Abstract

This study investigated the use of salivary and serum chromogranin A (CgA) as biomarkers of acute stress and pain perception during the initial phase of fixed orthodontic treatment. Twenty-five patients aged 15–25 years, scheduled for non-extraction therapy with fixed appliances, were enrolled, and unstimulated saliva as well as venous blood samples were collected at baseline, 24 h, 72 h, and one month after appliance placement. Pain levels were measured using a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS). Both salivary and serum CgA levels showed a significant rise at 24 h compared to baseline, followed by a gradual return towards baseline by one month. Pain intensity peaked at 24 h (mean 8.07 ± 1.18) and decreased at 72 h and one month, with female participants reporting higher pain scores than males at 24 h. No significant gender differences were observed in CgA levels. The similar patterns of biomarker increase and self-reported pain indicate that CgA reflects the short-term stress response linked to appliance placement. Monitoring salivary CgA could thus offer clinicians a non-invasive method to predict discomfort, facilitate early interventions, and help patients adapt to orthodontic treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fixed orthodontic appliances remain the gold standard for achieving precise tooth movement, correcting complex malocclusions, and maintaining long-term occlusal stability1,2. However, the initial stages of treatment are often associated with discomfort and psychological stress, which can affect daily activities, reduce patient satisfaction, and compromise compliance1,3. Pain typically peaks within 24 h of appliance placement and gradually subsides over several days1,4, nevertheless its intensity varies among individuals and is influenced by both physiological and psychological factors.

Stress during orthodontic treatment activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) system4, resulting in the release of stress-related biomarkers such as cortisol, alpha-amylase, and chromogranin A (CgA)5,6. Unlike cortisol, which reaches its peak approximately 20–30 min after exposure to a stressor, salivary CgA increases almost immediately due to sympathetic activation4,5. Its concentration remains elevated for the duration of the stressor and begins to decrease only after the stressor is no longer present. The subsequent reduction in CgA follows its reported salivary half-life of approximately 15–20 min, with values generally returning toward baseline within 30–40 min after termination of the stimulus4,7.

Salivary measurement of CgA provides a non-invasive, repeatable method for monitoring stress8 and it has been studied in various dental settings9,10. Salivary CgA rises during routine dental procedures, including high-speed turbine use and around local anaesthesia, with short-interval post-procedure sampling confirming these changes7. Nevertheless, serum analysis remains the gold standard for systemic assessment6,11. Salivary CgA shows a disease-severity gradient—higher in gingivitis than in health, and highest in periodontitis6. Stage-based analyses likewise report the greatest concentrations of salivary CgA in stage III periodontitis compared with milder categories12. Outside dental settings, plasma/serum CgA correlates with psychosocial stress in healthy populations, including positive associations with anxiety/depression and with chronic work-stress indices13,14. Since serum sampling is inherently invasive and may induce stress itself, understanding whether salivary CgA can serve as a reliable alternative is clinically relevant. Demonstrating comparable trends between salivary and serum CgA could support the use of saliva as a non-invasive, patient-friendly biomarker. Furthermore, the relationship between these biomarkers and patient-reported pain is examined. Understanding these dynamics could help clinicians anticipate periods of peak discomfort and implement timely interventions to improve the patient experience.

Few studies have concurrently tracked salivary and serum CgA dynamics over the course of orthodontic treatment1,6. At least one longitudinal orthodontic cohort has directly measured salivary CgA during treatment and reported no significant change across follow-ups despite pain reports1. Earlier orthodontic studies have relied mainly on salivary CgA; by measuring both salivary and serum CgA alongside pain, we assess whether local and systemic stress signals move in parallel during the early orthodontic phase.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the temporal changes in salivary and serum CgA levels during the early phase of fixed orthodontic treatment and to investigate their relationship with perceived pain intensity.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

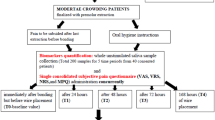

This longitudinal observational study was conducted at Al-Hadi University’s College of Dentistry. The sample size was determined using G*Power version 3.1.9.4, with an effect size of 0.30, an alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 90%, applying repeated measures ANOVA for within-group factors. The minimum required sample was 20 participants. To account for potential dropouts, 25 patients (14 females and 11 males) who met the eligibility criteria were recruited. Sample collection took place between November 2024 and February 2025. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Al-Hadi University, College of Dentistry (Approval No. HD112403, dated 13 November 2024). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment and sample collection.

