Abstract

The precise prevalence of pathogenic gene variants in high or moderate penetrance genes associated with hereditary cancer in Indonesia remains undetermined. Furthermore, the criteria for prioritizing individuals for genetic testing are not well-defined. This study examined gene variants in Indonesian familial cancer among both affected and unaffected individuals. A total of 159 participants from 55 families with a history of cancer, including affected (N = 61) and unaffected (N = 98) individuals, underwent genetic testing using germline DNA with the 113 multigene panel. Various cancer types were identified, including breast (N = 46), ovarian (N = 3), retinoblastoma (N = 3), colon (N = 2), uterine (N = 2), and other cancers (N = 1 each) such as lung, prostate, thyroid, bladder, and testicular seminoma. Pathogenic variants were identified in 10 (18.8%) of the 55 families, with 6 (60%) confirmed as hereditary cancer families. These variants were detected in 14 affected individuals, involving 8 distinct genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, MUTYH, PALB2, RAD51D, VHL, ERCC4, and RB1), and the prevalence was significantly higher in cases of early-onset (< 40 years) compared to late-onset cancer (53.8% vs. 14.6%, p < 0.01). These findings confirm that several pathogenic gene variants in familial cancer in Indonesia are inherited. This data is crucial for both affected and unaffected family members to facilitate appropriate management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) published the most recent estimates of the global cancer burden in 2022, indicating approximately 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths1. It is estimated that about 1 in 5 individuals will develop cancer during their lifetime, with approximately 1 in 9 men and 1 in 12 women succumbing to the disease1. Familial cancer has been pivotal in the exploration of cancer-predisposing genes, forming the scientific foundation for genetic testing (GT) and cancer genetic counseling (CGC)2. Familial cancer is characterized by the occurrence of cancer in multiple family members, whereas hereditary cancer is defined by the presence of inherited causal gene (s)3. A study utilizing data from the Swedish Cancer Registry reported that 13.2% of families were affected by cancer, with the proportion rising to 26.4% for prostate cancer, and high-risk families constituted 6.6% of all cancer-affected families4.

Indonesia, with an estimated population of 270 million, is experiencing a rising incidence of cancer cases5. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) data from 2022, breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer, accounting for approximately 66,271 new cases (16.2%), followed by lung cancer (9.5%), cervical cancer (9.0%), and colorectal cancer (8.7%)6. Studies on cancer within families can effectively elucidate the clustering of cancer symptoms among relatives and estimate familial risk, age of cancer onset, and the prevalence of cancer across different generations7.

Gene variants associated with familial cancer have been identified, with the specific type of cancer contingent upon the mutated gene. Hereditary cancer syndromes (HCS) genes, such as RB1, BRCA1, BRCA2, MLH1, and MSH2, in high or moderate penetrance type, function as suppressor genes necessitating biallelic inactivation to manifest their effects8. In instances where a gene is inactivated in a single allele and inherited, the remaining allele maintains its function, thereby preserving normal health status. Consequently, malignant transformation is typically initiated by a "second hit," which may include factors such as a sedentary lifestyle, stress, or hormonal influences8. Given the significant proportion (10–20%) of pathogenic germline variants linked to HCS, genetic testing is recommended through genetic counseling to evaluate and manage HCS risk9,10. Individuals possessing specific cancer-predisposing pathogenic gene variants are at risk for early-onset cancer and exhibit aggressive symptoms with high morbidity and mortality, depending on gene penetrance11. Therefore, the identification of gene variants in cancer patients and unaffected family members may enable early intervention, such as screening or prophylactic treatment, for those predisposed to cancer12.

