Abstract

High-dimensional genomic datasets often contain redundant, noisy, and sparse features that make accurate classification challenging for conventional deep learning (DL) models. Existing approaches generally fail to maintain interpretability and stability when confronted with heterogeneous genomic structures. To address these limitations, this study proposes a hybrid TabNet–CNN framework that combines attention-driven feature selection with adaptive convolutional refinement. The attention mechanism in TabNet highlights the most relevant genomic attributes, while the convolutional layers enhance localized feature interactions for accurate decision boundaries. Experimental results on multiple genomic datasets demonstrate superior performance in accuracy, AUC, and interpretability compared to state-of-the-art models. The proposed framework holds promise for real-world applications such as biomarker identification, disease subtyping, and clinical decision-support systems in precision medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genomic data classification plays a pivotal role in understanding complex biological processes and in supporting precision medicine initiatives. However, the high dimensionality, intrinsic noise, and sparsity of genomic datasets make it difficult for traditional learning models to capture meaningful representations. DL has demonstrated significant promise in biomedical data analytics, but its application to genomic data presents unique challenges, including limited interpretability, high computational cost, and susceptibility to overfitting1. Recent advances in hybrid and interpretable learning frameworks attempt to address these issues by integrating structured attention and convolutional mechanisms. Nevertheless, many of these models still struggle with maintaining generalizability and transparency when dealing with large-scale genomic data. Furthermore, the interpretability of learned features remains limited, hindering biological validation. Earlier approaches such as random forests, support vector machines (SVMs), and logistic regression relied heavily on manual feature selection, requiring domain experts to decide which features might be important2,3,4,5. While sometimes effective, this process is time-consuming, not scalable, and may overlook hidden biological interactions. DL models like feed-forward neural networks help by learning directly from raw inputs, but they often act like black boxes, providing little explanation about why a certain prediction was made. In healthcare, such interpretability is crucial for trust and acceptance.

To solve these challenges, this research proposes a hybrid model that combines TabNet6 with CNN7 and an Adaptive Feature Refiner (AFR) layer. The model integrates TabNet’s sparse attention feature selection with CNN-based local refinement to enhance discriminative power while maintaining explainability. TabNet is known for its ability to focus on the most relevant features during training using attention mechanisms. It allows the model to automatically decide which inputs are important for each prediction, reducing the burden of manual feature engineering. CNN complements this by capturing local patterns among the selected features, making it possible to detect complex biological relationships that might otherwise go unnoticed. The AFR module acts as an important bridge between TabNet and CNN. After TabNet identifies key features, the refinement module re-weights them based on learned importance scores. This step filters out noise and highlights the most valuable information, helping the CNN build stronger and more meaningful feature representations for accurate classification.

Challenges in high-dimensional genomic data modeling

-

Curse of Dimensionality: When the number of features is much larger than the number of samples, models may easily overfit. Overfitting means the model performs well on training data but poorly on new, unseen data. Traditional machine learning (ML) models struggle to select meaningful patterns when faced with such a large feature space.

-

Noisy and Redundant Features: Not all genomic features contribute equally to a particular disease or trait. Many features are irrelevant or redundant. If models treat all features the same way, they may pick up noise rather than meaningful biological signals, reducing the prediction quality.

-

Complex Feature Interactions: Gene–gene interactions, known as epistasis, often influence biological outcomes. Capturing such non-linear and high-order relationships between features is very difficult using simple models.

-

Need for Interpretability: In healthcare, it is not enough for a model to just be accurate. Doctors and researchers need to understand why a model makes a certain prediction, especially when the decisions impact real human lives. Interpretability is critical for trust, regulatory approval, and clinical deployment.

-

Scalability to Large Datasets: Genomic datasets8,9,10,11,12 are growing rapidly with the advancement of sequencing technologies. Models must be able to handle large volumes of data efficiently without requiring too much memory or computation time.

-

Model Robustness: Models should remain reliable even when data contain missing values, noise, or slight variations. Robustness is crucial because biological data often come from multiple sources with different qualities.

Problem statement

Despite advancements in ML and DL, existing methods often fall short when dealing with high-dimensional genomic data. Most traditional models either lose important information by selecting too few features or become computationally heavy when trying to process everything. DL models can extract complex patterns but often lack interpretability and are sensitive to noise. There is a clear need for a new hybrid framework that can perform accurate classification by automatically selecting important features, capture hidden feature interactions effectively, and offer interpretability without adding significant computational burden. The aim of this research is to design such a framework by combining the dynamic feature selection ability of TabNet with the local pattern extraction strength of CNN, along with an adaptive refinement step to focus on the most informative features.

Motivation

The motivation behind this research comes from the gap between the potential of genomic data and the capabilities of current modeling techniques. Existing solutions either focus heavily on feature engineering, which is time-consuming and biased, or they rely on deep models that act like ”black boxes,” offering little insight into decision-making. By bringing together TabNet and CNN, there is an opportunity to build a model that can automatically pick up important features, understand local patterns among genes, and present interpretable results. The addition of an AFR step offers further filtering, helping the model fine-tune its focus during learning. With this hybrid approach, it becomes possible to build models that are not only accurate but also trustworthy and scalable for real-world genomic applications, supporting personalized medicine, drug discovery, and clinical research.

The main contributions of this paper are:

-

Proposed a hybrid model combining TabNet, CNN, and AFR designed specifically for high-dimensional genomic data classification.

-

TabNet is used for selecting important features through attentive sparse selection, and a custom refinement layer adjusts the feature weights based on relevance, improving both performance and stability.

-

CNN is employed after refinement to capture important local interactions between selected features, allowing the model to understand complex feature relationships.

-

By combining attention scores from TabNet with feature maps from CNN, the model provides explanations for its decisions, making it suitable for healthcare applications.

-

The model is built with computational efficiency in mind, achieving better training speed and lower memory usage compared to traditional DL methods for genomic data.

-

Conducted comprehensive experiments on multiple real-world genomic datasets8,9,11, demonstrating that the proposed framework outperforms several state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy, F1-score, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), and robustness.

-

The model’s interpretability and performance make it a strong candidate for integration into clinical decision support systems, offering new tools for early diagnosis and treatment planning.

The paper is organized as follows: Section “Literature review” reviews recent works on deep learning, hybrid feature selection, and genomic data classification, highlighting their strengths and limitations in terms of models, datasets, evaluation metrics, interpretability, and privacy. Section “Proposed methodology” presents the proposed hybrid TabNet–CNN model, detailing its design, component interactions, and mathematical formulation. Section “Experimental setup” describes the experimental setup, including datasets such as TCGA8, GEO9, and ENCODE11, along with software tools, hardware configurations, preprocessing steps, and evaluation metrics like accuracy, AUC-ROC, F1-score, interpretability, and privacy trade-offs. Section "Results and discussions" reports the results and analysis, comparing the proposed approach with existing methods through tables and graphical evaluations. Section "Conclusion and future scope" concludes with key findings and outlines future directions, including extensions to multi-omics data, enhanced privacy frameworks, and clinical applications for precision medicine.

