Abstract

In the past few years, sustainable development has undoubtedly become an essential perspective for museums. Museums have been committed to raising social awareness around ecological conservation and cultural diversity through various exhibitions, education and research projects, and public engagement. However, the concepts, approaches, and practises of “sustainability” differ across nations and regions, and there is a lack of sufficient quantitative research on sustainable development by and within museums. This article aims to establish an evaluation framework and evaluation approach for museum sustainability in China. Its framework is initially based on the DSR model, in which “D” delineates seven deeds of museum visitors, “S” characterizes the status of sustainable practises within museums, and “R” involves presenting sustainability strategies pertinent to Chinese museums by integrating Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A fuzzy QFD model is then used to develop an evaluation approach for analyzing the Zhejiang Natural History Museum (ZNHM)’s sustainable development strategies, using data from surveys and in-depth interviews. As a result of this study, significant opportunities for deepening sustainable practises were identified for ZNHM, which include updating the collection system, enhancing professionalism in exhibitions and educational projects, and securing funding policies. ZNHM’s sustainability efforts prioritize enhancing social awareness, and internal reforms related to social value, governance, and professional capabilities. With these foundations in place, international cooperation among museums may be the next step towards a sustainable future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In September 2015, the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit was attended by 193 member states who unanimously endorsed the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” establishing 17 main Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)Footnote 1 and 169 specific targets aimed at global sustainability. The SDGs address key areas such as quality education, sustainable cities, environmental protection, economic growth, sustainable consumption and production, peace, inclusive societies, gender equality, and food security, highlighting the pivotal role of culture in advancing sustainable development. UNESCO promotes this strategic role of culture through cultural heritage and the creative industries, with museums exemplifying cultural entities that both drive and facilitate economic, social, and environmental sustainability. In 2022, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) introduced “sustainability” as a new attribute in its definition of “museum.” Ever since International Museum Day 2015 which was celebrated around the theme of Museums for a Sustainable Society, “sustainability” has been increasingly viewed as a key feature by the international museum community.

Sustainable development might provide a conceptual reference point that could help to reframe the role and potential of museums (Worts, 1998), such as the social value of museums (An, 2021; Brown, 2019; Cerquetti and Montella, 2021; Hansson and Öhman, 2021; Liu, 2021; Loach et al. 2017). Museums are addressing climate change through museums’ management policies (McGhie, 2020), collections (Gustafsson and Ijla, 2016), exhibitions, and educational activities (Hebda, 2007; Henry and Carter, 2021; Sutton, 2020) while implementing measures for resilience, adaptability, and disaster preparedness. Through energy-efficient practises, museums also aim for carbon neutrality or net-zero greenhouse gas emissions (Balocco and Marmonti, 2012; Morgan and Macdonald, 2020; Sharif-Askari and Abu-Hijleh, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic, moreover, has accelerated museums’ adoption of digital technologies, allowing them to reach wider audiences, reduce physical consumption, and enhance accessibility while maintaining educational and cultural engagement (Ahmed et al. 2020; Hamdy and Nagib, 2022; Rivero et al. 2020). Diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (Giliberto and Labadi, 2022), as well as community engagement (Málaga and Brown, 2019) are topics that museums are increasingly concerned with as part of their sustainability initiatives. Museums serve as catalysts for heritage and cultural tourism, digital cultural industries, and other aspects of the creative sector (Gustafsson and Ijla, 2017). Sustainability in museums is, therefore, critical to ensuring environmental responsibility, preserving cultural heritage, educating the public, promoting social equity, sustaining economic viability, inspiring positive change, and making them important cultural institutions.

SDGs in museum sustainability

The complex nexus between SDGs and museum practises is documented in various studies (Cerquetti and Montella, 2021; Faheem and Abduraheem, 2021; Hansson and Öhman, 2021; McGhie, 2019; Rivero et al. 2020). A great deal of effort is being put into forming partnerships and collaborations with other institutions, universities, and communities to share knowledge, resources, and best practises for achieving SDGs (McGhie, 2019), such as improving the quality of life (SDGs 1/2/3/6), ensuring the sustainability of human society (SDGs 7/9/11/12/17), ensuring inclusion and equity (SDGs 4/5/8/10/16), and focusing on climate and ecology (SDGs 13/14/15). Institutions like the Network of European Museum Organisations (NEMO) and International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) have curated reports delineating museum-related SDG targets for museum practises. Prominent museums such as the National Museum of Australia, TATE, and the National Museum of Singapore have published their own Sustainability Action Plans guided by the SDGs. Nevertheless, there has been a growing need to establish a sustainability framework to guide museums wishing to align their practises with the SDGs. For instance, the Italian National Museum System (NMS) employs sustainable development indicators as evaluation criteria for museums (Cerquetti and Montella, 2021). Drawing from a visitor-centered museum sustainability framework (Di Pietro et al. 2014), experts have examined different factors that affect sustainability within institutions, including environmental, social, economic and cultural (Ásványi et al. 2021; Pop and Borza, 2015). They have also argued that sustainable practises within museums encourage continuous support from the government, donors, stakeholders, and others (Pop et al. 2018, 2019).

Museum sustainability and regional differences

The new definition of “museum”, adopted by ICOM in 2022 and for the first time including the term “sustainability” as a key attribute, is seen as critical to ensuring environmental and ecological responsibility, preserving cultural heritage, educating the public, promoting social equity, sustaining economic viability, inspiring positive change, and ensuring that museums remain relevant as cultural institutions. However, the inclusion of the term “sustainability” in the new museum definition also represents the “greatest common divisor” within the international community, with significant national variations in how institutions understand and implement sustainability principles. As Brown (2019) suggests, “think global, act local” has become an important ability for museums. While over a decade ago museum sustainability was believed to be a function of appropriate entrepreneurial strategy (Durel, 2009; Merriman, 2008; Schaltegger and Wagner, 2011), “cultural sustainability” has recently gained traction as a fourth aspect of museum sustainability (Arenas and Medina, 2021; Pencarelli et al. 2016; Pop et al. 2019; Stylianou-Lambert et al. 2014). In the aftermath of the pandemic, museums worldwide are facing significant challenges, not only due to a lack of funding but also in terms of meeting sustainable development goals (Choi and Kim, 2021; Grincheva, 2023). Thus, sustainable priorities and aspirations vary greatly between countries and cultures. One museum may prioritize “saving money” while another may “rescue creative interactions” (Arenas and Medina, 2021, p. 114). Considering these national and regional differences in attitudes and practises around sustainability, in China, museums are primarily state-owned and, thus, differ from “sustainopreneurship” (Howaldt et al. 2012, p. 187) in their approach to sustainability. According to the National Cultural Heritage Administration, there were 6833 Chinese museums in 2024, 91 percent of which offered free admission, and attracted 1.29 billion visitors. It is undeniable that visitors have a considerable influence on shaping the direction of museums in China. In the wider context of sustainable development in ChinaFootnote 2, museums have been adopting a variety of practises, yet challenges remain. These include limited understanding and dissemination of sustainability concepts among museum professionals; a lack of mission awareness within museums; insufficient professionalism among staff; inadequate attention to special populations such as disabled visitors; uneven development across different types of museums in various regions; a need for innovation in both external frameworks and internal management; and a critical need for increased social engagement. Thus, the principles of sustainability relate to two core aspects: (1) building deep, long-term relationships with a wide range of visitors; and (2) responding to changing political, social, environmental, and economic contexts, and having a clear long-term purpose that reflects society’s expectations (Di Pietro et al. 2014, p. 5746).

