Abstract

This study investigated the time-varying effects of vaccines and oral antiviral drugs in preventing severe COVID-19 complications and mortality in Hong Kong. Utilizing data from hospitalized patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 between March 15, 2022, and November 30, 2022, the study employed the Andersen-Gill model with time-dependent explanatory variables to address immortal time bias. Results demonstrate that both vaccines and oral antivirals offered time-dependent protection, with vaccines showing significant waning effects after the fourth dose. Oral antivirals were most effective if administered within five days of diagnosis. Understanding these temporal effects is crucial for optimizing intervention strategies and improving clinical outcomes. The study also underscores the importance of considering pharmacodynamics and vaccination schedules in combating COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has posed unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems globally. As of February 20th, 2024, there have been over 774 million reported COVID-19 cases and an estimated 7 million recorded deaths worldwide. However, the actual numbers of infections and fatalities are likely to be much higher than the official figures1,2,3. In Hong Kong, the pandemic has been characterized by six distinct waves of infection. Hong Kong experienced relatively low SARS-CoV-2 circulation until a major community outbreak of the Omicron (B.1.1.529) sublineage BA.2.2 began in January 2022, triggering the fifth wave. Subsequently, the more transmissible BA.4/5 variant emerged in June 2022 and became the predominant strain by August 2022, resulting in the sixth wave of the pandemic4,5,6. From December 31, 2021, to January 1, 2023, the fifth and sixth waves had resulted in a reported 2,863,475 confirmed COVID-19 cases. This evolving public health challenge has spurred the rapid development of vaccines and the repurposing of existing medications to treat COVID-19 infections. Oral antiviral agents have emerged as crucial tools in reducing the incidence of severe complication, slowing down disease progression, and decreasing mortality rates in hospitalized patients7.

Oral antivirals (OAVs), such as molnupiravir (Lagevrio) and nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir (Paxlovid), have gained emergency use authorization from the US Food and Drug Administration for treating non-hospitalized, mild-to-moderate COVID-19 adult patients at risk of progressing to severe disease. These OAVs have been extensively studied in randomized controlled trials and real-world studies, consistently demonstrating their effectiveness in reducing hospitalizations and mortality rates. Their approval provides a novel and promising treatment option for adult patients with COVID-198,9,10,11,12,13. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir was delivered to Hong Kong on March 14, 2022, while molnupiravir arrived in Hong Kong a few days earlier. The Hospital Authority began distributing these antiviral drugs to hospitals on the day after their arrivals14,15,16. Doctors will assess and make clinical judgments based on each patient’s condition before prescribing the appropriate oral antiviral drugs, aiming to reduce the risk of deterioration and minimize the likelihood of adverse reactions following treatment.

Apart from oral antivirals, vaccination plays a crucial role in combating the ongoing global pandemic. In Hong Kong, the COVID-19 Vaccination Programme was launched on February 23, 2021. Two types of vaccines were used in Hong Kong, namely, Comirnaty (BNT162b2), an mRNA-based vaccine, and CoronaVac (Sinovac), an inactivated virus vaccine. The Comirnaty vaccine has been found to lower the hospitalization rate and reduce the frequency of severe outcomes due to the COVID-19 virus17,18,19,20. Both vaccines have shown to be effective in reducing the chance of developing severe diseases21,22..

Although vaccines and antiviral drugs have been used to reduce numbers of infections, complications and deaths, the virus has exhibited rapid evolution into new variants and subvariants. Decline in vaccine protection has been observed in various scenarios, especially against infection23. Observational evidence suggests that vaccines offer robust and long-lasting protection against severe complication and death24,25,26,27. Some studies have focused on examining the combined impact of vaccines and antiviral drugs, but they have not taken into account the time-varying effect of these interventions28,29,30. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the time-varying effect of vaccines and antiviral drugs in preventing severe complications and death.

