Abstract

Increasing temperature due to global warming in the Himalayan regions has severe implications for the survival of aquatic ectotherms. To study the thermal acclimation and heat tolerance of an endangered Himalayan fish species, Tor putitora, we examined tissue-specific mRNA expression patterns of heat-shock proteins (HSP90β; HSP70, HSP60, HSP47, HSP30, and HSP20), warm-temperature acclimation proteins (WAP65-1) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B) genes in liver, brain, gill, kidney, muscle, and gonad tissues at the intervals of 10, 20, and 30 days during a high-temperature treatment (34.0 °C) for 30 days. All the tested genes have exhibited tissue-specific and time-dependent expression patterns. Heat shock proteins’ differential expression and modulation across examined tissues indicate their role in long-term cellular adaptation, protection against the cytotoxic effect of hyperthermia, and species acclimation to higher temperatures. WAP65-1 and CDKN1B expression in treatment groups suggests its involvement in maintaining homeostasis, long-term temperature acclimation, and thermotolerance during chronic thermal exposure. The response of studied genes under heat stress indicates their potential use as environmental stress biomarkers in this species. The present study elucidates molecular mechanisms regulating the thermal acclimation capacity and thermotolerance of T. putitora and its survival under future projections of widespread warming in the Himalayan region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ambient water temperature is the most critical ecophysiological variable affecting the performance of ectotherms. Fishes are, thus, more sensitive and vulnerable to any change in the temperature that lies beyond their physiological limits1. Therefore, the adaptation to dynamic changes in the environmental temperature would determine their long-term survival and fitness2. The increasing temperature due to global climate change has altered the thermal regimes of the aquatic ecosystem and the recent climate change models predicted an increase in mean water temperatures from 1.4 to 3.1 °C the next 65 years, posing a profound threat to the fish3,4. Moreover, the threat severity is even higher in the Himalayan regions as the estimated rate of warming is three times greater than the global average5.

Environmental stressors mostly lead to myriad physiological and cellular processes in fish through remarkable alteration in the transcript abundance of many genes6. The abilities to modulate expressions of different allozymes, genes, cell membrane modifications, or alterations to the intracellular environment that may or may not be reversible are some of the strategies of acclimation of thermal physiology observed across ectotherms7. In addition, the process of thermoregulation in fish enables them to adaptive shift in performance, thereby enhancing acclimation capacity at longer time scales8. Higher temperatures involve biological implications, including protein denaturation and misfolding as a cellular response to stress9. Incidentally, heat shock response (HSR) is the most common endogenous mechanism in fish to minimize cellular damage in the event of both acute and chronic temperature changes10. Different types of stressors, including temperature, leads to the expressions of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in cells to maintain many critical cellular processes as typical characteristics of HSR in fish11. These HSPs, or molecular chaperones, are critical in the synthesis, transport, and folding of proteins12. Three major families of HSPs are classified based on their molecular weights viz., HSP90 (85–90 kDa), HSP70 (68–73 kDa), and low molecular weight (LMW) heat shock proteins (16–47 kDa)10,13,14. When exposed to proteotoxic stressors, the higher expression of a large number of HSP genes (e.g., HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, HSP47) ensure survival under stressful condition through stabilization of damaged protein and prevents protein aggregation, which otherwise lead to irreversible cell damage and ultimately to cell death12,15. Basu et al. extensively reviewed the role of different HSPs and their functional significance in fish10. In addition to HSPs, the transcript level of warm-temperature-acclimation-associated 65-kDa protein (WAP65), a plasma glycoprotein first identified in goldfish (Carassius auratus) which is homologous to hemopexin found in mammals, also markedly increases in accordance with ambient temperature elevation16,17. The role of WAP65 in acclimation to warm temperatures has been investigated in several fish species in response to an increase in temperature16,18,19,20,21. Under chronic thermal stress conditions, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B), a gene mainly involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis, was found to be up-regulated as a cellular stress response in fish22,23. However, the magnitude of the expression of most of the genes involved in thermotolerance and acclimation correlates to the stress level experienced in the natural environment10. Further, most of these genes showed tissue-specific responses depending on the various molecular functions associated with each tissue type24. Additionally, fishes differ in their molecular responses to temperature variations depending on the level of environmental variability, prior acclimation, and degree of exposure, i.e., acute or chronic thermal stress22,23,25,26. Overall, the exposure to thermal stress in fish induces a set of multiple genes associated with HSR and warm temperature acclimation as a consequence of cellular stress responses that provide adaptive regulation to heat stress and higher plasticity to acclimatize to change in temperature10,22,27. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of tissue-specific molecular response to thermal stress provides necessary insight into thermal tolerance and acclimation in aquatic ectotherms, and it became more relevant under climate change scenarios24,28.

Golden mahseer (T. putitora) is an ‘endangered’ cold water rheophilic cyprinid fish species of great ecological, food, and recreational value in the Indian Himalayan region and also found in Southeast Asian drainages29,30,31. It is a large-bodied potamodromous freshwater fish migrating mainly to feed and spawn in the hill stream. The water temperature of the feeding ground of golden mahseer has been recorded in the range of 14 to 22 °C, while the spawning and incubation temperate varies from 16 to 25 °C in river water32. The Himalayan region is highly vulnerable to climate warming, and it is predicted that the region may experience an increase in temperature that may be at least 0.3 °C more than the predicted average global warming of 1.5 °C33,34. Recently, it was reported that the breeding phenology of golden mahseer in natural water bodies appears to have undergone a transition over the last ten decades as an implication of regional climate change35. Therefore, we investigated the tissue-specific mRNA expressions of genes involved in thermal tolerance and warm temperature acclimation to study the implications of chronic thermal exposure to golden mahseer. The expressions of both high and low molecular weight HSP genes (HSP90β, HSP70, HSP60, HSP47, HSP30, HSP20), WAP65-1, and CDKN1B were measured during the time course of thermal stress. In addition, we also tried to elucidate the significant roles of WAP65-1 and CDKN1B in warm temperature acclimation and thermotolerance in golden mahseer. We also presumed that T. putitora would show plasticity in their HSR during thermal exposure in a tissue-specific manner. The data presented in the current study would help elucidate the function of heat shock proteins and the adaption of golden mahseer under a thermally stressed environment.

Results

The relative fold change in mRNA levels of high (HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP60) and low (HSP47, HSP30, and HSP20) molecular weight HSP genes, WAP65-1, and CDKN1B were quantified in different tissues (liver, brain, gill, kidney, muscle, and gonad) of the fishes sampled at control (T0) and during high-temperature exposure (T10 to T30). We have also measured the length and weight of the fish in control and treatments at the start and at the time of sampling. There were no significant differences found in the total length, weight, or condition factor of the fish sampled at different time points (data not shown).

