Abstract

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aims to strengthen regional economic and policy cooperation and achieve the rapid development among the participating countries. While the impact on the financial development of the economic growth and energy environment of BRI participating countries has garnered close attention among scholars, few studies focus on the impact of financial development on the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the BRI participating countries. To address this gap, we utilized panel regression models to quantitatively assess the impact of China’s financial development scale, structure, and efficiency on the SDGs of the BRI participating countries, and adopted Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) model to explore the spatial-temporal effects of China’s financial development scale, structure, and efficiency on the SDGs of the BRI participating countries. Our findings indicate that China’s financial development has significantly promoted the SDGs of the BRI participating countries. This study further reveals that the scale and efficiency of China’s financial development have had a more pronounced impact on the SDGs of Asian countries, low- and middle-income countries, and the Land Silk Road participating countries, compared to those of European countries, high-income countries, and the Maritime Silk Road participating countries, respectively. In contrast, the structure of financial development primarily promotes the SDGs of European and high-income BRI participating countries in the land silk belt. The role of China’s financial development in promoting the SDGs of most BRI participating countries has gradually increased over time. This study provides valuable insights for decision-makers in China to facilitate the sustainable development of BRI participating countries and foster a shared community within the BRI framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

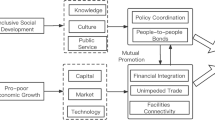

In response to the impact of the financial crisis on the global economy and to enhance regional economic and policy cooperation, China introduced two major initiatives in 2013: the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” collectively referred to as “the Belt and Road” (Shi et al., 2018; Rauf et al., 2020; Anwar et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2020; Huang, 2016; Li, 2020). In 2015, China released the “the Belt and Road” construction vision and action document, outlining specific measures of the “the Belt and Road” policy (Duan et al., 2018). The core principles of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), including the “three cooperation principles” (co-consultation, co-construction and sharing), the “five cooperation priorities” (namely, “five connections”: policy communication, facility connection, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people to people connection) and the goal of “building a community with a shared future for mankind,” align closely with the five core factors of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—“human,” “earth,” “prosperity,” “peace,” and “cooperation.” The 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) complement each other, becoming an important international cooperation mechanism for promoting sustainable development in developing countries. One of the main reasons for the timely implementation of the SDGs in the BRI participating countries is the lack of sufficient development funding (UNFCCC SCF, 2018; UN, 2020). As a novel regional cooperation project, the BRI promotes the free flow of production factors, enhance resource allocation efficiency, dismantles trade barriers between countries, and presents a grand vision for China’s economic integration with Asia, Europe, and Africa. It plays an important role in addressing global challenges and realizing the United Nations 2030 SDGs (Du and Zhang, 2018).

Financial development involves the continuous improvement of financial efficiency, the expansion of the scale of financial transactions and the upgrading of the financial industry, reflecting the innovation of financial instruments and the diversification of financial institutions to adapt to economic development (Atta et al., 2020; Dogan and Seker, 2016; Farhani and Ozturk, 2015). Financial development provides funding for economic development, natural resource extraction, research and development in new energy, infrastructure construction, improvements in the ecological environment, and advancements in social governance. For example, financial development can enhance energy efficiency by pooling and mobilizing savings, promoting investment, encouraging and facilitating information on foreign direct investment, optimizing capital allocation, and encouraging economic growth through technological progress and capital accumulation (Yu and Chen, 2011; Sadorsky, 2010). Therefore, both quantitative (scale) and qualitative (efficiency and structure) aspects of financial development are crucial. In the process of BRI implementation, financial development, as an important guarantee, promotes financial reform, financial market stability and the attractiveness of foreign direct investment in the BRI participating countries, which is conducive to the realization of SDGs. Financial development is of great significance to the realization of SDGs in the BRI participating countries. At present, most of the BRI participating countries are emerging and developing countries with economic development characterized by high input, high energy consumption and pollution. With the increasing prominence of global resources and environmental issues, some countries and international organizations have deeply realized the importance of green development and the role of capital investment in promoting green development (Ding et al., 2021). Financial development can play a vital role in promoting economic development and support the implementation of the BRI. Considering the long-term demand in capital investment and projects, financial development can facilitate funding for the BRI implementation, alleviate the problems of capital investment, energy consumption and carbon emissions, ensure the sustainability of construction investment and financing, and promote the SDG progress of the BRI participating countries (Li et al., 2022; Mills et al., 2021). Simultaneously, the BRI participating countries are establishing a new financial cooperation mechanism to promote financial development and reform, using the BRI as a conduit (Malik et al., 2021).

Currently, research conducted by relevant scholars on the impact of financial development on the sustainable development of the BRI participating countries primarily concentrates on a single dimension of financial development. It lacks a multi-dimensional perspective and detailed heterogeneity analysis (Muhammad et al., 2022). Firstly, many scholars study the impact of financial development from a single dimension such as financial depth, financial stability, and financial institutional environment (Pata et al., 2022; Hasni et al., 2023; Elkhuizen et al., 2018). Given China’s continuous economic development and financial system enhancement, it is not only necessary to pay attention to the credit scale of financial institutions, but also to the structure and efficiency of financial development (Yang and Ni, 2021; Nian and Dong, 2022; Yang et al., 2023). However, few studies have quantitatively evaluated multiple aspects of financial development at the same time, and failed to comprehensively demonstrate the role of financial development in promoting the realization of the Belt and Road. Secondly, few scholars have studied the impact of financial development on SDGs from the perspective of SDGs (Udemba et al., 2021). Moreover, previous research has mainly focused on the impact on a single aspect of sustainable development, such as CO2 emissions, deforestation, or health (Liu, 2014; Atkinson et al., 2012; Pendrill et al., 2019; Harris and White, 2019). Finally, there is relatively little research on the heterogeneity of the impact of financial development on SDGs. Most scholars associate the impact of financial development on SDGs with carbon emissions for analysis, while some scholars suggest that financial development has a promoting effect on a particular aspect of the economy, society, or environment in the SDGs (Zioło et al., 2023; Abid et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2023).

