Abstract

Monitoring the specific conductance (SC) in coastal zones is vital for environmental management and sustainable development. Due to unpredictable reasons such as atmospheric conditions, mechanical problems, power outages, sensors limits, etc., recording systems may fail which causes gaps in data recording. In this study, original artificial intelligence (AI) models are developed for the modeling and reconstruction of missing SC data. Two novel swarm-based deep neural networks (DNNs)—the nonlinear group method of data handling (NGMDH) and a long short-term memory (LSTM) model integrated with the turbulent flow of water-based optimization (TFWO) algorithm were developed and applied to model SC records. The results were also compared with six conventional and two ensemble machine learning (ML) models. The efficacies of the models were evaluated in five hypothetical scenarios. Then, in the derivation phase, the best models were applied to the SC datasets comprising 5% gaps. The results highlighted the extraordinary role of AI-based models in improving knowledge on SC distribution in coastal waters. The new LSTM-TFWO and NGMDH-TFWO models, with average normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) of 0.11 and 0.11, and R² of 0.742 and 0.71, are approximately 11% and 6.36% more accurate than LSTM and NGMDH models, respectively. However, the tree-based models, with an average NRMSE of 0.05, demonstrate substantially higher accuracy than these complex DNN architectures. Among all the ML methods evaluated, ensemble models showed superior performance in reconstructing gaps in SC datasets. XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy, as indicated by an NRMSE of 0.031. Consequently, ensemble models are recommended for application in simulating various types of engineering problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oceans contain 97% of the earth’s water1. The discharge of industrial, municipal, and agricultural wastewater into seawater and progressive erosion of soil due to excessive human intervention in the environment have increased soluble ions in coastal waters and deteriorated water quality2,3. The monitoring of coastal and seawater quality to propose and conduct environmental management programs is essential worldwide4. The SC has been widely used to quantify water quality5. It measures the collective dissolved ions of a solution and is an appropriate indicator of salinity6. The SC can be used to define and trace different pathways7. Moreover, a sudden change in SC is an indicator of leakage of pollution into rivers or sea waters. The water quality researchers require measured SC data for the aforementioned applications. The SC is monitored using large numbers of temporary and permanent measurement stations worldwide. Due to unpredictable factors such as atmospheric conditions, mechanical failures, power outages, and sensor limitations, recording systems may fail which causes gaps in data recording. Missing data increase uncertainty in modeling and prediction of SC distribution. Therefore, reconstructing missing values in recorded SC data is of fundamental importance for environmental management.

Spectral methods, interpolation methods, and ML models are the most commonly applied techniques for the reconstruction of data and signals8,9. In recent years, the applications of ML models to simulate and reconstruct missing data have been attracting more and more attention. Chen and Hu10 and Wang and Deng11 developed a remote sensing methodology by applying artificial neural networks (ANN) and satellite data to estimate and retrieve the surface salinity of the Gulf of Mexico. The obtained results demonstrate that the developed method is a useful technique to predict nearshore salinity. Huang et al.12 applied multilayer perceptron neural networks (MLPNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) for the reconstruction of climate system data. Roy and Datta13 used several ML models to predict the intrusion of salt water into coastal zones. The results show that the performance of developed merged models is the same as the best standalone model. Meng et al.14 developed a convolutional neural network (CNN) to reconstruct ocean subsurface data. They successfully used satellite data for training CNN to predict temperature and salinity. Manucharyan et al.15 showed that the CNN provides better results than liner and dynamic interpolation techniques in the reconstruction of missed sea surface height data gathered by satellite. Thanh et al.16 used six different ML methods to reconstruct the Mekong River discharge data. The study shows that random forest (RF) provides reliable results and indicates that ML methods yield a better outcome than classical approaches. Ren et al.17 used a DNN to estimate missing data in groundwater aquifer monitoring. They developed a LSTM model to study groundwater levels in different wells. The results confirm that regression-based methods provide an accurate estimation of groundwater levels. Zhou et al.18 proposed a DNN for filling gaps in cloud-covered Landsat data. The results confirm that the DNN is about 10% more accurate than the state-of-the-art methods. Ahmadianfar et al.19 compared the performance of several ordinary and hybrid ML models in the prediction of electrical conductivity (EC) of the Maroon River water. The results indicate that models are more accurate than regression techniques. Moreover, the results show that meta-heuristic algorithms increase the precision of ML techniques. Ling et al.20 used the RF method to predict groundwater quality in Pakistan. High performance of RF in the prediction of fluoride in water was reported. Jiang et al.21 suggested ML models to reconstruct the centennial changes in water storage and salinity in lakes. The results indicated that both water storage and salinity are highly affected by precipitation and vapor pressure. Tian et al.22 used an ANN o reconstruct high-resolution subsurface salinity in oceans from lower-resolution data. The results confirmed that the ANN can effectively transfer data from a smaller scale to a larger one. Zhang et al.23 applied a DNN for the reconstruction of 3D ocean subsurface salinity. The results were validated in the range of 0 to 200 m. Baker et al.24 applied a LSTM model to fill the gaps that occurred in the images of sea surface temperature. They highly recommended the LSTM for data reconstruction. Wang et al.25 compared the performance of three ML models include RF, ANN, and multiple linear regression (MLR) in the reconstruction of surface seawater pH. The results revealed that the ANN outperformed the other two methods. Li et al.26 compared the performance of CNN, MLPNN, and generative adversarial neural network (GANN) in reconstructing sensor data for turbulent flow. The results indicated that the GANN provides more accurate results in simulating small vortices. Chu et al.27 indicated the effectiveness of Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) in urban flood forecasting. Chidepudi et al.28 applied a recurrent neural network to reconstruct the gaps in the records of groundwater levels. The results showed the potential of the developed DNN in enhancing engineers’ knowledge of historical groundwater records. Dahmani and Latif29 highlighted the efficiency of meta-heuristic algorithms in optimizing ML parameters for retrieving missed data in water resources engineering. Harter et al.30 used MLR and artificial neural networks (ANN) to reconstruct storm surges in 14 locations in the North-East Atlantic. The results showed that the ANN is an excellent tool for predicting extreme surges, even without considering wind information. Young et al.31 used a radial basis function network (RBFNN) to reconstruct the daily sea surface temperature. The results indicated that the reconstructed data from the RBFNN are about 60% more accurate than interpolation methods. Yang et al.32 used data from multiple sources to reconstruct wide swath significant wave height using a DNN model. The results showed that the DNN outcomes are highly accurate when incorporating SAR data as input parameters. Zhang et al.33 developed spatial–temporal Siamese convolutional neural network (SSCNN) for the reconstruction of subsurface temperature in the Indian Ocean. The results confirmed that the SSCNN predicts with reasonable accuracy. Usang et al.34incorporated a hybrid model of LSTM and CNN to assess estuarine water quality. They confirmed that the LSTM-CNN, as an advanced DNN, achieved superior performance compared to benchmark methods. Long et al35. developed a hybrid LSTM model that combines several methods for water quality modeling and indicated that it may increase the R² value by up to 0.20% compared to the base models. Alver et al.36 compared the performance of several regression ML models in simulating pH in the Red Sea. The results indicated that simple linear regression achieved higher accuracy than more complex ML models such as SVR and ANN. Ahıskalı et al.37 developed a modified VIKOR (VIse Kriterijumsa Optimizacija i Kompromisno Rešenje) method for the selection of water-quality stations. The proposed technique was tested using 12 months of time-series data from three stations located along Boğacık Creek in Giresun. The modified VIKOR demonstrated promising performance in selecting water quality monitoring stations. Abdellatief et al.38 compared the performance of CNN models with conventional and ensemble methods for predicting chloride concentration in concrete exposed to tides. They concluded that the CNN model, with RMSE of 0.18%, can be applied for the prediction of water quality in marine tidal zones. Basirian et al.39 concluded that ensemble methods are more efficient than standard techniques in predicting dissolved oxygen (DO) in coastal zones from satellite images.

