Abstract

The dimensional accuracy of digitally processed inlays is often questioned because of inherent manufacturing inconsistencies associated with computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM). This study aimed to compare the absolute marginal discrepancy (AMD), marginal gap (MG), internal gap (IG), and overall discrepancy (OD) of three-dimensional (3D) printed, milled and conventional inlays. Forty resin dies were 3D-printed from a class II mesiococclusodistal preparation on a typodont and randomly distributed into four groups of 10 each. Optical impressions were taken for three groups to fabricate CAD/CAM inlays: Group PVC, 3D printed VarseoSmile Crownplus; Group PVT, 3D printed VarseoSmile TriniQ; and Group MVE, milled using Vita Enamic. For Group CGP (control), CGP was conventionally fabricated using Gradia Plus. These inlays were stabilized on dies and subjected to cone‒beam computed tomography to measure discrepancies in mesiodistal and buccolingual sectional images. All the discrepancies differed significantly among the groups (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). The mean OD was significantly greater in the MVE than in the PVT and CGP; the mean AMD and MG were significantly greater in the PVC than in the PVT (Tukey test, P > 0.05). Compared with the other groups, the 3D-printed inlays, especially the VarseoSmile TriniQ, presented a closer marginal and internal fit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indirect composite restorations gain advantages over direct composite restorations by minimizing polymerization shrinkage stresses, which may negatively impact the long-term prognosis of teeth by causing additional stress within the remaining walls of the cavity1. Therefore, dentists prefer indirect restoration of medium-to-large intracoronal cavities despite the lack of significant difference in their lifespan from that of their direct counterparts2.

The dimensional accuracy in the form of internal and marginal adaptation is one of the criteria that determines how long an indirect restoration lasts3. Inadequate marginal adaptation may result in luting cement disintegration and eventually microleakage, bacterial infiltration, hypersensitivity, secondary caries, gingival irritation and periodontal disease4,5. Furthermore, inadequate internal fit can lead to poor marginal fit, thicken luting cement, reduce retention, impact occlusion, and negatively affect the restoration’s ability to withstand fracture5,6. The space between the edge of the restoration and the preparation line is known as the marginal gap (MG), whereas the space between the interior of the inlay and the dental structure is known as the internal gap (IG)7. In addition, absolute marginal discrepancy (AMD) is the angular combination of MG and extension errors8, which may be either overextended or underextended, leading to plaque accumulation or microleakage, respectively.

Notably, composite restorations fabricated via subtractive manufacturing of computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology are considered long-standing restorations because of their high fracture resistance9. However, the adaptation of inlay restorations may be hampered in some areas by scanning inaccuracies due to the complex design of tooth preparation compared with that of crowns10. Microcrack formation during the milling process is one of the downsides of milled restorations11. More recently, additive manufacturing using three-dimensional (3D) printing technology has been introduced for the fabrication of inlays and onlays12,13. Unlike subtractive or traditional manufacturing, this technology decreases material waste, instrument wear, and human error without increasing production time14,15. Despite the fact that printed restorations appear to have a better dimensional fit13,16, the subtraction method remains the gold standard for computer-aided manufacturing, as it is possible to mill a wide range of materials from soft wax to hard metals11.

The commonly used materials in the digital workflow of indirect partial restorations are dental ceramics, hybrid materials, and composites12. Hybrid composite materials are desirable substitutes for dental ceramics because of their favorable optical and mechanical characteristics, decreased fracture, and ease of fabrication, cementation, and repair12,17. Recent developments in materials science have made it possible for commercially available ceramic fillers to strengthen temporary resin materials and enhance their mechanical, biological and physical properties to the point where they can be utilized as definitive restorations18,19.