Multigene panels are instrumental in identifying genetic predispositions, offering substantial advantages to patients through the facilitation of personalized treatment plans and the provision of preventive guidance to healthy relatives. Despite these benefits, the application of genetic screening for familial cancer is not widespread, particularly in resource-constrained settings such as Indonesia. The exact prevalence of pathogenic gene variants in high or moderate penetrance genes associated with hereditary cancer in Indonesia has yet to be determined. Additionally, the criteria for prioritizing individuals for genetic testing are not clearly defined. This research aims to analyze gene variants in Indonesian patients with familial cancer and their healthy relatives, generating critical data to support the future development of personalized treatment and genetic counseling strategies for cancer.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was initiated by Faculty of Medicine Diponegoro University with National and Faculty support funds, in collaboration with CITO clinical laboratory in Semarang that involved 22 branch laboratories. We also invited clinical oncologists from different centers to join in this study. Twelve areas in Indonesia (Jakarta, Bogor, Bandung, Tegal, Semarang, Purwodadi, Purwokerto, Solo, Magelang, Jogjakarta, Malang, Bali, and Padang) were involved.

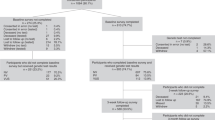

Cancer patients (affected individuals) who have one or more relatives also diagnosed with cancer, a condition termed familial cancer3, as well as their healthy relatives (unaffected individuals), were invited to take part in the study. All participants provided their consent for their data to be used in research (consent of childhood cancer patient was obtained from mother), with the condition that it would remain anonymized. The cancer diagnoses were confirmed from pathological reports, and the characteristic data of patients were completed from the medical records. The duration of study was from May to December 2023, including preparation of ethical clearance (May to July), recruitment (July to November) and genomic analysis (July to December). The final number of participants was 159 subjects, consisting of 61 affected and 98 unaffected subjects from 55 families with familial cancer. The inclusion criteria of affected subject were affected cancer with one or more affected family members, and age more than 18 years old (except childhood onset cancer, such as retinoblastoma). The inclusion criteria of unaffected subject were randomly selected from the subjects who are having blood related with the affected participant, in health condition, no cancer diagnose, and age more than 18 years old (except childhood onset cancer, such as retinoblastoma).

Gene variant analysis

Approximately 10 ml of venous blood was collected from the subjects. DNA extraction and PCR amplification were conducted prior to gene variant analysis using the TruSight Hereditary Cancer (TSH) 113 gene panel, following the manufacturer’s protocol on the Illumina MiSeq system to confirm genetic variants. Sequencing for gene variant analysis, including single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels), was performed using the DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform integrated within the Illumina BaseSpace Sequence Hub. The resulting VCF files were processed and annotated using the BaseSpace Variant Interpreter, which incorporates multiple public databases and in silico prediction techniques.

According to the guidelines of the Genomes Project Consortium 2015, variants were categorized based on their anticipated effects, with non-synonymous SNVs identified as stop-gain SNVs, stop-loss SNVs, and frameshift insertions/deletions (indels)13. Non-coding variations were characterized as those located in intronic or untranslated regions (UTRs) or other non-protein-coding segments of the target genes. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has established a framework for classifying genetic variants into five categories based on their pathogenicity: Pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign (LB), and benign (B)14. Variants classified as pathogenic (P) are considered clinically actionable and warrant disease-specific surveillance and/or management14.

Statistical analysis

Affected individuals were categorized based on germline status, distinguishing between pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants. The occurrence of each variant was reported as frequencies. A chi-square test was employed to assess the significance of the frequencies of pathogenic variants across different categories, specifically age and family history. P value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

This study comprised 159 participants from 55 families with a history of familial cancer, including affected cancer individuals (N = 61) and unaffected family members (N = 98) (Table 1). Among the affected individuals, 21.3% were 40 years old or younger, and the majority (91.8%) were female. The predominant type of cancer within these families was breast cancer, accounting for 67.2% of cases. The affected males (N = 5) were diagnosed with testicular seminoma, retinoblastoma, prostate cancer, lung cancer, and bladder cancer, and affected females (N = 56) were diagnosed with breast cancer, ovarian cancer, retinoblastoma, colon cancer, endometrial cancer, thyroid cancer, adenocarcinoma of the uterus, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. All participants underwent cancer genetic counseling (CGC) both before and after genetic testing (GT) to collect demographic data. Genetic counseling for families with retinoblastoma involving individuals under 18 years of age was conducted through the mother. No other participants under 18 years of age were included in this study. Germline DNA analysis was performed using the TruSight Hereditary Cancer (TSH) 113 gene panel.

