Abstract

In this work, a detailed chemical and crystallographic analysis of basic logic and a few selected intermediate RESET states of Ge-rich Ge-Sb-Te-based (GST) phase-change memories (PCM) is presented, with a particular focus on the understanding of the microscopic mechanisms underlying their electrical characteristics. We demonstrate that Ge-rich GST-based PCM store the information not only in their crystalline or amorphous phase, as in conventional PCM based on Ge2Sb2Te5, but also in their active material stoichiometries: the amorphous phase is characterized by a Ge-rich composition, guaranteeing automotive-compliant retention, while the crystalline phase shows a composite structure, made of cubic GST and rhombohedral Sb grains, the latter mostly found close to the heater. This switching of composition explains the high temperature retention capability of Ge-rich GST cells and their preserved good functionality in the high conductive state. Analysis of intermediate RESET states unveils the microscopic details of these physical and chemical transitions, giving insights on the physical origin of the electrical characteristics of Ge-rich GST-based PCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the increasing need for multiple distributed data-near sites, known as Edge Computing, in the past years the demand for high performance microcontrollers has increased1. In this framework, PCM are among the most promising emerging technologies to enter the embedded memory market for consumer and automotive applications. In fact, thanks to their scalability and ease of integration in the back-end-of-line (BEOL), PCM are considered as valid replacement of classical flash-based approaches2.

PCM are composed of ternary alloys, commonly Ge-Sb-Te-based (GST). Their main characteristic is the ability to make repeatable transitions between the amorphous and crystalline phases, that show large electrical conductivity contrast. This feature allows to use these materials for memory applications, where the reading of the two different states is obtained by measuring their conductivities: the amorphous is the low conductive state and the crystalline the high conductive one. The writing mechanism is based on Joule heating generated by high density currents through the device. By applying current pulses of appropriate amplitudes and shapes it is possible to reversibly switch from one state to the other3. The active region of the device can be brought above the melting temperature then quenched resulting in the formation of the amorphous phase (RESET pulse) or above the crystallization temperature for a sufficient time (SET pulse) to recrystallize it.

Nevertheless, the conventional phase-change materials are not compatible with the specifications of high temperature data retention dictated by the automotive and consumer markets. In fact, standard Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST-225) has a low crystallization temperature (about 150 °C when measured with Differential Scanning Calorimetry3,4), not suitable to guarantee the 2 years at 150 °C required for automotive applications and the 2 min at 260 °C from soldering reflow compliance as per JEDEC specifications4. For this reason, Ge-rich GST (GGST) alloys have been developed, satisfying tough data retention requirements5,6,7,8,9 and becoming very promising materials for both the next-generation microcontrollers (28 nm MOS technology)6,7 and for advanced smart-power components (90 nm MOS technology)5. In fact, being out-of-stoichiometry materials, their crystallization mechanism involves a two-step process: at first a phase separation step, where excess Ge is expelled from the amorphous matrix, followed by the sequential crystallization of different phases. At the end, a material with a composite structure is obtained, with grains of distinct compositions within which GST-225 and Ge prevail10,11. It is this prior phase separation process which slows down the overall thermal crystallization of the alloys, guaranteeing the observed higher crystallization temperature (i.e., 370 °C with a ramp rate of 10 °C/min)11,12. As a consequence, RESET programmed state exhibits higher activation energy of crystallization than classical GST-225 (i.e., 3.1 eV for GGST vs 2.6 eV for GST-225) and excellent retention behavior, compliant with automotive and consumer markets’ requirements13,14. The high atomic diffusivities of the constituting elements and the out-of-stoichiometry composition of the deposited material play a role also during the programming of such states, ending up with basic logic states characterized by different chemical compositions and microscopic structures. Due to the high Ge content introduced in the alloy, a forming operation is needed before any programming to prepare the material in the proper way. The role of the forming step, defined by the level of peak current of the applied pulse, is to standardize the electrical response of the cells. Before forming, out of fab material is polycrystalline with small grains of various phases including Ge aggregates unevenly distributed across the layer, due to the stochastic nature of the thermal crystallization resulting from the BEOL process. These different distributions impact the percolative conduction path between the cell’s electrodes and lead to a high median value of the resistance distribution, with a spreading ranging over multiple decades. After forming, Ge aggregates are removed from the programmed region, the size of which depends on the peak current of the applied pulse, called “active area” from now on, reducing the resistance median value and the spread9,15,16.

The scope of this work is to study the origin and the physics behind the functionality of these GGST PCM cells. A full chemical and crystallographic characterization of basic logic and of a few selected intermediate RESET states of GGST-based PCM is performed to reveal the microscopic origin that enables GGST alloy to be a suitable material for consumer- and automotive-grade memory applications. Since the electrical characteristics of the RESET and SET states remain similar for GGST cells fabricated across all the technology nodes, the present work looks across different technology nodes (i.e., 90 and 28 nm) without focusing on the performance of a specific scaling node. This complete physical analysis is performed in parallel to the study of the electrical characteristics of GGST cells to infer from this comparison the microscopic mechanisms at work in the GGST PCM during programming. In the end, this work will show that GGST-based PCM results in a memory where the information is stored not only in the crystallinity or amorphousness of some active area but also in its stoichiometry, giving it the capability to satisfy high temperature data retention specifications without disruptive impact on the programming speed and functionality.

