Abstract

Infrared stealth materials that are lightweight and offering effective thermal camouflage are increasingly needed for advanced defense and sensing applications. Core-shell polymeric composites exhibit high performance thanks to strong interfacial interaction, multiple absorption mechanisms, and low density. This research presents a successful attempt at the preparation of lightweight infrared (IR) stealth polymeric core-shell composite material. The mechanism for thermal camouflage is based on absorbing the incoming thermal signals and then emitting them outside the atmospheric windows (wavelengths of 5–8 μm and 8–14 μm) via a broadband absorption/emission mechanism. Novel core-shell composite materials were prepared, using the in situ polymerization method to form a a shell of polyaniline (PANI) with two types of core materials, poly acrylic acid salt (PAAS) and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) with PANI weight ratios of 10%, 15%, and 20%. Additionally, physical mixture of PANI and PAAS were also tested to highlight the role of the microstructure of the material in the camouflage performance. The prepared samples were characterized structurally and morphologically using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, contact angle measurement, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)) and functionally, by measuring the specific electrical conductivity and thermal imaging of the samples. The findings show that the physical mixture samples did not work as stealth materials, while the two prepared composite materials had promising camouflage properties, which correlates with the proposed stealth mechanism. It is found that the composite material of PANI@PAAS gives better camouflage properties than PANI@PAN. Finally, the performance of the prepared composite material PANI@PAAS was superior to that of recently reported hybrid composite polymer-ceramics materials, that have relatively high density. In terms of thermal differences, achieving ΔT = 0 °C at 38 °C. Therefore, PANI@PAAS holds promise for infrared stealth applications that require lightweight and flexibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the development of advanced materials for IR camouflage has become increasingly critical due to the rapid advancements in IR detection technologies. Multiple camouflage mechanisms are crucial for the vital applications of IR manipulating materials. Radiative cooling is the use of materials that passively emit IR radiation in the atmospheric transparency window (8–13 μm) to match ambient thermal signatures, thereby dissipating heat efficiently without active cooling systems. This approach leverages selective emissivity to blend with the environment without active cooling systems. Wave-guiding approaches involve engineered structures, such as photonic crystals or metamaterials, that manipulate IR radiation propagation. These structures guide or trap IR waves along specific paths, minimizing reflection or emission toward detectors. By controlling the directionality and absorption of IR light, wave-guiding techniques suppress thermal signatures, effectively “hiding” objects within complex backgrounds at infrared wavelengths. Building upon the previous definitions, our approach merges both radiative cooling and the engineered structure from the waveguiding approach, so we can benefit from the advantages of both approaches. Among the different mechanisms, the atmospheric attenuation of infrared radiation, which has broad recent applications, depends largely on the wavelength of the radiation, the temperature, and the composition of the medium. The infrared spectrum lies in the range 0.77–1000 μm. The transmittance of the atmosphere is large in the wave windows of 3–5 μm and 8–12 μm, so only those two wave windows, known as atmospheric windows are used for monitoring and tracking. The atmospheric attenuation of infrared radiation is large in the wave ranges outside the tracking windows due to the absorption and scattering by carbon dioxide and water1. As highlighted by Fan et al., traditional methods of thermal camouflage are becoming less effective2, necessitating the exploration of novel materials such as two-dimensional nanomaterials like graphene and MXenes, which exhibit IR camouflage characteristics and tunable optoelectronic properties. Similarly, Wang et al. have demonstrated that coatings utilizing CeO2 fillers modified with polyethylene glycol 400 show significant promise for high-temperature IR stealth applications3. Beyond conventional materials, there are increasing demands for designing dyes with specific pigment combinations to match the reflectance properties of natural foliage in both visible and near-infrared regions, offering solutions tailored to environmental blending4.