In this study, the majority of affected participants were diagnosed with breast cancer (N = 46), retinoblastoma (N = 3), ovarian cancer (N = 3, with one case involving both ovarian and endometrial cancer), endometrial cancer (N = 2, with one case also involving Hodgkin lymphoma), and colon cancer (N = 2). Additionally, there was one case each of lung, prostate, thyroid, bladder, and testicular seminoma. Utilizing the TSH panel, 113 genes from all respondents, including both patients and their families, were analyzed. Table 2 presents the distribution of 220 gene variants, comprising 14 pathogenic, 21 benign/likely benign, and 185 variants of uncertain significance (VUS) across all 61 different cancer-affected subjects. Pathogenic variants were predominantly identified in breast cancer patients (78.6%), followed by those with retinoblastoma (14.3%) and testicular seminoma (7.1%). No likely pathogenic variants were detected.

In our study, we identified pathogenic variants in 10 out of 55 families (18.18%), with 6 of these families (60%) having more than one member exhibiting similar variants, thereby confirming their classification as hereditary cancer families3. Based on the total number of families analyzed, 10.9% (6 out of 55) of familial cancer cases are hereditary. Pathogenic variants have been identified in 14 individuals, affecting 8 distinct genes. Specifically, the pathogenic variants associated with breast cancer were identified in the BRCA1, BRCA2, MUTYH, PALB2, RAD51D, VHL, and ERCC4 genes. The contribution of BRCA (N = 5) and non-BRCA (N = 6) germline mutations in breast cancer patients with a family history was found to be nearly equivalent. Additional pathogenic variants were discovered in the RB1 and ERCC4 genes in patients with retinoblastoma and testicular seminoma, respectively. Furthermore, three additional pathogenic variants from the MUTYH and ERCC4 genes were identified in unaffected individuals, mirroring those found in their affected relatives. Other pathogenic variants were detected in unaffected individuals, including those in the SPINK1, ATM, and VHL genes. All ten pathogenic variants identified in both affected and unaffected individuals are classified as either high or moderate penetrance types (refer to Table 3).

The distribution of pathogenic variants across different clinical categories, including age at diagnosis, sex and types of cancer in family history, is presented in Table 4. Subjects affected by early-onset cancer (diagnosed at 40 years or younger) exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of pathogenic variants (7 out of 13 patients, or 53.8%) compared to those with late-onset cancer (7 out of 48 patients, or 14.6%). Among subjects with early-onset breast cancer, the BRCA gene mutation rate was 7.7% (1 of 13). The prevalence of pathogenic variants is insignificantly higher in affected males compared to females (40 vs. 21.4%), with all variants being non-BRCA genes. The frequency of pathogenic variants in subjects with a familial history of breast cancer was 24.4%, with a BRCA prevalence of 14.6%. Conversely, subjects with a family history of non-breast cancer predominantly exhibited non-BRCA mutations (95.0%). No significant result of sex with variants was observed.

Discussion

The study comprised a total of 61 cancer-affected participants and 98 unaffected family members from 55 families. Although the sample size is relatively small, this research constitutes a significant initial step in the exploration of hereditary cancer in Indonesia. Its novelty and regional pertinence enhance its impact. The most prevalent cancer type identified in this study was breast cancer, followed by ovarian cancer, retinoblastoma, and colon cancer. These findings align with GLOBOCAN data, which also identifies breast cancer as the most common cancer type in Indonesia6. In the group of affected individuals, 21.3% were 40 years of age or younger, with a predominant proportion (91.8%) being female. This data aligns with the findings of Stadler et al. (2023) in the United States, which reported a prevalence of early-onset cancer at 19.2%15.

