Abstract

This study investigates the dielectric properties of polymer composites comprising an acrylic matrix and high-entropy oxide (HEO) (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4 filler. Single-phase HEO was synthesized via solid-state reaction followed by calcination at 850 °C (HEO-850). The research systematically examines the temperature- and concentration-dependent evolution of dielectric properties and charge transport mechanisms within these composite systems. Our findings reveal distinct correlations between filler concentration and dielectric performance enhancement. The unique properties of HEOs, stemming from their compositional complexity and structural characteristics, position these composite materials as promising candidates for advanced dielectric applications. The study elucidates fundamental parameters (temperature and filler concentration of HEO-850) governing the electrical behavior of HEO-polymer composites, providing insights into tailoring their properties for different technological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy oxides (HEOs) represent an emerging class of advanced materials that demonstrate superior performance characteristics compared to conventional oxide systems. Their exceptional properties arise from unique compositional complexity and structural features, positioning them as promising candidates across diverse technological applications. These materials have been used in many applications, for example, energy and data storage1,2, electromagnetic devices3, and thin-film transistors4. The importance of these materials stems from their structural stability over a wide range of temperatures, which provides them with wide application areas and practical stability5. The exceptional structural stability of high-entropy oxides originates from their elevated configurational entropy, attributed to the unpreferential arrangement of multiple metal cations throughout the crystal lattice, specifically the (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4 (will be designated as HEO)6. This fundamental relationship between entropic stabilization and structural characteristics has been extensively validated through multiple investigations7. In addition, the incorporation of multiple transition elements that possess aliovalent oxidation states and different ionic sizes provides them with superior dielectric and magnetic properties8. Optical characterization via UV/Vis spectroscopy reveals that the bandgap of (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4 can be systematically.

modulated through calcination temperature control9. The material exhibits decreasing bandgap energy with increasing calcination temperature, reaching 1.213 eV when calcined at 850 °C (HEO-850). This reduced bandgap enhances the material’s polarizability, as the dielectric constant is inversely proportional to the square of the band gap energy10,11. The electronic and structural properties of transition-metal oxides facilitate unique charge carrier-atomic interactions. These interactions lead to the formation of polaron clouds, which play a crucial role in governing charge transport mechanisms12,13, surface reactivity14, and multiferroic behavior15. The interplay between transition metal d orbitals and oxygen p orbitals determines the polaron characteristics and other related material properties. The efficacy of polymer composites in dielectric applications is governed by multiple interrelated factors, particularly the formation and behavior of polarons and their influence on electrical transport properties. While the electrical conductivity in transition metal oxides typically follows the small-polaron hopping mechanism16, our experimental findings indicate that temperature induces a transition from non-overlapping small-polaron tunneling (NSPT) to alternative conduction mechanisms depending on provided thermal energy and filler concentration (HEO-850). This temperature-dependent evolution of charge transport processes significantly impacts both the conductivity and dielectric response of the composite system.

A polymeric material with a high dielectric constant suitable for energy storage is actively being researched17,18. Usually, it is mixed with high dielectric material such as ferroelectric ceramics19 or by enhancing the polymeric chain structure by copolymer20. Polymeric materials, such as natural rubber21 and acrylate elastomer22 provide a high flexibility, lightweight, and easy to process. Building upon these advantageous characteristics, HEO-850 was incorporated into an acrylic polymer matrix to fabricate composite materials that capitalize on the unique properties of both constituents.

Much of the research has been focused on finding a filler material that can withstand high working temperatures while maintaining structural stability, along with having a high dielectric constant. One of the eligible materials is high entropy oxides, where high-entropy ferroelectric nanoparticles/polyetherimide-AlN/polyetherimide-triptycene bilayer nanocomposites ([0.8(Na0.2Bi0.2Ba0.2Sr0.2Ca0.2)TiO3.0.2NaNbO3]@Al2O3) have been demonstrated minimal hysteresis at high temperature, as well as high thermal conductivity due to the inclusion of AlN23. Furthermore, hydroxylated boron nitride nanosheets and reduced graphene oxide embedded within the polyimide matrix provided a tremendous environmental flexibility as it maintained discharge density with efficiency above 90% at working temperature of 150 °C. Also, the previous material showed gradual enhancement of \({\varepsilon }_{r}\) as filled concentration increased, reaching 4.21, and low dielectric loss tangent (tan \(\delta\)) below 0.0224. HEOs proved its possession of a large values of relative permittivity (\({\varepsilon }_{r}\)) making its highly suitable for different applications, for instance, energy storage25.

Heterogeneous composite materials represent an emerging frontier in dielectric materials research. The distinct interfaces between the filler particles and matrix material facilitate interfacial polarization, whereby space charges accumulate at these boundaries, giving rise to unique dielectric properties. A mean-field theory for materials containing dispersed dielectric spheres in a dielectric medium was derived by Maxwell26. Afterward, Maxwell–Wagner-Sillars (MWS) theory represents an expansion of the original framework to account for the dielectric behavior of heterogeneous systems containing dispersed filler particles27. According to MWS theory the complex dielectric function (\({\varepsilon }_{c}^{*}\)) of heterogeneous mixture can be as:

where \({\varphi }_{f}\) is the volume fraction of the filler particles, \(n\) is shape factor (\(0\le n\le 1\)) of the filler particles, and \({\varepsilon }_{m}^{*}\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{f}^{*}\left(\omega \right)\) is the matrix material complex permittivity and filler permittivity, respectively.