Methods

Study design and study population

In this territory-wide study, we utilized electronic medical records from the Clinical Management System of Hong Kong Hospital Authority, vaccination records (including vaccination types and dates) from the Hong Kong Department of Health, and COVID-19 confirmed case records from the Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection. The datasets were match-merged using unique pseudo identifiers. The electronic medical records contained important variables such as age, gender, history of hospital admission, chronic diseases, and other relevant information. By combining and analyzing these datasets, we aimed to gain comprehensive insights into the relationship between vaccination status, medical history, and COVID-19 outcomes in Hong Kong. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The need to obtain informed consent for this retrospective study was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB) (Reference No.: UW 20–341 and date of approval: 17/2/2022).

Outcomes and follow-up period

The main objective of this study was to examine the time-varying protective efficacy (PE) of vaccines and antiviral drugs on complications or death among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Complications were defined as the progression of the disease into a serious, critical, or fatal case. This definition is based on a combination of factors, including mortality, the need for oxygen supplementation at a rate of \(\ge\)3 L per minute, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation, the requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or experiencing shock29. Our study population comprised of patients who were admitted to the hospital between March 15, 2022, and November 30, 2022, and had a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This timeframe aligns with the introduction of antiviral drugs in Hong Kong21,22. Notably, we did not take into account the administration of antivirals prior to hospitalization. It is important to note that we assumed individuals would not progress to severe cases or death within two weeks of their last vaccination. The follow-up period for each hospitalized patient in the study began on the date of confirmed diagnosis or two weeks after receiving vaccination, and it continued until the time to occurrence of the primary outcome of interest, discharge from hospital or end of the observation period.

Explanatory variables

The risk set was organized and analyzed based on calendar days, which helped to address the concern of immortal time bias. We also took into account the changes over time in key variables, such as the status of oral antiviral treatment and the duration since the last vaccination. Specifically, if an oral antiviral was prescribed, we further distinguished whether the prescription was given within 5 days of confirmed diagnosis or not. Regarding vaccination, we included one-dose, two-dose, three-dose, and four-dose regimens as exposures of interest. We also examined different vaccine types, specifically Comirnaty and CoronaVac. Alongside these variables, we included other predictors in our analysis, namely age, gender and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

Statistical analysis

We adopt the Andersen-Gill model, which is an extension of the Cox model for analysis of recurrent events29,30,31,32. Let day 1 be March 15, 2022, and so on. The hazard function of the outcome event for subject \(i\) on day \(t\) then takes the form

where \({\lambda }_{0}(t)\ge 0\) is an unspecified baseline hazard function, \({{\varvec{x}}}_{i}\left(t\right)\) is a vector of covariates that includes age, gender, CCI with the corresponding vector of regression coefficients \(\boldsymbol{\alpha }\), \({z}_{i}(t)\) is the vaccination status with \({z}_{i}\left(t\right)=0\) if the subject had not received any vaccination before day \(t\) and \({z}_{i}\left(t\right)=1\) otherwise, \({V}_{i}\left(t\right)\) is the function of the time-varying vaccination effect which is expected to wane over time, \({w}_{i}(t)\) is the oral antiviral prescription status with \({w}_{i}(t)=0\) if the subject had not been prescribed an antiviral drug on or before day \(t\) and \({w}_{i}(t)=1\) otherwise, \({O}_{i}\left(t\right)\) characterizes the time-varying effect of the OVA which is further elaborated below.

Let \(d\) be the day of receiving the last vaccination. The time-varying vaccination effect \(V(t)\) is estimated separately for different number of doses received on day t using a modified exponential decay function32 given by

where \(\left(t-d-14\right)\)is based on the assumption that it takes 14 days for the protective effects of the vaccination to reach its peak33,34. This function has the advantage that the three parameters A, B and C, are interpretable, representing the dose effect immediately after each vaccination, the rate of waning and shape of trajectory, respectively.

