Abstract

Topological indices (TIs) are powerful tools for exploring the relationship between molecular structure and drug activity, offering a cost-effective alternative to experimental screening. The Euler–Sombor index, a recently introduced degree-based TI, captures key structural features of molecules that influence their physico-chemical behaviour. This study investigates the use of the Euler–Sombor index in quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) modeling of anticancer drugs. By applying linear, quadratic, and logarithmic regression models, we predict important properties such as boiling point (BP), melting point (MP), enthalpy (E), and molar refraction (MR). The results show a significant correlation between the Euler–Sombor index and these molecular properties. In addition, we extend the result of Su and Tang by characterizing unicyclic graphs that have the third minimum Euler–Sombor index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) analysis has emerged as a powerful approach in modern drug discovery, particularly in the study of anticancer agents. The development of new drugs is often expensive, time-intensive, and requires extensive experimental validation, making computational models highly valuable for predicting molecular behaviour. By establishing correlations between molecular structure and physico-chemical properties, QSPR provides a reliable framework to estimate characteristics such as boiling point, melting point, enthalpy, and molar refraction before experimental synthesis1. This not only accelerates the identification of drug but also reduces the risk of toxicity and inefficacy in later stages of testing. In the context of cancer treatment, where rapid and effective drug development is crucial, QSPR Modeling based on topological indices offers an efficient tool to understand structure–activity relationships. Structure–property modeling and isomer discrimination through QSPR analysis using topological indices and have been investigated in2,3. Recently, Sombor-type topological indices have been extensively applied in QSPR and QSAR studies. In particular, their effectiveness has been demonstrated in modeling physicochemical and biological properties of anticancer drugs, amylose, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using regression and data-driven approaches4,5,6. For some recent works on topological indices and QSPR Modeling, one can refer7,8,9,10,11.

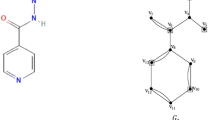

In this article, we assume that G is a graph consisting of n vertices and m edges. We denote its vertex set and edge set as V(G) and E(G), respectively. If two vertices u and v are adjacent, we denote this relationship as \(u \sim v\). A pendant vertex is a vertex of degree one. A vertex that is adjacent to a pendant vertex is a quasi-pendant vertex. The class of unicyclic graphs of order n and girth k, \(3\le k\le n\) is denoted as \(\mathcal {U}_{n,k}\), and the class of graphs formed by attaching a pendant vertex of a path to a vertex on the cycle \(C_{k}\) is denoted as \(U_{n,k}\), see Fig. 19. Topological indices are essential tools in chemical graph theory that connect the structure of molecular graphs to various physico-chemical properties of compounds. Numerous vertex-degree-based indices (VBD indices) have been developed in the literature to capture the structural features of molecular graphs. These indices are extensively used in predicting molecular properties and aiding in QSAR/QSPR studies. In recent years, some new VDB indices with geometric interpretations have been discovered. Gutman12 proposed a novel method for designing such indices in 2021 and introduced the Sombor index SO(G). It is given by

See13,14,15,16 for details. Gutman et al.17 later introduced the Elliptic-Sombor (ESO) index as

This index relates to the perimeter of an ellipse and has meaningful chemical interpretations. See18 for details.

Recently, Barman and Das19, introduced hyperbolic Sombor index HSO(G). It is defined as

In this context, Gutman20 and Tang et al.21 independently introduced the Euler–Sombor index EuSO(G). It is defined as

This newly introduced index has attracted attention for its mathematical depth and chemical relevance. Inequalities connecting the Sombor index and Euler–Sombor index were established in20, while extremal values for trees, unicyclic, and bicyclic graphs were determined in21,22. Further investigations have lead to extremal graphs for unicyclic graphs with fixed girth and diameter22,23, as well as minimal and maximal graphs among tricyclic graphs24,25. See26,27, for additional studies on Euler–Sombor index.

