Abstract

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from 12,541 employees aged 19–65 across 26 companies and public institutions who underwent workplace mental health screening. Workplace bullying was self-reported and categorized into ‘Not bullied,’ ‘Occasional bullied,’ and ‘Frequently bullied.’ Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, and suicidality was measured via a self-reported questionnaire from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Overall, 18.7% of women and 10.6% of men reported experiencing workplace bullying. Multivariable logistic regression revealed that both the occasionally and frequently bullied were significantly associated with increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.27–1.69; OR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.36–2.40) and suicide attempts (OR = 2.27, 95% CI = 1.34–3.85; OR = 4.43, 95% CI = 2.13–9.21). The association between bullying and suicidal ideation was significant for participants with and without depression (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.28–1.69; OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.31–2.62). Men exhibited a stronger association (p for interaction < 0.001). Whether an individual later had depressive symptoms or not, higher exposure to workplace bullying was associated with higher suicidality risk. The study highlights the need for companies to screen for bullying and provide mental health resources to prevent workplace-related suicides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2022 World Health Organization guidelines emphasize workplace bullying as a significant issue of workplace harassment, affecting mental health, and potentially leading to severe outcomes such as suicide1. Workplace bullying or mobbing involves sustained (at least 6 months) and repetitive (at least once a week) negative behaviors, mistreatment, or abuse directed at individuals or groups within an organization. A systemic analysis covering 220,000 employees globally estimated workplace bullying prevalence as ranging from 10 to 20% in European nations, 7–13% in the Americas, 7.0% in Australia, and 0.3–10.4% in Asia2. In South Korea, a survey by workplace abuse 119, a non-governmental organization (NGO), found that 34.1% of employees reported experiencing workplace bullying in the previous year. This widespread occurrence demands serious attention for both employee health and organizational productivity worldwide.

In recent decades, with a growing global interest in workplace bullying, multiple studies have established its association with poor mental and physiological health including depression, anxiety, and insomnia as significant risk factors3,4,5,6,7,8. Between workplace bullying and suicidality, studies in Scandinavia9,10,11, Europe12, the America13 and Australia14 have noted significant positive associations. However, research in competitive East Asian work cultures remains limited15. Moreover, a substantial proportion of suicides occur in the general population without depression16,17. Despite this fact, there is a scarcity of research evaluating the direct suicidality linked to workplace bullying.

South Korea is remarkable for its rapid economic development, having transitioned from an underdeveloped nation to a developed, high-income country within a few generations. This economic growth has been described as the Miracle on the Han River18. Amidst this rapid growth, corporations have thrived, serving as knights in shining armor in nurturing emerging industries and markets, expediting exports, and coming to the rescue in the economic landscape19. The placement of South Korea’s working hours as being among the highest in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is not a matter of surprise20. Despite this economic growth, suicide remains a severe societal issue in South Korea; here, suicide rates are the highest among the 42 OECD countries, with 24.1 suicides per 100,000 people in 202021. Notably, suicide stands as the top cause of death among Koreans aged 10–30 and the second highest among those aged 40–60, making it the primary cause of death in the economically active population22. Given the unique characteristics of Korea’s corporate-centered growth aligned with prevalent long working hours, the soaring suicide rates among the working population represent a noteworthy public health concern. A nurse’s suicide at a university hospital due to ‘taeum’, a type of nursing bullying, sparked societal debates on workplace bullying and employee suicides23. Subsequently, in 2021, ‘the Anti-bullying Legislation’, an amendment to the Labor Standards Act, was enacted23. Despite the implementation of legislative measures, a comprehensive analysis of work-related disease certificates related to suicide, conducted by the Korea Workers’ Compensation and Welfare Service in 2022, revealed that among the approved cases of 39 suicides, ‘workplace bullying and harassment’ was identified as the leading cause, accounting for 33%24. In terms of the specific criteria of workplace bullying within the law, there is an argument that emphasize the need for a distinction between one-time and sustained, repetitive bullying5.