Vita Enamic (Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany) is a polymer-infiltrated ceramic network hybrid composite material introduced for chairside CAD/CAM restorations20. VarseoSmile Crownplus (Bego, Bremen, Germany) is a ceramic-filled hybrid composite material for 3D printing of inlays, onlays and veneers that was introduced in the year 202021. The IG and MG contents of 3D-printed onlays made with this material were found to be lower than those of milled products12. Recently, VarseoSmile TriniQ (Bego), a hybrid composite material, was introduced by the same manufacturer, expanding its scope to include permanent bridges and extensive temporaries22. Daghrery et al. investigated the surface properties and dimensional accuracy of dental laminate veneers made from the above-mentioned materials using the 3D printing method in comparison with the milling method23,24. However, there is limited evidence regarding the dimensional accuracy and other characteristics of 3D-printed inlays compared with other manufacturing methods, such as milling and conventional laboratory fabrication. Moreover, there is a need to compare the recently introduced VarseoSmile TriniQ with the existing VarseoSmile Crownplus for their dimensional accuracy as long-term clinical studies don’t exist.

Therefore, this study aimed to compare the absolute marginal discrepancy, marginal gap, internal gap, and overall discrepancy between the cavity walls and the intaglio surface of 3D-printed inlays using two types of hybrid resin composite materials of different composition with those of milled inlays. The proposed null hypothesis was that there would be no significant difference in the AMD, MG, IG, or OD of the inlays due to either the fabrication method (additive/subtractive) or the composition of the material. The alternate hypothesis tested was that there would be a significant difference in the MG and IG of inlays among the groups.

Materials and methods

Sample size

A prior sample size for this study was calculated according to a previous study3. The power = 0.99 was determined with F tests, one-way ANOVA, the fixed effects method, α = 0.05, and β = 0.2. The effect size f = 5.000791 was measured by using common standard deviation in G-power software (version 3.1.9.7; University of Dusseldorf, Germany)25. The final sample size was estimated to be 6 per group, which was rounded to 10 after including a sample failure allowance of 40%, as the fabrication methods used for the inlays in this study are highly technique sensitive.

Tooth preparation for inlay

A mandibular right first molar typodont (Standard Model AG-3, Frasaco Gmbh, Tettnang, Germany) was prepared under continuous air‒water spray for Class II mesiococclusodistal inlay restoration via a series of recommended diamond burs with a 6° taper (Inlay Preparation Set 4261, Komet, Lemgo, Germany) and a high-speed handpiece (SMART Torque S608C, KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach, Germany). Initially, the occlusal cavity was prepared with a pulp depth and an isthmus width of 2 mm. The proximal box was subsequently prepared with the axial wall measuring 1.5 mm in height and depth and the buccolingual width measuring 3 mm. The dimensions of the cavity were verified with the help of a graduated periodontal probe (Falcon Periodontal Williams probe, Lucca, Italy). The two axial walls on the mesial and distal proximal boxes had a convergence angle of 6° and rounded line angles to avoid undercuts and sharp areas3.

Resin dies

A total of 40 resin dies were digitally replicated from the prepared typodont tooth26. An optical impression of the inlay preparation on the typodont was captured using an intraoral scanner (i700; Medit Corp., Seoul, Korea) to create a virtual CAD file. After the CAD file was imported into a 3D printing machine (MAX UV385; ASIGA, Sydney, Australia), the resin dies were fabricated using a 3D-prinitng resin dedicated for dies (DentaMODEL; ASIGA) and allowed to dry for 10 min after washing in pure isopropyl alcohol. The dies were postcured in a UV postcuring unit (Flash curing chamber; ASIGA) for 20 min in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications and then stored under the same conditions in a dark storage compartment.

Randomization

The prepared resin dies were randomly divided into 4 groups of 10 each on the basis of the method of fabrication as follows: Group PVC, 3D-printed VarseoSmile Crown plus (Bego); Group PVT, 3D-printed VarseoSmile TrinQ (Bego); Group MVE, milled Vita Enamic (Coltene Whaledent, Altstatten, Switzerland); Group CGP (control), conventional layering technique of an indirect composite resin (Gradia plus; GC Europe NV, Leuven, Belgium). The materials used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Digital workflow

