Abstract

Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) offer an environmentally friendly and sustainable approach to combat pathogens and enhance crop production. The biocontrol activity of PGPR depends on their ability to colonize plant roots and synthesize antimicrobial compounds that inhibit pathogens. However, the regulatory mechanisms underlying these processes remain unclear. In this study, we isolated and characterized Bacillus velezensis 118, a soil isolate that exhibits potent biocontrol activity against Fusarium wilt of banana. Deletion of sigX, encoding an extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor previously implicated in controlling biofilm architecture in B. subtilis, reduced biocontrol efficacy. The B. velezensis 118 sigX mutant displayed reduced biofilm formation but had only a minor defect in swarming motility and a negligible impact on lipopeptide production. These findings highlight the importance of regulatory processes important for root colonization in the effectiveness of Bacillus spp. as biocontrol agents against phytopathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rise in global population and dramatic changes in climate, ensuring food security has become an increasingly pressing issue1. This has led to heightened pressure to meet growing food demand, resulting in extensive use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers to boost agricultural productivity2. However, the massive application of agrochemicals can disrupt soil salinity levels and leave toxic residues in agricultural produce, leading to the frequent occurrence of soil-borne diseases. Soil amendment with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) is widely regarded as a promising and sustainable strategy for crop disease management3. Numerous strains from the Bacillus genus have figured prominently in efforts to use PGPR in agricultural settings4,5.

Fusarium wilt, caused by the soil-borne fungus F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc), and Bacterial wilt, caused by Ralstonia solanacearum (Rs), rank among the most devastating plant diseases6,7. In the rhizosphere of plants, soil-borne pathogens coexist with beneficial microorganisms such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR)8. PGPR can suppress soil-borne pathogens through competition for essential nutrients and the production of antagonistic compounds9.

B. subtilis and B. velezensis represent a growing class of PGPR widely recognized for their biocontrol activity against plant diseases10,11. These bacteria form biofilms on plant roots and produce bioactive compounds that competitively exclude pathogens12. The model organism for B. velezensis is strain FZB42 (formerly B. amyloquefaciens FZB42)13. This and numerous related Bacillus spp. have been isolated from soils and shown to be effective biocontrol agents in a variety of settings.

Biocontrol activity depends on the ability of the bacteria amended to the soil to colonize plant roots and produce potent antimicrobial compounds that inhibit the growth of bacterial and plant pathogens. Prior studies have defined the transcriptional responses of Bacilli to root exudates14,15, demonstrated the essential role of motility and biofilm formation in root colonization16,17,18, and identified the specific antimicrobial secondary metabolites that mediate disease suppression10,19,20,21.

The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors serve as important transcriptional regulators in the Bacilli, responding to diverse stresses22,23. Both the type strain B. subtilis 168 and B. subtilis 3610 (an undomesticated relative of B. subtilis 16824) encode seven ECF σ factors (σM, σW, σX, σV, σylaC, σZ and σY) important in helping cells adapt to new environments22,25,26. A triple mutant lacking three σ factors (sigM sigW sigX) has striking defects in colony morphology and pellicle formation at 22 °C26. Even the sigX single mutant displays strong defects in biofilm formation when tested at 37 °C27. The ECF sigma factor σX is important for biofilm formation because it controls expression of Abh, a positive regulator of biofilm formation28. B. velezensis FZB42 possesses five ECF σ factors (σM, σW, σX, σV, and σylaC)29, but their contributions to the transcriptome changes that accompany biofilm formation30 are not yet known.

B. velezensis FZB42 was isolated from plant-pathogen-infested soil from a sugar beet field in Brandenburg, Germany31. Products based on this strain include RhizoVital® (ABiTEP, GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and Taegro® 2 (Novozymes), and many related species have also been commercialized32. Prior work has demonstrated that the successful application of PGPR benefits from the use of indigenous isolates adapted to the ambient temperature and soil types. For example, isolates indigenous to the Vietnamese highlands were effective in presented disease in that environment33, and cold-adapted Bacilli from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau were effective in promoting growth of winter wheat34.

Here, we isolate and characterize B. velezensis 118, a strain indigenous to Guangzhou, a city in South China with a south Asian tropical monsoon oceanic climate and latisolic red soils. This strain exhibits robust biocontrol activity against the banana fungal pathogen Foc and the bacterial wilt pathogen Rs. We further demonstrate that the ECF sigma factor σX is required for effective biocontrol against both Foc and Rs under natural environmental conditions, and this is correlated with an ability to form robust biofilms. This study highlights the role of σX in enhancing biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis.

Materials and methods

Isolation of antagonistic Bacillus species

Samples were collected from the rhizosphere soil of banana plants in Guangzhou, China (23˚ 08’ N 113˚ 16’ E). Bacillus spp. were isolated as reported previously35. Briefly, the soil samples (10 g each) were shaken in 90 mL of sterilized water for 30 min, heated for 30 min at 80 °C, serially diluted, and then spread over lysogeny broth (LB) plates. Single bacterial colonies were streaked onto fresh LB plates after 48 h of incubation at 30 °C. Frozen stocks of the purified colonies were prepared using 15% glycerol and kept at -80 °C for further study. All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Antifungal activity test

We performed two assays, a plate confrontation assay and a spot-on-lawn assay, to test activity of the isolates (strain 118) and derived mutants against common fungal pathogens including Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense 4 strain XJZ2 (Foc, GenBank accession number JX090598) Magnaporthe oryzae B157 (GenBank accession number AXDJ01000000)36, Peronophythora litchii Shs3 (GenBank accession number PCFV01000001), Rhizoctorzia solani AG1-IA GD-118 (GenBank accession number KB317696 AFRT01000000), and Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cucumerinum (isolated from cucumerium rhizosphere, no accession number available yet).

The plate confrontation assay was conducted as described previously19. Briefly, the four fungi except Peronophythora oryzae B157 were cultivated on potato-dextrose-agar plates (PDA, 20% potato infusion, 2% dextrose, and 1.5% agar), while Peronophythora oryzae B157 was cultivated on carrot juice agar plates (CA, 20% carrot and 1.5% agar) at 30 °C. After 5 days of incubation, a 5-mm-diameter block of mycelium agar containing fungi (Rhizoctorzia solani AG1-IA GD-118, Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cucumerinum and Foc) was cut and placed at the center of a fresh PDA plate. After one day of incubation, a 5-mm-diameter well was created 2.5 cm away from the center of each plate, and 50 µL of B. velezensis 118 cells (OD600 ~ 0.4; ~2 × 108 cfu/mL) grown in LB medium was added into each well. Additionally, the mycelium agar of the slow-growing fungi (Magnaporthe oryzae B157 and Peronophythora litchii Shs3), was cut and placed 2.5 cm away from the center of a fresh PDA or CA plate. After one day of incubation, a 5-mm-diameter well was made in the center of each plate, and 50 µL of B. velezensis 118 (OD600 ~ 0.4) grown in LB medium was added into each well. Antifungal activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone (the distance between the mycelium and the bacterial colony) after 7 days of incubation at 30 °C.