Evaluating museum sustainability

Despite the clearly deepening ties between the broader field of sustainable development, museums and cultural institutions, previous studies have mainly focused on defining museum-based sustainable development and illustrating the need to incorporate sustainable approaches into museum practises. However, the effectiveness of such approaches is still under active discussion and assessment, and it is important to evaluate the sustainable impact of museums both qualitatively and quantitatively. Evaluating a museum involves assessing whether a museum is fulfilling its stated key functions and contributing to society (Drochter, 2015; Reussner, 2003; Weil, 2007). For example, the SERVQUAL and HISTOQUAL modelsFootnote 3 have been used to evaluate visitor service quality in museums (Benjawan et al. 2018; Daskalaki et al. 2020; Kowalska and Ostręga, 2020; Markovic et al. 2013). Evaluating museums is moreover often tied to their relationships with urban development, culture, education, or science and technology (Benito et al. 2014; Lak et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2017). As museums become more inclusive in terms of knowledge and innovation, museum professionals, are turning their attention to the external environment and the social impact of their institutions (Azmat et al. 2018; Loach et al. 2017). For example, the impact of museums’ on sustainable tourism is a topic of particular interest (Ghoochani et al. 2020; Navarro et al. 2019; Neupane, 2016).

Therefore, the alignment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with the museum sector, the unique and common characteristics of museum sustainability, methods to assess sustainability in museums, and the development of a sustainable evaluation framework for museums in China are explored. The academic research questions of this article can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

How does a museum define its sustainability strategy in accordance with the 17 SDGs and the 169 sub-goals in Transforming Our World: 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development?

-

(2)

To achieve sustainable development, what indicators should be focused on from the perspective of the visitors and the museum’s development?

-

(3)

What evaluation framework can be established to address stakeholders’ needs for museum sustainability and translate these needs into museum sustainability strategies?

-

(4)

What kind of evaluation method should be designed for the museum sustainable development evaluation framework?

In light of these developments worldwide, it is crucial to establish an effective measurement system for the sustainability of museums in China. This article accordingly aims to assess museum sustainability both qualitatively and quantitatively. It is structured into five sections to develop an evaluation framework for museum sustainability in China. The second section introduces the DSR model, establishing three qualitative indicators for museum sustainability: needs (D), state (S), and response (R). The third section employs the FF-PSI-SWARA-MARCOS method-based QFD model to construct a quantitative mathematical evaluation framework using the aforementioned indicators. The FF-PSI-SWARA model determines the importance of D and S indicators, while the FF-MARCOS approach prioritizes sustainability strategies R. The fourth section validates the model’s practicality through empirical research, focusing on the Zhejiang Natural History Museum (ZNHM) case study. Methods such as questionnaires, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, expert scoring, and fuzzy decision analysis confirm the model’s effectiveness. The discussion section analyzes the model’s construction and its contributions to the museums in China, addressing the study’s limitations. The article concludes with empirical findings and sustainable development strategies and priorities for museums based on the evaluation framework.

Evaluation indicators for museum sustainability based on DSR model

The pressure-state-response (PSR) framework is commonly utilized by academic researchers when determining how well an institution is fulfilling sustainability objectives (Markovska-Simoska et al. 2013). This model was initially used by the government as a method of analyzing economic, budgetary, and environmental issues (Rapport and Friend, 1979) through the lens of the “cause-effect-response” concept. In the 1990s, the PSR model was further developed by the OECD and UNEP (OECD, 2003). This improved model, called DSR, follows the logic of “driving force-state-response”, in which the “D” (driving force) represents the factors (i.e., human behaviors, processes, and lifestyles) that impact sustainability, the “S” represents the “State,” referring to the current status of sustainability initiatives and benchmarks, while “R” stands for “Response,” denoting strategies for sustainability. The DSR model is widely used in fields relating to economics, society, and culture, including the museum sector.

The DSR model is also applicable to museums in China for three main reasons. First, the sustainability needs of Chinese museums stem from the requirement to better meet visitors’ needs, thereby gaining positive reputation and promoting healthy operations. This necessitates a deeper understanding of visitors’ expectations, represented by the “D” for needs drivers in the DSR model. Second, due to significant regional variations in the sustainability practises of museums in China, there are diverse motivations and goals for sustainable development. This requires an assessment of the current state of museum sustainability, where “S” in the DSR model represents the state analysis, prompting different actions for different states. Third, the varying degrees and directions of sustainable development require Chinese museums to adopt distinct strategies and prioritize differently, hence “R” in the DSR model stands for response strategies. The DSR model considers the connections between different factors to promote sustainable development within museums and assess the quality of such development. Understanding the needs of visitors (Driving Force) can help museums address challenges related to collections, exhibitions, educational activities, and public services (State). By incorporating the SDGs into their sustainability strategies (Response), museums can establish a positive “Driving Force-State-Response” cycle of sustainable development (Fig. 1).

Driving force indicators—the needs of visitors

According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, visitor experience in the museum can be divided into seven types of needs (Fig. 2). In this regard, physical comfort (Convenient and safe facilities, D1) is an indispensable part of museums’ service to the public: one aim being to satisfy visitors’ physiological and safety needs. Visitors tend to view their experience as a whole one, comprising exhibitions, educational activities, shops, restaurants, restrooms, and staff friendliness (Quality offerings, D2; Diversified services, D3; Positive interactions, D4), which relate to social and esteem needs. Meanwhile, the museum’s collections and exhibits, which tell stories and reveal knowledge behind them(Attractive exhibitions and education events, D5; Abundance and diversity of collections, D6), can satisfy visitors’ “intellectual leisure” needs as well as gradually fulfill their cognitive and esthetic needs during their visit. Meanwhile, museums are adopting digital methods to enhance visitors’ creativity (Innovative environment, D7), respond to their motivation to explore their self-value and satisfy their need for self-actualization. By meeting these criteria, museums can create a more conducive setting for fulfiling Maslow’s final requirement, “transcendence,” which involves achieving a state of “flow”.

This figure applies Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the context of museum visitor experiences. It illustrates how museums fulfill various needs, starting from basic physiological needs with convenient and safe facilities (D1) to safety needs, belonging and love needs through diversified services and positive interactions (D3 and D4), esteem needs with quality offerings (D2), cognitive and aesthetic needs with attractive exhibitions and the abundance and diversity of collections (D5 and D6), and finally self-actualization through an innovative environment (D7).

Drawing on the aforementioned concepts and a literature review on the needs of museum visitors, this article aims to identify the indicators that museums should take into account when determining their driving forces. By bringing together professional practises in museums in several key categories, the following indicators (Table 1) can be identified:

State indicators—the status of sustainable practises within museums

A museum’s state is shaped by its underlying driving force/forces, and vice versa. We have defined indicators of museum sustainability based on the Museum Grading Evaluation Method and Museum Operation Evaluation Standards Footnote 4set by the National Cultural Heritage Administration in 2019. These indicators include aspects of “standard management” (including organizational management, collection management, public management, and safety management), “service output” (including scientific research, exhibition, education, and cultural communication), and “social evaluation” (including visitor feedback and social impact). To gather data related to these practises, we conducted in-depth interviews with 21 senior staff from various positions at the ZNHM (see Appendix 1 for details) and then identified six state indicators from the interviews: exhibition and education services, collection system, scientific research, organizational management, cooperation and reciprocity, and funding policies (Table 2).

