Abstract

Understanding the intergenerational transmission of childhood maltreatment (CM) is crucial to prevent its perpetuation to future generations. The literature has revealed parental empathy to be a pivotal factor in this process. Parental empathy is the ability to comprehend and empathetically respond to the emotions and mental states of children; therefore, its impairment may result in challenges in parenting, ultimately contributing to CM. In this study, we explored the factors that undermine empathy and how they alter parenting practices, to uncover the process of intergenerational transmission of CM. To investigate actual instances of CM, a comparative study was conducted between 13 mothers with a history of social interventions owing to CM and 42 mothers in the control group. Path analysis was performed to examine the trajectory from adverse childhood experiences to maltreatment and explore their correlations with variables including affective and cognitive empathy, depressive symptoms, and parenting styles. The results showed that experiences of CM specifically enhanced empathy in the emotional domain in the maltreatment group. Furthermore, heightened empathy in the maltreatment group influenced parenting style mediated by depressive symptoms. These results provide important insights into the intergenerational transmission process in the context of parental empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to quantitative research on childhood maltreatment (CM), factors contributing to it include demographic attributes such as age, education level, and economic status, as well as challenges in parenting, parental health conditions, and parents’ own experiences of being maltreated1. It is especially noteworthy that a parent’s history of maltreatment is linked to the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment. This cycle suggests that individuals who experience maltreatment as children may, when they become parents, continue this pattern by mistreating their own children2. Numerous studies have explored the underlying mechanisms, including the factors that mediate its continuation. Of particular significance is the parental capacity for empathy, which involves understanding and reflecting on children’s emotions and mental states3. If this significant parenting ability is impeded, parents may find it challenging to rear their children, ultimately leading to abusive behavior toward their children. Given this, Berzenski and Yates elucidated that experiencing childhood psychological abuse and neglect would predict a decrease in empathy by the age of 8 years, suggesting the possibility of intergenerational transmission of CM from the perspective of empathy4. However, the process of the decline in empathy for actual abusive behavior remains unclear. Hence, it is crucial to examine the process leading from the presence or absence of adverse maternal experiences to the level of empathy, focusing on how this relates to abusive maternal behaviors.

Empathy is a multidimensional construct that includes affective and cognitive states. The affective state of empathy is generally defined as an emotional response to an affective state elicited by observing or imagining another person’s emotional state. Cognitive empathy refers to the ability to understand and consider others’ perspectives5. The development of empathy interacts with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental factors6. When these factors are maladapted, internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression might develop later in life of people7. It is evident that such internal problems impede prosocial behavior8, restrain aggression9 and utilize social skills10 by making it challenging to comprehend others’ emotions. Despite extensive research into these associations, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how various factors contribute to empathy, and how they specifically relate to CM.

Previous studies indicated potential risk factors that impaired empathy such as psychiatric disorder11,12 and PTSD13. However, when considering the intergenerational cycle of CM through the lens of empathy, it is essential to examine parents’ adverse experiences and their impacts on empathy. Prevailing findings from numerous studies have demonstrated that parents’ adverse experiences have a negative impact on the emotional and/or cognitive aspects of empathy. One study suggested the presence of a mediating factor between adverse childhood experiences and individuals’ empathetic state14. However, most studies have focused on the correlation between the risk of parental maltreatment and empathy levels15,16. Despite the abundance of related research, few studies compare mothers who have with have not engaged in CM.

It has been demonstrated that parents’ own experiences of CM affect their later empathy. Moreover, research has shown that parents who showed significantly high in affective empathy, specifically personal distress (PD), have experienced parenting which was over protective/reactive or extremely permissive while in childhood17,18. These results demonstrate that altered empathy could pose challenges in real parenting situations and highlight important insights into the intergenerational perpetuation of maltreatment. However, it is unclear whether parental empathy among those who practice extreme parenting is a result of their own CM experiences. To gain a deeper understanding of the intergenerational transmission of CM, exploring this issue further is crucial.

In addition to emotional and cognitive factors, recent research has examined the physiological underpinnings of parental stress. Specifically, studies have explored how cortisol, a key stress hormone, relates to parental stress levels and its broader effects, providing further context for understanding the ways in which early adverse experiences might influence both empathy and parenting behaviors. Previous studies have examined the relationship between cortisol levels and empathy as impacted by stress stemming from CM experiences. While there was report of inconsistent research findings regarding the relationship between PTSD resulting from childhood abusive experiences, cortisol levels, and empathy19, another indicated that childhood abusive experiences may influence cortisol levels with empathy serving as a mediating factor20. Moreover, intriguing findings from recent research demonstrated that the parenting style had an impact on the cortisol levels of children21 and their executive function22. Therefore, parents’ stress levels, shown as cortisol levels, not only influence child-rearing but also the development of their own children, which suggests an increased risk of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

The current study investigated the impact of empathy on the continuum from parents’ own experiences of maltreatment to their subsequent parenting behaviors, aiming to better understand the mechanisms of CM from the perspective of intergenerational transmission of parenting practices. For this purpose, we conducted comparative studies of mothers who engaged in maltreatment and those who did not. We also measured the salivary cortisol levels of mothers in the two groups to identify the relationship between empathy and cortisol levels that affected their actual parenting, expecting to obtain physiologically informed insights on this matter.

