusion, dissatisfaction, and a drop in attention10. Thus, e-learning should be designed to support high-performance learning.

Gamification has been applied to guide learning and training in various fields. In the educational field, gamification can improve the effectiveness, efficiency, satisfaction, engagement, motivation, and performance of learning11,12. Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts13. Popular elements in gamification are points, levels, leaderboards, achievements, and badges14. Wu15 reported that gamification pedagogy enabled students to achieve the best learning performance compared with text-based, video, and collaborative pedagogy. Students who learned through gamification performed better on practical exercises and had a higher overall score16. Furthermore, Legaki, et al.17 found that gamification can improve student performance by up to 89.45% compared with traditional teaching methods, such as attending teachers’ lectures or self-reading.

Although there is growing evidence that gamification is an effective technique, the gamification design process does not consider the sequence of teaching. In other words, the design process does not consider the structure or organization of activities for facilitating learning. The instructional materials should be logically organized so that they help learners to conveniently build a block of new knowledge that can be linked to their prior knowledge. This could prevent a mismatch between teaching information and learners’ cognitive abilities18,19. According to Merrill20, the representation and organization of the knowledge to be learned have a great impact on learning. Knowledge that is well organized is easier to recall than unorganized knowledge21.

A mental model is an organized knowledge structure stored in memory22,23. In other words, it is a type of blueprint or component made up of an underlying structure of related concepts24. Merrill20 concluded that a mental model is composed of two major parts: knowledge structures (schemas) and processes for applying this knowledge (mental operations). Mental model structures may be organized as networks, with information chunks and concepts as nodes and associative connections between these nodes as links23,25. Students who learn according to a mental model have a 19% better procedural memory26. Especially if students have an accurate mental model, they do better quality work, spend less time on tasks, and make fewer errors27,28. Graham, et al.29 suggested that the progression in video games should follow the development of a mental model structure rather than increasing the games’ difficulty linearly, as many games do. The difficulty of a game should be increased by requiring the players to adapt their current mental model.

These two well-known concepts (gamification and mental models) have been used in different areas of study on educational technology. Gamification design for e-learning concentrated on the design to gamify educational applications, appropriate elements in a learning environment, and the appropriate design for each type of player. There is limited research on the use of mental models in gamification design. It remains unclear whether the structuring of information according to a mental model has additional benefits in the design of gamification in training systems. Therefore, in the e-learning of cobot, the effectiveness of gamification designed with and without a mental model structure should be compared. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to apply the concept of gamification and a mental model learning structure to the design of a cobot training system to investigate its effectiveness for learners. Moreover, the training not only affects objective performance but also may influence users’ perceptions of usability and technology acceptance. As Norman30 mentioned, that while the user interface can be modified through proper design on the system side, the human side can be shaped through training and experience. Similarly, Sharma and Yetton31 mentioned that training is one of the most important interventions that lead to greater user acceptance of technology. Accordingly, the SUS and TAM were measured in this study to investigate how each training condition affects user’s perception. The universal robot (UR) UR-CB series model was used in the present study since it is the leading model in the cobot market32. The experiment was divided into three between-subject conditions: current e-learning, gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and gamification based on the mental model structure. The implication is on the design of training systems that enhance the effectiveness, especially for cobot, to gain a better user adoption in the industry.

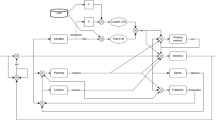

An information structure based on a mental model should be organized in a hierarchical manner, with the most general information at the top and the most specific information at the bottom22,23,33. Figure 1 illustrates the teaching structure of the current e-learning while Fig. 2 illustrates the teaching structure based on a mental model. The process of organizing the knowledge structures of cobot programming for a basic pick-and-place task can be summarized as follows.

- The 1st step::

-

Start with the goal, and then continue with the main components of the cobot system. In this study, Level 1 provides an overview of the cobot by introducing the three basic components of the cobot: the user interface, the control box, and the arm.

