Abstract

In this study, a novel hybrid electrode of phosphidated tungsten oxide (WO₃–P) and polyaniline (PANI) is synthesized on a nickel foam substrate (PANI@WO3-P/NF). The hierarchical structure combines the pseudocapacitive properties of WO₃–P with the high conductivity and redox activity of PANI, while the 3D porous nickel foam enhances electron transport and electrolyte access. The synergistic PANI@WO3-P interaction significantly improves the electrochemical performance, delivering a specific capacity of 1210 C g− 1 at 1 A g− 1 and retaining 90.85% capacitance after 10,000 cycles, ideal for energy storage. Asymmetric two-electrode device achieves an energy density of 60.44 Wh kg⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹ with a power density of 637.21 W kg⁻¹, underscoring its supercapacitor (SC) potential. In addition, platinum (Pt) electrodeposition enhances the catalytic activity of the PANI@WO₃-P/NF electrode for methanol oxidation, paving the way for advanced energy conversion in next-generation direct methanol fuel cells. The maximum current density reaches 19.85 mA mg⁻1 Pt, and the electrode retains 80.64% of its original activity even after 1000 cycles, demonstrating that the Pt/PANI@WO-P/NF electrode has good stability. This versatile dual-functional hybrid electrode platform uniquely combines high-performance Pt-free supercapacitor behavior with remarkable electrocatalytic MOR activity achieved through minimal Pt modification, highlighting its potential for advanced multifunctional energy applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global demand for sustainable energy solutions has spurred the development of advanced materials capable of addressing both energy storage and conversion challenges1,2. With increasing requirements for high-performance energy systems, materials capable of serving dual roles in supercapacitors and fuel cells have garnered significant attention3. Supercapacitors demand electrode materials with high specific capacitance, excellent cycling stability, and rapid charge transfer, while direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) require electro catalysts with outstanding activity and durability for methanol oxidation4,5,6,7. Developing multifunctional materials that can simultaneously fulfill these roles is critical for advancing next-generation energy technologies8. By integrating highly conductive frameworks with materials possessing strong redox and catalytic properties, such hybrid structures can bridge the gap between energy storage and conversion, offering scalable and versatile platforms for practical applications9,10. Recent studies have explored a novel hybrid electrode material capable of effective operation in both supercapacitor and DMFC systems, opening new possibilities for integrated energy devices with improved efficiency and multifunctionality11,12.

Transition metal oxides, such as tungsten oxide (WO₃), nickel–manganese oxide, nickel-manganese sulfide have been extensively investigated for their remarkable theoretical capacitance and rich redox chemistry, which enable efficient energy processes13,14,15,16. The crystal structure of WO₃ consists of corner-sharing WO₆ octahedral and can exist in several distinct polymorphs, ranging from low-symmetry monoclinic and triclinic phases to higher-symmetry tetragonal, orthorhombic, hexagonal, and cubic structures. Owing to its outstanding properties, WO₃ is widely recognized as a smart window material, making the development of facile and scalable synthesis methods highly desirable17. Reported synthesis approaches include microwave-assisted, solvothermal, electrochemical, chemical, thermal, sol–gel, and solid-state techniques, each offering specific advantages and limitations in terms of crystal growth control (shape and size), processing temperature, impurity levels, product yield, and homogeneity18,19,20. In particular, the construction of heterostructures through the incorporation of other transition metal compounds can create hetero interfaces that facilitate electron redistribution, thereby enhancing the electrocatalytic performance of transition metal oxides21. Notable examples of WO₃-based heterostructures include WS2–WO3, ZnIn2S4/WO3, WO3-P, and WO3/Bi2WO6 systems22,23,24,25.

To further enhance the electrochemical and catalytic properties, phosphidation of WO₃ was employed to form tungsten phosphide (WO₃–P), a transition metal phosphide known for its metallic conductivity, chemical stability, and abundant active sites26,27. Despite these promising electrochemical properties, the practical application of transition metal phosphide is significantly hindered by intrinsic drawbacks including poor electrical conductivity, which limits electron transport within the electrode, and structural instability during prolonged charge–discharge cycling, leading to capacity fading and reduced device lifespan28,29,30. These challenges necessitate the development of composite materials or surface modifications to enhance their conductivity and mechanical robustness for reliable long-term operation in energy storage and conversion devices.

Conductive polymers like PANI provide excellent electrical conductivity, environmental stability, and pseudocapacitive behavior, which can synergistically improve the electrochemical performance of metal oxides when combined in hybrid structures31,32,33,34. This polymer can be readily synthesized on diverse substrates, yielding a homogeneous, conductive, and strongly adherent thick film. Coating an electrode with PANI enhances surface wettability, facilitates the deposition of metal catalysts, and creates a catalytically active surface35,36. Additionally, nickel foam (NF) serves as an ideal three-dimensional scaffold, offering high conductivity, large surface area, and porous architecture that facilitate efficient ion diffusion and charge transport37,38. This phosphidated PANI@WO₃–P hybrid electrode thus integrates capacitive energy storage with catalytic activity, and when further modified with a noble metal such as platinum, it exhibits enhanced electro catalytic performance for methanol oxidation, making it a versatile platform for advanced supercapacitor and direct methanol fuel cell (DMFC) applications39,40. For the methanol oxidation reaction (MOR), the selection of an appropriate electrocatalyst is critical due to the complex multistep reaction pathway involving C–H bond cleavage and the formation of strongly adsorbed carbonaceous intermediates. Among various noble and non-noble catalysts, platinum remains the benchmark material for MOR owing to its unique electronic structure, which enables efficient adsorption and activation of methanol molecules as well as effective oxidation of CO-like poisoning species41,42. Compared with alternative catalysts such as Pd-, Ni- or transition-metal-based systems, Pt exhibits superior intrinsic activity, faster reaction kinetics, and higher durability under alkaline conditions, making it particularly suitable for DMFC applications.