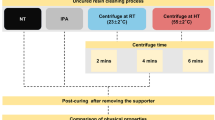

For the PVC, PVT and MVE groups involving digital additive and subtractive manufacturing workflows, the resin dies were scanned using an intraoral scanner (i700; Medit Corp). The 3D images were exported and saved in standard tessellation language (STL) format. CAD of the inlays was performed and analyzed using Exocad software 3.0 (Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) in the PVC and PVT groups, whereas the designed files were analyzed using the 3Shape Dental system (version 2020, 3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) in the MVE group. The cement spacer was set to 40 μm, whereas all other parameters were set to 0 μm starting from 1 mm from all the cavosurface margins. The sequence of procedures performed is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Groups PVC and PVT

The data in the STL file format were transferred to a digital light processing (DLP) printer (Varseo XS; Bego), and the respective permanent restorative resin in liquid form was used. The inlays were printed at a 405 nm wavelength, 50 μm resolution (X, Y, and Z), and 0.25 mm/min printing speed. All samples were created simultaneously at a constant room temperature of 23 °C to reduce procedural variability. The printer was previously calibrated following the manufacturer’s guidelines. After the printing procedure was complete, a spatula was used to carefully remove the restorations from the printing platform. The collected samples were cleaned for 480 s in an ultrasonic bath (Foshan Adelson Medical Devices Co., Foshan, China) containing 96% ethanol solution to remove the residual unpolymerized resin (PanReac AppliChem ITW Reagents, Darmstadt, Germany), after which they were gently dried. The restorations were placed in an Otoflash light curing device (Bego) for postcuring. The samples were exposed to 1500 flashes per second at 10 Hz in a nitrogen gas environment (1.0–1.2 bar). Later, the restorations were turned over to repeat the postcuring procedure on the opposite side of the restoration.

Group MVE

A CEREC inLab MC XL (Dentsply Sirona; Charlotte, NC, USA) wet milling and grinding unit fitted with a water-cooled rotary bur of sizes 1 and 2.5 mm was used for inlay fabrication. The milling parameters were chosen following the manufacturer’s guidelines. After being steamjet cleaned, all of the inlays were allowed to air dry. After the removal of the sprue, the inlays were tried, and minor adjustments were made to smooth the restoration as needed. These samples were inspected for manufacturing flaws prior to the seating process.

Group CGP (control)

A separating medium (Die lube; Dentsply Sirona) was applied to the cavity inner and outer walls to make separation easier. Three layers of die spacer were applied to a thickness ≈ of 40 μm27. Multiple increments of high-strength nanohybrid indirect RCs (Gradia plus, GC Europe NV) of 1–2 mm thickness was adapted to the internal walls of the cavity and polymerized using a light curing unit (Labolight DUO; GC Europe NV). Following the buildup and morphological contouring, the final layer was light-cured for 3 min under a coat of Gradia plus air barrier (GC Europe NV), which was subsequently washed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the prepared restorations were postcured in an Otoflash (Bego) device (1500 flashes × 2 sides), as mentioned above.

Measurement of discrepancies

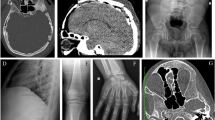

Every inlay was cleansed using ultrasonic baths, allowed to air dry, and then firmly stabilized onto the resin dies using temporary adhesive tape to avoid dislodgement during the imaging procedure. Kodak 9500 cone beam 3D (Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY, USA) equipment was used to create cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images of the resin die-inlay assembly28. The technical specifications of the CBCT scan were an 18 cm by 20 cm field of view, a 10.8 s exposure time (pulsed), a tube voltage between 60 and 90 kV, a 2 to 15 mA (pulsated mode), and a 0.25 mm slice thickness.

