Abstract

Agriculture is an essential foundation that supports numerous economies, and the longevity of the coffee business is of paramount significance. Controlling and safeguarding coffee farms from harmful pests, including the Coffee Berry Borer, Mealybugs, Scales, and Leaf Miners, which may drastically affect crop productivity and quality. Standard methods for detecting pest diseases sometimes need specialized knowledge or thorough analysis, leading to a substantial commitment of time and effort. To address this challenge, researchers have explored the use of computer vision and deep learning techniques for the automated detection of plant pest diseases. This paper presents a novel strategy for the early detection of coffee crop killers using Hybrid Vision Graph Neural Networks (HV-GNN) in coffee plantations. The model was trained and validated using a curated dataset of 2850 labelled coffee plant images, which included diverse insect infestations. The HV-GNN design allows the model to recognize individual pests within images and capture the complex relationships between them, potentially leading to improved detection accuracy. HV-GNN proficiently detect pests by analyzing their visual characteristics and elucidating the interconnections among pests in images. Experimental findings indicate that HV-GNN attain a detection accuracy of 93.6625%, exceeding that of leading models. The increased accuracy underscores the feasibility of practical implementation, enabling proactive pest control to protect coffee farms and improve agricultural output.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coffee is a major agricultural commodity, and its production is vigorous in numerous countries. Coffee plantations are defenseless to various diseases that can significantly reduce coffee yield, such as coffee berry border (CBB) – beetle (Hypothenemus hampei) which is the most destructive coffee pest globally. Research was carried out in Mercara Gold Estate, situated near Coorg, Karnataka, India. Following the background information provided by farmers in coffee cultivation. Farmers are requested to complete research questionnaires addressing the primary issues encountered in pest and disease management, methods of pest infestation detection, the most prevalent pests impacting coffee plants, and soliciting open input. Adult beetles burrow into coffee cherries and lay eggs1. The larvae feed on the developing beans, ruining them for harvest. Signs of infestation include round entry holes in cherries and brownish sunken areas on the fruit. Mealybugs – are soft-bodied insects that suck sap from coffee leaves and stems. They excrete a sticky substance that can attract sooty mould and weaken the plant. Heavy infestations can cause leaves to yellow, drop prematurely, and stunt plant growth. Scales—immobile insects with hard protective coverings that attach themselves to coffee stems and branches2. Like mealybugs, they feed on sap and weaken the plant. Scales also secrete honeydew that promotes sooty mould growth. Leaf Miners—small moth larvae that tunnel inside coffee leaves, creating winding white trails. Depending on the species, they may feed on the upper or lower surfaces of the leaf. Heavy infestations can cause significant leaf loss and reduce the plant’s ability to photosynthesize. The impact of the disease such as reduced coffee bean quantity by causing significant drops in the number of cherries produced, directly impacting yield, lower quality beans to plants often produce smaller or malformed beans, reducing their commercial value, and increasing production costs to farmers by investing in fungicides, insecticides, or other control measures to manage diseases, adding to production costs3. Disease Management, like Fungicides and Insecticides, can be effective, but overuse can lead to resistance to pathogens and harm the environment. Resistant Coffee Varieties with genetic resistance to specific diseases are a more sustainable approach4. Cultural Practices such as pruning for good air circulation, removing fallen plant material, and maintaining good soil health can help reduce disease pressure. Biological Control is the natural enemy of pests and diseases and can be an eco-friendly control method. Vision GNNs, or vision graph neural networks, are a new approach to disease prediction that combines the strengths of computer vision and graph neural networks (GNNs)5. Traditional Disease Prediction with Electronic Health Records (EHRs) Disease prediction has relied on analyzing Electronic Health Records (EHRs) containing patient data like diagnoses, medications, and lab test results6. Machine learning models can be trained on this data to identify patterns and predict a patient’s risk of developing a specific disease. In the proposed work, Vision GNNs introduce visual information into the disease prediction process. This visual information can come from various sources such as medical images: X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, and retinal scans can provide valuable insights into potential diseases. Bio-molecular images: Images of proteins, cells, or tissues can reveal underlying abnormalities. Current pest detection methodology Convolutional neural networks are used to extract localized information from images, resulting in diminished performance when pests overlap, cluster, or co-occur in intricate patterns. Deep learning models for pest detection are computationally intensive and need substantial hardware for training and inference. This makes them inappropriate for real-time implementation on resource-limited rural farms. Restricted datasets that exhibit a deficiency of variety for pest species, environmental variables, and infestation intensities. This results in models that overfit certain circumstances and do not generalize to real-world conditions, including shifting illumination, occlusions, and pest postures. The novelty of the proposed model, Hybrid Vision Graph Neural Network (HV-GNN), uniquely integrates convolutional feature extraction with graph-based relational modeling for pest identification in coffee plantations. The HV-GNN framework utilizes graph neural networks (GNNs) to represent the spatial and semantic connections among bugs in an image. The novel concept is in the graph creation methodology, whereby identified areas of interest (ROIs) indicative of pests are designated as nodes, and edges express geographical, contextual, or co-occurrence associations. This allows the model to recognize individual pest characteristics and deduce their interrelations, including infestation clusters or patterns suggestive of certain pest behaviors. Section “Related work” indicates the literature works illustrated in disease prediction.

