Abstract

Compulsory schooling laws are commonly believed to be effective measures in ensuring individuals benefit from education. However, their implications for racial equality are less-apparent. Exploiting timing and geographic variation in legislation reforms among Southern U.S. states, this study evaluates the differential impact of minimum school-leaving age requirements on short- and long-term labor market outcomes between Black and White men. Results show that each additional year of compulsory schooling produces about 7.3–8.2% increase in adulthood weekly income. While there exists a substantial gap in returns to education between Black and White men at early career stages, this gap is reduced by 37 percentage points at mid-late career. Findings imply that mandating compulsory school attendance motivates both Black and White men to stay in school longer, and thus reducing racial gaps in returns to education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compulsory Schooling Laws (CSL) are mandatory school attendance arrangements that specify a legal entry and dropout age during which children within a certain jurisdiction must unconditionally attend school, and such legislation has been virtually universal among developed countries for more than a century (OECD 2011). In the United States, CSL first emerged with Massachusetts’s An Act concerning the Attendance of Children at School enacted in 1852, and began to expand to other Northern states before end of the 19th century (Ensign 1921). The first CSL legislation in Southern states, however, did not exist until it was passed in the state of Kentucky in 1896 (Sansani 2015). While a common rationale in the early stages of CSL adoption in the North was nation-building with legislatures citing needs to assimilate children with foreign-born parents (Provasnik 2006), CSL advocates in the South believed that mandatory schooling would extend learning opportunities to educationally-deprived Black students (Dabney 1936). Relatedly, another key draw for implementing CSL in the South was to discourage youth from engaging in unlawful conduct outside of school (Redcay 1935). By the mid-20th century, all 50 U.S. states had enacted CSL, and devoted considerable public resources in introducing, maintaining, and promoting its legal enforcement (Katz 1976). In this regard, prior studies have shown that introduction of CSL legislation mandating school attendance contributed to the rapid bureaucratization and industrialization of state-level education systems in the early 20th century (Meyer et al. 1979), and explains a significant portion of America’s rise in human capital and economic development during the second half of the 20th century (Goldin 1998).

More recently, policy discussions on CSL continue to attract public attention in the United States, particularly in the context of extending required years of school attendance and discouraging early dropouts (Oreopoulos 2007; Landis and Reschly 2011). For instance, in 2012, President Obama’s political platform fielded calls to action for states to expand CSL and make school attendance mandatory up to 18-years-old (Rauscher 2014). In this regard, substantial research interests have centered on the short-term effects of CSL (Stephens and Yang 2014), yet very little is known about the long-term career benefits and the social equity implications that vouch support for such legislation. For instance, studies have shown that when students are obligated to stay in school longer, they benefit by completing high school (Greene and Jacobs 1992; Bell et al. 2016), attending college (Oreopoulos et al. 2006), becoming more productive in the workplace (Lang and Kropp 1986), and earning more wages in the labor market (Margo and Finegan 1996; Lleras-Muney 2002). However, little is known about whether this effect is persistently strong in the longer time horizon (Lleras-Muney and Shertzer 2015), nor do studies indicate clear evidence if additional CSL mandated years of schooling is beneficial in closing racial gaps in returns to education (Raudenbush and Eschmann 2015).

As indicated by an expansive body of literature in economics of education, returns to education is a decisive parameter affecting individual and family investment decisions to pursue more education, in addition to persuading governmental policy actions to intervene in educational affairs (Psacharopoulos and Patrinos 2018). Even for those studies that do examine the extended effects of CSL on returns to education (see Angrist and Krueger 1991; Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011), controversies over methodology, context, and implications still generate considerable pondering among academic and policy research circles (Clay et al. 2021). In this regard, critical policy questions remain as to whether expansion of CSL increased educational attainment for those affected, and if so, for whom and by how much, and whether such positive effects are sizable enough to benefit traditionally disadvantaged Black students.

Particularly, race-based inequality in educational attainment and its related outcomes have continued to present themselves as among the most important social problems facing the United States (Merolla and Jackson 2019). Scholars have argued that access, demand, and attainment of education is a key mechanism through which individuals are sorted into positions of relative advantage and disadvantage, and therefore schools become key reproduction sites of race-based social inequalities. More importantly, these questions matter not only from a policy evaluation standpoint, but is considered valuable experience relevant for a wide range of countries that is assessing the potential social and individual implications of CSL expansion (Akbulut-Yuksel 2017).

This study leverages a “natural experiment” in the expansion episode of CSL legislation that occurred in post-WWII United States, which resulted in policy-induced variation in minimum legal school-leaving age requirements among Southern states. More specifically, the Southern U.S. states of Georgia (GA), Louisiana (LA), Missouri (MO), and North Carolina (NC) passed CSL reform legislation that changed minimum legal school-leaving age from 14 years-old to 16 years-old in 1946, while maintaining school-starting age at 7 years-old. Exploiting timing and geographic variation in new CSL requirements generated by the aforementioned policy change, this study contributes directly to the literature on CSL and returns to education, as well as adding new evidence to studies that examine effective educational reforms addressing racial income gaps. This study combines difference-in-differences (D-i-D) and instrumental variable (IV) research designs to address validity concerns. To this end, this study addresses weak instrument issues in Angrist and Krueger’s (1991) instrumental variable strategy, attempts to capture variation generated by moment of CSL policy change (Oreopoulos 2006), and avoids geographical variability and regional characteristic concerns that may confound effects of CSL expansion (Lleras-Muney 2005).