Response indicators—museum sustainability strategies

Essentially, the museum’s response aims to meet the needs of visitors, as well as to improve the state of museum sustainability in accordance with the 17 SDGs and the 169 sub-goals in Transforming Our World: 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Ten relevant indicators were identified from the sub-goals, derived through a systematic review of literature and discussions among museum experts. In this article, the museum sustainability strategies (R - Response in the DSR model) are analyzed through the lens of social awareness, cooperative support, and internal reformFootnote 5, which are synthesized from the specific content of ten identified indicators (Fig. 3 and Table 3Footnote 6).

Measuring “social awareness”

Measuring aspects of social awareness as part of an assessment of museum-based sustainable development requires considering two aspects of museum practises: spreading knowledge about environmental protection (R1) and advocating for education on sustainable development (R2). Museums have the power to spread knowledge about protecting the environment and preserving ecosystems through their collections, exhibitions, and educational activities. This helps them respond better to natural disasters such as climate change, extreme weather and floods (SDG 2.4). To improve the professional skills of museum staff and volunteers in these areas, museums include topics such as climate change and environmental protection in their practises (SDG 13.3). Museums create educational activities that align with their mission which ensures visitors can acquire the necessary knowledge for implementing their own sustainable practises. These activities include education on topics of sustainable development, promoting a healthy lifestyle, upholding human rights, achieving gender equality, fostering a culture of peace and nonviolence, promoting global citizenship and respecting cultural diversity (SDG 4.7). Museums aim to be inclusive, welcoming visitors of all ages, genders, abilities, races, ethnicities, religions, economic backgrounds, and any other differences. This creates a friendly and enthusiastic environment for all (SDG 10.2).

Measuring “cooperative support”

Fostering cooperative support for museum-based sustainable development involves four key factors: enhancing collaboration with social forces (R3), improving cooperation between different institutions (R4), integrating local tourism and development (R5), and strengthening international cooperation (R6). Museums actively encourage and facilitate effective partnerships with the public and private sectors to involve social forces in museum professional practises (SDG 17.17). To ensure that museum practises are responsive to public opinion and inclusive of all stakeholders, museums seek input and suggestions from various parties when making decisions (SDG 16.7). Museums promote interinstitutional collaboration by engaging in joint research projects such as seed and plant banks, and by promoting the use, construction, and sharing of genetic resources (SDG 2.5). Museums prioritize international exchanges and sharing (SDG 17.9), develop and implement policies that foster integration with local tourism, generate employment opportunities, and revitalize local communities (SDG 8.9).

Measuring “Internal reforms”

Museums need to undergo internal reforms to address key aspects of sustainability including improving the recycling of resources (R7), enhancing sustainable professional capabilities related to heritage (R8), promoting social value through public sphere governance (R9), and optimizing institutional planning and management systems to align with sustainability goals (R10). It is important to significantly increase the use of renewable energy in museum buildings, improve water efficiency, ensure sustainable water use (SDG 6.4), and implement effective recycling measures (SDG 7.2). Museums make efforts to collect, preserve, research, interpret, display, and communicate cultural and natural heritage (SDG 11.4). They also provide safe, accessible, and environmentally friendly public spaces for all visitors, with a focus on the needs of women, children, the elderly, and those with disabilities (SDG 11.7). Creating an equal employment environment is crucial to ensure the full participation of female professionals in the museum’s affairs, including decision-making and leadership at all levels (SDG 5.5). Museums also help promote mental health and well-being through their collections and activities (SDG 3.4). Sustainable development should be integrated into museums’ missions, collection policies, and development plans (SDG 12.6) while considering the values of protecting ecosystems and biodiversity (SDG 15.9) through environmentally responsible and transparent practises (SDG 16.6).

Evaluation approach for museum sustainability: a fuzzy QFD model

QFD serves as a systematic methodology that transforms customer requirements into service features and is broadly utilized in social and management science evaluations, delivering robust theoretical backing for practical evaluation challenges. The essence of QFD lies in adopting the customer’s viewpoint to identify their needs, translating these into technical attributes, and formulating a scientifically sound and reasonable plan to satisfy these requirements. The evaluation of museum sustainability can be seen as a systematic process that considers the needs of visitors and the status of sustainable practises within museums, establishes the relationship between such requirements (from visitors/museum) and museum’s sustainability strategies, and determines the optimal strategies for the museum.

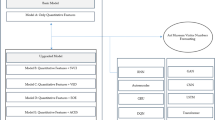

A museum sustainability evaluation approach is described based on QFD and the characteristics of museum sustainability evaluation issues. The QFD model is utilized to analyze the needs of visitors and the status of sustainable practises within museums (D and S), and then shift them into the museum’s sustainability strategies (R). Hence, QFD can be regarded as a multiple-criteria decision-making problem through considering the criteria (D and S), and alternative (sustainability strategies R). Furthermore, the evaluation process has high uncertainty because of the complexity of the evaluation environment. D and S also involve uncertainty and vagueness owing to the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty of visitors’ cognition ability. A QFD model is characterized by fuzziness because of the uncertainty of evaluating subject preferences. Accordingly, this article establishes a museum sustainability evaluation approach by combining QFD model, FF set (Senapati and Yager, 2020), SWARA (Keršuliene et al. 2010), PSI (Maniya and Bhatt, 2010), MARCOS (Stević et al. 2020) for evaluating sustainability strategies in museums (Fig. 4). The FF set will be used to effectively overcome the fuzziness and uncertainty of expert evaluation. The FF-PSI-SWARA signifies the comprehensive weight determination method of criteria, in which FF-SWARA and FF-PSI methods are used for estimating the subjective and objective weight of D and S indicators. The FF-MARCOS method is utilized to ascertain the prioritization of R indicators. A detailed description of the propositions and steps can be found in Appendix 3.

This figure presents the theoretical approach and methodology for evaluating the sustainability of Chinese museums. It first outlines the construction of evaluation indicators using the DSR model, incorporating synthetic weights identified by the FF-PSI-SWARA-MARCOS method and QFD model. It then details the evaluation process, including visitor and expert questionnaires, and the integration method to develop the evaluation matrix in the empirical analysis of ZNHM’s sustainable development.

Empirical analysis and results: evaluating sustainable development at the ZNHM

This study developed a framework for evaluating the sustainable development of Chinese museums based on the DSR model, and constructed the evaluation approach employing the QFD model. In this section, we select a Chinese museum as an evaluation object for sustainable development to verify the operability of the proposed evaluation framework and method. In the museum sustainable evaluation, we mainly focus on three tasks: (1) To obtain corresponding questionnaires based on the evaluation framework; (2) To use the FF-SWARA-PSI method to calculate the weights of the D and S indicators based on the results of the questionnaire survey; (3) To use the FF-MARCOS method to obtain the importance ranking of sustainability strategies. The evaluation results obtained from the proposed evaluation approach can provide support and guidance for promoting the sustainable development of the museum.