Related work

Bibliometric analysis of coffee classification, specifically concerning pest management associated with Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei), Mealybugs (Pseudococcidae), Scales (Coccoidea), and Leaf Miners (Leucoptera coffeella), is conducted for the period from 2011 to 2023 utilizing Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PubMed to compile publication data on biological aspects Fig. 1. Survey and review of current research and publications on a specific topic as part of an academic research project. The survey aims to review and review existing research on the selected topic, with a focus on key ideas, theories, methods, and results as outlined in Table 1. Khodijah, S et al. investigate the effectiveness of plant-derived pesticides against the coffee berry borer (CBB). By analyzing data from multiple studies, the researchers found that botanical pesticides have a positive effect on CBB mortality rates. The study also suggests that botanical insecticides derived from the Anacardiaceous plant family may be particularly successful in controlling this pest7. Gongora, C. E et al., explore methods for managing coffee pests without harming the environment. It emphasizes understanding the coffee plant’s biology, the pest’s lifecycle, and their connection to weather and surrounding habitats. This knowledge is then used to develop control strategies like attracting and trapping pests, utilizing natural predators, and optimizing harvesting practices. This approach, known as Integrated Pest Management (IPM), aims for long-term sustainability and reduced reliance on chemical insecticides8.

Valencia-Mosquera, J. F et al., introduce a unique dataset on coffee pests. It compiles information gathered from Cauca coffee farmers in Colombia, specifically their traditional knowledge about these threats. The dataset spans a year, capturing weekly observations on weather, farming activities, and the presence of various pests. This information, not typically captured by sensors, offers valuable insights for developing strategies to protect coffee crops. The researchers believe this is the first dataset of its kind to leverage ancestral knowledge for pest detection in coffee9. Maheswari, K. S et al., argue that environmentally friendly technologies are crucial for controlling the spread of harmful pests. These technologies, like microbial bio pesticides and pheromones, can target specific pests without harming surrounding ecosystems. The article also highlights the importance of using technology for surveillance and monitoring, particularly with remote sensing tools like satellite imagery Table 2. This allows for early detection and quicker response to outbreaks, especially along borders where transboundary pests can easily travel10. Khodijah, S et al., investigates the effectiveness of plant-derived pesticides against the coffee berry borer (CBB), a destructive beetle pest. The study analyzes data from multiple studies to determine the overall impact of botanical insecticides on CBB mortality. Their findings suggest that botanical pesticides do have a significant positive effect on controlling CBB populations, with extracts from the Anacardiaceous plant family showing particular promise7. Section “Material and methods” illustrates the methods, and datasets used in the proposed model.

Material and methods

The principal objective of this research study is to predict the coffee plantation pest disease using Vision GNN. The contemporaneous techniques for predicting coffee plant disease based on existing and past guidelines have imprecise outcomes. The suggested approach has successfully addressed all of the aforementioned limitations and obtained a predictable outcome in predicting the exact disease affected and providing recommendations for coffee-cultivating farmers.

Data preprocessing and augmentation

The use of data preprocessing and augmentation techniques is of utmost importance in the training of a proficient HV-GNN model for the timely identification of coffee crop killers20. Image size for forming graph structure ranges from 224 × 224. Image quality with minimal compression artifacts is preferred. Image resizing in coffee plant fatigued images could vary. For optimal processing, the model needs equal picture sizes. Scaling and cropping guarantee all photos match the model’s input dimensions. Image data normalization typically changes pixel values due to illumination. Normalization methods like removing the mean or scaling pixel values to a range (0–1) concentrate the model on significant picture content fluctuations rather than absolute intensity levels. Camera sensors and dust particles may cause noise in images Eq. 1 where (i,j) represents pixel coordinates within the filter kernel.

