Abstract

In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which strive to ensure comprehensive access to fundamental water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services, it is extremely imperative to prioritize communities in need and still disadvantaged. Moreover, tackling the worldwide sanitation crisis entails advancing the development of productive and sustainable sanitation systems and infrastructure. Sanitation planning is a multidimensional exercise encompassing multiple dimensions, stakeholders, and strategies, typically with conflicting objectives. Poor planning, funding obstacles, stakeholder priorities, climatic changes, growing populations, system constraints, and user engagement all complicate the entire process. Intelligent strategic decision-making is crucial, particularly for resource-constrained economies. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) models offer opportunities to figure out and resolve such conflicts, while also optimizing prioritization and policymaking. These models assist with considering trade-offs, data uncertainty, and arriving at decisions by considering technical, economic, social, and environmental sustainability. In the present work, a two-stage integrated model of the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) and the Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Technique (FSET) was developed, accompanied by a sensitivity analysis, yielding an assessment index designated as the Sanitation Priority Index (SPI). This index is particularly applicable in prioritizing and categorizing communities in need of sanitation infrastructure (e.g., wastewater collection systems and treatment plants), considering competition over scarce resources, reliance on third-party funds, and sustainability factors. The decision-making problem was designed as a hierarchical structure that integrates all problem elements and specifies the key criteria contributing to the SPI. Fuzzy set theory handles data uncertainty, with FAHP evaluating criteria significance in a group decision-making context and FSET designing criteria membership functions. Field data on criteria contributing to the SPI is transformed into fuzzy intervals, synthesized, and defuzzified to derive the SPI at community level. The model’s robustness is examined using sensitivity analysis as it is applied to several Palestinian communities lacking sanitation infrastructure. The outcomes show that the demographic criterion has the major impact on the SPI (20.38%), followed by water consumption (16.76%) and wastewater reuse potential (15.40%). Environmental risks account for 12.40%, utilities’ competency (11.5%), and industrial wastes risks (8.72%). The socioeconomic context is valued at 5.10%, geographical constraints at 4.51%, and license constraints at 4.8%. Out of the 25 communities investigated, five exhibited SPI values surpassing 60.0%. Eleven communities possessed SPI values between 50.0% and 60.0%, and nine achieved SPI values ranging from 40.0 to 50.0%. The sensitivity analysis application reveals almost complete stability in prioritizing communities. Introducing this model into relevant bodies’ sanitation management practices and planning strategies holds the potential to significantly boost sustainable sanitation services as well as the performance of water and wastewater utilities. It further enables the incorporation of additional criteria and the interests of more stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water and sanitation services are imperative to public health and fundamental living survival. Among the most significant challenges of today’s world is ensuring their prevalent, complete, and lasting universalization1. Considering outstanding technological advances in the recent past, a substantial proportion of the globe’s population still lacks the luxury of water and sanitation resources1. These disparities constitute an array of challenges to the global community, which is struggling to arrive at a compromise on the inalienability underlying this basic right, hampering effective options2. The United Nations (UN) enacted the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) and, subsequently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to make sure the availability, affordability and sustainability of water and sanitation services for all1. According to the United Nations3, billions of people worldwide are lacking access to clean water or sanitation, with 2.2 billion and 4.2 billion, respectively, without these services. Annually, approximately 800,000 people die from diarrhea as a consequence of contaminated water and ineffective sanitation services4. The hurdles that these services encounter are not primarily attributed to technological or physical limitations, instead owing to a governance issues triggered by inadequate financial practices, poor management, economic policies, deficient legislations, etc5. Regardless of globally endeavors to eradicate the imbalances in these services between developed and developing nations, major gaps endure, attributed largely to socio-economic considerations6.

Regarding sanitation sector, poor services undermine both human well-being and environmental sustainability7. This concern grows more severe in developing countries, where insufficient accessibility, growth in populations, technical challenges, financial deficiencies, and unplanned developments all retard the introduction of sustainable sanitation services. The sanitation infrastructures, primarily, in developing countries struggle to keep up with the rapid population growth8. The relevance of wastewater management is stressed in SDG6-Target 6.3, which intends to decrease untreated wastewater by 50% by 2030. Despite global endeavors, only one-quarter of SDG6 advancement has been made, with 50% of the worldwide population lacking proper sanitation, including 25% without basic services9.

In low–and middle–income countries, 80–90% of wastewater is released into water bodies untreated10. Poorly managed wastewater harms water11, and insufficient sanitation accounts for 80% of infections in developing countries8,12. Over 2.7 billion people operate septic systems13, which contaminate groundwater pollution and introduce hazardous pollutants like nitrogen14,15. High nitrate levels can cause health problems16, and sewage contributes to marine eutrophication17. Therefore, managing sewage pollution is vital to mitigate the potential risks to both the environment and the public17.

Sanitation services planning implies numerous dimensions, multiple stakeholders with different interests, and different strategies. This multifaceted process frequently features competing objectives, demanding strategic decision-making at the initial planning phase. In this context, various standards and multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) techniques are becoming more prevalent for wastewater and sanitation planning, including several MCDA models and frameworks developed in the recent past18. In resource-limited economies (i.e., developing countries), improper planning, funding deficiencies, distinct stakeholders’ preferences and interests, climatic changes, growth in populations, systems’ functioning needs, and user awareness and backing of sanitation services hamper policymakers’ functions. These complications pose a challenge to define priorities, utilize available resources, and prioritize communities in need for such services9. A successful strategy in this regard requires taking all the environmental, social, economic, and technical components of long-term sanitation services’ sustainability into account. Consequently, MCDA enables the evaluation of trade-offs between competing criteria spanning multiple dimensions of sustainability, as such empowering decision making19,20,21. MCDA systems are quantitative decision-making models that compare and assess distinct decision alternatives considering typically an array of evaluation criteria22.

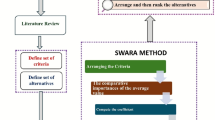

In the present study, we applied a two – stage integrated model of the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP), and the Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Technique (FSET) extended by a sensitivity analysis to develop an assessment index designated as the Sanitation Priority Index (SPI). This index is especially powerful towards prioritizing and sorting communities in need of sanitation services (i.e. wastewater collection systems and treatment plants), considering the competition over limited resources, reliance on external funding, and sustainability attributes. These tools were decided on given their robust mathematical features, functionality in handling both qualitative and quantitative data, performance in managing uncertainty, as well as their potential for structuring multidimensional and complicated decision–making problems applying the hierarchy module. Even though other MCDA models, including Preference Ranking Organization and Method for Enrichment Evaluation (PROMETHEE), Elimination and Choice Expressing Reality (ELECTRE), etc., are well-structured and deliver consistent outcomes, some are being critiqued over their evaluation techniques, which tend to be seen as vague and challenging for Decision Makers (DMs) when applied to different water resources management problems23. Diverse MCDA techniques applied to a similar decision-making problem often give comparable outcomes, particularly when experts possess substantial knowledge24,25. In other cases, comparing AHP and AHP-PROMETHEE, for example, revealed identical conclusions, differing only in ranking pattern26. Accordingly, crucial considerations for determining MCDA technique include problem complexity, expertise of experts, criteria management, ease of implementation, and interpretability. The techniques applied in the present analysis, particularly FAHP, are flexible, capable of handling complicated problems, and generate reliable outcomes under uncertain conditions24,27.