In practical terms, while the D-i-D design is useful in estimating the average treatment effect (ATE) of CSL expansion, adopting an instrumented D-i-D design facilitates the detection of its local average treatment effect (LATE), which is the variation in outcome that is attributable to individuals who are affected by the precise moment of CSL legislative expansion. Combining both approaches, this study is positioned to better understand the effect of new CSL legislation not only for those individuals who reside in states that expanded school attendance policies, but more specifically those individuals whose educational attainment increased as result of state-initiated CSL policy expansion. Integrating previously independent bodies of literature on CSL, returns to education, and racial equality in education, this study attempts to address the following research questions:

(1) What are the effects of CSL legislation on educational attainment?

(2) What are the short- and long-term effects of CSL legislation on returns to schooling?

(3) How does CSL effects on returns to schooling differ between Blacks and Whites, and what drives such heterogeneity?

Policy context

In U.S. education policy and legislation research, one area of scholarly interest has been on addressing the persistence of educational inequality between Blacks and Whites and its associated social disparity consequences (Hallinan 2001; Card and Rothstein 2007). Although there still persist substantial differences between Blacks and Whites in schooling-terms today, such imbalance was much more pronounced in the early 20th Century. With historical roots that predate the founding of the nation, racial inequality in education has attracted widespread attention, and researchers have commonly identified schooling as an important mechanism for reducing such gaps and improving life outcomes (Fryer and Dobie 2014; Reardon et al. 2019; Chetty et al. 2020). One important hypothesis under this view is that marginal returns to attending each additional year of school is substantively higher for students who are from groups that are traditionally marginalized and deprived of learning opportunities (Barrow and Rouse 2005). Notwithstanding, studies also show that de facto economic and social barriers that exist in Southern U.S. states have limited Black students from fully benefitting from such educational opportunities (Anderson 1988; Hallinan 2001). Therefore, while debates on CSL commonly agree on the overall benefits of requiring lengthier schooling, the educational equality aspect of mandatory public education remains more or less controversial to date (Reyes 2020). Consequently, examining CSL policies during this era can provide useful insights on how educational legislative reforms may have equalizing effects on racial disparities in terms of increasing access, demand, and attainment of education.

On the one hand, historical studies have identified CSL expansion policy decision commonly as a functional response to population growth (Meyer et al. 1977), immigration influx (Meyer et al. 1979), industrialization and urbanization movements (Baker 1999; Baker 2014). Scholars in this camp hold skeptical views towards the equalizing effects of CSL, and many believe that the CSL movement, in broad strokes, represents an institutionalized effort to replicate racially segregated social rules governing Black children and families through the enforcement of mandatory schooling (Tyack 1976). In this regard, Black-White inequality in educational access, quality, and outcomes could well-mirror systemic racism that already exist in the society at-large, and school’s ability to mitigate such disparity is considered questionable (Oakes 1985; Rothstein 2004; Giersch 2018). Other scholars voice even more pessimistic concerns, such that mandatory schooling does not lead to learning opportunities, because differential tracking and grade repetition likelihoods often mimic reproduction of social structures and income inequalities, which are often overlapped with racial and ethnic background (see Bowles and Gintis 1976; Massey and Denton 1993; Fisher et al. 1996).

On the other hand, more recent investigations have attempted to identify CSL’s positive role in ensuring mass education and how it de-stratifies learning opportunities for children from different racial and wealth backgrounds (Walters 2001; Steffes 2012; Raudenbush and Eschmann 2015). Scholars find that CSL can be effective if it extends learning opportunities to minority and low-income students who would have dropped out of school in the absence of such minimum school-leaving age enforcement under CSL (Oreopoulos 2007). The implicit assumption is that CSL expansion requires students from disadvantaged backgrounds to stay in school longer, and subsequently ensuring that such otherwise marginalized groups benefit from accumulating more human capital under extended CSL arrangements (Goldin and Katz 2008). In this regard, prior studies have commonly identified two nationwide waves of CSL expansion movement, with the first wave occurring pre-1910s and focusing on mandating primary school attendance, and a second wave taking place post-1910s, which increased minimum school leaving age to cover middle and high school attendance (Stephens and Yang 2014). While most studies focus on the first pre-1910s wave leveraging CSL expansion’s first stage effect on primary enrolment, research investigating the post-1910s wave is relatively scarce.

In broad terms, studies examining CSL have traditionally utilized two main empirical strategies, which are timing of birth and geographic variation, in the identification of causal effects of CSL on students’ labor market outcomes. In the first cluster of studies, Angrist and Krueger (1991) leverage students’ quarter of birth as instrumental variable for determining those who were affected by CSL requirements, and compare educational attainment and labor wage outcomes by state and cohort. Margo and Finegan (1996) utilize information on students’ month of birth and adopt similar comparison to detect effects of CSL on earnings. Despite these influential early studies, subsequent research examining their methodological merits has voiced concerns regarding this approach since timing of birth is shown to have a weak first-stage correlation with educational attainment, and can be influenced by birth-planning practices that are associated with higher parental socioeconomic status (see Bound and Jaeger 2000; Cruz and Moreira 2005; Buckles and Hungerman 2013).

Among the second research cluster, Acemoglu and Angrist (2000), Leras-Muney (2002), Goldin and Katz (2008), Stephens and Yang (2014), Lleras-Muney and Shertzer (2015), and Clay et al. (2021) leverage CSL requirements that vary by state and over time to investigate its potential consequences on students. However, research on CSL in Southern U.S. states during the second wave of CSL expansion is particularly lacking. Yet, the need to fill this void is critical, at least for the following reasons. First, CSL expansion emerged first in the Northern states, while Southern states adopted such legislation much later (Rauscher 2014). Second, previous studies have indicated that school quality reforms coincided with the CSL movement in the South, and this relatively rapid school quality improvement suggests that the influence of schools may be more salient and this may represent an important explanation for better adulthood outcomes in the South (Card and Krueger 1992). Third, other in-school interventions common to most Southern states, such as the eradication of hookworm and other health and nutrition interventions, improved learning outcomes significantly during this period (Bleakley 2007). Fourth, the Rosenwald school movement in Southern states during the early-to-mid 20th century had significant effects on improving school attainment and learning outcomes among Southern Blacks particularly in rural areas (Aaronson and Mazumder 2011). These important contextual factors, in addition to geography, demographics, and culture, that vary between Northern and Southern states are reasonably expected to influence the external validity of prior studies.

