Abstract

Architectural heritage is recognized globally as an important resource for sustainable urban regeneration. The adaptive reuse of ‘buildings of control and reform’ (BCR) such as leprosariums has increasingly attracted academic discussion, and the conflict between the segregated nature of BCR and the significance of heritage in the context of urban development has become a key point of discussion. However, there is still a lack of research on how such buildings have been selected for new functions in order to achieve these aims. Therefore, this study attempted to establish a functional decision-making model for the adaptive reuse of BCR. The Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and Sensitivity Analysis were used to filter out the new functions with the highest priority, taking Macau- the Nossa Senhora Village as an example. This study constructed a decision-making framework consisting of 6 dimensions and 17 criteria. It also identified the key decision-making criteria under each dimension. This paper aims to provide insights into the theoretical research and practical development of adaptive reuse of architectural heritage by integrating sustainable urban development and heritage conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The role of architectural heritage as a driver of sustainable urban development has been discussed and recognized (Nations, 2015; Labadi et al., 2021; Lerario, 2022; Cucco et al., 2023). In particular, the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage can help achieve a number of urban goals, including the preservation of cultural values and environmental regeneration (Bullen and Love, 2011b; Conejos et al., 2011; Foster, Saleh, 2021); Gravagnuolo et al., 2024). However, inappropriate reuse functions often result in a disconnect between the old and new identities of heritage (Mısırlısoy and Günçe, 2016; Arfa et al., 2022). On the one hand, decision-makers may have different value priorities, resulting in a lack of attention to the authenticity of architectural heritage (Gao et al., 2020; Gibbeson, 2023). On the other hand, the new functions are may not in line with the contemporary cultural identity, social needs, and economic objectives of the city as a whole, making it difficult to promote sustainable urban development (Shen and Langston, 2010; Ribera et al., 2020).

These issues are particularly evident in the ‘buildings of control and reform’ (BCR). This was a type of building that emerged in the 18th century on the basis of European post-Enlightenment thinking, such as hospitals, prisons, asylums, and abattoirs (Markus and Mulholland, 1982; Foucault, 1984; Pendlebury et al., 2017). This type of building was initially conceived to exemplify the contemporary social hierarchy and, through spatial architecture, to exclude a segment of mainstream society labeled as ‘abnormal individuals’ from everyday social environments, aiming to manage and rehabilitate them, and also to avoid social pressure (Joseph et al., 2013; Wang, 2020). Consequently, these buildings exhibit varying levels of detachment from the urban environment concerning location, traffic, architectural style, configuration, and landscape (Kistner, 2014; Wyatt, 2025).

From a heritage conservation perspective, the introduction of new functions to such heritage must not distort or obscure its significance, and its interpretation and appreciation must be upheld (Australia Icomos, 2013), as the social, cultural, and historical value of this architectural heritage is acknowledged globally (Wang, 2020). Nevertheless, within the framework of sustainable development, these structures must be modified via adaptive reuse to align with the cultural character, social requirements, and economic goals of the city (Vardopoulos, 2019). These buildings must be converted from marginalized spaces, dismissed by mainstream society, into active spaces that reflect the image of mainstream society, engage in social services, and collaborate with the city’s industrial and economic development (Joseph et al., 2013; Saccaggi and Delport, 2015; Nabas, 2019). The reuse of these buildings is also more than just a transformation of physical space; it is a reinterpretation and reconstruction of the memories of the past, the needs of the present, and the possibilities of the future (Pendlebury et al., 2017). The transfer of identity is far more challenging for them than for the architectural history of production, housing, and commercial services that were once integral to mainstream society (Kearns et al., 2010; Karami, 2022).

The need for adaptive reuse means that most of such heritage requires not only a change in narrative but also adaptation to particular architectural forms. (Pendlebury et al., 2017; Wyatt, 2025). Pieris (2018) believes that it is a complex challenge to find new social functions for such heritage while respecting history. Yet much of the existing research has focused on the processes and strategies used to achieve new functional changes in these buildings, with fewer studies focusing on how to decide on new functions that fit the BCR, especially since most of them lack appropriate uses (Kearns et al., 2010; Shehata et al., 2023). Moreover, functional decision-making in adaptive reuse is inherently a complex process (Mısırlısoy and Günçe, 2016; Li et al., 2021). Of these, multiple and conflicting factors are involved, which may include various stakeholders and different dimensions (Bullen and Love, 2011a; Haroun et al., 2019; Aigwi, et al., 2021; Pintossi et al., 2023; Mısırlısoy and Günçe, 2016; Lanz and Pendlebury, 2022; van Laar et al., 2024), such problems are regarded as multi-criteria decision problems (Chen et al., 2018).