To address the research gap mentioned above, we quantitatively assess the impacts of China’s financial development on the SDGs, and utilize the Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) model to explore the temporal-spatial effects of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the BRI participating countries.

This study addresses the following research questions: (1) Has China’s financial development promoted the SDGs of BRI participating countries? (2) How does China’s financial development affect the BRI participating countries of different types of BRI participating countries? (3) How do these influences change over time? To answer those questions, we first aggregated the panel data on 61 BRI participating countries over the period 2005–2018, used the panel data model to assess the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries. Next, we compared the different impacts of China’s financial development on the SDGs of Asian countries and European countries, the different influences of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the Maritime Silk Road Economic Belt and the Land Silk Road Economic Belt, and the different impacts of China’s financial development on the SDGs of countries with different income levels. Lastly, using the GTWR model, we discuss the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the impact of China’s financial development scale, structure and efficiency on the SDGs of BRI participating countries.

The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) This study measures China’s financial development from three dimensions: the scale of financial development, structure, and efficiency, and we explore the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries from three dimensions of financial development. (2) We analyze the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of different types of the BRI participating countries, providing references for the development of SDGs tailored to the diverse range of the BRI participating countries. (3) We describe the spatio-temporal heterogeneity of the impact of China’s financial development scale, structure, and efficiency on the SDGs of BRI participating countries, and help the BRI participating countries promote sustainable development from a spatio-temporal perspective.

The remaining parts of the paper is arranged as follows: “Methods” describes the model and data, including variable selection, model construction, and data explanation. “Results” presents the empirical results. “Discussion” includes the discussion, which makes an in-depth analysis of the empirical results combined with relevant theories and puts forward the corresponding research enlightenment. “Conclusions” summarizes this research as the conclusion.

Methods

Data

The data used in this paper is sourced from the World Bank database, which integrates comprehensive data from organizations such as The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and other databases. The statistical scope covers 20 categories including urban construction, agricultural ecology, economic growth, gender equality, and social development. The BRI participating countries have been subject to constant changes, and different researchers may have slightly different definitions of the participating countries (Huang, 2019; Tian et al., 2019). Following the BRI literature (Tian et al., 2019), we selected 65 countries as the BRI participating countries and categorized the other countries as non-BRI-participating countries. Considering the availability of control variables and the integrity of the sample, we selected 61 of these countries. The missing sample data of individual years are supplemented by fitting interpolation method. The research samples in geographical distribution selected in this paper cover all BRI participating countries, and include developing and developed countries. It can be considered that the selected samples have certain degree of representativeness.

According to geographical space, 61 countries BRI participating countries are divided into two economic belts: the Maritime Silk Road and the Land Silk Road. The Maritime Silk Road participating countries include 33 countries across Southeast Asia, West Asia and South Asia. The Land Silk Road participating countries come from 28 countries including East Asia, Central Asia, CIS, and Central and Eastern Europe (Table 1).

Variable selection

Explained variables: SDGs

The United Nations SDGs call on all countries to take action to protect the planet while promoting economic prosperity. It is emphasized that poverty eradication must go hand in hand with a series of strategies, including promoting economic growth, enhancing social capital (e.g., education, health, welfare, employment opportunities), curbing climate warming, and protecting the environment.

Our study primarily focuses on SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), 5 (Gender Equality), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), and 15 (Life on Land) since they nicely align with the impact of the BRI on the SDGs. Some SDGs are not suitable for evaluation from a national perspective, such as SDG14 (Life below water), as many countries do not have their own maritime areas, and SDG17 (Partnerships for the goals), which focuses on global partnerships for sustainable development. On the other hand, data availability also limits our assessment of more SDGs. Lastly, economic growth (SDG8) is an important aspect of socioeconomic development and progress, while technological innovation (SDG9) provides the driving force for sustained economic growth. The importance of these goals for national development is beyond doubt, which is why they were chosen. Most of the BRI participating countries are developing countries, and SDG2 (Zero Hunger), SDG3 (Health and well-being) and SDG5 (Gender equality) are important challenges and development needs for these countries (Liu et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2023). By studying these indicators, we can effectively evaluate the role of China’s financial development in promoting the sustainable development of the BRI participating countries. In summary, our research focuses on SDGs 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 15. The remaining SDGs lie beyond this study’s scope due to geographical scale (global) or data availability. We employ the entropy method to calculate the score of SDGs.

Explanatory variables

We measure China’s financial development from three dimensions: scale, structure, and efficiency.

Financial development scale (FIR)

The scale of financial development refers to the level of development and the size of the financial market in a country or region during a specific period. It is primarily influenced by economic development factors, economic structure factors, political factors, social environment factors, and capital investment. We use the ratio of the total balance of RMB deposits and loans of financial institutions to GDP to measure it (Wang and Sun, 2003).

Financial development structure (FS)

For the selection of financial development structure indicators, Zhou and Lu (2019) adopted the stock market value, the balance of bank loans, the ratio of venture capital to GDP. Ying and Ning (2022) replaced the whole capital market with the stock market and measured the financial structure with the ratio of the stock market value to the bank credit. We adopt the second method since the bond market is inseparable from financial institutions such as banks but the venture capital market is relatively small and lacks comparable statistics.

