Abstract

This study explores the influence of propylene carbonate (PC) on the properties of casting polyurethane elastomers. Five formulations were developed with varying PC content: 0% (PU0), 1% (PU1), 5% (PU5), 10% (PU10), and 20% (PU20) by weight in the prepolymer, while maintaining a consistent curing ratio. The effect of PC incorporation on hardness, resilience, segmental interaction, stress-strain behavior, thermal stability, and abrasion resistance was systematically evaluated to understand the impact of PC on the phase structure and performance of the elastomers. The successful synthesizing of polyurethanes was confirmed by spectroscopy analysis. The hardness values showed a progressive decline with increasing PC content, indicating a reduction in cross-link density and increased polymer chain mobility. The resilience of samples increases progressively from PU0 (28%) to PU20 (47%), indicating that PC enhances the elastomer’s ability to recover energy upon deformation. At higher PC levels, the system transitions toward rubber-like elasticity. By modifying the cross-link density and enhancing chain mobility, PC improves the elongation of the polymer while reducing tensile strength. In Addition, abrasion loss decreased with increasing PC concentration. This study provides insights into optimizing the composition of polyurethane elastomers for diverse applications where tailored physical and mechanical properties are required. Adding PC offers a simple and cost-effective method for tailoring the properties of ester-based polyurethane elastomers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Segmented polymers, such as polyurethanes, and polyurea (PU), represent a significant and practical subgroup of soft materials. These polymers are synthesized by linking two or more distinct polymer chains that are thermodynamically and physically incompatible. This incompatibility leads to micro-phase separation, resulting in self-assembly that holds great potential for various applications across numerous industries1,2,3,4,5.

The soft segment, characterized by a low glass transition temperature, forms a continuous substrate that exhibits flexibility at low temperatures. In contrast, the hard segment, which has a higher glass transition temperature and melting point, tends to self-assemble into domains through physical networks. These domains act as fillers within the continuous matrix, enhancing the properties of the soft segment, including mechanical strength, heat resistance, and solvent resistance6,7,8,9.

Polyurethane elastomer is one of the most important engineering polymers due to their unique characteristics. Their high mechanical strength, excellent wear and tear resistance, and appropriate elasticity and flexibility make them highly engineered materials10,11. Polyurethane elastomers are utilized as high-tech materials in various industries, including oil and gas, mining, automotive, transportation, military, and marine sectors. By combining the properties of plastics, rubbers, and metals, polyurethane elastomers have become the most engineered polymers available. A wide range of engineering parts can be produced using polyurethane casting resins in conjunction with chain extenders, particularly for applications requiring high resistance to wear, tear, pressure, impact, and chemicals. The low production cost, lack of need for expensive equipment, high adhesion to metals, and the ability to mold complex shapes make polyurethane casting an ideal method for manufacturing intricate engineering components12,13,14,15,16,17.

The three main components of polyurethane elastomers are polyols, isocyanates, and chain extenders. The predominant types of polyols in this context are polyesters and polyethers, which are crucial to the polyurethane industry due to their architectural diversity and varying molecular weights. Polyester polyols are preferred for applications where wear resistance, load-bearing capacity, heat aging resistance, chemical resistance, and UV stability are essential. Conversely, polyether polyols offer better low-temperature flexibility, hydrolytic resistance, and microbial resistance compared to polyester polyols. Additionally, casting resins based on polyester polyols tend to have higher viscosity, which can complicate the casting process compared to those based on polyether polyols18,19,20.

Numerous factors influence the final properties and micro-phase separation of polyurethane elastomers. By carefully designing the molecular structure and considering these factors, the properties of the final polymer can be tailored to specific applications. The versatility in selecting soft and hard segments allows the engineering of polyurethane elastomers to meet diverse requirements21,22,23,24.

Various additives have also been employed to modify properties of polyurethanes such as gel time, hardness, pot life, post-cure time, viscosity, wear resistance, processability, and modulus. Utilizing additives is a practical, straightforward, and cost-effective approach to tailoring the final properties of polyurethanes25,26,27,28,29.

