Abstract

Tribolium castaneum can inflict significant harm to stored grains. The use of novel, harmless, and effective biopesticides is needful to avoid the hazardous effects of chemical insecticides. On the other hand, saponins are antinutritional metabolites with large biological properties, and quinoa husk is one of the richest biomasses in these compounds. The biocidal and antinutritional effects of a saponin-rich extract (SRE) from Chenopodium quinoa husk were examined against T. castaneum adults by evaluating mortality, nutritional indices, and mortality rate. The effect on T. castaneum’s enzymatic activity was also investigated. As a result, at concentrations above 25 mg/g of SRE, insects can no longer consume flour with a significant feeding deterrent (≥ 84.20%). The study showed that SRE has an acute and long-term effect on insect survival, which confirms that the mortality of T. castaneum is attributable to the toxic action of the saponin extract and not just the starvation action. In addition, SRE demonstrated its capacity to disrupt the wax layer of T. castaneum adults, penetrate insects, and react as oxidative stressors, which explain the affectation of the immune defense system of T. castaneum through the downregulation of phenoloxidase activity and glutathione S-transferase, the upregulation of the antioxidant system presented in this study with catalase activity, and causing organelle damage in the midgut tissues confirmed by the inhibition of amylase activity. According to the findings of this study, saponin extract has a very interesting application as an insecticide against storage insects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A wide range of storage insects pose a threat to stored grain, resulting in quality loss1,2. Noting that cereals, an essential part of the world’s food supply, are typically stored in massive containers where they risk being ravaged by a variety of insects2. T. castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) is one of the most common storage pests with a large global spread that causes harm during seed storage3. On the other hand, the protection of stored products against deterioration caused by this insect depends heavily on the use of chemical pesticides4. The use of synthetic insecticides can lead to significant price increases, pest resurgence and raise the pest resistance to pesticides5. These disadvantages have raised new challenges for crop protection in addition to find an active product against target pests, that can be harmless to humans and the environment6. Over past years, the use of botanical biopesticides as alternatives to conventional pesticides has attracted researchers’ because they improve pest control strategies’ safety while avoiding many of unintended effects4,7. These biopesticides are mainly presented by secondary metabolites as defense mechanisms to combat a variety of biotic and abiotic stressors, among them the triterpenoids saponins7. Saponins are a family of compounds composed of a sapogenin core linked to one or more sugar chain(s)8. These compounds have been shown to have a harmful effect on insects, nematodes, and mollusks while also possessing antibacterial and antioxidant properties9. The saponins insecticide effect can often manifest on insect growth, fertility, and longevity10. Indeed, several action mechanisms of saponins have been demonstrated, including acetylcholine esterase inhibitors, metabolic disruptors, antifeedants, and cell death inducers11. For example, alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) triterpene saponins demonstrated an effective antifeeding activity against pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris.)12 and moths (Ectropis obliqua Prout.)13. In the same vein, tea saponins manifested insecticide activity against corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea Boddie.)10, moths (E. obliqua)14, and diamondback moths (Plutella xylostella L.)15. Abundantly present in the husk of quinoa seeds16, the triterpenoids saponins are considered as antinutritional metabolites because they seize a characteristic bitter and astringent taste, in addition to their detergent and hemolytic properties17. In this regard, their elimination before the consumption of quinoa seeds is a crucial step. At the industrial level, the quinoa husk is mechanically removed from the grains, creating highly valuable residual biomass16,18. To the best of our knowledge, the insecticidal activities of quinoa saponins against storage insects have not yet been studied. So far, few studies have been reported the biocidal properties of saponins extracted from other plants, with limited knowledge on their action mechanism on insects11,17.

In this study, the biocidal effect of the quinoa saponin rich extract was evaluated against T. castaneum adults. The antinutritional and toxicity assessments were carried out by diet and topical assays on T. castaneum. Furthermore, the enzymatic activities of treated insects were investigated to identify the action of saponins on enzymatic systems of T. castaneum adults.

Materials and methods

Insect and plant material

T. castaneum adults were collected from laboratory cultures at Mohamed VI Polytechnic University, Morocco grown in an incubator at dark conditions and maintained at 25 ± 2 °C and 70% relative humidity (RH). Soft wheat flour was used as the culture medium. For the antifeedant bioassay, the adults of T. castaneum were starved 24 h before the experiments. All experiments were carried out at 25 ± 2 °C and 70% RH.

Quinoa husk sample was obtained from Benrim farm, Berrechid, Morocco. To remove the husk from the quinoa grains (Puno genotype), a mechanical grain polisher was used by the quinoa manufacturer. The remaining husk powder was sifted (particle size < 1 mm) before the extraction procedure.

Quinoa saponin rich extract (SRE): extraction and characterization

Extraction procedure

The extraction was started by defatting the quinoa husk powder using Soxhlet with petroleum ether to remove the lipidic fraction. Subsequently, the defatted powder was subjected to two rounds of extraction by maceration for 2 h each, using distilled water as solvent. After centrifugation, the supernatant was treated with an excess of ethanol to precipitate polysaccharides and protein fractions. The saponins are highly soluble in ethanol, which allows their accumulation in the ethanol solution and the formation of a saponin fraction. The solution was then left to precipitate overnight at 4 °C; after that, the ethanol solution was evaporated under vacuum at a temperature of 40 °C and a stirring speed of 200 rpm. After lyophilization at 4 bar and − 50 °C, the extract was recovered and stored at 4 °C until use.

UV-VIS spectrometry

Saponin content was measured spectrophotometrically using the approach applied by Irigoyen & Giner19, with modifications adopted by Mhada et al.20. The optical density was recorded at 528 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™ 840-300300, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The results were expressed in g of saponins referred to Quillaia saponin assay per 100 g of husk powder. All measurements were made in triplicate.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy was used to analyze the composition of the extract. FTIR spectra were collected using the DairyGuard™ (Brenkin Elmer L1280080, USA) throughout the range of wavenumbers spanning from 400 to 4000 cm− 1, corresponding to the spectral region of the mid-infrared (MIR).