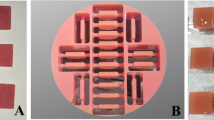

The inlay resin assemblies of each group were arranged in a semicircular configuration using a base former and was positioned on the occlusal plate of the CBCT scanner. The assemblies were aligned with the coronal and sagittal planes to obtain an accurate section; three consecutive sections (Fig. 2A) at the middle of each restoration in both directions (mesiodistal and buccolingual) were selected28,29. Gap measurements were measured at 7 locations (Fig. 2B; MGB – marginal gap buccal, k-o and MGL – marginal gap lingual) for the coronal section (buccolingual) and at 12 locations (Fig. 2C; MGM – marginal gap mesial, a-j and MGD – marginal gap distal) for each sagittal section (mesiodistal). In addition to the above measurements, AMD was also measured (Fig. 2D) at the buccal, lingual, mesial and distal cavosurface margins (4 measurements). Linear measurements were obtained between the restoration and the die at specific points (Fig. 3) for each section using Kodak Dental Imaging’s 3D module (version 2.4; Carestream Health, Inc.) software from the CBCT images. A total of 69 [(12 + 7 + 4) × 3 sections] measurements were recorded per sample via Excel worksheet software (Microsoft Excel 2019; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). All the values at each point for a given sample were retrieved by calculating the average of the respective values from the three consecutive sections. The IG of a sample was obtained by calculating the average of internal points (a-o). Similarly, the MG and AMD of a sample were obtained from the average of four values of different cavosurface margins (mesial, distal, buccal, and lingual). Individual readings were also recorded for the AMD and MG in relation to the mesial, distal, buccal and lingual cavosurface margins. Finally, the overall discrepancy (OD) of a sample was calculated as the mean of all 69 measurements recorded. All the readings were measured by a single examiner (T.S.V.) who has 10 years of experience in handling CBCT.

Schematic representation of the measurement protocol. (A) Lines 1, 2, and 3 denote buccolingual sections, and lines 4, 5, and 6 denote mesiodistal sections. (B) 3D view of measurement points in the buccolingual slices. (C) Measurement points in the mesiodistal slices. (D) Magnified view of the green square in image C showing AMD and MG.

Statistical analysis

The statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) was used to analyze all of the data. For descriptive statistics, the mean and standard deviation were used for continuous variables. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine the interaction impact among the measurements (AMD, MG, and IG) and the manufacturing methods (PVC, PVT, MVE, and CGP). Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the relationships between the variables (AMD, MG, and IG) within a group. The level of significance was considered at P > 0.05.

Results

The results of the present study revealed that the intergroup comparisons of AMD, MG, IG, and OD among the groups differed significantly (one-way ANOVA; P > 0.05) in each of the assessed discrepancies (Table 2). The AMD of MVE was the highest (0.48 ± 0.06), whereas that of CGP (0.25 ± 0.13) was the lowest (Fig. 4). The MVE had the highest OD (0.34 ± 0.04), and the CGP had the lowest (0.15 ± 0.04). Table 3 shows the results of the intergroup comparisons of AMD and MG in relation to the four cavosurface margins. All four groups differed significantly (one-way ANOVA; P > 0.05) in the AMD and MG across the different cavosurface margins. The mesial margins of MVE had the highest AMD (0.62 ± 0.13), and the lingual margins of PVT (0.05 ± 0.05) had the lowest AMD. The mesial margins of MVE had the highest value (0.46 ± 0.08) for MG, and the buccal margins of PVT & CGP (0.02 ± 0.06) had the lowest.

The mean AMD and MG values in relation to the mesial and distal margins were generally greater than those of the buccal and lingual cavosurface margins (Figs. 5 and 6). Pairwise comparisons among MG, AMD, and IG revealed positive correlations between MG and IG in the PVC (r = 0.786) and between MG and AMD in the PVT (r = 0.675). Intragroup comparisons of AMD, MG, and IG revealed significant differences among the three variables across all the groups.

The MVE was the highest of all the groups, and the AMD was the highest of the three discrepancies (Supplementary Table S1). Intragroup comparisons of individual cavosurfaces for AMD and MG revealed significant differences among the four cavosurface margins in all the groups except for the CGP (repeated-measures ANOVA; P > 0.05). The AMD and MG of the CGP were similar across the different cavosurface margins (Supplementary Table S2). The mean values of each measurement point were calculated from all 240 CBCT images and are presented as a diagram for comparison (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Discussion

Several 3D printing methods are commonly used in dentistry, including stereolithography, selective laser sintering, selective laser melting, and digital light processing (DLP)30. The DLP used in this study is more widely used because of its high printing speed, tiny equipment size, exceptional cost-effectiveness, capacity to produce high-resolution, and complex outputs13,31. The precision of the milling machine, the size and wear of the rotating instruments, the geometry of the restoration, the type of material, the assessment technique, and the quantity of measurement sites can affect the fit accuracy of milled restorations32,33,34. The time consumed by the digital chairside workflow of milled restorations was reported to be less than that of the conventional workflow35.