Results and discussion

Electrical characterization

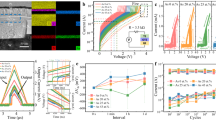

Figure 1 reports electrical characterization of GGST PCM in 90 nm technology, showing phase switching between the crystalline and amorphous states. In Fig. 1a,b R-I and I-V characteristics for three levels of forming current, i.e. I3 < I4 < I5, are reported, respectively. They represent the median curves over a population of about 50 devices, where dots are experimental data and lines are interpolations. Device-to-device variability is very low for all the resistive states considered; for each programming point the resistance distribution dispersion is contained below 15% of the corresponding median. These results are in line with the industry specifications6,7. After characterization of the devices, with I-V and R-I curves acquisition, the cells were programmed first with a forming pulse and then, when needed, RESET pulses of appropriate magnitude to conduct the physical analysis. The full acquisition procedure is reported in the “Methods” section. As shown in Fig. 1a, at Iprog = 0 GGST cells are in the forming low resistance state and then they can be programmed to various RESET states, with resistances across two orders of magnitude above the forming one. As schematically reported in the insets of Fig. 1a, the forming pulse is characterized by a fast rising edge of few ns, by a plateau of about 100 ns with a peak current able to melt locally the GGST, and then by a slow trailing edge of about few µs, designed to give the material enough time to re-order and crystallize. On the contrary, the RESET pulse, after the same rising edge and plateau of the forming pulse, is followed by steep trailing edge of few ns during which the melted area is quenched. When the peak current of the RESET pulse is equal to the current of the forming pulse, the obtained state, corresponding to the highest resistance point in the R-I characteristic, is called “full RESET”. For RESET currents below the forming one, the obtained states are called intermediate RESET states (IRS), with resistance values between the forming and the full RESET ones. The first IRS is represented by the “melting reference point” (reported as Im for the I4 R-I curve), and it is obtained with a current that allows to reach a resistance value of about 1.2 times the resistance value of the forming state.

electrical characterization of GGST-based PCM in 90 nm technology: (a) R-I characteristics for three levels of forming currents: I3 < I4 < I5. Bigger dots represent experimental points physically analyzed in the next subsections. In the inset, sketches for forming and RESET pulses are reported with dotted black lines indicating corresponding resistance states; (b) I-V characteristics for three levels of forming currents: I3 < I4 < I5.

Comparing the different R-I curves, it is evident that the melting points and the programming currents shift towards higher values for increasing levels of forming. This phenomenon, typical of GGST PCM, is called “walk-in” effect and it is linked to the increasing size of the active area created by forming, as it will be shown in the following. In fact, being the size of the active area monotonously modulated by the forming current level, higher RESET currents are required to melt the same relative portion of active area across the different forming currents15,16.

In this work, a detailed physical analysis of forming, IRS and full RESET states has been performed. In particular, in the subsection “Forming and RESET states” chemical and crystallographic analysis of forming and full RESET state for a reference value of forming current are reported (see big blue dots in Fig. 1a with the lowest and highest resistances, respectively). The reference forming current, corresponding to the I4 blue curve in Fig. 1, is defined as the condition optimizing the overall device performance. Then, in the subsection “Chemical analysis of intermediate and full RESET states” full chemical analysis of IRS and full RESET states is presented. The focus of the subsection is the comparison of the RESET states composition in the 90 nm technology, where the IRS correspond to the intermediate big blue dots on I4 curve of Fig. 1a, while the full RESET states to the big red, blue and green dots on I3, I4 and I5 curves of Fig. 1a, respectively. Lastly, in the subsection “Crystallographic analysis of intermediate and full RESET states” parallel crystallographic analysis of IRS and full RESET states in the 28 nm technology is reported.

Forming and RESET states

Figure 2 shows physical and chemical characterization of forming and full RESET states for the reference forming current in the 90 nm technology, i.e. I4. In particular, Fig. 2a compares Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy-dark field (STEM-DF) images of the two states, showing that the forming is characterized by a typical polycrystalline structure, while the RESET state exhibits a dome-shaped amorphous region, as classically observed in all chalcogenide-based PCM cells. More intriguing are the corresponding Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) maps reported in Fig. 2b. In fact, and as highlighted by RGB-coded colors, the cells after forming and in the full RESET state have very different chemical characteristics. The forming state exhibits a composite chemical structure characterized by three sub-regions with different compositions that we identify as “core”, “shell” and “amorphous-layer” (α-layer) regions. In contrast, the amorphous dome of the RESET state shows a homogeneous composition. Moreover, the EELS Sb maps (Fig. 2c) show that a Sb-depleted region (see red dashed line) exists both after forming and in the full RESET state. This chemically modified region is about two times the size of the active area and remains crystalline after full RESET. To study the composition of each region included in the active area in more detail, scatter plots of the Sb vs Ge EELS signals can be drawn, as reported in Fig. 2d. While the RESET state shows a compact distribution centered around one precise accumulation-point, matching the amorphous dome composition, the active material after forming is characterized by a spread distribution with multiple accumulation points at specific locations (i.e., the core, shell and α-layer regions). The remaining parts of the pixel distributions for both states correspond to the GGST material surrounding the active areas, and have been analyzed in previous works17,18,19.

physical and chemical characterization of GGST-based PCM of the forming (I4) and full RESET states in 90 nm technology: (a) STEM-DF images where white dotted line shows the extension of the amorphous dome. Scale bars reported in the bottom left of the figures hold the same relative size for all the manuscript for the sake of comparison; (b) EELS maps using a RGB color-code proportional to the [Ge, Sb, Te] % contents (where Ge is reported in red, Te in blue and Sb in green). White dotted lines show the extension of the active area and of related sub-regions. Yellow circle highlights the location of α-layer; (c) Sb signal maps where white dotted lines show the extension of the active area while red dashed lines show the Sb-depleted region; (d) Sb vs Ge scatter plots using a color-code proportional to the distance from the heater according to the legend reported in the inset. Colored circles show active regions of interest.

