Abstract

Multi-energy systems are one of the main solutions to facilitate the integration of renewable energy resources in the smart energy system. To this end, this paper presents a comprehensive structure for the energy system that integrates the electrical, hydrogen, and water sections for sustainable management of modern energy systems. The presented model offers cooperative scheduling for neighbor multi-energy systems that provides the opportunity of local energy trading among them. Also, it focuses on the water system and seeks to supply potable water for the energy systems by a water well, desalination unit, and water storage tank. Besides, compressed air energy storage is developed to utilize the surplus generation of renewable energy to provide an efficient operation for the system. To control the uncertain nature of renewable generation, the energy systems can take part in the electrical and thermal demand-side programs to manage their consumption in response to the signal prices. The proposed model is tested on a standard case study, and the numerical results show that the cooperation among energy systems reduces their operating cost and unserved energy by $ 23.91 and 64.317 kWh compared to autonomous operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

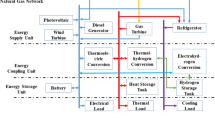

In modern energy systems, multi-energy systems (MES) or energy hub systems play an important role in the transition toward low-carbon systems. The MES facilitates the integration of renewable energy sources (RES), such as photovoltaic and wind energy, in the system and provides a low-carbon system. This sector coupling allows the MES to convert the surplus energy in one domain into another form of energy. The link between energy systems improves system flexibility and reliability of MES, and enables a better energy management framework for managing RES’s fluctuations and demand variations1,2. This integration seeks to supply the energy systems to supply their demand through the local energy resources. Therefore, the application of MES improves the power quality indices, such as the energy losses and voltage deviation, because the energy is passed from short lines3,4.

Literature review

In recent years, different studies have been conducted on the operation of MES. The authors in5 studied the energy management of a local MES that includes demand response programs. A multi-objective optimization algorithm has been developed in6 that facilitates the integration of RES in the distribution system. The demand response programs are considered to control the uncertainty of RES. However, the efficiency of compressed air energy storage systems on the performance of MES has not been studied. The authors in7 propose a multi-layer power quality-based model for local energy systems. The first layer simultaneously considers the operation cost, unserved energy, and carbon emission. The second layer investigates the power quality indices, such as harmonic and power losses. However, the application of power-to-hydrogen and hydrogen-to-power systems has not been studied. A multi-objective sustainable management has been developed in8 that couples the electrical, thermal, and cooling systems to enhance the system efficiency. The proposed model simultaneously minimizes the operating cost and water extraction from underground sources. However, the application of hydrogen systems, compressed air energy storage systems, and power quality indices has not been studied.

A novel algorithm has been proposed in9 that investigates the impact of weather conditions and thermal comfort of users on the MES scheduling using a two-stage model. An enhanced quantum particle swarm optimization (QPSO) algorithm has been presented in10 that investigates the interaction among several MES. The proposed model integrates the electricity, heating, and transportation sections to maximize profits and EV aggregators’ charging performance. However, the water-energy nexus in the MES is not studied. A loop-based multi-layer framework has been proposed in11 that presents sustainable scheduling in MES. The proposed model studies the water-energy nexus in the local energy system to simultaneously supply the needed electricity and potable water. However, the heating, cooling, and hydrogen systems are not integrated into the proposed structure.

In12, a strong coordination between the electricity and gas networks has been developed that investigates the impact of solar renewable resources and demand response programs on the operation of MES. However, the electric chiller, absorption chiller, and ice storage conditioner have not been considered. Reference13 evaluates the performance of multiple players and electric vehicles on the integrated electrical and thermal MES. However, water scheduling, hydrogen-to-power, and power-to-hydrogen have not been incorporated into the proposed structure. The authors in14 addressed a stochastic approach to consider the uncertainty of RES in the operation of MES. The proposed model studies the impact of electric vehicles and compressed air energy storage, while the demand response programs, hydrogen storage tank, water storage tank, and desalination units are not modeled.

Reference15 studies the operation of residential MES considering the uncertainty of load and RES. However, the efficiency of ice storage conditioners and thermal energy storage technologies has not been investigated. The integration of gas network, electrical, and heat systems is studied in16 using stochastic optimization. Nevertheless, the cooling, hydrogen, and water sections have not been discussed. The authors in17 present a sustainable algorithm for coalition forming in the water-energy nexus MES. The proposed model considers both economic and reliability indices to define the best coalitions among different MES. However, the integration of hydrogen, thermal, and cooling systems is not considered.

