Abstract

In pursuit of sustainability, it is necessary to comprehend the evolving relationship between economic growth and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This study conducts Index Decomposition Analysis (IDA) for comparative sectoral analysis of the world’s ten largest GHG emitting countries across their eight sectors; agriculture, building, fuel exploitation, industrial combustion, power industry, processes, transport and waste, using latest available data from 2000 to 2023. This study disaggregates sectoral emissions to evaluate the extent to which economic growth has been decoupled from GHG emissions, thereby offering insight into national sectoral emission trajectories and sustainability progress. This study offers sectoral ranking of countries based on average GHG emission abatement during 2000–2023 and offers the sectoral GHG emission intensity in these countries relative in year 2000. The agriculture and building sectors demonstrated significant decoupling, abatement of GHG emissions by an average of 6.44 MtCO2 and 6.34 MtCO2, respectively, through sustainable practices. The fuel exploitation sector achieved modest abatement of 2.24 MtCO2, though emissions intensified in China and Indonesia. In the industrial combustion sector, GHG emissions abatement were recorded by 0.74 MtCO2 but intensified in several emerging economies. The transport sector recorded a slight intensity of 0.36 MtCO2, highlighting the urgent need for low carbon mobility solutions. The waste sector achieved the most substantial GHG emissions abatement of 16.31 MtCO2, led by USA, despite intensified in four other nations. The findings emphasized the critical need for tailored, sector specific policy interventions, technology adoption, and behavioral changes to achieve sustained decarbonization. The study contributes to the global discourse on climate mitigation by offering comparative sectors specific insights to align national energy structures with global decarbonizing practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, natural variabilities of the Sun and volcanic eruption were accounted for change in Earth’s temperature, whereas in recent times, the anthropogenic activities are primarily causing climate variability1 through combustion of fossil fuels2 and creating pollution. The pollution like CO2, accumulates in the atmosphere, trapped the Sun’s heat on Earth and nurturing the temperature. Resultantly, the global warming instigating the climatic variabilities like declining biodiversity, water scarcity, droughts, intense storms, wild fires, melting polar ice, flooding, and others. The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere has been increased by 50% than in 1750 (the advent of Industrial Revolution), this transformation in concentration is exceeding the accumulation which took over the past 800,000 years3, more than 8.7 Million people are dying annually from outdoor air pollution4. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) from anthropogenic activities warmed the temperature about 1.1 °C since 1900 and caused to extreme weather events and are harming human health through pollution, forced displacement, food insecurity, mental health and others5,6.

In 2015, 196 countries adopted the Paris Agreement to strengthen the response to climate change and limit the global warming. At COP26 countries start revising Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), committing to limit warming to 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial level by 2030 and achieve net zero emissions by 2050. Achieving this goal requires a 45% reduction in global GHGs emissions from 2010 levels by 2030, necessitating urgent and transformative climate action. Currently devastating climate disruptions include, reducing ice sheet, rising sea level, intensifying extreme weather and melting glaciers, are causing widespread harms to human health, ecosystems, and economic stability5. The emissions level impact the social aspects as well by lessening emissions leads to increase happiness7 and with rising carbon emissions environment, social and governance performance declined rapidly8. In last two decades, 55 most climate vulnerable economies faced US$ 500 billion damages9, climate affected death toll passed 4 million in 2024. Extreme heat caused about 489,000 deaths annually during 2000-2019. In year 2022 alone, the disasters triggered a record 31.95 million displacements caused by floods, storms, wildfires, and droughts. Exceeding 1.5 °C could trigger multiple climate tipping points like breakdowns of ocean circulation systems etc., therefore every fraction of warming matters3.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme11, member states of the G20 economies are collectively responsible for emitting approximately 77% of global GHG emissions. A subset of Twenty-five mega cities including Shanghai, Beijing, Tokyo, Moscow and New York account for 52% of GHG emissions originating from urban areas. To align with the 1.5 °C global warming threshold established under Paris Agreement, global emissions must decline by 42% by 2030 and 57% by 2035, relative to 2019 levels11. Global GHG emissions from anthropogenic activities were approximately 61.8% higher in 2023 compared to 1990, reflecting an average annual increase of 1.5%, and reached around 52,962.90 Mt (CO2 equivalent). While most major emitting countries reduced their GHG emissions intensity per unit of GDP, with the exception of China where it remained broadly unchanged11.

Table 1 enlists the top ten GHG emitting countries in 2023, collectively responsible for approximately 65% of global emissions, by emitting 34,801 Mt (CO2 equivalent). In contrast, the 47 least developed countries emit only 3% global GHG emissions. At COP 29 in November 2024, delegates emphasized on worsening effects of global warming and highlighted the urgent financial and technological support required by developing nations to effectively address climate related challenges.

Emission Gap Report11 classified GHG emission in eight sectors; power industry, industrial combustion, buildings, transport, agriculture, fuel exploitation, processes and waste. Primarily, the sectors responsible to raise global GHG emissions are power sector 96%, Industrial combustion and processes 91%, transport 78%, waste 56%, fuel exploitation 48%. Therefore, exploring the sectoral GHG efficiency, sectoral intensities have significant impact to improve the environmental concerns and in restraining the global warming. One of the key feature of NDCs is to reduce the emissions’ intensity which is may be investigated through decoupling sectoral GHG emissions. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)12 define decoupling as alienating the bound between environmental pollution and economic development and according to UNEP13, “Decoupling at its simplest is reducing the amount of resources such as water or fossil fuels used to produce economic growth and delinking economic development from environmental deterioration”.