In mapping and tracking the second wave of CSL reform movement among Southern U.S. states, this study adopts similar measures used in Acemoglu and Angrist (2000) and Stephens and Yang (2014), by tracking state-specific legal statues that mandate the minimum age individuals needs remain in school without making any exceptions. Matching this information with historical records from U.S. Department of Labor (1946) and (1949), four Southern states are identified: Georgia (GA), Louisiana (LA), Missouri (MO), and North Carolina (NC), which increased their minimum legal school-leaving age from 14 to 16 years-old in 1945. In particular, these state-specific CSL are respectively Georgia Laws 194 Act 350 Secs. 1-4/10., Louisiana Sum. Supp. Secs. 2355.1 to 2355.3/2355.10., Missouri Rev. Stats. Secs. 10587/10541/10546/10593, and North Carolina Stats. Sec. 115-302, as amended by Laws 1945 Ch. 826.

While a variety of social forces at the state-level are arguably responsible for passing these legislations that compel students to stay in schools longer, academic inquiry into these historical events is scarce. In limited accounts, scholars tend to believe this lagged episode of policy catch-up on CSL among Southern States is partially explained by tightening enforcement of the Federal child labor laws during the early 1940s (Congressional Research Service 2013), as well as Southern states policy intention to expand public schooling in the post-WWI era (Anderson 1988). To this end, observations elsewhere also suggest an economic benefit argument for CSL expansion is commonly rationalized in policy circles (Halsey, Heath and Ridge 1980), particularly through the accumulation of skills and improved labor productivity by attending school longer (Bernbaum 1967).

Research design

This study focuses on four Southern U.S. states that had increased minimum school-leaving age from 14 years-old to 16 years-old, and construct a difference-in-difference (D-i-D) comparison between these four “treatment” states and geographically adjacent “control” states whose legal schooling age requirements remained constant at 16 years-old. In more concrete terms, the difference in adulthood labor market outcomes between students who were affected by CSL changes and those who were not affected in these four states is benchmarked against the difference observed for similar students in adjacent control states that did not implement CSL reform. In doing so, the D-i-D estimator nets out any potential pre-reform heterogenous confounder between treatment and control states, such that only the change in differences in outcome is attributed to CSL reform.

Operationally, the first dimension of the D-i-D estimation utilizes students’ state-of-birth information. Treatment states are four U.S. Southern states (GA, LA, MO, and NC) that had implemented CSL expansion. The control states come from a pool of states that maintained an unchanged minimum school-leaving age at 16, and is further limited to nine states that share at least one state border with the treatment states. The resulting control subset sample includes the states of Alabama (AL), Arkansas (AK), Florida (FL), Illinois (IL), Iowa (IA), Kansas (KS), Kentucky (KY), South Carolina (SC), and Texas (TX). A map detailing the list of treatment and control states is presented in Fig. 1. The regional proximities and demographic similarities among the treatment and the control states strengthen parallel trends assumption across states. Notwithstanding, while the D-i-D attempts to partition and difference out confounding factors between treatment and control states, there may still be concerns that the control states of IA, IL, and KS are not considered traditionally southern states, which may limit credibility of results. Therefore, robustness checks is conducted by excluding these three non-southern control states in a follow-up analysis.

To examine how CSL reforms in treatment states of GA, LA, MO, and NC influenced educational attainment, this study utilizes 1960 Census information and plot a graph showing the first-stage effects of CSL on years of education for individuals born between 1910 and 1950, as shown in Fig. 2. The bold line is the trendline for treatment states and the dash-dotted line is for control states. For both groups, the average years of education increase steadily for younger cohorts in a somewhat parallel upward fashion for those born between 1920 and 1940. However, there is a noticeable break in the parallel trend for individuals born in 1932 and 1933, such that the average years of education for those in treatment states experienced a sharper increase. For comparison, there is only a moderate increase in the average years of education is observed in the control states for those born in 1932 and 1933 respectively.

In retrospect, this break in parallel trend between the treatment and the control states corresponds to the CSL reforms that occurred in these treatment states during 1946. Specifically, students born in 1932 in treatment states are supposedly 14 years of age in 1946, which were unaffected by CSL reforms and were only legally required to stay in school until 14. However, for those students born in or after 1933 in treatment states, new CSL legislation requirements would legally require them to stay in school for two additional years until they turn 16 years-old. The observational evidence presented in Fig. 2 suggests that CSL legislative reforms in treatment states are effective at increasing the enrolment and educational attainment of at least some students, and confirm presence of a non-zero first-stage effect, which is indicated by the positive correlation between CSL reform on educational attainment, for those born after 1933 in treatment states.

Since the CSL legislative reform episode in treatment states is targeted at under-14-year-old cohorts who would be subject to additional school attendance requirements, the instrumented D-i-D design in this study in effect conceptualizes changes in CSL legislation as a haphazard encouragement targeted at a subpopulation towards faster uptake of legal schooling requirements. Combining both instrumental variable and difference-in-differences, the analytic design is positioned to better understand the effect of new CSL legislation not only for those individuals who reside in states that increased legal CSL requirements, but more specifically how mid- and long-term career outcomes varied for those individuals whose educational attainment increased as result of CSL expansion in these treatment states.