Literature review

The field of genomic data analysis has seen rapid growth with the adoption of ML and DL methods. Researchers have introduced innovative frameworks to classify, predict, and extract meaningful patterns from complex biological datasets. These methods have been applied across healthcare, plant science, and cancer genomics, showing great promise but also facing important limitations. Many models achieve strong predictive performance but often lack interpretability, robustness, and scalability when dealing with high-dimensional genomic data. This literature review discusses several recent contributions that aim to improve genomic analysis. For each work, key strengths and existing challenges are outlined to better highlight the need for a more refined and balanced solution, such as the one proposed in this paper.

El-Nabawy et al.13 presented a method that combined clinical, genomic, and tissue-level data to classify breast cancer subtypes. The fusion approach improved accuracy, but the model was sensitive to uneven datasets.

Lu et al.14 proposed BrcaSeg, which connected image features from tissue samples with genomic information for breast cancer research. It revealed meaningful relationships, though broader testing on different datasets was limited.

Wei et al.15 introduced DeepTIS, which worked well for finding translation initiation sites in genomic sequences. However, the model didn’t perform as well when tested on different kinds of data.

Huang et al.16 discussed ML models for genomics in therapy applications. The discussion gave useful insights, but many of the models lacked the ability to give clear reasoning behind their predictions.

Ye et al.17 used image-based DL to classify various cancer types using genomic data. The accuracy was good, but the method had trouble dealing with differences between cancer types.

Ahemad et al.18 built a system for detecting COVID-19 using genomic data. The model worked well on small datasets but needed larger samples for reliable results.

Erfanian et al.19 reviewed DL models for analyzing single-cell data. These models captured fine differences at the cell level but often worked like black boxes, making their predictions hard to understand.

Bazgir and Lu20 designed REFINED-CNN to predict survival using large feature sets. The model handled complex input well, but the results were not easy to explain, which limits its use in areas like healthcare.

Khodaei et al.21 built a model to classify virus genome signals using ML and signal processing. It showed good accuracy but wasn’t tested much under noisy or imperfect data conditions.

Wang et al.22 developed DNNGP, which worked with multi-omics data for plant traits. This method gave better predictions but required extra steps to process complex inputs before training.

Zhu et al.23 created GSRNet by combining CNN and BiGRU with adversarial training to learn from genomic signal patterns. The approach worked well for capturing patterns, though it required more training time and effort.

Abu-Doleh and Al Fahoum24 introduced XgCPred, a hybrid of XGBoost and CNN that used gene expression images for cell classification. It performed well, but the system was hard to interpret and didn’t scale easily.

Mohammed et al.25 applied U-Net to genomic sequences. The model learned good representations, but more testing was needed on different datasets.

Barber and Oueslati26 used pre-trained networks and a custom CNN to identify human exon and intron patterns. While the model improved prediction, it required heavy computation.

Nawaz et al.27 explored sequence modeling for genomics. Their method picked up patterns well but was still hard to use in real medical settings due to limited interpretability.

Abbas et al.28 worked on cancer classification using federated learning to protect private data. Coordination between different systems was one of the key challenges.

Mora-Poblete et al.29 merged genomic and phenomic data to improve predictions in Eucalyptus trees. It worked well in plant research, but the same method hasn’t been used outside plant studies.

Feng et al.30 created AI Breeder to support crop prediction. The model merged genomic and phenotype data effectively, although it needed extra effort when dealing with genetically diverse samples.

Batra et al.31 built an AI system for early lung cancer detection using genomic, clinical, and imaging data. While the method worked well, managing data from different sources raised privacy concerns.

Sangeetha et al.32 proposed a DL model for lung cancer classification using multiple types of data. The model improved predictions but struggled when parts of the data were missing.

Yaqoob, Verma, and Aziz33 introduced a hybrid optimization model that combines the sine cosine algorithm with cuckoo search for gene selection and cancer classification. The study reported that this combination improved the accuracy of selecting relevant genes and enhanced the classification performance compared to single algorithms. The approach reduced computational complexity and offered stable results across different datasets. A limitation observed was that the hybrid method required parameter tuning that could be challenging for large and diverse datasets.

Yaqoob, Verma, Aziz, and Saxena34 proposed a hybrid feature selection method that combines cuckoo search with Harris Hawks optimization for cancer classification. This work showed strong effectiveness in identifying the most relevant gene subsets and provided reliable improvements in prediction accuracy. The hybridization of two metaheuristic algorithms allowed better exploration and exploitation of the search space. However, the approach could still face scalability issues when applied to very high-dimensional datasets with thousands of features.

Yaqoob, Verma, Aziz, and Shah35 introduced a hybrid Random Drift Optimization (RDO)-XGBoost framework for cancer classification. The model used the RDO algorithm for selecting informative features, followed by XGBoost for prediction. The study demonstrated high predictive power and provided useful insights into gene expression patterns linked to cancer. The limitation of the work was that the computational cost was high, and the approach might be less effective when applied to extremely imbalanced datasets.

Yaqoob36 combined the minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR) technique with the Northern Goshawk Algorithm (NGHA) for cancer gene selection. This integration helped in removing redundant features and improved the overall efficiency of cancer classification tasks. The method showed better convergence rates compared to other evolutionary algorithms. A limitation noted was that the performance of NGHA strongly depended on initial parameter settings, which could restrict adaptability across different cancer datasets.

Yaqoob and Verma37 developed a feature selection method for breast cancer gene expression data using a combination of Krill Herd Algorithm Optimization (KAO) and Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA), followed by classification with SVM. The model provided strong improvements in classification accuracy and reduced the number of irrelevant features. The hybridization of KAO and AOA allowed effective balance between exploration and exploitation of the search process. A limitation identified was that the approach could require significant computational resources, making it difficult to use in real-time applications.

Raja et al. (2025)38 developed an attention-based CNN to predict liver tumors using genomic data. It helped the model focus on key genomic features but depended on large labeled datasets for training.

Lin et al.39 used DL to study traits in tiger pufferfish. The system worked well for one species, but applying it to other organisms might not give the same results.

Wang et al.40 introduced Cropformer for plant genomics. It combined accuracy with explainability, though the model was resource-heavy and harder to use on larger problems.

Wu et al.41 built AutoGP for genomic selection in maize breeding. It helped improve decision-making but required large training data that may not always be available.