In this work, a multifunctional electrode platform was developed that effectively integrates energy storage and energy conversion functionalities. A hybrid PANI@WO₃–P electrode grown on NF was synthesized, exhibiting high capacitive performance and good cycling stability, demonstrating its suitability for supercapacitor applications. To extend the functionality toward methanol oxidation, platinum nanoparticles were subsequently deposited onto the same framework, resulting in the Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode. In this configuration, Pt acts exclusively as the electrocatalytic component, while WO₃–P and PANI are responsible for charge storage. The synergistic interactions between Pt, PANI, and WO₃–P promote efficient charge transfer and help mitigate poisoning effects during methanol oxidation, enabling enhanced catalytic activity with low Pt loading. Importantly, supercapacitor performance was intentionally evaluated using the Pt-free electrode to avoid unnecessary cost and to maintain a true assessment of the intrinsic pseudocapacitive behavior of the WO₃–P/PANI hybrid. Overall, this dual-function electrode concept provides a practical approach toward designing integrated systems capable of both efficient energy storage and effective fuel oxidation, offering useful prospects for future sustainable energy technologies.

Result and discussion

Characterization

The surface morphology of the synthesized electrode materials was investigated by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). In the first stage (Fig. 1A–C), WO₃ nanostructures grown on the NF substrate exhibited a distinct nanorod bundle morphology with faceted polyhedral surfaces, indicative of well-defined crystal growth during the hydrothermal process. In the acidic precursor solution, Na₂ WO₄·2 H₂O is converted to tungstic acid (H₂WO₄). Oxalic acid acts as a chelating and structure-directing agent, regulating nucleation and promoting growth of WO₃. Meanwhile, SO₄²⁻ ions from (NH₄)2SO₄ selectively adsorb on specific crystal facets of WO₃, favoring anisotropic growth along the c-axis. As a result, WO₃ nanorods with diameters of ~ 150–350 nm is formed and assembled into bundled structures via oriented attachment, consistent with sulfate-assisted hydrothermal WO₃ growth reported in the literature43. During high-temperature (800 °C) phosphidation under Ar, phosphorus vapor partially converts WO₃ into WP, forming a hybrid WO₃–P phase. The elevated temperature and oxide-to-phosphide lattice transformation induce surface reconstruction and strain-driven reorganization, transforming bundled nanorods into more separated and aligned arrays. This reconstruction enhances structural uniformity and active surface exposure, consistent with reported phosphidation-induced morphological evolution in metal oxides44. The WO₃ layer remains thermally stable at 800 °C and acts as a protective coating, preventing significant oxidation or mechanical degradation of the NF substrate under the controlled inert Ar atmosphere, consistent with literature on high temperature phosphidation of metal oxides/phosphides on NF. Upon phosphidation, this morphology transformed into well-aligned nanorod arrays (Fig. 1D–F), confirming the successful conversion of WO₃ to tungsten phosphide (WO₃–P) and improved structural uniformity. This morphological shift enhances surface accessibility and facilitates electron transport, while the open architecture of the nanorod arrays supports better ion diffusion and increases the electroactive surface area key factors for improved energy storage and catalytic activity.

Subsequent electrochemical polymerization of PANI on the WO₃–P/NF surface resulted in an interconnected polymeric network clearly observed across the nanostructures (Fig. 1G–I). Cyclic voltammetry drives anodic oxidation of aniline to radical cations, followed by head-to-tail coupling, chain propagation, and protonation/doping in acidic medium, forming a thin conductive emeraldine salt network. The rough WO₃–P surface provides abundant nucleation sites (via oxygen/phosphorus groups), templating uniform PANI adhesion without disrupting the nanorod array. The PANI layer improved electrical conductivity and added pseudocapacitance via its redox activity, while also contributing mechanical flexibility and structural integrity, which are critical for long-term cycling performance in supercapacitor systems. Finally, platinum nanoparticles were electrochemically deposited onto the PANI@WO₃–P/NF composite (Fig. 1J–L). Chronoamperometric reduction of [PtCl₆]²⁻ deposits discrete Pt nanoparticles. PANI’s amine/nitrogen groups serve as preferential nucleation sites, promoting even dispersion and preventing agglomeration through coordination interactions. FESEM images revealed a uniform dispersion of Pt nanoparticles on the PANI matrix, confirming their successful incorporation. This final architecture was specifically designed to enhance electrocatalytic activity for methanol oxidation in DMFCs, offering an integrated platform for dual-function energy applications. This sequential evolution, schematically illustrated in new (Figure S1), fabricates a hierarchical architecture with synergistic benefits for ion/electron transport and active site accessibility.

To better demonstrate the elemental composition and spatial distribution, EDS elemental mapping analyses were performed for both PANI@WO₃–P/NF and Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrodes. As shown in Figure S2, tungsten (W), phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), Pt and nickel (Ni) are homogeneously distributed across the electrode surfaces, confirming the successful formation of the PANI@WO₃–P hybrid structure on the nickel foam substrate. In addition, Pt is uniformly dispersed on the Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode without noticeable aggregation, indicating effective Pt deposition and strong interaction with the hybrid support. The uniform elemental distribution in both electrodes further confirms the structural integrity and effective hybridization of the composite architecture. Furthermore, elemental mapping images demonstrate a homogeneous spatial distribution of Pt nanoparticles across the PANI@WO₃–P framework, without noticeable aggregation, indicating effective nucleation and dispersion of Pt on the conductive polymer matrix. Cross-sectional FESEM images of the PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode (Figure S4A-B) reveal the hierarchical architecture, with WO₃–P nanorods uniformly coated by a thin PANI layer. The PANI coating thickness is estimated to be approximately 30–50 nm, forming a conformal, interconnected network that enhances conductivity and pseudocapacitive contributions without blocking the porosity or reducing electrolyte accessibility. This optimal thickness, achieved through controlled electrodeposition (30 CV cycles), ensures efficient electron transport from the conductive PANI to the WO₃–P while maintaining high surface area and mechanical flexibility of the hybrid structure. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the scraped PANI@WO₃–P sample (Figure S4 B-C) shows irregular, aggregated nanostructures with a denser inorganic core surrounded by a lower-contrast outer layer. This outer layer, attributed to the electrodeposited PANI, appears as an amorphous coating due to its polymeric nature, enveloping the phosphidated tungsten oxide particles. The composite structure confirms successful integration of PANI with the WO₃–P material, providing enhanced conductivity and surface functionality while maintaining overall material accessibility. The observed aggregation is likely due to the scraping process during sample preparation from the NF substrate.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to investigate the surface chemical composition and elemental states of the PANI@WO-P/NF electrode before and after the long-term stability test for SC. Prior to stability testing, the XPS survey spectra revealed the presence of characteristic peaks corresponding to W 4f, P 2p, N 1 s, and C 1 s, confirming the successful integration of tungsten phosphide and polyaniline on the nickel foam substrate. As can be seen in Fig. 2A the high-resolution XPS spectrum of tungsten in the PANI@WO-P/NF electrode displays three well-defined peaks corresponding to the W 4f₇/₂, W 4f₅/₂, and W 5p₃/₂ orbitals.