Motivated by these developments, we investigate the use of the Euler–Sombor index in quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) modeling of anticancer drugs. By applying linear, quadratic and logarithmic regression models, we predict important properties such as boiling point (BP), melting point (MP), enthalpy (E), and molar refraction (MR). In addition, we characterize unicyclic graphs that have the third minimum Euler–Sombor index.

Extremal topological indices play an important role in QSPR analysis by describing the range within which a physicochemical property can vary for a given class of molecules, such as different isomers or specific graph families. The study of extremal molecular structures helps clarify which structural characteristics have the greatest impact on the property values. In this context, the QSPR analysis presented in the section “QSPR analysis of anticancer drugs” and the theoretical investigation in the section “Unicyclic graph with third minimum Euler–Somborindex” focus on complementary aspects of the Euler–Sombor index, together providing a coherent understanding of both its practical predictive ability and its theoretical bounds.

QSPR analysis of anticancer drugs

In this study, we employ the Euler–Sombor index to model four important physico-chemical properties—boiling point (BP), melting point (MP), enthalpy (E), and molar refraction (MR) of 17 selected anticancer drugs. The experimental values of these properties are obtained from ChemSpider and are also reported in7,28. The molecular structures corresponding to the anticancer drugs namely Carmustine, Caulibugulone E, Convolutamine F, Perfragilin A, Melatonin, Convolutamydine A, Tambjamine K, Pterocellin B, Amathaspiramide E, Aspidostomide E, Aminopterin, Podophyllotoxin, Convolutamide A, Deguelin, Minocycline, Daunorubicin, and Raloxifene, are shown in Fig. 1. The experimental data for these compounds are summarized in Table 1.

Here we consider three types of models, namely

-

(1)

\(Y=AX+B\) - linear model

-

(2)

\(Y=A+BX+CX^2\) - quadratic model

-

(3)

\(Y=A\ln (X)+B\) - logarithmic model.

In the above models, Y is the variable that depends on the independent variable X, while the regression constants are represented by A, B and C. We denote the correlation coefficient, standard error of the model, the F-test value and the significance by r, SE, F and SF respectively.

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients between the EuSO index and different Sombor-type topological indices considered in Table 2. It is observed that the EuSO index shows an excellent correlation with the SO index across all three models, with \(r \approx 0.9998\). Strong correlations are also observed with ESO and HSO indices, particularly under quadratic and linear models, while the logarithmic model gives slightly weaker associations.

Boiling point v/s Euler–Sombor index

Based on data presented in Tables 1 and 2, we get follwing plots for EuSO and BP.

The following models are depicted in Fig. 2.

-

Linear model (Fig. 3): \(BP=3.1332(EuSO)+216.12\), \(r^2=0.768\).

-

Quadratic model (Fig. 4): \(BP=-0.0118(EuSO)^2+5.8375(EuSO)+84.0116\), \(r^2=0.7842\).

-

Logarithmic model (Fig. 5): \(BP=320.51\ln (EuSO)-917,2\), \(r^2=0.7786\).

Melting point v/s Euler–Sombor index

The following models are depicted in Fig. 6.

-

Linear model (Fig. 7): \(MP=1.055(EuSO)+93.905\), \(r^2=0.5717\).

-

Quadratic model (Fig. 8): \(MP=-0.0104(EuSO)^2+3.4411(EuSO)-20.326\), \(r^2=0.6445\).

-

Logarithmic model (Fig. 9): \(MP=111.28\ln (EuSO)-301.78\), \(r^2=0.6135\).

Enthalpy v/s Euler–Sombor index

The following models are depicted in Fig. 10.

-

Linear model (Fig. 11): \(E=0.3906(EuSO)+43.703\), \(r^2=0.7561\).

-

Quadratic model (Fig. 12):\(E=-1\times 10^{-5}(EuSO)+0.3935(EuSO)+43.564\), \(r^2=0.7561\).

-

Logarithmic model (Fig. 13): \(E=39.099\ln (EuSO)-93.411\), \(r^2=0.723\).

Molar refraction v/s Euler–Sombor index

The following models are depicted in Fig. 14.