Substantial literature exists that accumulates global emissions for carbon dioxide14, methane15, and nitrous oxide emissions16, some studies have explored the sectoral trends of leading emission economies17, while Lamb et al.1 provided a regional comparison of five key sectors across ten global regions using data from 1990 to 2018. The present study contributes by employing an updated dataset (2000–2023) to analyze sectoral GHG emissions in the world’s leading ten emissions emitting nations. Leal et al.18 emphasized the relative roles of sectors in Australian GHG emissions to identify both underperforming and high emission sectors requiring strategic interventions to improve the sectoral efficiency and overall national emissions targets. This study investigates the decomposition of emissions across eight major sectors, ranked the countries by their 2023 GHG intensity indices, and explores the current sectoral emissions trends. Tenaw19 advocated for sectoral specific investigation for more effective climate policy insinuation. This study highlights the comparative sectoral decoupling status of the countries to achieve the sustainable development strategies and to avoid the dangerous impacts of climate change. This investigation will aid the formulation for sectoral emission reduction policies and timely accomplishing the carbon emission targets to save the world from climate change.

First part of this study presents the introduction section, second part elaborates the literature review, third part explains the recommended methodology, fourth part elucidates the results and presents discussion, fifth part consists of conclusion, policy recommendation and limitations and lastly, the references are provided.

Literature review

González et al.20 decomposed the GHG emissions in Spain during 2008–2018 at global and sectoral level. The study estimated 18.44% reduction in GHG emissions mainly because of intensity effect which remains more influential in agriculture and transport. while somewhat different patterns in sectors. The energy efficiency measures including, innovation, research and development, greener energies, environmental friendly technologies are essential to mitigate greenhouse effect. Liu et al.21 investigated the Chinese transport sector to decouple carbon emissions and growth for aiding emission reduction policy. During 2001–2018, annual average emission in transportation sector increased by 7.69% and emissions intensities from energy, transport and emission have increased by 16.67%, 5.32% and 2.22% respectively. This study suggested to optimize the energy structure with supportive clean technologies by reducing consumption of coal and crude oil to restrain the emissions.

Engo22 conducted a study on the Republic of Cameroon’s transport sector during the period 1990–2016 and found that the energy intensity effect hindered the decoupling of energy consumption from economic growth, whereas changes in the economic structure contributed to promote decoupling. The induction of Jet kerosene and aviation gasoline in energy supply is significantly reducing emissions in transport sector. It suggests to reduce the traditional motor gasoline and gas diesel oil through adjusting prices, taxes and phasing out emission intensive vehicles while promoting clean energy sources, modern technologies. Demographic factor and economic activities are the driving factors in transport sector and the government should raise public awareness to achieve the emission reduction targets.

Batoukhteh and Darzi-Naftchali23 explored the relationship between agricultural development and GHG emissions using economic, social and environmental aspects using 57 years’ data from 1961 to 2017. It indices showed the reduction of GHG emission by 79% for developed, 26% for developing and 5% for least developing countries. The study estimated about 65% developed countries effectively decoupling while unfavorable for others. Therefore, food security is at risk and adopting the environmental measures are essential. Adenauer et al.24 investigated the unilateral agriculture policies to reduce emissions in U.S which shows significant impact on trade. Li et al.25 analyzed mining and extractive related sectors by taking CO2 emissions from 1991 to 2014 for comparative analysis of energy efficiencies and energy intensities of China and Nigeria are enumerated. It suggested the circular economy have not emerged into CO2 emission reduction in both countries while the economic activities and energy use are the significant factor for reducing the emissions. Chontanawat et al.26 studied the industrial sector in Thailand from 2005 to 2017 using Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) method to decompose the sources of CO2 emission. The structural effect promoted emission reduction while the energy intensity raised the emission.

Lamb et al.1 investigated the GHG emissions of five sectors from ten region using dataset of 1990–2018. It suggests decarbonization of energy systems in North America and Europe from renewables and fuel switching while the emissions are expanding, in industrializing growing regions because of fossil fuels, in industry, buildings and transport sectors because of the growing demand in Eastern Asia, Southern and South East Asia and in agriculture sector because of carbon dense forest areas in Africa, Latin America, and South-East Asia. concluded the limited progress for reducing GHG emissions. Chen et al.27 found that Macao’s economic growth is becoming resilient from energy consumption. Xu et al.6 used Chinese sectoral carbon emission for comparative analysis and decoupling it from economic growth. It is recommended to implement stringent environmental policies targeting export oriented enterprises, along with sector specific allocation of emission reduction responsibilities, supported by a system of incentives and penalties. Construction sector is a key contributor of emission, Guo et al.28 investigated the conventional technique of building and off site prefabricating construction in China and concluded that utilizing prefabricated elements in concrete building structure can lead to a significant decrease in GHG emissions.

Azzeddine et al.29 explored the GHG emissions of Morocco during 1990–2018 to decouple climate change effects and cointegration results endorsed the long run relationship of emissions and GDP, however decoupling index exhibit relative smaller increase in GHG emissions than GDP. Kong et al.8 in green credit plays pivotal role in promoting environmental, social and governance performance by mitigating carbon emissions. Vélez-Henao and Pauliuk30 found the Colombian industrial and economic growth made building sector the largest energy and material consumers because of increased inhabitants and urbanization. Therefore, circular economy is an option to reduce resource depletion and climate change. Without circular economy building stocks will emit 13–25 Mt CO2/yr while the adoption will reduce 49% GHG emissions to achieve the net zero emissions by 2050. Raza and Lin31 illustrates the fossil fuel consumption raised the CO2 emissions intensity while the structural change reduced emission in industrial sector of Pakistan.

