Abstract

The growing demand for safe and effective natural ingredients in cosmetic formulations has prompted research into marine-derived compounds, particularly phlorotannins from brown algae. These compounds exhibit diverse bioactivities, including tyrosinase inhibition, which is relevant for the treatment of skin hyperpigmentation disorders. This study aimed to optimize the ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) of phlorotannins from the brown macroalga Dictyopteris justii and to evaluate the in vitro tyrosinase inhibitory activity of the resulting extract. A Box–Behnken design was employed to optimize the extraction parameters: ethanol concentration, solid-to-liquid ratio, temperature, and time. Total phlorotannin content (TPhC) was quantified using the DMBA colorimetric method, and the optimized extract was evaluated for tyrosinase inhibitory activity using a commercial colorimetric assay. The IC₅₀ of the extract was determined and compared with kojic acid. The optimal extraction conditions were identified as 70% ethanol, a 1:10 solid-to-liquid ratio, 25 °C, and 20 min. Under these conditions, the TPhC reached 2.874 ± 0.069 mg phloroglucinol equivalents per gram of dry extract, with a 9% extraction yield. Chromatographic analysis suggests the presence of hydroxypentafuhalol-B in the extract.The optimized extract showed significant tyrosinase inhibitory activity with an IC₅₀ of 0.51 mg/mL, compared to 46.61 µg/mL for kojic acid. This study demonstrates the successful optimization of UAE for obtaining a phlorotannin-rich extract from D. justii with reproducible extraction efficiency and potent tyrosinase inhibition. These findings support the potential application of D. justii extracts in the development of cosmetic products targeting hyperpigmentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the use of natural ingredients in the development of cosmetic products, driven by the need to identify safer, more effective, and sustainable alternatives for managing skin disorders such as hyperpigmentation. This condition is characterized by an abnormal increase in melanin production and is conventionally treated with agents like hydroquinone. However, prolonged use of hydroquinone may lead to undesirable side effects, including irritation, exogenous ochronosis, and systemic toxicity, which has stimulated the search for new natural alternatives1.

In this context, marine algae, particularly brown macroalgae, have emerged as a promising source of bioactive compounds. Algae are photosynthetic organisms essential to the balance of aquatic ecosystems and are classified into microalgae and macroalgae, the latter further divided into green, red, and brown algae2,3. Although red algae represent the most diverse group in terms of species, brown algae account for 59% of global cultivated macroalgae production4,5. Their rich composition in polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, vitamins, and minerals gives them nutritional and bioactive properties of great interest for the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries2,6.

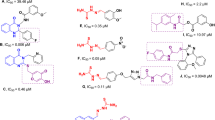

Among the most studied compounds in brown algae are phlorotannins, polymers derived from phloroglucinol units (Fig. 1), which serve as defense mechanisms against herbivores, absorb UV radiation, and protect against adverse environmental conditions7,8,9. These secondary metabolites have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, photoprotective, and depigmenting activities7,10,11. Specially, their capacity to inhibit tyrosinase, the key enzyme in melanogenesis, highlights their potential in the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders12,13,14,15,16.

However, the content and composition of phlorotannins in algae vary widely depending on intrinsic factors (species, age, tissue type) and extrinsic conditions (light, temperature, salinity)17,18,19. Therefore, the standardization of extraction and quantification processes is essential. Techniques such as ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and analytical methods like the DMBA assay have proven to be effective strategies for obtaining and evaluating phlorotannins20,21.

Within this framework, Dictyopteris justii has emerged as a species of particular interest. This brown macroalga, found in tropical regions such as San Andrés and Providencia (Colombia)22,23, has been reported as a source of bioactive metabolites including phlorotannins, flavonoids, terpenes, and fucosterol22,24,25. Recent studies have documented its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, as well as its tyrosinase inhibitory potential, supporting its applicability in cosmetic formulations aimed at hyperpigmentation control24,26,27.

Despite its promising bioactive profile, limited information is available on the standardization of D. justii extracts for cosmetic use. Given that the efficacy of natural extracts depends on both the quantity and quality of their active constituents, optimizing extraction and quantification conditions is critical to ensure their reproducibility and functional performance8,17,28.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop and standardize a phlorotannin-rich extract of Dictyopteris justii through the optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction and to evaluate its in vitro tyrosinase inhibitory activity, with the goal of proposing its potential application in cosmetic formulations designed for the treatment of skin hyperpigmentation.

Adapted from Erpel et al. (2020)8.

Chemical structure of phloroglucinol and representative examples of each phlorotannin group. Phloroglucinol (A), fucols (B), fucophlorethols (C), carmalols (D), fuhalols (E), eckols (F, G), and phlorethols (H).

Materials and methods

Materials

Absolute ethanol (99.5%) – PanReac AppliChem and distilled water were used for extract preparation. For the analysis of total phlorotannin content (TPhC), HPLC-grade methanol – Supelco/Merck, glacial acetic acid – PanReac AppliChem, 2,4-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde (DMBA) – Sigma Aldrich, phloroglucinol – Sigma Aldrich, and hydrochloric acid – Mallinckrodt Chemicals were used. To determine relative tyrosinase inhibition, a colorimetric tyrosinase inhibitor detection kit – Sigma Aldrich was employed.