Inclusion criteria

Healthy individuals aged 15 to 25 years with mild dental crowding (< 4 mm), selected for non-extraction fixed orthodontic treatment using conventional metal brackets on both upper and lower arches, were included.

Participants were excluded if they had systemic disease, craniofacial anomalies, pregnant or lactating, or were current nicotine users. To minimise acute confounding of CgA, participants who reported significant emotional or physical stress (e.g., examinations, personal trauma, acute illness) within 24 h before any study visit were excluded from biomarker sampling. This was done to minimise confounding influences on salivary and serum Cg A levels, which are known to be highly sensitive to acute psychological or physiological stress, and could otherwise mask or exaggerate the effects attributed to orthodontic treatment.

Data collection and study visits

All bonding procedures were performed by a single orthodontist. Both the upper and lower arches were bonded in a single appointment during the baseline visit (T0). Before participation, patients were informed about the possibility of experiencing mild to moderate discomfort following appliance placement. They were instructed not to take any analgesics during the observation period to avoid interference with pain perception and stress biomarker evaluation unless they felt severe pain. However, participants were clearly informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences to their ongoing orthodontic treatment. No participants reported using any method of pain relief, and none withdrew from the study. Biological sampling was performed at all four study time points (T0: before bonding; T1: 24 h; T2: 72 h; T3: one month after bonding). T1 and T2 were selected to capture the well-described acute pain peak (24–48 h) and early decline (3–7 days) respectively, while T3 (1 month) coincided with the end of the early lag phase of tooth movement (20–30 days) and the routine pre-adjustment interval (4–6 weeks)15,16,17,18. At each visit, the sequence of procedures was as follows: completion of the VAS pain questionnaire (T1–T3 only), followed by collection of unstimulated whole saliva and then venous blood sampling. Participants were instructed to abstain from eating, drinking (except water), brushing their teeth, or using mouthwash for at least one hour before each sampling session.

Sample collection and processing

Saliva and blood samples were collected at each visit. 3 ml of saliva was collected between 9:00 and 11:00 AM using the passive drooling method into sterile test tubes, which were immediately placed in an ice box. The samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to remove cellular debris, and the supernatant was aliquoted into sterile microcentrifuge tubes and stored at − 20 °C until analysis.

Approximately 5 mL of venous blood was collected into serum separator tubes. This volume was selected to obtain sufficient serum following clot retraction and centrifugation to permit the required 1:20 dilution and duplicate ELISA measurement of Chromogranin A, according to the manufacturer’s instructions19. The blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting serum was aliquoted and stored at − 20 °C. Samples from the same participant were processed within the same analytical run to minimise inter-assay variability.

Biochemical analysis

CgA concentrations in saliva and serum were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Labour Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). Samples were gently mixed and analysed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and CgA concentrations were determined from the standard curve. With n = 25, a single laboratory session (~ 2.5–3 h from first incubation to plate reading) covered all samples at a given time point for a single biofluid (saliva or serum), allowing for same-day turnaround and making salivary CgA a workable, time-efficient option in routine settings.

Pain assessment

Pain intensity while wearing a fixed orthodontic appliance was assessed using a continuous 10-centimetre Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Participants were instructed to mark a point on a horizontal line ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) to indicate their perceived level of discomfort. The distance (in centimetres) from the “no pain” anchor to the participant’s mark was measured with a ruler, yielding a continuous score from 0.0 to 10.0. Pain was evaluated at T1, T2, and T3 following orthodontic bonding. The VAS questionnaire was administered before collecting saliva and blood samples at each time point to minimise bias. No pain assessment was performed at T0, as this visit occurred before appliance bonding. Participants received consistent instructions on how to complete the pain scale to ensure uniform self-reporting.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables and presented as means and standard deviations. Changes in salivary and serum CgA levels across the four time points (T0, T1, T2, and T3) and pain scores across T1, T2, and T3 were evaluated using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). When appropriate, the Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. The relationship between CgA concentrations and pain intensity was assessed using Spearman’s correlation analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 25 participants completed the study protocol and were included in the final analysis. The collected data were utilised to evaluate changes in pain perception and CgA levels in both saliva and serum over time in response to the placement of fixed orthodontic appliances. The demographic characteristics of the study sample revealed that out of 25 participants, 14 were females (56.0%) and 11 were males (44.0%), with a mean age of 18.16 ± 3.09 years and an age range of 15 to 24 years.

Both salivary and serum CgA levels significantly increased following the placement of the orthodontic appliance. The highest concentrations were observed at 24 h (T1), followed by a gradual decline at 72 h (T2) and near-baseline levels by one month (T3), as shown in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 1.