Before the stability test, the W 4f doublet appears at binding energies of approximately ~ 31.68 eV (W 4f₇/₂) and ~ 33.3 eV (W 4f₅/₂), which are characteristic of W⁴⁺ and W⁶⁺ oxidation states. This indicates the coexistence of different tungsten valence states, consistent with partial surface oxidation of the phosphidated tungsten species (WO3-P). A weaker peak around ~ 35.5 eV is attributed to the W 5p₃/₂ orbital, further confirming the presence of tungsten-based compounds45. After the long-term stability test, a noticeable decrease in the intensity of all tungsten peaks is observed, and the overall signal becomes noisier. Despite this reduction in spectral clarity, the W 4f and W 5p peaks remain discernible, indicating that tungsten is still present on the surface and retains its oxidation state distribution. The decrease in intensity may be attributed to surface reconstruction or partial degradation under prolonged electrochemical operations. Nevertheless, the persistence of these peaks suggests that the WO3-P framework remains largely intact, demonstrating acceptable chemical stability during cycling. The high-resolution XPS spectrum of phosphorus (P) reveals three distinct peaks in the P 2p region. The main doublet at ~ 125.7 eV (P 2p₃/₂) and ~ 129.3 eV (P 2p₁/₂) corresponds to metal phosphide (P⁻) species, confirming the successful formation of WO3-P45. Additionally, a broader peak centered near ~ 134.5 eV is assigned to oxidized phosphorus species (P⁵⁺), suggesting partial surface oxidation likely due to air or electrolyte exposure as shown in Fig. 2B. After the stability test, a noticeable decrease in the intensity of this oxidized phosphorus peak was observed, indicating loss of unstable P⁵⁺ species. Meanwhile, the metal phosphide peaks remained detectable, implying that the core phosphide structure was retained and remained chemically stable during prolonged electrochemical operation. As can be seen in Fig. 2C the high-resolution N 1 s spectrum of the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode can be deconvoluted into four distinct peaks. The peaks located at 396.7 and 398.6 eV correspond to the quinoid imine (= N–) and benzenoid amine (–NH–) nitrogen species, respectively, which are characteristic of the intrinsic redox structure of polyaniline. The additional peaks at 399.8.2 and 401.1 eV are attributed to cationic nitrogen species (N⁺), including protonated imine (–NH⁺) and positively charged amine units, reflecting the doped and conductive state of PANI46. After the stability test, the overall N 1 s signal showed a slight decrease in intensity, particularly in the quinoid and cationic nitrogen peaks, suggesting minor structural rearrangement or partial degradation of the PANI backbone under prolonged electrochemical cycling. Nevertheless, the preservation of all nitrogen species indicates that the conducting polymer network largely remains intact, maintaining its redox-active functionality. The high-resolution O 1 s spectrum exhibits three distinct peaks, each corresponding to specific oxygen species within the composite. The peak at 530.9 eV is assigned to P–O bonding, indicating the presence of oxidized phosphorus moieties. The signal at 531.1 eV is attributed to O–W interactions, confirming the incorporation of tungsten–oxygen structures in the hybrid. Additionally, a peak at 530.3 eV is related to surface hydroxyl groups (O–H), suggesting the presence of adsorbed water or hydroxyl species. These features verify the coexistence of phosphorus–oxygen, metal–oxygen, and hydroxyl interactions in the PANI@WO–P/NF electrode. After the stability test, the O 1 s spectrum still showed the main peaks, but with some intensity changes. The P–O peak (533.4 eV) slightly decreased, suggesting reduced surface oxidation. The O–W peak (531.1 eV) remained stable. The O–H peak (530.3 eV) increased, likely due to enhanced surface hydration after cycling as shown in Fig. 2D. BET surface analysis revealed mesoporous characteristics for both WO–P and PANI@WO–P electrodes, as indicated by type IV isotherms with distinct hysteresis loops. The surface area and average pore radius of WO–P were measured to be 24.7 m² g⁻¹ and 3.54 nm, respectively. Upon PANI modification, the surface area increased significantly to 57.7 m² g⁻¹ with an average pore radius of 4.04 nm (Table S1). These findings are consistent with the observed morphological features in FESEM analysis as shown in Fig. 1S (A-B).

Electrochemical behavior supercapacitor

The electrochemical energy storage performance of the electrodes was initially evaluated using a three-electrode system through cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) techniques, with a 1.0 M aqueous KOH solution as the electrolyte. After.

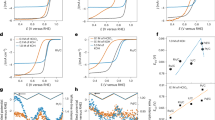

characterizing the morphology and composition of PANI@WO3-P/NF, WO₃–P/NF, PANI/NF and WO₃/NF, their electrocapacitive behaviors were further investigated by CV measurements at a scan rate of 20 mV s⁻¹, as illustrated in Fig. 3A. The CV curves of the systematically compared supercapacitor electrodes (WO₃/NF, WO₃P/NF, PANI/NF, and PANI@WO₃–P/NF) under identical conditions (scan rate 20 mV s⁻¹ in 1.0 M KOH) clearly demonstrate the progressive enhancement in pseudocapacitive behavior arising from individual components and their synergy (Fig. 3A). The bare NF substrate shows negligible current response, confirming its role solely as a conductive current collector. The WO₃/NF electrode exhibits weak redox features attributable to limited W⁶⁺/W⁵⁺/W⁴⁺ transitions in pristine tungsten oxide. Phosphidation markedly improves the response in WO₃–P/NF, with broader and more intense redox peaks due to enhanced electrical conductivity and additional active sites from metallic tungsten phosphide phases. The PANI/NF electrode displays characteristic PANI redox couples (leucoemeraldine ↔ emeraldine ↔ pernigraniline transitions), reflecting its own pseudocapacitive contribution. The PANI@WO₃–P/NF hybrid, however, integrates and amplifies these features, showing the largest enclosed CV area and highest peak currents. Specifically, the anodic peaks are observed at approximately 0.40–0.47 V and cathodic peaks at 0.28–0.32 V across the active electrodes, with the PANI@WO₃–P/NF exhibiting the most symmetric and well-defined redox pairs centered at ~ 0.44 V (oxidation) and ~ 0.31 V (reduction). These peak positions are associated with overlapping faradaic processes: reversible redox transitions of phosphidated tungsten species (W⁶⁺/W⁵⁺/W⁴⁺) in the WO₃–P core and the multiple oxidation states of the conductive emeraldine form of PANI. The significantly larger current response of the hybrid electrode highlights the synergistic interfacial effects beyond simple additive contributions. Quantitative analysis of the CV-integrated charge yields specific capacities of 1300.67 C g⁻¹ for PANI@WO₃–P/NF, substantially higher than 994.5 C g⁻¹ for WO₃–P/NF, 533.9 C g⁻¹ for WO₃/NF and 376.2 C g⁻¹ for PANI/NF. This stepwise improvement unequivocally demonstrates that phosphidation enhances the intrinsic activity of tungsten oxide, PANI provides additional redox capacitance and conductivity, and their intimate integration in the hierarchical PANI@WO₃–P/NF architecture maximizes electroactive surface utilization and charge transfer kinetics, resulting in superior pseudocapacitive performance.