Recent innovations in textile composites have also been explored, as noted by Su et al.4 who developed IR camouflage textiles incorporating phase change microcapsules and copper powder, achieving good camouflage performance in the 2–22 μm band while effectively regulating temperature. Meanwhile, Kang et al.5 introduced a tunable thermal emitter based on metal-insulator-metal plasmonic metamaterials integrated with phase-change material Ge2Sb2Te5, enabling dynamic control of thermal radiation across a broad wavelength range. In another study, Ahmad et al.6 synthesized alginate aerogel-polyester nonwoven composites with significantly reduced thermal diffusivity, showcasing their potential for thermal clothing applications. Further expanding the scope of adaptive IR camouflage, Wu et al.7 proposed smart thermal control coatings using CaF2@VO2 core-shell microspheres, demonstrating thermal camouflage properties. Sun et al.8 complemented these findings by designing electrochromic devices based on multilayer graphene thin films, achieving modulation of thermal radiation within seconds. Additionally, Bu et al.9 reviewed bio-inspired adaptive camouflage strategies, underscoring the need for continuous innovation to counter advanced detection techniques. Inspired by biological systems, Bu et al.9 developed adaptive IR-reflecting platforms mimicking cephalopod skin, offering dynamic tunability and robust performance.

Building upon these advancements, this study introduces a novel lightweight core-shell polymeric composite featuring an innovative IR stealth technology to overcome the limitations of existing camouflage materials. Specifically, we investigated the synthesis of two core-shell variants, with polyaniline (PANI) as the shell and either sodium polyacrylate (PAAS) or polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as the core, at PANI weight ratios of 10%, 15%, and 20%. We also examined the impact of core-shell morphology—compared to simple physical mixtures of the polymers—on IR camouflage performance. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first exploration of an all-organic core-shell IR camouflage material incorporating a conductive polymer for such applications. We propose and experimentally validate a new camouflage mechanism that enables superior thermal management and low IR signatures, while offering advantages in lightweight design, cost-effectiveness, and scalability to meet the demands of modern defense and surveillance systems.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Ammonium persulfate (98% purity, analytical grade), Sodium hydroxide (99% purity, lab grade), Prop-2-enoic acid (99% purity, lab grade), Propan-2-ol (99% purity, lab grade), propan-2-one (99.5% purity, analytical grade), and Prop-2-enenitrile (99% purity, lab grade) were manufactured by Panreac, Spain. Potassium persulfate (98% purity, analytical grade) was manufactured by The British House LTD., England. Anilinium chloride (98% purity, synthesis grade), and hydrochloric acid (37% purity, analytical grade) were manufactured by Merck, Germany.

Preparation and synthesis techniques

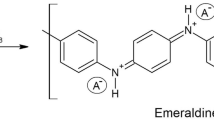

Polyaniline

The preparation of PANI was according to the IUPAC technical report10. Briefly, anilinium chloride (0.20 mol) and ammonium persulfate (0.25 mol) were separately dissolved in distilled water using two 500 mL volumetric flasks, with sonication in a T-660/H Elma® ultrasonic bath. The solutions were then mixed in a 2 L beaker and stirred for 24 h. The resulting polyaniline (PANI) was filtered in three batches using a WP6122050 Pyrex Buchner funnel connected to a BOECOR-400 vacuum pump. Each batch was washed sequentially with 200 mL of 0.02 M hydrochloric acid and 0.02 M acetone (propan-2-one). The collected PANI was dried in a JRAD Model S oven at 60 °C for 18 h, then ground in a mill and sieved through a 250 μm mesh.

Polyacrylic acid salt

The preparation of PAAS was based on the method published by Wang11. Briefly, prop-2-enoic acid (acrylic acid, 0.60 mol) was titrated with 4 M sodium hydroxide solution to achieve neutralization (pH ≈ 7). The neutralized solution was then transferred to a 500 mL volumetric flask and diluted to volume with distilled water. Potassium persulfate (0.001 mol) was added as an initiator, and the mixture was refluxed at 60 °C for 2 h to form sodium polyacrylate (PAAS). The resulting PAAS was irradiated in a KOR-180 A microwave oven at 760 W for 15 min, then ground in a mill and sieved through a 250 μm mesh.

Polyacrylonitrile

The preparation of PAAS was based on the method published by Guyot12. Briefly, acrylonitrile (prop-2-enenitrile, 0.56 mol) was mixed with distilled water in a 500 mL volumetric flask to form a solution. The mixture was heated to 60 °C, and potassium persulfate (0.001 mol) was added as an initiator. Polymerization proceeded under reflux at 60 °C for 2 h to yield polyacrylonitrile (PAN). The product was filtered using a WP6122050 Pyrex Buchner funnel connected to a BOECOR-400 vacuum pump, then washed sequentially with 100 mL each of distilled water, ethanol, and acetone (propan-2-one). Finally, the PAN was ground in a mill, sieved through a 250 μm mesh, and compressed using a hydraulic press into discs with diameters of 1 cm and 2.5 cm.

