Abstract

A few studies have explored the use of interactional metadiscourse markers in argumentative writing by male and female college students. More importantly, none explored the topic of metadiscourse resources with respect to gender-sensitive topics. Thus, the present study aims at examining the exploitation of interactional metadiscourse markers by Saudi male and female English as a Foreign Language (EFL) college students in their writing about ‘Who are Better Drivers, Men or Women?’. The study is corpus-based on students’ essays. The corpus consists of four sub-corpora: (a) men favouring men, (b) men arguing for women, (c) women arguing for men and (d) women writing in favour of women. We followed a qualitative and quantitative approach to data analysis. Using AntConc and Hyland’s (2005) metadiscourse model of interactional markers, the results reveal that female writers employed attitudinal lexis, hedges, self-mentions and boosters more than male writers. As for the variables of gender and stance choice, females arguing for men’s driving significantly utilised hedges more than the other three groups. Additionally, female writers writing in support of female drivers significantly used self-mentions more than male writers arguing for men’s driving. This study shows that sensitive topics may cause a difference in the distribution of metadiscourse markers used by people of both genders, and it provides some pedagogical implications for EFL instructors and curriculum developers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Writing is a complicated skill that requires more than full understanding of the grammar rules in the target language. Efficient writing necessitates knowledge of writing as a social and communicative activity. It involves cognitive, psychomotor and linguistic abilities (Bazerman, 2009; Byrnes and Manchón, 2014). The communicative function of writing becomes even more evident in argumentative writing where the author has to carefully utilise appropriate rhetorical structures that reflect conventional practices in a community for the purpose of persuading someone. It requires logical reasoning, sequencing thoughts and linguistic features to build some relationship with readers (Hyland, 2005; Jones, 2011).

As noted above, writing becomes more challenging if the task involves argumentation. Though argumentative writing, defined as a piece of writing that ‘attempts to support a controversial point or defend a position on which there is a difference of opinion’ (Richards and Schmidt, 2002, p. 337), is one of the most common genres (Hyland, 1999), it is the most difficult for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners and English as a Second Language (ESL) learners (Lee and Deakin, 2016; Yoon, 2021). It requires taking a position in an argument over a controversial topic for the purpose of persuading a group of people of the validity of one’s claim. More importantly, it involves agreeing or disagreeing with previous, current and prevailing opinions (Swales, 1990). Thus, EFL and ESL learners have to employ argumentative writing resources used by professional writers, such as evidentiality (Chafe and Nichols, 1986), metadiscourse markers (Crismore, 1989; Hyland, 2005), stance (Biber, 2006a; Biber and Zhang, 2018) and voice (Thompson, 1996). Speaking of metadiscourse markers and their benefits, Hyland and Tse (2008) argued that metadiscourse is a useful linguistic resource that enables authors to communicate their attitude towards a specific proposition to their readers.

Metadiscourse has been labelled stance (Biber and Finegan, 1989; Hyland, 1999), evaluation (Hunston and Thompson, 2000), attitude (Halliday, 1994), appraisal (Martin, 2000), epistemic modality (Hyland, 1998) and metadiscourse markers (Crismore, 1989; Hyland, 2005; Hyland and Tse, 2008). The term metadiscourse has been proposed by Harris (1959) to describe how texts’ recipients perceive a piece of writing as intended by writers or speakers. As noted by Hyland (2005), metadiscourse refers to ‘self-reflective expressions used to negotiate interactional meanings in a text, assisting the writer (or speaker) to express a viewpoint and engage with readers as members of a particular community’ (p. 37). It is the umbrella term that includes linguistic elements used to establish a rapport between the writer and reader and signal the writer’s stance. Stance involves the writer’s position or attitude towards the content being discussed. Stance can be studied from the perspectives of evaluation, attitude, appraisal theory and epistemic modality (Xie et al., 2024). Evaluation performs three functions: (a) it expresses a language user’s opinion and reflects the value system of people and their community; (b) it constructs and maintains relations between producer and receiver of the language; and (c) it organises discourse. Appraisal and attitude are related concepts in that both refer to linguistic features language users utilise to express their subjective attitude towards an entity. The words horrible and fantastic are typical examples. Epistemic modality refers to speakers or authors’ confidence or lack of confidence about their message, which can be expressed through hedges and boosters (Pearson and Abdollahzadeh, 2023).

There is a dearth of studies that have examined metadiscourse markers in the argumentative writing of EFL and ESL students (El-Dakhs, 2020; Papangkorn and Phoocharoensil, 2021; Yoon, 2021). Though some research (cf. Zare-ee and Kuar, 2012) showed that there are differences in writing between male and female EFL writers, only few (Aziz et al., 2016) have explored the distribution of metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays written by male and female writers. This necessitates further exploration of this area, especially if some researchers such as El-Dakhs (2020) and Yoon (2021) suggest that topic choice may affect students’ utilisation of metadiscourse markers. Further, Hyland and Tse (2008) explain that the use of metadiscourse resources may differ across gender and discipline and that the relationship between gender and language is never predictable. Hence, we chose to analyse essays written by Saudi male and female EFL students on a gender-sensitive topic like the superiority of either gender in driving cars. Middle Eastern women are expected to be less assertive when they argue for themselves (cf. Zare-ee and Kuar, 2012). Alanazi et al., (2023) reported that though Saudi women are allowed to play more powerful roles than before, they ‘still perceive themselves as lacking in assertiveness and leadership skills compared to men’ (p. 3).

There are a number of social factors that forced Saudi women to develop a less assertive personality. Before the new reforms, for example, Saudi women were not allowed to travel without the permission of a male guardian (Alanazi et al., 2023). As for women’s right to drive cars, Saudi women were not permitted to drive for decades. Although Saudi women were given the chance to hold high-status occupations such as doctors, managers and academics, they had to rely on a male chaperone or driver to get them around (Saleh and Malibari, 2021). The ban on car driving by women was lifted in 2018 following King Salman’s 2017 statement (BBC, 2017). In addition, as part of the Saudi 2030 Vision, the Saudi government encouraged women to drive, issued a number of legislative reforms and launched a few programmes to ensure women’s empowerment and equality with men (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023). When the researchers were collecting the data for the present study, more than 3 years passed and as most of the community allowed their female relatives to drive, there were a few Saudi citizens who were reluctant and doubtful of the whole experience. Thus, the topic of who is better at driving cars is a bit sensitive and debatable nowadays. Based on the argument above, gender, topic and stance choice may have an effect on the type, frequency and distribution of interactional metadiscourse resources. Thus, the present study addresses the following questions:

-

1.

How do Saudi EFL students of male and female writers use interactional metadiscourse markers in their argumentative writing about car driving?

-

2.

How do Saudi EFL students use interactional metadiscourse markers when writing about a gender-sensitive topic?

-

a.

How do male writers use metadiscourse markers to argue in favour of their own driving or in favour of women driving?

-

b.

How do female writers use metadiscourse markers to argue in favour of their own driving or in favour of men driving?

-

a.

Review of literature

Recent research on the use of interactional metadiscourse markers by EFL writers has focused more on research articles (Al-Zubeiry and Assaggaf, 2023), including abstracts (Alghazo et al., 2021; Assassi, 2023; Assassi and Merghmi, 2023) and discussion sections (Asadi et al., 2023; Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024), dissertations and theses (Fendri, 2020; Jabeen et al., 2023), virtual lectures (Rabab’ah et al., 2024), etc. However, a small number of studies have explored interactional metadiscourse markers in argumentative writing by undergraduates. In addition, studies examining the distribution of interactional metadiscourse markers in writings by both genders considered reviews, opinion columns, dissertation acknowledgements, consultations and disciplines. This section elaborates on the findings of some key studies.