- The 2nd step::

-

After the introduction of the basic components, this step proceeds from the broad to the specific information. The key to commanding a cobot is the logic of movement. In this study, Level 2 provides information about the waypoints and the type of movement to understand the motion sequence and the appropriate type of motion for each situation before the user can create a structured program. This facilitates the formation of structures and links between components.

- The 3rd step::

-

Then, the next step is about how to use the device to command a cobot. In this study, Level 3 provides information on the user interface for programming the control of a cobot.

- The 4th step::

-

The final step concerns the most specific information at the bottom. Level 4 provides information on the functions for creating a program by learning how to create and sequence the functions for programming.

According to Merrill20, knowledge can be organized into entity, action, process, and property. Learning is enhanced when these components are organized into well-structured, meaningful sequences that reflect how knowledge is stored and manipulated in mental models. In our instructional design, the content is structured into four levels, each corresponding to Merrill’s knowledge object types, as shown in Fig. 3. The entity introduces the top-level schema, referring to elements that need to be recognized and differentiated. The process is reflected by Level 2. These steps represent a procedural scheme guiding learners through the task flow. Property is reflected by Levels 3 and 4. The property includes qualitative and quantitative attributes of the cobot’s software interface. These properties describe how learners interact with the system. Associative links are used to connect these levels meaningfully. The link from entity to process shows how physical components are involved in operational sequences. The link from process to property shows the procedural steps to corresponding interface actions and guides learners to manipulate functions and build executable programs.

Methodology

Participants

A group of sixty volunteers consisting of graduate and undergraduate engineering students participated in this study. Forty participants are male. Their age ranges from 20 to 34 years old. All participants passed the prerequisites in a fundamental programming course to ensure an understanding of basic programming logic (sequence, loops, conditionals) to reduce variability in programming logic and were not experts in robot programming. All participants were randomly assigned to each of the conditions: current e-learning (N = 20; age M = 20.8, SD = 0.52; 16 males), gamification based on the current e-learning structure (N = 20; age M = 23.3, SD = 2.86; 13 males), and gamification based on a mental model structure (N = 20; age M = 23.8, SD = 3.57; 11 males).

Stimulus materials

Training material for current e-learning

The current e-learning training material was a free e-learning course of the UR-CB series provided by Universal Robot34. It consists of four chapters instructing how to program a basic pick-and-place task: (1) overview, user interface, and function; (2) a case study of pick-and-place movements; (3) type of movement; and (4) set and wait functions and creating a program. This e-learning takes an average total time of 30 min to complete all four chapters.

Training material for gamification based on the current e-learning structure

The training material for the gamification based on the current e-learning structure was designed following the concept of gamification for education introduced by Huang and Soman35. There are five steps: (1) comprehending the intended audience and the context, (2) defining learning goals, (3) planning the experience, (4) identifying resources, and (5) applying the gamification elements. The gamification elements include points, levels, badges, a leaderboard, progress bars, a storyline, and feedback36. The information was sequenced in accordance with the current e-learning training material. An example of the gamification prototype used in this study is shown in Fig. 4. It consists of four chapters instructing how to program a basic pick-and-place task: (1) overview, user interface, and function; (2) a case study of pick-and-place movements (3); type of movement; and (4) set and wait functions and creating a program. This e-learning takes an average total time of 50 min to complete all four chapters.

Throughout all chapters, core content including text, graphics, short videos, and quizzes were delivered through four consistent steps, with gamification elements integrated: (1) Storyline and mission briefing through text and graphics: core textual information for concepts and instructions, presented in a more engaging narrative context. Text was used to communicate the storyline and mission briefings. (e.g., “Level 1: Identify the three main cobot components including, User Interface, Control Box, and Arm to collect three “Hearts” and advance to the next level”) (2) Content delivery through graphics: Static diagrams or short videos to demonstrate concepts. (3) Knowledge evaluation and feedback and guidance through quizzes and graphics. Correct answers earned points, while incorrect responses triggered hints. (4) Reward and progression through graphics: Points, progress bars, and badges were awarded for chapter completion, and a leaderboard displayed learners’ relative standings, providing motivational cues. (see Fig. 5).