Macau is a high-density city with world heritage, and the tension between heritage conservation and urbanization is gradually being magnified (Yen, 2013; Chu, 2015; Pereira and Caballero, 2016; Fung et al., 2017). The Nossa Senhora Village is the site of the last leprosarium in Macau which was established in early 1885 and abandoned in 1990 (Cheng and Chan, 2013). As a cultural heritage designated by the Government, the buildings are required to participate in the development of cultural tourism actively, the promotion of Macau’s unique Chinese and Western cultural characteristics, and the provision of social services, thereby contributing to the sustainable development of Macau (Tourism Development Committee of Macau SAR, 2016; Cultural Affairs Bureau, 2021b).

Accordingly, taking Macau- the Nossa Senhora Village as an example, this research attempts to develop a decision-making model for the adaptive reuse of BCR, which has to negotiate the conflict between the segregating nature of the building’s past and the heritage nature of its present that serves for urban identity and sustainable development.

Adaptive reuse of BCR

Unlike other buildings, BCR is a unique set of architectural forms created in response to functional needs (Kucik, 2004; Pendlebury et al., 2017; Gibbeson, 2023), which can pose additional challenges in terms of the selection of new functions. Firstly, the sites of such buildings are often located on the urban fringe or even surrounded by green space (Kearns et al., 2010; Karami, 2022), with inadequate peripheral facilities. Then their spatial layout is mostly closed, restricted and static, and they have been removed from mechanisms of control and restraint for some time (Joseph et al., 2013). Critically, such buildings are subject to their complex and contested histories and can easily develop a stigmatized or negative image. Contrary to the dominant narratives that authorize heritage discourse (Smith, 2006), this has led to them being seen as having secondary historical significance in the context of nation-building, making it difficult for them to be prioritized for historic preservation, and therefore presenting themselves as disjointed from the functioning of society at both the material and memory levels (Wang, 2020; Karami, 2022).

Nowadays, there are several practices and studies on the adaptive reuse of such buildings, such as transforming former slaughterhouses into high-end commercial spaces, former mental hospitals into ‘mansions’, and former prisons into high-class hotels (Pendlebury et al., 2017; Shehata et al., 2023). This often involves a particular adaptive reuse approach: strategic forgetting and selective memory, a process that seeks to remove uncomfortable parts of a place’s past and avoid or minimize references to previous uses (Joseph et al., 2013). Typically, this involves deliberately emphasizing the building’s values, and creating a new marketing narrative for the place, thereby enhancing public acceptance and experience (Joseph et al., 2013; Gibbeson, 2023). By distancing the present image from the past through means such as heritage assessment or the development of creative industries, a value identity is created (Ye, 2024). But at the same time, there was some criticism, with Carlton (2024) arguing that the injection of new functions, such as the pub in Pentridge Prison led to a profound sense of incongruity.

Criteria for adaptive reuse of BCR

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on exploring the physical characteristics, stakeholder aspirations, environmental sustainability, and cultural significance associated with the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage (Bottero, et al., 2019; Haroun et al., 2019; Dell’Ovo et al., 2021; Sharifi and Farahinia, 2023; Maselli et al., 2024; van Laar et al., 2024).

This paragraph first focuses on the common criteria used at the stage of deciding on the new function of the heritage. For instance, Chen et al. (2018) established a functional decision-making framework for adaptive reuse, which aims to integrate architectural, environmental, economic, historical, and social factors. Ribera et al. (2020) highlight the importance of economic, social, and cultural criteria because they are sufficiently comprehensive to assess the economic benefits of the reuse of a historic building and take into account the social and cultural impacts it may have on the community. Cucco et al. (2023) also identified criteria of public interest, sustainability, compatibility and proportionality in terms of the three dimensions mentioned above, in line with the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and the European Quality Principles. Meanwhile, Labadi et al. (2021) provide an analysis of how heritage can help achieve the SDGs, such as how it can connect different actors and thus promote well-being for all at all ages. In particular, the criteria under the economic, environmental, and social dimensions, as economic sustainability can alleviate the pressure of subsequent maintenance, while the new functions should meet the social needs and enhance the sense of belonging of the local community (Aydın et al., 2015; Mısırlısoy and Günçe, 2016).