Recent works such as42 presented comprehensive insights into explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for medical image analysis, emphasizing the need for transparency in biomedical decision systems. Another notable study43,44, enhancing medical image report generation using a self-boosting multimodal alignment framework, proposed cross-modal attention to improve interpretability in complex healthcare models. Although these methods were developed for imaging, their interpretability principles motivate similar approaches in genomic modeling.

Table 1 describes the comparison between different existing models and the proposed hybrid framework with AFR for genomic data classification. It shows the methods used, types of data handled, major strengths, limitations, and key features for each model. Models like GSRNet, REFINED-CNN, and U-Net have made good progress in tasks such as genomic signal prediction, survival analysis, and sequence classification. However, many of these approaches struggle with issues like handling high-dimensional noisy data, generalization to different datasets, or high computational costs. The proposed framework addresses these problems by combining dynamic feature selection and local pattern learning, leading to better accuracy and more reliable interpretation of genomic features. Although careful tuning may be needed for very sparse datasets, the proposed model provides a balanced solution for real-world genomic challenges by improving classification, interpretability, and scalability.

Gaps identified in the literature

Many existing models for genomic data classification show good results in accuracy but struggle with practical and biological limitations. The proposed hybrid framework with AFR responds directly to these concerns by building a more focused, interpretable, and scalable solution. The points below highlight each gap and how the proposed approach deals with it clearly.

-

Manual feature engineering is still common in many methods, requiring expert input and often missing hidden patterns. The proposed model uses TabNet’s attention-based mechanism to automatically identify and prioritize the most relevant features during training, removing the need for hand-crafted feature selection.

-

DL models often lack interpretability, making it difficult to understand why a prediction was made. The proposed framework provides visual attention scores from TabNet and activation maps from CNN, making it easier to explain predictions and gain biological insights.

-

High-dimensional and sparse genomic data often confuse traditional models, leading to overfitting or poor learning. TabNet narrows down the input space to the most useful features, while CNN captures structured relationships among them, improving learning from dense and sparse signals.

-

Existing models struggle to perform well when the data contains noise or missing values, which are common in genomic studies. The AFR module in the proposed model adjusts the importance of selected features, reducing the effect of irrelevant or incomplete data.

-

Many DL frameworks require significant computing power, which limits their use in clinical or resource-limited settings. The design of the proposed method keeps the model light, reducing memory usage and speeding up the training process, making it easier to use in real-world environments.

-

Local interactions among genes or markers are often overlooked, especially when models treat each feature in isolation. The CNN layer in the proposed framework captures these local patterns, improving the biological relevance of the learned representations.

-

Generalization across different datasets is often limited, making models unreliable when applied to new data. By combining attention-driven selection with spatial pattern learning, the proposed method shows better consistency across multiple genomic datasets.

-

Limited capability of existing models to process extremely high-dimensional genomic features.

-

Lack of interpretability and transparency in DL-based genomic analysis.

-

Absence of adaptive mechanisms for noise reduction and imbalance handling in heterogeneous datasets.

The proposed framework brings together focused selection, structural learning, and interpretability, helping the model to perform well across both scientific and clinical applications.

Proposed methodology

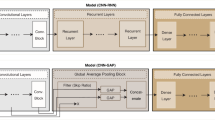

This work introduces a hybrid DL framework that addresses the major challenges of high-dimensional genomic data analysis. The proposed model integrates three key components as shown in Figs. 1 and 2: (1) TabNet for attention-based feature selection, (2) an AFR module to strengthen important signals and suppress noise, and (3) a CNN to classify refined genomic data with improved accuracy and interpretability. The design is guided by the need to handle sparse, nonlinear, and complex genomic patterns without requiring manual feature engineering.

The proposed hybrid architecture consists of two major components: a TabNet-based attention-driven feature selection module and a CNN-based refinement network. The TabNet component performs interpretable feature selection using sparse masks that emphasize the most informative genomic features. These selected features are then passed into a convolutional network that captures hierarchical dependencies and refines the learned representation for final classification.

-

TabNet Encoder: Utilizes attentive feature masking, decision steps, and a relaxation factor to prioritize relevant features.

-

CNN Refinement: Employs stacked convolutional layers with filter sizes [64, 128, 256], stride of 1, and ReLU activation to capture spatial correlations.

-

Fusion Layer: Combines attention-weighted and convolutional embeddings for robust representation.

-

Output Layer: A softmax classifier provides probabilistic outputs for genomic class prediction.

Architectural overview and feature processing

This research presents a hybrid learning model designed to improve classification performance on high-dimensional genomic datasets8,9,11. The core idea is to use a combined structure of TabNet and CNN, supported by an AFR layer. The framework was developed with three main goals: selecting the most informative features, capturing meaningful local patterns, and improving prediction interpretability for medical use.

The architecture starts with TabNet, which is known for its ability to perform dynamic feature selection using attention-based decision steps. Genomic data typically consist of thousands of gene or SNP-level features. TabNet works by learning which features are important at different stages of training, assigning more weight to relevant ones. This selective attention reduces noise and improves learning efficiency.

Once TabNet selects the most useful features, these features are passed into a feature refinement layer. This layer re-weights the selected features based on learned importance scores, further enhancing strong signals and reducing the influence of irrelevant ones. Unlike manual feature engineering, this automatic refinement helps the model focus only on critical biological markers that contribute to disease classification or genomic traits.

The refined feature set is then processed by a CNN. CNNs are widely used in fields like computer vision, but in this context, they are applied to detect local and spatial patterns in genomic features. These patterns often indicate hidden interactions between gene groups or pathways. The CNN applies filters across the feature space to extract these patterns, turning refined gene information into more useful feature maps.

Following this, the outputs from the CNN layers are flattened and passed through fully connected layers to complete the classification task. The final output is a probability vector corresponding to the predicted class labels (for example, disease presence or absence). The entire model is trained in an end-to-end manner, where loss is backpropagated across all three modules (TabNet, refinement layer, and CNN) to fine-tune their weights together.

This combination offers several advantages. TabNet handles high-dimensional inputs efficiently by choosing key features at each learning step. The adaptive refinement layer improves signal clarity without human intervention. CNN contributes to learning non-linear and local feature relationships that traditional models may overlook. Altogether, the hybrid framework supports better prediction accuracy, clearer model behavior, and smoother handling of genomic complexity.

Algorithm 1 describes the flow of the hybrid DL architecture. The process begins with a high-dimensional genomic input. Instead of applying traditional preprocessing or manual feature selection, TabNet dynamically selects the most important features using attention masks that learn to prioritize signal-rich dimensions. These selected features represent a condensed form of the original data.