Filtering may enhance model data quality and minimize noise. Rotation & Flipping images may be rotated or flipped horizontally/vertically to simulate coffee plant views from various angles. This strengthens the model against picture orientation changes. Color Jitter Eq. 2 significantly adjusting color balance (brightness, contrast, saturation) may generate a“virtual” that mimics natural lighting conditions. Color jittering involves randomly adjusting image properties like brightness (δB), contrast (δC), saturation (δS), and hue (δH) within a predefined range.

The model can better generalize to new data. Random cropping from original photos lets the algorithm learn by examining various plant portions, perhaps improving localized damage detection.

Feature extraction using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have significant efficacy in the domain of picture feature extraction. The input image is subjected to learnable filters, sometimes known as kernels, using convolutional layers. The filters traverse the picture, examining individual parts sequentially. Every filter inside the picture is designed to identify distinct patterns or characteristics, such as edges, lines, forms, or textures. A convolutional layer generates a feature map as its output.

where, i, j: Indicate the position within the feature map (output of the convolutional layer), k, l: Indicate the position within the filter (kernel) of the convolutional layer Eq. 3, W (k, l): Represents the weight value at position (k, l) in the filter, input (i + k, j + l): Represents the pixel value at position (i + k, j + l) in the input image, b: Represents the bias term for the specific filter, and Σ: Represents summation over all elements within the filter. This phenomenon signifies the existence of the characteristics identified by the filters over the whole of the picture. Various filters are used inside each layer, resulting in the generation of various feature maps, each of which emphasizes certain facets of the picture. CNNs often use stacked layers, which consist of many convolutional layers arranged in a vertical stack. As one progresses through the various levels, the level of complexity shown by the traits being acquired increases. Lower layers acquire fundamental characteristics such as borders and textures Eq. 4.

where i: Represents the specific image node (coffee plant) in the GNN, f: Represents a non-linear function that updates the feature based on current features and aggregated features from neighbors. This function can involve learnable parameters., Current Feature (i): Represents the extracted features from the CNN for the i-th image (coffee plant). Σ Aggregated Features (neighbors of i): Represents the combined features from neighboring image nodes after some aggregation function (e.g., averaging, learnable weights). Advanced layers integrate these characteristics to identify intricate patterns and objects. Convolutional layers frequently include pooling layers to reduce dimensionality. N-Max and average pooling summarize local feature map information. This minimizes network parameters and controls overfitting21.

Graph construction

The latest vision transformer transforms images into patches. For example, ViT breaks a 224 × 224 picture into 16 × 16 patches, generating a 196-length sequence as shown in Fig. 2. Grid structure image is separated into a regular grid of pixels, each containing color intensity. A basic and efficient grid layout fails to capture non-neighboring pixel interactions. Some approaches represent images as sequences of smaller patches. These patches are extracted from the image and processed sequentially. In the proposed graph structure, Nodes are the individual pixels, patches extracted from the image, or even entire regions of interest that can be represented as nodes in the graph. Edges are connected (relationships) between nodes are represented by edges. These edges can be based on spatial proximity (neighboring pixels/patches) or other factors like spatial proximity, semantic relationship, and similarity in color or texture.

Graph processing and feature transform with GNN

The Graph Neural Network (GNN) engages in iterative updates of the features of each node through many rounds of message transfer. Message passing during each cycle, a node’s neighbors send it messages that are based on the properties of the nearby node and the weights of the edges that connect them. These messages compile data about the local environment. Edges between nodes show their relationship. GNNs can learn edge weights during training. The model automatically determines which node connections are most informative for disease prediction. Domain knowledge can be utilized to generate edge weights that connect neighboring pixels with a higher weight than distant regions. Every message passing around, a node receives messages from its neighbors. These messages depend on surrounding nodes’ characteristics and edge weights Eq. 4.

Where, f: learnable function that determines how the neighbor’s feature (information) is transformed based on the edge weight. Feature (j): feature vector of the neighboring node (j). Edge Weight (i, j) weight associated with the edge connecting node (i) to its neighbor (j). After receiving messages from all neighbors, node (i) updates its feature vector. This update considers both the original feature and the aggregated information from the messages. Feature Transformation by combining its original CNN-extracted features with the aggregated messages from its neighbors. This allows the GNN to consider the context of a specific region (e.g., a leaf) about its surrounding areas (stems, other leaves). Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) exhibit significant flexibility and can adjust to data with diverse sizes, structures, and relationships, making them particularly appropriate for the heterogeneous and dynamic situations seen in agricultural settings22.