It is critical to extract the special criteria that fit the BCR. Gravagnuolo et al. (2024) developed a functional decision-making framework for several abandoned convents (three of which had been used as prisons), whose criteria are still highly informative, such as (1) Social inclusion, (2) Accessibility of the urban area, especially (3) Level of integration of neighborhood activities and proximity shops in the area, as the basis for the successful operation of the new functions also needs to be considered (Yung and Chan, 2012). Success factors for adaptive reuse of such heritage also need to be extracted to improve the applicability of the model. Pendlebury et al. (2017) and Pieris (2018) recognize that the esthetic characteristics of a building can help unlock potential economic value by alleviating the heaviness associated with past functions. This is also supported by Wyatt (2025). Joseph et al. (2013) suggest that policy frameworks and community support are two key success factors. This is due to the need to consider stakeholder acceptance of the combination of such heritage and new functions (Choung and Choi, 2020; Gibbeson, 2023). In addition, the inclusion of new functions needs to enhance the openness of the heritage (Karami, 2022).

In summary, this study is based on the perspectives of architectural heritage conservation and sustainable urban development, it also proceeds to review the relevant literature, conservation documents, and practical projects, importantly incorporating the characteristics of BCR; this results in functional decision criteria for adaptive reuse that are appropriate for the type of heritage. Table 1 shows the 25 elements and definitions under the six dimensions.

Study design and methodology

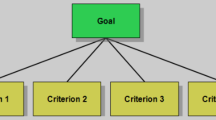

Multi-criteria decision-making methods (MCDMs) offer a methodical and organized framework for decision-making which assists decision-makers in identifying the most suitable or satisfactory solutions (Sahoo and Goswami, 2023). In this research, the selection and definition of key decision-making criteria were first determined using the FDM on the basis of preliminary criteria. Subsequently, the criteria weights are derived by combining AHP. Through sensitivity analysis, the stability of each functional priority is observed, and finally, the alternative with the highest priority is derived (Fig. 1).

Fuzzy Delphi method (FDM)

The FDM enhances the efficiency of interviews and minimizes the need for surveys. It enables experts to articulate their thoughts with precision and comprehensiveness, improving the applicability of the criteria (Lee et al., 2010). Given that researchers may have differences in defining and interpreting adaptive reuse and BCR, to enhance the integration of the criteria with BCR while fitting the urban characteristics of Macau, this study utilizes FDM to identify key criteria. Following the study of Zhao et al. (2024), Zhu et al. (2022), and Zhu et al. (2025), FDM in this study used the ‘double triangular fuzzy number’ with ‘a gray zone verification method’ to determine whether expert cognition demonstrates a consistent convergence effect.

Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

Following the literature review, it is clear that the AHP method can both calculate the criteria weights and rank the alternatives, it is the most common research tool at this stage of adaptive reuse (Maselli et al., 2024; Cucco et al., 2023; Nadkarni and Puthuvayi, 2020). Also, it is often applied in studies involving resource allocation and determining optimal choices (Vaidya and Kumar, 2006). The research’s subsequent calculations used the same computational approach as Saaty’s (1980) hierarchical analysis study to arrive at the highest-priority alternative. Once the consistency check was completed, group decision-making took place.

Sensitivity analysis

Scholars believe that the results of decision-making are easily influenced by multiple factors from the social environment, thereby affecting the applicability of the decision outcomes (Chen et al., 2018). Therefore, sensitivity analysis is used to observe the impact of different criteria weights from various aspects on the priority ranking of alternative categories. This helps to test the stability and consistency of the model results and to document trends and intervals of change in the values. By understanding the criteria that have the greatest potential impact on the model, it is possible to assess the risk resilience of the highest priority function and provide a reference for future planning directions. The process of applying the methodology is informed by the studies of Mukhametzyanov and Pamučar (2018).

