Abstract

Apple pomace (AP), a major byproduct of apple juice and cider production, poses significant environmental challenges owing to its high organic load, rapid biodegradability, and disposal difficulties. However, its sustainable valorization can mitigate environmental impacts and contribute to circular economic approaches. This study was designed to address the lack of research on the use of AP as a substrate for CA production by Yarrowia lipolytica in the existing literature. For this purpose, AP was pretreated to increase the concentration of fermentable sugars, and fermentation media containing different concentrations of AP were prepared. Y. lipolytica NRRL Y-1094 was selected to produce CA through submerged fermentation. The process conditions were optimized using response surface methodology (RSM), considering the following factors: concentration of AP (50, 75, and 100 g/L), initial pH level (4.5, 5.5, and 6.5), and fermentation time (4, 6, and 8 days). The optimum conditions were determined to be 100 g/L AP, pH 6.5, and 8 days, resulting in a CA concentration of 38.96 ± 1.65 g/L. Under these conditions, the concentration of isocitric acid (ICA), a by-product of the process, was found to be 10.07 ± 0.07 g/L. Furthermore, a remarkably high biomass of 31.49 ± 1.98 g/L was achieved. These results indicated that AP is a viable alternative to commercial sugar sources for CA production using Y. lipolytica.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Citric acid (CA) is an intermediate formed in the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the metabolism of all aerobic organisms1. CA has the largest tonnage of organic acids produced via fermentation. CA has applications in the food and beverage, pharmaceutical, detergent, metal, chemical, environmental, and biomedical industries2. CA has also been used in nanotechnology and tissue engineering3. The global demand for CA is projected to achieve 3.29 million tons by 2028. Approximately 70% of the global production is utilized in the food industry, 12% in the pharmaceutical industry, and 18% in technical applications4. In the food industry, CA functions as an acidulant, preservative, emulsifying agent, flavoring agent, sequestrant for metal ions, and buffering agent. The increasing world population and the consumption of beverages and processed foods that require additives have led to an increase in the demand for CA. This organic acid is environmentally friendly and cost-effective, owing to its biodegradability. It is Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)6.

Almost 99% of the production is carried out via fermentation, which is safer and more environmentally friendly than the synthetic methods. Surface, submerged, and solid-state fermentations are commonly used techniques for CA production. Submerged fermentation accounts for approximately 80% of the global CA production7. Yarrowia lipolytica, a non-conventional yeast belonging to the Hemiascomycetes family and classified as GRAS, is one of the most promising producers of CA8. A disadvantage of CA production using Y. lipolytica is the formation of isocitric acid (ICA) as a by-product, which reduces the yield of CA and affects its crystallization during purification from fermentation medium9. Nonetheless, the ability of Y. lipolytica to utilize both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substrates, its high tolerance to metal ions and salt solutions, its ability to grow in a wide range of pH (4–8) and temperature (18–32 °C), and its suitability for genetic modification make it highly advantageous for production. The yield of CA depends on the carbon, phosphate, and nitrogen content of the fermentation medium, oxygen concentration, pH, and temperature10. One of the most critical conditions for CA accumulation is the limitation of nitrogen source in the fermentation medium. This is because the production begins with the consumption of available nitrogen. Limiting the concentration of elements, such as sulfur and phosphorus, in the fermentation medium is also effective for CA production by Y. lipolytica11. There is also a need for varying concentrations of thiamine in the fermentation medium depending on the carbon source used for yeast growth. Yeasts grown in glucose-containing media require 3–5 times more thiamine than those grown in n-alkanes12.

The valorization of food processing by-products involves the recovery of fine chemicals or the production of value-added metabolites through chemical and biotechnological processes13. Apple pomace (AP), accounting for about 25–30% of the total processed biomass, is a solid waste generated after grinding and pressing in apple processing facilities14. The selection of AP as a substrate is a good strategy because of its 12.3% fermentable sugar and 85% carbohydrate content. The water-soluble components of AP include mono-oligosaccharides and polysaccharides, whereas its water-insoluble components include pectic substances, hemicellulose, and cellulose15. Although AP is commonly used as cattle feed, only a portion can be utilized because of the rapid spoilage of wet pomace16. This waste is seldom used as compost or feed component. The apple processing industry suffers from the transportation costs required for waste treatment and disposal in landfills to recycle AP; therefore, utilizing these wastes in the production of value-added products, such as CA, has been suggested to be beneficial17. Although the most common disposal method for AP is to discard it to the soil in a landfill, this practice causes severe environmental problems owing to the high-water content (> 70%) and highly biodegradable organic load of AP. The former results in a high vulnerability to microbial decomposition, which can lead to unpredictable fermentation, whereas the latter presents risks to both the environment and public health18.