Financial development efficiency (FE)

Financial development efficiency reflects the conversion efficiency from savings to investment in indirect financing channels and emphasizes the financial supply efficiency of financial intermediaries. To a certain extent, the loan-to-deposit ratio reflects the conversion efficiency from savings to investment in indirect financing channels, emphasizing the financial supply efficiency of financial intermediaries. This indicator is mainly adopted because indirect financing is dominant in China, and a mature financial system will not only attract idle funds in the economy, but also attract funds from outside the economy to provide financial support for the economic development (Zhuang et al., 2020). The higher the ratio, the greater the efficiency of the financial system in converting savings into investment.

Substitution metrics for explanatory variables

In order to further test the conclusions, we referred to the literature (Lv et al., 2021; Jiakui et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2021), and selected different indicators to measure the scale, structure and efficiency of financial development, and validated the robustness of the research conclusion. The specific expressions of the selected indicators are as follows:

Considering the ratio may be influenced by various factors, which may not fully reflect the impact of financial development on SDGs, we further replaced explanatory variables and used an absolute amount to measure China’s financial development. Finance refers to the circulation of monetary funds, and financial development achieves effective allocation of resources through fund circulation. The size of fund circulation is the most important criterion for judging the financial development of a country or region. Therefore, we selected the social financing scale in China as the proxy variable for financial development, denoted as SFS. The SFS can reflect the size of fund circulation, and is widely used in measuring financial development. The calculation of SFS is simple and its data is easy to obtain. The use of SFS as a proxy variable for China’s financial development will not be affected by other factors, and can fully reflect the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the participating countries.

Control variables

Considering the many factors that could potentially affect sustainable development, it is necessary to add control variables to the test model to express the influence of these important factors. We referred to Managi et al. (2021), Tienhaara (2009), Zafar et al. (2020), Aust et al. (2020), and Novo-Corti et al. (2018) and the selected include the population growth (PGR), the technology level (TECH), foreign trade (FT) and the education development level (EDU) and the human capital (RD). The variables and their connotation are shown in Table 2.

Models

Panel data model

Using the methods of Zafar et al. (2020) and Aust et al. (2020), we adopt the panel data model to explore the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries.

where \({\rm{SDG}}_{it}\) is the explained variable, which indicates the score of the SDGs of the BRI participating country i in the period t (that is the degree of achievement of the goal). \({\rm{FIR}}_{it}\), \({\rm{FS}}_{it}\) and \({\rm{FE}}_{it}\) represent the scale, structure, and efficiency of China’s financial development respectively. \({\rm{EDU}}_{it}\) represents the degree of educational development. \({\rm{RD}}_{it}\) represents human capital. \({\rm{PGR}}_{it}\) represents population growth. \({\rm{FT}}_{it}\) represents foreign trade. \({\rm{TECH}}_{it}\) represents the level of science and technology. \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is a random item.

Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression model (GTWR)

We have reviewed some relevant literature, such as the researches of Chen et al. (2023), Huang (2021), and Zeng et al. (2019), which are similar to our study. They adopted the GTWR model to discuss the spatial-temporal evolution of transportation on human footprint, spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the impact of high-speed railway on urban economy, local variations in regional technological evolution in China. Therefore, we referred their studies and employ the GTWR model to explore the spatial-temporal evolution of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the Belt and Road Initiative Participating Countries.

GTWR model uses both the spatial and temporal information of variables to generate an optimal estimate by controlling for spatial non-stationary characteristics of the relationship between variables. This approach can resolve the heterogeneity analysis dilemma of Geographically Weighted Regression model (Huang et al., 2010). We constructed the following GTWR model:

where (\({u}_{i},{v}_{i},{t}_{i}\)) represents the spatio-temporal coordinates of each country i, and β (\({u}_{i},{v}_{i},{t}_{i}\)) represents the regression coefficient of the k-th independent variable (xik) of country i. t is the time distance. εi ~ N(0, σ2). Parameters of GTWR model are estimated as follows:

where Y represents the explained variable \({\rm{SDG}}_{it}\). \(W({\pi }_{i},{\varphi }_{i},{t}_{i})\) is the spatial-temporal weight matrix. Referring to the method of Huang et al. (2010), this paper constructs the spatio-temporal weight matrix based on the Gaussian kernel function and Euclidean distance, and uses the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to determine the optimal bandwidth.

At the same time, we used the GWR (Geographically Weighted Regression) model to explore the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the Belt and Road Initiative Participating Countries. We compared the results of GWR model with that of GTWR model. We found that the GTWR model has better goodness of fit and the smallest AIC value, indicting that the GTWR model is more suitable for this study.

The GWR model is a spatial regression model that allows regression coefficients to have spatial heterogeneity, meaning that regression coefficients may vary in different geographical locations. The basic idea of the GWR model is to set a local regression model near each observation unit, and estimate the regression coefficients by considering the influence of neighboring units around that observation unit. For each observation unit, the GWR model determines the weight of neighboring units by selecting an appropriate neighborhood weight function, and estimates the parameters of the local regression model using least squares or other estimation methods. The formula can be expressed as:

where \({y}_{i}\) is the dependent variable of the observation unit \(i\). \({x}_{{ji}}\) is the independent variable of the observation unit \(i\). \({\beta }_{j}\left({u}_{i},{v}_{i}\right)\) is the local regression coefficient of the independent variable \(j\) of the observation unit \(i\). \(\left({u}_{i},{v}_{i}\right)\) represents the geographical coordinates of the observation unit \(i\). \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) is the error term.