Illustrative example

Study area

In this study, Macau- the Nossa Senhora Village is chosen as an example of this stage. The former Director of the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macau believes that, at the spatial level, heritage should be allowed to become an organic component of the urban landscape, constituting a unique cityscape, creating a distinctive urban personality and a relaxing urban atmosphere, and that the sustainable development of the city should be achieved through the preservation and reuse of architectural heritage (Ung, 2015). However, leprosariums are often considered to be of low architectural value, marginalized in urban development, and recognized as a ‘difficult heritage’ (Wang, 2020). The Nossa Senhora Village has developed into a small, relatively complete community space due to its previous function, which is located in the eastern part of Coloane, Macau in Figs. 2 and 3 (Archives of Macau, 2021). The spatial characteristics of the Nossa Senhora Village may have been shaped by a combination of former segregation requirements, topography, and physical conditions of the patients. The heritage is in the form of a cluster of one-storey monolithic buildings built on a hill, the main buildings of which include five rectangular buildings and a recreation room (former church), as well as the Our Lady of Sorrows Church, representing the eclectic architectural style that is characteristic of Macau’s historical buildings (Lai, 2020; Chan and Long, 2021). The total area of the buildings is approximately 1135 square meters, with the church occupying 504 square meters and each house measuring around 70 square meters. The available area within the buffer zone is approximately 7541 square meters.

Sources: Cheng and Chan (2013).

However, following the closure of the leprosarium, the building ensemble suffered varying degrees of material and structural damage (Cheng and Chan, 2013). With the increasing attention of the Government and the community, the restoration and renovation of the Nossa Senhora Village was completed in 2021, but these buildings are not being utilized to their full potential (Ye, 2024). The condition of the village was comprehensively analyzed through a combination of photographs, interviews, and documents from the Archives of Macau (2021). Then, based on the relevant value assessment documents, the characteristics of the Village, such as scale, location, value, state of repair, surrounding industries, comfort level, etc., were summarized and analyzed. This allowed us to evaluate the village’s condition during that period objectively. The Nossa Senhora Village was determined to possess significant historical and cultural significance. The building ensemble is relatively small in size and the population density is low, transportation is inconvenient, and there is a lack of basic infrastructure. The predominant industries in the area are industrial and medical. However, the natural landscape is well-preserved. Therefore, based on the historical context of the property and other considerations, it is suitable as an empirical case for this study.

Selection of key evaluation criteria

To better integrate the urban characteristics of Macau, the aforementioned FDM was used to interview seven professionals who learn and work in Macau, including architects, restorer, urban planners, spatial designers, and university lecturers. The experts in this study have extensive experience in their respective professional disciplines. In addition, most of them are involved in government-led or approved research or program practices. Table 2 shows the list of experts’ information involved in this research.

Therefore, their explicit or implicit knowledge of this topic contributes greatly to this research. In addition, as the focus of the study is on BCR, it was hoped that the experts had given due consideration to the internal and external factors that affect the decision-making on the functioning of such estates. Simultaneously, the researcher maintained communication with the experts throughout the interview phase, to minimize any possible misunderstandings or personal biases. In the end, a total of 17 key criteria were selected for inclusion in the decision model (Fig. 4 and Table 3), Six of these criteria were relevant to the BCR and urban sustainability perspectives, namely C1 (Esthetics and original architecture), C5 (Enable a connected and open-space network), C6 (Benefit community facilities), C7 (Commercial activities and sports facilities), C13 (Regional identity) and C15 (Urban master plan).

Function alternatives

There are three more common ways of selecting alternative functions, the first being derived from Ribera et al. (2020) based on the needs of the residents and the market. The second method, proposed by Chen et al. (2018), involves analyzing and summarizing successful cases of adaptive reuse in the same city facing a similar situation to the study area. And the third approach is to make functional recommendations through local expert panels as mentioned by Della Spina (2021).

Yasemin Çakır and Edis. (2022) suggests that successful adaptive reuse cases for similar functions tend to exhibit similar characteristics and interventions. Therefore, based on the above literature, the first step was to understand the needs of local citizens and markets through experts. Successful adaptive reuse cases of Macau’s architectural heritage with similar factors (e.g., local area, massing, and history) to that of the Nossa Senhora Village were also examined. This selection aimed to minimize the disconnect between function and urban planning and development, and also effectively helped to explore the potential of the Nossa Senhora Village to accommodate new functions.