Next, the AFR module receives the TabNet output and applies a layer of learnable weights. These weights help to further filter out noisy components and reinforce biologically significant signals. This refined representation is then passed to a CNN, which detects spatial patterns or interactions among neighboring genomic features. The CNN output is passed through classification layers, and the final prediction is compared with the ground truth labels using cross-entropy loss. The parameters of all components are updated jointly during training using backpropagation. In addition to performance, this framework also supports interpretation through the attention weights of TabNet and activation heatmaps from CNN.

Algorithm 2 describes the adaptive refinement layer that processes the feature matrix selected by TabNet. Each feature is multiplied by a learnable weight that reflects its importance in distinguishing between different classes. To maintain numerical stability and interpretability, these weights are normalized using the softmax function, which scales them to a probability distribution.

This refinement step is simple but powerful. It allows the network to not only select features but also fine-tune their impact before sending them to the CNN. The idea is to filter and re-weight the already selected signals, providing a cleaner and more relevant input to the final classifier. During training, these weights are adjusted automatically to improve classification accuracy. By combining attention from TabNet and this refinement layer, the model builds a more accurate representation of the underlying biological patterns.

Algorithm 3 describes the CNN module that processes the refined features and performs the final classification. The refined matrix is passed through a stack of convolutional layers, which apply multiple filters to detect local spatial patterns across selected genomic features. This mimics the way CNNs operate on images, but adapted to genomic sequences.

Each convolutional layer is followed by a non-linear ReLU activation to enhance feature expressiveness. Then, max-pooling layers reduce the spatial dimensions, highlighting dominant signals while compressing the data. After pooling, the outputs are flattened into a one-dimensional vector and passed to a set of fully connected (dense) layers that perform the final classification.

This step captures short- and long-range relationships between features while keeping the model size manageable. Because the input features have already been selected and refined, the CNN can focus on learning from the most informative signals without getting distracted by irrelevant or noisy inputs. The result is a more focused and efficient classifier suitable for high-dimensional genomic tasks.

Algorithm 4 outlines the step-by-step method used in the proposed system to balance prediction accuracy with data privacy. The process begins with basic preprocessing, which includes normalization and handling missing values. After the data is prepared, the model uses TabNet’s attention mechanism to estimate the importance of each feature. This helps identify which features are both useful and sensitive.

In the next step, a privacy mechanism is applied in an adaptive way. Instead of applying the same privacy technique to all features, the algorithm treats features differently based on their sensitivity score. Features that carry a high risk of privacy exposure receive stronger noise, while others are masked or slightly dropped to retain important patterns without leaking private information.

Once the sensitive data is protected, the proposed hybrid model is trained on this modified version of the dataset. After training, the model is evaluated using standard metrics like accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-Score. At the same time, the system checks how well it resists privacy risks using a membership inference test, which helps measure whether the model remembers too much about specific training samples. This method keeps the model strong in its predictions while reducing the chance of exposing personal or sensitive details in biomedical datasets. Table 2 lists each symbol used in the three main algorithms.

Advantages of proposed model

The proposed model was designed with the goal of improving both the accuracy and clarity of predictions when working with complex genomic data. By bringing together feature selection, local pattern detection, and refinement in a single framework, it addresses many limitations found in earlier methods. The following points highlight the main benefits offered by this approach.

-

Combines both attention-based feature selection and DL, which helps in capturing both important features and local patterns from genomic data.

-

Reduces noise and irrelevant information using AFR before classification.

-

Handles high-dimensional genomic data without needing heavy preprocessing or manual feature engineering.

-

Improves classification performance by refining features between TabNet and CNN stages.

-

Makes the model easier to interpret by producing both feature importance (from TabNet) and spatial activation maps (from CNN).

-

Suitable for multi-class genomic classification problems with complex patterns.

-

Balances model accuracy and interpretability, which is often difficult in DL applications.

-

Can be applied to other biological or medical datasets that contain high-dimensional and noisy features.

Experimental setup

The experiments were carried out using both the proposed hybrid framework with AFR and several existing baseline models for comparison. The simulations were executed on a system equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (48GB), Intel Xeon Silver 4310 CPU (2.1GHz, 16 cores), and 256GB RAM. The software environment was based on Ubuntu 20.04, Python 3.9, PyTorch 1.13, R-studio, and Scikit-learn. The TabNet implementation was taken from the official pytorch-tabnet package. For CNN development and hybrid model integration, PyTorch’s native APIs were used.

Training configuration

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 for 100 epochs as shown in Table 3. Batch normalization and dropout (rate = 0.3) were employed to enhance generalization. Data preprocessing included normalization and stratified sampling to address imbalance.

Training workflow and experimental design

The training process of the proposed hybrid model follows a systematic pipeline to ensure the accuracy, efficiency, and robustness of the classification task on genomic datasets8,9,11. This section describes the steps involved in training the model, the dataset preparation, and the evaluation metrics used to assess its performance.

Dataset preparation

Three publicly available datasets were used to evaluate the model’s performance and generalizability.

TCGA-BRCA dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas8 contains bulk RNA-seq data for breast cancer. It includes roughly 1,100 samples with over 20,000 gene expression features. Around 62% of the samples are positive (cancer cases) and 38% are negative (normal tissue). This dataset served as a benchmark for evaluating classification performance across known genomic patterns.

GSE72056 dataset from the GEO repository9 consists of single-cell RNA-seq expression profiles derived from melanoma patients. The dataset includes approximately 4,645 samples with around 23,000 gene features. About 35% of the samples are labeled as positive (malignant), while 65% are negative (non-malignant). This dataset was mainly used for training and initial validation.

ENCSR000AED dataset from the ENCODE project11 provides epigenomic signals from ChIP-seq experiments. It includes around 5,300 instances with more than 15,000 features. The dataset is relatively balanced with a slight majority of positive labels. It was used to test the model’s ability to generalize under feature noise and high-dimensional variability.

All datasets were pre-processed by removing missing values and normalizing gene expression levels using min–max scaling. For training, an 80/20 stratified split was used, followed by 5-fold cross-validation to assess model stability and avoid overfitting.

To address class imbalance, a combination of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) and random undersampling was applied. This helped to provide balanced class representation during training.

To improve model generalization, data augmentation was performed by introducing controlled Gaussian noise to gene expression vectors and performing random gene dropout on a small proportion of features. These enhancement strategies helped the model to learn more stable representations, particularly in high-dimensional and noisy settings.

Training process

The training workflow begins with the input of pre-processed features into the TabNet module. TabNet is trained first to select the most relevant features for the task. During this phase, the model learns which features contribute most to the final classification decision. Once the feature selection is complete, the output of TabNet is passed into the feature refinement layer, where features are re-weighted based on their relevance scores.