The parameters of the GWR model are usually estimated by the least squares method, that is the regression coefficients are estimated by minimizing the sum of squared residuals on the observation units. In order to determine the neighborhood weight function, commonly used methods include fixed kernel weight function and variable kernel weight function. The fixed kernel weight function treats all observation units within the neighborhood range as equal weights, while the variable kernel weight function assigns different weights based on the distance between observation units.

We compared the GWR model with GTWR model, shown in Supplementary Table 8. We found that, (1) the sum of squared residuals, standard deviation of residual estimation and the value of AICc of GTWR model are smaller than that of GWR model. (2) From the perspective of goodness of fit, the R2 and adjusted R2 of GTWR model are larger than that of GWR model. These results indicate that the GTWR model can better measure the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of the Belt and Road Initiative Participating Countries.

Entropy method

We use the entropy method to calculated the sore of SDGs. The step is as follows.

The first step is to standardize the data of indicator system.

For the positive indicators:

For the negative indicators:

where \({X}_{ij}^{{\prime} }\) is the standardized value, which denotes the value of the indicator \(j\) of country \(i\). \(\max ({X}_{j})\) and \(\min ({X}_{j})\) represents the maximum and minimum value for indicator j of all countries, respectively.

In the second step is homogenization of indicators, and we calculate the weight of indicator j of country \(i\).

The third step is to calculate the entropy (\({e}_{j}\)) of the j indicator. The smaller the entropy value, the greater the difference between the indicators, and the more important the indicator. Otherwise, the less important the indicator.

where m is the number of evaluated countries.

In the fourth step, calculating the coefficient of variability (\({a}_{j}\)) of indicator j.

In the fifth step, calculate the weight (\({w}_{j}\)) of indicator j.

where n is the number of indicators.

In the sixth step, calculating the evaluation score (\({s}_{ij}\)) of single indicator.

Results

The impact of China’s financial development on SDGs

China’s financial development has significantly promoted the SDGs of BRI participating countries (Fig. 1). Among these, the financial development scale (FIR) has the least promoting effect on SDGs. The coefficient of FIR is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (β1 = 0.0454, p < 0.01). The financial development efficiency (FE) has the greatest promoting effect on SDGs, with the coefficient for financial development efficiency being positive and statistically significant at the 5% level (β3 = 0.1444, p < 0.05). The coefficient for FS is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (β2 = 0.0643, p < 0.01). Further, we conducted sensitivity analyses by changing our financial development indicators to demonstrate the robustness of our findings (Supplementary Table 7). The coefficient of FIR remained positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (β1 = 0.0544, p < 0.01). The financial development efficiency (FE) continued to exhibit the most significant promoting effect on SDGs, with the coefficient for financial development efficiency remaining positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (β3 = 0.5809, p < 0.01). The coefficient for FS remained positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (β2 = 0.0802, p < 0.01). Furthermore, when the social financing scale is selected as the proxy variable for financial development, China’s financial development still promotes the SDGs of countries along the Belt and Road, further proving the robustness of our conclusions (Supplementary Table 9).

Differences in the impact of China’s financial development on SDGs of different types of BRI participating countries

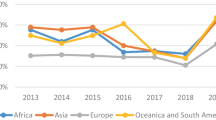

The scale, efficiency, and structure of China’s financial development have different impacts on various types of BRI participating countries (Fig. 2a). Specifically, the scale and efficiency of China’s financial development has promoted the SDGs of Asian BRI participating countries more than those of European BRI participating countries, and the financial development structure promotes the SDGs of European BRI participating countries more (Fig. 2b). China’s financial development scale has enhanced the SDGs of low- and middle-income BRI participating countries more than those of high-income countries, and the financial development efficiency and structure promote the SDGs of high- and middle-income BRI participating countries (Fig. 2c). Additionally, China’s financial development structure and efficiency has promoted the SDGs of the Land Silk Road participating countries more than those Maritime Silk Road participating countries, while China’s financial development scale has promoted the SDGs of the Maritime Silk Road participating countries to a greater extent (Fig. 2d).

a The impact of China’s financial development scale, structure and efficiency on SDGs of different BRI participating countries. b The impact of China’s financial development on Asian and European SDGs. c The impact of China’s financial development on SDGs of high-income, middle-income and low-income BRI participating countries. d The impact of financial development on the SDG of the Maritime Silk Road participating countries and the Land Silk Road.

Spatial and temporal effects of the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries

The impacts of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries exhibit spatial and temporal heterogeneity (Figs. 3–5). The positive impact of China’s financial development scale on SDGs in most BRI participating countries has gradually decreased and has become mainly concentrated in Russia, Mongolia, and Central and Eastern Europe (Fig. 3). China’s financial development scale has an inverted U-shaped structure, where the impact on SDGs of Kazakhstan, India, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and other BRI participating countries first increases then decreases.

a The impact of China’s financial development scale on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2005. b The impact of China’s financial development scale on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2012. c The impact of China’s financial development scale on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2014. d The impact of China’s financial development scale on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2018.

a The impact of China’s financial development structure on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2005. b The impact of China’s financial development structure on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2012. c The impact of China’s financial development structure on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2014. d The impact of China’s financial development structure on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2018.

a The impact of China’s financial development efficiency on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2005. b The impact of China’s financial development efficiency on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2012. c The impact of China’s financial development efficiency on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2014. d The impact of China’s financial development efficiency on SDGs of BRI participating countries in 2018.

China’s financial development structure has varying positive effects on SDGs in different BRI participating countries (Fig. 4). Specifically, the positive impacts on SDGs in Mongolia, Southeast Asia, and other BRI participating countries gradually decrease, while the positive impacts on SDGs in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iran, Iraq and other countries gradually increase. The impacts on SDGs in Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, and other BRI participating countries follow an inverted “U” shape, initially increasing and then decreasing. On the other hand, the impacts on SDGs in Russia, Afghanistan and Kazakhstan participating in the BRI exhibit a “U” shape, first decreasing and then increasing.