Studies have shown that yeasts in media containing AP can enable the production of biotechnological products such as lignocellulosic enzymes19, microbial lipids20,21,22, aroma compounds23, biodiesel24, and ethanol25,26. AP is the preferred substrate for CA production by Aspergillus niger strains17,27,28,29,30,31. In addition to the advantages of production with Y. lipolytica, the design and optimization of an alternative biotechnological approach related to AP recycling, which poses an environmental issue, is significant. Moreover, the use of renewable resources such as AP will help increase the environmental sustainability of industrial processes. Although Y. lipolytica has been extensively studied for CA production, the use of AP as a substrate has not been investigated. Therefore, the originality of this study lies in its exploration of AP as a novel substrate for CA production using Y. lipolytica. For this objective, the CA concentration was optimized using response surface methodology (RSM) according to the following factors: concentration of AP (50, 75, and 100 g/L), initial pH (4.5, 5.5, and 6.5), and fermentation time (4, 6, and 8 days).

Materials and methods

Microorganism

Y. lipolytica NRRL Y-1094 was supplied from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The strain was activated in malt extract broth (MEB) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Apple samples

Golden apples (Malus Communis L.) were purchased from local markets in Erzurum, Türkiye. AP was generated under laboratory conditions using a Bosch MES3500 (700 W) centrifugal juice extractor (Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany). The wet AP was dried at 70 °C for 24–48 h and then ground into a powder (Fig. 1).

Pretreatment of AP

Different concentrations of AP (50, 75, and 100 g/L) were pre-treated with 1% H₂SO₄ and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min to enhance fermentable sugar concentration. After autoclaving, the hot liquids were filtered using a vacuum pump, measured, and combined with other components of the medium to prepare fermentation medium.

Determination of reducing sugar concentration

The dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method was used to determine the reducing sugar concentration in the samples after pretreatment and fermentation32.

Fermentation medium

The medium used for CA production contained the following components (in g/L): AP (50, 75 or 100), yeast extract (0.5), KH2PO4 (1), MgSO4·7 H2O (1.5), ZnSO4·7 H2O (0.02), CaCl2 (0.15), MnSO4·7 H2O (0.06), CuSO4 (0.02), FeCl20.6 H2O (0.15), (NH4)2SO4 (1), and thiamine (0.001). Thiamine was added to the autoclaved medium using a 0.22 μm sterile filter prior to inoculations. The pH of the medium was adjusted using 10 N NaOH.

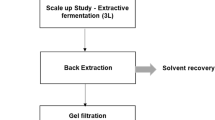

Fermentation conditions

Figure 2 shows a flowchart of CA production from AP. Shake-flask fermentations were carried out using 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL of fermentation medium. The pre-cultures were incubated in MEB on a rotary shaker at 180 rpm and 28 °C for 24 h. The medium was sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min and inoculated with 2% exponential pre-culture. The flasks were incubated at 28 °C and 180 rpm in a rotary shaker for the time specified in the experimental design (JSSI-100, JS Research, Gongju, Korea). To prevent a drop in pH from negatively affecting CA production, the pH levels were adjusted to 4.5–6.5 using 10 N NaOH (for 6 and 8 days of fermentation).

Determination of biomass concentration

After fermentation stage, samples were centrifuged at 13000 x g for 15 min. The remaining cells were washed once with distilled water and dried at 80 °C for 18–24 h. Biomass concentration (g/L) was determined as the dry cell weight per liter of the liquid medium33.