Studies on the use of metadiscourse markers in argumentative writing

Studies on metadiscourse use in argumentative writing have been conducted by Mahmood et al. (2017), Papangkorn and Phoocharoensil (2021) and El-Dakhs (2020). Researchers examined the frequency and distribution of metadiscourse markers in relation to some variables such as those of proficiency (El-Dakhs, 2020; Handayani et al., 2020; Yoon, 2021), nativeness (El-Dakhs, 2020; Lee and Deakin, 2016; Papangkorn and Phoocharoensil, 2021), learning context (El-Dakhs, 2020), topic variation (Yoon, 2021) and first language (L1) differences (Yoon, 2021). Some researchers such as El-Dakhs (2020) recommend exploring other factors such as culture, prompts and essay types.

Considering topic selection as a variable, Yoon (2021) examined metadiscourse features in writing samples by EFL students with different L1 backgrounds (i.e. Chinese, Korean and Japanese). Besides L1 differences and topic choice, the last variable that has been examined was the effect of L2 proficiency (A2, B1.1 and B1.2) on students’ use of interactional markers. Students were asked to write about two topics: the importance for college students to have a part-time job and banning smoking at restaurants. The researcher’s analysis of the data showed no significant two-way interaction effect between L1 background and L2 proficiency nor between L2 proficiency and topic. However, Yoon (2021) demonstrates a significant interaction between different topics and L1 differences. Since El-Dakhs (2020) and Yoon (2021) drew attention to the effect of topic choice as a variable, there is a need to explore the effect of a gender-sensitive topic on undergraduates’ argumentative essays with a focus on stance selection. Additionally, the importance of the present study stems from the fact that there are few studies that have addressed the use of metadiscourse markers with respect to topic and stance variation.

Gender-based differences in the use of interactional metadiscourse markers

Previous studies (Morris, 1998; Zare-ee and Kuar, 2012) focusing on differences in writing between male and female ESL students show that female writers in general perform better than male writers and more specifically in terms of their adherence to writing guidelines. However, Zare-ee and Kuar (2012) and Yeganeh and Ghoreyshi (2015) argue that male EFL Iranian writers are more assertive and argumentative in their writing compared to female students. Zare-ee and Kuar (2012) explain that the difficulty in expressing a more assertive attitude is mainly because of cultural reasons, where Iranian women are expected to be less talkative and a bit submissive.

Research addressing the role of gender in the use of metadiscourse markers has been conducted with undergraduates (Mokhtar et al., 2021; Pasaribu, 2017), professional writers (Latif and Rasheed, 2020; Zadeh et al., 2015), EFL males and females writing argumentative (Aziz et al., 2016) and personal essays (Puspita and Suhandano, 2023). More importantly, Hyland and Tse (2008) have investigated metadiscourse resources in reviews written by natives of both genders. In other words, they have analysed reviews of philosophy and biology books written by male and female reviewers. The books themselves are written by professional writers of both genders. Nevertheless, despite the many studies on gender and metadiscourse markers, such studies have revealed conflicting results.

As some (Latif and Rasheed, 2020; Mokhtar et al., 2021; Zadeh et al., 2015) found that male writers use boosters more than female writers, others (Pasaribu, 2017; Latif and Rasheed, 2020) reported that females hedge more than males. Nonetheless, Hyland and Tse (2008) and Puspita and Suhandano (2023) note that male writers hedge more when they write a review or a personal essay. In addition, Pasaribu (2017) argues that males foreground themselves in academic writing. Further, Zadeh et al. (2015) reported that female writers used a more engaging style compared to male writers. Moreover, Azlia (2022) notes that female speakers employed hedges, boosters and attitudinal resources more than male speakers in TED Talks (i.e. talk videos by influential people). In terms of disciplines, Azher et al. (2023) argued that professional female writers hedged more in social sciences, whereas males used more boosters in humanities. In addition, Farahanynia and Nourzadeh (2023) found that engagement and attitude markers were commonly used by female researchers in applied linguistics. On the other hand, boosters and self-mentions were significantly found in male writers’ research articles in the same discipline. Nevertheless, Hyland and Tse (2008) and Zadeh et al. (2015) claim that male writers use engagement markers more than female writers when they write about biology and translation. Moreover, Hyland and Tse (2008) state that male reviewers produce more evaluative critiques when they review writings by male writers. This illustrates that topic choice, discipline and stance towards or against one gender play a role in the frequency and distribution of metadiscourse markers in writings by both gender members.

Studies on the use of interactional metadiscourse markers by Arabs

Studies on the use of interactional metadiscourse markers by Arabs have focused on professional writers (Alghazo et al., 2021; Alsubhi, 2016) and postgraduates (Ahmed and Maros, 2017; Alotaibi, 2018; Fendri, 2020; Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024). They considered the genres of column writing, academic consultations, research article abstracts, dissertation acknowledgements, dissertation discussion sections, full dissertations and internship reports. Speaking of gender as a variable in acknowledgements, Alotaibi (2018) reported that there are no differences between the two genders in terms of boosters and attitudinal resources. However, Saudi female writers used boosters more in recognition of moral support, whereas men utilised boosting devices more frequently when they acknowledged academic assistance. The opposite is true in case of both genders’ use of attitude markers. Saudi females used attitude markers more in thanking for academic assistance. Moreover, Alsubhi (2016) notes that Saudi male writers hedge more when they write a column. Yet, Alsubhi (2016) found that female columnists used self-mentions and engagement markers more than male columnists. In addition, Ahmed and Maros (2017) state that females used hedging devices more than males in verbal consultations. Further, focusing on the discussion sections in applied linguistics master’s theses, Merghmi and Hoadjli, (2024) reported that boosters are mainly associated with Algerian male postgraduates, whereas hedges are linked with their female counterparts. Focusing on genre as a variable, Fendri (2020) found that Tunisian EFL academic writers used hedges more in dissertations but employed more of self-mentions, engagement resources and attitudinal lexis in internship reports. As for language as a variable, English abstracts include more of hedges and engaging resources compared to those written in Arabic (Alghazo et al., 2021). As shown above, no study has explored the use of interactional metadiscourse markers by EFL Arab college students.

Based on the review above, only one study (i.e. Yoon, 2021) explored the use of interactional metadiscourse markers in relation to two different neutral topics. However, there is only one (Aziz’s et al., 2016) that focused on gender differences in using such markers in argumentative essays by EFL students. Further, there is only one important study by Hyland and Tse (2008) that explored the use of metadiscourse resources across gender and disciplines. Hence, because of this methodological gap, there is a need to examine differences between male and female writers in using metadiscourse markers in relation to a gender-sensitive topic, especially if the topic is about one gender’s ability in driving cars. Hence, this study aims at exploring the use of metadiscourse markers across genders and stances on a gender-sensitive topic.

Methods

The methodology used in this study was both quantitative and qualitative, a mixed-methods approach. In the quantitative analysis, we looked at the frequency of metadiscourse markers, while in the qualitative stage, we explored the context in which each metadiscourse marker occurred to code each marker with respect to interactional metadiscourse categories. In the qualitative phase, we also interpreted the occurrence of the most frequent metadiscourse markers. In other words, the explanatory sequential mixed methods model was selected because the phase of interpretation of significant occurrences followed that of counting frequencies (Toyon, 2021).

Participants

A total of 144 (59 males and 85 females) undergraduate students majoring in English translation participated in the study. During their intermediate and high school years, they all studied English as a foreign language as a compulsory subject. In other words, participants received an average of around 6 years of English instruction.

Data collection tool

To investigate how the participants employed metadiscourse markers, a writing task on a gender-sensitive topic was given. The writing task took the form of an argumentative essay, consisting of four paragraphs in which students had to argue whether Saudi men drive better than Saudi women or whether Saudi women drive better than Saudi men. The students were required to write an argumentative essay (i.e. an introduction, two body paragraphs, a conclusion) of no less than 400 words on that trendy topic and choose a stance and present arguments that would convince the reader (their instructor) as to why Saudi men are superior drivers to women and vice versa. The corpus was collected during the Autumn Semester of 2021 when students took this task as part of their final exam for the course of Academic Writing (TRAJ 221), offered as a compulsory course to Level-Four students.