The polymer composite fabrication process is comprised of two sequential steps: synthesis of HEO-850 followed by its incorporation into the acrylic matrix. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis confirmed the successful formation of single-phase HEO-850, while Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) verified the absence of chemical bonding between the polymer matrix and filler material. Dielectric relaxation spectroscopy was employed to systematically investigate the material’s dielectric properties, charge transport mechanisms, and their evolution as functions of temperature and filler concentration.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

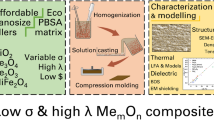

The sample fabrication process consisted of two different main steps. The first step is the process of preparing HEO powder, which was done by solid-state reaction of five oxide precursors—Co3O4 (99.7%), Cr2O3 (99.0%), Fe2O3 (99.0%), NiO (99.0%), MnO (99.0%)—were weighed to set up an equimolar composition of (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4 (HEO-850) in the final product. Subsequently, the composite oxide mixture was homogenized through wet milling using 5 mm zirconia balls in ethanol. The milling was performed in a planetary mill (Fritsch Pulverisette 6, Germany) at 300 rotations per minute for 2 h, effectively improving the mixture’s compositional uniformity. Afterward, the mixture was dried, crushed, and sieved through a 100 µm mesh. Then, the sample was calcinated at 850 °C for 12 h. The calcined powders were subsequently mechanically disaggregated and sieved through a 56 µm mesh screen to ensure uniform particle size distribution and remove agglomerates. Figure 1 shows SEM micrograph of the synthesized HEO powder and particle size distribution.

The second stage involved fabricating polymer composites by systematically incorporating varying concentrations of HEO-850 powder into Clarofast acrylic polymer. The HEO-850 powder, prepared in the initial processing step, was integrated at weight percentages of 1, 3, 5, 10, and 15%. The mixture was mechanically mixed using an agate mortar and pestle for 10 min. Thereafter, the mixture was used to create the final shape of the sample by hot pressing at a temperature of approximately 180 °C and a uniaxial pressure of 350 Pa. The following figure (Fig. 2) shows the whole synthesis process of the samples.

Sample investigation methods

The microstructure and phase analysis of the samples were investigated by mean of scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) (TUSCAN LYRA3) and X-ray phase diffraction (XRD) (RIGAKU3) using Cu Kα-radiation (λ = 0.15412 nm) over a 2θ range of 10° to 80°. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, utilizing a Vacuum Vertex 80v-FTIR spectrometer, was employed in a spectral range between 450 – 4000 cm-1. Electronic transport and dielectric response were investigated using broadband dielectric spectroscopy (DRS) with a Novocontrol Alpha-A analyzer over temperature range of -90 to 90 °C and different HEO filler concentration.

Result and discussion

Scanning electron microscopy – SEM

The morphological and compositional characteristics of the polymer composite samples were investigated using SEM/EDS. Prior to analysis, all samples were sputter-coated with 10 nm of gold (Au) to enhance surface conductivity for optimal EDS measurements. The elemental analysis was performed using an acceleration voltage of 25 kV, ensuring sufficient electron beam energy for the excitation of characteristic kα signals from all constituent elements. Figure 3 reveals the degree of compositional distribution (homogeneity) of the constituent elements throughout the analyzed samples. The composition of the HEO-850 was revealed as Table 1 shows.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy—FTIR

FTIR measurements were conducted to characterize the functional groups within the sample by analyzing their vibrational and rotational energy states. As shown in Fig. 4, the spectral range is between 450—4000 cm-1. The typical signature of the stretching vibration of the -OH group is located between 2846–2297 cm-128. The acrylic polymer exhibits characteristic IR absorption bands: C = O stretching at 1720 cm-129 and C–C bending at 1434 cm-130,31. Furthermore, the strong shape peak at 1143 cm-1 represents the C–O–C stretching vibration, and the peak at 748 cm-1 may relate to the aromatic C-H out-of-plane bending, which is an indicative of the presence of benzoyl groups31,34. FTIR analysis shows nearly consistent spectral patterns across the pristine polymer, HEO-850, and all polymer composites, with one key difference, a weak peak at ∼ 603 cm-1 attributed to M–O bonds (M is metal ions)32. FTIR data indicates that the components maintain their original chemical identities, the acrylic resin matrix, and the HEO-850 filler particles.

X-ray diffraction—XRD

The XRD measurements for all samples were performed using a Rigaku SmartLab 3 kW diffractometer equipped with Cu X-ray source (λ = 1.5406 Å). The investigated angle range extended from 10 to 80°. Figure 5 depicts the XRD diffraction pattern of polymer composite, polymer only, and HEO-850 samples.

The calcination step of the HEO-850 formed a single-phase spinel cubic structure, where the space group was Fd \(\overline{3 }\) m:227, and the lattice parameters were a = b = c = 8.37 Å. Heat treatment at elevated temperatures is considered one of the crucial factors in the formation of a single phase high-entropy oxide due to the improved atomic diffusion and stabilization of the structure as the entropy of mixing is raised33. The pristine acrylic polymer shows three broad diffraction peaks characteristic of amorphous materials. As HEO-850 filler concentration increases, distinct crystalline peaks emerge and intensify in the diffraction pattern.

Dielectric relaxation spectroscopy – DRS

Real and imaginary parts of permittivity

The DRS was employed to investigate the movement of electronic dipoles (e.g. dipolar molecules) in the presence of an electric field. The material response to the presence of the electric field could provide vital information about the extent of energy storage, conductivity, relaxation characteristics, and the activation energy of different processes34 and more. The most widely used equation to describe dielectric relaxation, which is called Havriliak-Negami (H-N) equation, is described by the frequency-dependent equation35 as follows:

where \({\varepsilon }{\prime}\left(\omega \right)\) is proportional to the energy stored in the system (real part of complex permittivity), and \(\Delta \varepsilon\) is the difference between static and high-frequency permittivity (\({\varepsilon }_{s}-{\varepsilon }_{\infty }\)), known as the dielectric strength (\(\Delta \varepsilon\)), arises from the orientational polarization of dipolar molecules. This parameter quantifies the magnitude of the dipolar relaxation process and reflects the system’s capacity for dipole reorientation. The characteristic time scale of this molecular reorientation is represented by the relaxation time (\(\tau\)), which describes the temporal response of dipoles to an applied electric field. Also, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, a and b (sometimes called \(\alpha\) (\(0<\alpha \le 1\)) and \(\beta\) (\(0<\beta \le 1\))) are the symmetric and asymmetric relaxation peak broadening, respectively.