Zhejiang Natural History Museum (ZNHM) was established in 1929 and aims at improving the public’s scientific, cultural, and eco-environmental literacy. It is a natural history museum incorporating collection research, popular science education, and cultural exchange. ZNHM has two branches in Hangzhou and Anji. The Hangzhou branch opened in July 2009, covering 20 acres with 26,000 square meters of building space. There are five permanent and four temporary exhibitions. Anji’s branch opened in December 2018 on 333 acres with 61,000 square meters of construction space. There are six main exhibition galleries: geology, ecology, Behring collection, ocean, dinosaur, and natural art. ZNHM is a national first-grade museum and one of the pioneers in exploring sustainable development practises in China. It has its own sustainability action plan and is among the few domestic museums that incorporate sustainability as part of their core mission. At the same time, ZNHM is an innovator in museum sustainable development practises and its strategies are representative of the Chinese museum community (Table 4).

A case study examining sustainable development at ZNHM was conducted to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed FF-PSI-SWARA-MARCOS methodology. The evaluation committee comprises museum professionals including museological experts, museum staff, and researchers. We (the researchers) designed three questionnaires (see Appendix 2 for details) and obtained 769 responses on visitors’ needs (D), 45 responses on ZNHM’s sustainability status (S), and six responses on the museum’s sustainability strategies (R). According to the proposed FF-PSI-SWARA method, the importance ratings for visitor needs and sustainability status are determined based on data drawn from 769 and 45 questionnairesFootnote 7, respectively. Considering the complexity of the decision environment and the uncertainty of expert cognition, six experts evaluated the correlation between sustainability strategies (R) and indicators (D and S) with the ten-level linguistic scale. The proposed FF-PSI-SWARA-MARCOS based QFD model was applied to rank the importance of sustainability strategies (see Appendix 3 for details).

Further, we also execute a brief comparison analysis to validate the effectiveness and feasibility of the model. The compared methods include FF-WSM method, FF-WPM method, FF-WASPAS method and FF-ARAS method. The results and rankings of sustainability strategies are displayed in Table 5. From the comparison outcomes, we can observe that the ranking of sustainability strategies attained using the proposed QFD model is consist with the existing methods, which validates the validity of the presented QFD model.

In summary, we used the DSR model to evaluate museum sustainability strategies (R) for optimizing visitor needs (D) and enhancing sustainable museum practises (S). Based on the 769 visitor questionnaires we gathered and by using the FF-PSI-SWARA approach to analyzing it, we have ranked and expressed the importance of driving forces for museum-based sustainable development through the formula \({D}_{3}\,\succ {D}_{7}\,\succ {D}_{2}\,\succ {D}_{4}\,\succ {D}_{6}\succ {D}_{1}\,\succ {D}_{5}\,\)(Table 6). In this ranking model, diversified services, therefore, become the most significant driving force. An in-depth interview with 21 museum staff (see Appendix 1 for details) and questionnaires were sent to 45 museum professionals to assess sustainability levels at the ZNHM, with its ranking of importance expressed as \({S}_{2}\,\succ {S}_{1}\,\succ {S}_{6}\,\succ {S}_{4}\,\succ {S}_{5}\succ {S}_{3}\,\)(Table 6). Thus, priority should be given to optimizing collection systems.

We propose a total of ten strategic measures for museums to apply, falling under three main categories: social awareness, cooperative support, and internal reforms, which are evaluated using a QFD model. Six experts, including museum scholars, museum curators, and government officials responsible for museum administration, completed long questionnaires to examine the relationship between strategy(R), visitor needs(D), and state (S). The ranking of sustainability strategies is expressed as \({R}_{1}\,\succ {R}_{2}\,\succ {R}_{9}\,\succ {R}_{8}\,\succ {R}_{10}\succ {R}_{6}\,\succ {R}_{4}\,\succ {R}_{3}\,\succ {R}_{7}\,\succ {R}_{5}\) (Table 6). Concretely, this suggests that museums should make social awareness their primary focus in implementing a sustainable development strategy, while giving priority to promoting social values through public governance, professional capabilities, and operational excellence in internal reforms.

Discussion

Museums have a close relationship with sustainable development. On one hand, museums are instrumental in advancing the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with museum practises supporting these goals (Cameron, 2022). Conversely, museum development also necessitates the SDGs, which offer a vision and action framework for museums’ progress. Many aspects of the SDGs align with the inherent qualities of museums, thus, scholars internationally have introduced museum practises that aid in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (McGhie, Harrison and Sterling, 2022; McGhie, 2019), however, in the Chinese context, research and practise linking museum sustainability with the SDGs are nearly absent. Therefore, this article proposes strategies for museum sustainability aligned with the SDGs, specifically the “R” indicators within the DSR model. Beyond the “R” indicators, it also focuses internally on museum sustainability, addressing how to meet visitor needs (“D” indicators) and improve current practises (“S” indicators). By incorporating the DSR model into museum sustainability research, this article breaks away from the traditional paradigm that often focuses on a single aspect or factor, introducing an innovative evaluation framework to the museum field.

Research on museum sustainability has predominantly been qualitative or case-study based, with few quantitative studies. This paper connects the needs of visitors, the status of sustainable practises within museums, and museum sustainability strategies through the DSR model. It introduces an evaluation approach based on QFD, aiming to integrate perspectives from various stakeholders (such as museum visitors, staff, managers, and academic experts) to determine the importance and priority of museum sustainability strategies. In addition, considering the complexity of the evaluation procedure and the uncertainty of the cognitive capability of the evaluation experts, Fermatean fuzzy set is utilized to more accurately represent the vague and uncertain evaluation information of the experts, thereby making the evaluation results more scientific and reasonable. In summary, this article offers a systematic approach and pathway for advancing research on sustainable development in Chinese museums from qualitative to quantitative analysis.

This research’s significance is twofold, with the initial aspect being that the DSR-based evaluation framework addresses both external and internal elements of museum sustainability. Externally, the linkage between museums and sustainable development signifies the museums’ mission commitment, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This alignment represents the orientation and practical meaning of the “R” in DSR, emphasizing the integration of SDGs to propose museum sustainability strategies; Internally, the capacity of museums to fulfill their mission is embodied in their sustainability, reflecting the intrinsic motivation of museums. This represents the internal perspective of the “D” and “S” in DSR, with museum sustainability demonstrated through meeting visitors’ needs internally and enhancing and updating based on the museum’s internal sustainable development status.