Multi-Layer hybrid network architecture

A multi-layer HV-GNN architecture predicts coffee plant diseases using isotropic and pyramid methods. The network architecture consists of multiple GNN layers, with each layer potentially having a different architecture. An isotropic architecture is used in Early Layers. All network nodes use the same message-passing mechanism to learn broad relationships and local features near them. It allows one to capture typical disease signs like smaller lesions or textural alterations as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Transition Layer is between pyramid and isotropic layers in Eq. 5, where, m_i^{(l)} is the message received by node i in layer l. AGGREGATE is a function that combines the features of neighboring nodes j in the previous layer (l- 1). This can be a summation, mean, or a more complex learnable function. N(i) is the set of neighbors of node i. f_j^{(l- 1)} is the feature vector of node j in layer l- 1.

The pyramid layers use Node Coarsening to group numerous nodes from the previous layer into one. This limits graph resolution but preserves key information. To prepare for pyramid layer processing, the clustered nodes’ characteristics are integrated. The next layers are pyramidal. Lower Pyramid Layers: Measure features from a smaller neighborhood around each node. This allows precise examination within a region, which may reveal subtle illness signals.

Equation 6 where N_k(i) is the set of neighbors of node i within its specific receptive field size k in layer l. This receptive field size can increase as we move up the pyramid. W_k^{(l)} is a learnable weight vector specific to receptive field size k in layer l. This allows the network to prioritize information based on the scale. Higher Pyramid Layers can absorb more context-relevant information due to wider receptive fields. Capturing larger-scale disease trends or leaf health requires this. These layers’ message-carrying functions may be customized to different receptive fields and scale-aware techniques. Based on coffee plant disease prediction needs, isotropic final levels can have one pyramid layer. These layers refine node representations using local and global data23.

Experimental results and discussion

The Proposed methodology has shown greater efficacy in promptly identifying coffee crop pathogens in comparison to conventional techniques. The effectiveness of the HV-GNN model may be due to its capacity to efficiently combine visual and spectral data, capturing both spatial and spectral patterns related to agricultural pest infestations. By using graph neural networks, the model was able to acquire a deep understanding of intricate connections between plants and their environment.

Evaluation setup and datasets

Python 3.6.5 is used to simulate the recommended model on a PC equipped with an i5 - 8600 k processor, a GeForce 1050 Ti 4 GB, 16 GB of RAM, a 250 GB SSD, and a 1 TB hard drive. The parameters are given below: Batch size: 5, epochs: 55, dropout: 0.5, and learning rate: 0.01. The proposed model was built using the Keres Python framework and module, version 2.7. The input image sizes for the tests varied from 32 × 32 by 3 to 256 × 256 by 3. The suggested solution outperformed others at 224 × 224 × 3 image size. The HV-GNN model was evaluated using the True Positive, True Negative, False Positive, and False Negative metrics.

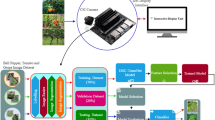

The high-resolution digital camera as shown in Fig. 4 is used to take detailed photographs of coffee plant disease at various stages. A Represents coffee berry border disease, B represents leaf miners, C1, and C2 represents Mealy buds, D1, and D2 represent Scales. 2850 datasets were collected by visiting a coffee plantation located in Mercara Gold Estate, Katakeri, Madikeri Taluk, Karnataka 571,201. The dataset was gathered throughout the blooming and early fruit development phases (March–May) and the berry maturity and ripening phase (October–December). These stages are critical because to their heightened vulnerability to pest infestations, making them optimal for efficiently catching the targeted diseases and pests. Some images are collected from online platforms such as Plant Village and Kaggle. Some are referred to from research articles. Datasets are divided based on 80% training and 20% testing. Consider using magnification to get close-up images of bugs and lesions. Image processing, algorithm execution, and data analysis duties are handled via cloud computing, which provides enough storage space to keep photos, annotations, and analysis results. The image processing software used was Open CV and Fiji. Tensor Flow and PyTorch are used to create and execute custom algorithms for coffee plant disease segmentation. HV-GNN models are pre-trained for disease prediction and fine-tuned using specialized picture datasets. Python is used for statistical analysis, data visualization, and the calculation of assessment metrics like as precision and recall.