Sivakumar et al.26 have examined the effects of plasticizers on elastomeric coatings, demonstrating that additives can enhance wear resistance and reduce ice adhesion. Their work has underscored the importance of tailoring polyurethane formulations to improve durability and application-specific performance. Czeiszperger et al.30 have evaluated the effectiveness of various additives in improving abrasion resistance in polyurethane elastomers. Their study has identified specific additives that reinforce the polyurethane matrix, extending the lifespan of materials in high-abrasion environments. Jeczalik27 has discussed the impact of hydrocarbon and ester plasticizers on urethane elastomers used for sealing applications. The findings reveal how different plasticizers affect flexibility, hardness, and sealing efficiency, aiding in the design of optimized formulations. Tereshatov et al.28 introduced novel diurethane plasticizers for thermoplastic polyurethanes, demonstrating improvements in flexibility, toughness, and processing capabilities. Their work has highlighted the potential of advanced plasticizers in enhancing polyurethane composite. Tereshatov et al.29 have explored the plasticization of poly(urethaneureas) and its effects on mechanical and thermal properties. Plasticizers are shown to improve elongation at break and reduce material rigidity, offering insights into molecular-level interactions in polyurethane systems.

The propylene carbonate (PC) as an additive has been widely used in the industry to improve processability and increase pot life31,32,33. Despite the interest in propylene carbonate, there has been limited in-depth research on its effects when added to polyurethane elastomers. Consequently, the aim of the research is to investigate the impact of propylene carbonate on the properties of casting polyurethane elastomers. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the modification of casting polyurethane elastomers (CPUs) using propylene carbonate. In this context, the current study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of propylene carbonate on the performance of polyester-based polyurethanes. The findings will help in optimizing the formulation of polyurethane elastomers for specific applications. Still, they will also contribute to the broader understanding of how plasticizers influence the structure-property relationships in polyurethanes. Ultimately, this research could lead to the development of enhanced polyurethane materials with improved flexibility, abrasion resistance, and durability, offering significant benefits across a range of industries.

Materials

Polybutylene adipate (Mn = 2000 g mol−1), 2,4-toluene diisocyanate (TDI), Di-Butyl-Tin-Di-Laurate (DBTL), 4,4′-Methylenebis(2-chloroaniline) (MOCA) and propylene carbonate (PC) were all used without further purification.

Casting resin preparation

To ensure uniform heat transfer to the reactor, it is placed in an oil bath. Before synthesis, polyol was dried in a vacuum oven at 85˚C for 5 h to ensure residual moisture removal. Based on both supplier specifications and our own practice, drying at 85 °C for 5 h is sufficient to reduce the moisture content that would interfere with isocyanate curing. To further ensure dryness, the polyol was maintained at 85 °C until a constant weight was achieved and no bubble formation was observed during vacuum degassing, indicating the absence of free moisture. These conditions have been widely reported in literature as sufficient for polyester polyols4,16,34.

Initially, polyol was added to the reactor along with DBTL. Subsequently, TDI was introduced dropwise into the system, and the reaction proceeded for 3 h at a temperature of 60–70 ˚C under mechanical stirring and nitrogen flow. During the reaction, the percentages of NCO groups were determined by titration according to ISO 14896:2010. The NCO % was 5.4 ± 0.2.

Polyurethane elastomer preparation

The resin was preheated at 70 ~ 75℃ for 4 ~ 6 h until it was completely melted. Then, it was putted in clean and dry container, heated at temperature 80 ~ 85℃, and degassed under the vacuum until no bubbles can be seen from the surface of the materials. Different weight percentages of propylene carbonate were added to the resin and mixed. Then, the melted MOCA (the temperature is approximately 120 °C) was added, and the mixture was stirred heavily. The mixed material was poured into the preheated mold coated with the release agent. The elastomers were placed in oven at 120 ℃ to post cured for 12 h. Samples description information is presented in Table 1. From the Table 1, it is seen that the samples of PU10 and PU20 show different hardness and resilience, yet the abrasion loss results are reported as the same across multiple averaged tests. The same numerical averages may appear unusual when hardness and resilience differ, but this outcome follows directly from the interplay of two opposing wear mechanisms introduced by propylene carbonate. Why PU10 and PU20 converge to the same abrasion loss? At 20% PC, additional softening further improves resilience, but the structure also loses additional hard-segment reinforcement. These two competing effects counterbalance each other, leading to: A plateau in abrasion resistance between PU10 and PU20, despite their measurable differences in hardness and resilience.