The decision-making problem followed a structure of a hierarchical module that incorporates all problem’s dimensions and determines the key criteria contributing to the SPI, involving physical, operational, environmental, and socio-economic parameters. Fuzzy set theory is applied to cope with the inherent uncertainty associated with used data. The FAHP is employed to determine the significance of the proposed criteria under a group decision-making context, while the FSET serves to design the criteria’s membership functions. This technique further transforms field data for selected communities to be prioritized into fuzzy intervals, synthesizes each community performance, subsequently defuzzifies the outcomes to arrive at the SPI for every community. Finally, the model is subjected to sensitivity analysis to appraise its robustness.

The objective of this work intends to support wastewater utilities, specifically in developing regions, to exercise planned and well-structured decisions regarding the communities having the most need of sanitation services and infrastructure. The model’s novelty and practical utility are demonstrated by its potential to induce effective allocation of limited resources consistent with community priorities and policymakers’ interests and contribute to more effective and long-term solutions for sanitation planning. To showcase the tangible utilization, the developed model is tested in Palestine, a typical developing region, paying attention to several communities that have no sanitation infrastructure along with different features. This holistic methodology addresses a gap in present decision-making models in the subject matter by delivering a systematic, adaptable, and context-specific instrument for prioritizing sanitation needs, mainly in developing regions.

The subsequent sections of the present work are organized as follows: Sect. 2 explores previous research works, Sect. 3 summarizes the materials and methods being utilized, Sect. 4 outlines the case study, Sect. 5 delivers the results and analyzes the major outcomes, and the final section, Sect. 6, summarizes the conclusions drawn.

Related works from literature

Recognizing that wastewater collection networks and treatment facilities are regarded among the most essential and costly municipal infrastructure assets, while also being crucial for public health and socio-economic advancement, effective utilization of resources is imperative. Introducing sanitation services and infrastructures in underserved communities demands an in-depth investigation of relevant criteria and rational decision-making. Comprehensive assessment and prioritizing procedures, including reliable prediction models, are significant for effectively identifying communities’ needs. Such procedures should incorporate human knowledge, experiences and opinions by experts28. Some models have been devised to analyze the overall performance of urban infrastructure systems. These models attempt to establish efficient strategies for planning infrastructure relied on performance and costs of investments29.

In this context, Khatri, et al.29 developed a performance index for urban infrastructure systems using the FSET. This index utilizes an array of evaluation criteria, including community concerns, regulatory concerns, service reliability, along with several performance indicators. The model was applied to four systems in Kathmandu, Nepal to test its applicability. Marcelo, et al.30 proposed the infrastructure prioritization framework, an MCDA model that prioritizes infrastructure projects considering social, environmental, financial and economic factors. The methodology correlates with policy goals, integrates criteria into indexes, and has been found to be effective in enabling utilities at allocating scarce funds for infrastructure projects in the context of funding deficiencies.

Matos, et al.18introduced a MCDA model for selecting the most appropriate sanitation services at early planning stages, considering technical, economic, environmental, and social dimensions. The developed model has been tested in four regions of Angola with the objective of offering broad sanitation coverage using sewer systems, pit latrines, septic tanks, and offsite treatment. Ibrahim and Ali31 applied a MCDA model to decide on the most appropriate wastewater management solutions for Khartoum city, Sudan. They concluded that decentralized wastewater management strategies are ecologically sound, sustainable, adaptable, reliable, and affordable, whereas centralized solutions tend to be costly and challenging for rapidly expanding cities.

Jararaa32 developed a MCDA model to assist with prioritizing regions in need of wastewater sanitation services in Palestine. In this model, a set of criteria impacting the decision-making process in the sanitation sector, including demography, water consumption, wastewater production, wastewater reuse, etc., was proposed and evaluated by a group of experts to determine its significance. Despite the potential of this model for handling the decision problem under exploration, it relied on simple scoring strategy that neglected to account for the associated data uncertainty. In this approach, experts were tasked with scoring an array of evaluation criteria on a scale of 1 to 9. This strategy is ineffectual for ambiguous decision scenarios, which are standard in the real world, because it assesses multiple criteria simultaneously. In contrast, the proposed model in the present work incorporates mathematics and psychology to evaluate multiple criteria and determine the most significant ones. It manages this issue by pairwise comparison, which enables two criteria to be compared at once following organizing the tested evaluation criteria into matrices. It further manages uncertainty using fuzzy set theory. As it is clear, the subject under investigation has drawn relatively little attention in the literature. This present work is the first study of its kind to investigate the challenge of prioritizing sanitation services using an integrated and holistic approach that accounts for decision-making under uncertainty, local conditions, and sustainability dimensions.

Materials and methods

Sanitation Priority Index (SPI) framework

A hierarchical model with several levels is suggested to handling the decision problem featuring competing priorities. This technique organizes the complicated problem into sub-problems, enabling DMs to appraise options considering specific sets of criteria at various levels of detail. The model mimics a tree, having the root expressing the overarching objective and the descendant nodes implying evaluation criteria. Such criteria are applied for assessing options/alternatives in the most basic level of the model’s hierarchy. The complexity of the problem determines the number of criteria and sub-criteria levels required. Developing an objective decision-making model demands an exhaustive review of the literature, consultation with experts, thinking about all problem dimensions, and a comprehension of the local context. Handling these concerns implies that the developed model can potentially be executed effectively. Furthermore, straightforward targets must be fulfilled by the proposed model. In the present case, the key objective is to figure out communities in need of sanitation services and wastewater infrastructure, prioritizing those communities considering limited resources, and maintain an acceptable compromise among social, economic, technical, and environmental concerns. Likewise, water and wastewater utilities’ policies, designed at improving services, boost public health, preserve water, reduce operating costs, and sustain affordability, should be enforced.

We derived from earlier investigations the most significant criteria for prioritizing wastewater sanitation services18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Table 1outlines the key evaluation criteria derived primarily from Jararaa32 and associated with sustainability objectives, taking into consideration local conditions.

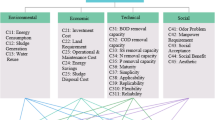

Figure 1 presents the hierarchical structure of the proposed SPI framework. It is structured into three levels, having the primary goal of developing a decision support model for prioritizing sanitation and wastewater treatment services at the top of the hierarchy. The second level presents the key evaluation criteria, coded from EC1 to EC9, that assess the performance of options/alternatives towards the overall goal. All these criteria will be appraised regarding their relevance to the overall goal in the upper level. Lastly, the third level is designated for a group of options representing targeted communities tagged from Community 1 to Community n, which will be scored and categorized following their performance towards every evaluation criterion in the upper level.

Fuzzy set theory

Fuzzy set theory introduced by Zadeh in 1965 36, has been widely applied for modeling decision-making processes associated with incomplete and vague data. It considers the uncertainty embedded in human communication, reasoning, evaluation, and decision-making37. Linguistic attributes can be articulated qualitatively via linguistic expressions and quantitively as a fuzzy set in the entire universe of discourse along with a membership function. Elements in fuzzy set theory are associated with a space that lacks distinct defined bounds. In contrast to crisp sets, where an object simply pertains to or is not associated to a set, fuzzy set theory enables objects to possess membership values spanning the interval [0, 1], that imply a degree of membership36. Triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) are frequently applied for modeling qualitative concepts as fuzzy numbers, because of their straightforward nature and capacity for interaction with linguistic terms38. For a triangular fuzzy number \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{A}\), the membership function, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, transforms from the space (R) to the interval ([0, 1]). It is represented by three values, symbolized as (l, m, u), and can be stated as shown in Eq. 1:

The (l, m, u) attributes indicate real numbers that stand for the lowest, ideal, and the highest possible values, respectively. They express a fuzzy scenario that involves (l < m < u). Considering two triangular fuzzy numbers, \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{A}\) = (a1, a2, a3) and \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{B}\) = (b1, b2, b3), the operational notions outlined as follows:

The symbols \(\:\oplus\:\) and \(\:\otimes\:\) depict an expanded summing and multiplication of the two triangular fuzzy numbers, respectively.

Fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP) technique

The AHP procedure, developed by Saaty39, is one of the most applied MCDA techniques40,41,42, with broad applications across different fields. These include assessment of healthy lifestyles43, solid waste management44, land susceptibility assessments45, identifying ideal locations for solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants46, mapping flood susceptibility47, analyzing earthquake hazards48, and groundwater quality assessment49. This technique is characterized by its well-defined mathematical properties, ease of acquiring the required input data, and capacity to successfully manage both quantitative and qualitative data. It is also reliable for structuring complicated decision problems into multi-level systems50. As indicated by Nassereddine and Eskandari51, AHP is appealing from the experts’ perspective compared to other MCDA techniques.

Even though it is straightforward to comprehend in the overall context of mathematical computations, it gets criticized frequently for failing to cope with uncertainty issues. Therefore, incorporating fuzzy set theory with conventional AHP becomes crucial for managing sources of uncertainty. The fuzzy extension of AHP (FAHP) encodes linguistic decisions into triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) configured in a fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix structure, thus rendering it perfect for tackling hierarchical evaluation problems having fuzzy decision-making requirements52. In the present study, we applied the methodology suggested by Kabir and Sumi53 and Calabrese, et al.54. This methodology draws on the modified normalization method suggested by Wang and Elhag55, which processes evaluations, verifies consistency, and evaluates priority weights, as highlighted below:

Step 1

Transformation of the linguistic concepts applied by DMs for expressing comparison evaluations into TFNs. The comparison matrix is structured as follows.

Table 2shows the value scale applied in the FAHP56.

Step 2

To combine the priorities of tDMs and form the conclusive pairwise comparison matrix, the function of the geometric mean can be applied57.

\(\:L{w}_{ij}\) =\(\:\:(\prod\:_{t=1}^{T}L{w}_{ijt}{)}^{1/t}\), \(\:M{w}_{ij}\) =\(\:\:(\prod\:_{t=1}^{T}M{w}_{ijt}{)}^{1/t}\), \(\:U{w}_{ij}\) =\(\:\:(\prod\:_{t=1}^{T}U{w}_{ijt}{)}^{1/t}\)

\(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{w}}_{ij}\) = the triangular fuzzy weight of the ith criterion relative to the jth criterion.

Step 3

After combining t DMs’ priorities in just one matrix, the mean integration methodology can then be applied to defuzzify the consolidated inputs. This strategy transforms the fuzzy number = (l, m, u) into a crisp value58 as follows.

Step 4

To assess a matrix’s consistency, it is possible to assess the associated consistency index (CI) and the consistency ratio (CR) in the manner below.

where\(\:\:{\lambda\:}_{max}\)\(\:\:is\:\)the primary eigenvalue, and n is the matrix order. The CI is subsequently compared to a randomized consistency index (RI), as depicted in Table 3.

The CR for the same order matrix is given by the following equation:

Generally, CR should be managed at or below 10% for the sake of the matrix’s consistency.

Step 5

Following the consistency assessment, the modified Chang extent analysis methodology, involving the correction for Chang’s normalization algorithm as suggested by Wang, et al.59, can be deployed. The aggregate value of every row in the consolidated matrix is computed applying the subsequent equation.

To normalize the row sum \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{S}}_{i},\) use the following equation:

Step 6

The precise values can be estimated by converting the fuzzy weights applying the strategy suggested by Calabrese, et al.54 as follows.

Normalization provides an equivalent normalized crisp weight vector as follows:

Fuzzy synthetic evaluation technique (FSET)

The FSET forms part of the fuzzy MCDA methodologies, and it induces an aggregated version that synthesizing several distinct components of an exclusive assessment29. As a subfield of fuzzy set theory, FSET enables the effective management of vague non-numerical notions along with handling the inherent uncertainties in knowledge of experts60.

Fuzzification of the evaluation criteria

To apply the FSET for evaluating SPI, the contributing criteria must be fuzzified. This implies developing membership functions for these criteria, that will transform real-world data into fuzzy values in the range of [0, 1]. In the present scenario, membership functions are categorized into three classes: low, medium and high, and are expressed by triangular function. The low level suggests the minor potential contribution to the SPI, the medium level signifies an intermediate contribution, and the highest level offers the most significant contribution to the SPI. The nature and quality of data in the evaluation criteria (i.e. crisp, fuzzy or uncertain data) impacts the fuzzification strategy should be applied29. The ranges of performance levels and corresponding thresholds for the evaluation criteria were identified leveraging pertinent literature18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, interviews and consultations with field experts and professionals, and considering local conditions and overall characteristics of targeted communities.

The demographic criterion (EC1), an essential aspect of social sustainability, is recognized as a key indicator in prioritizing sanitation services, and its significance increases as populations grow. Following consultations with experts and investigating funding agency selection criteria, sanitation programs are typically prioritized for funding in communities with populations surpassing 10,000 61. In the present study, we developed three performance levels based on the population ranges that dominate the Palestinian communities and the suggestions of experts and guidelines of funding agencies: communities with less than 10,000 people are awarded a low score, the ones with 10,000 to 15,000 acquire a medium score, and communities over 15,000 are assigned a high score. For the water consumption criterion (EC2), which is a measure of wastewater production, Jararaa32stated a 5-point scale, with 1 point for consumption less than 45 lcpd, 2 points for 45–55 lcpd, 3 points for 56–65 lcpd, 4 points for 66–90 lcpd, and 5 points for consumption above 90 lcpd. In the present model, this criterion is organized into three performance levels to correspond to the entire methodology, which depends on three distinct levels. The three-level procedure streamlines the evaluation process while retaining accuracy. A low rating is specified for consumption less than 45 lcpd, a medium rating for consumption between 45 and 65 lcpd, and a high rating for consumption above 65 lcpd. The wastewater reuse criterion (EC3), which determines the capacity for using treated wastewater in agriculture, is impacted by considerations including agricultural land availability. This criterion draws on the system of classification applied by Palestine’s Ministry of Agriculture, which classifies land into three distinct groups: low, medium, and high value land. Highly valuable agricultural land holds the greatest potential for exploiting treated wastewater62.

The classification of environmental factor (EC4), which evaluates the hydrological vulnerability of groundwater to pollution triggered by inadequate sanitation practices, follows the guidelines formulated by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the Palestinian Environmental Quality Authority. This system maps Palestinian regions into three categories according to the hydrological vulnerability of groundwater to pollution sources: low, medium, and high63. For the operational body criterion (EC5), which examines utilities’ competence in managing and operating sanitation services, we applied Palestine’s Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) and Municipal Development and Lending Fund (MDLF) classification. This approach scores municipalities from A to D with respect to financial management, maintenance plans, investment, capital budgeting, and auditing64. We assigned performance into three levels: high for A and B municipalities (most competent), medium for C and D municipalities (appropriate competence), and low for village councils and projects committees. The risk of industrial waste (EC6) stands for the adverse effects of industrial effluents on municipal sanitation systems, rendering it less appealing for integrating these businesses into public services due to the requirement of pretreatment. Communities with a higher level of industrial activities are consequently more unlikely to have sanitation services compared to others. We applied the Jararaa32 approach, but three performance levels rather than a five-point scale. The socio-economic factor (EC7) highlights the positive association between a community’s socio-economic standing and its capacity to embrace and sustain sanitary services. We classified performance into three levels: low for communities with less than 30% economically active individuals, medium for those with 30–35%, and high for communities exceeding 35% 32.