Dictyopteris Justii material

Marine macroalgae samples of Dictyopteris justii were collected in July 2022 on Providencia Island via scuba diving, in compliance with relevant international regulations governing marine biodiversity research. Sampling activities were conducted under permits issued by the competent Colombia environmental authorities and followed practices to mize environmental impact. The study adhered to the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction; according to the IUCN Red List, Dictyopteris spp. is classified as Data Deficient, and no CITES-regulated species were collected. The samples were collected under permission from the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, No 121 of 22 January 2016 (modification otrosí No 7) for collecting samples.

The material was stored at − 20 °C, rinsed with seawater to remove debris, freeze-dried, ground, and stored in airtight containers at − 20 °C protected from light until use. Sample identification was carried out by a team of marine biologists and biologists based on morphological characteristics. A specimen of D. justii was deposited in the herbarium of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana under accession number HPUJ30852.

Optimization of Phlorotannin content in D. justii extract

To optimization of the extract, a Box-Behnken response surface experimental design (BBD) was proposed. In the design, four factors were evaluated at three levels (Table 1), with total phlorotannin content (TPhC) selected as the response variable.

For the extraction, 1.5 g of algal dry pulverized algae was weighed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube (Falcon type) with a cap. The solvent was added, and the tube was placed in an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic Easy 30 H – Elma) at the temperature and duration specified by the experimental design. The resulting extracts were filtered by gravity, and the solvent was subsequently evaporated to dryness using a vacuum concentrator. The dried extracts were stored at − 20 °C, protected from light, until analysis. Following the analysis of the experimental design, a triplicate extract was prepared under the optimal conditions predicted to yield the highest phlorotannin content, in order to validate the statistical model.

Determination of total Phlorotannin content by colorimetric DMBA method

The quantification of total phlorotannin content (TPhC) was carried out using the DMBA reagent following the methodology proposed by Lopes et al. (2012)19, with slight modifications. A stock solution of each extract was prepared in methanol (MeOH) at a concentration of 20 mg/mL, and subsequently diluted to 15 mg/mL with MeOH. A working solution was freshly prepared by mixing equal volumes of 2% w/v DMBA in glacial acetic acid and 6% v/v HCl in glacial acetic acid. A blank of the working solution without DMBA was also prepared.

In a 96-well plate, 50 µL of each extract was added to individual wells, followed by 250 µL of the working solution. The plate was incubated at 25 °C for 60 min at 30 rpm in darkness. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 515 nm using a microplate reader. For the blanks, the working solution without DMBA was added to each extract. TPhC was calculated using a calibration curve constructed with phloroglucinol. For each extract, the absorbance of the corresponding blank was subtracted. Results are expressed as mg phloroglucinol equivalents (mg PGE) per g of dry extract. All extracts, blanks, and standards were analyzed in triplicate.

UHPLC-UV-MS-QqQ analysis

The crude extract of D. justii was dissolved in methanol LC-MS grade, at a final concentration of was 2000 µg/mL, and filtered through 0.22 μm PTFE membrane filters (Millipore Millex). The analysis was performed on a Nexera LCMS QqQ 8060 Shimadzu chromatograph (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany) equipped with photodiode array detection (PDA) and electrospray ionization (ESI) and triple quadrupole MS detection, pumps, on-line degasser and autosampler. The column employed was a Shimadzu Shim-pack C18 column (150 × 3.0 mm), using a gradient system of water with formic acid at 0.5% (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B), as follow: 20–80% B (0–25 min); 80 − 20% B (25–27 min); 20% B (27–30 min. The flow rate was kept constant at 0.4 mL/min and an injection volume of 5 µL. Detection was performed at 280 nm and 330 nm. MS data was acquired in positive and negative mode in an m/z range from 100 to 1500, using a full scan (Full-MS).

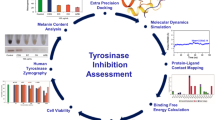

Evaluation of in vitro tyrosinase inhibitory activity

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was assessed using a commercial colorimetric tyrosinase inhibitor screening kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol29. A stock solution of the optimized Dictyopteris justii extract was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in methanol (MeOH) and subsequently diluted to 2 mg/mL using the assay buffer provided in the kit. To evaluate the potential effect of the solvent, a methanol control was prepared using the same dilution scheme in buffer. Kojic acid (14.2–106.6 µg/mL) was employed as a positive control, while the assay buffer alone served as the enzyme activity control. A volume of 20 µL from each sample—extract [S], extract blank [S Bl], solvent control [SC], positive control [IC], and enzyme control [EC]—was dispensed into the wells of a 96-well microplate. Next, 50 µL of the Tyrosinase Enzyme Solution (TES) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min at 30 rpm in the dark. This was followed by the addition of 30 µL of the Tyrosinase Substrate Solution (TSS). The detailed compositions of TES and TSS are presented in Table 2. Absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a microplate reader in kinetic mode over a period of 60 min, with readings taken every 10 min. The reaction rate (slope) for each sample was calculated using two selected time points (Eq. 1). The percentage of relative tyrosinase inhibition (%RI) was then calculated using Eq. 2. To determine the IC₅₀ value, serial dilutions of the optimized extract were prepared in the range of 0.25–2.00 mg/mL using the assay buffer.

Before calculating the slope for each extract, the absorbance of the corresponding blank was subtracted. The final result for each extract is reported as the relative inhibition percentage (%RI), after subtracting the %RI of the solvent. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Where Abs is Absorbance, [EC] corresponds to the enzyme control and [S] to the extract.