The literature endorsed the decoupling analysis which associates GHG emissions, economy and energy. Delinking emission from GDP induces green growth thus policies formulations to achieve the emission target directs to stimulate the efficiency. Tenaw19 decomposed the aggregate energy intensity in Ethopia during 1990–2017 and found that the efficiency component remained the significant role in reducing the energy intensity and suggested sectoral investigation for more effective policy formulation. Leal et al.18 suggested the adoption of energy efficiency measures according to the needs of each sector by enhancing renewable energy technologies. Grand32 suggested the suitability of decoupling for growing economies and supports the green de-growth for declining economies.

Methodology

Data

This investigation elaborates a comparative sectoral decoupling analysis of the ten largest global GHG emitting countries, utilizing the updated reliable data sources.

Method

Advancing sustainability encourages a comprehensive understanding of the structural and developmental dynamics of economies in relation to their associated GHG emissions. The literature endorsed the decoupling between economic growth and emissions on national, regional and industrial level35,36,37. The decoupling refers the separation of economic growth from the emission of GHGs. Index number decomposition provides reliable measures to estimate the intensity, efficiency and transformation levels38. Practically, the decoupling reveals the association between emissions and with economic growth to analyze the state of internal mechanism39,40,41.

A substantial body of literature has explored multiple decoupling approaches42,43,44,45,46,47,48 to effectively disseminate the important aspects, which can be broadly classified into two principal analytical frameworks: Index Decomposition Analysis (IDA) and Structural Decomposition Analysis (SDA). These approaches are commonly employed to disentangle the underlying drivers of decoupling, with intensity levels assessed in both relative and absolute terms, which are often conceptually interlinked. IDA is a widely recognized analytical technique employed to dissect complex changes in energy consumption, emissions, and environmental impacts. By decomposing aggregate variations into their constituent components, this approach provides detailed insights into the key factors influencing trends across these areas, making it a valuable instrument for environmental and energy studies20.

One of the key advantages lies in its ability to disaggregate changes in aggregate indicators, such as energy consumption or GHG emissions, without necessitating extensive datasets. This makes it particularly useful for policy analysis and cross country comparisons, especially in data constrained environments. Improving GHG emission efficiency is increasingly recognized as a cost effective and accessible pathway for advancing sustainable development objectives48. In this context, numerous empirical studies have employed IDA technique to investigate the driving forces behind variations in energy use and emissions across a range of national and regional contexts19,21. By integrating economic activity aspect, the IDA framework facilitates a more nuances understanding of decoupling trends between economic growth and environmental degradation.

Specifically, the decomposition of GHG emissions through IDA allows for the identification of key contributing factors, such as changes in energy intensity, emission factors, and economic structure. This analytical approach provides critical insights into the emissions dynamics and enabling policymakers to design more targeted mitigation strategies. Among various index decomposition techniques, the Fisher Ideal index is frequently utilized for its theoretical robustness and capacity to capture both proportional and structural changes in emissions intensity25,38,48. The application of this index enables the precise quantification of emission intensity changes, as demonstrated in the following formulation:

For efficiencies calculation

For activities calculations

Here “GIt” represents the GHG emissions intensity in given time period, “G” is used for GHG emissions, “Y” represents the output and the subscripts represents “o”, for base year, “1” for current year, “t” for time and “i” for individual economic sector. The efficiency index is more accurately measured using the Fisher Ideal Index and the LMDI method38, as these approaches address the limitations of traditional intensity indicators. They allow for a complete decomposition of GHG emissions into distinct components such as efficiency and activity effects without leaving unexplained residuals by enhancing the transparency and reliability.

“EFI” and “ACI” represent the efficiency index and activity index respectively, the Laspeyres and Paasche indices are used to enumerate “EFI” and “ACI”. The “\(\:GI\)” is formulated as the product of the “EFI” and “ACI”, as expressed below:

“\(\:\varDelta\:{GS}_{t}\)” represents the changes in GHG emissions relative to the base year (i.e.year 2000). The normalization process for base year is explained as:

Therefore, the value in the base year will be

The intensity of GHG emissions, enumerate the mean GHG emissions relevant to economic activities of an entity which is specified as the ratio of GHG emissions to output. The decomposition differentiates the changes in GHG emissions because of changes in economic activities. The index referred to GHG emissions efficiency and represents the GHG emissions to economic output.

Results and discussion

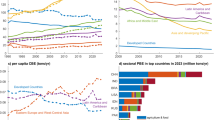

This investigation elaborates comparative sectoral decoupling analysis of world’s leading ten global GHG emitting countries, utilizing three decomposed indices over the period 2000–2023. Firstly, the countries are ranked based on the magnitude of their largest to smallest value of intensity indices in the year 2023, relative to the base year (i.e. year 2000). Secondly, to comprehend the pattern of decoupling and comparative analysis of these indices, average values from 2000 to 2023 are presented. Thirdly, annual average percentage changes are enumerated to assess temporal dynamics and fourthly, the average reductions in GHG emissions are estimated, providing insight into the effectiveness of mitigation efforts across these major emitting nations.