Hydrogen systems are known as one of the solutions to control the uncertainty of renewable generation. The authors in18 investigate the application of hydrogen systems in the power generation networks and electric vehicles. In the hydrogen systems, the electrolyzer unit can be used to generate hydrogen from RES for hydrogen production. The produced hydrogen can be used by the fuel cell unit during peak hours for electricity generation18. Sameti et al. in19 present an economic scheduling model to find the optimal size of a green hydrogen system integrated with a wind farm. The proposed model considers the wind curtailment profile, market prices, and storage and transportation costs to maximize the profit of the system. However, the water-electricity nexus and integration of heating and cooling systems are not studied. The authors in20 integrated the fuel cell, electrolyzer, and hydrogen storage tank in the MES to increase the flexibility of the MES. However, the water-energy nexus and compressed air energy storage system has not been studied.

Research gap

According to the literature review, a comprehensive structure that integrates the electrical, cooling, water, hydrogen, and heating systems has been overlooked. Most research works only focus on the energy supply of MES, while the potable water for the system has not been neglected. Due to the increasing penetration of renewable generation in modern energy systems, integrating energy infrastructures appears to be essential. In this situation, the coordination among neighboring MESs becomes significantly important, while this coordination needs to be further studied.

Contributions

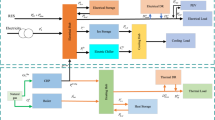

The main focus of this study is to optimize the operational cost of MES while enabling electricity exchange among neighboring MEGs. The proposed structure integrates the RES, power-to-hydrogen, hydrogen-to-power, absorption chiller, electric chiller, ice storage conditioner, hydrogen tanks, desalination units, water storage tank, boiler, combined heat and power, compressed air energy storage systems, and demand response programs to provide a reliable scheduling mechanism. Therefore, this paper aims to utilize optimal operation to address the energy-water nexus in MES, along with compressed air storage. Therefore, the major contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

-

This paper presents a comprehensive structure for multi-energy systems that merges the hydrogen and water sections with electrical, heating, and cooling systems. The power-to-hydrogen and hydrogen-to-power devices have been incorporated to increase the flexibility of the energy hubs and provide more efficient scheduling for the system.

-

This paper proposes a collaborative scheduling that creates a large coalition for the energy hub systems. This collaborative model provides an opportunity for the energy hub systems to locally trade together and compensate for their shortage with other energy hub systems. Also, a compressed air energy storage system is considered in the coalition to convert the surplus generation of RES and utilize it during peak hours.

-

The dynamic model of the desalination unit is formulated to remove the mineral material from the salt water and provide the freshwater. Also, the water storage tank is integrated into the system to increase the efficiency of the water system.

Paper structure

The structure of this paper is as follows: The objective function and constraints are provided in section “Mathematical model”. Simulation results and analysis are presented in section “ Simulation and numerical results”. Finally, section “Conclusion” concludes the paper and outlines future work.

Mathematical model

In this mathematical model, the objective functions and operational constraints are presented.

Objective function

This paper proposes an approach to reduce the costs of the multi-agent system. Equation (1) represents the cost function of energy systems, which includes the cost of purchasing electricity from the grid, the cost of natural gas for the cogeneration unit, the operational and maintenance cost coefficients of cogeneration units and boilers, and the penalty cost for load shedding.

Demand response programs

This section models the electrical and thermal demand response programs to convert the passive customers to active ones in response to electricity prices. Equations (2)-(6) provide a general formulation for electrical and thermal demand response programs.

Where \(j \in \left\{ {e,~h} \right\}\) refers to the type of demand response programs. Equation (2) shows that the amount of shifted-up and shifted-down electric and thermal loads which should be the same. Equations (3) and (4) show the maximum shifted-up and shifted-down power, respectively. Equation (5) prevents simultaneous shifted-up and shifted-down powers. Equation (6) indicates the maximum allowable load curtailment.

Energy storage systems

This section presents a general formulation for the energy storage systems. The energy hubs utilize different electrical, thermal, and cooling storage systems to supply their demands in the best manner and control the uncertain nature of RES. Equations (7)-(12) present the mathematical formulation of energy storage systems.

where \(f \in \left\{ {es,~hs,~cs} \right\}\) refers to the type of energy storage systems. The indices \(es\), \(hs\), and \(cs~\)are related to the electric, thermal, and cooling energy storage systems, respectively. Equation (7) shows the energy level in the storage system. Equation (8) limits the state-of-charge of energy storage devices. Equations (9) and (10) show the maximum bounds of charging and discharging powers, respectively. Equation (11) prevents energy storage devices from being simultaneously charged and discharged. Finally, Eq. (12) states that the energy level stored in the storage systems must be the same at the beginning and end of the operational period.