To operationalize the instrumented D-i-D analysis, an interaction term is constructed to indicate whether an individual was subject to heightened CSL legal requirements, and subsequently estimate its influence on educational attainment and labor earnings. The first dimension of this interaction term is whether an individual was born in one of four treatment states, and the second dimension is whether an individual was born in birth cohorts that are subject to new CSL age-requirements. In detail, the first factor of this interaction term indicates individuals’ state-of-birth, denoted as \({{TreatmentState}}_{j}\). Individuals born in treatment states are assigned 1 for this binary variable, and those born in control states are assigned 0. The second factor of the interaction term reflects individuals’ year-of-birth, denoted as \({{Affected}}_{k}\). Individuals born in and after 1933 are assigned 1 for this binary variable, and those born prior to 1933 are assigned 0. As a result, the interaction term (\({{TreatmentState}}_{j}* {{Affected}}_{k}\)) takes the value of 1 if the individuals are subject to CSL reform in treatment states, and assigned 0 if otherwise. Analytically, this study evaluates the influence of CSL on educational attainment and labor income using Two Stage Least Squares (TSLS) regression, which takes the following form:

In the first stage, as denoted Eq. (1), the model estimates the effect of being subjected to CSL reform on the endogenous variable educational attainment, \({{Edu}}_{{ijk}}\), for individual i born in state j in year k. The analysis also includes a set of covariates \({X}_{{ijk}}\), including race, marital status, and location of residence, as well as age and age-squared. In the second stage, as denoted Eq. (2), the model defines the outcome of interest as individual i’s log weekly wages and regress that on the predicted values of educational attainment, \({\widehat{{Ed}}u}_{{ijk}}\). Following Liu (2021) and Liu and Xie (2021), this study uses weekly earnings information, as opposed to annual, monthly, or hourly wages primarily to avoid the comparability issue stemming from differences in the number of work weeks and mismeasurement issues regarding at-home work. Wage information from the 1960 Census and the 1980 Census to estimate both the short-term income effects, at median age 28, and the long-term effects at median age 48.

In addition, to test for model robustness, the TSLS regression is conducted on two birth cohort bandwidths: 2-year bandwidth (1932–1933) and 10-year bandwidth (1928–1937). In this regard, different age cohort bandwidths allow varying sample sizes and different degrees of stringency in the parallel trend assumption between treatment and control states. More importantly, this study attempts to detect heterogeneous economic consequences of CSL by stratifying Blacks and Whites in the analytic sample. To this end, previous studies have found consistently lower returns to additional year of schooling for Black students (Welch 1973; Card and Krueger 1992). The present analysis is concerned with whether this lower return is consistent throughout the professional career.

Data

This study uses census data from the 1960 and the 1980 United States Decennial Census obtained from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) database. The 1960 and 1980 IPUMS data files contain demographic records sampling one percent of all U.S. households, and are surveyed and collected by the U.S. Census Bureau (Ruggles et al. 2021). The U.S. Census dataset is considered one of the most comprehensive and reputable high-quality national representative datasets that allows for historical individual-level outcomes analysis (Kugler and Fitch 2018). More specifically, the 1960 and 1980 U.S. Census were conducted in April of 1960 and 1980 respectively, and enumerating approximately 98 percent of the population of the United States, from which public use one percent dataset is derived using a 1-in-100 national random sample of the respondent population (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1963; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1983). In terms of sampling errors, IPUMS (2021) report design factors close to 1.0 or lower for most variables collected in the 1960 and 1980 census, suggesting the ratio of observed standard errors to random sample standard errors is estimated to be within acceptable range.

Following analytic decisions adopted in prior studies for comparability purposes (see Angrist and Krueger 1991; Oreopoulous 2007; Clay et al. 2021), this study elects to focus exclusively on male respondents’ weekly wages as the outcome variable. While this decision is not basis for undermining the importance of studying the effect of CSL across gender categories, key rationales for such analytic design includes reducing self-selection bias stemming from non-random response rate and selective labor force participation common to female respondents during this historical period (Cano-Urbina and Lochner 2019). Omitting female earnings information in this analysis is a key limitation, but it remains a critical area to be addressed in a future planned study.

To mitigate outlier effects and minimize the influence of data input error, a standard 1-percent winsorizing procedure is applied to all earnings information, such that the top and bottom 1-percent of wage information was replaced with values at the 99th and 1st percentiles, respectively. This study restricts age cohorts to those who were born between 1928 and 1937, and the geography of the sample to only treatment and control states. To the extent possible, limiting the analysis to ten birth cohorts and thirteen states reduces the noise and preserves the parallel trends assumption between treatment and control states.

Table 1 presents summary statistics of key variables used in analysis. The columns report means separately by control and treatment states, and by unaffected and affected birth cohorts. The key outcome variables are log weekly wages and educational attainment, and the list of background covariates includes individuals’ race, marital status, and location of residence. In the final column, a crude difference-in-difference (D-i-D) calculation is presented, and several observations can be made. First, while the CSL reform episode did not impact average labor earnings directly as shown by the statistically insignificant D-i-D estimators for both 1960 and 1980 Census, it does provide assuring evidence that the exclusion restriction of TSLS regression is satisfied. Second, the non-zero first-stage effect assumption in the TSLS regression is satisfied, since the CSL reform in treatment states increased average educational attainment for affected cohorts by 0.2 years (p < 0.05), showing a positively correlated first-stage relationship. Third, consistently insignificant D-i-D estimators for all individual background covariates suggest there is no systematic difference between those in unaffected and affected cohorts in control and treatment states. This is likely assuring evidence that the D-i-D design successfully differenced out potentially confounding background factors between treatment and control states.