Topical application bio-test on T. Castaneum

Bioassay

The topical assay was done according to Baccari et al. method21. Briefly, 4 µL of the SRE aqueous solution was applied on the back of each insect using a micropipette. The doses used were 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/mL. All the doses were prepared from fresh stock solutions obtained by dissolving the SRE powder in distilled water. The control was treated with 4 µL of distilled water. Ten insects per replication, with five replicates, were treated with different SRE concentrations. Mortality was assessed after 24 h of treatment, and insects are considered dead in the absence of any movement of their legs and antenna.

Mortality rate

The percentage of mortality observed in control and treated individuals is estimated by applying the following equation (Eq. (1)):

Post-exposure mortality was corrected using the Sun-Shepard formula for non-uniform populations (Eq. (2))22:

With:

Effective dose estimates (ED)

ED were calculated from the regression line of the Probit corresponding to the percentage of mortality corrected as a function of the logarithms of the applied concentration. To estimate the ED, the Probit table was used.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation

The preparation of insects for SEM observation was done following the modified protocol of Cui et al.13. To this end, 1 µL of 5 mg/mL SRE (non-lethal concentration based on the topic test) was dropped into the back of the T. castaneum adults and 1 µL of distilled water for the control treatment. Then, the insects were adhered to the sample plate with conductive tape and observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, HIROX SH 4000 M, Limonest, France) to examine their surface structure. The SEM was performed at a magnification range of ×80–3000.

Evaluation of the effects of SRE on the diet and nutritional indexes of T. Castaneum

Preparation of the flour disks

The disks were prepared according to the method reported by Napoleão et al.23. In pursuit of this, 200 mg of a mixture containing soft wheat flour and SRE powder was mixed with 1 mL of distilled water. Seven different weight ratios, which correspond to w (SRE): w (soft wheat flour), were prepared and used in this study, i.e., 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/g. The control disks were prepared with soft wheat flour and distilled water without adding SRE powder. Next, 100 µL of the mixture was pulled using a micropipette to prepare disks with 1 cm of diameter, placed at the bottom of a plastic Petri dish, and left in the air overnight at room temperature.

Bioassay

The disks were weighed and placed in a round box (60 mL, Ø 45 × 58) as a food source for ten adults of T. castaneum previously weighed in groups. A group of ten insects was placed in a box without source of food serving as a starved group (S). After 72 h, the meal disks and live insects were reweighed. In order to note the long-term effect of saponins, a follow-up of the weight of the surviving insects was recorded after 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 days. Five replicates were established for each treatment.

Nutritional indexes

The nutritional parameters24 determined are:

Where X and Y are the weight of live insects on the third day (mg) per number of live insects on the third day and the weight of origin of insects (mg) per number of origin of insects.

Where Z is the biomass ingested (mg) per number of insects living on the third day. While the biomass ingested equal initial disk weight minus disk weight on the third day (the variation of weight because of the variation of humidity for each treatment was taken into consideration).

Mortality rate

The mortality follow-up was recorded for 60 days. To distinguish between insect mortality caused solely by toxic action and that caused by a combination of toxic action and starvation action, a group of insects was kept without food under the same conditions. The mortality rate was calculated using Eq. (2).

Antifeedant action

The antifeedant activity was determined as developed by Shekari et al.25. The treated and control disks were placed together in a round box (60 mL, Ø 45 × 58) with 10 insects. Five replicates were prepared for each concentration. The feeding deterrence index (FDI) for each concentration was calculated as follows (Eq. (6)):

Where C and T are the consumption weights of amended and control disk, successively.

Enzymatic activities

Preparation of enzyme extract

To highlight the effect of the saponin rich extract on the enzymatic activities of T. castaneum adults after treatment, live insects in contact and nutritional tests were subjected to enzyme extraction using the protocol of Rajkumar et al.26. To this end, the insects were homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 0.1 M) using a mortar. Then, they were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was stored at -20 °C for further analysis.

Protein content

Protein content was assayed in insect extracts by the Bradford method at 595 nm27. The measurement is carried out by adding 200 µL of Bradford reagent to 40 µL of insect extract. The optical density was read in the spectrophotometer after 10 min against a control of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 0.1 M). The protein content was determined using Bovine Serum Albumin as a reference.

Phenoloxidase activity

Phenoloxidase (PO) activity was quantified applying the protocol denoted by Manjula et al.28. The absorbance was read at 490 nm using the multi-mode microplate reader (FLUOstar® Omega, BMG LABTECH, USA). The PO activity was calculated as follows (Eq. (7)):

With A = absorbance, volume of mixture = 200 µL, ε490nm (molar extinction of PO at 490 nm) = 3.715 (M− 1 cm− 1), sample volume = 50 µL, Optical length = 0.8 cm.

Catalase activity

Catalase activity was estimated as units/mg of protein. 40 µL of enzyme extract was added to 1.45 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS: 50 mM, pH 7.0), which contains 0.036% H2O228. The absorbance was read at 240 nm in the multi-mode microplate reader for 3 min. Catalase activity was calculated following the Eq. (7). With A = variation of absorbance per minute, volume of mixture = 1.49 mL, ε240nm (molar extinction of catalase activity at 240 nm) = 43.6 M− 1 cm− 1, sample volume = 40 µL, and optical length = 1 cm.

Glutathione S-transferase activity (GST)

GST activity was assessed using Habig et al.29 method with some modifications. Briefly, 30 µL of 1 mM glutathione, 10 µL of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) (1 mM in ethanol 95%), and 200 µL of PBS (pH 6.5, 0.1 M) were added to 10 µL of enzyme extract. The absorbance was read at 340 nm for 3 min using the multi-mode microplate reader. The GST activity was calculated following the Eq. (7), with A = variation of absorbance per minute, volume of mixture = 250 µL, ε340nm (molar extinction of GST at 340 nm) = 9.6 mM− 1 cm− 1, sample volume = 10 µL, and optical length = 1 cm. The result was expressed as units/mg of protein.