Results

Demographic information

A total of 55 mothers aged between 25 and 50 years participated in this study. Of these, 13 were identified as mothers who engaged in maltreatment; they were referred to our laboratory by pediatricians and child psychiatrists. The remaining 42 mothers, age-matched with the maltreatment group, constituted the control group. Demographic information of the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups is presented in Table 1. Chi-square tests were conducted for the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups, with the following results: psychiatric disorders; χ2(1) = 25.38, p < 0.001, neurological diseases; χ2(1) = 10.25, p = 0.01, and neurodevelopmental disorders; χ2(1) = 10.25, p < 0.01. Significant differences were observed between the two groups for all these variables. The mothers of maltreatment group are more likely to be single parent than those of non-maltreatment group; χ2(1) = 11.60, p < 0.001. Conversely, the maltreatment group scored significantly lower on educational level; χ2(1) = 17.83, p < 0.001, and income; χ2(1) = 5.96, p < 0.05 than the ones of non-maltreatment group. No significant difference was found between the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups in terms of age or number of children.

Table 2 indicates psychological measurements and cortisol levels separately for maltreatment group and non-maltreatment group. Mothers’ adverse experiences were assessed using the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ); empathy was measured with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), depressive symptoms with the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and parenting style with the Parenting Scale (PS). A two-sample t-test was performed to examine the differences between the two groups. There was a significant difference in ACE between the maltreatment group and the non-maltreatment group; t(47) = -6.65, p < 0.001, for physical abuse of CTQ; t(46) = -4.94, p < 0.001, for emotional abuse of CTQ; t(46) = -6.14, p < 0.001, for sexual abuse of CTQ; t(46) = -2.90, p < 0.01, for physical neglect; t(46) = 5.00, p < 0.001, for emotional neglect; t(46) = -5.23, p < 0.001, for total of CTQ; t(53) = -6.62, p < 0.001, for SDS; t(53) = -5.30, p < 0.001, for PD of IRI; t(53) = -2.50, p < 0.05, for Fantasy scale of IRI; and t(53) = -2.19, p < 0.05.

No significant differences were found in the other subscales of the IRI and Parenting scales. As for cortisol levels, although statistical significance was not presented, marginal difference was found between the maltreatment group and non-maltreatment group; t(49) = -1.83, p = 0.07.

Path analysis

Mixed group (maltreatment and non-maltreatment mothers)

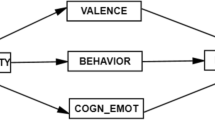

To investigated the trends among all mothers, we conducted a path analysis for the mixed group. We aimed to not only determine whether they engaged in child maltreatment in a simplistic “either/or” manner, but also to understand the act of maltreatment from a more nuanced, spectrum-based perspective. In this model, empathy was divided into affective and cognitive aspects. Affective empathy includes Empathic Concern (EC) and PD, while cognitive empathy includes Perspective Taking (PT) and the Fantasy scale (FS)13. Furthermore, for a deeper understanding of mothers’ experiences of CM, path analysis was conducted using both the ACE, which measures the relative severity of CM, and the CTQ, which provides a more detailed assessment of CM through its subscales. Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical path model. Based on previous research and correlations of key variables shown in Table 3, we hypothesized that adverse childhood experiences affect mothers’ empathy, leading to dysfunctional parenting mediated by depressive symptoms. The paths between the total scores on adverse childhood experiences (ACE or CTQ), cognitive empathy (PT and FS scores of IRI), affective empathy (EC and PD scores of IRI), depressive symptoms (total SDS score), and parenting style (total PS score) were tested using path analysis model to evaluate the significance of the associations. However, goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was not statistically fit; χ2(22) = 66.03, p < 0.001, AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) = 2173, BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) = 2220, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.24, TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) = -0.20, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.22. Therefore, the different new model was developed to improve the model fit (Fig. 2a). In the newly developed model, the goal was to explore how parents’ CM experiences are linked to later child maltreatment, with the final path directed toward child maltreatment risk. The new model showed a good fit; χ2(7) = 7.28, p = 0.41, AIC = 1466, BIC = 1493, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.03 (Fig. 2a). When examining the R2 values for each dependent variable, the overall R2 was 0.64, indicating that approximately 64% of the variance in the dependent variable was accounted for. This is considered a relatively high value, suggesting that the model provides a good overall fit. In this model, significant correlations were found between the total score of the CTQ and the SDS; β = 0.43, p < 0.01, and between affective empathy on the IRI and the SDS; β = 0.29, p < 0.05. Because the total score of CTQ and risk of child maltreatment are also significantly correlated; β = 0.58, p < 0.01, it is conceivable that traumatic experiences in childhood is positively related to risk of abuse being mediated by depressive symptoms. Next, the paths are implemented starting ACE as an adverse experience of childhood, and the model’s fit was found as good; χ2(7) = 6.48, p = 0.49, AIC = 1268, BIC = 1296, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.00 (Fig. 2b). The overall R2 for this model was 0.644, indicating a good fit. In this model, all the paths indicated significant correlations. First, there was a significant correlation between ACE and SDS; β = 0.43, p < 0.01. Next, both of cognitive empathy; β = 0.38, p < 0.01 and affective empathy; β = 0.34, p < 0.01 are significantly correlated with ACE which also showed significant relation with the risk of CM; β = 0.58, p < 0.01. Path analysis of this model indicated that affective empathy and depressive symptoms; β = 0.26, p < 0.05, can be mediating factors for the risk of CM. Even though the cortisol level were not affected by any of those variables, it significantly affected the risk of abuse; β = 0.20, p < 0.05.