The geographical factor (EC8), which impacts sewerage network costs and promotes gravity-based systems, was categorized into three levels of performance following experts’ consultations: low for systems having less than 50% gravity flow, medium 50-95%, and high for systems exceeding 95%. For the last criterion, licenses issues (EC9), which pertains to acquiring licenses and executing projects, we relied on policymakers’ recommendations and guidelines of the Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) to establish performance levels. Communities in geopolitical area A (under full Palestinian rule) enjoy swift approval and implementation. Those in area B (under partial Palestinian authority) possess lower approval rates. While communities in area C (outside of Palestinian authority control) typically endure major delays in acquiring approval. Table 4 presents the fuzzy sets of the evaluation criteria that contribute to the SPI.

As an example, when visualizing the demographic criterion and how it contributes to the SPI, it is suggested that the significance is relatively modest for populations below10000, Table 4. For populations of 10,000 and 15,000, the significance is moderate. Finally, for populations more than 15,000, the significance is major, as the demand for sanitary infrastructures elevates with the growth of populations. The performance scale and membership functions for this criterion are presented in Fig. 3. As an illustration, in a community of 10,500 citizens, the fuzzified three-tuple fuzzy set for this case can be generated via intersecting the criterion value (x-axis) with each of the membership functions. As illustrated in Fig. 3, there is a lack of intersection with the low membership function (i.e., µLow = 0). The measurement gets across with the medium membership function at 0.9 (i.e., µMedium = 0.9) and the high membership function at 0.1 (i.e., µHigh = 0.1). The fuzzy mapping algorithm delivers a fuzzified value of [0.0, 0.9, 1.0].

Following the fuzzification procedure, the resultant three–tuple fuzzy set for each criterion can be expressed by the equation below, as observed in the previous case:

where the three–tuple fuzzy (low, medium, high) for attribute i is expressed by Ai after fuzzification operation.

The interpolation techniques corresponding with the demographic criterion applied for establishing the fuzzy set are listed below as an illustration:

The cumulative contribution of evaluation crietria to the SPI at the community level

The composite performance of the evaluation criteria will conclude in a synthesized SPI value for every community under investigation. This synethesized performance score will possess the arrangement of a three-tuple fuzzy set, as given in Eq. 14. As described by Khatri, et al.29, aggregation is made possible by multiplying the weighted vector of the criteria (i.e., the weights vector acquired by applying the FAHP methodology) with the evaluation matrix. For instance, if there are nj evaluation criteria pertaining to the overall goal Cj, and following fuzzifiying the evaluation criteria, the resultant evaluation matrix is going to be of size [nj*3]. The weights vector for this set of the evaluation criteria, derived from the FAHP methodology, is Wjnj = [wj1………wji….wjnj]. The aggregation function follows the equation described below:

where Ajnj is the evaluation matrix established by the fuzzification of nj evaluation criteria; \(\:\begin{array}{ccc}{[\mu\:}_{1}^{ji}&\:{\mu\:}_{2}^{ji}&\:{\mu\:}_{3}^{ji}]\end{array}\) corresponds to the three-tuple fuzzy array (low, medium, high) for the evaluation criteria i (i = 1 to nj), and Cj signifies the three-tuple fuzzy set \(\:\left[\begin{array}{ccc}{\mu\:}_{1}^{j}&\:{\mu\:}_{2}^{j}&\:{\mu\:}_{3}^{j}\end{array}\right]\) for the SPI/community following aggregation.

Defuzzification of the aggregated SPI

This technique involves transforming the three-tuple fuzzy set, which corresponds to the SPI/community, into a precise number. To achieve this transformation, it is possible to apply an array of techniques (e.g., mean-max-membership operation, centroid method, maximum operator, etc.)65. The centroid technique constitutes one of the most frequently applied techniques for figuring out the center of gravity for a fuzzy set29. The subsequent equations define the procedure:

where CA symbolizes the centroid of the fuzzy set A over an interval d to e.

To define the SPI/community, we specified three distinct levels, and the centroid value for every membership function can be identified in the following procedure:

where SPI/communityi is the defuzzified value of SPI for community i, Bi is the value of the SPI for community i in the structure of a three –tuple fuzzy set, and [C]T is the transpose of the centroid values vector of the recommended membership functions, C = [Clow, CMedium, CHigh]. The membership functions specified in the present study for expressing low, medium, and high SPI were (0, 0, 50), (0, 50, 70), (50, 70, 100), respectively. The associated centroid values are Clow = 16.67, Cmedium = 40.0, and Chigh = 73.3, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

The intention of this analysis is to examine the casual association between the model’s inputs and outputs, recognizing factors that exert a substantial impact on outputs and valuing this impact. In the present study, sensitivity analysis entails exchanging each criterion weight provided by the FAHP for another criterion weight (mutual exchange)66. This strategy optimizes comprehension of how experts and DMs shape key evaluation criteria. Considering evaluation criteria number, multiple combinations will conclude in new scenarios. The preliminary SPI/community scores will be retained as a benchmark and investigated across every scenario, while considering modifications in criteria weights. The root mean square error (RMSE) algorithm will quantify deviations in SPI values/community among the new conditions and the initial setting as stated below:

RMSE = \(\:\sqrt{\frac{\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{\left({X}_{i}-{X}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}\right)}^{2}}{n}}\)(23)

where, Xi = SPI/community in the new scenario developed by the mutual exchange of criteria weights, Xi´= SPI/community value in the initial scenario, and n = the number of scenarios in which criteria weights were mutually exchanged.

Moreover, the Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (R) is applied for assessing the correlation between the ranking of SPI values in the initial condition versus the median SPI values in the sensitivity analysis procedure. The coefficient is typically applied to relate two ordinal attributes and to investigate the association between ranks acquired via various techniques67. It is explained by the following Eq. 68:

where, a = number of communities, A = the overall number of communities, Da = the distinction in the ranks developed by two different techniques. If the coefficient R is 1, it implies a full correlation in the rankings. A zero R suggests that there is no correlation. If Ris -1, it signifies a complete conflict in the ranks resulting from the two assessed techniques69.

Case study

The developed model is applied to assign priority to a particular collection of Palestinian communities having distinct features but a shared lack of sanitation infrastructures, functioning as an experiment for evaluating its robustness. Palestine (West Bank and Gaza) is a water- deprived, lower-middle-income state with a water-intensive culture70. It is potentially vulnerable owing to its geopolitical status, and its water security components are considered marginalized and fragile70. The Palestinian territories endure substantial and intensifying water supply deficits for domestic uses. The World Health Organization (WHO) states 100 L per capita per day (lcpd) as the minimum quantity of water necessary to maintain overall health and hygiene. The PWA, the responsible authority by law for all regulatory, planning, and monitoring of the water and wastewater sectors in Palestine, has established an improved target of 120 lcpd–150 lcpd. In contrast, considering non-revenue water (NRW), the water resources at hand in the West Bank and Gaza deliver just 62 lcpd and 89 lcpd, respectively. By 2030, the West Bank’s domestic water supply gap is projected to be over 92 million m3, while Gaza’s gap is projected to be approximately 79 million m3 70.