Statistical analysis

MiniTab software (version 19, State College, PA, USA) was used for the creation, analysis, and graphical output of the Box-Behnken statistical design. Microsoft Excel (Office 365 version) was employed to analyze the data obtained from total phlorotannin quantification and tyrosinase inhibition. The IC₅₀ calculation and plotting were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8, San Diego, CA, USA) with nonlinear regression analysis.

Results and discussion

Optimization of Phlorotannin content in D. justii extract

In this study, ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) was selected as the optimized method for obtaining a phlorotannin-rich extract from D. justii. UAE was chosen due to its proven efficiency, operational simplicity, and environmentally friendly profile compared to both conventional and advanced extraction techniques30,31. The effectiveness of this method lies in the mechanism of acoustic cavitation, where the rapid formation and collapse of microbubbles generates localized high energy, facilitating cell wall disruption and promoting the release of intracellular phenolic compounds32. The selection of UAE over alternative techniques such as microwave-assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, or the use of deep eutectic solvents was based on several comparative advantages. UAE operates under milder conditions, requires simpler equipment, and is less technically demanding, making it particularly suitable for preserving thermo- and photosensitive compounds such as phlorotannins33,34. These features contribute not only to the efficiency of the extraction process but also to the stability and integrity of the bioactive compounds obtained.

Total phlorotannin content (TPhC) in the extracts was quantified using the colorimetric 2,4-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (DMBA) assay. This method was selected for its simplicity and suitability for early-stage screening, where structural elucidation of the phlorotannins is not required7. In contrast to the Folin–Ciocalteu assay, DMBA offers greater specificity for phlorotannins, thereby reducing interference from other phenolic compounds and enhancing analytical accuracy.

Previous reports have highlighted the importance of sample pre-treatment in maximizing extraction efficiency. In this study, the algal biomass was washed with a sodium chloride solution (36 g/L) to minimize osmotic shock and prevent premature cell rupture during handling35. Freeze-drying was chosen as the dehydration method, as it is considered one of the most effective techniques for preserving phenolic content in sensitive samples20,36,37,38. Particle size was also reduced prior to extraction to increase surface area and enhance solvent penetration, which facilitates a greater release of intracellular compounds35.

Although several solvents have been reported for phlorotannin extraction, such as water, methanol, ethanol, and acetone20,39,40, ethanol was selected in this study due to its favorable performance, lower toxicity, and reduced cost, particularly for potential industrial-scale applications35,41,42. Pure ethanol was not evaluated because prior studies have shown that ethanol–water mixtures provide superior extraction content for phlorotannins43.

In addition to solvent composition, parameters such as sample: solvent ratio, extraction temperature, and extraction time significantly influence extraction yield. These parameters may vary depending on the algal species and the extraction technique employed44,45. Therefore, a Box–Behnken Design (BBD) was implemented to systematically evaluate these factors at three levels and to determine the optimal conditions for obtaining an extract with the highest TPhC. Table 3 summarizes the extraction conditions and corresponding TPhC values for each experimental point in the BBD.

The data were analyzed using response surface methodology, which enables the evaluation not only of individual factors but also of their quadratic and interactive effects on the response variable (TPhC)46. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted (Table 4), and the results indicate that the model was statistically significant (p < 0.05), whereas the lack-of-fit test was not, supporting the validity of the model in describing the relationship between the response and the independent variables. The coefficient of determination (R² = 98.09%) and the predicted R² (87.49%) further confirmed the model’s accuracy and predictive capacity. Residual plots revealed no discernible patterns, suggesting that the model adequately fits the experimental data.

According to the response surface analysis of the model, the regression equation predicting total phlorotannin content (TPhC) based on the evaluated factors is as follows (Eq. 3):

Where: A = % Ethanol, B = Solid: liquid ratio, C = Temperature, D = Time.

The response surface plots provide a three-dimensional representation of the variation in total phlorotannin content (TPhC) as a function of two experimental factors while holding the others constant. These visualizations facilitate the identification of optimal factor combinations that yield the highest TPhC. When evaluating the effect of solvent (%EtOH) against other variables, it becomes evident that increasing the %EtOH and decreasing the extraction temperature results in a higher TPhC (Fig. 2A). This trend persists when the solid: liquid ratio, ratio is reduced (Fig. 2B), further supporting the favorable influence of lower sample dilution and milder temperatures when paired with higher ethanol content. In both cases, the positive effect of decreasing temperature and solid: liquid ratio, becomes more pronounced at elevated %EtOH levels. In contrast, when %EtOH is evaluated alongside extraction time (Fig. 2C), the data suggest that TPhC is predominantly influenced by ethanol concentration, with minimal impact from extraction duration. This observation reinforces the central role of solvent polarity in facilitating the extraction of phlorotannins and indicates that extending the extraction time beyond a certain point does not significantly enhance yield under the tested conditions.

Evaluation of the temperature in combination with other factors revealed a consistently negative effect on total phlorotannin content (TPhC); as the temperature decreased, TPhC increased. Surface plots of temperature versus S: L ratio (Fig. 2D) and temperature versus time (Figure F) exhibited a slight curvature, indicative of a quadratic interaction. This curvature was not observed in the plot of temperature versus ethanol concentration (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the quadratic effect of temperature becomes more apparent when %EtOH is fixed at its mid-point (50%). However, this quadratic term was not statistically significant according to the ANOVA (Table 4).