Path analysis model based on hypothesis in mixed group from total scores of CTQ or ACE to CM being mediated by Depressive Symptoms, Cognitive Empathy, Affective Empathy, Cortisol, Parenting style Overreactivity and Parenting Style Laxness. Goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was not statistically fit; χ2(22) = 66.03, p < .001; AIC = 2173, BIC = 2220, CFI = .24, TLI = -.20, RMSEA = .22. Abbreviations: ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences, Childhood Trauma = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Depressive Symptoms = Self-rating Depressive Scale, Cognitive. Empathy = IRI Perspective Taking + IRI Fantasy Scale, Affective Empathy = IRI Empathic Concern + IRI Personal Distress, Cortisol = Salivary cortisol levels, CM = Risk of Childhood Maltreatment. The solid lines indicate statistically significant paths. **p < .01, *p < .05.

(a) Fitted path model in the mixed group from total scores of Childhood Trauma to CM being mediated (or not mediated) by Cognitive Empathy, Affective Empathy, Depressive Symptoms, and Cortisol. Goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was statistically fit; χ2(7) = 7.28, p = .41; AIC = 1466, BIC = 1493, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = .03. The solid lines indicate statistically significant paths, and the broken lines indicate the non-significant path. **p < .01, *p < .05. (b) Fitted path model in the mixed group from total scores of ACE to CM being mediated by Cognitive Empathy, Affective Empathy, Depressive Symptoms, and Cortisol. Goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was statistically fit; χ2(7) = 6.48, p = .49; AIC = 1268, BIC = 1296, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = .00. **p < .01, *p < .05.

As shown in Fig. 2a, the path starting with the CTQ did not show a significant relationship with either cognitive or affective empathy in the IRI. The lack of significance of the CTQ model (Fig. 2a) compared to the ACE model (Fig. 2b) might be attributed to the high correlation between the CTQ and ACE (r = 0.9), as well as the small sample size in this study.

Maltreatment group

As previously mentioned, adverse childhood experiences directly influenced the risk of CM, whereas affective empathy indirectly affected this risk through the mediation of depressive symptoms in the mixed group. Based on these results, paths developed from adverse childhood experiences to affective empathy, resulting in increased depressive symptoms in the maltreatment group. However, because all mothers in the maltreatment group had a history of maltreatment, the PS was used as the variable at the end of the path, instead of risk of child maltreatment. The model shown in Fig. 3 indicated a good model fit; χ2(3) = 2.60, p = 0.46, AIC = 407, BIC = 412, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA = 0.00. In this model, overall R2 was 0.20, and it explained little of the variance in the dependent variable. Although the model showed a good fit, the low R2 value may be attributed to the fact that many mothers in the maltreatment group had experienced CM, which could have led to various psychosocial consequences. Therefore, these factors, including potential psychological influences, may have interacted in a complex manner with the dependent variable. Data analysis showed significant correlations between the total CTQ score and affective empathy of IRI; β = 0.44, p < 0.05, and between affective empathy of IRI and SDS; β = 0.54, p < 0.01. Furthermore, there was a negative correlation between the SDS and total score of the PS; β = -0.59, p < 0.01. Even when the total PS score was replaced by the PS overreactivity subscale, it showed a significant negative correlation with the SDS; β = -0.51, p < 0.05. As the model fit was not significantly good if the paths were developed starting ACE as an adverse childhood experience, the model was not adapted. These results indicated that as depressive symptom scores increased, excessive parenting styles were alleviated. To delve deeper into these findings, we examined whether parenting styles varied among mothers in the maltreatment group according to the degree of their depressive symptoms. The results showed that mothers could be categorized into three groups based on their total SDS score, with the following cut-off points; mild (≤ 47), moderate (48–55), and severe (≥ 56). The mean SDS score for each group were as follows: mild (39), moderate (53), and severe (63), with a significant difference; F(2, 10) = 4.10, p < 0.05. When examining the relationships between these three groups and PS scores, it was found that the group with moderate depressive symptoms had the highest PS scores (79), followed by the mild (75) and severe (63) groups. This suggests that mothers with moderate depressive symptoms tend to adopt extreme parenting styles.