Data collection procedure

Prior to the final exam, students received instruction in different types of writings including the argumentative essay, mainly on how they develop and organise ideas, but they did not receive any explicit instruction in using metadiscourse markers. Further, before starting the procedure of data collection, students of all groups were given a writing exam of a different argumentative topic to make sure that there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of their writing ability. Essays were corrected by experienced writing instructors. Students’ scores were analysed using Independent Samples t Test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results of the statistical tests are given in the Results Section.

The corpus

After the essays had been collected, they were typed by the researchers and sorted according to the stance taken by the writers, i.e. into four sub-corpora. The following table shows the details of these corpora.

As illustrated in Table 1, the corpus compiled was composed of 144 essays and 46,453 tokens (i.e. the total number of words in the corpus). The essays were written by 59 males and 85 females. The total number of words in the corpus by male writers is 14,888 words, and the total number of that of female writers is 31,565 words. Table 1 also shows the number of word tokens and types (i.e. unique word forms in a corpus) in each sub-corpus.

Apparently, the number of participants contributing to the corpus of male writers (i.e. 59 students) is smaller than that of female writers (i.e. 85 students). Hence, the number of words in the corpus of male writers is also proportionally smaller than the corpus of female writers. This is mainly because the number of male students registering for the course is smaller than that of female students. To account for such differences, the researchers normalised frequencies by dividing the raw frequencies of tokens by the number of words in a corpus; and then, multiplying the total by 1000 words.

Analytical framework

Hyland’s (2005) analytical framework was used to examine metadiscourse use. In spite of the subjective nature of metadiscourse identification, Hyland’s (2005) model has proved its objectivity and comprehensiveness. Researchers (cf. Alghazo et al., 2023; Alqahtani and Abdelhalim, 2020; Peng and Zheng, 2021; inter alia) relied heavily on this framework for their metadiscourse research. Hyland’s (2005) model of interaction is made up of two dimensions: interactive and interactional. The interactive dimension is concerned with guiding the reader through the text using transitions (i.e. expressing relations between clauses using in addition, but, etc.), frame markers (e.g. markers referring to discourse acts such as to sum up, finally, etc.), endophoric markers (e.g. markers referring to different information mentioned in different parts of a text such as see the table below, as noted above, etc.), evidentials (i.e. markers referring to information sources, e.g. according to, X stated, etc.) and code glosses (i.e. markers clarifying meaning, e.g. such as, in other words, etc.). However, the interactional dimension involves the reader in the argument through the use of hedges (i.e. markers that withhold one’s commitment towards a proposition, e.g. may, perhaps, etc.), boosters (i.e. markers that emphasise certainty in a proposition, e.g. certainly, definitely, etc.), attitude markers (i.e. resources used to express one’s attitude towards a proposition, e.g. I agree, surprisingly, etc.), self-mentions (i.e. resources that give explicit reference to the text’s author(s), e.g. we, I, etc.) and engagement markers (i.e. resources meant to establish a relationship with the reader, e.g. note, consider, etc.). Since the latter dimension is concerned with reader-writer interaction, it has been the focus of many studies (see Hyland, 2000, 2005; Park and Oh, 2018). By the same token, the focus of this study is only on interactional discourse resources.

Analytical software

The data were analysed with the concordance software, AntConc, developed by Laurence Anthony, which permitted counting frequencies of hits and examining context as it proved to be necessary to do so because not all hits had metadiscourse value. For instance, the word ‘pretty,’ which could have been counted as an attitude marker, was in fact a booster in the sentence: It is easier for them to master it pretty quickly. Another example is the word ‘way’ which was found to be a booster in the sentence: Men are way better at driving. The researchers used mainly the Word List Feature, which provides information on word frequency and the Keyword-in-Context Feature, which helps in showing concordances or contexts of words in question (Anthony, 2022). The Programme was used by several researchers (cf. Ardhianti et al., 2023; Khattak et al., 2023) in their metadiscourse analysis.

Reliability

The two researchers initially coded 25% of the data (i.e. the corpus of essays written by male Saudis). For this sub-corpus, the categorisation of words and their frequency results have been verified and checked against reliable resources on Hyland’s (2005) Model of Metadiscourse Markers. However, 20% (i.e. part of the written corpus by female Saudis) of the data was used to measure inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability is defined as the extent to which two coders (i.e. the researchers) agree on assigning the same code to the same data item (Krippendorff, 2004). Cohen’s kappa was used to achieve inter-rater reliability. It is calculated by counting instances of agreement and disagreement given by both coders. In other words, it helps in computing the average number of agreements for a certain amount of data. Cohen’s kappa was selected because it reduces the possibility of assigning the same category to the same item by mere chance.

The results showed that the researchers agreed to include 1215 of the tokens and excluded 107 of them. Nevertheless, the first researcher included 64 of the occurrences, whereas the second chose to include only 34. Results of Cohen’s kappa (0.647) showed substantial agreement. Disagreement between researchers was on coding some words which have been coded differently by previous researchers such as cannot as a booster (Yoon and Römer, 2020) or as a hedge (Hyland, 2005), specifically as a code gloss (Hyland, 2005) or as a booster (Yoon and Römer, 2020), should as a hedge (Hyland, 2005) or as a booster (Macintyre, 2013; Yoon and Römer’s, 2020), find as an engagement marker (Hyland, 2005) or as a booster (Yoon and Römer’s, 2020), still as a transition marker (Hyland, 2005) or as a booster (Macintyre, 2013), see as think and see as find. However, as mentioned above, we followed Hyland’s Model and checked context in case of any doubts.

Data analysis

The basic features of the data in the study, such as minimum, maximum, skewness, kurtosis, mean and standard deviation (M ± SD), were described using descriptive statistics. Secondly, inferential statistics was used to measure the difference between the writing groups in the study. First, prior to conducting any statistical analysis, the assumptions of parametric statistics were inspected using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which was used to check the statistical significance of the normal distribution of continuous variables. Depending on the outcomes of the test, parametric or non-parametric statistics were used.

More importantly, in the present study, Independent Samples t Test, an inferential statistical test (Ruxton, 2006), was used to compare the means of both groups of participants (i.e. male and female writers). Independent Samples t Test is essential to make sure that there were no significant differences between male and female students in terms of their writing ability based on a test given to them before starting the process of data collection. Independent T Test was also performed to determine whether or not there was a statistically significant difference in the number of words (i.e. boosters, attitude markers, hedges, engagement markers and self-mentions) used by the two groups of male and female writers in support of their point of view. Additionally, we used one-way ANOVA, another inferential statistical test (Alexander et al., 2019), to compare the four independent samples (i.e. the four groups of writers) in terms of their writing ability. If a significant difference between the four groups is found, the LSD (least significant difference) test will be used. It will help pinpoint exactly which groups are different from each other. It does this by figuring out the smallest difference between any two groups’ averages that will be considered statistically significant (Ruxton, 2010). ANOVA test was also used to determine whether or not there was a statistically significant difference in the number of words (i.e. boosters, attitude markers, hedges, engagement markers and self-mentions) used by the four groups of writers in support of their point of view. P values that are less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

With large enough sample sizes per group (>30 or 40), the violation of the normality assumption should not cause major problems (Pallant, 2020); this implies that we can use parametric procedures even when the data are not normally distributed (Elliott and Woodward, 2007). In other words, if we have samples consisting of hundreds of observations, we can ignore the distribution of the data (Altman and Bland, 1995). In addition, according to the central limit theorem, the sampling distribution tends to be normal in large samples (>30 or 40) regardless of the shape of the data (Field, 2009). In contrast, a distribution is considered normal if it has skewness indices of less than 2 and kurtosis values of less than 7 (West et al., 1995). We used kurtosis and skewness to examine if the data were normally distributed for all the variables in the study to compare between males (n = 59) and females (n = 85). The results showed that all skewness values were less than 2, and all kurtosis values were less than 7 for all the variables, so the parametric T test was used (see Table 2 below).

To make sure that the two groups of male and female writers were equivalent, Independent Samples t Test was performed and the results illustrate that male writers have a mean score of (16.85 ± 6.232) compared to that of (18.29 ± 3.386) by female writers with a small difference of 1.44 out of 25 degrees. This indicates that there was no significant difference between male and female writers in terms of their writing ability before starting the procedure of data collection. Table 3 below is illustrative.