Performance evaluation using HV-GNN

The proposed approach incorporates Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to extract features from images and combines them with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to leverage the connections between multiple parts of the image, like as leaves, berries, and stems, to detect pests using evaluation models as shown in Table 3. Accuracy represents the overall proportion of correctly classified samples by the model. It considers both pest detections and healthy plant classifications Eq. 7. Correctly detected pest cases (TP) and healthy plants (TN) are divided by the number of samples analyzed. A high accuracy means the model classifies many correctly.

Precision reflects the proportion of detections that are actual pest cases. In simpler terms, it tells you how many of the identifications made by the model were truly positive Eq. 8.

Precision focuses on the positive predictions (pest detections) made by the model. It tells what proportion of those detections were correct (true positives). A high precision indicates the model is generating a low number of false alarms (FP) where healthy plants are mistakenly identified as having pests as shown in Fig. 5.

Recall indicates the proportion of actual pest cases that were correctly identified by the model. It focuses on how well the model captures all the positive instances (pest-infected plants) Eq. 9. Recall emphasizes the model’s ability to capture all the actual pest cases (positive cases). It tells what proportion of existing pest infections (TP) were correctly identified by the model. High recall is crucial for pest detection as missing infected plants (FN) can lead to delayed treatment and potential crop loss.

The F1 Score is a harmonic mean between precision and recall. It provides a balance between the two metrics, offering a single measure of the model’s performance that considers both correct detections and missed cases Eq. 10. F1 Score addresses the limitations of relying solely on precision or recall. It provides a harmonic mean, balancing the importance of both metrics. A high F1 score indicates the model achieves a good balance between correctly identifying pests and minimizing false alarms.

True Positives (TP) number of pest cases correctly identified by the model. True Negatives (TN) number of healthy plants correctly classified as healthy. False Positives (FP) Several healthy plants are incorrectly identified as having pests (false alarms). False Negatives (FN) number of pest cases missed by the model (missed detections) as shown in (Figs. 6,7,8,9).

Sample images for capturing diseased coffee plant leaves and berry

Comparing HV-GNN with the number of iterations Vs loss and accuracy

An amalgamation of perspectives GNN model integrates a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to extract features from images, and a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn the connections between data points. Iterations imply the frequency at which the training method iterates through the full dataset to modify the internal parameters of the model. The loss metric evaluates the degree of alignment between the model’s predictions and the actual labels (healthy/diseased). Reduced loss indicates superior performance. Accuracy is a measure of the percentage of images that the model properly classifies. Increased accuracy correlates with enhanced illness detection capability as shown in Fig. 10. The experiment entails iteratively training the HV-GNN, first with a small number of iterations and progressively augmenting it. During every iteration, the model’s performance is assessed by utilizing the loss and accuracy metrics. Afterward, these metrics are graphed about the number of iterations, resulting in the creation of two graphs: The graph illustrates the variation in the model’s loss as training advances Optimally, the drop in loss should be consistent as the model acquires knowledge from the data. The graph illustrates the relationship between the accuracy of the model and the number of iterations during training as illustrated in Fig. 11. Optimally, the precision should be enhanced as the model enhances its categorization capabilities.

Comparing with other deep models

The Positive Class indicates the existence of a particular disease, such as coffee scale illness. The Negative Class alludes to the state of not having a disease, such as a coffee plant that is healthy as shown in Fig. 12. A True Positive (TP) model accurately categorizes a sample as having the disease (positive class).

A false positive (FP) model erroneously categorizes a healthy sample as belonging to the disease category (positive class). The True Negative (TN) model accurately categorizes a healthy sample as belonging to the negative class. The False Negative (FN) model erroneously categorizes a diseased sample as being healthy (negative class). True Positive Rate (TPR) = TP/(TP + FN). It indicates the percentage of disease instances the model properly recognizes. High TPR means the model detects true positives (diseases). FP/(FP + TN) = FPR or 1—Specificity. It shows the percentage of healthy samples the model considers as diseased.

A low FPR means the model avoids false positives. FN/(TP + FN) equals FNR or Miss Rate. It indicates the percentage of disease cases the model misses by classifying as healthy. Low FNR means the model detects genuine negatives (healthy samples). TN/(TN + FP) = TNR or Specificity. It shows the percentage of healthy samples the model properly identifies.