Furthermore, previous studies have shown that workplace bullying manifests differently based on sex25,26, age27, job rank28, and the type of workplace28,29. Women are more frequently exposed to emotional bullying, while men are more likely to experience physical threats25,26. Younger employees in lower-ranking positions are often subjected to directive bullying, whereas managers are frequently exposed to derogatory remarks or intentional disregard27,28. Additionally, in private companies, performance-driven bullying is notably prominent28,29. Factors like marital status28, level of education28, working hours28, pre-existing depression30, and burnout30,31 can also modulate the risk of suicidality, underscoring the need for their inclusion in comprehensive evaluations.

Previous global studies have confirmed that workplace bullying not only affects individuals’ mental health but also increases long-term sickness absences, job turnover, early retirement, and unemployment leading to substantial economic loss for both organizations and society11,32,33. Moreover, in the worst-case scenarios, workplace bullying precipitates a decline in the productive population through suicide.

Despite its negative impact on South Korea as a whole, research on the relationship between workplace bullying and suicide remains limited. Studies on bullying in South Korea have so far been confined to specific groups such as in schools or among nurses and physicians-in-training34,35,36. Additionally, studies encompassing patterns of bullying and suicidality by sex, including suicide attempts, not just ideations, are challenging to find. Furthermore, while depression is a well-known significant risk factor for suicide37, whether the association between workplace bullying and suicide originates from depression remains unclear. Thus, this study aims to (1) investigate the association between workplace bullying and suicide ideation and attempts, (2) determine how suicidality risk varies based on the frequency of bullying, and (3) explore association differences based on depression presence.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

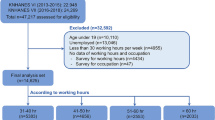

We conducted a cross-sectional study including a diverse group of 13,620 employees, aged 19 to 65 years, who participated in workplace mental health screenings at the Workplace Mental Health Institute of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea, between April 20, 2020 and November 23, 2022. Among the 13,620 respondents, we excluded a total of 1079 participants due to incomplete information on sociodemographic data (Education/Marital status, n = 224/224) or Monthly income (n = 1056) or workplace bullying (n = 37). The characteristics of excluded participants are presented in comparison to those of included participants (Supplement Table 1). We performed a sensitivity analysis by treating missing values as “unknown.” A total of 12,541 participants, comprising 7889 men and 4652 women, voluntarily agreed to participate in mental health examinations at the request of their respective companies. The participants were employees working in a total of 26 public institutions or large corporations, which encompass sectors such as finance, insurance, real estate, public administration, services, wholesale trade, and construction. The Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study (Approval number: 2022-03-046) and waived the requirement for informed consent as this study used de-identified routine health screening data. All methods of the study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

Assessments

The outcomes of interest were suicide ideation and attempts, and the predictor was the presence of workplace bullying and its frequency.

Socio-demographic factors

Socio-demographic factors included age, sex, education level (high school graduate or below, university graduate, master’s degree, and doctorate degree), and marital status (married, unmarried, or other [divorced, widowed, or separated]).

Job-related demographic factors

Job-related demographic factors encompassed the type of job (government/public sector or private sector), the duration of employment at the current workplace (in years), weekly work hours, and monthly income quartiles (below 3 million KRW, 3 million KRW to under 4 million KRW, 4 million KRW to under 6 million KRW, and above 6 million KRW).

Clinical characteristic factors

Depressive symptoms in the past 7 days were assessed using the Korean version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale38,39, a self-reported questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The study’s CES-D Cronbach’s alpha was 0.765. Traditionally, a CES-D score of 16 or higher has been used as a depression screening threshold40. Hence, individuals with a CES-D score of 16 or higher were identified as experiencing depression.

Workplace bullying was assessed by asking participants the following question: “In the past year, have you experienced bullying at work, such as intentional humiliation, harassment, or verbal abuse, or deliberate social exclusion, such as being ostracized or ignored?” Based on exposure frequency, workplace bullying was categorized as ‘Not Bullied’, ‘Occasionally Bullied’ (monthly or less), and ‘Frequently Bullied’ (weekly or daily).