Previous studies confirm a high efficiency of DNNs in predicting water quality and supporting environmental management. However, due to their complex structure, the training process of DNNs is a real challenge. Moreover, most studies have neglected information from adjacent stations when simulating water-quality parameters. To address these gaps, present study proposes an innovative AI-based techniques for modeling and reconstructing missing SC data in datasets recorded in coastal waters. The methodology is based on training the ML models using available datasets from adjacent stations. The skill of regular, novel swarm-based DNNs, and ensemble ML models in modeling SC in the Gulf of Mexico was assessed. The regular ML techniques used include MLR, MLPNN, adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), LSTM, and group method of data handling (GMDH), and classification and regression trees (CART). The developed swarm-DNNs include LSTM and nonlinear group method of data handling (NGMDH) integrated with the turbulent flow of water-based optimization (TFWO) algorithm. The application of TFWO to tune the parameters of DNNs is a novel approach for addressing the challenge of fine-tuning of DNN models. XGBoost and RF, two tree-based ensemble methods, are also applied and compared with the other models. The developed models are used to retrieve missing data in SC records from five stations in the Gulf of Mexico operated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Six challenging scenarios are considered in the validation phase. The efficacy and accuracy of all three categories of ML models are evaluated. The models are then ranked, and the best-performing ones are used to reconstruct data and fill gaps in the recorded files during the derivation phase. Methods.

Methodology

In this study, six ordinary, two new integrated DNNs, and two ensemble ML approaches were applied to reconstruct the water quality data of the Gulf of Mexico. The developed theoretical models are described in the following sections.

Ordinary machine learning methods

MLPNN is one of the most widely recognized ANNs. The elements/neurons of MLPNN are connected in a feed-forward layered network. Nonlinear algorithms are applied to transfer information between layers40. This technique has been successfully used in the modeling of different engineering problems41,42. The structure of MLPNN consists of three main layers including the input layer, hidden layers, and output layer. Considering more hidden layers the complexity of the system increases and a network turns into a deep neural network. In this study, an MLPNN with one hidden layer consisting of 10 neurons was developed. The Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) algorithm was employed to obtain the network coefficients and finalize the construction of a network.

ANFIS is a multilayer feed-forward network that uses the advantages of a neural network learning algorithm and fuzzy logic. This idea was firstly introduced by Jang43. The ANFIS structure, like a neural network, consists of elements/neurons. However, unlike the neural networks, the number of its layers is fixed and equal to 5.

LSTM is an advanced extension of a recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to enhance the traditional neural network in solving long-term problems44. The LSTM uses special elements/neurons with assigned nonlinear activation functions to capture trends in data. The elements of LSTM are called cells. The LSTM cells store information over a long period. The cells use current inputs and information from the past to calculate the outputs45. The main idea of LSTM cells was introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber46. Their cells contain the input and output gates. Gers et al.47 improved the network by adding forget gates into the cells.