Fitted path model in the maltreatment group from total scores of Childhood Trauma to Parenting Style Total being mediated by Affective Empathy and Depressive Symptoms. Goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was statistically fit; χ2(3) = 2.60, p = .46; AIC = 407, BIC = 412, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA = .00. **p < .01, *p < .05.

Non-maltreatment group

The same model used for the maltreatment group was developed for the non-maltreatment group for comparison. The model shown Fig. 4 indicated a good model fit; χ2(3) = 3, p = 0.39, AIC = 1001, BIC = 1015, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA = 0.003. There was significant correlation between affective empathy of IRI and SDS; β = 0.33, p < 0.05. Similar to the results of the maltreatment group, the model fit was not significantly good if the paths were developed starting ACE as an adverse childhood experience. In this model, the overall R2 was 0.02, explaining little of the variance in the dependent variable. In the non-maltreatment group, the mothers generally had little to no history of CM; consequently, the CTQ did not influence affective empathy in this group. However, an important finding was that affective empathy was correlated with the SDS in both the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups. More importantly, in the maltreatment group, affective empathy, SDS, and parenting style were all found to be correlated with the CTQ. This suggests that it is not simply the level of affective empathy in parents that directly influences child maltreatment; in fact, the parents’ own experiences of maltreatment (as measured by the CTQ) affects their affective empathy, which in turn, influences parenting style through depressive symptoms. This insight demonstrates the significance of comparing this model between the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups.

Fitted path model in the non-maltreatment group from total scores of Childhood Trauma to Parenting Style Total being mediated (or not mediated) by Affective Empathy and Depressive Symptoms. Goodness of fit indices indicated that the model was statistically fit; χ2(3) = 3.00, p = .39; AIC = 1001, BIC = 1015, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA = .003. **p < .01, *p < .05.

Discussion

We employed path analysis to develop and analyze a model that elucidates the pathway from experiences of CM to parenting styles (to risk of CM for the mixed group) across all mothers. Our findings indicated that experiences of CM exerted a positive influence solely on the emotional dimension of empathy in both the mixed and maltreatment groups. Most individuals in the non-maltreatment group had no experience with CM and no significant correlation with empathy was found. This aligns with the findings of previous research17, indicating that experiences of abuse are one of the factors influencing the emotional aspect of empathy. By conducting correlation analyses between the subscales of abusive experiences and empathy across all groups, we found significant correlations between the ACEs, CTQtotal, CTQEmotional, CTQEmotional, CTQPhysical Neglect, and PD of IRI. These results are also consistent with those of previous studies13,15 showing that various forms of earlier maltreatment inflict PD on mothers. As the personal distress subscale of the IRI refers to a self-centered and maladaptive emotional reaction to the negative emotions of others, an increase in PD is believed to be associated with social dysfunction, fear, emotional vulnerability, instability, anxiety, and discomfort in social life23. Therefore, experiencing CM might intensify PD, resulting in heightened susceptibility to emotional unease, thereby potentially contributing to the risk of child maltreatment.

The results of this study did not show a decline in cognitive empathy, which contradicted the findings of a previous study14. One plausible explanation for this could be attributed to the impact of cognitive empathy, also known as “interpersonal guilt.” Tone and Tully outlined how empathy can lead to internalized issues, such as depression, pointing to the significant roles of PD and interpersonal guilt in this process7. PD is a self-focused and maladaptive affective response to the negative emotions of others, accompanied by physiological hyperarousal and behavioral withdrawal24. Interpersonal guilt, on the other hand, is a maladaptive form of cognitive empathy such as the unreasonable belief that one is responsible for alleviating the suffering of others or worries about causing harm to others25. Interpersonal guilt and PD have been shown to be connected to several adverse outcomes, notably anxiety and depression26. Moreover, interpersonal guilt is considered to develop in childhood amidst familial negative relational interactions27, and therefore, has been suggested that it could result from traumatic and adverse developmental experiences28. Considering that parents in the maltreatment group experienced an upbringing in a more adverse environment and exhibited higher levels of depressive symptoms than non-maltreatment parents, it is conceivable that their heightened interpersonal guilt might have mitigated the decline in cognitive empathy.

Another possible explanation for the lack of decrease in cognitive empathy in this study could be the influence of FA (Fantasy Scale). In the path analysis, empathy was operationalized as affective empathy (PD and EC) and cognitive empathy (PT and FA). However, when conducting t-tests on each subtype of empathy between the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups, it was found that the FA scores were higher in the maltreatment group than in the control group. As mentioned earlier, the fantasy scale measures the tendency to identify with characters in movies, novels, plays, and other fictional situations29,30 and was also found to have a statistically significant correlation with empathy for real people as well31. However, despite their elevated FA scores, mothers in the maltreatment group engaged in abusive behavior. Given that this study also identified higher levels of PD in mothers in the maltreatment group than those in the non-maltreatment group, it is essential to contemplate how these factors interact to potentially impair empathy, resulting in dysfunctional empathetic responses.