Salivary chromogranin A (CgA) levels during early orthodontic treatment. Line graph showing mean salivary CgA concentrations at baseline (T0), one week (T1), and one month (T2) after initiation of fixed orthodontic treatment. Error bars represent mean ± s.d. (n = 25). Statistical significance was assessed using repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Pain scores, assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS), demonstrated a declining pattern following appliance placement. The highest pain levels were recorded at 24 h (T1), followed by a significant reduction at 72 h (T2), and minimal pain by one month (T3), as detailed in Table 2 and visualised in Fig. 2.

A gender-based analysis of salivary and serum Chromogranin A (CgA) levels revealed no statistically significant differences between male and female participants at any time point (T0–T3). Both groups exhibited a similar pattern, with concentrations peaking at 24 h (T1) and then declining thereafter. However, salivary CgA levels were slightly higher in females at the peak of stress. These trends are illustrated in Fig. 3, which shows the progression of salivary and serum CgA levels divided by gender.

In contrast, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores showed a statistically significant difference at T1, with females reporting higher pain intensity than males (p = 0.005). Although pain scores decreased in both groups at T2 and T3, females consistently reported higher values throughout the follow-up period. The gender-specific trends in pain perception are presented in Fig. 4.

Discussion

CgA, a recognised marker of neuroendocrine activity, exhibited a distinct pattern in both saliva and serum following the placement of orthodontic appliances. Concentrations rose significantly at 24 h post-bonding (T1), followed by a steady decline at 72 h (T2) and one month (T3). This finding aligns with previous studies indicating elevated CgA levels in response to acute psychological and procedural stressors7. The initial increase may reflect neuroendocrine activation secondary to the mechanical stimulation of periodontal tissues, the release of inflammatory mediators, and anticipatory psychological stress related to the application of orthodontic force7,20. In our study, peak serum CgA levels (mean 4.87 ± 1.01 pmol/mL at T1) exceeded the manufacturer’s stated upper reference limit of ≈ 2.04 pmol/mL, indicating a pronounced systemic stress response. For saliva, although the manufacturer provides a measuring range of 0.14–33.33 pmol/mL, no clinical reference interval is established; therefore, changes were interpreted relative to baseline. Salivary CgA increased from a baseline of 0.48 ± 0.10 pmol/mL to a peak of 3.52 ± 0.66 pmol/mL at T1. While both biofluids displayed a similar response pattern, salivary CgA remains a clinically feasible and less invasive alternative for monitoring treatment-related stress, particularly in longitudinal orthodontic studies.

Pain intensity measured by VAS was highest at 24 h after appliance placement, with a consistent reduction observed at 72 h and one month. These findings align with prior literature describing the typical pattern of orthodontic pain, which begins shortly after bonding, peaks at 24 h, and progressively declines as patients physiologically adapt to the application of mechanical force18,21. The inflammatory response in the periodontal ligament, involving the release of prostaglandins and other mediators, is thought to underlie this time-dependent course of pain2. The declining pain levels suggest a combination of tissue adaptation and improved patient coping during the early stages of treatment.

Significant gender differences were observed in pain perception, particularly at 24 h (T1), with female patients reporting higher VAS scores than their male counterparts. This aligns with prior studies indicating that females are more likely to report greater pain intensity during orthodontic treatment, especially during the initial application of force22. The disparity may stem from biological, hormonal, and psychosocial influences, including heightened pain sensitivity, hormonal fluctuations, and variations in emotional expression and coping strategies23. Although CgA levels were consistently higher in females across time points, these differences were not statistically significant; however, they may reflect a tendency towards increased sympathetic reactivity in female patients24.

To reduce variability and ensure sample homogeneity, only patients exhibiting mild crowding (< 4 mm arch length discrepancy) were incorporated into this investigation. Nonetheless, the severity of malocclusion is a recognised factor that influences pain perception during the initial phases of orthodontic treatment. According to Keshavarz et al., patients with more severe crowding endure significantly greater and more prolonged pain, especially within the first 24 h following appliance activation. This is attributed to increased tooth displacement, elevated tissue pressure, and intensified inflammation during the alignment process. The study further indicated that patients with severe crowding not only attained higher peak pain levels but also encountered delayed pain alleviation in comparison to those with mild or moderate crowding25.