A high TNR means the model avoids false positives. Analysis of these rates for each model (CNN, SVM, RF, VGG16, HV-GNN) reveals their strengths and weaknesses. A high TPR and low FNR model should identify most disease occurrences while decreasing false alarms on healthy samples. A model with a high TNR and low FPR classifies healthy samples correctly and prevents false positives. A high TPR model may have a high FPR (more false positives) Fig. 13. The Left Plot 1-sample t-test (Hybrid GNN) presents a histogram of accuracy values for the Hybrid GNN model (Proposed Model). The distribution is centered around a mean of 0.945, shown by the red dashed line. The red dashed line denotes the average accuracy value of the Hybrid GNN model. The data has a narrow distribution around the mean, signifying uniform performance. Histograms of accuracy values for several models are superimposed over the right plot of the 2-sample t-test used to compare hybrid GNN to other models. Comparisons between the Hybrid GNN model (blue), CNN (red), SVM (green), Random Forest (orange), and VGG16 (purple) illustrate the accuracy distribution of the Hybrid GNN model in contrast to other models.

Virtualization

Figure 14, shows four samples in different depths (the 1 st and 12 th blocks) to illustrate how our hybrid ViG model works. The central node is the pentagram, and its neighbors are the same color. Illustrating all edges from two center nodes is messy. Our procedure identifies content-related nodes as first-order neighbors. Color and texture are used for selecting shallow-layer neighbor nodes. The deep layer’s center node neighbors are more semantic and in the same category. ViG network can gradually link nodes by content and semantic representation to improve object recognition.

Discussion

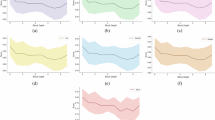

The HV-GNN system combines convolutional processes for feature extraction with graph processing for relational reasoning. This dual processing elevates computational complexity, necessitating significant GPU resources for training and complicating deployment on resource-Limited edge devices. Dependently use a dataset including precisely labeled pests and well-delineated connections among them. Inaccurate or inconsistent annotations in the training data may negatively impact the model’s learning and generalization capabilities. Although the model is trained on a varied dataset, its capacity to generalize to unfamiliar pest species, environmental circumstances, or severe fluctuations (such as illumination, occlusions, or noise) may be constrained. Figure 15, plots ROC-AUC curves for the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) for each class in the classification problem. Classes (0, 1, 2, 3): Each line represents the ROC curve for a specific class such as class 0 (Red): AUC = 0.67, class 1 (Yellow): AUC = 0.91, class 2 (Green): AUC = 0.83, and class 3 (Blue): AUC = 0.81. Micro-average AUC computes metrics globally, considering each element of the confusion matrix as AUC = 0.83. Macro-average AUC averages the metrics across all classes equally. AUC = 0.82. Diagonal Line represents random guessing, where TPR equals FPR.

The confusion matrix highlights the classifier’s performance for true and false predictions for each category. True Label (Rows) represents the real class labels. Predicted Label (Columns) denotes the class labels predicted by the model. Diagonal Components True Positives (accurate forecasts) for each category. Class 0 was accurately predicted 49 times, whereas Class 1 was accurately predicted 73 times. Misclassifications of Off-Diagonal Elements, when one class is erroneously anticipated as another. Class 0 is erroneously categorized as Class 1 on 15 occasions and as Class 2 on 20 occasions. The model has strong performance in Class 1, with 73 accurate predictions and a reduced number of misclassifications. Significant misunderstanding exists between Class 0 and other classes, with 15 instances misclassified as Class 1 and 20 instances as Class 2. Class 3 features 59 accurate predictions, along with some misclassifications into other classes.

Coffee cultivators at Mercara Gold Estate acknowledge the significance of proficient pest and disease control for a successful yield. Nonetheless, we often encounter difficulties in the prompt detection of pests, potentially resulting in considerable agricultural losses. Conventional approaches are labor-intensive and may lack precision. By swiftly detecting concerns, we can conduct focused actions that minimize the effect on our coffee plants and eventually enhance our production. This results in increased revenue and a more sustainable agricultural approach. This novel technique combines the power of visual inspection with advanced algorithms resulting in a more accurate and effective method of monitoring our coffee plants for diseases and pests. This system analyses images of our coffee plants to immediately detect possible problems, such as odd leaf or insect damage. It will help us identify issues early on, enabling us to take appropriate action. This technique has the potential to dramatically enhance our economic well-being by lowering crop losses while raising revenue. It will also help our community’s social and economic growth by supporting environmentally friendly and effective agricultural techniques. It recognizes the significance of ethical considerations in the development and application of AI in agriculture. Our team has confidence that developers will prioritize responsible AI development that serves the interests of both farmers and the environment. Everyone assert that transparent communication among farmers, researchers, and developers is essential for addressing ethical concerns. Collaborative efforts will ensure that this technology is developed and utilized responsibly for the advancement of our community and the environment.