The spot-on-lawn assay was conducted as described previously19. This assay is more sensitive compared to the plate confrontation assay and requires only one day of incubation instead of seven days, fungal hyphae of Foc were streaked and inoculated with 5 mL of PDA broth. After two days of incubation at 30 °C with shaking at 180 rpm, 50 µL of the fungal culture was re-inoculated into 5 ml of fresh PDA broth and incubated for additional 12 h. The culture was then filtered using a cheesecloth to remove hyphae, and 50 µL of the resulting spore suspension was mixed with 4 mL of 0.7% soft PDA agar and poured directly onto a PDA plate (1.5% agar). After drying the plates for 50 min, a 5-mm-diameter well was created in the center of each plate, and 50 µL of B. velezensis 118 cells grown in LB medium to OD600 ~ 0.4, was added into each well. Antifungal activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone (in mm) after 24 h of incubation at 30 °C. The experiments were performed at least three times with four biological replicates each time.

Antibacterial activity test

The antibacterial activity of the isolates and their derived mutants against R. solanacearum GMI1000 was evaluated using an optimized spot-on-lawn assay as described previously19. R. solanacearum cells (200 µL; OD600 ~ 0.4), grown in Casamino Acid-Peptone-Glucose (CPG, 0.1% peptone, 0.01% casamino acids, 0.05% glucose), was mixed with 4 mL of 0.7% CPG soft agar and directly poured onto a CPG plate (1.5% agar). After drying the plates for 50 min, a 5-mm-diameter well was made in the center of each plate, and 50 µL of each Bacillus strain (OD600 ~ 0.4) grown in LB medium was added to each well. Antagonistic activity was evaluated by the size of the inhibition zone after 24 h incubation at 30 °C. The experiments were performed at least three times with four biological replicates each time.

Construction of mutants

In initial studies, we determined that 118 is sensitive to spectinomycin (Spc; 100 µg ml− 1), kanamycin (Kan; 15 µg ml− 1), chloramphenicol (Cat; 10 µg ml− 1), tetracycline (Tet; 5 µg ml− 1), and macrolide lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS; contains 1 µg ml− 1 erythromycin and 25 µg ml− 1 lincomycin) antibiotics. The sigM::erm, sigX::erm, sigW::cat, sigV::kan and ylaC::cat single mutants in the 118 background (Supplementary Table S1) were generated by replacing the coding region with an antibiotic resistance cassette using long flanking homology PCR (LFH-PCR) and oligonucleotide primers (Supplementary Table S2) as previously described37. DNA was used to transform cells grown in modified competence (MC) medium (100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7], 3 mM trisodium citrate, 3 mM MgSO4, 2% glucose, 22 µg/mL ferric ammonium citrate, 50 µg/ml tryptophan, 0.1% casein lysate, 0.2% potassium glutamate)38.

The sigX::erm mutant (MLSR) in the B. subtilis 3610 background was constructed using sigX::erm from the Bacillus Knockout Erythromycin (BKE) collection39. The sigX PspacsigX complemented strain in the 3610 background was constructed using vector pPL82 and PCR products from B. velezensis 118 chromosomal DNA. pPL82 contains a cat resistance cassette, a multiple cloning site downstream of the Pspac(hy) promoter and the lacI gene between the upstream and downstream fragments of the amyE gene40. All constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA from the HB19118 isolate was prepared using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen Cat # 69506) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole genome sequencing was performed commercially by Plasmidsaurus using a hybrid system of Oxford Nanopore and Illumina technologies with custom assembly, analysis, and annotation. Oxford Nanopore technology was used to determine the initial sequence from 386,948 long reads, with 650,507,349 bp sequenced and 167x raw coverage. The sequence was assembled into two contigs (3,882,587 and 5,922 bp) with 99x coverage. Subsequently, Illumina sequence technologies short reads were used to polish the sequence data. The DNA sequence was deposited in NCBI under accession number PRJNA1201100.

Whole genome sequence analyses

Whole genome-based taxonomy was done using the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS) (https://tygs.dsmz.de) for genome-based taxonomy41,42. The TYGS determines the closest type strain genomes based on intergenomic relatedness and 16 S rDNA analysis, and subsequently calculates precise distances using Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny. The phylogenomic inference was determined from the intergenomic distances to the closest type strains with 100 pseudo-bootstrap replicates each, and the resulting tree was rooted at the midpoint. The resulting phylogenomic tree was edited using iTOL server43. Genome sequences of the closest type strains, as identified by the TYGS, were downloaded from NCBI, and the average nucleotide identity to B. velezensis HB19118 was calculated using FastANI44 as implemented in the KBase webserver45. Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters were predicted using antiSMASH46 in WGS data of B. velezensis 118 and B. velezensis FZB42 (GenBank accession number CP000560.2) was used for comparison.

Swarming and swimming motility assays

Swimming and swarming motility of B. velezensis 118, B. subtilis 3610, and their derived mutants were tested using standard protocols19 with minor modifications. LBGM plates containing 0.7% (for swarming) or 0.3% agar (for swimming) were dried in a laminar flow hood for 30 min and then 5 µL of LB precultures (OD600 ~ 0.4) were spotted on the center of each plate. The plates were dried for 15 min and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The experiments were performed three times with four biological replicates each time.

Biofilm formation assay

The biofilm formation assays were conducted as described previously19. For colony morphology analysis, 3 µL of LB precultures (OD600 ~ 0.4) were spotted onto LBGM (LB plus 1% [vol/vol] glycerol and 0.1 mM MnSO4)47 agar plates, which had been dried for 30 min in a laminar airflow hood prior to spotting. The plates were then incubated at 30 °C for up to 5 d. To monitor pellicle formation, 10 µL of LB precultures (OD600 ~ 0.4) were inoculated into 2.5 mL of LBGM medium in a 24 well plate and incubated at 30 °C for up to 5 d. The pellicle was harvested from the well using a 1 mL pipette tip, placed into a 1 mL centrifuge tube, and then dried under vacuum for 1 h prior to weighing.

Plant pot experiments

The biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis 118 against banana Fusarium wilt was determined under greenhouse conditions as described previously19. Micropropagated Cavendish banana seedling ‘Brazilian’, the F. oxysporum (Foc) susceptible variety, were used for the pot experiments. In these pot experiments, the average temperature was 24 °C, humidity was maintained at 75%, and the light/dark cycle consisted of 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. Each pot contained 1.5 kg soil (pH 4.7, organic matter 22.7 g kg− 1, total nitrogen 0.79 g kg− 1, alkaline hydrolysis nitrogen 118.4 mg kg− 1, available phosphorus 1.61 mg kg− 1, and available potassium 18.6 mg kg− 1). Two control groups were included as follows: CK1 (no Foc), banana seedlings with four or five leaves and approximately 20 cm in height were directly implanted into pots; CK2 (Foc, GenBank accession number JX090598), the roots of the banana seedlings were immersed in Foc (~ 106cfu mL− 1) for 30 min prior to planting. In the treated group (Foc + 118), the roots of the banana seedlings were firstly immersed in the Foc suspension for 30 min, then planted into pots. Two days later, the plants were watered with 50 mL of a cell suspension of 118 (OD600 ~ 1.0) around the roots, resulting in a final concentration of ~ 106 cells per gram of soil. The wilt severity index (WSI) was recorded using the following index48: 1 = healthy, 2 = slight chlorosis and wilting with no petiole buckling; 3 = moderate chlorosis and wilting with some petiole buckling and/or splitting of leaf bases; 4 = severe chlorosis, wilting, petiole buckling and dwarfing of the newly emerged leaf; and 5 = dead. Wilt incidence (WI) of the banana plants was monitored every 3 days after transplantation. Wilt incidence (WI) of the banana plants was monitored every 3 days after transplantation. The experiments were conducted at least three times with 30 banana plants per groups. To evaluate the contribution of sigX in biocontrol efficacy against banana Fusarium wilt, four groups were included: CK1 (No Foc), CK2 (Foc), Foc + B. velezensis 118, and Foc + B. velezensis 118 sigX::erm.

The biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis 118 and its derived sigX::erm mutant against tomato bacterial wilt was determined under greenhouse conditions using a similar protocol as described previously19. Four treatments were included as follows: control 1 (CK1, no Rs), control 2 (CK2, only inoculated with Rs), WT (Rs + 118), and sigX (Rs + sigX::erm mutant). Tomato seeds (Lycopersicon esculentum Miller) were surface-sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 s, followed by 5% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, and then washed three times with sterile water for 15 min each time. The sterilized seeds were planted in pots containing non-sterile local soil, and the pots were then placed in an artificial climate chamber (PQX-450R-22HM). After one month, the tomato seedlings were transplanted into new pots containing 1.5 kg of the non-sterile local soil. Seven days after transplanting, the soil used for 118 or sigX::erm treatment was drenched with 50 ml of bacterial suspension of 118 or sigX mutant strain (~ 106 cells per g of soil). The bacterial suspension was prepared using cell pellets harvested from 50 ml of LB cell culture (OD600 ~ 1.0) by centrifugation. Two days later, each pot was drenched with 30 ml of R. solanacearum cell suspension, which was obtained from 30 ml of CPG cell culture (OD600 ~ 1.0) by centrifugation and resuspension in sterile water, resulting in ~ 107 cells per g of soil. The pots were then placed back into the artificial climate chamber, set to a 16-hour day/8-hour night cycle with temperatures of 30 °C during the day and 28 °C at night, and relative humidity ranging from 65 to 80%. Each treatment group included 24 tomato plants with three replicates. The wilt incidence (WI) was calculated on the 30th day after transplanting. The wilt severity index (WSI) was recorded as follows: 0 = no wilt symptoms, 1 = wilt symptoms on 1–25% of the leaves, 2 = wilt symptoms on 26–50% of the leaves, 3 = wilt symptoms on 51–75% of the leaves, and 4 = wilt symptoms on more than 76% of the leaves.

Wilt incidence and biocontrol efficacy of the two pot experiments tomato bacterial wilt and banana Fusarium wilt were calculated according to the following formula48,49:

Root colonization assay

To investigate the contribution of sigX to root colonization, root colonization experiments were conducted as described previously16. Briefly, Arabidopsis seeds were surface sterilized with 75% ethanol followed by 0.3% sodium hypochlorite (vol/vol) and germinated on 0.5x MS (Murashige and Skoog50) agar plates containing 0.7% agar. Seedlings were ready for use after 6 days of incubation in a plant growth chamber (25 °C with a 16 h light /8 h dark cycle). One µL of LB preculture (OD600 ~ 0.4) and one seedling were added to 200 µL LBGM in a 96-well plate. Plates were incubated at 25 °C for 3 h, followed by shaking at 100 rpm in a greenhouse at 25 °C for 0, 12, 24, or 48 h. Roots were then washed using 0.1x PBS buffer and imaged by a Leica SP5 confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 509 nm. The experiments were performed three times.

Cell recovery counting

The cell recovery counting assay was performed as described previously16. After being washed four times in sterile water, the preprocessed roots (one-cm root segments) were placed in an Eppendorf tube containing 1 mL of sterile water. After adding two glass beads to each tube, each sample was vortexed for 5 min. The resulting suspension was serially diluted with distilled water, and 100 µL of the cell suspension from dilutions (10− 1, 10− 2, 10− 3, or 10− 4) was plated onto LB agar plates. The plates were then incubated for 7 h at 37 °C. Colony forming units (CFU) per mm root were calculated. The experiment was repeated three times with ten root samples per replicate.

Lipopeptide (LP) extraction from the isolated strains

To understand the impact of pathogen presence on LP production of Bacillus isolates, LPs were extracted from the inhibition zone as described previously19. Two hundred µL of R. solanacearum cell culture (OD600 ~ 0.4) in Casamino acid-Peptone-Glucose (CPG) medium (0.1% peptone, 0.01% casamino acids, 0.05% glucose) was combined with 4 mL of 0.7% CPG soft agar, mixed thoroughly by vortexing, and then poured onto a CPG plate containing 1.5% agar. Plates were dried for 50 min and a 5-mm-diameter well was made at the center of each plate, and 50 µL of Bacillus isolates (B. velezensis 118 or B. subtilis 3610 strains) grown in LB medium (OD600 ~ 0.4) was added into each well. After the inhibition zone became evident with 24 h incubation at 30 °C, a 300 mg agar sample was harvested from the inhibition zone, mixed with 1 ml of 1:1 acetonitrile/water mixture, and sonicated for 30 s, and then subjected to centrifugation and filtration. The supernatant was collected from acetonitrile/water extract. LPs were also extracted from the control plates using the same procedure, but without R. solanacearum in the top soft agar layer. An agar sample (300 mg) was collected around the well (2–4 mm). The experiments were performed three times with samples pooled from four biological replicates.

Identification and quantification of LPs by UPLC–MS

The acetonitrile/water extracts were analyzed by reverse phase Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole MS (UPLC-MS) as described previously19 (Waters, Acquity, XEVO-TQD). The identification of lipopeptide compounds was achieved using their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and their quantification was performed using standard curves derived from commercial LP standards (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C and a gradient elution with (A) acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid) and (B) water (containing 0.1% formic acid) was used. The gradient program was used as follows: 0–0.5 min, 40% A; 0.5–3.5 min, 40–80% A; 3.5–4.0 min, 80% A; 4.0–6.0 min, 80–95% A; 6.0–7.0 min, 95–98% A. The flow rate was set at 0.4 mL min− 1. The electrospray Ionization (ESI) source was set in positive ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3.26 kV, and the source temperature was maintained at 150 °C. The nitrogen flow rate was 600 L h− 1 and the argon flow rate was 50 L h− 1.

Results

Bacillus velezensis 118 exhibits strong antagonistic activity against Foc

To isolate PGPR effective in a sub-tropical climate zone, we collected rhizosphere soil from healthy banana plants at a local farm in Guangzhou, a city in South China. More than 60 Bacillus strains were isolated. The isolate designated as strain 118 (HB19118) exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect against the banana fungal pathogen F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc) as assayed using a spot-on-lawn assay on Potato-Dextrose-Agar (PDA) plates (Fig. 1A). Compared to unexposed Foc, exposure to strain 118 resulted in altered fungal morphology with swollen and distended Foc spores (Fig. 1B) and hyphae (Fig. 1C), particularly when isolated proximal to the zone of growth inhibition. Whole genome sequencing of B. velezensis 118 (accession PRJNA1201100) reveals that it clusters closely with the well-characterized B. velezensis FZB4213 type strain and related B. velezensis isolates14,15 (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Table S3).

B. velezensis 118 exhibits strong antifungal activities against Foc in vitro. (A) To evaluate the inhibitory activity of B. velezensis 118 (HB19118) against Foc, a spot-on lawn assay was performed. The clearance zone was measured after 24 h at 30 °C (8.8 ± 0.5 mm, mean ± SD with n = 3). Foc alone (CK) without the treatment of B. velezensis118 cells serves as a control. (B) Representative images showing distorted and enlarged Foc spores recovered from the periphery of the inhibition zone (left panel) and healthy spores from CK (right panel). (C) Representative images showing swollen and deformed Foc hyphae recovered from the periphery of the inhibition zone (left panel) and healthy hyphae from CK (right panel). Scale bar is 50 μm. (D) Genome-based phylogeny of B. velezensis 118. Phylogenomic analysis was done using the Type Strain Genome Server41,42, and the phylogeny was inferred from WGS based on 100 bootstrap replicates (bootstrap values ≥ 60 are shown in blue on the corresponding branch). Bar graphs on the right are the average nucleotide identities to the B. velezensis 118 genome sequence as calculated using FastANI44.