As for comparing the four groups in terms of their writing ability, assumptions of parametric statistics were considered for the four groups: (a) males writing in favour of males: n = 39, (b) males writing for females: n = 20, (c) females arguing for males: n = 19 and (d) females in support of female drivers: n = 66. The results showed that all skewness values were less than 2, and all kurtosis values were less than 7 for all the variables, so the data were approximately normally distributed among the four groups (see Table 4 below). Hence, the researchers used the parametric test of ANOVA to compare the four groups in terms of their writing ability.

Table 5 below shows that the test result of ANOVA is (F-ANOVA = 1.685, p = 0.047 < 0.05). It indicates that there was a significant difference between the four groups of writers with regard to their writing ability. After finding a significant difference between some groups using ANOVA, the LSD test was used to figure out the difference between which two groups’ averages would be considered statistically significant (Ruxton, 2010). Further, pairwise tests showed that the group of male writers arguing for female writers had the lowest mean score (15.70 ± 5.849) with a significant difference between it and that of females favouring women’s driving (18.38 ± 3.048). However, this would not have any effect on students’ use of metadiscourse markers, as previous researchers (El-Dakhs, 2020; Yoon, 2021) note that there is no significant relationship between language proficiency and students’ use of metadiscourse markers.

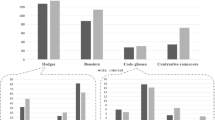

Gender differences in writers’ use of interactional metadiscourse markers

Independent Samples t Tests were performed again to determine whether or not there was a statistically significant difference in the number of words (i.e. boosters, attitude markers, hedges, engagement markers and self-mentions) utilised by male and female writers to support their point of view. Table 6 below shows that there was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in using boosters, attitude markers, hedges and self-mentions by male and female writers in favour of female writers. Male writers scored 12.59 ± 6.349 in using boosters compared to female writers whose score is 22.34 ± 7.893 and achieved a score of 15.24 ± 5.937 in employing attitude markers in comparison to female writers whose mean score is 24.01 ± 8.430. The same applies to the use of hedges and self-mentions. Female writers employed hedges (females: 10.33 ± 4.917; males: 8.51 ± 4.337) and self-mentions (females: 5.39 ± 3.704; males: 3.59 ± 3.696) more than male writers. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in their use of engagement markers. It is important to note that measures of association (Eta Square, η2) were performed to find the effect size. Cohen (1988) defined effects as small at (η2 = 0.01), medium at (η2 = 0.06) and large at (η2 = 0.14). Quantitative results are supplemented with qualitative and contextual analysis given in this section.

As advanced above, attitude markers were more commonly used by writers of each gender. Using normalised frequencies, there are 54,33 occurrences per 1000 words in males’ essays and 64,66 instances in females’ writings. Boosters came second (i.e. males: 44,26; females: 60,16), whereas the category of hedges (i.e. males: 29,95; females: 27,81) was ranked third. Self-mentions (i.e. males: 11,95; females: 14,50) came fourth and engagement markers (i.e. males: 11,08; females: 8,07) occupied the last place (see Table 8 in the Appendix). As shown above, normalised frequencies confirmed T test results that there were differences between male and female writers in favour of the latter group in terms of their use of self-mentions, boosters and attitude markers.

To show a certain attitude towards the suggested topic, ‘good,’ ‘better,’ and ‘even’ are very common in essays by writers of both genders. Nevertheless, ‘easily,’ ‘important,’ ‘long,’ and ‘hard’ were preferred by male writers, whereas ‘bad,’ ‘important,’ and ‘careful’ were more utilised by female writers. As male writers wanted to prove that driving is hard and cannot be done easily by women (Examples 1 and 2), female writers’ attitude is best reflected by attitudinal lexis that manifests importance and which gender has proven to be careful in driving (Examples 3 and 4).

-

1.

Firstly men are better at focusing and do not get distracted easily in my opinion. Plus, cars are made for men mostly, so women will be having a hard time driving on the streets because I think most of them are short, they cannot see the mirrors of the car.

(Male for males)

-

2.

In my point of view the men drive better than women and men can control his car in any hard scenario and he can take care of his car.

(Male for males)

-

3.

In conclusion, I see that women have better skills in what is related to driving a car. Women responsibility while driving a car will perform less accidents. Moreover, that awareness that women have about never thought of drifting is strongly important.

(Female for females)

-

4.

Another important thing is women have more discipline which means they can control themselves more than men who are known to have problems when it comes to controlling their feeling.

(Female for females)

Concerning boosters, if writers wanted to boost their claims, females employed ‘think,’ ‘believe,’ ‘many,’ ‘a lot,’ and ‘all.’ On the other hand, males selected ‘more,’ ‘a lot,’ ‘know,’ ‘say,’ ‘think,’ and ‘all.’

-

5.

I think men can drive better than women for two reasons.

(Male for males)

-

6.

A lot of people think that women cannot control a car without giving them a chance to try.

(Female for females)

-

7.

We did not see many women had car accidents.

(Female for females)

In addition, both genders tended to use ‘all’ as a boosting device, but it has been used differently by both groups. For example, female writers generalised using ‘all’ to describe that females took all driving lessons, know all driving aspects and that all females cause fewer accidents, and all reports have proven that (Example 8). On the other hand, males used ‘all’ to emphasise that all men, with no exception, know how to drive better than women (Example 10) and learn it faster (Example 9).

-

8.

All reports proved their ability to drive a car better than men.

(Female for females)

-

9.

All of men 1 week is the time for learning them.

(Male for males)

-

10.

We all know that we drive much more better than women do, but women refuse admitting it.

(Male for males)

As for hedging by both writer groups, males and females preferred to use ‘can,’ ‘some,’ and ‘most.’ It is important to note that ‘most’ has been used by female writers to argue that most males use cell phones while driving, do not know driving rules and thus cause car accidents. On the other hand, for men, most women are slow at driving. Females’ frequent use of ‘can’ as a modal expressing ability illustrates how cautious they are, as manifested in ‘Women can do a lot’ and ‘Women can do many things at one time.’ Regarding self-foregrounding, the results revealed that male and female writers preferred to use ‘I’ and ‘my’ more than other self-mentions. However, ‘me’ and ‘we’ (Example 11) were ranked third in males’ and females’ essays, respectively.

-

11.

We need to drive to go to our work and to do our tasks.

(Female for females)

To engage their readers, both groups of readers used ‘you’ more commonly than other markers and ‘we’ came second in writings by males, whereas ‘should’ came after ‘you’ in females’ essays. Further, ‘questions’ were mainly used by male writers. On the other hand, ‘your’ was more frequently used by female writers as an engaging word. Though there was no difference between both groups in terms of the use of engaging resources, female writers preferred to use ‘should’ as a deontic modal (Example 12), and males tended to use questions (Example 13) more often as they wanted to include their readers as participants in the argument (Hyland, 2005). However, they did not expect their readers to confirm their observations or to answer their questions because they assumed that such rhetorical questions tapped into common knowledge. On the other hand, ‘should’ was employed by females to pull readers into discourse at some important points and to refer to common knowledge.

-

12.

Of course, that every capable adult should be allowed to practice one of their basic rights, which is driving.

(Female for females)

-

13.

Why people think that men drive better than women?

(Male for males)

The effect of gender, stance, and topic on writers’ use of interactional metadiscourse markers

As for differences in using metadiscourse markers by the four groups of writers with regard to a certain stance, ANOVA test was used again. Table 7 below illustrates the average number of words used and the standard deviation for each of the four groups of writers. ANOVA test results revealed that there were statistically significant differences between the four groups of writers (P < 0.05) in the number of boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions, and hedging words used in support of their point of view on the topic of driving cars. Nevertheless, no significant difference was found between the four groups in using engagement resources (p > 0.05). This is due to the convergence of the mean values by small differences. Quantitative results are supplemented with qualitative and contextual analysis given in this section.