Characterization

At first, the polyurethanes are synthesized, and their chemical analyses are performed by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy with 45-degree ZnSe crystal (Nexus 670 spectrometer, Thermo Nicolet, USA) in a range of 600–4000 cm−1. Then, we apply an electromechanical tensile tester (Instron 5566, Elancourt, France), and find mechanical properties of samples. Dumbly specimens are inserted between two holders at a distance of 35 mm. The curves of stress-strain of the substances are plotted from the load-deformation curves recorded at a stretching speed of 350 mmmin−1. The hardness test was conducted using a Shore A durometer, according to ASTM D2240-75.

Abrasion resistance is measured with a rotating cylindrical drum. Under a load of 10 N, the samples are rubbed with the roller abrasion cloth. The abrasion distance is 40 m. The sample weight is measured before and after the test. The weight loss is the abrasion loss and is used to measure the abrasion resistance. The smaller the loss results the better the abrasion resistance of the material. Each data point is obtained from the average value of five measurements.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using a Mettler Toledo TGA/SDTA851 under N2 atmosphere at a flow rate of 50 mLmin−1. The thermograms are obtained from 0 to 700 ˚C at a heating rate of 10 ˚C min−1. A sample weight of about 10 mg is used for all the measurements.

Results and discussion

ATR-FTIR

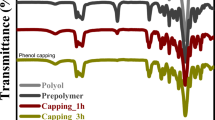

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is used to verify chemical structures of the synthesized polyurethanes. The ATR-FTIR spectra of the samples are presented in Fig. 1.

The ATR-FTIR spectra of these samples are almost similar and they show the peaks at 3450–3200 cm−1 (N–H stretching), 2923 cm−1 (asymmetric C–H stretching), 2850 cm−1 (symmetric C–H stretching), 1750–1650 cm−1 (C = O stretching) and 1104 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching). The last absorbance at 2270 cm − 1 ascribed to N = C = O stretching was not seen in the samples. The obtained results confirm the successful polymerization of all CPUs.

Hardness

Hardness is a key parameter in the characterization of polyurethanes and one of the primary properties defining their commercial applications. The Shore A hardness test results for the samples are presented in Table 1. The data indicate a progressive reduction in hardness by increasing PC content. The highest hardness value (91.75 Shore A) was recorded for PU0, reflecting a highly cross-linked structure with no plasticizing effects. A slight reduction to 91.33 Shore A in PU1 suggests that at low PC concentrations, the cross-linked network remains largely intact, with minimal influence on the microstructure. In PU5, a noticeable drop to 89.33 Shore A indicates that PC’s plasticizing effect becomes more pronounced, slightly reducing the cross-link density. The most significant reduction, 84.33 Shore A, occurred in PU20, indicating substantial disruption of the hard segment domains. This softening effect results from reduced cross-link density due to the higher PC content. PC acts as a plasticizer by reducing intermolecular interactions and increasing polymer chain mobility. At higher concentrations, it disrupts the hard segment domains, leading to lower hardness values. As a reactive diluent, PC may interact with the prepolymer but form fewer hard cross-links than MOCA, contributing to a lower cross-link density and a softer material.

Resilience

Resilience is a crucial property in polyurethane applications and is independent of hardness. It significantly influences the selection of ester- and ether-based polyurethanes. Typically, ester-based polyurethanes exhibit lower resilience and reversibility than their ether-based counterparts. As a result, their application is limited in industries requiring highly resilient materials35,36,37.

