Abstract

The proportion of cardiac abnormalities in patients with idiopathic scoliosis(IS) who required surgery is relatively high. However, the specific cause and underlying risk factors remain poorly elucidated. A retrospective study. To investigate the proportion of cardiac abnormalities in patients with IS and identify the related risk factors. Clinical and imaging data from 289 IS patients aged 6–18 years including 225 females and 64 males admitted to our center from January 2015 and March 2023 were analyzed. The records of echocardiography, spinal radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging were reviewed. Calculate the proportion of congenital heart disease and cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with IS, and screen the risk factors by multivariate analysis. Twelve patients (4.15%) had congenital heart disease, with atrial septal defect being the most common type (1.73%). Eighty-eight patients (30.45%) had cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves, with mild tricuspid regurgitation being the most common type (17.65%). There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of congenital heart disease among groups based on gender(P = 0.096), age(6 ~ 10 vs. 11–18, P = 0.200), ethnicity(Han vs. Minority, P = 0.969), BMI grade(Emaciation vs. Normal vs. Overweight/Obesity, P = 0.512), altitude(< 2000 m vs. ≥ 2000 m, P = 0.078), main curvature location(Thoracic vs. Thoracolumbar vs. Lumbar, P = 0.326), severity of scoliosis(Deformed vs. Highly deformed, P = 0.841), main direction(P = 0.102), and chest aspect ratio(< 0.45 vs. ≥ 0.45, P = 0.341). The proportion of cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves was higher in males, patients with thoracolumbar IS, and patients with left-sided scoliosis (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that males and thoracolumbar scoliosis were risk factors for cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with IS (P < 0.05). Linear regression analysis showed that altitude had a weak correlation with IS combined with congenital heart disease (R²=0.018, P < 0.05). Among 289 patients with idiopathic scoliosis who required surgery, 4.15% had congenital heart disease, and 30.45% had cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves. Males and scoliosis in thoracolumbar were risk factors for cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with idiopathic scoliosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scoliosis is a three-dimensional spinal deformity characterized by lateral curvature, often accompanied by horizontal vertebral rotation and sagittal plane abnormalities. Clinically, scoliosis is diagnosed using a standing position X-ray of the entire spine, where a Cobb angle of ≥ 10° is indicative of the condition1. The most prevalent form is idiopathic scoliosis (IS), with an international prevalence among adolescents ranging from 0.47 to 5.2%2,3. IS can result in significant physical deformities, adversely affecting the physical and mental health as well as the quality of life of patients4,5. Recent studies have indicated that IS patients may also exhibit structural and functional cardiac abnormalities. These cardiac abnormalities can exacerbate the pathological burden, complicate treatment, and elevate the lifetime risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in scoliosis patients6,7. Therefore, investigating cardiac abnormalities in IS patients is of paramount importance.

Despite extensive research on the clinical diagnosis and treatment of IS both domestically and internationally, there is currently a lack of systematic evaluation and in-depth analysis regarding the proportion and influencing factors of cardiac abnormalities in IS patients. Studies have shown that the proportion of cardiac abnormalities in IS patients ranges from 17.45 to 66%, without clear specific causes or potential risk factors identified8,9,10,11. There is a correlation between high surgical risk and the magnitude of the curve, fused levels, surgery duration, and cyanosis related to cardiac abnormalities6,12. Therefore, understanding the epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of cardiac abnormalities in IS patients holds significant clinical value for improving early diagnosis, selecting appropriate treatment strategies, and evaluating prognosis.

This study utilizes retrospective data and a comprehensive evaluation of clinical and imaging data to systematically analyze the proportion of cardiac abnormalities in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. The objectives are to identify potential risk factors, provide a theoretical basis, and offer practical guidance for more accurate patient assessments, disease progression predictions, and the formulation of effective treatment plans in clinical practice. The findings will enhance the understanding of the association between idiopathic scoliosis and cardiac abnormalities, support the development of individualized treatment plans, and recommend strategies for monitoring and managing cardiac conditions. Ultimately, this will improve patient treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (PJ-2021-100), and all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from patients and their guardians.

