Abstract

A growing problem in agriculture is the increasing resistance of bacteria to antibiotics used in animal feed. The strong antibacterial activity of tannins, plant polyphenols that can chelate metal ions, makes them one of the potential antibiotic substitutes. The present study investigates the chelation of Fe(II) ions by roburins A and D, ellagitannins isolated from aqueous chestnut wood extract, which is currently used as an antibacterial additive in animal feed. A combination of previously determined stoichiometries and the microscopic protolytic equilibrium of ellagitannins enabled the development of a model describing the contribution of the structural elements NHTP and HHDP to Fe(II) chelation. The parameters obtained from the fit to the experimental Job plots were used to calculate the model Job curves for the roburins. The good agreement between the experimental and model curves confirms the suitability of the model and shows its predictive power in determining the binding stoichiometries and the degree of Fe(II) chelation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a worrying problem1. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) are largely due to the overuse of antibiotics in animal husbandry2. As antibiotic-resistant bacteria can be transmitted from animals to humans3, rapid action is needed worldwide against this alarming health threat. Although established antibiotics are becoming less and less effective1, few new antibiotics have been produced recently4,5. There are several approaches to combat bacterial resistance. The first includes several novel technologies to reduce antibiotic use (e.g., nanotechnology6, anaerobic treatment of livestock wastewater7, co-composting2,8). Although these technologies can be very efficient, antibiotics are still widely used in animal feed3. The second approach involves a strict restriction or even a ban on conventional antibiotics (e.g., antibiotics as growth promoters in the European Union)2. In the third approach, the elimination of bacteria is often supported by replacing common antibiotics with alternatives ranging from plant extracts and organic acids to enzymes, probiotics, or vaccines2,3. However, there is still little information about the antibacterial mechanisms of the alternatives mentioned, their effectiveness, and possible advantages and disadvantages3. A better understanding of their mechanisms of action is therefore necessary if the current variable efficacy of alternatives to antibiotics is to be improved3.

The advantage of natural plant products lies in their generally low toxicity for animals and humans9. Among the plant-based alternatives for antibiotics (phytochemicals)3, tannins are one of the most common substitutes2. Tannins are a group of secondary polyphenolic metabolites that are widely distributed throughout the plant kingdom9,10. Consequently, they make up a significant proportion of polyphenolic compounds in animal and human nutrition10. They have relatively high molecular weights between 500 and 30,000 Da10. Several phenolic groups may be present in their chemical structures, enabling tannins to complex proteins11,12,13 and metal ions14,15,16. Many beneficial biological properties of tannins have been discovered, such as antioxidant17, antibacterial18,19, and anticarcinogenic20 activities, etc.10,21 In addition to their health-promoting properties, tannins have a wide range of applications: production of iron gall ink22, in leather tanning23, as adhesives24, as coagulants for wastewater treatment25, etc. In many cases, the interactions of tannins with metal ions play a crucial role.

Tannins have been used in livestock for more than 30 years to improve feed efficiency, reduce mortality rate, weight gain, gut health3 and protein utilisation in the rumen26, although they were treated as toxic xenobiotics for mammals in the first reviews of tannin extracts27. The positive biological effects of these extracts, such as higher live weight gains or higher milk yields, have also been demonstrated by in vivo studies27. Typical tannins used in livestock breeding are extracts from chestnuts (ETs) and quebracho (proanthocyanidins)3. Currently proposed antibacterial mechanisms of tannins include chelation of iron ions28, disruption of the cell membrane29, inhibition of cell wall synthesis30, and inhibition of fatty acid biosynthetic pathways9. As the addition of tannins to animal feed is becoming more widespread, it is important to understand their molecular mechanisms of action against bacteria. To better understand these mechanisms, the interactions of pure tannin compounds with metal ions need to be investigated. Iron ions are essential for bacterial growth as they are involved in several cellular processes9,31. The tannins present in the growth medium chelate iron ions, causing their deprivation. As the siderophores produced by the bacteria cannot bind and dissolve sufficient iron ions, bacterial growth is inhibited9,32. To better understand interactions with iron ions, it is necessary to investigate both Fe(II) and Fe(III) ions. However, a rapid precipitation in solutions containing ETs and Fe(III) ions33 presents a greater challenge than ET–Fe(II) interactions, making it impossible to observe the resulting coordination compounds as was performed for Fe(II) ions in this study. Ellagitannin-chelated Fe(II) ions eventually oxidise to Fe(III) ions, which is a well-known process for polyphenols34. The binding of Fe(II) ions, however, is much faster than their oxidation to Fe(III) ions34.

Tannins are categorised into four subgroups: proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins), phlorotannins, complex tannins, and hydrolysable tannins10. The latter are further subdivided into ellagitannins and gallotannins10,35. ETs are esters of hexahydroxydiphenic acid and a polyol, usually glucose or quinic acid36. One of their most important sources is the aqueous extract from the wood of the chestnut tree (Castanea sativa). Aqueous chestnut wood extracts contain gallic acid (GA), ellagic acid, and several larger ETs, namely vescalin (VI), castalin (CI), vescalagin (VG) and castalagin (CG), as well as dimeric compounds consisting of two molecules of vescalagin - roburin A (RO-A) and a dimer of vescalagin and castalagin - roburin D (RO-D)37. As can be seen in their chemical structures (Fig. 1), these ETs differ in the number of nonahydroxytriphenoyl (NHTP, three coupled aromatic rings bound to the glucose residue by three ester bonds and a C-C bond between the C-1 atom of the glucose residue and the C-atom of the aromatic ring I) and hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP, two coupled aromatic rings bound to the glucose residue by two ester bonds) groups, and in the stereoconfiguration at the C-1 atom (epimeric diastereomers: R\(^{1}\) = OH, R\(^{2}\) = H for VI, VG and RO-A; R\(^{1}\) = H, R\(^{2}\) = OH for CI, CG and RO-D)37,38.