Determination of CA and ICA concentrations

For this purpose, modifications were made to the method proposed by Kamzolova et al.34. The supernatant obtained after centrifugation was filtered through a syringe filter (0.45 μm), and the filtrate was diluted with an equal volume of 8% HClO4. The samples were vortexed for approximately 1 min. The concentrations of CA and ICA in the prepared samples were determined using high performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1100, USA), with calibration curves prepared using external standards. The measurements were performed at 210 nm. The column temperature was 40 °C and the mobile phase flow rate was 1 mL/min. The mobile phase was 0.01 M H2SO4, and an Inertsil ODS-3 (4.6 × 250 mm) column was used for separation.

Process optimization

The effects of the factors on CA production were investigated using response surface methodology (RSM). A central composite design (α = 1) was used to optimize CA production. The levels were − 1, 0, and + 1, with 0 representing the center point (Table 1).

These levels were selected based on the challenges encountered in the preliminary experiments. In the samples pretreated with more than 100 g/L of AP, the vacuum filtration efficiency decreased as the concentration increased, likely due to the higher viscosity of the pectin-rich fibrous materials. On the other hand, AP contains organic acids that buffer the solution. Its high fiber and pectin contents contribute carboxyl groups, which remain negatively charged at slightly acidic to neutral pH levels. This buffering capacity hindered further pH adjustment with NaOH beyond pH 6.5. Despite these constraints, an experimental plan was developed to maximize the feasibility levels.

The significance of the linear, interactive, and quadratic terms was evaluated using an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The overall significance of the regression model was analyzed using the F-test. The adequacy of the predicted model was examined based on the insignificance of the lack of fit error (P > 0.05) and the significance of the regression F-test (P < 0.05). To further assess the model adequacy, the regression coefficient (R2) and adjusted regression coefficient (R² adj) were also considered. Three-dimensional (3D) response surface plots were generated using Minitab Software and were used to identify the optimal conditions as well as the effects of process parameters on CA production.

The process yields were calculated using the following formula:

-

Biomass yield: YX/sugar(consumed) (g/g).

-

CA yield based on sugar: YCA/sugar(consumed) (g/g).

-

CA yield based on biomass: YCA/X (g/g).

-

Volumetric productivity: ProdV:CA/t (g/L h).

-

Specific product formation rate (qCA) = CA/(X.t) (g/ g h).

-

Bioprocess selectivity: SCA (%) = (CA / (CA + ICA)) x100.

Results and discussion

Pretreatment of AP

After the wet pomace was dried and powdered, the samples were treated with 1% H2SO4 and then subjected to heat treatment. The total reducing sugar content of samples containing 50, 75, and 100 g/L AP after pretreatment were determined to be 37.64 ± 0.52 g/L, 54.05 ± 0.34 g/L, and 70.55 ± 0.55 g/L, respectively. In another study, as a result of the same pretreatment, the reducing sugar concentrations obtained from AP were found to be 17.21 ± 2.6, 22.19 ± 0.4, and 38.02 ± 4.8 g/L when the biomass loading was 5, 10, and 15%, respectively35. These results indicate that the initial AP concentration and variety of apples influence the fermentable sugar concentration after pre-treatment, which in turn affects CA production.

Optimization of CA production

The experimental design results are presented in Table 2. The highest concentrations of CA, ICA, and biomass were obtained under the conditions applied during the seventh run. Under these conditions, the fermentation medium contained 100 g/L AP, with an initial pH of 6.5, and a fermentation time of 8 days. Consequently, 38.96 ± 1.65 g/L of CA, 10.07 ± 0.07 g/L of ICA, and 31.49 ± 1.98 g/L of biomass were obtained. The lowest concentrations of CA, ICA, and biomass, measured at 10.34 ± 0.38 g/L, 6.19 ± 0.17 g/L, and 2.46 ± 0.08 g/L respectively, were achieved with a fermentation medium containing 50 g/L of AP, adjusted to an initial pH of 4.5, after 4 days. These outcomes closely correlate with the presence of fermentable sugars in the medium and fermentation time.

On the other hand, reducing sugar measurements were performed on the samples collected at the end of each fermentation time specified in the experimental design, including those subjected to 6 and 8 days of fermentation, and it was determined that all reducing sugars in the fermentation medium were consumed by the producer strain within 4 days (data not shown).

