Abstract

Given the limited number of studies on creative thinking skills, particularly the use of the Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT) thinking program among elementary-level students in Pakistani public schools, this study investigates the program’s effectiveness on 8th-grade English students’ creative thinking abilities. A quasi-experimental research design, employing a pretest-posttest control group method, was used. Participants were divided into experimental and control groups. The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) measured the program’s effectiveness. The study was conducted in two stages: teacher training and experimentation with 60 students. In stage I, two teachers were trained to integrate CoRT thinking lessons into their English curriculum, enhancing teaching methods and fostering creative thinking in students. In stage II, the experimental group of 30 students received the CoRT program, while the control group of 30 did not. This experimental phase, lasting six weeks, took place in the English classroom of Government Girls MC High School Kot Fareed, Sargodha, Pakistan. The findings revealed that participants who underwent the CoRT program training demonstrated significant improvement in creative thinking abilities compared to those who did not receive the training, as measured by the TTCT. The study suggests practical implications for educators, emphasizing the creation of environments in public schools that nurture creative abilities by incorporating activities that promote creative thinking skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers are currently experiencing what is referred to as the “age of creativity” (Cropley, 2004, p.13), where creative thinking has become a universal priority, particularly a concept emphasized by influential organizations like the Nomura Research Institute of Japan (Nomura, 2007, p.1). Consequently, academic institutions have an increasing obligation to teach creative thinking to their students (Alzoubi et al., 2016; Kampylis, Berki (2014)).

“One of the most effective ways to cultivate creative thinking in students is through modeling creative activities and teaching creative techniques and strategies” (Davies et al., 2014; Fazal et al., 2023; Turner-Bisset, 2007). Teachers’ emphasis on creative thinking can enhance their students’ creative abilities (Hosseini, 2011). Teaching creative thinking supports effective teaching, academic achievement, teaching methods, and students’ personal experiences (Jeng et al., 2010).

However, Pirzada’s (2020) study indicates that rigid curricula and tight training schedules in Pakistan leave little room for fostering creative thinking. Teachers often lack the capacity to emphasize creativity. As one noted, “We claim to promote creative thinking, but our methods don’t allow it.” Addressing these constraints is essential to fully realize the benefits of creative education. Rashid and Qaisar (2016) observed that Pakistani public schools focus heavily on rote memorization and factual content, especially in English classrooms, where outdated methods like drills and grammar translation dominate. These ineffective practices, coupled with untrained teachers, fail to foster critical thinking skills.

Additionally, teachers in public schools are not accustomed to lesson planning and often enter the classroom without proper preparation. In Pakistan, a significant issue is the age of teachers and the lack of proper training and knowledge updates. While experience can be beneficial, it may not compensate for the lack of ongoing professional development. As courses and curricula change over time, teachers must adapt and adjust their teaching methods accordingly (Ashraf et al., 2015; Aslam, 2013; Pakistan Education Statistics, 2022). Without access to relevant training and professional development opportunities, teachers may continue to rely on traditional teaching methods that do not promote creative thinking or active student engagement. Traditional teaching methods, such as reading textbook chapters aloud and having students passively listen, can be ineffective and counterproductive. This approach leads to disengagement and poor academic performance among students (Ashraf et al., 2015; Khan, 2021).

This is an urgent dilemma. Delivering information is no longer sufficient to prepare students for their future (Shaheen, 2011). There is a global shift in education, moving away from solely imparting knowledge and toward the development of critical skills, such as creative thinking. The importance of creative thinking is increasingly recognized as a key driver of growth and innovation (Brundrett, 2007). Developing nations must consider this in order to improve their educational systems (Shaheen, 2011).

Despite global advancements in educational practices, Pakistani public schools often lack the resources and training necessary to implement innovative teaching strategies (Aslam, 2013; Kalim & Bibi, 2024). This deficiency in fostering creative thinking skills leaves students ill-prepared for the demands of the modern world. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore and implement programs that cultivate these essential skills. This study aims to investigate the effectiveness of the CoRT (Cognitive Research Trust) program in enhancing creative thinking abilities among students in Pakistani public schools, thereby addressing a critical gap in current educational practices. The primary objective is to offer recommendations for policy reform, curriculum development, textbook selection, teaching techniques, and teacher attitudes that are suitable for the local context. This will enable the government to enhance students’ creative thinking skills through elementary education by building on existing practices rather than relying on foreign best practices. By providing recommendations that are culturally appropriate, the risk of imposing and sustaining foreign creative thinking concepts is minimized (Sen & Sharma, 2004, p.153). This study is therefore an effort to genuinely localize research in creative thinking.

Research questions

What are the levels of creative thinking among students in Pakistan?

To what extent do Pakistani elementary students exhibit creative thinking when applied the experiment?

Research hypothesis

H1: There is a positive effect of creative thinking programs on students.

H2: There are statistically significant differences between control and experimental groups.

H3: There are statistically significant differences between the pre-test and post-test in the experimental group.

Literature review

Globalization and creative thinking

In the increasingly globalized world, innovation is highly valued as an essential personal trait. The progress of humanity is heavily reliant on innovation and discovery. Thus, creativity is no longer just seen as a means of expressing human potential, but it is also recognized as a central element for communal growth (Primi, & Wechsler, 2018). As globalization spreads, companies in developing countries face growing pressure to innovate, with fields like software, design, and education becoming increasingly vital (The Global Innovation Index GII (2015)). The education sector must adapt to societal needs by adopting practices that foster creativity (Dumont et al., 2010; Schleicher, 2012; Winner et al., 2013). As a crucial social institution, education plays a significant role in societal survival and prosperity. To achieve sustainable and exceptional education, it must continually evolve to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing globalized world, requiring systemic innovation in teaching and learning (Serdyukov, 2017).