Successful cases in Macau comprise the Coloane Library, the Exhibition Room of Master Lu Ban’s Woodcraft Works, Night Watch House (Patane), Tung Sin Tong Historical Archive Exhibition Hall, Building at No. 2, Company of Jesus Square, the location of Former Opium House, No. 10 Madhouse, and Chun Chou Tong Pavilion (Table 4). All of the successful cases were communal buildings since the variations in ownership of the heritage would have led to significantly varied purposes (Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macau, 2023). After consulting relevant literature and experts’ recommendations, the researchers analyzed and categorized the old and new functions of the study area. Based on this analysis, four categories of alternative functions were identified: A1 for community activities, A2 for exhibition and education, A3 for organizational office, and A4 for commercial use. Simultaneously, based on the above three ways of selecting the alternative options, given that the original function of the Nossa Senhora Village did not fall within these four categories, experts have determined that the retention and continuation of medically relevant functions still somewhat justified, thus the A5 (function categories of medical services) is added (Table 5).

Criteria weighting

Combining the selected 17 criteria, the weighting of the reuse decision criteria was carried out by five experts. As mentioned earlier, all five experts were very familiar with the BCR and the relevant context of the Nossa Senhora Village. This step used a questionnaire to help the experts assign weights to the importance of each criterion and the adaptability of alternative solutions to each criterion in the Nossa Senhora Village. After allocating weights based on each expert’s familiarity with the Nossa Senhora Village, the questionnaire responses were computed using the above-mentioned method to obtain the weight of criteria (Table 6).

Priority ranking of alternatives

After the AHP cluster decision-making was completed, the final alternative function priority ranking was derived based on the weights of all the dimensions (Table 7), where the result also contained the ranking under each dimension separately (Table 8). However, except for the economic aspect where A4 (commercial use) was given priority, the other five dimensions all prioritized A2 (exhibition and education). Applying the arithmetic mean to the calculation of the final decision results, the highest priority functional category for the adaptive reuse of the Nossa Senhora Village was determined to be A2 (exhibition and education), followed by A1 (community activities), A4 (commercial use), A3 (organizational office), and A5 (medical services). Exhibition and education, as the best function for the adaptive reuse of the Nossa Senhora Village, aligned with the government’s revitalization plan. Combining the fact that community activities ranked second in multiple aspects and final rankings, it can be considered as a supplementary function for specific periods of time, this can also function as a point of reference for the Government’s subsequent planning.

Sensitivity analysis

Using the sensitivity analysis method, it was possible to clearly see the impact of the changes in the weights of the various structures on the priority ranking of the reuse functions of the Nossa Senhora Village, so as to judge the stability and unity of the functions (Fig. 5).

According to the data in S1, weight increase in physical orientation did not affect the ranking of various functional categories, although A2 and A5 were still significantly impacted. As shown in S2, the significance of A2 was directly proportional to the environmental orientation, while the priority of A3 decreased with an increase in environmental orientation.

S3 illustrated that an increase in economic orientation significantly affects the change in alternative functions. A1 and A4 intersected when the economic orientation weight was approximately 0.24, and A2 and A4 overlapped when the weight reached 0.64. As economic orientation weight increased, the priority of A4 increased, while that of A1 and A2 decreased.

S4 showed a negative correlation between social orientation weight and the priority of A2 and A4. According to S4, it was indicated that social orientation greatly impacts the ranking of A1 and A4.

And S5 showed that A4 continued to drop to the bottom of the ranking as the weight of cultural orientation grew. In contrast, A2 remained the highest priority. Otherwise, there was no significant change for A1, A3 and A5.

As political orientation weight increased in S6, the priority of A2 and A3 gradually increased, while that of A4 decreased. It can be seen that political orientation had the greatest influence on the priority order of A2, A3, and A4.

In conclusion, alterations in the weightings of economic orientation, cultural orientation, and social orientation significantly impacted the ranking of the alternatives. Out of the six dimensions, A2 had the highest priority, while A3 and A5 were given the lowest priority. According to these findings, the strategy of community activities in the vicinity of the Nossa Senhora Village was not as beneficial as the approach of boosting exhibition and education.