Amylase activity

Amylase activity was determined for insects in nutritional test following the method used by Sreekumar and Prabhu30. In pursuit of this, 100 µL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.2) and 200 µL of starch solution (1%) were added to 100 µL enzyme extract, then the mixture was incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 600 µL of 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent (96 mM DNS, 0.5 M NaOH, 5.3 M potassium sodium tartrate, and quantum satis of warm ultrapure water). After heating for 5 min at 100 °C, the absorbance was recorded at 550 nm and the amount (µg) of maltose equivalents liberated was calculated using maltose as a standard.

Statistical analysis

Probit analysis was used to determine mortality and effective dose estimates (PriProbit software). Significant variations in concentrations were detected in the present instance when the 95% confidence intervals (CI) did not overlap. The various insecticidal activity parameters and enzymatic activities are submitted to an analysis of variance with one or two classification criteria using SPSS software, followed by Tukey’s studentized test.

Results and discussion

Chemical characterization of SRE

The spectrophotometry analysis shows that there are about 83.5 g of saponins per 100 g of extract. This amount is higher than the results obtained by Bhargava et al.31 (20 g/100 g to 40 g/100 g of extract), Segura et al.8 (60% saponins found in quinoa husk extract), and Castillo-Ruiz et al.32 how found an amount of 36% w/w of total saponins after aqueous extraction and alkaline treatment, which confirms the richness of our extract in saponin. On the other hand, Muir et al.33 found an amount greater than our finding (85–90% w/w saponins) after alcohol extraction followed by acid hydrolysis of quinoa brain. The ethanol is considered the best solvent for the extraction of saponins because of their high solubilization properties34. Overall, the variation of the amount of saponins is due to several parameters, among them the extraction method, the used solvent, and the initial saponin content of the raw material35.

FTIR analysis

The infrared spectrum of the saponin extract (Table 1; Fig. 1a) disclosed the presence of broad and strong -OH signaling hydroxyl groups (3290 cm− 1) in the side chain of the saponin oligosaccharide. The band at 2945 cm− 1 attributable to C-H is a trait of alkane compounds36. Whereas, the bonds at 2883 cm− 1, 1718 cm− 1, and 1620 cm− 1 are attributable to the stretching of CH2, C=O, and C=C respectively37,38,39. Therefore, the absorption between 1150 cm− 1 and 1350 cm− 1 indicates the presence of C–O–C group. This spectrum was compared with the spectrum of Quillaija saponin standard (Fig. 1b). According to the obtained spectrum and spectrophotometry analysis (Sect. 3.1), the detected OH, C=O, C–H and C=C bands confirm the richness of the extract on saponin, which is in line with the claims of Mishra & Thakur40.

Effect of SRE on T. castaneum by contact action

Effective dose estimates of SRE

The saponin rich extract of quinoa showed a toxicity effect on T. castaneum adults. Table 2 presents the data of Effective Dose Estimates (ED) (in mg/mL) under their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% Limits) with the mortality percentages of 10% (ED10), 50% (ED50), 90% (ED90), and 99% (ED99). As shown, the concentration of 13.10 mg/mL SRE was necessary to attain the mortality of 10% of the population, and the median lethal concentration (ED50) was 43.26 mg/mL after one day of exposure. Furthermore, the mortality of 99% of the population was achieved with 378.52 mg/mL SRE. The noticeable effects displayed by quinoa bran extract can be related to its main triterpene components, which is supported by previous research studies that have shown that saponins possess insecticidal properties by topical application against different storage insects3,24,41.

Observation of the epidermis and surface structure of T. castaneum adults treated with SRE by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM was used to investigate the effects of SRE treatment on the epidermis and surface of the T. castaneum adults (Fig. 2). In comparison to the control treatment (distilled water) (Fig. 2, a1), the epidermis waxy layer of insects treated with SRE was ablated (Fig. 2, b1), resulting in the loss of certain pits and the formation of holes in the epidermis of the insects. Hence, SRE induces a dysfunction of the epidermis as the waxy layer protects the skin from drying out, senses the environment, and gives mechanical support and mobility to the insect42. The Fig. 2, b2, presents T. castaneum adult abdomen treated with aqueous solution containing SRE. The depicts showed a damage in the abdomen compared to the control (Fig. 2, a2). This alteration of the epidermis of insects was previously remarqued by researcher. Cui et al.13 proved that tea saponins can penetrate in E. obliqua via its cuticle because of their elevated viscosity and low interfacial tension, resulting in higher bioavailability of saponins than other natural compounds. Consequently, higher disruption of the insect waxy layer. Wakil et al. suggested that the main activity of diatomaceous earth on storage insects is abrasion of the insect cuticle and sorption of the wax layer43. May because of the polar characteristic of saponin molecules, the waxy covering of the insect body is damaged, allowing the active component to permeate the surface of the body and reach the target location, resulting in a significant contact toxicity44.

Effect of quinoa saponin rich extract on the diet and nutritional indexes of T. castaneum adults

Nutritional indices

The nutritional study was carried out to assess the relative palatability and growth response of T. castaneum to the flour disks amended with different concentrations of SRE (Table 3). The results showed a negative correlation between the growth rate (RGR) of insects and the concentration of the extract, with a significant decrease noted in the insects under the diet with SRE concentrations of 25 mg/g and beyond. A negative value of RGR was registered from the concentration of 50 mg/g to 100 mg/g and at the level of the starved group, which means that the insects have lost weight. It is noted that the insects under the 100 mg/g SRE diet lost more weight (-0.32 ± 0.05 mg/d), followed by the insects under the 75 mg/g and 50 mg/g SRE diets, and finally the starved group with a RGR equal to -0.19 ± 0.01 mg/d.

Likewise, the RCR of the studied insects decreased with increasing SRE concentrations, and from concentrations above 75 mg/g, the insects no longer consumed the disks. In previous studies, Lima et al.24 noted the growth-inhibiting and antinutritional activities of crud extracts containing saponins from G. americana against T. castaneum with loss of insects’ weight from the concentration of 100 mg of extract. However, at low extract concentrations, the insects fed but did not convert it to biomass, which confirms the positive correlation between the insect weight and the food consumption rate23,24.