The charge-discharge performance of the supercapacitor electrode based on the PANI@WO3-P/NF hybrid as the electroactive material was evaluated through GCD measurements at a current density of 1 A g⁻¹, as shown in Fig. 3B. The PANI@WO3-P/NF electrode exhibits nearly symmetrical charge and discharge curves with a prolonged discharge time of 1151.1 s, corresponding to a high capacitance value of 1210 C g⁻¹, indicating excellent charge-discharge characteristics. In comparison, the WO₃–P/NF, WO₃/NF and PANI/NF electrodes display shorter discharge times of 941, 499.7 and 361.2 s, with capacitance values of 931, 498 and 354 C g⁻¹, respectively. However, the GCD curves shown in Fig. 3B for the SC electrodes based on WO₃–P/NF and WO₃/NF display less symmetrical shapes and notably longer charge durations compared to the PANI@WO3-P/NF-based electrode. The superior capacitance of the PANI@WO3-P/NF electrode highlights the synergistic effect of combining the pseudocapacitive WO₃–P/NF, PANI/NF and WO₃/NF, which promote highly capacitive redox reactions and enhanced electron transfer.

Moreover, the incorporation of PANI helps reduce the restacking of WO3-P nanosheets, thereby significantly increasing the electroactive surface area between the electrode and electrolyte. To further evaluate the reversibility of the PANI@WO3-P/NF electrode, CV measurements were conducted at scan rates ranging from 5 to 200 mV s⁻¹, as shown in Fig. 3C.

All CV curves in Fig. 3C maintain similar shapes without distortion, even when the scan rate is increased by 40 times, demonstrating excellent reversibility. As the scan rate rises, the separation between redox peaks also increases, which is a typical behavior in electrochemical systems. Although the hybrid electrode combines two distinct materials, the improved conductivity and electrocapacitive properties of the PANI@WO3-P/NF structure help preserves the reversibility of the supercapacitor. The charge-discharge curves shown in Fig. 3D are highly symmetrical, reflecting the outstanding charge/discharge stability of the PANI@WO3-P/NF electrode. The maximum capacitance value of 1210 C g⁻¹ was achieved at a current density of 1 A g⁻¹, while capacitance values of 890 and 850 C g⁻¹ were obtained at 10 and 20 A g⁻¹, respectively. Notably, a 20-fold increase in current density resulted in only a 70.24% decrease in capacitance, highlighting the electrode’s excellent performance under high-rate charge/discharge conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 3E. The decrease in specific capacitance at higher current densities can be attributed to kinetic limitations and restricted ion diffusion. At elevated currents, electrolyte ions primarily access the outer surface of the electrode, resulting in incomplete utilization of electroactive sites within the bulk. Nevertheless, the electrode retains a substantial portion of its capacitance, reflecting efficient charge transport and favorable ion diffusion enabled by the conductive PANI framework and porous structure.

The interfacial charge transfer properties of the synthesized electrodes were analyzed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). As depicted in the Nyquist plots in Fig. 3F, all samples including bare NF, WO₃/NF, WO3–P/NF, and PANI@WO3–P/NF-display distinct semicircles in the high-frequency region corresponding to the charge transfer resistance (Rct), while the intercepts on the x-axis indicate the series resistance (Rs). The measured Rct values decreased progressively from 195.65 Ω for bare NF to 135.8 Ω for WO₃/NF, 64.4 Ω for WO3–P/NF, and further down to 21.45 Ω for PANI@WO3–P/NF. This significant reduction highlights the enhanced interfacial conductivity achieved with each modification, especially due to the incorporation of conductive PANI, which promotes faster electron transport at the interface.

(A) Assessment of the electrochemical performance of the electrodes in a 3-electrode cell configuration. CV curves of (a) PANI@WO3-P/NF, (b) PANI/NF, (c) WO₃–P/NF and (d) WO₃/NF electrodes at a scan rate of 20 mV s− 1 in 1.0 M KOH solution. (B) GCD profiles of the (a) PANI@WO3-P/NF, (b) PANINF, (c) WO₃–P/NF and (d) WO₃/NF electrodes at 1 A g− 1. (C) CV curves of the PANI@WO-P/NF electrode at different scan rates. (D) GCD profiles of the PANI@WO-P/NF electrode at different specific currents from 1.0 to 20 A g− 1; (E) Rate capability study; specific capacity of the PANI@WO-P/NF electrode at various specific currents. (F) EIS spectrum of (a) PANI@WO-P/NF, (b) WO₃–P/NF (c) WO₃/NF and (d) NF electrodes with its equivalent circuit.