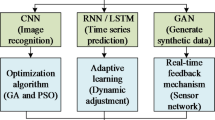

Enhancing HV-GNN: data generalization, computational efficiency, and model transparency

The robustness and utility of Hybrid Vision Graph Neural Networks (HV-GNN) for pest identification in coffee plantations could be markedly enhanced by tackling data generalization, computational efficiency, and model transparency. Enhancing data generalization can possibly be achieved by the integration of domain adaption approaches, the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) for synthetic data augmentation, and the expansion of the dataset to include varied environmental conditions, illumination fluctuations, and multi-spectral picture inputs. Furthermore, self-supervised learning (SSL) methodologies may augment feature extraction from little labeled data, hence improving the model’s flexibility across diverse geographical areas and pest fluctuations. To enhance computational efficiency, graph scarification methods, like Graph Sampling-based Learning (GSL) and Low-rank Matrix Approximation, may be used to minimize duplicate calculations in the GNN layers. Furthermore, model pruning, knowledge distillation, and mixed-precision quantization may substantially reduce inference latency, facilitating real-time implementation on Resource-Limited edge devices. Employing tensor decomposition methods (e.g., CP decomposition or Tucker decomposition) might further decrease memory use while maintaining model precision. Enhancing model transparency can probably be achieved by using Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks, like Graph Attention Mechanisms (GATs) for visualizing node significance and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) for interpreting convolutional neural networks (CNNs). These techniques will improve the interpretability of HV-GNN, cultivating confidence and allowing domain specialists to optimize pest management tactics based on model predictions.

Conclusion

The research being conducted presents a Hybrid Vision Graph Neural Network (HV-GNN) that combines the positive aspects of graph representation and deep learning to tackle the obstacles of insect identification in coffee plantations. The HV-GNN effectively simulates the irregular structures and spatial interconnections observed in plants with diseases by conceptualizing image patches as graph nodes and conveying complicated spatial and semantic links via graph edges. The use of advanced graph blocks alleviates over-smoothing problems often linked to graph convolution, facilitating the extraction of intricate, varied information for precise pest identification. The novel HV-GNN framework outscored conventional approaches, including CNNs, SVMs, Random Forests, and VGG16, across various evaluation parameters, such as F1 score, True Positive Rate (TPR), and False Positive Rate (FPR). The findings highlight its efficacy in identifying unhealthy plants while markedly decreasing false positives for healthy specimens. The model’s exceptional performance highlights its potential as an effective solution for real-time pest monitoring in precision agriculture. HV-GNN’ performance shows that graph-based methods could potentially be used to solve additional agricultural problems including disease progression modelling, ecological monitoring, and yield prediction. Future developments of HV-GNN can specialize in multi-class classification tasks to detect a broader spectrum of hazards, including fungal infections and nutritional shortages, while concurrently modelling interactions among various crop dangers to get a comprehensive knowledge of agricultural health.

Coding availability

Raveena, R. (2024). coffee killer crop coding. Zenodo. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13383093.

Data availability

Raveena, R. (2024). Coffee crop killer. Zenodo. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13382995. Raveena, R. (2024). Coffee Crop Killers. Zenodo. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13382969.

References

Selvanarayanan, R. & Rajendran, S. Roaming the Coffee Plantations Using Grey Wolves Optimisation and the Restricted Boltzmann Machine to Predict Coffee Berry Disease. Int. Conf. Self Sustain. Artificial Intell. Syst. 1(13), 681–689 (2023).

Somasundaram, R., Selvaraj, A., Rajakumar, A. & Rajendran, S. Hyper Spectral Imaging and Optimized Neural Networks for Early Detection of Grapevine Viral Disease. Traitement du Signal 40(5), 156–175 (2023).

Raveena, S. & Surendran, R. Hybridized Rule-Based Recommendation System for Sustainable and Synthetic Fertilizers in Coffee Plantation. Int. Conf. Innov. Intell. Inform. Comput. Technol. 1(12), 242–248 (2023).

Alharbi, M., Rajagopal, S. K., Rajendran, S. & Alshahrani, M. Plant disease classification based on ConvLSTM U-Net with fully connected convolutional layers. Traitement du Signal 40(1), 157–177 (2023).