The adequacy of the obtained model and ANOVA results are presented in Table 3. The coefficient of determination (R2), which indicates the goodness of fit between the experimental data and predicted values, was 0.978. This value indicates that 97.8% of the variation in the experimental data can be explained by the response surface model. The F-test for regression was significant (P < 0.05), and the lack of fit was determined to be 49.02 (P > 0.05). As a result, the effects of these factors on CA production by Y. lipolytica NRRL Y-1094 can be well explained by the model.

The estimated regression coefficients for the terms are listed in Table 4. When the table was examined, a positive linear effect was observed for all factors on the response (CA concentration) (P < 0.05). Accordingly, as the levels of these factors increased, CA concentration also increased. The P value is used to assess the statistical significance of each coefficient in the model. A small P value indicates that the corresponding variable has a significant effect on the response.

Fermentation time had the greatest effect on CA production, with the highest linear coefficient (7.666). The fermentation time was followed by the concentration of AP (5.706) and initial pH of the fermentation medium (2.472). However, it is also seen that the initial pH value has a positive, and the concentration of AP and fermentation time have a negative quadratic effect on the response (P < 0.05). Table 4 shows that the quadratic effects of each independent variable used in the model were significant at P < 0.05. The negative quadratic effect states that increasing the levels of the independent variables will increase CA production to a certain level, but production will decrease above a certain level. When the interactions between the independent variables were examined, the interaction between the AP concentration and fermentation time was significant (P < 0.05). No other interactions were found to have a statistically significant effect (P > 0.05).

The quadratic regression equation affecting CA production was determined using Minitab software. The following equation can be used to predict the response at specified levels of each factor, where the levels are provided in their original units:

The optimal conditions for citric acid production were determined to be 100 g/L AP in the fermentation medium, initial pH of 6.5, and fermentation time of 8 days. Under these conditions, the model estimated that a maximum of 38.20 g/L CA could be achieved. A validation experiment was conducted under the optimal conditions, yielding 40.53 g/L CA. This concentration was very close to the predicted value of 38.20 g/L.

Figure 3 illustrates the interaction between the two variables while keeping the third variable constant, as shown in the 3D surface plots. The graphs indicate that CA production was maximized under conditions in which the tested factors had upper limits. CA is produced during the stationary phase of yeast-based production, depending on the growth conditions. Fermentable sugars in all samples were depleted by day 4 (data not shown); however, as illustrated in Fig. 3, fermentation progressed until day 8, at which point the highest CA concentration was achieved.

Process yields

After applying the experimental design and determining the consumption of all reducing sugars at all fermentation times, the various yield values related to CA production were calculated (Table 5). The highest YCA/sugar and YCA/t yields were obtained under the conditions in the seventh row where the maximum CA concentration was achieved. Under these conditions, the CA/ICA ratio, which is particularly important in the purification stage, and the SCA were determined to be 3.87 and 79.46%, respectively.

Hang and Woodams27 reported an 88% yield, calculated based on the sugar consumed by A. niger NRRL 567 in a medium containing AP and 4% (v/v) methanol after 5 days of fermentation. They also determined that yields varied between 77 and 88% via sugar consumption, depending on the apple type28. In another study, using a bioreactor for solid-state fermentation, the process was optimized using the Taguchi statistical method, and 124 g of CA was obtained from 1 kg of dry AP using A. niger BC130. Kumar et al.15 determined that the CA yield was 4.6 g/100 g pomace after 5 days in the presence of 4% (v/v) methanol using A. niger van Tieghem MTCC 281. In another study, rice husks were added to the fermentation medium, including AP, and the production was optimized using RSM for factors such as moisture content, methanol, and ethanol concentration. In the first set of experiments, moisture content and ethanol concentration had a negative linear effect on CA production, whereas in the second design, moisture content and methanol concentration had a positive linear effect. Consequently, the highest CA concentrations obtained with A. niger NRRL 567 were 342.41 g/kg and 248.42 g/kg of dry substrate, respectively17. In a study in which CA production was carried out with ultrafiltration sludge from AP using A. niger NRRL 567, the production was optimized according to the total suspended solids and ethanol/methanol concentrations using RSM. Under optimal conditions, the maximum production was 44.9 g/100 g of dry substrate31.