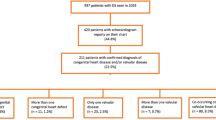

A total of 289 patients with idiopathic scoliosis (IS) aged 6–18 years, including 225 females and 64 males, who required surgery and were admitted to our center from January 2015 to March 2023, were included in this study. The inclusion criterion was patients with IS requiring surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with congenital, neuromuscular, syndromic scoliosis, or other secondary scoliosis; (2) patients younger than 6 years or older than 18 years; (3) patients with incomplete information and data; (4) patients unwilling to participate in the study; (5) patients whose place of origin and long-term residence were inconsistent.

Clinical data reviewed included medical records, echocardiography, plain radiographs, and magnetic resonance imaging of the entire spine. Patients were divided into groups based on gender (male vs. female), age (6–10 vs. 11–18), ethnicity (Han vs. Minority), BMI (Emaciation vs. Normal vs. Overweight/Obesity), chest aspect ratio (< 0.45 vs. ≥0.45), altitude (< 2000 m vs. ≥2000 m; altitude refers to the elevation above sea level of the patients’ long-term residence), main site of scoliosis (Thoracic vs. Thoracolumbar vs. Lumbar), severity (Cobb angle < 90°(Deformed) vs. Cobb angle ≥ 90°(Highly deformed)), and main direction of scoliosis (Left vs. Right).

Cardiac abnormalities included, but were not limited to, various manifestations such as structural abnormalities and heart dysfunction. These were generally categorized into congenital heart disease and cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves. We compared and analyzed the proportion of congenital heart disease and cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with IS and identified risk factors through multivariate analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data following a normal distribution were reported as mean ± standard deviation, while data not following a normal distribution were reported as median and interquartile range. Categorical data were described using counts and percentages. Group differences in quantitative variables were assessed using the independent samples t-test or nonparametric tests. The chi-square test was employed to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as bilateral P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 289 patients, including 225 females (77.8%) and 64 males (22.2%) who required surgery, were included in this study. The median age was 14.0 (13.0–16.0) years, and the median BMI was 17.9 (16.2–19.5) kg/m². Among the patients, 247 (83.7%) were Han Chinese and 47 (16.3%) belonged to ethnic minorities. The primary curve direction was to the left in 85 patients (29.4%) and to the right in 204 patients (70.6%). The median chest aspect ratio was 0.39 (0.33–0.46), and the median main Cobb angle was 50.0° (42.0°–68.0°). Approximately 10.0% of the patients had highly deformed scoliosis (Table 1).

Among the patients, 12 (4.15%) had congenital heart disease, with the most common type being atrial septal defect (ASD, 1.73%), followed by patent foramen ovale (PFO, 0.69%), ventricular septal defect (VSD, 0.35%), and persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC, 0.35%) (Table 2). Additionally, 88 patients (30.45%) exhibited cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves. The most prevalent condition was mild tricuspid regurgitation (TR, 17.65%), followed by mild tricuspid and mitral regurgitation (TR + MR, 10.03%), mild mitral regurgitation (MR, 1.04%), and mild aortic valve regurgitation (AR, 0.69%) (Table 3).

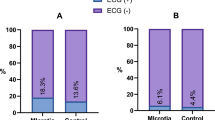

There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of congenital heart disease among groups categorized by gender, age, ethnicity, BMI grade, altitude, main site of scoliosis, severity of scoliosis, main direction, and chest aspect ratio (Tables 4 and 5). The proportion of cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves was higher in males than in females (P = 0.009 < 0.05), higher in patients with thoracolumbar IS than in those with thoracic or lumbar IS (P = 0.027 < 0.05), and higher in patients with left-sided scoliosis than right-sided scoliosis (P = 0.011 < 0.05). No significant differences were observed among other groups based on age (P = 0.199), ethnicity (p = 0.650), BMI grade (P = 0.576), altitude (P = 0.698), severity of scoliosis (P = 0.724), and chest aspect ratio (P = 0.974, Table 6).