Meanwhile, quantitative research methods provide concrete data support for the effects and impacts of museum sustainability. It is well known that recognizing the significance and value of museum sustainability does not imply immediate achievement of sustainable development, as it is a spiral process rather than a linear one. This has led to an internal debate within museums between the “intrinsic” and “instrumental” values of sustainability. Understanding museum sustainability policies requires first grasping their purpose, especially as these policies increasingly relate to social, economic, and political outcomes. Cultural institutions and local cultural administrations have been key proponents of policy “attachment” strategies, where short-term tactics dominate by linking sustainability to various local outcomes. Sustainable development policies thus become instrumental in addressing a range of cultural, economic, and social issues within museums (Belfiore and Bennett, 2007; Gibson, 2008; Hadley and Gray, 2017). These instrumental policies require explicit evaluation systems to determine their effectiveness. However, a mechanism to assess the orientation and extent of museums’ sustainable development has not yet been established. Consequently, while governments emphasize museums” sustainable development responsibilities such as enhancing cultural participation and local revitalization, they lack clear evaluations of the effects and impact of such sustainability, which are crucial in short-term strategies. Particularly for local museums in China operating on government budgets, museum professionals need to not only know how to promote sustainable development but also demonstrate the capability of their practises to achieve the desired outcomes. In summary, there is a lack of an evaluation mechanism for sustainable outcomes in current museum sustainability policies in China, limiting the breadth and depth of sustainable development. Therefore, this article is distinct in its quantitative approach to the sustainable development of Chinese museums, proposing an evaluation framework and approach based on the DSR model. It further validates the proposed set of indicators and evaluation method through an empirical study conducted at the Zhejiang Natural History Museum, providing a reference for effective assessment of sustainable development within the museums in China. Future work will involve empirical research on a more diverse range of museum types and expand the geographical scope of museums, to enhance the practical testing of the evaluation framework.

Conclusion

As highlighted in the 2023 Museum International Day theme, “Museums, Sustainability, and Wellbeing,” the value of museums in sustainable development and their relationship with the SDGs has been emphasized through various practises such as educational programmes, exhibitions, community activities, and research. However, it is essential to acknowledge the considerable variations in the meaning, patterns, and practises of sustainability across different nations, regions and cultures. The Chinese museum sector has gradually increased its focus on sustainability. This has been particularly significant in the aftermath of the pandemic, where measures such as offering free admission and the extension of opening hours have become more widespread among museums in China. This article thus outlined an evaluation framework for museum sustainability suitable for Chinese museums, facilitating museum professionals’ efforts at taking targeted actions.

In the framework of constructing indicators for sustainability within China-based museums, the level of museum-based sustainable development is strongly linked to visitors’ needs (referred to as the “Driving Force,” “D”). According to the ranking of seven major needs of visitors (\({D}_{3}\,\succ {D}_{7}\,\succ {D}_{2}\,\succ {D}_{4}\,\succ {D}_{6}\succ {D}_{1}\,\succ {D}_{5}\,\)), in the perception of visitors, a sustainably developed museum should primarily offer a variety of services. And foster an innovative environment and provide quality experiences. In this regard, museums need to prioritize service-oriented initiatives. These may include online and in-person communication platforms, guided tours, appreciation sessions, and information services. Further innovations in creative products, sales models, sustainable practises for in-museum consumption as well as resource conservation and low-carbon initiatives are essential. In parallel, the level of digitization should be enhanced. Taking the Zhejiang Natural History Museum as a case study (\({S}_{2}\,\succ {S}_{1}\,\succ {S}_{6}\,\succ {S}_{4}\,\succ {S}_{5}\succ {S}_{3}\,\)), the current status of sustainable practises (referred to as the “State”, or “S”) indicates that Chinese museums need to focus more on improving their collection systems, the professionalism of the exhibitions and educational services, and securing financial support for sustainable growth. In other words, there is room for improvement in these areas in China, for instance, quality and diversity of collections, conservation of cultural heritage, and digitization. The enhancement of exhibitions and educational services can result in museums engaging social forces and collaborating with institutions to receive additional funding assistance. When looking at the SDGs that are closely related to museums and the corresponding rankings (\({R}_{1}\,\succ {R}_{2}\,\succ {R}_{9}\,\succ {R}_{8}\,\succ {R}_{10}\succ {R}_{6}\,\succ {R}_{4}\,\succ {R}_{3}\,\succ {R}_{7}\,\succ {R}_{5}\)), museums should begin their sustainability strategies (referred to as the “Response”, or “R”) by promoting social awareness, followed by implementing internal reforms that highlight their social value and governance capabilities. As social awareness and internal reforms progress, the next step would be to consider international cooperation with museums.

In addition, the sustainable development practises and strategies between various types of museums can vary significantly. In this study, we specifically focussed on the natural history museum, which places a stronger emphasis on spreading ecological awareness and views environmental protection as one of its core missions. Future research will examine Chinese museums’ sustainability framework through the lens of a diverse range of museum types, including historical and art museums. For the sustainable development evaluation of other museums, due to the different actual situations of museums, the weights of D and S indicators, and the importance of R indicators are different. For example, if a certain museum is selected as the evaluation object, the data obtained based on the survey are different, so the evaluation results on the sustainable development strategy are also different. Of course, the proposed evaluation framework and methods should be improved in practice. Furthermore, because of the dynamic nature of sustainable development in museums. The D, S, and R indicators in the evaluation framework will have dynamic changes and need to be dynamically adjusted, which is also a research direction that we will continue to focus on in the future.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are: SDG 1. No Poverty, SDG 2. Zero Hunger, SDG 3. Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4. Quality Education, SDG 5. Gender Equality, SDG 6. Clean Water and Sanitation, SDG 7. Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9. Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 10. Reduced Inequality, SDG 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities, SDG 12. Responsible Consumption and Production, SDG 13. Climate Action, SDG 14. Life Below Water, SDG 15. Life on Land, SDG 16. Peace and Justice Strong Institutions, SDG 17. Partnerships to achieve the Goals.

China recognizes sustainable development as a core issue and has established comprehensive strategies and active measures towards its achievement. The Fifteenth CPC National Congress designated sustainable development as an essential strategy for modernization, which was further emphasized in the Scientific Outlook on Development introduced at the Sixteenth Congress. The Nineteenth Congress report’s vision of innovative, coordinated, green, and open development encapsulates China’s sustainable development strategy tailored to its unique context. In September 2015, President Xi’s speech, entitled Towards a Mutually Beneficial Partnership for Sustainable Development underscored China’s dedication to the UN 2030 Agenda. The 2016 report entitled China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development outlines achievements, experiences, opportunities, challenges, guiding principles, implementation paths, and action plans for the 17 SDGs, serving as a guideline for China’s initiatives and a reference for other nations, especially developing countries. Since 2017, China’s Progress Report on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has provided an annual review of the country’s SDG efforts. In the realm of cultural heritage, the government proactively explores sustainability. On May 17, 2013, the “Culture: Key to Sustainable Development” international conference in Hangzhou, co-hosted with UNESCO, resulted in the Hangzhou Declaration, which advocates for culture’s significant role in sustainable development policies. Guided by the government, China has introduced and continues to adopt innovative institutional and international cooperations to facilitate the realization of the SDGs.

Both SERVQUAL and HISTOQUAL are models used in the field of marketing, particularly for evaluating service quality. The SERVQUAL model was developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry in 1991. It is a multi-item scale used to measure service quality by focusing on the gap between customer expectations and perceptions of the service received. The HISTOQUAL model is specifically designed for evaluating the quality of historical tours and guides. It was developed by Ryan and Martin in 1992 as an adaptation of the SERVQUAL model to the context of heritage tourism services.

The “Museum Grading Evaluation” by China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration, comprising 15 articles, lays out specific requirements for assessment. These include adhering to principles of fairness, justice and transparency, and adopting a mechanism of “government guidance, social participation, and independent operation”. The Administration is responsible for formulating evaluation methods and standards, as well as for guiding the China Museums Association in assessing first, second, and third-tier national museums. The assessment process encompasses qualitative and quantitative analysis, site inspections and comprehensive reviews. Outcomes are categorized into four grades: excellent, qualified, basically qualified, and unqualified.