Regarding this matter, the previous studies have investigated the role of fantasy in cognitive process known as metacognition32. Metacognition is defined as the cognitive ability to impartially observe one’s internal experiences and emotional occurrences and encompasses functions such as “Clarity” (understanding one’s emotions) and “Repair” (emotion regulation). Nomura and Akai conducted research on the impact of fantasy on clarity (emotional understanding) and repair (regulation), and the results demonstrated that fantasy had a significant positive correlation with Repair, with PD identified as a mediating factor in this relationship31. In other words, while higher Fantasy Scores generally promoted cognitive regulation, PD mitigated this effect. Therefore, while mothers in the maltreatment group exhibited higher fantasy scores than did non-maltreated mothers, elevated PD among mothers in the maltreatment group potentially mitigated the functional aspects of fantasy.

The results of this study demonstrated that depressive symptoms were amplified by affective empathy, influenced by experiences of maltreatment in both the mixed and maltreatment groups. In addition, a positive correlation was found between affective empathy and depressive symptoms in the non-maltreatment group. This suggests that increased affective empathy may elevate the risk of depression, irrespective of mothers’ maltreatment experiences. However, previous research has shown that PD is not only positively correlated with traits such as anxiety, but it also has a negative relationship with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale23. Therefore, further research considering the presence of mediating factors other than depression, as demonstrated in this study, is necessary to understand the process of adverse experiences to perpetrate maltreatment.

In this study, a notable correlation was observed exclusively within the maltreatment group: affective empathy showed a significant association with depressive symptoms, which in turn showed a significant correlation with parenting styles. The results suggest the potential for intergenerational transmission of maltreatment, specifically from a mother’s experience of maltreatment to abusive behavior toward her children. Conversely, the results indicated that mothers with moderate depressive symptoms exercised the most excessive discipline strategies. Although this finding implies that the intensity of depression results in differences in the excessiveness of parenting, all mothers in this group had a history of maltreatment, and this research could not infer the risk of maltreatment from the differences in depression severity and parenting style. According to the previous research, mothers with high depressed affect and physical profiles demonstrated higher levels of harsh parenting33. However, this study targeted mothers at risk but did not investigate mothers who had actually engaged in maltreatment. Thus, future research could provide valuable insights into the intergenerational transmission of CM by investigating the impact of depression severity and its manifestations through a comparative study of mothers’ childhood experiences on their actual parenting practices.

This study provides valuable insights into the correlation between mothers’ adverse childhood experiences and parenting style. However, some of its limitations should be acknowledged. First, all data, except salivary cortisol levels, were obtained using self-reported measures. The questionnaires used in this study contain highly intrusive inquiries, including questions on adverse personal experiences and depressive tendencies. Furthermore, a significant number of mothers in the maltreatment group experienced severe depressive symptoms, raising the possibility of response bias34. Second, no significant difference in salivary cortisol levels was observed between the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups; p = 0.07. The small number of mothers in the maltreatment group and the fact that only a single measurement session was conducted may have influenced the results. Finally, the sample size was small, as the study focused on mothers who had engaged in child maltreatment. However, while the sample size was constrained, the ability to conduct research with such a specific group is a strength of this study. Additionally, the sample size followed the rule of thumb, with a ratio of approximately 1:5 between the number of estimated parameters and the sample size; this value is acceptable when the model does not include latent variables35. However, given the low R2 values for both the maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups, increasing the sample size could allow for the exploration of models with better fit.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that in both mixed group of mothers and the maltreatment group, affective empathy increased as the severity of CM experiences intensified. CM experiences were found to influence affective empathy, which is consistent with previous research. Furthermore, in all three groups, affective empathy was shown to exacerbate depressive symptoms and contribute to an increased risk of child maltreatment. Finally, in the maltreatment group, significant correlations were found between affective empathy, depressive symptoms, and parenting style, suggesting the possibility of intergenerational transmission of CM.

Methods

Statements

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Fukui, Japan (approval nos. 20150068, 20160120, 20220034, and 20220039). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

A total sample of 55 mothers, aged 25 to 50 years (M = 41.3, SD = 5.4), participated in this research. Of the total sample, 13 mothers (M = 40.4, SD = 7.5) were recruited as mothers who engaged in child maltreatment. These mothers were referred to our laboratory by pediatricians and child psychiatrists, based on the research criterion, which was defined as a current or past history of social interventions by the Child Protective Services (CPS) due to child maltreatment36. Owing to the nature of this study, information regarding the sources of participant recruitment cannot be disclosed. All maltreating mothers underwent physical, emotional, and/or neglect assessments by pediatricians and child psychiatrists before intervention by CPS. The ages of their children ranged from 6 to 15 years (M = 11.2, SD = 2.9). After the CPS intervention, the three children lived in local child welfare facilities, which are considered a stable environment. One child lived with a non-abusive caregiver after a temporary stay at a CPS facility. The three children currently stay with their abusive parents with follow-up observations after being taken into protective custody. The remaining six children remained with their parents during the follow-up observation without being taken into protective custody. Nine maltreating mothers had psychiatric disorders, and six mothers were on medication. Among those nine mothers, three of them had depression, two had obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and one of them had complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Two maltreating mothers had ADHD, whereas the others had both ADHD and ASD. The details of the symptoms and seriousness of these disorders are unclear. No medication washout was requested for participation in this study because of the potential risks that might be caused to these mothers.