As illustrated above, Post-Hoc comparison tests showed significant differences between all pairwise groups in their use of attitude markers. In other words, the group of females arguing for male drivers scored the highest mean (i.e. 29.79 ± 10.649), whereas the group of male writers supporting men’s driving scored the lowest (i.e. 13.77 ± 3.943). Results of normalised frequencies also showed that the former group used attitude markers more than others. More specifically, they used attitudinal resources 75,86 times for every 1000 words. As for groups’ utilisation of boosting devices, Post-Hoc comparison tests and ANOVA showed significant differences between all pairwise groups except for the group of females who favoured women’s driving and the other group of female writers arguing for male drivers, as reflected by their mean scores. Results revealed that female writers arguing for female drivers scored higher (i.e. 22.82 ± 7.870) in comparison to the other two groups of male writers. Likewise, significant differences were found between the female group who wrote in support of male drivers (i.e. 20.68 ± 7.959) and the other groups of male writers. On the other hand, the group of males arguing for male drivers scored the lowest mean (i.e. 11.26 ± 4.284) in comparison to the other three groups. Further, there were significant differences between that group and the other group of males arguing for female drivers (15.20 ± 8.691). Results of normalisation confirmed that the group of females writing in favour of females used boosting devices more than others. That is, they used 62,47 boosters in every 1000 words (see Table 8 in the Appendix).

Additionally, Post-Hoc comparison results on the use of hedges by the four groups showed significant differences between all the pairwise groups except for the two groups writing in support of women’s driving because their means are closer to one another. As shown in Table 8 in the Appendix, normalisation results showed that the two groups arguing for men’s driving had nearly similar normalised frequencies estimated to be 34 hedges in every 1000 words. However, in terms of statistically significant differences, the female group arguing for male drivers scored the highest average score (i.e. 13.47 ± 5.348) compared to that of males writing in favour of male drivers who scored the lowest mean (i.e. 7.56 ± 3.676). In other words, there was a significant statistical difference between the two groups (see Table 7).

As for utilising self-mentions by the four groups, normalisation results showed that the two groups who argued for their gender had almost similar normalised frequencies (i.e. 15 self-mentions in every 1000 words). However, Post-Hoc comparison tests showed significant differences between the group of female writers arguing for females and that of male writers writing for males in favour of the former group who obtained a higher average score (i.e. 5.65 ± 3.466). Finally, no Post- Hoc comparison tests were needed for engagement markers because there were no significant differences between the four groups of writers. However, after normalising frequencies, data revealed that the group of males arguing for men’s driving used engagement markers more than others. More specifically, they employed 13,40 markers in every 1000 words.

In general, attitude markers were more common than other metadicourse markers followed by boosters, hedges, self-mentions and finally engaging words in three writing groups (i.e. males writing in support of male drivers, males arguing for female drivers and females writing in favour of males). In other words, in terms of attitudinal lexis, there were 62,61 occurrences per 1000 words in males’ essays arguing for male drivers, 43,09 instances in males’ essays supporting women’s driving, 75,86 examples in females’ essays in favour of male drivers and 61,19 instances per 1,000 words in females’ writing in support of females (see Table 8 in the Appendix). Frequent attitude markers employed by females supporting male drivers are ‘good,’ ‘better,’ ‘even,’ and ‘fast.’ In general, females’ assertive attitude and positive comments are emphasised through their use of positive adjectives such as ‘careful,’ ‘important,’ and ‘fast’ (Example 14).

-

14.

I believe that women are excellent because they are very strict to the rules.

(Female for males)

As for boosting words, there were 51,18 boosters in males’ essays arguing for male drivers, 34,85 examples in males’ writing for females, 52,67 boosting instances in essays by females arguing for males, and 62,47 boosters per 1000 words in essays by females supporting females. However, females arguing for female drivers used boosters more than attitudinal words. The female group of writers writing in favour of Saudi female drivers preferred to use ‘many,’ ‘a lot,’ and ’think’ to show commitment to their viewpoint. On the other hand, the other group of female writers used ‘many,’ ‘all,’ ‘know,’ ‘more,’ and ‘think’ more commonly than other boosters. In general, boosting resources such as ‘many,’ ‘a lot,’ ‘all,’ ‘more,’ etc. are associated with positive comments (Examples 15 and 16). In addition, boosters such as ‘think,’ ‘believe,’ ‘noticed,’ and ‘know’ were used with self-mentions (Example 14).

-

15.

Men drive better than women for many reasons such as confidence, experience and the ability to control the car at difficult situations.

(Female for males)

-

16.

They follow rules more than men.

(Female for females)

Regarding hedging words, there were 34,39 words in essays by males supporting men’s driving, 23,92 instances in essays by males in support of females, 34,31 hedging devices per 1000 words in females’ essays favouring males, and 25,80 instances in essays by females preferring women’s driving. Hedging words such as ‘can,’ ‘some,’ and ‘most’ were more frequently used by the groups writing in support of male drivers (Examples 17 & 18).

-

17.

Men can handle different things better when it comes to driving.

(Female for males)

-

18.

Men can be more used to traffic jams and tough situations over women.

(Male for males)

As for self-mentions, there were 15,97 examples in essays by males for male drivers and 15,47 instances in essays by females for women’s driving. Though normalised frequencies showed no big difference between the two groups, statistical tests revealed that the latter group outperformed the former. Female writers arguing for females employed ‘I,’ ‘my,’ and ‘we’ (Example 19) more frequently, whereas male writers writing for males utilised ‘I,’ ‘my,’ and ‘me’ (Example 20) more than other self-mentions.

-

19.

We need to drive to go to our work and to do our tasks.

(Female for females)

-

20.

In the end and because all what is above I think men are better driver.

(Male for males)

Discussion

The research questions aim at exploring gender differences between EFL male and female writers in using interactional metadiscourse markers. Further, the focus of the present study is on investigating such differences with respect to different viewpoints on a gender-sensitive topic. Generally speaking, since EFL writers argue for a stance and support it with examples and evidence, attitude markers, boosters and hedges are more commonly utilised than other interactional resources. The type of essay, i.e. being an argumentative essay, dictates the type of markers found in students’ essays (El-Dakhs, 2020; Hong and Cao, 2014). Thus, attitude markers are the most commonly used, whereas engagement markers are the least to be employed in argumentative essays. This finding is consistent with that of Puspita and Suhandano’s (2023), Azlia’s (2022), Merghmi and Hoadjli’s (2024) and Alotaibi’s (2018) who note that engaging resources are the least to be used in personal essays, TED Talks, discussion sections in theses and acknowledgements. Apparently, EFL students focus more on expressing their stance with ensured objectivity (Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024) than engaging their readers (El-Dakhs, 2020).

For the first research question, the results reveal that female writers used rhetorical resources of self-mentions, hedges, boosters and attitude markers more significantly than male writers. Such results are inconsistent with previous research by Latif and Rasheed (2020) and Azher et al. (2023), who state that females hedge more than males and males use boosters more than females; Hyland and Tse (2008), who claim that males use hedges and boosters more than females; Alsubhi (2016), who found that Saudi male columnists hedge more than female column writers; and Farahanynia and Nourzadeh (2023), who argue that professional male writers employ self-mentions and boosters more than female writers in applied linguistics. However, such results reflect Pasaribu’s (2017), who notes that females outperform males in their use of hedges and boosters; Puspita and Suhandano’s (2023), who reported that females employ attitudinal resources and boosters more than male writers; Merghmi and Hoadjli’s (2024), who state that female postgraduates employed self-mentions, hedges and attitudinal lexis more than their male counterparts in discussion sections; and Azlia’s (2022), who argues that females used hedges, boosters and attitude markers more than males in TED Talks. Such unexpected results can be attributed to the changes that affected the role of Saudi women as they have been given more voice and power recently. Apparently, Saudi female writers want to confirm their presence and visibility in the argument through common use of self-foregrounding devices and attitudinal resources (Fendri, 2020; Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024).