Suicidal ideation and attempt were assessed separately using adapted two-item self-rated questionnaires from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey41. Participants were queried about serious thoughts of suicide and actual suicide attempts in the past year. Suicidal ideation and attempt were defined as any thoughts of suicide and attempted suicide within the preceding year, respectively.

Burnout was measured using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI), a 16-item self-rated questionnaire widely employed to assess burnout in various occupations42. The OLBI evaluates two key burnout dimensions: exhaustion and cynicism, each comprising eight items scored on a five-point Likert scale. The presence of exhaustion and cynicism was determined based on OLBI scores higher than the mean plus one standard deviation among all participants43.

Statistical analysis

The study groups’ baseline characteristics were compared using independent t-tests for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to analyze the association between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation, in which the first model was univariate, successively incorporating adjustments for sociodemographic factors (age, sex, marital status, education), occupational factors (type of job, working hours, job duration, and monthly income), and clinical characteristics (depression, exhaustion, and cynicism). Variables were manually selected and added to the model in a sequential approach. To examine the association between workplace bullying experiences and suicidal ideation as well as suicidal attempts according to depression status, multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted, adjusting for potential confounding variables. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine whether the odds ratios of the adjusted models for having suicidal ideation differed by sex, age, income, and depression among participants exposed to workplace bullying. The interactions by age, sex, income, and depression differences were carried out using the likelihood ratio test. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (Approval number: KBSMC 2022-03-046) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Informed consent was waived as the study used de-identified routine health screening data.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Among 12,541 participants, comprising 7889 males (62.9%) and 4652 females (37.1%), the CES-D and the burnout scores in both exhaustion and cynicism dimensions were higher among females. The prevalence of workplace bullying was 18.7% among females and 10.6% among males, signifying significantly more reported exposure to workplace bullying among females (p < 0.001). The reported rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (all p < 0.001) were also significantly higher among females.

Increased suicidal ideation linked to workplace bullying

The results presented in Table 2 show that participants who had experienced workplace bullying were at higher odds of suicidal ideation compared to those who had not been bullied. In the univariate model, employees that had been occasionally bullied had an odds ratio (OR) of 2.73 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.40–3.10, p < 0.001), and employees that had been frequently bullied had an OR of 4.65 ([CI] = 3.59–6.03, p < 0.001), indicating a significant increase in risk with increasing exposure to workplace bullying. In the adjusted model, occasionally bullied employees had an OR of 1.47 ([CI] = 1.27–1.69, p < 0.001), and frequently bullied employees had an OR of 1.81 ([CI] = 1.36–2.40, p < 0.001), indicating a consistent increase in risk for both groups. The odds decreased progressively with the addition of covariates, but the suicide risk for occasionally bullied and frequently bullied employees remained consistently higher than for those who had not been bullied. The sensitivity analysis, which included missing values, confirmed results consistent with the primary analysis. (Supplement Table 2)

Factors in suicidal ideation among the participants with and without depression

Table 3 presents the results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis examining factors related to suicidal ideation among the total participants and groups with and without depression. Among all participants, being female, aged 30–49 years, having a high school education or lower, being unmarried, working in a private company, and the presence of burnout were all factors found to have higher odds of suicide ideation. Among the group later determined to have depressive symptoms, the odds of suicidal ideation were 6.13 times ([OR] = 6.13 [5.36–7.02]) higher. In this group, the odds of suicidal ideation among both occasionally ([OR] = 1.41 [1.21–1.64]) and frequently bullied employees ([OR] = 1.84 [1.37–2.47]) were significantly higher than among those not bullied. Among those that were not later determined to have depressive symptoms, the odds of suicidal ideation were significantly higher in occasionally bullied employees for workplace bullying ([OR] = 1.88 [1.31–2.69]).