Effects of chronic thermal stress on mRNA expression of HSP90β, HSP70 and HSP60 genes

Under the chronic thermal exposure, the mRNA expressions of high molecular weight chaperones, HSP90β (Fig. 1A–F) and HSP70 (Fig. 2A–F) were significantly and consistently upregulated across all examined tissues except gonad at T10 relative to control (T0). Among all tissues, the liver showed the highest expression of HSP90β (Fig. 1A), whereas, the HSP70 expression level was 10-fold higher in the brain (p < 0.0001), gill (p < 0.001), kidney (p < 0.001) and muscle (p < 0.01) tissues at T10 compared to the constitutive expression at control (T0) (Fig. 2B–E). Further, we also observed that the expression level of HSP90β remained persistently upregulated in the liver and brain after an exposure of 20 (T20) and 30 days (T30) (Fig. 1A, B) and significantly downregulated in the kidney (Fig. 1D), while it returned to basal value in gill and muscle (Fig. 1C, E). However, mRNA expression of HSP70 remained upregulated after an exposure of 30 days (T30) in four tissues (brain, gill, kidney, and muscle) except the liver as compared to control (T0) (Fig. 2A–E). In addition, a pronounced decreased level of transcript abundance of HSP90β (Fig. 1A–E) and HSP70 (Fig. 2A–E) were measured at T30 compared to T10 across different tissues. In gonads, no significant differences in the mRNA expression of HSP90β and HSP70 were measured between the different time points (Figs. 1F and 2F).

Relative fold change of HSP90β (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Relative fold change of HSP70 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Measurement of mRNA expression of HSP60 indicated a significant variation across the tissues during different time points of high-temperature exposure (T10 – T30) (Fig. 3A – F). In liver, brain, and muscle tissues, it increased significantly at T10 and remained elevated across all tissues at T30, with an apparent decrease at T20 in liver and muscle (Fig. 3A, B, E). We also observed a consistently high abundance in the brain (Fig. 3B) and a linear increase in transcript abundance in gill tissue (Fig. 3C) during the high-temperature exposure (T10 – T30). In addition, liver and muscle expression of HSP60 showed distinct peaks at T10 and T30 with a more than 10-fold change (p < 0.0001) in hepatic tissue (Fig. 3A, E). Similar to HSP90β and HSP70, no significant differences observed in the transcript levels of HSP60 between the different time points in gonads (Fig. 3F).

Relative fold change of HSP60 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Effects of chronic thermal stress on mRNA expression of HSP47, HSP30 and HSP20 genes

The relative fold change in mRNA levels of LMW HSPs (HSP47, HSP30, and HSP20) in different tissues of the fishes sampled at control (T0) and at different time points of high-temperature exposure (T10 – T30) are shown in Figs. 4, 5, and 6. In the liver, brain, gill, and gonad tissues, the mRNA levels of HSP47 were significantly upregulated at T10 relative to control (T0) (Fig. 4A-C, F), and among all these tissues the highest expression was measured in the liver (12.65 fold, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A). We also observed consistently high transcript abundance in all examined tissues after an exposure of 30 days (T30) (Fig. 4A-F). Further, in the kidney, a progressive increase in mRNA expression of HSP47 was measured at different time intervals of thermal exposure (T10 – T30) (Fig. 4D).

Relative fold change of HSP47 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Relative fold change of HSP30 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Relative fold change of HSP20 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

The HSP30 gene expression demonstrated a similar pattern in brain and gill tissues, where a significant linear progression in transcript abundance was detected (Fig. 5B, C) during high-temperature exposure (T10 to T30). Further, the highest mRNA expression of HSP30 was measured in the gill tissue under thermal stress. It was remarkably upregulated (22.90-fold, p = 0.02) over a period of 10 days of exposure (T10) relative to control (T0) and reached the peak level (29.43-fold, p = 0.02) after an exposure of 30 days (T30) (Fig. 5C). On the other hand, in kidney and gonad, the mRNA level of HSP30 was significantly downregulated at the later period (T20 – T30) of thermal exposure (Fig. 5D, F). The transcript level of HSP20 showed a significant difference in brain, gill and gonad tissues with a bimodal peak in the brain at T10 and T30 (Fig. 6B, C, F). However, gill mRNA showed an increased expression level after a thermal exposure of 10 days (T10), which remained upregulated during a later period (T20 – T30) compared to control (T0) (Fig. 6C). In the liver, the expression of HSP20 displayed apparent fluctuation. However, the differences were statistically insignificant compared to T0 (Fig. 6A).), whereas in the gonad, mRNA expression was significantly upregulated at T10 and returned to the constitutive expression value after 20 days (T20 – T30) of thermal exposure (Fig. 6F). No significant differences in HSP20 mRNA expression were observed in the kidney and muscle tissues at different time points of high-temperature exposure (T0 to T30) (Fig. 6D, E).

Effects of chronic thermal stress on mRNA expression of WAP65-1 and CDKN1B genes

The transcript of WAP65-1 was widely distributed in golden mahseer tissues. However, the expression was the most abundant in the kidney (Fig. 7). Golden mahseer WAP65-1 was then highly expressed in the liver and gill, and followed by the brain and gonad. However, the expression of WAP65-1 was significantly (p < 0.0001) downregulated in muscle during the time course of heat exposure (T10 – T30) (Fig. 7E). It was also noted that there was a linear increase in the transcript abundance in the liver, brain, and gill tissues (Fig. 7A – C) with the increasing time course of thermal exposure (T10 – T20), and it remained persistently upregulated in the brain (T20 – T30). However, the expression of WAP65-1 returned to its constitutive level in all other tissues (liver, gill, kidney, and gonad) (Fig. 7). The mRNA expression levels of CDKN1B measured across different tissues of golden mahseer are depicted in Fig. 8. Among all examined tissues, only liver and brain showed a very low level of CDKN1B mRNA, and it was persistently high during the period of thermal exposure (Fig. 8A, B). The summary of the expression pattern of genes in different tissues at various time points of the thermal exposure is depicted in the Table 1.

Relative fold change of WAP65-1 (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 fish per time point) and were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Relative fold change of CDKN1B (A–F) mRNAs in different tissues of golden mahseer examined in the control (T0) and over the time-course (days) of high temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 5 fish per time point) and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Different superscripts (a, b, c) above the bars indicate significant difference.