-

Linear model (Fig. 15): \(MR=0.5718(EuSO)+28.361\), \(r^2=0.8276\).

-

Quadratic model (Fig. 16): \(MR=-0.0028(EuSO)^2+1.2224(EuSO)-3.4189\), \(r^2=0.8579\).

-

Logarithmic model (Fig. 17): \(MR=58.671\ln (EuSO)-179.29\), \(r^2=0.8441\).

Results and discussions

The regression analysis of the EuSO index with respect to four physico-chemical properties—boiling point, melting point, enthalpy, and molar refraction was carried out using linear, quadratic, and logarithmic models. The Figs. 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 17 consist of residual plots and in particular bar diagrams are used to compare the experimental properties with predicted properties. In bar diagrams blue bars indicate the actual values, whereas orange bars represent the predicted values. Tables 5, 7, 9 and 11 present comparisons of actual and predicted values for the predictive models within the linear, quadratic, and logarithmic regression frameworks. This visualization facilitates a direct comparison between actual and predicted data. From Tables 4, 6, 8 and 10 we can observe the following results.

Coefficient of correlation

-

For boiling point and enthalpy, all models give strong correlations (\(r \approx 0.85-0.88\)), showing a good linear association between the EuSO index and the property.

-

For melting point, r values are slightly lower (\(\approx 0.75-0.80\)), indicating weaker predictive strength.

-

For molar refraction, very high correlations are obtained (\(r>0.90\)), confirming that the EuSO index strongly predict this property across models.

Standard error

-

SE values for boiling point are all large (\(\approx 80\)), suggesting higher variability and less precise predictions compared to the other properties.

-

For melting point, SE decreases to (\(\approx 44\)–46), indicating slightly better precision.

-

For enthalpy, SE is much smaller (\(\approx 11\)), showing high accuracy of model.

-

For molar refraction, SE values are again small (\(\approx 11\)–12), reinforcing very precise prediction.

F-value and SF-value

-

All three models showed strong correlation (\(r \approx 0.87\)) for boiling point; however, the logarithmic model displayed the highest F-value (52.7362) and the lowest SF-value (\(2.78 \times 10^{-6}\)), indicating superior statistical significance and predictive accuracy compared to the linear and quadratic models.

-

A similar trend was observed in case of melting point, where the logarithmic model again outperformed the other models with a higher F-value (19.05) and smaller SF (0.000921), suggesting that it provides a more reliable prediction, while the quadratic model was the least effective.

-

Although all models had strong correlation (\(r \approx 0.85\)) for enthalpy, the linear model gave the best performance with the highest F-value (40.29748) and the smallest SF-value (\(2.54 \times 10^{-5}\)), making it the most accurate for this property.

-

A very high correlations were observed for all models (\(r> 0.90\)) in case of molar refraction, but the logarithmic model again proved superior, yielding the highest F-value (81.20948) and the lowest SF-value (\(1.93 \times 10^{-7}\)), despite the quadratic model having a slightly lower SE.

Overall, the analysis reveals that the logarithmic regression model provides the most reliable predictions for boiling point, melting point, and molar refraction, while the linear regression model is slightly better suited for enthalpy. The quadratic model, in contrast, consistently showed weaker performance across all properties, with lower statistical significance and less predictive accuracy. These results highlight the strong applicability of logarithmic regression in modeling the relationship between the EuSO index and various physico-chemical properties, except in the case of enthalpy, where a linear relationship appears more appropriate.

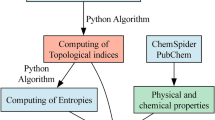

Techniques used for computation of results

The values of the Euler–Sombor (EuSO) index were computed using MATLAB, and these indices were then correlated with the selected properties through QSPR analysis. Three different regression models—linear, quadratic, and logarithmic—were developed in Microsoft Excel to establish predictive relationships. Statistical parameters including correlation coefficient (r), standard error (SE), F-value, and standard error of model (SF) were determined to assess the significance and accuracy of the models. To further validate the analysis, scatter plots, residual plots, and bar diagrams were constructed to compare actual and predicted values, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the predictive performance of the EuSO index. The workflow of the QSPR methodology illustrating data collection, computation of Sombor index variants, statistical modeling, and correlation analysis for anti-cancer drug molecules depicted in Fig. 18.