Meanwhile, the series resistance (Rs) remained nearly constant across all samples, indicating that bulk and contact resistances were not significantly affected by surface modifications. These findings confirm that the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode possesses superior charge transfer kinetics, making it a strong candidate for efficient energy storage and conversion applications. The charge storage mechanism of the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode was further examined through CV at scan rates between 5 and 40 mV s⁻¹. As illustrated in Figure S6 (A-B), the peak current (i) versus scan rate (ν) was plotted on a log scale, and the slope (b-value) from the linear fit was used to determine the charge storage behavior. A b-value near 0.5 indicates a diffusion-controlled (battery-type) process, while a value close to 1, suggests a capacitive (surface-controlled) mechanism. For the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode, the calculated b-value of 0.62 indicates a mixed charge storage mechanism dominated by diffusion-controlled kinetics. This implies that ion diffusion within the electrode bulk significantly contributes to the electrochemical performance, while the redox-active PANI framework likely facilitates charge transport and structural stability, supporting the observed hybrid behavior. The stability test of the hybrid electrode, shown in Figure S6-C, further confirms a capacitance retention of 90.85% after 10,000 cycles at a current density of 9 A g⁻¹, highlighting excellent durability. The cycling stability of the bare PANI electrode was evaluated over 8000 charge–discharge cycles under identical electrochemical conditions. As shown in Figure S6D, the PANI electrode exhibits noticeably lower capacitance retention (79.3%) compared to the PANI @WO₃–PNF composite electrode. This inferior cycling stability can be attributed to the well-known limited chemical stability of PANI in alkaline electrolyte, including deprotonation and gradual loss of conductivity during prolonged cycling.

In the asymmetric supercapacitor configuration, the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode served as the positive electrode, while activated carbon (AC) was used as the negative electrode. Grade 42 Whatman paper acted as the separator with a 1.0 M KOH electrolyte. Figure 4A shows the stable voltage windows of the PANI@WO3–P/NF electrode (0.0 to 0.6 V) and AC electrode (0.0 to − 1.0 V), resulting in a total operating voltage of 1.6 V for the device. The optimized CV and GCD curves of the PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC hybrid supercapacitor at different potential windows up to 1.6 V (Fig. 4B and C) exhibit steadily increasing enclosed areas without any signs of oxygen evolution. The specific capacitance increases from 65.33 to 170 C g⁻¹ as the voltage window expands from 1.3 to 1.6 V CV curves of the hybrid cell (Fig. 4D) at scan rates from 5 to 100 mV s⁻¹ display quasi-rectangular shapes with redox peaks, confirming pseudocapacitive behavior. The Ragone plot (Fig. 4E) illustrates the device’s excellent performance, correlating energy density and power density across various current densities. The device delivers an energy density of 60.44 Wh kg⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹ with a power density of 637.21 W kg⁻¹, which remains 42.66 Wh kg⁻¹ at a power density of 6268.4 W kg⁻¹ at 10 A g⁻¹ representing the highest energy density reported among various WO₃ based electrode materials (Table S3). The hybrid cell’s stability test at 9 A g⁻¹ (Fig. 4F) demonstrates a capacitance retention of 87.14% after 10,000 cycles. Furthermore, the charging and discharging curves from the initial and final cycles, as depicted in (Fig. 4F), exhibited a consistent form, signifying the device’s exceptional cycling stability. Correspondingly, GCD profiles (Fig. 7S-A) recorded at current densities between 1 and 10 A g⁻¹ show asymmetric and nonlinear charge-discharge curves, characteristic of pseudocapacitance. A specific capacity of 170 C g⁻¹ is achieved at 1 A g⁻¹ and retains 120 C g⁻¹ at 10 A g⁻¹ (Fig. 7S-B). Furthermore, a practical PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC-based supercapacitor device was fabricated using nickel foam as the current collector. The two-round consecutive cycling stability studies at different specific currents of 2.0, 5.0, 10.0, and again of asymmetric device PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC device over 12,000 cycles (Fig. 7S-C). The assembled device successfully powered an LED light, as shown in Fig. 9S, highlighting its potential for practical energy storage and delivery applications.

Electrochemical characterization of the asymmetric device PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC. (A) Comparative of the AC/CC and PANI@WO3–P/NF electrodes in a 3E cell setup as well as the CV curve of the PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC device (at the sweep rate of 20 mV s− 1). (B and C) CV and GCD curves at different voltage windows of 0 to 1.6 V for the asymmetric device, respectively. (D) CV curves at different scan rates from 5 to 100 mV s− 1 for the PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC. (E) Ragone plot of PANI@WO3–P/NF//AC device. (F) Cycling stability of the PANI@WO₃–P/NF//AC device at a constant current of 9.0 A g⁻¹ over 10,000 cycles (left axis: capacitance retention (%); right axis: Coulombic efficiency (%); the inset shows the GCD curves of the initial and final cycles).

Electrochemical oxidation of methanol

The electrochemical properties of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF and Pt/NF electrodes were first evaluated in the absence of methanol. CV curves for both electrodes were recorded in 1.0 M KOH solution at a scan rate of 50 mV s⁻¹, as shown in Fig. 5A. Figure 5A presents the CVs of three electrodes (a) Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF, (b) Pt/PANI/NF, and (c) Pt/NF control in blank 1.0 M KOH (without methanol) over the potential range 0.0 to 0.8 V vs. Hg/HgO at 50 mV s⁻¹. The Pt/NF electrode shows negligible redox features in this window in contrast, both PANI-containing electrodes display characteristic Pt signatures: oxidation peaks near ~ 0.4 V corresponding to formation of a Pt oxide/hydroxide layer, and reduction peaks around ~ 0.28 V attributed to PtO/PtOH reduction. The significantly more pronounced peaks for Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF compared to Pt/PANI/NF indicate higher Pt utilization and electrochemically accessible surface area on the hybrid support.

The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) of Pt was estimated from the Pt oxide reduction peak in blank 1.0 M KOH using the formula:

where Q is the integrated coulombic charge of the PtO reduction peak (baseline-corrected) and mPt is the Pt loading determined by ICP-OES (152 ± 5 µg cm⁻² for a 1 cm² electrode). The calculated ECSA for Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF was (115.3 m² g⁻¹ Pt), significantly higher than that of the Pt/PANI/NF control (67.1 m² g⁻¹ Pt). This enhanced ECSA demonstrates superior Pt dispersion and utilization on the conductive PANI@WO₃–P hybrid support, which directly contributes to the higher mass-normalized activity (19.85 mA mg⁻¹ Pt) and improved CO tolerance observed during methanol oxidation. Figure 5B shows the CV responses of the same three electrodes in 0.5 M methanol + 1.0 M KOH. The Pt-free PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode exhibits essentially no anodic current in the examined potential range, demonstrating that the WO₃–P/PANI support alone possesses negligible intrinsic activity toward methanol oxidation. All Pt-containing electrodes, however, display typical MOR profiles with two well-defined oxidation peaks: the forward anodic peak (If) between ~ 0.4–0.7 V associated with methanol dehydrogenation and partial oxidation of adsorbed intermediates (COads, CHOads), and the backward peak (Ib) primarily due to further oxidation of residual carbonaceous species not fully removed during the forward scan.

The Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode delivers the highest mass-normalized forward peak current density of 19.85 mA mg⁻¹ Pt, approximately 2.37 times greater than that of the Pt/PANI/NF control (8.35 mA mg⁻¹ Pt) prepared under identical Pt deposition conditions. Additionally, the onset potential for MOR is more negative on Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF (~ 0.40 V vs. Hg/HgO) compared to Pt/NF (~ 0.50 V), reflecting facilitated methanol adsorption and activation. These marked improvements in mass activity, onset potential, and poisoning tolerance unequivocally demonstrate the synergistic role of the PANI@WO₃–P support in enhancing Pt dispersion, electronic conductivity, and bifunctional promotion (provision of OHads species from the oxide/phosphide component to accelerate CO oxidation). The absence of MOR activity on the Pt-free electrode rules out any significant catalytic contribution from the support alone, confirming that the observed performance originates exclusively from the well-integrated Pt nanoparticles. Figure 5C illustrates the CV plots at varying concentrations of methanol (a-f) in 1.0 M KOH for Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF. A distinct peak rises when the methanol concentration exceeds 0.05 M. The mass activity increases positively with rising methanol concentration (Fig. 5D), indicating a rapid methanol oxidation process. Moreover, the If/Ib ratios remain very stable when the concentrations of methanol vary from 0.10 to 1.00 M. The findings demonstrate a high tolerance for methanol and a substantial number of active sites for methanol adsorption and conversion. The long-term stability of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF in methanol oxidation was evaluated using chronoamperometry at a constant potential of + 0.5 V vs. Hg/HgO in 1.0 M KOH containing 0.5 M methanol for 4500 s (Fig. 5E). Both Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF and Pt/NF electrodes showed an initial sharp decline in current density, attributed to the rapid oxidation of pre-adsorbed methanol molecules, followed by a slower decay phase stabilizing after ~ 500 s. However, Pt/NF exhibited a continuous current decrease, retaining only 30% of its initial current after 4500 s, primarily due to poisoning by adsorbed CO species that block active sites. In contrast, Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF maintained a significantly higher current density throughout the test, reflecting enhanced durability and poisoning tolerance. This improved stability arises from the redox-active and conductive PANI@WO3–P matrix, which facilitates removal of poisoning intermediates and sustains efficient charge transport, preserving catalytic activity during extended operation. Durability was further demonstrated by cyclic voltammetry over 1000 cycles in 1.0 M KOH with 0.5 M methanol at 50 mV s⁻¹, where Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF retained 80.64% of its mass activity (Fig. 5F). CO tolerance was evaluated via CO-stripping experiments (Fig. 5G), where a stripping peak at 0.53–0.66 V appeared after CO adsorption and disappeared after purging with dry N₂ for 30 min. These results indicate that polyaniline chains reduce Pt ions to uniformly dispersed Pt particles (Pt-P) without external reducing agents. The PANI matrix enhances Pt-P dispersion by increasing surface area, preventing agglomeration, and improving methanol diffusion to catalytic sites. Additionally, the amine groups of PANI and WO3-P promote adsorption of water molecules, facilitating formation of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF-(OH)ads species that accelerate CO oxidation to CO₂ at ambient temperature. Increasing Pt-NP loading density further enhances accessible active sites, significantly improving methanol oxidation performance.

Conclusion

In summary, a novel PANI@WO₃–P/NF hybrid electrode was successfully fabricated through a straightforward multi-step synthesis, integrating the pseudocapacitive features of phosphidated tungsten oxide with the high conductivity and redox activity of PANI, supported by the 3D porous NF framework. The synergistic architecture delivered exceptional electrochemical performance, achieving a high specific capacity of 1210 C g⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹ and remarkable cycling stability with 90.85% capacitance retention after 10,000 cycles. The symmetric supercapacitor device demonstrated both high energy density (60.44 Wh kg⁻¹) and power density (637.21 W kg⁻¹), confirming its potential for advanced energy storage. Furthermore, Pt deposition significantly.

(A) CV of (a) Pt/PANI@WO–P/NF, (b) Pt/PANI/NF and (c) Pt/NF composites in 1.0 M KOH with scan rate of 50 mV s− 1; (B) CV curve MOR 1 st cycle (solid line) and 100th cycle (dash line) on (a) Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF, (c) Pt/PANI/NF and (d) PANI@WO3–P/NF catalysts from mixture of 0.5 M methanol and 1.0 M KOH in the potential range of 0.0 to 0.8 V (vs. Hg/HgO) with scan rate of 50 mV s− 1 at room temperature. (C) CV plots of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF in 1.0 M KOH in the presence of different concentrations of methanol (a-f): 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 M. (D) Relationship among mass activities, peak potential and methanol concentration. (E) CA study of synthesized (a) Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF and (b) Pt/NF catalysts in 0.5 M methanol-1.0 M KOH mixture at 0.6 V; (F) Initial and after 1000 cycle’s mass activities of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF. (G) CO stripping voltammograms study of Pt/PANI@WO3–P/NF in 1.0 M KOH electrolyte solution with scan speed of 50 mV s− 1.

boosted the electrode’s catalytic activity for methanol oxidation, yielding a maximum current density of 19.82 mA mg⁻1 and maintaining 80.64% activity after 1000 cycles, highlighting its durability for energy conversion. These results position the PANI@WO₃–P/NF hybrid electrode as a promising multifunctional platform, uniting high-performance super capacitive behavior with robust electrocatalytic properties, and paving the way for scalable next-generation energy storage and conversion technologies.

Experimental

Materials

Red phosphorus was obtained from Aladdin Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na₂WO₄·2 H₂O), hydrochloric acid (HCl), ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄), and oxalic acid (H₂C₂O₄) were purchased from MERCK. Aniline monomer and sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) used for polyaniline electrodeposition were also obtained from MERCK. Nickel foam (NF), used as the conductive substrate for electrode fabrication, was acquired from a commercial supplier and cleaned prior to use by ultrasonication in acetone, ethanol, and deionized water. Hexachloroplatinic acid (H₂PtCl₆) for platinum electrodeposition was of analytical grade. All reagents were used as received without further purification. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm) used throughout the experiments was purified with a Millipore Milli-Q system.