Hence In this groundbreaking age, everything is getting old and traditional which is not changing itself or infusing change for the betterment whether human or nonhuman. Old and traditional things just look good in museums. A similar case is with the teachers; and their teaching ways and techniques in schools. In Pakistan, traditional methods are no longer capable of meeting the needs of this new era. Just conveying Information or facts and discussing some important points is not enough. Contemporary and inventive teaching practices are needed to stimulate thinking and curiosity to improve mental abilities (Kalim & Bibi, 2024). This contrasts with countries like Finland, where innovative teaching practices that emphasize student-centered learning and critical thinking are more prevalent (Niemi & Jakku-Sihvonen, 2011). The need of the time is to generate possibilities for the students which encourage their learning and employ the modern data for understanding knowledge and facts mounting swiftly (Florida, 2014; IBM Institute for Business Value, 2016).

Creative thinking training program

Commercial programs like the Purdue Creativity Program (PCP), Productive Thinking Program (PTP), and Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT) teach cognitive skills that enhance creative thinking, such as problem recognition and generating solutions (Alkahtani, 2009; Sternberg et al., 2002). While Scott et al. (2004) found value in each program, this study focused on developing a creativity training program based on CoRT for elementary students and teachers, aiming to assess its effectiveness in promoting creative thinking.

The Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT) thinking program was developed by Edward de Bono in the 1980s as a comprehensive framework to teach thinking as a skill. De Bono, a pioneer in the field of creative thinking, designed the CoRT program to be applicable across various educational contexts and age groups. The CoRT is comprised of six sections, each containing ten lessons that address different aspects of de Bono’s definition of thinking, including breadth, organization, interaction, creativity, information and feeling, and action. An author of over fifty-six books on teaching thinking, de Bono introduced the concept that reckoning issues may require diverse kinds of thinking (Wilson, 2000). The CoRT program has been widely recognized for its impact on enhancing creative thinking skills in educational settings (Topping, 2023). However, while much of the existing literature reiterates its benefits, there is a need to explore diverse implementations to fully understand its efficacy.

CoRT has been spread to a great many countries, many subjects, and higher education and the workplace (Topping, 2023). Studies on the CoRT program in the UK (Smith & Jones, 2010), Malaysia (Chew et al., (2017)), South Africa (Nofel, 2006), Jordan (Mohammad, 2017), and Saudi Arabia (Blewee, 2011) show significant improvements in creative thinking, critical thinking, problem-solving, classroom engagement, idea, and discussion dynamics. These findings demonstrate CoRT’s adaptability and effectiveness across diverse educational contexts, highlighting its global applicability and enriching our theoretical framework.

Developing creative thinking can enhance students’ self-concept, including self-ideal, self-image, and self-esteem, leading to greater self-efficacy, independence, and critical thinking (Fleith et al., 2002; Thorne, 2007). Creative thinking training may also positively impact academic achievement (Aness et al., 2012; Craft, 2002; Davis & Rimm, 1998; Mindham, 2004; Torrance, 1972, 1977; Torrance & Myers, 1970). The CoRT thinking program’s effectiveness in fostering creative thinking has been supported by numerous researchers (Al-Faoury & Khwaileh, 2014; Blewee, 2011; Chew et al., (2017); Dombaycı, 2014; Nofel, 2006; Zaiyadi et al., 2016).

Edward de Bono highlights that thinking is a fundamental skill crucial for our future, with about 90% of thinking errors linked to perception. His CoRT program teaches techniques to improve perception, leading to better responses (De Bono (1970); De Bono (1992); De Bono 2010). By encouraging children to approach problems from multiple perspectives and focus on divergent or “lateral thinking,” de Bono’s lessons help learners develop effective thinking skills (Higgins et al., 2004; Fisher, 2005).

Torrance test of creative thinking (TTCT)

The Torrance tests of creative thinking (TTCT) were developed by Torrance and his colleagues to identify gifted and creative individuals. This multiple-task paper-and-pencil measure of creative abilities was the result of nine years of research into the nature of creative behavior and its assessment. The research edition of the TTCT was published in 1966, and today the Scholastic Testing Service, Inc. (STS) holds the copyright for the test. It is the most widely used test for assessing creative abilities and has been utilized in more than 2000 studies (Kim, 2006; Thomas et al., 2002; Torrance, 1998). The TTCT was designed by Torrance based on his claim that all individuals possess some degree of creative thinking. However, he also believed that not all individuals with high creative ability will necessarily behave creatively. To behave creatively, an individual must possess the necessary thinking skills, such as critical thinking, as well as creative abilities, and must also be motivated (Torrance, 1998).

The TTCT is widely used in over 35 countries and is available in more than 32 languages (Kim, 2006; Thomas et al., 2002). There are two versions of the test: the verbal TTCT, or “Thinking creatively with words,” is suitable for first graders to graduate students and takes 45 min. It includes six word-based exercises to assess fluency, flexibility, and originality, and the figural TTCT, or “Thinking creatively with pictures or lines,” is for kindergartners to graduate students and takes 30 min. It assesses fluency, originality, elaboration, abstractness of titles, and resistance to premature closure through drawing exercises. Both versions are available in two equivalent forms, A and B (Torrance, 1998; Torrance et al., 1992). Additionally, it evaluates thirteen creative strengths, such as including emotional expressiveness, storytelling articulateness, movement or action, expressiveness of titles, synthesis of incomplete figures, synthesis of lines or circles, unusual visualization, internal visualization, extending or breaking boundaries, humor, richness of imagery, colorfulness of imagery, and fantasy (Torrance, 1998; Torrance et al., 1992).

Creative thinking in Pakistan

Naseer, (2014) states that Pakistani schools often lead to students recalling and reproducing the prescribed textbook contents. Parents repeatedly complain about their children’s performance in creative tasks and surprise tests. Despite being smart, learning in high-profile schools, and getting good grades on tests sometimes their children perform poorly in examinations. The reason for this poor performance could be creative tasks and unseen questions that are usually based on wordless pictures or a new topic (Akhter & Nordin, 2022; Ashraf et al., 2015; Chandio et al., 2013; Naseer, 2014). This problem is not only one or a specific group of children but a larger number of students are facing the same problem in Pakistan, (Ashraf et al., 2015) situation is worse in the public schools.

Numerous educationists and theorists have expressed doubts regarding the current curriculum’s potential to foster creative thinking among individuals, underscoring the significance of teaching creative thinking skills to children explicitly (Aness et al., 2012; Ashraf et al., 2015; Jameel & Mohamood, 2017).