Training material for gamification based on a mental model structure

The training material for gamification based on a mental model structure was designed in the same way as training material for gamification based on the current e-learning structure, except that the information structure was organized and sequenced according to a mental model structure of cobot programming. It consists of four chapters instructing how to program a basic pick-and-place task: (1) overview, (2) waypoints and type of movement (3), user interface, and (4) functions and creating a program. The four chapters of this e-learning course take an average total of 50 min to complete.

Task

A basic pick-and-place task was used as a test task, which the participants had to perform after finishing training with the assigned training materials. The task was to instruct a cobot to move a box from point A to point B by using an offline simulator (version 3.15.4) for non-Linux computers37. All interactions with the cobot simulator were performed via block-based visual programming through the graphical user interface; no text-based coding was required. All participants started on the same page of the program (see Supplementary Video). The experimental conditions were as follows:

-

Instruct a cobot to move a box from point A to point B by using the simulator program.

-

While the cobot is gripping, wait 1 s for the gripper to completely finish the work.

-

“tool_out [0]” is the gripper (with a weight of 0.6 kg), the box weighs 1 kg, and the total payload is 1.6 kg.

Measurements

Performance metrics

The performance metrics used in this study were success rate, time on task, and error analysis to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the designed training condition. The success rate was defined as the proportion of participants who completed the task versus those who did not. Non-completion included two cases: (1) submitting an incorrect answer, or (2) abandoning the task, such as when a participant requested to withdraw after being unable to return to the main interface to complete the task. The time on task measures the time participants spent to complete the task. The time on task for participants who could not complete the task was not included in this metric. The error analysis measures the frequency of errors during the performance of the task. Counting repeated errors of a participant was allowed. Participants who abandoned the task were not included in the error analysis since the errors made before they abandoned the task would affect the coding of the number of errors.

Self-reported metrics

The self-reported metrics used in this study were an engagement questionnaire38, the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire39, and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) questionnaire40. All questionnaires used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The engagement questionnaire measures participants’ perceptions of the training system. It records the responses to the following three statements: (1) “I find the learning material attractive,” (2) “I felt involved while learning the learning material,” and (3) “The experience of learning the learning material was fun.” The average scores were used for further analysis. The SUS questionnaire assesses the subjective perception of the cobot’s usability through 10 standard SUS questionnaires. The sum scores were converted into percentiles for standard SUS comparison41. The TAM questionnaire measures a participant’s attitude toward the cobot42. It consists of four main parts: Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Attitude Towards (AT) using the cobot, and Behavioral Intention (BI) to use the cobot. The average score of each part was used for further analysis.

Procedure

First, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants, and a brief description of the research was provided to them. Then, the participants were requested to read and sign a consent form to voluntarily participate in the study. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the following training conditions: current e-learning, gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and gamification based on the mental model structure. They were asked to fill out the demographic questionnaire and access the prerequisite conditions.

In a private and quiet room with a laptop computer, the participants were asked to do self-study with only the assigned e-learning system on how to use the cobot. After finishing the self-study, they were asked to rate the engagement questionnaire. Then, the instructions of the test task were explained to them, and they were asked to perform the test task of controlling the cobot with a controller program on a laptop computer. At the end, the participants were requested to evaluate the cobot using the SUS and TAM questionnaires.

Data analysis methods

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.2.0). Before the results were analyzed, data points were screened for outliers using box‐plot inspection and the mean ± 3 SD rule. Two data points in the time on task measure exceeded the threshold and extreme values were excluded before analysis to avoid unduly influencing the results of group comparisons (uncharacteristically long completion times). After their exclusion, no further outliers were detected, and all remaining data were retained for analysis.