GMDH is a self-organizing deep neural network that was introduced by Ivakhnenko48 to diagnose the nonlinear inputs–output pattern. Ivakhnenko48 suggested using the Kolmogorov–Gabor polynomial functions in the GMDH elements. Second-order polynomials are usually used in the state-of-the-art studies:

where x and a are the input and the weighs vectors and y is the output. Unlike conventional neural networks, the GMDH network is developed layer by layer49. The GMDH sorts the elements and selects the best ones to build the next layer. The conventional GMDH networks are trained by regression techniques. However, the successful applications of the meta-heuristic algorithms in the training process of GMDH are also reported in numerous studies49,50. Mahdavi-Meymand et al.51 applied nonlinear equations instead of polynomials equations:

The weights, a, are determined by optimization algorithms. In this study, both GMDH and nonlinear GMDH (NGMDH) were applied for reconstructing the quality data.

CART is one of the most famous tree-based algorithms for classification and regression problems, was introduced by Breiman et al.52. CART divides the main data set into several more homogeneous sub-data sets, where the data trends are more similar compared to the main data set. CART’s output is a tree consisting of branches and nodes. The end nodes are called leaves. For regression problems, CART fits a linear regression equation to the data set of each leaf.

Swarm NGMDH and LSTM

In this study, two novel DNN models, NGMDH-TFWO and LSTM-TFWO, were developed for the prediction of SC in coastal waters. The main part of the development of ML algorithms is the optimization process. The optimization process or training process leads to the determination of the coefficients of equations by applying observed data. In the structure of LSTM algorithms there are many coefficients. These coefficients comprise weights, recurrent weights, and biases of gates and output layer. The coefficients of NGMDH include\(\:\:\left\{{a}_{0},\:\:{a}_{1},\:\dots\:,\:{a}_{7}\right\}\). In the common version of LSTM gradient descending-based method is used to obtain the weights and biases of neurons. Meta-heuristic algorithms that apply stochastic procedures are robust alternative approaches used to train ML models. The TFWO is a new swarm-based meta-heuristic algorithm developed by Ghasemi et al.53. The TFWO is inspired by a hydrodynamic phenomenon called a whirlpool. The flow is calculated along a spiral path created by a turbulent flow passing submerged obstacles. Like other meta-heuristic algorithms, at the first stage of TFWO, the considered population is distributed randomly in a search space. The population is divided into equal groups. The best agent in a group is considered to be the center of a whirlpool. The best agents are determined based on an objective function. In this study, NRMSE was applied to calculate an error and rank the population. The objects around the whirlpool are affected by centripetal force and move towards the center of the whirlpool. The new positions of objects are obtained from:

where x is the position of ith object in the jth group, X denotes the position of the jth whirlpool, and \(\:\varDelta\:x\) is the displacement. The \(\:\varDelta\:x\) depends on the new objects angle, \(\:{\phi\:}^{t+1}\), and the best and the worst whirlpool. The objects angle is updated by:

where r1 and r2 are random values between 0 and 1. The \(\:\varDelta\:x\) is calculated from:

where \(\:{r}_{3}\) and \(\:{r}_{4}\) are random vectors between 0 and 1, and \(\:{X}_{H}\) and \(\:{X}_{L}\) are the whirlpools are chosen from:

where f is the objective function (in this study, NRMSE), and sum denotes the summation operation. Centrifugal force is a force in direction of centripetal force and causes the objects to move away from the center of whirlpools. The centrifugal force is obtained from the following equation:

By considering a random number between 0 and 1, r5, if \(\:{FC}_{i}^{t}<{r}_{5}\), the effect of centrifugal force is implemented just on one elements, k, which is selected randomly:

where r6 is a random number between 0 and 1, and \(\:{x}_{i,min}\) and \(\:{x}_{i,max}\) are minimum and maximum values of the feature of ith object, respectively. In the TFWO algorithm, the whirlpools affect each other. The weaker whirlpools move to new positions based on their distances and directions from the stronger ones:

where r7 is a random vector between 0 and 1, and \(\:{X}_{G}\) is the whirlpool of minimum \(\:{\text{g}}_{j}^{t}\):

These steps are repeated until the algorithm reaches the final solution.

Ensemble tree methods

The application of ensemble strategies is one of the effective procedures for increasing the performance of single-structure ML models. RF is a popular and widely recognized ensemble ML model for solving complicated problems. The main idea behind RF is to create multiple predictor trees instead of generating and optimizing a single tree at a time54. RF uses a bagging method to calculate the final output from the outputs of individual trees. In this study, an RF containing 200 trees was developed to model seawater quality and the average method was used to calculate the final output. The XGBoost is a boosting-based ensemble ML model proposed by Chen and Guestrin55. Similar to RF, XGBoost employs CART as its base learner. The model constructs trees sequentially, and their outputs are aggregated to produce a final prediction. This means the output of each tree serves as the input for the next one. In each step, the new tree contributes to fixing the errors of the previous tree to enhance the prediction accuracy. To compare the RF and XGBoost performances, the number of trees for XGBoost was also set to 200.