In the present study, the ability of two high-molecular-weight ETs, RO-A and RO-D, to chelate iron(II) ions was investigated. Moreover, by combining the results of our previous research dealing with the protolytic equilibrium of ETs (VI, CI, VG and CG)39 and the chelating ability of iron(II) by the same ETs40 together with the experimental data obtained here, the new model describing ET–Fe(II) interactions was developed. Since RO-A and RO-D were not commercially available in sufficient quantities, they were first isolated from a commercial aqueous chestnut wood extract. These roburins (ROs) were included because they are a significant component of the aqueous chestnut wood extract. The chemical structures of both ROs contain two HHDP and two NHTP groups, so it can be confirmed that the contribution of the NHTP and HHDP groups to the iron chelation of the ETs is cumulative, as both should be able to chelate two and one Fe(II) ions, respectively, as shown in our previous study40. After isolation of the ROs, their protolytic equilibrium was analysed. Subsequently, the stoichiometries of the coordination compounds were analysed using Job’s method. In addition, the model functions used in our previous work40 were improved by using microscopic p\(K_\textrm{a}\) constants39. These results allowed us to derive a model that can be used to explain iron(II) ion chelation by any ET with NHTP or HHDP groups. This new model was used to describe the Job plots for ETs from our previous study40. Subsequently, the obtained apparent formation constants and molar absorption coefficient were used to calculate the model values of the Job plot for RO-A and RO-D. These model curves were compared with the experimental values for RO-A and RO-D to confirm the validity of the model and its ability to predict Fe(II) ion chelation of untested ETs consisting of NHTP and HHDP groups. The present study is the first to address the protolytic equilibrium of ROs and their ability to chelate Fe(II) ions. In contrast, previous studies focused mainly on the interactions between Fe(II) ions and relatively low-molecular-weight tannins13,41,42,43, with little or no insight into structural details. The most common approach in the scientific literature for investigating interactions between polyphenols and Fe(II) ions (and other metal ions) is to conduct experiments at a specific pH value13,44,45. Models are then fitted separately to experimental data for each pH value to obtain apparent formation constants. While this method allows for the comparison of the affinities of ellagitannins for chelating metal ions at a given pH, it does not permit a comparison of results obtained at different pH values, nor does it provide a theoretical explanation for the observed changes in the formation constants. In contrast, the model used in this study facilitates the determination of the concentrations of unbound Fe(II) ions across the investigated pH range (with caution when extrapolating results outside this range), as it incorporates protolytic equilibrium to explain the pH-dependence of formation constants. Since chelation of Fe(II) ions occurs through deprotonated species of ETs, this simultaneously reduces the number of required experiments. Additionally, the developed model can describe chelation based on ET structural elements and can be used to predict the interactions of Fe(II) ions with the NHTP or HHDP groups of any ET. The knowledge gained can be used to plan a more sustainable approach in agriculture and, of course, also serve as a useful experimental approach in general chemistry, as the interactions between metal ions and polyphenols play an important role in the application of green chemistry.

Results and discussion

Protolytic equilibrium of roburin A and roburin D

Since the deprotonation of tannin is a crucial step in the formation of coordination compounds with Fe(II) ions40,46,47, the protolytic equilibrium of ROs was first investigated to determine their degree of deprotonation. The UV-Vis spectra of roburins (ROs) at different pH values are shown in Fig. 2. It can be seen that the spectra of roburin A (RO-A) (Fig. 2a) and roburin D (RO-D) (Fig. 2b) are very similar. At low pH values (red, bold curves in Fig. 2), where both ROs are present in neutral form, the spectra show a peak at 222 and a shoulder at \(\approx\)290 nm. In both ROs, the peak appears at a wavelength of 330 nm, which increases with pH. This pH-dependence is analogous to that observed for the other ellagitannins (ETs, vescalin - VI, castalin - CI, vescalagin - VG, and castalagin - CG) with identical structural units as ROs40. In addition, for both ROs the peak at 222 nm shifts to slightly longer wavelengths (\(\approx\)240 nm), while at the same time it becomes broader and decreases.

UV-Vis spectra of (a) RO-A and (b) RO-D at different pH values. The spectra at the lowest pH (3.51 for RO-A and 3.65 for RO-D) are represented by bold red curves, while the spectra at the highest pH (9.70 for RO-A and 9.91 for RO-D) are represented by bold blue curves. The largest changes are seen at 330, 260, and 230 nm. The fit of the model function (Eq. (1)) to the values at 260 nm is shown in the upper right corner of (a) and (b).

At the wavelengths where the largest changes occurred in the UV-Vis spectra (230, 260, and 330 nm), the absorbance values were extracted, converted to molar absorption coefficients using the Beer-Lambert law and compared with the values previously reported for smaller ETs40. Fig. 3 shows the molar absorption coefficients of the ROs as a function of pH at the listed wavelengths. In all cases, the changes in the molar absorption coefficients of the ROs occur at similar pH values, and there are only slight differences between RO-A and RO-D. At a wavelength of 330 nm (Fig. 3a), the differences in the molar absorption coefficients of the solutions are 3.54\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\)cm\(^{-1}\) and 3.51\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\)cm\(^{-1}\) for RO-A and RO-D, respectively. Comparing these values with those obtained in the previous study, being 1.83\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) and 1.74\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) for VG and CG, respectively40, it can be concluded that ROs release twice as many phenolic protons compared to VG and CG. This is to be expected since ROs consist of two VG (RO-A) and mixed VG-CG units (RO-D).

The same conclusion can also be drawn from the comparison at wavelengths of 260 and 230 nm (Fig. 3b, c). The differences in the molar absorption coefficients at \(\lambda =260\) nm were 1.75\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) and 1.79\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) for RO-A and RO-D, respectively, while at \(\lambda =230\) nm the observed differences in molar absorption coefficients were 6.57\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) and 6.17\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) for RO-A and RO-D. The comparison of these values with those for VG and CG at 260 nm (8.30\(\cdot 10^{3}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) and 7.47\(\cdot 10^{3}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\)) and at 230 nm (2.82\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) and 2.82\(\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\))40 again clearly shows that the number of protons exchanged in RO-A and RO-D is twice as high as the number of protons exchanged in VG and CG.

The spectral changes take place in the same pH range as in other ETs40. This was also confirmed by fitting the model function derived for the release of a single phenolic proton (Eq. (1)) to the absorbances obtained at a wavelength of 260 nm. It could be argued that fitting a function describing the exchange of a single proton to the data resulting from the exchange of multiple protons could be problematic. However, these protons are located in well-separated aromatic systems with large spatial separations and can therefore be considered independent. Fig. 2 shows the fit of the model (Eq. (1)) to the absorbance values for both ROs at a wavelength of 260 nm (upper right corner of Fig. 2a, b). The agreement is good in both cases and the obtained p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values are the average of all deprotonations of the most acidic phenolic protons (macroscopic p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values can be determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy, while microscopic values can be determined by \(^{13}\)C NMR – for VI, CI, VG, and CG see Ref39.). The average p\(K_\textrm{a,RO}\) values p\(K_\mathrm {a,RO-A}=6.66\) and p\(K_\mathrm {a,RO-D}=6.83\) were calculated as the mean of two experimental data sets for each RO. The p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values determined are similar to those for VI, CI, VG and CG (6.31, 6.66, 6.79, and 6.74, respectively)40 and are similar to the p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values (6–9) of the most acidic phenolic protons of other polyphenols48. Among these compounds are structurally diverse tannins with lower molecular weights and model compounds, ranging from flavonoids (p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values 6.8–7.7)49,50, which form condensed tannins, to methyl gallate (p\(K_\textrm{a}\) 7.96)39, a constituent of gallotannins and ellagitannins, as well as ellagic acid (p\(K_\textrm{a}\) 6.76)51 and other ellagitannins, such as punicalagin, for which a p\(K_\textrm{a}\) of 6.64 was determined for the hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP) group52. It should be noted that the differences between the determined p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values are relatively small compared to the experimental error, which is estimated to be \(\pm ~0.25\) as the difference between two determinations. Better insight into the protolytic equilibrium of ROs, particularly regarding deprotonation positions, could be obtained from \(^{13}\)C NMR spectra; however, interpretation of these results is unreliable due to the large number of overlapping signals. Moreover, \(^{1}\)H NMR provides insufficient information about deprotonation positions, as few aromatic protons are present in the structures of roburins. However, similarities between smaller ETs, such as VI and VG (the same applies to CI and CG), demonstrate that the behaviour of the NHTP group is similar whether the HHDP group is bound to the glucose residue or not (the groups are well separated and only negligibly affect each other). Moreover, the UV-Vis experiment confirms this, as the protolytic equilibrium of ROs closely resembles that of VG and CG. That is, changes in spectra are twice as large (because the compounds are twice the size), and these changes occur in the same pH range. Based on the results of this work and the structural similarity of the compounds, it can be assumed that the p\(K_\textrm{a,ET}\) values determined with UV-Vis spectroscopy correspond to the same deprotonations for all analysed ETs. Therefore, the microscopic p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values determined for VG and CG39 can also be safely used to describe the protolytic equilibrium of RO-A and RO-D.