To further evaluate the antagonistic capability of B. velezensis 118, we conducted a plate confrontation assay against several common fungal plant pathogens. B. velezensis 118 significantly inhibited the growth of Magnaporthe oryzae, Peronophythora litchii, Rhizoctorzia solani, Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cucumerinum (Supplementary figure S1).

B. velezensis 118 is an effective biocontrol agent for banana Fusarium wilt

To test whether B. velezensis 118 could effectively control banana Fusarium wilt, we carried out pot experiments under greenhouse settings using micropropagated Cavendish banana seedlings of the ‘Brazilian’ variety that are susceptible to Foc. Following treatment with B. velezensis 118, the wilt incidence (WI) was reduced by nearly two-fold relative to the untreated control plants (CK2), which exhibited a disease incidence (DI) of 89% (Fig. 2A and E). Consistent with this disease suppression, plants treated with both B. velezensis 118 and Foc displayed a restoration of leaf number (Fig. 2B), plant height (Fig. 2C), and plant biomass (Fig. 2D) to levels significantly higher than the control Foc-only exposed plants (CK2). Bacillus biocontrol agents can both protect plants against pathogens and in some cases improve growth by production of plant hormones51,52. In this case, the plants in the 118-treated group (Foc + 118) were comparable to the healthy, uninfected control plants (CK1), with no obvious growth stimulation. Furthermore, treatment with B. velezensis 118 led to restoration of the rhizosphere microbial community, with increased levels of bacteria and actinomycetes, and a significant reduction in fungi, relative to the Foc-only treated plants (Supplementary figure S2). Together, these results demonstrate that B. velezensis 118 effectively suppresses banana Fusarium wilt and facilitates the restoration of soil microbe ecological balance thereby mitigating the damage caused by Foc infection.

B. velezensis 118 exhibits potent antifungal activities against Foc in vivo. (A) The biocontrol ability of 118 to suppress banana Fusarium wilt was evaluated in pot experiments. Three groups were included: CK1 (no Foc): uninfected banana seedlings were directly planted into pots; CK2 (Foc): infected with Foc; and Foc + 118, inoculated with both Foc and 118. (B) The number of banana leaves per plant and (C) plant height were monitored for 30 days after transplantation. Data represent the mean values ± SD (n = 30, 95% confidence intervals). (D) The dry weight of each plant was quantified 30 d after transplantation. Significant differences between the two infected groups (CK2 and Foc + 118) were determined by a two-tailed t-test, **P < 0.01, ns, not significant. (E) Representative photographs showed the biocontrol effect of 118 on suppressing banana Fusarium wilt in the pot experiments. Photos were taken 20 d after transplantation.

Deletion of sigX impairs biofilm development in B. velezensis and B. subtilis

The ability of PGPR to reduce the impact of phytopathogen is associated with a strong potential for biofilm formation, which contributes to efficient colonization of the root surface53,54. Assays for biofilm formation are well established for Bacillus isolates, and include analysis of the complex morphology of colonies growing on agar plates28,55 and of the pellicles that form at the interface between a nutrient medium and the air in static cultures56,57. We evaluated the biofilm formation capability of B. velezensis 118 by monitoring pellicle mass. B. velezensis 118 exhibited higher biofilm production than other biofilm-producing isolates such as B. velezensis FZB42, Y619, F719, and B. subtilis 3610 (Supplementary figure S3).

The regulatory pathways involved in biofilm formation have been investigated in detail in B. subtilis 361055,58,59,60. Since the transition from planktonic growth to a biofilm is a major life-style transition, we hypothesized that alternative sigma factors might play a role in this process.

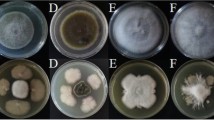

B. velezensis encodes five ECF sigma factors (σM, σX, σW, σV, and σYlaC)29. To assess the role of each σ factor to biofilm formation, we constructed deletion mutants of each ECF sigma factor in B. velezensis 118. We then examined the impact of these deletions on pellicle formation at the air-liquid interface in liquid culture. B. velezensis 118 WT exhibited densely packed, uniformly structured pellicle with characteristic wrinkled patterns (Fig. 3A). Four single mutants (sigM::erm, sigW::cat, sigV::kan, and ylaC::cat) displayed comparable levels of biofilm development. However, the sigX::erm mutant showed a much thinner and disorganized pellicle structure, with less wrinkling and large gaps (Fig. 3A). We then monitored the colony morphology on solid agar plates. Compared to the wild-type B. velezensis 118, the sigX::erm mutant exhibited a disrupted structure with less uniformity and potential central degradation (Fig. 3B). In contrast, three other mutants (sigM::erm, sigW::cat, and sigV::kan) had structured biofilms with rugged edges similar to WT, and the ylaC::cat mutant displayed a wide and dispersed halo at the margin (Fig. 3B).

Contribution of σ factor to biofilm formation of B. velezensis 118. Representative images show pellicle structure in LBGM medium (A) and colony architecture morphology on LBGM plates (B) after 24 h incubation at 30 °C. The strains tested include B. velezensis 118 (WT) and its derived mutants: sigM::erm, sigX::erm, sigW::cat, sigV::kan, and ylaC::cat. Scale bar, 5 mm.

To further evaluate the effects of sigX deletion on biofilm development, we monitored pellicle formation and colony morphology over five days. The sigX::erm mutant failed to develop a mature and complex pellicle structure by day 5 compared to WT (Fig. 4A). While WT developed well-defined colonies with a rugged and intricate pattern over time, sigX::erm colonies remained smaller and less organized, with parts of the pellicle petal structure missing even after 5 days (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the sigX::erm mutant produced significantly lower biofilm mass across all time points (Fig. 4C).

σX contributes to biofilm formation in B. velezensis 118. Representative images show the pellicle formation in LBGM medium (A) and colony architecture morphology on LBGM plates (B) of B. velezensis 118 (WT) and its derived sigX::erm mutant after 1, 3, or 5 d of incubation at 30 °C. (C) Biofilm production was quantified for both 118 WT and the sigX::erm mutant grown in LBGM medium at various indicated timepoints. Data represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by a student t-test, **P < 0.01. (D) Representative images show the pellicle formation of B. subtilis 3610, its derived sigX null mutant, and the complement strain sigX PspacsigX (sigX PsigX) in LBGM medium (top) and colony architecture morphology on LBGM plates (bottom) after 15–24 h incubation at 37 °C. Scale bars, 5 mm.