The materials tested were ceramic-reinforced hybrid materials intended for use as definitive restorations19. Using a 3D printer, the typodont preparation was replicated into multiple printed resin dies. The use of similar 3D-printed dies for all the groups minimizes extra errors that could arise from operator’s skills as well as nonadditive multiplication techniques. Since the i700 (Medit) lacked a milling system, it was utilized only during the impression stage. The design and production stages were carried out through different systems. A single optical impression was made for the digitally processed inlays, as this approach would avoid the formation of undercuts with several optical impressions of the preparation. The presence of these undercuts would not have allowed the inlays to be inserted into the cavity36.

Various noninvasive methods to measure the MG and IG of inlays include the replica technique, microcomputed tomography (CT), and CBCT13,28,37. The downside of the replica technique is the tendency toward damage to silicone impressions and poor delineation of margins for measurement. CBCT has advantages over high-resolution microcomputed tomography because of the low radiation dose for patients38, and it is a frequently used investigatory tool in dentistry for multiple purposes. AMD was measured and evaluated in addition to MG and IG to obtain information on positive or negative overhangs, which is crucial for the clinical performance of inlays29. All the inlay samples evaluated in this study had only positive overhangs.

There have been reports of marginal and internal gap values for several indirect composite and ceramic inlays that range from 48 to 278 μm13,36,39. Nonetheless, the clinically acceptable recommended marginal adaptation for inlays should be less than 120 μm4. It has been demonstrated that a precise fitting restoration is necessary for long-term success, even though resin luting cement at the edges of the restoration can compensate for deficient inlay adaptation29. In this study, a luting space of 40 μm was set, but the obtained values for gaps and discrepancies were in the range of 0.05–0.48 mm (50–480 μm). The wide range in values could be partially attributed to the absence of cementation, the resolution of the images by the CBCT, and the error tolerance of the measurement software.

The null hypothesis that there is no significant difference among the groups of different manufacturing methods/materials was completely rejected. The results of the present study revealed a statistically significant difference in all the variables (gaps) tested among the groups (P > 0.05). With respect to the two printed groups, the MG and AMD were significantly different (P > 0.05), whereas this was not the case for the IG and OD. However, the values are clinically significant, meaning that the PVT was superior in dimensional accuracy and fit compared with the PVC. The probable reason for this behavior could be the variation in the composition of the material, which is not explained by the manufacturer. The manufacturing methods apparently played a significant role in influencing the dimensional accuracy of the inlays. The mean values were significantly higher (P > 0.05) for the milled inlays (MVE) than for the printed (PVC, PVT) and conventional inlays (CGP). This is in partial agreement with a previous study that compared the MG and IG of 3D-printed composites, milled composites, milled ceramics and conventional composite inlays measured using the replica technique13. These observations revealed the superior performance of the 3D-printed inlays compared with the conventional inlay group. However, the mean gaps of conventional inlays were always minimal compared with those of the other groups in our study. Notably, the mean MG (50 μm) of CGP was well within the recommended range of less than 120 μm. This partial disagreement could be attributed to the difference in measurement tools employed in the studies. Moreover, the current study confirms earlier research showing that 3D-printed restorations have a greater internal fit than those milled from resin blocks16,26. This could be attributed to the difference in the manufacturing parameters used between the additive and subtractive techniques.

Suksuphan et al.26 compared AMD and MG at different surfaces of 3D-printed and milled crowns and reported significant differences. Similarly, the AMD and MG in the mesial and distal cavosurface margins in our study were greater than those in the buccal and lingual margins in all the printed and milled groups except the CGP group. This could be attributed to either the missing details in the optical impression or other manufacturing parameters that influence the digital fabrication of inlays.