While our findings showed no statistically significant differences in CgA levels between genders, a recent study reports a comparable pattern: a simulation-based endoscopic training study detected no apparent gender effect on salivary CgA reactivity26, and another study of healthy adults observed higher bedtime values in men but no gender difference after waking27. In our sample, both salivary and serum CgA levels rose from baseline to 24 h and then declined; however, females reported higher pain scores on the VAS. These differences may be influenced by psychological traits not measured in this study, such as pain catastrophizing or dental anxiety. Previous research suggests that such factors can significantly amplify perceived pain, even when physiological markers remain comparable. Incorporating validated psychological assessments into future studies could help clarify the interplay between subjective pain experience and objective stress biomarkers1.

The biological responses observed in this study can be attributed to the complex interaction between mechanical stimulation, inflammatory pathways, and neuroendocrine regulation. The application of orthodontic force initiates a cascade of cellular and molecular events within the periodontal ligament, including the release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, cytokines, and neuropeptides, which contribute to nociceptor sensitisation and pain perception2. Simultaneously, the stress associated with appliance placement activates the sympathetic–adrenal medullary axis, resulting in an increased release of catecholamines and co-secretory proteins such as CgA28. In addition to physiological mechanisms, psychological factors—such as anxiety, fear of dental procedures, and individual pain coping strategies—may further amplify the perception of discomfort, particularly in the early stages of treatment29. The parallel changes observed in CgA concentrations and VAS scores support the hypothesis that orthodontic treatment elicits an integrated psychobiological stress response, rather than a purely mechanical or emotional experience.

A limitation of the study is the absence of long-term follow-up beyond one month, which restricts the understanding of how CgA and pain responses evolve with subsequent orthodontic activations. Pain was not measured at baseline (T0) as this visit preceded appliance bonding; VAS assessment was initiated at T1 to quantify procedure-related discomfort rather than pre-procedural expectations. Additionally, the study did not include psychological profiling or anxiety scales, which could have provided more profound insight into individual variability in pain perception and stress reactivity.

Tracking salivary CgA provides orthodontists with a practical way to better understand how patients respond to treatment stress, especially in the first few days after appliance placement. By identifying when stress and pain are likely to peak, clinicians can more effectively time interventions, such as reassurance, pain control, or softer food guidelines. In future, these biomarkers could help determine when to schedule activations, making treatment more personalised and comfortable for patients.

Conclusion

Fixed orthodontic treatment triggers a short-term neuroendocrine response, reflected by transient elevations in salivary and serum CgA levels, which align with peak pain intensity at 24 h. This correlation supports the utility of CgA as a sensitive, non-invasive biomarker of acute orthodontic stress. Although CgA levels did not differ significantly between genders, females consistently reported more pain, pointing to the likely influence of psychological factors. Tracking salivary CgA could help clinicians better understand patient experiences and tailor early-phase care for greater comfort.

Data availability

The anonymised datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17141636](https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17141636).

References

Canigur Bavbek, N. et al. Assessment of salivary stress and pain biomarkers and their relation to self-reported pain intensity during orthodontic tooth movement: a longitudinal and prospective study. J. Orofac. Orthop. 83, 339–352 (2022).

Kloukos, D. et al. Impact of fixed orthodontic appliances on blood count and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 164, 351–356 (2023).

Silva Andrade, A. et al. Evaluation of stress biomarkers and electrolytes in saliva of patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment. Minerva Stomatol. 67, 172–178 (2018).

Jantaratnotai, N., Rungnapapaisarn, K., Ratanachamnong, P. & Pachimsawat, P. Comparison of salivary cortisol, amylase, and chromogranin A diurnal profiles in healthy volunteers. Arch. Oral Biol. 142, 105601 (2022).

Nakane, H. et al. Salivary chromogranin a as an index of psychosomatic stress response. Biom Res. 19, 401–406 (1998).

Lee, Y. H., Suk, C., Shin, S., Il & Hong, J. Y. Salivary cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone, and chromogranin A levels in patients with gingivitis and periodontitis and a novel biomarker for psychological stress. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1130823 (2023).

Vora, K. M. et al. Quantification of salivary chromogranin A levels during routine dental procedures in children: an in vivo study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 17, 585–590 (2024).

Develioglu, H., Korkmaz, S., Dundar, S. & Schlagenhauf, U. Investigation of the levels of different salivary stress markers in chronic periodontitis patients. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 10, 514–518 (2020).

Diaz, M., Bocanegra, O., Teixeira, R., Soares, S. & Espindola, F. Response of salivary markers of autonomic activity to elite competition. Int. J. Sports Med. 33, 763–768 (2012).

