Abstract

The vaccination against COVID-19 has torn societies apart. Against this background we evaluate three interrelated research questions: (1) does vaccination polarize citizens even after the COVID-19 pandemic has faded; (2) do opinions about vaccination correlate with group formation and identification, and (3) do we observe opinion-based affective polarization regarding vaccination in the post-pandemic era? Based on two original surveys from Switzerland in early 2022 and late 2023, our results highlight that respondents have distinct opinions about vaccination, but that only pro-vaccination respondents have formed an opinion identity. We also observe an asymmetric affective polarization: pro-vaccination respondents show higher levels of liking toward other pro-vaccination respondents but significant dislike toward anti-vaccination respondents, while the same does not hold true for anti-vaccination respondents. Overall, affective polarization toward vaccination is less pronounced in the aftermath of the health crisis than during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, at a time when globalization is boosting the threat of pandemics, caution is warranted, as an increasing salience of vaccination could widen the divide again.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vaccination against COVID-19 became an issue marked by an unprecedented level of tension and controversy (Bor et al. 2022; Henkel et al. 2022; Sprengholz et al. 2023). At the height of the pandemic, the level of conflict between supporters and opponents appeared to exceed that of ethnic prejudice (Bor et al. 2022). Such conflicts leave their mark on societies, implying lower levels of social cohesion, discriminatory behavior toward outgroups, and fierce political conflict (Ballone et al. 2023; Bor et al. 2022; Henkel et al. 2022; Schuessler et al. 2022; Wagner and Eberl, 2024). In the context of this extraordinary conflict, the transition from the acute phase of the pandemic to a post-pandemic world raises the question of whether vaccination still polarizes citizens and leads to intergroup conflict between pro- and anti-vaccination groups.

On the one hand, the severity and ferocity of the intergroup-conflict may lead us to believe that even after the pandemic has ended, vaccination as a political issue still has the potential to engender identification, and ultimately affectively polarize citizens, i.e., lead to dislike between pro- and anti-vaccination groups (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015; Wagner, 2024; Wagner and Eberl, 2024). On the other hand, research in social psychology and political science has linked the emergence of opinion-based identities and opinion-based affective polarization to divisive events such as referenda, crises, or natural disasters like pandemics. These events make issues salient and political actors politicize them, leading to the formation of opinion-based groups and affective polarization (Hobolt et al. 2021; McGarty et al. 2009; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Simon et al. 2019). Thus, in a post-pandemic world, vaccination may not remain a polarizing issue as the issue itself has become less salient and is not being mobilized by political actors (Hernández et al. 2021).

To address this conundrum, we evaluate whether attitudes towards vaccination against infectious diseases have the potential to create opinion-based identities and subsequently lead to affective polarization between pro- and anti-vaccination groups. More specifically, we tackle three interrelated research questions:

First, we examine whether vaccinations continue to polarize citizens even after the COVID-19 pandemic has ended, i.e., whether distinct, opposing opinions on vaccination persist (RQ 1). Second, we investigate whether opinions on vaccination continue to correlate with the formation of social identities that are constructed around pro- and anti-vaccination positions after the peak of the pandemic (RQ 2). During the health crisis, such group formation was observed where people identified with others who shared the same opinion on containment measures or had the same vaccination status (Henkel et al. 2022; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Wagner and Eberl, 2024).

Third, we evaluate the existence of opinion-based affective polarization in relation to vaccination (RQ 3). This form of polarization implies a positive emotional attachment to the ingroup and hostility toward the outgroup and has often been associated with partisan conflict (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015). Yet, social identities based on shared opinions have also been shown to lead to affective polarization (Balcells et al. 2023; Hobolt et al. 2021; McGarty et al. 2009; Schieferdecker et al. 2024).

To scrutinize the presence of opinion-based identity and affective polarization with respect to vaccination, we leverage original survey data collected in early 2022 and late 2023 in Switzerland—a country with high levels of conflict surrounding the COVID-19 vaccination during the pandemic, comparatively low levels of vaccination uptake, and recurring referenda on the issue, such as in June 2024.Footnote 1 Our fine-grained analyses of various survey measures of opinion-based identity and affective polarization reveal that vaccination has partially lost its potential to evoke identification and affective polarization in the aftermath of the pandemic.

More precisely, while opinions about vaccination against infectious diseases are polarized, they do not align with major partisan or left–right conflict lines. Furthermore, these opinions on vaccination constitute only a weak foundation for group identification. While pro-vaccination individuals appear to share a certain degree of common identity, these opinions on vaccination provide only a tenuous basis for group identification for anti-vaccination advocates. Third, using three distinct indicators of affective polarization, our analyses reveal that in contrast to the supporters, opponents of vaccination are only slightly affectively polarized. Additionally, we show that affective polarization regarding the (COVID-19) vaccination was higher during the pandemic in early 2022 than in late 2023, supporting the expectation that salience and politicization matter for the formation of opinion-based affective polarization (Hernández et al. 2021).

Given the importance of vaccine-related divisions for public health policies and their consequences for the political and social fabric of democratic societies (Druckman et al. 2021b; Gadarian et al. 2021; Ruggeri et al. 2024; Stoetzer et al. 2022), our study has crucial implications in an era where globalization amplifies the threat of pandemic emergencies and accelerates global disease transmission (Taylor, 2019). Against this background, caution is warranted as the omnipresent threat of infectious diseases could swiftly make the demand for vaccination acute again, thereby reopening the societal rift.

Identity and opinion-based affective polarization regarding vaccination

While ideological polarization is a key concept in political science that refers to a divergence of political preferences among voters, parties, or politicians (Fiorina and Abrams, 2009), affective polarization has recently moved from a bit player to center stage. Affective polarization refers to a difference in feelings toward the ingroup compared to the outgroup (Iyengar et al. 2012; Iyengar and Westwood, 2015). It has largely been studied in the context of partisanship and thus has been defined as emotional attachment to ingroup partisans and hostility toward outgroup partisans (Iyengar et al. 2019; Wagner, 2024). While ideological disagreement between parties contributes to such an emotional distance (Dias and Lelkes, 2022; Orr and Huber, 2020; Rogowski and Sutherland, 2016), social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) forms the basis of this form of polarization (Iyengar et al. 2012). Scholars have argued that partisanship has become more than just a tally of rational considerations (Huddy et al. 2015) but rather integral to people’s social identity. Thus, partisanship is related to a sense of belonging that becomes crucial for group members’ self-esteem, which ultimately may lead to a tendency for positive ingroup evaluations and clear negative emotions toward the outgroup (Huddy et al. 2015; Tajfel, 1974, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1979).