The NHTP group binds two, and the HHDP group binds a single Fe(II) ion

The chelating ability of iron(II) ions by ROs was investigated using Job’s method in combination with UV-Vis spectroscopy. The UV-Vis spectra of the formed RO–Fe(III) coordination compounds (bound Fe(II) ions rapidly oxidise to Fe(III) ions34) have a broad absorption peak between 400 and 800 nm (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). The resulting solutions are dark blue in colour (similar to smaller ETs40), which corresponds to metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT)46, as shown for Fe(II) chelation by gallic acid (GA). The maximum of the absorption band of the coordination compound is between 500 and 600 nm and depends on the RO-to-Fe(II) ratio (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online), which is consistent with other studied coordination compounds between polyphenols and iron ions40,46,48. Precipitation occurs at lower RO-to-Fe(II) ratios. The time dependence of the formation of the coordination compound was observed in these samples. Given the constant value of the absorbance of the coordination compound over a longer period of time (e.g., see Supplementary Fig. S3 online), it could be assumed that this absorbance indicates the maximum concentration of the coordination compound formed.

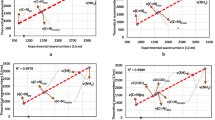

Fig. 4 shows the Job plots of RO-Fe(II) coordination compounds in the pH range 5.5–3.5. The following can be seen from both: (i) the absorbance of the coordination compound is highest at pH 5.5 and decreases at lower pH values (indicating the formation of a smaller amount of the coordination compound); (ii) each Job plot curve has a maximum at \(x_{\text {RO}}=0.20\)–0.30; (iii) at a given pH, approximately the same absorbances can be observed in RO-A and RO-D solutions for all compositions (the differences are within the experimental error), indicating that a similar amount of coordination compound is formed and that the difference in the stereoconfiguration of the ROs has no effect on the formation of coordination compounds. These observations are similar to those for coordination compounds of smaller ETs and Fe(II) ions40.

Job plots for coordination compounds of Fe(II) ions and: (a) RO-A (red diamonds for pH 5.5, black right-pointing triangles for pH 4.5, orange rectangles for pH 3.5) and (b) RO-D (blue circles for pH 5.5, green left-pointing triangles for pH 4.5, purple down-pointing triangles for pH 3.5). (c) Comparison of the Job plot curves for coordination compounds of Fe(II) ions and GA46 (grey right-pointing triangles), VI (black down-pointing triangles), CI (purple left-pointing triangles), VG (orange rectangles), CG (green up-pointing triangles)40, RO-A (red diamonds), and RO-D (blue circles) at pH 5.5 (the absorbance values were converted to the concentration of \(c=2\cdot 10^{-4}\text { mol}~\text {L}^{-1}\text {)}\).

Fig. 4c shows a comparison of the Job plots for tannin–iron(II) coordination compounds at pH 5.5: GA46, ETs (VI, CI, VG, CG of the previous study40, and RO-A, RO-D of the present study (the absorbance values for VI, CI and CG were converted to the concentrations used in the current study (\(c=2\cdot 10^{-4}\text { mol}~\text {L}^{-1}\text {)}\). A similar absorption is found in solutions with a higher molar fraction of ET (high x values), where the concentration of Fe(II) ions is the limiting factor. However, in solutions with an excess of Fe(II) ions (\(x<0.5\)), the difference between the absorbance values of the different ETs is more pronounced. As explained in reference40, VG and CG can chelate three Fe(II) ions due to an additional HHDP group, compared to the two chelated by VI and CI. This leads to a change in the position of the absorption maximum in the Job plot and to higher values of the absorption maximum. The molecules of RO-A and RO-D are twice as large as those of VG and CG, so that an even stronger shift of the maximum of the Job plot to smaller x values in connection with even higher absorbance values naturally follows.

The stoichiometries of the formed coordination compounds were determined from the intersection of the extrapolations of the outermost points of the individual Job curves (see Supplementary Fig. S4 online). The x values (\(x_{\text {RO}}\)) obtained for the intersection point are between 0.15 and 0.16 for both ROs. In addition, the molar absorption coefficients of the coordination compounds \(\epsilon _{\text {extrapolated, ET}}\) were estimated from the y-coordinates of the intersection point. All values are listed in the Supplementary Table S1 online. The x-axis position of the intersection indicates that the stoichiometry is between 1:5 and 1:6 (RO:Fe)53. However, a comparison of the average molar absorption coefficients of ROs with the absorption coefficients of other previously investigated ETs40 gives the stoichiometry of 1:6 (RO:Fe), as the ratios of the absorption coefficients VI:CI:VG:CG:RO-A:RO-D = 2.0:2.0:2.8:2.9:6.4:6.3 were obtained. This confirms that VI (or CI) chelates two Fe(II) ions, VG (or CG) chelates three Fe(II) ions, and RO-A (or RO-D) chelates six Fe(II) ions. This also agrees well with the fact that the size of RO-A and RO-D is twice that of VG or CG, so their ability to chelate twice as many metal ions as VG or CG naturally follows. Moreover, the absorption coefficient of a single metal centre in a RO-Fe(II) coordination compound (\(\overline{\epsilon }_{\text {extrapolated, RO}}\cdot 6^{-1}\)) is of the expected order of 1\(\cdot 10^{3}\text { L}~\text {mol}^{-1}~\text {cm}^{-1}\)40,48.