When examining the influence of the S: L ratio against other factors, a similar negative trend was observed. Decreasing both the S: L ratio and temperature (Fig. 2D), or S: L ratio and time (Fig. 2E), led to increased TPhC. In Fig. 2B, the effect of S: L ratio becomes evident only when %EtOH exceeds 50%, reinforcing the interaction-dependent nature of this parameter.

In contrast, the effect of extraction time was more variable and context-dependent. When time was plotted against %EtOH (Fig. 2C), it was clear that solvent concentration was the dominant factor driving TPhC outcomes. High TPhC values were associated with longer extraction times and lower temperatures (Fig. 2F), whereas the inverse was true when paired with S: L ratio, where shorter times led to higher phlorotannin yields (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that extraction time does not exert a consistent effect on TPhC independently but rather in conjunction with other parameters.

Across all response surface plots, ethanol concentration emerged as the most influential factor. When %EtOH was fixed at 50%, the model predicted a maximum TPhC range between 1.1 and 1.5 mg PGE/g. In contrast, when ethanol concentration was varied along the x- or y-axis, TPhC values exceeded 2.0 mg PGE/g, emphasizing the solvent’s primary role in phlorotannin extraction efficiency.

Based on statistical analysis and response optimization, the predicted optimal extraction conditions for maximizing TPhC were determined to be 70% ethanol, a S: L ratio of 1:10, an extraction temperature of 25 °C, and a duration of 20 min. To validate the model, three extracts were prepared under these optimized conditions and their experimentally obtained TPhC values were compared to the theoretical prediction (Table 5). The results demonstrated strong agreement between experimental and predicted values, confirming the model’s predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the low coefficient of variation across replicates confirmed the reproducibility of the optimized extraction process. The extraction yield under these conditions was 9% relative to the dry weight of D. justii.

The optimal ethanol concentration for phlorotannin extraction is influenced by the chosen extraction method due to interactions with other operational variables. Duan et al. (2014), for instance, reported that the optimal ethanol percentage for conventional extraction was 77.9%, whereas for ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) it was 70% 41. In microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), several authors identified optimal ethanol concentrations ranging from 50% to 57% 47,48,49,50. Moreover, algae species significantly influence solvent efficiency. For example, in solid–liquid extraction (SLE), 30% ethanol was optimal for Sargassum fusiforme, while 56% was better for Sargassum muticum51,52. Ethanol at 70% has also been shown to outperform aqueous extraction, as demonstrated by Aminina et al. (2020), who observed higher phlorotannin yields using 70:30 ethanol–water mixtures across different algal species53.

Specifically for UAE, ethanol concentrations between 50% and 70% consistently yielded better results. Ummat et al. (2020) tested UAE on 11 brown algae species and found 50% ethanol to be most effective overall, while other studies reported optimal concentrations of 62.5% for Silvetia compressa and 70% for Ecklonia radiata54. In the present study, 70% ethanol was optimal for Dictyopteris justii. This variability likely stems from species-specific differences in polyphenol–polysaccharide interactions, and is further affected by particle size, which influences solvent penetration and compound diffusion53.

Regarding the solid: liquid ratio, while a higher solvent volume typically improves extraction up to a saturation point51,55, optimal ratios vary widely among species and studies. Reported ideal ratios range from 1:12.23 for Ecklonia stolonifera to 1:30 for Fucus vesiculosus56,57. In this study, 1:10 was optimal for D. justii, highlighting that this parameter depends more on the algal species than the extraction method, especially given that most studies above used UAE.

Temperature also plays a critical role. Though some authors recommend 25 °C 41,55,58,59 or 50 °C 39,51,60, others suggest higher temperatures (up to 120 °C) for SLE52,61. For UAE, lower temperatures often favor phlorotannin stability43,62. In this study, 25 °C produced the highest yield, consistent with Catarino et al. (2019), who noted a decrease in yield above this threshold. While higher temperatures can enhance diffusion and cavitation effects, phlorotannins are thermolabile and prone to degradation under prolonged heating49,51. Hence, temperature must be carefully optimized during UAE63,64.

Extraction time is another critical variable. UAE durations from 1 to 60 min have been evaluated, with no universal consensus. Extended durations may lead to degradation due to free radical formation from cavitation. Some authors suggest short times (2–10 min)41,57,59,65, while others support intermediate (20–30 min)54,66,67 or long durations (60 min)62,68. In this study, 20 min, shortest time tested, yielded optimal results. According to Golshany et al. (2024), the extraction equilibrium for Fucus vesiculosus was reached within 10 min for UAE and 3 h for SLE66. Thus, equilibrium for D. justii likely occurred within or before the 20-minute mark.

Finally, due to the species-specific behavior of phlorotannin content, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for extraction optimization. Zhang et al. (2018) found that algal species accounted for 84% of phlorotannin variability, whereas the extraction method contributed only 13% 69. This reinforces the importance of customizing extraction parameters for each species. The phlorotannin content reported here is the first for D. justii, making direct comparisons difficult. Additionally, most literature uses the Folin–Ciocalteu assay, while this study employed DMBA, which provides higher specificity and may influence result comparability.