The resilience diagram of the samples is displayed in Fig. 2. The resilience of samples increases progressively from PU0 (28%) to PU20 (47%), indicating that PC enhances the elastomer’s ability to recover energy upon deformation. This trend suggests that PC significantly influences the microstructure of the polyurethane matrix, particularly the interaction between hard and soft segments. Resilience in polyurethanes arises from the balance between solid-like and rubber-like elasticity. Solid-like elasticity is attributed to the hard segments, which provide structural integrity, while rubber-like elasticity originates from the soft segments, responsible for flexibility. At low PC levels, resilience remains relatively low due to the dominance of strong intermolecular interactions in the hard segments. The hard domains restrict the mobility of the soft segments, resulting in a more rigid, solid-like behavior. This is consistent with polyurethanes where the hard domains act as physical crosslinks, impeding energy recovery. The dominance of solid-like elasticity due to rigid hard segments results in poor energy recovery (28%). As PC is introduced at 5% and 10%, resilience increases to 33% (PU5) and 36.33% (PU10). This improvement reflects partial plasticization of the hard domains, allowing the soft segments to move more freely during deformation, leading to improved elastic recovery. The resilience reaches its peak at 47% for PU20. At this concentration, PC effectively disrupts hard-segment aggregation, creating a softer, more rubber-like matrix. The improved segmental mobility of the soft domains and reduced hard-segment stiffness enable superior energy recovery. At higher PC levels, the system transitions toward rubber-like elasticity, achieving optimal balance. The disruption of rigid hard-segment domains and enhanced soft-segment flexibility explain the significant resilience improvement (47%). With PC, the softer network enables elastic recovery, storing and releasing energy more efficiently. By loosening the chain packing and enabling segmental mobility, PC allows the polymer matrix to better respond to applied stress, reducing irreversible damage and increasing resilience. The improved integration between hard and soft phases due to PC ensures smoother stress distribution, reducing stress concentration zones and enhancing recovery behavior. The soft segments impart rubber-like elasticity, while the hard segments contribute to the solid elasticity. The balance between these segments defines the overall mechanical behavior of the material. Modifications like the addition of PC significantly impact the elastic properties of polyurethanes. In applications where resilience is critical, incorporating PC offers an industrially viable, cost-effective, and straightforward method to enhance the resilience of ester-based polyurethanes.

TGA

The thermogravimetric analysis curves illustrate the thermal decomposition of the polyurethane elastomer samples with varying amounts of propylene carbonate added (Fig. 3). All samples exhibit thermal degradation in two primary stages. In thermally analyzing polyurethanes, the first stage of degradation is typically associated with the hard segments, while the second stage corresponds to the soft segments38,39,40.

The initial weight loss, observed between 250 and 350 °C, corresponds to the degradation of the hard segments. This includes the breakdown of urethane linkages and the aromatic components in the hard domains. Additionally, ester linkages in the soft polyester segments may start to break in this temperature range, contributing to the initial weight loss. However, the contribution from soft segments is generally smaller in this stage compared to urethane bonds. The second major weight loss, occurring between 350 and 500 °C, is attributed to the degradation of the soft segments derived from the polyester polyol. These segments degrade at higher temperatures due to their relatively more stable aliphatic ester bonds. The higher PC content, especially in PU20, enhances the thermal resistance of the soft segments. The weight retention at higher temperatures improves with increasing PC content, suggesting enhanced char formation. The higher residual weight at 600 °C for PC-containing samples suggests that PC promotes char formation, possibly due to its decomposition products.

In the TGA analysis, while the PC content increases, the thermal resistance and char yield improve. However, the residual mass for PU20 is less than that for PU5 in the figure, indicating a lack of a clear trend in the TGA data. The TGA curves indicate that moderate PC additions (PU5) produce higher residue than some higher PC loadings (PU20). This behavior reflects competing effects of PC on the decomposition chemistry and microphase morphology. At low-moderate PC content, PC alters the local chemistry and microphase arrangement in a way that favors formation of condensed-phase, carbonaceous fragments (increasing char). At higher PC content, dilution of char-forming hard segments and increased formation of low-molecular-weight volatile degradation products dominate, resulting in greater mass loss and lower final residue.