Methodology

Limitations and future work

Although the Euler–Sombor index shows strong correlations with the physicochemical properties of the selected anticancer drugs, some limitations should be noted. Despite the presence of strong correlations, the statistical evaluation indicates that the boiling point (BP) prediction model exhibits a comparatively high standard error (SE \(\approx 80\)). This reflects lower predictive precision for BP when compared with the enthalpy and molar refraction models, which demonstrate substantially smaller SE values (\(\approx 10\)–12). Moreover, the analysis is based on a limited number of drug molecules, which may affect the general applicability of the results; however, the main aim of this work was to study structure–property relationships rather than to build highly general predictive models. In future studies, larger datasets, additional molecular descriptors, and improved modeling techniques may be considered to enhance prediction accuracy.

Unicyclic graph with third minimum Euler–Sombor index

The Euler–Sombor index of a cycle \(C_{n}\) is \(2\sqrt{3}n\), and it is the minimum among all unicyclic graphs. In this section, we identify unicyclic graphs that have a specified girth and possess the third minimum Euler–Sombor index. Our study, indeed extends the following result obtained by Su and Tang.

Theorem 3.1

1 Let \(G\in \mathcal {U}_{n,k}\) \((3\le k\le n-2)\). Then \(EuSO(G)\ge 3\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{7}+2(n-4)\sqrt{3}\) equality holds if and only if \(G\cong U_{n,k}\).

We need the following classes of unicyclic graphs (see Fig. 19).

Class \(U^{1}_{n,k}\): This class consists of unicyclic graphs of order n formed by attaching a pendant vertex of a path of length s to a vertex x in the cycle \(C_{k}\), and then a pendant vertex of another path of length t is attached to some other vertex y (\(x\ne y\)) in the same cycle \(C_{k}\), where \(s\ge t\ge 1\).

Class \(U^{2}_{n,k}\): A unicyclic graph of order n in this class can be obtained by attaching a pendant vertex in each of the two paths of length s and t to a vertex x of the cycle \(C_k\), where \(s\ge t\ge 1\).

Class \(U^{3}_{n,k}\): Consists of graphs obtained by attaching a path of length t between a vertex x of the cycle \(C_k\) and a non-pendant vertex y of a path of length s, where \(s\ge 2, t\ge 1\). The following two lemmas proved in1 are important to prove our results.

Lemma 3.2

1 Let G be a graph and let \(P:x_0-x_1-x_2-\cdots x_{k-1}-x_{k}-\cdots -x_p\) be a path in G with \(d_G(x_0)=d_G(x_p)=1\), \(d_G(x_i)=2\) for \(2\le i\le p-1\) and \(i\ne k\), and \(d_G(x_k)\ge 3\). Then for the graph \(G'=G-x_kx_{k-1}+x_{k-1}x_p\), \(EuSO(G)> {EuSO}(G')\).

Lemma 3.3

1 Let \(P_{1}:x-x_1-x_2-\ldots -x_p\) and \(P_{2}:y-y_1-y_2-\dots -y_q\), be two non intersecting paths in a graph \(\Gamma\) such that \(d_{\Gamma }(x_i)=2\) \((1\le i\le p-1)\), \(d_{\Gamma }(y_j)=2\) \((1\le j\le q-1)\), \(d_{\Gamma }(x)\ge 3\), \(d_{\Gamma }(y)\ge 3\) and \(d_{\Gamma }(x_{p})=d_{\Gamma }(y_{q})=1\). Then for the graph \(\Gamma ^{\prime }=\Gamma -xx_1+x_1y_q\), \(EuSO(\Gamma )>EuSO(\Gamma ^{\prime })\).