Sanitation accessibility in Palestine territories is high, however sewerage connections are considerable better in Gaza compared to the West Bank. Nearly 78% of the population in Gaza enjoys access to sewerage infrastructure, while the remaining depend on on-site services. Regarding the West Bank, 94% enjoy access to improved sanitation, but just 30% have access to sewerage networks. The other two thirds use cesspits that are regularly drained by vacuum tankers, which typically dump waste onto open spaces, bringing up the risks of groundwater pollution71. In the West Bank, nearly 30% (21 million m3) out of the overall 69 million m3of wastewater goes into collection, but only 9.5 million m3is treated. For Gaza, around 1 million m3of wastewater treated gets reused annually out of an overall of 80 million m3produced. Thirteen million meter cubes undergo treatment and are released to the aquifers, while 46 million m3of untreated or semi-treated wastewater ends up flowing into wadis, the ground, and the sea70. In the West Bank, 42 out of the 286 service providers deliver both water and wastewater services, while the others merely offer water. Meanwhile, 20 out of the 25 service providers in Gaza deliver the two water and wastewater services, while the other merely providing water-only services71.

Wastewater treated is recognized as an intriguing solution to fulfilling a portion of the growing water demands. The wastewater system in Palestine is plagued by inadequate sanitation, limited wastewater treatment, improper disposal of untreated or partly treated wastewater, including the use of untreated wastewater for irrigation of edible crops72. Such challenges are further aggravated by an inadequate level of organizational integration, as multiple stakeholders are involved, contributing to institutional fragmentations and incompetence72. Due to the shortage of sufficient financial resources, funding agencies engage in a significant role in the development of Palestine’s sanitation sector73. Such services are impacted by the selective allocation of funds to certain categories of infrastructure, driven by donor’s views74. Donors frequently prioritize funding for major infrastructure projects, primarily wastewater treatment plants, disregarding the recognition that significant infrastructure spanning the sanitation value chain is insufficient. Stakeholders’ motivation to fund sanitation services are impacted by prevailing social standards, governmental procedures, and associated benefits and costs for each stakeholder73,75. However, this strategy neglects plans for long-term development that promote sustainability74. In conclusion, resources and funds must be strategically allocated in a manner that prioritizes communities most in need while offering sanitation services. The planned services should be guided by participatory approaches that consider all stakeholder’s interests while adhering to sustainable practices.

The convoluted nature of this decision-making activity, marked by conflicting concerns, mandates the inclusion of primary sector stakeholders for the sake of harmonizing their perspectives. In this context, the primary criteria for the selection of experts were: (1) experience and responsibility that considers the direct involvement of experts in governing and managing the sanitation sector in Palestine, involving their responsibilities in setting guidelines and regulations, identifying priorities, securing funding, and allocating resources; (2) research, communicating and coordinating potentials, making sure that experts are actively engaged in research, developing studies, and collaborating with governmental and international organizations for the advancement of the sanitation sector in Palestine; (3) service provision responsibility that offers practical and real-world insights into the operational components of sanitation services; and (4) inclusivity to ensure that all key actors, including governmental entities, non-governmental agencies, and service providers, are adequately represented, to accommodate diverse perspectives and concerns in the sustainable development of sanitation services in Palestine.

The MCDA procedure is scheduled to reconcile the different perspectives concerning the decision-making problem. It is proposed that five groups of DMs and experts, with advanced knowledge of the problem in question and meeting the previously suggested selection criteria, take part in this project. They have been advised to appraise the whole framework of the decision-making problem with the intention of designing a robust and efficient model for prioritizing sanitation services in Palestine.

Group 1–Decision maker 1 (DM1)

Directors of the PWA express their policymaking responsibilities. This governmental body is exclusively responsible for regulating and supervising Palestine’s water and wastewater sectors. Experts of this group received nominations from the General Directorate for Planning, the General Directorate for Research and Laboratory, and the Wastewater Section at the PWA76.

Group 2–Decision maker 2 (DM2)

This group involves experts from the Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem (ARIJ), a non-profit organization devoted to sustainable development. ARIJ advances national scientific and technical knowledge, introducing efficient resource use and conservation strategies77.

Group 3–Decision maker 3 (DM3)

Environmental organizations, headed by the Palestinian Hydrology Group (PHG), a major Palestinian non-governmental organization, strive to boost water and sanitation access and monitoring climate change and pollution in Palestine78.

Group 4–Decision Maker 4 (DM4): This group involves experts from the Water and Wastewater Sanitation Department in Nablus city, Palestine, representing the service providers. This department delivers and manages two fundamental services: water supply and sanitation. It serves over 160,000 citizens and is staffed by a team of 289 employees79.

Group 5–Decision maker 5 (DM5)

This group involves experts from Wadi Ziemar Joint Service Council for Sanitation Service, one of the largest service providers in the West Bank. The council oversees major wastewater projects in the northern West Bank of Palestine.

The model is tested over 25 Palestinian communities based primarily in the West Bank for easy of obtaining the required field data, Table 5. The base data was extracted primarily from Jararaa32. Some data on population size, water consumption, environmental factors, operation body, and geopolitical status were verified utilizing data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), the Performance Monitoring Report for Water and Wastewater Service Providers in Palestine 2022, the Municipal Development and Lending Fund (MDLF), and the Geomolg portal for spatial information in Palestine62,71,80,81.

Results and discussion

Priority weights of evaluation criteria based on FAHP in group decision making

The FAHP methodology, which is applied to estimate the priority scores of the evaluation criteria that contributed to the SPI, affords guidelines for harmonizing the preferences of multiple DMs on the decision problem undergoing assessment. The entire procedure proceeds by developing a pairwise comparison matrix at the evaluation criteria level. The trade-offs over the evaluation criteria, Level 2-Fig. 1, were mapped in the context of the overall goal, applying the linguistic expressions (Tabel A1, Appendix 1). This technical session was supported by experts from every one of the five DMs groups. The trade-offs of DMs have been mapped into TFNs and their reciprocals (Table A2, Appendix 1). These preferences were then aggregated for group decision-making applying the geometric mean, Table 6.

The outcomes of deriving the priority weights of valuation criteria following aggregating DMs’ preferences to arrive at a group consensus on the relative significance of decision-making problem components towards the SPI, including the conclusions of the consistency test are displayed in Table 7.

In the context of the overall significance of evaluation criteria, Table 7highlights that the demographic criterion (EC1) has the most impact on the SPI, with an overall weight of 20.38%. The water consumption-wastewater production criterion (EC2) follows in second with a priority weight of 16.76%, followed by the likelihood for wastewater reuse (EC3), which is assigned a priority weight of 15.40%. Environmental factors and risks associated with pollution (EC4) having a priority weight of 12.84%, while utilities’ competence to manage sanitation services (EC5) possesses a priority weight of 11.50%. Industrial wastes risk (EC6) is prioritized at 8.72%. The socio-economic context (EC7), geographical-related constraints (EC8), and license constraints (EC9) were each assigned less consideration, with marginal ratings of 5.10%, 4.51%, and 4.8%, respectively. The CR for the comparison matrix of evaluation criteria shows a value slightly over the 10.0% threshold, at 11.2%. In practice, whenever experts assess the decision-making problem with confidence, adopting a matrix with a CR value higher than 10.0% is legitimate82,83,84.