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to test significant differences across the three training conditions. Before conducting ANOVA, the assumptions of the test were examined: normality of the dependent variable’s distribution for each group was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances across groups was assessed using Levene’s test. Once the assumptions were met, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc tests were performed to determine specific pairwise differences between groups for variables where the assumption of homogeneity of variances was met. Fisher’s LSD was chosen for these comparisons due to its robust performance when group sizes are unequal, as observed in our study. Dependent variables compared using LSD included time on task, number of errors, engagement, SUS, PU, and BI. For variables where the assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated, specifically PEOU and AT, Games-Howell post hoc tests were utilized to determine specific pairwise differences between groups. This method is robust to unequal variances and unequal group sizes.

For the success rate outcome, which is a binary categorical variable (completion versus non-completion of tasks), Pearson’s Chi-square Test of independence was employed to compare the proportions of success across the three training conditions. Significance levels for all statistical tests were set at p < 0.05.

To validate the TAM relationships, multiple linear regression analyses were performed separately for each training condition. According to TAM42, three regression models were tested corresponding to the TAM pathways: (1) PU predicted by PEOU, (2) AT predicted by PU and PEOU, and (3) BI predicted by AT and PU. Before analysis, regression assumptions were examined following the guidelines of Leech, et al.43. Normality of residuals was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Cases that contributed to non-normal residuals were excluded, resulting in adjusted sample sizes of n = 18 for the Gamification structure and n = 17 for the Gamification-based on the user’s mental model structure, after which all models satisfied the normality assumption. Homoscedasticity was evaluated using the White test, and multicollinearity was examined using tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values.

Results

The descriptive statistics for the performance and self-reported dependent variables across the three training conditions are presented in Tables 1 and 2, while the regression analyses are summarized in Table 3.

Performance metrics

Success rate

The results revealed that 15% of the participants who learned through the training condition of current e-learning could complete the task. As shown in Fig. 6, 53% of the participants who learned through the training condition of gamification based on current e-learning could complete the task. Furthermore, 74% of the participants who learned through the training condition of gamification based on the mental model structure could complete the task. The success rate analysis confirmed that the participants learning through gamification based on the mental model structure (p < 0.001) and those learning through gamification based on the current e-learning structure (p = 0.013) had a significantly higher success rate of performing the task than those learning through the current e-learning structure. There were no significant differences in success rate between participants learning through gamification based on the mental model structure and those learning through gamification based on the current e-learning structure.

Time on task

The time that users of each training condition spent on the pick-and-place task is reported in Table 1. The results show that participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure performed the task significantly faster than those who learned through gamification based on the current e-learning structure training (p = 0.019). There are no significant differences in time on task between participants learning through the current e-learning structure and those learning through gamification based on the current e-learning structure.

Number of errors

Two participants from the current e-learning training condition who abandoned the test task were not considered in counting the number of errors, leaving the data of 18 participants for the current e-learning training condition. The average number of errors per participant for each training condition is shown in Table 1. The total numbers of errors were 176, 117, and 99 for the current e-learning structure, gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and gamification based on the mental model structure, respectively. The result showed that participants who learned through gamification based on the current e-learning structure (p = 0.08) and gamification based on the mental model structure (p < 0.001) made significantly fewer errors than those who learned through the current e-learning structure, as shown in Fig. 7.

Self-reported metrics

Engagement

The average engagement for each training condition is shown in Table 2. The results showed that both participants who learned through gamification based on the current e-learning structure (p < 0.001) and participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure (p < 0.001) reported a significantly higher level of engagement in the training materials than those who learned through the current e-learning structure.

System usability scale

The results revealed that participants who learned through gamification based on the current e-learning structure (p = 0.007) and participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure (p = 0.019) rated their SUS questionnaire significantly higher than those who learned through the current e-learning training structure.

Technology acceptance model

The results of TAM were reported separately for each dimension, as shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in PU between each training condition. The results revealed that participants who learned through gamification based on the current e-learning structure rated PEOU (p = 0.08), AT (p = 0.035), and BT (p = 0.029) significantly higher than those who learned through the current e-learning training structure. Also, participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure rated PEOU (p < 0.001), AT (p = 0.003), and BI (p = 0.001) significantly higher than those who learned through the current e-learning structure.