Results

Supplementary Table S1 presents the comparative analysis of the agriculture sector across the ten major GHG emitting countries, highlighting significant variations in the indices that reflect structural economic shifts, efficiency improvements, and changes in emission intensity. In 2023, nine countries excluding Saudi Arabia demonstrated a reduction in their intensity index compared to year 2000. China exhibited the most substantial decline in intensity, by 50.6%, despite environmental degradation resulting from increased economic activities. Concurrently, China’s efficiency index improved markedly by 83.7%.

In contrast, Saudi Arabia remains the only country where all three indices (efficiency, economic activities and intensity) show a worsening trend, indicating deterioration in sustainability efforts within its agriculture sector. Additionally, economic activities in India, Indonesia, Iran, and Russia have not aligned with GHG emissions mitigation, suggesting limited progress toward environmentally sustainable growth in these economies.

Japan stands out as the only country where structural economic transformation, rather than efficiency gains, is the primary driver of reduced emission intensity in agriculture. Among the average intensity improvements over the study period, Russia leads with a 31.8% reduction, followed by Iran (29.9%) and China (27%).

As a result, China achieved the highest average GHG emission abatement of 1.307 MtCO2, followed by Russia with 0.907 MtCO2 and Iran with 0.875 MtCO2. Importantly, all countries studied have shown, on average, net abatement in GHG emissions from the agriculture sector. This trend indicates a collective movement albeit at varying degrees toward enhanced sustainability and lower carbon intensity within global agricultural practices.

Resultantly, China (1.32 MtCO2) and India (0.76 MtCO2) experienced net increase in emissions, whereas Japan (1.08 MtCO2) and USA (0.736 MtCO2) achieved substantial GHG reductions through enhanced efficiency and economic restructuring.

Supplementary Table S3 depicts the decoupling trends in the power industry. In the year 2023, Canada (71.7%) and USA (70.2%) demonstrated significant improvements in their intensity indices, indicating enhanced decarbonization efforts. In contrast, China (136.1%), Indonesia (127.3%), India (57%) Saudi Arabia (32.8%) and Iran (26.1%) exhibited deteriorating intensity indices, reflecting increased carbon intensity. Regarding efficiency indices, Canada (67.9%), USA (60.4%) and Russia (47.7%) showed notable improvements, while Indonesia (45.5%), Iran (26.5%), Saudi Arabia (11.6%) and Brazil (1.6%) experienced declines. Over the years 2000–2023, worsening intensity trends were observed in China (78.7%), Indonesia (64.6%), Iran (29.5%), India (29.2), Saudi Arabia (25.3%) and Brazil (17.1%), whereas Canada (41.1%) and USA (37.5%) achieved long term improvements. Estimates further suggest that Canada (1.32 MtCO2) and USA (1.19 MtCO2) avoided GHG emissions, respectively, while China (1.37 MtCO2) and Indonesia (1 MtCO2) contributed to additional GHG emission, respectively.

Supplementary Table S4 presents the decomposition analysis of processes (category) of top ten global GHG emitting countries. Between 2000 and 2023, Saudi Arabia (84.2%), India (61.6%), Iran (61.4%) and China (58.9%) experienced a significant increase in their carbon intensity indices, indicating a deterioration in emission efficiency. Conversely, Japan (58.7%), Canada (52.9%) and USA (51.8%) showed decreased in carbon intensity relative to their baselines in year 2000. In term of efficiency index trends, Saudi Arabia (57.8%) and Iran (56.3%) exhibits notable declines, while diminishing GHG emissions were observed in China (47.5%), USA (41.3%), Canada (39.4%) and other nations. On average, from 2000 to 2023, intensity indices worsened by enhancing emissions in Saudi Arabia (74%), China (60.1%), Iran (52%) and India (31%), whereas the USA (36.4%), Japan (35.8%) and Canada (31.5%) achieved consistent progress in reducing GHG intensity. Notably, Saudi Arabia and Iran were the only countries to register long term declines in efficiency. With regard to GHG emission, USA (1.02 MtCO2) and Japan (1.01 MtCO2) reported annual abatement, whereas Saudi Arabia (1.156 MtCO2), China (1.148 MtCO2), Iran (0.856 MtCO2) and India (0.578 MtCO2) experienced net annual intensification in GHG emissions.

Supplementary Table S5 elaborates the decomposition analysis of the waste sector across the selected countries. During 2000 to 2023, the average intensity index increased in Japan (273%), Saudi Arabia (25.9%), China 11.5%) and in Iran (5.4%), indicating performance deterioration, while notable decline in intensity indices were observed in the USA (91.5%), Canada (31.4%) and others countries. Japan exhibited a particular sharp decline in efficiency, with abnormal drop of 379% in efficiency, followed by Saudi Arabia with a 13.2% reduction. In year 2023, the intensity index rose significantly in Japan (238%), Saudi Arabia (33.4%), China (21.4%) compared to 2000 levels, while the USA (95.3%), Canada (48.1%) and others showed continued reduction in intensity. Decomposition analysis further reveals substantial emission abatement in USA (19.924 MtCO2), Canada (0.825 MtCO2). In contrast, emission intensification was recorded in Japan (4.296 MtCO2), Saudi Arabia (0.472 MtCO2), China (0.317 MtCO2) and Iran (0,11 MtCO2), indicating increased GHG emissions from the waste sector.