We believe that this peculiar chemical and micro-structure observed after forming is linked to the electric field and temperature gradient experienced by the cell during the forming pulse20. Indeed, during the slow trailing edge following melting, the temperature gradient gradually shrinks following the slope of the forming pulse, causing the progressive cooling down of the outer parts of the active area21,22. This gradual evolution of the temperature gradient triggers the early segregation of the element having the highest solidification temperature outside of the active area, and the consecutive crystallization in “radial slices” of the other elements, based on the respective values of their solidification temperatures. Thus, as Ge has the highest solidification temperature (about 900°C) and is in excess with respect to the regular stoichiometry of stable GST alloys, it is firstly expelled in quantity out of the active region23, leaving Te and Sb available to participate in the crystallization of grains in the region. Next to this, the observation that Sb segregates only very close to the heater is very probably induced by the electrical field. Indeed, it is well known that Sb+ can be dragged by the strong electric field of the programming pulse toward the cathode (i.e., the heater)24,25,26,27. The latter effect thus splits the active area into two regions: the core, extremely enriched in Sb, and the shell, rich in Te, as Sb has drifted out of the region. The effect of the electrical field on Sb is confirmed by the Sb-depleted region surrounding the active area. This area is slightly larger than the region which was melted at the beginning of the forming pulse (i.e., the active area), meaning that the diffusion of Sb also affects the crystalline regions surrounding the active area 24,25,26. The presence of this Sb-rich core, Sb being the most conductive element of the GST ternary compound, explains the GGST PCM functionality despite the large amount of Ge introduced inside the material ([Ge] > 50%): Sb enrichment of heater contact area is able to sustain a proper conductivity in the forming high conductive state. Nevertheless, we have evidenced that an amorphous Ge-rich layer (i.e., α-layer) is formed below the Sb-rich core of the active area, in direct contact with the heater. We suspect that, as the active area solidifies and crystallizes during the trailing edge of the forming pulse, some Ge remaining in the region is expelled from it, at the end of the dragging process. Having a very small thickness (< 5 nm), this α-layer still allows proper conductivity of the cell. The impact of these amorphous residues on the characteristics of GGST cells can be assessed by studying the behavior of conduction of a cell in the high conductive state as a function of temperature, as discussed elsewhere13,28.

In contrast to the forming state, the active area of the full RESET state is characterized by a narrow and well centered distribution of the pixels in the elemental scatter plot (Fig. 2d right). The spread of this distribution is narrower than the one obtained in any of the aforementioned regions defining the active area of the forming state. This feature reflects the chemical homogeneity and well-defined composition of the amorphous dome of the full RESET state, which results in a resistance two orders of magnitude higher than the forming one, as reported in Fig. 1a. Moreover, as evidenced in the scatter plot, the composition of the full RESET state is enriched in Ge with respect to the one of the forming Sb-rich core. This is the key for the robust thermal stability of the programmed GGST-based PCM, as stated in the Introduction and deeply studied in previous works13,14. In summary, GGST PCM undergo not only phase switching, as classical PCM made by GST-225, but also compositional transition, between a crystalline phase based on a highly conductive element (i.e., Sb-rich core), and an amorphous state enriched in Ge. This compositional transition ensures both high RESET retention performances and proper SET conductivity.

As observed at the beginning, since forming of the cells results in the formation of a polycrystalline structure, additional crystallographic analysis is required to identify the crystalline phases that have been formed in the different sub-regions showing distinct chemical compositions. As detailed in the supporting information (Figs. S1 and S2), grains of three crystalline phases, cubic Ge, cubic GexSbyTez (simplified as “GST” hereafter), and rhombohedral Sb can be eventually found in GGST thin films and PCM cells, which can be differentiated and identified by selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and associated DF imaging. This allows us to generate “crystallography maps” in which the grains belonging to each phase can be located in the same cell.

Figure 3c–e shows such crystallographic maps of Ge, GST, and Sb, respectively, obtained on cells fabricated in 28 nm technology after the application of a forming pulse with technology’s reference current. We first note that, although being fabricated along two different technology nodes, the cells show the same characteristics, i.e. a Sb-rich core and a Sb-depleted surrounding (see EDX map in Fig. 3a). DF-Ge images show that Ge grains are mostly found at the periphery of the active area and only marginally inside it. GST crystals are also found at the periphery, which together with Ge grains, define the polycrystalline environment surrounding the active area. Moreover, specific DF-GST images show that some of the GST grains extend all the way from the periphery of the active area and deep into it (like the green and blue grains in Fig. 3d). This demonstrates that during the crystallization phase of the forming pulse (trailing edge), GST grains have regrown epitaxially from the grains located at the interface to the melt into the active area. In addition to Ge and GST grains, the SAED pattern (Fig. 3b) and associated DF-Sb images show the presence of small rhombohedral “pure” Sb grains, exclusively located in the Sb-rich core of the active area, close to the heater. Together, these results show that the core region consists in a mixture of grains of the rhombohedral Sb and cubic GST phases.