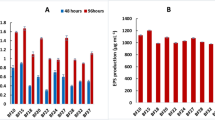

Next, we compared the effects of the B. velezensis sigX deletion with those observed in the more genetically tractable strain B. subtilis 3610. Consistent with prior studies27, the B. subtilis sigX null exhibited disrupted pellicle formation and less structured colonies compared to B. subtilis 3610 WT. This phenotype can be restored by complementation (Fig. 4D). Together, these data illustrate the pivotal role of σX in maintaining biofilm structure and integrity in both B. subtilis and B. velezensis. Biofilm formation is known to be correlated with the efficiency of root colonization17. Consistently, we note that the B. subtilis 3610 sigX mutant strain was compromised in its ability to colonize Arabidopsis thaliana roots, particularly at early time points (Supplementary figure S4). In contrast with these effects on root colonization, sigX mutants in both B. subtilis 3610 and B. velezensis 118 had only minor defects in swimming and swarming motility (Supplementary figure S5), and no differences were noted in the production of lipopeptides in B. velezensis 118 (Supplementary figure S6; Supplementary Table S4), which is predicted to encode a suite of secondary metabolites very similar to those produced by the type strain B. velezensis FZB42 (Supplementary Table S5).

The role of σX in enhancing the biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis 118

To evaluate the potential involvement of sigX in the biocontrol efficacy (BE) of B. velezensis 118, we monitored disease progression of banana and tomato plants exposed to the fungal pathogen Foc and the bacterial pathogen Rs, respectively (Fig. 5). In the absence of B. velezensis 118 treatment, the DI of banana plants exposed to Foc reached 66% at 21 d after transplanting. Treatment with WT B. velezensis 118 significantly reduced the DI to 23% (Fig. 5A-B), achieving a biocontrol efficacy of 65% against Foc. However, deletion of sigX led to a significantly reduced biocontrol efficacy against Foc, with a DI of 38% (Fig. 5A-B), resulting in a biocontrol efficacy of 42% for the sigX::erm mutant against Foc.

σX promotes the biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis 118. (A) The biocontrol ability of B. velezensis 118 and its derived sigX::erm mutant to suppress banana Fusarium wilt was evaluated in pot experiments. Four groups were included: CK1 (no Foc), uninfected banana seedlings were directly planted into pots; CK2 (Foc, only infected with Foc; Foc + WT (118), inoculated with both Foc and 118; and FOC + sigX::erm, inoculated with both Foc and sigX::erm. The data represent the mean values (n = 30). (B) Representative photographs of the banana plants showing the wilt incidence after 16 d transplantation. (C) The biocontrol ability of B. velezensis 118 and its derived sigX::erm mutant to suppress tomato bacterial wilt was evaluated in pot experiments with plants challenged by Ralstonia solanacearum (Rs). Four groups were included in the tomato bacterial wilt experiments: CK1 (no Rs), CK2 (Rs), Rs + WT (118), and Rs + sigX::erm. Data represent the mean values ± SD (n = 24, 95% confidence intervals). Significant differences between the two treated groups (Foc + 118 and Foc + sigX::erm) were determined by a two-tailed t-test, **P < 0.01, ns, not significant. (D) Representative photographs of the tomato plants showing the wilt incidence after 10 d transplantation.

In tomato bacterial wilt pot experiments, deletion of sigX also resulted in decreased biocontrol efficacy against Rs. Thirteen days after exposure to Rs, the DI of tomato plants treated with wild-type B. velezensis 118 was 51%, whereas those treated with the sigX::erm mutant had a DI of 69% (Fig. 5C-D). In contrast, the DI in plants not treated with B. velezensis 118 was 93% (Fig. 5C-D). Notably, sigX contributed to a 23% enhancement in biocontrol efficacy against Rs. These results underscore the significant role of sigX in the biocontrol efficacy of B. velezensis.

Discussion

Members of the Bacillus genus are notable for their ability to function as PGPR that both increase plant growth and suppress disease10,11. Growth stimulation is mediated both by the mobilization of soil micronutrients that benefit plant growth and by the physical and chemical inhibition of plant pathogens. A general model has emerged in which Bacillus spp. in the rhizosphere sense chemicals in root exudates that serve as chemoattractants61 and stimulate biofilm formation62. Biofilms formed on plant roots can physically occlude access by plant pathogens, and many Bacillus spp. also produce antimicrobial compounds in the rhizosphere that can inhibit the growth of potential pathogens11,19,63. The complex chemical and genetic interactions within the diverse microbial community in the rhizosphere, including bacteria, bacteriophage, and fungi, are only beginning to be untangled.

Although this general model can account for the growth-stimulating activities of beneficial rhizobacteria, the details of the underlying genetic programs are still emerging. Here, we have focused on B. velezensis 118, a rhizosphere soil isolate from near cultivated banana plants in Guangzhou, China. This isolate has strong anti-fungal activity against Foc (Fig. 1), reduces wilt incidence on banana seedlings exposed to Foc (Fig. 2), and suppresses tomato wilt due to the bacterial phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum (Fig. 5). These activities are similar to those described for numerous other B. velezensis isolates, including the type strain B. velezensis FZB4213,31.

The molecular genetic underpinnings of PGPR activity rely on complex regulatory circuity that, to a first approximation, can be modeled on B. subtilis 168 and its close relatives64. B. subtilis 168 was one of the first bacterial species to have its genome sequence determined65 and is an important model bacterium66,67. For example, the chemotaxis of Bacillus spp. towards root exudates relies on chemoreceptors and flagellar-based motility systems61. As originally characterized in B. subtilis 168, the genes for flagella biosynthesis68, methyl-accepting chemotaxis receptors (MCPs)69, and related signal transduction pathways are controlled by the alternative sigma factor σ[D 70–72. The colonization of roots by B. subtilis involves multiple chemoreceptors that can sense plant-derived compounds16. A role of (L)-malic acid in tomato root exudates was among the first identified signals to stimulate biofilm formation and is sensed by a surface-localize sensor kinase, KinD73. Other signals are also likely involved, and in banana root exudates oxalic acid, fumaric acid, and malic acid collaborate to induce biofilm formation74. Studies in B. velezensis SQR9 identified 39 chemoattractant and 5 chemorepellent compounds in root exudate that were sensed, primarily, by the McpA and McpC chemoreceptors75,76.

While flagellar-based motility and chemotaxis are key early steps in root association, efficient colonization requires the ability of bacteria to move over surfaces77 (swarming motility) and biofilm formation62. B. subtilis 168 strains are defective in both swarming motility and biofilm formation78,79, so the most incisive studies into these processes have been conducted in the closely related ancestral strain, B. subtilis 361028,59,80. B. subtilis 3610 is closely related to the 168 type strain (99.99 average nucleotide identity), but has several differences that have profound effects. Strains in the 168 lineage are defective for swarming due to mutations in the sfp and swrA genes, and correcting these mutations restores swarming motility81. Sfp is a 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase that activates non-ribosomal peptide synthetases82 and is therefore required for the production of lipopeptides and the siderophore bacillibactin. SwrA functions as a co-activator with DegU of the large flagellar gene cluster, which supports the hyper-flagellation phenotype associated with efficient surface motility83. In addition to sfp and swrA, mutations in the epsC and degQ genes in 168 reduce biofilm formation, and a large plasmid in B. subtilis 3610 contains genes that also affect biofilm formation and reduce competence79,84. Because of these genetic differences, the 3610 strain is the preferred model for B. subtilis swarming85 and biofilm formation59.

Biofilm formation in B. subtilis 3610 requires the coordinated induction of extracellular matrix components, including extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), polymers of the TasA protein, and a hydrophobic barrier composed of the BslA protein62,80,86,87. Plant-derived signals can induce biofilm formation by triggering a complex signaling cascade73,74,75,76,88, which activates matrix production in a subset of cells28,56,59, and downregulates and disables the flagellar-based motility apparatus89.