Subgroup analysis of workplace bullying exposure and suicidal ideation

Figure 1 explored the association between history of workplace bullying exposure and the prevalence of suicidal ideation in subgroups categorized by age, sex, income, and depression status. Both male and female employees who experienced bullying showed higher odds of having suicidal ideation compared to those who did not ([OR] for male employees, 1.78 [1.48–2.15]; for female employees, 1.29 [1.08–1.55]). Notably, male employees who experienced bullying had a significantly stronger association with suicidal ideation compared to female employees (p for interaction < 0.001). Additionally, workplace bullying showed a higher association with suicidal ideation among employees under the age of 50 and those with a monthly income of less than 6 million KRW. Although the association tended to decrease with increasing age, this did not reach statistical significance (p for interaction = 0.069). Finally, there was a tendency toward a stronger association with suicidal ideation among employees without depression ([OR] = 1.86 [1.31–2.62]) compared to those with depression ([OR] = 1.47 [1.28–1.69]), although not statistically significant (p for interaction = 0.082).

Factors in suicide attempts among the participants with and without depression

Table 4 displays the results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis examining factors related to suicide attempts among all participants and groups with and without depression. Among all participants, being female, having a high school education or lower, working in a private company, and having shorter working hours were associated with higher odds of suicidal attempts. The presence of depression increased the odds of a suicide attempt by 5.07 times ([OR] = 5.07 [2.55–10.08]). Occasionally bullied and frequently bullied employees had a 2.27-fold increase ([OR] = 2.27 [1.34–3.85] and a 4.43-fold increase ([OR] = 4.43 [2.13–9.21]), respectively, in the odds of suicide attempt compared with those who had not been bullied. In the depression group, significant increases in suicide attempt odds were observed among the occasionally bullied ([OR] = 2.15 [1.24–3.73]) and frequently bullied ([OR] = 4.09 [1.92–8.71]). In the non-depression group, a significant increase in suicide attempt odds was observed for frequently bullied employees ([OR] = 13.30 [1.50–118.04]).

Discussion

This study brings to light a stark escalation in the risk of suicide among individuals subjected to workplace bullying. It substantiates a clear nexus between workplace bullying and suicidality, in individuals both with and without depression states. The association between exposure to workplace bullying and suicide ideation was more pronounced among males, age 19–29, without depression. To the best of our knowledge, this pioneering study is the first in South Korea to investigate workplace bullying, suicidality, and their association with depression.

Aligning with a comprehensive meta-analysis reporting a global prevalence of workplace bullying at 14.6%43, this study unveiled alarming rates among females at 18.7% and males at 10.6%. Reports of bullying exposure were notably more frequent among female employees. Female respondents indicated higher mean depression and burnout scores and suicidality than their male counterparts. These findings echo previous research highlighting a heightened tendency for females to report workplace bullying, regardless of their occupational field44. They also correspond with previous studies reporting higher rates of mood disorders45, suicidality among women26. This appears to be attributed to sex differences associated with hormonal influences, stress from traditional female roles such as childbirth and childcare, coping mechanisms, and the extent of reporting to external sources26,45.

This study found that, compared to individuals who had not been exposed to workplace bullying, those who had been occasionally bullied and frequently bullied had respective odds of 1.47 and 1.81 for suicidal ideation, and respective odds of 2.27 and 4.43 for suicidal attempts after adjusting for possible confounding variables. Prior research over the past two decades has hinted at a positive link between workplace bullying and suicide8,9,10,12,14,46. However, most existing studies have been cross-sectional, complicating the establishment of causal relationships. Yet, a longitudinal cohort study in Norway encompassing 1846 employees observed over the period from 2005 to 2010 found that exposure to workplace bullying nearly doubled the chances of contemplating suicide within two to five years (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 2.05; CI = 1.08, 3.89; p < 0.05)47. Moreover, population-based studies utilizing national patient registers in countries like Australia, Denmark, Sweden, and Japan consistently indicated that exposure to workplace bullying heightened the risk of suicidal ideation8,9,10,14,46. In contrast, within Korea, studies exploring the connection between bullying and suicide predominantly focused on vulnerable groups like adolescents, the elderly, or specific occupations such as nursing, or physicians-in-training34,35,36. This study, harnessing health examination data from a healthy cohort of Korean employees, not only represented the office workforce but also examined exposure frequency, a realm previously underexplored.