Lemma 3.4

Let G be a graph that belongs to one of the classes \(U^1_{n,k}\) or \(U^2_{n,k}\), where \(3\le k\le n-4\). Then \(EuSO(G)\ge 4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\). Equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^1_{n,k}\) with \(s\ge t>1\) and \(x\sim y\).

Proof

We have the following cases. Case 1. Suppose \(G\in U^1_{n,k}\). If \(x\sim y\) in G, then

Otherwise, \(x\not \sim y\) in G. In this case,

Case 2. Suppose \(G\in U^2_{n,k}\). Then

Now, \(4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\) < \(6\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+2(n-8)\sqrt{3}\) < \(3\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{7}+\sqrt{13}+(2n-9)\sqrt{3}\) < \(5\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{7}+\sqrt{13}+2(n-7)\sqrt{3}\) < \(10\sqrt{7}+2(n-6)\sqrt{3}\) < \(\sqrt{21}+7\sqrt{7}+2(n-5)\sqrt{3}\). Thus, we arrive at the result.

Lemma 3.5

Let G be a graph in \(U^3_{n,k}\) (\(3\le k\le n-4\)). Then \(EuSO(G)\ge 4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\). Equality holds if and only if \(x\sim y\) in G (i.e., \(t=1\)) and y is not a quasi-pendant vertex.

Proof

Assume that \(t=1\). Since \(k\le n-4\), \(s\ge 3\). So, y is adjacent to at most one pendant vertex. Therefore,

Suppose \(t>1\). Then

Now, \(4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\) < \(6\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+2(n-8)\sqrt{3}\) < \(3\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{13}+\sqrt{7}+(2n-9)\sqrt{3}\) < \(5\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{13}+\sqrt{7}+2(n-7)\sqrt{3}\) < \(4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{13}+2(n-6)\sqrt{3}\), and hence the result follows. \(\square\)

Let \(U^*_{n,k}\) (\(3\le k\le n-4\)) denote the class of unicyclic graphs consisting of graphs that belong to \(U^1_{n,k}\) with \(s\ge t\ge 2\) and \(x\sim y\), and also the graphs in \(U^2_{n,k}\) with \(x\sim y\) (i.e., \(t=1\)) and y is not a quasi-pendant vertex, see Fig. 20. Note that the Euler–Sombor index of a graph in \(U^*_{n,k}\) is equal to \(4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\), see Lemmas 3.4 and 3.5. Let \(U^{*}_{n,n-3}\) and \(U^{*}_{n,n-2}\) be unicyclic graphs of order n as shown in Fig. 20.

Proposition 3.6

Let \(G\in \mathcal {U}_{n,k}\) and \(G\not \cong U_{n,k}\).

(i) For \(k=n-3\), \(EuSO(G)\ge 3\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{13}+\sqrt{7}+2(n-6)\sqrt{3}\). Equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^*_{n,n-3}\).

(ii) For \(k=n-2\), \(EuSO(G)\ge 2\left[ \sqrt{13}+\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{19}+(n-5)\sqrt{3}\right]\). Equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^*_{n, n-2}\).

In the following theorem, we characterize unicyclic graphs that have the third minimum Euler–Sombor index.

Theorem 3.7

Let \(G\in \mathcal {U}_{n,k}\) (\(3\le k \le n-4\)) and \(G\not \cong U_{n,k}\). Then \(EuSO(G)\ge 4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\). Equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^*_{n,k}\).

Proof

Let C be the unique cycle of length k in G. Since (\(3\le k \le n-4\)), at least one of the vertex in C is of degree at least 3. Suppose at least 2 vertices in C are of degree at least 3, then by Lemmas 3.2 and 3.3, there is a graph \(G_1\in U^1_{n,k}\) such that \(EuSO(G)\ge EuSO(G_1)\). Thus by Lemma 3.4,

and the equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^{1}_{n,k}\cap U^{*}_{n,k}\). Now, assume that there is only one vertex, say v in C of degree at least 3. If \(d(v)\ge 4\), then by Lemma 3.2, there exists a graph \(G_2\in U^2_{n,k}\) such that \(EuSO(G)> EuSO(G_2)\). Thus by Lemma 3.4,

