Abstract

The development of rural e-commerce in China is viewed as an opportunity to increase rural income. Using panel data from 592 national-level key poverty-stricken (NLKPS) counties from 2014 to 2020, we confirm that the National Rural E-commerce Comprehensive Demonstration Project (NRECDP), launched by the Chinese government, delivers significant rural income growth for selected counties by providing financial support. Digital inclusive finance has facilitated rural e-commerce development, thereby promoting rural income. Our study uses the endogeneity switching regression (ESR) model to address self-selection bias and finds that NRECDP participation increases rural income by ~12.97%. The determinants of participation in the NRECDP include levels of economic development, e-commerce development, infrastructure development, industry structure, and digital inclusive finance. Additionally, the determinants of rural income include education levels and population density. Moreover, our heterogeneity analysis reveals that the rural income growth effect of NRECDP involvement is more significant for NLKPS counties in non-ethnic regions, central regions, higher industry structures, and the three regions and three prefectures. Additionally, entrepreneurship serves as a potential channel linking NRECDP implementation and rural income growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rural e-commerce represents a novel form of regional development driven by digital platforms and technologies in rural areas (Wei et al., 2020). It eliminates geographical constraints, reduces transaction costs, and connects rural producers directly with consumers (Couture et al., 2021). Additionally, it unlocks the off-farm income-generating potential of rural areas, enabling participation in the digital economy and access to expanded market opportunities.

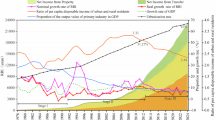

To promote rural e-commerce development, the government launched the National Rural E-commerce Comprehensive Demonstration Project (NRECDP) in 2014, providing financial support to selected counties. The application process is standardized at the provincial level, and counties with a robust rural e-commerce foundation are selected based on merit. Additionally, the willingness of local governments and the endowments of agricultural resources are thoroughly considered. Government statistics show that the NRECDP encompassed all national-level poverty-stricken counties, with rural e-tailing increasing from 180 billion yuan to 1.7 trillion yuan by 2019.

Then, previous studies have predominantly investigated the impact of rural e-commerce on rural income growth (Couture et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2018; Luo and Niu, 2019), income inequality (Zhang et al., 2022), poverty alleviation (Peng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019), or the rural-urban income gap (Yin and Choi, 2022; Xiong et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2022). Additionally, some studies have explored the impact of digital inclusive finance on rural e-commerce or poverty alleviation (Xiong et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). However, the self-selection nature of NRECDP participation has been overlooked in previous studies, resulting in self-selection bias.

Furthermore, digital inclusive finance, which encompasses digital payments, investments, and financing (Li et al., 2023), has not been recognized as a determinant influencing participation in the NRECDP. It provides significant benefits for the advancement of rural e-commerce by supplying initial capital for rural residents to start businesses, thereby fostering new entrepreneurial opportunities in e-commerce. Additionally, it alleviates financial constraints among rural inhabitants, stimulating rural consumption and investment, and ultimately bolstering rural economic growth (Sun and Zhu, 2022; Xiong et al., 2022). Therefore, to comprehensively assess the efficacy of NRECDP policies, recognizing the role of digital inclusive finance is crucial.

Thus, our study offers several contributions in comparison to existing studies. First, we employ the endogeneity switching regression (ESR) model to control for self-selection bias resulting from unobserved variables, analyzing whether participation in the NRECDP can increase rural income in national-level key poverty-stricken (NLKPS)Footnote 1 counties, the determinants of each county’s participation, and whether there are significant heterogeneous income growth effects in terms of ethnic regions, the three regions an three prefectures or geographic location and industry. Finally, we examine whether NLKPS counties can increase rural residents’ income through a policy tool encouraging rural e-commerce development. This also helps confirm whether rural e-commerce development is a tool to solidify poverty alleviation.

Our findings confirm that participation in the NRECDP increases rural incomes in NLKPS counties. According to the treatment effect analysis, the income growth effect of participation in the NRECDP is ~12.97%. Furthermore, the determinants significantly influencing each NLKPS county’s selection for the NRECDP include levels of economic development, e-commerce development, infrastructure development, industry structure, and digital inclusive finance. Additionally, determinants of rural income include education levels and population density. Finally, our results reveal that the income growth effects of NRECDP participation are more significant in non-ethnic regions, the three regions, and three prefectures, where rural income growth exceeds the overall average level of 592 NLKPS counties. In the mechanism analysis, we find that entrepreneurship serves as a potential channel linking rural e-commerce development and rural income growth.

Literature review

The concept of rural e-commerce involves e-commerce activities related to agriculture and rural residents. It includes the movement of industrial products to rural areas, agricultural products to urban areas, the e-commerce of agricultural materials, and the e-commerce of poverty alleviation and rural services (Li and Zhao, 2020). It is viewed as an opportunity to increase rural income in developing countries (Liu et al., 2021). The rise of rural e-commerce in China presents a potential solution for sustainable rural development (Leong et al., 2016; Haji, 2021; Han and Li, 2021). It has become crucial for targeted poverty alleviation (Gao, 2022).

Rural e-commerce, as a new form of regional development based on online platforms, has emerged to overcome geographical barriers in rural areas (Wei et al., 2020). It is an ideal channel for rural residents to overcome initial market segmentation and connect more fully to the larger market. In addition to overcoming geographic hurdles, it addresses fundamental constraints of the rural economy. In terms of factor mobility, rural e-commerce simplifies the exchange of resources between rural and urban areas. Online marketplaces support the growth of agricultural product sales, innovating supply and demand patterns of various products and resources in rural areas. It motivates rural residents to enhance their income levels by participating in the industrial chain. Additionally, it enhances the rural commodity circulation system, facilitating the flow of agricultural and urban industrial products. Consequently, it serves as an effective pathway out of poverty (Li and Qin, 2022).