The conceptualization of the association between workplace bullying and suicide can be drawn from various cases and theories. In an Italian prospective study, 48 targets of workplace bullying exhibited increased scores on the MMPI-2 scale’s Hs, D, Hy, and Pa items 22 months later, along with high rates of suicidality7. Numerous studies have demonstrated that individuals exposed to workplace bullying have increased rates of mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, leading to suicide3,4,48,49,50. According to the Stress as Offense to Self (SOS) perspective, a theory within workplace bullying, self-worth comprises self-esteem and social esteem. Constructive social relations at work imply one’s worth, capability, and value, whereas bullying undermines self-worth51. Secondly, the Interpersonal Theory suggests that bullying, by deconstructing self-worth, leads to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, ultimately escalating suicidal desires52. Repeated exposure to workplace bullying continually exposes individuals to fear or distress through opponent processes and habituation, leading to create a ‘capability to die’. Intriguingly, individuals frequently exposed to workplace bullying have been found to exhibit higher salivary DHEA levels53, lower cortisol levels10, and down-regulation of β2 adrenergic receptors (ADRB2)54,55,56. These physiological changes observed in individuals experiencing workplace bullying suggest the presence of underlying mechanisms that may mediate the association between workplace bullying and suicidality.

An important finding of this study is the robust association between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation regardless of depression status. The odds of suicidal ideations due to workplace bullying were 1.47 for the depressed group and 1.86 for the non-depressed group, indicating a higher likelihood in the non-depressed group. Mood disorders are independently associated with an approximately 5 to 6-fold increase in the odds of suicidality37, and similarly, the association between workplace bullying and suicidality may weaken in individuals with depression in this study. Unlike previous research suggesting that workplace bullying might lead to suicidal thoughts and attempts via significant mood disorders7,36, this study indicates workplace bullying might be associated with suicidality even if depressive symptoms were not present at the time the questionnaire was applied. According to the Integrated Motivational-Volitional (IMV) model, after exposure to bullying, suicide attempts occur, which progress through three stages: phase 1—the premotivational phase of exposure to background factors and triggering events; phase 2—the motivational phase of repeated bullying leading to suicidal intent formation; and phase 3—the volitional phase of increased suicidal thoughts transitioning to attempts57. These mechanisms showcase how workplace bullying can instigate defeat and entrapment, leading to suicide attempts. This study is the first to propose the possibility of an association of workplace bullying with suicide among working individuals even when depressive symptoms were not later determined to be present. Furthermore, it highlights a new necessity to assess exposure to workplace bullying beyond depression states to develop effective strategies for preventing workplace suicide.

This study confirmed an increase in suicidal ideation among both men and women exposed to workplace bullying, yet it identified men as more vulnerable than women in sub-analysis. Moreover, there was a trend indicating higher susceptibility among younger individuals (below 50 years) and those in the income bracket of less than 6 million KRW. Studies examining the gender association between workplace bullying and mental health have been inconsistent, but studies conducted in Italy and Korea have pointed to a stronger association in male employees. It might be because men’s mental health appears to be focused within the workplace and the societal pressure for men (masculinity) to endure bullying may contribute to a higher reporting threshold5,58. Additionally, lower-level middle managers may be at higher risk of deteriorating mental health due to workplace bullying as presumed from age and income perspectives. This might correlate with studies that suggest high vulnerability among less skilled apprentices exposed to workplace bullying, as they are unable to advocate for themselves within hierarchical structures59.