Results

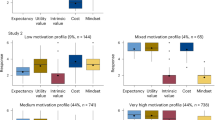

This study is interested in both the short- and long-term effects of CSL legislation on returns to each additional year of education. Therefore, detailed results from TSLS regression are provided in Table 2, where columns (1) and (3) correspond to the 2-year cohort bandwidth analysis findings, and columns (2) and (4) illustrate that of the 10-year cohort bandwidth analysis. Regardless of choice of bandwidth, there are consistent and significant results for both short- and long-term returns to each additional year of compulsory schooling, approximately at about 7.3 percent and 8.2 percent for 2-year and 10-year cohort bandwidths respectively using 1960 census data, and 7.3 percent and 7.5 percent for 2-year and 10-year cohort bandwidths respectively using 1980 census data. This finding indicates that returns to each additional year of CSL-induced education is evaluated at approximately 8 percent, but also seems to suggest that it plateaus at early labor market entry, since rate of return estimates only differing marginally at median age 28 as compared to median age 48.

Importantly, it is worth mentioning that consistently significant F-statistics larger than 10 across all columns confirm that the non-zero first-stage effect assumption of TSLS is satisfied. In sum, while coefficient estimates do not differ qualitatively depending on which cohort bandwidths is chosen, it is observed that the 10-year cohort bandwidth has consistently resulted in larger sample sizes and coefficients of determination (R-squared), while standard errors are arguably lower compared to the 2-year cohort bandwidth. These statistics suggest better model fit using the 10-year cohort bandwidth, which is basis for subsequent analyses.

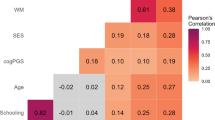

Next, the analysis examines the differential rates of return between Black and White men, by utilizing a split-sample approach in which all models are kept interpretationally identical and that all coefficients are allowed to differ between Whites and Blacks. Table 3 presents point estimates on the return to an additional year of educational attainment using TSLS regression with 10-year cohort bandwidth, and results are reported by Whites and Blacks and for short- and long-term respectively in each column.

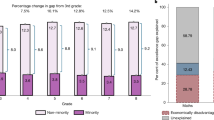

In Table 3 columns (1) and (2), results indicate that every additional year of education affected by CSL increases short-term earnings at median age 28, by 8.4 percent for White males, but only 3.8 percent for Black males. In other words, returns to education at early labor market entry for Blacks is approximately 55 percent less than that of Whites. As for long-term effects at median age 48, shown in Table 3 columns (3) and (4), each additional year of CSL-induced education increases labor wages for Whites by 7.6 percent and 6.3 percent for Blacks, which translates to an 18 percent racial gap in returns to education. Overall, findings suggest that early racial gaps in returns to education are substantial, but in the long run, this gap is reduced by 37 percentage points from 55 percent to 18 percent, although differences do not fully even out.

As additional robustness check in Table 4, the analysis is replicated on a subsample of individuals excluding those who were born in control states: IA, IL, KS. This is based on the concern that the control states of IA, IL, and KS are not considered traditional southern states, and may confound results due to having distinct demographic, cultural and historical differences. Results do not indicate systematic differences in point estimates for returns to education, although they are reduced somewhat for White men.

In Table 5, separate OLS regression analyses are conducted for different educational attainment outcomes, for both the full sample and by racial subgroup. For one, this analytic step acts as robustness check for testing the instrumental variable’s (IV) exclusion restriction assumption. For another, examining IV’s relationship with different educational attainment outcomes provides insights on the potential mechanisms through which CSL reforms affects individuals. In any case, full sample results show that being affected by CSL reform in treatment states is positively correlated with both overall educational attainment (Table 5, row 1) and high school completion (Table 5, row 2), but poorly predicts university/college attendance and completion (Table 5, rows 3 and 4). In more detail for the racial subgroup analysis, results indicate that the IV is not correlated with educational attainment for Whites, but it positively predicts high school completion. For Blacks, the opposite is true, such that the IV is positively correlated with overall educational attainment, yet it does not predict high school completion. Jointly, these findings suggest that the effect of CSL acts through two very different channels for Black and White men. On the one hand, CSL reforms pushes Whites who are subject to increased minimum school-leaving age to complete high school, yet it does not improve average educational attainment for Whites. On the other hand, CSL reforms improves overall educational attainment among Blacks, who are not necessarily compelled by new mandatory CSL legislation to complete high school.

Finally, further robustness checks on TSLS’s exclusion restriction show that the IV is uncorrelated with both labor market outcomes and background characteristics (see Table 6). In detail, the IV is regressed on several labor market outcomes and background characteristics, and show no statistically significant relationship. Therefore, results in Table 6 affirm IV’s path of effect, by showing CSL reforms only affect earnings through influencing individuals’ educational attainment, further suggesting the IV’s exclusion restriction assumption holds true.

Conclusion and discussion

Differences in timing of CSL reforms among four Southern states in the United States create an interesting episode in education legislation change. Prior studies have either overlooked this CSL reform period in the American South, or have only focused on the average short-term effects without due attention on racial differences. This study contributes new evidence and fill a void in the literature by constructing a D-i-D comparison between four treatment states and nine geographically adjacent control states. Operationally, this study instrumentalizes the interaction between individuals’ year-of-birth and state-of-birth to represent whether students were subject to new CSL requirements. In terms of robustness checks on results, relationships between the instrumental variable and various educational outcomes and background characteristics are assessed. It can be concluded that the CSL reforms had affected future earnings only through influencing individuals’ educational attainment. Notwithstanding, for comparability purposes and due to data limitation, this study elected to focus on Black and White men only, and the design had assumed that CSL enforcement was similar across race.