Towards explanation of the ellagitannin–Fe(II) interactions

To describe the chelating ability of the (nonahydroxytriphenoyl) NHTP and (hexahydroxydiphenoyl) HHDP groups of ETs, we developed a model function that we fitted to the Job plots. For this purpose, we used the Job plots of ETs from our previous study40(VI, CI, VG, and CG), which we fitted simultaneously with the function defined by Eq. (3) (global fit). In this model, the ETs were described as a set of three types of independent binding sites (NHTP-A, NHTP-B, and HHDP, see Fig. 5) for Fe(II) ions. The model is based on the determined stoichiometries of the formed coordination compounds (the NHTP group binds two Fe(II) ions, while the HHDP group binds a single Fe(II) ion) and on the microscopic protolytic equilibrium of ETs39, which gives the molar fraction of reactive binding sites (calculated with Eq. (2)) and their most probable binding positions (chelation of Fe(II) ions occurs after deprotonation of the hydroxyl group)46,54. The positions of the binding sites are based on the microscopic protolytic equilibrium of the ETs, which was previously determined by \(^{13}\)C NMR spectroscopy39. On this basis, the most probable binding positions on the aromatic rings I, III, and V were determined for the hydroxyl groups at positions 4’ and 5’ (see Fig. 5). It should be noted that in the case of aromatic ring I, the chelation of the Fe(II) ion occurs either through the hydroxyl groups 4’ and 5’ or through the hydroxyl groups 4’ and 3’ (another hydroxyl group adjacent to the 4’ group), whereby only the first option is shown in Fig. 5.

Proposed Fe(II) ion binding sites of ETs and the corresponding chelation reactions. The NHTP group has two binding sites (NHTP-A and NHTP-B, shown in blue and red, respectively), while the HHDP group has a single binding site (shown in purple). The positions of the binding sites are based on the microscopic protolytic equilibrium of the ETs, which was previously determined by \(^{13}\)C NMR spectroscopy39.

Fig. 6 shows the model fit to ET–Fe(II) Job plots at pH 4.5 (the comparison for all pH values can be found in the Supplementary Fig. S5–S9 online). It can be seen that the agreement between the experimental and model values is very good, especially considering that only four fitting parameters (\(\epsilon _\textrm{model}\), \(K_\mathrm {f,NHTP-A}\), \(K_\mathrm {f,NHTP-B}\), and \(K_\textrm{f,HHDP}\)) were used to describe the system. Their values, which result from fitting the model, are listed in Table 1.

Fit of the model function (Eq. (3)) to the experimental data of the Job plots at pH 4.5 for Fe(II) ions and ETs: (a) VI, (b) CI, (c) VG, (d) CG, (e) RO-A, and (f) RO-D. The model curves show the global fit to four ETs (VI, CI, VG, and CG), where the model values for RO-A and RO-D were calculated using the adjustable parameters resulting from fitting the model to the remaining four ETs.

We then investigated how well the parameters obtained are suitable for describing the coordination compounds of ROs and Fe(II) ions. Firstly, the \(\epsilon _\textrm{model}\) value obtained can be compared with the value determined experimentally from the intersection of the extrapolations. Assuming that the absorption coefficient determined from the model is due to a single metal centre, the total absorption coefficient of the coordination compounds of ROs is \(6\cdot \epsilon _\textrm{model}=2.50\cdot 10^{4}\) L mol\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\), which is in excellent agreement with the experimental values (see Table S3). Moreover, according to the similar UV-Vis data reported in the section Protolytic equilibrium of RO-A and RO-D, one would expect the microscopic p\(K_\textrm{a}\) constants of ROs to be equal to the corresponding p\(K_\textrm{a}\) constants of VG or CG39. In conjunction with the model parameters, this facilitates the calculation of the model Job curves for RO-A and RO-D. The comparison between calculated and experimental curves at a pH of 4.5 is shown in Fig. 6e, f (for the entire investigated pH range see Supplementary Fig. S5–S9 online). The described model was also fitted simultaneously (global fit) to the Job plots of all six ETs analysed (for ROs, the Eq. (3) contained four terms for the NHTP group and two terms for the HHDP group). The model fits were similar to those using Job plots of the four ETs analysed (see Supplementary Fig. S5–S9 online). The fitting parameters resulting from the globally fitted model for the Job plots of the six ETs analysed are listed in Supplementary Table S2 online.

It can be seen that the model describes the experimental values very well. This result is of utmost importance to confirm the validity of the model and to demonstrate its predictive power. When we combine the data from our previous studies39,40,46 with the model presented here, we can confidently predict the stoichiometries of Fe(II) ion coordination compounds with ETs consisting of HHDP and NHTP groups. However, ET compounds consisting exclusively of these two groups are relatively rare – in addition to the compounds investigated here, these include roburins A-E, grandinin, castaneanin D, casuariin, etc.55. Therefore, analogue studies should be performed on ETs with additional groups, e.g., galloyl groups, valoneoyl groups, flavanol units, etc., in order to gain a complete insight into the interactions of ETs with Fe(II) ions and to cover as broad a spectrum of compounds as possible. Furthermore, the ETs studied have relatively rigid structures, while the interactions of more flexible compounds with Fe(II) ions can be additionally complicated, as several groups can chelate a single metal centre.

Furthermore, the application of the model facilitates the estimation of the amounts of Fe(II) ions in the prepared solutions that are not bound in coordination compounds. Fig. 7 shows a comparison of the model equilibrium molar concentrations of unbound Fe(II) ions (\([\text {Fe(II)]}\)) for a series of solution samples at a) pH 5.5 and b) pH 4.5. In addition to the values determined for ETs, Fig. 7 also shows \([\text {Fe(II)]}\) values determined for the reaction of GA with Fe(II) ions46. Fig. 7 shows that ROs chelates the most Fe(II) ions, VG and CG chelate significantly less (their values are similar), while VI and CI chelate the least amount of Fe(II) ions. Compared to ETs, GA chelates a much smaller amount of Fe(II) ions from solution. The observations are also similar for solutions at other pH values investigated. These results are consistent with the number of bound Fe(II) ions determined by extrapolation of the Job plot. These calculations can be used, for example, to estimate the ability of tannins to deplete essential metal ions while determining the antibacterial activity of tannins18. However, it should be noted that these measurements were performed in the pH range of 5.5–3.5, while the MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values are normally determined at a pH close to 7. Additionally, as the predominant species of the studied ETs is in the neutral state within this pH range39,40, only minor differences in Job plots are observed between measurement sets (Fig. 4). At pH values above the investigated 5.5, ellagitannins and their model compounds oxidise more rapidly and are less stable56,57,58. Moreover, at higher pH values, several issues will arise due to the presence of oxidation products. The main aim of this study was to investigate the mechanisms of these compounds. For model evaluation, pure compounds were required, unlike studies in which tannin extracts are tested for their general interactions with iron59,60,61. Additional oxidation or hydrolysis products at higher pH values would make investigation with Fe(II) ions impossible, as we would not be able to assign all contributions to the respective chemical species, and investigating the mechanisms would be even more difficult. Consequently, the developed model should be used with caution outside the investigated pH range. To gain better insight into interactions between ETs and iron ions, the same experiments with Fe(III) ions would need to be conducted. However, significant experimental problems arise when Fe(III) ions are used, as pronounced and immediate precipitation occurs in solutions with ETs under the same experimental conditions as with Fe(II) ions (Supplementary Fig. S10 online). This limits experiments with Fe(III) compared to those with Fe(II) ions.