While there are still many gaps in our understanding of how biofilm formation is regulated, the key regulatory events are now clear59. The Spo0A response regulator controls a large suite of genes in a graded fashion90. Under conditions that favor biofilm formation, Spo0A is phosphorylated by one or more of several membrane-localized sensor kinases. The resultant Spo0A ~ P represses the transition state regulator AbrB and activates SinI, a key antagonist of SinR. SinR serves as a master regulator of biofilm formation by repression of exopolysaccharide (epsA-O) and protein (tapA-sipW-tasA) components of the matrix91. These and other genetic interactions have been integrated into a detailed model for the initiation of biofilm formation28,59,60.

Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors are also important for biofilm formation26,27. Of the seven ECF sigma factors in B. subtilis, mutations in sigX have the largest effect on biofilm formation27. The σX regulon has been defined in B. subtilis 168, although in several cases target genes have promoters that can be recognized by more than ECF sigma factor22,92,93. The σX regulon includes bcrC94, a bacitracin resistance determinant that encodes one of two redundant UPP phosphatases95 and the pssA and dlt loci, which together modify cell surface charge and contribute to resistance to antimicrobial peptides96,97. In addition, σX regulates abh98,99, an AbrB paralog that activates antibiotic (sublancin) synthesis by antagonizing the action of AbrB100. Abh also contributes to antibiotic resistance101, consistent with the finding that Abh and its homolog AbrB control antimicrobial resistance genes102. The role of σX in both sublancin synthesis and biofilm formation can be bypassed by ectopic expression of Abh, suggesting that this is the key σX-controlled gene involved in these processes27,100. Abh is important for biofilm formation due it ability to activate transcription of SlrR27,56. SlrR in turn functions as an epigenetic switch; by antagonizing SinR, SlrR derepresses biofilm matrix genes, and in concert with SinR functions as a SlrR/SinR heterodimer to repress motility functions103.

As a first approximation, we can assume that the genes and pathways that mediate motility, chemotaxis, biofilm formation, and antibiotic production and resistance are conserved between B. subtilis and B. velezensis. However, these two species only share ~ 80% average nucleotide identity (Fig. 1D). Even within B. velezensis, whole genome comparisons of 46 isolates revealed a range of genome sizes (3,610 to 4,436 genes), with a core genome of ~ 3000 genes and a pangenome of > 8000 genes104. Comparisons between B. velezensis and B. subtilis reveal a core genome of ~ 2574 genes105. Therefore, further strain-specific studies may yet reveal new aspects of these regulatory pathways and processes. It is challenging to accurately predict regulatory networks from DNA sequence alone, so further investigations using combinations of genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches will be needed.

We here demonstrate that B. velezensis 118 σX is important for pellicle formation (Fig. 3), and that the reduction in biofilm formation in a sigX mutant is correlated with reduced efficacy of disease suppression (Fig. 5). We suspect that σX supports biofilm formation by activating abh expression27. Indeed, B. velezensis 118 abh is preceded by a likely σX-dependent promoter similar to that in B. subtilis 16899, with identical sequences spanning the − 35 element (inclusive of a functionally important T-tract92) and the − 10 element (Supplementary figure S7)99. A role for σX in biofilm formation is also consistent with adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) experiments that selected for B. subtilis strains with increased root colonization106. In competition experiments with non-EPS producing (cheater) strains, mutations in the anti-σX factor rsiX supported improved colonization107, consistent with increased EPS production in rsiX mutants108.

The σX regulon may play additional roles in disease suppression beyond activation of biofilm formation. For example, two proteins inducible by exposure to root exudates in B. velezensis FZB42 were at least partially σX-dependent: an inositol utilization protein C (IolC) and a β-1,4-mannanase (YdhT) that mediates extracellular digestion of glucomannan109,110. Neither have been shown to be σX-dependent in B. subtilis. Further, σX may contribute to disease suppression and the restoration of the rhizosphere microbial community through its roles in activation of antibiotic synthesis100 and resistance genes94,96,101. Collectively, our findings support the idea that σX is part of an extended regulatory network important for biocontrol in the B. velezensis clade.

Data availability

Data Availability StatementWhole Genome Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI database with GenBank accession number CP000560.2. All other relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary Information.

References

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383 (2010).

Carvalho, F. P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 6, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.108 (2017).

de Andrade, L. A., Santos, C. H. B., Frezarin, E. T., Sales, L. R. & Rigobelo, E. C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural production. Microorganisms 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11041088 (2023).

Blake, C., Christensen, M. N. & Kovács, Á. T. Molecular aspects of plant growth promotion and protection by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 34, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-08-20-0225-CR (2020).

Saxena, A. K., Kumar, M., Chakdar, H., Anuroopa, N. & Bagyaraj, D. J. Bacillus species in soil as a natural resource for plant health and nutrition. J. Appl. Microbiol. 128, 1583–1594. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14506 (2020).

Ploetz, R. C. Fusarium Wilt of Banana. Phytopathology 105, 1512–1521. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0101-RVW (2015).

Yabuuchi, E., Kosako, Y., Yano, I., Hotta, H. & Nishiuchi, Y. Transfer of Two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia Gen. Nov. Microbiol. Immunol. 39, 897–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x (1995).

Raaijmakers, J. M., Paulitz, T. C., Steinberg, C., Alabouvette, C. & Moënne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 321, 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9568-6 (2008).

Carvalhais, L. C. et al. Linking plant nutritional status to plant-microbe interactions. PLoS One. 8, e68555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068555 (2013).

Bais, H. P., Fall, R. & Vivanco, J. M. Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by Biofilm formation and Surfactin Production. Plant Physiol. 134, 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.103.028712 (2004).

Ongena, M. & Jacques, P. Bacillus lipopeptides: Versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 16, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.009 (2008).

Pandin, C., Le Coq, D., Canette, A., Aymerich, S. & Briandet, R. Should the biofilm mode of life be taken into consideration for microbial biocontrol agents? Microb. Biotechnol. 10, 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12693 (2017).

Fan, B. et al. Bacillus velezensis FZB42 in 2018: The Gram-positive model strain for Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02491 (2018).

Fan, B. et al. Transcriptomic profiling of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 in response to maize root exudates. BMC Microbiol. 12, 1–13 (2012).

Zhang, N. et al. Whole transcriptomic analysis of the plant-beneficial rhizobacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 during enhanced biofilm formation regulated by maize root exudates. BMC Genom. 16, 1–20 (2015).

Allard-Massicotte, R. et al. Bacillus subtilis early colonization of Arabidopsis thaliana roots involves multiple chemotaxis receptors. mBio 7, 101128mbio01664–101128mbio01616. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01664-16 (2016).

Pomerleau, M. et al. Adaptive laboratory evolution reveals regulators involved in repressing biofilm development as key players in Bacillus subtilis root colonization. mSystems 9, e00843-00823. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00843-23 (2024).

Blake, C., Nordgaard, M., Maróti, G. & Kovács, Á. T. Diversification of Bacillus subtilis during experimental evolution on Arabidopsis thaliana and the complementarity in root colonization of evolved subpopulations. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 6122–6136. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15680 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Antagonism of two plant-growth promoting Bacillus velezensis isolates against Ralstonia solanacearum and fusarium oxysporum. Sci. Rep. 8, 4360. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22782-z (2018).

Luo, L., Zhao, C., Wang, E., Raza, A. & Yin, C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as an excellent agent for biofertilizer and biocontrol in agriculanre: An overview for its mechanisms. Microbiol. Res. 259, 127016 (2022).