Because partisan identity is far from the only political identity that exists or matters, social identity theory offers the flexibility to study identification and affective polarization among groups other than political parties (Hobolt et al. 2021; Wagner, 2024). Such group conflict may arise from identification with groups united by a common opinion, such as Brexit, territorial independence, or COVID-19 policies (Balcells et al. 2023; Hobolt et al. 2021; Schieferdecker et al. 2024).

In this vein, research in social psychology has advanced the concept of opinion-based groups, which are social groups that form around opinions on specific issues (Bliuc et al. 2007; McGarty et al. 2009). Opinion-based allegiances tend to form around controversial and salient issues that prompt diametrically opposed groups to maintain the status quo (McGarty et al. 2009; Simon et al. 2019). For example, Hobolt et al. (2021) argue and show that the Brexit referendum in the UK created two opposing opinion-based groups, Leavers and Remainers, which are affectively polarized against each other. For opinion-based affective polarization to emerge, Schieferdecker et al. (2024) identify three conditions: disagreement on the issue, identification with the respective opinion ingroup, and affective bias (positive feelings toward the ingroup and negative feelings toward the outgroup). In their analysis, the authors present evidence of such an opinion-based affective polarization around COVID-19 containment measures in Germany (Schieferdecker et al. 2024). Put differently, opinion-based affective polarization requires ideological disagreement on the issue at hand, identification with others who share the same opinion and affective bias implying positive feelings toward the ingroup and negative feelings toward the outgroup (Hobolt et al. 2021; McGarty et al. 2009; Schieferdecker et al. 2024).

Against this background, we expect that there are different positions on vaccination against infectious diseases (ideological polarization). Furthermore, we anticipate that people tend to identify with others who share their position on vaccination (opinion-based identification). Ultimately, such group identification leads to the development of evaluative biases in favor of the opinion-based ingroup and against the outgroup (affective bias). Applied to our context this would mean that pro-vaccination individuals would feel positively about other pro-vaccination individuals but negatively about anti-vaccination individuals, while the opposite would hold true for anti-vaccination individuals.

Figure 1 is a conceptual illustration featuring two fictional characters, Anna and Peter, along with their positions on vaccination, their identification with specific opinion-based groups and their feelings toward pro- and anti-vaccination individuals. While Peter supports vaccinations, Anna opposes them (upper part of Fig. 1). Based on their position on vaccination, both identify themselves with their respective opinion-based group and thus with others who share their opinion. In this vein, we expect vaccinations to create opinion-based identities (middle part of Fig. 1). These identification processes are crucial for the development of affective biases. Intergroup competition leads to positive feelings toward the ingroup to protect self-esteem and negative feelings toward the outgroup. Thus, if our arguments are supported, our data would show that Anna, as an anti-vaccine individual, would feel warm and positive toward other anti-vaccine individuals and cold and negative toward pro-vaccine individuals. The opposite pattern should be observed for Peter (lower part of Fig. 1).

This is an adapted version of the conceptual figure shown by Filsinger and Freitag (2024).

Nevertheless, the question of whether such identification and affective polarization processes regarding vaccination occur in a post-pandemic setting reveals two contrasting perspectives and expectations. On one hand, COVID-19 vaccinations have caused significant intergroup conflict during the height of the pandemic (Bor et al. 2022; Henkel et al. 2022; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Wagner and Eberl, 2024). This conflict over vaccinations has been highly contentious, as evidenced by both discriminatory behavior toward unvaccinated individuals (Bor et al. 2022; Schuessler et al. 2022) as well as (violent) protests of unvaccinated individuals in many countries. The conflict over vaccination has profoundly divided societies and brought to light deeply rooted values about the right to one’s own life on the one hand and social responsibility on the other. Such conflicts are unlikely to disappear in the blink of an eye. In this regard, the deeply rooted ferocity and intensity of the conflict lead us to our first expectation that even in a post-pandemic setting we can observe opinion-based identification with groups that support and oppose vaccination as well as the tendency of pro-vaccination individuals (anti-vaccination) to view anti-vaccination (pro-vaccination) individuals negatively and pro-vaccination (anti-vaccination) individuals positively.

On the other hand, one might expect such forms of identity and affective polarization to be very strongly linked to unprecedented events or long-lasting political conflicts and the associated political mobilization. As the pandemic has officially come to an end as a large-scale and drastic event, these conflicts have become less salient and less politicized by political parties, interest groups, and the media than they were during the pandemic. Consequently, the issue of vaccination has become less prominent and is no longer the focus of public and party-political debate in the aftermath of the pandemic. In this respect, as opinion-based polarization has generally only been observed in the context of highly salient and politicized issues (Balcells et al. 2023; Hobolt et al. 2021; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Simon et al. 2019), we might expect that attitudes toward vaccination in the post-pandemic period will not form the basis of a social identity or lead to affective polarization. Thus, a contrasting expectation would be that in a post-pandemic setting we would observe less opinion-based identification with groups that support and oppose vaccination as well as a weaker tendency of pro-vaccination individuals (anti-vaccination) to view anti-vaccination (pro-vaccination) individuals negatively and pro-vaccination (anti-vaccination) individuals positively. Our aim is to evaluate which expectation is accurate and what kind of intergroup conflict between pro- and anti-vaccination groups exists in the post-COVID-19 era.

Current study

Participants

We conducted an original survey in Switzerland between November and December 2023 fielded by the survey company Kantar. All respondents are at least 18 years old, have consented to participate in the survey, and are Swiss citizens. The sampling strategy was based on quotas for age, gender, education, and language, which were achieved with minor deviations. For this study, we are using around 1000 respondents (see section A, Table 1 and section L in the online supplemental materials). The survey starts with socio-demographic questions on age, sex, and education. Subsequently, respondents were asked about their attitudes toward vaccination against infectious diseases as well as related and established questions about opinion-based identity and affective polarization. Due to the large number of different measures, they are presented in the respective sections for ease of reading.

For some aspects of our endeavor, we can compare the situation in the post-pandemic period to data collected during the COVID-19 health crisis (position on vaccination, thermometer scores, character traits, see below). This survey was conducted by SurveyEngine between January and March 2022 (Filsinger and Freitag, 2024) using quota sampling for gender, age, and education as well as language with a target sample of 1000 respondents (see section A, Table 2 and section L in the online supplemental material). Although the survey was not specifically fielded to investigate our central research question, it includes questions on COVID-19 vaccinations, such as respondents’ attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccination, as well as established questions about affective polarization (thermometer scores) and stereotypes (character traits). We will revisit this data in the respective sections.