Two competing effects of PC explain the observed behavior: (i) PC-induced stabilization / promotion of condensed-phase char at low-to-moderate loadings. Moderate amounts of PC can change local packing and interfacial chemistry between soft and hard domains. This can favor secondary condensation or recombination reactions during pyrolysis (e.g., formation of crosslinked carbonaceous fragments) that remain as non-volatile char. In some polymer/additive systems, small polar additives assist in forming a viscous, partially crosslinked surface during degradation that limits volatiles escaping and thereby increases residue. (ii) Dilution and volatilization effects at high PC loading. At high PC content the concentration of aromatic/higher-mass char-forming moieties (originating from TDI and hard segments) is effectively diluted by PC. PC itself primarily decomposes to low-molecular-weight, volatile fragments (carbonates → CO, CO₂, small organics) and does not contribute significant char. Greater plasticization and reduced hard-domain continuity increase the fraction of degradation that proceeds through volatilizing pathways (fragmentation and release), lowering final residue. The observed maximum in char at moderate PC, followed by a drop at high PC (PU20), is therefore a natural outcome of these opposing tendencies.

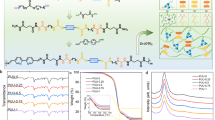

Stress-strain

Figure 4 shows the stress-strain performance of the CPUs. In overall look, an increase in PC concentration results in a sharp reduction of tensile strength and a considerable enhancement of elongation at break. PU0 and PU1 exhibit the highest stress at break (~ 39 MPa), with PU1 slightly outperforming PU0.

This aligns with the hypothesis that a small amount of PC (1%) marginally enhances the tensile strength, likely due to minor changes in phase distribution or stress-relieving effects. This may explain the slight increase in stress at break (39.4 MPa), possibly due to better stress distribution and reduced localized defects. As PC content increases beyond 1%, stress at break significantly decreases, reaching its lowest value at PU10 (23.4 MPa). This trend suggests that higher PC concentrations disrupt the crosslinked network structure, weakening the overall matrix. The soft segments become less rigid due to the incorporation of PC, which weakens the overall cohesive forces within the polymer matrix. However, PU20 (27.2 MPa) shows a slight recovery in stress at break compared to PU10, possibly indicating some redistribution effects at higher PC levels. At higher PC content (20%), the soft segments may gain increased mobility, which allows for some reorganization of the segment domains under tensile stress. During tensile loading, PU20 may exhibit better strain-induced alignment of soft and residual hard domains than PU10. This improved alignment might enhance the material’s ability to bear stress, even if its hardness is reduced. Elongation at break consistently increases with PC content, highlighting a direct correlation between PC-induced plasticization. There is a consistent increase in elongation at break with increasing PC content, from 1051% (PU0) to 1312% (PU20). The plasticizing effect of PC likely contributes to this, as it increases chain mobility within the polyurethane matrix. The highest elongation values are observed for PU10 and PU20, suggesting that these formulations achieve the most significant flexibility due to higher levels of PC. This increases the flexibility and mobility of the soft segments, allowing for greater chain extension under tensile stress, leading to a higher elongation at break (1312%). For applications requiring high tensile strength, neat polyurethane (PU0) or PU1 is preferable. For applications demanding high flexibility and elongation, PU10 or PU20 would be more suitable. The choice of formulation should consider the balance between strength and ductility required for the specific application. From the figure, it is seen that as the PC content increases, the stress shows a slight increase, followed by a decrease, and then an increase again. The observed non-monotonic behavior arises from the competition between chain mobility and hard-segment integrity, both strongly influenced by PC content. At low PC (1%) - stress increases slightly, a small amount of PC fills microvoids and reduces localized stress concentrations. Slight relaxation of internal stresses improves load transfer. Hard domains remain intact. Minor strengthening effect (PU1 > PU0). At moderate PC (5–10%) stress decreases sharply PC significantly reduces the cohesion of hard segments. Cross-link density and phase separation decrease. Soft-segment mobility increases, lowering tensile strength, minimum stress at PU10. At high PC (20%) stress increases again. Although hardness decreases, two molecular effects compensate, strain-induced alignment of soft segments Higher chain mobility allows better orientation under load, improving stress transfer. Residual hard domains act as flexible physical crosslinks. Although fewer and less aggregated, they can still provide reinforcement once the chains orient. Thus, PU20 shows a partial stress recovery, although still lower than PU0/PU1. This type of non-monotonic mechanical response is common where the competition between network softening and deformation-induced ordering governs tensile behavior.