Furthermore, rural e-commerce can strengthen the rural industrial structure by shifting from an agriculture-centric paradigm to a business services-oriented model, thereby establishing a comprehensive industrial chain (Zhang et al., 2022). Its development also upgrades supply chains in rural areas, improving services by reducing trade costs, increasing market access, and using big data and digital technology to achieve on-demand production or enhance product quality (Luo and Niu, 2019). It also propels conventional agriculture towards intensive, standardized, and large-scale production, including efforts to cultivate distinct industrial zones with unique attributes and key production areas, fostering several influential county brands. These efforts facilitate the transition and advancement toward contemporary agriculture, ultimately promoting rural income.

Consequently, the government places significant importance on the development of rural e-commerce. In 2014, the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Finance initiated a comprehensive demonstration of rural e-commerce by selecting eight provinces—Heilongjiang, Hebei, Hubei, Anhui, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Henan—and seven counties from each province as pilot areas. The selection criteria for pilot counties included a robust e-commerce foundation, a highly motivated local government, and geographic distribution across the East, Central, West, and Northeast regions to ensure a comprehensive demonstration experience for national promotion.

By 2019, the NRECDP in rural areas covered all NLKPS countiesFootnote 2 (China Daily, 2021.08.26). The NRECDP primarily focuses on enhancing the capacity to develop rural e-commerce in poverty-stricken areas, supported by government fiscal subsidies. These subsidies must be invested in projects promoting rural e-commerce, including rural product marketing, public service system improvements, and training rural e-business personnel. Its goals include encouraging more rural residents to participate in e-commerce, expanding marketing channels for rural products, and enabling poverty-stricken areas to leverage their resource endowments (Peng et al., 2021).

Numerous previous studies have focused on the income growth impact of the NRECDP (Chen et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2021; Qin and Fang, 2022). However, the determinants of participation in the NRECDP are rarely further observed. As previously mentioned, counties with a better foundation are more likely to be chosen. However, the evaluation of foundations should consider multiple perspectives, including infrastructure, human capital, industrial foundations, financial conditions, and so on.

Particularly with regard to financial condition, traditional inclusive finance is losing its efficiency and viability due to issues such as fragmented network institutions, restrictions by time and geographical distance, single products, and high application thresholds (Ding et al., 2022). Conversely, digital inclusive finance, as a new economic model that includes digital payments, investments, and financing, offers numerous benefits (Li et al., 2023). It targets low-income and disadvantaged groups, reducing the marginal cost of financial services and expanding their coverage through information technology.

Digital inclusive finance could offer new ways for rural residents to access financial services, simplify business processes, enhance savings mobilization, expedite rural capital formation and accumulation, provide financial support for rural enterprises, reduce financing constraints for farmers and enterprises, stimulate rural consumption and investment, and increase rural residents’ marginal propensity to consume, leading to a shift towards new production methods (Sun and Zhu, 2022; Xiong et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). It is also associated with business opportunities and the entrepreneurial behaviors of rural residents with low physical or social capital. The growth of digital payments and microfinance can enhance rural suppliers’ chances of opening online retail businesses (He et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020). Furthermore, digital inclusive finance can improve resource allocation in rural areas and alleviate the imbalance between urban and rural development. By reducing information asymmetry in financial transactions, it mitigates inequality between supply and demand and resource mismatch in the financial market, ultimately realizing the flow and full utilization of financial resources for rural areas and low-income individuals (Sun and Zhu, 2022).

However, digital inclusive finance also has some shortcomings. For instance, due to the lower actual lending rate of rural e-commerce participants, they often can only afford higher costs. Additionally, digital inclusive finance may encounter higher interest rates, increased risks, and an imbalance between supply and demand. Moreover, rural areas are relatively underdeveloped in aspects such as digital infrastructure, financial environment, and financial literacy, making it difficult for them to obtain funds through digital inclusive finance (Ge et al., 2022; He et al., 2022; Charlery et al., 2016). Finally, financial institutions face numerous compliance and policy risks, causing rural residents to resist using digital inclusive finance (He et al., 2022). These factors may hinder the development of rural e-commerce through digital inclusive finance.

In short, self-selection biased problem-solving and analysis of a range of economic factors affecting participation policies are important issues to be addressed in our study, which have been largely overlooked in previous studies.

Methodology and data

Study region and representativeness

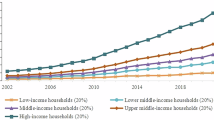

NLKPS counties are defined based on the average annual net income of the local population as announced by the Office of the Leading Group for Poverty Alleviation and Development in China in 2012 is less than 2300 RMB per capita per year, with even lower thresholds for minority and old revolutionary areas. These counties are concentrated in the central and western regions, particularly in old revolutionary areas, ethnic minority areas, and border regions. However, the criteria have changed over time, leading to some countries being withdrawn from national support.

The list of NLKPS counties has undergone several adjustments over the years. The initial list, confirmed in 1986, included 331 counties. The first adjustment in 1994 increased the number to 592 and renamed them National Key Counties for Poverty Alleviation and Development. The third adjustment in 2011 maintained the total at 592 but altered the selection of 38 key counties. On November 23, 2020, all NLKPS counties in China were declared lifted out of poverty, and the NLKPS county support system was officially abolished. The regional distribution as of 2012 is detailed in Table 1.