Regression results are summarized in Table 3, which reports model fit indices (R2, Adjusted R2, Standard Error of the Estimate, F-statistics, and significance levels) along with predictor-level statistics (standardized coefficients β, t-values, and p-values). Analyses were conducted separately for each training condition, with significance set at p < 0.05. The BI, predicted by AT and PU, was significant in all three conditions: current e-learning structure (R2 = 0.582, p < 0.001), gamification structure (R2 = 0.400, p = 0.022), and gamification based on the mental model structure (R2 = 0.704, p < 0.001). AT consistently emerged as the strongest predictor of BI in the current e-learning (β = 0.695, p < 0.001) and the gamification based on the mental model structure (β = 0.840, p < 0.001), whereas PU was not a significant predictor. In the gamification structure, although the BI model was significant, neither AT nor PU individually predicted BI at a significant level. However, in this condition, PEOU significantly predicted PU (β = 0.565, p = 0.015, R2 = 0.320), and both PU (β = 0.412, p = 0.041) and PEOU (β = 0.501, p = 0.016) significantly predicted AT (R2 = 0.653, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Incorporating elements of gamification into learning material can increase success rates and engagement in learning. Although numerous studies have been published on various gamification elements regarding their application in learning material, it might not be necessary to apply all of them to improve the usability of the learning material. Following the research by Nah, et al.36, this study applied only the following gamification elements: points, levels, badges, leaderboards, progress bars, storylines, and feedback, which were shown to adequately improve the success rate. This could be explained by the multi-store model (MSM; Atkinson and Shiffrin44). Learners using the current e-learning system had no elements to attract their attention and to encourage them to keep focused, while learners using the gamification system were attracted by the gamification elements. These elements help information from the sensory organs to be stored in short-term memory. Getting feedback during the exercises is a kind of rehearsal process that supports the encoding of information into long-term memory45. In addition, levels and goals guide learners to divide information into different chunks, helping learners to store information before passing it from short-term memory to long-term memory46.

Besides, integrating the concept of information sequencing based on a mental model structure into a gamification design for e-learning revealed better user performance in the test task. Participants who received the training condition of gamification based on the mental model structure tended to have a higher success rate than those who received the training condition of gamification based on the current e-learning structure. They also spent significantly less time on the task and tended to make fewer errors in the test task than those who received the training condition of gamification based on the current e-learning structure. The information is organized according to the structure of a mental model, which corresponds to the arrangement of information in the brain. That is, the information is divided into chunks, and chunks are linked by concepts. This would help learners to systematically understand content relationships, enabling them to better transfer information from short-term memory to long-term memory47. The results of the present study confirmed that participants who learned through gamification based on the mental model structure could memorize information accurately and quickly recall it. This is consistent with a study showing that training based on a mental model can lead to better performance in tasks that require a process of understanding48.

In terms of self-reported metrics, the participants reported some degree of difficulty and redundancy with the user interface across all training conditions, which might be caused by the design of the user interface of the cobot’s controller or the participants’ reluctance to perform the test task after training. Possible solutions to these aspects that the developer of the cobot system might consider are (1) redesigning the user interface to ensure that there is minimal mismatch in understanding between the designer and the user and (2) providing quality training for users. Although this study improved the training by incorporating gamification techniques and information structures following the mental model theory, the results of SUS regarding the cobot’s user interface remained at an unacceptable level. It might be necessary to improve the user interface of the cobot’s controller to improve its usability so that it forms no barrier, leading to a better user acceptance in the market.