The energy stored (\(\varepsilon {\prime}\)) of the complex permittivity (here \({\varepsilon }^{*}(\omega ) = \varepsilon {\prime}(\omega ) - i\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}(\omega )\)) can be calculated as36:

where \(\beta \phi\) denote the angle from \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) to any value of the \({\varepsilon }^{*}(\omega )\) function in ε′′ vs. ε′ where37:

The \(\varepsilon {\prime}\) can be represented as a function of the logarithmic term of frequency, as shown in Fig. 6 for polymer composites at different temperatures and filler (HEO-850) concentrations.

Figure 6a, b show how temperatures influence the relative permittivity across the measured frequency range. As the temperature increases, the relative permittivity increases, this can be related to the thermal agitation to the charge accumulation at interfaces and enhanced dipolar polarization. The contributions from multiple polarization mechanisms, electronic, ionic, and dipolar, emerge across a wide range of frequencies. However, some of these mechanisms progressively become inactive at higher frequencies as they cannot maintain synchronization with the oscillating electric field38. This behavior manifests in all figures in the high-frequency region. The filler concentration can significantly affect the polarization mechanism by, for example, introducing additional interfaces or defects within the polymer composite. Interposing additional interfaces led to enhancing the MWS polarization and, in turn, higher relative permittivity39. The concentration effect on the dielectric constant is modulated by several factors, including particle agglomeration, effects of percolation threshold, and the losses arising from interparticle interactions. At 1% concentration and a relatively high temperature, the HEO-850 filler particles create more interfaces within the polymer matrix, resulting in an enhanced relative permittivity compared to the pristine polymer. The thermal energy provided to the system agitates the electrons hopping between valence states of transition elements, leading to the formation of a polaron that modulates the electrical conductivity. Moreover, transition elements influence the formation of polarons-coupled electron–phonon states that arise from the interaction between charge carriers and the lattice. These polaronic effects can significantly impact the dielectric relaxation processes and frequency-dependent response of the material. The strength of polaron coupling and their mobility are directly related to the nature and concentration of the transition elements present in the oxide. The temperature-conductivity relationship in HEO follows Arrhenius behavior40,41, characterized by an exponential decrease in resistivity with increasing temperature. This behavior is relatively dramatic at filler concentrations of 1%, 3%, and 5%, which marked a reduction in the relative dielectric constant, indicating a strong concentration-dependent behavior in the dielectric properties of the composite system. At 3% HEO-850 loading, nanoparticle agglomeration may reduce polarization efficiency, leading to lower permittivity values. Near the percolation threshold, at 10% of the HEO-850 filler concentration, the value of relative permittivity, as well as conductivity, shows a substantial enhancement42, where it reaches its highest value, where this type of behavior has been reported by several researchers43,44. At relatively very high filler concentration (15%), the composite surpasses the percolation threshold. At this point, the filler particle creates conductive channels, which lead to a decrease in the relative permittivity45,46.

The imaginary permittivity is characterized as the energy dissipation occurring within a dielectric material when subjected to an applied electric field47. Analysis of the frequency-dependence response demonstrates distinct relaxation processes and loss mechanisms within the material system. Figure 7 shows the \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}{\prime}}\) plot as a function of frequency and mathematically can be described as36:

Figure 7a,b demonstrate the temperature dependence of the dielectric loss behavior, while Fig. 7c and d illustrate how varying HEO-850 concentrations influence the dielectric loss factor. The frequency-dependent dielectric response of the material, as depicted in Fig. 7, demonstrates distinct spectral characteristics across the measured frequency range. In the high-frequency regime, the material exhibits a combined frequency- and temperature-dependent response, indicating the thermal influence on its dielectric behavior. At elevated temperatures, particularly at 60 °C and 90 °C, \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) exhibits a pronounced sharp increase in \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\). The characteristic relaxation peak appears in the midfrequency range at lower temperatures and systematically shifts toward relatively high frequencies with increasing temperature, indicating thermally activated relaxation processes. As the temperature increases, the relaxation time (\(\tau\)) decreases, meaning the relaxation rate is faster, due to the increases in the thermal energy48,49. These diverse behavioral patterns indicate the complex interplay of multiple factors governing the dielectric properties of the acrylic polymer + HEO-850 composite system. This thermal activation promotes dipole formation and strengthens polarization effects within the material. At higher frequencies, the material exhibits diminished response to the alternating electric field, manifested as reduced polarization effects50 and a corresponding decrease in the \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\). This consistent pattern was observed across all polymer composite samples in this study.

Figure 7c,d reveal distinct variations in the dissipative response and charge displacement behavior as filler (HEO-850) increases, representing characteristic measurements observed across the full temperature range of -90 to 90 °C. The two figures (Fig. 7c and d) reveal a distinctive response in the polymer composite containing 10% HEO-850 which has a higher \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) compared to the other samples, which can be attributed to different competing factors. These factors affect the dielectric response and can be classified into intrinsic (e.g., dielectric behavior of filler, and temperature dependence material properties) and extrinsic factors (e.g., interfacial polarization and filler concentration effect). The dielectric behavior of High entropy oxides (HEO) stems from the electronic structure and ionic sizes of their constituent transition elements, transition elements distribution, and from their tendency to form a solid solution with a single crystal structure, which induces the presence of a large number of boundaries and dense discontinuous lattice51,52,53. Filler concentration influences the dielectric properties in different ways, for instance, introducing additional interfaces for charge accumulation, leading to a decrease \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) at the low-frequency region. As the filler concentration approaches the percolation threshold53, a notable enhancement in the value of \(\varepsilon {\prime}\) and conductivity. This transition from dielectric to conductive behavior results in increased dielectric loss \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\)54. The MWS polarization mechanism dominates in the low-frequency regime, manifesting as a reduction in the value of \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\). However, thermal activation enhances this effect, as elevated temperatures provide sufficient thermal energy to facilitate charge carrier mobility, resulting in an increased \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) value. Meanwhile, the high-frequency region is characterized by the relatively low value of \(\varepsilon {\prime}\) and \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) where the material response diminishes as the frequency increases. The activation energies of all investigated samples were determined through analysis of the temperature-dependent relaxation time data. These processes exhibit an Arrhenius-type temperature dependence, which can be expressed as55:

where \({\tau }_{max}\) denotes the maximum relaxation time, τo is the pre-exponential factor, \({E}_{a}\) is the activation energy, and \({k}_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant. This Arrhenius relationship indicates that the relaxation time decreases with increasing temperature, reflecting the thermally activated nature of the conduction processes in the studied materials. The activation energy \({E}_{a}\) was derived from the slope of the linearized Arrhenius plots (\(ln({\tau }_{max})\) vs \(1000/T\) ), providing insights into the energy barrier associated with the relaxation mechanisms, as shown in (Fig. 7). Table 2 shows the activation energy values of acrylic polymer + HEO-850 composite samples at different concentrations.

Systematic variation of HEO nanoparticle content (0–15%) in the epoxy matrix resulted in significant modifications to the electrical properties, with activation energy showing pronounced concentration dependence (Fig. 8). The activation energy of the unfilled epoxy sample was 0.9 eV, which decreased to 0.79 eV for the 1% HEO-loaded sample. This initial reduction suggests that the addition of a small amount of HEO nanoparticles enhances the electrical conductivity of the composite, likely due to improved charge carrier mobility or the formation of conductive pathways at low filler concentrations. However, as the HEO concentration increased to 3%, the activation energy rose to 0.85 eV, indicating a slight disruption in the conductive network, possibly due to nanoparticle agglomeration or interfacial effects. At 5% HEO, the activation energy decreased slightly to 0.84 eV, suggesting a partial recovery of conductive pathways. A significant increase in activation energy was observed at 10% of the HEO-850 filler sample, which may attribute to nearly excessive filler leading to an increased scattering of charge carriers and reduced percolation efficiency. Finally, at 15% of the HEO-850 filler sample, the activation energy dropped again to 0.84 eV, possibly due to the formation of new conductive pathways or a balance between agglomeration and dispersion effects. These trends align with studies on polymer nanocomposites, where optimal filler concentration enhance electrical properties, while excessive loading often leads to diminished performance due to agglomeration and interfacial resistance.

Figure 9 presents the complex permittivity data in the form of a Cole–Cole plot, displaying the imaginary component (\(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\)) versus the real component (\(\varepsilon {\prime}\)) of the dielectric permittivity at two selected temperatures, 30 and -30 °C. This representation provides an immediate visual assessment of relaxation time distributions and their temperature dependence. The relaxation time distribution exhibits a pronounced temperature dependence, wherein the distribution breadth systematically increases with elevated temperatures, indicating thermally activated dispersion of relaxation processes. Also, the thermal energy provided to the system promotes a multi-dispersive relaxation transition from a single relaxation process. This transition indicates activating different dipole processes or inhomogeneity of the sample56. The value of the static dielectric constant (\({\varepsilon }_{s}\)) and the optical dielectric constant (\({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\)) can also be identified by the intersection of the arc with the real axis. Based on Fig. 9, it can be noted that the value of \({\varepsilon }_{s}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) shifted toward the high-frequency region with increasing temperature. The presence of the sudden linear inclination in the value of \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}\) can refer to interfacial polarization or conductivity contribution, e.g., at 3% of HEO-850 filler sample. The sample filled with 10% of HEO-850 shows a significant deviation from the major trend of the other samples, as it appears in Fig. 9c and d, where multiple relaxation processes were observed. Moreover, a significant shift in the value of \({\varepsilon }_{s}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) compared to the other samples.

AC conductivity

The frequency-dependent AC conductivity (\({\sigma }_{ac}\)) can be obtained from the dielectric loss according to the following equation57:

so, the real part and imaginary part of conductivity can be expressed as:

Also, the real part of the complex conductivity (\({\sigma }^{*}\)) can be calculated from the following58:

where the \(tan\delta\) is the dissipation factor (The ratio between the \(\varepsilon {\prime}{\prime}(\omega )\) and \(\varepsilon {\prime}(\omega )\)).

Figure 10a and b show the temperature effect on the ac conductivity, whereas Fig. 10c and d show HEO-850 filler concentration at different constant temperatures (30 and − 30 °C). In Fig. 10a and b and at low-frequency region, the value of \({\sigma }_{ac}\) was nearly zero indicating almost temperature and frequency-independent. As the temperature increases, the effect becomes more prominent at high frequencies region, where the \({\sigma }_{ac}\) becomes more frequency dependent. The thermal energy provided to the system promotes charge carrier migration, allowing more carriers to overcome the potential energy barrier59, and enhance the conductivity. Based on the previous observation, a direct correlation exists between frequency and conductivity. The enhanced \({\sigma }_{ac}\) can be attributed to the characteristic defect structure of HEO60,61,62, wherein the presence of low-activation-energy defect states facilitates charge transport, resulting in significantly enhanced electrical conductivity. The \({\sigma }_{ac}\) analysis (Fig. 10) reveals a characteristic transition from DC-like conductivity to a more dispersive conductivity regime. This transition occurs at a distinct crossover frequency (\({\omega }_{p}\)), which provides insights into the timescale of successful ionic diffusion between structural trapping sites63. Crossover frequency exhibits a temperature-dependent shift toward higher frequencies. This shift may be attributed to the thermal energy generated at higher frequencies, which promotes enhanced ionic conductivity in the material.