The results of the multivariate analysis showed that female was a protective factor against cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with IS (OR = 0.425, 95% CI [0.231, 0.781], P < 0.05). Conversely, scoliosis in the thoracolumbar region was identified as a risk factor for cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in IS patients (OR = 2.972, 95% CI [1.193, 7.406], P < 0.05). The age range of 11–18 years and right-sided IS may be potential protective factors against cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in IS patients, with OR values of 0.424 (95% CI [0.160, 1.123], P = 0.084) and 0.474 (95% CI [0.224, 1.004], P = 0.051), respectively (Table 7). No significant correlation was found between scoliosis severity, cardiac abnormalities, and altitude (P = 0.109–0.419).

The results of the linear regression analysis indicated that altitude had no significant effect on the severity of scoliosis (R²=0.001, P = 0.258) or scoliosis combined with cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves (R²=-0.001, P = 0.429). However, a weak correlation was observed between altitude and scoliosis combined with congenital heart disease (R²=0.018, P < 0.05).

Given the anatomical proximity between the thoracic vertebrae and the heart, we further analyzed the relationship between the direction and severity of thoracic curvature and the occurrence of cardiac abnormalities in 192 patients primarily characterized by thoracic curvature. Among them, 10 patients had congenital heart disease, accounting for 5.21%, and 51 patients had cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves, accounting for 26.56%. The occurrence of congenital heart disease and cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves in patients with predominantly thoracic curvature was not related to the Cobb angle of the thoracic curve (P = 0.535 and 0.094, respectively). There was no significant difference in the proportion of congenital heart disease between groups divided by the direction and severity of thoracic curvature (P = 0.845, 0.806). However, the proportion of cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves was higher in the left curvature group compared to the right curvature group (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the proportion of cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves between the highly deformed (≥ 90°) group and the deformed (< 90°) group (P = 0.806).

Discussion

Idiopathic scoliosis, a multifactorial condition involving epigenetics, paraspinal musculature, intervertebral discs, growth plates, spinal bone structures, and endocrine abnormalities, is distinguishable from other scoliosis types—such as congenital, neuromuscular, syndrome-associated, and those secondary to specific conditions like neurofibromatosis—after their exclusion1,2. Research indicates a higher prevalence of central organ anomalies in patients with idiopathic scoliosis (IS), with the IS-cardiac abnormality link being a focal point of scholarly attention3,9,11,12. Cardiac anomalies can be divided into two broad categories: congenital heart diseases and cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves. Although some studies suggest that congenital heart diseases do not independently exacerbate complications like wound infection or extend hospital stays post-posterior spinal fusion surgery13, other studies have identified evidence for altered cardiac function and an increased lifetime risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in participants with scoliosis. Thus, cardiac abnormalities remain critical to the surgical and anesthetic risk evaluation in IS patients7. To elucidate the relationship between IS and cardiac abnormalities further, this study analyzed the proportion of cardiac abnormalities in 289 IS patients and examined the associated risk factors.

The findings of this study revealed that approximately 4.15% of individuals with Idiopathic Scoliosis (IS) also had various types and severities of congenital heart disease (CHD). This proportion is comparable to that reported by Lang C et al.8, slightly higher than the 3.30% found by Ipp L et al.9, and lower than the rates observed in studies by Liu L et al.10 and Bozcali E et al.11. The predominant form of CHD in this cohort was atrial septal defect (1.73%), consistent with the majority of prior studies8,9,10. In contrast, Bozcali et al.11 reported mitral valve prolapse as the most frequently encountered anomaly. Additionally, approximately 30.45% of IS patients exhibited varying extents of cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves. These figures align with the findings of Ipp L et al.9 and Colimina et al.14, significantly surpassing the prevalence of central organ anomalies in the general healthy population15, but remaining below the percentages reported by Bozcali E et al.11. Mild tricuspid regurgitation was identified as the most prevalent cardiac anomaly, corroborating the results of Zhu et al.16, but contrasting with findings from Dhuper et al.17 and Hirschfeld S et al.18. The increased proportion of cardiac abnormalities in IS patients, compared to the general population, can primarily be attributed to two factors: firstly, the altered chest configuration and volume resulting from scoliosis can mechanically impinge upon cardiac structures; secondly, both the circulatory and skeletal systems originate from the mesoderm during embryonic development. Since the etiology of IS remains elusive—potentially a multifactorial genetic disorder—the associated pathogenic elements might also influence cardiac development.