Supplementary Table S2 elaborates the decomposition analysis of fuel exploitation sector of global top ten GHG emitting countries. In year 2023, Indonesia, China and India exhibited worsening trends, with their intensity indices increasing by 47.4%, 40.9% and 8.5% respectively, compared to year 2000. This contributed an average annual GHG emissions intensification of 0.22 MtCO2 for Indonesia and 0.745 MtCO2 for China over the 2000–2023 period. In contrast, Japan demonstrated the most substantial reduction of 72.6% in its intensity index and an average annual emission abatement of 1.038 MtCO2. Canada was the only country to record a deterioration in efficiency, with a 7.5% decline in 2023 relative to year 2000, resulting in an average annual intensification of 0.214 MtCO2. Over the 24 year (2000–2023) period, Canada also showed a 10.9% decrease in efficiency index, while China led with an increased efficiency of 31.4%. Despite Canada’s improved economic activity leading to a 0.7% reduction in intensity, while China led to enhance the intensity index by 33.4%. Overall, China and Indonesia are identified as the major contributors to GHG emissions increase, while Japan and USA demonstrate leadership in improving fuel exploitation efficiency and reducing emissions.

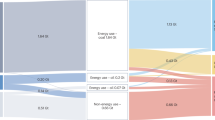

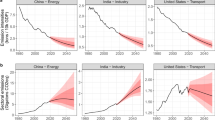

Figure 1 illustrates, for each sector, the countries that achieved reductions in average GHG emissions over the period 2000–2023 relative to their baseline year 2000. Figure 2 depicts sector specific GHG emissions intensities, normalized to their respective levels in year 2000. These Figures facilitate a comparative rankings of countries sectoral emission abatement performance. The extent of abatement varies substantially across countries, likely reflecting a constellation of underlying determinants which are beyond the scope of this study.

Discussion

The decoupling of agriculture sector reveals that all the ten highest GHG emitting countries improved their efficiency indices from 2000 to 2023. These gains contributed to notable emissions reductions, supporting the earlier findings49. China and Russian achieved the most significant abatement of GHG emissions, whereas Brazil and Saudi Arabia recorded the smallest reductions. Brazil and Saudi Arabia ranked highest in terms of intensity index performance, while Russia and Iran rank lowest. These variations reflect differing national strategies and align with the observations reported by Yasmeen et al.50, emphasizing the uneven progress for decarbonization of agriculture sector.

In building sector, both the efficiency and intensity indices showed a declining GHG emission pattern across all the countries in year 2023. Indonesia and Japan emerged as leaders in GHG emissions reduction, while Iran and China recorded the least progress. On average, Indonesia and Japan demonstrated the most significant reduction in intensity indices, whereas China and Iran lagged behind. The energy intensity continues to negatively impact environmental quality, particularly in China28 and USA51. Erdogan52 reported that technological innovation plays an important role in reducing emissions in building sector of BRICS nations, recommending increased investment in research and development. Ghasemi et al.53 advocated for policy interventions such as enhanced data accessibility, public education, lifecycle based thinking, green certifications and the promotion of sustainable business practices to achieve carbon neutrality. Guo et al.28 highlighted that the use of prefabricated concrete structure elements can significantly contribute to GHG emissions reductions in construction.

In the fuel exploitation sector, intensity indices increased in Indonesia and China, whereas Japan and Brazil achieved reductions. Canada was the only country where efficiency declined, while China and India showed an increase in efficiency. In terms of GHG emissions, Japan, USA and Brazil achieved emission abatement, whereas China and Indonesia experienced increases. Galimova et al.54 examined the role of e-fuels and e-chemicals in global energy system, highlighting their potential benefits. Renewable energy resources contribute to diversification, reduce trade costs and lower the risk of supply disruptions. In the power sector, emission reductions were observed in USA, Canada, Russia and Japan, while the emission increased in the remaining countries. Intensity trends were favorable for Canada, USA and Russia, but deteriorated in other nations. Efficiency indices increased in Russia, Canada, USA and India, leading to reduce GHG emissions while other countries recorded a decline causing a rise in emissions. Overall, four countries (Canada, USA, Russia and Japan) demonstrated significant GHG emission abatement in the fuel exploitation sector. Electrification, low carbon fuels and reduction of emissions are the primary significant factors to support de-carbonization efforts55.

In the industrial combustion sector, intensity levels worsened in China, India, Iran, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia, while the USA and Canada exhibited positive progress. Efficiency declined in Iran and Saudi Arabia, but improved in USA and Canada. In terms of GHG emissions, USA, Canada and Japan achieved notable abatement, whereas China, India, Iran, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia recorded increased emissions. Within the processes industry, intensity indices deteriorated in Saudi Arabia, China, Iran and India, while other countries demonstrated a decline in the index. Efficiency also declined in Saudi Arabia and Iran but improved across the remaining nations. USA and Japan emerged as the most effective countries in reducing GHG emissions, while Saudi Arabia and China were the highest contributors to emission increase. These trends highlight significant disparities in industrial performance and suggest targeted policy interventions in high emission countries.

In the transport sector, average intensity levels increased in China, India, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Iran, whereas declines were observed in Japan, USA, Canada and Russia. These findings align with Liu et al.21, which reported a significant rise in carbon emissions in China’s transportation industry. Efficiency improved in Japan and Russia but deteriorated in Saudi Arabia and Iran. Consequently, China, India and Saudi Arabia were the primary contributors to increase GHG emissions, while notable emission abatements were recorded in Japan, USA and Canada. Kilinc-Ata and Fikru56 emphasized the critical transitional role of electric vehicles in decarbonizing the transport sector, advocating for mineral specific policies to drive technological innovation and reduce transaction costs. Solaymani and Botero57 recommended addressing both supply and demand side measures separately and found the most significant emissions reductions occurred when both strategies were implemented simultaneously. Additionally, their findings suggest that government support for renewable energy development has more substantial impact on environmental sustainability that fuel price increase alone, therefore underscoring the importance of integrated policy approaches.