Figure 10c and d demonstrate the conductivity concentration-dependent characteristics across selected temperatures, which is representative of the whole tested temperature range of -90 to 90 °C. Within the low-frequency regime (< 104 Hz), the conductivity is observed to be frequency independent, primarily governed by \({\sigma }_{dc}\) contribution. Whereas the dispersion range at the high frequency region represents the AC conductivity (\({\sigma }_{ac}\)), where it shows frequency dependence. The frequency dependence of conductivity or the so-called universal dynamic response (UDR) of ionic conductivity can be described using Jonscher’s power law64:

where \(A\) is a pre-exponential constant, \(\omega = 2\pi f\) is the angular frequency, and \(s\) is the power law exponent, where \(0 < s < 1\). The \(s\)-value can provide an insight into the conduction mechanism with the samples, and it can be obtained by plotting the \(ln({\sigma }_{ac})\) against \(ln(\omega )\). As shown in Fig. 11, the changes in the \(s\) value and conduction mechanisms were observed depending on the filler concentration and temperature. The conduction mechanisms were investigated by analyzing the temperature-dependent behavior of the exponent \(s\) over the temperature range of -90 to 90 °C.

For most of the samples, the value of \(s\) is gradually decreased in a temperature range from 183.15 °C to 243.15 K, followed by a steady increase from 273.15 to 333.15 K. At 363.15 K, \(s\) exhibits a slight decrease. The 3% of HEO-850 fillers display a unique trend, where s decreases slowly in the temperature range of 183.15 to 243.15 K, then increases between 273.15 and 303.15 K. However, at higher temperatures (333.15 to 363.15 K), \(s\) exhibited a significant drop, suggesting a fundamental shift in the conduction mechanism.

The observed trends indicate that for most samples, conduction follows the Overlapping Large Polaron Tunneling (OLPT) model, where charge transport is dominated by tunneling effects and influenced by thermal energy. The general temperature dependence of \(s\) aligns with the OLPT model65. For the sample containing 3% of HEO-850 filler, the sharp decrease in \(s\) value at the high-temperature region (333.15 to 363.15 K) suggests a transition from the OLPT model to a modified correlated barrier hopping (CBH) model. This transition could be attributed to increased thermal energy, which facilitates charge carrier hopping between localized states rather than tunneling66. The broad downward minima observed in the frequency exponent \(s\) over the temperature range from room temperature 183.15 to 333.15 K can be explained using the polaron tunneling model. In this framework, the overlapping of large polarons at two adjacent sites results in a reduction of the polaron hopping energy. This phenomenon arises due to the overlap of large polaron wavefunctions, which effectively lowers the energy barrier associated with polaron hopping, thereby influencing the temperature-dependent behavior of the frequency exponent \(s\). The hopping energy (W) for this model can be expressed as follows67:

where \({W}_{HO}\) is the polaron hopping energy, \({r}_{p}\) and \(R\) is the polaron radius and intersite distance. The polaron hopping energy \({W}_{HO}\) can be expressed as:

and \({\varepsilon }_{p}\) is the effective dielectric constant. The \({\sigma }_{ac}\) and frequency exponent (S) for the OLPT mechanism can be expressed67:

The modified CBH model describes the hopping mechanism of charge carriers (or polarons) in pairs between localized states near the Fermi level, thereby facilitating current transport in the system. The negative temperature dependence of \(s\) indicates that the conduction mechanism is consistent with thermally assisted hopping processes, as proposed by the modified CBH model. According to this model, charge transport occurs through the hopping of carriers over energy barriers, separating the localized states. The observed decrease in \(s\) with temperature suggests a reduction in the effective barrier height, further supporting the thermally activated nature of the hopping process. In the modified CBH model, the temperature dependence of \(s\) can be mathematically expressed as66:

where \({W}_{M}\) is the hopping energy, \({\tau }_{0}= {10}^{-13} s\) represents the relaxation time of the atomic vibrations, and \({T}_{o}\) is the temperature at which \(s\) is unity. The CBH model in terms of the \({\sigma }_{ac}\) is expressed as follows66:

the \(n{\prime}\) is the number of polarons or charge carriers involved in the hopping process, \(N\left({E}_{F}\right)\) is the concentration of pair states, \({R}_{H\omega }\) is the hopping distance at angular frequency \(\omega\). The detailed analysis indicates that the interplay of thermal energy and coulomb interactions governs hopping dynamics, highlighting the utility of the modified CBH model in explaining the conduction behavior of acrylic polymer composite samples. Finally, the sample containing 10% of HEO-850 filler can be characterized by two types of conduction mechanisms, where the non-overlapping small polaron tunneling (NSPT) model was dominated in the temperature range of 183.15 to 273.15 K, while the CBH model was dominated in the temperature range of 273.15 to 363.15 K.

Impedance

The Nyquist plot representation of impedance data provides a comprehensive visualization of dielectric material response to applied alternating current, simultaneously displaying both resistive and reactive components within an equivalent circuit framework. This analytical approach shows the contribution of grain, grain boundaries, interfaces, and stray charges at the electrode to understand the contribution behavior within the material.

In Fig. 12a and b show the real part of the impedance, and the imaginary part of impedance in the inset figure, frequency dependence. As can be seen from Fig. 12, the usual behavior of the impedance (both \(Z{\prime}\) and \(Z{\prime}{\prime}\)) versus the frequency plot can be observed, as its value rises in the low frequency region and falls in the mid-high range of frequency. Increasing the frequency reduces the value of \(Z{\prime}\) and \(Z{\prime}{\prime}\), indicating the increase of the conductivity due to enhanced electron hopping as the frequency increases. The effect of temperature on the value of \(Z{\prime}\) and \(Z{\prime}{\prime}\) can also be observed where it can be seen that the value of \(Z{\prime}\) decreases as the temperature rises, which means that the conductivity rises due to the provided thermal energy to the system68.

The plot of \(Z{\prime}\) against the frequency and the inset figure shows the plot of \(Z{\prime}{\prime}\) against the frequency at (a) 3% of HEO-850 filler (b) 10% of HEO-850 filler at different temperatures, and Nyquist plot of acrylic polymer + HEO-850 composite samples at (c) 30 °C (d) − 30 °C.