Heavy use of attitude markers, hedges, boosters and personal markers indicates a more personalised style of writing that is mainly associated with female writers (cf. Holmes, 1988). Further, after the Saudi Vision with its emphasis on women empowerment, women became bolder in arguing for their rights. Therefore, they used boosters more significantly than male writers to reinforce their point of view and employed positive attitude markers (e.g. good, better, careful, etc.) to emphasise praise of their own ability in driving (Herbert, 1990; Johnson and Roen, 1992).

It is important to note that females’ personalised style has been reinforced by their significant use of self-mentions (D’angelo, 2008) such as ‘I,’ ‘my,’ and ‘we.’ As opposed to males who employed ‘I,’ ‘my,’ and ‘me’ more commonly than other personal markers, Saudi female writers included themselves and other females to voice their opinion through the use of ‘we’ for the purpose of promoting solidarity (Alotaibi, 2018; Aziz et al., 2016). This also manifests that female writers want to convey a sense of togetherness, selflessness and cooperation (Aziz et al., 2016; Mason, 1994) to the reader, while males prefer to express an aura of authority and dominance by distancing themselves from their reader (Mulac et al., 2001).

Focusing on boosters, both groups of males and females preferred to employ boosters that strengthen a common belief through using ‘all’ and ‘think’ more than those showing solidarity (i.e. shared knowledge with the reader) such as ‘really,’ ‘actually,’ and ‘certainly,’ which are chiefly used by females. Using belief boosters indicates that both groups are convinced of their arguments. Such results contradict Mokhtar et al.’s (2021) and Holmes’ (1990) who note that males show some tendency towards boosters of solidarity. In this study, female writers are more forceful in emphasising their claims and more conscious of their readers. Additionally, as stated above, ‘think’ has been used more frequently by writers of both genders to reinforce one’s point of view. However, ‘think’ has occurred mainly with self-mentions in males’ academic essays as Saudi males establish themselves as credible sources of the driving experience and hence highlight their confidence in a judgement (Hyland and Tse, 2008; Mulac et al., 2001). On the other hand, ‘think’ is also associated with ‘people,’ ‘many,’ ‘they,’ etc. in females’ writing because female writers are more aware of others’ points of view and critiques and they are ready to refute them. In addition, they present their argument with a higher degree of assurance using belief boosters such as ‘prove’ and ‘show.’ Boosters used by females are generally associated with positive comments as highlighted by Hyland and Tse (2008). However, females’ heavy use of hedges indicates that the information discussed is presented as opinions and hence they are legible for negotiation and discussion. They respect their readers and they do not want to impose their point of view on them (Ahmed and Maros, 2017; Farahanynia and Nourzadeh, 2023; Hyland, 2005; Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024). In general, females are more cautious (Fendri, 2020; Lakoff, 1973; Zare-ee and Kuar, 2012) and indirect in voicing their opinions.

As for the second question that is concerned with the effect of gender and the chosen stance on the distribution of interactional metadiscourse markers in students’ essays, the results show that a gender-sensitive topic can play a role in determining which rhetorical resources should be used the most for which stance. As reported above, the two groups of females arguing for women’s driving and men’s driving used boosters and attitude markers more significantly than the two male groups. On the other hand, the group of males writing in favour of their driving scored the least in terms of boosters and attitudes. However, the female group writing in favour of males outperformed others in terms of hedges. Further, there is no significant difference between the four groups with regard to engagement markers. More importantly, females preferring women’s driving employed self-mentions more significantly than males arguing for their driving.

Females’ significant use of boosters can be justified in terms of their desire to emphasise praise (Herbert, 1990; Johnson and Roen, 1992). Thus, boosting resources are associated with positive comments on both genders’ ability in car driving. Further, female writers used boosters more commonly with self-mentions. Apparently, female writers establish themselves as experienced individuals whose views are valued and well-considered. They are being firm in voicing their opinions regardless of which point of view might be pervasive among others. Though they are not the seniors in the field of car driving, Saudi females are more empowered nowadays and they are ready to follow an uncompromising approach no matter how the proponents of the opposite team think of them. Hence, females’ attitude is reflected in their use of positive adjectives such as ‘careful’ and ‘important.’

More importantly, the male group arguing for female drivers used boosters and attitudinal resources more than the other group of male writers to emphasise their stance. They believe that Saudi women are in need of support from males in particular. This indicates that such male drivers are aware of the opposition and the refutation they might encounter from other males. On the other hand, the group of male writers arguing for male drivers used the least of boosters and attitude markers because they believe that in a Middle Eastern society, they do not have to be that assertive in presenting their arguments. In fact, the majority of males and a great proportion of females support men’s driving. Compared to doing housework and taking care of children, driving cars is one of the tasks that traditionally belongs to the masculine domain and where men can demonstrate acts of manliness. Moreover, in Saudi Arabia, driving schools are basically operated by men and they shape its requirements. Thus, writers arguing for females are encouraged to present their arguments in a forceful manner (cf. Hyland and Tse, 2008).

Previous research (cf. Hyland and Tse, 2008) indicates that there is no direct relationship between gender and language and that topic or discipline dictates the projection of a specific identity. Similarly, in this research, hedges are not commonly used by females, whereas boosters are not frequently employed by males. Hence, females’ significant use of hedges in arguing for the opposite-gender members may suggest some correlation between language and stance. Some Saudi females arguing for men and overusing hedges as a result might be accustomed to being driven by their male family members. Their cautious nature and reluctance have been manifested through the use of hedges (Zare-ee and Kuar, 2012). Females’ exploitation of ‘can,’ as a modal of ability, is mainly used to refer to males’ capability in multitasking, controlling cars, concentrating, etc.; things that some female writers doubt women can do. Females arguing for males are tempted to project this gender identity as it is culturally typical and expected of them. They feel insecure and have to voice their opinion indirectly (Albaqami, 2017; Merghmi and Hoadjli, 2024). Additionally, males arguing in favour of their ability employed hedges more than the other group of male writers. This finding goes somewhat in line with Tse and Hyland’s (2008) who state that male reviewers tend to write more critical reviews and hedge if the author is a male. Further, the sensitivity of the topic and how personal it can be prompt males to use more hedges (Azizah, 2021). One may conclude that writers of both genders may tend to be cautious when they argue for or against males, as males are stereotyped to play dominant roles in society including academia and handling some tasks.

More importantly, the significant difference between females arguing for themselves and males writing in favour of their driving in their use of self-mentions is a bit surprising. It seems that females adopt a more personalised style especially when they argue for themselves and their rights. They want to sound firm in voicing their opinions (Hyland and Tse, 2008). On the other hand, males want to be objective (Alsubhi, 2016), and thus they do not need to use self-mentions in arguing for themselves. This shows their confidence and trust in their audience whose common knowledge will help them validate their arguments. Hence, they used engagement resources more than the other groups.

In general, in Saudi Arabia, driving cars as a task has been mainly associated with Saudi males for years. It is a sensitive topic for both genders. As Saudi females are pressurised to prove their ability in driving cars through the use of boosting devices and attitude markers, males do not feel the same pressure, and thus they do not employ a lot of boosters and attitudinal lexis to prove their point. More importantly, based on this research and previous studies, there is no specific stance marker that typically describes males’ or females’ language. Language users lean towards projecting a specific type of identity with respect to a certain discipline, topic, or stance. In argumentative writing, the use of metadiscourse resources is determined by whom you argue for and against.

Conclusion

The present study aims at bridging the gap and examines the effect of a gender-sensitive topic on Saudi EFL undergraduates’ use of metadiscourse markers in their argumentative writing. The results of the current study show that female writers used attitude markers, followed by boosters and hedges and finally self-mentions more than male writers. As for stance choice as a variable, it has been proven that it can influence one’s use of metadiscourse resources. The female group advocating men’s driving outperformed others in terms of hedges. However, one cannot attribute the use of hedges to females and that of boosters to males. Previous studies on the use of metadiscourse resources by both genders reveal unpredictable results. In fact, the use of one type of interactional markers by one gender is dependent on the type of topic and stance writers adopt.