Dependence of the molar equilibrium concentration of unbound Fe(II) ions (\([\text {Fe(II)}]\)) on the composition of the solution for (a) pH 5.5 and (b) pH 4.5, determined by the model developed for the reactions of Fe(II) ions and tannins: GA (grey solid curve), VI (black dashed curve), CI (purple solid curve), VG (orange dotted curve), CG (green solid curve), RO-A (red dashed curve), and RO-D (blue dotted curve).

Conclusions

This work provides crucial insights into the interactions of high-molecular-weight ellagitannins (ETs) with Fe(II) ions. First, it was shown that the protolytic equilibrium in a solution of roburin A (RO-A) and roburin D (RO-D) is very similar to the equilibrium in solutions of vescalagin (VG) and castalagin (CG)40, with the main difference being the number of possible deprotonation sites. In addition, the stoichiometry of the RO–Fe(II) coordination compound was determined, indicating that the mechanism of chelation is the same as in the aqueous solutions of vescalin (VI), castalin (CI), VG, and CG. Based on the data on deprotonation of ETs from our previous study39, we developed a new model describing the coordination compounds of Fe(II) ions in terms of the contribution of the nonahydroxytriphenoyl (NHTP) and hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP) groups. First, we determined the apparent formation constants of the coordination compound by fitting only the VI, CI, VG, and CG data. The determined model parameters were then used to calculate the model Job plot curves for RO-A and RO-D. The good agreement between the experimental and model results shows that the developed model facilitates the prediction of the chelating ability of Fe(II) ions by each ET consisting of NHTP and HHDP groups. This provides a strong predictive tool for determining the interactions of ET NHTP and HHDP groups with Fe(II) ions. However, studies on other structural elements of ETs are required to gain a complete insight into Fe(II)–ET interactions and thus a better understanding of the antibacterial mechanisms of ETs, which could ultimately facilitate a more effective application of tannins as feed additives, leading to sustainable agriculture and the application of green chemistry.

Methods

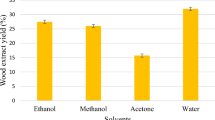

Isolation and characterisation of roburin A and roburin D

From the commercial aqueous chestnut extract Farmatan (Tanin Sevnica d.d., Sevnica, Slovenia), roburin A (RO-A) and roburin D (RO-D) were isolated. A chromatogram of the aqueous chestnut extract, in which the peaks of RO-A and RO-D are labelled, can be found in the Supplementary Fig. S11 online. The isolation was performed in a similar manner to the isolation of other ellagitannins (ETs) described in our previous studies (vescalin - VI, castalin - CI40, vescalagin - VG, castalagin - CG18). The preparative HPLC instrument PuriFlash 5.250 (Interchim, Montluçon, France) equipped with a PDA and ELSD detector was used for the isolation. First, separation was performed on the stationary phase Sephadex-LH2018, followed by purification on the flash reverse phase C18 column (PF-50C18HP-F0040, Interchim, Montluçon, France)40 and finally the ROs were obtained with sufficient purity after separation on the Prep-HPLC reverse phase C18 column US10C18HQ-250/212 (Interchim, Montluçon, France)40.

After freeze-drying, both ROs were obtained as amorphous, off-white powders. The chromatographic purity of the ROs was determined to be 96% (chromatographs of RO-A and RO-D are shown in Supplementary Fig. S12 online). The ROs were characterised by comparison of retention times with those of standards (HPLC chromatography with UV-Vis detection) and by NMR analysis (Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz NMR spectrometer, Bruker, Billerica, USA). The NMR spectra were measured directly after sample preparation in 5 mm NMR tubes (SP Wilmad-Labglass, Vineland, USA). Bruker Topspin 4.2.0 (Bruker, Billerica, USA) was used to acquire and process the NMR spectra. \(^1\)H NMR spectra were recorded for samples prepared in \(\text {D}_2\text {O}\), using a standard pulse sequence from the Bruker library (zgesgp). The obtained \(^1\)H NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. S13 online) are in good agreement with those reported in the scientific literature62.

RO-A: \(^1\)H NMR [600 MHz, D\(_2\)O] \(\delta\) 7.49 (s, 1H); 7.15 (s, 1H); 6.84 (s, 1H); 6.83 (s, 1H); 6.66 (s, 1H); 5.42 (d, 1H, \(J=7.38\) Hz); 5.30 (d, 1H, \(J=6.78\) Hz); 5.24 (s, 1H); 5.11 (m, 3H); 4.88 (s, 1H); 4.85 (s, 1H); 4.74 (d, 1H); 4.60 (d, 1H); 4.29 (d, 1H, \(J=12.06\) Hz); 4.11 (d, 1H, \(J=12.06\) Hz); 2.78 (d, 1H, \(J=12.30\) Hz).

RO-D: \(^1\)H NMR [600 MHz, D\(_2\)O] \(\delta\) 7.50 (s, 1H); 7.15 (s, 1H); 6.83 (s, 1H); 6.80 (s, 1H); 6.66 (s, 1H); 5.67 (d, 1H, \(J=4.70\) Hz); 5.41 (d, 1H, \(J=7.04\) Hz); 5.28 (d, 1H, \(J=6.75\) Hz); 5.24 (s, 1H); 5.13 (t, 1H); 5.11 (t, 1H); 5.09 (m, 2H); 5.06 (m, 1H); 4.86 (s, 1H); 4.60 (d, 1H); 4.28 (d, 1H, \(J=12.03\) Hz); 4.11 (d, 1H, \(J=12.03\) Hz); 2.76 (d, 1H, \(J=12.62\) Hz).

UV-Vis determination of roburin protolytic equilibrium

Absorbance values were measured using a Cary 4000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) equipped with a thermostated multicell holder (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). The UV-Vis spectra were measured in the wavelength range between 800 and 200 nm in a 1 cm quartz cuvette (1 nm measurement step and 0.2 s averaging time). Type I water (\(\sigma\) = 0.055 \(\upmu \textrm{S}~\textrm{cm}^{-1}\)) was used for the experiments, and all measurements were performed at 298.15 K. The Metrohm 780 pH Meter and a combined BioTrode electrode (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland) were used to measure the pH values.

The protolytic equilibrium of ROs was determined in the same way as described in our previous study40. The initial concentration of ROs was \(c_{\text {RO}}=\) 8.00\(\cdot 10^{-6}\) mol L\(^{-1}\). Significant changes in absorbance values at 260 nm were fitted with the model (Eq. (1)) derived for a protolytic equilibrium where a single proton is released (chemical equilibrium between dissociated (RO\(^-\)) and non-dissociated roburin (HRO))40,63. In Eq. (1) the dissociation constant (\(K_\textrm{a,RO}\)) and the molar absorption coefficients of the deprotonated and neutural species (\(\epsilon _{\text {RO}^{-}}\), \(\epsilon _{\text {HRO}}\)) are fitting parameters, while \(c_{\text {RO}}\) denotes the total molar concentration of RO, b the length of the optical path (1 cm) and \(\text {[H}_{3}\text {O}^{\text {+}}\text {]}\) the molar concentration of oxonium ions.