NLKPS counties will receive heightened attention from local governments at all levels, with a focus on promoting industrialized construction. Benefiting from central financial funds for poverty alleviation, the government will offer various forms of assistance. For instance, the more developed eastern regions support the western areas through initiatives like the “East-West Poverty Alleviation Collaboration” and labor transfer training programs, such as the “Rain Dew Program.” Additionally, large enterprises, schools, and public welfare organizations prioritize poor counties for various types of support under the umbrella of “social poverty alleviation.” Concurrently, the state offers preferential policies to students in impoverished areas to promote educational advancement as a means of escaping poverty.

Empirical model

Generally speaking, individual observations often result from selection, such as whether to join an organization or not. Since only the individual’s choice behavior and the result of choice can be observed, directly regressing the decision variable on the outcome variable may lead to endogeneity problems due to missing variables. The endogenous switching regression (ESR) model addresses this issue by using switching equations to mitigate the impact of endogeneity.

It is used to solve self-selection bias when estimating the income impacts of participation in the NRECDP, examining the determinants of NRECDP participation and its income impact on farmers from NLKPS counties. While Propensity Score Matching is used to address selection bias, it cannot handle self-selection bias resulting from unobserved factors. The ESR model incorporates instrumental variables and counterfactual analysis to address self-selection bias and unobserved factors (Liu et al., 2021).

The basic conceptual framework assumes that the NLKPS county either participates in the NRECDP or does not. Participation in the NRECDP allows an NLKPS county to receive fiscal support from the central government, which promotes rural consumption, reduces logistics costs, boosts agricultural e-tailing growth, facilitates the flow of agricultural products into cities and industrial products into the countryside, and helps farmers increase income. It is important to note that participation in the NRECDP is the result of each county’s self-selection based on its specific conditions.

Where \({{\rm{NRECDP}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) takes the value of 1 if the NLKPS county i participates in the NRECDP and 0 otherwise; \({{\rm{Z}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is a vector of characteristic factors influence the choice of participating in the NRECDP, such as infrastructure (Internet and transportation), socioeconomic characteristics etc (Liu et al., 2020). \({{\rm{\beta }}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is a vector of unknown parameters to that need to be estimated; and \({{\rm{u}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is an error term. Accordingly, the following separate outcome equations for rural income with participation and non-participation in the NRECDP are specified:

Regime 1: rural income from National-level key poverty-stricken county i with participation in the NRECDP

Regime 2: rural income from National-level key poverty-stricken county i with non-participation in the NRECDP

Where \({{\rm{Y}}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{Y}}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) indicate rural income from NLKPS county i which participates in the NRECDP and not, respectively. \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) are vectors of exogenous variables that may affect rural income from NLKPS county with participation with the NRECDP or not; Random disturbance terms \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) are linked to the outcome variables. While it is permitted for variables \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) in the outcome Eqs. (2.1) and (2.2) and \({{\rm{Z}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) in the selection equation to overlap. In this instance, outcome Eqs. (2.1) and (2.2)‘s explanatory variables are combined with one instrumental variable to estimate the selection Eq. (1). The valid instrumental variable should affect participation in the NRECDP but does not affect the rural income of NLKPS counties (Liu et al. 2021).

All disturbance terms satisfy the joint normal distribution with zero mean and the moments of correlation coefficients are as follows:

Where \({{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{u}}}^{2}\) indicates the variance of the selection Eq. (1)’s error term; \({{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\) and \({{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{np}}}^{2}\) are the the variances of the outcome Eqs. (2.1) and (2.2)’s error terms; \({{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{pu}}}\) is a covariance of \({{\rm{u}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) and \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\), and \({{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{npu}}}\) is a covariance of \({{\rm{u}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) and \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\). Note that \({{\rm{Y}}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{Y}}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) are not observed simultaneously, which implies that the covariance between \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) is not defined and is therefore indicated as dots in the covariance matrix (Lokshin and Sajaia, 2004; Akpalu and Normanyo, 2014). Given the assumption with respect to the distribution of the disturbance terms, the logarithmic likelihood function for the system of is

Where F is a cumulative normal distribution function, f is a normal density distribution function, \({{\rm{\omega }}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is an optional weight for observation i.

Among them,

Where \({{\rm{\rho }}}_{{\rm{p}}}={{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{pu}}}^{2}/{{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{u}}}{{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{p}}}\) is the correlation coefficient between \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{pi}}}\) and \({{\rm{u}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\); and \({{\rm{\rho }}}_{{\rm{np}}}={{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{npu}}}^{2}/{{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{u}}}{{\rm{\sigma }}}_{{\rm{np}}}\) is the correlation coefficient between \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{{\rm{npi}}}\) and \({{\rm{u}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\). After estimating the model’s parameters, the conditional expectations can be calculated below:

Rural income from national-level key poverty-stricken county with participation in the NRECDP (observed):

Rural income from national-level key poverty-stricken county with participation in the NRECDP (counterfactual):

The average treatment effect of the treatment group (ATT) can be analyzed by comparing the expectations of the observed and counterfactual conditional:

Variables and descriptive statistics

As mentioned before, the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Finance have been promoting the NRECDP since 2014. The purpose is to enhance rural e-commerce applications, cultivate new rural market players, and facilitate the two-way flow of agricultural products into cities and industrial products into the countryside, thereby increasing rural residents’ income and consumption. Therefore, we select the per capita net income of rural residents as the explained variable (Li and Qin, 2022). We obtain rural residents’ per capita net incomes from each NLKPS county’s national economic and social development bulletin and then take the natural logarithm. Note that the central fiscal support for the NRECDP counties is primarily used to improve the public service system of rural e-commerce, such as logistics and distribution systems, and to cultivate entrepreneurship leaders in rural e-commerce. Thus, as a core policy variable, if the NLKPS counties are selected to participate in the NRECDP, taking values 1 and 0 otherwise.