Strengths

This study tested 3D-printed ceramic-reinforced hybrid composite inlays, which are less expensive in terms of equipment and consumable cost than milled resin composites and milled lithium disilicate ceramics40. The production time is shorter, especially when more than 8 restorations are fabricated40, which saves the effective chairside time of the patient. Concomitantly, the printed inlay can be repaired outside the patient’s mouth to improve its adaptation, saves material wastage and reprinting time21. Moreover, the CBCT used in this study is a noninvasive in vivo method for evaluating the dimensional accuracy of restorations28, whereas microcomputed tomography is an in vitro measurement tool; hence, the results obtained in this study may be scrupulously translated to the clinical setting.

Limitations

The first limitation is that the intrinsic precision of manufacturing methods in combination with the tested material in measuring the MG and IG of inlays could not be determined without the additional effect of the luting cement (viscosity and seating force). A definitive luting cement mimics the clinical situation while assessing the trueness and fit of the restoration41. Therefore, in the majority of research designs, a precementation and postcementation evaluation for marginal and internal gaps would be more appropriate and helpful27. The second limitation was the challenge faced in optimizing the contrast of resin dies in the CBCT images while differentiating the margins at the gap. The third limitation is the inability to accurately standardize the thickness of the die spacer to 40 μm in the CGP group. The fourth limitation is the use of different digital imaging methods, design software and restoration materials in fabricating the inlays. Hence, the results of this study should be interpreted carefully when comparing the inlays made using additive and subtractive manufacturing techniques.

Further investigations are needed, as it is crucial to test the mechanical properties of such novel materials using the fundamental tests outlined by the ISO, such as fracture resistance, flexural strength, and modulus tests. Different cavity dimensions can also be compared to evaluate the effects of variations in the thickness of a material on its mechanical properties.

Conclusion

Under the given testing conditions and limitations, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

1.

Compared with milled inlays, the quality of the 3D-printed inlays tested had exceptional dimensional accuracy, which likely extends the clinical lifespan of such restorations.

-

2.

Compared with the VarseoSmile Crownplus, the VarseoSmile TriniQ showed superior marginal adaptation.

-

3.

The dimensions of Vita Enamic inlays showed poor adaptation with the prepared walls of the resin die, underscoring its inefficiency.

-

4.

The 3D-printed inlays using VarseoSmile TriniQ could be a potential treatment option for the clinicians, provided additional long term in vivo investigations are performed in future.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three–dimensional

- AMD:

-

Absolute marginal discrepancy

- CBCT:

-

Cone–beam computed tomography

- IG:

-

Internal Gap

- MG:

-

Marginal Gap

- OD:

-

Overall discrepancy

References

Dejak, B. & Młotkowski, A. A. Comparison of stresses in molar teeth restored with inlays and Direct restorations, including polymerization shrinkage of composite resin and tooth loading during mastication. Dent. Mater. 31, e77–e87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2014.11.016 (2015).

Opdam, N. J. M. et al. Longevity of posterior composite restorations. J. Dent. Res. 93, 943–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514544217 (2014).

Toma, F. R., Moleriu, L. C. & Porojan, L. Micro-CT marginal and internal fit evaluation of CAD/CAM high-performance polymer onlay restorations. Polymers (Basel) 15, 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15071715 (2023).

Park, S. H., Yoo, Y. J., Shin, Y. J., Cho, B. H. & Baek, S. H. Marginal and internal fit of nano-composite CAD/CAM restorations. Restor. Dent. Endod. 41, 37. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2016.41.1.37 (2016).

Uzgur, R. et al. Cement thickness of inlay restorations made of lithium disilicate, polymer-infiltrated ceramic and nano‐ceramic CAD/CAM materials evaluated using 3D X‐Ray micro‐computed tomography. J. Prosthodont. 27, 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.12521 (2018).

Kim, D. Y., Kim, J. H., Kim, H. Y. & Kim, W. C. Comparison and evaluation of marginal and internal gaps in cobalt–chromium alloy copings fabricated using subtractive and additive manufacturing. J. Prosthodont. Res. 62, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2017.05.008 (2018).

Mously, H. A., Finkelman, M., Zandparsa, R. & Hirayama, H. Marginal and internal adaptation of ceramic crown restorations fabricated with CAD/CAM technology and the heat-press technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 112, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.03.017 (2014).