chemical and crystallographic characterization of a GGST cell in 28 nm technology after forming: (a) The Sb-map obtained by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) is shown, where the white dotted lines delineate the active area and related sub-regions (core and shell). The red dashed line delimits a Sb-depleted region at the surrounding of the active area. (b) The SAED pattern from the active region (GGST) and including the top electrode (TE) layer is shown. Yellow dashed lines, and red and orange circles locate diffraction spots arising from the three typical crystalline phases found in the GGST layer, i.e., pure Ge, cubic GST, and pure Sb, respectively. The diffraction rings arising from the TE layer are indicated by blue dashed lines. (c–e), “crystallographic maps” of the GGST layer obtained by superimposing one BF and several DF images of (c) Ge, (d) GST, and (e) Sb grains. Grains of different colors originate from different DF-images obtained using different diffraction spots arising from a specific phase. The different sub-regions identified in the Sb-map are also reported on these crystallographic maps. A reference scale bar is reported in (c), which has the same relative size as used for all figures in the manuscript for the comparison purpose.

In summary, crystallographic analysis shows that the chemical segregation observed in the GGST cells after forming does not result in the formation of any off-stoichiometry phases but from the contribution of grains from a few stable and well-known crystalline phases distributed in different proportions depending on their location in the cell: Ge crystals in majority at the surrounding, cubic GST and rhombohedral Sb grains in majority inside the active area with Sb grains preferably near the heater.

Chemical analysis of intermediate and full RESET states

To better understand how the melt-quench RESET pulses induce such changes in the structure and composition of the forming active area, IRSs and full RESET state of I4 forming curve in the 90 nm technology are studied (the corresponding resistances are indicated by the blue big dots in Fig. 1a). Figure 4a,b compares the corresponding STEM images and EELS maps, respectively. The IRS1 state (i.e., Im) has been obtained through the melting and quenching of only the core region of the active area, as evidenced by the DF image and the coloring of the associated EELS map in Fig. 4a,b. As shown by the amorphous contrast visible in the STEM-DF images (Fig. 4a), the size of the amorphous dome progressively increases with the amplitude of the applied RESET pulse, until the full active area is amorphized when using I4, the maximum value of the current used for forming the cells. As highlighted in the RGB-coded EELS maps (Fig. 4b), the amorphous domes detected by STEM-DF are all chemically homogeneous after RESET. Only after programming to the IRS2 state, the region which is chemically homogeneous (see cyan dotted line) is smaller than, while still included inside, the amorphized region observed in the STEM-DF image. In this cell, Ge aggregates are evidenced in the outer part of the dome, as the low current used for programming may have not totally melted the Ge grains remaining in this region after the forming step15,16. This may only be observed “by chance” due to the stochasticity of the crystallization process leading to the forming state. Thus, we believe that “in general”, the active regions corresponding to each of the programmed states all contain an amorphous dome of homogenous composition. The Sb vs Ge scatter plots (Fig. 4c) associated to these amorphous regions all show compact distributions centered on a unique accumulation-point. The position of this center-point, indicating the chemical composition of the amorphous dome, is seen to be modulated by the amplitude of the RESET current.

physical and chemical characterization of GGST intermediate RESET states in 90 nm technology: (a) STEM-DF images where white dotted lines show the extension of the amorphous domes. Scale bars reported in the bottom left of the figure hold the same relative size for all the manuscript for the sake of comparison; (b) EELS maps using a RGB color-code proportional to the [Ge, Sb, Te] % contents (where Ge is reported in red, Te in blue and Sb in green). The amorphous domes are delineated using the same white dotted lines. The cyan dotted line in IRS2 EELS map underlines the extension of the chemically homogeneous area which does not strictly coincide with the amorphous dome; (c) Sb vs Ge scatter plots using a color-code proportional to the distance from the heater (legend reported in the inset). The magenta circles capture the pixels corresponding to the amorphous domes.

Figure 5 shows the variations of the Ge, Sb and Te contents of the amorphous areas shown in Fig. 4. As the current increases, the dome gets larger and becomes much poorer in Sb, richer in Te, and a bit richer in Ge. This can be understood through the effect of the programming current on the active material resulting from forming. After RESET by Im, only the core region of the active area, which is initially very Sb-rich and contains Sb grains (see Figs. 2, 3), is amorphized and thus it maintains its Sb-rich composition when melting. In the meantime, the shell surrounding the core is unaffected by this low current and remains crystalline with a Sb-poor but Te-rich composition (see Fig. 4a,b for IRS1). When the programming current is higher than Im, the melted region extends beyond the Sb-rich region towards the Te-rich region and thus the Sb content inside the amorphous region gradually decreases while the Te content increases. In parallel, the Ge content inside the amorphous dome starts to increase when slightly increasing the current up to IRS2 but then remains constant when programming from IRS2 to the full RESET state.

Ge, Sb and Te contents of the amorphous domes (measured by EELS) characteristic of the different intermediate RESET states. The contents are reported with respect to a reference compositional level (Ge*, Sb*, Te*) to highlight relative variations of intermediate RESET states. The red dotted line indicates the amount of Ge reached by the amorphous dome when using a current amplitude larger than I2. Green and blue arrows indicate the trends observed for the Sb and Te contents, respectively, when increasing the RESET programming current.