Since we do not have the exact or approximate time required for the antiviral drugs to take effect, we use the 4-parameter pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) function to estimate the trajectory of the efficacy. Not only does this approach provide biomedical interpretation, but it also enables a non-monotonic, non-linear estimation of the time-varying effects and the estimation of the peak level of PE35. Let \(p\) be the day of receiving the antiviral drug treatment. The time-varying antiviral drug effect on day \(t\) using a PK/PD function can be expressed as:

A large \(\beta\) value indicates a lower level of protection, a large \(\kappa\) value indicates a quicker rise of \(\frac{\kappa }{\kappa -1}\left({e}^{-(t-p)}-{e}^{-\kappa (t-p)}\right)\) and therefore \(O\left(t\right)\), and a large \(\upgamma\) value indicates a more sigmoid shape of the trajectory. A large \(\delta\) value with a negative sign indicates a robust, long-lasting protective effect over time, while a large positive \(\delta\) value indicates a strong rebound effect.

The PE of vaccine can be expressed as

and that of the oral antiviral drug as

The estimates for the parameters are obtained by maximizing the Breslow-type partial likelihood function.

Results

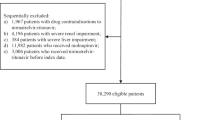

We identified a total of 48,984 hospitalized patients with confirmed diagnoses of SARS-CoV-2 infections between March 15, 2022, and November 30, 2022. Among these patients, 38,290 individuals met the inclusion criteria, of which 9,512 and 10,851 received molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, respectively (Fig. 1).

Among the 20,363 patients who received oral antiviral treatments, 8,608 were 80 years or above, 8,972 between 60 and 79, and 2,783 below 60 and above 18 (Supplementary Table 1). In this study, 9,661 patients had not taken any vaccination. 549, 2,712, 5,044, and 407 patients received one, two, three, and four doses of Comirnaty, respectively, and 3,358, 6,531, 9,033, and 968 patients, respectively for CoronaVac. The daily numbers of severe complication cases and death cases are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

We categorize the patients into three age groups, namely 18–59, 60–79, and 80 or above, with 18–59 set as the reference group. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) is categorized into 4 groups, namely 0, 1–4, 5–6, and 7–14, with 0 being the reference group.

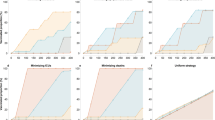

The estimation results for these time-constant variables are shown in Table 1. The time-varying effect of vaccines and oral antiviral drugs are plotted in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

For patients aged between 60 and 79, and those aged above 80, they share a relatively higher risk than adult patients aged below 60, with hazard ratios 2.292 (95% CI 1.954 to 2.689, p < 0.001) and 3.644 (95% CI 3.121 to 4.255, p < 0.001) against severe complications, respectively. The corresponding hazard ratios against death are 2.659 (95% CI 2.187 to 3.233, p < 0.001) and 4.941 (95% CI 4.087 to 5.973, p < 0.001). In both severe complications and death, male patients have a significantly higher risk compared to female patients, with respective hazard ratios 1.220 (95% CI 1.138 to 1.308, p < 0.001) and 1.192 (95% CI 1.108 to 1.283, p < 0.001).

The CCI index is the most widely used scoring system for comorbidities. Compared to patients with a CCI index of zero, the hazard ratios against severe complications are 1.517 (95% CI 1.410 to 1.633, p < 0.001), 2.397 (95% CI 1.910 to 3.007, p < 0.001), and 2.398 (95% CI 2.028 to 2.836, p < 0.001) for CCI index values of 1–4, 5–6, and 7–14, respectively. Compared to patients with a CCI index of zero, the hazard ratios against death are 1.588 (95% CI 1.469 to 1.717, p < 0.001), 2.778 (95% CI 2.214 to 3.486, p < 0.001), and 2.843 (95% CI 2.404 to 3.362, p < 0.001) for CCI index values of 1–4, 5–6, and 7–14, respectively.

Although the time-constant model can provide good estimation of the vaccination effects, a generalized likelihood ratio test indicates that the time-varying model offers a significantly better fit (with p < 0.001) to the data compared to the time-constant model, regardless of whether we are studying complications or mortality.

From the plots of the estimated vaccine PE trajectory in Fig. 2, it is clear that receiving more doses of vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of complications and death overall. Moreover, the PEs are rather stable over time suggesting that the vaccines offer robust and long-lasting protection against severe complications and death. Waning effects of the two types of vaccines become apparent only in the fourth dose. We fit the model again by assuming no waning vaccine effect that the PE is constant over time to compare the two sets of estimates. The results are summarized in Table 2 where we report the peak PE level at \(t=0.5\) month and the PE level at 6 months for each vaccine type and number of doses.

The two sets of PEs are very similar in the cases where the number of doses is 1, 2, or 3, which is expected because there was little waning. For the case with 4 doses, the estimated time-constant PE can be seen as the average of the PEs over time. Therefore, both time-varying and time-constant vaccine effect approaches are reasonable in this application when evaluating the protective efficacy of vaccines against complications or death, but the time-varying approach would be more informative in guiding informed decision.

The estimated trajectory presented in the left panel of Fig. 3 reveals the time-varying effects of antiviral drugs taken within 5 days of confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis. For this group of patients, the protective efficacy against complications reaches a maximum of 0.438 and 0.634, respectively for molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir at around 5 days since prescription of the antiviral drugs. However, the efficacy then decreases to 0.047 for molnupiravir and 0.489 for nirmatrelvir-ritonavir after 28 days. Outside the 5-day window, the time-varying protective efficacy remains stable at 0 for both drugs. Regarding the time-varying effects against death, for patients who took antiviral drugs within 5 days of confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, the PE for molnupiravir reaches a maximum of 0.657 after 1 day and then drops to −0.103 after 28 days. For nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, the maximum protection is achieved at day 3 since prescription with a maximum PE of 0.778, followed by a decline to 0.313 after 28 days. Outside the 5-day window, the PE remains at 0 for molnupiravir, while for patients who took nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, the PE increases to 0.140 one day after prescription and then decreases to −0.789 after 28 days. When assuming time-constant effect for oral antivirals, the PE against complications is 0.540 (95% CI 0.482 to 0.591, p < 0.001) and −0.032 (95% CI −0.718 to 0.380, p = 0.904) for nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, within and outside 5 days respectively, and 0.249 (95% CI 0.186 to 0.308, p < 0.001) and −0.014 (95% CI −0.346 to 0.236, p = 0.924) for molnupiravir, within and outside 5 days respectively. For the PE against death, nirmatrelvir-ritonavir provides 0.622 (95% CI 0.566 to 0.670, p < 0.001) and −0.508 (95% CI −1.300 to 0.012, p = 0.057) within and outside 5 days, respectively, and molnupiravir provides 0.313 (95% CI 0.251 to 0.369, p < 0.001) and 0.038 (95% CI −0.277 to 0.276, p = 0.787) within and outside 5 days, respectively. We summarize the results based on the time-varying and time-constant model in Table 3.

We report the maximum PE level and the time to reach the peak as well as the PE level at \(t=28\) day based on the time-varying model. It is easy to see that the time-constant PE estimate can be regarded as the average of the time-varying PE over time. These findings emphasize the dynamic nature of the protective effects of the oral antiviral drugs over time. The observed variations in PE within 28 days after prescription underscore the importance of considering the temporal aspects of pharmacodynamic relationships when evaluating the potential impact of these interventions on clinical outcomes.

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the time-varying effects of vaccines and oral antiviral drugs in preventing severe complications and mortality associated with COVID-19 infections. The analysis revealed that both interventions exhibited dynamic PE over time, underscoring the critical importance of considering the temporal aspects of these interventions in mitigating the impact of the pandemic.

The results demonstrate that multiple doses of CoronaVac and Comirnaty vaccines provide substantial protection against severe outcomes and death, suggesting potential benefits of additional boosters for certain vaccine types. However, an exponential decay in efficacy was observed within six months of the fourth dose for both vaccines, indicating a possible need for periodic boosters to maintain optimal protection.

The analysis of the oral antiviral drugs, molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, revealed distinct time-varying patterns in their PE. Taking the drugs within 5 days of confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis was found to be more effective than outside this 5-day window. For patients receiving the antiviral drugs within 5 days of confirmed diagnosis, both drugs exhibited maximum protection within the first 5 days since prescription, followed by a gradual decline in efficacy over the subsequent 28 days. In contrast, low or even negative effects would occur for patients who took the antiviral drugs outside the 5-day window of confirmed diagnosis. This finding underscores the critical importance of early intervention with these therapies to optimize their potential benefits in preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes. The observed variations in PE over time highlight the necessity to consider the temporal dynamics of pharmacological interventions when evaluating their impact on clinical outcomes.

The results of this study have important implications for public health policies and clinical practice. The observed time-varying effects of vaccines and antiviral drugs underscore the need for tailored vaccination schedules and treatment protocols. Regular monitoring and adaptive vaccination strategies may be necessary to maintain optimal protection levels and mitigate the impact of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. For oral antivirals it is well established that their effectiveness will be highest if given early in the course of disease36..

The strengths of this study include its use of a comprehensive, territory-wide dataset capturing real-world COVID-19 management in Hong Kong. The ability to link vaccination, oral antiviral usage, and clinical outcome data allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the synergistic effects of these interventions. However, the observational nature of the data may be subject to residual confounding, and the findings may be specific to Hong Kong’s epidemiological context and predominant viral lineages during the study period. Further research in diverse settings would be valuable to confirm the generalizability of these results. Additionally, when considering age and the CCI, different categorization standards may be adopted, while smoothing splines could be an alternative that however would add further complexity to the model. CCI may only partially capture the risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections.

In conclusion, this study provides crucial insights into the time-varying effects of vaccines and oral antiviral drugs in preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes in Hong Kong. The findings highlight the dynamic nature of these interventions and the importance of considering temporal aspects in their implementation and evaluation. Continued research and adaptation of public health strategies will be crucial in the ongoing battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Hospital Authority and the Department of Health of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Hospital Authority and the Department of Health of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

References

World Health Organization COVID-19 dashboard. Accessed on 24 February. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int (2024).

Msemburi, W. et al. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 613, 130–137 (2022).

Park, S. et al. Unreported SARS-CoV-2 home testing and test positivity. JAMA Net. Open. 6(1), e2252684–e2252684 (2023).

Statistics on 5th Wave of COVID-19. Accessed on 24 February. Available online at: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistic s/5th_wave_statistics_20230129.pdf. (2024).

Wong, S.-C. et al. Evolution and Control of COVID-19 Epidemic in Hong Kong. Viruses. 14(11), 2519 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Comparison of control and transmission of COVID-19 across epidemic waves in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Reg. Health. Western Pacific. 43, 100969 (2024).

Murakami, N. et al. Therapeutic advances in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19(1), 38–52 (2023).

Hammond, J. et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. New Engl. J. Med. 386(15), 1397–1408 (2022).

Jayk, B. A. et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of Covid-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. New Engl. J. Med. 386(6), 509–520 (2022).

Wong, C. K. H. et al. Real-world effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir against mortality, hospitalisation, and in-hospital outcomes among community-dwelling, ambulatory patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the omicron wave in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet (British edition). 400(10359), 1213–1222 (2022).

Burdet, C. & Ader, F. Real-world effectiveness of oral antivirals for COVID-19. Lancet (British edition). 400(10359), 1175–1176 (2022).

Mesfin, Y. M. et al. Effectiveness of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir in non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Antimicro. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkae163 (2024).

US Food and Drug Administration. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: emergency use authorization for Lagevrio (molnupiravir) capsules. Accessed on June 30, Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/155054/download (2022).

GovHK. First shipment of COVID-19 oral drug Paxlovid distributed to HA for application (with photos). Accessed on 20 December. Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202203/15/P2022031500280.htm.

GovHK. Introduction of new drugs for treating Coronavirus Disease. Accessed on 20 December 2024. Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202202/23/P2022022300303.htm?fontSize=1. (2019).

The Hospital Authority. Latest information on two types of COVID-19 oral antiviral drugs. Accessed on 20 December. Available online at: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/pad/266364en.pdf. (2024).

Self, W. H. et al. Comparative effectiveness of moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) Vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions - United States, March-August 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Weekly Rep. 70(38), 1337–1343 (2021).

McMenamin, M. E. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22(10), 1435–1443 (2022).

Thomas, S. J. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. New Engl. J. Med. 385(19), 1761–1773 (2021).