An, S., Kim, S., Choi, H., Lee, J. H. & Moon, H. S. Evaluating the marginal fit of zirconia copings with digital impressions with an intraoral digital scanner. J. Prosthet. Dent. 112, 1171–1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.12.024 (2014).

Taha, D. et al. Fracture resistance and failure modes of polymer infiltrated ceramic endocrown restorations with variations in margin design and occlusal thickness. J. Prosthodont. Res. 62, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2017.11.003 (2018).

Kirsch, C., Ender, A., Attin, T. & Mehl, A. Trueness of four different milling procedures used in dental CAD/CAM systems. Clin. Oral Investig. 21, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1916-y (2017).

Bae, E. J., Jeong, I. D., Kim, W. C. & Kim, J. H. A comparative study of additive and subtractive manufacturing for dental restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 118, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.11.004 (2017).

Cantó-Navés, O. et al. In Vitro Comparison of internal and marginal adaptation between printed and milled onlays. Materials (Basel) 16, 6962. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16216962 (2023).

Lim, Y. A., Kim, J. M., Choi, Y. & Park, S. Evaluation of fitness and accuracy of milled and three-dimensionally printed inlays. Eur. J. Dent. 17, 1029–1036. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1758796 (2023).

Della Bona, A., Cantelli, V., Britto, V. T., Collares, K. F. & Stansbury, J. W. 3D printing restorative materials using a stereolithographic technique: a systematic review. Dent. Mater. 37, 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2020.11.030 (2021).

Espinar, C., Della Bona, A., Tejada-Casado, M., Pulgar, R. & Pérez, M. M. Optical behavior of 3D-printed dental restorative resins: Influence of thickness and printing angle. Dent. Mater. 39, 894–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2023.08.003 (2023).

Ahlholm, P., Sipilä, K., Tarvonen, P. L., Silvast, T. & Lappalainen, R. Accuracy of dental restorations fabricated using milling vs 3D-printed molds: a pilot study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 37, S78–S88. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.8236 (2024).

Ruse, N. D. & Sadoun, M. J. Resin-composite blocks for dental CAD/CAM applications. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1232–1234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514553976 (2014).

Alshamrani, A., Alhotan, A., Owais, A. & Ellakwa, A. The clinical potential of 3D-printed crowns reinforced with zirconia and glass silica microfillers. J. Funct. Biomater. 14, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14050267 (2023).

Sabatini, G. P. et al. Additive manufacturing trueness and internal fit of crowns in resin modified with a commercially available ceramic composite concentrate. J. Prosthet. Dent. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2024.09.005 (2024).

Yildirim, G., Uzun, I. H. & Keles, A. Evaluation of marginal and internal adaptation of hybrid and nanoceramic systems with microcomputed tomography: an in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 118, 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.11.005 (2017).

Bego VarseoSmile Crown Plus Available online. November (2024). https://www.bego.com/3d-printing/materials/varseosmile-crown-plus/ (accessed on 18.

Bego VarseoSmile TriniQ. – One for all. https://www.bego.com/3d-printing/materials/varseosmile-triniq/ [Accessed on 18 November 2024].

Daghrery, A. et al. Marginal discrepancy and internal fit of 3D-printed versus milled laminate veneers: an in vitro study. J. Funct. Biomater. 15, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15110338 (2024).

Daghrery, A. & Color stability gloss retention, and surface roughness of 3D-Printed versus Indirect prefabricated veneers. J. Funct. Biomater. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14100492 (2023).

Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J. Educ. Eval Health Prof. 18 https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17 (2021).

Suksuphan, P., Krajangta, N., Didron, P. P., Wasanapiarnpong, T. & Rakmanee, T. Marginal adaptation and fracture resistance of milled and 3D-Printed CAD/CAM hybrid dental crown materials with various occlusal thicknesses. J. Prosthodont. Res. 68, JPRD2300089. https://doi.org/10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_23_00089 (2023).

Aditya, P., Madhav, V. N. V., Bhide, S. V. & Aditya, A. Marginal discrepancy as affected by selective placement of die-spacer: an in vitro study. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 12, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13191-012-0119-8 (2012).