The chromatographic analysis from the crude extract of D. justii showed distint profiles at 280 nm and 330 nm. A few compounds could be identified, such as hydroxypentafuhalol-B (Rt:1.5 min, [M + H]+: 671.08), previously reported by Sepulveda (2022)24, and caffeic acid (Rt: 2.0 min, [M-H]-: 181.00), reported for the first time for D. justii. However, some important peaks could not be identified when compared to previously compounds reported to this species (Table 6; Figs. 3 and 4).

In vitro tyrosinase Inhibition by the optimized D. justii extract

As previously mentioned, phlorotannins have been reported to inhibit tyrosinase, the key enzyme involved in melanin biosynthesis. This has spurred considerable research into evaluating both crude algal extracts and isolated phlorotannins as potential natural tyrosinase inhibitors, often compared to conventional agents like kojic acid and arbutin. In this study, the optimized phlorotannin-rich extract from D. justii was evaluated for its relative tyrosinase inhibition capacity (Fig. 5). The extract exhibited a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of 0.51 mg/mL, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.41–0.61 mg/mL. Kojic acid, used as a positive control, had an IC₅₀ of 46.61 µg/mL (95% CI: 42.77–50.67 µg/mL). This is the first report of IC₅₀ for D. justii, marking a novel contribution to the literature.

A prior study by Sepúlveda (2022) demonstrated that the butanolic fraction of a D. justii extract obtained via UAE with 50% methanol showed tyrosinase inhibition exceeding 70% at a concentration of 50 µg/mL 24. In the present work, the crude optimized extract achieved 76.5% inhibition at 1 mg/mL. While it is reasonable to infer that the butanolic fraction might be more potent due to enrichment in polyphenolic compounds, direct comparison is hindered by differences in sample preparation, extraction parameters, and analytical methodology.

Table 7 lists phlorotannins previously reported to inhibit tyrosinase activity. The mechanism of inhibition has been explored through kinetic studies and molecular docking, revealing predominantly non-competitive behavior for compounds like eckol, dieckol, 7-phloroeckol, phlorofucofuroeckol-A, and eckmaxol12,70,71,72. However, competitive inhibition has been observed for eckstolonol and an unidentified phlorotannin13,73. While most studies focus on isolated phlorotannins, Lu et al. (2024) demonstrated that crude extracts from Ascophyllum nodosum also exhibit competitive inhibition38. Thus, further evaluation of the inhibition kinetics of the D. justii extract is necessary to determine whether co-extracted compounds modulate the inhibition mechanism.

Sepúlveda (2022) also identified hydroxypentafuhalol-B and triphlorethohydroxycarmalol in D. justii24. Notably, diphlorethohydroxycarmalol—a carmalol-type phlorotannin—has been shown to inhibit tyrosinase, suggesting that triphlorethohydroxycarmalol may share this activity15. Conversely, no reports were found regarding tyrosinase inhibition by fuhalol-type phlorotannins, making it unclear whether hydroxypentafuhalol-B exhibits such activity. As shown in Table 6, most studies to date have focused on eckol-type phlorotannins, highlighting the need to explore a broader range of structural types. Expanding this knowledge base may uncover novel candidates for cosmetic applications aimed at managing hyperpigmentation.

24.

Finally, although caffeic acid was also identified in the optimized D. justii extract, its presence does not necessarily explain the tyrosinase inhibitory activity observed, since caffeic acid is not a classical inhibitor but rather a substrate for the enzyme. García-Jiménez et al. demonstrated that caffeic acid undergoes enzymatic oxidation by tyrosinase, producing unstable o-quinones and ultimately acting as a suicide substrate rather than directly inhibiting catalytic activity75.Thus, while caffeic acid may contribute to oxidative processes within the extract, it is unlikely to be responsible for the observed inhibition of tyrosinase activity, which suggests that phlorotannins are the primary contributors.

Conclusion

This study successfully optimized the ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) of phlorotannins from the brown macroalga Dictyopteris justii, identifying ethanol concentration as the most influential factor in maximizing phlorotannin yield, followed by the solid: liquid ratio, extraction temperature, and specific factor interactions. The optimal extraction conditions were determined to be 70% ethanol, a 1:10 solid-to-liquid ratio, 25 °C, and 20 min. Under these conditions, a total phlorotannin content of 2.874 ± 0.069 mg PGE/g dry extract was achieved, falling within the predicted confidence interval and demonstrating the robustness and reproducibility of the model. Additionally, the optimized extract exhibited significant tyrosinase inhibitory activity, with an IC₅₀ value of 0.51 mg/mL, being reported for the first time for D. justii. This finding not only reinforces the potential of phlorotannin-rich extracts from this species as bioactive ingredients in skin depigmentation strategies but also expands the current understanding of Colombian Caribbean algal biodiversity with promising cosmeceutical applications.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Raw data can be shared upon request form dmaragonn@unal.edu.co.

References

Pillaiyar, T., Manickam, M. & Jung, S. H. Downregulation of melanogenesis: drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov Today. 22, 282–298 (2017).

Mironiuk, M. & Chojnacka, K. The environmental benefits arising from the use of algae biomass in industry. in Algae Biomass: Characteristics and Applications (eds Chojnacka, K., Wieczorek, P. P., Schroeder, G. & Michalak, I.) 7–16 (Springer, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74703-3. (2018).

Motshekga, S. C., Temane, L. T., Orasugh, J. T. & Ray, S. S. Marine algae and their importance. in Current Status of Marine Water Microbiology (eds Soni, R., Suyal, D. C., Morales-Oyervides, L. & Fouillaud, M.) 67–124 (Springer, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5022-5. (2023).

Wang, H. M. D., Chen, C. C., Huynh, P. & Chang, J. S. Exploring the potential of using algae in cosmetics. Bioresour Technol. 184, 355–362 (2015).

Ferreira, M. S., Resende, D. I. S. P., Lobo, S. & Sousa, J. M. Almeida, I. F. Marine ingredients for sensitive skin: market overview. Mar. Drugs 2021. 19, 464 (2021).

Tagliapietra, B. L. & Clerici, M. T. P. S. Brown algae and their multiple applications as functional ingredient in food production. Food Res. Int. 167, 112655 (2023).

Shrestha, S., Zhang, W., Smid, S. D. & Phlorotannins A review on biosynthesis, chemistry and bioactivity. Food Biosci. 39, 100832 (2021).

Erpel, F., Mateos, R., Pérez-Jiménez, J., Pérez-Correa, J. R. & Phlorotannins From isolation and structural characterization, to the evaluation of their antidiabetic and anticancer potential. Food Res. Int. 137, 109589 (2020).

Hermund, D. B., Torsteinsen, H., Vega, J., Figueroa, F. L. & Jacobsen, C. Screening for new cosmeceuticals from brown algae fucus vesiculosus with antioxidant and Photo-Protecting properties. Mar. Drugs. 20, 687 (2022).

Venkatesan, J. et al. Encyclopedia Food Chem. 515–527 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22360-3. (2019).

Sanjeewa, K. K. A., Kim, E. A., Son, K. T. & Jeon, Y. J. Bioactive properties and potentials cosmeceutical applications of phlorotannins isolated from brown seaweeds: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 162, 100–105 (2016).

Kang, S. M. et al. Molecular Docking studies of a phlorotannin, dieckol isolated from Ecklonia Cava with tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 311–316 (2012).

Manandhar, B. et al. Phlorotannins with potential Anti-Tyrosinase and antioxidant activity isolated from the marine seaweed Ecklonia stolonifera. Antioxid. 2019. 8, 240 (2019).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Slow-Binding Inhibition of tyrosinase by Ecklonia Cava phlorotannins. Mar. Drugs 2019. 17, 359 (2019).

Heo, S. J. et al. Inhibitory effect of diphlorethohydroxycarmalol on melanogenesis and its protective effect against UV-B radiation-induced cell damage. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48, 1355–1361 (2010).

Heo, S. J. et al. Effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia Cava on melanogenesis and their protective effect against photo-oxidative stress induced by UV-B radiation. Toxicol. In Vitro. 23, 1123–1130 (2009).

Baweja, P., Kumar, S., Sahoo, D. & Levine, I. Biology of Seaweeds. in Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention 41–106Elsevier Inc., https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802772-1.00003-8 (2016).

Freile-Pelegrín, Y. & Robledo, D. Bioactive phenolic compounds from algae. in Bioactive Compounds from Marine Foods: Plant and Animal Sourcess (eds Hernández-Ledesma, B. & Herrero, M.) 113–129 (Wiley Blackwell, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412893.CH6. (2013).

Lopes, G. et al. Can phlorotannins purified extracts constitute a novel Pharmacological alternative for microbial infections with associated inflammatory conditions? PLoS One 7, e31145 (2012).

Ivane, N. M. A., Ozoh, C. & Michelle, D. T. F. Exploring the bioactive properties, extraction methods, and detection techniques of phlorotannins from brown algae: implications for health and nutraceutical applications. Aquaculture International 2025 33:3 33, 1–35 (2025).

Stern, J. L., Hagerman, A. E., Steinberg, P. D., Winter, F. C. & Estes, J. A. A new assay for quantifying brown algal phlorotannins and comparisons to previous methods. J. Chem. Ecol. 22, 1273–1293 (1996).

Zatelli, G. A., Philippus, A. C. & Falkenberg, M. An overview of odoriferous marine seaweeds of the Dictyopteris genus: insights into their chemical diversity, biological potential and ecological roles. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 28, 243–260 (2018).

Vides, M., Alonso, D., Castro, E. & Bolaños, N. Lista de especies Reserva de la Biosfera Seaflower. Biodiversidad del mar de los siete colores. Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras – INVEMAR y Corporación para el Desarrollo Sostenible del Archipiélago de San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina - CORALINA http://cinto.invemar.org.co/sai/#/ (2016).

Sepúlveda Sánchez L. Y. Búsqueda De Compuestos Con Posible Actividad Inhibitoria De Enzimas De interés cosmético a Partir De Algas Del Caribe Colombiano (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2022).

Teixeira, V. L. et al. Hydroperoxysterols from the Brazilian Brown Seaweeds Dictyopteris justii and Spatoglossum schroederi (Dictyotales): A Defensive Strategy against Herbivory. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X0600100405 1, 293–297 (2006).

Hernández, A. R. et al. Algae extract-based nanoemulsions for photoprotection against UVB radiation: an electrical impedance spectroscopy study. Scientific Reports 2025 15:1 15, 1–17 (2025).

Schmitz, C. et al. UVR and PAR absorbing compounds of marine brown macroalgae along a latitudinal gradient of the Brazilian Coast. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 178, 165–174 (2018).