The core explanatory variable is digital inclusive finance, measured by the Digital Inclusive Finance Index at the county level (Yu et al., 2022). The Digital Inclusive Finance Index, developed by Peking University, is based on big data from Ant Financial Services and covers three dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and digital support services. There are six sub-index categories: payment, insurance, monetary funds, investment, credit investigation, and credit. It has three levels: province, municipality, and county (Li and Zhao, 2020).

Additionally, several control variables account for the economic characteristics of these counties: (1) Education level, measured by the number of students enrolled in public secondary and elementary schools (unit: persons); (2) Population density, measured by dividing the resident population (unit: 10,000 persons) by the area of the administrative region (unit: square kilometers); (3) Economic growth level, measured by gross regional product per capita (unit: yuan); (4) Infrastructure, measured by the number of fixed-line subscribers, as this data is more complete compared to road mileage and cell phone subscriber data at the county level; (5) Industry structure, measured by the ratio of gross regional product to the value-added of the tertiary industry; (6) Financial self-sufficiency rate, calculated by the ratio of local general public budget expenditure to local general public budget revenue, representing the proportion of a region’s fiscal expenditures generated independently, with a smaller value indicating greater dependence on transfers, government fund revenues, debt revenues, etc.; (7) E-commerce development level, measured by the number of Taobao villages.

The instrumental variable should influence the NRECDP participation of counties but not rural income. Following Li and Qin (2022), we obtained an instrumental variable that varies over time and location by multiplying each county’s average slope by the year. This approach is justified as follows: the primary topographic feature impacting transportation infrastructure is the slope. Rural infrastructure development affects agricultural product processing and the two-way flow of industrial commodities to rural areas, influencing rural transportation conditions. A solid foundation for rural e-commerce can affect counties’ decisions to participate in extensive e-commerce demonstration projects in rural areas. Although topographic factors do affect income, their impact is long-term and does not significantly alter income growth rates in the short term. Therefore, we assert that the slope satisfies the exogeneity requirement. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2.

Empirical results

Main results

The estimations of the factors influencing participation in the NRECDP and the impacts of involvement in the NRECDP on rural income growth are reported in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the correlation coefficient \({{\rm{\rho }}}_{{\rm{p}}}\) is significantly negative. It indicates that the rural residents’ income with participation in the NRECDP significantly differs from that of a random individual in our sample data. The negative value denotes that the rural income of NLKPS counties participating in the NRECDP is more significant than that of a random observation in the sample (Liu et al., 2021; Lokshin and Sajaia, 2004).

In our analysis of the determinants of participation in the NRECDP across 592 NLKPS counties, digital inclusive finance emerges as a critical factor. Specifically, greater local promotion of digital inclusive finance significantly enhances the likelihood of NRECDP selection. Elevated levels of digital inclusive finance indicate that rural residents have advanced financial literacy and digital technological capabilities. It suggests that policy biases favoring rural e-commerce could potentially yield more substantial achievements.

The analysis confirms the crucial role of e-commerce levels in the selection process for the NRECDP, aligning with the prioritization of a robust e-commerce foundation as outlined in official documents. Additionally, the structure of local industries emerges as a critical determinant of NRECDP selection, influencing regional economic development, income levels, and consumption patterns. The finding resonates with the conclusions drawn by Ma et al. (2022), highlighting the significance of economic development and infrastructure in fostering rural e-commerce. A well-established logistics sector and efficient transportation networks often accompany higher levels of economic development.

Furthermore, the instrumental variable, derived from the average county slope multiplied by year, shows a statistically significant negative impact below the 1% threshold in ESR estimation, affirming its validity. It indicates that flatter terrains are more conducive to rural e-commerce development, consistent with the findings by Li and Qin (2022). In essence, the selection process for the NRECDP hinges on a blend of economic factors conducive to enhancing rural e-commerce capabilities.

In the outcome equation presented in Table 3, the results illustrate the income impacts on NLKPS counties participating in or not participating in the NRECDP. The coefficient of digital inclusive finance shows a significantly positive effect in both the treatment and control groups, consistent with the findings by Li and Jiang (2023) and Li and Ma (2021). It suggests that higher levels of digital inclusive finance enhance net income for rural residents, regardless of NRECDP participation. Moreover, we observe that the income growth impact of digital inclusive finance is more pronounced among counties participating in the NRECDP compared to those that do not. It indicates that the marginal impact of digital inclusive finance on rural income is more substantial in counties involved in the NRECDP.

Digital inclusive finance plays a pivotal role in developing rural financial infrastructure, reducing financial service costs, expanding rural financial service coverage, and enhancing the risk prevention capabilities of local financial institutions. As regional financial development progresses, the diversity and efficiency of financial products improve, meeting the evolving financial needs of rural residents and consequently boosting income levels (Li and Ma, 2021).

The advancement of overall economic development positively correlates with rural income growth. Higher local economic development levels not only provide a solid foundation for e-commerce growth but also correlate with increased GDP per capita, reflecting higher levels of residents’ consumption. This dual effect strengthens the demand for e-commerce, thereby serving as a potent catalyst for rural e-commerce development and subsequent income growth.