Teachers play a crucial role in fostering creative thinking by providing learning opportunities and helping students recognize their creative potential. To do this, they must understand the characteristics of creative students, the creative process, and the necessary environment (Aljughaiman, 2002). The teacher-student relationship significantly impacts students’ creative thinking (Gurak-Ozdemir (2016)).

In Pakistani public schools, many teachers lack access to ongoing training, leading to outdated skills and limited knowledge of new teaching methods. As education systems evolve, continuous professional development is crucial for keeping teaching practices current and effective. As a result, many teachers in Pakistan may continue to rely on traditional teaching methods that may not be effective in engaging and motivating students to learn (Ashraf et al., 2015).

In Pakistani public schools, there is a lack of focus on teaching how to think, despite the crucial role of creative thinking in understanding subjects and life (Naseer, 2014; Pološki Vokić, Aleksić (2020)). Many countries emphasize thinking and creativity in curricula (AlZyoudi, 2009). Teachers’ ability to teach thinking skills is vital, as students enhance these skills through guided instruction (Rahman & Manaf, 2017). However, many teachers are unprepared to teach English effectively, which can impact students’ learning (Suliman & Yunus, 2014). Teachers should address language barriers and expose students to diverse perspectives to foster creative thinking (Case, 2013; Breslin, 2015). This highlights that while English instruction in Pakistan aims to develop creative thinking, it is uncertain if all necessary components are adequately addressed (Rahman & Manaf, 2017).

In Pakistan, creative thinking skills in schools receive insufficient attention, necessitating the introduction of creative thinking programs and teacher training. This study proposes the CoRT program to develop such skills, which has been effective worldwide for over 48 years in various countries including the UK, USA, Canada, Australia, Malaysia, Brazil, South Africa, Singapore, Japan, New Zealand, France, Ireland, India, Italy, Venezuela, Russia, and Philippines, in some Arab countries as well i.e., Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Palestine and UAE (AlZyoudi, 2009; Jarwan, 2007; Morgan & Foster, 1999; Topping, 2023). Despite its success, traditional teaching methods are less effective compared to contemporary programs like CoRT, which enhance creative thinking and practical success (Aness et al., 2012). Given the obstacles in teaching English and the lack of creative thinking programs in Pakistan, this study aims to train teachers to improve students’ creative thinking through English instruction.

Relation between creative thinking and education

Churchill suggested that education extends beyond formal schooling, a view supported by Michio Kaku (2014), who noted that schools often diminish natural curiosity. Shade and Shade (2016) propose an alternative report card assessing qualities like empathy, imagination, and risk-taking, which could boost students’ creativity and productivity. The latest import about creative thinking in education, though, commenced in the late 90 s (Jeffrey, 2005) and has subsequently been budding (Turner-Bisset, 2007) all over the world, counting nations such as the USA and UK (Feldman and Benjamin, 2006). Policymakers have observed additional constant attention than before (Craft, 2006), which has further to its recognition as a subject of discussion (Dickhut, 2003) stirring it from the vicinity of instruction…to being seen as an interior feature of teaching‟ (Craft, 2005, p.5). Since 2001, creative thinking has been recognized as a crucial aspect of education, with its development being given a high priority (Vong, 2008, p.149).

Creative thinking in teaching practices

Robinson (2001) echoed Sternberg’s views by noting that conventional education systems tend to suppress students’ natural inclination for creative and divergent thinking. Robinson argued that the current teaching methods often reward conformist thinking while punishing legitimate forms of creative thinking. Similarly, Sternberg (2006) contended that students perform better when they are taught in a manner that aligns with their thinking patterns. Children with practical or creative abilities are at a disadvantage when they are not taught or evaluated in a way that suits their unique abilities, leading to a disadvantage in their academic progress (p. 94).

Rahman and Manaf (2017) proposed a significant link between creative thinking and academic achievement. Cropley (2003) maintained that creativity provides teaching approaches that capture interest and thus, appear to be a more effective way of promoting learning and personal growth. Traditional teaching practices like reward and punishment, competition, evaluation, and transmission models have been found to stifle students’ innate creative abilities (Sinaga & Feranie, 2017). Conversely, classrooms that foster self-directed, student-centered learning and autonomy seem to nurture innovative and novel thinking tendencies (Soh, 2017). According to Lilly and Bramwell-Rejskind (2004), teachers can establish a positive learning environment, foster curiosity, and model flexibility. They believe that cultivating their creative thinking is a prerequisite for fostering it in their students (p.3).

Creative thinking and English teaching/learning

While creativity in education has been extensively studied, there is relatively less research on creativity in the context of teaching and learning English. Nonetheless, creative thinking can positively impact English language learning and teaching (AlKhars (2013)). For instance, Sullivan (2004) notes that creativity is an important quality that principals seek when hiring the best EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers. Novelty, which is closely related to creative thinking in education at large (e.g., Knight, 2002), is also associated with creative thinking in teaching and learning English, particularly in terms of transforming the language. Cheng and Yeh (2006) suggest that creative thinking involves “using new approaches, technologies, or ways of thinking” in the English language learning process (p. 41).

Several researchers in English language teaching and learning recognize creative thinking as an essential component of systematic educational reform (AlKhars (2013); Forrester & Hui, 2007). Creative thinking’s educational influence has been advocated by numerous researchers (Anderson, 2002; Aness et al., 2012; Bleedron, 2003, 2005; Cropley, 2003; Fasko, 2001; Plucker et al., 2004; Starko, 2005; Sternberg, 2006; Tan & Law, 2004; Torrance, 1995). Anderson (2002) notes that teachers, like creative artists, face risks of success and failure and emphasize the importance of passion in effective teaching. Similarly, Bleedron (2005) argued that exceptional teachers who surpass established curricula are likely to identify and cultivate creative thinking abilities in their students (p. 26).