The impact of China’s financial development efficiency on SDGs of BRI participating countries shows a positive growth trend (Fig. 5). Notably, the positive role in promoting SDGs in Mongolia, India and most countries in Southeast Asia is increasing year by year. The impact on SDGs in Russia, Singapore, Vietnam, and other BRI participating countries has transitioned from negative to positive, but the impact on SDGs in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Turkey and other BRI participating countries has shifted from positive to negative. It has consecutively had the greatest positive impact on Central and Eastern Europe participating in the BRI.

Discussion

Different impacts of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI countries

To the best of our knowledge, our research is the first to assess the impact of Chinese finance on the SDGs of the BRI participating countries from three dimensions of development scale, structure and efficiency. As the world’s second largest economy, China introduced the BRI, bringing China into closer partnership with the BRI participating countries and promoting the establishment of strong partnerships with them (Timofeev et al., 2017; Shao, 2020). Robust partnerships are essential for the successful implementation of SDGs. China’s financial development has been highly concerned by the BRI participating countries and provided large funding for them. China’s financial institutions have taken the lead by cooperation in promoting the SDGS of BRI participating countries. At the same time, China aims to enhance its ESG (Environment, Society and Governance) practice to an unprecedented level (Chen, 2019). In China’s neighboring countries, a large number of major BRI projects have been steadily promoted, and a number of overseas economic and trade cooperation zones have been built, which plays an important role in promoting BRI participating countries to achieve the multi-field SDG in 2030. With the release of Debt Sustainability Framework for Participating Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative and the establishment of multilateral financial institutions such as the Financing Cooperation Center, Silk Road Fund, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the financial cooperation capacity has been expanded, and the docking of financial cooperation mechanisms has been strengthened. To a significant extent, this has helped bridge the substantial funding gap in developing economies, positively impacting the sustainable development of these countries.

We have discovered that the scale, structure, and efficiency of financial development have a heterogeneous impact on the SDGs of different types of “the Belt and Road” participating countries, providing development reference for the BRI participating countries. Compared with the Maritime Silk Economic Belt, low- and middle-income countries, and Asian countries, the Land Silk Economic Belt, high income countries, and European countries have more advantages in transportation and trade. China’s financial development scale has notably promoted technological progress in countries like Egypt and Iran, influencing the transformation of industrial structure, reduced pollutant emissions, and improved the sustainable development levels. However, as these countries experience increasing energy demand and consumption, the role of China’s financial development scale in promoting their SDGs gradually diminishes. In contrast, in countries like Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, and others with high technical levels, China’s financial development scale has increased the energy demand and consumption of their countries, resulting in increased pollutant emissions and reduced level of sustainable development. The influence direction of China’s financial development structure on the SDGs of BRI participating countries is uncertain. The improvement of financial development level helps to improve the efficiency of capital allocation, speeds up the flow of capital among different industries, and stimulates the adjustment of industrial structure. These changes have different effects on the SDGs of BRI participating countries (Mills et al., 2021). China’s financial development efficiency can fully concentrate the idle social funds for investment and give sufficient financial support to energy-saving and environment-friendly projects in BRI participating countries, thus promoting the SDGs of these countries. China must pay more attention to the regional heterogeneous impact of financial development on the SDGs among BRI participating countries, give full play to the efficiency of financial development, improve the efficiency of capital allocation, guide capital transfer to high-tech enterprises with R&D and innovation capabilities, boost production technology, promote industrial upgrading, and improve the level of sustainable development.

We examined the spatiotemporal characteristics of financial development driving the SDGs of the BRI participating countries, and found that the driving effect of the SDGs of most BRI participating countries gradually increases over time. In 2013, the official report stated that China allocated $1 trillion USD as seed funding, covering 890 projects in over 60 partner countries. This initiative represents the largest single-country undertaking in human history, committed to strengthening cooperation between Eurasian countries, with the prospect of changing world trade and integrating regional development. It is estimated that the BRI initiative will affect two-thirds of the world’s population, including one-third of global gross domestic product and one-third of world trade (Hafeez et al., 2018). Since the launch of the BRI, the proportion of China’s direct investment in BRI participating countries has increased year by year. According to the World Development Indicators (WDI) database of the World Bank, during the first five years (2008–2012) of the BRI being put forward, China’s direct investment on BRI participating countries totaled 40.2 billion dollars, while in the next five years (2013–2017), China’s direct investment in BRI participating countries totaled 79.5 billion dollars, which is an increase of 97.8%. By the end of June 2023, China has signed more than 200 cooperation documents with 152 countries and 32 international organizations to jointly build the “the Belt and Road.” Over the past decade, the joint construction of the “the Belt and Road” initiative has stimulated nearly trillion dollars of investment, formed more than 3000 cooperation projects, created 420,000 jobs for countries along the line, and lifted nearly 40 million people out of poverty. It is obvious that our analysis results are largely consistent with the reality, and over time, the impact of financial development on the sustainable development of most countries BRI participating countries has grown increasingly substantial.

One of our interesting findings is the impact of the scale and structure of financial development on some of the BRI participating countries, which exhibits an inverted U-shaped structure, increasing first and then decreasing. In contrast, the impact of the efficiency of financial development follows a positive linear trend. This observation aligns with the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC), which illustrates the relationship between economic development and environmental pollution as an inverted U-shaped curve, reinforcing our conclusion (Fang and Gao, 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Among these countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, we observe the inverted U-shaped structure. In the early stages of the BRI implementation, these countries gradually improved the scale and structure of their development through cooperation with China in infrastructure construction, energy cooperation and trade exchanges, thus promoting the realization of the goal of sustainable development. While the BRI has improved the efficiency of financial development in these countries, however, the scale and structure of financial development may hinder sustainable development due to the problems of national security, political instability, economic development structure and insufficient development impetus. As a result, the impact of the scale and structure of financial development on these countries shows an inverted U-shaped structure, initially increasing and then declining.