Tran et al.29 reported that pineapple waste outperformed AP, wheat bran, and rice bran in CA production by Aspergillus foetidus ACM 3996. Sekoai et al.36 found optimal conditions as 33.81 g/L AP, 42.5 g/L corn steep liquor, 2.05% (v/v) methanol, methanol addition at 33 h, pH 4.54, and a temperature of 32.88 °C and a maximum citric acid yield of 68.26 g/L was achieved. Apart from these studies, Dienye et al.37 investigated the potential of Chrysophyllum albidum (African star apple) peels as a substrate for CA production. They identified the optimal fermentation conditions as pH 5.5, an incubation period of 8 days, a methanol concentration of 2% (v/v), and the presence of trace elements, such as copper and iron. Although our study did not include corn steep liquor supplementation or methanol addition, it is evident that methanol had a significant influence on CA yield. This suggests that future studies could explore methanol or ethanol co-substrates to enhance CA production in AP-based media.

Our findings suggest that Y. lipolytica, which naturally ensures lower CA concentrations than A. niger, has significant biotechnological potential, particularly when alternative substrates such as AP are considered. Although A. niger studies have yielded higher CA titers, they often rely on strict pH regulation, additional methanol supplementation, and extensive medium modifications, whereas our approach focuses on AP composition with minimal modifications. Similar to our study, Yalcin et al.38 reported the production of 32.09 g/L CA after 194 h using Y. lipolytica 57 domestic strain in a fermentation medium containing white grape must. It was also reported that the concentrations of glucose and fructose in the grape must were measured at 78.30 g/L and 85.16 g/L, respectively, at the start of the experiments. Interestingly, our study demonstrated that similar CA concentrations could be obtained using 100 g/L AP, despite its lower reducing sugar content, highlighting the substrate efficiency of AP for Y. lipolytica.

Wang et al.40 highlighted that evaluating the technical feasibility and economic viability of citric acid production on an industrial scale is challenging, as it is influenced by factors such as feedstock selection, process conditions, and production techniques. They also indicated that the costs of raw material supply, by-product credits, fermenter expenses, wastewater treatment, and electricity were key factors affecting the minimum selling price of CA. Costa et al.39 indicated the integration of apple waste biorefineries with existing fruit processing facilities to reduce transportation costs and logistical challenges, thereby enhancing profitability indicators. Pretreatment techniques are also important from the economic point of production, which involves the use of alkalis, acids, and enzymes, or biological, mechanical, and hydrothermal approaches. However, each of these methods has limitations. On the other hand, in industrial biotechnology, substrate costs account for 40–60% of the total costs. Using inexpensive and abundantly available waste, such as AP, instead of expensive raw materials, such as commercial glucose, significantly reduces the production costs. This drives interest in using low-cost lignocellulosic biomass as feedstock, which is cheaper than first-generation sources and avoids competition with food and feed supplies, making the process more environmentally sustainable40. From this perspective, it is evident that AP, which was selected as a substrate in this study, will make CA production more economical. However, further studies are needed to enhance the effectiveness of the pretreatments applied and improve the process yield.

Conclusion

This study is the first to evaluate CA production by Y. lipolytica using AP, thereby contributing to both the biotechnological valorization of AP and development of a cost-effective, sustainable alternative to traditional fermentation substrates. This study also provides crucial insights into the feasibility of using AP as a renewable raw material, reducing the dependency on refined sugar sources, and promoting circular economy principles in bioprocessing. As a final point, the optimum conditions were determined to be 100 g/L AP, pH 6.5, and 8 days, and a maximum of 38.96 ± 1.65 g/L CA was obtained under these conditions. The results obtained are notable for the production conducted in flasks. Therefore, this study may encourage future research on CA production by yeast using AP-based fermentation medium.

AP-based high-scale bioproduction requires careful consideration of transportation, drying, and pretreatment costs, which could impact overall profitability. These preliminary results suggest that optimizing bioreactor conditions and streamlining pretreatment processes can improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Future research could focus on minimizing pretreatment energy input or exploring enzymatic hydrolysis methods that might reduce both costs and environmental impacts. Finally, process optimization, bioreactor scaling, and techno-economic feasibility should be investigated to further enhance the viability of AP-based media for industrial CA production. Additionally, the high biomass concentration obtained should be considered as a potential resource for single-cell oil or protein production.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Behera, B. C., Mishra, R. & Mohapatra, S. Microbial citric acid: Production, properties, application, and future perspectives. Food Front. 2, 62–76 (2021).