In the waste industry, intensity levels (compare to baseline year 2000) worsened in Japan, Saudi Arabia and China, while in USA, Canada and Brazil the GHG emissions declined due to improved intensity indices. The efficiency increased in USA, China and India but declined in Japan and Saudi Arabia. USA led in GHG emission reductions, followed by Canada, whereas Japan recorded the highest emission intensity, followed by Saudi Arabia. Evode et al.58 investigated the use of plastics in production sectors through biochemical processes, highlighting that improper post use disposal of plastic waste poses serious environmental risks. To mitigate climate impacts, the study emphasized the importance of managing the full life cycle of plastic products based on their categories. Oyejobi et al.59 examined the integration of circular economy principles into concrete technology, to assessing the potential of industrial waste materials as supplementary cementitious components. Their findings support the transformation of the construction and transport sectors through sustainable material reuse and waste valorization.

Major emission emitting economies remain strongly dependent on fossil fuels as economic growth, urban expansion and industrialization continue to drive energy demand. Coal dominant power generation, oil based transport systems, industrial fuel combustion and residential energy use are key contributors to rising emissions61. In response, national energy strategies are increasingly shifting toward renewable energy deployment, supported by digital transformation of the energy sector and policy driven investment reforms aimed at improving affordability and sustainability62. Forward looking energy mixes emphasize sectoral transitions, particularly in transport, where electrification, improved fuel quality and expanded public transportation may deliver substantial emission reductions63. Despite these advances, decarbonization progress remains uneven across countries and sectors. Addressing these challenges requires enhanced data transparency, life cycle based assessment, circular economy integration and standardized sustainability reporting frameworks to enable effective policy interventions and long term carbon neutrality64.

Conclusion

This study provides a rigorous assessment of how economic activity and emissions have evolved across the global ten highest GHG emitting countries by disentangling sectoral behavior from 2000 to 2023 through Index Decomposition Analysis. The quantitative evidence clearly demonstrates that decabonization progress is uneven, sector dependent and shaped by national capabilities and policy orientations rather than by broad uniform trends. The results reveal decisive structural decoupling in several sectors. Agriculture achieved an average abatement of 6.44 MtCO2, attributable to measureable improvement in productivity, enhanced crop residue management and improved energy utilization. Similarly, the building sector reduced emissions by 6.34 MtCO2, reflecting the causal influence of energy efficient construction, improved insulation and smart building technologies. The most substantial mitigation occurred in the waste sector. Where emissions declined by 16.31 MtCO2, led predominantly by the United States with a reduction of 19.92 MtCO2, demonstrating the effectiveness of landfill gas recovery and modernized waste processing systems. In contrast, several high impact sectors exhibited insufficient or reversed progress. Transport emissions intensified by 0.36 MtCO2, driven largely by increases of 3.03 MtCO2, in China, India, Iran, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia. This intensification correlates with rising vehicle ownership, fossil fuel dominance in mobility, and slow uptake of electrified transportation. The fuel exploitation sector achieved limited average abatement (2.24 MtCO2), yet China and Indonesia alone added 0.97 MtCO2, underscoring persistent reliance on carbon intensive extraction methods. Industrial combustion displayed similarly mixed outcomes, with modest reduction (0.74 MtCO2) overshadowed by combined intensification of 3.35 MtCO2 in five emerging economies, revealing entrenched dependence on traditional industrial energy systems. The power generation and industrial process sectors shoed virtually no change, signaling deep structural inertia that current policy measures have not adequately addressed. These quantitative patterns affirm that effective decarbonization requires sector tailored strategies grounded in empirical realities. The pronounced gains in agriculture, buildings, and waste demonstrate that targeted interventions supported by coherent policy framework can generate measurable climate benefits. Meanwhile, the persistent intensification in transport, industrial combustion, and fuel exploitation highlights the need for rapid electrification, adoption of low carbon fuels, and modernization of industrial technologies.

This study acknowledges methodological and data related constraints, including the absence of indirect emissions, the exclusion of welfare or policy effect analysis and limited sectoral value added data. Future work would benefit from scenario based modeling, dynamic country selection aligned with shifting global emission rankings, and incorporation of demographic and research and development variables to refine causal inference. Despite these limitations, the findings offer a robust quantitatively grounded framework for policymakers seeking to align national energy systems with global decarbonization pathways and accelerate the transition toward a resilient low carbon world.

Data availability

The data can be achieved from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Lamb, W. F. et al. A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 (7), 073005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abee4e (2021).

Intergovernmental Panel on climate change. working group 1 technical support unit, version 3, 12 December 2022. IPCC, (2022a). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SummaryForAll.pdf

IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2391 pp. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.

Vohra, K. et al. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: results from GEOS-Chem. Environ. Res. 195, 110754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110754 (2021).

IPCC. : Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., (2022b). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Xu, W., Xie, Y., Xia, D., Ji, L. & Huang, G. A multi-sectoral decomposition and decoupling analysis of carbon emissions in Guangdong province, China. J. Environ. Manage. 298, 113485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113485 (2021).