Meanwhile, the “Museum Operation Evaluation Standards” issued alongside the “Museum Grading Evaluation” comprise eight main categories, setting forth the criteria and methods for the graded evaluation of museums. These standards clarify a three-tiered evaluation framework, encompassing management norms, service output and social evaluation. Evaluation methods include both qualitative and quantitative assessments, supplemented by additional items under each tiered index. Inspection points encompass various cultural and tourism-related indicators, such as the museum’s annual public accessibility, implementation of free admission policies or concessions for specific groups, the addition or renewal of visitor facilities dedicated to rest and sanitation, cultural product sales, catering, and services for the elderly, disabled visitors and infants. The “Museum+” strategy promotes interdisciplinary collaboration with educational, scientific, and tourism institutions. Museums are also assessed for the resources allocated to youth groups for educational activities themed around patriotism, revolutionary heritage, Chinese traditional culture, ecological civilization, national security, etc. Additionally, annual visitor numbers, temporary exhibition attendance, international visitors, free admissions and controlled entries are considered in the assessment”s weight and inspection points. More information on the “Museum Grading and Evaluation Measures” can be found at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-03/26/content_5495770.htm [Accessed 9 May 2021].

The categorization into three parts primarily references Jasper Visser’s lecture at NEMO’s European Museum Conference 2019 titled “Museums and the Sustainable Development Goals” (7 November 2019). In this lecture, the roles of museums in association with the SDGs are divided into three categories: Lead the way, Support others, and Change internally. More information can be found at: https://www.ne-mo.org/news-events/article/introduction-to-the-sustainable-development-goals-from-a-museum-perspective [Accessed 23 May 2024].

This paper integrates the Toolkit developed by ICCROM and its corresponding cases (https://ocm.iccrom.org/), along with expert interviews and the research team’s own museum studies and professional experience, to selectively align with the SDGs relevant to R indicators.

In this study, a questionnaire with 23 items was administered to 769 participants to assess the reliability of the “D” indicators. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was high, α = 0.951, indicating that the items have a high internal consistency. Thus, the questionnaire is deemed highly reliable for use in research. The result of KMO from our study is 0.984, which represented that the dataset is acceptable at a reasonable level. Hence, the data were correlated and have sampling adequacy. For the “S” indicators, 45 participants completed a questionnaire covering 6 items. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was high, α = 0.915, indicating that the items have a high internal consistency. The value of KMO statistics is 0.867, which represented that the dataset is acceptable at a reasonable level. Hence, the data were correlated and had sampling adequacy.

References

Abacı O, Kamaraj I (2009) Museums as an educational medium: an implementation model. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 1(1):1337–1341

Ahmed ZA, Qaed F, Almurbati N (2020) Enhancing museums’ sustainability through digitalization. In: Proceedings of the second international sustainability and resilience conference: technology and innovation in building designs (51154). IEEE, Sakheer, Bahrain, pp 1–4

Albuquerque MHF, Delgado MJBL (2015) Sustainable museographies—the museum shops. Procedia Manuf 3:6414–6420

An L (2021) 融入可持续发展目标: 博物馆“重塑”的一个重要努力方向 [Integrating into the sustainable development goal: an important direction of the museum’s “reimagining”]. Southeast Cult. 2:10–15

Arenas JLG, Medina MFZ (2021) Re-imagining museums in a pandemic: new governance for a living, open and sustainable museum. Mus. Int 73(3–4):108–119

Ásványi K, Fehér Z, Jászberényi M (2021) The criteria framework for sustainable museum development. Tour. South East Eur. 6:39–51

Azmat F, Ferdous A, Rentschler R, Winston E (2018) Arts-based initiatives in museums: creating value for sustainable development. J. Bus. Res 85:386–395

Balocco C, Marmonti E (2012) Energy and sustainability in museums. The plant refurbishment of the medieval building of Palagio Di Parte Guelfa in Florence. Open J Energy Effic. 1(3):31–47

Barnes P, McPherson G (2019) Co-creating, co-producing and connecting: museum practice today. Curator Mus J. 62(2):257–267

Belfiore E, Bennett O (2007) Rethinking the social impacts of the arts. Int J Cult Policy 13(2):135–151

Benito B, Solana-Ibañez J, Enguix MDRM (2014) Efficiency in the provision of public municipal cultural facilities. Lex Localis J Local Self Gov 12(2):163–191

Benjawan K, Thoongsuwan A, Pavapanunkul S (2018) Innovation management model of world heritage city museum on historical park for creative tourism in the lower part of Northern Thailand. PSAKU Int J Interdiscip Res 7(1):110–120

Bertacchini EE, Nogare CD, Scuderi R (2018) Ownership, organization structure and public service provision: the case of museums. J Cult Econ 42(4):619–643

Bonner T (2019) Networking museums, older people, and communities: uncovering and sustaining strengths in aging. Innov Aging 3(Supplement_1):S362

Borowiecki KJ, Navarrete T (2016) Digitization of heritage collections as indicator of innovation. Econ Innov N Technol 26(3):227–246

Brophy SS, Wylie E (2013) The Green museum. A primer on environmental practise. Altamira Press, Lanham

Brown K (2019) Museums and local development: an introduction to museums, sustainability and well-being. Mus. Int 71(3-4):1–13

Camarero C, Garrido MJ, Vicente E, Redondo M (2019) Relationship marketing in museums: influence of managers and mode of governance. Public Manag Rev. 21(10):1369–1396

Cameron F (2022) Revisioning agenda 2030 and the sustainable development goals: museums and the promotion of diverse habitability practices for planetary futures. In: Proceedings of the UMAC-NATHIST-ICME-ICR 2022 joint annual conference “The Power of museums: sustainability”. ICOM UMAC-NATHIST-ICME-ICR, 86

Cerquetti M, Montella M (2021) Meeting sustainable development goals (SDGs) in museum evaluation systems. The case of the Italian national museum system (NMS). Sinerg Ital J Manag 39(1):125–147

Chaney D, Pulh M, Mencarelli R (2018) When the arts inspire businesses: museums as a heritage redefinition tool of brands. J Bus Res 85:452–458

Cheng H, Sun X, Xie J, Liu BJ, Xia L, Luo SJ, Tian X, Qiu X, Li W, Li Y (2024) Constructing and validating the museum product creativity measurement (MPCM): dimensions for creativity assessment of souvenir products in Chinese urban historical museums. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:280

Choi B, Kim J (2021) Changes and challenges in museum management after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Open Innov Technol Mark Complex 7(2):148

Daskalaki VV, Voutsa MC, Boutsouki C, Hatzithomas L (2020) Service quality, visitor satisfaction and future behavior in the museum sector. J Tour Herit Serv Mark 6(1):3–8

Di Pietro L, Mugion RG, Renzi MF, Toni M (2014) An audience-centric approach for museums sustainability. Sustainability 6(9):5745–5762

Dong Y (2008) The role of natural history museums in the promotion of sustainable development. Mus Int 60(1–2):20–28