Chowdhury, S. P., Hartmann, A., Gao, X. & Borriss, R. Biocontrol mechanism by root-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42–a review. Front. Microbiol. 6, 780 (2015).

Helmann, J. D. Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.002 (2016).

Luo, Y., Asai, K., Sadaie, Y. & Helmann, J. D. Transcriptomic and phenotypic characterization of a Bacillus subtilis strain without extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5736–5745. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00826-10 (2010).

Earl, A. M., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Bacillus subtilis genome diversity. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1163–1170. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01343-06 (2007).

Helmann, J. D. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 46, 47–110 (2002).

Mascher, T., Hachmann, A. B. & Helmann, J. D. Regulatory overlap and functional redundancy among Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6919–6927. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00904-07 (2007).

Murray, E. J., Strauch, M. A. & Stanley-Wall, N. R. SigmaX is involved in controlling Bacillus subtilis biofilm architecture through the AbrB homologue Abh. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6822–6832. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00618-09 (2009).

Cairns, L. S., Hobley, L. & Stanley-Wall, N. R. Biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis: new insights into regulatory strategies and assembly mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 93, 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12697 (2014).

Chen, X. H. et al. Comparative analysis of the complete genome sequence of the plant growth–promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1007–1014 (2007).

Kröber, M. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the biocontrol strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 as response to biofilm formation analyzed by RNA sequencing. J. Biotechnol. 231, 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.06.013 (2016).

Borriss, R. In Molecular Microbial Ecology of the Rhizosphere 883–898 (2013).

Rabbee, M. F. et al. Bacillus velezensis: A Valuable Member of Bioactive molecules within Plant Microbiomes. Molecules 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24061046 (2019).

Thanh Tam, L. T. et al. Two plant-associated Bacillus velezensis strains selected after genome analysis, metabolite profiling, and with proved biocontrol potential, were enhancing harvest yield of coffee and black pepper in large field trials. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1194887. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1194887 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Cold-adapted Bacilli isolated from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau are able to promote plant growth in extreme environments. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 3505–3526. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14722 (2019).

Xiong, H. Q., Li, Y. T., Cai, Y. F., Cao, Y. & Wang, Y. Isolation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens JK6 and identification of its lipopeptides surfactin for suppressing tomato bacterial wilt. Rsc Adv. 5, 82042–82049. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra13142a (2015).

Gowda, M. et al. Genome analysis of rice-blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae field isolates from southern India. Genom Data. 5, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gdata.2015.06.018 (2015).

Mascher, T., Margulis, N. G., Wang, T., Ye, R. W. & Helmann, J. D. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: The regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1591–1604. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03786.x (2003).

Kunst, F., Msadek, T. & Rapoport, G. In Regulation of Bacterial Differentiation (eds. Piggot, P. J., Moran, C. P. Jr, & Youngman, P.) 1-20 (American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC., 1994).

Koo, B. M. et al. Construction and analysis of two genome-scale deletion libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell. Syst. 4, 291–305e297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.12.013 (2017).

Quisel, J. D., Burkholder, W. F. & Grossman, A. D. In vivo effects of sporulation kinases on mutant Spo0A proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6573–6578. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.183.22.6573-6578.2001 (2001).

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Carbasse, J. S., Peinado-Olarte, R. L. & Goker, M. TYGS and LPSN: A database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D801–D807. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab902 (2022).

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P. & Goker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3 (2019).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae268 (2024).

Jain, C., Rodriguez, R. L., Phillippy, A. M., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Aluru, S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9 (2018).

Arkin, A. P. et al. KBase: The United States department of energy systems biology knowledgebase. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 566–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4163 (2018).

Blin, K. et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W46–W50. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad344 (2023).

Shemesh, M. & Chai, Y. A. Combination of glycerol and Manganese promotes Biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis via histidine kinase KinD signaling. J. Bacteriol. 195, 2747–2754. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00028-13 (2013).

Ploetz, R. C., Haynes, J. L. & Vazquez, A. Responses of new banana accessions in South Florida to Panama disease. Crop. Prot. 18, 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-2194(99)00043-5 (1999).

Chen, Y. et al. Biocontrol of tomato wilt disease by Bacillus subtilis isolates from natural environments depends on conserved genes mediating biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 848–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02860.x (2013).

Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15 (1962).

Idris, E. E., Iglesias, D. J., Talon, M. & Borriss, R. Tryptophan-dependent production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) affects level of plant growth promotion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 20, 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-20-6-0619 (2007).

Qin, Y., Han, Y., Shang, Q. & Li, P. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens L-H15, a plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolated from cucumber seedling substrate. J. Biotechnol. 200, 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.02.020 (2015).

Townsley, L., Yannarell, S. M., Huynh, T. N., Woodward, J. J. & Shank, E. A. Cyclic di-AMP acts as an Extracellular Signal that impacts Bacillus subtilis Biofilm formation and plant attachment. mBio 9 https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00341-18 (2018).

Wang, H., Cai, X. Y., Xu, M. & Tian, F. Enhanced biocontrol of cucumber Fusarium wilt by combined application of new antagonistic bacteria bacillus amyloliquefaciens B2 and phenolic acid-degrading Fungus Pleurotus ostreatus P5. Front. Microbiol. 12, 700142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.700142 (2021).

Mielich-Süss, B. & Lopez, D. Molecular mechanisms involved in Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12527 (2015).

Kobayashi, K. Bacillus subtilis pellicle formation proceeds through genetically defined morphological changes. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4920–4931. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00157-07 (2007).

Kovács, Á. T. & Dragoš, A. Evolved Biofilm: review on the experimental evolution studies of Bacillus subtilis pellicles. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 4749–4759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.005 (2019).

Vlamakis, H., Chai, Y., Beauregard, P., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Sticking together: Building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2960 (2013).

Arnaouteli, S., Bamford, N. C., Stanley-Wall, N. R. & Kovács, T. Á. Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation and social interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00540-9 (2021).

Milton, M. E. & Cavanagh, J. The biofilm regulatory network from Bacillus subtilis: A structure-function analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 435, 167923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167923 (2023).

Chen, L. & Liu, Y. The function of Root exudates in the Root colonization by Beneficial Soil Rhizobacteria. Biology 13, 95 (2024).

Beauregard, P. B., Chai, Y., Vlamakis, H., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Bacillus subtilis biofilm induction by plant polysaccharides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, E1621–E1630. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218984110 (2013).

Cawoy, H. et al. Lipopeptides as main ingredients for inhibition of fungal phytopathogens by Bacillus subtilis/amyloliquefaciens. Microb. Biotechnol. 8, 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12238 (2015).

Zeigler, D. R. et al. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6983–6995. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00722-08 (2008).

Kunst, F. et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390, 249–256 (1997).

Elfmann, C., Dumann, V., van den Berg, T. & Stülke, J. A new framework for Subti Wiki, the database for the model organism Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D864–D870 (2025).

Bremer, E. et al. A model industrial workhorse: Bacillus subtilis strain 168 and its genome after a quarter of a century. Microb. Biotechnol. 16, 1203–1231. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.14257 (2023).

Márquez-Magaña, L. M. & Chamberlin, M. J. Characterization of the sigD transcription unit of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2427–2434. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.176.8.2427-2434.1994 (1994).

Matilla, M. A. & Krell, T. Noncanonical sensing mechanisms for Bacillus subtilis chemoreceptors. J. Bacteriol. 204, e0002722. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00027-22 (2022).