In broad strokes, this study quantifies the critical influence that CSL has on individuals, and identifies different channels through which heterogeneous effects by racial group is realized. Considering the large number of individuals affected by these law changes, estimates on potential gains represent substantial individual and societal benefits for states that implemented CSL reform. In further detail, the main findings are the following. First, CSL reforms in the American South that aimed at increasing minimum school-leaving age from 14 to 16 years-old resulted in approximately 0.2 years rise in average educational attainment for individuals affected by new legislations in treatment states, but it did not impact adulthood labor earnings directly. Second, it is estimated that each additional year of compulsory education elicited by CSL reform in treatment states increases individuals’ average weekly income by 7.3 to 8.2 percent, with returns plateauing at early labor market entry. Third, there is a substantial heterogeneity in returns to education between Blacks and Whites during early stages of career, but the gap tends to close at mid-late career. Fourth, a main channel through which CSL reforms affects labor market outcomes is by increasing educational attainment, particularly high school attendance and completion for White men, but it has little effect on university/college attendance and completion. Fifth, CSL reforms improves educational attainment for Blacks and Whites differently, such that Whites are more likely to be compelled to graduate high school, whereas Blacks are more likely to attend school longer but not more so completing high school.

Importantly, while pecuniary factors consist only one dimension of social life, economic marginalization is one key channel through which the adverse effects of structural racism are compounded intergenerationally (Bishop-Royse et al. 2021). Existing studies have shown that race-based income inequality matters for wide-ranging social outcomes in the United States, where persistent differences exist across racial groups in employment, homeownership, police arrests, life expectancy, and a range of health outcomes, and that race-based income inequality levies an increasingly significant role in shaping race-based social mobility, and that access to services and opportunities substantially differ between Blacks and Whites (Akee et al. 2019). To this end, income, race, and class are three closely inter-linked and intertwined factors affecting individual wellbeing. Classical sociology has defined class within the Marxist tradition as common position within the social relations of production, which can mediate racial differences in pecuniary returns to education. While the present study does not directly show how CSL expansion or educational attainment relates to racial class mobility differences, new evidence on income inequality point to the cyclical effect of racial differences in returns to education and distribution of racial groups into class categories as key determinants of race-based inequality at large (Pfeffer et al. 2020).

Taken as a whole, findings in this study suggest that expanding CSL benefits both Black and White students by requiring entire cohorts to stay in school longer, and as consequence, racial gap in returns to education is shown to close in the long run. A key explanation for this finding is that CSL legislation are often result direct enforcement and policing of school attendance. For instance, Angrist and Krueger (1991) observes that most states hire truant officers to administer and enforce CSL requirements, who often are permitted with wide-ranging administrative powers, including the right to take minors into custody without a warrant should their family disregard CSL requirements. Diligently strict enforcement can ensure that students from disadvantaged backgrounds stay in school longer than they would in absence of CSL.

Findings in this study point to important implications for policy design regarding racial equality. Firstly, educational attainment creates a basic foundation from which meaningful social participation and social inclusivity is promoted, and in this pursuit, CSL has been identified as an effective policy tool in improving educational outcomes for marginalized groups. The realized individual gains and aggregate societal benefits to CSL are considerable, since CSL disproportionately increases the level of education for those most at risk of leaving school prematurely and missing opportunities for learning, which have been shown to have short-, long-, and intergenerational effects (Shanan 2021). In considering the cost-benefit of a range of race equality interventions, policy makers should not overlook the critical role building better and stronger schools can play in ‘leveling the playing field’ for all (White House 2021). Secondly, while CSL is effective in increasing educational attainment, it certainly cannot single-handedly close racial gaps. Scholars have continuedly voiced concerns regarding the high disparity in school funding that exists between predominantly-Black and predominantly-White schools (Sosina and Weathers 2019). Schooling does not translate into learning the same way in Black or as in White neighborhoods, which is both consequence and contributor to race-based economic segregation (Reardon et al. 2021). In addition, findings in this study suggest that Black students only extend their school attendance up to the minimum school-leaving age requirement and are more likely to drop out prior to high school completion compared to their White counterparts. To this end, policy makers and researchers should focus on factors influencing patterns in the discontinuation of schooling among students from marginalized backgrounds, and devise targeted interventions to address race-related barriers to high school completion and beyond (Kim et al. 2015).

In any case, findings in this study shed light on the policy effectiveness and social equity implications of CSL reform that could be relevant for a range of developing countries, considering that adoption of such legislation can lead to improved educational access for students from disadvantaged and marginalized backgrounds. On the one hand, mandating school attendance through CSL can be a powerful equalizing force, particularly in the longer-term career time horizon. Importantly, simply going to school can be a salient gain for both individuals and society (Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011). Individuals, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, could miss ‘a million dollars on the sidewalk’ should they forego the opportunity to be in schools (Schuller et al. 2004). On the other hand, demand-side education interventions, such as CSL, can get students to school, but it is also critical to support student at school, and ensure they are ready to learn and accumulate meaningful learning experiences in classrooms. In this regard, school meals, transportation services, remedial support, and academic counseling have been identified as common learning-enhancing strategies that show promise in positively bolstering children from marginalized groups and disadvantaged communities take advantage of expanded educational access (World Bank 2017).

Nonetheless, it is worth pointing out that the CSL expansion episode examined in this study occurred during a very specific time period and in a geographically specific area of the American “South,” therefore precaution should be used when extrapolating to other contextual scenarios. Nonetheless, several contemporary policy takeaways are relevant. First, students from disadvantaged background can benefit from educational policies that require a certain minimum year of schooling. Education systems should actively consider the educational equity aspects of CSL, for which discussion on its heterogeneous effects are often masked by policies that target the population mean. Second, there remain many barriers to learning beyond age-requirements to attend school, and education systems should aim to address these limiting barriers and cultivate pro-learning environments that enable all students to grow and thrive.