Jégou, C., Kervarec, N., Cérantola, S. & Bihannic, I. Stiger-Pouvreau, V. NMR use to quantify phlorotannins: the case of cystoseira tamariscifolia, a phloroglucinol-producing brown macroalga in Brittany (France). Talanta 135, 1–6 (2015).

Sigma-Aldrich. Technical Bulletin. Product Information Tyrosinase Inhibitor Screening Kit (Colorimetric) 1–3 Preprint at. (2016).

Selvaraj, S., Bains, A., Sharma, M., Chawla, P. & Sridhar, K. Freshwater edible algae polysaccharides: A recent overview of novel extraction Technologies, Characterization, and future food applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10924-023-03049-9 (2023).

Panzella, L. et al. Bioactive phenolic compounds from Agri-Food wastes: an update on green and sustainable extraction methodologies. Front. Nutr. 7, 60 (2020).

Aswathy, V. P. et al. Unveiling the potential of freshwater edible algae: innovative extractions and functional food applications. South. Afr. J. Bot. 177, 643–664 (2025).

Barba, F. J., Zhu, Z., Koubaa, M., Sant’Ana, A. S. & Orlien, V. Green alternative methods for the extraction of antioxidant bioactive compounds from winery wastes and by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 49, 96–109 (2016).

Pingret, D., Fabiano-Tixier, A. S., Bourvellec, C., Le, Renard, C. M. G. C. & Chemat, F. Lab and pilot-scale ultrasound-assisted water extraction of polyphenols from Apple pomace. J. Food Eng. 111, 73–81 (2012).

Cotas, J. et al. Seaweed phenolics: from extraction to applications. Mar. Drugs 2020. 18, 384 (2020).

Balboa, E. M., Conde, E., Moure, A., Falqué, E. & Domínguez, H. In vitro antioxidant properties of crude extracts and compounds from brown algae. Food Chem. 138, 1764–1785 (2013).

Kumar, L. R. G. et al. Phlorotannins–bioactivity and extraction perspectives. J. Appl. Phycol. 34, 2173–2185 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. The influence of drying methods on extract content, tyrosinase activity inhibition, and mechanism in ascophyllum nodosum: A combined microstructural and kinetic study. Food Chem. 458, 140230 (2024).

Leyton, A. et al. Identification and efficient extraction method of phlorotannins from the brown seaweed macrocystis pyrifera using an orthogonal experimental design. Algal Res. 16, 201–208 (2016).

Golshany, H. et al. Exploring fucus vesiculosus phlorotannins: insights into chemistry, extraction, purification, identification and bioactivity. Food Biosci. 61, 104769 (2024).

Duan, X. et al. Optimizing extraction methods by a comprehensive experimental approach and characterizing polyphenol compositions of Ecklonia radiata. Food Chem. 455, 139926 (2024).

Gall, E. A., Lelchat, F., Hupel, M., Jégou, C. & Stiger-Pouvreau, V. Extraction and purification of phlorotannins from brown algae. in Natural Products from Marine Algae. Methods and Protocols (eds Stengel, D. B. & Connan, S.) 131–143 (Humana, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2684-8_7. (2015).

Vázquez-Rodríguez, B., Gutiérrez-Uribe, J. A., Antunes-Ricardo, M. & Santos-Zea, L. Cruz-Suárez, L. E. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phlorotannins and polysaccharides from silvetia compressa (Phaeophyceae). J. Appl. Phycol. 32, 1441–1453 (2020).

Okeke, E. S. et al. Aquatic phlorotannins and human health: Bioavailability, Toxicity, and future prospects. Nat Prod. Commun 16,1-23(2021).

Cassani, L. et al. Seaweed-based natural ingredients: stability of phlorotannins during extraction, storage, passage through the Gastrointestinal tract and potential incorporation into functional foods. Food Res. Int. 137, 109676 (2020).

Ferreira, S. L. C. et al. Box-Behnken design: an alternative for the optimization of analytical methods. Anal. Chim. Acta. 597, 179–186 (2007).

Abdelhamid, A. et al. Optimized Extraction, preliminary characterization and evaluation of the in vitro anticancer activity of Phlorotannin-Rich fraction from the brown Seaweed, cystoseira sedoides. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 28, 892–909 (2019).

Amarante, S. J. et al. Microwave-Assisted extraction of phlorotannins from fucus vesiculosus. Mar. Drugs 2020. 18, 559 (2020).

Toan, T. Q. et al. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted extraction of Phlorotannin from sargassum swartzii (Turn.) C. Ag. With Ethanol/Water. Nat Prod. Commun 16, 1-11 (2021).

He, Z. et al. Optimization of the microwave-assisted extraction of phlorotannins from Saccharina Japonica Aresch and evaluation of the inhibitory effects of phlorotannin-containing extracts on HepG2 cancer cells. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 31, 1045–1054 (2013).

Zheng, H. et al. Optimized extraction of polyphenols with antioxidant and anti-biofilm activities and LC-MS/MS-based characterization of phlorotannins from sargassum muticum. LWT 198, 116069 (2024).

Yoon, M. et al. Extraction optimization for Phlorotannin recovery from the edible brown seaweed Ecklonia Cava. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 26, 801–810 (2017).