Given the high proportion of cardiac abnormalities found in patients with idiopathic scoliosis in this study, we believed that routine echocardiography (ECHO) was necessary for a comprehensive evaluation of the cardiac condition in these patients requiring surgery. Firstly, cardiac abnormalities could significantly impact the physical and mental health of patients, potentially even more so than scoliosis itself. Secondly, even patients with normal heart function were at risk of cardiovascular complications during the perioperative period of spine correction surgery. This risk was greatly increased, potentially leading to adverse events, if cardiac abnormalities were present7. For patients with mild scoliosis detected through early screening, further research was needed to determine whether routine ECHO was necessary to evaluate their cardiac condition.

Current literature demonstrates a lack of analysis regarding the factors associated with cardiac abnormalities in individuals with idiopathic scoliosis (IS). Although cardiac function metrics for most IS patients fall within normal ranges, the potential impacts of variables such as gender, age, ethnic background, body mass index (BMI) classification, altitude, primary curvature location and orientation, severity, and thoracic aspect ratio on cardiac structure and function in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) warrant investigation. This study therefore conducted a comprehensive examination of these factors and their influence on the prevalence of cardiac abnormalities in AIS patients. The findings indicate that male IS patients exhibit a higher propensity for cardiac irregularities beyond congenital heart defects, as shown in Table 6. Rocławski M et al. also found that the proportion of scoliosis following patent ductus arteriosus thoracotomy is significantly higher in males than in females19. Nonetheless, some studies conducted by Chinese researchers suggest that gender does not significantly affect the incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies, mitral valve prolapse, or pulmonary hypertension20,21. However, additional research is required to determine if gender influences the prevalence of cardiac abnormalities in patients with scoliosis.

From a spatial perspective, the orientation and degree of primary curvature in scoliosis are critical factors that may contribute to cardiac anomalies in individuals with idiopathic scoliosis (IS). Progressive thoracic curvature often leads to atypical thoracic development, and a significant reduction in thoracic volume can impede cardiac formation. However, our research indicates that patients with thoracolumbar (T11-L1) scoliosis have a higher propensity for cardiac abnormalities related to heart valves, excluding congenital heart defects.

Furthermore, the findings of this study indicate that leftward curvature and the 6–10 year age group may be potential risk factors for idiopathic scoliosis (IS) patients with cardiac anomalies, distinct from congenital heart defects, as evidenced by the near-statistical significance (P = 0.051 and P = 0.084). Liang Jinqian et al.22 also observed disparities in specific cardiac function metrics between patients with left versus right curvature. Regarding the influence of age on the proportion of cardiac abnormalities in IS patients, it is crucial to consider that the growth and development trajectories of the spine and heart vary across different age phases. Generally, the normal structure of the human heart remains stable until the age of 30, with systolic function stabilizing after the age of 10. Before reaching this stage, the heart undergoes continuous development and adjustment. Wang Yang et al.23 further identified age as an independent determinant of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD), left ventricular internal diameter at end-systole (LVIDS), and interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole (IVSTD).