Synthesis of WO₃ nanostructures on nickel foam (WO₃/NF)

WO₃ nanostructures were synthesized on nickel foam via a hydrothermal method45,47. First, 12.5 mmol of Na₂ WO₄·2 H₂O was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water under vigorous stirring for 30 min. Then, a 3 M HCl aqueous solution was gradually added to the mixture until the pH reached 1.2, resulting in a yellowish transparent solution. Subsequently, 35 mmol of oxalic acid (H₂C₂O₄) was added, and the total volume was adjusted to 250 mL to form the H₂WO₄ precursor. A piece of nickel foam (cut into 1 cm × 1 cm) was sequentially cleaned by ultrasonication in acetone, ethanol, and deionized water. 40 mL of the prepared precursor solution and 2 g of (NH₄) ₂ SO₄ were transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, and the cleaned nickel foam was immersed into the solution. The autoclave was sealed and maintained at 180 °C for 16 h. After naturally cooling to room temperature, the sample was washed with deionized water and dried at 60 °C in air. Finally, the product was calcined in air at 450 °C for 1 h to obtain the WO₃ nanostructures.

Phosphidation of WO₃ to form WO₃–P (WO₃–P/NF)

To obtain phosphidated tungsten oxide (WO₃–P), the as-prepared WO₃-coated nickel foam and red phosphorus (molar ratio W: P = 1:5) were placed in separate zones of a porcelain boat, with red phosphorus located at the upstream side of a quartz tube furnace. The system was then purged with argon gas to create an inert atmosphere. The sample was heated to 800 °C and held for 60 min under static Ar flow, then allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The phosphidation process converted part of the WO₃ into tungsten phosphide (WP), forming a WO₃–P hybrid structure. The final loading of active material was determined to be approximately 2.0 mg cm⁻² using a high-precision microbalance44.

Electrodeposition of polyaniline (PANI) onto WO₃–P/NF

PANI was electrochemically deposited onto the surface of the phosphidated tungsten oxide electrode (WO₃–P/NF) via CV48. The electrodeposition was carried out in an aqueous solution containing 0.1 M aniline monomer and 1 M H₂SO₄ + 0.01 M LiClO4 as the supporting electrolyte. The WO₃–P/NF electrode was used as the working electrode, while a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and a platinum wire served as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. Cyclic voltammetry was performed within the potential window of 0.0 to 1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl at a scan rate of 20 mV s⁻¹ for 30 cycles. During the process, a uniform green PANI film was gradually formed on the surface of WO₃–P/NF, yielding the final hybrid electrode (PANI@WO₃–P/NF). After deposition, the electrode was rinsed with deionized water and dried at room temperature.

Electrochemical deposition of platinum on PANI@WO₃–P/NF

To further enhance the electrocatalytic activity, Pt nanoparticles were electrochemically deposited onto the surface of the PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode. The deposition was carried out in an aqueous solution of 1 mM hexachloroplatinic acid (H₂PtCl₆) using chronoamperometry. The PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode was employed as the working electrode, with a platinum wire as the counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference. The electrodeposition was performed by applying a constant potential of − 0.20 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 300 s. After the process, the resulting Pt/PANI@WO₃–P/NF electrode was thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and dried at room temperature. The presence of uniformly distributed Pt nanoparticles is expected to significantly enhance the electrocatalytic performance toward methanol oxidation in DMFC applications.

Data availability

All data from this study are presented in the article and the supplementary information, in the form of figures and tables.

References

Chu, S., Cui, Y. & Liu, N. The path towards sustainable energy. Nat. Mater. 16, 16–22 (2017).

Jefferson, M. Sustainable energy development: performance and prospects. Renew. Energy. 31, 571–582 (2006).

Dusastre, V. & Martiradonna, L. Materials for sustainable energy. Nat. Mater. 16, 15–15 (2017).

Zhang, L., Hu, X., Wang, Z., Sun, F. & Dorrell, D. G. A review of supercapacitor modeling, estimation, and applications: A control/management perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 1868–1878 (2018).

Iro, Z. S., Subramani, C. & Dash, S. A brief review on electrode materials for supercapacitor. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 11, 10628–10643 (2016).

Alias, M., Kamarudin, S., Zainoodin, A. & Masdar, M. Active direct methanol fuel cell: an overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 45, 19620–19641 (2020).

Kamarudin, S. K., Daud, W. R. W., Ho, S. L. & Hasran, U. A. Overview on the challenges and developments of micro-direct methanol fuel cells (DMFC). J. Power Sources. 163, 743–754 (2007).

Emin, A., Gong, B. & Jiang, H. Fish-scale-like NiMn-based layered double hydroxides for high-energy aqueous supercapacitors: A. Emin et al. Rare Met. 44, 7306–7316 (2025).

Islam, M. S., Mubarak, M. & Lee, H. J. Hybrid nanostructured materials as electrodes in energy storage devices. Inorganics 11, 183 (2023).

Dubal, D. P., Ayyad, O., Ruiz, V. & Gomez-Romero, P. Hybrid energy storage: the merging of battery and supercapacitor chemistries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 1777–1790 (2015).

Lee, K., Ferekh, S., Jo, A., Lee, S. & Ju, H. Effects of hybrid catalyst layer design on methanol and water transport in a direct methanol fuel cell. Electrochim. Acta. 177, 209–216 (2015).

Mousaabadi, K. Z., Ensafi, A. A., Adriyani, T. R. & Rezaei, B. Pd/Hemin-rGO as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for enhanced ethanol oxidation reaction in alkaline media and hydrogen evolution reaction in acidic media. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48, 21259–21269 (2023).

George, N. S., Jose, L. M. & Aravind, A. in Updates on SupercapacitorsIntechOpen, (2022).

Pervez, S. A. et al. Anodic WO3 mesosponge@ carbon: a novel binder-less electrode for advanced energy storage devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7, 7635–7643 (2015).

Emin, A. et al. Flexible free-standing electrode of nickel–manganese oxide with a cracked-bark shape composited with aggregated nanoparticles on carbon cloth for high-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 9637–9645 (2023).

Emin, A. et al. A flexible cathode of nickel-manganese sulfide microparticles on carbon cloth for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors with high comprehensive performance. J. Power Sources. 551, 232185 (2022).

Wu, X. & Yao, S. Flexible electrode materials based on WO3 nanotube bundles for high performance energy storage devices. Nano Energy. 42, 143–150 (2017).