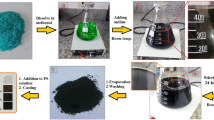

PANI@PAAS and PANI@PAN samples

A constant mass (1.800 g) of the core material (PAAS or PAN) was dispersed in 30 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) or distilled water, respectively—solvents selected to dissolve the shell precursor (PANI) while leaving the core insoluble, thus promoting core-shell formation. Pre-prepared 10 mL aqueous solutions of anilinium chloride (0.600 g for 20% PANI, 0.450 g for 15%, and 0.300 g for 10%) were added to the core dispersions. Then, 10 mL aqueous solutions of ammonium persulfate (1.320 g, 0.990 g, and 0.660 g, respectively) were introduced to initiate shell polymerization at the specified weight ratios. The reaction mixtures were stirred for 3 h, followed by the addition of 10 mL of 2 M hydrochloric acid to quench the process. The resulting core-shell samples were filtered using a WP6122050 Pyrex Buchner funnel connected to a BOECOR-400 vacuum pump, washed three times with 10 mL of isopropanol (propan-2-ol) each, and dried at 60 °C for 20 h. Table 1 lists the codes for the prepared core-shell samples.

PAAS/PANI physical mixture samples

Ground PAAS and PANI powders were physically mixed for 10 min at PANI weight ratios of 0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% (total mass 1.800 g per sample). The resulting mixtures were compressed using a hydraulic press into discs: 1 cm diameter for thermal imaging and 2.5 cm for conductivity and contact angle measurements, as detailed in Table 2. In the sample codes, the first number indicates the PANI weight%, while the second denotes the total sample mass.

Characterization techniques

FT-IR spectroscopy

The infrared transmittance spectra of the samples were recorded after preparing pellets with KBr. The pellets were prepared by grinding sample powder each with KBr (in the ratio of about 1:250 by weight) using a grinding mill, and then pressing them with a load of 9 tons in a mold of diameter 1 cm. The spectrum was recorded with 6 scans and a resolution of 1 cm− 1 in the range [400–4000] cm− 1 using infrared spectrophotometer (Bruker, Vector 22).

Contact angle

The contact angle was measured to support the claim of core encapsulation by PANI. The measurement was done by recording a video of a drop of distilled water being dropped using a 20 µL micropipette, with a recording time of 30 s and a frame rate of 15 fps, where the drop was dropped onto the surface of each sample, which was placed on a holder. The video was recorded using promote® digital camera, then the Angle Meter® software was used to measure the contact angle between the sample surface and the distilled water drop.

SEM imaging

To investigate the morphology of the prepared samples. The sample with the best IR-camouflage performance, PANI@PAAS-0.20, was imaged using a scanning electron microscope Tescan Vega-II XMU5136. In addition, PANI@PAN-0.20 was imaged as well.

Specific electrical conductivity measurements

The samples specific electrical conductivity was measured via the probe method using KEITHELY-220 as a programmable current source and KEITHELY-617 as a programmable electrometer. A linear fit for the relation below was achieved. Where \(\:u\:\left(mV\right)\) is the voltage difference; \(\:I\:\left(\mu\:A\right)\) is the applied current; \(\:e\:\left(mm\right)\) is the thickness of the sample; \(\:\sigma\:\:(S/mm)\) is the specific electrical conductivity.

Thermal imaging

A custom setup (as shown in Fig. 1) was used to capture thermal images of the prepared 1 cm diameter discs. The sample was placed in an aluminum holder fixed on a hot stage, then imaged using a FLIR-type thermal camera (model FP775901G220) positioned 3 m away, under ambient lab conditions of 28 °C (serving as the background temperature). The hot stage was set to 85 °C, with sample surface temperature monitored via thermocouple and recorded by the camera.

Results and discussion

FT-IR spectroscopy

The PANI and PAAS spectra (Fig. 2) are consistent with the reference spectra of the prepared polymers13;14. The presence of out-of-plane bending vibrations of the (C–H) bonds in the benzene rings in the polymer chain within the spectral region [400–1000] cm− 1 indicates the success of the PANI polymerization process13. The disappearance of the peak corresponding to the (C=C) bonds in sodium acrylate monomers indicates the successful preparation of PAA. In the case of the physical mixture (PAAS/PANI), as showed in Fig. 2, the absorption peaks corresponding to the bonds for both of the prepared polymers are observed without any shifts in the absorption peaks, but rather a decrease in the relative intensity of the absorption. This result is consistent with what would be expected in the case of a physical mixture and the absence of any interactions between the two polymers.