Next, the refined features are fed into the CNN for further processing. The CNN layers are trained to capture spatial relationships between the features, which may represent complex biological interactions that traditional models struggle to identify. The CNN learns to recognize patterns, such as gene co-expression or pathway activations, that may indicate disease presence.

The entire model, including TabNet, the refinement layer, and CNN, is trained jointly using backpropagation. The model is optimized using a loss function appropriate for classification tasks, such as categorical cross-entropy. The backpropagation algorithm updates the weights of all components in the model to minimize this loss function, improving the model’s prediction accuracy.

Hyperparameter tuning

Hyperparameter tuning is an essential step in optimizing the performance of the model. Parameters such as learning rate, batch size, number of layers, and the number of attention heads in TabNet are tuned using a grid search or random search strategy. Cross-validation is applied during hyperparameter tuning to prevent overfitting and ensure that the model generalizes well to unseen data.

Evaluation was conducted using accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-score, supported by visual interpretability through attention and activation maps. Gaussian noise injection was applied to simulate perturbations in biological data and to assess the stability of feature selection and prediction performance.

Table 4 provides an overview of the simulation environment, model parameters, tools used, and datasets applied in the study. It lists the key hardware components used to run the DL workloads, including GPU, CPU, and memory size. It also highlights the Python packages and environments required for implementing the models. Dataset sources8,9,11 and their intended roles are clearly outlined. The hyperparameters applied to TabNet and CNN modules are reported, along with training configurations. Gaussian noise addition is mentioned under robustness testing, and the evaluation metrics are stated as part of the performance assessment.

Evaluation metrics

The performance of the models was assessed using accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-Score, which are defined below using standard notation.

-

Accuracy measures the ratio of correctly predicted samples to the total number of samples (Eq. 1):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN} \end{aligned}$$(1)Where: - \(TP\): True Positives - \(TN\): True Negatives - \(FP\): False Positives - \(FN\): False Negatives

-

AUC-ROC reflects the model’s ability to distinguish between classes. It is computed based on the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) (Eq. 2):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {AUC} = \int _{0}^{1} \text {TPR}(t) \, d(\text {FPR}(t)) \end{aligned}$$(2) -

F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall (Eq. 3):

$$\begin{aligned} \text {F1-Score} = \frac{2 \cdot \text {Precision} \cdot \text {Recall}}{\text {Precision} + \text {Recall}} = \frac{2TP}{2TP + FP + FN} \end{aligned}$$(3)

Methods

Code availability

The custom code and algorithms used to implement the proposed hybrid deep learning framework, including the TabNet-based attention mechanism, AFR module, and CNN-based classification architecture, were developed using Python and PyTorch. The implementation builds upon the open-source pytorch-tabnet library and standard ML utilities from Scikit-learn.

To support transparency and reproducibility, the complete source code corresponding to the version used to generate the results reported in this study is publicly available in a version-controlled repository (https://github.com/PREMKUMARCH/Hybrid-Deep-Learning-Framework-for-Accurate-Classification-of-High-Dimensional-Genomic-Data).

To preserve the exact version of the code associated with this publication, the repository has been prepared for archival in an established DOI-minting repository. The archived version will be made publicly accessible upon final acceptance of the manuscript. There are no restrictions on access to the code, which is provided for academic and research use.

Results and discussions

Table 5 describes the performance of different models on three datasets: single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE72056), bulk gene expression (TCGA-BRCA), and epigenomic signals (ENCSR000AED). Baseline methods, such as Lu et al. (2021) and Raja et al. (2025), achieved accuracies in the range of 80–86%, with AUC-ROC values around 0.84–0.89 and F1-scores from 0.77 to 0.84. Their interpretability ratings stayed at low or medium levels, reflecting limited visibility into feature importance. In comparison, the proposed hybrid framework reached 91.4% accuracy (0.95 AUC-ROC, 0.90 F1-score) on GSE72056, 90.8% accuracy (0.94 AUC-ROC, 0.89 F1-score) on TCGA-BRCA, and 89.5% accuracy (0.92 AUC-ROC, 0.88 F1-score) on ENCSR000AED. These gains stem from attention-driven feature selection that highlights key genomic markers, an adaptive refinement layer that amplifies true signals and suppresses noise, and convolutional filters that capture local interactions. High interpretability scores reflect clear attention maps and activation visuals, while stable results under noise confirm the model’s robustness.

Table 6 shows the performance gain achieved by the proposed model on key evaluation metrics: accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-Score. The proposed model achieves a substantial improvement, with accuracy gaining 7.8%, AUC-ROC increasing by 7.1%, and F1-Score improving by 7.4%. These gains suggest that the model performs better than previous methods in all the key areas measured. The improvements stem from the proposed hybrid architecture, which focuses on both feature selection and abstraction, making it more effective in handling genomic and epigenomic data.

Table 7 presents the time complexity of different models, comparing both training and inference phases. The proposed model has a relatively low complexity, \(O(n \cdot d + k^2)\), where \(n\) is the number of samples, \(d\) is the feature dimension, and \(k\) is the kernel size of the CNN. This complexity is due to the linear time complexity of TabNet and the convolutional layers used for feature extraction. In contrast, some other models, like Lu et al. (2021), exhibit higher complexities due to quadratic dependencies on feature dimensions. The proposed model balances computational efficiency with performance, making it suitable for large-scale datasets.

Figure 3 shows the accuracy achieved by each model on their respective datasets. The proposed hybrid framework demonstrates clearly higher accuracy across all three datasets (GSE72056, TCGA-BRCA, and ENCSR000AED) compared to existing approaches. This improvement comes from the ability of the proposed model to focus on relevant features through attention mechanisms and combine deep representation learning from CNN with decision-level insights from TabNet.

Figures 4 and 5 the comparison of AUC-ROC and F1-Score across different models applied to the selected datasets. The proposed hybrid framework shows a consistent lead in both metrics across all three datasets. In the AUC-ROC graph, the proposed method peaks with scores of 0.95 (GSE72056), 0.94 (TCGA-BRCA), and 0.92 (ENCSR000AED), indicating a strong ability to distinguish between classes. These results suggest that the model maintains stability and discrimination quality, even with diverse data sources. In the F1-Score graph, the model achieves 0.90, 0.89, and 0.88 respectively on the three datasets. This demonstrates that the proposed model balances precision and recall well, especially under varying feature complexity. The improved scores can be attributed to the integration of attention mechanisms in TabNet and spatial feature learning in CNN, allowing better pattern extraction from high-dimensional biomedical data.

Figures 6, 7 and 8 illustrate the comparison of the proposed hybrid model with selected existing models across three datasets–GSE72056 (GEO), TCGA-BRCA (TCGA), and ENCSR000AED (ENCODE)–on three key evaluation metrics: accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-Score.