Job plot experiments

Job plots samples of isolated ROs (\(2\cdot 10^{-3}\text {~mol}~\text {L}^{-1}\)), Fe(II) ions, and acetate buffers were prepared in the same way as described in the previous study40. Solution of Fe(II) ions was prepared right before the experiment, to ensure that iron ions are in the state \(+2\) during the execution of the experiment. Sample sets were prepared in an acetate buffer (\(5\cdot 10^{-2}\text { mol}~\text {L}^{-1}\)) at three different pH values (5.5, 4.5, and 3.5). The sets contained 25 samples. The sum of the concentrations of ROs and Fe(II) ions (c) was the same for all samples (\(2\cdot 10^{-4}\text { mol}~\text {L}^{-1}\text {)}\). The achieved equilibrium of chelation reactions was confirmed by obtaining identical successive UV-Vis spectra. The stoichiometries of the coordination compounds were determined by extrapolation of the left and right endpoints of the Job plots. Fe(III) ions used for preliminary tests of interactions with ETs were prepared from iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (Honeywell Fluka, Muskegon, USA).

Model fitting

Following our previous studies on the formation of coordination compounds between Fe(II) ions and tannins40,46 and on the protolytic equilibrium of ETs39, a model (Fig. 5) was developed that describes the reaction between ETs consisting of nonahydroxytriphenoyl (NHTP) or hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP) groups and Fe(II) ions. The model treats each NHTP group as two independent binding sites (NHTP-A and NHTP-B), while HHDP represents an additional independent binding site for Fe(II) ions (see Fig. 5). Consequently, each ET is represented as a series of independent Fe(II) ion binding sites (VI and CI as NHTP-A and NHTP-B; VG and CG as NHTP-A, NHTP-B, and HHDP; RO-A and RO-D as 2\(\times\)NHTP-A, 2\(\times\)NHTP-B, and 2\(\times\)HHDP). Each binding site is present as a non-reactive binding site (NHTP-A\(_\textrm{N}\), NHTP-B\(_\textrm{N}\), and HHDP\(_\textrm{N}\)) or as a reactive binding site (NHTP-A\(_\textrm{R}\), NHTP-B\(_\textrm{R}\), and HHDP\(_\textrm{R}\)). Each bound Fe(II) ion is most likely additionally coordinated with four \(\text {H}_{2}\text {O}\) molecules, as shown in our previous study for the model tannin compound (GA)46. A coordination number of six is typical for the coordination compounds of iron ions64. The molar fraction of reactive binding sites (\(x_{\mathrm {binding~site,R}}\)) is determined by the microscopic protolytic equilibrium of the investigated ETs39, according to Eq. (2) (see Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 online for the p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values of the hydroxyl groups used and the calculated molar fractions).

Here \(K_\text {a}\) denotes the first dissociation constant of the phenolic proton of the binding site, while \(\text {[H}_{3}\text {O}^{\text {+}}\text {]}\) denotes the molar concentration of the oxonium ions in solution. The p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values considered for the calculations were for the hydroxyl group at position 4’ (Fig. 5) on aromatic ring I, the hydroxyl group at position 5’ on aromatic ring III, and the hydroxyl group at position 5’on aromatic ring V for the binding sites NHTP-A, NHTP-B, and HHDP, respectively (see article in Ref39.). In the case of the HHDP binding site, either of the 5’ hydroxyl groups of aromatic rings IV or V is equally likely for chelation, as the differences in the respective p\(K_\textrm{a}\)values are negligible (0.01, see article in Ref39.), but aromatic ring V was selected due to its lower values. The p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values and the corresponding molar fractions for all binding sites are listed in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 online. For RO-A and RO-D, the same molar fractions were taken as the ones calculated for VG or CG due to structural similarities and similar changes in their UV-Vis spectra with pH. It should be noted that in the case of aromatic ring I, the chelation of the Fe(II) ion is either through 4’ and 5’ hydroxyl groups or by 4’ and 3’ hydroxyl groups (another hydroxyl group adjacent to the 4’ group), whereby only the first option is shown in Fig. 5.

\(K_{\text {f,NHTP-A}}\), \(K_{\text {f,NHTP-B}}\) and \(K_{\text {f,HHDP}}\) denote the apparent formation constants of coordination compounds \([\text {NHTP-A}_{\text {R}}\text {Fe(II)}]\), \([\text {NHTP-B}_{\text {R}}\text {Fe(II)}]\) and \([\text {HHDP}_{\text {R}}\text {Fe(II)}]\), respectively. Finally, as demonstrated by Nkhili et al.34, the bound Fe(II) ions oxidise to Fe(III) ions, enabling the detection of coordination compounds due to their intense blue colouration48. Nkhili et al.34 also showed that the chelation of Fe(II) ions is significantly faster than autooxidation. Additionally, under identical experimental conditions, we have previously confirmed that oxidation of the initial solution does not occur46. Finally, due to chemical similarities and to avoid over-parameterisation, it was assumed that the molar absorption coefficient \(\epsilon\) is the same for all three binding positions.

All equations describing the equilibrium concentrations of the individual species were then derived from the model scheme and inserted into the model function of absorption by the formed coordination compound (\(A_{\text {model}}\)). The resulting function, defined by the Eq. (3), was simultaneously fitted to the experimental absorbance values of all Job plots obtained in our previous study46. The bold part of the Eq. (3) was fitted to the Job plots of VI and CI, while the entire Eq. (3) was fitted to the remaining Job plots.

In Eq. (3) b denotes the optical path length (1 cm), \(\epsilon _{\text {model}}\) denotes the model molar absorption coefficient of a coordination compound (for a single bound Fe(II) ion), while the square brackets indicate the equilibrium molar concentrations of a particular species. Model fitting was performed by applying the differential evolution algorithm and the least squares method. The error of the adjustable parameters (\(\epsilon _{\text {model}}\), \(K_{\text {f,NHTP-A}}\), \(K_{\text {f,NHTP-B}}\), and \(K_{\text {f,HHDP}}\)) was estimated using the bootstrapping method with 100 replicates, assuming a random variation of the experimental data (Job plot absorbance values and molar fractions of reactive binding sites) in the order of \(\pm ~10.0\%\) was assumed, based on the experimental errors of the measured absorbance values and the estimated errors of the determined p\(K_\textrm{a}\) values for ETs. The error was then determined as the standard deviation of the adjustable parameters for varied experimental data. The obtained adjustable parameters were then used for calculations of Job plots for ROs for comparison with the experimental data.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CG:

-

Castalagin

- CI:

-

Castalin

- ET:

-

Ellagitannin

- HHDP:

-

Hexahydroxydiphenoyl

- NHTP:

-

Nonahydroxytriphenoyl

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- RO-A:

-

Roburin A

- RO-D:

-

Roburin D

- VG:

-

Vescalagin

- VI:

-

Vescalin

References

Laxminarayan, R. et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 1057–1098 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9 (2013).

Xu, C., Kong, L., Gao, H., Cheng, X. & Wang, X. A review of current bacterial resistance to antibiotics in food animals. Front. Microbiol. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.822689 (2022).