Moreover, education level emerges as a crucial factor in enhancing rural residents’ income, similar to the findings by Su and Heshmati (2013), Li and Ma (2021), and Li and Yang (2023). Particularly in NLKPS counties not participating in the NRECDP, higher education levels significantly bolster rural income. Additionally, population density shows similar impact dynamics to digital inclusive finance. The high population density facilitates efficient service industry operations by lowering production and consumption costs. The environment would be conducive to developing the service sector, a critical aspect of rural economic growthFootnote 3. Increased population density also provides the necessary labor force for rural e-commerce development, thereby further augmenting rural income.

The treatment effect estimation results for both the treatment and control groups are shown in Table 4. Significant income growth is observed in the treatment group, with an average treatment effect of ~12.97%. This finding aligns closely with the results reported by Qin and Fang (2022). Participation in the NRECDP is projected to increase rural residents’ income in NLKPS counties by more than 10%, thereby significantly contributing to poverty alleviation and rural revitalization in these economically disadvantaged regions.

Similarly, the control group exhibits a growth impact on rural income, albeit at a slightly lower rate of 9.20%. It reaffirms the effectiveness of the NRECDP as a policy initiative capable of stimulating rural income growth. The introduction of rural e-commerce has expanded sales channels for agricultural products and bolstered e-commerce sales overall. Concurrently, it has mitigated the historical plight of farmers functioning solely as price takers, thereby fostering income growth. Furthermore, the agglomeration effects inherent in rural e-commerce generate substantial economies of scale on the supply side, thereby enhancing the sustainability of income growth among farmers.

Robustness check

Model method

Similar to the ESR model, the endogenous treatment effect model serves to mitigate the impact of self-selection bias, providing a robustness check in our analysis. Like the ESR model, it comprises a selection equation and an outcome equation. The selection equation examines the factors influencing participation in the NRECDP, while the outcome equation assesses the income effects of participation. The estimated results validating the marginal impact of transitioning from non-participation to participation in the NRECDP on rural income are presented in Table 5. In the outcome equation, we find compelling evidence that participation in the NRECDP significantly boosts rural income, consistent with our primary findings. Additionally, indicators such as digital inclusive finance, the level of e-commerce development, and industry structure in both equations exhibit results consistent with our main findings. Notably, in the outcome equation, variables such as population density and economic growth display robust coefficients.

Core explained variables

Drawing on Jiao et al. (2024), digital inclusive finance can be disaggregated into two components: financial coverage breadth and financial usage depth. As a robustness check, we substitute these components for digital inclusive finance. The estimation results of the treatment effect in both the treatment and control groups are detailed in Table 6. Notably, these results closely align with our main findings, thereby reinforcing the robustness of our main results.

Heterogeneity analysis

Ethnic regions and non-ethnic regions

China’s eight ethnic regions include the five major minority autonomous regions—Inner Mongolia, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Tibet Autonomous Region, and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region—alongside the provinces of Guizhou, Yunnan, and Qinghai, which are known for their high concentration of ethnic minorities. According to 2014 data, these regions collectively contribute ~10% to the national GDP, cover about 58% of the country’s total land area, and are home to 14% of the population. Numerous surveys indicate that these areas pose significant challenges and are pivotal in the effort to achieve comprehensive societal prosperity. Despite these regions surpassing the national average in both economic and income growth rates, they continue to see a widening absolute gap compared to the national averageFootnote 4.

Based on a sample survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics, the rural poor population in China’s eight ethnic provinces and regions totaled 22.05 million in 2014, reflecting a poverty reduction rate of 13.9%, slightly below the national average of 14.9% during the same period. The proportion of rural poverty in these eight ethnic areas relative to the nation’s rural population (poverty incidence rate) was 14.7%, encompassing 31.4% of the national rural poor population. From 2011 to 2014, while the proportion of the rural population in the eight ethnic regions to the national population remained around 17%, the proportion of rural poverty persisted above 30%. In 2014, the poverty incidence rate in these regions exceeded the national rate by 7.5 percentage points. Notably, the ratio of rural poverty in the eight ethnic regions to national rural poverty (31.4%) was nearly double their share of the national rural population (~17%).

Gustafsson and Ding (2020) identify various factors contributing to ethnic income disparities in rural China, including geographical location, limited land and productive assets, disparities in human and social capital, demographic differences, and varying preferences. Consequently, the distribution of rural poverty, poverty reduction rates, and economic growth in ethnic regions exhibit significant heterogeneity. To address this, a subgroup analysis is conducted to mitigate the effects of distribution disparities between ethnic and non-ethnic areas. The findings are detailed in rows (1) and (2) of Table 7.

NLKPS counties in ethnic regions participating in the NRECDP exhibit significantly lower rural income growth compared to those in non-ethnic regions. Specifically, the income growth effect from NRECDP participation in NLKPS counties within non-ethnic regions stands at ~25.23%, surpassing the overall average. It highlights the NRECDP’s effectiveness as a policy tool for poverty reduction, significantly boosting rural income growth in NLKPS counties, especially within non-ethnic regions. However, its positive impact in ethnic regions is somewhat different, with a notably wider gap compared to non-ethnic regions.

Geographic location heterogeneity

China is typically categorized into three major economic regions based on development levels and geographic positioning: the eastern, central, and western regions (Luo et al., 2023). Accordingly, NLKPS counties are subgrouped based on their geographic location to assess the income growth effects of participation in the NRECDP. Results from lines (3) and (4) of Table 7 indicate that the average treatment effect in the central region surpasses that of the western region. The finding aligns with outcomes observed in ethnic regions, where the average treatment effect tends to be lower. Notably, ethnic regions are predominantly situated in the western region, which is less conducive to rural e-commerce development (Chen et al., 2023).