Food deterrence index (FDI)

The Fig. 3a presents the results of the FDI in proportion to SRE doses. Overall, SRE extract demonstrated to be a feeding deterrent agent. The doses of 5 mg/g and 10 mg/g induced low food deterrence levels of about 44.32% and 44.64%, respectively. Under these doses, the insects were able to feed from amended disks. The value of FDI for the insects under the diet with 25 mg/g SRE was increased drastically up to 84.20%, and the insects in the box of the treated disks with 50 mg/g, 75 mg/g, and 100 mg/g were increased up to 92.69%, 93.60%, and 96.82%, respectively, with a non-significant difference. These findings are in accordance with the results obtained at the level of food consumption rate. In the same context, previous research studies have found that pest insects fed an artificial diet containing saponins consume less food due to digestive disruption3,24. The inclusion of total saponins from alfalfa in the diet of Colorado potato beetle larvae lowered their dietary intake, growth rate, and survival45. Nielsen et al. investigated the function of saponins in Barbarea vulgaris resistance to the flea beetle (Phyllotreta nemorumi L.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). They examined the feeding-deterrent action of isolated saponins from B. vulgaris and found that hederagenin cellobioside has a significant feeding deterrent and defensive chemical against the flea beetles46.

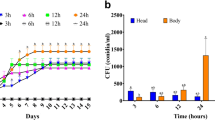

Effect of SRE on insect survival

The number of surviving insects was recorded over 60 days to assess the long-term effect of saponins. Figure 3b shows a positive correlation between the insect mortality rate and the dose of saponin extract. A mortality rate of 20% of the population was observed at the concentration of 100 mg/g after 10 days, whereas this mortality rate was achieved for 25 and 50 mg/g after 30 and 20 days, respectively. For 75 mg/g and starved insects neededn17 days to attain this 20% mortality. On the other hand, the population under a 0, 5, and 10 mg/g saponin diet was found to need 60 days to lose about 20% of insects. However, the population under the diet treated with 100 mg/g of saponins was the first to achieve 100% mortality after 60 days of incubation, earlier than the starved one. This result shows that the mortality of T. castaneum is attributable to the toxicity of the product and not just the starvation action. These findings are consistent with the result of Lima et al.24 previously found that the mortality of T. castaneum was up to 73% at 250 mg of extract rich in saponins from Genipa americana per g of wheat flour after 28 days of consuming the diet. In comparison with 100 mg/g in our case, a mortality rate of 73% was reached also after around 28 days. Shahriari et al.47 also reported the mortality effect of tea saponins on the larvae of Ephestia kuehniella Zeller. Moreover, Szczepanik et al.45 investigated the effect of saponins from several Medicago species on the larvae of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Their results showed that the extracted saponins reduced the growth rate of the insect and affected the survival of the larvae. On the other hand, McCartney et al. showed that quinoa bran extract was insecticidal only against non-quinoa feeders (Pseudaletia impuncta) and had no observable negative effects on survival or developmental time for quinoa feeders (Feltia subterranea and Trichoplusia ni), suggesting that the abundances and/or types of saponins produced by explored quinoa genotypes are insufficient to protect these adapted species48.

Effect of SRE on enzymatic activities of T. Castaneum

Phenoloxidase activity

Phenoloxidase (PO) in insects has a key role in the immune defense system, and some studies have shown its role in sclerotization and brown pigmentation of the T. castaneum cuticle49,50. The effect of SRE on PO activity of T. castaneum was determined using L-DOPA as a substrate. For the antifeeding test, results showed a significant decrease in PO activity by introducing SRE into the diet of insects. A low value of PO activity was noted in the insects under a diet of 50 mg/g of SRE (0.015 U/mg protein) (Fig. 4a). This aligns with Mirhaghparast et al. findings, where saponin was found to suppress the immune system by decreasing the PO activity51. The same significant reduction in PO activity was revealed in starved insects. The research of Ebrahimi and Ajamhassani52 reported that the PO activity was considerably lowered in the larvae of Plodia interpunctella (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) because of starvation. Therefore, the low concentrations of SRE have reduced the level of phenoloxidase activity by acting as an inhibitor, while the decrease of PO activity from the concentration 75 mg/g can be explained by the starvation effect based on the results of nutritional indices. The study of Zibaee & Bandani showed that the plant extract can interfere with the PO activity of Eurygaster integriceps (Heteroptera: Scutellaridae), and a significant decrease in PO activity was noted with the increase of extract concentrations53. For the topical test, Fig. 4b shows a slight increase of PO activity in insects treated with 5 and 25 mg/mL. In contrast, a non-significant difference was observed between the control and the extract at 50, 75, and 100 mg/mL. This results can be explained by the capacity of saponins, at low concentrations, to induce the activation of PO, reflecting as a defense strategy of the insect against saponin extract as a stressful agent54. On the other hand, at concentrations above 50 mg/mL, the saponins act as inhibitors of the phenoloxidase due to their antioxidant capacity50, which confirm that the defense system of T. castaneum from all kinds of inhibitors and activators largely reliant on PO activity55,56. Otherwise, the variation of the effect of SRE concentrations between the nutritional and topical tests demonstrated the advantageous impact of the diet on the insect immune defense system52; At the level of nutritional test the low concentrations can inhibited the PO activity compared with the topical test the inhibition start at concentrations above 50 mg/mL.

Phenoloxidase (PO) activity in the adult of T. castaneum exposed to SRE by a flour disk diet amended with different concentrations of SRE for antifeeding test (a) and treatment with SRE aqueous solution for the topic test (b). The enzyme values are expressed in U/ mg protein as mean (± SD) values and analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments by Tukey’s test. S: Starved group.