This study identified suicide-related risk factors, indicating that suicidal ideation risk was associated with being female, age 30–49, high school-level education, being unmarried, working in the private sector, having depression and/or burnout, and being exposed to bullying. Similarly, suicidal attempt risk was associated with female, high school-level education, working in the private sector, having shorter working hours, being depressed, and being exposed to bullying. These findings align with those of a study across 17 countries in the Americas, Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, which showed a higher association between suicidal behavior and risk factors such as being female, unmarried, a high school graduate level education, experiencing depression, and experiencing burnout37. Moreover, this study found significantly higher suicidality in the private sector compared to in the public sector. Research in India indicated higher depression levels in the private sector29, and an analysis of US government reports found 222 out of 270 occupational suicides were in the private sector60. In South Korea, the corporate culture in the private sector emphasizes profit maximization, cost-cutting and fostering competition61, potentially heightening workplace tension and impacting employees’ mental health due to job insecurity.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, due to the cross-sectional survey design, causality cannot be established. While workplace bullying and suicidality are events identifiable within a one-year timeframe, depression is conceptualized as an episode, requiring assessment of depressive states in a more recent period, such as the past 1–2 weeks. Consequently, further longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether workplace bullying poses suicide risks independently of depression. Secondly, this study included data only from workers undergoing mental health check-ups in companies or institutions, predominantly analyzing employees from specific industry companies, potentially incurring selection biases. Subsequent studies with representative worker samples are required to validate generalizability. Thirdly, key variables such as workplace bullying, depression, and suicide were evaluated through self-reported surveys, which may expose response biases. Fourthly, the burnout questionnaire used in this study consists of a single item, making it challenging to assess various types such as harassment, gender discrimination, public humiliation, salary reduction, and personal tasking.

Conclusion

This study marks the first confirmation of the association between workplace bullying and suicide ideation or attempts among workers without depression. It underscores the importance of identifying bullying experiences, irrespective of depression, to assess suicide risks among employees and suggests a need for a more detailed evaluation among male employees. The implementation of organizational policies and occupational healthcare initiatives addressing workplace bullying is postulated to be instrumental in mitigating work-related suicides.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Mental Health at Work (World Health Organization, 2022).

León-Pérez, J. M., Escartín, J. & Giorgi, G. The presence of workplace bullying and harassment worldwide. Concepts Approaches Methods, 55–86 (2021).

Balducci, C., Alfano, V. & Fraccaroli, F. Relationships between mobbing at work and MMPI-2 personality profile, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and suicidal ideation and behavior. Violence Vict. 24, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.52 (2009).

Brousse, G. et al. Psychopathological features of a patient population of targets of workplace bullying. Occup. Med. (Lond). 58, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm148 (2008).

Jung, S. et al. Gender differences in the association between workplace bullying and depression among Korean employees. Brain Sci. 13, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13101486 (2023).

Nielsen, M. B. & Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: a meta-analytic review. Work Stress 26, 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.734709 (2012).

Romeo, L. et al. MMPI-2 personality profiles and suicidal ideation and behavior in victims of bullying at work: a follow-up study. Violence Vict. 28, 1000–1014. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00092 (2013).

Tsuno, K. & Tabuchi, T. Risk factors for workplace bullying, severe psychological distress and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic among the general working population in Japan: a large-scale cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12, e059860. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059860 (2022).

Conway, P. M. et al. Workplace bullying and risk of suicide and suicide attempts: a register-based prospective cohort study of 98 330 participants in Denmark. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 48, 425–434. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4034 (2022).

Magnusson Hanson, L. L., Nyberg, A., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Bondestam, F. & Madsen, I. E. H. Work related sexual harassment and risk of suicide and suicide attempts: prospective cohort study. BMJ 370, m2984. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2984 (2020).

Nielsen, M. B., Einarsen, S., Notelaers, G. & Nielsen, G. H. Does exposure to bullying behaviors at the workplace contribute to later suicidal ideation? A three-wave longitudinal study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health, 246–250 (2016).

Leach, L. S., Poyser, C. & Butterworth, P. Workplace bullying and the association with suicidal ideation/thoughts and behaviour: a systematic review. Occup. Environ. Med. 74, 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-103726 (2017).