These observations confirm the process leading to IRS whereby the pulse melts only a portion of the whole active area and remixes the elements it contains, which results in a homogeneous composition that depends on the portion of core and shell being melted by the pulse. Keeping in mind the composite structure and composition of the active regions of the cell after forming, it is easy to understand why the amorphous domes characteristic of all the IRS have different compositions, tending towards the one of the cells in full RESET state, as the current amplitude increases. From an electrical point of view, amorphous domes of different sizes and compositions are at the origin of the different IRS resistance values. This confirms the peculiar feature of GGST PCM which, in contrast to classical GST-225 based PCM, undergo not only a phase change but also a compositional transition during programming.

The amorphous composition of the cell in full RESET state, obtained using a “melt-quench” pulse with a peak current equal to that used for forming (i.e., I4), results from the melting and remixing of all the elements found in the different sub-regions in the active area of the cell after forming. The entire active area turns into an amorphous dome having a homogeneous and well-defined composition, still enriched in Ge. This full RESET programming process, capable of reverting chemical segregated sub-regions made of crystalline grains of different phases into one single region of amorphous material of homogenous composition, is transversal to the different forming currents, as shown in Fig. 6.

electrical and physical characterization of GGST cells in full RESET states in 90 nm technology: (a) STEM-DF images where white dotted lines delineate the extension of the amorphous dome. Scale bars reported in the bottom left of the figure hold the same relative size for all the manuscript for the sake of comparison; (b) EELS maps using a RGB color-code proportional to the [Ge, Sb, Te] % contents (where Ge is reported in red, Te in blue and Sb in green). White dotted lines delineate the extension of the amorphous dome; (c) Sb vs Ge scatter plots are reported using a color-code proportional to the distance from the heater (legend reported in the inset). The magenta circles capture the pixels corresponding to the amorphous domes; (d) Ge, Sb and Te contents of the amorphous domes (measured by EELS) characteristic of the different full RESET states. The contents are reported with respect to a reference compositional level (Ge*, Sb*, Te*) to highlight relative variations of full RESET states.

Figure 6 reports physical and chemical analysis of three different full RESET states in 90 nm technology obtained using three different forming currents (i.e., by modulating IRESET = Iforming). In particular, we select cells showing the highest resistance values on the I3, I4 and I5 curves of Fig. 1a. Figure 6a shows the dimension of the amorphous domes resulting from such programming, as imaged by STEM-DF. Again, we evidence that the higher the RESET current, the larger the amorphous dome. This is consistent with previous observation that when the peak current increases, the size of the Ge depleted active area increases after the forming pulse15. Figure 6b shows the RGB-coded EELS maps of the domes. The amorphous domes are chemically homogeneous, as previously observed. As reported in Fig. 6c, the Sb vs Ge scatter plots look quite identical and they show the usual compact and well-centered distribution, regardless of the forming current. This can also be observed in Fig. 6d, where the relative values of Ge, Sb and Te contents of the amorphous domes in the different full RESET states are reported and show no significant variations, well below those observed in Fig. 5. All these results show that increasing in parallel both the amplitude of the forming and of the RESET pulses leads to the formation of active regions of increasing sizes but having the same overall chemical composition, which results from the gathering and mixing of all the elements initially found in the region before melting (i.e., after BEOL).

To conclude, it is worth noting that full RESET 3 (Fig. 6a) shows a similar amorphous dome size to IRS2 (Fig. 4a), even if their resistance values are substantially different (Fig. 1a). Thus, different electrical behavior has to be ascribed not so much to the dimension of the dome as in the classical GST-225, but to the Sb richer composition found in the IRS2 state, highlighting the not-negligible impact of the amorphous composition on the electrical characteristics of the GGST-based PCM cells.

Crystallographic analysis of intermediate and full RESET states

In-depth study including crystallographic analysis has been further conducted on GGST cells fabricated in 28 nm technology to understand the influence of the programming current amplitude on the polycrystalline environment of the amorphous dome found after RESET. Results are reported in Figs. 7, 8.

Chemical and physical characterization of a GGST cell programmed in the full RESET state (IRESET = low Iforming) in 28 nm technology: (a–c), EELS (a) Ge, (b) Sb, and (c) Te maps are reported, where white dashed rectangles show different sub-regions of interest. White dotted and red dashed lines delineate the amorphous dome and the Sb-depleted region surrounding the dome, respectively; (d) Sb vs Te scatter plots for the different sub-regions are reported, where the dotted black line indicates compositions with Sb-to-Te ratio of 0.4. The analyzed area of a sub-region is marked and shown with the same name than in the EELS maps; (e), TEM high resolution (HR) images are shown. Yellow dotted lines show the region above the amorphous dome where the set of GST (111) planes are evidenced in the high magnification HR-TEM images. A reference scale bar is reported in (a), which has the same relative size as used for all figures in the manuscript for comparison purpose.

chemical and crystallographic characterization of the GGST cells programmed in the full and intermediate RESET states in 28 nm technology: (a) TEM DF images are shown; (b) EELS maps are reported with RGB color code proportional to the [Ge, Sb, Te] % contents (where Ge is reported in red, Te in blue and Sb in green); (c) the superimposed BF and DF images of Ge crystals are shown; (d), the superimposed BF and DF images of GST crystals are shown. In these images, the white dotted lines delineate the extension of the amorphous dome. In the images of lines (c) and (d) grains of different colors originate from different DF-images obtained using different diffraction spots arising from a specific phase. In images on the right, yellow dotted lines delineate the extension of the active area created after forming for a cell programmed in the intermediate RESET state using IRESET < Iforming. Reference scale bars are reported in (a), which have the same relative size as used for all figures in the manuscript for the comparison purpose.