Analytically, we rely on predicted values based on linear regression models that include position on vaccination, opinion-based identity (where appropriate), and a standard set of covariates (age, sex, education, language, income situation, and left–right self-placement). We distinguish between pro- and anti-vaccination groups to tease out potential differences in position on vaccination, group formation, identification, affective bias, and social distance (Bor et al. 2022; Schieferdecker et al. 2024). In the supplementary material, we also replicate the analyses by distinguishing between strong supporters, weak supporters, weak opponents, and strong opponents (see Figs. 2–8 in the online supplemental material).

Results

Position on vaccination

RQ 1 asks whether vaccination remains a polarizing issue in society even after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were asked to indicate their position regarding the use of vaccinations against infectious diseases. Respondents indicated their position on a scale from 0 (fully support) to 10 (fully oppose; (Mean (M)Sample = 4.8, standard deviation (SD) = 3.5). It is interesting to note that the general attitudes toward vaccination in our sample differ from what has been shown in other studies for specific COVID-19 vaccinations (Henkel et al. 2022; Miller et al. 2022; Wagner and Eberl, 2024). In our sample, the attitudes toward vaccination are spread across the entire spectrum, with a mean value that is slightly biased toward a favorable position. The upper left panel of Fig. 2 shows the distribution of positions on vaccination. The most common positions are full support (19 percent), neutral position (14 percent), and full opposition (13 percent). Overall, supporters constitute around 42 percent, neutral respondents around 14 percent, and opponents around 44 percent of respondents. The distribution suggests that vaccination remains a polarized issue, with a majority of respondents either supporting or opposing it, albeit to varying degrees. Yet, a significant portion of the sample has no dedicated position on vaccination which indicates a lower salience of the topic compared to the height of the pandemic.

The upper left panel shows the distribution of the position on vaccination in the sample. The upper middle and upper right, lower left, lower middle, and lower right panels show the predicted position on vaccination when using linear regression models with party identification (from the far left SP to the far right SVP) (middle right), left–right self-placement (upper right), education (lower left), sex (lower middle) and age (lower right) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, left–right self-placement, income and language using clustered standard errors at the cantonal level. Full models are presented in the Supplementary material Table 3. Higher values indicate opposition to vaccination.

To evaluate whether these positions on vaccination are aligned with other societal conflicts, we examined the extent to which they differ between political parties and ideological groups (upper middle and right panel in Fig. 2), and levels of education, sex, and age (lower panels in Fig. 2). As shown, attitudes toward vaccination do not differ according to education, sex, and age. These coefficients are not significantly related to the position on vaccination (see Table 3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, there is no substantial evidence that, on average, positions on vaccination in Switzerland vary significantly by party affiliation apart from supporters of the SVP and supporters of very small parties. These tend to be slightly more opposed to vaccination. Yet, the differences are rather a matter of degree than principle.

Left-right ideology correlates with the position on vaccination, as right-wing respondents tend to express more opposition to vaccination than left-wing respondents. While ideological groups do seem to differ significantly in their attitudes toward vaccination, this difference is not very substantial. For instance, people on the far left of the political spectrum score a 4 on the 0–10 scale, indicating a moderately pro-vaccination position. People on the far right of the political spectrum score 5.6 on a scale of 0–10, reflecting moderate opposition to vaccination. Thus, a shift in the ideological position from one end to the other, results in less than half a standard deviation shift in the position on vaccination. To put this in another context, additional analyses demonstrate that the correlation between left–right ideology and position on vaccination is a quarter of the relationship between left–right ideology and position on migration (not shown here, but available on request).

This relatively small substantial difference between ideological camps may indicate that the conflict over vaccination is no longer being actively addressed by political parties or actors. If political actors were to politicize and mobilize voters based on the issue of vaccination, we would expect significant differences between the groups. Overall, while attitudes toward vaccination against infectious diseases are polarized in Switzerland in late 2023, they do not vary significantly across the main political conflict lines.Footnote 2

In comparison to early 2022 and specifically to attitudes concerning COVID-19 vaccinations, we observe some notable differences (see Fig. 1 in the supplementary material). First, support for COVID-19 vaccinations was highly polarized between supporters and opponents, with supporters making up 70 percent of the respondents. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test supports this claim by showing a significant difference between the 2022 and 2023 data. Second, attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccination were more closely aligned with political partisanship, with lower levels of support for the vaccination among voters of the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and voters of niche parties.Footnote 3 This suggests that the issue of vaccination was more politicized and ideologically polarized by political parties during one of the pandemic’s peak periods.

Identity-formation regarding opinion on vaccination

Focusing on identity-formation regarding opinions on vaccination, we have simplified our measure of group status. Instead of using the full 11-point scale, we excluded respondents who were undecided on the issue (see also Schieferdecker et al. 2024). We subsequently dichotomized respondents into supporters and opponents: when respondents scored 4 or less, they were categorized as supporters. Opponents were categorized based on scores of 6 and above. In the supplementary material, we report our findings when we classify the respondents as strong supporters (position on vaccination < 3), weak supporters (position on vaccination >2 and <5), weak opponents (position on vaccination >5 and <9), and strong opponents (position on vaccination >8). Our conclusions remain largely unchanged across classifications.

RQ 2 investigates whether vaccination attitudes correlate with processes of identification with the respective opinion-based groups. After indicating their position on the issue of vaccination, respondents who were not neutral were asked five questions about whether they identified with their respective opinion-based group (e.g., I have a lot in common with other [respondent issue identity]). Answer scales ranged from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree” ((M)Sample = 3.05, SD = 0.95; (M)Supporter = 3.36, SD = 0.80; (M)Opponents = 2.76, SD = 0.99). These questions were adapted from the partisanship literature (Huddy et al., 2015). The full wording of the questions can be found in section L of the supplementary material.

Does one’s position on vaccination correlate with the formation of opinion-based identities? Fig. 3 displays the predicted identification with the respective ingroup for both supporters and opponents based on linear regression models that include covariates (full results in Table 5 in the supplementary material). As can be inferred, supporters identify more with their respective opinion-based ingroup (ŷSupporter = 3.4; CI = [3.31, 3.48]) compared to opponents (ŷOpponents = 2.8; CI = [2.66, 2.87]). This difference between the two groups is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (see Table 5 in the online supplementary material). In addition, strong supporters exhibit the highest identification, followed by weak supporters. In contrast, both weak and strong opponents display similarly low levels of identification with other vaccination opponents (see Fig. 2 in the supplementary material).