Last but not least, while this study shows that CSL legal requirements on school attendance is critical for reducing Black-White racial gaps in school attendance and career wages, a remaining understudied area is exploring the intertwined relationship between CSL expansion, school quality, and student learning. For one, Anderson (1988) has found that Rosenwald Fund and Jeanes Foundation worked with local Black communities to build school infrastructure, which not only improves learning environments but also increase educational access to these communities. For another, Murphy (2003), Raudenbush (2008), and Raudenbush and Eschmann (2015) show that instruction and curriculum is a decisive mediator of school experiences. Therefore, the effectiveness of going to school depends substantively on how instruction and curriculum is tailored to meet the current needs of the child, especially for those from different racial, cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic backgrounds. Open to debate is whether the simultaneous improvements on school infrastructure, curriculum, and instruction represent in part some of the positive effects of CSL expansion, which warrants added interest on future research.

Data availability

Data used in this study is included as a supplementary file, which is publicly available via the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) database: https://doi.org/10.18128/D014.V4.0

References

Aaronson D, Mazumder B (2011) The impact of Rosenwald schools on Black achievement. J Political Econ 119(5):821–888

Acemoglu D, Angrist J (2000) How large are human-capital externalities? Evidence from compulsory schooling laws. In: Bernanke B, Rogoff K (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 15. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Akbulut-Yuksel M (2017) Do legal school leaving rules still affect schooling and earnings? Soc Sci Res 61:195–205

Akee R, Jones MR, Porter SR (2019) Race matters: Income shares, income inequality, and income mobility for all US races. Demography 56(3):999–1021

Anderson J (1988) The education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC

Angrist J, Krueger A (1991) Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Q J Econ 106(4):979–1014

Baker D (1999) Schooling all the masses: Reconsidering the origins of American schooling in the postbellum era. Sociol Educ 72:197–215

Baker D (2014) The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global Culture. Stanford University Press, Redwood City, CA

Barrow L, Rouse C (2005) Do returns to schooling differ by race and ethnicity? Am Economic Rev 95(2):83–87

Bell B, Costa R, Machin S (2016) Crime, compulsory schooling laws and education. Econ Educ Rev 54:214–226

Bernbaum G (1967) Social Change and the Schools, 1918-1944. Routledge, London

Bishop-Royse J, Lange-Maia B, Murray L, Shah RC, DeMaio F (2021) Structural racism, socio-economic marginalization, and infant mortality. Public Health 190:55–61

Bleakley H (2007) Disease and development: evidence from hookworm eradication in the American South. Q J Econ 122(1):73–117

Bound J, Jaeger D (2000) Do compulsory school attendance laws alone explain the association between quarter of birth and earnings? Res Labor Econ 19:83–108

Bowles S, Gintis H (1976) Schooling in Capitalist America. Basic Books Inc, New York

Buckles K, Hungerman D (2013) Season of birth and later outcomes: Old questions, new answers. Rev Econ Stat 95(3):711–724

Cano-Urbina J, Lochner L (2019) The effect of education and school quality on female crime. J Hum Cap 13(2):188–235

Card D, Krueger A (1992) School quality and Black-White relative earnings: A direct assessment. Q J Econ 107(1):151–200

Card D, Rothstein J (2007) Racial segregation and the Black–White test score gap. J Public Econ 91(11-12):2158–2184

Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones M, Porter S (2020) Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. Q J Econ 135(2):711–783

Clay K, Lingwall J, Stephens Jr M (2021) Laws, educational outcomes, and returns to schooling evidence from the first wave of US state compulsory attendance laws. Labour Econ 68:101935

Congressional Research Service (2013) Child Labor in America: History, Policy, and Legislative Issues. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC

Cruz L, Moreira M (2005) On the validity of econometric techniques with weak instruments inference on returns to education using compulsory school attendance laws. J Hum Resour 40(2):393–410

Dabney C (1936) Universal Education in the South: Volume 2. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC

Ensign F (1921) Compulsory School Attendance and Child Labor. Faculty of Philosophy, Columbia University, New York, NY

Fryer R, Dobie W (2014) The Impacts of Attending a School with High-Achieving Peers: Evidence from the New York City Exam Schools. Am Econ J Appl Econ 6:58–75

Fisher C, Hout M, Jankowski M, Lucas S, Swidler A, Voss K (1996) Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Giersch J (2018) Academic tracking, high-stakes tests, and preparing students for college: How inequality persists within schools. Educ Policy 32(7):907–935

Goldin C (1998) America’s graduation from high school: The evolution and spread of secondary schooling in the twentieth century. J Economic History, 58, 345–374

Goldin C, Katz L (2008) The Race between Education and Technology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Greene M, Jacobs J (1992) Urban enrollments and the growth of schooling: Evidence from the US 1910 Census public use sample. Am J Educ 101(1):29–59

Hallinan M (2001) Sociological perspectives on Black-White inequalities in American schooling. Sociol Educ, 74:50–70

Halsey A, Heath A, Ridge J (1980) Origins and Destinations: Family Class, and Education in Modem Britain. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) (2021) IPUMS Documentation: User Guide. IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN

Katz M (1976) A History of Compulsory Education Laws. Fastback Series, No. 75. Bicentennial Series. Phi Delta Kappa, Bloomington, IN

Kim S, Chang M, Singh K, Allen KR (2015) Patterns and factors of high school dropout risks of racial and linguistic groups. J Educ Stud Place Risk 20(4):336–351

Kugler T, Fitch C (2018) Interoperable and accessible census and survey data from IPUMS. Sci Data 5:180007

Landis R, Reschly A (2011) An examination of compulsory school attendance ages and high school dropout and completion. Educ Policy 25(5):719–761

Liu J (2021) Exploring Teacher Attrition in Urban China through Interplay of Wages and Well-being. Educ Urban Soc 53(7):807–830

Liu J, Xie JC (2021) Invisible Shifts In and Out of the Classroom: Dynamics of Teacher Salary and Teacher Supply in Urban China. Teach Coll Rec 123(1):1–38

Lang K, Kropp D (1986) Human capital versus sorting: the effects of compulsory attendance laws. Q J Econ 101(3):609–624