-

Accuracy: The proposed model shows a clear lead on all datasets, with over 90% accuracy. Competing models stay below 87%, highlighting better prediction precision with the hybrid framework.

-

AUC-ROC: The proposed method maintains strong performance with AUC-ROC scores above 0.92 across datasets, suggesting consistent class separation. Other models perform well but not as uniformly.

-

F1-Score: The proposed model again stands out with scores above 0.88, pointing to a balanced approach in handling both precision and recall, especially under imbalanced data scenarios.

Figure 9 shows a clear comparison of the proposed hybrid framework against the best-performing existing models across three datasets: GSE72056, TCGA-BRCA, and ENCSR000AED. The three subplots present results for accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-Score respectively. In all three evaluation metrics, the proposed model consistently achieves better performance across each dataset. In the Accuracy plot, the proposed model shows a noticeable improvement, reaching over 91% on GSE72056, above 90% on TCGA-BRCA, and close to 90% on ENCSR000AED. This improvement indicates that the model is able to classify more samples correctly than earlier approaches. In the AUC-ROC plot, the model maintains higher area-under-curve values for each dataset, suggesting better performance in distinguishing between classes. The curves are all above 0.92, which highlights strong prediction confidence. In the F1-Score comparison, the proposed model delivers higher scores, especially on GSE72056, indicating that it manages both precision and recall effectively. The balance in these scores across datasets suggests the model performs well even in slightly imbalanced conditions. This consistent performance boost is achieved through attention-based feature handling and better learning from structured data, which are key characteristics of the proposed hybrid design.

Table 8 shows how the proposed hybrid model behaves when different levels of noise are added for privacy. As the privacy protection gets stronger (higher noise and lower epsilon), the model’s performance gradually drops. At the baseline level without noise, accuracy is 91.4%, and the model shows clear interpretation. With low noise, the drop in accuracy and F1-score is very small, and interpretability stays high. As noise increases further, the model still keeps decent performance, though there is a steady decline. Even under medium to high noise, the scores stay above 84% accuracy and 0.81 F1-score, which suggests the model can still make good predictions under privacy-preserving conditions.

The proposed model handles this trade-off better than typical deep models due to its selective feature handling through TabNet and stable layer-wise representation in CNN. These structures help preserve useful signals even when the data has been slightly distorted to protect privacy. This balance makes the model suitable for sensitive environments like healthcare where both accuracy and privacy matter.

Table 9 presents the privacy-performance balance on the GSE72056 dataset. While earlier methods achieved decent accuracy, their performance dropped sharply when noise or perturbations were introduced. The proposed model delivered the highest accuracy with the least performance decline, helped by adaptive noise injection and stable feature selection.

Table 10 describes the trade-offs in the TCGA-BRCA dataset. Existing methods showed moderate resilience under noise, but the proposed model kept accuracy above 90% and handled perturbations better, with minimal performance dip. This behavior is supported by the robustness of TabNet’s attention gating and CNN’s local feature encoding.

Table 11 shows results for the ENCODE epigenomic dataset. The proposed model outperformed others, achieving high accuracy while maintaining privacy. Its performance drop under perturbation remained below 3.5%, which reflects the adaptive design of the noise layer and consistent behavior of the hybrid architecture under varied input quality. These results reflect that the proposed approach strikes a better balance between accuracy and privacy, without compromising interpretability or robustness.

Table 12 shows the privacy–utility balance achieved by various models on the GSE72056 dataset. While previous works such as those by Zhu et al. and Abbas et al. applied conventional privacy techniques like anonymization and differential privacy (DP), these often led to reduced prediction quality–especially for low-expressed genes. In contrast, the proposed framework introduced adaptive DP combined with feature masking, which helped maintain high classification performance without exposing sensitive patient information.

Table 13 presents results on the TCGA-BRCA dataset. Earlier models used encryption, pseudonymization, or simple DP techniques, but these introduced trade-offs such as the loss of interpretability or poor retention of gene-level patterns. The proposed model used saliency-based masking guided by TabNet attention, allowing the system to protect informative features while still keeping prediction performance high.

Table 14 focuses on the ENCSR000AED dataset. Traditional methods like scrambling and obfuscation often degraded the quality of regulatory signal analysis. The proposed model handled these better by combining adaptive noise injection with controlled dropout, leading to better utility preservation under privacy constraints.

Across all datasets, the proposed system handled privacy-sensitive data more effectively than existing models. Its attention-guided masking strategy and adaptable noise schemes allowed strong performance while respecting privacy needs in biomedical applications.

Model interpretability and biological relevance

The proposed framework includes attention mechanisms and convolutional layers, which help to make the decision process easier to understand. Figures 10a 11a, and 12a show the attention score distributions for the GSE72056, ENCSR000AED, and TCGA-BRCA datasets respectively. In the GSE72056 dataset (Figure 11a), high attention weights are observed for genes like CD8A, PDCD1, and FOXP3. These markers are commonly involved in immune response, which aligns with the immune-rich nature of the melanoma samples in the dataset. In the ENCSR000AED dataset (Fig. 12a), the top-scoring features include GATA1 and STAT5A, which play important roles in transcription regulation and epigenomic modulation. In the TCGA-BRCA dataset (Fig. 10a), the model focuses strongly on TP53, BRCA1, and HER2–genes that are well studied in the context of breast cancer biology.

Figures 10b,11b, and 12b show the corresponding CNN activation maps for each dataset. These visualizations highlight spatial activations across convolutional layers that contribute to the final classification output. GSE72056 activations appear dense and centralized, indicating selective responses to localized gene patterns. The ENCSR000AED activation map is more dispersed, which may reflect broader epigenomic diversity. For TCGA-BRCA, the activations show clustered regions, which may correspond to highly discriminative genomic patterns observed in cancer subtypes.

As shown in Fig. 11a, the attention plot for the GSE72056 dataset gives higher importance to genes such as MS4A1, CD3D, and NKG7. These genes are associated with immune response activity and are often highlighted in single-cell RNA-seq analyses. The activation heatmap for the same dataset (Fig. 11b) shows strong activations in clustered regions, indicating the model’s focus on certain structured feature areas.

For the ENCSR000AED dataset, Fig. 12a shows attention scores concentrated around key transcriptional regulators like RAD21, CTCF, and SMC3. These features are essential for genome organization and chromatin looping. The corresponding activation map (Fig. 12b) presents more distributed and intense activations, suggesting deeper involvement of spatial dependencies in the feature representation.

These visualizations help explain how the model reacts to each genomic input. Attention plots reflect which features influenced the model’s decision most, while activation maps reveal the internal layer response patterns. This combination adds transparency to the proposed model and supports interpretation in the context of biological relevance.