Application of FSET to derive the SPI values for a group of communities

The deployment of FSET requires transforming field data for every scrutinized community into its corresponding fuzzy set. The outcomes are subsequently multiplied by the evaluation criteria weights matrix. It is followed by defuzzification the resulted SPI/community. Figure 4 demonstrates a practical application of the developed model, displaying the development of the SPI for a particular community from a set of researched communities. Figure 5 illustrates the SPI values for all 25 evaluated communities. Out of the 25 communities researched, five achieved SPI values surpassing 60%. Eleven communities had SPI values between 50% and 60%, while 9 recorded SPI values between 40% and 50%.

Application of sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis outcomes, Fig. 6, exhibit 36 conditions of mutual exchange over evaluation criteria, aside from the initial condition, at every community level (Table A3, Appendix 1). When analyzing the rankings of communities relying on the pertaining SPI values in the initial condition to the rankings following the sensitivity analysis (based on SPI median values), 16 of the 25 being investigated communities sustained their rankings. These communities are Community # 7 -Qabatiya, Community # 1 - Silat Al-Harithia, Community # 4 - Deir Abu Da’if, Community # 2 - Al Yamun, Community # 11 -Jaba’, Community # 10 -Meithalun, Community # 22 -Aqraba, Community # 3 - Kafr Dan, Community # 15 -Der Al Ghusun, Community # 25 -Al Dhahiryia, Community # 14 -Qaffin, Community # 9 -Kafr Ra’I, Community # 24 -Yatta, Community # 16 -Bal’a, Community # 18 -Awarta, and Community # 19 -Huwarra. However, 9 communities failed to maintain their rankings in the sensitivity analysis as in the initial condition, including Community # 12 -El Far’a Camp, Community # 17 -Asira Al-Shamaliya, Community # 8 -Arraba, Community # 21 -Jammain, Community # 6 -Ya’bad, Community # 5 -Birqin, Community # 23 -Qabalan, Community # 20 -Beita, and Community # 13 -Tammun. Despite these adjustments, communities exhibited ranking alterations in the sensitivity analysis maintained in the same category, implying only slight changes in their SPI values. The simple fact that communities exhibiting the highest and lowest SPI values in the initial condition sustained their ranks following the sensitivity analysis highlights the robustness of the findings.

The RMSE computations, displayed in Fig. 7, affirmed the findings of the sensitivity analysis. The RMSE values were extremely minimal, spanning from 0.014 in Community # 10 -Meithalun to 0.25 in Community # 13 -Tammun. The Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient (R) computations reveal a near-perfect correlation between SPI values in initial condition and those via the sensitivity analysis application, with R = 0.991 (Table A4, Appendix 1).

Model’s applicability and ethical implications

The model’s adaptability to both developed and developing regions can be achieved with several considerations. While the core framework of the developed model remains applicable, some adjustments may be necessary to account for differences in socio-economic standing, governance systems, licensing concerns, and environmental issues across regions. In developed regions, the model may require less emphasis on dependence on external support and a more focus on technological innovations and infrastructure advancements. Conversely, for developing regions, the model should keep emphasis on resource constraints; however, adjustments in data collection strategies may be necessary, specifically regarding the quality and availability of socio-economic and environmental data. Although the model is built on rigorous criteria aimed at optimizing sanitation services and proving inclusivity, transparency, and robustness by considering an array of socio-economic, technical, and environmental aspects, we acknowledge that regions that are not prioritized for swift sanitation developments may feel marginalized, possibly impacting inclusion and social equity. To tackle this challenge, decentralized wastewater treatment options for low-priority or remote settings are necessary to guarantee that no community is completely excluded from acquiring essential services. Likewise, we advocate revising the prioritization methodology frequently in response to alterations in community needs, environmental surroundings, and socio-economic alterations, thereby ensuring ultimate equity. In doing so, the developed model can be deployed as a component of an adaptable management strategy advancing equitable and sustainable service allocation.

Conclusions

This study presents a two-stage model utilizing FAHP and FSET to support decision-making in identifying and prioritizing communities in need of sanitation services under conditions of uncertainty. The FAHP technique weighs an array of evaluation criteria, considering the local conditions and preferences of different stakeholders. The FSET handles data sets associated with evaluation criteria at the community level, transforming the data and FAHP weights into an index designated as SPI, ranging from 0 to 100%. This index serves to classify and rank communities relative to their critical need for sanitation services. It was successful in broadening the scope of the decision-making problem beyond the economic domain by incorporating overall sustainability dimensions. This methodology’s potential is demonstrated by its capacity to account for distinct stakeholder groups’ concerns and preferences. It can incorporate human and subjective assessments of multiple components of the decision-making problem. Stakeholder engagement was considered in two stages. First, figure out the components and evaluation criteria for the decision-making problem structure during the formulation phase. Second, stakeholders were tasked with deciding on the relevance and significance of evaluation criteria. The proposed model’s applicability was examined in a set of distinct communities in a developing country, all of which lacked sanitation services. The predictions of the model were reliable, with the conventional and sensitivity analysis procedures coinciding almost completely on the stability of ordering the investigated communities according to the associated SPI values.

Introducing more expert insights could significantly boost the model’s reliability. Likewise, incorporating other factors, including cost considerations, will likely improve performance. A further area of interest is the level of membership functions. Expanding the categories of these functions (e.g., very low, low, medium, high, and very high) can boost the model’s potential to recognize distinct communities in a more precise and comprehensive setting.

In conclusion, the developed model holds the potential to support governmental and planning bodies in identifying and prioritizing localities in need of sanitation facilities on a national level in a more accountable and transparent manner while simultaneously considering technical, social, economic, and environmental constraints. The implications of introducing the present model into responsible authorities’ strategic plans embrace a better comprehension of sanitation sector demands, the advancement of well-structured and reliable databases, and the fostering of group decision-making for participatory and intelligent decisions in the wider context of water and wastewater management. Moreover, the model stimulated integrated water resources management (IWRM) strategies with coordinated institutional partnerships. The developed model can be relevant to other international scenarios displaying similar characteristics.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pereira, M. A. & Marques, R. C. Sustainable water and sanitation for all: are we there yet? Water Res. 207, 117765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.117765 (2021).

Castro, J. E. & Heller, L. Water and Sanitation Services: Public Policy and Management (Routledge, 2012).

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. https:// (2024). unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/(accessed June 6, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/ (2020).

Nature Editorial. The water crisis is worsening. Researchers must tackle it together. Nature 613, 611–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00182-2 (2023).

Jaitly, A. Governance of water: institutional alternatives and political economy. J. Resour. Energy Dev. 5, 105–107 (2008).

Cetrulo, T. B., Marques, R. C. & Malheiros, T. F. An analytical review of the efficiency of water and sanitation utilities in developing countries. Water Res. 161, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.044 (2019).

Schmitt, R. J. P., Morgenroth, E. & Larsen, T. A. Robust planning of sanitation services in urban informal settlements: an analytical framework. Water Res. 110, 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.007 (2017).

Muzioreva, H., Gumbo, T., Kavishe, N., Moyo, T. & Musonda, I. Decentralized wastewater system practices in developing countries: a systematic review. Utilities Policy. 79, 101442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2022.101442 (2022).

Lohman, H. A. C. et al. DMsan: a Multi-criteria decision analysis Framework and Package to Characterize Contextualized sustainability of Sanitation and Resource Recovery technologies. ACS Environ. Au. 3, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenvironau.2c00067 (2023).