Study area and data description

The Gulf of Mexico is a semi-enclosed basin located south of the United States and east of Mexico. The Gulf of Mexico with around 1.6 million km2 area is ranked the ninth largest body of water worldwide56. The water quality of this large marine ecosystem is of fundamental importance for the sustainable development of the whole region57. Data from five stations of the USGS in the Gulf of Mexico are considered in analyses conducted in this study. The selected stations are close to the Pascagoula River and Mullet Lake. These stations are located at A: 30°18’29” N, −88°35’02” E, B: 30°21’46.4” N, −88°41’41.0” E, C: 30°23’18” N, −88°51’26” E, D: 30°19’07” N, −88°58’20” E, and D: 30°15’16” N, −88°52’08” E. The location of the stations is shown in Fig. 1.

Map of the North America and the Gulf of Mexico with the locations of USGS monitoring stations. The raw map data were obtained from https://www.naturalearthdata.com, and QGIS was used to generate the final map. The satellite photo was obtained from Google.

Water quality parameters and the free-surface elevations were recorded every 15 min. The recorded data are available on the USGS website. The stations with full time-series datasets (stations A, B, C, and D) consist of 11,616 data from 17 January 2022 to 17 May 2022. The rate of missed records differs from station to station and reaches up to 5% of datasets for station E. The gaps in the recorded data are inevitable. Filling gaps in datasets is a crucial task for scientists and engineers. In this study, a ML methodology is applied to fill the gaps in the Gulf of Mexico water quality datasets. In the study, the water temperature (T), free-surface height (H), and SC of nearby stations were considered as inputs in the developed models. Figure 2 shows examples of recorded time-series data of SC for five stations. The gaps in station E datasets are specified in Fig. 2. More details regarding the datasets are provided in Table 1.

Modeling strategy and phases and scenarios

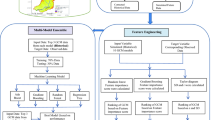

As described, the specific conductance dataset E (Fig. 1) contains around 5% gaps. Two novel DNNs, LSTM-TFWO and GMDH-TFWO were developed to reconstruct data missing from this station. The datasets from neighbor stations were used as input for the developed models. Six different scenarios, that are categorized in the validity and derivation phases, were considered. The validity phase contains five scenarios. In the validity phase, the accuracies of models for different configurations of stations are evaluated. Actually, in the validity phase, the developed methods and the gap-filling strategy are verified. In the derivation scenario, the best methods are applied to fill the gap in real situations. Table 2 shows the considered scenarios. The scenarios I to IV refer to fully-recorded data. The data were divided randomly into training, validation, and testing groups. About 70% of the data were used for optimizing the ML models in the training phase, 15% were used for controlling over-fitting in the validation phase, and 15% were used for evaluation in the testing phase. In scenario V, around 95% of available data, were divided into training, validation, and testing groups. The scenarios I to V concern hypothetical situations. In these scenarios, the predicted values can be compared with exact values. Whereas, scenario VI refers to a real situation. In scenario VI, the training-validation dataset was randomly divided into training (70%) and validation (30%) groups. By considering 5% of the data of neighbor stations as inputs to the trained models, the SC time series data of station E was reconstructed.

In general, the considered parameters for modeling include the T, H, and SC. The SC of the target station is the output of the developed models. The SC, H, and T of other stations, can be considered as inputs for the developed models. However, we calculated the R2 and Mallows Cp corresponding to possible configurations of inputs. This strategy can help to decide which configuration of inputs will provide the most accurate results. The input configuration with the highest R2 and lowest Mallows Cp is the best option. The selected inputs for each scenario may be written as:

Scenario I

Scenario II

Scenario III

Scenario IV

Scenario V & VI

To provide a visual overview of modeling methodology, a flowchart illustrating the structure and consecutive steps of applied procedure is presented in Fig. 3.

Error calculation

Four statistical indicators were used to conduct the comparisons of the results obtained by applying the developed models with measurements. The first indicator is the normalized root mean square error (NRMSE)12:

where \(\:{SC}_{p}\) denotes the modeled values of SC, \(\:{SC}_{m}\) denotes the measured SC, and N is the number of dataset. We used normalized versions of RMSE to conduct comparisons of results obtained in different scenarios. Models with lower NRMSE values have better performance than those with higher values, where an NRMSE of 0 indicates perfect predictions. The next metric is the coefficient of determination (R²), which can be calculated using the following Eq. 58:

Where the bar line denotes the average of predicted and measured values. The ideal value of R² is 1. The Nash–Sutcliffe model efficiency (NSE) is another widely used index and is calculated using the following Eq. 58:

NSE values range from −∞ to 1, where a value of 1 represents an optimal prediction. The last indicator is the index of agreement (IA), for which a value of 1 represents an exact prediction, and it is calculated by applying the following formula59:

Results

In the validity phase, the performances of the developed models in the reconstruction of coastal water quality data were analyzed. Table 3 shows the values of calculated statistical indicators obtained by applying different methods in the designed scenarios.