Şenel, Bağçeci (2019) argue that schools face a dilemma between teaching creativity directly or promoting creative teaching practices. They suggest that to truly cultivate creative thinking, schools must employ innovative methods and create an environment where learning is part of the creative process. Effective teaching approaches are crucial for developing students’ thinking skills, but many teachers feel unprepared for teaching English literature (Suliman & Yunus, 2014). Humor, proven to enhance creativity (Shade & Shade, 2016), should be integrated into teaching to foster a positive learning environment. Additionally, homework should go beyond reinforcement to include creative problem-solving tasks, supporting the development of students’ thinking abilities (Şenel, Bağçeci (2019)). Briefly, adopting innovative teaching methods and creative homework can foster a positive learning environment that enhances creativity and critical thinking. This approach can lead to more engaged and successful learners ready for future challenges (Shade & Shade, 2016; Şenel, Bağçeci (2019)).

Methodology

Research design

The present study was a quasi-experimental research endeavor focused on developing and investigating creative thinking skills. Three raters thoroughly reviewed all the intervention materials and confirmed their suitability for implementation. This development and investigation were carried out in the context of student development and the exploration of the introduced phenomenon. The research aimed to explore the efficacy of the independent variable, i.e., teaching through the Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT), about creative thinking abilities as the dependent variable.

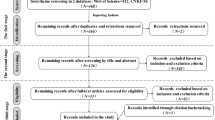

To achieve this goal, a pretest-posttest control group design was deemed the most suitable approach for this research study. This design involves both an experimental group and a control group, both of which undergo the same pre-test and post-test measures (Gall et al., 2003). This design was considered an acceptable method to achieve the study’s objectives and ascertain whether the thinking training program has an impact on creative thinking. The study’s population consisted of students studying English at the elementary level in the province of Punjab.

Research sample

The sample group for this study was determined using a purposive sampling method. This method was chosen to ensure that the selected participants were representative of the population we aimed to study—8th-grade students in Pakistani public schools. The study was conducted at Government Girls MC High School Kot Fareed Sargodha, a typical public school in the region. Two 8th-grade sections were selected, each consisting of 30 students (age 12–14 years), based on their availability and willingness to participate. This purposive sampling allowed us to focus on a specific subset of the student population that was most relevant to our research objectives.

Evidently, Gall et al. (2003) stated that a larger sample size increases the possibility of the participant’s scores on the considered variables being representative of the population scores. In experimental studies, it is generally recommended to have at least 15 participants in each group (Gall et al., 2003; Sheskin, 2000). In the present study, 30 participants were included in the experimental group and 30 in the control group. Although this sample size is considered statistically reliable for the study population (Gall et al., 2003; Sheskin, 2000), it limits the employment of inferential statistics.

To ensure the study’s reliability, we employed several strategies. The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) was used as the primary assessment tool due to its well-established reliability. Standardized pretests and post-tests were administered to both experimental and control groups, with the same teachers conducting the tests and experiment to minimize discrepancy. Three independent raters scored the TTCT, and their scores were averaged to minimize bias. Inter-rater reliability was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, indicating high internal consistency.

Research materials and procedures

The CoRT program, consisting of six components (breadth, organization, interaction, creativity, information, and action) aims to enhance students’ creative thinking for academic and personal success and is valuable for students, teachers, and parents alike (De Bono, 1986, 2004).

In this study, the researcher focused on CoRT-1 (breadth), CoRT-4 (creativity), and CoRT-6 (action) due to their proven effectiveness in promoting creative thinking (Ritchie & Edwards, 1996). These CoRT techniques were employed to train and develop creative thinking skills, with breadth complementing creativity, and action involving practical implications.

The study was conducted over a total period of eight weeks. Initially, a pretest was administered to both the experimental and control groups to measure their baseline creative thinking abilities. To assess students’ creative thinking, the figural TTCT was predominantly used, with some verbal TTCT tests to align with the thinking model. The test activities were scored on six dimensions of creative thinking: fluency, flexibility, originality, elaboration, abstractness of title, and resistance to premature closure. The experimental phase lasted 6 weeks (30 h of creative thinking lessons 5 h each week) in an English classroom with the integration of the CoRT program. Whereas, the control group followed the standard English curriculum without any CoRT program integration. Traditional teaching methods including lectures, textbook exercises, and rote memorization, were employed. Classroom observations were conducted to gain insights into the student’s experiences during the training program. The post-test was administered one week after the completion of the intervention to minimize immediate post-intervention effects and provided an accurate measure of the sustained impact of the CoRT program.

Two experienced English teachers participated in the experiment, each with similar qualifications and teaching backgrounds: one for the experimental group and one for the control group. The experimental group teacher received training on integrating the CoRT thinking program, covering creative thinking principles, CoRT structure and objectives, and practical classroom strategies, while the control group teacher continued with the standard English curriculum without any additional training. This difference in teacher training could have influenced students’ perceptions of the learning lessons, potentially contributing to the observed differences in creative thinking outcomes and underscoring the importance of teacher training in promoting creativity in education.

Results

The primary objective of this intervention was to evaluate the impact of implementing the CoRT thinking program on the instruction of English subjects for elementary students. To achieve this, the students were divided into two groups based on their performance in a pre-test (TTCT A) designed to assess their creative thinking skills. The experimental group received instruction that integrated the CoRT thinking program with traditional textbook materials, while the control group received instruction following the standard teaching approach. Both groups underwent instruction consisting of four units.

In this section, researchers categorized students’ levels of creative thinking into three categories (high, moderate, and low) based on the range of students’ scores for each factor (Al-Qadri et al., (2021)), and according to the pre and post-tests in the experimental group, as mentioned in Table 1. This table also illustrates the positive influence of the intervention, as it clearly shows the overall positive impact on the post-test, with 11 students in the high category, 16 in the moderate category, and 3 in the low category.

For the purpose study’s hypotheses, researchers computed the means and differences of means for each group. Notably, there was a significant difference in the mean scores observed between the experimental and control groups, as evidenced by the results of pre-post-tests. Data collection was conducted using the TTCT, and subsequent analysis was carried out using MS Excel and SPSS software. This analysis aimed to gauge the effectiveness of the CoRT thinking program in enhancing creative thinking within the context of English subject instruction. Remarkably, all values of Cohen’s effect size indicated a substantial impact of the intervention such as Fluency (t = 7.439; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 1.78), Flexibility (t = 5.393; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 1.04), Originality (t = 7.549; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 1.46), Elaboration (t = 8.073; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 2.21), Title (t = 4.569; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 1.09), Closure (t = 8.231; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 2.1) and overall Creative Index (t = 10.926; p = 0.000; Cohen’s = 2.29) Table 2.