Previous studies have indicated that the severity of scoliosis significantly influences the emergence of cardiac abnormalities. For example, Li et al. observed a decrease in right ventricular function in patients with a primary curvature angle exceeding 80 degrees24. Seokwon and colleagues identified a negative correlation between the mitral valve E/A ratio and the severity of thoracic deformities25. Wang Yang et al. reported a correlation between increased thoracic vertebral coronal plane Cobb angles and both reduced left ventricular diameters and decreased aortic flow velocity23. Liang Jinqian and colleagues found that patients with a coronal Cobb angle greater than 80 degrees exhibited a higher rate of left ventricular short-axis contraction compared to those with angles between 45 and 80 degrees22. Unlike previous studies, this research referenced expert consensus and established a threshold of 90 degrees to define highly deformed scoliosis. The results showed no significant difference in the proportion of cardiac abnormalities between patients with highly deformed and deformed scoliosis.

This study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective design. The cohort was restricted to idiopathic scoliosis (IS) patients requiring surgical intervention who had undergone routine echocardiography (UCG) at our institution. This approach excludes patients in earlier disease stages, potentially introducing selection bias and limiting generalizability to the broader IS population. Additionally, the dataset lacks detailed cardiac structural and functional parameters, preventing a comprehensive evaluation of cardiac abnormalities. Finally, as scoliosis involves three-dimensional spinal deformities, future studies should investigate how vertebral rotation and sagittal plane alignment alterations influence cardiac pathology.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Cheng, J. C. et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15030. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.30 (2015).

Konieczny, M. R., Senyurt, H. & Krauspe, R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 7 (1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-012-0457-4 (2013). Epub 2012 Dec 11. PMID: 24432052; PMCID: PMC3566258.

Sung, S. et al. Incidence and surgery rate of idiopathic scoliosis: A nationwide database study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (15), 8152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158152 (2021). PMID: 34360445; PMCID: PMC8346015.

Weinstein, S. L. The Natural History of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. ;39(Issue 6, Supplement 1 Suppl 1):S44-S46. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/BPO.0000000000001350. PMID: 31169647.

Karol, L. A. The Natural History of Early-onset Scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. ;39(Issue 6, Supplement 1 Suppl 1):S38-S43. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/BPO.0000000000001351. PMID: 31169646.

Cohen, L. L., Przybylski, R., Marshall, A. C., Emans, J. B. & Hedequist, D. J. Surgical Correction of Scoliosis in Children with Severe Congenital Heart Disease and Palliated Single Ventricle Physiology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). ;46(14):E791-E796. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003905. PMID: 33394986.

Quintero Santofimio, V., Clement, A., O’Regan, D. P., Ware, J. S. & McGurk, K. A. Identification of an increased lifetime risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in UK biobank participants with scoliosis. Open. Heart. 10 (1), e002224. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2022-002224 (2023). PMID: 37137668; PMCID: PMC10163590.

Lang, C. et al. Incidence and risk factors of cardiac abnormalities in patients with idiopathic scoliosis[J]. World Neurosurg. 125, e824–e828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.177 (2019).

Ipp, L. et al. The findings of preoperative cardiac screening studies in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis[J]. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 31 (7), 764–766. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPO.0b013e31822f14d6 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Prevalence of cardiac dysfunction and abnormalities in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis requiring surgery[J]. Orthopedics 33 (12). https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20101021-08 (2010).

Bozcali, E. et al. A retrospective study of congenital cardiac abnormality associated with scoliosis. Asian Spine J. 10 (2), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.4184/asj.2016.10.2.226 (2016).

Przybylski, R. et al. Adverse perioperative events in children with complex congenital heart disease undergoing operative scoliosis repair in the contemporary era. Pediatr. Cardiol. 40 (7), 1468–1475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-019-02169-1 (2019). Epub 2019 Jul 26. PMID: 31350568.

McKee, C. T., Martin, D. P., Tumin, D. & Tobias, J. D. Cardiac Risk Factors and Complications After Spinal Fusion for Idiopathic Scoliosis in Children. J Surg Res. ;234:184–189. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.029. Epub 2018 Oct 11. PMID: 30527472.

Colomina, M. J., Puig, L. & Godet C,Villanueva C,Bago, J. Prevalence of asymptomatic cardiac valve anomalies in idiopathic scoliosis.[J]. Pediatric cardiology. 23(4), https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-002-1443-2.PMID:12170360 (2002).