Abrasion resistance

Wear in polyurethane elastomers, particularly under abrasive conditions, occurs due to the interaction between the material’s surface and the abrasive surface. The wear mechanisms can be complex and influenced by multiple factors such as the material’s hardness, cross-link density, flexibility, and molecular interactions. Polyurethanes, due to their segmented structure, typically exhibit wear through a combination of micro-tearing in the hard segments and plastic deformation in the soft segments41,42,43,44.

PU0 and PU1 show the highest abrasion loss (45.12 mm2), indicating that these formulations wear more under abrasion. In these samples, wear is predominantly due to micro-cracking or brittle failure of hard-segment domains. The rigid network resists deformation, causing the material to chip or crack under abrasive forces. In PU5, the abrasion loss decreases to 42.66 mm2, and this trend continues with PU10 and PU20, which both show the lowest wear (37.33 mm2). This could be due to increased chain mobility, as the PC softens the polymer, reducing the likelihood of micro-cracks and allowing the material to better resist wear under stress. PU10 and PU20 likely have lower cross-link density due to the higher amounts of PC, which would normally make them more susceptible to wear. However, the increased flexibility and better energy absorption properties of these formulations might allow them to withstand abrasive forces more effectively by distributing the impact more evenly across the surface. As PC concentration increases, the material exhibits greater resilience and energy absorption, reducing wear from micro-cracking. The wear type transitions to more elastic deformation and recovery, minimizing permanent damage. The high resilience in PU20 further supports this mechanism. As the polymer becomes more resilient, it returns to its original shape more effectively after deformation, reducing the impact of cyclic loads and preventing permanent damage to the surface. PC disrupts the aggregation of hard segments, typically responsible for brittleness. By reducing hard-domain stiffness, the material becomes more elastic and less prone to brittle failure during abrasion. Softened materials can deform under stress without losing the material, while more rigid materials (like PU0 and PU1) are more likely to crack or break under abrasive conditions, leading to higher wear. The soft-segment mobility is enhanced with increasing PC, allowing the material to deform elastically under abrasive forces rather than cracking. This elastic recovery minimizes the material removed per abrasion cycle. The lower cross-link density associated with higher PC content likely leads to softer, more flexible chains. These flexible chains can slip and slide over the opposing surface more easily, leading to less localized damage. This reduces the amount of material transfer to the counter surface. However, with lower cross-link density, the material becomes more susceptible to plastic deformation in some cases. If the elastomer becomes too soft, it might be more prone to irreversible deformation. Still, at the PC levels used in formulations (5–20%), the increase in flexibility appears to improve wear resistance by making the material more ductile and capable of absorbing energy rather than losing material. Moreover, PC addition likely alters the surface morphology of the PU elastomer, reducing surface roughness. A smoother surface can lower friction against the abrasive medium, reducing wear.

Conclusion

In summary, the incorporation of propylene carbonate into TDI/polyester-based polyurethane elastomers can significantly influence the mechanical, thermal, and wear properties of the material. By modifying the cross-link density and enhancing chain mobility, PC improves the resilience and elongation of the polymer while reducing hardness and tensile strength. The effects on abrasion resistance are complex and depend on the balance between softening and molecular interactions in the polymer matrix. The thermal stability of the polyurethane elastomers also varies with increasing PC content. Overall, adding PC provides a practical approach to tailoring the mechanical and thermal properties of ester-based polyurethane elastomers. Low PC concentrations maintain mechanical integrity while enhancing resilience, making the modified elastomers suitable for applications requiring flexibility and dynamic performance. However, higher PC concentrations may limit their use in demanding environments requiring high hardness, thermal stability, and abrasion resistance. These findings offer valuable insights into the design and optimization of polyurethane materials for specific industrial applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Bates, F. S. & Fredrickson, G. H. Block copolymers-designer soft materials. Phys. Today 52 32. (1999).