TAM has four key variables, including PU, PEOU, AT, and BI. Firstly, the results showed that participants rated a high level of PU regardless of their training condition and whether they were able to complete the task. Secondly, participants who received the training condition of gamification based on the current e-learning structure and participants who received the training condition of gamification based on the mental model structure rated the ease of use significantly higher than those who received the training condition of the current e-learning structure, even though the ratings of PEOU were not high. Finally, participants using the training condition of gamification based on the current e-learning structure and participants using the training condition of gamification based on the mental model structure had a significantly higher AT and BI than those using the training condition of the current e-learning structure. These results could be explained by realizing that even though the participants perceived the cobot’s user interface as not being user-friendly, they still considered it useful technology. This affects their attitude toward technology and their behavioral intention to use it in a positive way. Thus, a greater effort should be made to design a user-friendly interface, together with its valuable functions, to enhance users’ perception of the technology’s usefulness and ease of use. This would help accelerate user adoption and reduce the reluctance to introduce new technology in the industry1.

To validate the TAM framework, regression analyses provided further insight into the structural relationships among TAM constructs. The findings demonstrated that the model including AT and PU significantly explained BI across all training conditions, with AT emerging as the strongest predictor in the current e-learning and gamification based on the mental model structure. This reinforces the central mediating role of AT in the TAM framework, aligning with previous research that has identified AT as a critical determinant of behavioral intention to use technology49,50. In some situations, PEOU significantly predicted PU, and both PU and PEOU predicted AT, which in turn predicted BI. This effect, however, was not observed consistently across all conditions and appeared only in the gamification structure. These findings are consistent with Holden and Karsh51, who found that PU and PEOU may not account for all significant components in predicting technology acceptance. Overall, these results confirm the applicability of the TAM framework in this context. This research emphasizes that AT, together with PU, explained BI, with AT emerging as the more consistent and pivotal predictor. This highlights the importance of fostering a positive user attitude through training, education, and hands-on experiences50.

Nevertheless, regardless of the incorporated information structure, the pilot design of gamification used in the present study requires longer training time than the current e-learning structure, although it could significantly improve the effectiveness of training. The design team should weigh the costs and benefits between investing in good-quality training, which may require both investments in training materials and time to train users, and investing in redesigning the interface so that it becomes more user-friendly, which may be a more sustainable solution.

Conclusion

This study investigated the differences in task performance of participants receiving different training conditions: (1) current e-learning, (2) gamification based on the current e-learning structure, and (3) gamification based on a mental model structure. The content in gamification based on a mental model structure was organized into hierarchical chunking, which facilitated deeper understanding. The structured sequencing supported learners in transferring information better from short-term memory to long-term memory. This research showed that incorporating an information sequence based on a mental model structure into a well-known gamification design for e-learning could significantly enhance the effectiveness of training for a cobot. Moreover, both gamification conditions could enhance the perceived usability and perceived ease of use, attitude toward use, and behavioral intention compared with e-learning. Finally, regression analyses confirmed the TAM framework, highlighting AT together with PU as the key predictors of behavioral intention.

There were some limitations, such as the small number of participants for each training condition and the quality of the graphics used in the gamification design of the training material, which may have affected the participants’ perception of the gamification design quality. In a future study, the experiment should be conducted with a larger and more diverse participant sample for each condition so that the statistical tests may give stronger results in some variables.

Data availability

The data in this study is not publicly available due to ethical and privacy concerns. All questionnaires, the testing task, and an example of usability testing in VDO are available in the supplementary files. Further details can be obtained from the corresponding author, Arisara Jiamsanguanwong, arisara.j@chula.ac.th, on reasonable request.

References

Demir, K. A., Döven, G. & Sezen, B. Industry 5.0 and human-robot co-working. Procedia Comput. Sci. 158, 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.104 (2019).

Kildal, J., Tellaeche, A., Fernández, I. & Maurtua, I. Potential users’ key concerns and expectations for the adoption of cobots. Procedia CIRP 72, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.03.104 (2018).

Aaltonen, I. & Salmi, T. Experiences and expectations of collaborative robots in industry and academia: barriers and development needs. Procedia Manuf. 38, 1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.01.204 (2019).