The results in Table 3 show that the values of R2 and NSE obtained in the training stage by the application of the developed models are greater than 0.6 which shows that the models provide very good predictions. The results also show that the MLR method provides the worst values of NRMS, R2, and NSE, so its efficiency in the reconstruction of SC data is low. The results show that in the training stage the ML models are about 62.98% more accurate than MLR. The performances of the developed non-tree-based ML models are similar. However, MLPNN with the lowest average NRMSE equal to 0.075 is the most accurate model. The average NRMSE of ANFIS, LSTM, LSTM-TFWO, GMDH, and NGMDH-TFWO are about 0.077, 0.101, 0.086, 0.100, and 0.098, respectively. One can see that the results obtained by ordinary non-tree-based ML methods, MLPNN and ANFIS, better fit datasets. The LSTM optimized with TFWO provides about 17.09% more accurate results than LSTM. This indicates that novel optimization strategies are required to derive neural network coefficients. The most significant finding is that the CART algorithm with average NRMSE of 0.033 shows the highest accuracy among the regular models fitted to the training datasets. On average, CART is about 173.07% more accurate than other regular ML models. Nevertheless, the calculated indices during the training stage clearly show that both ensemble models, RF and XGBoost, are more accurate than all regular ML models. XGBoost with average NRMSE of 0.007 and IA of 1 is the most suitable model for modeling SC of coastal zones. The training results show that the model error in scenarios IV and V are higher than in other scenarios of the validity phase. This indicates that datasets from stations B, C, and D have common and similar features. However, the results from scenarios IV and V are reliable, R2 > 0.6.

The accuracy of the developed models on the testing datasets is an important factor in selecting appropriate models for the derivation phase. Table 4 shows the results of the models in the validity phase for the testing datasets. The results indicate that the accuracies of all models derived to reconstruct coastal water quality are acceptable. Like in the training stage, the accuracies of the derived ML models in the testing stage are higher than MLR. The performance of ML models is about 48.19% better than MLR. The average NRMSE of MLPNN, ANFIS, LSTM, LSTM-TFWO, GMDH, and NGMDH-TFWO are about 0.112, 0.111, 0.122, 0.110, 0.117, and 0.110, respectively. In contrast, the CART model has an average NRMSE of about 0.05, which is significantly better than the other regular methods. The performances of GMDH and NGMDH-TFWO are close to each other. However, NGMDH-TFWO yields slightly more accurate results. The TFWO increases the accuracy of LSTM by 10.13%, which is significant for an optimization algorithm. The results show that the application of nonlinear transfer function instead of quadratic polynomial in the GMDH network provides about 5.67% more accurate results. Similar to the training stage, the ensemble methods RF and XGBoost produce better predictions than individual models. XGBoost, with an average NRMSE of 0.031 and an R² of 0.975, ranked as the most powerful method for the reconstruction of SC data in the coastal zones. The scenario V describes most adequately the real situation/problem, so this scenario is most appropriate for the verification of the developed models. The analysis shows that the results and accuracy obtained by the developed models for scenario V are reasonable. The average statistical indicators are acceptable, R2 > 0.6. The results in Table 4 also reveal that the average accuracies of models in scenarios II and III are slightly higher than in other scenarios. This indicates that for the reconstruction of missing data the application of datasets from nearby stations located in different directions provides the most accurate results.

Scatter plots are simple and useful visualization techniques for the validation and comparison of developed models. The scatter plots obtained by applying the developed models for scenarios I and V are shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

The scatter plots show that the derived models provide reasonable results and can be applied to reconstruct missing data in recorded datasets. The scatter plots well illustrate the advantages and higher performance of ML models over the MLR. The scatter points of ML models are more close to the bisector line than the corresponding points obtained by applying MLR. The scatter plots reveal that although the statistical indicators of non-tree-based ML models are close to each other, their points are located in different places. The plots show that LSTM-TFWO points are less scattered than corresponding LSTM points, which confirms that the TFWO outperforms the gradient descent algorithm. The high performance of NGMDH-LSTM in all scenarios is obvious. Scatter plots clearly indicate that the CART, RF, and XGBoost are much more accurate than other methods. These tree-based models, with high values of R2 and a slope of the trend line close to 1 in both scenarios, provide perfect predictions. The points of the ensemble models, especially XGBoost, are most perfectly scattered around the 1:1 line, recording the best performance. The scatter points also show that the derived models provide more accurate predictions in scenarios II. The points obtained by the derived models in scenario V that describes most adequately the real situation/problem and is most appropriate for the verification of the developed models are scattered around 1:1 lines. This confirms that the designed data reconstruction strategy is correct and successful.

Taylor diagram shows three indices describing the accuracy of developed models i.e. correlation (R), standard deviation (σ), and central RMSE in one graph. The Taylor diagram enables us to compare the results obtained by the derived models with observed data. Figure 6 shows the Taylor diagrams obtained in the validity phase.

In the plotted Taylor diagrams, the circle lines denote σ, the circle dash lines denote central RMSE, and dash lines denote R values. The best model is closest to the observed point. It can be seen that the quality points of reconstructed values located close to observed data. In general all models properly predicted unseen data. However, the quality points of ML models in compared with MLR located closer to the observed points which indicates they are more accurate. This issue is well visible in the Taylor graph that shows all scenarios together. The separation of CART, RF, and XGBoost from other methods, along with their impressive performance, is clearly evident. The quality points of XGBoost in all scenarios are the closest to the observed points, indicating its superior performance. These graphs like statistical indicators (Table 4) approves that the models performance in scenario V is lower than others.

Another visual technique for analyzing the performance of ML models is the violin plot, which is shown in Fig. 7 for all scenarios. The comparison between the distribution graphs clearly indicates that the shapes of the CART, RF, and XGBoost methods are similar to the shape of observations. Figure 7 shows that for the reconstruction of SC data, XGBoost has the most similar distribution shape to the observations and is the most accurate method.