Moreover, the western region faces challenges such as its distance from the eastern core of developed e-commerce industries, which poses difficulties in radiating economic benefits. Extended logistics and transportation distances further hinder spending on e-commerce platforms, thus limiting the impact of policies aimed at developing rural e-commerce. The rugged terrain increases infrastructure costs and complicates efforts to establish suitable conditions for e-commerce development. Geographically, higher logistics costs in the west may impede rural e-commerce consumption, which is exacerbated by limited exposure to central e-commerce hubs. Nevertheless, consistent findings suggest that policy preferences can yield some benefits for economically disadvantaged rural areas in the west.

Industry structure heterogeneity

Our main results reveal the significant influence of industry structure in both the selection and outcome equations. The composition of industries in rural areas plays a critical role in driving rural income growth. Specifically, a robust tertiary industry with high value-added capabilities can stimulate economic development and increase rural residents’ incomes (Li and Ma, 2021). Thus, we take the sample mean as a benchmark and classify above average as high industrial structure level and low industrial structure level as the opposite to observe the specific impact of industrial structure on policy implementation. These findings are detailed in lines (5) and (6) of Table 7.

Our analysis shows that the average treatment effect among subgroups with higher levels of industrial structure is more pronounced compared to those with lower levels, irrespective of participation in the NRECDP. Additionally, within the high-level industrial structure subgroup, the average treatment effect of the treatment groups is significantly higher. It underscores that the NRECDP’s impact on rural income growth is most effective when implemented in counties with a robust industrial foundation. Conversely, regions with weaker industrial structures struggle to integrate rural e-commerce development with their economic base, thus limiting their developmental potential.

Three regions and three prefectures, non-three regions and three prefectures

In 2018, China introduced the concept of “three regions and three prefectures,” identifying them as severely impoverished areas and focal points for poverty eradication efforts nationwide. The three regions include Tibet and Tibetan ethnic areas in Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu, and Qinghai provinces, along with four prefectures in southern Xinjiang (Hotan, Aksu, Kashi, and Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture). The three prefectures are Liangshan in Sichuan, Nujiang in Yunnan, and Linxia in Gansu. These areas face severe poverty characterized by high incidence rates, deep-rooted causes, inadequate infrastructure, underdevelopment, and limited public services, posing the most significant challenges in China’s poverty alleviation strategyFootnote 5. Counties within these regions are prioritized among the 592 NLKPS counties.

To delve deeper into these contexts, we conducted a subgroup analysis, with results detailed in lines (7) and (8) of Table 7. The analysis reveals that rural income in the selected three regions and three prefectures under the NRECDP increased significantly by 37.98%. Despite this growth, the average rural income outcomes in these areas remain lower than those in non-three regions and prefectures. These findings underscore the NRECDP’s efficacy as a policy tool for promoting rural e-commerce development and enhancing incomes in severely impoverished areas.

According to the 2020 Report on Agricultural Product E-commerce in China’s Deeply Impoverished Areas (2020), published by the China Poverty Alleviation Research Institute of Renmin University of China, the reports point out that as policies continue to gain momentum, e-commerce poverty alleviation has shown a benign trend of orderly promotion by governments at all levels, especially in deeply impoverished areas. Governments at all levels are actively implementing policies, and large-scale e-commerce enterprises have been laying out their business, achieving remarkable results in helping agricultural products move up the market and promoting rural income.

Potential mechanism analysis

Rural e-commerce support policies have effectively stimulated entrepreneurship and consequently increased rural income through initiatives such as financial backing, technical training, infrastructure enhancement, branding, and business incubation. Song et al. (2023) highlight that e-commerce development significantly bolsters rural entrepreneurship, with a more pronounced effect observed in less-developed regions. Additionally, Huang et al. (2022) find a positive correlation between policy support and rural residents engaging in e-commerce entrepreneurship, suggesting that supportive policies influence startup costs and encourage rural residents to embark on e-commerce ventures. Mei et al. (2020) also affirm that government and e-commerce platform support positively impact rural household entrepreneurship, underscoring the pivotal role of robust support mechanisms.

As these studies indicate, a clear link exists between rural e-commerce development and entrepreneurship, with entrepreneurship serving as a pathway to increasing rural non-agricultural income. Building on these insights, we further explore the mechanism through which rural e-commerce development enhances rural income by examining entrepreneurship as a potential intermediary. In our mechanism analysis, we use county-level entrepreneurial activity as the dependent variable, measured by the logarithm of business registrations plus one, sourced from county statistical yearbooks and business registration data. The results are detailed in Table 8.

Our estimation reveals that the Average Treatment Effect on entrepreneurship from the NRECDP is 0.111, significant at the 1% level. The finding confirms that national policy support for rural e-commerce effectively promotes entrepreneurial activities. This outcome aligns with prior research emphasizing the role of rural e-commerce in fostering entrepreneurship (Song et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2022; Mei et al., 2020). In essence, participation in the NRECDP enhances entrepreneurial initiatives in NLKPS counties, thereby influencing rural income levels.

Conclusion

The rapid evolution of the digital economy, primarily facilitated by information networks, presents both opportunities and challenges for rural e-commerce development in China. Particularly, the positive impact of digital inclusive finance in reducing transaction costs and fostering new entrepreneurial opportunities promises to enhance rural e-commerce and increase rural residents’ incomes. The Chinese government has implemented various policies and initiatives to modernize and develop rural areas, including launching the NRECDP in 2014. This initiative provides targeted financial support to selected counties to enhance rural e-commerce infrastructure and capabilities.