The IR spectra of PANI@PAAS and PANI@PAN core-shell composites, along with those of pure PAN and PANI for reference, are shown in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3A, the spectra reveal that increasing PANI content causes the overall profile to progressively resemble pure PANI, with characteristic PAAS absorption peaks (e.g., the broad -OH band at ~ 3400 cm−1) diminishing in intensity. This is evident from the rising intensity ratio of the PANI benzenoid ring band (~ 1500 cm−1) relative to the PAAS -OH peak, signaling thicker PANI shell coverage. At higher loadings, complete encapsulation becomes more likely; however, beyond an optimal threshold, excess PANI precipitates independently, yielding physical mixtures alongside core-shell particles rather than uniform coatings. A comparable trend appears in the PANI@PAN spectra (Fig. 3B). Due to PAN’s water insolubility and lower specific surface area versus PAAS, effective coverage occurs at reduced PANI levels, with composite spectra closely mirroring pure PANI—yet retaining a visible CN stretching peak (~ 2250 cm−1) from PAN, whose relative intensity fades with higher shell thickness, confirming progressive encapsulation. Overall, these observations underscore how polymer solubility and composition dictate coating efficiency and core-shell morphology. Critically, the core-shell IR spectra diverge markedly from those of physical mixtures, validating the structured architecture. For instance, the PANI benzenoid band undergoes a ~ 23 cm−1 red shift in core-shell samples due to robust interfacial interactions between core and shell—absent in mixtures. Physical blends exhibit unaltered peaks from both components, whereas core-shell variants display shifts, suppressed bands (e.g., –OH from PAAS), and enhanced absorption from shell dominance and coupling effects. These distinctive spectral signatures not only affirm successful core-shell synthesis but also highlight interfacial synergies essential for boosting IR camouflage efficacy.

Contact angle

Table 3 shows that the contact angle increases with the increase in the weight% of PANI in the physical mixture samples, and this is consistent with the PANI contact angle being greater than the PAAS angles, because PAAS contains the hydrophilic carboxylate groups. For the core-shell structure samples, the contact angle also increases with the increase in the weight% of PANI, but this increase is smaller than in the physical mixture samples. This may indicate the success of forming the core-shell structure or the interactions between the two polymers in this structure. As for the PANI@PAN samples, the contact angle decreases with the increase in the PANI percentage, because PANI contains more hydrophilic groups than PAN does. It is also noted that the contact angle in these samples is smaller than those of either components, and this may be due to the different interactions between the two polymers. It is worth noting that the surface morphology has an effect on the contact angle, and the shape of the surface of the samples also plays an important role in determining the contact angle. Since the PANI@PAAS surfaces are smoother and less porous those of PANI@PAN, this results in smaller contact angles for the latter.

SEM imaging

The SEM image of the PANI@PAAS-0.20 sample is presented in (Fig. 4). It is observed that PAAS is almost completely encapsulated by PANI within the core-shell structure, which proves the morphology of the prepared structure. The diameter of the core-shell prepared sample is approximately 150 ± 2 nm. On the other hand, the SEM image of PANI@PAN-0.20 reveals a coarser morphology (450 ± 42 nm), likely due to the original shape of the PAN particles and their insolubility in water. This limits particle uniformity, dissolution, and edge softening. In contrast, the finer morphology of PANI@PAAS-0.20 suggests enhanced IR shielding performance.

Conductivity measurements

The conductivity of the samples was measured by the four-probe method, where the values of the potential generated, when a specific current was applied, were recorded. To calculate the specific electrical conductivity, a linear fit of the potential-current relationship was achieved. Table 4 below shows the thickness and the specific electrical conductivity. No conductivity values were recorded for samples PAAS05 and PAAS10PANI, which is consistent with PAAS being an insulating polymer and the proportion of PANI being low in the latter samples.

The measured electrical conductivity values of the conductive samples are within the specific electrical conductivity range of semiconductors [10− 8–103] S/cm, as listed in Table 4. The conductivity values increase with increasing PANI percentage in all prepared samples, which is consistent with PANI being the conducting polymer, while PAAS and PAN are insulators. Also, the increase in the conductivity increase in the PANI@PAAS and PANI@PAN samples with increasing PANI percentage is an indirect indicator of the success of the core-shell structure preparation.