This figure shows the predicted level of opinion-based identity when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, left–right self-placement, income, and language using standard errors clustered at the cantonal level. The difference is statistically significant on a 95% level. Full models are presented in the supplementary material Table 5. Higher scale values imply a stronger identity.

While the results suggest that opinion-based identification regarding attitudes on vaccination has taken place in 2023, the strength of this identification is not immediately evident. Even among strong vaccination supporters, identification is only about one standard deviation above the neutral score of 3, which could be considered moderate (see Fig. 2 in the online supplemental material). This level of identification is lower than that reported by Henkel et al. (2022) for late 2021 and mid-2022. However, this identification based on vaccination is on par with a recent study on rural and urban identities (Zumbrunn, 2024), but also lower than what studies on partisanship traditionally record (Mason, 2018; West and Iyengar, 2022). Thus, our results indicate that identification based on opinions about vaccination does exist. Yet, they also lend credibility to the expectation that vaccination is a less salient issue in a post-pandemic context, leading to lower levels of identity-formation for opinion-based groups. Nevertheless, a more thorough examination of this identification process may be a task for future research.

Affective polarization: dislike between supporters and opponents of vaccinations

In the next step, we scrutinize whether there are affective biases between the groups of supporters and opponents. Specifically, we investigate whether pro-vaccination individuals like other pro-vaccination individuals and dislike anti-vaccination individuals and vice versa. Our first indicator of affective polarization is the classic thermometer question, which asks respondents to rate supporters and opponents of vaccination on a scale from 0, indicating “very cold and negative” to 10, indicating “very warm and positive” (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019).

The left panel of Fig. 4 shows the predicted thermometer scores for the two groups separated by group status (pro-vaccination vs. anti-vaccination) in the post-pandemic period of 2023 based on linear regression models with covariates. It illustrates that feelings toward the respective groups differ between pro- and anti-vaccination groups. Starting with feelings toward vaccination supporters (blue) in 2023, on average, vaccination advocates feel positive and warm toward other advocates of vaccination (ŷSupporters = 7.0; CI = [6.63, 7.37]). Interestingly, and contrary to our expectations, vaccination opponents do not feel negatively toward supporters but are even slightly positive with a score above the neutral value of 5 (ŷOpponents = 6.2; CI = [5.85, 6.52]). Overall, both groups feel rather positive toward pro-vaccination individuals, but proponents of vaccination more so. The difference between supporters and opponents is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

The left panel of this figure shows the predicted thermometer ratings towards vaccination supporters (blue) and opponents (magenta) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, opinion-identity, left–right self-placement, income, and language using standard errors clustered at the cantonal level in 2023. Full models are presented in the supplementary material Table 6. The right panel of this figure shows the predicted thermometer ratings towards COVID-19 vaccination supporters (blue) and opponents (magenta) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, left–right self-placement, and income using robust standard errors in 2022; Full models presented in supplementary material Table 8. Scale ranges from 0, “very cold and negative” to 10, “very warm and positive”.

Regarding feelings toward vaccine opponents (magenta) in 2023, we observe that vaccine supporters feel rather cold and negative toward them (ŷSupporter = 3.3; CI = [3.02, 3.57]). However, opponents do not feel positive toward other opponents, but rather neutral (ŷOpponents = 5.1; CI = [4.81, 5.34]). Thus, it seems that we observe affective polarization regarding vaccination but only on the part of vaccination supporters who indeed feel positive toward their fellow supporters and negative toward their opponents, indicating asymmetric affective polarization. This asymmetric affective polarization replicates findings from previous research during the pandemic, showing higher levels of negative feelings from vaccinated individuals toward unvaccinated individuals (Bor et al. 2022; Filsinger and Freitag, 2024; Henkel et al. 2022).

The right panel in Fig. 4 shows the predicted thermometer scores for the two groups separated by group status (pro-vaccination vs. anti-vaccination) during the pandemic in early 2022 based on linear regression models with covariates. Clear patterns of affective polarization emerge. Toward vaccination advocates (blue), COVID-19 vaccination advocates feel, on average, very positive and warm (ŷSupporters = 8.9; CI = [8.76, 9.03]), while opponents feel slightly negative and cold toward them (ŷOpponents = 4.8; CI = [4.44, 5.09]). Contrary to our findings for 2023, regarding vaccination opponents (magenta), we observe that other opponents feel positive and warm (ŷOpponents = 6.7; CI = [6.35, 7.07]). Conversely, supporters feel very cold and negative toward opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations (ŷSupporters = 2.8; CI = [2.60, 2.97]). Compared to post-pandemic times, supporters and opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations seem to view each other much more negatively while being much more positive toward their fellow ingroup members during the pandemic.

In addition, we performed Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to investigate whether the distributions are indeed different when comparing our 2022 and 2023 data. For the thermometer ratings for vaccination supporters, we observe a maximum difference of 0.33 between the empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of 2023 and 2022, significant at the 95% confidence level. For the thermometer ratings for vaccination opponents this maximum difference is 0.14, also significant at the 95-% confidence level. Visual inspection using box plots indeed shows that vaccination supporters were more liked and that vaccination opponents were more disliked in the 2022 sample than in the 2023 sample (see Table 19 and Fig. 9 in the online supplemental material).

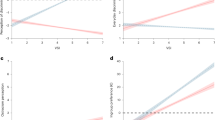

A more rigorous test of affective polarization is depicted in Fig. 5. In the left panel, shown in blue, we present the absolute difference between the two thermometer scores to measure opinion-based affective polarization regarding vaccinations in the post-pandemic period in 2023. As can be seen, the thermometer scores that respondents assign to supporters and opponents differ significantly. For vaccination supporters, we find a predicted difference of ŷSupporters = 4.7; CI = [4.34, 5.12]), which is almost half of the total scale. For opponents, the difference is smaller but still considerable with around ŷOpponents = 3.9; CI = [3.53, 4.20]. These findings indicate that there is affective polarization regarding vaccination and that this polarization is stronger for supporters than for opponents of vaccination. Again, this mirrors research showing asymmetric polarization during the pandemic but now in a post-pandemic context (Bor et al. 2022; Filsinger and Freitag, 2024; Henkel et al. 2022).