Catalase activity

The effect of SRE on the catalase activity of T. castaneum is shown in Fig. 5. Overall, there was a significant increase of catalase activity in insects under SRE diet (Fig. 5a) and in insects exposed to SRE at the level of topical assay (Fig. 5b) when compared to the control (P ≤ 0.001). Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between the catalase activity and the SRE doses in the nutritional study. A similar activity increase in antioxidant enzymes, including the catalase activity of E. kuehniella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), under diets containing different concentrations of saponins isolated from tea, was reported by Shahriari et al.47. Also, Manjula et al.28 reported a significant rise in catalase activity in Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) after its exposure to the leaf extract of M. esculenta. For the starvation effect, starved insects demonstrated higher catalase activity. Likewise, Peter et al.57 registered a significant increase in catalase activity in the starved group of juvenile loaches (Paramisgurnus dabryanus) (Cypriniformes: Cobitidae) comparing with the feed group. Following starvation stress, insects produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS), which activate their antioxidant system. Antioxidant enzymes contribute to eliminating the harmful free radicals generated because of the toxicant exposure28,58. Herein, the catalase primarily involves the decomposition of H2O2, resulting in the synthesis of water and molecular oxygen. The increase in catalase activity protects insects from oxidative damage and stress58. Conversely, the decrease in catalase activity can lead to high levels of superoxide anion radicals, which can inhibit or slow down the catalase enzyme function26.

Catalase activity in the adult of T. castaneum exposed to SRE by a flour disk diet amended with different concentration of SRE for antifeeding test (a), and treatment with SRE aqueous solution for the topic test (b). The enzyme values are expressed in µmol H2O2 / mg protein as mean (± SD) values and analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.001) among treatments by Tukey’s test. S: Starved group.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity

Detoxification enzyme bioactivity, including GST activity, has a crucial role in an insect’s ability to survive and grow under stressful environments, including pharmacologically active compounds59. Figure 6 illustrates the SRE effects on GST activity of T. castaneum adults. For the nutritional study (Fig. 6a), the highest GST activity in insects was observed under diet with 5 mg/g of SRE, while lowest GST activity was registered at 100 mg/g of SRE. However, results disclosed a non-significant difference in the GST activity of insects under the diet with other concentrations, i.e., 10 to 75 mg/g of SRE when compared to the control (P ≤ 0.05). For the topic test (Fig. 6b), an upregulation of GST activity was noted with the rise of SRE concentrations from a mean of 0.82 mU/mg protein in the control to 2.10 mU/mg protein in 100 mg/mL.

GST activity in the adult of T. castaneum under a flour disk diet amended with different concentrations of SRE for antifeeding test (a), and exposure to SRE aqueous solution for the topic test (b). The enzyme values are expressed in mU/mg protein as mean (± SD) values and analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments by Tukey’s test. S: Starved group.

These findings are consistent with Shahriari et al.39, where tea saponins were found to induce a high GST activity in E. kuehniella. Likewise, Dhivya et al.58 reported that the levels of GST enzymes in S. litura raised after 2 h of exposure to the hexane extract of Prosopis juliflora. Also, Li et al.60 observed a similar pattern in T. castaneum treated with various doses of paeonol extract from Moutan cortex. In the same vein, Manjula et al.28 revealed a significant increase in GST activity in S. litura (P ≤ 0.001) after 4 h of exposure to leaf extract of M. esculenta. It was also disclosed that GST activity decreased gradually after 12 and 24 h of leaf extract exposure, compared to the control (P < 0.05). This drop might be attributed to elevated ROS levels, which have a dramatic effect on cells and can induce cellular damage, inhibiting GST enzymes. In line with above, Czerniewicz et al.61 demonstrated that GST enzyme bioactivity was significantly boosted after a low dose exposure of aphids into clove oil, while this bioactivity was reduced at higher doses. In this study, GST activity was significantly simulated by low concentrations of SRE i.e., 5 mg/g. However, at concentrations exceeding 75 mg/g of SRE, GST activity decreased in insects, indicating that GST activity is an SRE concentration dependent parameter as it is influenced by the concentration of the toxic compound applied. This pattern is positively correlated with observed oxidative damage of insect tissues at higher concentrations. Noteworthy to mention that GSTs play critical roles in the evolution of insecticide resistance and antioxidant defense62. Hence, the increase of GST activity is positively correlated with insect resistance to insecticides, which means that the reduction of this enzyme activity will hinder insect resistance evolution60,63,64.

Amylase activity

The α-amylase variation in T. castaneum exposed to a disk diet amended with different concentrations of SRE is illustrated in Fig. 7. the results showed a significant reduction in α-amylase activity as contrast to the control. This saponin effects on α-amylase as a digestive enzyme have been documented in several studies. Maazoun et al.65 demonstrated that saponins isolated from A. americana leaf extract may have role in the inhibition of Sitophilus oryzae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) digestive enzymes. Shahriari et al.47 reported the suppression of digestive enzymes of E. kuehniella under a saponin tea diet. Furthermore, Li et al.66 noted a significant inhibition of pea aphids (A. pisum) α-amylase after treatment with isolated triterpenoid saponins from Clematis lasiandra. While, Ye et al.67 reported a suppression of α-amylase in aphids after treatment with triterpenoid saponins from Oxytropis hirta Bunge. Other triterpenoids also showed the inhibition effect of α-amylase, e.g., ecdysteroids Makisterone A and 22-hydroxyhopane in T. castaneum68,69 and 22-hydroxyhopane from Adiantum latifolium in Oryctes rhinoceros Linn70.

Amylase activity in the T. castaneum adult under a flour disk diet amended with different concentrations of SRE for the antifeeding test. The enzyme values are expressed in mU/mg protein as mean (± SD) values and analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments by Tukey’s test. S: Starved group.

Saponins’ toxicity might be attributed to their capacity to promote membrane fluidity65. Saponins can diminish cell viability by enhancing membrane permeability, causing organelle injury in midgut tissues. Consequently, this can cause digestive problems, nutritional deficiencies, and even death65,67. Moreover, the inhibition of the activity of digestive enzymes such as amylase, carbohydrases, proteases, exopeptidases, and TAG-lipase by saponins can be a sign of organelle damage in the midgut tissues51,66,67. These findings sparked interest in studying the midgut as a target to illuminate the mechanism of action for the most active saponin against insects66. Saponins are thought to facilitate food transit in the insect stomach while affecting digestion by interfering with the secretion of digestive enzymes10. Rane et al.71 identified three α-amylase inhibitors (αAIS) specific against coleopteran storage pests i.e., Amaranthus hypochondriacus (AhAI), Alternanthera sessilis (AsAI), and Chenopodium quinoa (CqAI). The highest inhibition potency on T. castaneum α-amylase was observed for AhAI, followed by AsAI and CqAI. The selectivity of these inhibitors against coleopteran α-amylases highlights their potential for controlling storage grain pests. α-amylase is an essential digestive enzyme required for the growth and development of insects, which can catalyze the hydrolysis of carbohydrates, and αAIS target α-amylases and interfere with carbohydrate digestion in insects, resulting in their starvation and death4.