The analysis employed the paired-sample t-test statistical procedure to compare the pre-test and post-test means within the experimental group. This test is well-suited for comparing paired data and assessing whether a significant difference exists between the means of two related groups (Sheskin, 2000).

To explore not only the mean difference but also improvements throughout the distribution, the researcher conducted a Wilcoxon test. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the impact of a thinking program on the enhancement of creative thinking skills among elementary school students through English teaching in Pakistan. The study found that elementary school students in Pakistan perceived creative thinking skills positively. This perception aligns with the idea that creative thinking is well-received, as supported by Al-Faoury & Khwaileh (2014). Moreover, these results are consistent with AlZyoudi’s (2009) findings. Furthermore, the study by Segundo-Marcos et al. (2023) highlighted the significance of classroom methodology as a mediating factor in the development of creative thinking. This aspect is crucial for both the learning processes and the holistic development of children, as evidenced by the clear outcomes of this study.

To explain the current study’s results regarding the levels of creative thinking among Pakistani students, we categorized the students’ scores into three categories: high, moderate, and low, based on pre- and post-tests. The study intervention had a positive impact, aligning with the findings of Alzoubi et al. (2016) and Kampylis (2010). These results also concur with Shaheen’s (2011) study. Notably, the intervention in the closure dimension had the highest impact, with a percentage change of 53.33%. The authors attributed this to several factors, including those identified by Al-Faoury & Khwaileh (2014) and Luqman et al. (2013).

In the same vein, the study’s findings revealed significant differences in the creative thinking skills of 8th-grade students in public schools before and after the implementation of the CoRT thinking program. The program was found to have a positive impact on students’ fluency, flexibility, originality, elaboration, abstractness of thought, resistance to premature closure, and creativity index, as measured by the TTCT. These results support previous studies (Al-Faoury & Khwaileh, 2014; Luqman et al. 2013; Mohammad, 2017; Turkey, 2018). However, the fluency dimension showed significant differences before the intervention when comparing the control and experimental groups based on the pre-test. Nevertheless, the program proved to be very effective in the post-test. Moreover, the researchers attributed this to the innate creative abilities of elementary school students in Pakistan, and the current intervention influenced their creative thinking levels, as explained by their teachers based on their prior knowledge of the student’s capabilities.

On the other hand, the comparisons between pre and post-tests of the experimental groups revealed a significant increase in students’ creative thinking in all dimensions, thanks to the program’s quality, which was prepared by experts and developed in this study by the authors and other specialists in creative thinking. The high-impact results supported all effective programs used in various contexts and environments (Al-Faoury & Khwaileh, 2014; Khawaldeh & Ali, 2016; Mohammad, 2017).

Certainly, the involvement of curriculum supervisors and school leaders in assisting teachers with nurturing students’ creative thinking skills holds paramount significance. This support plays a pivotal role in cultivating an environment that fosters creativity and innovation, ultimately empowering students to thrive in a constantly changing and dynamic global landscape. On the other hand, the researchers also developed a conceptual model for creative potential and transformed its components into measurable indicators of student behavior in classroom settings. These indicators were found to have a direct relationship with certain behaviors of students under specific classroom conditions and during various interventions. The research particularly highlighted an intervention domain where elementary students in Pakistan showed increased engagement. This active participation enabled a fruitful exchange of insights with those conducting the research and supported education sector professionals. Such findings offer valuable guidance for enhancing instructional strategies and designing future educational initiatives.

Study implications

The study bridges theoretical concepts of creative thinking with practical applications in the classroom, offering valuable insights for educators, curriculum designers, and policymakers in enhancing creative thinking skills among students.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the relatively sparse body of research on creative thinking skills in elementary education, particularly in the context of Pakistani public schools. It extends the understanding of how structured programs like the Cognitive Research Trust (CoRT) can influence creative thinking. Also, the effectiveness of the CoRT program in a Pakistani educational setting provides insights into the cross-cultural applicability of creative thinking frameworks, suggesting that these models can be adapted and applied successfully beyond their original cultural contexts. By focusing on 8th-grade students, the study adds to the understanding of creative thinking development at a specific age level, contributing to developmental theories of creativity that emphasize different stages of cognitive and creative growth. Besides, the use of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) for evaluation provides empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of the CoRT program, contributing to the theoretical understanding of how structured thinking programs can be assessed.

Practical implications

The study’s findings can inform curriculum development in public schools, suggesting the integration of structured creative thinking programs like CoRT into the standard curriculum, particularly in language subjects like English and Highlighting the need for teacher training in creative thinking methodologies, this research can influence the design and implementation of professional development programs for educators in the future. Also, the positive outcomes of the study can be used to advocate for policy changes in educational systems, particularly in developing countries like Pakistan, to include creative thinking skills as a core component of the educational curriculum and it can guide school administrators and educational stakeholders in allocating resources for programs that enhance creative thinking, emphasizing the importance of such skills in contemporary education. Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of creating learning environments that foster creativity, guiding schools to design classrooms and activities that encourage creative expression and thinking.

Conclusion

The study found that the CoRT Thinking Program significantly improved students’ creative thinking abilities in Pakistani public schools. This training enhanced students’ idea generation, problem-solving, and creative confidence. Students showed high engagement and enjoyment in the program, underscoring the link between enjoyment and creative thinking. The research suggests integrating such training programs into the curriculum to develop these skills further.

Teacher training is vital for imparting creative thinking techniques and strategies in teaching. Improved facilities and access to diverse materials and training can enhance creativity in students. The study emphasizes the need for a supportive educational environment for creative thinking, requiring adequate teacher training and resources.

Although the Pakistani government recognizes the value of creative thinking, implementation in public schools is lacking due to insufficient facilities and training. Addressing these gaps by updating teaching courses and leveraging government resources is crucial for fostering a conducive environment for creative thinking.

The study also highlights that public school students have untapped creative strengths, often overlooked in traditional education. By recognizing and integrating these strengths into teaching methods, educators can achieve better outcomes and create a more inclusive learning environment.

Data availability

Data can be made available on request.