In this investigation, the pathogenic gene variants associated with familial cancer were found in 10 out of 55 families (18.18%). These variants have been identified in 14 affected individuals, affecting 8 distinct genes. Previous study reported the prevalence of pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants in breast, ovarian, or colon/stomach cancer were 9.7, 13.4, and 14.8%, respectively16. Among these, 6 (60%) families exhibited more than two members with similar variants, thereby confirming their classification as hereditary cancer families. Based on the total number of families analyzed, we confirm that 10.9% (6 out of 55) of familial cancer cases are hereditary. Our findings are consistent with those of the National Cancer Institute and the Canadian Cancer Society, which have reported that the prevalence of hereditary cancer is estimated to range between 5 and 10%17,18.

The most frequently occurring pathogenic variant in affected individuals was BRCA2, followed by BRCA1, PALB2, ERCC4, RB1, MUTYH, RAD51D, and VHL. Notably, the pathogenic variant of the ERCC4 gene was identified in two distinct cancer types, breast cancer and testicular seminoma, across two different families. Some similar pathogenic variants were detected within a single family; for instance, BRCA1 was found in two family members (an affected mother with breast cancer and her unaffected daughter), BRCA2 in three family members (two affected siblings with breast cancer and one unaffected daughter), PALB2 in two affected individuals with breast cancer (mother and daughter), RB1 in two affected individuals with retinoblastoma (mother and son), and MUTYH in two family members (an affected mother with breast cancer and her unaffected daughter) from one family. This suggests the presence of hereditary gene variants in Indonesian familial cancer. Most pathogenic variants were predicted to result in truncated proteins (stop gained, frameshifts), with one missense mutation identified.

In families with a history of retinoblastoma, genomic screening was conducted on both affected and unaffected children, alongside the affected mother. The consensus report by the American Association of Ophthalmic Oncologists and Pathologists recommends genetic counseling and testing to assess the risk of retinoblastoma in children with a familial predisposition to the condition19. This approach aims to improve outcomes while reducing costs. Such evaluations should commence in families with an affected member due to the high probability of the disease being hereditary. Individuals with RB1 germline mutations are particularly susceptible to developing additional retinoblastoma tumors and other primary cancers throughout their lifetime19,20.

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation genes are implicated in hereditary cancer syndrome21. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, which function as tumor suppressor genes, substantially elevate the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. Individuals with BRCA1 mutations exhibit a higher risk of breast cancer compared to those with BRCA2 mutations. Our findings identified two breast cancer patients with BRCA1 and three with BRCA2 pathogenic variants, corroborating previous research that classifies BRCA1/2 mutations as pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants21.

The majority of gene variants identified in this study have been previously demonstrated to be closely associated with familial cancer occurrence. Yang et al. (2020) confirmed in a prior study conducted across 20 countries that a defect in the PALB2 gene increases the risk of familial breast cancer22. In addition to breast cancer, mutations in PALB genes are also linked to ovarian, pancreatic, and male breast cancers22. Research in the Czech Republic indicates that RAD51D mutations are associated with a high risk of ovarian cancer, with mutations in RAD51C and RAD51D present in 1% of ovarian cancer patients for each gene23. Pathogenic von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) germline variants elevate the risk of developing multiple benign and malignant neoplasms, including clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas (CNS-HB), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNET), pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PPGL), and kidney and pancreatic cysts24.

In addition to genes involved in homologous recombination repair pathways (BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and RAD51D), we identified pathogenic variants in the MUTYH and VHL genes. The MUTYH gene, which is responsible for repairing oxidative DNA damage, is associated with MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)25. This rare inherited condition leads to the formation of abnormal tissue growths, or polyps, within the body25. The MUTYH gene mutation is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, which can elevate the risk of polyp formation in the colon, rectum, stomach, and small intestine25. Our findings indicate that the MUTYH mutation, which is more prevalent in Asian breast cancer populations, is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer among its carriers26. A similar MUTYH mutation has been reported to confer platinum sensitivity in vitro, a standard chemotherapy regimen for ovarian cancer27, and has recently been proposed as a predictive biomarker for PARP inhibitor treatment28. The sensitivity of breast cancer patients carrying the germline pathogenic MUTYH mutation to other chemotherapies used in breast cancer treatment remains to be determined.

The Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene is a tumor suppressor gene implicated in human clear cell renal carcinoma29. Previous studies suggest a potential association between pathogenic VHL mutations and breast cancer, particularly in patients with lobular cancer29. Notably, VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma exhibits sensitivity to PARP inhibitors in vitro30. However, there are currently no specific guidelines for the clinical management of breast cancer in individuals with germline MUTYH and VHL mutations.

This study further verified that 24.4% of familial cancer cases with a history of breast cancer possess pathogenic variants. Previous research on breast cancer patients with a family history has reported a range of 12–28% for pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants when utilizing a multigene panel comprising 20 to 600 genes31. Despite employing a comprehensive panel of causal gene variants, the majority of breast cancer patients with a family history, specifically 70–80%, do not possess high- or moderate-penetrance genes32. Nonetheless, genetic counseling remains crucial, as a family history of cancer is still regarded as a significant risk factor33. The contribution of BRCA and non-BRCA germline mutations in breast cancer patients with a familial history was observed to be approximately equivalent. Consistent with our findings, other studies indicated that the contribution of BRCA and non-BRCA germline mutations in breast cancer patients with a family history is nearly equivalent16,34. Therefore, expanding the gene panel for breast cancer to include multiple genes, particularly PALB2, MUTYH, RAD51D, VHL, and ERCC4, may be advantageous. Additionally, in our study, young age or early onset of cancer was associated with a higher frequency of pathogenic variants. Consequently, young cancer patients with a family history may have an increased likelihood of harboring pathogenic variants.

We also identified pathogenic variants in unaffected individuals compared to their affected relatives, including SPINK1, ATM, and VHL. The mutated Serine Peptidase Inhibitor Kazal Type 1 (SPINK1) gene has been shown to induce cancer cell invasion in various human adenoma and carcinoma cells of the colon and breast through phosphoinositide-3-kinase, protein kinase C, and Rho-GTPases/Rho kinase-dependent pathways35. The presence of mutated SPINK1 is associated with a 12-fold increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer36. The Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) gene plays a role in the DNA damage response and has been linked to an increased risk and progression of several cancers, particularly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC), papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)37,38.

All ten pathogenic variants identified in both affected and unaffected individuals in this study are classified as either high or moderate penetrance types39. A comprehensive understanding of all genes examined in this study serves as a foundational resource for the development and implementation of personalized therapies targeting distinct tumor profiles. Genetic screening and counseling for patients with familial cancer, as well as for unaffected healthy family members, offer an alternative preventive strategy for assessing cancer risk, particularly in individuals with a family history of the disease40. Initially, identifying the causative gene(s) through multigene analysis in individuals with a cancer history, followed by a family segregation study, would have been more beneficial. However, despite the financial implications of multigene panel testing, we opted to conduct multigene testing on both cancer patients and their healthy relatives, alongside segregation analysis, due to the family’s recurrent cancer history. Notably, this study identified unique causal gene variants in healthy individuals that differed from those found in their affected relatives.

This study represents as first study in the analysis of familial linkage variants associated with hereditary cancer within the Indonesian population. Despite the limited number of familial cancer participants, this research constitutes a significant initial step in the exploration of hereditary cancer in Indonesia. Our findings reveal several pathogenic variants, including BRCA1/2, PALB2, MUTYH, RAD51D, VHL, and ERCC4, which are linked to an elevated risk of hereditary cancer among Indonesian families. Additional pathogenic variants were identified in individuals from the families who were unaffected. Consequently, genomic screening and counseling for patients with familial cancer and their relatives emerge as promising strategies for prevention and treatment. These approaches also facilitate the development of personalized cancer treatment plans tailored to individual patient conditions. The feasibility of implementing genomic screening and counseling in Indonesia is on the rise, as evidenced by the government’s national genomic screening program and the availability of individual screenings in select hospitals and private laboratories. However, these services are predominantly confined to major urban centers and are not covered by national insurance, which limits public awareness of their importance. Therefore, extending the reach of genomic screening and counseling services across all regions of Indonesia remains a formidable challenge for the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

WHO. Global cancer burden growing, amidst mounting need for services. Available from https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services. (2024) Accessed 11 May 2024

Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 10(8), 789–799. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1087 (2004).