In this study, a significant reduction was observed in α-amylase activity due to the starvation effect. This reduction aligns with the nutritional indices results, indicating that at concentrations of 50 mg/g and above, the insects ceased consuming the disks, which may explain the high mortality rate of insects subjected to diet with higher concentrations of SRE (50, 75, and 100 mg/g flour). Similarly, previous studies have focused on deciphering the underlying causes of insects’ deaths. The results revealed the presence of a strong relationship between starvation and digestive enzyme activities. Abad et al. observed a reduction of α-amylase activity in the Colorado potato beetle (L. decemlineata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), which was due to starvation72. In the same line, Peter et al. found that in starved group of juvenile loaches (P. dabryanus), the digestive enzyme activities were lower compared to those in the feed group57.

Conclusion

The antinutritional and insecticidal potential of quinoa SRE against T. castaneum was investigated in this work. It was found that SRE is an efficient insecticidal agent as it significantly affects the survival time and promotes nutritional disorders in T. castaneum adults. SRE induced acute contact toxicity in T. castaneum by ablating the waxy layer of the epidermis and penetrating the cuticle of the insect. In addition, SRE exhibited antifeeding effects on T. castaneum under its diet by altering the nutritional indices, resulting reduction of dietary intake in insects fed with an artificial diet containing saponins. This affectation is attributed to the toxic action of the saponins rather than just the starvation action. Saponins affect enzymatic systems through two mechanisms, i.e., starvation and toxicity. Starvation, generally induced by high doses of saponins (> 25 mg/g), affects the immune defense system through the downregulation of phenoloxidase activity, the upregulation of the antioxidant system presented in this study with catalase activity, and the inhibition of amylase activity. On the other hand, the toxicity of quinoa saponins was demonstrated by the upregulation of phenoloxidase, catalase, and glutathione S-transferase activities, which confirmed the capacity of saponins to induce damage to insect cuticles by penetrating insects and reacting as oxidative stressors. Hence, saponins’ diverse mechanisms of action and detrimental effects on insects underscore their potential as promising compounds for pest control, especially for storage insects.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author (Manal.MHADA@um6p.ma).

References

Yu, S. J. The Toxicology and Biochemistry of Insecticides. CRC Press. 2, 380 (2014).

Niedermayer, S., Pollmann, M. & Steidle, J. L. M. Lariophagus distinguendus (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) (Förster)—past, presentfuturefutheehistoryistory of a biological control musing using L. distinguendus agdifferentfstoragetpests pests. Insects 7, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects7030039 (2016).

Singh, B. & Kaur, A. Control of insect pests in crop plants and stored food grains using plant saponins: A review. LWT 87, 93–101 (2018).

Huang, S. et al. The latest research progress on the prevention of storage pests by natural products: Species, mechanisms, and sources of inspiration. Arab. J. Chem. 15(11), 104189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104189 (2022).

Pang, R. et al. Insecticide resistance reduces the profitability of insect-resistant rice cultivars. J. Adv. Res. 60, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.07.009 (2024).

Lengai, G. M. W., Muthomi, J. W. & Mbega, E. R. Phytochemical activity and role of botanical pesticides in pest management for sustainable agricultural crop production. Sci. Afr. 7, e00239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00239 (2020).

Seiber, J. N., Coats, J., Duke, S. O. & Gross, A. D. Pest management with biopesticides. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 5, 295–300 (2018).

Segura, R. et al. Phytostimulant properties of highly stable silver nanoparticles obtained with saponin extract from Chenopodium quinoa J. Sci. Food Agric. 100, 4987–4994. https://doi.org/Herrera (2020).

Sparg, S. G., Light, M. & van Staden, J. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 94, 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2004.05.016 (2004).

Mirhaghparast, S. K., Zibaee, A., Hajizadeh, J. & Ramzi, S. Toxicity and physiological effects of the tea seed saponin on Helicoverpa armigera Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 25, 101597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101597 (2020).

Pour, S. A. et al. Toxicity, antifeedant and physiological effects of trans-anethole against Hyphantria cunea Drury (Lep: Arctiidae). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 185, 105135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2022.105135 (2022).

Golawska, S., Bogumil, L. & Oleszek, W. Effect of low and high-saponin lines of alfalfa on pea aphid. J. Insect Physiol. 52 (7), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.04.001 (2006).

Cui, C. et al. Insecticidal activity and Insecticidal mechanism of total saponins from Camellia Oleifera. Molecules 24, 4518. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24244518 (2019).

Zeng, C., Wu, L., Zhao, Y., Yun, Y. & Peng, Y. Tea saponin reduces the damage of Ectropis Obliqua to tea crops and exerts reduced effects on the spiders Ebrechtella tricuspidata and Evarcha albaria compared to chemical insecticides. PeerJ 6, e4534. https://doi.org/10.7717peerj.4534 (2018).

Cai, H. et al. Effects of tea saponin on growth and development, nutritional indicators, and hormone titers in diamondback moths feeding on different host plant species. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 131, 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.12.010 (2016).

Lin et al. Quinoa secondary metabolites and their biological activities or functions. Molecules 24, 2512. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132512 (2019).

El Hazzam, K. et al. Box-Behnken design: wet process optimization for saponins elimination from Chenopodium quinoa seeds and the study of its effect on nutritional properties. Front. Nutr. 9, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.906592 (2022).

Mora, M., Morillo-Coronado, A. & Manjarres Hernández, E. Extraction and Quantification of Saponins in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Genotypes from Colombia. Int. J. Food Sci. 1–7. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7287487 (2022).