The left panel of this figure shows the predicted level of affective polarization measured as the absolute difference between the thermometer ratings for supporters and opponents (blue) and measured as the difference between the thermometer rating for opponents and the thermometer rating for supporters (magenta) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, opinion-identity, left–right self-placement, income, and language using standard errors clustered at the cantonal level in 2023. Full models are presented in the supplementary material Table 7. The right panel of this figure shows the predicted level of affective polarization measured as the absolute difference between the thermometer ratings for supporters and opponents (blue) and measured as the difference between the thermometer rating for opponents and the thermometer rating for supporters (magenta) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, left–right self-placement, and income using robust standard errors in 2022. Full models are presented in supplementary material Table 9.

Showing the difference between the thermometer ratings for vaccination opponents and vaccination supporters in magenta in the left panel of Fig. 5 further corroborates the finding of an asymmetrical affective polarization. Lower values imply positive feelings toward supporters and negative feelings toward opponents, while higher values imply the opposite. With a predicted value of ŷSupporters = −3.7; CI = [−4.32, −3.09], supporters of vaccinations are affectively polarized in favor of their fellow supporters. Remarkably, the anti-vaccination group also shows a slightly positive attitude toward the pro-vaccination group (ŷOpponents = −1.3; CI = [−1.63, −0.59]). This contradicts the idea of affective polarization for this opinion group as they do not express more positive feelings toward their ingroup than their outgroup. A possible explanation is that anti-vaxxers have found their counterparts more in the respective governments that imposed vaccinations and restrictions during the pandemic rather than in their fellow citizens.Footnote 4

Regarding the data on COVID-19 vaccinations in early 2022, (right panel of Fig. 5) we find that vaccination supporters have an average predicted absolute difference (blue) of ŷSupporters = 6.3; CI = [6.04, 6.51], which is more than half of the total scale and higher than the difference for supporters in 2023. For opponents the difference is smaller but still sizeable at around ŷOpponents = 3.0; CI = [2.57, 3.45]. While these findings also indicate an asymmetric affective polarization between supporters and opponents, this polarization is generally higher for supporters and similar in size for opponents in 2022 compared to 2023.

Showing the difference between the thermometer ratings for vaccination opponents and vaccination supporters in magenta further corroborates the finding of an asymmetrical affective polarization as well as the finding that affective polarization was stronger in 2022 than in 2023. With a predicted value of ŷSupporters = −6.1; CI = [−6.37, −5.86], supporters of vaccinations demonstrate a clear positive affective bias in favor of other supporters of vaccinations and are thus affectively polarized. Remarkably, the anti-vaccination group shows only a slightly positive attitude toward other anti-vaccination individuals (ŷOpponents = 1.9; CI = [1.43, 2.47]) indicating that this group is affectively polarized in 2022 and, in particular, seems to be more polarized than vaccination opponents in 2023.

Again, to give additional weight to this interpretation, we performed Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, which indicate that both samples are significantly different. For the absolute difference measure, we observe a maximum difference of 0.21 between the ECDFs of 2023 and 2022, which is significant at the 95-% confidence level. For our second measure, this maximum difference is 0.21, which is also significant at the 95-% confidence level. Visual inspection using box plots indeed demonstrates higher polarization in the 2022 sample than in the 2023 sample (see Table 19 and Fig. 9 in the online supplemental material).

Overall, three conclusions can be drawn from the thermometer results. First, vaccination supporters are affectively polarized, expressing warmth toward other supporters and dislike toward opponents of vaccination. Second, vaccination opponents do not mirror such a tendency toward ingroup favoritism but rather show indifference toward their ingroup and slightly positive feelings toward their outgroup. This finding of asymmetric affective polarization echoes previous research showing similar trends during the pandemic (Bor et al. 2022; Filsinger and Freitag, 2024; Henkel et al. 2022). In the supplementary material, we replicate these analyses using a fourfold categorization of vaccination groups (Tables 6 and 7, Figs. 3 and 4). The patterns remain largely the same, indicating that strongly pro-vaccination individuals, in particular, are affectively polarized. Third, while affective polarization in 2023 is still asymmetric (driven by vaccination supporters), it appears to be lower than during the salient times of the pandemic in early 2022.

Affective polarization: stereotypes between supporters and opponents of vaccinations

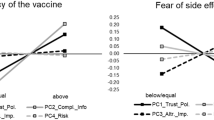

To increase the reliability of our investigation, we employ a second commonly used measure of affective polarization, in which respondents rate the extent to which certain character traits apply to the ingroup and the outgroup (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; West and Iyengar, 2022). This measure taps into stereotypical evaluations of different groups, providing us with an additional indicator of intergroup conflict. We asked respondents to rate to what degree a) supporters of vaccinations and b) opponents of vaccinations exhibit two positive and two negative character traits on a scale from 1 (“does not apply at all”) to 5 (“fully applies”). The two positive traits are “honesty” and “open-mindedness” while the two negative traits are “arrogance” and “selfishness”. This alternative measure of affective polarization reveals a similar although less pronounced pattern of affective polarization regarding vaccination.

Figure 6 is analogous to Fig. 4 and shows the predicted character trait ratings assigned to supporters (blue) and opponents (magenta) by group status (pro-vaccination vs. anti-vaccination). The upper left panel of Fig. 5 shows whether supporters and opponents perceive supporters to be arrogant. Supporters do not consider other supporters to be arrogant (ŷSupporters = 2.3; CI = [2.17, 2.47]), and opponents perceive the character trait of arrogance in the supporters only marginally more strongly (ŷOpponents = 2.7; CI = [2.56, 2.80]). However, the difference is significant at the 95% confidence level. Regarding the perception of opponents’ arrogance (magenta) supporters slightly believe that opponents are arrogant (ŷSupporters = 3.1; CI = [2.92, 3.20]), while opponents have a slight tendency to think that other opponents are not arrogant (ŷOpponents = 2.8; CI = [2.60, 3.01]). The difference between both groups is significant at the 90% confidence level (see Tables 10 and 11 in the online supplementary material).

This figure shows the predicted perceived character traits of vaccination supporters and opponents) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, opinion-identity, left–right self-placement, income, and language using standard errors clustered at the cantonal level; scale ranges from 1 “does not apply at all” to 5 “fully applies”. Full models are presented in supplementary material Tables 10 and 11.

Regarding the second negative trait (selfishness), the upper right panel in Fig. 6 shows a similar pattern. Supporters do not believe other supporters to be selfish (ŷSupporters = 2.2; CI = [2.03, 2.30]). Opponents do not think supporters are selfish either, although the predicted value is higher and significantly different (ŷOpponents = 2.6; CI = [2.17, 2.47]). Concerning whether opponents are perceived as selfish, we find that supporters indeed believe that they are selfish (ŷSupporters = 3.3; CI = [3.19, 3.48]) while opponents do not believe that other opponents are selfish (ŷOpponents = 2.8; CI = [2.61, 2.92]). The difference between both groups is significant at the 95% confidence level (see Tables 10 and 11 in the online supplementary material).