Water section and water balance

The water system includes a water well, a water storage tank, and a desalination unit. Both the water storage pump and the water well pump consume electricity during charging and discharging. Also, the desalination unit uses electricity to convert the salt water to freshwater. Equation (13) shows that the total required water by the energy hub systems should be equal to the water obtained from the water well, the desalination unit, and the water storage system.

Equations (14)–(18) indicate the formulation of the water storage tank. The hourly level of stored water is shown in Eq. (14). Equation (15) limits the stored water level between minimum and maximum values. Equations (16) and (17) limit the charging and discharging states. Finally, Eq. (18) prevents simultaneous charging and discharging of water.

Equation (19) indicates the power consumption of the pump for extracting water from a water well. Also, Eq. (20) calculates the power consumption by the pump of the water storage tank.

The power consumption of the desalination unit is calculated as shown in Eq. (21).

Desalination device uses reverse osmosis of saline water, with its maximum production indicated in Eq. (22).

The total power consumption of the water system (water storage, well pump, and desalination unit) is calculated from Eq. (23).

Hydrogen section

In this paper, a hydrogen system is considered that consists of fuel cell units, electrolyzer, and hydrogen storage tanks. The electrolyzer is known as a power-to-hydrogen system and can utilize the surplus generation of RES to produce hydrogen. The produced hydrogen can be sold to industry or stored in the hydrogen storage tank. The fuel cell units, as hydrogen-to-power systems, can utilize stored hydrogen to generate electricity during peak hours to decrease the total cost and unserved energy in the energy hub systems. The mathematical formulation of the hydrogen system is presented in Eqs. (24)–(29).

The maximum and minimum electricity usage by electrolyzer units are shown in Eq. (24). Equation (25) defines the maximum and minimum electricity generation by the fuel cell. Also, Eq. (26) ensures that the electrolyzer and fuel cell unit are not work at the same time.

Also, Eqs. (27)–(29) present the volume of stored hydrogen in the storage tank at each time slot. The hourly stored hydrogen is formulated in Eq. (27). Equation (28) indicates the minimum and maximum stored hydrogen in the storage tank. Finally, Eq. (29) indicates that the level of stored hydrogen at the beginning and end of the day should be the same.

Electricity balance in MES

Equation (30) illustrates the electrical balance. Also, Eq. (31) limits the imported/exported electricity from/to the grid.

Heat section and heat balance in MES

Equation (32) presents the heat balance. Finally, the heat transfer limit is presented in Eq. (33).

Equation (34) indicates the heat generated by the boiler.

Equations (35) and (36) show the electrical and thermal generation of combined heat and power units, respectively.

Equations (37) and (38) limit the natural gas usage by the combined heat and power units and the boiler, respectively.

Cooling section and cooling balance in MES

Equation (39) presents the cooling balance for each energy hub. Equation (40) calculates the amount of stored cooling in the ice storage conditioner. Equation (41) limits the electricity consumption by the ice storage conditioner. Equation (42) describes the cooling generated by the absorption chiller. Also, Eq. (43) limits the imported heat to the absorption chiller.

Besides, the generated cooling by the electric chiller, and the maximum electricity usage by this device are limited by Eqs. (44) and (45), respectively.

Compressed air storage

Equation (46)–(52) present the formulation of compressed air energy storage. \({P_{CAES}}\left( {i,t} \right)\) refers to the power consumption in the compressed air storage unit, while \({P_{C,S}}\left( {i,t} \right)\) pertains to the power produced in the compressed air storage. Equation (46) shows the amount of input air to the storage. The generated electricity by the compressed air storage is shown by Eq. (47). The minimum and maximum compressed air input and output are shown in Eqs. (48) and (49), respectively. Equation (50) prevents simultaneous charging and discharging. Equation (51) shows the hourly stored air. Finally, the amount of stored air at any moment is limited by Eq. (52).