Forty-two mothers in the control group were age-matched with the maltreatment group (M = 41.6, SD = 4.7), and participated in our longitudinal cohort study for child development in the general population. Their children were aged between 8 and 9 years (M = 8.5, SD = 0.6). All the participants were informed of the general aims of the study, which centered on exploring the formation of mother–child attachment or relationship, while specifically refraining from using the terms “abuse” or “neglect.” The exclusion criterion for this study was a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, or perinatal or neonatal complications.

Psychological measures

ACE (Adverse childhood experience)

The ACE is a retrospective and prospective assessment of the long-term impacts of CM and household dysfunction during childhood. Items of ACE consist of seven categories of adverse childhood experiences that are psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against mother; or living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill or suicidal, or ever imprisoned with a higher total score indicating more severe adverse experiences37. Cronbach’s alpha for the ACE showed an acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.70)38. Felitti also reported associations between childhood abuse and adult health-risk behaviors and diseases39. Therefore, childhood experiences should be recognized and investigated as early as possible to minimize their negative impact on both children and adults. In this study, we investigated the relationship between the severity of mothers’ adverse childhood experiences and their maltreatment behaviors to better understand the mechanisms of the generational cycle of CM.

CTQ-J (Childhood Traumatic Questionnaire of Japanese version)

Childhood traumatic experiences were assessed using the Japanese version of the CTQ. The original CTQ scale was developed by Bernstein et al., who defined 5 different types of childhood abuse and neglect40. The CTQ-J is a self-report instrument covering 28 items that rates the severity of psychological abuse/neglect, physical abuse/neglect, and sexual abuse experienced during childhood and adolescence using a 5-point Likert scale. The CTQ total score was used for path analysis. The scale ranged from 0 (“never true” to 5 “very often true”). Cronbach’s alpha for the factors ranged from 0.79 to 0.94, indicating high internal consistency29. While the ACE provides a relative measure of abuse severity, the CTQ, with its subscales, offers a more detailed assessment of the nature of CM. Therefore, both scales were administered to gain a deeper understanding of parents’ experiences of being abused.

IRI (Interpersonal reactivity index; Japanese Version)

Davis first developed the IRI to measure empathy41. IRI Japanese version consisting of 28 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale was used in this study30. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the subscales were as follows, PD; α = 0.76, EC; α = 0.77, FS; α = 0.76, and PT; α = 0.75, showing high internal consistency42. The IRI assumes that empathy comprises multiple cognitive and affective aspects. The cognitive aspect consists of two subscales: the perspective-taking and fantasy scales. The affective aspects of IRI include empathy and PD. The Perspective-Taking Scale assesses efforts to take the perspectives of other people and understand their points of view. The fantasy Scale measures a person’s tendency to identify with characters in movies, novels, plays, and other fictional situations. Regarding the affective aspects of the IRI, Empathy Concern assessed respondents’ feelings of warmth and concern for others. PD of IRI measures the tendency of respondents to feel anxious and uncomfortable when observing another’s suffering43. IRI is one of the most utilized measurements for empathy in the world and was used in this study to determine whether current empathetic traits differ between maltreating mothers and non-maltreating mothers.

SDS (Self-rating depression scale)

Empathy does not always result in positive outcomes. In fact, recent research has shown a possible relationship between empathy and depression44. Yan, Zeng, Su, and Zhang indicated that empathy improves not only emotion recognition but is also contagious with both positive and negative feelings45. Therefore, empathic reactions to others’ distress might result in PD, which can lead to internalizing problems, such as depression46. Given these findings, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms could be a mediating factor between adverse experiences in childhood and empathy and evaluated this possibility.

The SDS was used to assess mothers’ subjective views of depressive symptoms. This scale was developed by Dr. William WK Zung and has been widely employed in various settings in Japan, demonstrating high internal consistency (α = 0.93)47. It consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point frequency scale from 1 (none or some of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). It ranges from mild to moderate, moderate to severe, and severe depression of over 50 years. The number of items on this scale is relatively small, and the burden on mothers to undergo the assessment can be minimized. Considering its validity and cost-effectiveness, SDS was used in this study.