El Zaatari, S., Marei, M., Li, W. & Usman, Z. Cobot programming for collaborative industrial tasks: An overview. Robot. Auton. Syst. 116, 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2019.03.003 (2019).

Simões, A., Soares, A. & Barros, A. Factors influencing the intention of managers to adopt collaborative robots (cobots) in manufacturing organizations. J. Eng. Tech. Manage. 57, 101574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2020.101574 (2020).

Abele, E. et al. Learning factories for future oriented research and education in manufacturing. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 66, 803–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2017.05.005 (2017).

Sudhoff, M., Prinz, C. & Kuhlenkötter, B. A systematic analysis of learning factories in Germany—concepts, production processes, didactics. Procedia Manuf. 45, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.04.081 (2020).

Tisch, M. & Metternich, J. Potentials and limits of learning factories in research, innovation transfer, education, and training. Procedia Manuf. 9, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.04.027 (2017).

Matt, D. T., Rauch, E. & Dallasega, P. Mini-factory–A learning factory concept for students and small and medium sized enterprises. Procedia CIRP 17, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2014.01.057 (2014).

Yekefallah, L., Namdar, P., Panahi, R. & Dehghankar, L. Factors related to students’ satisfaction with holding e-learning during the Covid-19 pandemic based on the dimensions of e-learning. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07628 (2021).

Huang, R. et al. The impact of gamification in educational settings on student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1875–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09807-z (2020).

Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M. & Perera, C. J. The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educ. Res. Rev. 30, 100326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100326 (2020).

Deterding, S., Khaled, R., Nacke, L. & Dixon, D. In CHI 2011: Gamification Workshop Proceedings. 12–15.

Dichev, C. & Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0042-5 (2017).

Wu, Y.-L. Gamification design: A comparison of four m-learning courses. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 55, 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1250662 (2018).

Domínguez, A. et al. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 63, 380–392 (2013).

Legaki, N.-Z., Xi, N., Hamari, J., Karpouzis, K. & Assimakopoulos, V. The effect of challenge-based gamification on learning: An experiment in the context of statistics education. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 144, 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102496 (2020).

Neumann, K. L. & Kopcha, T. J. The use of schema theory in learning, design, and technology. TechTrends 62, 429–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0319-0 (2018).

Ye, L., Zhou, X., Yang, S. & Hang, Y. Serious game design and learning effect verification supporting traditional pattern learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2042032 (2022).

Merrill, M. D. Knowledge objects and mental models. In Proceedings International Workshop on Advanced Learning Technologies. IWALT 2000. Advanced Learning Technology: Design and Development Issues 244–246 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1109/IWALT.2000.890621

Collins, A. & Loftus, E. A spreading activation theory of semantic processing. Psychol. Rev. 82, 407–428 (1975).

Lekshmi, D. Schema mental models and learning an overview. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 2800–2807 (2020).

Furlough, C. S. & Gillan, D. J. Mental models: Structural differences and the role of experience. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 12, 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343418773236 (2018).

van Ments, L. & Treur, J. Reflections on dynamics, adaptation and control: A cognitive architecture for mental models. Cogn. Syst. Res. 70, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2021.06.004 (2021).

Lokuge, I., Gilbert, S. A. & Richards, W. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 413–419 (Association for Computing Machinery, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 1996).

Kieras, D. E. & Bovair, S. The role of a mental model in learning to operate a device. Cogn. Sci. 8, 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(84)80003-8 (1984).

Busselle, R. Schema theory and mental models. Int. Encycl. Media Eff. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0079 (2017).

Coulson, T., Shayo, C., Olfman, L. & Rohm, T. ERP Training Strategies: Conceptual Training and the Formation of Accurate Mental Models. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMIS CPR Conference, (2003).

Graham, J., Zheng, L. & Gonzalez, C. A cognitive approach to game usability and design: mental model development in novice real-time strategy gamers. CyberPsychol. Behav. 9, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.361 (2006).

Norman, D. 31–61 (1986).