The bottom panels of Fig. 6 show the assignment of positive traits to the two groups. Consistent with in-group favoritism, advocates believe that other advocates are open-minded (ŷSupporters = 3.5; CI = [3.42, 3.66]). Vaccine opponents perceive proponents as significantly less open-minded, but the difference is not substantial (ŷOpponents = 3.3; CI = [3.13, 3.39]). However, regarding opponents of vaccinations, pro-vaccine individuals believe that vaccine opponents are not open-minded (ŷSupporters = 2.2; CI = [2.02, 2.36]). In contrast, vaccination opponents seem to be more convinced that opponents are open-minded (ŷOpponents = 3.0; CI = [2.81, 3.12]). The difference between both groups is significant at the 95% confidence level.

Honesty was the last characteristic that respondents rated. Here, we observe only marginal differences between the two groups. Supporters believe other supporters to be honest (ŷSupporters = 3.6; CI = [3.43, 3.74]). However, opponents attribute a similarly high level of honesty to supporters (ŷOpponents = 3.4; CI = [3.30, 3.53]), and this difference is not significantly different from zero. Finally, supporters assign slightly lower levels of honesty to opponents (ŷSupporters = 2.9; CI = [2.70, 3.11]) compared to the ratings opponents assign to their fellow opponents (ŷOpponent = 3.3; CI = [3.12, 3.42]). This difference is significant at the 95% confidence level.

Comparing these results with the data on attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination in early 2022, it is evident that supporters of COVID-19 vaccination consider other supporters to be open to compromise and capable of critical thinking (positive traits), and perceive them as less narrowminded and selfish, while they view opponents to be narrowminded and selfish while not capable of critical thinking nor open to compromise (see supplementary material Figs. 6 and 7, Tables 16, 17). The opposite pattern is visible for opponents of vaccination, albeit less consistently. Overall, these findings indicate a somewhat asymmetric affective polarization between supporters and opponents, with a generally higher level of polarization in early 2022 compared to late 2023.Footnote 5

Overall, the two groups rate the pro- and anti-vaccination groups relatively similarly. However, what becomes evident is that supporters of vaccinations are more likely to attribute positive traits to their ingroup and negative traits to their outgroup. This observation is also indicative of asymmetrical affective polarization among vaccination advocates. In this regard, these findings extend previous research that illustrates asymmetric dislike between the two groups by revealing that affective polarization manifests as in-group/out-group stereotyping, rather than merely expressing dislike.

Furthermore, in 2023 the differences in assigned character traits are relatively small, supporting our expectation that vaccination has lost some of its conflict potential compared to the heydays of the pandemic. This is evident when comparing the 2023 data with the early 2022 data. Using our alternative group specification, the analyses presented in the supplementary material replicate these findings (Fig. 6, Tables 14, 15).

Affective polarization: social distance between supporters and opponents of vaccinations

The final indicator for assessing affective polarization measures the perceived social distance between the two groups. To do so, we follow the research on partisan affective polarization (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Klar et al. 2018) and ask respondents whether they would be unhappy if their child married a) a vaccination supporter and b) a vaccination opponent. Responses range from 1 (“very happy”) to 5 (“very unhappy”).

Figure 7 shows the predicted happiness if one’s child were to marry a pro-vaccine (blue) or an anti-vaccine (magenta) individual. Supporters appear somewhat happy if their child marries a vaccine supporter (ŷSupporters = 2.5; CI = [2.46, 2.59]), while opponents seem to be less happy but relatively indifferent about their child marrying a vaccine supporter (ŷOpponents = 2.8; CI = [2.68, 2.90]). The difference is significant at the 95% confidence level. Regarding the scenario of children marrying a vaccination opponent, supporters express only slight unhappiness if their child marries a vaccine opponent (ŷSupporters = 3.3; CI = [3.23, 3.43]) and opponents are also only slightly unhappy about their child marrying a vaccine opponent (ŷOpponents = 3.1; CI = [3.02, 3.22]). Albeit small, this difference is significant at the 95% confidence level.

This figure shows the predicted unhappiness with a child marrying a vaccination supporter (blue) and a vaccination opponent (magenta) when using a linear regression model with group status (supporters vs. opponents) as the main predictor controlling for age, sex, education, opinion-identity, left-right self-placement, income, and language using standard errors clustered at the cantonal level. Full models presented in supplementary material table 18; scale ranges from 1 “very happy” to 5 “very unhappy”; The difference is statistically significant on a 95% level.

Overall, opinions on vaccination do not appear to be a significant source of social distance. While there are small and significant differences in happiness among pro-vaccine individuals depending on whether their child would marry a pro-vaccine or anti-vaccine individual, these differences are relatively small. The same is true for anti-vaccination individuals, who seem to be largely indifferent regarding whether their child marries a member of either group. These findings are also replicated for the fourfold vaccination groups (see supplemental material Table 18 and Fig. 8).

Discussion

Vaccination against COVID-19 has created a rift in many societies. However, it remains unclear whether this deep conflict transitions into the post-pandemic era. Confronted with two conflicting expectations, we shed light on the social conflict surrounding attitudes toward vaccination in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. On one hand, the severity and intensity of the conflict suggest that we might observe opinion-based affective polarization even after the pandemic. On the other hand, recent research in social psychology and political science has primarily focused on opinion-based polarization in the context of highly salient and politicized issues (Balcells et al. 2023; Hobolt et al. 2021; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Simon et al. 2019), leading to the expectation that positions toward vaccination in the post-pandemic period will not form the basis of affective polarization, as they have lost in salience and are currently less politicized.

Using novel surveys from Switzerland, we demonstrate that individuals exhibit polarization in their attitudes toward vaccination against infectious diseases, with opinions ranging from strong support to strong opposition. Nevertheless, these opinions do not seem to be captured by wider political conflicts such as partisanship or ideology. Furthermore, when it comes to identification with opinion-based groups, vaccination displays only a limited capacity to form opinion-based identities, which are relatively modest. Only (strong) supporters of vaccination seem to develop an opinion-based identity, while opponents do not.