Institute, N. C. Dictionary of cancer terms. Available from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/familial-cancer. (2025) Accessed 21 Oct 2025

Hemminki, K. et al. Familial risks and proportions describing population landscape of familial cancer. Cancers (Basel) 13(17), 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13174385 (2021).

Puspitaningtyas, H., Espressivo, A., Hutajulu, S. H., Fuad, A. & Allsop, M. J. Mapping and visualization of cancer research in Indonesia: A scientometric analysis. Cancer Control 28, 10732748211053464. https://doi.org/10.1177/10732748211053464 (2021).

Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F., Laversanne, M., Colombet, M., Mery, L., Piñeros, M., Znaor, A., Soerjomataram, I., & Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available from https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/360-indonesia-fact-sheet.pdf. (2024) Accessed 11 May 2024

Hemminki, K., Li, X., Försti, A. & Eng, C. Are population level familial risks and germline genetics meeting each other?. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 21(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-023-00247-3 (2023).

Imyanitov, E. N. et al. Hereditary cancer syndromes. World J. Clin. Oncol. 14(2), 40–68. https://doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v14.i2.40 (2023).

Ashour, M. & Ezzat Shafik, H. Frequency of germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in ovarian cancer patients and their effect on treatment outcome. Cancer Manag. Res. 11, 6275–6284. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.S206817 (2019).

NCCN. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology, breast cancer. Version 4.2022. . Retrieved from https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. (2022)

Evans, D. G. & Ingham, S. L. Reduced life expectancy seen in hereditary diseases which predispose to early-onset tumors. Appl. Clin. Genet. 6, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/tacg.S35605 (2013).

Jatoi, I. Risk-reducing options for women with a hereditary breast cancer predisposition. Eur. J. Breast Health 14(4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2018.4324 (2018).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526(7571): 68–74 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393(2015)

Amendola, L. M. et al. Variant classification concordance using the ACMG-AMP variant interpretation guidelines across nine genomic implementation research studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107(5), 932–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.09.011 (2020).

Stadler, Z. K. et al. Redefining early-onset cancer and risk of hereditary cancer predisposition. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 10510. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.10510 (2023).

Susswein, L. R. et al. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variant prevalence among the first 10,000 patients referred for next-generation cancer panel testing. Genet. Med. 18(8), 823–832. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.166 (2016).

National Cancer Institute. The Genetics of Cancer. Available from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics#:~:text=Up%20to%2010%25%20of%20all,of%20getting%20cancer%20is%20increased. (2024)

Canadian Cancer Society. Check your family history. Available from https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/reduce-your-risk/check-your-family-history#:~:text=When%20there%20is%20cancer%20in,than%20one%20type%20of%20cancer. (2025)

Skalet, A. H. et al. Screening children at risk for retinoblastoma: consensus report from the American association of ophthalmic oncologists and pathologists. Ophthalmology 125(3), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.001 (2018).

MacCarthy, A. et al. Second and subsequent tumours among 1927 retinoblastoma patients diagnosed in Britain 1951–2004. Br. J. Cancer 108(12), 2455–2463. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.228 (2013).

Li, S. et al. Cancer Risks Associated With BRCA1 and BRCA2 Pathogenic Variants. J. Clin. Oncol., 40(14): 1529–1541 https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.21.02112(2022)

Yang, X. et al. Cancer risks associated with germline PALB2 pathogenic variants: An international study of 524 families. J. Clin. Oncol. 38(7), 674–685. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.19.01907 (2020).

Soukupová, J. et al. Germline mutations in RAD51C and RAD51D and hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer. Klin. Onkol. 34(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.48095/ccko202126 (2021).

Shepherd, S. T. C., Drake, W. M. & Turajlic, S. The road to systemic therapy in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: Are we there yet?. Eur. J. Cancer 182, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2022.12.011 (2023).

Garutti, M. et al. Hereditary cancer syndromes: A comprehensive review with a visual tool. Genes (Basel) 14(5), 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14051025 (2023).