Figure 7 shows a combined analysis of a 28 nm cell programmed to the full RESET state after a forming pulse below the reference current. From HR imaging (Fig. 7e), a small amorphous dome is found to form close to the heater and surrounded by GST and Ge grains (detailed analyses shown in Fig. 8). While all these GST grains show lattice parameters matching the cubic GST structure, the exact stoichiometry of a grain cannot be assessed solely from its crystallographic feature. Indeed, all the compositionally different GST phases which can be found along the congruent line of the Ge-Sb-Te ternary diagram (between GeTe and Sb2Te3) have the same cubic skeleton and very close lattice parameters11,12. For this reason, we need to complement the structural information by compositional data obtained on the very same region of the cell. The EELS maps (Fig. 7a–c) show four regions with distinct compositions: (1) inside the amorphous dome, (2) in the Sb-depleted region (delineated in red in the EELS-Sb map) above the dome, and (3) and (4) within two areas outside of the Sb-depleted region, labelled “pristine 1” and “pristine 2” as they have not been affected by the forming pulse and only result from BEOL.

As shown by the scatter plot of Sb vs Te (Fig. 7d), the dome region shows, as already noticed, a compact distribution while the pixels associated to the crystalline regions are scattered due to the overlapping of different crystalline phases. The pixels corresponding to the Sb-depleted region accumulate well below the line corresponding to a Sb/Te ratio of 0.4, the signature of the GST-225 phase. However, the corresponding HR-TEM images (Fig. 7e) show the grains have a cubic GST-like skeleton. Thus, we infer that the grains which are formed close to the crystalline-to-amorphous interface and above the amorphous dome are made of GeTe or of very Sb poor GST phases. The pixels associated to the “pristine 1” region are located along the Sb/Te = 0.4 line, evidencing the overlapping of GST-225 and Ge grains in this region. In the region labeled “pristine 2”, lamellar grains are observed associated to very high Sb concentrations, pushing the pixels along a line of large Sb/Te ratio. These results confirm that, after forming using a low current, some pristine GGST material remains around the chemically modified regions of the cell (i.e., Sb-depleted region and active area). Indeed, the pure Ge, GST-225 and Sb lamellar grains which are found randomly mixed are characteristic of GGST alloy after thermal crystallization and BEOL10,11,12,16,17,18. These pristine regions can also be found between the top electrode and the active area and thus may contribute to the electrical properties of the GGST cells29.

Figure 8 compares the chemical and crystallographic characteristics of the GGST cells programmed in the full and intermediate RESET states in 28 nm technology.

Left column of Figure 8 shows the analysis of the full RESET state after a forming pulse below the reference current. By DF imaging (Fig. 8a), a small amorphous dome is found to form close to the heater, which has an irregular shape. Chemical analysis by EELS (Fig. 8b) shows the dome is chemically inhomogeneous, due to the overlapping of materials of different phases, amorphous or crystalline. In such a cell, Ge crystals (see Fig. 8c) are randomly distributed outside the amorphous dome, some well above the dome and a few at the crystalline-to-amorphous interface. Many cubic GST crystals (see Fig. 8d) are found surrounding the amorphous dome. As analyzed in Fig. 7, these GST crystals have different stoichiometries, either Sb-poor or having a GST-225 composition, depending on their distances to the heater.

Middle column of Figure 8 shows the analysis of a cell programmed to the full RESET state using the reference forming current, i.e., a larger forming and RESET current amplitude than discussed above. As expected and shown by the DF image, the amorphous dome is larger than found for the full RESET state with low Iforming, and the Sb-depleted region surrounding the dome has extended and now reaches the top electrode (see the EELS map in Fig. 8b). In this crystalline surrounding, Ge grains (see Fig. 8c) have mainly accumulated at two sides of the dome while GeTe (or Sb-poor GST) crystals (see Fig. 8d) are found above the dome and in contact to the top electrode.

Finally, the right column of Fig. 8 shows a cell in the intermediate RESET state and programmed with IRESET < Iforming = reference forming current.. As also observed in 90 nm technology cells, this programming results in the formation of a smaller amorphous dome, but which contains a higher concentration of Sb than when programmed to the full RESET state (see the EELS map in Fig. 8b). The part of the active area which has not been amorphized by the RESET pulse consists of Ge (see Fig. 8c) and GST (see Fig. 8d) grains mixed together. As expected, the Sb-depleted surrounding of the active area remains unaffected by the electrical pulse, showing the same features than observed after programming to the full-RESET state: Ge grains at the two sides and GeTe (or Sb-poor GST) grains above the dome.

In summary, regardless of the technology nodes, the sizes of the active area and of its chemically modified polycrystalline surrounding both increase when the forming current increases. This is at the origin of the shift of the R-I curves evidenced when increasing the amplitude of the forming current (see Fig. 1a). After forming, the region surrounding the active area systematically shows a Sb-poor composition, regardless of the amplitude of the current used for forming. When increasing the forming current, the materials from the pristine state, which are left over between the active area and the top electrode when using a low forming current, can be progressively melted. In the meantime, the size of the active area has a more direct impact on the cells’ electrical properties. The active area which was melted by the first part of the forming pulse defines the total number of Ge, Sb, and Te atoms that is available to redistribute during the crystallization step taking place during the trailing edge of the forming pulse. After the RESET pulse, the size and the composition of the amorphous dome are interrelated. Indeed, when programming a cell to a RESET state just after forming, the size of the amorphous dome mostly depends on the RESET current amplitude while its composition also depends on the core–shell structure that was generated by the forming pulse. The final (intermediate) RESET resistance of the cell is thus determined by both the RESET and the forming currents.