Our analysis addresses several critical questions using data from 592 NLKPS counties spanning 2014 to 2020. First, we evaluate whether the NRECDP effectively increases rural incomes, especially within these NLKPS counties. Second, we explore whether heterogeneities such as ethnic regions, geographic locations, industrial structures, and the designated “three regions and three prefectures” differentially influence rural income growth. Third, we investigate the determinants influencing NLKPS counties’ selection to participate in the NRECDP. Finally, we analyze potential mechanisms linking NRECDP implementation to rural income growth.

To mitigate self-selection bias, we employ the ESR model, yielding the following insights: First, our results confirm the NRECDP as an effective policy tool, showing a significant income growth effect of ~12.97% for participants. Second, economic indicators such as infrastructure, e-commerce development, industry structure, and notably, digital inclusive finance, significantly influence NRECDP participation and rural income. Additionally, the determinants of rural income include education levels, economic development, population density.

Heterogeneity analysis reveals that non-ethnic regions experience a more pronounced income growth effect from NRECDP participation compared to ethnic regions. Notably, the “three regions and three prefectures” exhibit a higher income growth effect, reflecting their intense poverty alleviation needs. Regional analysis further indicates that the central region benefits more from the NRECDP than the western region, with industrial structure levels also impacting income growth outcomes. Notably, these ethnic regions are primarily located in western China.

Additionally, our mechanism analysis identifies entrepreneurship as a key intermediary linking NRECDP implementation to rural income growth. Based on these findings, we propose policy recommendations: First, continue promoting NRECDP implementation with targeted support for the “three regions and three prefectures” to ensure significant rural income growth. Second, enhance infrastructure and facilitate partnerships with foreign e-commerce platforms to expand export channels for local agricultural products and extend industrial chains. Third, prioritize advancing digital inclusive finance to bridge regional digital divides, complemented by comprehensive training programs enhancing digital literacy and entrepreneurial skills among rural residents and local entrepreneurs in NLKPS counties.

Our study acknowledges several limitations. Due to data availability, we measure infrastructure development using fixed-line telephone subscriptions, potentially underrepresenting rural e-commerce relevance where internet users or road mileage might be more pertinent. Additionally, our study uses the initial batch of NLKPS counties from 2014, but subsequent adjustments in county listings were not fully controlled, necessitating consideration in future research.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BLNX7Y.

Notes

The lists of 331 national-level poverty-stricken counties were first identified in 1986; the number had increased to 592 by the first adjustment in 1994. After the second adjustment in 2001, the national-level poverty-stricken counties were renamed as the key counties for national poverty alleviation and development, and all 33 key counties in the east were transferred to the central and western regions. The total number remained unchanged at 592. The third adjustment in 2011 changed the selection of 38 key counties, totally unchanged. At the same time, 680 counties with geographical connections, similar climates and environments, and similar poverty-causing factors were identified as concentrated and contiguous special poverty-stricken counties, of which 440 counties were also among the 592 poverty-stricken counties. Excluding the overlapping parts, there were a total of 832 national-level poverty-stricken counties distributed in 22 provinces., which have not changed since then.

References

Akpalu W, Normanyo AK (2014) Illegal fishing and catch potentials among small-scale fishers: application of an endogenous Switching regression model. Environ Dev Econ 19(2):156–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X13000478

Charlery LC, Qaim M, Smith-Hall C (2016) Impact of infrastructure on rural household income and inequality in Nepal. J Dev Eff 8(2):266–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2015.1079794

Chen C, Gan C, Li J, Lu Y, and Rahut D (2023) Linking farmers to markets: does cooperative membership facilitate e-commerce adoption and income growth in rural China? Econ Anal Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2023.09.040

Chen S, Liu W, Song H, Zhang Q (2024) Government-led e-commerce expansion project and rural household income: Evidence and mechanisms. Econ Inquiry 62(1):150–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.13167

Couture V, Faber B, Gu Y, Liu L (2021) Connecting the countryside via e-commerce: evidence from China. Am Econ Rev Insights 3(1):35–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20190382

Ding R, Shi F, Hao S (2022) Digital inclusive finance, environmental regulation, and regional economic growth: an empirical study based on spatial spillover effect and panel threshold effect. Sustain 14(7):4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074340

Fan J, Tang L, Zhu W, Zou B (2018) The Alibaba effect: spatial consumption inequality and the welfare gains from e-commerce. Journal of International Economics 114:203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.07.002

Gao X (2022) Qualitative analysis of the key influencing factors of farmers participate in agricultural products E-commerce to help rural revitalization. Acad J Bus Manag 4(17):121–130. https://doi.org/10.25236/AJBM.2022.041716

Ge H, Tang L, Zhou X, Tang D, Boamah V (2022) Research on the Effect of Rural Inclusive Financial Ecological Environment on Rural Household Income in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):2486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042486

Gustafsson BA, Ding S (2020) Ethnic income gaps in seven rural regions of China. Ethnicity and inequality in China. Routledge. 25–60

Haji K (2021) E-commerce development in rural and remote areas of BRICS countries. J Integr Agric 20(4):979–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63451-7

Han F, Li B (2021) Exploring the effect of an enhanced e-commerce institutional mechanism on online shopping intention in the context of e-commerce poverty alleviation. Inf Technol People 34(1):93–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-12-2018-0568

He C, Qiu W, Yu J (2022) Climate change adaptation: a study of digital financial inclusion and consumption among rural residents in China. Front Environ Sci 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.889869

Huang L, Huang Y, Huang R, Xie G, Cai W (2022) Factors influencing returning migrants’ entrepreneurship intentions for rural e-commerce: an empirical investigation in China. Sustainability 14(6):3682. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/6/3682

Jiao Y, Wang G, Li C, Pan J (2024) Digital inclusive finance, factor flow and industrial structure upgrading: evidence from the yellow river basin. Financ Res Lett 62:105141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105141