Ibrahim, S. H., Amr, H., Hassan, A. A. & Elzohairy, A. Internal fit evaluation of indirect restorations fabricated from CAD/CAM composite blocks versus ceramic blocks in badly broken teeth using cone beam CT (CBCT): double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Heliyon 8, e09466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09466 (2022).

Baig, M. R., Akbar, A. A., Sabti, M. Y. & Behbehani, Z. Evaluation of marginal and internal fit of a CAD/CAM monolithic zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate porcelain laminate veneer system. J. Prosthodont. 31, 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13438 (2022).

Park, S., Park, J., Kim, S., Heo, S. & Koak, J. Oung flexural strength of 3D-printing resin materials for provisional fixed dental prostheses. Materials (Basel) 13, 3970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13183970 (2020).

Reymus, M. et al. Fracture load of 3D-Printed fixed dental prostheses compared with milled and conventionally fabricated ones: the impact of resin material, build direction, post-curing, and artificial aging—an in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 24, 701–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-02952-7 (2020).

Abduo, J., Lyons, K. & Bennamoun, M. Trends in computer-aided manufacturing in prosthodontics: a review of the available streams. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/783948 (2014).

Nawafleh, N. A., Mack, F., Evans, J., Mackay, J. & Hatamleh, M. M. Accuracy and reliability of methods to measure marginal adaptation of crowns and FDPs: a literature review. J. Prosthodont. 22, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.12006 (2013).

Chu, J., Bennani, V., Aarts, J., Chandler, N. & Lowe, B. The effect of different geometric shapes and angles on the fracture strength of IPS e.Max computer-aided designed ceramic onlays: an in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 21, 210. https://doi.org/10.4103/JCD.JCD_242_17 (2018).

Stromeyer, S., Wiedemeier, D., Mehl, A. & Ender, A. Time efficiency of digitally and conventionally produced single-unit restorations. Dent. J. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9060062 (2021).

Zaruba, M. et al. Marginal adaptation of ceramic and composite inlays in minimally invasive mod cavities. Clin. Oral Investig. 18, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-013-0988-1 (2014).

Alajaji, N. K., Bardwell, D., Finkelman, M. & Ali, A. Micro-CT evaluation of ceramic inlays: comparison of the marginal and internal fit of five and three Axis CAM systems with a heat press technique. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 29, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12271 (2017).

Liang, X. et al. Comparison of micro-CT and cone beam CT on the feasibility of assessing trabecular structures in mandibular condyle. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 46, 20160435. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20160435 (2017).

Bayrak, A., Akat, B., Ocak, M., Kιlιçarslan, M. A. & Özcan, M. Micro-computed tomography analysis of fit of ceramic inlays produced with different CAD software programs. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 29 https://doi.org/10.1922/EJPRD_2046Bayrak06 (2021).

Daher, R., Ardu, S., di Bella, E., Krejci, I. & Duc, O. Efficiency of 3D printed composite resin restorations compared with subtractive materials: evaluation of fatigue behavior, cost, and time of production. J. Prosthet. Dent. 131, 943–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2022.08.001 (2024).

Contrepois, M., Soenen, A., Bartala, M. & Laviole, O. Marginal adaptation of ceramic crowns: a systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 110, 447–454e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.08.003 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and T.S.V.; methodology, A.D.; software, T.S.V.; validation, A.D., T.S.V., W.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, H.M., G.F., R.G., S.A., R.M., W.L. and H.C.; and A.C. investigation, H.M., G.F., R.G., S.A., R.M.; resources, H.M., G.F., R.G., S.A., R.M., W.L.; data curation, A.D. and T.S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., T.S.V., and H.L.; writ-ing—review and editing, A.D.,T.S.V. and W.L; visualization, A.D. and T.S.V., and T.S.V.; supervi-sion, A.D., T.S.V., H.C and A.C.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daghrery, A., Vinothkumar, T.S., Majrashi, H. et al. Dimensional accuracy of additive and subtractive manufactured ceramic-reinforced hybrid composite inlays: a CBCT-based in vitro study. Sci Rep 15, 6048 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90611-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90611-1