References

Akhter S, Nordin NRM (2022) Exploring the role of collocation in creative writing among Pakistani learners at secondary level: a corpus-based study. World J Engl Lang 12(2):382–382. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v12n2p382

Al-Faoury O, Khwaileh F (2014) The Effect of Teaching CoRT Program No. (4) Entitled “Creativity” on the Gifted Learners’ Writings in Ein El-Basha Center for Gifted Students. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.11.2249-2257

Aljughaiman AM (2002) Teachers’ perceptions of creativity and creative students. Unpublished dissertation, University of Idaho

Alkahtani K, (2009) Creativity Training Effects Upon Concept Map Complexity of Children with ADHD: An Experimental Study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Glasgow, Scotland

AlKhars D (2013) Creativity in English Language Teaching in Kuwait: A TESOL Study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Exeter

Al-Qadri AH, Zhao W, Li M, Al-Khresheh MH, Boudouaia A (2021) The prevalence of the academic learning difficulties: An observation tool. Heliyon, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08164

Alzoubi AM, Al Qudah MF, Albursan IS, Bakhiet SF, Abduljabbar AS (2016) The Effect of Creative Thinking Education in Enhancing Creative Self-Efficacy and Cognitive Motivation. J Educ Dev Psychol 6(1):117. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v6n1p117

AlZyoudi M (2009) Effects of a creativity training program for breadth and organization on the creative thinking skills of students with learning disability. J Fac Educ UAEU 26:67–87

Anderson D (2002) Creative teachers: Risk, responsibility and love. J Educ 183(1):33–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205740218300104

Aness M, Anwar MN, Khizar A, Muhammad G, Naseer M (2012) Relationship of Creative Thinking with the Academic Achievements of Secondary School. Int Interdiscip J Educ 1(3):44–47

Ashraf I, Ashraf F, Saeed I, Gulzar H, Shah K, Azhar N, Bukhari SR, Ilyas T, Anam W(2015) Reasons for low performance of teachers: a study of government schools operating in Bahawalpur City, Pakistan Int J Acad Res Progress Educ Dev 4(2):105–117. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v4-i2/1764

Aslam HD (2013) Analysis of professional development practices for school teachers in Pakistan: a comparative case study of public and private schools of Pakistan (Punjab). Int J Hum Resour Stud 3(4):311–326. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v3i4.6251

Bleedron B (2005) Education is Everybody’s Business: A Wake-Up Call to Advocates of Educational Change. Rowman & Littlefield Education, Lanham, Maryland

Blewee N (2011) The impact of the De Bono (CoRT) in creative thinking on the development of the flow of ideas in the fifth grade primary students in government schools in Tabuk area Saudi Arabia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Breslin F (2015) Why public schools don’t teach critical thinking–part 1. 9, 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/frank-breslin/why-public-schools-dont-t_b_7956518.html

Brundrett M (2007) Bringing creativity back into primary education. Education 3-13 35(2):105–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270701311879

Case R (2013) The unfortunate consequences of Bloom’s taxonomy. Soc Educ 77(4):196–200

Chandio JH, Khan HMA, Samiullah M (2013) Condition of creative writing in the north and south Punjab. Pak J Commer Soc Sci (PJCSS) 7(2):321–330. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/188093

Cheng Y, Yeh H (2006) A collaborative action research approach to improving vocabulary teaching in Taiwan. McKay, P. Planning and Teaching Creatively within a Required Curriculum for School-Age Learners, 31–57

Chew ES, Abd Hamid MA, Madar AR (2017) Conceptual framework for designing and developing a creativity enhancement module in education incorporating indigenous perspectives. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit 25:67–81

Craft A (2002) Creativity and early years education: A lifewide foundation. Continuum, London; New York

Craft A (2005) Creativity in schools: Tensions and dilemmas. USA and Canada: Routledge

Craft A (2006) Fostering creativity with wisdom. Camb J Educ 36(3):337–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640600865835

Cropley AJ (2003) Creativity in Education & Learning. Routledge Falmer, Bodmin, Cornwall

Cropley A (2004) Creativity as a social phenomenon. Creativity and cultural diversity, 13–23

Davies D, Jindal-Snape D, Digby R, Howe A, Collier C, Hay P (2014) Review: The roles and development needs of teachers to promote creativity: a systematic review of literature. Teach Teach Educ 41(July):34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.03.003

Davis G, Rimm S (1998) Education of the gifted and talented. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA

De Bono E (1970) Lateral thinking. Penguin, London

De Bono E (1986) Edward De Bono’s Cort Thinking Teacher’s Notes: Book 4: Creativity. 2nd Edn, Pergamon Press, ISBN-10: 0080344518, pp 64

De Bono E (1992) Teach your child to think. Penguin, London

De Bono E (2004) Edward De Bono website. http://www.edwDeBono.com/DeBono/index.html

De Bono E (2010) speech at Jesensko srečanje Združenja Manager in GH Bernardin

Dickhut J (2003) A brief review of creativity [online]. www.personalityresearch.org/papers/dickhut.html

Dombaycı MA (2014) Models of thinking education and quadruple thinking. Int J N Trends Educ Their Implic 5(4):12–28

Dumont H, D Istance and F Benavides (eds) (2010) The Nature of Learning. Using Research to Inspire Practice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-en

Fasko Jr. D (2001) Education and creativity. Creat Res J 13(3-4):317–327. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_09

Fazal K, Sarwar U, Nargiza N, Khan B, Qi Z (2023) Creative thinking in Pakistani public schools: a qualitative study of teachers’ perspective and practices. Creat Educ 14(4):637–657. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2023.144042

Feldman D, Benjamin A (2006) Creativity and education: an American retrospective. Camb J Educ 36(3):319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640600865819

Fisher A (2005) Thinking skills’ and admission to higher education. Norwich: University of East Anglia, Centre for Research in Critical Thinking

Fleith D, Renzulli J, Westberg K (2002) Effects of a creative training program on divergent thinking abilities and self-concept in monolingual and bilingual classrooms. Creat Res J 14(3):373–386. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1434_8

Florida R (2014) The rise of the creative class—Revisited. Basic Books, NY

Forrester V, Hui A (2007) Creativity in the Hong Kong classroom: what is the contextual practice? Think Skills Creat 2(1):30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2006.10.003