Helmann, J. D., Márquez, L. M. & Chamberlin, M. J. Cloning, sequencing, and disruption of the Bacillus subtilis sigma 28 gene. J. Bacteriol. 170, 1568–1574 (1988).

Helmann, J. D. & Chamberlin, M. J. DNA sequence analysis suggests that expression of flagellar and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is controlled by an alternative sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84, 6422–6424. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.84.18.6422 (1987).

Mukherjee, S. & Kearns, D. B. The structure and regulation of flagella in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092406 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. A Bacillus subtilis sensor kinase involved in triggering biofilm formation on the roots of tomato plants. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08109.x (2012).

Yuan, J. et al. Organic acids from root exudates of banana help root colonization of PGPR strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6. Sci. Rep. 5, 13438 (2015).

Feng, H. et al. Identification of chemotaxis compounds in root exudates and their sensing chemoreceptors in plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 31, 995–1005 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Induced root-secreted D-galactose functions as a chemoattractant and enhances the biofilm formation of Bacillus velezensis SQR9 in an McpA-dependent manner. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 785–797 (2020).

Gao, S., Wu, H., Yu, X., Qian, L. & Gao, X. Swarming motility plays the major role in migration during tomato root colonization by Bacillus subtilis SWR01. Biol. Control. 98, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.03.011 (2016).

Patrick, J. E. & Kearns, D. B. Laboratory strains of Bacillus subtilis do not exhibit swarming motility. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7129–7133 (2009).

McLoon, A. L., Guttenplan, S. B., Kearns, D. B., Kolter, R. & Losick, R. Tracing the domestication of a biofilm-forming bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2027–2034. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01542-10 (2011).

Branda, S. S., Gonzalez-Pastor, J. E., Ben-Yehuda, S., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 98, 11621–11626. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.191384198 (2001).

Kearns, D. B., Chu, F., Rudner, R. & Losick, R. Genes governing swarming in Bacillus subtilis and evidence for a phase variation mechanism controlling surface motility. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03996.x (2004).

Quadri, L. E. et al. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37, 1585–1595. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi9719861 (1998).

Mishra, A. et al. SwrA-mediated multimerization of DegU and an Upstream activation sequence enhance Flagellar Gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 436, 168419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168419 (2024).

Burton, A. T. & Kearns, D. B. The large pBS32/pLS32 plasmid of ancestral Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 202 https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00290-20 (2020).

Patrick, J. E. & Kearns, D. B. Swarming motility and the control of master regulators of flagellar biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07917.x (2012).

Arnaouteli, S., MacPhee, C. E. & Stanley-Wall, N. R. Just in case it rains: Building a hydrophobic biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 34, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2016.07.012 (2016).

Dragoš, A. et al. Division of Labor during Biofilm Matrix Production. Curr. Biol. 28, 1903–1913.e1905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.046 (2018).

Habib, C. et al. Characterization of the regulation of a plant polysaccharide utilization operon and its role in biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS One. 12, e0179761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179761 (2017).

Guttenplan, S. B. & Kearns, D. B. Regulation of flagellar motility during biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 849–871 (2013).

Chen, Z., Zarazúa-Osorio, B., Srivastava, P., Fujita, M. & Igoshin, O. A. The slowdown of growth rate controls the single-cell distribution of biofilm matrix production via an SinI-SinR-SlrR network. mSystems 8, e00622-00622. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00622-22 (2023).

Kearns, D. B., Chu, F., Branda, S. S., Kolter, R. & Losick, R. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04440.x (2005).

Gaballa, A. et al. Modulation of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor promoter selectivity by spacer region sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx953 (2018).

Qiu, J. & Helmann, J. D. The – 10 region is a key promoter specificity determinant for the Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function sigma factors sigma(X) and sigma(W). J. Bacteriol. 183, 1921–1927. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.183.6.1921-1927.2001 (2001).

Cao, M. & Helmann, J. D. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis bcrC bacitracin resistance gene by two extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 184, 6123–6129. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.184.22.6123-6129.2002 (2002).

Zhao, H. et al. Depletion of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatases disrupts cell envelope biogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 198, 2925–2935. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00507-16 (2016).

Cao, M. & Helmann, J. D. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function sigmaX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1136–1146. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.186.4.1136-1146.2004 (2004).

Kingston, A. W., Liao, X. & Helmann, J. D. Contributions of the σ(W), σ(M) and σ(X) regulons to the lantibiotic resistome of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 502–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12380 (2013).

Huang, X., Fredrick, K. L. & Helmann, J. D. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis sigmaW: Autoregulation and partial overlap with the sigmaX regulon. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3765–3770. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.180.15.3765-3770.1998 (1998).

Huang, X. & Helmann, J. D. Identification of target promoters for the Bacillus subtilis sigma X factor using a consensus-directed search. J. Mol. Biol. 279, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1998.1765 (1998).

Luo, Y. & Helmann, J. D. Extracytoplasmic function sigma factors with overlapping promoter specificity regulate sublancin production in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4951–4958. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00549-09 (2009).

Murray, E. J. & Stanley-Wall, N. R. The sensitivity of Bacillus subtilis to diverse antimicrobial compounds is influenced by Abh. Arch. Microbiol. 192, 1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-010-0630-4 (2010).

Strauch, M. A. et al. Abh and AbrB control of Bacillus subtilis antimicrobial gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7720–7732. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01081-07 (2007).

Chai, Y., Norman, T., Kolter, R. & Losick, R. An epigenetic switch governing daughter cell separation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 24, 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1915010 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Complete genome sequencing of Bacillus velezensis WRN014, and comparison with genome sequences of other Bacillus velezensis strains (2019).

Cai, X. C., Liu, C. H., Wang, B. T. & Xue, Y. R. Genomic and metabolic traits endow Bacillus velezensis CC09 with a potential biocontrol agent in control of wheat powdery mildew disease. Microbiol. Res. 196, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2016.12.007 (2017).

Charron-Lamoureux, V., Lebel‐Beaucage, S., Pomerleau, M. & Beauregard, P. B. Rooting for success: evolutionary enhancement of Bacillus for superior plant colonization. Microb. Biotechnol. 17, e70001 (2024).

Nordgaard, M. et al. Experimental evolution of Bacillus subtilis on Arabidopsis thaliana roots reveals fast adaptation and improved root colonization. iScience 25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104406 (2022).

Martin, M. et al. Cheaters shape the evolution of phenotypic heterogeneity in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Isme j. 14, 2302–2312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0685-4 (2020).

Kierul, K. Comprehensive Proteomic Study of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Strain FZB42 and its Response to Plant root Exudates (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2013).

Kierul, K. et al. Influence of root exudates on the extracellular proteome of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Microbiol. (Reading). 161, 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.083576-0 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Pete Chandrangsu for advice during these studies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35GM122461 awarded to JDH and R00 AI168483 and DP2 AI184552 to HP. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. YC was supported by the China Scholarship Council during her time in the Helmann lab. This work was also supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to YC (41471214 and 41977035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., H.P., and J.D.H conceived and designed the experiments, Y.C., H.T., and A.G. conducted the experiments, Y.C., H.T., A.G., and H.P. analyzed the data, Y.C., H.P., and J.D.H wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Yanfei Cai is listed as an inventor on Chinese patent # ZL201910391310.3 owned by South China Agricultural University. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Tao, H., Gaballa, A. et al. The extracytoplasmic sigma factor σX supports biofilm formation and increases biocontrol efficacy in Bacillus velezensis 118. Sci Rep 15, 5315 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89284-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89284-7