Otherwise, \(d(v)=3\). Since \(G\notin U^{1}_{n,k}\), there is another vertex in G of degree at least 3. Hence, by Lemma 3.2, there exists a graph \(G_{3}\in U^{3}_{n,k}\) such that \(EuSO(G)\ge EuSO(G_3)\). So, by Lemma 3.5, \(EuSO(G)\ge 4\sqrt{19}+2\sqrt{7}+(2n-11)\sqrt{3}\), and the equality holds if and only if \(G\in U^{3}_{n,k}\cap U^{*}_{n,k}\). This completes the proof of the theorem. \(\square\)

Remark 3.8

By direct calculation, \(EuSO(U_{n,n-1})=2\sqrt{19}+\sqrt{13}+2(n-3)\sqrt{3}\) and \(EuSO(C_n)=2n\sqrt{3}\).

The following theorem follows from Theorems 3.1, 3.7 and Remark 3.8.

Theorem 3.9

(i) If \(n=5\), then \(EuSO(U^*_{5,3})\) > \(EuSO(U_{5,4})\) > \(EuSO(U_{5,3})\) > \(EuSO(C_5)\). (ii) If \(n=6\), then \(EuSO(U^*_{6,4})\) > \(EuSO(U^*_{6,3})\) > \(EuSO(U_{6,5})\) > \(EuSO(U_{6,4})\) > \(EuSO(C_6)\). (iii) If \(n\ge 7\), then \(EuSO(U^*_{n,n-2})\) > \(EuSO(U^*_{n,n-3})\) > \(EuSO(U^*_{n,n-4})=\dots =EuSO(U^*_{n,3})\) > \(EuSO(U_{n,n-1})> EuSO(U_{n,3})=\dots =EuSO(U_{n,n-2})\) > \(> EuSO(C_n)\).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the Euler–Sombor (EuSO) index is an effective molecular descriptor for QSPR modeling of anticancer drugs. The regression analyses reveal that the EuSO index exhibits strong and statistically significant correlations with key physico-chemical properties, namely boiling point, melting point, enthalpy, and molar refraction. In particular, logarithmic regression models provide superior predictive performance for boiling point, melting point, and molar refraction, while a linear model yields the most reliable predictions for enthalpy.

From a theoretical perspective, this work also advances the study of the Euler–Sombor index in graph theory. By extending the results of Su and Tang22, we characterized unicyclic graphs of fixed order and girth that attain the third minimum Euler–Sombor index. This characterization enriches the extremal theory of Sombor-type indices and provides further insight into how structural constraints influence degree-based molecular descriptors.

Overall, the combined QSPR analysis and graph-theoretical investigation highlight the dual significance of the Euler–Sombor index, reinforcing its applicability in chemical graph theory as well as in practical modeling of molecular properties relevant to drug discovery.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the ChemSpider repository, [https://share.google/CWCDuNU1J3cBkTXm7].

References

Su, Z. & Tang, Z. Extremal unicyclic graphs for the Euler Sombor index: applications to benzenoid hydrocarbons and drug molecules. Axioms14(4), 249 (2025).

Das, P., Mondal, S., Raza, Z. & Pal, A. On exponential inverse symmetric division deg index of graphs. J. Appl. Math. Comput.71, 537–561 (2025).

Das, P., Mondal, S., Some, B. & Pal, A. Extension of adjacency matrix in QSPR analysis. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst.243, 105024 (2023).

Kara, Y., Sağlam Özkan, Y., Bektaş, A. B. & Arockiaraj, M. Applications of Sombor topological indices and entropy measures for qspr modeling of anticancer drugs: a python-based methodology. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32906-x (2025).

Kirana, B., Shanmukha, M. & Usha, A. Comparative study of Sombor index and its various versions using regression models for top priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sci. Rep.14(1), 19841 (2024).