Gall M, Borg W, Gall J (2003) Educational research: an introduction. Br J Educ Stud, 32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3121583

Gurak-Ozdemir S (2016) Teachers’ perceptions of students’ creativity characteristics

Higgins S, Baumfield V, Lin M, Moseley D (with Butterworth, M), Downey G, Gregson M, Rockett M (2004) Thinking skills approaches to effective teaching and learning: What is the evidence for impact on learners? In Research Evidence in Education Library. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London

Hosseini AS (2011) University student’s evaluation of creative education in universities and their impact on their learning. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 15:1806–1812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.007

IBM Institute for Business Value (2016) Redefining competition: Insights from the Global C-suite study—The CEO perspective. IBM Global Business Services, Somers, NY

Jameel AS, Mohamood DF (2017) The effect of flexibility and fluency strategies on developing creative writing skills in English language subject of the fourth preparatory literary students. Int J Humanit Appl Soc Sci 2(1):37–50

Jarwan F (2007) Teaching thinking concepts and applications (3rd ed) Jordan: Dar Al-Fakr of Publishers and Distributors

Jeffrey B (2005) The redress of creative teaching and learning through specialist programmes and strategic partnerships. Paper given at the creativity in education seminar series (2nd July 2005) Birmingham: University of the West of England

Jeng YC, Hsu SL, Xie J, Lin R, Huang CC (2010) Notice of retraction: the influence of creative-thinking teaching on learning effectiveness. In 2010 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Management Science (ICAMS 2010) (Vol 3, pp 33–38). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAMS.2010.5553294

Kaku M (2014) The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind. Doubleday

Kalim U, Bibi S (2024) Assessing teacher competencies in public schools of Pakistan: a pathway for improving the effectiveness of professional development programs for teachers. SAGE Open 14(2):21582440241236060. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241236060

Kampylis PG (2010) Fostering creative thinking. The role of primary teachers (Jyväskylä Studies in Computing No 115, S. Puuronen, Ed.). University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Kampylis P, Berki E (2014) Nurturing creative thinking. [pdf] International Academy of Education, UNESCO, p. 6. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002276/227680e.pdf

Khan MA (2021) Design-based research to inform the creation of an early childhood education framework for Pakistan. University of Tasmania. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.25959/23250098.v1

Khawaldeh HM, Ali MR (2016) The different impact of SCAMPER and CoRT programs on creative thinking among gifted and talented students. Asian J Multidiscip Stud 4(12):7–14

Kim K (2006) Can we trust creativity tests? A review of the Torrance tests of creative thinking (TTCT). Creat Res J 18(1):3–14

Knight P (2002) Notes on a creative curriculum. Open University Press, London

Lilly FR, Bramwell-Rejskind G (2004) The dynamics of creative teaching. J Creat Behav 38(2):102–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2004.tb01235.x

Luqman MR, Halim AB, Malek TJ, Nour ZB (2013) The level of creativity in English Writing among Jordanian secondary school students. Arts Des Stud 10:25–29. http://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/ADS/article/view/6094

Mindham C (2004). Thinking across the curriculum, In: R Jones R, Wyse D (eds) Creativity in the primary curriculum. London: David Fulton Publishers Ltd

Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training. (2022). Pakistan education statistics 2019-20. Acad Educ Plann Manag. https://pie.gov.pk/SiteImage/Publication/PES%202019-20.pdf

Mohammad WA (2017) The effects of the first part of the CoRT program for teaching thinking (BREADTH) on the development of communication skills among a sample of students from Al al-Bayt University in Jordan. Educ Res Rev 12(2):73–82. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2016.3069

Morgan M, Foster J (1999) Creativity in the classroom. Gifted Educ Int 14(1):29–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142949901400105

Naseer N (2014) Creativity and academic performance of primary school children. Pak J Soc Sci 34(2):597–606. https://pjss.bzu.edu.pk/index.php/pjss/article/view/268

Niemi H, Jakku-Sihvonen R (2011) Teacher Education in Finland. In M. Valenčič Zuljan, & J. Vogrinc (Eds.), European Dimensions of Teacher Education: Similarities and Differences (pp. 33-51). University of Ljubljana & The National School of Leadership in Education. http://www.kenniscentrumonderwijsopvoeding.hva.nl/content/kenniscentrum/lereneninnoveren/publicaties/European-dimensions-in-TE.pdf

Nofel M (2006, July). Athar Barnamaj CoRT fee Tanmeat Al- Tafkeer Al-Ebda’ee Lada AienahMen Al- Mutafawegeen tahseelian Fee Kulliat Al- Oloom Al-Tarbaweah Al- Jame’ah. The Effect of CoRT Program on Developing the Creative thinking for a Sample of Excellent Students in Educational Sciences College. Paper presented at the First Arab Conference for CoRT Experts, Meridian Hotel, Amman, 19-20, July, 6-48

Nomura. (2007) About Nomura. http://www.nomura.com/europe/about_nomura/conferences_about_nri.shtml

Pirzada G (2020) Promoting 21st-century TVET skills in Pakistan: teachers’ perceptions. Pak Soc Sci Rev 4(II):986–1001. https://doi.org/10.35484/pssr.2020(4-II)79

Plucker JA, Beghetto RA, Dow GT (2004) Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educ Psychol 39(2):83–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_1

Pološki Vokić N, Aleksić A (2020) Are active teaching methods suitable for all generation Y students?—creativity as a needed ingredient and the role of learning style. Educ Sci 10(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040087

Primi T, Wechsler S (2018) Creativity and innovation: skills for the 21st Century. Estudos de Psicologia 35:237–246. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752018000300002

Rahman SA, Manaf NFA (2017) A critical analysis of Bloom’s taxonomy in teaching creative and critical thinking skills in Malaysia through English literature. Engl Lang Teach 10(9):245–256

Rashid S, Qaisar S (2016) Developing critical thinking through questioning strategy among fourth grade students. Bull Educ Res 38(2):153–168

Ritchie S, Edwards J (1996) Creative thinking instruction for aboriginal children. Learn Instr 6(1):59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)80004-1