Sharma, R. & Yetton, P. The contingent effects of training, technical complexity, and task interdependence on successful information systems implementation. MIS Q. 31, 219–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148789 (2007).

Sharma, A. Cobot Market Outlook Still Strong, Says Interact Analysis, <https://www.roboticsbusinessreview.com/manufacturing/cobot-market-outlook-strong/> (2019).

Clarke, J. H. Using visual organizers to focus on thinking. The Journal of Reading 34, 526–534 (1991).

Academy, U. R. Vol. 2022 (Universal Robots, 2019).

Huang, W.H.-Y. & Soman, D. Gamification of education. Rep. Ser. Behav. Econ. Action 29, 37 (2013).

Nah, F. F.-H., Zeng, Q., Telaprolu, V. R., Ayyappa, A. P. & Eschenbrenner, B. In HCI in Business (ed Fiona Fui-Hoon Nah) 401–409 (Springer International Publishing, 2014).

UniversalRobots. (Universal Robots 2019).

Cechetti, N. P. et al. Developing and implementing a gamification method to improve user engagement: A case study with an m-Health application for hypertension monitoring. Telemat. Inform. 41, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.04.007 (2019).

Brooke, J. in Usability Evaluation In Industry 189–194 (1996).

Lin, C.-C. Exploring the relationship between technology acceptance model and usability test. Inf. Technol. Manag. 14, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-013-0162-0 (2013).

Sauro, J. & Lewis, J. R. In Quantifying the User Experience (eds Jeff Sauro & James R. Lewis) 185–240 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2012).

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P. & Warshaw, P. R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 35, 982–1003 (1989).

Leech, N. L., Barrett, K. C. & Morgan, G. A. IBM SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation. (Routledge, 2014).

Atkinson, R. C. & Shiffrin, R. M. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation Vol. 2 (eds Kenneth W. Spence & Janet Taylor Spence) 89–195 (Academic Press, 1968).

Li, L. & Tai, C. 1291–1303 (Atlantis Press).

Sweller, J. et al. The split-attention effect. Cognitive load theory, 111–128 (2011).

Fountain, S. B. & Doyle, K. E. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (ed Norbert M. Seel) 1814–1817 (Springer US, 2012).

Allen, R. B. In Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction (eds Marting G. Helander, Thomas K. Landauer, & Prasad V. Prabhu) 49–63 (North-Holland, 1997).

Mailizar, M., Burg, D. & Maulina, S. Examining university students behavioural intention to use e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended TAM model. Educ. Inf. Technol. (Dordr) 26, 7057–7077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10557-5 (2021).

Kim, Y. J., Chun, J. U. & Song, J. Investigating the role of attitude in technology acceptance from an attitude strength perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 29, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.01.011 (2009).

Holden, R. J. & Karsh, B. T. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J. Biomed. Inform. 43, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2009.07.002 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The co-authors contributed to the research in the following ways: Yada Sriviboon; Main author, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, and Writing–Original Draft. Associate Professor Arisara Jiamsanguanwong D.Eng; Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing–Review & Editing, and Corresponding author. Professor Parames Chutima Ph.D.; Conceptualization, Methodology.; Associate Professor Oran Kittithreerapronchai Ph.D.; Conceptualization, Methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects: The Second Allied Academic Group in Social Sciences, Humanities and Fine and Applied Arts, at Chulalongkorn University (Number 660054. COA No.160/66).

Accordance statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Belmont Report, the CIOMS guidelines, and the International Conference on Harmonization–Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP).

Consent to participate

Before data collection, all participants were informed consent, and they were informed that they were free to decide whether to participate in this research and that there were no penalties for not participating. Participants were aware that their data would be included in the published paper as a part of an overview, not explicitly linked to any individual.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sriviboon, Y., Jiamsanguanwong, A., Chutima, P. et al. A gamification training system designed according to a mental model structure: A case study of universal robots. Sci Rep 15, 42010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27670-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27670-x