Irigoyen, R. M. T. & Giner, S. A. Extraction kinetics of saponins from Quinoa seed (Chenopodium quinoa Willd). Int. J. Food Stud. 7, 76–88 (2018).

Mhada, M., Metougui, M. L., Hazzam, E., El Kacimi, K. & Yasri, A. K. Variations of saponins, minerals and total phenolic compounds due to processing and cooking of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Seeds. Foods 9, 660. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9050660

Baccari, W. et al. Composition and insecticide potential against Tribolium castaneum of the fractionated essential oil from the flowers of the Tunisian endemic plant Ferula Tunetana Pomel ex Batt. Ind. Crops Prod. 143, 111888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111888 (2020).

Püntener, W. Manual for field trials in plant protection. Agric. Div. Ciba-Geigy Limited, Basle, Switzerland. 205 (1981).

Napoleão, T. H. et al. Deleterious effects of myracrodruon urundeuva leaf extract and lectin on the maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera, Curculionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 54, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2013.04.002 (2013).

Lima, J. K. A. et al. Biotoxicity of aqueous extract of Genipa americana L. bark on red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). Ind. Crops Prod. 156, 112874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112874 (2020).

Shekari, M., Sendi, J. J., Etebari, K., Zibaee, A. & Shadparvar, A. Effects of Artemisia annua L. (Asteracea) on nutritional physiology and enzyme activities of elm leaf beetle, Xanthogaleruca luteola Mull. (Coleoptera: Chrysomellidae). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 91(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2008.01.003 (2008).

Rajkumar, V. et al. Toxicity, antifeedant and biochemical efficacy of Mentha Piperita L. essential oil and their major constituents against stored grain pest. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 156, 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.02.016 (2019).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Manjula, P. et al. Effect of Manihot esculenta (Crantz) leaf extracts on antioxidant and immune system of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 23, 101476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101476 (2020).

Habig, W. H., Pabst, M. J., Jakoby, W. B. & Glutathione S-Transferases: the first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 7130–7139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42083-8 (1974).

Sreekumar, S. & Prabhu, V. K. K. Digestive enzyme secretion during metamorphosis in Oryctes rhinoceros (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Proc. Anim. Sci. 97, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03179512 (1988).

Bhargava, A., Shukla, S. & Ohri, D. Chenopodium quinoa—an Indian perspective. Ind. Crops Prod. 23, 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2005.04.002 (2006).

Castillo-Ruiz, M. et al. Safety and efficacy of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) saponins derived molluscicide to control of Pomacea maculata in rice fields in the Ebro Delta, Spain. Crop Prot. 111, 42–49 (2018).

Muir, A. D., Paton, D., Ballantyne, K. & Aubin, A. A. Process for recovery and purification of saponins and sapogenins from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Agriculture and Agri Food Canada AAFC. Patent: US6355249B2. (2002). https://patents.google.com/patent/US6355249B2/en

Cheok, C. Y., Salman, H. & Sulaiman, R. Extraction and quantification of saponins: A review. Food Res. Int. 59, 16–40 (2014).

Bhargava, A., Srivastava, S. & Quinoa Botany, Production and Uses (CABI, 2013).

Machale, J., Majumder, S. K., Ghosh, P. & Sen, T. K. Development of a novel biosurfactant for enhanced oil recovery and its influence on the rheological properties of polymer. Fuel 257, 116067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116067 (2019).

Mehrabianfar, P., Bahraminejad, H. & Manshad, A. K. An introductory investigation of a polymeric surfactant from a new natural source in chemical enhanced oil recovery(CEOR). J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 198, 108172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.108172 (2021).

Nowrouzi, I., Mohammadi, A. H. & Manshad, A. K. Water-oil interfacial tension (IFT) reduction and wettability alteration in surfactant flooding process using extracted saponin from Anabasis Setifera plant. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 189, 106901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106901 (2020).

Yekeen, N., Malik, A. A., Idris, A. K., Reepei, N. I. & Ganie, K. Foaming properties, wettability alteration and interfacial tension reduction by saponin extracted from soapnut (Sapindus Mukorossi) at room and reservoir conditions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 195, 107591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107591 (2020).

Mishra, S. & Thakur, M. Role of microwave assisted extraction for isolation of saponins from Sapindus Mukorrosai and synthesis of its stable biofunctionalized silver nanoparticles and its hypolipidaemic activity. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 7, 2959–2965 (2016).

Geyter, E. et al. Novel advances with plant saponins as natural insecticides to control pest insects. Pest Technol. 1, 96–105 (2007).

Balabanidou, V., Grigoraki, L. & Vontas, J. Insect cuticle: A critical determinant of insecticide resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 27, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2018.03.001 (2018).

Wakil, W. et al. Entomopathogenic fungus and enhanced Diatomaceous Earth: The sustainable Lethal combination against Tribolium castaneum. Sustainability 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054403 (2023).

Dayan, F. E., Cantrell, C. L. & Duke, S. O. Natural products in crop protection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 4022–4034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.046 (2009).

Szczepanik, M., Krystkowiak, K., Jurzysta, M. & Biały, Z. Biological activity of saponins from alfalfa tops and roots against Colorado potato beetle larvae. Acta Agrobot 54, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.5586/aa.2001.02 (2001).

Nielsen, J. K., Nagao, T., Okabe, H. & Shinoda, T. Resistance in the plant, Barbarea vulgaris, and counter-adaptations in Flea Beetles mediated by Saponins. J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-010-9758-6 (2010).

Shahriari, M. et al. Mortality and physiological impacts of the tea saponin against Ephestia Kuehniella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Toxin Rev. 41, 1077–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/15569543.2021.1974042 (2021).

McCartney, N. et al. Effects of saponin-rich quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Bran and bran extract in diets of adapted and non-adapted quinoa pests in laboratory bioassays. Cienc. E Investig Agrar. 46, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.7764/rcia.v45i2.2159 (2019).

Gorman, M. J. & Arakane, Y. Tyrosine hydroxylase is required for cuticle sclerotization and pigmentation in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.01.004 (2010).