In the derivation phase, the derived models are applied to reconstruct missing data in the records of specific conductance. Table 5 shows the calculated errors obtained in the optimization process.

In the validation phase, it was shown that the results obtained by the application of the derived tree-based models very well predict the measured values. Table 5 shows that XGBoost, with an NRMSE of 0.009 and an R² of 0.998, provides the most accurate results in the training datasets of the derivation phase. Moreover, the validation dataset indicates that the XGBoost and can be applied to reconstruct missing data in recorded datasets.

The trained models are applied to reconstruct missing data in the recorded datasets. The completed time series of SC for station E is presented in Fig. 8. The plots show that the reconstructed time series is in reasonable agreement with the recorded specific conductance. Based on the ranking of models, the XGBoost graph is recommended.

Discussion

In this study, standard, two novel swarm-based DNNs, and ensemble ML models were employed to reconstruct missing data in the records of SC acquired from coastal water. The results show that advanced ML methods are capable to reconstruct missing data in the records of datasets. The newly developed DNNs are powerful tools to reproduce the patterns of multi-station water-quality data. However, the performance of CART is far more accurate than DNNs. The reason lies in the different structure of CART, which benefits from a clustering strategy. The clustering causes CART to create a high correlation between the information of neighboring stations. As expected and frequently confirmed in the literature60,61, ensemble techniques enhance the performance of regular methods.

The analysis indicates that the locations of the measurement stations have a significant effect on the accuracy of predicted results. For the modeling of coastal water quality, it is recommended to consider the target station to be in the middle of other stations. However, the accuracies of ML models for non-ideal scenarios are also acceptable. The initial models were developed using a static baseline dataset constructed to address missing SC data. Nevertheless, to adequately reflect emerging environmental trends including climate induced variations in SC, an automated retraining mechanism is necessary.

The LSTM is a recurrent type of neural network. The previous studies claim that the LSTM outperformed ordinary ML in the time series modeling of environmental problems. Since the LSTM elements use time steps (lags), to conduct adequate comparisons, the ordinary ML methods should apply a similar approach. This is a challenging problem for future studies.

Generally, the LSTM is developed for time series modeling. The problem is whether this technique can be used for non-time series modeling. From a theoretical point of view, non-time series data may be applied by LSTM. Because the neurons are advanced and if the LSTM do not see any correlation between lags they will not be considered. The results of this practical application study show that the LSTM results in the non-time series modeling are acceptable. However, the number of LSTM coefficients is high and a powerful optimization technique is required to derive the coefficients for a model. This study indicates that the well-trained DNNs applied to non-time series modeling outperform ordinary ML methods.

The GMDH is a type of DNN. The results indicate that the NGMDH is more accurate than the GMDH. This finding follows the results obtained in the studies conducted by Mahdavi-Meymand et al.51. Testing other types of transfer functions in GMDH is recommended for future studies.

Optimization is the most important part of a regression computational tool. The novel computational methodology developed in this study is based on a hybrid structure of a swarm meta-heuristic algorithm and DNNs. The results confirmed the strength of meta-heuristic algorithms in fine-tuning complex ML models. Therefore, it is noteworthy that the developed computational method indicates a need to employ both optimization and data analytics methods to formalize engineering knowledge.

Another important issue that needs to be discussed is the high accuracy of ensemble methods. Both bagging and boosting ensemble methods enhance the accuracy of individual CART models. However, ensemble methods benefit from a more complicated structure, which requires more computational efforts. This issue may limit the applicability of ensemble models for large datasets. Hence, researchers should focus on developing robust and simpler ML models that can be used in real-time or field applications.

The DNNs and ensemble methods provide robust capabilities for detecting hidden patterns in datasets. However, their inherent lack of transparency may affect environmental management projects. The gap between high-performance methods and transparency can be bridged through post-hoc explainability. In future studies, to enhance the efficiency of DNNs and ensemble models, it is suggested to integrate such techniques as for example Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), or deep learning important features (DeepLIFT) to investigate the effect of neighboring stations on the SC of a target station.

Conclusion

This study proposes an AI framework that engages standard and newly developed swarm-based DNNs, as well as ensemble ML models, to reconstruct missing data in SC records acquired from the Gulf of Mexico. The developed swarm-based DNNs employ the TFWO algorithm to fine-tune the NGMDH and LSTM. Two ensemble methods, including RF and XGBoost, were also applied, and their results were compared with other methods. The unmeasured SC data of the target station were estimated using the data recorded at neighboring stations. The simulation was divided into the validity and derivation phases. The validity phase consists of five scenarios to determine the performance of developed models for different configurations of stations. The best methods were applied in the derivation phase to reconstruct missing data in the recorded datasets. The analysis showed that the best results are obtained when the target station is located in the middle of other stations. The results show that the ML models and MLR provide a reliable approximation of SC in all scenarios. The ML models are about 48.19% more accurate than MLR algorithms. The TFWO swarm algorithm increased the accuracy of the DNN by up to 11%. TFWO is a robust technique that can be applied to optimize ML algorithms and other engineering and scientific problems. The CART algorithm, which benefits from a simple structure, exhibited excellent prediction with an average NRMSE of 0.05. However, both ensemble models are more accurate than others. The results showed that among all developed models the XGBoost with average NRMSE of 0.031 is the most accurate method.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Christ, R. D., Wernli, R. L. & Sr The ROV Manual (Second Edition): A User Guide for Remotely Operated Vehicles, Chap. 2 – The Ocean Environment. 21–52 (2014).