The Nyquist plot (Fig. 12c and d) gives several indications based on the amplitude of the semicircle and the intercept points. The reason for the characteristic shape of the Nyquist plot, which has been reported in many papers, is due to the charge transfer resistance69. The intercept point gives information about the value of resistance. Furthermore, the capacitance value of the system due to induced polarization, and the capacitance of the static system can be deduced from the amplitude35. The Nyquist plot (in Fig. 12) exhibits a straight line, deviating from its semi-circle typical shape, indicating the capacitive process, where a small capacitive line refers to relatively high capacitance.

Conclusion

The dielectric response of acrylic polymer samples containing different concentrations of HEO-850 was studied. The HEO powder was prepared by a solid-state reaction by mixing five types of oxides to obtain an equimolar composition of (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4. The resulting material was heat-treated at 850 °C. The material exhibited the usual structural stability of HEO based on XRD results. The acrylic polymer was mixed with HEO-850 powder in different proportions, and the resulting mixture was used to prepare the final samples. The material showed an increased relative dielectric constant as the temperature increased, following the Arrhenius behavior. The dielectric properties demonstrate systematic variation with HEO-850 filler concentration, revealing composition-dependent behavior across the investigated concentration range. The material exhibits maximum relative dielectric constant and peak conductivity values in proximity to the percolation threshold concentration (10%). As the concentration of the filler increases to 15%, a significant decrease in relative dielectric constant and conductivity was observed. The relaxation peak demonstrates a systematic shift toward higher frequencies with increasing temperature, accompanied by a reduction in relaxation time—a behavior attributed to enhanced ionic mobility through thermal activation. Transition ions play a role in the dielectric behavior of the polymer composite, which stems from the variable valence states where heat induces hopping between different oxidation states, thus contributing to the conductivity and dielectric response of the material. The presence of multiple transition elements also creates local charge heterogeneities and distortions in the crystal structure. These structural irregularities generate localized electronic states that can act as polarization centers, contributing to the overall dielectric response. The cole–cole plot reveals that the sample containing 10% of HEO-850 filler has the highest relaxation strength, which expresses the charge carrier concentration and high hope and orientational polarization.

The material showed different conductive behavior depending on the temperature and frequency range, where most of the samples followed tunneling effects of charge transport affected by the change in temperature, and this theory is supported by the fact that the material contains many transition elements in which electrons hope from one oxidation state to another. This phenomenon catalyzes the formation of polarons that directly affect conductivity. With increasing temperature, the conduction mechanism transitions to correlated barrier hopping, characterized by charge carriers traversing Coulomb barriers between adjacent defect centers through thermally activated processes. This effect is most pronounced in the sample with 3% HEO-850 filler. The tunable dielectric response of these materials, achieved through precise control of operating temperature and HEO filler concentration, stems from their intrinsic properties and diverse conduction mechanisms. This controllability, coupled with the material’s fundamental characteristics, suggests significant potential for high-performance capacitive applications. The ability to modulate electrical properties through straightforward environmental parameters demonstrates a promising pathway toward optimized dielectric performance.

Data availability

The data is available upon request from the corresponding author (252679@vutbr.cz).

References

Dąbrowa, J. et al. Formation of solid solutions and physicochemical properties of the high-entropy ln1-xsrx(co,cr,fe,mn,ni)o3-δ (ln = la, pr, nd, sm or gd) perovskites. Materials 14(18), 5264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14185264 (2021).

Park, N. Y. et al. High-energy cathodes via precision microstructure tailoring for next-generation electric vehicles. ACS Energy Lett. 6(12), 4195–4202. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.1c02281 (2021).

Witte, R. et al. Magnetic properties of rare-earth and transition metal based perovskite type high entropy oxides. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/50004125 (2020).

Liang, Z. et al. Solution-processed high entropy metal oxides as dielectric layers with high transmittance and performance and application in thin film transistors. Surfaces Interfaces 40, 103147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103147 (2023).

Fracchia, M., Coduri, M., Ghigna, P. & Anselmi-Tamburini, U. Phase stability of high entropy oxides: a critical review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 44(2), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2023.09.056 (2024).

Cieslak, J. et al. Magnetic properties and ionic distribution in high entropy spinels studied by mossbauer and ab initio methods. Acta Mater. 206, 116600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2020.116600 (2021).

Anand, G., Wynn, A. P., Handley, C. M. & Freeman, C. L. Phase stability and distortion in high-entropy oxides. Acta Mater. 146, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.12.037 (2018).

Liu, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Bao, A. & Qi, X. Effects of fe2+ on dielectric and magnetic properties in rare earth garnet type high entropy oxides. Ceram. Int. 50(15), 27453–27461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.044 (2024).

Dallaev, R., Spusta, T., Allaham, M. M., Spotz, Z. & Sobola, D. Synthesis and band gap characterization of high-entropy ceramic powders. Crystals 14(4), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst14040295 (2024).

Ravichandran, R., Wang, A. X. & Wager, J. F. Solid state dielectric screening versus band gap trends and implications. Opt. Mater. 60, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2016.07.027 (2016).

Herve, P. & Vandamme, L. General relation between refractive index and energy gap in semiconductors. Infrared Phys. amp Technol. 35(4), 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/1350-4495(94)90026-4 (1994).

Zhang, L. et al. Dynamics of photoexcited small polarons in transition-metal oxides. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12(9), 2191–2198. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00003 (2021).

Ortmann, F., Bechstedt, F. & Hannewald, K. “Charge transport in organic crystals: Theory and modelling. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 248(3), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201046278 (2010).

Di Valentin, C., Pacchioni, G. & Selloni, A. Reduced and n-type doped tio2: Nature of ti3+ species. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(48), 20543–20552. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9061797 (2009).

Miyata, K. et al. Large polarons in lead halide perovskites. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701217 (2017).