Follmer, K. B. & Follmer, D. J. Longitudinal relations between workplace mistreatment and engagement—the role of suicidal ideation among employees with mood disorders. Organ. Behav. Hum. 162, 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.12.002 (2021).

Milner, A., Page, K., Witt, K. & LaMontagne, A. Psychosocial working conditions and suicide ideation: evidence from a cross-sectional survey of working australians. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 58, 584–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000700 (2016).

Denison, D. R., Haaland, S. & Goelzer, P. Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness: is Asia different from the rest of the world? Organ. Dyn. 33, 98–109 (2004).

McMahon, E. M. et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric factors preceding death by suicide: a case-control psychological autopsy study involving multiple data sources. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 52, 1037–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12900 (2022).

Phillips, M. R. et al. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet 360, 1728–1736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3 (2002).

Hyung-ki, P. Korean miracle 70 years in the making. Korea Herald (2015). https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20150816000246

Kleiner, J. Korea, A Century of Change (World Scientific, 2001).

OECD. Hours worked (indicator) (2023).

OECD. Suicide rates (indicator) (2024).

Statistics Korea. The Outcome of the Causes of Death Statistics (National Statistical Office, 2022).

Park, S. Workplace harassment in South Korea: evaluation and improvement measures for the workplace anti-bullying law. Asian Perspect. Workplace Bullying Harassment, 277–304 (2021).

Korea Workers’ Compensation and Welfare Service. Work-related disease diagnosis committee disease-specific decision status Workplace Compensation and Welfare Service (2022).

Maidaniuc-Chirilă, T. Gender differences in workplace bullying exposure. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 27, 139–162 (2019).

Canetto, S. S. & Sakinofsky, I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 28, 1–23 (1998).

Turney, L. Mental health and workplace bullying: the role of power, professions and ‘on the job’ training. Aust e-J. Adv. Mental Health 2, 99–107 (2003).

Alonso, J. et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 192, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 (2008).

Kumar, S., Singh, T. & Singh, V. A comparative study of mental health issues among private and public sector employees in Delhi NCR. Delhi Psychiatry J. 24, 124–132 (2021).

Yun, J. Y., Myung, S. J. & Kim, K. S. Associations among the workplace violence, burnout, depressive symptoms, suicidality, and turnover intention in training physicians: a network analysis of nationwide survey. Sci. Rep. 13, 16804 (2023).

Oh, D. J. et al. Examining the links between burnout and suicidal ideation in diverse occupations. Front. Public Health 11, 1243920 (2023).

Glambek, M., Skogstad, A. & Einarsen, S. Take it or leave: a five-year prospective study of workplace bullying and indicators of expulsion in working life. Ind. Health 53, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2014-0195 (2015).

Hogh, A., Hoel, H. & Carneiro, I. G. Bullying and employee turnover among healthcare workers: a three-wave prospective study. J. Nurs. Manag. 19, 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01264.x (2011).

Kim, Y. S., Leventhal, B. L., Koh, Y. J. & Boyce, W. T. Bullying increased suicide risk: prospective study of Korean adolescents. Arch. Suicide Res. 13, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110802572098 (2009).

Roh, B. R. et al. The structure of co-occurring bullying experiences and associations with suicidal behaviors in Korean adolescents. PLoS One 10, e0143517. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143517 (2015).

Yun, J. Y., Myung, S. J. & Kim, K. S. Associations among the workplace violence, burnout, depressive symptoms, suicidality, and turnover intention in training physicians: a network analysis of nationwide survey. Sci. Rep. 13, 16804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44119-1 (2023).

Nock, M. K. et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry. 192, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 (2008).

Heo, E. H., Choi, K. S., Yu, J. C. & Nam, J. A. Validation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 15, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2017.07.19 (2018).

Noh, S., Kaspar, V. & Chen, X. Measuring depression in Korean immigrants: assessing validity of the translated Korean version of CES-D scale. Cross Cult. Res. 32, 358–377 (1998).