Discussion

In the current study, the state of thermal tolerance and adaption were examined by tissue-specific mRNA expression of HSPs and genes related to thermal acclimation and thermotolerance (WAP65-1 and CDKN1B) in T. putitora over long-term exposure to an elevated temperature (34 °C). The results showed that golden mahseer exhibits plasticity in its HSR by altering its expression of HSPs in response to the duration of thermal exposure and also shows considerable heterogeneous expression patterns during the time course of heat stress. The upregulation of both HSP90β and HSP70 in all the examined tissues (except gonad) after a thermal exposure of 10 days (T10) indicates heat shock response to short-term stress, while persistent upregulation of HSP90β in liver and brain as well as HSP70 in brain, gill, kidney and muscle tissue on a long-term (20 and 30 days) exposure suggest acclimation towards heat shock and modulation in expression of HSPs in these tissues of golden mahseer36. Tissue-specific and time-dependent variations in the expression of the HSPs in response to thermal stress have previously been reported in teleost like striped snakehead (Channa striatus), pool barb (Puntius sophore) and spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) and gill, liver, and muscle have been observed as primary tissues responding to heat stress in fish36,37,38,39,40,41. However, in our study, heat-induced upregulation in mRNA expression of HSP90β and HSP70 was also observed in other examined tissues like the brain and kidney of golden mahseer, which indicates its sensitivity to elevated temperature, adaptation towards heat stress and role in organismal survival37,42. HSP90 is known to be the most commonly expressed HSP and it plays an active role in maintaining several components of the cytoskeleton and steroid hormone receptors43. It was found upregulated in the fish residing in hot spring run-off and also during experimentally challenged to higher temperatures such as snow trout (Schizothorax richardsonii)39,44,45. Similarly, in the present study, the upregulation of HSP90β might be indicative of long-term stress adaptation as among two major cytoplasmic isoforms of HSP90 (i.e., HSP90α and HSP90β), HSP90β is reported to be involved in long-term cellular adaptation46. The upregulation of HSP70 under prolonged heat exposure in the present study indicates its role in the protection against the cytotoxic effect of hyperthermia and reduction in oxidative stress caused by continuously elevated temperature as well as preventing polypeptide aggregation and refolding of damaged proteins under heat stress47,48,49. The present finding also conforms with past studies that reported overexpression of HSP70 in aquatic organisms to resist the pressure of rising temperatures50. It is also noted that the lack of introns in the heat-inducible form might have allowed efficient transcription, leading to strong induction of HSP70 genes during heat shock36,51. Furthermore, the high mRNA expression pattern of HSP70 in gill, kidney, and muscle tissue indicated that it might be correlated to immune and metabolic response under heat stress49,52,53. However, further investigation is required to confirm these tissues’ physiological function and correlation under heat stress in this species.

In the current investigation, the highest mRNA expression of HSP60 in the liver probably indicates its higher requirement in reducing the heat-induced protein damage in the hepatic tissue than other tissues of golden mahseer. In addition, the persistent high mRNA expression of HSP60 under chronic thermal exposure (30 days) in the present study suggests that hepatic damage caused by temperature stress is not easily reversed. Moreover, the continuous synthesis of HSP60 in different tissues (brain, gill, and muscle) also suggests its role in the acclimation and survival of golden mahseer (T. putitora) at higher temperature, as reported in the striped snakehead (C. striatus) under heat stress38. The higher expression of HSP60 in gill tissue suggests an increase in resistance of gill cells against constant exposure to heat stress, and upregulation in renal tissue indicates that the kidney might have adapted to chronic heat stress, as reported in rainbow trout54. We found that during the high-temperature exposure (T10 –T30) to golden mahseer, HSP60 expression patterns varied among tissues, where it showed remarkably high transcript level after ten days of exposure and then declined afterward but remained significantly high compared to control (T0). This apparent modulation and constant upregulation of HSP60 could be perceived as a danger signal of stressed or damaged cells55,56 and species acclimation to higher experimental temperatures where continuous synthesis of HSP60 is necessary for its survival22,38. In addition, higher expression of HSP60 has also been seen as a potential early warning system for environmental changes57.

Notably, in our study, no significant mRNA expression of HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP60 was detected in golden mahseer gonads during heat stress (T10 –T30). In contrast to the present investigation, Mahanty et al.., reported the downregulation of all three genes in pool barb (P. sophore) gonads under thermal stress58. The absence of significant changes in expression of HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP60 in the gonads of T. putitora after chronic thermal exposure might be due to tissue specificity as heat shock response differs among tissues and also supports the hypothesis that certain tissue is more sensitive than others in regulating the thermal limits of an organism37. Nevertheless, due to their ubiquitous presence and higher expression in various cellular forms, HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP60 genes have been identified as critical biomarkers responsible for the adaptive effect of thermal stress in fish38,59,60.

LMW chaperones, HSP47, HSP30, and HSP20, showed varied expression patterns in different tissues of golden mahseer during thermal exposure. In the present study, the highest expression of HSP47 (also known as Serpin H1) in the hepatic tissue of golden mahseer was in contrast to the earlier findings in zebrafish where it was upregulated in the brain but not in the liver or muscle after a heat shock response61. Similarly, no differential expression was detected in hepatic HSP47 in goldfish (C. auratus) sampled from lakes having continuously high temperatures62. On the other hand, HSP47 upregulation was reported in the liver of pool barb (P. sophore) sampled from a hot spring and after experimental heat shock treatment58. The increase in transcript level of HSP47 has also been reported under chronic temperature stress in the gills, liver, kidney, and muscle tissues of salmonids62,63 and Atlantic cod64. Based on the previous studies and present findings, it could be observed that the HSP47 gene expression varies among teleost in a species-specific manner in response to environmental conditions and also shows tissue-specific expression pattern37,65,66. HSP47 is a collagen-binding glycoprotein that is found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and interestingly, it is the only stress protein in the ER induced by heat shock67. In our investigation, the upregulation of HSP47 in different tissues of golden mahseer during the time course of heat exposure suggests its involvement in the refolding of misfolded proteins and degradation of potentially toxic misfolded or aggregated proteins67.