Limitations and recommendations

Since this study explores the distribution of metadiscourse markers in Saudi students’ essays about a gender-sensitive topic, there are a number of limitations that should be considered in future research. First, the corpora utilised for discourse analysis are relatively small, especially the one written by male students arguing in support of females. This is mainly attributed to the fact that a few males support women’s driving. Further, the number of male students registering for the course is smaller than that of female students. Additionally, some students in some groups did not write 400 words in an essay but less. Second, only one institutional setting was selected for corpus compilation, namely King Saud University. A third limitation is that data collection was limited to one genre (i.e. argumentative writing), one gender-sensitive topic (i.e. the superiority of which gender in driving cars), and one age group. Therefore, future research should assess metadiscourse use in larger corpora containing larger pieces of writing and with different variables. Further, other institutional settings can be considered to account for cultural or regional differences. It is also possible to investigate other genres, including spoken genres, in particular debates on similar topics. In addition, metadiscourse analysis of argumentative writing by senior citizens of both genders would reveal different results. Considering that essays were collected from students under exam conditions, more relaxed settings would perhaps produce different essays than those written under time constraints and for grading purposes.

Suggestions for future research

Previous studies state that there are no certain rhetorical resources expected of one gender. Based on this study and previous research, a certain type of discourse and a specific group of topics with their respective stances dictate the kinds of rhetorical resources that should be used in writing to project a specific identity. Thus, future research is ought to explore the effect of other gender-sensitive topics on students’ writing, especially if such students live in a community where one does not expect 100% agreement on one stance. Similar topics addressing one gender’s capability in handling a specific task (e.g. occupying a leadership position) are still debatable, especially among Saudis (Alanazi et al., 2023). Moreover, as some have investigated the distribution and frequency of metadiscourse markers by writers of reviews of both genders across two disciplines, it would be insightful if further research examines reviews written on books of different topics if the gender of the professional book writer is revealed or hidden from the reviewer. In addition, some emphasise the significance of topic choice on the use of metadiscourse markers; thus, it would be enlightening if researchers examine the effect of choosing a gender-sensitive topic and one that is not addressing gender on writers’ use of metadiscourse resources. Further, it is recommended to explore how metadiscourse markers are employed by opinion columnists of both genders writing about women driving before and after ban lifting in 2017, as previous research shows that the type of genre determines which metadiscourse resources should be used the most by writers in support of their viewpoint. Moreover, the use of interactional metadiscourse markers in essays on a gender-sensitive topic can be explored across languages in translated or untranslated essays, as some (Alotaibi, 2018; Gholami et al., 2014) point out the Arabs do not use many interactional resources in Arabic as they do when they write in English. Thus, the role of L1 interference and cultural restrictions should be explored because Arab females are expected to hedge when they voice their opinions. However, culturally speaking, Arabs are advised to be direct when they argue for or refuse something (Alghazo et al., 2021; El-Dakhs et al., 2021). In general, since the present study proves that statistical tests can reveal significant differences in students’ use of metadiscourse rhetorical resources, it would be intriguing if future research utilises statistical measures besides normalised frequencies to draw defensible conclusions.

Pedagogical implications of the study

The findings of this study have significant implications for EFL instructors, syllabus designers and curriculum developers. They brought to our attention the significance of metadiscourse resources and the pressing need to support EFL students in gaining rhetorical knowledge in order to improve the quality of their argumentative academic writing. Saudi female writers are given more voice and power than before. However, their overuse of hedges when they argue for men’s driving denotes a less assertive nature. In light of this, the pragmatic functions of metadiscourse markers should be explicitly taught in EFL courses. Saudi EFL students should be taught how to argue effectively using boosters and attitude markers. Additionally, syllabus designers and learning material creators should think about adding metadiscourse markers to learning materials or presenting authentic English texts to students to assist them in projecting their views efficiently.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Ahmed WK, Maros M (2017) Using hedges as relational work by Arab EFL students in student-supervisor consultations. GEMA Online J Lang Stud 17(1):89–105. https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2017-1701-06

Alanazi R, AlHugail M, Almeshary T (2023) What are the attitudes towards changing gender roles within the Saudi family? J Inter Women’s Stud 25(2):1–12

Albaqami SES (2017) How grasping gender-related aspects of speech is increased by multi-modal text analysis–a case study. Asian J Sci Tech 8(11):6611–6614

Alexander JP, Spencer B, Sweeting AJ et al. (2019) The influence of match phase and field position on collective team behaviour in Australian Rules football. J Sports Sci 37(15):1699–1707. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1586077

Alghazo S, Al-Anbar K, Altakhaineh AR, Jarrah M (2023) First language and second language English editorialists’ use of interactional metadiscourse. Disc Inter 16(2):5–28. https://doi.org/10.5817/DI2023-2-5

Alghazo S, Al Salem MN, Alrashdan I (2021) Stance and engagement in English and Arabic research article abstracts. System 103:102681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102681

Alotaibi HS (2018) Metadiscourse in dissertation acknowledgments: exploration of gender differences in EFL texts. Edu Sci Theory Pract 18(4):899–916

Alqahtani SN, Abdelhalim SM (2020) Gender-based study of interactive metadiscourse markers in EFL academic writing. Theory Pract Lang Stud 10(10):1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1010.20

Alsubhi AS (2016) Gender and metadiscourse in British and Saudi newspaper column writing: male/female and native/non-native differences in language use. Dissertation, University College Cork

Altman DG, Bland JM (1995) Statistics notes: the normal distribution. BMJ 310(6975):298

Al-Zubeiry HYA, Assaggaf HT (2023) Stance-marking of interaction in research articles written by non-native speakers of English: an analytical study. Stud Eng Lang Edu 10(1):235–250. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v10i1.26648

Anthony L (2022) AntConc (Version 4.0.5) [Computer software]. Waseda University. Tokyo. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software. Accessed 29 Dec 2021

Ardhianti M, Susilo J, Nurjamin A et al. (2023) Hedges and boosters in student scientific articles within the framework of a pragmatic metadiscourse. J Lang Lang Teach 11(4):626–640. https://doi.org/10.33394/jollt.v11i4.9018

Asadi J, Aliasin SH, Morad-Joz R (2023) A study of the research article discussion section written by native authors: Hyland’s (2005) metadiscourse model in focus. Res Eng Lang Pedag 11(1):121–137

Assassi T (2023) Metadiscourse in academic abstracts written by Algerian, Saudi, and native English researchers. In: Bailey K, Nunan D (eds) Research on English language teaching and learning in the Middle East and North Africa. Routledge, London, pp 131–143. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003312444-13

Assassi T, Merghmi K (2023) Formulaic sequences and meta-discourse markers in applied linguistics research papers: a cross-linguistic corpus-based analysis of native and non-native authors’ published articles. Acad Inter Sci J 14(27):154–175. https://doi.org/10.7336/academicus.2023.27.10

Azher M, Jahangir H, Mahmood R (2023) Constructing gender through metadiscourse: a corpus-based inter-disciplinary study of research dissertations of Pakistani M. Phil graduates. CORPORUM J Corpus Ling 6(2):81–101

Aziz RA, Jin C, Nordin NM (2016) The use of interactional metadiscourse in the construction of gender identities among Malaysian ESL learners. 3L Southeast Asian J Eng Lang Stud 22(1):207–220. https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2016-2201-16

Azizah DN (2021) Hedges function in masculine and feminine feature’s language: a pragmatics analysis. J Prag Res 3(1):59–69. https://doi.org/10.18326/jopr.v3i1.59-69

Azlia SC (2022) Interactional discourse of male and female motivational speech in TED Talks: a corpus-based study. Rainbow J Lit Ling Cult Stud 11(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.15294/rainbow.v11i1.54777

Bazerman C (2009) Genre and cognitive development: beyond writing to learn. Pratiq (143–144): 127–138. https://doi.org/10.4000/pratiques.1419

BBC (2017) Saudi women are officially allowed to get behind the wheel, after a decades-old driving ban was lifted. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-44576795. Accessed 20 Jan 2022

Biber D (2006a) Stance in spoken and written university registers. J Eng Acad Purp 5:97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2006.05.001