Lillehoj, H. et al. Phytochemicals as antibiotic alternatives to promote growth and enhance host health. Vet. Res. 49, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-018-0562-6 (2018).

Founou, L. L., Amoako, D. G., Founou, R. C. & Essack, S. Y. Antibiotic Resistance in Food Animals in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Drug Resist. 24, 648–665 https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2017.0383 (2018).

Bell, B. G., Schellevis, F., Stobberingh, E., Goossens, H. & Pringle, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-13 (2014).

Yu, W., Zhan, S., Shen, Z., Zhou, Q. & Yang, D. Efficient removal mechanism for antibiotic resistance genes from aquatic environments by graphene oxide nanosheet. J. Chem. Eng. 313, 836–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.107 (2017).

Tao, C.-W. et al. Evaluation of Five Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Wastewater Treatment Systems of Swine Farms by Real-Time PCR. Sci. Total Environ. 496, 116–121 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.024 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Simultaneous reduction of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in pig manure using a composting process with a novel microbial agent. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111724 (2021).

Farha, A. K. et al. Tannins as an alternative to antibiotics. Food Biosci. 38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100751 (2020).

Serrano, J., Puupponen-Pimiä, R., Dauer, A., Aura, A.-M. & Saura-Calixto, F. Tannins: Current knowledge of food sources, intake, bioavailability and biological effects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53, S310–S329 https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200900039 (2009).

Dobreva, M. A. et al. Size and molecular flexibility affect the binding of ellagitannins to bovine serum albumin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 9186–9194 https://doi.org/10.1021/jf502174r (2014).

Sekowski, S., Buczkowski, A., Palecz, B. & Abdulladjanova, N. Inhibitory Effect of Euphorbia tannins on \(\alpha\)-synuclein aggregation in aqueous solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 299, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112112 (2020).

Zhang, H., Zhang, L., Tang, L., Hu, X. & Xu, M. Effects of metal ions on the precipitation of Penta-O-galloyl-\(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose by protein. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 69, 5059–5066 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01185 (2021).

Schmidt, M. A., Gonzalez, J. M., Halvorson, J. J. & Hagerman, A. E. Metal Mobilization in Soil by Two Structurally Defined Polyphenols. Chemosphere 90, 1870–1877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.10.010 (2013).

Zeng, X., Du, Z., Sheng, Z. & Jiang, W. Characterization of the interactions between banana condensed tannins and biologically important metal ions (\(\rm C\)u\(^{2+}\), \(\rm Z\rm\)n\(^{2+}\) and \(\rm F\)e\(^{2+}\)). Food Res. Int. 123, 518–528 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.04.064 (2019).

Zhang, L., Guan, Q., Zhang, H., Tang, L. & Xu, M. A spectroscopic and quantum chemical calculation method for the characterisation of metal ions complexed with propyl gallate and procyanidins. Sci. Rep. 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30186-x (2023).

Tošović, J. & Bren, U. Antioxidative action of ellagic acid-A kinetic DFT study. Antioxidants 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9070587 (2020).

Štumpf, S. et al. The effect of growth medium strength on minimum inhibitory concentrations of tannins and tannin extracts against E. coli. Molecules 25, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25122947 (2020).

Štumpf, S. et al. The Influence of chestnut extract and its components on antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Plants 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12102043 (2023).

Hostnik, G., Gladović, M. & Bren, U. Tannin basic building blocks as potential scavengers of chemical carcinogens: A computational study. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 3279–3287. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00435 (2019).

Chung, K., Wong, T., Wei, C., Huang, Y. & Lin, Y. Tannins and human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 38, 421–464 https://doi.org/10.1080/10408699891274273 (1998).

Melo, M. J. et al. Iron-Gall Inks: a Review of their degradation mechanisms and conservation treatments. Herit. Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00779-2 (2022).

Maier, M., Oelbermann, A.-L., Renner, M. & Weidner, E. Screening of european medicinal herbs on their tannin content new potential tanning agents for the leather industry. Ind Crops Prod 99, 19–26 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.01.033 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. Development of tannin-inspired antimicrobial bioadhesives. Acta Biomater. 72, 35–44 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.03.008 (2018).

Yin, C.-Y. Emerging usage of plant-based coagulants for water and wastewater treatment. Process Biochem 45, 1437–1444 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2010.05.030 (2010).

Hassanat, F. & Benchaar, C. Assessment of the effect of condensed (Acacia and Quebracho) and hydrolysable (chestnut and valonea) tannins on rumen fermentation and methane production in vitro. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 332–339 https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.5763 (2013).

Mueller-Harvey, I. Unravelling the conundrum of tannins in animal nutrition and health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 86, 2010–2037 https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2577 (2006).

Bag, A., Bhattacharyya, S. K. & Chattopadhyay, R. R. Isolation and identification of a gallotannin 1,2,6-tri-O-galloyl-\(\beta\)-D-glucopyranose from hydroalcoholic extract of terminalia chebula fruits effective against multidrug-resistant uropathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115, 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12256 (2013).

Araújo, A. R., Araújo, A. C., Reis, R. L. & Pires, R. A. Vescalagin and castalagin present bactericidal activity toward methicillin-resistant bacteria. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 1022–1030 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01698 (2021).

Trentin, D. S. et al. Tannins possessing bacteriostatic rffect impair Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesion and biofilm formation. PLoS One 8, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066257 (2013).

Weinberg, E. Cellular regulation of iron assimilation. Q. Rev. Biol. 64, 261–290 https://doi.org/10.1086/416359 (1989).

Akiyama, H., Fujii, K., Yamasaki, O., Oono, T. & Iwatsuki, K. Antibacterial action of several tannins against staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/48.4.487 (2001).

Mila, I., Scalbert, A. & Expert, D. Iron withholding by plant polyphenols and resistance to pathogens and rots. Phytochemistry 42, 1551–1555 https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(96)00174-4 (1996).

Nkhili, E., Loonis, M., Mihai, S., El Hajji, H. & Dangles, O. Reactivity of food phenols with iron and copper ions: binding, dioxygen activation and oxidation mechanisms. Food Funct. 5, 1186–1202 https://doi.org/10.1039/C4FO00007B (2014).

Khanbabaee, K. & van Ree, T. Tannins: classification and definition. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18, 641–649 https://doi.org/10.1039/b101061l (2001).

Clifford, M. & Scalbert, A. Ellagitannins-nature, occurrence and dietary burden. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80, 1118–1125 https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(20000515)80:7\(<\)1118::AID-JSFA570\(>\)3.3.CO;2-0 (2000).

Natella, F. et al. Absorption, metabolism, and effects at transcriptome level of a standardized french oak wood extract, robuvit, in healthy volunteers: Pilot study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 443–453 https://doi.org/10.1021/jf403493a (2014).

Matsuo, Y., Wakamatsu, H., Omar, M. & Tanaka, T. Reinvestigation of the stereochemistry of the C-glycosidic ellagitannins, vescalagin and castalagin. Org. Lett. 17, 46–49 https://doi.org/10.1021/ol503212v (2015).