Huang, J., Li, D., Coulon, F. & Yang, X. J. More work is needed to take on the rural wastewater challenge. Nature 628, 721. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01186-2 (2024).

Jones, E. R. et al. Current wastewater treatment targets are insufficient to protect surface water quality. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00554-y (2022).

Afolabi, O. O. D. & Sohail, M. Microwaving human faecal sludge as a viable sanitation technology option for treatment and value recovery - A critical review. J. Environ. Manage. 187, 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.10.067 (2017).

Jenkins, M. W., Cumming, O. & Cairncross, S. Pit latrine emptying behavior and demand for sanitation services in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 12, 2588–2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120302588 (2015).

Thaher, R. A., Mahmoud, N., Al-Khatib, I. A. & Hung, Y. T. Cesspits as Onsite Sanitation Facilities in the non-sewered Palestinian rural areas: users’ satisfaction, needs and perception. Water 14, 849 (2022).

Alldred, F. C., Gröcke, D. R., Leung, C. Y., Wright, L. P. & Banfield, N. Diffuse and concentrated nitrogen sewage pollution in island environments with differing treatment systems. Sci. Rep. 13, 4838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32105-6 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. Nitrate contamination in drinking water and adverse reproductive and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27345-x (2023).

Howarth, R. et al. Coupled biogeochemical cycles: eutrophication and hypoxia in temperate estuaries and coastal marine ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 18–26 (2011).

Matos, R. V. et al. Multi-criteria Framework for selection of City-Wide Sanitation Solutions in Coastal Towns in Northern Angola. Sustainability 13, 5627 (2021).

Cegan, J. C., Filion, A. M., Keisler, J. M. & Linkov, I. Trends and applications of multi-criteria decision analysis in environmental sciences: literature review. Environ. Syst. Decisions. 37, 123–133 (2017).

Sofiane, B., Dounia, M., Sabri, D., Tarek, K. & Yassine, D. Utilizing a combined Delphi-FAHP-TOPSIS technique to assess the effectiveness of the water supply service in Algeria. Socio-Economic Plann. Sci. 90, 101736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101736 (2023).

Kabir, G., Sadiq, R. & Tesfamariam, S. A review of multi-criteria decision-making methods for infrastructure management. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 10, 1176–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15732479.2013.795978 (2014).

Ezbakhe, F. & Perez-Foguet, A. Multi-criteria decision analysis under uncertainty: two approaches to Incorporating Data uncertainty into Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Planning. Water Resour. Manage. 32, 5169–5182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-018-2152-9 (2018).

Mutikanga, H. E., Sharma, S. K. & Vairavamoorthy, K. Multi-criteria decision analysis: a Strategic Planning Tool for Water loss management. Water Resour. Manage. 25, 3947–3969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-011-9896-9 (2011).

Zyoud, S. H. & Fuchs-Hanusch, D. Comparison of several decision-making techniques: a case of water losses management in developing countries. Int. J. Inform. Technol. Decis. Mak. 18, 1551–1578. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0219622019500275 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of three categories of multi-criteria decision-making methods. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 121824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121824 (2024).

Istiqomah, D. A. & Windarni, V. A. in 4th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE). 67–72. (2019).

Kabir, G. & Hasin, M. A. A. Comparative analysis of AHP and fuzzy AHP models for multicriteria inventory classification. Int. J. Fuzzy Log. Syst. 1, 1–16 (2011).

Kabir, G., Tesfamariam, S., Francisque, A. & Sadiq, R. Evaluating risk of water mains failure using a bayesian belief network model. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 240, 220–234 (2015).

Khatri, K. B., Vairavamoorthy, K. & Akinyemi, E. Framework for Computing a performance index for urban infrastructure systems using a fuzzy Set Approach. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 17, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000062 (2012).

Marcelo, D., Mandri-Perrott, C., House, S. & Schwartz, J. Prioritizing infrastructure investment: a framework for government decision making. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (2016).

Ibrahim, S. & Ali, A. S. Sustainable wastewater management planning using multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) a case study from Khartoum, Sudan. Int. J. Eng. Res. 5 (2016).

Jararaa, B. Y. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Identify the Setting Priorities of the Sanitation Sector in the West Bank (An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine, 2013).

Mahmoud, N., Zimmo, O., Zeeman, G., Lettinga, G. & Gijzen, H. Perspectives for integrated sewage management in Palestine and the Middle East. Water 21, 24–26 (2004).

Palestinian Water Authority. National water and wastewater policy and strategy for Palestine: Toward building a Palestinian state from water perspective. (2013).

Al-Sa’ed R. (2000).

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control. 8, 338–353 (1965).

Zimmermann, H. J. Fuzzy set theory. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Stat. 2, 317–332 (2010).

Li, G., Kou, G., Lin, C., Xu, L. & Liao, Y. Multi-attribute decision making with generalized fuzzy numbers. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 66, 1793–1803. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.1 (2015).

Saaty, T. L. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP). J. Oper. Res. Soc. 41, 1073–1076 (1980).

Zyoud, S. H. & Fuchs-Hanusch, D. A bibliometric-based survey on AHP and TOPSIS techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 78, 158–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2017.02.016 (2017).

Kriswardhana, W., Toaza, B., Esztergár-Kiss, D. & Duleba, S. Analytic hierarchy process in transportation decision-making: a two-staged review on the themes and trends of two decades. Expert Syst. Appl. 261, 125491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125491 (2025).

Varshney, T. et al. Fuzzy analytic hierarchy process based generation management for interconnected power system. Sci. Rep. 14, 11446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61524-2 (2024).

Min, Z. et al. Developing an assessment tool for the healthy lifestyles of the occupational population in China: a modified Delphi-analytic hierarchy process study. Sci. Rep. 14, 20359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71324-3 (2024).

Parekh, H., Yadav, K., Yadav, S. & Shah, N. Identification and assigning weight of indicator influencing performance of municipal solid waste management using AHP. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 19, 36–45 (2015).

Myronidis, D., Papageorgiou, C. & Theophanous, S. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on landslide history and analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Nat. Hazards. 81, 245–263 (2016).

Günen, M. A. Determination of the suitable sites for constructing solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants in Kayseri, Turkey using GIS-based ranking and AHP methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 57232–57247 (2021).

Hammami, S. et al. Application of the GIS based multi-criteria decision analysis and analytical hierarchy process (AHP) in the flood susceptibility mapping (Tunisia). Arab. J. Geosci. 12, 1–16 (2019).

Nyimbili, P. H., Erden, T. & Karaman, H. Integration of GIS, AHP and TOPSIS for earthquake hazard analysis. Nat. Hazards. 92, 1523–1546 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Groundwater quality evaluation and analysis technology based on AHP-EWM-GRA and its application. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234, 19 (2023).

Zyoud, S. H. et al. Utilizing analytic hierarchy process (AHP) for decision making in water loss management of intermittent water supply systems. J. Water Sanitation Hygiene Dev. 6, 534–546. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2016.123 (2016).

Nassereddine, M. & Eskandari, H. An integrated MCDM approach to evaluate public transportation systems in Tehran. Transp. Res. Part. A: Policy Pract. 106, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.10.013 (2017).

Zyoud, S. H., Kaufmann, L. G., Shaheen, H., Samhan, S. & Fuchs-Hanusch, D. A framework for water loss management in developing countries under fuzzy environment: integration of fuzzy AHP with Fuzzy TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 61, 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2016.05.016 (2016).