Zheng, Z., Ji, H., Zhang, Y., Cai, J. & Mo, C. High-entropy (ca0.5ce0.5)(nb0.25ta0.25mo0.25w0.25)o4 scheelite ceramics with high-temperature negative temperature coefficient (ntc) property for thermistor materials. Solid State Ionics 377, 115872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssi.2022.115872 (2022).

Koo, J. H. et al. A vacuum-deposited polymer dielectric for wafer-scale stretchable electronics. Nat. Electron. 6(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-023-00918-y (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Polymer-based dielectrics with high permittivity and low dielectric loss for flexible electronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 10(16), 6196–6221. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2TC00193D (2022).

Li, R. et al. Giant dielectric tunability in ferroelectric ceramics with ultralow loss by ion substitution design. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48264-7 (2024).

Nan, C.-W., Shen, Y. & Ma, J. Physical properties of composites near percolation. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 40(1), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104529 (2010).

Qian, M. et al. Enhanced mechanical and dielectric properties of natural rubber using sustainable natural hybrid filler. Appl. Surface Sci. Adv. 6, 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100171 (2021).

Wu, S. Q. et al. An approach to developing enhanced dielectric property nanocomposites based on acrylate elastomer. Mater. Design 146, 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2018.03.023 (2018).

Zhao, X. et al. Excellent high-temperature dielectric energy storage performance in bilayer nanocomposites with high-entropy ferroelectric oxide fillers. Nat. Commun. 16, 5570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60683-8 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Polymer-based dielectric composite films with excellent dielectric energy storage and thermal management capabilities. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202512371 (2025).

Bérardan, D., Franger, S., Dragoe, D., Meena, A. K. & Dragoe, N. Colossal dielectric constant in high entropy oxides. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 10, 328–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.201600043 (2016).

Maxwell, J. C. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Sillars, R. The properties of a dielectric containing semiconducting particles of various shapes. J. Inst. Electr. Eng. 80(484), 378–394 (1937).

Yan, Z. et al. Strengthening waterborne acrylic resin modified with trimethylolpropane triacrylate and compositing with carbon nanotubes for enhanced anticorrosion. Adv. Composit. Hybrid Mater. 5(3), 2116–2130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00554-8 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Synergistic impact of cellulose nanocrystals with multiple resins on thermal and mechanical behavior. Zeitschrift fur Phys. Chem. 235(10), 1247–1262. https://doi.org/10.1515/zpch-2020-1697 (2020).

Jawad, I., Al-Hamdani, A. A. & Hasan, R. Fourier transform infrared (ft-ir) spectroscopy of modified heat cured acrylic resin denture base material. Int. J. Enhanced Res. Sci. Technol. Eng. 5(4), 130–140 (2016).

Taylor, P. & Frank, S. Low temperature polymerization of acrylic resins. J. Dent. Res. 29(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345500290041101 (1950).

Esmaeilzaei, A., Vahdati Khaki, J., Sajjadi, S. A. & Mollazadeh, S. Synthesis and crystallization of (co, cr, fe, mn, ni)3o4 high entropy oxide: The role of fuel and fuel-to-oxidizer ratio. J. Solid State Chem. 321, 123912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2023.123912 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Effects of mixing enthalpy and cooling rate on phase formation of alxcocrcufeni high-entropy alloys. Materialia 6, 100292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2019.100292 (2019).

Woodward, W. H. H. Broadband dielectric spectroscopy: A practical guide. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2021-1375.ch001 (2021).

Lvovich, V. F. Impedance Spectroscopy: Applications to Electrochemical and Dielectric Phenomena (Wiley, 2012).

Volkov, A. S., Koposov, G., Perfil’ev, R. & Tyagunin, A. Analysis of experimental results by the havriliak–negami model in dielectric spectroscopy. Opt. Spectrosc. 124, 202–205 (2018).

Havriliak, S. & Negami, S. A complex plane analysis of dispersions in some polymer systems. Journal of Polymer Science Part C: Polymer Symposia 14(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/polc.5070140111 (1966).

Kalmykov, Y. P. Recent Advances in Broadband Dielectric Spectroscopy (Springer, 2012).

Krzysztof Kamil Żur, S. A. F. Nanomechanics of Structures and Materials (Elsevier, 2024).

Killias, H. Temperature-dependent arrhenius factor for small-polaron conduction in glasses. Phys. Lett. 20(1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9163(66)91022-5 (1966).

Zhang, L. & Tang, Z.-J. Polaron relaxation and variable-range-hopping conductivity in the giant-dielectric-constant material cacu3ti4o12. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.70.174306 (2004).

Kirkpatrick, S. Percolation and conduction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 45(4), 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.45.574 (1973).

Pecharromán, C. & Moya, J. S. Experimental evidence of a giant capacitance in insulator conductor composites at the percolation threshold. Adv. Mater. 12(4), 294–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1521-4095(200002)12 (2000).

Song, Y., Noh, T. W., Lee, S.-I. & Gaines, J. R. Experimental study of the three-dimensional ac conductivity and dielectric constant of a conductor-insulator composite near the percolation threshold. Phys. Rev. B 33(2), 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.33.904 (1986).

Kwon, S., Cho, H. W., Gwon, G., Kim, H. & Sung, B. J. Effects of shape and flexibility of conductive fillers in nanocomposites on percolating network formation and electrical conductivity. Phys. Rev. E https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.93.032501 (2016).

Mamunya, E. P., Davidenko, V. V. & Lebedev, E. V. Percolation conductivity of polymer composites filled with dispersed conductive filler. Polym. Compos. 16(4), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.750160409 (1995).

Rajput, S., Parida, S. & Sharma Sonika, A. Dielectric Materials for Energy Storage and Energy Harvesting Devices (CRC Press, 2023).

Dong, M. et al. Explanation and analysis of oil-paper insulation based on frequency-domain dielectric spectroscopy. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 22(5), 2684–2693. https://doi.org/10.1109/tdei.2015.005156 (2015).