Banan, A. R. Solvent free UV curable waterborne polyurethane acrylate coatings with enhanced hydrophobicity induced by a semi interpenetrating polymer network. Sci. Rep. 15, 21844 (2025).

Mirhosseini, M. M., Haddadi-Asl, V. & Khordad, R. Molecular dynamics simulation, synthesis and characterization of polyurethane block polymers containing PTHF/PCL mixture as a soft segment. Polym. Bull. 79, 643 (2022).

Delebecq, E., Pascault, J. P., Boutevin, B. & Ganachaud, F. On the versatility of Urethane/Urea bonds: Reversibility, blocked Isocyanate, and Non-isocyanate polyurethane. Chem. Rev. 113, 80 (2013).

Whitesides, G. M. & Grzybowski, B. Self-Assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418 (2002).

Kotanen, S. et al. The role of hard and soft segments in the thermal and mechanical properties of non-isocyanate polyurethanes produced via polycondensation reaction. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 132, 103726 (2024).

Yilgör, I., Yilgör, E. & Wilkes, G. L. Critical parameters in designing segmented polyurethanes and their effect on morphology and properties: A comprehensive review. Polymer 58, A1 (2015).

Oliaie, H. et al. Role of sequence of feeding on the properties of polyurethane nanocomposite containing Halloysite nanotubes. Desig Monom Polym. 22, 199 (2019).

Shi, J. et al. Filler effects inspired high performance polyurethane elastomer design: segment arrangement control. Mater. Horizons. 11, 4747 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Blast protection and dynamic response of airbags and foam/airbag composite structures: mechanisms and structural parameter effects. Thin-Walled Struct. 218, 114089 (2026).

Zhang, C. et al. Mechanical responses and microscopic irreversible deformation evolution of thermoplastic fiber-reinforced composites under Cyclic loading. Int. J. Fatigue. 203, 109327 (2026).

Yılgör, E. & Yılgör, I. Polyurethanes: Preparation, Properties, and applications advanced applications. Am. Chem. Soc. 2, 133 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Self-healing polyurethane elastomers: an essential review and prospects for future research. Eur. Polym. J. 214, 113159 (2024).

Clemitson, I. R. Castable Polyurethane Elastomers (CRC, 2008).

Prisacariu, C. Polyurethane Elastomers: from Morphology To Mechanical Aspects (Springer Vienna, 2011).

Mirhosseini, M. M., Haddadi-Asl, V. & Jouibari, I. S. A simple and versatile method to tailor physicochemical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers by using novel mixed soft segments. Mater. Res. Express. 6, 065314 (2019).

Wang, S., Yuan, Y., Tan, P., Zhu, H. & Luo, K. Experimental study on mechanical properties of casting high-capacity polyurethane elastomeric bearings. Const. Build. Mater. 265, 120725 (2020).

Wu, T. & Chen, B. Facile fabrication of porous conductive thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposite films via solution casting. Sci. Rep. 7, 17470 (2017).

Mirhosseini, M. M., Haddadi-Asl, V. & Jouibari, I. S. How the soft segment arrangement influences the microphase separation kinetics and mechanical properties of polyurethane block polymers. Mater. Res. Express. 6, 085311 (2019).

Azarmgin, S. et al. Polyurethanes and their biomedical applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 6828 (2024).

Jin, X. et al. Influence on polyurethane synthesis parameters upon the performance of base asphalt. Front. Mater. 8, 656261 (2021).

Sonnenschein, M. F. Polyurethanes: Science, Technology, Markets, and Trends (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Pukánszky, B. Jr. et al. Nanophase separation in segmented polyurethane elastomers: effect of specific interactions on structure and properties. Eur. Polym. J. 44, 2431 (2008).