Behera, B. C. Citric acid from Aspergillus niger: A comprehensive overview. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 46, 727–749 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. Pellet-dispersion strategy to simplify the seed cultivation of Aspergillus niger and optimize citric acid production. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 40, 45–53 (2017).

Kamzolova, S. V. A review on citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica yeast: Past and present challenges and developments. Processes 1, 3435 (2023).

Dudeja, I., Mankoo, R. K., Singh, A. & Kaur, J. Citric acid: An ecofriendly cross-linker for the production of functional biopolymeric materials. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 36, 101307 (2023).

Mores, S. et al. Citric acid bioproduction and downstream processing: Status, opportunities, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 320, 124426 (2021).

Wang, J., Cui, Z., Li, Y., Cao, L. & Lu, Z. Techno-economic analysis and environmental impact assessment of citric acid production through different recovery methods. J. Clean. Prod. 249, 119315 (2020).

Cavallo, E., Nobile, M., Cerrutti, P. & Foresti, M. L. Exploring the production of citric acid with Yarrowia lipolytica using corn wet milling products as alternative low-cost fermentation media. Biochem. Eng. J. 155, 107463 (2020).

Żywicka, A. et al. Significant enhancement of citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica immobilized in bacterial cellulose-based carrier. J. Biotech. 321, 13–22 (2020).

Carsanba, E., Papanikolaou, S., Fickers, P. & Erten, H. Screening various Yarrowia lipolytica strains for citric acid production. Yeast 36, 319–327 (2019).

Cavallo, E., Charreau, H., Cerrutti, P. & Foresti, M. L. Yarrowia lipolytica: A model yeast for citric acid production. FEMS Yeast Res. 17, fox084 (2017).

Finogenova, T. V., Morgunov, I. G., Kamzolova, S. V. & Chernyavskaya, O. G. Organic acid production by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica: A review of prospects. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 41, 418–425 (2005).

Diamantopoulou, P., Sarris, D., Tchakouteu, S. S., Xenopoulos, E. & Papanikolaou, S. Growth response of non-conventional yeasts on sugar-rich media: Part 1: High production of lipid by Lipomyces starkeyi and citric acid by Yarrowia lipolytica. Microorganisms 11, 1863 (2023).

Hijosa-Valsero, M., Paniagua-García, A. I. & Díez-Antolínez, R. Biobutanol production from apple pomace: The importance of pretreatment methods on the fermentability of lignocellulosic agro-food wastes. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 101, 8041–8052 (2017).

Kumar, D., Verma, R. & Bhalla, T. C. Citric acid production by Aspergillus niger van. Tieghem MTCC 281 using waste apple pomace as a substrate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 47, 458–460 (2010).

Shalini, R. & Gupta, D. K. Utilization of pomace from apple processing industries: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 47, 365–371 (2010).

Dhillon, G. S., Brar, S. K., Verma, M. & Tyagi, R. D. Enhanced solid-state citric acid bio-production using apple pomace waste through surface response methodology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 1045–1055 (2011).

Lyu, F. et al. Apple pomace as a functional and healthy ingredient in food products: A review. Processes 8, 319 (2020).

Villas-Bôas, S. G., Esposito, E. & de Mendonça, M. M. Novel lignocellulolytic ability of Candida utilis during solid-substrate cultivation on apple pomace. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 541–545 (2002).

Liu, L., You, Y., Deng, H., Guo, Y. & Meng, Y. Promoting hydrolysis of apple pomace by pectinase and cellulase to produce microbial oils using engineered Yarrowia lipolytica. Biomass Bioenergy. 126, 62–69 (2019).

Herrero, O. M. & Alvarez, H. M. Fruit residues as substrates for single-cell oil production by Rhodococcus species: Physiology and genomics of carbohydrate catabolism. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40, 61 (2024).

Tuhanioglu, A., Hamamci, H., Alpas, H. & Cekmecelioglu, D. Valorization of apple pomace via single cell oil production using oleaginous yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides. Waste Biomass Valor. 14, 765–779 (2023).