Rennert, G. et al. MutYH mutation carriers have increased breast cancer risk. Cancer 118(8), 1989–1993. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26506 (2012).

Chen, C. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of breast cancers characterizes germline-somatic mutation interactions mediating therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cell Discov. 9(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-023-00614-3 (2023).

Hutchcraft, M. L., Gallion, H. H. & Kolesar, J. M. MUTYH as an emerging predictive biomarker in ovarian cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 11(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010084 (2021).

Rana, H. Q. et al. Pathogenicity of VHL variants in families with non-syndromic von Hippel-Lindau phenotypes: An integrated evaluation of germline and somatic genomic results. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 64(12), 104359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104359 (2021).

Scanlon, S. E., Hegan, D. C., Sulkowski, P. L. & Glazer, P. M. Suppression of homology-dependent DNA double-strand break repair induces PARP inhibitor sensitivity in VHL-deficient human renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 9(4), 4647–4660. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23470 (2018).

O’Leary, E. et al. Expanded gene panel use for women with breast cancer: identification and intervention beyond breast cancer risk. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24(10), 3060–3066. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5963-7 (2017).

Fan, X. et al. Penetrance of breast cancer susceptibility genes from the eMERGE III network. JNCI Cancer Spectr. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkab044 (2021).

van Marcke, C., De Leener, A., Berlière, M., Vikkula, M. & Duhoux, F. P. Routine use of gene panel testing in hereditary breast cancer should be performed with caution. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 108, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.10.008 (2016).

Mittal, A. et al. Profile of pathogenic mutations and evaluation of germline genetic testing criteria in consecutive breast cancer patients treated at a North Indian tertiary care center. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29(2), 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10870-w (2022).

Gouyer, V. et al. Autocrine induction of invasion and metastasis by tumor-associated trypsin inhibitor in human colon cancer cells. Oncogene 27(29), 4024–4033. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2008.42 (2008).

Enjuto, D. T., Herrera, N., C, J. C., Ramos Bonilla, A., Llorente-Lázaro, R., González Guerreiro, J., & Castro-Carbajo, P. Hereditary Pancreatitis Related to SPINK-1 Mutation. Is There an Increased Risk of Developing Pancreatic Cancer?. J. Gastrointest. Cancer, 54(1): 268–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00729-4(2023)

Xu, L., Morari, E. C., Wei, Q., Sturgis, E. M. & Ward, L. S. Functional variations in the ATM gene and susceptibility to differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97(6), 1913–1921. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-3299 (2012).

Petersen, L., & Bebb, D. G. P1.02–086 ATM mutations in lung cancer correlate to higher mutation rates: topic: other mutations in thoracic malignancies. J. Thoracic Oncol. 12(1): S541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.670(2017)

Pal, M., Das, D. & Pandey, M. Understanding genetic variations associated with familial breast cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 22(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-024-03553-9 (2024).

Schienda, J. & Stopfer, J. Cancer genetic counseling-current practice and future challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a036541 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all oncologists, family cancer patients, and families who cooperatively participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, Kedaireka Matching Fund Grant number 23/E1/PPK/KS.03.00/2023, and Faculty of Medicine Universitas Diponegoro Research Grant number 3081/UN7.5.4.2/PP/2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM prepared the conceptualization. MM, EKSL, CHNP, YI, ZN, RTS, and PS collected data. MM, CHNP, ZN, and PS validated the data. EKSL and YWP analyzed and interpreted the data. MM wrote the original draft manuscript. EKSL, YWP, YI, ZN, ET, and ARHU reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the World Medical Association Ethics Code (Declaration of Helsinki). All research procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. The Health Research Ethics Committee issued the ethical approval, Dr. Kariadi Central General Hospital Semarang, number 1489/EC/KEPK-RSDK/2023.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects before conducting the study.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muniroh, M., Prihharsanti, C.H.N., Limijadi, E.K.S. et al. Pathogenic variants in affected and unaffected individuals from Indonesian familial cancer: a multigene panel analysis. Sci Rep 15, 43981 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27710-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27710-6