The differential expression of HSP30, and HSP20, a member of small heat shock protein family (sHSPs), were examined across different tissues of heat-stressed golden mahseer. The highest expression of both the genes in gill indicates its higher sensitivity than other tissues to a higher temperature as gill remained directly exposed to heat stress environment, therefore often selected as the target organ for analysis of HSP gene expression in adult fish68. Expression across different tissues also suggests its role in the prevention of proteins’ irreversible aggregation, as these HSPs maintain a refolding conformation by binding to abnormal proteins produced due to heat stress69,70. Our results are consistent with previous findings that reported highest HSP30 mRNA expression in the gill of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) under heat stress71,72. In addition, consistent high expression of HSP30 in the heat-stressed liver also indicates its role in modulating the thermal acclimation in golden mahseer (T. putitora) as reported in goldfish (C. auratus) and gilt-head bream (Sparus aurata)73,74. A linear increase in HSP30 mRNA expression in the brain tissue during the time course of high-temperature exposure suggests its potential role in protein homeostasis and thermotolerance in golden mahseer to heat stress as found in different teleost72,75. The downregulation of HSP30 in the kidney and gonad after a high-temperature exposure of 30 days indicates a tissue-specific expression pattern of this heat shock protein in golden mahseer37,65,72. In contrast to present finding, HSP20 was also detected in several other tissues of goldfish under heat stress76. Modulation of HSP20 in brain and gonad tissues suggests thermotolerance and acclimation as well as its distinct sensitivity compared to the other organs in golden mahseer. The role of HSP20 in thermotolerance and its regulation by heat stress has also been reported in disk abalone (Haliotis discus discus)77. Furthermore, specific substrates and other regulators besides the well-known heat shock protein factors (Hsfs) were found to influence the temporal and tissue-specific constitutive expression of sHSPs78. However, the information on the temperature regulation of HSP20 in fish needs to be better understood76. Even though the liver and kidney are essential organs involved in immunity and metabolism, the absence of significant mRNA expression of HSP20 in these tissues of heat-stressed golden mahseer would need further investigation54.

In the present investigation, differential expression of WAP65-1 was ubiquitously detected in all the examined tissues, with the highest expression being in the renal tissue of heat-stressed golden mahseer. WAP65 has been found to be involved in the acclimation of fish to warm temperatures, and therefore ubiquitously detected in most tissues with variable expression levels in several teleost16,79,80,81. However, in contrast to our findings, other studies have revealed predominantly high transcript abundance of WAP65-1 in the hepatic tissue in Plecoglossus altivelis81, Scophthalmus maximus82, Misgurnus mizolepis80, Takifugu rubripes19, and Oryza latipes83. In C. auratus (10-fold) and Cyprinus carpio (8-fold) increase in mRNA expression of WAP65-1 in hepatopancreas have been detected during the temperature acclimation from 10 to 30 °C16,18. In addition, tissue-specific contrasting expression patterns of WAP65-1 have been reported in different fish species; for example, a low level of mRNA expression has been detected in the kidney of mud loach (M. mizolepis) after a heat treatment to 32 °C, while it did not express either in renal or brain tissues of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) at any time points of four weeks of thermal exposure79,80. The kidney being a primary hematopoietic organ in fishes, the highest expression of WAP65-1 in renal tissues of golden mahseer in the present study indicates its probable role in maintaining homeostasis during chronic thermal exposure, as it is known that WAP65-1 plays a crucial role in warm temperature acclimation, most likely by limiting the body’s accumulation of free heme and free metals, thereby reducing toxicity79,83,84. Interestingly, we observed that the mRNA transcript level of WAP65-1 returned to basal value after an exposure of 30 days in the liver, gill, kidney, and gonad tissues except the brain, while it was downregulated in the muscle tissue in the heat-exposed golden mahseer. Our findings in heat-shocked golden mahseer differ from the previous results obtained in seabass, where no expression of WAP65 was detected in muscle tissue during the second and third week but again expressed after four weeks’ post-acclimation79. This suggests that WAP65-1 might express differentially in various organs in different organisms. Qualitatively speaking, our findings are in line with other previously published reports that showed WAP65 expression in some or all of the examined tissues in different species18,19,80,85. Consequently, our finding supports the notion that WAP65-1 express in a wide range of tissues in teleost in response to a warm temperature acclimation in a species-specific manner86.

Nevertheless, our result indicates that WAP65-1 plays an essential role in golden mahseer’s long-term temperature acclimation process81. However, further elucidation of functions and pathways of WAP65-1 will provide better understanding related to the association of this protein in the temperature-acclimation system of poikilotherms. Since WAP65-1 gene expressed under stress condition in wide variety of golden mahseer tissue, this gene appears to be a potential biomarker for environmental monitoring and evaluation of fish quality under thermal regulation79.

Under chronic thermal stress, CDKN1B primarily regulates the cell division and cell cycle by downregulating the cell cycle, which was indicated by its upregulation23,87. A significantly high level of mRNA transcript of CDKN1B in hepatic and brain tissues of golden mahseer during high-temperature exposure suggests its role in controlling the cell cycle as a cellular stress response as found in eurythermal goby fish (Gillichthys mirabilis) where high transcript abundance of CDKN1B was detected in the gill tissue under the extreme thermal stress22. Furthermore, in the event of heat stress, blockage of the energy-demanding process of cell division is essentially required to facilitate the energy-driven process of cellular stress response like the HSPs function. In addition, it also helps prevent the cell from replicating before DNA repair can be effected where heat-induced damage to their DNA has incurred23. The high expression pattern of the CDKN1B gene in golden mahseer under heat stress indicates the acclimation capacity of this species to the thermal stress and the role of this gene in the prevention of cell damage and apoptosis as described in goby fish (G. mirabilis) and delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus)22,87. Although the involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) family of proteins in cell cycle regulation, proliferation, and development has been explored, its role in providing thermotolerance in different teleost is not completely understood and needs further investigation87,88.

The present study demonstrated the acclimation capacity and thermotolerance in an endangered fish species, golden mahseer, exposed to high temperature and to our knowledge, this is the first account of extensive information on the tissue-specific response of environmental stress-related genes in a Himalayan fish species. In contrast to some cold climate fish like emerald rockcod (Trematomus bernacchii) which is unable to show a heat shock response, the molecular response particularly, HSPs induced by thermal stress in golden mahseer (T. putitora) suggests some form of plastic response that has fitness consequences and would be helpful in its survival in case of sustained alternation of the environment due to climate change6,24,89. In addition, the modulation of transcript abundance of HSPs, WAP65-1, and CDKN1B genes in golden mahseer also suggests their utility as critical biomarkers for the determination of adaptive change in this species under complex stress environments. However, further studies at the transcriptome and proteome levels are warranted to better understand the molecular mechanism underpinning the thermal tolerance and environmental adaptation to increasing temperature at species and population levels.