Comparison with previous studies

When discussing the relationship between financial development and the SDGs, previous studies have only focused on one specific aspect of the SDGs, such as environmental sustainability or economic sustainability (Liu, 2014; Atkinson et al., 2012; Pendrill et al., 2019; Harris and White, 2019 Zioło et al., 2023; Abid et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2023). However, compared with the previous studies, we tried to pay more attention to the overall impact of financial development on the overall SDGs, including the economic, social and environmental aspects emphasized by the SDGs. More importantly, many scholars studied the impact of financial development from a single dimension such as financial depth, financial stability, and financial institutional environment (Muhammad et al., 2022; Pata et al., 2022; Hasni et al., 2023; Elkhuizen et al., 2018). Our study stands out as one of the pioneering works that delves into the different impacts on the SDGs arising from the dimensions of financial size, structure, and efficiency, which were not available in previous studies. Ziolo et al. (2021), taking EU countries as an example, found that the more sustainable the financial model, the better the achievement of SDGs, and the financial model is closely related to social, environmental and economic sustainability. This is somewhat similar to our results, although the subject of this paper is BRI participating countries. Ronaldo and Suryanto (2022) found that green finance can achieve SDGs by promoting environmental sustainability and economic sustainability. This is similar to our main conclusions, but in general he focuses on green finance, while we focus on the size, structure and efficiency of financial development.

Limitations

Although we explored the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI countries, some limitations still remain. While we summarized the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI countries based on income and geographical conditions, the BRI involves many countries with unique economic and institutional environments, and each country has different goals in poverty reduction, economic growth, education, environmental protection and other aspects, resulting in mismatches in the communication content between donor and recipient countries (Iacobuţă et al., 2022). In the future, we can discuss the status and different aspirations of individual countries in relation to the SDGs to ensure that financial development is aligned with the achievement of the SDGs. For example, some countries may face social issues like political instability and corruption, which may limit the influence of China’s financial development. Future research should also include more SDGs (Xu et al., 2020), explore the impact mechanism of financial development on SDGs of different types of the BRI participating countries, and formulate specific and effective policies to achieve SDGs.

Policy suggestions

China may need to enchance financial efficiency by deepening the financial reform and promoting the sustainable development of BRI participating countries. Specifically, the focus should be on addressing issues related to financial resources allocation, intensifying financial innovation, and enhancing the efficiency of financial resource allocation. From the spatial-temporal effects diagram (Figs. 3–5), it can be seen that with the expansion of China’s financial scale, its positive impact on the SDGs in BRI participating countries is decreasing, which indicates that the scale should not be blindly expanded but should be kept at a moderate scale instead. If the financial scale is too large, we should change our thinking at this time, and carry out financial reform by improving efficiency or optimizing structure. Accordingly, China should continue to increase investment in BRI participating countries, rely on the scale and efficiency of financial development to promote the SDGs of BRI participating countries. At the same time, China needs to expand financial cooperation, optimize financial structure, and further enhance the promotion of the scale and structure of financial development to the SDGs. The Chinese Government should continue to strengthen financial cooperation with the BRI participating countries, realize the multi-party connection of financial systems, help BRI participating countries to formulate green financial standards, innovate financial products and enrich green financial products to support green projects. In addition, the Chinese government should give full play to the initiative of local corporate financial institutions, set up branches in major trading partners of BRI participating countries, improve the facilitation degree and utilization rate of RMB cross-border settlement, further promote the internationalization of RMB, and reduce the risk of China enterprises’ foreign direct investment. It is also suggested to further optimize the investment environment, boost global openness, and enhance China’s technology spillover absorption capacity in foreign trade and transnational investment and financing.

Conclusions

Using the panel data from 61 BRI participating countries over 2005–2018, this study employs the panel regression model to access the impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries RI, and explores the heterogeneous impact of China’s financial development on the SDGs of different types of BRI participating countries of China’s financial development on the SDGs of BRI participating countries. The conclusions are as follows: First, China’s financial development from 2005 to 2018 has had a positive impact on the SDGs of most of the BRI participating countries. The impact of the scale and structure of financial development on some of the BRI participating countries shows an inverted U-shaped structure that increases first and then decreases, while the impact of the efficiency of financial development is a positive linear feature. This understanding can drive greater support for China’s financial development to the SDGS of the BRI participating countries, as well as more coordinated and effective development of finance. Second, China’s financial development promotes the SDGs of Asian countries and low- and middle-income BRI participating countries more than those of European countries and high-income countries, and it promotes the SDGs of the Land Silk Road participating countries more than those Maritime Silk Road participating countries. In general, the inconsistencies can be caused by a number of factors: China’s financial development prioritizes which areas deserve attention (including on the basis of the approval of its supporters); BRI countries have unclear needs and priorities for their own SDGs, resulting in mismatches in communication content. Third, the positive impact of China’s financial development scale on the SDGs of most BRI participating countries gradually decreases, while the positive impact of China’s financial development efficiency on the SDGs of most BRI participating countries gradually increases. China’s financial development structure has a different impact on different BRI participating countries. Overall, this research contributes to identifying key gaps and opportunities for further aligning financial development with the SDGs.

Data availability

The provincial data used in this study can be obtained from the World Bank Open Data (https://data.worldbank.org.cn/). The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abid N, Ceci F, Ahmad F et al. (2022) Financial development and green innovation, the ultimate solutions to an environmentally sustainable society: evidence from leading economies. J Clean Prod 369:133223

Anwar A, Ahmad N, Madni GR (2020) Industrialization, freight transport and environmental quality: evidence from Belt and Road Initiative Economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27(7):7053–7070

Atkinson G, Agarwala M, Muñoz P (2012) In: UNU-IHDP, UNEP (eds). Inclusive wealth report 2012: measuring progress toward sustainability. Univ. Press, Cambridge, pp 87–117

Atta M, Zeng K, Baafifi MA (2020) The economy-energy-environment nexus in IMF’s Top 2 biggest economies: a TY approach. J Bus Econ Manag 21(1):1–22

Aust V, Moraisai, Pinto I (2020) How does foreign direct investment contribute to Sustainable Development Goals: evidence from African countries. J Clean Prod 245:118823

Chen F (2019) The belt and road and green leadership. China Investment 19:26–29

Chen S, Li Y, Lu Z et al. (2023) Investigating multi-way impacts of transportation on human footprint: evidence from China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 98:106896

Ding Q, Khattak SI, Ahmad M (2021) Towards sustainable production and consumption: assessing the impact of energy productivity and eco-innovation on consumption-based carbon dioxide emissions (CCO2) in G-7 nations. Sustain Prod Consum 27:254–268

Dogan E, Seker F (2016) The influence of real output, renewable and non-renewable energy, trade and financial development on carbon emissions in the top renewable energy countries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 60:1074–1085

Du J, Zhang Y (2018) Does one belt one road initiative promote Chinese overseas direct investment? China Econ Rev 47:189–205

Duan F, Ji Q, Liu BY, Fan Y (2018) Energy investment risk assessment for nations along China’s Belt & Road Initiative. J Clean Prod 170:535–547

Elkhuizen, Hermes, Jacobs et al. (2018) Financial development, financial liberalization and social capital. Appl Econ 50(11):1268–1288

Fang K, Wang T, He J et al. (2020) The distribution and drivers of PM2.5 in a rapidly urbanizing region: the Belt and Road Initiative in focus. Sci Total Environ 716:137010

Fang K, Xu A, Wang S et al. (2023) Progress towards Sustainable Development Goals in the Belt and Road Initiative countries. J Clean Prod 424:138808

Fang X, Gao S (2023) An empirical study on relationship between island ecological environment and socio-economic development from perspective of environmental Kuznets curve (EKC). Ocean Coast Manag 244:106819

Farhani S, Ozturk I (2015) Causal relationship between CO2 emissions, real GDP, energy consumption, financial development, trade openness, and urbanization in tunisia. Environ Sci Pollut Res 22(20):15663–15676

Hafeez M, Chunhui Y, Strohmaier D et al. (2018) Does finance affect environmental degradation: evidence from One Belt and One Road Initiative region? Environ Sci Pollut Res 25(10):9579–9592

Harris J, White A (2019) The sociology of global health: a literature review. Soc Dev 5:9–30

Hasni R, Dridi D, Ben JM (2023) Do financial development, financial stability and renewable energy disturb carbon emissions? Evidence from Asia-pacific economic cooperation economics. Environ Sci Pollut R 30(35):83198–83213

Huang B, Wu B, Barry M (2010) Geographically and temporally weighted regression for modeling spatio-temporal variation in house prices. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 24(3):383–401

Huang Y (2016) Understanding China’s Belt & Road initiative: motivation, framework and assessment. China Econ Rev 40:314–321

Huang Y (2019) Environmental risks and opportunities for countries along the Belt and Road Location choice of China’s investment. J Clean Prod 211:14–26

Huang Y (2021) Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the impact of high-speed railway on urban economy: empirical study of Chinese cities. J Transp Geogr 91:102972

Iacobuţă GI, Brandi C, Dzebo A et al. (2022) Aligning climate and sustainable development finance through an SDG lens. The role of development assistance in implementing the Paris Agreement. Glob Environ Chang 74:102509

Jiakui C, Abbas J, Najam H et al. (2023) Green technological innovation, green finance, and financial development and their role in green total factor productivity: empirical insights from China. J Clean Prod 382:135131

Li M (2020) The Belt and Road Initiative: geo-economics and Indo-Pacifific security competition. Int Aff 96(1):169–187

Li Q, Khan H, Zhang Z et al. (2022) The impact of the belt and road initiative on corporate excessive debt mechanism: evidence from difference-in-difference equation model. Sustainability 15(1):618

Liu B, Wang T, Zhang J et al. (2021) Sustained sustainable development actions of China from 1986 to 2020. Sci Rep 11(1):8008

Liu J (2014) Forest sustainability in China and implications for a tele coupled world. Asia Pac Policy Stud 1:230–250

Lv C, Shao C, Lee CC (2021) Green technology innovation and financial development: Do environmental regulation and innovation output matter? Energ Econ 98:105237

Malik A, Parks B, Russell B et al. (2021) Banking on the Belt and Road: insights from a new global dataset of 13,427 Chinese development projects. Aid Data at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, pp 23–36

Managi S, Lindner R, Stevens CC (2021) Technology policy for the sustainable development goals: from the global to the local level. Technol Forecast Soc 162:120410

Mills EFEA, Dong J, Yiling L et al. (2021) Towards sustainable competitiveness: How does financial development affect dynamic energy efficiency in Belt & Road economies?. Sustain Prod Consum 27:587–601