Mufti, Z. S., Asim, M., Shflot, A., Saeed, S. T. & Younis, J. Data-driven regression analysis of amylose using Sombor molecular descriptors. Sci. Rep.15(1), 44294 (2025).

Altassan, A., Rather, B. A. & Imran, M. Inverse sum indeg index (energy) with applications to anticancer drugs. Mathematics10(24), 4749 (2022).

Mahboob, A., Rasheed, M. W., Dhiaa, A. M., Hanif, I. & Amin, L. On quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) analysis of physicochemical properties and anti-hepatitis prescription drugs using a linear regression model. Heliyon10(4), e25908 (2024).

Mondal, S. & Das, K. C. On the Sanskruti index of graphs. J. Appl. Math. Comput.69(1), 1205–1219 (2023).

Ravi, V. & Chidambaram, N. QSPR analysis of physico-chemical and pharmacological properties of medications for Parkinson’s treatment utilizing neighborhood degree-based topological descriptors. Sci. Rep.15(1), 16941 (2025).

Redžepović, I. & Furtula, B. Comparative study on structural sensitivity of eigenvalue-based molecular descriptors. J. Math. Chem.59(2), 476–487 (2021).

Gutman, I. Geometric approach to degree-based topological indices: Sombor indices. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem86(1), 11–16 (2021).

Cruz, R., Gutman, I. & Rada, J. Sombor index of chemical graphs. Appl. Math. Comput.399, 126018 (2021).

Das, K. C., Çevik, A. S., Cangul, I. N. & Shang, Y. On Sombor index. Symmetry13(1), 140 (2021).

Das, K. C. & Gutman, I. On Sombor index of trees. Appl. Math. Comput.412, 126575 (2022).

Nithya, P., Elumalai, S., Balachandran, S. & Masre, M. Ordering unicyclic graphs with a fixed girth by Sombor indices. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem92, 205–224 (2024).

Gutman, I., Furtula, B. & Oz, M. S. Geometric approach to vertex-degree-based topological indices-elliptic Sombor index, theory and application. Int. J. Quantum Chem.124(2), e27346 (2024).

Espinal, C., Gutman, I. & Rada, J. Elliptic Sombor index of chemical graphs. Commun. Comb. Optim.10(4), 989–999 (2025).

Barman, J. & Das, S. Geometric approach to degree-based topological index: Hyperbolic Sombor index. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem95(1), 63–94 (2026).

Gutman, I. Relating Sombor and Euler indices. Vojnotehnički Glasnik72(1), 1–12 (2024).

Tang, Z., Li, Y. & Deng, H. The Euler Sombor index of a graph. Int. J. Quantum Chem.124(9), e27387 (2024).

Su, Z. & Tang, Z. Extremal unicyclic and bicyclic graphs of the Euler Sombor index. AIMS Math.10(3), 6338–6354 (2025).

Kizilirmak, G. O. Extremal Euler Sombor index of unicyclic graphs with fixed diameter. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem94, 725–738 (2025).

Albalahia, A. M., Alanazib, A. M., Alotaibic, A. M., Hamzaa, A. E. & Alia, A. Optimizing the Euler–Sombor index of (molecular) tricyclic graphs. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem94(2), 549–60 (2025).

Kizilirmak, G. O. On Euler Sombor index of tricyclic graphs. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem94, 247–262 (2025).

Das, P., Mondal, S. & Pal, A. Extremal trees for Euler Sombor index with given parameters. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem95, 777–811 (2026).

Ren, X., Cao, G., Wang, F. & Zhou, M. The Euler–Sombor index of trees. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem94, 739–760 (2025).

Shanmukha, M., Basavarajappa, N., Shilpa, K. & Usha, A. Degree-based topological indices on anticancer drugs with QSPR analysis. Heliyon6(6), e04235 (2020).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S., B.R. and S.U.N.V wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shetty, S., Rakshith, B.R. & Udupa, N.V.S. QSPR analysis of anticancer drugs using the Euler–Sombor index and theoretical insights on its minimum value for unicyclic graphs. Sci Rep 16, 6924 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36855-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36855-x