Simulation and numerical results

The multi-faceted operation scheme of interconnected multi-energy systems along with compressed air storage has been examined with three hubs. Each hub consists of a combination of RES and energy storage systems. To investigate this idea, the existing information from references21,22 is reviewed along with the final results obtained from the simulation of the model. Figure 1 shows the electricity price curve. The electric and thermal loads of the three energy hubs are depicted in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

The parameters of the compressed air energy storage systems are taken from22 and presented in Table 1. Also, the characteristics of electrical and thermal demand response programs are taken from21 and shown in Table 2. Table 3 presents the coefficient performance of electric chiller, absorption chiller, and ice storage conditioner that are taken from21.

The proposed model is formulated as a mixed-integer nonlinear program (MINLP) and solved using the BARON solver within the General Algebraic Modeling System (GAMS) environment. It was implemented on a Core i7 system with 4 GB of RAM. The model has 4,178 continuous and 1,152 discrete variables, and the total execution time was 16 s. Table 4 compares the proposed model performance with the autonomous scheduling.

The results of Table 4 show that collaboration among energy hubs decreases the operating cost of energy hub systems by $ 23.91, and decreases from $ 1462.97 to $ 1439.06. This cost reduction is provided because the proposed model considers the energy trading among energy hub systems. The results show that in the autonomous operation, the amount of unserved energy is 64.31 kWh. In other words, some of the energy hubs cannot fully supply their load demands. While in the proposed model, the energy hubs can support their power shortage through other energy hub systems. Besides, the numerical results presented that the energy hubs prefer to supply potable water by extracting water from underground sources. It should be noted that the electricity consumption of the water pump for extracted water is less than the energy consumption of the desalination unit. Therefore, the energy hubs are not willing to operate the desalination unit.

Figures 4 and 5 show the electrical and thermal energy produced by combined heat and power (CHP) units, respectively.

According to Fig. 4, the highest production capacity of the CHP unit occurs between 14:00 and 17:00. There are several reasons for this. First, this time frame represents peak consumption hours, during which consumers use more energy. Therefore, the energy hubs are required to supply additional energy. Second, during these hours, electricity prices in the upper market are high, prompting hubs to prefer local units for energy supply. Figure 5 shows the amount of heat produced by the CHP units over 24 h. The highest heat output is observed between 13:00 and 16:00, when these units are operational to supply electrical energy while simultaneously producing thermal energy. Figure 6 illustrates the thermal energy produced by the boiler.

As shown in Fig. 6, in the early hours of the day, boilers produce more heat. During these hours, the CHP units operate at their minimum production, and thus the boilers are responsible for supplying the thermal energy required by consumers. In the early hours of the day, electricity prices are low, and the hubs prefer to source their electrical needs from the grid instead of using the CHP units. Since the CHP units have low production during these hours, the boilers strive to meet the thermal load. Conversely, during peak demand hours, because the CHP units are at their maximum production, there is less reliance on boilers, and their thermal output decreases compared to the early hours of the day. Figure 7 presents the cooling balance in all of the energy hub systems.

According to Fig. 7, energy hub systems prefer to supply the largest portion of their consumption through electric chillers because they have a larger coefficient of performance than absorption chillers. However, during peak hours, the electric chillers cannot fully meet the cooling load, and the energy hub systems utilize the absorption chillers. Additionally, it can be observed that the ice storage conditioners are discharged during peak hours to assist the energy hub system in maintaining a cooling balance. These devices consume electricity during off-peak hours, at low electricity prices, to generate cooling energy and store it in a storage tank. Figure 8 shows the water balance in all of the energy hub systems.

Due to the lower electric consumption of the water well pump, the energy hub systems meet a large portion of their water load through extracted water from underground. The electricity consumption of water desalination units is more than that of the water well pump. Therefore, the energy hub system only uses desalination units when necessary to minimize the total operating costs. Also, it can be seen that the water storage tanks are charged during off-peak hours because the electricity prices are low, and the electricity cost for pumping water to the storage tank will be low. The stored water is discharged during peak hours to reduce the utilization of desalination units and water wells and reduce the costs of the system.

Figure 9 shows the extracted water from the well. Simulation results show that hubs tend to avoid using desalination units, with their output consistently at zero, and potable water is sourced solely from wells. Since the energy consumption of desalination units exceeds that of the electric pumps installed for the well, energy hubs procure all their potable water from the well to reduce electricity consumption and their costs.