Biber D, Finegan E (1989) Styles of stance in English: lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and affect. Text Talk 9:124–193. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1989.9.1.93

Biber D, Zhang M (2018) Expressing evaluation without grammatical stance: informational persuasion on the web. Corpora 13(1):97–123. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2018.0137

Byrnes H, Manchón RM (eds) (2014) Task-based language learning—insights from and for L2 writing. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1075/tblt.7

Chafe WL, Nichols J (1986) Evidentiality: the linguistic coding of epistemology. Ablex, New Jersey

Cohen J (1988) Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl Psycho Meas 12(4):425–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168801200410

Crismore A (1989) Talking with readers: metadiscourse as rhetorical act. Peter Lang, New York

D’angelo L (2008) Gender identity and authority in academic book reviews: an analysis of meta discourse across disciplines. Linga e Filol 27:205–221

El-Dakhs DA (2020) Variation of metadiscourse in L2 writing: focus on language proficiency and learning context. Ampersand 7:100069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2020.100069

El-Dakhs DAS, Alhaqbani JN, Adan S (2021) Female university teachers’ realizations of the speech act of refusal: cross-cultural and interlanguage perspectives. Ling Cult Rev 5(S2):1308–1328. https://doi.org/10.21744/lingcure.v5nS2.1821

Elliott AC, Woodward WA (2007) Statistical analysis quick reference guidebook: with SPSS examples. Sage, New Castle. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985949

Farahanynia M, Nourzadeh S (2023) Authorial and gender identity in published research articles and students’ academic writing in applied linguistics. Iran J Appl Lang Stud 15(1):117–140

Fendri E (2020) A comparative analysis of identity construction in digital academic discourse: Tunisian EFL students as a case study. Chang Pers Acad Genres 9:75–101

Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS: book plus code for E version of text, vol 896. British Library, London

Gholami J, Nejad SR, Pour JL (2014) Metadiscourse markers misuses: a study of EFL learners’ Argumentative Essays. Procedia-Soc Beh Sci 98:580–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.454

Halliday MAK (1994) An introduction to functional grammar, 2nd edn. Edward Arnold, London and Melbourne

Handayani A, Drajati NA, Ngadiso N (2020) Engagement in high-and low-rated argumentative essays: interactions in Indonesian students’ writings. Indones J Appl Ling 10(1):14–24. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v10i1.24957

Harris Z (1959) The transformational model of language structure. Anthro Ling 1(1):27–29

Herbert RK (1990) Sex-based differences in compliment behaviour. Lang Soc 19:201–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500014378

Holmes J (1988) Paying compliments: a sex-preferential politeness strategy. J Prag 12(4):445–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(88)90005-7

Holmes J (1990) Apologies in New Zealand English. Lang Soc 19(2):155–199

Hong H, Cao F (2014) Interactional metadiscourse in young EFL learner writing: a corpus-based study. Int J Corpus Ling 19(2):201–224. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.19.2.03hon

Hunston S, Thompson G (2000) Evaluation in text: authorial stance and the construction of discourse. Oxford University, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198238546.001.0001

Hyland K (1998) Hedging in scientific research articles. John Benjamins, Amesterdam/Philadelphia. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.54

Hyland K (1999) Disciplinary discourses: writer stance in research articles. In: Candlin H, Hyland K (eds) Writing: texts, processes and practices. Longman, London, p 99–121. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315840390-6

Hyland K (2000) Hedges, boosters and lexical invisibility: noticing modifiers in academic texts. Lang Aware 9(4):179–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410008667145

Hyland K (2005) Metadiscourse: exploring interaction in writing. Continuum, New York

Hyland K, Tse P (2008) ‘Robot Kung fu’: gender and professional identity in biology and philosophy reviews. J Prag 40(7):1232–1248

Jabeen I, Almutairi HSS, Almutairi HNH (2023) Interaction in research discourse: a comparative study of the use of hedges and boosters in PhD theses by Australian and Saudi writers. World J Eng Lang 13(8):119–129. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v13n8p119

Johnson D, Roen D (1992) Complimenting and involvement in peer reviews: gender variation. Lang Soc 21:27–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500015025

Jones JF (2011) Using metadiscourse to improve coherence in academic writing. Lang Edu Asia 2(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/11/V2/I1/A01/JFJones

Khattak SY, Ahmad MS, Arshad K (2023) Involving and persuading discourse consumers: a longitudinal critical discourse analysis of the engagement strategies in the Pakistani English newspaper editorials. Harf -o-Sukhan 7(4):237–246

Krippendorff K (2004) Reliability in content analysis: some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum Com Res 30(3):411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

Lakoff R (1973) Language and woman’s place. Lang Soc 2(1):45–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500000051

Latif F, Rasheed MT (2020) An analysis of gender differences in the use of metadiscourse markers in Pakistani academic research articles. Sci Inter 32(2):187–192

Lee J, Deakin L (2016) Interactions in L1 and L2 undergraduate student writing: interactional metadiscourse in successful and less-successful argumentative essays. J Sec Lang Writ 33:21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.06.004

Macintyre R (2013) Lost in a forest all alone: the use of hedges and boosters in the argumentative essays of Japanese university students. Sophia Inter Rew (35), 1-24

Mahmood R, Javaid G, Mahmood A (2017) Analysis of metadiscourse features in argumentative writing by Pakistani undergraduate students. Inter J Eng Ling 7(6):78–87. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v7n6p78

Martin JR (2000) Beyond exchange: appraisal systems in English. In: Hunston S, Thompson G (eds) Evaluation in text: authorial stance and the construction of discourse, Oxford University, Oxford, pp 142–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198238546.003.0008

Mason ES (1994) Gender differences in job satisfaction. J Soc Psycho 135:143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1995.9711417

Merghmi K, Hoadjli AC (2024) The use of interactional metadiscourse markers in the discussion section of master’s theses written in English by Algerian students: an investigation of gender variation. Jordan J Mod Lang Lit 16(1):75–94

Mokhtar MM, Hashim H, Khalid PZM et al. (2021) A comparative study of boosters between genders in the introduction section. Arab World Eng J 12(1):515–526. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no1.33

Morris L (1998) Differences in men’s and women’s ESL writing at the junior college level: consequences for research on feedback. Can Mod Lang Rev 55(2):219–238. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.55.2.219

Mulac A, Bradac JJ, Gibbons P (2001) Empirical support for the gender-as culture hypothesis. An intercultural analysis of male/female language difference. Hum Com Res 27:121–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/27.1.121

Pallant J (2020) SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. McGraw-Hill, UK. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117452

Papangkorn P, Phoocharoensil S (2021) A comparative study of stance and engagement used by English and Thai speakers in English argumentative essays. Inter J Ins 14(1):867–888. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14152a

Park S, Oh SY (2018) Korean EFL learners’ metadiscourse use as an index of L2 writing proficiency. SNU J Edu. Research 27(2):65–89

Pasaribu TA(2017) Gender differences and the use of metadiscourse markers in writing essays. Inter J Human Stud 1(1):93–102. https://doi.org/10.24071/ijhs.v1i1.683

Pearson WS, Abdollahzadeh E (2023) Metadiscourse in academic writing: a systematic review. Lingua 293:103561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103561

Peng JE, Zheng Y (2021) Metadiscourse and voice construction in discussion sections in BA theses by Chinese university students majoring in English. SAGE Open 11(2):21582440211008870. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211008870

Puspita SR, Suhandano (2023) Gender-based language differences in personal essays: a case study of personal essays in Chicken Soup for The Souls Series. Dissertation, Universitas Gadjah Mada

Rabab’ah G, Yagi S, Alghazo S (2024) Using metadiscourse to create effective and engaging EFL virtual classrooms during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Iran J Lang Teach Res 12(1):107–129

Richards CJ, Schmidt R (2002) Longman dictionary of language teaching & applied linguistics. Pearson Education, London

Ruxton GD (2006) The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. Beh Eco 17(4):688–690

Ruxton GD (2010) The design and analysis of experiments in ecology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford