Abstract

This paper employs game theory to examine the impact of the dual-helix structure mechanism on the evolutionary trends of reversed online public opinion, providing a theoretical foundation for public opinion management. Building on the theoretical framework of game theory, the study constructs an evolutionary game model under the dual-helix structure involving online media and opinion leaders as the game participants. It calculates the payoff matrices and replicator dynamics equations of the parties involved and uses numerical simulation methods to assess the stability of various equilibrium points and to deduce the behavioral strategies of the parties under different conditions. The findings indicate that the size of credibility gains achieved by opinion leaders, the severity of governmental sanctions and the traffic revenue obtained by online media significantly influence the strategic choices of the parties involved. Based on these findings, the study proposes recommendations for the management of reversed online public opinion from a governmental perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of internet technologies and the proliferation of social networks, the public discourse is increasingly inundated with social phenomena such as misinformation, privacy breaches, shifts in public opinion, cyber violence, derivative issues, and ethical dilemmas, all of which can have significant implications for societal stability. Among these, public opinion reversals, a common phenomenon in online public opinion, have become more frequent and intense in recent years, exemplified by incidents such as the “Fat Cat” incident (2024), the “Ice and Snow World Ticket Refund” incident (2023), and the “Meituan Delivery Extortion” incident (2022). These reversals in public opinion can severely harm the individuals involved, impact media credibility, reduce the trust in relevant authorities, and disrupt the harmonious development of the online ecosystem. This paper investigates the evolutionary trends of such reversals in online public opinion and explores governance strategies to effectively regulate and foster a green and healthy online environment.

Recent scholarly work has identified the presence of phenomena such as the silence spiral and the anti-silence spiral in the dissemination of public opinion, leading to extensive research in this area. For instance, Zhang and colleagues1 applied the theory of the silence spiral, combined with an analysis of the information lifecycle, to explore the evolution and mechanisms of online public opinion. Ke2 noted that in the new communicative environment, the anti-silence spiral phenomenon has gradually emerged, effectively preventing the tyranny of the majority and maintaining ecological balance within the online community. Other scholars have further discussed the role of the dual spiral theory in the evolution of public opinion3,4, such as Zhao and colleagues5, who analyzed the interplay between the silence spiral and the anti-silence spiral using the “Rolle Incident” as a case study. Concerning specific reversal phenomena in public opinion, researchers like Li Yong et al.6 have explored the mechanisms behind online public opinion reversal by studying the anti-silence spiral phenomenon during such reversals. Gao et al.7 examined the theoretical assumptions and research challenges of the silence spiral theory, proposing the interactive effects of a dual spiral. Despite these studies, the proposed strategies for guiding public opinion generally lack specificity and effectiveness, making it challenging to empirically demonstrate whether they achieve the intended effects. This paper proposes a new mechanism, examining the impact of the dual spiral theory on the evolutionary trends of online public opinion reversal. By employing game theory to simulate the decision-making processes of stakeholders, this study offers more targeted and concrete proposals for the governance of reversals in online public opinion.

Related research

In recent years, the frequent occurrence of various online public opinion events has exerted considerable negative impacts on society and the public, rendering online public opinion a deeply investigated field. Currently, research on online public opinion primarily focuses on aspects such as influencing factors8, predictive analytics9, the evolutionary patterns of dissemination, simulation models10, and response strategies11. For example, Wang L et al.8 suggested that the emotional reactions of netizens, herd mentality, and the level of attention directed towards an event all influence the directional development of public opinion; Mu and colleagues9 developed an IPSO-LSTM hybrid forecasting model to predict and analyze the dissemination trends of emergent public opinion events, concluding that the model possesses high predictive accuracy. Li and others10 introduced factors such as topic popularity and user interest to construct an improved SEIR model, exploring the impact of various factors on the evolutionary process of public opinion dissemination.

As research into the laws governing the dissemination of online public opinion deepens, many scholars have observed that public opinion events frequently exhibit phenomena of opinion reversal, which significantly influence opinion evolution. Reversal in online public opinion refers to a social phenomenon in which public perceptions and emotions about a particular trending event undergo significant changes as the truth progressively unfolds6. Addressing the evolution of reversed online public opinion, numerous scholars have constructed simulation models11,12,13,14,15,16,17 to investigate the influencing factors, underlying mechanisms, and the evolution of opinions among various stakeholders, subsequently proposing strategies for response. For instance, Chen et al.18 explored the impact of the number of opinion leaders and the intensity of their opinion shifts on public opinion reversal; Liu and colleagues19 focused on opinion leaders to study the internal mechanisms of online public opinion reversal, aiming to achieve efficient governance of online public opinion13; Chica et al.20 employed game theory and agent-based models to simulate the interactions and opinion formation processes among individuals, while Di Mare and others21 further simulated the basic interaction mechanisms between two individuals; Sznajd-Weron K et al.22 discussed a simple mechanism based on the Ising spin model to describe the evolution of opinions within closed communities; some scholars19 noted that when individual opinions exceed a threshold, they tend to converge towards the average, whereas below the threshold, they may lead to the formation of multiple opinion clusters; other researchers explored how opinions evolve and spread in social networks based on evolutionary game models of opinion dissemination, where opinions are updated and propagated based on individual decision-making processes and local interactions23,24, as well as issues of consensus25; Chen and others26 constructed models that incorporate external intervention information and individual intrinsic characteristics to explore the evolutionary patterns of opinion reversal; Zhang and colleagues27 analyzed media reports, netizen behavior, and group pressures among other conditional variables to investigate the combinatory logic and formation pathways of online public opinion reversal.

Moreover, the majority of scholars investigating the dynamics of the reversal in online public opinion have integrated prominent theories such as Prospect Theory1, the “anti-silence spiral” Theory6, Lifecycle Theory28, Social Combustion Theory29, and Agenda Setting30. However, few have paid attention to the role of the dual spiral structure of silence in the evolution of the reversal in online public opinion. According to the literature7, two opposing opinion spirals can engage in a benign interaction, influencing individuals’ conceptual stances and behavioral patterns, and ultimately shaping the public opinion construct regarding specific events. This characteristic is notably correlated with the genesis and evolution of the reversal in online public opinion. Therefore, this article proposes a dual spiral mechanism for the reversal in online public opinion and develops an evolutionary game model that incorporates this structure, aiming to explore the impact of the dual spiral mechanism on the evolutionary trends of the reversal in online public opinion, thereby enhancing the overall governance of public sentiment and purifying the online space. The concise schematic figure of the paper is shown in Fig. 1.

Construction of the dual spiral mechanism for reversal in online public opinion

Theoretical introduction and assumptions of the “silence spiral”

In 1965, during the public opinion surveys of a major election involving two political parties in Germany, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann observed a significant “last-minute follow-through” phenomenon—akin to an avalanche effect—with the two parties maintaining close support rates until the final voting results were dramatically skewed. This phenomenon was subsequently conceptualized as the “silence spiral” theory31. In 1972, Noelle-Neumann formally introduced this theory at the World Congress of Psychology held in Tokyo.

The foundational assumptions of the theory are threefold: (1) Contradicting the prevailing public opinion induces feelings of isolation32; (2) Humans innately fear isolation33, which prompts continuous evaluation of socially acceptable opinions; (3) This evaluation guides individuals in deciding whether to conceal or express their views32. Thus, the theory posits that most individuals within a group first observe the attitudes and opinions of those around them. When their views contradict the majority, feelings of loneliness and fear arise, compelling them under pressure to either abandon their views, shift their support, or remain silent. This process reinforces the prevailing opinion climate within the group, which in turn exerts pressure on the minority, perpetuating a rising cycle of the “silence spiral”5.

Proposal and conditions for the emergence of the anti-silence spiral theory

In recent years, the advent of the internet era has significantly challenged the assumptions underpinning the “silence spiral” theory, which posits that fear of isolation drives conformity in opinion expression. The characteristics of anonymity and virtuality in new media environments have disrupted this theory by reducing the concerns individuals have about expressing divergent views, thereby replacing the fear of isolation with a stronger inclination towards self-expression34. Consequently, the traditional media’s silence spiral has been inverted, giving rise to what is now referred to as the “anti-silence spiral.” This concept is also articulated in the current literature as “anti-silence spiral,” “antithesis of the silence spiral,” “reversal of the silence spiral,” and “transformative spiral,” all of which convey similar meanings6. This paper adopts the term “anti-silence spiral.”

The establishment of this theory is predicated on three primary conditions:1)The open sharing of information within the internet environment350.2)The difficulty individuals face in controlling and perceiving the “opinion climate” within the context of the internet and new media360.3)In the new media era, the public sphere includes a minority of opinion leaders and core supporters who consistently maintain their viewpoints. According to this theory, on virtual community platforms on the internet, netizens holding minority opinions do not choose silence even under the pressure of dominant views. Instead, they are emboldened to express their perspectives. As the communication process evolves and interactions deepen, these minority views may gain wider acceptance and recognition, thereby establishing a “anti-silence spiral”34.

Introduction of the “dual silence spiral” structure

Building upon the foundational theories of the “silence spiral” and the “anti-silence spiral,” this paper posits that while the traditional “silence spiral” may be somewhat weakened in new media environments, and the “anti-silence spiral” becomes more pronounced, these theories are not static. Rather, they exist in a dynamic equilibrium characterized by mutual complementarity, transformation, and permeation. Consequently, this paper introduces the concept of the “dual silence spiral” as a framework for understanding the generation and propagation of public opinion in new media contexts. This structure elucidates the mechanisms by which these dual spirals influence the reversal of online public opinion, with the operational mechanism illustrated in Fig. 2 and the game-theoretic process depicted in Fig. 3. Initially, upon the occurrence of a public opinion event, mainstream media coverage tends to create a “silence spiral.” Simultaneously, specific social groups, utilizing new media technologies and platforms, generate a “anti-silence spiral.” These two spirals then operate alternately but maintain a dynamic balance within a given field. Subsequently, both mainstream media and specific social groups engage in interactive gaming within this field, which leads to the formation of public opinion. Ultimately, the public opinion formed influences individual perspectives and behaviors.

Construction of the evolutionary game model of network public opinion reversal

Determination of game participants and strategies

Based on the “silent dual-helix” structure depicted in Fig. 2, this paper examines the strategic interactions between mass media (specifically online media) and particular social groups (represented by opinion leaders) within the context of the evolutionary game theory applied to reversal phenomena in online public opinion.

Currently, online media serve as the most frequently used platforms for information dissemination and exert a significant influence on reversed online public opinion. If online media prioritize “scooping exclusives, speed, and generating traffic” over verifying the accuracy of the facts, they can easily mislead the direction of public opinion. Conversely, if online media conduct thorough investigations and multiple verifications before publishing information related to an event, it can help clarify the public opinion surrounding the event in a short amount of time. Therefore, the strategies for online media are defined as {objective reporting, biased reporting}. Opinion leaders are individuals or groups with charismatic personalities and high social status who typically express their views based on their own sources of information, educational background, and personal attitudes. However, they may sometimes choose to remain silent due to the fear of isolation. Thus, the strategies for opinion leaders are set as {active voicing, maintaining silence}.

Drawing on contemporary scholarship that addresses the influential factors within the evolutionary game process of online public opinion, this study hypothesizes and explicates the primary parameters involved in the strategic interplay between online media and opinion leaders. The strategic combinations and main parameters relevant to this game are outlined in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

-

1.

Benefit \(\:{R}_{1}\) for opinion leaders: gaining a sense of participation and belonging

When opinion leaders actively engage in discussions surrounding events in online public opinion, they experience significant psychological fulfillment from being part of the discourse—evident through likes, comments, and shares from numerous netizens. Furthermore, by voicing their opinions, opinion leaders attract individuals with similar viewpoints, thereby reinforcing their sense of not being isolated entities but part of a group with shared values and objectives.

-

2.

Benefits \(\:{R}_{2}\) for opinion leaders from remaining silent, primarily avoiding social isolation

In the realm of online public opinion, the views of opinion leaders often attract widespread attention. Under the influence of the “silence spiral” theory, if their expressed opinions on controversial topics diverge from mainstream views or the stance of the majority, they may provoke vigorous criticism and accusations, and potentially malicious attacks. However, when opinion leaders choose to remain silent, they avoid the potential backlash and social isolation that might arise from expressing controversial views. This silence acts as a refuge from the potential “storm” of public opinion. Moreover, by staying silent, opinion leaders can distance themselves from negative emotions, thereby avoiding psychological stress and maintaining a state of relative tranquility.

-

3.

Credibility gains \(\:{R}_{3}\) accrued by opinion leaders through active participation

In discussions on various topics within online public opinion, the active participation of opinion leaders typically signifies the dissemination of their expertise. This expertise, once recognized by the audience, establishes their reputation as reliable sources of information in their respective fields. When opinion leaders maintain an impartial stance on contentious issues during active engagement, they significantly enhance their credibility for integrity. Furthermore, if opinion leaders ensure the accuracy of their information through a meticulous verification process, they establish a reliable image in the minds of their audience, thereby gaining credibility for reliability.

-

4.

Trust benefits \(\:{R}_{4}\) for online media from impartial reporting due to public endorsement

When online media engage in impartial reporting, the information presented is meticulously investigated and verified. Audience access to accurate reports allows them to understand the true nature of events, fostering trust in the online media, and resulting in trust benefits. Furthermore, when online media objectively narrate and analyze relevant hot topics, providing comprehensive information to the audience, they foster a positive reception. As audiences access valuable information, they develop a favorable view of the media, potentially becoming loyal users, which in turn enhances the trust benefits for the media.

-

5.

Attention and audience growth benefits \(\:{R}_{5}\) for online media from impartial reporting

When users perceive online media as consistently maintaining objectivity and fairness in their reporting of various events, they develop a reliance on that media, which often translates into long-term loyalty and sustained engagement. Additionally, just as one might recommend high-quality products, users are inclined to recommend these media outlets to family, friends, and colleagues, thereby contributing to an increase in attention and audience growth for the media.

-

6.

Traffic growth benefits \(\:{\:\text{R}}_{6}\)for online media from biased reporting

During events of high public interest, some online media entities may engage in overtly biased reporting to quickly tap into the topic, thereby resonating with and sparking discussions among the general public. This can lead to a significant short-term increase in web traffic. Moreover, the nature of biased reporting, characterized by incomplete or one-sided viewpoints or information, tends to provoke controversies on social media. Such debates further enhance the visibility of these media on social platforms, attracting more users to click and view, thus facilitating traffic growth benefits for the media.

-

7.

Costs \(\:{C}_{1}\) incurred by opinion leaders for clarifying facts during active participation

When opinion leaders decide to actively participate and clarify facts, they must gather extensive information. This involves filtering through various sources to find content relevant to the incident, which may include reviewing news reports, research studies, and multiple perspectives on social media, or even contacting involved parties or institutions for firsthand data. Additionally, opinion leaders employ professional data analysis tools or consult with experts in the field to cross-verify data and authenticate testimonies.

-

8.

Resource costs (labor, time) \(\:{C}_{2}\) for online media in conducting objective reporting

Online media expend considerable time and effort in conducting investigations to ensure objective reporting on trending topics of public opinion. Moreover, to verify the reliability of the evidence collected, they may need to engage with multiple authoritative bodies or academic experts for multi-faceted validation, a process that can span weeks or even months.

-

9.

Credibility loss costs \(\:{C}_{3}\) for online media due to biased reporting

In the realm of media, credibility serves as a fundamental basis for mutual recognition and respect. When online media engage in biased reporting, it can easily trigger widespread criticism from the general public, civil monitoring organizations, and industry associations, creating a negative public opinion environment. The loss of reputation among peers may lead to reduced content collaboration, information sharing, and industry exchanges with other media outlets.

-

10.

Penalties faced by online media from government sanctions for misleading the public \(\:{C}_{4}\)

According to relevant regulations, for initial or minor instances of biased reporting, regulatory bodies such as the Department of cyber administration may issue warnings to the online media involved, demanding written self-criticism and the submission of a rectification plan. Such measures aim to clarify improvements in reporting methods and strengthen content review to prevent similar issues from recurring. Additionally, the government may also require the online media to publicly clarify the facts to mitigate adverse effects.

-

11.

Potential damage \(\:{L}_{1}\) to image and reputation for opinion leaders who choose to remain silent

Opinion leaders who choose to remain silent may experience a decrease in interaction with their followers, leading to a gradual shrinkage of their existing communication networks. As followers often seek intellectual exchange and resonance with opinion leaders, prolonged silence from these influencers can result in a loss of engagement. For instance, social media influencers who fail to update content or participate in discussions may see a significant decline in follower interaction and engagement, subsequently affecting their reputation and image.

-

12.

Potential traffic loss \(\:{L}_{2}\) for online media due to objective reporting

When online media invest significant time and effort in investigating and verifying facts for objective reporting, the delay in publishing pertinent information may create an impression of untimeliness and inconvenience in information access among users. Over time, this perception can lead users to decrease their visits to these media outlets, opting instead for alternatives that provide timely information. This shift can ultimately affect the media’s traffic and user retention.

Model assumptions

Based on the actual dynamics of opinion leaders and online media, the following assumptions are made for this evolutionary game model:

-

1.

The game participants are defined as opinion leaders and online media, both of which are assumed to be boundedly rational and aim to maximize their own interests. The strategy set for opinion leaders is A1= {active voicing, maintaining silence}; the strategy set for online media is A2= {objective reporting, biased reporting}.

-

2.

It is assumed that the probability of opinion leaders choosing active voicing and maintaining silence are\(\:x\left(0\le\:x\le\:1\right)\)and 1-x respectively; the probabilities for online media choosing objective reporting and biased reporting are\(\:y\left(0\le\:y\le\:1\right)\) and 1-y, respectively.

-

3.

When online media engage in objective reporting and opinion leaders actively voice their opinions, online media incur human and time costs \(\:{C}_{2}\), but also gain trust benefits \(\:{R}_{4}\), due to public recognition. However, they may experience a loss in traffic \(\:{L}_{2\:}\)due to delays in publishing information. Opinion leaders gain benefits of involvement and belonging \(\:{R}_{1}\).

-

4.

When online media report objectively and opinion leaders maintain silence, some of the public may unfollow the silent opinion leaders and shift their attention to online media, resulting in an increase in attention and related benefits \(\:{R}_{5}\) for the media. The media also incur costs \(\:{C}_{2}\) for information searching and fact verification. Opinion leaders, by maintaining silence, gain benefits from avoiding isolation \(\:{R}_{2}\) but suffer losses in image, reputation, and recognition \(\:{L}_{1}\).

-

5.

When online media engage in biased reporting and opinion leaders actively voice their concerns, the truth can be clarified. Opinion leaders incur costs \(\:{C}_{1}\) for fact clarification but gain reputation benefits \(\:{R}_{3}\) and a sense of involvement and belonging \(\:{R}_{1}\). online media incur a reduction in credibility \(\:{C}_{3}\), and potential government penalties \(\:{C}_{4}\) for misleading the public, but they may gain increased traffic \(\:{R}_{6}\).

-

6.

When online media engage in biased reporting and opinion leaders maintain silence, opinion leaders gain benefits from avoiding isolation \(\:{R}_{2}\) but suffer damage to their image and reputation \(\:{L}_{1}\). Online media incur a reduction in credibility \(\:{C}_{3}\), and face potential government penalties \(\:{C}_{4}\) for further exacerbating the public opinion crisis, but they may gain traffic benefits \(\:{R}_{6}\).

Model construction

Based on the model assumptions, the payoff matrix for opinion leaders and online media during the game process is shown in Table 3.

Using the payoff matrix from Table 3, the expected payoffs for the opinion leader adopting the “active voicing” and “maintaining silence” strategies are denoted as \(\:{U}_{11}\) and \(\:{U}_{12}\), respectively, with the average expected payoff as \(\:\overline{{U}_{1}}\). These are calculated as:

From Eqs. (1) and (3), we can construct the replicator dynamic equation for the decision-making behavior of opinion leaders as:

Similarly, for the online media adopting “objective reporting” and “biased reporting,” the expected payoffs are \(\:{U}_{21}\) and \(\:{U}_{22}\), respectively, with the average expected payoff as \(\:\overline{{U}_{2}}\). These are calculated as:

Using Eqs. (5) and (7), the replicator dynamic equation for the decision-making behavior of online media is:

The dynamic system consisting of Eqs. (4) and (8):

The dynamic system allows us to analyze the evolutionarily stable strategies of opinion leaders and online media. Setting \(\:{G}_{x}\)=\(\:{G}_{y}\)=0, we identify five locally stable points: A(0,1), B(0,0), C(1,0), D(1,1), and \(\:{\text{E}(\text{x}}^{\text{*}},{\text{y}}^{\text{*}})\), where \(\:{x}^{*}=({C}_{3}-{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6})/({L}_{2}-{R}_{4}+{R}_{5})\), and\(\:\:{y}^{*}=-({L}_{1}{-C}_{1}{+R}_{1}-{R}_{2}{+R}_{3})/{C}_{1}\). Following Friedman’s method, we use the Jacobian matrix to analyze the local stability of these points. By deriving the partial derivatives, the Jacobian matrix J is:

According to the relevant knowledge of evolutionary game theory, the equilibrium point obtained by the replication dynamic equation is not necessarily the final evolutionary stable strategy of the system. Only when the determinant \(\:det\left(J\right)>0\) and trace \(\:tr\left(J\right)<0\)of the Jacobian matrix are satisfied simultaneously will the system be in a stable state. Then, the system equilibria A (0,1), B (0,0), C (1,0), D (1,1), and E (\(\:{x}^{\text{*}},\:\:{y}^{\text{*}}\)) are brought into the expressions of the determinant and trace of the matrix. The results are shown in Table 4.

Based on the assumption that only points within the two-dimensional space defined by \(\:\text{V}=\left\{\left(\text{x},\text{y}\right)|0\le\:\text{x}\le\:\text{1,0}\le\:\text{y}\le\:1\right\}\) are meaningful, we can infer that the following conditions hold: \(\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{2}{+C}_{4}{-R}_{6}-{L}_{2}{+R}_{4}<0\)and \(\:{{R}_{2}-L}_{1}{-R}_{1}-{R}_{3}<0\). Table 4 indicates that the trace of the Jacobian matrix at equilibrium point \(\:\text{E}({\text{x}}^{\text{*}},{\text{y}}^{\text{*}})\) is \(\:\text{t}\text{r}\left(\text{J}\right)\)=0, which implies that E(\(\:{\text{x}}^{\text{*}},\:{\text{y}}^{\text{*}}\)) is not an evolutionarily stable strategy under any circumstances. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the stability of the other four equilibrium points individually to determine under which conditions they represent evolutionarily stable strategies.

-

①

At equilibrium point A (0, 1).

For A (0, 1) to be an evolutionarily stable strategy, the determinant of the Jacobian matrix, \(\:\text{d}\text{e}\text{t}(\text{J}\)), must be positive and the trace, \(\:\text{t}\text{r}\left(\text{J}\right)\), negative. This is only possible if conditions (10) and (11) are satisfied:

$$\:-({L}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3})*({C}_{3}-{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6})\:>0$$(10)$$\:{C}_{2}-{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{1}\:{+R}_{1}\:{-R}_{2}{+R}_{3}-{R}_{5}+{R}_{6}<0$$(11)Given that \(\:{{L}_{1}+R}_{1}{-R}_{2}+{R}_{3}>0\), when condition (10) is satisfied, it results in \(\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6}<0\). However, under such circumstances, condition (11) is not met, rendering A(0,1) non-asymptotically stable under any conditions.

-

②

At equilibrium point B (0, 0).

If meeting equilibrium point B (0, 0) is the evolutionary stability strategy of the system, that is, the determinant of equilibrium point B (0, 0), \(\:\text{d}\text{e}\text{t}(\text{J}\)), must be positive and the trace, \(\:\text{t}\text{r}\left(\text{J}\right)\), negative. Only when the two conditions of Formulas (12) and (13) are satisfied, the system will gradually tend to a stable state.

$$\:({L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3})*({C}_{3}-\:{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6})>0$$(12)$$\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{2}-{C}_{1}+{C}_{4}+{L}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6}\:\:<0$$(13)When both \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}<0\), and \(\:{C}_{3}-\:{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6}<0\), conditions (12) and (13) are met, making B (0, 0) an asymptotically stable point.

-

③

At equilibrium point C (1, 0).

For the equilibrium point C (1, 0) to represent an evolutionarily stable strategy, the determinant of this point, det(J), must be positive, and the trace, tr(J), negative. The system will tend towards stability only if the following conditions are met:

$$\:({L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3})*({C}_{2}-{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{2}-{R}_{4}+\:{R}_{6})\:>0$$(14)$$\:{{C}_{1}-C}_{2}+{C}_{3}+{C}_{4}-{L}_{1}-\:{L}_{2}-{R}_{1}+{R}_{2}-{R}_{3}+{R}_{4}-{R}_{6}\:<0$$(15)When both \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}>0\), and \(\:{C}_{2}-\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{2}-{R}_{4}+{R}_{6}>0\), conditions (14) and (15) are met, making C (1, 0) an asymptotically stable point.

-

④

At equilibrium point D (1, 1).

For equilibrium point D (1, 1) to qualify as evolutionarily stable, the determinant of this point, det(J), must be positive, and the trace, tr(J), negative, with stability achieved only under the following conditions:

$$\:-({L}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3})*({C}_{2}-{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{2}-{R}_{4}\:{+R}_{6})\:\:>0$$(16)$$\:{C}_{2}-{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}-{L}_{1}+{L}_{2}-\:{R}_{1}+{R}_{2}-{R}_{3}-{R}_{4}+{R}_{6}\:<0$$(17)Given that \(\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{2}{+C}_{4}{-R}_{6}-{L}_{2}{+R}_{4}<0\) and \(\:{{R}_{2}-L}_{1}{-R}_{1}-{R}_{3}<0\), both conditions (16) and (17) are simultaneously not satisfied, thereby establishing D(1, 1) as an non-asymptotically stable point. The stability analysis of each equilibrium point is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 Stability of equilibrium points.

Simulation experiments and analysis

Interactive model of game theoretic agents

To delve deeper into the evolutionary mechanisms of reversal in online public opinion, this study employs Vensim software to construct an interactive model involving opinion leaders and online media entities. This model closely associates the game participants and their payoffs, facilitating a more thorough understanding of the game process, as depicted in Fig. 4.

Simulation of evolutionary trajectories for different ESS

Merely analyzing the model theoretically does not provide a clear, intuitive understanding of how various parameters affect the stability of the system’s evolution. Therefore, this paper utilizes Matlab 2021a software to simulate the strategic evolution trajectories of participants in reversed online public opinion scenarios, thereby validating the theoretical analysis presented earlier. The numerical simulation was set up as follows: the proportion of opinion leaders adopting the “active voicing” strategy varied from 0.1 to 0.9, and the proportion of online media adopting the “objective reporting” strategy also ranged from 0.1 to 0.9, in increments of 0.1.

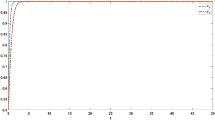

① Numerical simulation analysis at equilibrium point B (0, 0).

As indicated in Table 5, the conditions for asymptotic stability at B(0, 0) are \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}<0\) and \(\:{C}_{3}-\:{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6}<0\). Based on these conditions, a numerical simulation was conducted with parameters set as: \(\:{R}_{1}{=5,\:R}_{2}=10{,R}_{3}{=5,R}_{4}=10{,R}_{5\:}=10,{R}_{6}=15,{C}_{1}=10,{C}_{2}=20,{C}_{3}=10,{C}_{4}=5,{L}_{1}=5,{L}_{2}=20\). The probability of opinion leaders engaging in active voicing was \(\:{p}_{1}=0.5\) and the probability of online media engaging in objective reporting was \(\:{p}_{2}=0.5\). The results of the simulation, as shown in Fig. 5, demonstrate that when the conditions \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}<0\) and \(\:{C}_{3}-\:{C}_{2}+{C}_{4}+{R}_{5}-{R}_{6}<0\) are met, the game strategies of opinion leaders and online media evolve towards Equilibrium Point B (0, 0) and ultimately stabilize. This results in opinion leaders ultimately adopting the strategy of “remaining silent,” and online media opting for “biased reporting,” aligning with the theoretical analysis.

② Numerical simulation analysis at equilibrium point C (1, 0).

Table 5 indicates that the conditions for asymptotic stability at C(1, 0) are \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}>0\) and \(\:{C}_{2}-\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{2}-{R}_{4}+{R}_{6}>0\). Based on these conditions, a numerical simulation was conducted with parameters set as: \(\:{R}_{1}{=10,R}_{2}=10{,R}_{3}=10{,R}_{4}=5{,R}_{5}{=10,{R}_{6}=15,C}_{1}=10{,C}_{2}=5,{C}_{3}{=5,C}_{4}=5,{L}_{1}=5{,L}_{2}=20\). The probability of opinion leaders engaging in active voicing was \(\:{p}_{1}=0.5\) and the probability of online media engaging in objective reporting was \(\:{p}_{2}=0.5\). The results, as depicted in Fig. 6, reveal that when the conditions \(\:{L}_{1}-{C}_{1}+{R}_{1}-{R}_{2}+{R}_{3}>0\) and \(\:{C}_{2}-\:{C}_{3}-{C}_{4}+{L}_{2}-{R}_{4}+{R}_{6}>0\) are satisfied, the game strategies of opinion leaders and online media evolve towards Equilibrium Point C (1, 0) and ultimately stabilize. This results in opinion leaders ultimately choosing the strategy of “active voicing” and online media opting for “biased reporting,” consistent with the theoretical analysis.

Drawing on the research discussed above, this game system has two stable points: B(0, 0) and C(1, 0). This suggests that online media are inclined to adopt the “biased reporting” strategy, while opinion leaders can choose between the “active voicing” strategy and the “maintaining silence” strategy. The emergence of this phenomenon stems from a complex interplay of interests within the interest - gaming field and the communication ecosystem. If online media choose to pursue objective reporting, they must invest substantial human and temporal resources in conducting comprehensive fact-checking and multi-perspective information collection to reveal the truth. At this juncture, online media may face the challenge that the truth is “unremarkable,” resulting in low traffic and a lack of audience engagement. They may struggle to cover their costs due to the significant investigation expenses incurred during the initial stages. Conversely, if online media opt for biased reporting, which entails minimal investigation costs, they can quickly attract audience attention, incite controversies and concerns, and maximize traffic in a short period. Consequently, the “shortcut” of biased reporting is particularly appealing to online media, making them more inclined to adopt this strategy.

Although online media often adopt a “biased reporting” strategy, the public is not necessarily influenced by such reports. On one hand, the public possesses a certain capacity to filter information. Through long-term exposure to online information, individuals gradually learn to cross-verify information from different sources. Even when confronted with the guidance of some opinion leaders or the biased reporting of online media, they strive to uncover the truth. On the other hand, not all opinion leaders are inclined to disseminate one-sided information. Some socially responsible opinion leaders, drawing on their professional expertise, provide objective analyses at critical moments, thereby countering the unidirectional trends of public opinion and becoming a crucial force in balancing the information ecosystem.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the impact of variations in key parameters on the system’s evolutionary path, equilibrium strategies, and stability, a sensitivity analysis was conducted.This analysis seeks to explore how these key parameters influence decision-making processes among the stakeholders involved.The initial probabilities for the strategies of opinion leaders actively engaging and the media reporting objectively were maintained at 0.5, consistent with the parameters used in Sect. 4.1.

Impact of credibility gains for opinion leaders on system evolution

As previously discussed, opinion leaders often engage in “active voicing” in response to one-sided media coverage, particularly in cases of public opinion reversal. Some media outlets, without fully investigating the facts, report these events in a biased manner, leading to public deception and misunderstandings, or even cyber-violence against the individuals involved. Under the influence of the “anti-silence spiral” theory, opinion leaders overcome the fear of isolation by voicing their opinions, which can ultimately reverse the tide of public opinion and clarify the truth.

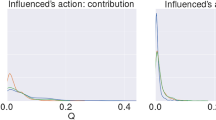

To examine the impact of the parameter \(\:{R}_{3}\) on the evolutionary system under the strategic choices of both parties, the simulation considers the equilibrium point C(1, 0) with parameters set as follows: \(\:{R}_{1}{=10,R}_{2}=10{,R}_{3}=10{,R}_{4}=5{,R}_{5}{=10,{R}_{6}=15,C}_{1}=10{,C}_{2}=5,{C}_{3}{=5,C}_{4}=5,{L}_{1}=5{,L}_{2}=20\). By increasing the value of \(\:{\:R}_{3}\) in increments from 5 to 25, we observe the influence of credibility gains on the strategic choices of opinion leaders. As shown in Fig. 7, the higher the credibility gain received by the opinion leaders, the more likely they are to engage in active voicing; conversely, lower credibility gains tend to make them opt for silence.

Under the “anti-silence spiral” framework, when a minority of well-informed and knowledgeable opinion leaders express their views on a reversed online public opinion event, they can quickly restore the factual truth. At this point, these opinion leaders gain substantial public support and trust, further enhancing their social status. Consequently, they are more likely to pay attention to and actively voice their opinions on potential reversed public opinion events. However, if the strategy of active voicing does not garner public approval and support, or if the benefits of active voicing are outweighed by those of remaining silent, opinion leaders will tend to choose silence.

Impact of the benefits of avoiding isolation for opinion leaders on system evolution

Previous discussions have established that when online media resort to biased reporting, opinion leaders choose to remain silent. Under the influence of the “silence spiral,” these leaders opt to avoid alienation by the public rather than actively voicing their opinions, thus adopting a strategy of “maintaining silence.”

To examine how the benefit of avoiding isolation \(\:{R}_{2}\) affects system evolution when opinion leaders choose to remain silent, we refer to equilibrium point B(0, 0) with the parameters: \(\:{R}_{1}{=5,\:R}_{2}=10{,R}_{3}{=5,R}_{4}=10{,R}_{5\:}=10,{R}_{6}=15,{C}_{1}=10,{C}_{2}=20,{C}_{3}=10,{C}_{4}=5,{L}_{1}=5,{L}_{2}=20\). By varying the value of \(\:{R}_{2}\) to 10, 20, 30, 45, and 50, we observed the impact on the strategic choices of opinion leaders. The results, shown in Fig. 8, indicate that varying \(\:{R}_{2}\) does not influence the strategic choice of opinion leaders, who ultimately tend to adopt a strategy of “maintaining silence.“Opinion leaders, as individuals, have a psychological fear of isolation. This fear prompts them to continuously evaluate societal norms and views during reversed online public opinion events. Additionally, based on their knowledge and understanding, opinion leaders preliminarily judge these events. Therefore, during such times, opinion leaders do not simply “follow the crowd” and have their own views on current events; however, due to their fear of isolation, they choose not to express these views, thus maintaining a state of silence.

The impact of costs incurred by opinion leaders in clarifying facts on system evolution

Previous discussions have established that when online media resort to biased reporting, and opinion leaders voice their opinions actively, the truth can be clarified. At this time, opinion leaders will incur the costs of clarifying the facts. To examine the impact of the parameter \(\:{C}_{1}\) on the evolutionary system under the strategic choices of both parties, the simulation considers the equilibrium point C(1, 0) with parameters set as follows: \(\:{\text{R}}_{1}{=10,\text{R}}_{2}=10{,\text{R}}_{3}=10{,\text{R}}_{4}=5{,\text{R}}_{5}{=10,{\text{R}}_{6}=15,\text{C}}_{1}=10{,\text{C}}_{2}=5,{\text{C}}_{3}{=5,\text{C}}_{4}=5,{\text{L}}_{1}=5{,\text{L}}_{2}=20\). By sequentially varying the value of \(\:{\text{C}}_{1}\) to observe the impact of the cost \(\:{\text{C}}_{1}\) associated with clarifying facts on the strategic choices of opinion leaders, By varying the value of \(\:{\text{C}}_{1}\) to 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25, the simulation results are illustrated in Fig. 9.

It is evident that the magnitude of the value \(\:{C}_{1}\) does not influence the strategic choices of opinion leaders, who ultimately tend to adopt the “maintaining silence” strategy. The dynamics of reversed online public opinion events are often complex, making it challenging to fully uncover the truth within a short time frame. Opinion leaders may struggle to obtain comprehensive and accurate information necessary for effective clarification. If they speak prematurely in the absence of sufficient information, the content of their clarifications may be inaccurate, potentially exacerbating the chaos within the public opinion landscape. Consequently, to mitigate such risks, opinion leaders may refrain from incurring the cost \(\:{\text{C}}_{1}\) associated with clarification for the time being. Instead, they may choose to remain “silent” and await the emergence of more information. Furthermore, opinion leaders will also weigh the relationship between the costs of clarifying facts and the potential benefits they could derive. If actively clarifying facts does not yield economic returns, a significant enhancement in reputation, or other substantial benefits, they may likewise opt to remain “silent.”

Impact of government penalties for biased reporting by online media on system evolution

As discussed earlier, when online media choose a strategy of “biased reporting,” they face government penalties for not thoroughly investigating the facts before reporting on events. To explore the impact of government penalties \(\:{C}_{4}\) on system evolution, we refer again to equilibrium point B(0, 0) with the parameters: \(\:{R}_{1}{=5,\:R}_{2}=10{,R}_{3}{=5,R}_{4}=10{,R}_{5\:}=10,{R}_{6}=15,{C}_{1}=10,{C}_{2}=20,{C}_{3}=10,{C}_{4}=5,{L}_{1}=5,{L}_{2}=20\). By sequentially changing the value of \(\:{C}_{4}\) to 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25, we observed the influence of the severity of government penalties on the strategic choices of online media. The simulation results, depicted in Fig. 10, show that the severity of government penalties does not affect the strategic choices of online media. Ultimately, online media will tend to choose the “biased reporting” strategy.

In the context of reversed online public opinion events, certain media practitioners prioritize their traffic revenue, resulting in biased reporting on public opinion matters without conducting thorough verification and confirmation. This flawed value system perpetuates their biased reporting, even in the face of government penalties. Although the government has established corresponding punitive measures, challenges such as ineffective supervision and inadequate implementation often arise during the enforcement process. Some online media outlets may circumvent penalties through various tactics, while the limited human and material resources of regulatory authorities hinder their ability to promptly and effectively investigate and address all violations. Consequently, some online media pay little heed to government penalties and persist in their biased reporting.

Impact of traffic growth benefits from biased reporting by online media on system evolution

As previously established, online media that engage in biased reporting without thoroughly investigating the facts can reap benefits from increased traffic. To explore the impact of parameter \(\:{R}_{6}\) on system evolution, we refer to the equilibrium point C(1, 0) with the following parameters R1 = 10, R2 = 10, R3 =10, R4 = 5, R5 =10, R6 =15, C1 = 10, C2 = 5, C3 = 5, C4 = 5, L1 = 5, L2 = 20. We observed the influence of traffic growth benefits \(\:{R}_{6}\) on the strategic choices of online media by progressively altering the value of \(\:{R}_{6}\) to 5, 10,15, 20, and25, with simulation results shown in Fig. 11, show that the value of \(\:{R}_{6}\) does not affect the strategic choices of online media. Ultimately, online media will tend to choose the “biased reporting” strategy, moreover, the larger the value of \(\:{R}_{6}\) is, the faster online media tend towards the “biased reporting” strategy.

In reversed online public opinion events, biased reporting can rapidly capture the audience’s attention through unique perspectives or exaggerated expressions, thereby gaining a competitive advantage. Although the benefits of traffic growth may be modest, profits can still be derived from the scale effect resulting from long-term accumulation. Furthermore, when certain online media outlets acquire traffic through biased reporting, others are likely to imitate this approach. This imitative behavior contributes to the proliferation of biased reporting strategies within the industry. Even when some media organizations recognize the drawbacks of such practices, they often choose to conform due to the fear of falling behind in the competitive landscape.

Impact of the costs of government penalties and the benefits of traffic growth resulting from biased reporting by online media on the evolution of the system

In an effort to examine the combined influence of the costs of government penalties (\(\:{C}_{4}\)) and the benefits of traffic growth (\(\:{R}_{6}\)) on the evolution of systems, we referenced equilibrium point C(1,0) with parameters set as \(\:{\text{R}}_{1}{=10,\text{R}}_{2}=10{,\text{R}}_{3}=10{,\text{R}}_{4}=5{,\text{R}}_{5}{=10,{\text{R}}_{6}=15,\text{C}}_{1}=10{,\text{C}}_{2}=5,{\text{C}}_{3}{=5,\text{C}}_{4}=5,{\text{L}}_{1}=5{,\text{L}}_{2}=20\). By sequentially modifying the values of \(\:{C}_{4}\) and \(\:{R}_{6}\) to 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 respectively, we observed their impact on system evolution, as depicted in Fig. 12. It can be observed that lower costs of government penalties imposed on online media correlate with higher traffic revenue generated by these platforms. Conversely, as the costs of government penalties increase, traffic revenue tends to diminish. During the initial phase of an online public opinion event, online media frequently disseminate unverified and controversial information to satisfy audience curiosity and information needs. At this stage, the government may either be unaware of the actions taken by online media or may not perceive the situation as sufficiently serious, resulting in relatively low costs of government penalties. This regulatory gap allows online media to capitalize on substantial traffic revenue. However, as public opinion evolves and the event is marked by significant factual inaccuracies in media reports, the government is likely to intensify its oversight and enforcement efforts, ultimately leading to a decrease in traffic revenue for online media.

The impact of opinion leaders’ active voice on system evolution: costs of clarifying facts and the benefits of increased participation and sense of belonging

In an effort to examine the combined influence of the costs of clarifying facts (\(\:{C}_{1}\)) and the benefits of increased participation and sense of belonging (\(\:{R}_{1}\)) on the evolution of systems, we referenced equilibrium point C(1,0) with parameters set as \(\:{\text{R}}_{1}{=10,\text{R}}_{2}=10{,\text{R}}_{3}=10{,\text{R}}_{4}=5{,\text{R}}_{5}{=10,{\text{R}}_{6}=15,\text{C}}_{1}=10{,\text{C}}_{2}=5,{\text{C}}_{3}{=5,\text{C}}_{4}=5,{\text{L}}_{1}=5{,\text{L}}_{2}=20\).By sequentially modifying the values of \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{R}_{1}\) to 10, 15, 20, 25, and30 respectively, we observed their impact on system evolution, as depicted in Fig. 13. The findings indicate that the lower the costs incurred by opinion leaders in fact clarification, the higher the benefits in terms of participation and belongingness they receive; conversely, higher costs lead to diminished returns in these areas. For instance, during incidents of public opinion reversal, some opinion leaders spend minimal effort—merely a short amount of time combining simple graphics and text— to post clarifications on their social media accounts. Due to their professional influence and established follower base, these clarifications rapidly garner significant engagement in the form of likes, comments, and shares. In such scenarios, opinion leaders experience a pronounced increase in participation and a sense of belonging in a short period. However, to sustain this sense of engagement and belonging, opinion leaders might invest considerable time in clarifying facts. The prolonged effort can result in slower growth in engagement metrics such as likes, comments, and shares, leading to a marked decrease in the rate of accruing benefits from participation and sense of belonging.

Conclusion

This paper analyzes the interplay between online media and opinion leaders based on the evolutionary mechanisms of a dual-helix structure. It constructs an evolutionary game model involving both parties, facilitating strategic simulations and analyses of strategy evolution. The primary conclusions and recommendations are as follows:

-

1.

The size of the credibility gains significantly influences the strategic choices of opinion leaders. Larger credibility gains encourage opinion leaders to actively voice their opinions, whereas smaller gains incline them towards silence. Consequently, governments should prioritize the influence of opinion leaders by offering them greater support and emphasizing bidirectional communication. This would encourage the publication of objective, accurate, and positive statements on online platforms, steering public opinion in a favorable direction.

-

2.

The traffic growth benefits realized by online media do not significantly influence their strategic decisions. In situations where online media experience relatively modest traffic growth benefits from biased reporting and rely on scale effects for long-term profitability, government agencies can employ technological solutions such as big data and artificial intelligence to enforce appropriate penalties on the relevant online media accounts. These penalties may include traffic restrictions or account suspensions. Conversely, in cases where online media achieve substantial traffic growth benefits from biased reporting, government agencies can establish substantial fine standards, ensuring that the fines are significantly greater than the traffic growth benefits derived from biased reporting. This approach can create an effective deterrent.

-

3.

The severity of government penalties and the revenue generated from traffic by online media significantly influence the strategic decisions of both parties. Specifically, as the costs of government penalties incurred by online media decrease, the traffic revenue they generate tends to increase. Conversely, as the costs of government penalties rise, traffic revenue diminishes. This indicates that for influential online media that achieve high traffic revenue through biased reporting, government authorities can implement stricter measures, including economic penalties and business restrictions. In contrast, for smaller-scale media with less severe violations, relatively lighter penalties that still serve as effective warnings can be imposed, thereby fostering a rational and harmonious online environment.

Building on the evolutionary game model under the dual-helix structure for reversed online public opinion presented in this paper, future research could explore how public opinion specifically influences individual perspectives and behaviors, aiming for more profound investigations into this dynamic.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, B. & &Wang, X. Research on the evolution mechanism and governance countermeasures of online public opinion based on the silence spiral theory. J. Intell. Explor. 13(10), 8–15 (2020).

Ke, L. Analysis of theanti-silence spiral phenomenon in the new media environment. Youth Journal. 10(22), 33–34 (2021).

Song, L. A brief analysis of the phenomenon of positive and negative silence spiral in the network environment. North. Media Res. 23(05), 72–76 (2023).

Tian, S. et al. Research on the evolution of public opinion reversal considering intelligent recommendation algorithms—based on the perspective of information ecology. Inform. Sci. 41(08), 37–45 (2023).

Zhao, P. & Liu Y. Study on the silence spiral and anti-silence spiralin online public opinion in the new media era: the case of the Luo Er Incident. J. Armed Police Acad. 33(03), 10–13 (2017).

Li, Y. & Zheng, L. Anti-silence spiral in public opinion reversal—analysis from the perspective of audience psychology. Youth Journal. 20(05), 50–52 (2022).

Gao, X. & Xie, W. From passive silence to active interaction: the silent double helix. Effect new. Media Environ. Press. Circles. 20(09), 43–50 (2014).

Wang, L., Geng, Y., Wang, F., Dong, X. & Pan, M. Study on the impact mechanism of online public opinion on university students’ online speech from the perspective of conformity. Front. Social Sci. 13(2), 923–933 (2024).

Mu, G., Liao, Z., Li, J., Qin, N. & Yang, Z. IPSO-LSTM hybrid model for predicting online public opinion trends in emergencies. PLoS ONE. 18(10), 1–17 (2023).

Li, J. & Pan, X. Construction and simulation of a SEIR transmission model for social media public opinion with integrated themes. Intell. Comput. Appl. 14(4), 34–44 (2024).

Christen, C. T. & Hubert, K. E. Media reach, media influence? The effects of local, national, and internet news on public opinion inferences. Journalism Mass. Communication Q. 84(2), 315–334 (2007).

Tang, J. & Bao, J. Research on public opinion dissemination control of reversal events based on the improved SIR model. J. Syst. Simul. 34(11), 2406–2415 (2022).

Qi, K., Peng, C., Yang, Z. & Li, B. Research on network public opinion governance of sudden crisis events based on SEIR evolutionary game model. Mod. Inform. 42(04), 120–133 (2022).

Gao, G., Zhang, Y. & Ding, Y. Study on the evolution mechanism and influence of online public opinion based on system dynamics. Inform. Theory Pract. 39(12), 39–45 (2016).

Wang, M., Yu, L. & Hu, H. Research on the evolution of public opinion reversal based on behavioral intention and the reliability of reversal information. J. Intell. 38(04), 125–131 (2019).

Khalil, N. & Toral R. The noisy voter model under the influence of contrarians.Physica. Stat. Mech. its Appl. 515(2), 81–92 (2019).

Deffuant, G., Neau, D., Amblard, F. & Weisbuch, G. Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. Adv. Complex. Syst. 3(11), 87–98 (2000).

Chen, Y., Chen, X., Lv, Y., Han, T. & Xu, Y. Research on microblog public opinion reversal based on the improved Hegselmann-Krause model. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 43(01), 82–89 (2020).

Liu, Q. & &Xiao, R. Research on online public opinion reversal based on opinion leaders from the perspective of opinion dynamics. Complex. Syst. Complex. Sci. 16(01), 1–13 (2019).

Chica, M., Perc, M. & Santos, F. C. Success-driven opinion formation determines social tensions. iScience 27(3), 235–254 (2024).

Di Mare, A. & Latora, V. Opinion formation models based on game theory. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C. 18(09), 1377–1395 (2006).

Sznajd-Weron, K. &Sznajd, J. Opinion evolution in closed community. HSC Res. Rep. 11(06), 1157–1165 (2000).

Li, Z., Chen, X. & Yang, H. &Szolnoki A.Game-theoretical approach for opinion dynamics on. Soc. Netw. Chaos. 32(7), 073–117 (2022).

Kawakatsu, M., Lelkes, Y., Levin, S. A. & Tarnita, C. E. Interindividual cooperation mediated by partisanship complicates Madison’s cure for mischiefs of faction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118(50), 56–81 (2021).

Huang, C., Hou, Y. & Han, W. Coevolution of consensus and cooperation in evolutionary hegselmann–krause dilemma with the cooperation cost. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 168(67), 113–215 (2023).

Chen, T., Wang, Y., ,Yang, J. & Cong, G. Modeling public opinion reversal process with the considerations of external intervention information and individual internal characteristics. Healthcare 8(2), 160–168 (2020).

Zhang, L., Yi, S. & Wang, H. Path study of sudden incident online public opinion reversal from the perspective of symbiotic theory—based on fsQCA qualitative comparative analysis. Inform. Sci. 42(06), 74–82 (2024).

Han, X. Analysis of the causes and countermeasures of online public opinion reversal phenomenon: the case of rescue of a girl from a dog’s mouth was a lie. Western J. (News Communication). 16(04), 24–28 (2016).

Peng, G. & Cheng, X. Research on the generation mechanism of public opinion heat of reversed news based on social combustion theory. Inform. Sci. 41(01), 80–85 (2023).

Wang, G., Min, C. & Zhong, S. Study of the reversal phenomenon of netizens’ public opinion on hot issues from the perspective of agenda-setting theory—content analysis based on the Chengdu female driver assaulted for changing lanes incident. Inform. Magazine. 34(09), 111–117 (2015).

Huang, F. Research on the changes of the silence spiral theory and the application of network public opinion in the new media era. Netw. Secur. Technol. Application. 20(12), 161–162 (2023).

Cui, X. Study of the anti-silence spiral in the new media environment. New. Media Res. 4(03), 17–18 (2018).

Shi, C. & Zhou, H. Analysis of the anti-silence spiral phenomenon in the generation of moral public opinion in a virtual context. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Social Sci. Edition). 25(02), 76–80 (2017).

Chen, L., Guo, Q. & Chen, M. Research on the anti-silence spiral phenomenon and network public opinion guidance in the new media era. View Publishing. 19(22), 83–85 (2019).

Wang, H. The generation mechanism and governance of police-related public opinion reversal: the case of the qing’an shooting incident. J. Hubei Police Officer Coll. 30(03), 36–46 (2017).

Hoffmann, C. & Lutz, C. Silence spiral 2.0: political self-censorship among young facebook users. Social Media Stud. 22(5), 795–812 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by several funding sources, including the Youth Project of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region Social Science Fund, which focuses on the “Research on the Evolution Mechanism and Countermeasures of Reversal Online Public Opinion Based on Big Data” (Project No.: 2023CTQ115). Additionally, funding was provided by the School-level Fund Projects titled “Research on the Evolution Process of Public Opinion Reversal Based on Double Helix Structure” (Project No.: ZQ202307), “Research on the Evolution Mechanism and Countermeasures of Online Public Opinion Reversal in the Context of Big Data”(Project No.:2023YB021) and “Research on the Implementation Path of All-media Data Assetization” (Project No.: 2024PY010), and Science and Technology Research Project of the Education Department of Jilin Province titled “Research on Event Causality Extraction Based on Text Data Augmentation, Pretraining and Reinforcement Learning” (Project No.: JJKH20250758KJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li Hairong proposed the research ideas, conducted experiments, and completed the writing of the first draft. Wang Nan proofread the first draft.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Wang, N. Research on the evolutionary game of reversed online public opinion based on the dual-helix structure mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 5445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89169-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89169-9