Ablation study

To better understand the role of each part in the proposed framework, an ablation study was expanded. This experiment separates the impact of individual components by testing different combinations and observing performance changes. Five model configurations were evaluated on all datasets:

-

CNN-only model: The network used only convolutional layers for feature extraction and classification, without TabNet or the AFR module.

-

TabNet-only model: The setup relied solely on the TabNet block for feature selection and decision-making, without convolutional layers or AFR.

-

TabNet + CNN (without AFR): The two main modules worked together, but the AFR layer was excluded.

-

Proposed model (TabNet + AFR + CNN): The complete framework as described in the main architecture, including AFR to refine informative features and suppress noise.

The results are shown in Table 15. For the TCGA-BRCA dataset, the CNN-only model reached 86.2% accuracy, and the TabNet-only variant achieved 87.5%. The TabNet + CNN model without AFR improved performance to 89.1%. When AFR was added, the full model reached 90.8%. Similar gains were observed in GSE72056 and ENCSR000AED, where AFR consistently added 1.5–2% improvement in accuracy.

This comparison shows that the AFR module plays a meaningful role by refining features before classification. The attention maps and activation plots in Figure 10a and b further highlight that AFR strengthens signals from key genomic regions while reducing noise interference, which supports the quantitative improvements observed.

Table 16 present a detailed comparison of the proposed framework with recent DL models. The hybrid TabNet–CNN demonstrates superior performance in all evaluation metrics.

Practical implications

The interpretability and stability of the proposed model allow its integration into real-world clinical workflows. The model can identify potential genomic biomarkers, assist in disease subtype differentiation, and provide explainable recommendations for personalized treatment design. Its modular design also supports adaptation to future multi-omics datasets and edge-intelligent healthcare systems.

Dataset limitations and mitigation strategies

Although the model achieves promising results, genomic datasets such as TCGA-BRCA and GSE72056 exhibit class imbalance, redundancy, and noise. To mitigate these issues, stratified sampling and attention-based feature masking were applied during preprocessing. Future research will focus on extending this framework to multi-cohort validation and large-scale genomic repositories to enhance generalizability.

Conclusion and future scope

This study presents a hybrid deep learning framework for disease prediction using multi-omics datasets, including single-cell RNA-seq, gene expression, and epigenomic signals. The framework integrates the feature selection capability of TabNet with the spatial representation learning of convolutional neural networks, enabling effective modeling of high-dimensional biological data. Experimental evaluations conducted on multiple publicly available datasets indicate that the proposed framework achieves competitive performance with respect to accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-score when compared to recent state-of-the-art methods. The use of attention-based feature selection and layer-wise activation analysis provides interpretable insights into model behavior, which may support downstream biological analysis and hypothesis generation. These interpretability mechanisms help identify influential features and interactions across different omics layers, contributing to improved transparency in model predictions. The results suggest that combining attention-driven tabular modeling with deep spatial feature extraction can enhance predictive performance across heterogeneous genomic data sources. The framework demonstrates stable learning behavior under varying noise levels and data distributions within the evaluated datasets. Its architecture is designed to handle high-dimensional and sparse inputs while reducing reliance on extensive manual feature engineering. However, the observed performance gains are specific to the datasets and experimental settings considered in this study and may vary under different biological or clinical conditions. Future research directions include optimizing the network architecture to reduce computational overhead and training time while maintaining predictive accuracy. The exploration of lightweight variants may support deployment in resource-constrained environments. Extending the framework to privacy-preserving learning paradigms, such as federated learning, may enable collaborative model training across decentralized biomedical institutions. Additional work may also investigate the integration of complementary clinical modalities, including medical imaging, pathology reports, and longitudinal patient records. Advanced attention fusion strategies could further improve cross-omics interpretability and feature interaction analysis.

Limitations of the proposed framework

Despite its effectiveness, the proposed framework has several limitations. The training process involves substantial computational and memory requirements, particularly during the integration of TabNet-derived representations with convolutional layers. This may limit applicability in low-resource or real-time clinical settings. While the framework demonstrates consistent performance on selected public datasets, its generalization to unseen populations, rare disease cohorts, or datasets with strong batch effects and demographic variability remains uncertain. Performance may be affected when applied to cross-population studies or data collected under heterogeneous experimental conditions. In scenarios involving extremely sparse genomic features or limited sample sizes, such as early-stage clinical studies or rare disease research, the model may be susceptible to reduced stability and potential overfitting. In such cases, additional regularization strategies, transfer learning, or data augmentation techniques may be required to maintain reliable performance. Finally, although the framework provides visually interpretable attention maps and activation patterns, meaningful biological interpretation often requires domain expertise. Attention-based explanations alone may not fully capture complex regulatory mechanisms, particularly in epigenomic analyses, and should be interpreted in conjunction with established biological knowledge.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available and can be accessed from their respective sources. Single-cell RNA-seq data, gene expression datasets, and genomic sequencing benchmarks referenced in the experimental evaluation were obtained from open-access biological repositories such as GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus)9, TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas)8, and ENCODE11. To support transparency and reproducibility, the complete source code corresponding to the version used to generate the results reported in this study is publicly available in a version-controlled repository (https://github.com/PREMKUMARCH/Hybrid-Deep-Learning-Framework-for-Accurate-Classification-of-High-Dimensional-Genomic-Data).

References

Dhaarani, R., & Reddy, M.K. Progressing microbial genomics: Artificial intelligence and deep learning driven advances in genome analysis and therapeutics. Intelligence-Based Medicine 100251 (2025)

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Shah, M. A. RNA-Seq analysis for breast cancer detection: a study on paired tissue samples using hybrid optimization and deep learning techniques. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 150, 455 (2024).

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N.K., & Aziz, R.M. Improving breast cancer classification with mRMR+SS0+WSVM: a hybrid approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–26 (2024)

Yaqoob, A., Bhat, M. A. & Khan, Z. Dimensionality reduction techniques and their applications in cancer classification: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Genet. Modif. Recomb. 1, 34–45 (2023).

Yaqoob, A. et al. SGA-Driven feature selection and random forest classification for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis: A comparative study. Sci. Rep. 15, 10944 (2025).

Arik, A., & Pfister, T. TabNet: Attentive interpretable tabular learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35, 6679–6687 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i8.16826

Kelley, D. R., Snoek, J. & Rinn, J. L. Basset: learning the regulatory code of the accessible genome with deep convolutional neural networks. Genome Res. 26, 990–999 (2016).