Dragouni M, McCarthy D (2021) Museums as supportive workplaces: an empirical enquiry in the UK museum workforce. Mus Manag Curatorsh 36(5):485–503

Drochter R (2015) Measuring success in university museums: a case study at the Jurica Suchy nature museum. Northern Illinois University, Illinois

Durel JW (2009) Entrepreneurship in historical organizations. Hist N 64(2):20–25

Edwards D (2007) Corporate social responsibility of large urban museums: the contribution of volunteer programs. Tour Rev Int 11(2):167–174

Ennes M, Lee IN (2021) Distance learning in museums: a review of the literature. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn 22(3):162–187

Faheem F, Abduraheem K (2021) Energy management in museums: a new approach to implementing the sustainable development goals. IAR J Eng Technol 2(1):46–49

Ghoochani OM, Ghanian M, Khosravipour B, Crotts JC (2020) Sustainable tourism development performance in the wetland areas: a proposed composite index. Tour Rev 75(5):745–764

Gibson L (2008) In defense of instrumentality. Cult Trends 17:247–257

Giliberto F, Labadi S (2022) Harnessing cultural heritage for sustainable development: an analysis of three internationally funded projects in MENA countries. Int J Herit Stud 28(2):133–146

Grincheva N (2023) City museums in the age of datafication: could museums be meaningful sites of data practice in smart cities? Mus. Manag Curatorsh 38(4):367–393

Gustafsson C, Ijla A (2016) Museums: an incubator for sustainable social development and environmental protection. Int J Dev Sustain 5(9):446–462

Gustafsson C, Ijla A (2017) Museums—a catalyst for sustainable economic development in Sweden. Int J Innov Dev Policy Stud 5(2):1–14

Hadley S, Gray C (2017) Hyperinstrumentalism and cultural policy: means to an end or an end to meaning? Cult Trends 26:95–106

Hamdy A, Nagib S (2022) Virtual touring exhibition position in sustainable development strategy: applied to Egyptian dark stories. Int J Adv Stud World Archaeol 5(1):58–82

Han H, Hyun SS (2017) Key factors maximizing art museum visitors’ satisfaction, commitment, and post-purchase intentions. Asia Pac J Tour Res 22(8):834–849

Hansson P, Öhman J (2021) Museum education and sustainable development: a public pedagogy. Eur Educ Res J 21(3):469–483

Hebda RJ (2007) Museums, climate change and sustainability. Mus Manag Curatorsh 22(4):329–336

Henry C, Carter K (2021) Communicating climate change content in small and mid-sized museums: challenges and opportunities. J Mus Educ 46(3):321–333

Howaldt J, Hochgerner J, Franz HW (2012) Challenge social innovation: potentials for business, social entrepreneurship, welfare and civil society. Springer, Berlin

Huo Y, Miller D (2007) Satisfaction measurement of small tourism sector (museum): Samoa. Asia Pac J Tour Res 12(2):103–117

Jurčišinová K, Wilders ML, Visser J (2021) The future of blockbuster exhibitions after the COVID-19 crisis: the case of the Dutch museum sector. Mus Int 73(3-4):20–31

Kadoyama M (2018) Museums involving communities: authentic connections. Routledge, New York

Kershaw A, Bridson K, Parris MA (2018) The muse with a wandering eye: the influence of public value on coproduction in museums. Int J Cult Policy 26(3):344–364

Keršuliene V, Zavadskas EK, Turskis Z (2010) Selection of rational dispute resolution method by applying new step‐wise weight assessment ratio analysis (Swara). J Bus Econ Manag 11(2):243–258

Kowalska N, Ostręga A (2020) Using SERVQUAL method to assess tourist service quality by the example of the Silesian museum established on the post-mining area. Land 9(9):333

Lak A, Gheitasi M, Timothy DJ (2019) Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: cultural policies and strategic management. J Tour Cult Change 18(4):386–403

Lambert S, Henderson J (2011) The carbon footprint of museum loans: a pilot study at Amgueddfa Cymru—national museum wales. Mus. Manag Curatorsh 26(3):209–235

Larkin J (2016) All museums will become department stores’: the development and implications of retailing at museums and heritage sites. Archaeol Int 19(1):109–121

Lawan S, Yusuf UL (2021) Digital documentation of museum collections for sustainable development. J Soc Sci Adv 2(3):85–91

Literat I (2017) Facilitating creative participation and collaboration in online spaces: the impact of social and technological factors in enabling sustainable engagement. Digit Creat 28(2):73–88

Liu S (2021) 2021年国际博物馆日“恢复与重塑”主题的外部解读——兼谈博物馆践行可持续发展理念的国际趋势和中国方向 [Interpretation of the theme “recover and reimagine” for 2021 international museum day: discussion on the international trend and China”s approach to sustainable development in museums]. Palace Mus J 6:4–10+107

Loach K, Rowley J, Griffiths J (2017) Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of museums and libraries. Int J Cult Policy 23(2):186–198

Loddo M, Rosetti I, McGhie H, Pedersoli JL (2021) Empowering collections-based organizations to participate in agenda 2030: the “our collections matter toolkit”. Sustainability 13(24):13964

Long S (2013) Practicing civic engagement: making your museum into a community living room. J Mus Educ 38(2):141–153

Maher J, Clark J, Motley D (2011) Measuring museum service quality in relationship to visitor membership: the case of a children”s museum. Int J Arts Manag 13:29–42

Málaga LR, Brown K (2019) Museums as tools for sustainable community development: four archaeological museums in Northern Peru. Mus Int 71(3-4):60–75

Maniya K, Bhatt MG (2010) A selection of material using a novel type decision-making method: preference selection index method. Mater Des 31(4):1785–1789

Manna R, Palumbo R (2018) What makes a museum attractive to young people? Evidence from Italy. Int J Tour Res 20(4):508–517

Markovic S, Jankovic SR, Komšić J (2013) Museum service quality measurement using the HISTOQUAL model. In: Proceeding 2nd International scientific conference tourism in South East Europe

Markovska-Simoska S, Pop-Jordanov J, Pop-Jordanova N, Markovska N (2013) Organizational attention deficit as sustainability indicator: assessment and management. Industrija 41:75–89

McGhie H (2019) Museums and the sustainable development goals: a how-to guide for museums, galleries, the cultural sector and their partners. Curating Tomorrow, UK

McGhie H (2020) Evolving climate change policy and museums. Mus. Manag Curatorsh 35(6):653–662

McGhie H, Harrison R, Sterling C (2022) Museums and the Paris Agreement: reimagining museums for climate action. In: Proceedings of the UMAC-NATHIST-ICME-ICR 2022 joint annual Conference “The Power of museums: sustainability”. ICOM UMAC-NATHIST-ICME-ICR, 87

Mendoza HM, Talavera AS (2017) Museos y participación en destinos turísticos: dinámicas de sostenibilidad. RITUR-Rev Iberoam Tur 7:137–166

Merriman N (2008) Museum collections and sustainability. Cult Trends 17(1):3–21

Morgan J, Macdonald S (2020) De-growing museum collections for new heritage futures. Int J Herit Stud 26(1):56–70

Murphy O, Villaespesa E (2020) AI: a museum planning toolkit. Goldsmiths, University of London, London

Navarrete T (2020) Digitization in museums. In: Bille T, Mignosa A, Towse R (eds.) Teaching cultural economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, pp 204–213