Finally, our evaluation of opinion-based affective polarization revealed an asymmetric affective polarization driven by pro-vaccination individuals. This pattern, previously observed during the pandemic, appears to persist even after the COVID-19 pandemic has ended. However, the level of polarization appears to be lower than what other studies reported during the COVID-19 pandemic (Henkel et al. 2022; Schieferdecker et al. 2024; Wagner and Eberl, 2024). This is particularly evident when comparing our 2023 results with data from early 2022, which shows higher levels of affective polarization regarding COVID-19 vaccinations. The salience and politicization of the vaccination issue seem to be crucial for the formation of opinion-based identities as well as for affective polarization between groups (see Hernández et al. 2021; Simon et al. 2019).

With this article, we contribute to our understanding of social conflict around vaccinations and extend the nascent research on opinion-based affective polarization. Using a variety of measures, we thoroughly evaluate the potential processes of opinion-based polarization, identity-formation, and affective polarization in a post-pandemic period, where it remains unclear whether the conflicts from the COVID-19 pandemic have persisted and whether vaccination continues to be an issue that fosters opinion-based group formation and subsequent affective polarization, even in times when it is not a politicized and salient issue. In contrast to the conflict-laden period of the pandemic, vaccination appears to have diminished in importance for identity-formation and polarization. Reflecting on the social situation during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights that the issue of vaccination can challenge societal cohesion at any time. Our findings from 2022 are a clear warning sign in this regard (see also Filsinger and Freitag, 2024).

In this vein, future research would do well to explore the issue further in three important domains. First, our data are cross-sectional and could benefit from causal identification through the use of survey experiments such as conjoint designs (Hobolt et al. 2021) or vignette experiments (Schieferdecker et al. 2024). Additionally, panel data could be employed to track individuals over time and across different contexts, leveraging variation in various environmental or political factors (Druckman et al. 2021a, 2021b; West and Iyengar, 2022). Unfortunately, our data comes from two different surveys with different samples provided by different companies. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of unaccounted differences in the characteristics of the participants that are not captured by the four-variable quota sampling and thus potentially bias the comparison between the two samples (Eyal et al. 2022). Consequently, it has to be noted that our results are only suggestive. In this regard, this paper represents only a first step that still requires substantial further research. However, we believe that our comparisons are valuable, as our samples follow the same quotas and are quite similar, for example, in terms of political ideology.

Furthermore, our focus is limited to Switzerland, and it is unclear how to approach our findings comparatively. However, as noted by the late Stein Rokkan (1970), Switzerland can be seen as a microcosm of Europe due to its cultural, linguistic, religious, and regional diversity. Additionally, Switzerland has been described as consisting of three groups that “stand with their backs to each other” while remaining open to influences from all sides (Steiner, 2001, p. 145). In other words, conclusions drawn from empirical analyses in Switzerland may be transferred to other countries or cultural contexts in Europe.

Second, our study looks at vaccination from a general perspective. While this approach mitigates biases stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, different forms of vaccination may evoke varying levels of opposition, necessitating more nuanced questions in future research. These may also inform policymakers about what conflicts to expect in future public health emergencies involving vaccination strategies. In addition, it should be noted that we are looking at opinions about vaccination rather than vaccination status, so future research could include both to examine their relationship. Third, future studies could take a closer look at the potential consequences of opinion-based (vaccination) affective polarization for politics and society. Affective biases may undermine public health responses and vaccination campaigns and, more generally, challenge political support and trust in institutions. The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged political institutions and social cohesion (Aassve et al. 2024; Bor et al. 2022; Erhardt et al. 2023; Filsinger et al. 2021; Schieferdecker et al. 2024), making a thorough knowledge of vaccine-related social conflict all the more pertinent in times when pandemics are boosted by increasing globalization and connectivity (Taylor, 2019).

Data availability

Materials and data are available via the OSF under the https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/98W7P.

Code availability

The data analysis script (including reported and supplemental analyses) is available via the OSF under the https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/98W7P.

Notes

In June 2024, Switzerland voted on a bill called «Für Freiheit und körperliche Unversehrtheit» (For freedom and physical integrity), which was launched by vaccination opponents in 2021.

Using alternative specifications for age (grouped age groups) or political ideology (squared term or grouped) does not alter our conclusions. Results are available upon request.

While partisanship is measured by party identification in 2023, it is measured by party vote intention in 2022 due to data limitations. It should be noted, however, that although the two concepts are analytically distinct, it is likely that they are highly correlated.

This line of reasoning is supported by additional analyses, not shown here but available upon request, showing that anti-vaccination groups seem to harbor more resentment toward the political realm than toward their outgroup.

Although we have data on character traits in both samples, the adjectives differ, which makes a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test not useful as potential differences may stem from question-wording rather than real differences in the distributions.

References

Aassve A, Capezzone T, Cavalli N, Conzo P, Peng C (2024) Social and political trust diverge during a crisis. Sci Rep 14(1):331. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50898-4

Balcells L, Daniels L‑A, Kuo A (2023) Territorial disputes and affective polarization. Eur J Political Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12640

Ballone C, Pacilli MG, Teresi M, Palumbo R, Pagliaro S (2023) Attitudes moralization and outgroup dehumanization in the dynamic between pro‐ vs. anti‐vaccines against COVID‐19. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 33(5):1297–1308. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2718

Bliuc A‑M, McGarty C, Reynolds K, Muntele D (2007) Opinion-based group membership as a predictor of commitment to political action. Eur J Soc Psychol 37(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.334

Bor A, Jørgensen F, Petersen MB (2022) Discriminatory attitudes against the unvaccinated during a global pandemic. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05607-y

Dias N, Lelkes Y (2022) The nature of affective polarization: disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. Am J Political Sci 66(3):775–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12628

Druckman JN, Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Levendusky M, Ryan JB (2021a) Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat Hum Behav 5(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Druckman JN, Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Levendusky M, Ryan JB (2021b) How affective polarization shapes Americans’ political beliefs: a study of response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Exp Political Sci 8(3):223–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.28

Druckman JN, Levendusky MS (2019) What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin Q 83(1):114–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003

Erhardt J, Freitag M, Filsinger M (2023) Leaving democracy? Pandemic threat, emotional accounts and regime support in comparative perspective. West Eur Politics 46(3):477–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2097409

Eyal P, Rothschild D, Gordon A, Evernden Z, Damer E (2022) Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behav Res Methods 54(4):1643–1662. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

Filsinger M, Freitag M (2024) Asymmetric affective polarization regarding COVID-19 vaccination in six European countries. Sci Rep 14(1):15919. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66756-w

Filsinger M, Freitag M, Erhardt J, Wamsler S (2021) Rally around your fellows: information and social trust in a real-world experiment during the corona crisis. Soc Sci J. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2021.1954463

Fiorina MP, Abrams SJ (2009) Disconnect: the breakdown of representation in American politics. University of Oklahoma Press

Gadarian SK, Goodman SW, Pepinsky TB (2021) Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 16(4):e0249596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249596

Henkel L, Sprengholz P, Korn L, Betsch C, Böhm R (2022) The association between vaccination status identification and societal polarization. Nat Hum Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01469-6

Hernández E, Anduiza E, Rico G (2021) Affective polarization and the salience of elections. Elect Stud 69:102203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102203

Hobolt SB, Leeper TJ, Tilley J (2021) Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit Referendum. Br J Political Sci 51(4):1476–1493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000125

Huddy L, Mason L, Aarøe L (2015) Expressive Partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and Partisan identity. Am Political Sci Rev 109(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

Iyengar S, Lelkes Y, Levendusky M, Malhotra N, Westwood SJ (2019) The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu Rev Political Sci 22(1):129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar S, Sood G, Lelkes Y (2012) Affect, not ideology. Public Opin Q 76(3):405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

Iyengar S, Westwood SJ (2015) Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am J Political Sci 59(3):690–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152

Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Ryan JB (2018) Affective polarization or partisan disdain? Untangling a dislike for the opposing party from a dislike of partisanship. Public Opin Q 82(2):379–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy014

Mason L (2018) Ideologues without Issues: the polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opin Q 82(S1):866–887. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy005

McGarty C, Bliuc A‑M, Thomas EF, Bongiorno R (2009) Collective action as the material expression of opinion-based group membership. J Soc Issues 65(4):839–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01627.x

Miller JD, Ackerman MS, Laspra B, Polino C, Huffaker JS (2022) Public attitude toward Covid-19 vaccination: the influence of education, partisanship, biological literacy, and coronavirus understanding. FASEB J 36(7):e22382. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202200730

Orr LV, Huber GA (2020) The policy basis of measured partisan animosity in the United States. Am J Political Sci 64(3):569–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12498

Rogowski JC, Sutherland JL (2016) How ideology fuels affective polarization. Political Behav 38(2):485–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7

Rokkan S (1970) Foreword. In: Steiner J (ed) Gewaltlose Politik und kulturelle Vielfalt. Hypothesen entwickelt am Beispiel Schweiz. Haupt, pp. 1–11

Ruggeri K, Stock F, Haslam SA, Capraro V, Boggio P, Ellemers N, Cichocka A, Douglas KM, Rand DG, van der Linden S, Cikara M, Finkel EJ, Druckman JN, Wohl MJA, Petty RE, Tucker JA, Shariff A, Gelfand M, Packer D, Willer R (2024) A synthesis of evidence for policy from behavioural science during COVID-19. Nature 625(7993):134–147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06840-9

Schieferdecker D, Joly P, Faas T (2024) Affective polarization between opinion-based groups in a context of Low Partisan Discord: measuring its prevalence and consequences. Int J Public Opin Res 36(2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edae009

Schuessler J, Dinesen PT, Østergaard SD, Sønderskov KM (2022) Public support for unequal treatment of unvaccinated citizens: evidence from Denmark. Soc Sci Med (1982) 305:115101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115101

Simon B, Reininger KM, Schaefer CD, Zitzmann S, Krys S (2019) Politicization as an antecedent of polarization: Evidence from two different political and national contexts. Br J Soc Psychol 58(4):769–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12307

Sprengholz P, Henkel L, Böhm R, Betsch C (2023) Historical narratives about the COVID-19 pandemic are motivationally biased. Nature 623(7987):588–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06674-5

Steiner J (2001) Switzerland and the European Union. A puzzle. In: Keating M, McGarry J (eds) Minority Nationalism and the changing international order. Oxford University Press, pp. 137–154

Stoetzer LF, Munzert S, Lowe W, Çalı B, Gohdes AR, Helbling M, Maxwell R, Traunmüller R (2022) Affective partisan polarization and moral dilemmas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Political Sci Res Methods 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.13

Tajfel H (1974) Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc Sci Inf (Int Soc Sci Counc) 13(2):65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

Tajfel H (ed) (1978) Differentiation between social groups. Academic Press

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1979) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG (eds) The Nelson-Hall series in psychology. Psychology of intergroup relations, 1st edn. Nelson-Hall, pp. 1–24

Taylor S (2019) The psychology of pandemics: preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. Cambridge Scholars Publisher

Wagner M (2024) Affective polarization in Europe. Eur Political Sci Rev 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000383

Wagner M, Eberl J‑M (2024) Divided by the jab: affective polarisation based on COVID vaccination status. J Elections Public Opinion Parties 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2024.2352449

West EA, Iyengar S (2022) Partisanship as a social identity: implications for polarization. Political Behav 44(2):807–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y

Zumbrunn A (2024) Country bumpkin or city slicker? The role of place of living and place-based identity in explaining place-based resentment. Political Res Q 77(2):592–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129241230541

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Multidisciplinary Center for Infectious Diseases at the University of Bern (No. MA_21) and the Berne University Research Foundation (No. 52/23_IMGS). Julian Erhardt and Mila Bühler are gratefully acknowledged for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MFi and MFr conceived the study and conducted the survey; MFi analyzed the results; MFi and MFr wrote the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Business Administration, Economics and Social Sciences of the University of Bern. For the survey data from 2023 approval was obtained on June 12, 2023, with the approval number 192023. Our analyses of the data were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations as well as in accordance with the ethical approval from the Ethics Committee and the Declaration of Helsinki. For the survey data from 2022 approval was obtained on July 21, 2020, with the approval number 092020. Our analyses of the data were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations as well as in accordance with the ethical approval from the Ethics Committee and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Before answering the 2022 survey, the survey company obtained written informed consent from the participants that included participation, data use and consent to publish. Additionally, participants had the choice to drop out if they did not provide consent or if, during the survey, they did not want to answer a question. The respondents received a small compensation for their participation from the survey company. Before answering the 2023 survey, the survey company obtained written informed consent from the participants that included participation, data use and consent to publish. Additionally, participants had the choice to drop out if they did not provide consent or if during the survey they did not want to answer a question. The respondents received a small compensation for their participation from the survey company.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Filsinger, M., Freitag, M. Divided by vaccination? Evaluating the intergroup conflict between pro- and anti-vaccination groups in the post-pandemic era. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04016-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04016-y