National Cancer Institute: The Cancer Genome Atlas Program. https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga (2019). Accessed 26 Apr 2025

Barrett, T., Troup, D., Wilhite, S. et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/

Wellcome Sanger Institute: Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer. https://www.cancerrxgene.org/ (2024). Accessed 26 Apr 2025

ENCODE Project Consortium: An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). https://www.encodeproject.org/

Johnson, A.E.W., Pollard, T.J., Shen, L. et al.: MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data 3, 160035 (2016). https://physionet.org/content/mimiciii/1.4/

El-Nabawy, A., El-Bendary, N. & Belal, N. A. A feature-fusion framework of clinical, genomics, and histopathological data for METABRIC breast cancer subtype classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 91, 106238 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. BrcaSeg: A deep learning approach for tissue quantification and genomic correlations of histopathological images (Genom. Proteom, 2021).

Wei, C., Zhang, J. & Yuan, X. DeepTIS: Improved translation initiation site prediction in genomic sequence via a two-stage deep learning model. Digit. Signal Process. 117, 103202 (2021).

Huang, K. et al. Machine learning applications for therapeutic tasks with genomics data. Patterns 2, 10 (2021).

Ye, T., Li, S. & Zhang, Y. Genomic pan-cancer classification using image-based deep learning. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 835–846 (2021).

Ahemad, M. T., Hameed, M. A. & Vankdothu, R. COVID-19 detection and classification for machine learning methods using human genomic data. Meas. Sens. 24, 100537 (2022).

Erfanian, N. et al. Deep learning applications in single-cell genomics and transcriptomics data analysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 165, 115077 (2023).

Bazgir, O. & Lu, J. REFINED-CNN framework for survival prediction with high-dimensional features. iScience 26, 9 (2023).

Khodaei, A., Shams, P. & Mozaffari-Tazehkand, B. Identification and classification of coronavirus genomic signals based on linear predictive coding and machine learning methods. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 80, 104276 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. DNNGP, a deep neural network-based method for genomic prediction using multi-omics data in plants. Mol. Plant 16, 279–293 (2023).

Zhu, G. et al. GSRNet, an adversarial training-based deep framework with multi-scale CNN and BiGRU for predicting genomic signals and regions. Expert Syst. Appl. 229, 120439 (2023).

Abu-Doleh, A. & Al Fahoum, A. XgCPred: Cell type classification using XGBoost-CNN integration and exploiting gene expression imaging in single-cell RNAseq data. Comput. Biol. Med. 181, 109066 (2024).

Mohammed, R. K., Alrawi, A. T. H. & Dawood, A. J. U-Net for genomic sequencing: A novel approach to DNA sequence classification. Alex. Eng. J. 96, 323–331 (2024).

Barber, F. B. N. & Oueslati, A. E. Human exons and introns classification using pre-trained Resnet-50 and GoogleNet models and 13-layers CNN model. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 22, 100359 (2024).

Nawaz, M. S., Nawaz, M. Z., Zhang, J., Fournier-Viger, P. & Qu, J. F. Exploiting the sequential nature of genomic data for improved analysis and identification. Comput. Biol. Med. 183, 109307 (2024).

Abbas, T., et al. Multidisciplinary cancer disease classification using adaptive FL in healthcare industry 5.0. Sci. Rep. 14, 18643 (2024)

Mora-Poblete, F., Mieres-Castro, D., do Amaral Júnior, A.T., Balach, M., & Maldonado, C. Integrating deep learning for phenomic and genomic predictive modeling of Eucalyptus trees. Ind. Crops Prod. 220, 119151 (2024)

Feng, W., Gao, P. & Wang, X. AI breeder: Genomic predictions for crop breeding. New Crops 1, 100010 (2024).

Batra, U., et al. AI-based pipeline for early screening of lung cancer: integrating radiology, clinical, and genomics data. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 24, (2024)

Sangeetha, S. K. B. et al. An enhanced multimodal fusion deep learning neural network for lung cancer classification. Syst. Soft Comput. 6, 200068 (2024).

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K. & Aziz, R. M. Optimizing gene selection and cancer classification with hybrid sine cosine and cuckoo search algorithm. J. Med. Syst. 48, 10 (2024).

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N.K., Aziz, R.M., & Saxena, A. Enhancing feature selection through metaheuristic hybrid cuckoo search and Harris Hawks optimization for cancer classification. In: Metaheuristics for Machine Learning: Algorithms and Applications, 95–134 (2024)

Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Shah, M. A. Optimizing cancer classification: a hybrid RDO-XGBoost approach for feature selection and predictive insights. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 73, 261 (2024).

Yaqoob, A. Combining the mRMR technique with the Northern Goshawk Algorithm (NGHA) to choose genes for cancer classification. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 1–12 (2024)

Yaqoob, A. & Verma, N. K. Feature Selection in Breast Cancer Gene Expression Data Using KAO and AOA with SVM Classification. J. Med. Syst. 49, 1–21 (2025).

Raja, S. E., Sutha, J., Elamparithi, P., Deepthi, K. J. & Lalitha, S. D. Liver tumor prediction using attention-guided convolutional neural networks and genomic feature analysis. MethodsX 14, 103276 (2025).

Lin, Z., Yoshikawa, S., Hamasaki, M., Kikuchi, K. & Hosoya, S. Automated phenotyping empowered by deep learning for genomic prediction of body size in the tiger pufferfish. Takifugu rubripes. Aquaculture 595, 741491 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Cropformer: An interpretable deep learning framework for crop genomic prediction. Plant Commun. 6, 3 (2025).

Wu, H., et al. AutoGP: An intelligent breeding platform for enhancing maize genomic selection. Plant Commun. (2025)

Mir, A. N., Rizvi, D. R. & Ahmad, M. R. Enhancing histopathological image analysis: An explainable vision transformer approach with comprehensive interpretation methods and evaluation of explanation quality (Eng. Appl. Artif, 2025).

Mir, A. N. & Rizvi, D. R. Advancements in deep learning and explainable artificial intelligence for enhanced medical image analysis: A comprehensive survey and future directions (Eng. Appl. Artif, 2025).

Mir, A. N., Rizvi, D. R. & Nissar, I. Enhancing medical image report generation using a self-boosting multimodal alignment framework (Health Inf. Sci, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R435), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University). This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R435), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K.S., N.K.K., and L.J.; Methodology: M.K.S., N.K.K., and L.J.; Formal analysis and data curation: M.K.S., N.K.K., and L.J.; Writing–original draft preparation: M.K.S.; Writing–review and editing: M.K.S., N.K.K., and L.J.; Supervision: N.K.K., L.J., P.K., M.Y.A., and D.M.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swain, M.K., Kamila, N.K., Jena, L. et al. Hybrid deep learning framework for accurate classification of high dimensional genomic data. Sci Rep 16, 5919 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36128-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36128-7