Israel, A. et al. Elapsed time since BNT162b2 vaccine and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection: test negative design study. BMJ (Online). 375, e067873–e067873 (2021).

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. SFH Authorises COVID-19 Vaccine by Fosun Pharma/BioNTech for Emergency Use in Hong Kong. Accessed on 24 February. Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202101/25/P2021012500829.htm. (2024).

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. SFH Authorises COVID-19 Vaccine by Sinovac for Emergency use in Hong Kong. Accessed on 24 February. Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202102/18/P2021021800495.htm. (2024).

Goldberg, Y. et al. Waning immunity after the BNT162b2 Vaccine in Israel. New Engl. J. Med. 385(24), e85–e85 (2021).

Andrews, N. et al. Duration of protection against Mild and severe disease by Covid-19 Vaccines. New Engl. J. Med. 386(4), 340–350 (2022).

Suah, J. L. et al. Waning COVID-19 Vaccine effectiveness for BNT162b2 and CoronaVac in Malaysia: An observational study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 119, 69–76 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac and BNT162b2 vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 Omicron BA 2 infections in Hong Kong. J. Infect. Dis. 226(8), 1382–1384 (2022).

Jara, A. et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Chile. New Engl. J. Med. 385(10), 875–884 (2021).

Lin, D.-Y. et al. Effectiveness of XBB 1.5 vaccines and antiviral drugs against severe outcomes of omicron infection in the USA. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24(5), e278–e280 (2024).

Cheung, Y. Y. H. et al. Effectiveness of Vaccines and Antiviral Drugs in Preventing Severe and Fatal COVID-19. Hong Kong. Emerging Infect. Dis. 30(1), 70–78 (2024).

Cheung, Y. Y. H. et al. Joint analysis of vaccination effectiveness and antiviral drug effectiveness for COVID-19: a causal inference approach. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 143, 107012–107012 (2024).

Cheung, Y. B. et al. Estimation of intervention effects using first or multiple episodes in clinical trials: The Andersen-Gill model re-examined. Stat. Med. 29(3), 328–336 (2010).

Xu, J. et al. Semiparametric estimation of time-varying intervention effects using recurrent event data. Stat. Med. 36(17), 2682–2696 (2017).

Lau, J. J. et al. Real world COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron BA 2 variant in a SARS-CoV-2 infection-naive population. Nat. Med. 29(2), 348–357 (2023).

Rennert, L. et al. Effectiveness and protection duration of Covid-19 Vaccines and previous infection against any SARS-CoV-2 infection in young adults. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 3946–3948 (2022).

Cheung, Y. B. et al. Estimation of trajectory of protective efficacy in infectious disease prevention trials using recurrent event times. Stati. Med. 43(9), 1759–1773 (2024).

Bertuccio, P. et al. The impact of early therapies for COVID-19 on death, hospitalization and persisting symptoms: a retrospective study. Infect. 51(6), 1633–1644 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund of the Health Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (grant no. CID-HKU2-12) and the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. T11-705/21-N). BJC is supported by an RGC Senior Research Fellowship from the University Grants Committee of Hong Kong (grant number: HKU SRFS2021-7S03). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Funding

Health Bureau, CID-HKU2-12, CID-HKU2-12, Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, T11-705/21-N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J., B.J.C. and K.F.L; methodology, J.J., E.H.Y.L., G.Y. and K.F.L.; software, J.J.; validation, J.J.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, J.J.; resources, B.J.C. and K.F.L.; data curation, J.J., Y.L. and E.H.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J., E.H.Y.L., G.Y., B.J.C. and K.F.L.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, E.H.Y.L., G.Y., B.J.C. and K.F.L.; project administration, B.J.C. and K.F.L.; funding acquisition, B.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

BJC consults for AstraZeneca, Fosun Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Haleon, Moderna, Novavax, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi Pasteur. The other authors report no other potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J., Lam, K.F., Lau, E.H.Y. et al. Joint analysis of time-varying effect of vaccine and antiviral drug for preventing severe complications and mortality. Sci Rep 15, 5640 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89043-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89043-8