Leong C, Pan SL, Newell S, Cui L (2016) The emergence of self-organizing E-commerce ecosystems in remote villages of China. Mis Q 40(2):475–484. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.11

Li G, Qin J (2022) Income effect of rural E-commerce: empirical evidence from Taobao villages in China. J Rural Stud 96:129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.10.019

Li H, Shi Y, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Gong M (2023) Digital inclusive finance & the high-quality agricultural development: Prevalence of regional heterogeneity in rural China. PLoS ONE 18(3):e0281023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281023

Li H, Jiang H (2023) Effect of the digital economy on farmers’ household income: county-level panel data for Jilin Province, China. Sustain 15(5):4450. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054450

Li H, Yang S (2023) The road to common prosperity: can the digital countryside construction increase household income? Sustain 15(5):4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054020

Li J, Wu Y, Xiao JJ (2020) The impact of digital finance on household consumption: evidence from China. Econ Model 86:317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.027

Li J, Zhao D (2020) Analysis on the development of rural e-commerce in Hubei province under the background of rural revitalization strategy[C]. In 2020 international conference on E-commerce and internet technology (ECIT). IEEE

Li L, Du K, Zhang W, Mao J-Y (2019) Poverty alleviation through government-led e-commerce development in rural China: an activity theory perspective. Inf Syst J 29(4):914–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12199

Li T, Ma J (2021) Does digital finance benefit the income of rural residents? A case study on China. Quant Financ Econ 5(4):664–688. https://doi.org/10.3934/QFE.2021030

Liu M, Zhang Q, Gao S, Huang J (2020) The spatial aggregation of rural e-commerce in China: an empirical investigation into Taobao Villages. J Rural Stud 80:403–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.016

Liu M, Min S, Ma W, Liu T (2021) The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: application of an endogenous switching regression model. J Rural Stud 83:106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.02.021

Lokshin M, Sajaia Z (2004) Maximum likelihood estimation of endogenous switching regression models. Stata J 4(3):282–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0400400306

Luo X, Niu C (2019) E-Commerce participation and household income growth in Taobao Villages. Policy Research Working Paper Series 8811, The World Bank

Luo G, Yang Y, Wang L (2023) Driving rural industry revitalization in the digital economy era: exploring strategies and pathways in China. PLoS ONE 18(9):e0292241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292241

Ma W, Qiu H, and Rahut DB (2022) Rural development in the digital age: Does information and communication technology adoption contribute to credit access and income growth in rural China? Rev Dev Econ. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12943

Mei Y, Mao D, Lu Y, Chu W (2020) Effects and mechanisms of rural E-commerce clusters on households’ entrepreneurship behavior in China. Growth Change 51(4):1588–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12424

Peng C, Ma B, Zhang C (2021) Poverty alleviation through e-commerce: Village involvement and demonstration policies in rural China. J Integr Agric 20(4):998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63422-0

Qin Y, Fang Y (2022) The effects of E-commerce on regional poverty reduction: evidence from China’s rural E-commerce demonstration county program. China World Economy 30(3):161–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12422

Song Y, Li L, Sindakis S, Aggarwal S, Chen C, Showkat S (2023) Examining E-commerce adoption in farmer entrepreneurship and the role of social networks: data from China. J Knowl Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01379-6

Su B, Heshmati A (2013) Analysis of the determinants of income and income gap between urban and rural China. China Econ Policy Rev 02(01):1350002. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1793969013500027

Sun L, Zhu C (2022) Impact of digital inclusive finance on rural high-quality development: evidence from China. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc 2022(1):7939103. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7939103

Wang W, He T, Li Z (2022) Digital inclusive finance, economic growth and innovative development. Kybernetes. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-09-2021-0866

Wei YD, Lin J, Zhang L (2020) E-commerce, taobao villages and regional development in China. Geogr Rev 110(3):380–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12367

Xiong M, Li W, Teo BSX, Othman J (2022) Can China’s digital inclusive finance alleviate rural poverty? An empirical analysis from the perspective of regional economic development and an income gap. Sustain 14(24):16984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416984

Xiong X, Nie F, Bi J, Waqar M (2017) The research on the path of poverty alleviation of e-commerce: a case study of jing dong. J Simul 5(2):73

Xu G, Zhao T, Wang R (2022) Research on the efficiency measurement and spatial spillover effect of China’s regional Ecommerce poverty alleviation from the perspective of sustainable development. Sustain 14(14):8456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148456

Yin ZH, Choi CH (2022) Does e-commerce narrow the urban–rural income gap? Evidence from Chinese provinces. Internet Res 32(4):1427–1452. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2021-0227

Yu C, Jia N, Li W, Wu R (2022) Digital inclusive finance and rural consumption structure–evidence from Peking University digital inclusive financial index and China household finance survey. China Agric Econ Rev 14(1):165–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-10-2020-0255

Zhang Y, Long H, Ma L, Tu S, Li Y, Ge D (2022) Analysis of rural economic restructuring driven by e-commerce based on the space of flows: the case of Xiaying village in central China. J Rural Stud 93:196–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.001

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Key Laboratory of Automotive Power Train and Electronics (Hubei University of Automotive Technology), (No. ZDK12023B02); Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Program Youth Project (No. Q20231805; No: Q20231802).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mengzhen Wang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing– original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xingong Ding: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing– original draft, Writing – review & editing. Pengfei Cheng: Formal analysis, Writing– original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Ding, X. & Cheng, P. Exploring the income impact of rural e-commerce comprehensive demonstration project and determinants of county selection. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1286 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03785-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03785-w