Lleras-Muney A (2002) Were compulsory attendance and child labor laws effective? An analysis from 1915 to 1939. J Law Econ 45(2):401–435

Lleras-Muney A (2005) The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. Rev Economic Stud 72(1):189–221

Lleras-Muney A, Shertzer A (2015) Did the Americanization movement succeed? An evaluation of the effect of english-only and compulsory schooling laws on immigrants. Am Economic J 7(3):258–290

Margo R, Finegan T (1996) Compulsory schooling legislation and school attendance in turn-of-the century America: A ‘natural experiment’ approach. Econ Lett 53(1):103–110

Massey D, Denton N (1993) American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Merolla D, Jackson O (2019) Structural racism as the fundamental cause of the academic achievement gap. Sociol Compass 13(6):e12696. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12696

Meyer J, Ramirez F, Rubinson R, Boli-Bennett J (1977) The world educational revolution, 1950–1970. Sociol Education, 50:242–258

Meyer J, Tyack D, Nagel J, Gordon A (1979) Public education as nation-building in America: Enrollments and bureaucratization in the American states, 1870–1930. Am J Sociol 85(3):591–613

Murphy S (2003) Optimal dynamic treatment regimes. J R Stat Soc: Ser B 65(2):331–355

Oakes J (1985) Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

OECD (2011) Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. OECD, Paris, France

Oreopoulos P (2006) Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter. Am Economic Rev 96(1):152–175

Oreopoulos P (2007) Do dropouts drop out too soon? Wealth, health and happiness from compulsory schooling. J Public Econ 91(11–12):2213–2229

Oreopoulos P, Salvanes K (2011) Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. J Economic Perspect 25(1):159–184

Oreopoulos P, Page M, Stevens A (2006) The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling. J Labor Econ 24(4):729–760

Pfeffer FT, Fomby P, Insolera N (2020) The Longitudinal Revolution: Sociological Research at the 50-Year Milestone of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Annu Rev Sociol 46:83–108

Provasnik S (2006) Judicial activism and the origins of parental choice: The court’s role in the institutionalization of compulsory education in the United States, 1891–1925. Hist Educ Q 46(3):311–347

Psacharopoulos G, Patrinos H (2018) Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Educ Econ 26(5):445–458

Raudenbush S (2008) Advancing educational policy by advancing research on instruction. Am Educ Res J 45(1):206–230

Raudenbush S, Eschmann R (2015) Does schooling increase or reduce social inequality. Annu Rev Sociol 41(1):443–470

Rauscher E (2014) Hidden gains: Effects of early US compulsory schooling laws on attendance and attainment by social background. Educ Eval Policy Anal 36(4):501–518

Reardon S, Kalogrides D, Shores K (2019) The geography of racial/ethnic test score gaps. Am J Sociol 124(4):1164–1221

Reardon S, Weathers E, Fahle E, Jang H, Kalogrides D (2021) Is Separate Still Unequal? New Evidence on School Segregation and Racial Academic Achievement Gaps. CEPA Working Paper No. 19.06. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis, Palo Alto, CA

Redcay E (1935) County Training Schools and Public Secondary Education for Negroes in the South. John F. Slater Fund,Washington, DC

Reyes A (2020) Compulsory School Attendance: The New American Crime. Educ Sci 10(3):75

Rothstein R (2004) The Achievement Gap: A Broader Picture. Educ Leadersh 62(3):40–43

Ruggles S, Flood S, Foster S, Goeken R, Pacas J, Schouweiler M, Sobek M (2021) IPUMS USA: Version 11.0 [dataset]. IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN

Sansani S (2015) The differential impact of compulsory schooling laws on school quality in the United States segregated South. Econ Educ Rev 45:64–75

Schuller T, Preston J, Hammond C, Brassett-Grundy A, Bynner J (2004) The Benefits of Learning: The Impact of Education on Health, Family Life and Social Capital. Routledge, London

Shanan Y (2021) The effect of compulsory schooling laws and child labor restrictions on fertility: evidence from the early twentieth century. J Popul Econ, 36, 321–358

Sosina V, Weathers E (2019) Pathways to inequality: Between-district segregation and racial disparities in school district expenditures. AERA Open 5(3):2332858419872445

Steffes T (2012) School, Society, and State: A New Education to Govern Modern America, 1890–1940. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Stephens Jr M, Yang D (2014) Compulsory education and the benefits of schooling. Am Economic Rev 104(6):1777–1792

Tyack D (1976) Ways of seeing: An essay on the history of compulsory schooling. Harv Educ Rev 46(3):355–389

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1963) Census of Population, 1960: Characteristics of the Population. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1983) Census of Population, 1980: Characteristics of the Population. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Labor (1946) State Child-Labor Standards. A State-by-State summary of laws affecting the employment of minors under 18 years of age. U.S. Department of Labor, Division of Labor Standards, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Labor (1949) State Child-Labor Standards. A State-by-State summary of laws affecting the employment of minors under 18 years of age, Bulletin 114. U.S. Department of Labor, Division of Labor Standards, Washington, DC

Walters, P (2001) Educational access and the state: Historical continuities and discontinuities in racial inequality in American education. Sociol Education 74:35–49

Welch F (1973) Black-White differences in returns to schooling. Am Economic Rev 63(5):893–907

White House (2021) How the Biden-Harris Administration Is Advancing Educational Equity. The White House Press Statement, Washington, DC

World Bank (2017) World development report 2018: Learning to realize education’s promise. World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Institute for Social Research and Data Innovation at the University of Minnesota for data access to IPUMS. I thank Jeehee Han and Taeko Suga for excellent research assistance and thoughtful comments. All errors are my own. This work was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China [Grant ID: CJA200256].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study is independently authored.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the author(s).

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the author(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J. Education legislations that equalize: a study of compulsory schooling law reforms in post-WWII United States. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 966 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03460-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03460-0