Hutton, J. M., Price, S. J., Bonner, S. J., Richter, S. C. & Barton, C. D. Occupancy and abundance of stream salamanders along a specific conductance gradient. Freshw. Sci. 39, 433–446 (2020).

Deng, T., Chau, K. W. & Duan, H. F. Machine learning-based marine water quality prediction for coastal hydro-environment management. J. Environ. Manage. 284, 112051 (2021).

Kim, Y. H., Im, J., Ha, H. K., Choi, J. K. & Ha, S. Machine learning approaches to coastal water quality monitoring using GOCI satellite data. GISci Remote Sens. 51, 158–174 (2014).

Miller, R. L., Bradford, W. L. & Peters, N. E. Specific conductance: theoretical considerations and application to analytical quality control. USGS Numbered Series. (1988).

Nguyen, T. G. et al. Salinity intrusion prediction using remote sensing and machine learning in data-limited regions: A case study in vietnam’s Mekong delta. Geoderma Reg. 27, (2021).

Smith, E. A. & Capel, P. D. Specific conductance as a tracer of Preferential flow in a subsurface-drained field. Vadose Zone J. 17, 1–13 (2018).

Taie Semiromi, M. & Koch, M. Reconstruction of groundwater levels to impute missing values using singular and multichannel spectrum analysis: application to the ardabil Plain, Iran. Hydrol. Sci. J. 64, 14 (2019).

Abu Romman, Z., Al-Bakri, J. & Al Kuisi, M. Comparison of methods for filling in gaps in monthly rainfall series in arid regions. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 6674–6689 (2020).

Chen, S. & Hu, C. Estimating sea surface salinity in the Northern Gulf of Mexico from satellite ocean color measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 201, 115–132 (2017).

Wang, J. & Deng, Z. Development of a MODIS data-based algorithm for retrieving nearshore sea surface salinity along the Northern Gulf of Mexico Coast. Int. J. Remote Sens. 39 (2019).

Huang, Y., Yang, L. & Fu, Z. Reconstructing coupled time series in climate systems using three kinds of machine-learning methods. Earth Syst. Dynam. 11, 835–853 (2020).

Roy, D. K. & Datta, B. Saltwater intrusion prediction in coastal aquifers utilizing a weighted-average heterogeneous ensemble of prediction models based on Dempster-Shafer theory of evidence. Hydrol. Sci. J. 65, (2020).

Meng, L., Yan, C., Zhuang, W., Zhang, W. & Yan, X. H. Reconstruction of three-dimensional temperature and salinity fields from satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126 (2021).

Manucharyan, G. E., Siegelman, L. & Klein, P. A deep learning approach to Spatiotemporal sea surface height interpolation and Estimation of deep currents in geostrophic ocean turbulence. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13 (2021).

Thanh, H. V. et al. Reconstructing daily discharge in a megadelta using machine learning techniques. Water Resour. Res. 58 (2022).

Ren, H., Cromwell, E., Kravitz, B. & Chen, X. Technical note: using long short-term memory models to fill data gaps in hydrological monitoring networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 1727–1743 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. For-backward LSTM-based missing data reconstruction for time-series Landsat images. GISci Remote Sens. 59, (2022).

Ahmadianfar, I., Shirvani-Hosseini, S., He, J., Samadi-Koucheksaraee, A. & Yaseen, Z. M. An improved adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system model using conjoined metaheuristic algorithms for electrical conductivity prediction. Sci. Rep. 12, 4934 (2022).

Ling, Y. et al. Monitoring and prediction of high fluoride concentrations in groundwater in Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 156058 (2022).

Jiang, X. et al. Centenary covariations of water salinity and storage of the largest lake of Northwest China reconstructed by machine learning. J. Hydrol. 612, 128095 (2022).

Tian, T. et al. Reconstructing ocean subsurface salinity at high resolution using a machine learning approach. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 14, 5037–5060 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Reconstructing 3D ocean subsurface salinity (OSS) from T–S mapping via a data-driven deep learning model. Ocean. Model. 184, 102232 (2023).

Baker, S., Huang, Z. & Philippa, B. Lightweight neural network for Spatiotemporal filling of data gaps in sea surface temperature images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–10 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Reconstruction of surface seawater pH in the North Pacific. Sustainability 15, 5796 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Deep learning reconstruction of high-Reynolds-number turbulent flow field around a cylinder based on limited sensors. Ocean. Eng. 304, 117857 (2024).

Chu, W. et al. SHAP-powered insights into Spatiotemporal effects: unlocking explainable Bayesian-neural-network urban flood forecasting. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 131, 103972 (2024).

Chidepudi, S. K. R., Massei, N., Jardani, A. & Henriot, A. Groundwater level reconstruction using long-term climate reanalysis data and deep neural networks. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 51, 101632 (2024).

Dahmani, S. & Latif, S. D. Streamflow data infilling using machine learning techniques with gamma test. Water Resour. Manage. 38, 701–716 (2024).