Huirache-Acuña, R., Paraguay-Delgado, F., Albiter, M., Lara-Romero, J. & Martínez-Sánchez, R. Synthesis and characterization of WO3 nanostructures prepared by an aged-hydrothermal method. Mater. Charact. 60, 932–937 (2009).

Pinto, O. M. et al. Advances and challenges in WO3 nanostructures’ synthesis. Processes 12, 2605 (2024).

Modak, M., Rane, S. & Jagtap, S. WO3: a review of synthesis techniques, nanocomposite materials and their morphological effects for gas sensing application. Bull. Mater. Sci. 46, 28 (2023).

Emin, A. et al. An efficient electrodeposition approach for Preparing CoMn-hydroxide on nickel foam as high-performance electrodes in aqueous hybrid supercapacitors. Fuel 381, 133335 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Optimized catalytic WS2–WO3 heterostructure design for accelerated polysulfide conversion in lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000091 (2020).

Zhao, M. et al. A novel S-scheme 3D ZnIn2S4/WO3 heterostructure for improved hydrogen production under visible light irradiation. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 2615–2624 (2022).

Gao, M. et al. Tungsten phosphide microsheets In-Situ grown on carbon fiber as counter electrode catalyst for efficient Dye‐Sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 2201494 (2023).

Jia, Y. et al. Energy band engineering of WO3/Bi2WO6 direct Z-scheme for enhanced photocatalytic toluene degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 618, 156636 (2023).

Agarwal, A. & Sankapal, B. R. Metal phosphides: topical advances in the design of supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9, 20241–20276 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Confinement effect of mesopores: in situ synthesis of cationic tungsten-vacancies for a highly ordered mesoporous tungsten phosphide electrocatalyst. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 22741–22750 (2020).

Sun, M., Liu, H., Qu, J. & Li, J. Earth-rich transition metal phosphide for energy conversion and storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600087 (2016).

Feng, L. & Xue, H. Advances in transition-metal phosphide applications in electrochemical energy storage and catalysis. ChemElectroChem 4, 20–34 (2017).

Attarzadeh, N., Nuggehalli, R. & Ramana, C. Application of transition metal phosphides to electrocatalysis: an overview. Jom 74, 381–395 (2022).

Shi, Y., Peng, L., Ding, Y., Zhao, Y. & Yu, G. Nanostructured conductive polymers for advanced energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6684–6696 (2015).

Agobi, A. U., Louis, H., Magu, T. O. & Dass, P. M. A review on conducting polymers-based composites for energy storage application. J. Chem. Rev. 1, 19–34 (2019).

Ramli, Z. & Kamarudin, S. Platinum-based catalysts on various carbon supports and conducting polymers for direct methanol fuel cell applications: a review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 13, 410 (2018).

Adriyani, T. R., Ensafi, A. A. & Rezaei, B. Flexible and wearable electrode based on XG@ PAN/NCL/CC composite-coated on wearable supercapacitors for a wireless textile-based sweat sensor. J. Energy Storage. 113, 115664 (2025).

Dutta, K., Kumar, P., Das, S. & Kundu, P. P. Utilization of conducting polymers in fabricating polymer electrolyte membranes for application in direct methanol fuel cells. Polym. Rev. 54, 1–32 (2014).

Banerjee, J., Dutta, K., Kader, M. A. & Nayak, S. K. An overview on the recent developments in polyaniline-based supercapacitors. Polym. Adv. Technol. 30, 1902–1921 (2019).

Salleh, N. A., Kheawhom, S. & Mohamad, A. A. Characterizations of nickel mesh and nickel foam current collectors for supercapacitor application. Arab. J. Chem. 13, 6838–6846 (2020).

Emin, A. et al. Facile electrodeposition of CoMn2O4 nanoparticles on nickel foam as an electrode material for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta. 501, 144766 (2024).

Lyu, F., Cao, M., Mahsud, A. & Zhang, Q. Interfacial engineering of noble metals for electrocatalytic methanol and ethanol oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8, 15445–15457 (2020).

Koenigsmann, C. & Wong, S. S. One-dimensional noble metal electrocatalysts: a promising structural paradigm for direct methanol fuel cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1161–1176 (2011).

Şen, F. & Gökaǧaç, G. Activity of carbon-supported platinum nanoparticles toward methanol oxidation reaction: role of metal precursor and a new surfactant, tert-octanethiol. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 1467–1473 (2007).

Wang, H. et al. Influence of size-induced oxidation state of platinum nanoparticles on selectivity and activity in catalytic methanol oxidation in the gas phase. Nano Lett. 13, 2976–2979 (2013).

Peksoz, A., Killi, H., Tokgoz, S. R. & Carpan, M. A. Electrochemically fabrication of a composite electrode based on tungsten oxide and Cobalt on 3D Ni foam for high and stable electrochemical energy storage. Mater. Today Commun. 33, 104263 (2022).

Pu, Z., Liu, Q., Asiri, A. M. & Sun, X. Tungsten phosphide Nanorod arrays directly grown on carbon cloth: a highly efficient and stable hydrogen evolution cathode at all pH values. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 21874–21879 (2014).

Zonghua, P., Qian, L. & Xuping, S. Tungsten Phosphide Nanorod Arrays Directly Grown on Carbon Cloth: A Highly Efficient and Stable Hydrogen Evolution Cathode at All pH Values. (2014).

Zou, B. X., Liang, Y., Liu, X. X., Diamond, D. & Lau, K. T. Electrodeposition and pseudocapacitive properties of tungsten oxide/polyaniline composite. J. Power Sources. 196, 4842–4848 (2011).

Gao, L. et al. High-performance energy-storage devices based on WO 3 nanowire arrays/carbon cloth integrated electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 7167–7173 (2013).

Khalili, S., Afkhami, A. & Madrakian, T. Electrochemical simultaneous treatment approach: Electro-reduction of CO2 at Pt/PANI@ ZnO paired with wastewater electro-oxidation over PbO2. Appl. Catal. B. 328, 122545 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Isfahan University of Technology Research Council for support of this work.

Funding

The authors acknowledge of the Isfahan University of Technology Research Council for support of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Touba Rezaee Adriyani: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, and Writing-original draft. Ali A. Ensafi: Supervision, Methodology, Validation, Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adriyani, T.R., Ensafi, A.A. Phosphidated tungsten oxide@polyaniline hybrid electrode on nickel foam for dual-function supercapacitor and methanol oxidation. Sci Rep 16, 7008 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38573-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38573-w