Robinson K (2001) Mind the gap: the creative conundrum. Crit Q 43(1):41–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8705.00335

Schleicher A (ed) (2012) Preparing Teachers and Developing School Leaders for the 21st Century: Lessons from Around the World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264174559-en

Scott G, Leritz L, Mumford M (2004) Types of creativity training: approaches and their effectiveness. J Creative Behav 38(3):149–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2004.tb01238.x

Segundo-Marcos R, Carrillo AM, Fernández VL, González MTD (2023). Age-related changes in creative thinking during late childhood: the contribution of Cooperative Learning. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 101331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2023.101331

Sen RS, Sharma N (2004). Teachers’ conception of creativity and its nurture in children: An Indian perspective. Creativity and cultural diversity, 25–44. In Fryer M (ed) Creativity and cultural diversity. Leeds, England: The Creativity Centre Educational Trust Press

Şenel M, Bağçeci B (2019) Development of creative thinking skills of students through journal writing. Int J Progress Educ 15(5):216–237. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2019.212.15

Serdyukov P (2017) Innovation in education: what works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? J Res Innov Teach Learn 10(1):4–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007

Shade R, Shade PG (2016) The importance of iq, miq, eq, hq & cq. Torrance J Appl Creat 1(2):39–49

Shaheen R (2011) The place of creativity in Pakistani primary education system: an investigation into the factors enhancing and inhibiting primary school children’s creativity. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation)

Sheskin D (2000) Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, London

Sinaga P, Feranie S (2017) Enhancing critical thinking skills and writing skills through the variation in non-traditional writing task. Int J Instr 10(2):69–84. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.1025a

Smith A, Jones B (2010) Enhancing creative thinking in primary schools through the CoRT program. Br J Educ Stud 58(4):391–407

Soh K (2017) Fostering student creativity through teacher behaviors. Think Skills Creat 23:58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.11.002

Starko A (2005) Creativity in the classroom: Schools of curious delight (third ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey

Sternberg RJ, Kaufman JC, Pretz JE (2002) The creativity conundrum: A propulsion model of kinds of creative contributions. Psychology Press

Sternberg R (2006) The nature of creativity. Creat Res J 18(1):87–98. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1801_10

Suliman A, Yunus MM (2014) A glimpse on the re-introduction of English literature in Malaysian secondary schools. Int J Lang Lit 2(2):151–164

Sullivan J (2004) Identifying the best foreign language teachers: teacher standards and professional portfolios. Mod Lang J 88(3):390–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0026-7902.2004.00236.x

Tan AG, Law LC (2004) Creativity for teachers. Marshall Cavendish International, Singapore

The Global Innovation Index (GII) (2015) “Effective Innovation Policies for Development” https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/userfiles/file/reportpdf/GII-2015-v5.pdf

Thomas H, Carmond B, Neumeister K, Millar G, Silvian A (2002) E. Paul Torrance: His Life, Accomplishments, and Legacy. Research Monograph Series National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 310368

Thorne K (2007) Essential creativity in the classroom. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group

Topping KJ (2023) Improving Thinking in the Classroom: What Works for Enhancing Cognition. Taylor & Francis

Torrance E (1972) Can we teach children to think creatively? J Creat Behav 6:114–143

Torrance E (1977) Creativity in the classroom. Washington, D. C.: National Education Association

Torrance E (1995) Why fly? A philosophy of creativity. Ablex Publishing Corporation, Norwood, New Jersey

Torrance E (1998) Torrance tests of creative thinking; norms-Technical Manual figural (Streamlined) Forms A and B. Scholastic Testing Service, Inc, Bensenville, IL

Torrance E, Myers R (1970) Creative learning and teaching. Dodd-Mead, New York

Torrance E, Ball O, Safter (1992) Torrance tests of creative thinking; streamlined scoring guide figural A and B. Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service, Inc

Turkey J (2018) The level of creative thinking skills among gifted and ordinary students in Tafila governorate. J Stud Educ 8(1):68–80. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v8i1.12098

Turner-Bisset R (2007) Performativity by stealth: a critique of recent initiatives on creativity. Education 3-13 35(2):193–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270701318007

Vong K (2008) Developing creativity and promoting social harmony: the relationship between government, school and parents’ perceptions of children’s creativity in Macao-SAR in China. Early Years Int J Res Dev 28(2):149–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140802065599

Wilson V (2000) Education forum on teaching thinking skills report. Edinburgh: The Scottish Council for Research in Education

Winner E, TR Goldstein and S Vincent-Lancrin (2013) Art for Art’s Sake? The Impact of Arts Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264180789-en

Zaiyadi, zairil, Abdullah E, Muhamad SH, Mustapha G (2016) Creative thinking in academic essay writing GLIT E-J Inf Technol Lang Pract 2:11–16

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Kiran Fazal. Data curation: Kiran Fazal. Funding acquisition: Qi Zhan Yong. Investigation: Kiran Fazal. Methodology: Kiran Fazal, Qi Zhan Yong. Resources: Uzma Sarwar. Validation: Kiran Fazal. Writing—original draft: Kiran Fazal. Writing—review & editing: Kiran Fazal, Nargiza Nuralieva. Analysis: Kiran Fazal, Abdo HasanAL-Qadri.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted by the local ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. The research was approved on November 2, 2021, with letter reference no. (AR 2021-11-09) by the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Education Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China. This research involves the completion of a quasi-experimental effort comprised of training related to creative thinking skills via the CoRT thinking program. The participants of this study include elementary school teachers teaching English subjects and the 8th-grade students of English subject classes in public schools. All the study participants were informed about the purpose of the research, and the necessary permission was taken before data collection. The researcher obtained the participant consent from parents and the School Head before the commencement of the study. The information collected was used only for academic purposes and kept confidential.

Informed consent

Informed consent was gathered from all participating Pakistani public school students. Confidentiality was maintained by not requesting names or any other information that would identify the students involved. The subjects were informed of their right to withdraw from the investigation at any time. Parents’ and school principals’ consent was taken as well.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fazal, K., Sarwar, U., Nuralieva, N. et al. Cultivating creative thinking in Pakistani public schools: a quasi-experimental study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1470 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04009-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04009-x