Methods

Experimental design and tissue collection

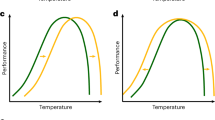

To examine the differential regulation of HSPs, WAP65-1, and CDKN1B genes in response to chronic thermal stress, golden mahseer were subjected to heat treatment. Healthy golden mahseer (T. putitora) of both sexes (n = 200) with average body weight of 24.94 ± 8.26 g and average length of 14.3 ± 1.70 cm was collected from the hatchery of ICAR-Directorate of Coldwater Fisheries Research, Bhimtal, and acclimatized for a period of six weeks in a 1000 L FRP tank at water temperature 25 ± 0.5 ⁰C with optimum dissolved oxygen (6.5-7.0 mg/l) and pH (~ 7.7) to avoid any incidental mortality. Fishes were fed twice daily with a commercially available pelleted feed (crude protein − 40%; crude lipid − 15%) at the rate of 3% of body weight. For chronic thermal exposure, four glass aquaria, i.e., one as ‘control’ and the other three as ‘treatment’ tanks of 90 L water holding capacity, were set up, and each tank was stocked with n = 20 fishes randomly selected from the pre-acclimatized specimens. The temperature in the ‘control’ tank was maintained at 25.0 ± 0.5 ⁰C. In contrast, the temperature in the treatment tanks was increased at the rate of 1.0 °C/day over nine days until it reached the targeted experimental temperature of 34.0 °C. Subsequently, a high temperature (34.0 ± 0.5 °C) was continuously maintained for 30 days in the treatment tanks (Fig. 9). The control and experimental temperature were selected based on the temperature profile of the natural occurrence of T. putitora and the future climate projection of widespread warming (~ 5–8 °C) in the Himalayan region32,90. The desired water temperature was maintained in the ‘control’ and ‘treatment’ tanks using stainless steel water heaters (300-W, Sobo, China), and thermostat (STC-1000, India). During the exposure period, each day, one-third of the aged water was replaced with pre-heated (for Control = 25.0 °C; Treatment = 34.0 ⁰C) freshwater to avoid any major fluctuation in temperature. Optimum dissolved oxygen level (DO ≥ 7 ppm) was maintained using adequate aeration in the tank, and other water quality parameters such as pH (~ 7.7-8.0) and ammonia (< 0.05 ppm) were regularly monitored on a daily basis. Fishes were fed ad libitum with commercially available pelleted feed (crude protein- 40%; crude lipid- 15%) during the experimental period. No abnormal behaviour, diseased symptom, or mortality was observed in experimental fishes during the exposure period.

Schematic representation of the experimental design and sampling points during the entire period of the experiment. T0 sampling was done after the acclimation period of six weeks, whereas T10 (10 days), T20 (20 days), and T30 (30 days) represents the sampling after an exposure of high-temperature treatment (34.0 ± 0.5 °C).

For sampling, five individuals were collected randomly from the ‘control’ (T0) and ‘treatment’ tanks over the time course of high-temperature exposure at the intervals of 10 days (T10), 20 days (T20), and 30 days (T30) after achieving the targeted experimental temperature. Prior to sampling, the fishes were fasted for 24 h and then euthanized with an overdose of 100 mg/L tricaine methane sulfonate (MS-222, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Subsequently, the weight (g) and length (cm) of individual fish were recorded, and a total of six tissues that include liver, brain, gill, kidney, muscle, and gonad, were collected rapidly in cryotubes and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C, until further use.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from each tissue using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA/New Delhi), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was further treated with the DNase I, RNase free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to remove the genomic DNA contamination. The concentration and quality of total RNA were determined by using NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, USA) at 260 nm absorbance and agarose gel electrophoresis (1.3% MOPS/formaldehyde agarose gels) respectively. Total RNA (1 µg) from each tissue sample was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the Prime Script™ 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (Clonetech Takara Bio, CA, USA) and random hexamer primers, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, cDNA was stored at -20 °C until further use.

mRNA expression analysis: quantitative RT-PCR

The mRNA level of selected HSPs, WAP65-1 and CDKN1B in control (T0) and during high-temperature exposure (T10, T20, and T30) were analysed in the six tissues that include liver, brain, gill, kidney, muscle, and gonad of individual fish (N = 5 biological replicates). Specific primers for each gene were designed using Primer-BLAST suite (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) based on the DNA sequences presented in GenBank (Table 2). The optimal annealing temperature of each primer ranged between 60 and 62 °C, and the amplicons size ranged between 82 and 158 bp. Specificity of gene amplification was confirmed by melt curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR efficiency was calculated based on the slope of a standard curve generated using two-fold serial dilutions of pooled cDNA. The efficiency was calculated as follows: E (%) = (10− 1/slope − 1) x10091. The acceptable E value was defined as between 90 and 110%. The target mRNA expression levels were quantified using a CFX 96 Real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNAseH Plus) (Takara, USA) and gene-specific primers following the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were performed using 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq II qPCR Mix (2X), 5µL 25-fold diluted cDNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µl in two technical replicates for each of five independent biological experiments. The PCR was performed using the following program: 95 °C for 30s, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, 10 s at 60 °C, and 10 s at 72 °C. Melting curves (from 65 to 95 °C, at a temperature gradient of 0.5 °C per 10 s) were systematically monitored to confirm the specificity of the amplification reaction at the end of the last amplification cycle. No-template control (NTC) reactions were also included on each plate. Following the MIQE guidelines, two reference genes namely ribosomal protein S18 (RPS18) and tata box binding protein (TBP) were used for the normalization of target gene expression data after comparatively evaluating the expression of seven commonly used reference genes92. The stability of reference genes was determined using the RefFinder (https://www.heartcure.com.au/reffinder/)93. Relative quantification of target mRNA expression was performed using the model described by Pfaffl after correcting for reaction efficiency94.

Statistical analysis

All the data generated during the study were statistically analysed using the GraphPad Prism software (ver.10, La Jolla, CA, USA) and results are presented as means ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to find the significant difference in target mRNA expression in all the tissues between the different time points of thermal exposure from the control. Differences were considered statistically significant when P value was less than 0.05.

Data availability

The gene sequence has been submitted to NCBI and is available against the GenBank accession number provided (Table 2).

References

Pörtner, H. O. Climate variations and the physiological basis of temperature dependent biogeography: Systemic to molecular hierarchy of thermal tolerance in animals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 132 (4), 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00045-4 (2002).

Somero, G. N. The physiology of climate change: How potentials for acclimatization and genetic adaptation will determine ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. J. Exp. Biol. 213 (6), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.037473 (2010).

Comte, L. & Olden, J. D. Climatic vulnerability of the world’s freshwater and marine fishes. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 718–722. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3382 (2017).