Kilinc-Ata, N., Kaya, E. & Barut, A. Exploring the influence of Democracy, rule of Law, and societal Well-being on climate action in OECD nations. J. Knowl. Econ. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02452-4 (2024).

Kong, X., Li, Z. & Lei, X. Research on the impact of ESG performance on carbon emissions from the perspective of green credit. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 10478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61353-3 (2024).

United Nations Environment Programme. Adaptation Gap Report 2023: Underfinanced. Underprepared. Inadequate investment and planning on climate adaptation leaves world exposed. Nairobi. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43796. URL: UNEP, (2023). https://www.unep.org/adaptation-gap-report-2023

World Meteorological Organization. State of Climate Services Health, WMO-No. 1335. Geneva 2023. URL: WMO, (2023). https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/68500

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 2024). Emissions Gap Report 2024: No more hot air … please! With a massive gap between rhetoric and reality, countries draft new climate commitments. Nairobi. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/46404.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Indicators, Towards green growth: monitoring progress. OECD, (2011). https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2011/05/towards-green-growth-monitoring-progress_g1g1342e/9789264111356-en.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

United Nations Environment Programme. Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth. A report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel (eds Fischer-Kowalski, Y. et al.) (UNEP, 2011).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 11(4), 1783–1838. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019 (2019).

Saunois, M. et al. Global methane budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 17(5),1873–1958. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-1873-2025 (2025).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature, 586(7828), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2780-0 (2020).

Magazzino, C., Pakrooh, P. & Abedin, M. Z. A decomposition and decoupling analysis for carbon dioxide emissions: evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26 (11), 28539–28566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03824-7 (2024).

Leal, P. A., Marques, A. C. & Fuinhas, J. A. Decoupling economic growth from GHG emissions: decomposition analysis by sectoral factors for Australia. Economic Anal. Policy. 62, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2018.11.003 (2019).

Tenaw, D. Decomposition and macroeconomic drivers of energy intensity: the case of Ethiopia. Energy Strategy Reviews. 35, 100641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100641 (2021).

González, P. F., Presno, M. J. & Landajo, M. Tracking the change in Spanish greenhouse gas emissions through an LMDI decomposition model: A global and sectoral approach. J. Environ. Sci. 139, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2022.08.027 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Influencing factors of carbon emissions in transportation industry based on CD function and LMDI decomposition model: China as an example. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 90, 106623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106623 (2021).

Engo, J. Decoupling analysis of CO2 emissions from transport sector in Cameroon. Sustainable Cities Soc. 51, 101732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101732 (2019).

Batoukhteh, F. & Darzi-Naftchali, A. A global study on decoupling greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26 (5), 13159–13183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04137-5 (2024).

Adenauer, M. et al. Impacts of unilateral US carbon policies on agricultural sector greenhouse gas emissions and commodity markets. Environ. Res. Lett. 20(2), 024022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ada2ac (2025).

Li, G., Zakari, A. & Tawiah, V. Energy resource melioration and CO2 emissions in China and nigeria: efficiency and trade perspectives. Resour. Policy. 68, 101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101769 (2020).

Chontanawat, J., Wiboonchutikula, P. & Buddhivanich, A. An LMDI decomposition analysis of carbon emissions in the Thai manufacturing sector. Energy Rep. 6, 705–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2019.09.053 (2020).

Chen, B., Yang, Q., Li, J. S. & Chen, G. Q. Decoupling analysis on energy consumption, embodied GHG emissions and economic growth—The case study of Macao. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 662–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.027 (2017).

Guo, Y., Shi, E., Yan, R. & Wei, W. System based greenhouse emission analysis of off-site prefabrication: A comparative study of residential projects. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 10689. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37782-x (2023).

Azzeddine, B. B., Hossaini, F. & Savard, L. Greenhouse gas emissions and economic growth in morocco: A decoupling analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 450, 141857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141857 (2024).

Vélez-Henao, J. A. & Pauliuk, S. Pathways to a net zero Building sector in colombia: insights from a circular economy perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 212, 107971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107971 (2025).

Raza, M. Y. & Lin, B. The impact of the productive sectors on CO2 emissions in Pakistan. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 110, 107643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107643 (2025).

Grand, M. C. Carbon emission targets and decoupling indicators. Ecol. Ind. 67, 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.03.042 (2016).

Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. Community GHG Database (a collaboration between the European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), the International Energy Agency (IEA), and comprising IEA-EDGAR CO2, EDGAR CH4, EDGAR N2O, EDGAR F-GASES version EDGAR_2024_GHG (2024), European Commission. EDGAR, (2024). https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/report_2024, https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset_ghg2024.

Crippa, M. et al. F., GHG Emissions of all World countries – JRC/IEA 2024 Report JRC138862 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2024). https://doi.org/10.2760/4002897https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC138862

Cappers, P. A., Satchwell, A. J., Dupuy, M. & Linvill, C. The distribution of US electric utility revenue decoupling rate impacts from 2005 to 2017. Electricity J. 33 (10), 106858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2020.106858 (2020).

Wang, X., Wei, Y. & Shao, Q. Decomposing the decoupling of CO2 emissions and economic growth in China’s iron and steel industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 152 (June 2019), 104509. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104509

Wang, Q., Jiang, R. & Li, R. Decoupling analysis of economic growth from water use in city: a case study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou of China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 41 (May), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.010 (2018).