Discussion

We have carried out full electrical, chemical, and crystallographic characterization of GGST-based PCM cells after forming and RESET programming to a few selected (intermediate) resistance states to reveal the microscopic origin of the electrical properties of such cells. We have shown that, in contrast to classical GST-225 based PCM cells, in GGST-based PCM, forming and programming not only affect the phase of a dome but also its chemical composition and homogeneity.

Forming of the cells leads to the redistribution and segregation of all the elements initially found in the pristine material to form grains of well-known crystalline phases: cubic GST and rhombohedral Sb are mostly found inside the dome, the latter located close to the heater, and laterally confined by Ge grains. By tuning the RESET current, melted area can be tuned until eventually reaching the size of the region initially impacted by the forming step, modulating the fraction of Ge, Sb, and Te elements into the melt and consequently the amorphous dome composition. When programming a full RESET state, a Ge-rich amorphous dome of homogeneous composition is formed by mixing all the elements present in the formed region. These characteristics explain the high conductivity of the crystalline state together with the high temperature RESET retention capability of these cells.

Methods

In this work, the GGST PCM cells were characterized using several (S)TEM based techniques: Dark Field-(S)TEM (DF-(S)TEM) for microstructural investigations and STEM-EELS for chemical analysis. All these analyses were performed on extremely thin (< 25 nm) lamella obtained by means of Focused Ion Beam (FIB) using a ThermoFischer Helios G5UX FIB. This is mandatory to avoid too much overlapping of the grains and mistakenly assigning them “exotic” phases. For that, a new advanced approach has been developed and exploited, notably by decreasing the currents and energies progressively from 30 keV to few keV, in order to avoid material amorphization and damaging. The STEM images were performed with a ThermoFischer Themis Z G3 aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV. To limit the electron beam damage and amorphization of the sample, STEM images and EELS maps were performed using a low beam current (0.5 nA). The EELS maps were acquired with the post column Quantum Gatan Imaging Filter with an energy resolution of 1 eV/channel. The PCM cell chemical maps were obtained using a step size of 8 Å. Conventional TEM imaging (BF and DF) and SAED were performed using an aberration-corrected ThermoFischer TECNAI F20 TEM operating at 200 kV.

Selected vehicle for our experiments is integrated PCM cells in wall architecture30 in 90 and 28nm CMOS technology1,5,6,7. As illustrated in Fig. S3, the active layer is composed of a tiny under-layer (UL) of GST-225, with thickness equal to 10% of the total one, and another layer of X-doped (X corresponding to an element 10–20% concentrated) GGST alloy. In particular, the GGST alloy has been optimized to fulfill automotive requirements, with a crystallization temperature of about 370°C (using a ramp rate of 10°C/min)9.

As the electrical characteristics of GGST PCM are transversal among the different technology nodes, different characterizations have been conducted on PCM devices of 90 and 28 nm technology nodes, depending on the convenience of the analysis to be performed. Since the scope of the present work is to analyze the common physics behind the characteristics of GGST cells, differences between the technology nodes are not under focus. However, the technology nodes of the PCM cells which are analyzed are still specified in the text and the figures.

Electrical measurements were carried out on single cells, i.e., scribe structure without selector. First cells are submitted to a series of RESET-like rectangular voltage-controlled pulses. During the application of such stimuli the current flowing into the device is measured. The magnitude of these pulses is increased until the desired maximum current level is reached. This procedure is called staircase up. Then voltage pulses of decreasing amplitude, starting from the maximum level found, are delivered. During the application of the voltage-controlled pulse the current is sensed, and its value is used to construct the devices I-V curves. Between each pulse a low voltage read stimulus is applied: this is done to extract the resistance value of the state and construct the R-I curves. Such procedure is called staircase down and will lead to a fully crystalline state as accumulation of different rectangular pulses. After this characterization, a forming pulse was applied to all the cells as described in the main text. When needed, RESET pulses of appropriate magnitude were applied to study different amorphous conditions as reported in the main text.

The aforementioned characterization is needed to properly program the scribe structures used in the study and does not impact either electrical or physical proprieties of the device. Deviations from nominal values of electrical characteristics appear after tens thousands of programming cycles6,7; the characterization described is two orders of magnitude below this level.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are confidential. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to elisa.petroni@st.com.

References

Annunziata, R. et al. Phase change memory technology for embedded non volatile memory applications for 90nm and beyond. 2009 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. (IEDM) https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2009.5424413 (2009).

Cappelletti, P. et al. Phase change memory for automotive grade embedded NVM applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 193002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ab71aa (2020).

Redaelli, A. Phase Change Memory (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Pellizzer, F. et al. A 90nm phase change memory technology for stand-alone non-volatile memory applications. 2006 Symp. VLSI Technol. 2006 Digest Techn. Pap. https://doi.org/10.1109/VLSIT.2006.1705247 (2006).

Zuliani, P. et al. Overcoming temperature limitations in phase change memories with optimized GexSbyTez. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 60(12), 4020–4026. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2013.2285403 (2013).