Aminina, N. M., Vishnevskaya, T. I., Karaulova, E. P., Epur, N. V. & Yakush, E. V. Prospects for the use of commercial and potentially commercial brown algae of the Far Eastern seas as a source of polyphenols. Russ J. Mar. Biol. 46, 34–41 (2020).

Ummat, V. et al. Optimisation of ultrasound Frequency, extraction time and solvent for the recovery of Polyphenols, phlorotannins and associated antioxidant activity from brown seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2020. 18, 250 (2020).

Catarino, M. D., Silva, A. M. S., Mateus, N. & Cardoso, S. M. Optimization of phlorotannins extraction from fucus vesiculosus and evaluation of their potential to prevent metabolic disorders. Mar. Drugs. 17, 162 (2019).

Park, Y. S., Roy, V. C., Park, J. S., Zhang, W. & Chun, B. S. Optimization of subcritical water extraction parameters of phlorotannins from brown Alga (Ecklonia stolonifera): bipotentialities and possible applications. J. Supercrit Fluids. 218, 106502 (2025).

Golshany, H., Kamal, A., Yu, Q. & Fan, L. Optimizing phlorotannins extraction from fucus vesiculosus using Box-Behnken design: unveiling techniques for enhanced antioxidant activity and metabolic enzyme Inhibition. Algal Res. 83, 103723 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Extraction and identification of phlorotannins from the brown Alga, sargassum fusiforme (Harvey) Setchell. Mar. Drugs 2017. 15, 49 (2017).

Sánchez-Bonet, D. et al. RP-HPLC-DAD determination of the differences in the polyphenol content of fucus vesiculosus extracts with similar antioxidant activity. J. Chromatogr. B. 1184, 122978 (2021).

Ashokan, A. et al. Modelling and optimization of Phlorotannin extraction from stoechospermum marginatum using response surface methodology and evaluating its activity against marine microfouling bacteria. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 15, 7465–7481 (2024).

Ferreira, R. M. et al. Water extraction kinetics of bioactive compounds of fucus vesiculosus. Molecules 2019. 24, 3408 (2019).

Dang, T. T. et al. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions for phenolic content and antioxidant activities of the Alga hormosira banksii using response surface methodology. J. Appl. Phycol. 29, 3161–3173 (2017).

Rutkowska, M., Namieśnik, J. & Konieczka, P. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. in The Application of Green Solvents in Separation Processes (eds. Peña-Pereira, F. & Tobiszewski, M.) 301–324 (Elsevier, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805297-6.00010-3

Chemat, F. et al. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 34, 540–560 (2017).

Gisbert, M., Barcala, M., Rosell, C. M., Sineiro, J. & Moreira, R. Aqueous extracts characteristics obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction from ascophyllum nodosum seaweeds: effect of operation conditions. J. Appl. Phycol. 33, 3297–3308 (2021).

Golshany, H., Yu, Q. & Fan, L. Comparative extraction and antioxidant potential of bioactive compounds from fucus vesiculosus: kinetic modeling and UPLC-Q-TOF-MS phenolic profiling. Food Biosci. 57, 103575 (2024).

Kadam, S. U., Tiwari, B. K., Smyth, T. J. & O’Donnell, C. P. Optimization of ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive components from brown seaweed ascophyllum nodosum using response surface methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 23, 308–316 (2015).

Han, D., Zhu, T. & Row, K. H. Ultrasonic extraction of phenolic compounds from laminaria Japonica Aresch using ionic liquid as extraction solvent. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 32, 2212–2216 (2011).

Zhang, R. et al. A comparative assessment of the activity and structure of phlorotannins from the brown seaweed Carpophyllum flexuosum. Algal Res. 29, 130–141 (2018).

Lee, S. H. et al. Cellular activities and Docking studies of Eckol isolated from Ecklonia Cava (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) as potential tyrosinase inhibitor. Algae 30, 163–170 (2015).

Yoon, N. Y., Eom, T. K., Kim, M. M. & Kim, S. K. Inhibitory effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia Cava on mushroom tyrosinase activity and melanin formation in mouse B16F10 melanoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 4124–4129 (2009).

Oh, G. W. et al. Tyrosinase inhibitory and antioxidant potential of Eckmaxol isolated from the brown seaweed Ecklonia maxima. South. Afr. J. Bot. 157, 648–655 (2023).

Kang, H. S. et al. Tyrosinase inhibitors isolated from the edible brown AlgaEcklonia stolonifera. Arch. Pharm. Res. 27, 1226–1232 (2004).

Kim, K. N. et al. Whitening effect of octaphlorethol A isolated from ishige foliacea in an in vivo zebrafish model. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 448–451 (2015).

Garcia-Jimenez, A. et al. Action of tyrosinase on caffeic acid and its n-nonyl ester. Catalysis and suicide inactivation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 107, 2650–2659 (2018).

Acknowledgements

To the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible by Permission No 121 of 22 January 2016 (modification otrosí No 7) for collecting samples.

Funding

‘BALCAR-Q: Bioprospección y Química de Algas del Caribe’ program (code: 1101-852-69964), Contract No. 80740-739-2020, funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de Colombia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.H.: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Original Draft G.M.C.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing D.M.A.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández, A.C., Costa, G.M. & Aragón, M. Optimization of ultrasound extraction of phlorotannin rich extract from Dictyopteris justii with tyrosinase Inhibition. Sci Rep 16, 7229 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35253-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35253-7