Manzon, L. A. et al. Thermal acclimation alters both basal heat shock protein gene expression and the heat shock response in juvenile lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). J. Therm. Biol. 104, 103185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103185 (2022).

Shrestha, U. B., Gautam, S. & Bawa, K. S. Widespread climate change in the Himalayas and associated changes in local ecosystems. PLoS ONE. 7 (5), e36741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036741 (2012).

Oomen, R. A. & Hutchings, J. A. Transcriptomic responses to environmental change in fishes: Insights from RNA sequencing. Facets 2 (2), 610–641. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0015 (2017).

Schulte, P. M. The effects of temperature on aerobic metabolism: Towards a mechanistic understanding of the responses of ectotherms to a changing environment. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1856–1866. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.118851 (2015).

Alfonso, S., Gesto, M. & Sadoul, B. Temperature increase and its effects on fish stress physiology in the context of global warming. J. Fish. Biol. 98 (6). https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14599 (2021). 1496 – 508.

Saibil, H. Chaperone machines for protein folding, unfolding and disaggregation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 630–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3658 (2013).

Basu, N. et al. Heat shock protein genes and their functional significance in fish. Gene 295 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00687-X (2002). 173 – 83.

Iwama, G. K., Thomas, P. T., Forsyth, R. B. & Vijayan, M. M. Heat shock protein expression in fish. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 8, 35–56 (1998).

Morimoto, R. I. Cells in stress: Transcriptional activation of heat shock genes. Science 259 (5100), 1409–1410. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8451637 (1993).

Morimoto, R. I., Tissieres, A. & Georgopoulos, C. (eds) The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperonesvol 26 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1994).

Yu, E. M. et al. The complex evolution of the metazoan HSP70 gene family. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 17794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97192-9 (2021).

Fulda, S., Gorman, A. M., Hori, O. & Samali, A. Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Inter. J. Cell Biol. 23 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/214074. Article ID 214074 (2010).

Kikuchi, K., Yamashita, M., Watabe, S. & Aida, K. The warm temperature acclimation-related 65-kDa protein, Wap65, in Goldfish and its gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (29), 17087–17092. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.29.17087 (1995).

Machado, J. P., Vasconcelos, V. & Antunes, A. Adaptive functional divergence of the warm temperature acclimation-related protein (WAP65) in fishes and the ortholog hemopexin (HPX) in mammals. J. Hered. 105, 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/est087 (2014).

Kinoshita, S., Itoi, S. & Watabe, S. cDNA cloning and characterization of the warm-temperature-acclimation-associated protein Wap65 from carp, Cyprinus carpio. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 24, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011939321298 (2001).

Hirayama, M. et al. Primary structures and gene organizations of two types of Wap65 from the pufferfish Takifugu rubripes. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 29, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:FISH.0000045723.52428.5e (2003).

Choi, C. Y., An, K. W., Choi, Y. K., Jo, P. G. & Min, B. H. Expression of warm temperature acclimation-related protein 65-kDa (Wap65) mRNA, and physiological changes with increasing water temperature in black porgy, Acanthopagrus Schlegeli. J. Exp. Zool. 309, 206–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.449 (2008).

Roh, H. et al. Identification and characterization of warm temperature acclimation proteins (Wap65s) in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 135, 104475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2022.104475 (2022).

Logan, C. A. & Somero, G. N. Effects of thermal acclimation on transcriptional responses to acute heat stress in the eurythermal fish Gillichthys mirabilis (Cooper). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300 (6), R1373–R1383. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00689.2010 (2011).

Somero, G. N. The cellular stress response and temperature: Function, regulation, and evolution. J. Exp. Zool. Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 333 (6), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.2344 (2020).

Smith, S., Bernatchez, L. & Beheregaray, L. B. RNA-seq analysis reveals extensive transcriptional plasticity to temperature stress in a freshwater fish species. BMC Genom. 14, 1–12 (2013). http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/14/375

Podrabsky, J. E. & Somero, G. N. Changes in gene expression associated with acclimation to constant temperatures and fluctuating daily temperatures in an annual killifish Austrofundulus limnaeus. J. Exp. Biol. 207 (13), 2237–2254. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01016 (2004).

Fangue, N. A., Osborne, E. J., Todgham, A. E. & Schulte, P. M. The onset temperature of the heat-shock response and whole-organism thermal tolerance are tightly correlated in both laboratory-acclimated and field-acclimatized tidepool sculpins (Oligocottus maculosus). Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 84, 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/660113 (2011).

Tomanek, L. Variation in the heat shock response and its implication for predicting the effect of global climate change on species’ biogeographical distribution ranges and metabolic costs. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.038034 (2010).

Crozier, L. G. & Hutchings, J. A. Plastic and evolutionary responses to climate change in fish. Evol. Appl. 7, 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12135 (2014).

Jha, B. R., Rayamajhi, A., Dahanukar, N., Harrison, A. & Pinder, A. Tor putitora. IUCN Red List. Threatened Species. e.T126319882A126322226 https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T126319882A126322226.en (2018).

Pinder, A. C. et al. Mahseer (Tor spp.) fishes of the world: Status, challenges and opportunities for conservation. Rev. Fish. Bio l Fisheries. 29, 417–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-019-09566-y (2019).

Jaafar, F. et al. A current update on the distribution, morphological features, and genetic identity of the southeast Asian mahseers. Tor. Species Biol. 10 (4), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10040286 (2021).

Bhatt, J. P. & Pandit, M. K. Endangered golden mahseer Tor putitora Hamilton: A review of natural history. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 26, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-015-9409-7 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Elevational shifts of freshwater communities cannot catch up climate warming in the Himalaya. Water 8, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8080327 (2016).

Krishnan, R. et al. Unravelling climate change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Rapid warming in the mountains and increasing extremes. In The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment-Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People (eds. Wester, P., Mishra, A., Mukherji, A. & Shrestha, A. B.) 57–97 (Springer, 2019).

Joshi, K. D. et al. Pattern of reproductive biology of the endangered golden mahseer Tor putitora (Hamilton 1822) with special reference to regional climate change implications on breeding phenology from lesser himalayan region, India. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 46 (1), 1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2018.1497493 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. HSP90 and HSP70 families in Lateolabrax maculatus: Genome-wide identification, molecular characterization, and expression profiles in response to various environmental stressors. Front. Physiol. 12, 784803. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.784803 (2021).