Kabir, G. & Sumi, R. S. Power substation location selection using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and PROMETHEE: a case study from Bangladesh. Energy 72, 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.05.098 (2014).

Calabrese, A., Costa, R. & Menichini, T. Using fuzzy AHP to manage Intellectual Capital assets: an application to the ICT service industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 40, 3747–3755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.12.081 (2013).

Wang, Y. M. & Elhag, T. M. S. On the normalization of interval and fuzzy weights. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 157, 2456–2471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2006.06.008 (2006).

Khazaeni, G., Khanzadi, M. & Afshar, A. Fuzzy adaptive decision making model for selection balanced risk allocation. Int. J. Project Manage. 30, 511–522 (2012).

Jaiswal, R., Ghosh, N. C., Lohani, A. & Thomas, T. Fuzzy AHP based Multi Crteria decision support for Watershed prioritization. Water Resour. Manage. 29, 4205–4227 (2015).

Kutlu, A. C. & Ekmekçioǧlu, M. Fuzzy failure modes and effects analysis by using fuzzy TOPSIS-based fuzzy AHP. Expert Syst. Appl. 39, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2011.06.044 (2012).

Wang, Y. M., Luo, Y. & Hua, Z. On the extent analysis method for fuzzy AHP and its applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 186, 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2007.01.050 (2008).

Sadiq, R. & Rodriguez, M. Fuzzy synthetic evaluation of disinfection by-products - a risk-based indexing system. J. Environ. Manage. 73, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.04.014 (2004).

Palestinan Water Authority. National Water Policy for Palestine. Final Draft Water Policy (2013–2032), (2013). https://www.pwa.ps/userfiles/server/policy/Policy%20-%20English%20-%20Final.pdf

Geomolg Geomolg portal for spatial information in Palestine. https:// (2024). geomolg.ps/L5/index.html?viewer=A3.V1 (accessed March 10, https://geomolg.ps/L5/index.html?viewer=A3.V1 (2024).

United Nations. Desk study on the environment in the occupied Palestinian territories: note / by the Executive Director, (2003). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/514648?ln=en&v=pdf

MDLF. Municipal Development & Lending Fund-Local Beneficiary (2024). https://www.mdlf.org.ps/en/Home/Index

Lu, R. S., Lo, S. L. & Hu, J. Y. Analysis of reservoir water quality using fuzzy synthetic evaluation. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 13, 327–336 (1999).

Gumus, A. T. Evaluation of hazardous waste transportation firms by using a two step fuzzy-AHP and TOPSIS methodology. Expert Syst. Appl. 36, 4067–4074 (2009).

Li, W., Humphreys, P. K., Yeung, A. C. L. & Cheng, T. C. E. The impact of supplier development on buyer competitive advantage: a path analytic model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 135, 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.06.019 (2012).

Chitsaz, N. & Banihabib, M. E. Comparison of different Multi Criteria decision-making models in prioritizing Flood Management Alternatives. Water Resour. Manage. 29, 2503–2525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-015-0954-6 (2015).

Govindan, K., Diabat, A. & Madan Shankar, K. Analyzing the drivers of green manufacturing with fuzzy approach. J. Clean. Prod. 96, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.054 (2015).

World Bank Group. Securing Water for Development in West Bank and Gaza: Sector Note (World Bank, 2018).

Water Sector Regulatory Council. Performance Monitoring Report For Water & Wastewater Service Providers in Palestine 2022, Palestine. (2023). https://www.wsrc.ps/public/uploads/Publication/1703588627781695.pdf

Samhan, S. et al. Springer Berlin Heidelberg,. in Waste Water Treatment and Reuse in the Mediterranean Region (eds Damià Barceló & Mira Petrovic) 229–248 (2011).

Zaqout, M., Fayad, M., Barrington, D. J., Mdee, A. & Evans, B. E. Sanitation is political: understanding stakeholders’ incentives in funding sanitation for the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Third World Q. 45, 1437–1457. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2024.2318476 (2024).

Qarmout, T. Delivering Aid without Government. (2017).

Ostrom, E., Schroeder, L. & Wynne, S. Institutional incentives and sustainable development: Infrastructure policies in perspective. Edited by P. A. Sabatier, 1st ed., 2–25. Boulder: Westview Press., (1993).

Palestinain Water Authroity. About PWA. https:// (2024). www.pwa.ps/page.aspx?id=5W6F7La2541180510a5W6F7L (accessed April 5, https://www.pwa.ps/page.aspx?id=5W6F7La2541180510a5W6F7L> (2017).

The Applied Research Institute. Vission & Mission. (2024). https://www.arij.org/vision-mission/(accessed April 5, https://www.arij.org/vision-mission/ (2024).

The Palestinain Hydrology Group. Palestinain Hydrology Group for Water & Environmental Resources Development. (2024). https://www.phg.org/sections/view/2(accessed April 5, https://www.phg.org/sections/view/2 (2024).

Nablus Municipality. Water and Wastewater Department, (2016). -09-21-06-44-57> https://nablus.org/index.php/ar/2016-03-31-13-59-20/ (2024).

The Municipal Development and Lending Fund. MDLF Annual/Semi Annual Reports. (2024). https://mdlf.org.ps/en/cmspage/AllProjects(accessed April 5, https://mdlf.org.ps/en/cmspage/AllProjects (2024).

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Poulation Projections. (2024). https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/lang__en/803/default.aspx(accessed March 1, https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/lang__en/803/default.aspx (2024).

Pant, S., Kumar, A., Ram, M., Klochkov, Y. & Sharma, H. K. Consistency indices in Analytic Hierarchy process: a review. Mathematics 10, 1206 (2022).

Lee, S. Determination of Priority weights under Multiattribute decision-making situations: AHP versus fuzzy AHP. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 141, 05014015. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000897 (2015).

Dhurkari, R. K. Remarks on the inconsistency measure of the Analytic Hierarchy process. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 43, 4669–4679. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-212041 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Subhi Samhan, General Director for Research and Laboratory, Palestinian Water Authority; Ms. Suhad Al Malki, Director for Research Department, Palestinian Water Authority; Eng. Hala Barhomi, General Director for Planning, Palestinian Water Authority; Eng. Omar Abu Awwad, Head Section for Wastewater, Palestinian Water Authority; Dr. Jad Isaac, Director General, Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem; Eng. Sami Dawoud Hamdan, Director, Palestinian Hydrology Group-North Branch; Eng. Yahya Saleh, Chief Executive Officer, Wadi Ziemar Joint Service Council-Tulkarm; Eng. Ali Abuzant, Division Head of Wastewater and Rain Drainage Networks Maintenance, Nablus Municipality; and Eng. Firas Al-Wadi, Water and Sanitation Department, Nablus Municipality. The authors would also like to thank Palestine Technical University (Kadoorie) for all administrative assistance during the project’s implementation.

Funding

NA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH.Z., S.O., and S.J. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, study design, software development, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, and visualization. SH.Z. supervised the project and performed the final review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This analysis is without human involvement. There was no need for ethical approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zyoud, S., Omair, S.M. & Jarrad, S.A. A two-stage model of the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and the fuzzy synthetic evaluation technique to prioritize sustainable sanitation services under uncertainty. Sci Rep 15, 3736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88236-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88236-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

From Nature for Nature: Chitosan-based Materials for Clean Water by Flocculation – Mini Review

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)

-

The combination of PROMETHEE II and FAHP methods for prioritizing maintenance work in a sanitation network

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)