Harter, L., Pineau-Guillou, L. & Chapron, B. Underestimation of extremes in sea level surge reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 14, 14875 (2024).

Young, C. C., Cheng, Y. C., Lee, M. A. & Wu, J. H. Accurate reconstruction of satellite-derived SST under cloud and cloud-free areas using a physically-informed machine learning approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 313, 114339 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Reconstruction of wide swath significant wave height from quasi-synchronous observations of multisource satellite sensors. Earth Space Sci. 11, e2023EA003162 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Spatial-temporal Siamese convolutional neural network for subsurface temperature reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–16 (2024).

Usang, R. O., Olu-Owolabi, B. I. & Adebowale, K. O. Integrating principal component analysis, fuzzy inference systems, and advanced neural networks for enhanced estuarine water quality assessment. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 57, 102182 (2025).

Long, J., Lu, C., Lei, Y., Chen, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Application of an improved LSTM model based on FECA and CEEMDAN–VMD decomposition in water quality prediction. Sci. Rep. 15, 12847 (2025).

Alver, D. O., Isik, H., Palabiyik, S., Akkan, B. E. & Akkan, T. pH acidification in the red sea: A machine learning-based validation study. J. Sea Res. 102613 (2025).

Ahıskalı, A., Akkan, T. & Bas, E. Evaluation of a new approach in water quality assessments using the modified VIKOR method. Environ. Model. Assess. 1–11 (2025).

Abdellatief, M., Abd-Elmaboud, M. E., Mortagi, M. & Saqr, A. M. A convolutional neural network-based deep learning approach for predicting surface chloride concentration of concrete in marine tidal zones. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 27611 (2025).

Basirian, S., Najafzadeh, M. & Demir, I. Water quality monitoring for coastal hypoxia: integration of satellite imagery and machine learning models. Mar. Pollut Bull. 222, 118735 (2026).

Bourlard, H. & Kamp, Y. Auto-association by multilayer perceptrons and singular value decomposition. Biol. Cybern. 59, 291–294 (1988).

Nooteboom, P. D., Feng, Q. Y., López, C., Hernández-García, E. & Dijkstra, H. A. Using network theory and machine learning to predict El Niño. Earth Syst. Dynam. 9, 969–983 (2018).

Luo, R., Li, C. & Wang, F. Underwater motion target recognition using artificial lateral line system and artificial neural network method. Ocean. Eng. 303, 117757 (2024).

Jang, J. S. R. & ANFIS Adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 23, 665–685 (1993).

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Brenner, C., Schulz, K. & Herrnegger, M. Rainfall–runoff modelling using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 6005–6022 (2018).

Yu, Y., Si, X., Hu, C. & Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 31, 1235–1270 (2019).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Gers, F. A., Schmidhuber, J. & Cummins, F. Learning to forget: continual prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 12, 2451–2471 (2000).

Ivakhnenko, A. G. Group method of data Handling — a rival of the method of stochastic approximation. Sov Autom. Control. 13, 43–71 (1966).

Mahdavi-Meymand, A., Sulisz, W. & Zounemat-Kermani, M. A comprehensive study on the application of firefly algorithm in prediction of energy dissipation on block ramps. Eksploat Niezawod. 24, 200–208 (2022).

Jaafari, A. et al. Swarm intelligence optimization of the group method of data handling using the cuckoo search and Whale optimization algorithms to model and predict landslides. Appl. Soft Comput. 116, 108254 (2022).

Mahdavi-Meymand, A., Zounemat-Kermani, M. & Qaderi, K. Prediction of hydro-suction dredging depth using data-driven methods. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 15, 652–664 (2021).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J., Stone, C. J. & Olshen, R. A. Classification and Regression Trees (CRC, 1984).

Ghasemi, M. et al. A novel and effective optimization algorithm for global optimization and its engineering applications: turbulent flow of Water-based optimization (TFWO). Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 92, 103666 (2020).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. & XGBoost A scalable tree boosting system. Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf., 785–794 (2016).

Kumpf, H., Steidinger, K. & Sherman, K. The Gulf of Mexico Large Marine Ecosystem: Assessment, sustainability, and Management (Blackwell Sci. Inc., 1999).

Ward, C. H. Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: before the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Vol. 1 (Springer Nature, 2017).

Moriasi, D. N., Gitau, M. W., Pai, N. & Daggupati, P. Hydrologic and water quality models: performance measures and evaluation criteria. Trans. ASABE. 58 (6), 1763–1785 (2015).

Willmott, C. J. On the validation of models. Phys. Geogr. 2 (2), 184–194 (1981).

Frifra, A., Maanan, M., Maanan, M. & Rhinane, H. Harnessing LSTM and XGBoost algorithms for storm prediction. Sci. Rep. 14, 11381 (2024).

Jang, E., Kim, Y. J., Im, J., Park, Y. G. & Sung, T. Global sea surface salinity via the synergistic use of SMAP satellite and HYCOM data based on machine learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 273, 112980 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M., W.S., B.S.N; Methodology: A.M.; Analysis and interpretation of results A.M., W.S., B.S.N; Writing—draft preparation: A.M.; Writing—review and editing: W.S., B.S.N; Supervision: W.S., B.S.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahdavi-Meymand, A., Sulisz, W. & Nandan Bora, S. Application of swarm-based deep neural networks and ensemble models for reconstruction of specific conductance data. Sci Rep 16, 7292 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38136-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38136-z