Steinberger, J., Moller, J. H., Berry, J. M. & Sinaiko, A. R. Echocardiographic diagnosis of heart disease in apparently healthy adolescents.[J]. Pediatrics. 105(4 Pt 1), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.4.815.PMID:10742325 (2000).

Zhu, X. D., Wang, J. L. & Li, M. Prevalence of valvular regurgitation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 20 (1), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPB.0b013e3283339990 (2011). PMID: 20921910.

Dhuper, S., Ehlers K H,Fatica, N. S., Myridakis, D. J., Klein A A,Friedman, D. M. & Levine, D. B. Incidence and risk factors for mitral valve prolapse in severe adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.[J]. Pediatric cardiology. 18(6), https://doi.org/10.1007/s002469900220 (1997)

Hirschfeld, S. S., Rudner, C. & Nash C L,Nussbaum E,Brower, E. M. Incidence of mitral valve prolapse in adolescent scoliosis and thoracic hypokyphosis.[J]. Pediatrics. 70(3), 451-4 (1982).

Rocławski, M. et al. Wpływ Torakotomii Bocznej Na Rozwój Skrzywień Bocznych Kregosłupa U Pacjentów Z Przetrwałym Przewodem Botala [The effect of lateral thoracotomy on the development of scoliosis in patients with patent ductus arteriosus]. Chir. Narzadow Ruchu Ortop. Pol. 74 (3), 127–131 (2009). Polish. PMID: 19777942.

Wang Yang, Z. et al. The incidence of cardiac abnormalities in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients [J]. Chin. J. Spinal Cord. 23 (06), 520–524 (2013).

Yang Guanghui, L. et al. Analysis of preoperative echocardiography screening results in patients with idiopathic scoliosis [J]. Western Med. 25 (04), 515–518 (2013).

Liang Jinqian, S. et al. A study on the cardiac structure and function of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients [J]. Chin. J. Orthop. Arthrology. 1(3), 195–201. (2008).

Wang Yang, Z. et al. The impact of thoracic curvature on cardiac structure and function in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients [J]. Chin. J. Spinal Cord. 26 (08), 723–728 (2016).

Li, S. Yang Junlin,Li Yunquan,Zhu Ling,Lin Yuese,Li Xuandi,Huang Zifang,Wang Huishen. Right ventricular function impaired in children and adolescents with severe idiopathic scoliosis.[J]. Scoliosis. 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7161-8-1 (2013).

Huh & Seokwon Eun Lucy Yougmin,Kim Nam Kyun,Jung Jo won,choi Jae Young,Kim Hak sun. Cardiopulmonary function and scoliosis severity in idiopathic scoliosis children.[J]. Korean journal of pediatrics 58(6), https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2015.58.6.218 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the contributions of the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Academician Workstation Project in Yunnan Province, and Yunnan Fundamental Research Kunming Medical University Joint Projects. We also appreciate all doctors and nurses who collected and recorded patient information. And we appreciate all patients and their families who were willing to participate in the study.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82060392), the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Talents and Platform Project (grant numbers202205AF150009), Yunnan Fundamental Research Kunming Medical University Joint Projects (grant numbers 202401AY070001-223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ, XY, ZZ and YW discussed and drew up the research design. LZ and XY was responsible for analyzing data and drafted the draft. ZZ, LZ, XY, YW and JL revised the manuscript. ZZ, YW and JL helped with project coordination. WX, GQ, ZS, TL, QL, NB, ZS and ZqZ helped to collect data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Data access statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Consent for publication

This study has been approved by the medical ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University(PJ-2021-100). And all authors reviewed the manuscript content and approved the final version for submission.

Informed consent

The informed consent was obtained from patients and their guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Zhang, L., Wang, Y. et al. Risk factor analysis for cardiac abnormalities in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Sci Rep 15, 16013 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99366-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99366-1