Selvanarayanan, R., Rajendran, S. & Alotaibi, Y. Early detection of colletotrichum kahawae disease in coffee cherry based on computer vision techniques. CMES-Computer Mod. Eng. Sci. 139(1), 142–166 (2024).

Mohapatra, S. K. et al. Coffee Leaf Diseases Classification Using Deep Learning Approach. In Machine Learn. Algorithms Using Scikit TensorFlow Environ. 1(11), 91–111 (2024).

Khodijah, S., Anggraini, R. T., Andrianto, E., Lestari, P. & Afandi, A. The efficacy of botanical pesticides in controlling coffee berry borer, Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari, 1867) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): A meta-analysis. Jurnal Hama dan Penyakit Tumbuhan Tropika 24(1), 58–65 (2024).

Gongora, C. E., Gil, Z. N., Constantino, L. M. & Benavides, P. Sustainable strategies for the control of pests in coffee crops. Agronomy 13(12), 2940 (2023).

Valencia-Mosquera, J. F. et al. A Qualitative dataset for coffee bio-aggressors detection based on the ancestral knowledge of the cauca coffee farmers in colombia. Data 8(12), 186 (2023).

Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y., Aghabara, A., Davari, M. & Maja, J. M. Feasibility of using computer vision and artificial intelligence techniques in detection of some apple pests and diseases. Appl. Sci. 12(2), 906 (2022).

Whittaker, L. et al. The effect of an altitudinal gradient on the abundance and phenology of the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) (Ferreri) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in the Colombia Andes. Int. J. Pest Manag. 8, 1–12 (2024).

Muccio, K. R., Crone, E. E. & Reed, J. M. A model of coffee berry borer population growth and susceptibility to control by birds. Popul. Ecol. 4, 1–12 (2024).

Wolverton, R. M. & Joseph, S. V. Effects of flupyradifurone application timing and Re-application on the Rhodesgrass mealybug (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) suppression and quality of golf course putting greens. Crop Prot. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2024.106618 (2024).

Ahad, M. T., Emon, Y. R. & Rabbany, G. Multi-format open-source sweet orange leaf dataset for disease detection, classification, and analysis. Data Brief 55, 110713 (2024).

Lu, Y. et al. Predicting the cognitive function status in end-stage renal disease patients at a functional subnetwork scale. Math. Biosci. Eng. 21(3), 3838–3859 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Life table parameters of the tomato leaf miner tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) on five tomato cultivars in China. Insects 15(3), 208 (2024).

Wang, L., Li, Z. W., You, Z. H., Huang, D. S. & Wong, L. GSLCDA: an unsupervised deep graph structure learning method for predicting circRNA-disease association. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 21, 1–18 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. A graph neural network (GNN) method for assigning gas calorific values to natural gas pipeline networks. Energy 278, 127875 (2023).

Bera, A., Bhattacharjee, D. & Krejcar, O. PND-Net: plant nutrition deficiency and disease classification using graph convolutional network. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15537 (2024).

Patel, R. K., Chaudhary, A., Chouhan, S. S. & Pandey, K. K. Mango leaf disease diagnosis using Total variation filter based variational mode decomposition. Comput. Electr. Eng. 120, 109795 (2024).

Kumar, R. et al. Hybrid approach of cotton disease detection for enhanced crop health and yield. IEEE Access. 8, 1–21 (2024).

Aristizábal, L. F. & Johnson, M. A. Monitoring coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) on commercial coffee farms in Hawaii: early insights from the first year of disease incursion. Agronomy 12(5), 1134 (2022).

Chouhan, S. S., Singh, U. P., Sharma, U. & Jain, S. Classification of different plant species using deep learning and machine learning algorithms. Wireless Pers. Commun. 136(4), 2275–2298 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. M and R.S. wrote the main manuscript text and S.R and T.T prepared all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruthai, S., Selvanarayanan, R., Thanarajan, T. et al. Hybrid vision GNNs based early detection and protection against pest diseases in coffee plants. Sci Rep 15, 11778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96523-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96523-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Feature extraction in sensor plant disease datasets using reformed membership functions independent of class variables

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

A novel framework GRCornShot for corn disease detection using few shot learning with prototypical network

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Auto-Encoded Attention Artificial Protozoa Convolutional Neural Networks with Few-Shot Learning for Plant Disease Detection

Cognitive Computation (2025)