Niu, Z. et al. Investigating the effect of chain extender on the phase separation and mechanical properties of Polybutadiene-Based polyurethane. Macromolecular 45, 2400259 (2024).

Somarathna, H. M. C. C., Raman, S. N., Mohotti, D., Mutalib, A. A. & Badri, K. H. Rate dependent tensile behavior of polyurethane under varying strain rates. Construct Build. Mater. 254, 119203 (2020).

Sivakumar, G., Jackson, J., Ceylan, H. & Sundararajan, S. Effect of plasticizer on the wear behavior and ice adhesion of elastomeric coatings. Wear 426, 212 (2019).

Jeczalik, J. Action of hydrocarbon and ester plasticizer in urethane elastomer for sealing purposes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 81, 523 (2001).

Tereshatov, V. V. & Senichev, V. Y. New diurethane plasticizers for polyurethane thermoplastics and perspective functional composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132, 41481 (2015).

Tereshatov, V., Makarova, M. & Borisova, I. The effect of plasticization on the properties of Poly (urethaneureas) based on oligoether diols, 2, 4-toluenediisocyanate, and aromatic diamines. J. Elastomers Plast. 51, 337 (2019).

Czeiszperger, R., Duckett, E., Duckett, J., Seneker, S. & Pastula, A. Effective Additives for Improving Abrasion Resistance in Polyurethane Elastomers (2019).

Cork, S. M. Isocyanate-reactive component for Preparing a polyurethane-polyurea polymer. U.S. Patent No (2010). 7655309. 2 Feb.

Clements, H. J. Reactive applications of Cyclic alkylene carbonates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 42, 663 (2003).

Fayaz, T. K. S., Chanduluru, H. K., Obaydo, R. H. & Sanphui, P. Propylene carbonate as an ecofriendly solvent: stability studies of ripretinib in RPHPLC and sustainable evaluation using advanced tools. Sustainable Chem. Pharm. 37, 101355 (2024).

Weichmann, J. B. Process for removing water from polyurethane ingredients. U.S. Patent No. 5229454 (1993).

Sharmin, E. & Fahmina, Z. Polyurethane: an introduction. Polyurethane 1, 3 (2012).

Wang, W., Li, M., Zhou, P. & Wang, D. Design and synthesis of mechanochromic Poly (ether-ester-urethane) elastomer with high toughness and resilience mediated by crystalline domains. Polym. Chem. 13, 2155 (2022).

Jin, X., Guo, N., You, Z. & Tan, Y. Design and performance of polyurethane elastomers composed with different soft segments. Mater 13, 4991 (2020).

Chattopadhyay, D. K. & Webster, D. C. Thermal stability and flame retardancy of polyurethanes. Prog Polym. Sci. 34, 1068 (2009).

Bian, X., He, J., He, M., Liu, B. & Zhang, Y. Study on the properties of polyurethane–urea elastomers prepared by Tdi/Mdi mixture. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 9248135 (2024).

Chang, W. L. Decomposition behavior of polyurethanes via mathematical simulation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 53, 1759 (1994).

Kwiatkowski, K. & Małgorzata, N. The abrasive wear resistance of the segmented linear polyurethane elastomers based on a variety of polyols as soft segments. Polym 9, 705 (2017).

Beck, R. A. & Truss, R. W. Effect of chemical structure on the wear behaviour of polyurethane-urea elastomers. Wear 218, 145 (1998).

Mizera, K. & Ryszkowska, J. Polyurethane elastomers from polyols based on soybean oil with a different molar ratio. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 132, 21 (2016).

Senichev, V. Y., Pogoreltsev, E. V. & Strelnikov, V. N. The effect of moisture on abrasive wear of urethane-containing elastomers. Wear 548, 205387 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Reza Khordad and Mirhosseini conceived of the presented idea. Khordad and Mirhosseini developed the theory and performed the experiments. Khordad and Mirhosseini wrote the manuscript text. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. The descriptions are accurate and agreed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirhosseini, M.M., Khordad, R. How the reactive additives influence the physico-chemical properties of casting polyurethane elastomers. Sci Rep 16, 2482 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32349-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32349-4