Navarro JLA, Martínez MEA, Jiménez JAM (2019) An approach to measuring sustainable tourism at the local level in Europe. Curr Issues Tour 23(4):423–437

Neupane R (2016) Effects of sustainable tourism on sustainable community development in coastal regions in the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Sci Manag 3(1):47–59

OECD (2003) OECD environmental indicators: development measurement and use. OECD, Paris

Papadamou T, Gavrilakis C, Tsolakidis C, Liarakou G (2010) Education for sustainable development through the use of the second life: the case of a virtual museum for sharks. In: Lytras MD, Ordonez De Pablos P, Avison D, Sipior J, Jin Q, Leal W, Uden L, Thomas M, Cervai S, Horner D (eds.) Technology enhanced learning Quality of teaching and educational reform. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 316–323

Pencarelli T, Cerquetti M, Splendiani S (2016) The sustainable management of museums: an Italian perspective. Tour Hosp Manag 22(1):29–46

Plaza B, Haarich SN (2013) The Guggenheim museum Bilbao: between regional embeddedness and global networking. Eur Plan Stud 23(8):1456–1475

Pop IL, Borza A (2015) Sustainable museums for sustainable development. Adv Bus Relat Sci Res J 6(2):119–131

Pop IL, Borza A (2016) Technological innovations in museums as a source of competitive advantage. In: Oprean C, Tîtu MA (eds) Proceedings of the 2nd international scientific conference samro 2016: news, challenges and trends in management of knowledge-based organizations. Editura Tehnică, Bucharest, Romania, pp 398–405

Pop IL, Borza A, Buiga A, Ighian D, Toader R (2019) Achieving cultural sustainability in museums: a step toward sustainable development. Sustainability 11(4):970

Pop IL, Hahn RF, Radulescu CM (2018) Sustainable development as a source of competitive advantiage: an empirical research study in museums. UTMS J Econ. 9(1):73–83

Preuss U (2016) Sustainable digitalization of cultural heritage—report on initiatives and projects in Brandenburg, Germany. Sustainability 8(9):891

Prottas N (2021) Museum education in a time of crises. J Mus Educ 46(4):399–401

Rapport D, Friend A (1979) Towards a comprehensive framework for environmental statistics: a stress-response approach. Projet d”etablissement d”un systeme general d”information sur l”environnement au Canada. Minister of Supply and Services, Canada

Rentschler R, Gilmore A (2002) Museums: discovering services marketing. Int J Arts Manag 5(1):62–72

Reussner EM (2003) Strategic management for visitor-oriented museums. Int J Cult Policy 9(1):95–108

Rivero P, Navarro-Neri I, García-Ceballos S, Aso B (2020) Spanish archaeological museums during COVID-19 (2020): an edu-communicative analysis of their activity on Twitter through the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 12(19):8224

Samis P, Michaelson M (2017) Creating the visitor-centered museum. Routledge, New York

Schaltegger S, Wagner M (2011) Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus Strategy Environ 20(4):222–237

Senapati T, Yager RR (2020) Fermatean fuzzy sets. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 11(2):663–674

Sharif-Askari H, Abu-Hijleh B (2018) Review of museums’ indoor environment conditions studies and guidelines and their impact on the museums’ artifacts and energy consumption. Build Environ 143:186–195

Sobocińska M (2019) The role of marketing in cultural institutions in the context of assumptions of sustainable development concept—a polish case study. Sustainability 11(11):3188

Stević Ž, Pamučar D, Puška A, Chatterjee P (2020) Sustainable supplier selection in healthcare industries using a new MCDM method: measurement of alternatives and ranking according to COmpromise solution (MARCOS). Comput Ind Eng 140:106231

Stylianou-Lambert T, Boukas N, Christodoulou-Yerali M (2014) Museums and cultural sustainability: stakeholders, forces, and cultural policies. Int J Cult Policy 20(5):566–587

Sutter GC (2008) Promoting sustainability: audience and curatorial perspectives on the human factor. Curator Mus J 51(2):187–202

Sutter GC, Sperlich T, Worts D, Rivard R, Teather L (2016) Fostering cultures of sustainability through community-engaged museums: the history and re-emergence of ecomuseums in Canada and the USA. Sustainability 8(12):1310

Sutton S (2020) The evolving responsibility of museum work in the time of climate change. Mus Manag Curatorsh 35(6):618–635

Swarbrooke J (2015) Built attractions and sustainability. In: Hall CM, Gossling S, Scott D (eds) The Routledge handbook of tourism and sustainability. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 356–364

Tsai PH, Lin CT (2018) How should national museums create competitive advantage following changes in the global economic environment? Sustainability 10(10):3749

Valtysson B, Nilsson SL, Pedersen CE (2021) Reaching out to be in reach. Museum communication in the current museum zeitgeist. Nord Mus 31(1):8

Villaespesa E, Murphy O (2021) This is not an apple! Benefits and challenges of applying computer vision to museum collections. Mus Manag Curatorsh 36(4):362–383

Villeneuve P (2013) Building museum sustainability through visitor-centered exhibition practises. Int J Incl Mus 5(4):37–50

Wang YC, Chiou SC (2018) An analysis of the sustainable development of environmental education provided by museums. Sustainability 10(11):4054

Weil SE (2007) Beyond big and awesome: outcome-based evaluation. In: Sandell R, Janes RR (eds.) Museum management and marketing. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 214–223

Worts D (1998) On museums, culture and sustainable development. In: Ferera L (ed.) Museums and sustainable communities: Canadian perspectives. ICOM Canada, Québec, pp 21–27

Zbuchea A, Bira M (2020) Does stakeholder management contribute to a museum’s sustainable development? Manag Dyn Knowl Econ 8(1):95–107

Zhang H, Xu F, Lu L, Yu P (2017) The spatial agglomeration of museums, a case study in London. J Herit Tour 12(2):172–190

Zollinger R (2021) Being for somebody: museum inclusion during COVID-19. Art Educ 74(4):10–12

Zollinger R, DiCindio C (2021) Community ecology: museum education and the digital divide during and after COVID-19. J Mus Educ 46(4):481–492

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the assistance provided by Zhejiang Natural History Museum. This study includes valuable contributions from Hongming Yan, Guoying Lan, Laishun An, Shouyong Pan, Mingbin Li, Yang Huang, Hanze Song.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Siyi Wang: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision, Review & editing. Liying Yu: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Review & editing. Yuan Rong: Writing-original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This research is conducted as part of the research program supported by the China Center for International People-to-People Exchange, Ministry of Education. The study has undergone examination and supervision by the Ethical Committee of Shanghai University. It has been granted approval under the reference number 2023WHLY1034.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the data was collected. We informed each participant of their rights, the purpose of the study, and to safeguard their personal information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendix

Appendix

The relevant supporting materials (including the list of interviewees, interview outlines, questionnaires, the theory of Fermatean fuzzy set, methodology and computational results) can be consulted at the following link: https://1drv.ms/b/s!Aua4yTnLwBN-gY1GOCZ0Dj_ALiaSSw?e=fFFSSl.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Yu, L. & Rong, Y. Measuring museum sustainability in China: a DSR model-driven approach to empower sustainable development goals (SDGs). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 982 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03437-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03437-z