Madrera, R. R., Bedriñana, R. P. & Valles, B. S. Production and characterization of aroma compounds from apple pomace by solid-state fermentation with selected yeasts. LWT 64, 1342–1353 (2015).

Karatay, S. E., Demiray, E. & Dönmez, G. Usage potential of apple and carrot pomaces as raw materials for newly isolated yeast lipid-based biodiesel production. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 12, 4773–4783 (2022).

Ngadi, M. O. & Correia, L. R. Kinetics of solid state ethanol fermentation from apple pomace. J. Food Eng. 17, 97–116 (1992).

Demiray, E., Kut, A., Karatay, S. E. & Dönmez, G. Usage of soluble soy protein on enzymatically hydrolysis of apple pomace for cost-efficient bioethanol production. Fuel Process. Technol. 178, 117–123 (2018).

Hang, Y. D. & Woodams, E. E. Apple pomace: A potential substrate for citric acid production by Aspergillus niger. Biotechnol. Lett. 6, 763–764 (1984).

Hang, Y. D. & Woodams, E. E. Solid state fermentation of apple pomace for citric acid production. MIRCEN J. Appl. Microbiol. 2, 283–287 (1986).

Tran, C. T. & Mitchell, D. A. Pineapple waste—a novel substrate for citric acid production by solid-state fermentation. Biotechnol. Lett. 17, 1107–1110 (1995).

Shojaosadati, S. A. & Babaeipour, V. Citric acid production from apple pomace in multi-layer packed bed solid-state bioreactor. Process. Biochem. 37, 909–914 (2002).

Dhillon, G. S., Brar, S. K., Verma, M. & Tyagi, R. D. Apple pomace ultrafiltration sludge—a novel substrate for fungal bioproduction of citric acid: Optimization studies. Food Chem. 128, 864–871 (2011).

Miller, G. L. Modified DNS method for reducing sugars. Anal. Chem. 31 (3), 426–428 (1959).

Papanikolaou, S., Muniglia, L., Chevalot, I., Aggelis, G. & Marc, I. Yarrowia lipolytica as a potential producer of citric acid from raw glycerol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92 (4), 737–744 (2002).

Kamzolova, S. V. & Morgunov, I. G. Metabolic peculiarities of the citric acid overproduction from glucose in yeasts Yarrowia lipolytica. Bioresour. Technol. 243, 433–440 (2017).

Kut, A., Demiray, E., Ertuğrul Karatay, S. & Dönmez, G. Second generation bioethanol production from hemicellulolytic hydrolyzate of apple pomace by Pichia stipitis. Energy Sources Part. Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 44 (2), 5574–5585 (2022).

Sekoai, P. T., Ayeni, A. O. & Daramola, M. O. Parametric optimization of citric acid production from apple pomace and corn steep liquor by a wild type strain of Aspergillus niger: A response surface methodology approach. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 36, 98–113 (2018).

Dienye, B. N., Ahaotu, I., Agwa, O. K. & Odu, N. N. Citric acid production potential of Aspergillus niger using Chrysophyllum albidum peel. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 9(4), 190–203 (2018).

Yalcin, S. K., Bozdemir, M. T. & Ozbas, Z. Y. Utilization of whey and grape must for citric acid production by two Yarrowia lipolytica strains. Food Biotechnol. 23(3), 266–283 (2009).

Costa, J. M., Ampese, L. C., Ziero, H. D. D., Sganzerla, W. G. & Forster-Carneiro, T. Apple pomace biorefinery: Integrated approaches for the production of bioenergy, biochemicals, and value-added products–An updated review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (5), 108358 (2022).

Rumbold, K. et al. J.V.D. Microbial production host selection for converting second-generation feedstocks into bioproducts. Microb. Cell. Fact. 8, 1–11 (2009).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Supervision, G.K.; project administration, G.K.; conceptualization, G.K., B.S. and M.K.; investigation, G.K., B.S. and B.G.; formal analysis, B.S, B.G. and Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S. and G.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaban, G., Gürakar, B., Sayın, B. et al. Utilization of apple pomace as a novel substrate for citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica. Sci Rep 15, 32890 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99202-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99202-6