Dyer, S. D., Dickson, K. L., Zimmerman, E. G. & Sanders, B. M. Tissue-specific patterns of synthesis of heat-shock proteins and thermal tolerance of the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Can. J. Zool. 69, 2021–2027. https://doi.org/10.1139/z91-282 (1991).

Purohit, G. K. et al. Investigating hsp gene expression in liver of Channa Striatus under heat stress for understanding the upper thermal acclimation. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014 (381719). https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/381719 (2014).

Mahanty, A., Purohit, G. K., Yadav, R. P., Mohanty, S. & Mohanty, B. P. hsp90 and hsp47 appear to play an important role in minnow Puntius sophore for surviving in the hot spring run-off aquatic ecosystem. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 43, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-016-0270-y (2017).

Shin, M. K., Park, H. R., Yeo, W. J. & Han, K. N. Effects of thermal stress on the mRNA expression of SOD, HSP90, and HSP70 in the spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax Maculatus). Ocean. Sci. J. 53, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12601-018-0001-7 (2018).

Peng, G. et al. Cloning HSP70 and HSP90 genes of kaluga (Huso dauricus) and the effects of temperature and salinity stress on their gene expression. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 21, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-015-0665-1 (2016).

Topal, A., Özdemir, S., Arslan, H. & Çomaklı, S. How does elevated water temperature affect fish brain? (A neurophysiological and experimental study: Assessment of brain derived neurotrophic factor, cFOS, apoptotic genes, heat shock genes, ER-stress genes and oxidative stress genes). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 115, 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2021.05.002 (2021).

Young, J. C., Moarefi, I. & Hartl, F. U. Hsp90: A specialized but essential protein-folding tool. J. Cell. Biol. 154, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200104079 (2001).

Oksala, N. K. J. et al. Natural thermal adaptation increases heat shock protein levels and decreases oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 3, 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2014.10.003 (2014).

Barat, A., Sahoo, P. K., Kumar, R., Goel, C. & Singh, A. K. Transcriptional response to heat shock in liver of snow trout (Schizothorax richardsonii)—A vulnerable Himalayan Cyprinid fish. Funct. Integr. Genom. 16, 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-016-0477-0 (2016).

Sreedhar, A. S., Kalmár, E., Csermely, P. & Shen, Y-F. Hsp90 isoforms: Functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 562 (1–3), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00229-7 (2004).

Barnes, J. A., Dix, D. J., Collins, B. W., Luft, C. & Allen, J. W. Expression of inducible Hsp70 enhances the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells and protects against the cytotoxic effects of hyperthermia. Cell. Stress Chaperone. 6 (4), 316–325 (2001).

Guo, S. N., Zheng, J. L., Yuan, S. S. & Zhu, Q. L. Effects of heat and cadmium exposure on stress-related responses in the liver of female zebrafish: Heat increases cadmium toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 618, 1363–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.264 (2018).

Mu, W., Wen, H., Li, J. & He, F. Cloning and expression analysis of a HSP70 gene from Korean rockfish (Sebastes Schlegeli). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 35 (4), 1111–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2013.07.022 (2013).

Waheed, R. et al. Thermal stress accelerates mercury chloride toxicity in Oreochromis niloticus via up-regulation of mercury bioaccumula-tion and HSP70 mRNA expression. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 137326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137326 (2020).

Demeke, A. & Tassew, A. Heat shock protein and their significance in fish health. Res. Rev. J. Vet. Sci. 2 (1), 66–75 (2016).

Pockley, A. G. Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. Lancet 362, 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14075-5 (2003).

Jing, Z. et al. Effects of chronic heat stress on kidney damage, apoptosis, inflammation, and heat shock proteins of Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii). Animals 13, 3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233733 (2023).

Shi, H. N. et al. Effect of heat stress on heat-shock protein (Hsp60) mRNA expression in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (2), 5280–5286 (2015).

Martin, J., Horwich, A. L. & Hartl, F. U. Prevention of protein denaturation under heat stress by the chaperonin Hsp60. Science 258, 995–998. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1359644 (1992).

Ohashi, K., Burkart, V., Flohè, S. & Kolb, H. Cutting edge: Heat shock protein 60 is a putative endogenous ligand of the toll-like receptor-4 complex. J. Immunol. 164 (2), 558–561. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.558 (2000).

Choresh, O., Ron, E. & Loya, Y. The 60-kDa heat shock protein (HSP60) of the sea anemone Anemonia viridis: A potential early warning system for environmental changes. Mar. Biotechnol. 3, 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-001-0007-4 (2001).

Mahanty, A., Purohit, G. K., Mohanty, S. & Mohanty, B. P. Heat stress–induced alterations in the expression of genes associated with gonadal integrity of the teleost Puntius sophore. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 45, 1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-019-00643-4 (2019).

Jahan, K., Nie, H. & Yan, X. Revealing the potential regulatory relationship between HSP70, HSP90 and HSF genes under temperature stress. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 134, 108607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108607 (2023).

Rangaswamy, B., Kim, W. S. & Kwak, I. S. Heat shock protein 70 reflected the state of inhabited fish response to water quality within lake ecosystem. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-04971-0 (2024). 643 – 54.

Murtha, J. M. & Keller, E. T. Characterization of the heat shock response in mature zebrafish (Danio rerio). Exp. Gerontol. 38, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5565(03)00067-6 (2003).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of heat stress on respiratory burst, oxidative damage and SERPINH1 (HSP47) mRNA expression in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 42, 701–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-015-0170-6 (2016).

Akbarzadeh, A. et al. Developing specific molecular biomarkers for thermal stress in salmonids. BMC Genom. 19, 749. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5108-9 (2018).

Hori, T. S. et al. Heat-shock responsive genes identified and validated in Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) liver, head kidney and skeletal muscle using genomic techniques. BMC Genom. 11, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-72 (2010).

Ciocca, D. R., Oesterreich, S., Chamness, G. C., McGuire, W. L. & Fuqua, S. A. W. Biological and clinical implications of heat shock protein 27,000 (Hsp27): A review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85, 1558–1570. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.19.1558 (1993).

Li, P., Li, Z. H. & Wu, Y. Interactive effects of temperature and mercury exposure on the stress-related responses in the freshwater fish Ctenopharyngodon idella. Aquac Res. 52 (5), 2070–2077. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15058 (2021).

Ishida, Y. & Nagata, K. Hsp47 as a collagen-specific molecular chaperone. In Methods in Enzymology 499, 167–182, (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386471-0.00009-2 (Academic Press,.

Smith, T. R., Tremblay, G. C. & Bradley, T. M. Characterization of the heat shock protein response of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 20, 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007743329892 (1999).