Muhammad S, Xu D, Avik S et al. (2022) The dynamic nexus among financial development, renewable energy and carbon emissions: moderating roles of globalization and institutional quality across BRI countries. J Clean Prod 343:130995

Nian W, Dong X (2022) Spatial correlation study on the impact of green financial development on industrial structure upgrading. Front Environ Sci 10:1017159

Novo-Corti I, Badea L, Tirca DM et al. (2018) A pilot study on education for sustainable development in the Romanian economic higher education. Int J Sust High Ed 19(4):817–838

Pata UK, Yilanci V, Zhang Q et al. (2022) Does financial development promote renewable energy consumption in the USA? Evidence from the Fourier-wavelet quantile causality test. Renew Energ 196:432–443

Pendrill F, Persson UM, Godar J et al. (2019) Deforestation displaced: trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environ Res Lett 14:055003

Rauf A, Liu X, Amin W et al. (2020) Does sustainable growth, energy consumption and environment challenges matter for Belt and Road Initiative feat? A novel empirical investigation. J Clean Prod 262:121344

Ronaldo R, Suryanto T (2022) Green finance and sustainability development goals in Indonesian Fund Village. Resour Policy 78:102839

Sadorsky P (2010) The impact of financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies. Energ Policy 38(5):2528–2535

Shao X (2020) Chinese OFDI responses to the B&R initiative: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. China Econ Rev 61:101435

Shi K, Yu B, Huang C et al. (2018) Exploring spatiotemporal patterns of electric power consumption in countries along the Belt and Road. Energy 150:847–859

Tian X, Hu Y, Yin H et al. (2019) Trade impacts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: from resource and environmental perspectives. Resour Conserv Recycl 150:104430

Tienhaara KKP (2009) Gallagher and Lyuba Zarsky, The Enclave Economy: Foreign Investment and Sustainable Development in Mexico’s Silicon Valley. Int Environ Agreem Policy Law Econ 9(1):85–87

Timofeev I, Lissovolik Y, Filippova L (2017) Russia’s vision of the Belt and Road Initiative: from the rivalry of the great powers to forging a new cooperation model in Eurasia. China World Econ 25(5):62–77

Udemba EN, Güngör H, Bekun FV et al. (2021) Economic performance of India amidst high CO2 emissions. Sustain Prod Consum 27:52–60

UN (2020) The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. United Nations, New York, NY

UNFCCC SCF (2018) Summary and Recommendations by the Standing Committee on Finance on the 2018 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Standing Committee on Finance, Bonn

Wang Z, Sun G (2003) An empirical analysis of the relationship between the scale, structure and efficiency of financial development and economic growth in China. J Manag World (7):13–20

Xiong F, Zhang R, Mo H (2023) The mediating effect of financial development on CO2 emissions: an empirical study based on provincial panel data in China. Sci Total Environ 896:165220

Xu B, Li S, Afzal A, Mirza N et al. (2022) The impact of financial development on environmental sustainability: a European perspective. Resour Policy 78:102814

Xu Z, Li Y, Chau SN et al. (2020) Impacts of international trade on global sustainable development. Nat Sustain 3(11):964–971

Yang L, Ni M (2021) Is financial development beneficial to improve the efficiency of green development? Evidence from the “Belt and Road” countries. Energ Econ 105734

Yang WJ, Tan MZ, Chu SH et al. (2023) Carbon emission and financial development under the “double carbon” goal: considering the upgrade of industrial structure. Front Environ Sci 1091537

Ying X, Ning H (2022) Financial structure, financial function and innovative development. Macroeconomics 5:35–47

Yu XK, Chen Z (2011) Financial development and environmental performance: evidence from China. Environ Dev Econ 16(1):93–111

Zafar MW, Quande Q et al (2020) Foreign direct investment and education as determinants of environmental quality: the importance of post Paris Agreement (COP21). J Environ Manage (270):110827

Zeng J, Wu W, Liu Y et al. (2019) The local variations in regional technological evolution: evidence from the rise of transmission and digital information technology in China’s technology space, 1992–2016. Appl Geogr 112:102080

Zhao J, Zhao Z, Zhang H (2021) The impact of growth, energy and financial development on environmental pollution in China: new evidence from a spatial econometric analysis. Energ Econ 93:104506

Zhao Y, Li F, Yang Y et al. (2023) Driving forces and relationship between air pollution and economic growth based on EKC hypothesis and STIRPAT model: evidence from Henan Province, China. Air Qual Atmos Health 16(9):11–16

Zhou K, Lu Y (2019) Financial structure and national innovation: evidence from OECD countries. Stud Int Finance (3):24–33

Zhuang Y, Chu Q, Ma Y (2020) Financial development, business innovation and economic growth. J Financial Res (4):11–30

Ziolo M, Bak I, Cheba K (2021) The role of sustainable finance in achieving sustainable development goals: does it work? Technol Econ Dev Econ 27(1):45–70

Zioło M, Bąk I, Spoz A et al. (2023) Relationship between sustainable development and financial development from the perspective of the European green economy. Front Env Sci 11:1244119

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Guangdong Natural Science Fund (General Programme: 2023A1515012446), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant #42101249), and the University of Hong Kong HKU-100 Scholars Fund, Guizhou Province Natural Science Research Project (Qian Jiao Ji [2023] No. 033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chenggang Li: combing the internal logic and writing the article. Gang Zhao: writing the article. Keumseok Peter Koh, Mu Yue, Zhenci Xu: modifying the article. Weiyan Wang: modified the article. Yuanyuan Tan: translate the article. Liang Wu: polishing the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Zhao, G., Koh, K.P. et al. Impact of China’s financial development on the sustainable development goals of the Belt and Road Initiative participating countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 294 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02791-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02791-2