Thermal imaging

Figure 5 presents thermal images of the PANI@PAAS and PANI@PAN core-shell composites, all recorded at an actual sample temperature of 38 °C. The PANI@PAAS samples demonstrate superior thermal camouflage performance across all PANI ratios compared to PANI@PAN, attributable to two key factors: (1) morphological differences—SEM images reveal PANI@PAAS’s finer, more uniform structure versus the coarser PANI@PAN, enhancing internal heat absorption and reducing IR emission for a lower thermal signature; and (2) distinct IR absorption profiles stemming from PAAS’s polar carboxylate groups (broad –OH/–COO− bands) versus PAN’s nitrile (CN) groups, leading to varied environmental interactions and emissivity. In contrast, Fig. 6 displays thermal images of the physical mixture samples, where PANI/PAAS blends exhibit poor camouflage, appearing prominently against the hot stage background due to uneven heat distribution and higher surface emissivity. This inferior performance in mixtures versus core-shell structures reinforces the camouflage mechanism’s reliance on the latter’s controlled morphology and interfacial effects, which promote uniform IR suppression.

Thermal image processing was performed to extract the apparent temperatures recorded by the camera for the prepared core-shell samples, as detailed in Table 5. For PANI@PAAS composites, these apparent temperatures closely approach the background (ambient) level, decreasing further with increasing PANI proportionhighlighting enhanced IR suppression. The PANI@PAAS-20% sample exhibited the best camouflage, with portions blending seamlessly into the aluminum holder background (Fig. 5), likely due to tunable morphology from optimized PANI loading that promotes uniform heat dissipation and reduced emissivity.

Compared to PANI@PAN, the PANI@PAAS superiority across ratios stems from differing IR absorption: PAAS’s C=O stretch at ~ 1734 cm−1 (corresponding to 5.8 μm emission) falls outside the atmospheric windows (8–12 μm and 3–5 μm), minimizing detectability, whereas PAN’s C≡N stretch at ~ 2250 cm−1 (4.4 μm) aligns within them, allowing easier IR transmission. In contrast, PAAS/PANI physical mixtures showed modest camouflage, with apparent temperatures ranging 34–38 °C (at actual 38 °C), as their blended absorption peaks yield emissions predominantly in the atmospheric windows, leading to higher visibility from heterogeneous surface effects.

Table 6 demonstrates that the all-organic core-shell composites developed here, leveraging the proposed thermal camouflage mechanism, outperform literature-reported hybrid materials across comparable temperature ranges; moreover, they excel in lightweight design, cost-effectiveness, and scalability for large-scale production.

The proposed mechanism of the observed thermal camouflage

The electronic transitions processes (Fig. 7) between the vibrational and rotational levels that occur as a result of thermal absorption in the C=O bonds in PAAS and the C≡N bonds in PAN, in addition to the radiative emission processes that occur in both PAN and PAAS. Figure 8 illustrates the proposed camouflage mechanism. The material covered with the prepared composite material PANI@PAAS receives the electromagnetic radiation in the infrared range due to heating or any thermal signal source. Then, PANI acts as a guide for the electromagnetic waves towards the inside (without noticeable reflections) due to its conductive properties. When the signal reaches PAAS, the wavelengths corresponding to the two atmospheric windows are dissipated by nonradiative transitions, while the expected value of the emission wavelength is corresponding to the emission resulting from the transition occurring in the (C=O) bond at the wavenumber 1734 cm− 1 with a wavelength of 5.77 μm, which is absorbed by air gases and is not detectable by thermal cameras.

Conclusion

Two lightweight, all-organic core-shell composites (PANI@PAAS and PANI@PAN) were synthesized via in-situ oxidative polymerization. The PANI@PAAS material exhibits excellent infrared camouflage through a synergistic mechanism combining IR waveguiding (internal scattering and absorption) and radiative cooling (low emissivity in atmospheric windows), achieving near-zero thermal contrast (ΔT = 0 °C) against a 28 °C background at an actual sample temperature of 38 °C. Experimental results demonstrate that PANI@PAAS outperforms PANI@PAN across all compositions in thermal imaging efficacy, owing to PAAS’s favorable IR absorption profile outside key transmission windows (e.g., C=O bands at ~ 1734 cm−1). As shown in Table 6, these composites surpass prior hybrid materials in performance within comparable temperature ranges, while offering superior lightweight design, low cost, and scalability for production. This versatile IR-camouflaging material holds strong potential for civilian uses, including thermal regulation in energy-efficient buildings via low-emissivity coatings that reduces radiative heat loss, heat management systems for electronics, and protective apparel like firefighting suits or industrial gear that reduces thermal detectability and boosts safety in high-heat scenarios.