Liu, N. & Ang, B. W. Factors shaping aggregate energy intensity trend for industry: energy intensity versus product mix. Energy Econ. 29 (4), 609–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2006.12.004 (2007).

Huo, T. et al. Decoupling and decomposition analysis of residential Building carbon emissions from residential income: evidence from the provincial level in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 86 (May 2020)), 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106487 (2021).

Chen, X., Shuai, C., Zhang, Y. & Wu, Y. Decomposition of energy consumption and its decoupling with economic growth in the global agricultural industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 81 (December 2019)). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2019.106364 (2020).

Chen, J., Wang, P., Cui, L., Huang, S. & Song, M. Decomposition and decoupling analysis of CO2 emissions in OECD. Appl. Energy. 231, 937–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.09.179 (2018).

Ghodratnama, M., Razmi, S. M. J., Sadati, S. S. M. & Razmi, S. F. Investigating the effects of energy price index on technical environmental efficiency in Iran. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19 (3), 2119–2128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03348-5 (2022).

Chen, J. & Zhu, X. The effects of different types of oil price shocks on industrial PPI: evidence from 36 sub-industries in China. Emerg. Markets Finance Trade. 57 (12), 3411–3434. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1694897 (2021).

Akyürek, Z. LMDI decomposition analysis of energy consumption of Turkish manufacturing industry: 2005–2014. Energ. Effi. 13 (4), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-020-09846-8 (2020).

Bianco, V. Analysis of electricity consumption in the tourism sector. A decomposition approach. J. Clean. Prod. 248, 119286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119286 (2020).

Dong, K., Hochman, G. & Timilsina, G. R. Do drivers of CO2 emission growth alter overtime and by the stage of economic development? Energy Policy. 140, 111420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111420 (2020).

Hu, B., Li, Z. & Zhang, L. Long-run dynamics of sulphur dioxide emissions, economic growth, and energy efficiency in China. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.170 (2019).

Tajudeen, I. A., Wossink, A. & Banerjee, P. How significant is energy efficiency to mitigate CO2 emissions? Evidence from OECD countries. Energy Econ. 72, 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.04.010 (2018).

Strokov, A. S. Greenhouse gas emissions in crop production. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 91 (2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1019331621020088 (2021).

Yasmeen, R., Tao, R., Shah, W. U. H., Padda, I. U. H. & Tang, C. The nexuses between carbon emissions, agriculture production efficiency, research and development, and government effectiveness: evidence from major agriculture-producing countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (34), 52133–52146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19431-4 (2022).

Kilinc-Ata, N., Camkaya, S., Akca, M. & Topal, S. The impact of uncertainty in economic policy on the load capacity factors in China and the united States (US): new evidence from novel fourier bootstrap ARDL approach. J. Sustain. Res. 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20250002 (2025).

Erdogan, S. Dynamic nexus between technological innovation and Building sector carbon emissions in the BRICS countries. J. Environ. Manage. 293, 112780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112780 (2021).

Ghasemi, E., Azari, R. & Zahed, M. Carbon neutrality in the Building sector of the global south—a review of barriers and transformations. Buildings 14 (2), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020321 (2024).

Galimova, T. et al. Global trading of renewable electricity-based fuels and chemicals to enhance the energy transition across all sectors towards sustainability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 183, 113420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113420 (2023).

Kar, S. et al. A deep decarbonization framework for the United States economy–a sector, sub-sector,and end-use based approach. Sustain. Energy Fuels 8(5), 1024–1039. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3SE00807J (2024).

Kilinc-Ata, N. & Fikru, M. G. A framework for evaluating EV battery mineral sourcing challenges. Sustainable Futures. 100720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2025.100720 (2025).

Solaymani, S. & Botero, J. Reducing carbon emissions from transport sector: experience and policy design considerations. Sustainability 17 (9), 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093762 (2025).

Evode, N., Qamar, S. A., Bilal, M., Barceló, D. & Iqbal, H. M. Plastic waste and its management strategies for environmental sustainability. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 4, 100142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100142 (2021).

Oyejobi, D. O., Firoozi, A. A., Fernandez, D. B. & Avudaiappan, S. Integrating circular economy principles into concrete technology: enhancing sustainability through industrial waste utilization. Results Eng. 102846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102846 (2024).

World Bank. World development indicators. (2025). https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators).

Roy, S., Lam, Y. F., Chopra, S. S. & Hoque, M. M. Review of decadal changes in ASEAN emissions based on regional and global emission inventory datasets. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 23 (1), 220103. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.220103 (2023).

Elavarasan, R. M. et al. Envisioning the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)through the lens of energy sustainability (SDG 7) in the post-COVID-19 world. Appl. Energy 292, 116665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116665 (2021).

Roy, S., Lam, Y. F., Hung, N. T. & Chan, J. C. Development of on-road emission inventory and evaluation of policy intervention on future emission reduction toward sustainability in Vietnam. Sustain. Dev. 29 (6), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2203 (2021).

Chopra, S. S. et al. Navigating the challenges of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting: the path to broader sustainable development. Sustainability 16 (2), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020606 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R346), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgements: The authors are deeply thankful to the editor and reviewers for their valuable suggestions to improve the quality and presentation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S.A, A.A.J and M.A wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest regarding the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alamri, F.S., Janjua, A.A. & Aslam, M. Exploring sectoral energy structures for decarbonization: an analysis of leading global emitting countries. Sci Rep 16, 7365 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39298-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-39298-6