Nakamoto, H. & Vígh, L. The small heat shock proteins and their clients. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64 (3), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-006-6321-2 (2007).

Heikkila, J. J. The expression and function of hsp30-like small heat shock protein genes in amphibians, birds, fish, and reptiles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Amp. Integr. Physiol. 203, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.09.011 (2017).

Zarate, J. & Bradley, T. M. Heat shock proteins are not sensitive indicators of hatchery stress in salmon. Aquaculture 223, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00160-1 (2003).

Liu, X., Shi, H., Liu, Z., Wang, J. & Huang, J. Effect of heat stress on heat shock protein 30 (Hsp30) mRNA expression in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Turkish J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 19 (8), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.4194/1303-2712-v19_8_06 (2019).

Wang, Y., Xu, J., Sheng, L. & Zheng, Y. Field and laboratory investigations of the thermal influence on tissue-specific Hsp70 levels in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 148, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.009 (2007).

Bildik, A., Asıcı Ekren, G., Akdeniz, G. & Kıral, F. Effect of environmental temperature on heat shock proteins (HSP30, HSP70, HSP90) and IGF-I mRNA expression in Sparus aurata. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 18 (4), 1014–1024. https://doi.org/10.22092/ijfs.2018.116979 (2019).

Quinn, N. L., McGowan, C. R., Cooper, G. A., Koop, B. F. & Davidson, W. S. Identification of genes associated with heat tolerance in Arctic Charr exposed to acute thermal stress. Physiol. Genomics. 43, 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00008.2011 (2011).

Chen, W., Zhang, M., Luo, X., Zhang, Z. & Hu, X. Molecular characterization of heat shock protein 20 (hsp20) in goldfish (Carassius auratus) and expression analysis in response to environmental stresses. Aquac. Rep. 24, 101106, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101106 (2022).

Wan, Q., Whang, I. & Lee, J. Molecular and functional characterization of HdHSP20: A biomarker of environmental stresses in disk abalone Haliotis discus discus. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 33, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2012.03.034 (2012).

Morrow, G. & Tanguay, R. M. Small heat shock protein expression and functions during development. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. boil. 44 (10), 1613–1621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2012.03.009 (2012).

Pierre, S. et al. Cloning of Wap65 in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and sea bream (Sparus aurata) and expression in sea bass tissues. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 155, 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.01.002 (2010).

Cho, Y. S., Kim, B. S., Kim, D. S. & Nam, Y. K. Modulation of warm-temperature-acclimation-associated 65-kDa protein genes (Wap65-1 and Wap65-2) in mud loach (Misgurnus mizolepis, Cypriniformes) liver in response to different stimulatory treatments. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 32 (5), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2012.01.009 (2012).

Li, C. H. & Chen, J. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of a novel wap65-1 gene from Plecoglossus altivelis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 165 (2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpb.2013.03.014 (2013).

Díaz-Rosales, P., Pereiro, P., Figueras, A., Novoa, B. & Dios, S. The warm temperature acclimation protein (Wap65) has an important role in the inflammatory response of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 41 (1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2014.04.012 (2014).

Hirayama, M., Kobiyama, A., Kinoshita, S. & Watabe, S. The occurrence of two types of hemopexin-like protein in medaka and differences in their affinity to heme. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00897 (2004).

Kondera, E. Haematopoiesis and haematopoietic organs in fish. Anim. Sci. Genet. 15 (1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0013.4535 (2019).

Kikuchi, K., Watabe, S. & Aida, K. The Wap65 gene expression of goldfish (Carassius auratus) in association with warm water temperature as well as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 17, 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007768531655 (1997).

Sha, Z. et al. The warm temperature acclimation protein Wap65 as an immune response gene: Its duplicates are differentially regulated by temperature and bacterial infections. Mol. Immunol. 45, 1458–1469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2007.08.012 (2008).

Komoroske, L. M., Connon, R. E., Jeffries, K. M. & Fangue, N. A. Linking transcriptional responses to organismal tolerance reveals mechanisms of thermal sensitivity in a mesothermal endangered fish. Mol. Ecol. 24 (19), 4960–4981. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13373 (2015).

Yeh, C. W., Kao, S. H., Cheng, Y. C. & Hsu, L. S. Knockdown of cyclin-dependent kinase 10 (cdk10) gene impairs neural progenitor survival via modulation of raf1a gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 288 (39), 27927–27939. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.420265 (2013).

Buckley, B. A., Place, S. P. & Hofmann, G. E. Regulation of heat shock genes in isolated hepatocytes from an Antarctic fish, Trematomus bernacchii. J. Exp. Biol. 207 (21), 3649–3656. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01219 (2004).

Mishra, S. K., Jain, S., Salunke, P. & Sahany, S. Past and future climate change over the Himalaya–Tibetan Highland: Inferences from APHRODITE and NEX-GDDP data. Clim. Change. 156, 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02473-y (2019).

Kubista, M. et al. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Asp Med. 27, 95–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2005.12.007 (2006).

Bustin, S. A. et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55 (4), 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 (2009).

Xie, F., Wang, J. & Zhang, B. RefFinder: A web-based tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 23, 125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-023-01055-7 (2023).

Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 (9). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 (2001). e45-e45.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their thanks to all the contractual staff for their help in the maintenance of the experimental unit. The present work is an output of the Ph.D. research work carried out under the ICAR-DCFR institutional project AQ-18 C/SP-3. This work was supported by grants from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research. We also sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks, which immensely helped improve the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. performed the laboratory work, draft manuscript preparation, data analysis. S.A. co-supervision, conceptualization, methodology, reviewing and editing. O.S.B. supervision, reviewing and editing. C. S. experimental design, data analysis. P.K.P. project resources. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

For the care and use of animals during the study, all applicable international, national and institutional norms were followed. The protocols for fish maintenance, handling, and sacrifice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (DCFR/IACUC/2020/3842-48).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, A., Ali, S., Brraich, O.S. et al. State of thermal tolerance in an endangered himalayan fish Tor putitora revealed by expression modulation in environmental stress related genes. Sci Rep 15, 5025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89772-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89772-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A meta-analysis of public RNA-Seq data identifies conserved stress responses in rainbow trout

BMC Genomics (2025)

-

From heat stress to recovery: proteomic insights into endangered Brachymystax tsinlingensis survival strategies and the ameliorative effects of anti-stress additives

Stress Biology (2025)

-

Aquatic Ecosystem, Fish Diversity and Conservation Strategies of the Fragile Eastern Himalayas: A Comprehensive Review with a Focus on Loktak Lake

Wetlands (2025)