Figure 10 illustrates the operation of compressed air energy storage. During off-peak hours when electricity prices are low, the compressed air energy storage compresses air using electrical energy and stores it. In peak demand hours, when electricity prices are high, the compressed air energy storage can be injected into gas units for electricity generation, thereby helping to reduce costs.

Figure 11 shows the performance of the hydrogen system (electrolyzer, fuel cell, and hydrogen storage tank) that is located in energy hub 2.

Figure 11 shows that during hours 3–5, when the electricity prices and load demand are low, the energy hub system utilizes the electrolyzer to consume electricity and produce hydrogen. The produced hydrogen is stored in the hydrogen storage tank. During peak hours, when the electricity prices and load demand are high, hydrogen is imported to fuel cell units to generate electricity. This performance reduces the operating cost of the Energy Hub 2 due to the difference in peak and off-peak prices. The numerical results show that the hydrogen system reduces the operating cost of the energy hub system 2 by $ 24.6 per month.

The electricity prices have increased by up to 50% to show the performance of the proposed collaborative model on the electricity prices. Table 5 compares the operating cost of the energy hub systems in both autonomous and collaborative scheduling. The Electricity Price Ratio (EPR) is introduced to present the change in electricity price relative to the base prices (Fig. 1).

It is easily observed that as ERP increases, the total costs of energy hub systems also increase because the energy hub systems must pay more for purchased electricity. However, the proposed model is more efficient than autonomous scheduling. When EPR is 1, the operating cost of the energy hub systems is $ 1462.97 in autonomous operation. By increasing EPR to 1.5, the operating cost of the system is increased by 8.07% and changes $ 1581.14. Also, in the collaborative scheduling, the operating cost of the system is increased by 6.55% and changes from $ 1439.06 to $ 1533.42. However, at each EPR level, the operating costs of the proposed collaborative model are less than those of autonomous scheduling, because the energy hub systems can reduce their energy transaction with the main grid and import the required energy from other hubs. Table 6 investigates the efficiency of battery and thermal energy storage systems on the daily and monthly operation of energy hub systems.

Table 6 presents that the integration of both electrical and thermal energy storage systems reduces the operating cost of the energy hub systems by $9 per day and $268 per month, respectively. These devices can store electrical and heat energy during off-peak hours when prices are less than at other times. When the reliability of the system is compromised or the prices are high, the stored energies can be injected into the system to reduce shortages and operating costs. Also, the numerical results show that both electrical and thermal energy storage systems have the same efficiency, and reduce the operating cost of the energy hub systems by $ 5 per day and $ 150 per month, respectively.

Also, Fig. 12 studies the impact of electrical energy storage systems on the operating cost of the energy hub systems by a sensitivity analysis. A positive coefficient, as the electrical energy storage system factor (EESSF), is introduced that presents the scale of the energy storage system compared to the base case.

By increasing the EESSF, the operating costs of the energy hub systems have decreased because they can store more energy during low electricity prices. When the capacity of the electrical energy storage systems is fivefold increased, the operating cost is reduced from $ 1439 to $ 1418 in the collaborative mode. In autonomous operation, this capacity expansion reduces the operating cost of the energy hub systems by $ 24.23 per day and reaches from $ 1439 to $ 1418. Also, it increases the ability of the system to control the intermittent behavior of RES and compensate for their shortage.

A positive coefficient as a renewable energy scaling factor (RESF) is introduced to define the scale of RES compared to the base case. This factor is changed from 1 to 3, and the numerical results are shown in Fig. 13.

This sensitivity analysis shows that by increasing RESF, the operating costs of energy hub systems are significantly reduced in both autonomous and collaborative scheduling. This cost reduction is provided because clean energy resources do not consume any fuel for energy generation. According to Fig. 13, when the capacity of RES is doubled, the operating cost of the energy hub systems is reduced by 6.53% and changes from $ 1439 to $ 1345 in the collaborative mode. This cost reduction increases to 13.3% when capacity is tripled. In autonomous operation mode, the operating costs of the energy hub systems are reduced by 7.36% and 13.73% by doubling and tripling the capacity of RES, respectively.

To consider the impact of uncertain parameters, a stochastic approach is employed to handle the uncertainty associated with renewable generation and market prices. Seven scenarios are considered for each uncertain parameter. The beta, Weibull, and normal probability distribution functions are supposed to generate the solar, wind speed, and price scenarios, respectively23,24. The wind speed and solar radiation scenarios are shown in Figs. 14 and 15, respectively.

Table 7 presents the operating cost and energy not supplied in both autonomous and collaborative modes. It can be observed that the proposed collaborative model reduces the operating cost and unserved energy. The operating cost of the system in the autonomous mode is $ 1576.1, while the proposed collaborative mode reduces it by $ 228.87 and reaches $ 1347.23. Also, this cooperation reduces the unserved energy and increases the social welfare of MES. This improvement has been created because the neighboring MESs can share their surplus energy. Therefore, it reduces the shortage in all of MES.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a collaborative energy management for the integrated energy systems in distribution systems. The proposed model integrates various energy carriers, such as electricity, heat, hydrogen, cooling, and water, to present an efficient scheduling for the system. In the proposed structure, energy hubs can share their local resources to reduce their interaction with the electricity network and manage the uncertainty of RES. The compressed air energy storage and hydrogen systems have been developed to consume the surplus generation of wind energy and photovoltaic resources and generate electricity when it is needed. The simulation results show that the proposed cooperative model reduces the operating cost and energy not supplied by 1.63% and 100%, respectively. In future works, the application of machine learning approaches, such as the long short-term memory, will be studied on the generation of RES. Besides, an analytic approach will be discussed to determine the coalition formation between energy hub systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- t:

-

Index of times

- i:

-

Index of energy hubs

- \(L_{t}\) :

-

Electricity price

- \(\lambda_{t}\) :

-

Gas price

- \(OM_{CHP}\) :

-

Maintenance cost coefficient of CHP

- \(OM_{B}\) :

-

Maintenance cost coefficient of boiler

- \(PEN_{curt}\) :

-

Penalty of load curtailment

- \(LHV_{ }\) :

-

Low calorific value of natural gas

- \(\eta_{B}\) :

-

Efficiency of boiler

- \(G_{chp}^{max,i}\) :

-

Maximum imported natural gas of CHP

- \(G_{b}^{max,i}\) :

-

Maximum imported natural gas of boiler

- \(\eta_{es,c} /\eta_{es,d}\) :

-

Charging/discharging efficiency of ES

- \(E_{es}^{min,i} /E_{es}^{max,i}\) :

-

Minimum/maximum capacities of ES

- \(PH_{ac}^{max,i}\) :

-

Maximum input heat of AC

- \(COP_{ec} ,COP_{ice} ,COP_{ac}\) :

-

Performance coefficients of EC, CS, AC

- \(CO_{curt}\) :

-

Maximum curtailed load

- \(MR_{rp}^{h} /MR_{down}^{h}\) :

-

Maximum coefficient for up/down of heating load

- \(L^{w} /L^{G}\) :

-

Water well level / altitude of water storage location (m)

- \(Q_{ch}^{max} /Q_{dis}^{max}\) :

-

Maximum charge/discharge rate of water storage

- \(\eta^{elz} /\eta^{FC}\) :

-

Electrolyzer / fuel cell efficiency

- \(g/\rho\) :

-

Gravity / the density of water

- \(C_{H2}^{i,max} /C_{H2}^{i,min}\) :

-

Maximum / minimum capacity of hydrogen storage

- \(MR_{up}^{e} /MR_{down}^{e}\) :

-

Maximum coefficient for up/down of load

- \(P_{ec}^{max,i} /P_{ice}^{max,i}\) :

-

Maximum imported electricity to EC/CS

- \(\eta_{hs,c} /\eta_{hs,d}\) :

-

Charging/discharging efficiency of HS

- \(E_{hs}^{min,i} /E_{hs}^{max,i}\) :

-

Minimum/maximum capacities of HS

- \(\eta_{cs,c} /\eta_{cs,d}\) :

-

Charging/discharging efficiency of CS

- \(E_{cs}^{min,i} /E_{cs}^{max,i}\) :

-

Minimum/maximum capacities of CS

- \(Q_{D}^{max,i}\) :

-

Maximum capacity of water desalination unit

- \(P_{elz}^{i,max} /P_{elz}^{i,min}\) :

-

Maximum / minimum input power of electrolyzer

- \(P_{FC}^{i,max} /P_{FC}^{i,min}\) :

-

Maximum / minimum output power of fuel cell

- \(\alpha^{inj} /\alpha^{p}\) :

-

Imported/exported efficiency to/from CAES

- \(V_{max}^{p} /V_{min}^{p}\) :

-

Maximum /minimum energy exported to CAES

- \(G_{chp}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported gas to CHP units

- \(P_{up}^{e,i,t} /P_{down}^{e,i,t}\) :

-

Shift up/down of electrical load by DRP

- \(G_{b}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported gas from to boiler units

- \(PeCHP_{{\left( {i,t} \right)}} /PhCHP_{{\left( {i,t} \right)}}\) :

-

Output electrical and heat of CHP

- \(Ph_{b}^{i,t}\) :

-

Output heat power of boiler

- \(I_{down}^{h,i,t} /I_{up}^{h,i,t}\) :

-

Binary variable of down / up of heating DR

- \(E_{es}^{i,t} ,E_{hs}^{i,t} ,E_{cs}^{i,t}\) :

-

Stored energy in ES, HS, CS

- \(C_{ec}^{i,t} ,C_{ac}^{i,t} ,C_{csd}^{i,t}\) :

-

Cooling power of EC, AC, and CS

- \(K_{c}^{e,i,t} /K_{d}^{e,i,t}\) :

-

Binary variable of ES charging/discharging

- \(I_{up}^{e,i,t} /I_{down}^{e,i,t}\) :

-

Binary variable of down / up of electrical DR

- \(P_{ice}^{i,t} ,P_{ec}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported power to CS/EC

- \(P_{curt}^{e,i,t}\) :

-

Curtailed load

- \(P_{g}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported power from the main grid

- \(PH_{ac}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported heat to AC

- \(P_{elz}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported power to electrolyzer

- \(I_{FC}^{i,t} /I_{elz}^{i,t}\) :

-

Binary variables of fuel cell / electrolyzer

- \(P_{FC}^{i,t}\) :

-

Output power of fuel cell

- \(P_{es,c}^{i,t} /P_{es,d}^{i,t}\) :

-

Charging / discharging power of ES

- \(P_{cs,c}^{i,t}\) :

-

Cooling charging rate of CS

- \(P^{hl,i,t} /P^{el,i,t} /CL^{i,t} /Q_{L}^{i,t}\) :

-

Heating, electrical, cooling and water loads

- \(K_{c}^{h,i,t} /K_{d}^{h,i,t}\) :

-

Binary variable for HS charging/discharging constraint

- \(P_{hs,c}^{i,t} /P_{hs,d}^{i,t}\) :

-

Charging / discharging heat of HS

- \(P_{down}^{h,i,t} /P_{up}^{h,i,t}\) :

-

Shift up/down of heat load by DRP

- \(C_{H2}^{i,t}\) :

-

State of charge of hydrogen storage at hour t

- \(Q_{D}^{i,t} /Q_{W}^{i,t}\) :

-

Output water of desalination unit / water well

- \(H_{2industry}^{i,t}\) :

-

Input hydrogen of hydrogen-based industries

- \(Q_{ch}^{i,t} /Q_{dis}^{i,t}\) :

-

Charging / discharging water of water storage

- \(K_{c}^{c,i,t} /K_{d}^{c,i,t}\) :

-

Binary variable for CS charging/discharging constraint

- \(L_{s}^{i,t}\) :

-

Water level of water storage at hour t

- \(V_{inj}^{i,t} /V_{p}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported/exported energy to/from CAES

- \(P_{CAES}^{i,t} ,P_{c,s}^{i,t}\) :

-

Imported/exported power to/from CAES

- \(u_{inj}^{i,t} ,u_{p}^{i,t}\) :

-

Binary variables of imported and exported energy to the CAES

References

Anvari, S., Medina, A. & Merchán, R. P. and A C Hernández. Sustainable solar/biomass/energy storage hybridization for enhanced renewable energy integration in multi-generation systems: a comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 223, 115997 (2025).

Zhu, M. et al. Real-Time energy management of hydrogen energy Hub-Based industrial integrated energy distribution system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 61, 1 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Optimal dispatch for integrated energy system considering data-driven dynamic energy hubs and thermal dynamics of pipeline networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 15 (5), 4537–4549 (2024).

Wang, Y., Qiu, D., Sun, X., Bie, Z. & Strbac, G. Coordinating multi-energy microgrids for integrated energy system resilience: a multi-task learning approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy. 15 (2), 920–937 (2023).

Norouzi, S., Mirzaei, M. A., Zare, K., Shafie-khah, M. & Nazari-Heris, M. A Second-Order stochastic Dominance-based Risk-Averse strategy for Self-Scheduling of a virtual energy hub in multiple energy markets. IEEE Access (2024).

Mokaramian, E., Shayeghi, H., Sedaghati, F., Safari, A. & Haes Alhelou, H. A CVaR-Robust-based multi-objective optimization model for energy hub considering uncertainty and E-fuel energy storage in energy and reserve markets. IEEE Access. 9, 109447–109464 (2021).

Behbahani, M. R. Multi-objective operation of renewable multi-microgrids integrated with energy storage system considering power losses and harmonics. J. Energy Storage. 117, 116128 (2025).

Monemi, B. & Mahdieh, G. Optimal energy management of water-energy nexus in multi-carrier systems integrated with renewable sources. Power Control Data Process. Syst. 1, e718536 (2024).

Zhao, A. et al. Multi-day optimal operation of rural integrated energy systems with comfort and meteorological sensitivity considerations. Energy Build. 349, 116548 (2025).

Xiao, D., Deng, W., Liu, B., Huang, W. & Zhu, Z. Game-theoretic energy scheduling for community multi-energy system with electric vehicle aggregator leveraging quantum swarm intelligence. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 172, 111200 (2025).

Karimi, H. & Behbahani, M. R. Tri-layer optimization of coupled water–energy storage under renewable uncertainty. J. Energy Storage. 137, 118540 (2025).

Al-Hassanawy, A. J. K., Kadhim, A. J., Zare, K., Ghassemzadeh, S. & Nzari-Heris, M. Robust coordination of electricity and gas networks integrated with energy Hubs, rooftop solar Homes, and responsive loads. IEEE Access 12, 856 (2024).

Abedinia, O., Shorki, A., Nurmanova, V. & Bagheri, M. Synergizing efficient optimal energy hub design for multiple smart energy system players and electric vehicles. IEEE Access 11, 256 (2023).

Abdulnasser, G., Ali, A., Shaaban, M. F. & Mohamed, E. Optimizing the operation and coordination of multi-carrier energy systems in smart microgrids using a stochastic approach. IEEE Access. 11, 58470–58490 (2023).

Jiang, M. et al. Estimation of operation cost of residential multiple energy system considering uncertainty of loads and renewable energies. IEEE Access. 9, 4874–4885 (2020).

Tavakoli, A., Karimi, A. & Shafie-Khah, M. Linearized stochastic optimization framework for day-ahead scheduling of a biogas-based energy hub under uncertainty. IEEE Access. 9, 136045–136059 (2021).

Karimi, H. & Jadid, S. Sustainable and reliability based coalition forming model for smart multi-microgrid systems considering battery and water storage systems. J. Energy Storage. 102, 114050 (2024).

Farazmand, M., Saadat, Z. & Sameti, M. Above-ground hydrogen storage: a state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 90, 1173–1205 (2024).

Sameti, M., Mulcair, E. & Syron, E. Green hydrogen production and storage at wind farms: an economic and environmental optimisation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 120, 572–583 (2025).

Ahhmadi, S. & Nazar, M. S. Economic operation of multi-carrier microgrids considering energy markets and renewable electricity production. Power Control Data Process. Syst. 2, e724620 (2025).

Barati, A. et al. Multi-objective operation of interconnected multi-energy systems considering power to gas and gas to power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 158, 109986 (2024).

Rashidinejad, M., Dorahaki, S. & Zadsar, S. S. Robust scheduling of water and energy hub considering CAES, power-to-gas units, and demand response programs. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Innov. 10 (2), 371–380 (2022).

Azizivahed, A. et al. Stochastic scheduling of energy sharing in reconfigurable multi-microgrid systems in the presence of vehicle-to-grid technology. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 231, 110285 (2024).

Jain, T. & Verma, K. Reliability based computational model for stochastic unit commitment of a bulk power system integrated with volatile wind power. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 244, 109949 (2024).

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, and draft manuscript preparation: Saina Foroughian, Zohreh Aghaie Joki Bijan, Hamid Karimi, and Saeed Hasanzadeh. All the authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. If you have any questions or need data, please contact the corresponding author: Saeed Hasanzadeh, email: hasanzadeh@qut.ac.ir.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foroughian, S., Bijan, Z.A.J., Karimi, H. et al. Optimal operation of multi-carrier energy systems integrated with renewable energy sources and hydrogen storage systems. Sci Rep 16, 6635 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35497-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35497-3