Albagieh, H. et al. Evaluation of salivary diagnostics: Applications, Benefits, Challenges, and future prospects in dental and systemic disease detection. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.77520 (2025).

Miyakawa, M. et al. Salivary chromogranin A as a measure of stress response to noise. Noise Health. 8, 108–112 (2006).

Soysal, F., Isler, S. C., Guney, Z., Akca, G. & Unsal, B. Salivary chromogranin a levels in periodontal health status: a cross-sectional study evaluating clinical and psychological associations. BMC Oral Health. 25, 1536 (2025).

Li, Y., Song, Y., Dang, W., Guo, L. & Xu, W. The associations between anxiety/depression and plasma chromogranin A among healthy workers: results from EHOP study. J. Occup. Health. 62, e12145 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Associations between chronic work stress and plasma chromogranin A/catestatin among healthy workers. J Occup. Health 64 (2022).

Feller, L. et al. Periodontal biological events associated with orthodontic tooth movement: the biomechanics of the cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix. Sci. World J. 2015, 894123 (2015).

Lin, W. et al. Factors associated with orthodontic pain. J. Oral Rehabil. 48, 1135–1143 (2021).

Gyawali, R., Pokharel, R. & Giri, J. Emergency appointments in orthodontics. APOS Trends Orthod. 9, 40–43 (2019).

Ali, D., Abdal, H. & Alsaeed, M. Comparison of self-rated pain and salivary alpha-amylase and cortisol levels during early stages of fixed orthodontic and clear aligner therapy. Acta Odontol. Scand. 81, 627–632 (2023).

Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG. Chromogranin A ELISA: Instructions for Use (2024).

Pantsulaia, I., Orjonikidze, N., Kvachadze, I., Mikadze, T. & Chikovani, T. Influence of different orthodontic brackets on cytokine and cortisol profile. Med. (B Aires). 59, 566 (2023).

Topal, R. Perception of pain during initial fixed orthodontic treatment. Int. Dent. Res. 11, 62–66 (2021).

Gupta, S. P., Rauniyar, S., Prasad, P. & Pradhan, P. M. S. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of different methods on pain management during orthodontic debonding. Prog Orthod. 23, 14 (2022).

Büyükbayraktar, Z. Ç. & Doruk, C. Dental anxiety and fear Levels, patient Satisfaction, and quality of life in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment: is there a relationship? Turk. J. Orthod. 34, 234–241 (2021).

Xie, L., Ma, Y., Sun, X. & Yu, Z. The effect of orthodontic pain on dental anxiety: a review. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 47, 32–36 (2023).

Keshavarz, S., Masoumi, F., Abdi, I. & Bani Adam, M. Research paper: relationship between the severity of tooth crowding and pain perception at the beginning of fixed orthodontic treatment in a population of Iranian patients. J. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. Pathol. Surg. 8, 7–13 (2020).

Georgiou, K. et al. Saliva stress biomarkers in ERCP trainees before and after familiarisation with ERCP on a virtual simulator. Front. Surg. 11 (2024).

Taniguchi, K. & Seiyama, A. Salivary chromogranin a reflects autonomic regulation during wake to sleep and sleep to wake transitions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 49, 48 (2025).

Valdiglesias, V. et al. Is salivary chromogranin A a valid psychological stress biomarker during sensory stimulation in people with advanced dementia? J. Alzheimer’s Disease. 55, 1509–1517 (2016).

Curto, A., Alvarado-Lorenzo, A., Albaladejo, A. & Alvarado-Lorenzo, A. Oral-Health-Related quality of life and anxiety in orthodontic patients with conventional brackets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 10767 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Hind H. Enad, Noor Ayuni Ahmad Shafiai. Methodology: Riyam Haleem, Hind H. Enad. Investigation: Hind H. Enad, Riyam Haleem. Data Curation: Hind H. Enad. Writing – Original Draft: Hind H. Enad. Writing – Review & Editing: Noor Ayuni Ahmad Shafiai. Supervision: Noor Ayuni Ahmad Shafiai. Visualisation: Noor Ayuni Ahmad Shafiai. Patient Selection and Criteria Design: Hind H. Enad, Riyam Haleem.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Al-Hadi University, College of Dentistry (Approval No. HD112403, dated 13 November 2024).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Enad, H.H., Haleem, R. & Shafiai, N.A.A. Salivary and serum chromogranin A as biomarkers of acute stress during early fixed orthodontic treatment: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep 16, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30275-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30275-z