Roberts, R. E., Andrews, J. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Hops, H. (1990). Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.2.2.122

Lee, E. et al. Development of the stress questionnaire for KNHANES: report of scientific study service. Korea Centers Dis. Control Prev. (2010).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512 (2001).

Delgadillo, J., Saxon, D. & Barkham, M. Associations between therapists’ occupational burnout and their patients’ depression and anxiety treatment outcomes. Depress. Anxiety 35, 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22766 (2018).

Maidaniuc-Chirilă, T. Gender differences in workplace bullying exposure. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 27 (2019).

Seedat, S. et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36 (2009).

Routley, V. H. & Ozanne-Smith, J. E. Work-related suicide in Victoria, Australia: a broad perspective. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 19, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2011.635209 (2012).

Nielsen, M. B., Nielsen, G. H., Notelaers, G. & Einarsen, S. Workplace bullying and suicidal ideation: a 3-wave longitudinal Norwegian study. Am. J. Public Health. 105, e23–e28. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302855 (2015).

Lahelma, E., Lallukka, T., Laaksonen, M., Saastamoinen, P. & Rahkonen, O. Workplace bullying and common mental disorders: a follow-up study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 66, e3. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.115212 (2012).

Hansen, A. M., Hogh, A. & Persson, R. Frequency of bullying at work, physiological response, and mental health. J. Psychosom. Res. 70, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.05.010 (2011).

Kabir, H. et al. Association of workplace bullying and burnout with nurses’ suicidal ideation in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 13, 14641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41594-4 (2023).

Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. & Elfering, A. H. Occupational stress research: the stress-as-offense-to-self perspective (2007).

Van Orden, K. A. et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 117, 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697 (2010).

Lac, G., Dutheil, F., Brousse, G., Triboulet-Kelly, C. & Chamoux, A. Saliva DHEAS changes in patients suffering from psychopathological disorders arising from bullying at work. Brain Cogn. 80, 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2012.07.007 (2012).

Bierhaus, A. et al. A mechanism converting psychosocial stress into mononuclear cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1920–1925. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0438019100 (2003).

Rajalingam, D. et al. Repeated social defeat promotes persistent inflammatory changes in splenic myeloid cells; decreased expression of beta-arrestin-2 (ARRB2) and increased expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6). BMC Neurosci. 21, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-020-00574-4 (2020).

Rajalingam, D. et al. Workplace bullying increases the risk of anxiety through a stress-induced beta2-adrenergic receptor mechanism: a multisource study employing an animal model, cell culture experiments and human data. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 94, 1905–1915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01718-7 (2021).

O’Connor, R. C. & Kirtley, O. J. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 373, 20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268 (2018).

Nolfe, G., Petrella, C., Zontini, G., Uttieri, S. & Nolfe, G. Association between bullying at work and mental disorders: gender differences in the Italian people. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 45, 1037–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0155-9 (2010).

Turney, L. Mental health and workplace bullying: the role of power, professions and ‘on the job’ training. Aust. J. Adv. Ment. Health 2, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.2.2.99 (2014).

Germain, M. L. Work-related suicide: an analysis of US government reports and recommendations for human resources. Empl. Relat. 36, 148–164 (2013).

Yongjin Kim, H. K. & Ryu, S. A comparative study of organizational culture between public and private companies pursuing knowledge management. Conf. Proc. Korean Local Gov. Assoc., 16 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors received no external funding for this research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S.K. conceptualized the study design, performed statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript. Y.C.S., K.-S.O., and D.-W.S. assisted with the study conceptualization. E.S.K. also handled data curation and validation, with support from D.J.O., S.J.C., and S.-W.J. D.J.O., S.J.C., and S.-W.J. contributed to the formal analysis and methodology. J.K. participated in the investigation. E.S.K. handled visualization. J.K., S.J.C., and S.-W.J. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, E.S., Oh, D.j., Kim, J. et al. Revealing the confluences of workplace bullying, suicidality, and their association with depression. Sci Rep 15, 6920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87137-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87137-x