PS-J (Parenting Scale Japanese version)

Parenting Scale (PS-J) was developed by Arnold O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker to measure dysfunctional discipline practices in parents of young children48. Cronbach’s alphas for overreactivity (α = 0.86) and laxness (α = 0.68) were sufficient49. The Japanese version of the Parenting Scale was used in this study. The PS-J consists of 30 items with a two-factor structure comprising laxness (parents have highly permissive and inconsistent parenting strategies) and overreactivity (parents have harsh, impulsive, and aggressive discipline strategies). Each item measures parenting behavior in response to problematic child behavior on a 7-point scale. In this scale, 7 is the “ineffective” end of the item and 1 indicates a high probability of using an effective discipline strategy. We compared the mothers’ parenting strategies to investigate their effects on CM.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software 18.0, applying the maximum likelihood estimation for missing data. The mothers were categorized into maltreatment or non-maltreatment groups. Participants’ demographics, clinical characteristics, and cortisol levels were compared using chi-squared (χ2) test, and t-test for each group to examine the differences between the two groups. All key study variables were assessed for significant correlations using Pearson’s correlation. Path analysis was conducted to estimate pathways that were consistent with previously developed conceptual frameworks and theories. These pathways delineate the trajectory from adverse childhood experiences to maltreatment and explore their correlations with variables such as affective and cognitive empathy, depressive symptoms, and parenting style. In this path analysis, the mothers were categorized into three groups: a mixed group (consisting of maltreating and non-maltreating mothers), a maltreatment group, and a non-maltreatment group. Models were developed for each group and analyzed for goodness of fit.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the risk of subject identification, subjects whose anonymity should be carefully protected. However, the data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests. Our study did not include minors as subjects.

References

Narisawa, M., Kezuka, K. & Toma, K. A review of quantitative research on child maltreatment: Issues and suggestions for future research. Working paper. https://ipss.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/2000230 (2024).

Aida, R. & Okawara, M. Cognition of being victimized and the intergenerational chain behind child abuse: Influence of invalidation of negative emotion and somatic sensation by mothers on difficulty of child rearing. Cinii. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1050006994041446400 (2014).

Rosenstein, P. Parental levels of empathy as related to risk assessment in child protective services. Child Abuse Negl. 19, 1349–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(95)00101-d (1995).

Berzenski, S. R. & Yates, T. M. The development of empathy in child maltreatment contexts. Child Abuse Negl. 133, 105827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105827 (2022).

Decety, J. The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Dev. Neurosci. 32, 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317771 (2010).

Decety, J. The neuroevolution of empathy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1231, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06027.x (2011).

Tone, E. B. & Tully, E. C. Empathy as a “risky strength”: A multilevel examination of empathy and risk for internalizing disorders. Dev. Psychopathol. 26, 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414001199 (2014).

Israelashvili, J., Sauter, D. & Fischer, A. Two facets of affective empathy: Concern and distress have opposite relationships to emotion recognition. Cogn. Emot. 34, 1112–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1724893 (2020).

Richardson, D. R., Hammock, G. S., Smith, S. M., Gardner, W. & Signo, M. Empathy as a cognitive inhibitor of interpersonal aggression. Aggress. Behav. 20, 275 (1994).

Thoma, P., Friedmann, C. & Suchan, B. Empathy and social problem solving in alcohol dependence, mood disorders and selected personality disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 448–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.024 (2013).

Dittrich, K. et al. Alterations of empathy in mothers with a history of early life maltreatment, depression, and borderline personality disorder and their effects on child psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 50, 1182–1190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001107 (2020).

Tomoda, A. et al. The neurobiological effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function, and attachment. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 11, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-024-01779-y (2024).

Parlar, M. et al. Alterations in empathic responding among women with posttraumatic stress disorder associated with childhood trauma. Brain Behav. 4, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.215 (2014).

Oura, S., Matsuo, K. & Fukui, Y. Does childhood abuse really reduce empathy? Internal working models of attachment as a mediator. J. Health Psychol. Res. 32, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.11560/jhpr.180524101 (2019).

Perez-Albeniz, A. & de Paul, J. Dispositional empathy in high- and low-risk parents for child physical abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 27, 769–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00111-x (2003).

Meidan, A. & Uzefovsky, F. Child maltreatment risk mediates the association between maternal and child empathy. Child Abuse Negl. 106, 104523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104523 (2020).

Benz, A. B. E. et al. Increased empathic distress in adults is associated with higher levels of childhood maltreatment. Sci. Rep. 13, 4087. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30891-7 (2023).

Fei, W. et al. Association between parental control and subclinical depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen: Roles of empathy and gender. J. Affect. Disord. 286, 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.005 (2021).

Li, Y. & Seng, J. S. Child maltreatment trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cortisol levels in women: A literature review. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 24, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317710313 (2018).

Kuhlman, K. R. et al. Childhood maltreatment and within-person associations between cortisol and affective experience. Stress 24, 822–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2021.1928069 (2021).

Vergara-Lopez, C., Chaudoir, S., Bublitz, M., O’Reilly Treter, M. & Stroud, L. The influence of maternal care and overprotection on youth adrenocortical stress response: A multiphase growth curve analysis. Stress 19, 567–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2016.1222608 (2016).

Wagner, S. L. et al. Higher cortisol is associated with poorer executive functioning in preschool children: The role of parenting stress, parent coping and quality of daycare. Child Neuropsychol. 22, 853–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2015.1080232 (2016).