Frešer, F., Zalar, M., Bren, U. & Hostnik, G. Determining microscopic dissociation constants of polyprotic polyphenols using NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Chim. Acta 1369, 344316 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2025.344316 (2025).

Frešer, F., Bren, U. & Hostnik, G. Chelation of iron(II) ions by ellagitannins-effects of hexahydroxydiphenoyl and nonahydroxytriphenoyl groups. Spectrochim. Acta A 313, 124079 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2024.124079 (2024).

Powell, H. & Taylor, M. Interactions of iron(II) and iron(III) with gallic acid and its homologues - a potentiometric and spectrophotometric study. Aust. J. Chem. 35, 739–756 https://doi.org/10.1071/CH9820739 (1982).

Buffle, J. & Martell, A. E. Metal ion catalyzed oxidation of o-dihydroxy aromatic compounds by oxygen. 2. Complexes of 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene-4-sulfonate with iron(III) and iron(II). Inorg. Chem. 16, 2225–2229 https://doi.org/10.1021/ic50175a014 (1977).

Binbuga, N., Chambers, K., Henry, W. P. & Schultz, T. P. Metal chelation studies relevant to wood preservation.1. Complexation of propyl gallate with \(\rm F\)e\(^{2+}\). Holzforschung 59, 205–209 https://doi.org/10.1515/HF.2005.032 (2005).

Perez, C. A., Wei, Y. & Guo, M. Iron-binding and anti-Fenton properties of baicalein and baicalin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 103, 326–332 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.11.003 (2009).

Zhang, L. et al. aluminum complex formation: Implications for aluminum tolerance in plants. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 64, 3025–3033 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00331 (2016).

Frešer, F., Hostnik, G., Tošović, J. & Bren, U. Dependence of the Fe(II)-gallic acid coordination compound formation constant on the pH. Foods 10, 2689 https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112689 (2021).

Caterino, S. et al. A systematic multianalytical approach in the study of iron-polyphenolic complexes in iron-gall inks: Exploring the potentialities of raman and electron paramagnetic resonance. Inorg. Chem. 64, 4802–4816 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c04232 (2025).

Perron, N. R. & Brumaghim, J. L. A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 53, 75–100 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-009-9043-x (2009).

Fuguet, E., Ràfols, C., Mañé, M., Ruiz, R. & Bosch, E. Acidity constants of hydroxyl groups placed in several flavonoids: Two flavanones, two flavones and five flavonols. Talanta 253, 124096 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2022.124096 (2023).

Inoue, M. B., Inoue, M., Fernando, Q., Valcic, S. & Timmermann, B. N. Potentiometric and \(^{1}\)\({{\rm {H}}}\)\({{\rm {NMR}}}\) studies of complexation of \({{\rm {A}}}\)l\(^{3+}\) with (-)-epigallocatechin gallate, a major active constituent of green tea. J. Inorg. Biochem. 88, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0162-0134(01)00323-3 (2002).

Simić, A. Z. et al. Study of ellagic acid electro-oxidation mechanism. Monatsh. fur Chem. 144, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-012-0856-8 (2013).

Kraszni, M., Marosi, A. & Larive, C. K. NMR assignments and the acid-base characterization of the pomegranate ellagitannin punicalagin in the acidic pH-range. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 5807–5816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-013-6987-x (2013).

Renny, J. S., Tomasevich, L. L., Tallmadge, E. H. & Collum, D. B. Method of continuous variations: Applications of job plots to the study of molecular associations in organometallic chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11998–12013 https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201304157 (2013).

Perron, N. R., Hodges, J. N., Jenkins, M. & Brumaghim, J. L. Predicting how polyphenol antioxidants prevent DNA damage by binding to iron. Inorg. Chem. 47, 6153–6161 https://doi.org/10.1021/ic7022727 (2008).

Jourdes, M., Pouységu, L., Deffieux, D., Teissedre, P.-L. & Quideau, S. Hydrolyzable tannins: Gallotannins and ellagitannins. Nat. Prod. 1975–2010, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22144-6_65 (2013).

Tuominen, A. & Sundman, T. Stability and oxidation products of hydrolysable tannins in basic conditions detected by HPLC/DAD–ESI/QTOF/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 24, 424–435 https://doi.org/10.1002/pca.2456 (2013).

Sójka, M., Janowski, M. & Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K. Stability and transformations of raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) ellagitannins in aqueous solutions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 245, 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3212-3 (2019).

Hostnik, G., Tošović, J., Štumpf, S., Petek, A. & Bren, U. The influence of pH on UV/Vis spectra of gallic and ellagic acid: A combined experimental and computational study. Spectrochim. Acta A 267, 120472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2021.120472 (2022).

Zelinka, S. L. & Stone, D. S. The effect of tannins and pH on the corrosion of steel in wood extracts. Mater. Corros. 62, 739–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.201005845 (2011).

Palma, G., Freer, J. & Baeza, J. Removal of metal ions by modified Pinus radiata bark and tannins from water solutions. Water Res. 37, 4974–4980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2003.08.008 (2003).

Karamać, M. Chelation of Cu(II), Zn(II), and Fe(II) by tannin constituents of selected edible nuts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 5485–5497 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10125485 (2009).

Glabasnia, A. & Hofmann, T. Sensory-directed identification of taste-active ellagitannins in American (quercus alba L.) and European oak wood (quercus robur L.) and quantitative analysis in bourbon whiskey and oak-matured red wines. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 54, 3380–3390 https://doi.org/10.1021/jf052617b (2006).

Rios Martínez, C. H. & Dardonville, C. Rapid determination of ionization constants (pKa) by UV spectroscopy using 96-well microtiter plates. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 142–145 https://doi.org/10.1021/ml300326v (2013).

Housecroft, C. & Sharpe, A. Inorganic Chemistry (Pearson Deutschland, 2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of research equipment Cary 4000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, procured within the project “Upgrading national research infrastructures - RIUM”, which was co-financed by the Republic of Slovenia, the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation and the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund. The authors would like to thank the Slovenian NMR centre at the National Institute of Chemistry for the opportunity to perform NMR experiments. Marvin was used for drawing, displaying and characterizing chemical structures, substructures and reactions, Marvin 17.21.0, ChemAxon (https://www.chemaxon.com).

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) through programme and project grants J1-2471, P2-0046, L2-3175, J4-4633, J1-4398, L2-4430, J3-4498, J7-4638, J1-4414, J3-4497, P2-0438, I0-E015, J1-50034, J1-60001, and J7-50043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.F., G.H., and U.B. were responsible for the project’s initial conception. F.F. and G.H. conceived the experiments. F.F. performed the experiments. F.F. and G.H. analysed the results. F.F. and G.H. developed a model. F.F. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. U.B. supervised the project and was responsible for editing the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frešer, F., Hostnik, G. & Bren, U. Model for the description of interactions between ellagitannins and Fe(II) ions. Sci Rep 16, 6631 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37616-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37616-6