Zhang, H. & Zhou, Q. Tyrosinase Inhibitory effects and Antioxidative activities of Saponins from Xanthoceras Sorbifolia Nutshell. PloS One. 8, e70090. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070090 (2013).

Mirhaghparast, S. K., Zibaee, A., Hajizadeh, J. & Ramzi, S. Changes in immune responses, gene expression, and life table parameters of Helicoverpa Armigera Hübner fed on a diet containing the saponin of tea plant, Camellia sinensis. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 111, e21962. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.21962 (2022).

Ebrahimi, M. & Ajamhassani, M. Investigating the effect of starvation and various nutritional types on the hemocytic profile and phenoloxidase activity in the Indian meal moth Plodia interpunctella (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). ISJ-Invertebr Surviv J. 17, 175–185 (2020).

Zibaee, A. & Bandani, A. R. Effects of Artemisia annua L. (Asteracea) on the digestive enzymatic profiles and the cellular immune reactions of the Sunn pest, Eurygaster integriceps (Heteroptera: Scutellaridae), against Beauveria bassiana. Bull. Entomol. Res. 100, 185–196 (2009).

Duffield, K. R., Rosales, A. M., Muturi, E. J., Behle, R. W. & Ramirez, J. L. Increased phenoloxidase activity constitutes the main defense strategy of Trichoplusia ni Larvae against Fungal Entomopathogenic infections. Insects 14(8), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14080667 (2023).

Taleh, M., Saadati, M., Farshbaf, R. & Khakvar, R. Partial characterization of phenoloxidase enzyme in the hemocytes of Helicoverpa Armigera Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 26, 285–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2013.08.005 (2014).

Fan, T., Jing, Z., Fan, X., Yu, M. & Jiang, G. Purification and characterization of phenoloxidase from brine shrimp Artemia sinica. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 43 (9), 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1093/abbs/gmr061 (2011).

Peter, M. et al. Effects of starvation on enzyme activities and intestinal microflora composition in loach (Paramisgurnus dabryanus). Aquac Rep. 18, 100467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100467 (2020).

Dhivya, K. et al. Bioprospecting of Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC seed pod extract effect on antioxidant and immune system of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Physiol. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 101, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2017.09.003 (2018).

Song, X. W. et al. Characterization of a sigma class GST (GSTS6) required for cellular detoxification and embryogenesis in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Sci. 29, 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12930 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Biological activities and gene expression of detoxifying enzymes in Tribolium castaneum induced by Moutan cortex essential oil. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 85, 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2022.2066038 (2022).

Czerniewicz, P., Chrzanowski, G., Sprawka, I. & Sytykiewicz, H. Aphicidal activity of selected Asteraceae essential oils and their effect on enzyme activities of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 145, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.01.010 (2018).

Oyedeji, A. O., Okunowo, W. O., Osuntoki, A. A., Olabode, T. B. & Ayo-folorunso, F. Insecticidal and biochemical activity of essential oil from Citrus sinensis peel and constituents on Callosobrunchus Maculatus and Sitophilus zeamais. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 168, 104643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104643 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Inhibition of insect glutathione s-transferase (GST) by conifer extracts. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 87, 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.21192 (2014).

Meng, X. et al. Identification and characterization of glutathione S-transferases and their potential roles in detoxification of abamectin in the rice stem borer, Chilo Suppressalis. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 182, 105050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2022.105050 (2022).

Maazoun, A. M. et al. Phytochemical profile and insecticidal activity of Agave americana leaf extract towards Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26, 19468–19480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05316-6 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. New triterpenoid saponins from Clematis Lasiandra and their mode of action against pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum. Ind. Crops Prod. 187, 115517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115517 (2022).

Ye, S. et al. Identification of azukisapogenol triterpenoid saponins from Oxytropis Hirta Bunge and their aphicidal activities against pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris. Pest Manag Sci. 79, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.7172 (2023).

Ajaha, A., Annaz, H., Bouayad, N., Aarab, A. & Rharrabe, K. Ingestion effect of Makisterone A, a phytoecdysteroid, on development and detoxification enzymes of Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Afr. Entomol. 29, 332–340. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.029.0332 (2021).

Ajaha, A., Bouayad, N., Aarab, A. & Rharrabe, K. Effect of 20-hydroxyecdysone, a phytoecdysteroid, on development, digestive, and detoxification enzyme activities of Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Insect Sci. 19 (5), 18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iez097 (2019).

Kumar, R. P., Babu, K. V. D. & Evans, D. A. Isolation, characterization and mode of action of a larvicidal compound, 22-hydroxyhopane from Adiantum latifolium Lam. Against Oryctes rhinoceros Linn. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 153, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.11.018 (2019).

Rane, A. S., Venkatesh, V., Joshi, R. S. & Giri, A. P. Molecular investigation of Coleopteran specific α-Amylase inhibitors from Amaranthaceae members. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 163, 1444–1450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.219 (2020).

Abad, R. F., Safaei khorram, M., Valizadeh, M. & Yazdanian, M. Effect of starvation and age of insects on alpha amylase activity of Colorado Potato Beetle. in (2007).

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the Movement initiative by OCP Group, Morocco for its financial support. Also, we are grateful to the Materials Science, Energy, and Nano-engineering (MSN) department at UM6P and to Act4Community Volunteers and management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KEH: Collected the data, Performed the analysis, Wrote the paper MM: Supervision and validation WB: Contributed to analysis tools MT: Validation AY: Conceived the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hazzam, K.E., Mhada, M., Bakrim, W.B. et al. Antinutritional and insecticidal potential of Chenopodium quinoa saponin rich extract against Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) and its action mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 6829 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90952-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90952-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phytochemical composition and biopesticidal potential of Gypsophila pilosa Huds

BMC Plant Biology (2026)

-

Optimisation and economic assessment of a lowcost insecticide for stored product insect pest control and seed viability

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Highlighting the impact of soyasaponin on the snail Theba pisana: Emphasis on the contact toxicity and biochemical perturbations

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2026)

-

Multifaceted bioactivity of Moringa Oleifera leaf extracts on survival, reproduction, and digestive physiology of Sitophilus oryzae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection (2026)