Himichi, T. et al. Development of a Japanese version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Jpn. J. Psychol. 88, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.88.15218 (2017).

Zahn-Waxler, C. & Van Hulle, C. Empathy, guilt, and depression: When caring for others becomes costly to children. In Pathological Altruism (eds Oakley, B. et al.) 321–344 (Oxford Academic, 2012).

O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., Weiss, J. & Gilbert, P. Guilt, fear, submission, and empathy in depression. J. Affect. Disord. 71, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00408-6 (2002).

O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W. & Weiss, J. Interpersonal guilt, shame, and psychological problems. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 18, 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1999.18.2.181 (1999).

Shilkret, R. & Silberschatz, S. A developmental basis for control-mastery theory. In Transformative Relationships: The Control-Mastery Theory of Psychotherapy (ed. Silberschatz, G.) 171–187 (Routledge, 2005).

Fimiani, R., Gazzillo, F., Fiorenza, E., Rodomonti, M. & Silberschatz, G. Traumas and their consequences according to control-mastery theory. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 48, 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2020.48.2.113 (2020).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry 151, 1132–1136. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 (1994).

Akeda, Y. On a framework for measures of empathy: An organizational model of empathy by Davis and a preliminary study of a multidimensional empathy scale (IRI-J). Psychological Report of Sophia University 23, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.11501/3471208 (1999).

Nomura, K. & Akai, S. Empathy with fictional stories: Reconsideration of the fantasy scale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Psychol. Rep. 110, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.07.09.11.PR0.110.1.304-314 (2012).

Shiota, S. & Nomura, M. Role of fantasy in emotional clarity and emotional regulation in empathy: A preliminary study. Front Psychol. 17(13), 912165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.912165 (2022).

Guyon-Harris, K. L., Taraban, L., Bogen, D. L., Wilson, M. N. & Shaw, D. S. Individual differences in symptoms of maternal depression and associations with parenting behavior. J. Fam. Psychol. 36, 681–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000988 (2022).

Hunt, M., Auriemma, J. & Cashaw, A. C. A. Self-report bias and underreporting of depression on the BDI-II. J. Pers. Assess. 80, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_10 (2003).

Bentler, P. M. & Chou, C. P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 16, 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004 (1987).

Kurata, S. et al. White-matter structural features of maltreating mothers by diffusion tensor imaging and their associations with intergenerational chain of childhood abuse. Sci. Rep. 14, 5671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53666-0 (2014).

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 (1998).

Oláh, B. et al. Validity and reliability of the 10-Item Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-10) among adolescents in the child welfare system. Front Public Health 11, 2296–2565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1258798 (2023).

Felitti, V. J. The relation between adverse childhood experiences and adult health: Turning gold into lead. Perm. J. 6, 44–47. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/02.994 (2002).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 27, 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0 (2003).

Davis, M. H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 10, 85 (1980).

Davis, M. H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 (1983).

Tully, E. C. & Donohue, M. R. Empathic responses to mother’s emotions predict internalizing problems in children of depressed mothers. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 48, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0656-1 (2017).

Yan, Z., Zeng, X., Su, J. & Zhang, X. The dark side of empathy: Meta-analysis evidence of the relationship between empathy and depression. PsyCh. J. 10, 794–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.482 (2021).

Russell, M. & Brickell, M. The, “double-edge sword” of human empathy: A unifying neurobehavioral theory of compassion stress injury. Soc. Sci. 4, 1087–1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4041087 (2015).

Zung, W. W. K. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 12, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 (1965).

Glenn, L. E. & Pepper, C. M. Reliability and validity of the self-rating scale as a measure of self-criticism. Assessment 30, 1557–1568. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221106768 (2022).

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S. & Acker, M. M. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychol. Assess. 5, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.137 (1993).

Itani, T. The Japanese version of the parenting scale: Factor structure and psychometric properties. Jpn. J. Psychol. 8, 446–452. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.81.446 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff at the Research Center for Child Mental Development; the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychological Medicine, University of Fukui Hospital; and Ms. Madoka Umemoto for their clerical support.

Funding

All phases of this study were supported by AMED (20gk0110052, AT and SN), JSPS KAKENHI Scientific Research (A) (19H00617 and 22H00492, AT), (C) 22K02432 (SK and SN), and University of Fukui Research Farm-Firm, University of Fukui (SK), a research grant from the Strategic Budget to Realize University Missions (AT), a Grant-in-Aid for Translational Research from the Life Science Innovation Center, University of Fukui (AT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X.F., Y.K., and A.T. were involved in the conception and design of the study. S.K., N.Y.S., A.Y., S.N., and A.T. performed the experiments and collected the samples. Y.K. drafted the manuscript with critical revisions and supervision from T.X.F. and A.T. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawaguchi, Y., Kurata, S., Kawata, N.Y.S. et al. Effects of childhood maltreatment on mothers’ empathy and parenting styles in intergenerational transmission. Sci Rep 15, 7787 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92804-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92804-0