Arnaud, F. et al. Truly innovative 28nm FDSOI technology for automotive micro-controller applications embedding 16MB phase change memory. 2018 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. (IEDM) San Francisco CA https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2018.8614595 (2018).

Arnaud, F. et al. High density embedded PCM cell in 28nm FDSOI technology for automotive micro-controller applications. 2020 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. (IEDM) San Francisco CA U. S. A. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM13553.2020.9371934 (2020).

Cheng, H. Y. et al. A high performance phase change memory with fast switching speed and high temperature retention by engineering the GexSbyTez phase change material. 2011 Int. Electron Devices Meet. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2011.6131481 (2011).

Redaelli, A., Petroni, E. & Annunziata, R. Material and process engineering challenges in Ge-rich GST for embedded PCM. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 137, 106184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2021.106184 (2022).

Rahier, E. et al. Crystallization of Ge-Rich GeSbTe Alloys: The riddle is solved. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 2682–2688. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.2c00038 (2022).

Rahier, E. et al. Multistep crystallization of Ge-Rich GST unveiled by in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and (scanning) transmission electron microscopy. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) Rapid Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.202200450 (2023).

Agati, M., Vallet, M., Joulié, S., Benoit, D. & Claverie, A. Chemical phase segregation during the crystallization of Ge-rich GeSbTe alloys. J. Mater. Chem. C https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TC02302J (2019).

Laurin, L. et al. Unveiling retention physical mechanism of Ge-rich GST ePCM technology. 2023 IEEE Int. Reliab. Phys. Symp. (IRPS) https://doi.org/10.1109/IRPS48203.2023.10118155 (2023).

Baldo, M. et al. Modeling environment for Ge-rich GST phase change memory cells. 2022 IEEE Int. Memory Workshop (IMW) https://doi.org/10.1109/IMW52921.2022.9779290 (2022).

Palumbo, E., Zuliani, P., Borghi, M. & Annunziata, R. Forming operation in Ge-rich GexSbyTez phase change memories. Solid State Electron. 133, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2017.03.016 (2017).

Baldo, M. et al. Modeling of virgin state and forming operation in embedded phase change memory (PCM). 2020 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. (IEDM) https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM13553.2020.9372089 (2020).

Petroni, E. et al. Metrics for Quantification of By-Process Segregation in Ge-Rich GST. Front. Phys. 10, 862954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.862954 (2022).

Petroni, E. et al. Advanced metrics for quantification of by-process segregation beyond ternary systems. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) Rapid Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.202200458 (2023).

Redaelli, A. et al. BEOL process effects on ePCM reliability. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 10, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1109/JEDS.2022.3162755 (2022).

Xu, Q., Lian, E., Yeoh, P. & Skowronski, M. Segregation-induced Ge precipitation in Ge2Sb2Te5 and N-doped Ge2Sb2Te5 line cells. AIP Adv. 12, 6. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0087570 (2022).

Novielli, G., Ghetti, A., Varesi, E., Mauri, A. & Sacco, R. Atomic migration in phase change materials. 2013 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2013.6724683 (2013).

Baldo, M. et al. Modeling environment for Ge-rich GST phase change memory cells. 2022 IEEE Int. Memory Workshop (IMW) Dresden Germany https://doi.org/10.1109/IMW52921.2022.9779290 (2022).

Yeoh, P., Ma, Y., Cullen, D. A., Bain, J. A. & Skowronski, M. Thermal-gradient-driven elemental segregation in Ge2Sb2Te5 phase change memory cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 16. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5095470 (2019).

Rajendran, B. et al. On the dynamic resistance and reliability of phase change memory. 2008 Symp. VLSI Technol. Honolulu HI U. S. A. https://doi.org/10.1109/VLSIT.2008.4588576 (2008).

Novielli, G., Ghetti, A., Varesi, E., Mauri, A. & Sacco, R. Atomic migration in phase change materials. Tech. Digest Int. Electron Devices Meet. IEDM https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2013.6724683 (2013).

Yang, T. Y., Park, I. M., Kim, B. J. & Joo, Y. C. Atomic migration in molten and crystalline Ge2Sb2Te5 under high electric field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 032104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3184584 (2009).

Padilla, A. et al. Voltage polarity effects in Ge2Sb2Te5-based phase change memory devices. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 054501–054501. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3626047 (2011).

Ciocchini, N. et al. Unified reliability modeling of Ge-rich phase change memory for embedded applications. 2013 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2013.6724681 (2013).

Baldo, M. et al. Modeling and analysis of virgin Ge-Rich GST embedded phase change memories. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 70(3), 1055–1060. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2023.3240122 (2023).

Servalli, G. A 45 nm generation phase change memory technology. 2009 IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. (IEDM) Baltimore MD U. S. A. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2009.5424409 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the colleagues of the ePCM Excellence Center and of the AGR FMT Physical Laboratory of STMicroelectronics, Agrate Brianza, for the support and fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R. and E.P. conceived and conducted the experiment, analyzed the results, and wrote the original draft. L.L. and M.B. conceived the experiment and wrote the original draft. A.S. and M.-A.L. and A.M. conducted the experiment. A.R. conceived and led the experiment. A.C. conceived and led the experiment and wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ran, S., Petroni, E., Laurin, L. et al. Phase transitions and chemical segregation in Ge-rich GST based phase change memory cells. Sci Rep 15, 11357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95227-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95227-z