Tang, R. et al. Dielectric relaxation, resonance and scaling behaviors in sr3co2fe24o41 hexaferrite. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13645 (2015).

Singh, S., Kaur, A., Kaur, P. & Singh, L. High-temperature dielectric relaxation and electric conduction mechanisms in a lacoo3-modified na0.5bi0.5tio3 system. ACS Omega 8(28), 25623–25638. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04490 (2023).

Zhao, B. et al. High entropy enhanced microwave attenuation in titanate perovskites. Adv. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202210243 (2023).

Fan, L. et al. High entropy dielectrics. J. Adv. Dielectr. 13(5), 2350014 (2023).

Yang, X., Hu, J., Chen, S. & He, J. Understanding the percolation characteristics of nonlinear composite dielectrics. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30597 (2016).

Barber, P. et al. Polymer composite and nanocomposite dielectric materials for pulse power energy storage. Materials 2(4), 1697–1733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma2041697 (2009).

Jha, P. K., Jha, P. A., Kumar, P., Asokan, K. & Dwivedi, R. K. Defect induced weak ferroelectricity and magnetism in cubic off-stoichiometric nano bismuth iron garnet: effect of milling duration. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 25(2), 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-013-1628-x (2013).

Mahato, D. K., Dutta, A. & Sinha, T. P. Dielectric relaxation in double perovskite oxide, ho2cdtio6. Bull. Mater. Sci. 34(3), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-011-0109-1 (2011).

Farag, A., Mansour, A., Ammar, A., Rafea, M. A. & Farid, A. Electrical conductivity, dielectric properties and optical absorption of organic based nanocrystalline sodium copper chlorophyllin for photodiode application. J. Alloy. Compd. 513, 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.10.058 (2012).

Krupka, J. et al. Measurements of permittivity, dielectric loss tangent, and resistivity of float-zone silicon at microwave frequencies. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 54(11), 3995–4001. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.2006.883655 (2006).

Dyre, J. C. The random free-energy barrier model for ac conduction in disordered solids. J. Appl. Phys. 64(5), 2456–2468. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.341681 (1988).

Elkestawy, M., Abdel Kader, S. & Amer, M. Ac conductivity and dielectric properties of ti-doped cocr1.2fe0.8o4 spinel ferrite. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 405(2), 619–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2009.09.076 (2010).

Dubey, A. K., Singh, P., Singh, S., Kumar, D. & Parkash, O. Charge compensation, electrical and dielectric behavior of lanthanum doped cacu3ti4o12. J. Alloy. Compd. 509(9), 3899–3906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.12.156 (2011).

Maity, S., Bhattacharya, D. & Ray, S. K. Structural and impedance spectroscopy of pseudo-co-ablated (srbi2ta2o9)(1–x)-(la0.67sr0.33mno3)x composites. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 44(9), 095403. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/44/9/095403 (2011).

Marple, M. A. T., Avila-Paredes, H., Kim, S. & Sen, S. Atomistic interpretation of the ac-dc crossover frequency in crystalline and glassy ionic conductors. J. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5026685 (2018).

Jonscher, A. K. A new understanding of the dielectric relaxation of solids. J. Mater. Sci. 16(8), 2037–2060. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00542364 (1981).

Hamdi, M., Shuheil, M. A. & Oueslati, A. Synthesis, morphological, and ionic conductivity of a lithium cerium diphosphate compound. Ionics 30(6), 3691–3703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-024-05516-2 (2024).

Chamuah, A., Ojha, S., Bhattacharya, K., Ghosh, C. K. & Bhattacharya, S. Ac conductivity and electrical relaxation of a promising ag2s-ge-te-se chalcogenide glassy system. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 166, 110695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.110695 (2022).

Karmakar, S., Tyagi, H., Mohapatra, D. & Behera, D. Dielectric relaxation behavior and overlapping large polaron tunneling conduction mechanism in nio–pbo µ-cauliflower composites. J. Alloy. Compd. 851, 156789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.156789 (2021).

Ahmad, S. I. et al. Dielectric, impedance, ac conductivity and low-temperature magnetic studies of ce and sm cosubstituted nanocrystalline cobalt ferrite. J. Magnet. Magnet. Mater. 492, 165666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2019.165666 (2019).

Allison, A. & Andreas, H. Minimizing the nyquist-plot semi-circle of pseudocapacitive manganese oxides through modification of the oxide-substrate interface resistance. J. Power Sour. 426, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.04.029 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by GAČR (Grant No. 23-06856S). CzechNanoLab project LM2023051 funded by MEYS CR is gratefully acknowledged for the financial support of the measurements/sample fabrication at CEITEC Nano Research Infrastructure. The research described in the paper was financially supported by the Internal Grant Agency of the Brno University of Technology, grant number CEITEC VUT/FEKT-J-25-8865.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Grantová agentura České republiky (GAČR) (Grant No. 23-06856S). CzechNanoLab project LM2023051 funded by Ministerstvo školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy České republiky (MEYS CR) is gratefully acknowledged for the financial support of the measurements/sample fabrication at CEITEC Nano Research Infrastructure. The research described in the paper was financially supported by the Internal Grant Agency of the Brno University of Technology, grant number CEITEC VUT/FEKT-J-25-8865.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samer I. Daradkeh: Writing Manuscript, Reviewing , Data acquisition, Data analysis, Sample preparation Ammar Al-soud: Writing, Reviewing, Data analysis Tomáš Spusta : Sample preparation, Reviewing Vaclav Pouchlý : Reviewing , Funding acquisition Alexandr Knápek : Reviewing Pavel Tofel : Reviewing Dinara Sobola : Reviewing , Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daradkeh, S.I., Alsoud, A., Spusta, T. et al. Thermal and filler concentration modulation of charge transport mechanism and dielectric properties in high-entropy oxide (CoCrFeNiMn)3O4-acrylic polymer composite. Sci Rep 16, 7309 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38245-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38245-9