For further enhancement of the current work authors suggest further studies on scalability, environmental stability and aging, humidity, UV exposure, core-shell morphology through TEM and SEM-EDS, and emissivity measurements.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Peng, L., Liu, D., Cheng, H., Zhou, S. & Zu, M. A multilayer film based selective thermal emitter for infrared stealth technology. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6 (23), 1801006. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201801006 (2018).

Fan, X., Li, S., Zhang, W. & Xu, W. Recent progress in two-dimensional nanomaterials of graphene and MXenes for thermal camouflage. Ceram. Int. 49 (4), 5559–5572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.12.034 (2023).

Wang, L., Xu, G., Liu, C., Hou, H. & Tan, S. Surface-modified CeO2 coating with excellent thermal shock resistance performance and low infrared emissivity at high-temperature. Surf. Coat. Technol. 357, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.10.058 (2019).

Su, Y., Zhao, X. & Han, Y. Phase change microcapsule composite material with intelligent thermoregulation function for infrared camouflage. Polymers 15 (14), 3055. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15143055 (2023).

Kang, Q., Li, D., Guo, K., Gao, J. & Guo, Z. Tunable thermal camouflage based on GST plasmonic metamaterial. Nanomaterials 11 (2), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020260 (2021).

Ahmad, F., Ulker, Z. & Erkey, C. A novel composite of alginate aerogel with PET nonwoven with enhanced thermal resistance. J. Non-cryst. Solids. 491, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.03.023 (2018).

Wu, X. et al. Passive smart thermal control coatings incorporating CaF2/VO2 core–shell microsphere structures. Nano Lett. 21 (9), 3908–3914. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00454 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Flexible mid-infrared radiation modulator with multilayer graphene thin film by ionic liquid gating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11 (14), 13538–13544. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b21900 (2019).

Bu, X. & Bai, H. Recent progress of bio-inspired camouflage materials: from visible to infrared range. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 39 (1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40242-022-2170-2 (2023).

Stejskal, J. & Gilbert, R. G. Polyaniline. Preparation of a conducting polymer (IUPAC technical report). Pure Appl. Chem. 74(5), 857–867. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1351/pac200274050857

Wang, T. Method for Preparing Polyacrylic Acid or Sodium Polyacrylate (China CN101423577A) (China National Intellectual Property Administration, 2008).

Guyot, A. 16-Precipitation Polymerization. Comprehensive Polymer Science and Supplements, vol. 4, 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-096701-1.00131-2 (Pergamon, 1986).

Butoi, B., Groza, A., Dinca, P., Balan, A. & Barna, V. Morphological and structural analysis of Polyaniline and Poly (o-anisidine) layers generated in a DC glow discharge plasma by using an oblique angle electrode deposition configuration. Polymers 9 (12), 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9120732 (2017).

Grabowska, B. & Holtzer, M. Structural examination of the cross-linking reaction mechanism of polyacrylate binding agents. Arch. Metall. Mater. 54 (2), 427–437 (2009).

Xu, R., Wang, W. & Yu, D. A novel multilayer sandwich fabric-based composite material for infrared stealth and super thermal insulation protection. Compos. Struct. 212, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.01.032 (2019).

Yuan, Z., Liu, Y., Chen, Z., Wang, F., Jung, C., Rho, J. & Liu, Y. Infrared camouflage utilizing phase-change materials with high scattering and tunable emissivity. Photonics Res. 13(9) 2539. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.562366. (2025).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A.E.: Experimental work, writing-original draft, validation, investigation, formal analysis. R.A.B.A.: Writing-review and editing, validation, investigation, formal analysis, supervision, conceptualization. Y.A.: Writing-review and editing, supervision, conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ezzo, H.A., Almarjeh, R.A.B. & Atassi, Y. Novel core-shell composite material based on polyacrylic acid salt and polyaniline for infrared camouflage applications. Sci Rep 16, 1353 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30985-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30985-4