Discussion

These once purpose-built buildings are becoming outdated and superfluous., and the dark identities inherited from past functions present greater challenges to adaptive reuse (Pendlebury et al., 2017), with new functions requiring negotiation between the materiality and the narratives. This study thus proposes particular functional decision-making criteria for such architectural heritage. For example, C5 (Enable a connected and open-space network), C6 (Benefit community facilities), and C7 (Commercial activities and Sports facilities). As these buildings are sited far from the city center and are too spatially enclosed, new functions are needed to help connect the heritage to the urban space and to provide more community facilities in the surrounding area (Gravagnuolo et al., 2024), thus better serving the surrounding community and increasing public acceptance and use. This is especially the case for commercial activities and sports facilities, as most of the new adaptive reuse functions will need to rely on better infrastructure in the surrounding area in order to attract people’s attention (Ren et al., 2014).

At the same time, the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process bring their own professional perspectives to the reuse process, so they view the building with a specific focus. According to Table 6, the political, cultural, and physical dimensions of the criteria are relatively highly weighted. This may be due to the fact that respondents perceive the cost of reusing such buildings to be higher. Successful integration of otherwise detached spaces into overall urban development plans can only be achieved through policy support (Kearns et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2014). Culturally relevant, such buildings are at odds with the international heritage discourse, leading to the need to consider how to attach cultural attributes to them and incorporate them into the city’s cultural identity, and through the unification of cultural identities, to integrate previously excluded buildings into today’s urban landscapes (Loh, 2011). In addition, respondents considered that the original function mostly served niche groups, resulting in the use of space that emphasizes supervision and isolation and is relatively confined, but now that the service target has changed to the general public, the spatial form must be open and inclusive, with an emphasis on spatial flexibility and mobility, which is in line with the view of Shehata et al. (2023). It is worth noting that Carlton (2024) critically points out that new functions tend to promote a collective forgetting of the history of such buildings, but the higher weighting of the political and cultural dimensions in this study may place a greater emphasis on the preservation and interpretation of the BCR’s heritage values. Nowadays it is common to use heritage spaces as an ideal cultural medium from which to present selected historical and renovated architectural objects and programs to the audience (Ye, 2024). The citizens of Macau have also suggested that buildings with Portuguese characteristics and historical value should be preserved and fully utilized in order to show the identity of a tourist city (Cultural Affairs Bureau, 2021a), which helps to explain why exhibition and education are the top of the list of alternative for the Nossa Senhora Village. Firstly, Exhibition and Education is in line with the direction of Macau’s cultural industry development (Ye, 2021), and through the transformation of functions, the architectural heritage can contribute well to the sustainable economic and cultural development of Macau. Secondly, Exhibition and Education has the role of cultural dissemination, and by transforming its function into cultural dissemination, the building assumes the role of displaying the city’s image, thus integrating itself into Macau’s urban identity. Finally, the spatial characteristics of the original building fit with the spatial needs of the current building: several independent individual spaces are suitable for the simultaneous use of several independent exhibition halls or classrooms (workshops, training).

Also, Wang and Zeng (2010) mention that conflicts may exist between cultural preservation and economic development when considering adaptive reuse. Based on the result of sensitive analysis, it can be observed that an increase in the cultural and social orientation weight of the Nossa Senhora Village would diminish the applicability of the commercial use, while the priority of the exhibition and education category and the community activities category remains in the top two positions, with the economic aspect being the opposite. According to existing discussions of ‘selective memory, strategic forgetting’ (Kearns et al., 2010; Pendlebury et al., 2017; Gibbeson, 2023), commercial often requires a certain degree of attenuation of their historical and social characteristics, minimizing references to their original purpose. This is similar to the situation in the Nossa Senhora Village. For BCRs like leprosariums, it may also be necessary to inject a new brand image and reduce authenticity in order to enhance the effectiveness of commercial schemes, which contradicts the heritage identity of the Nossa Senhora Village. This also explains why there is no significant increase in the priority ranking of organizational office and medical services in S3, which also bring economic benefits but have less conflict with the original function.

Conclusion

Architectural heritage are valuable resources for sustainable development in urban renewal. While reducing environmental damage, their diverse values also serve as important elements of local identity and urban development. This research takes the BCR as an entry point to construct a functional decision-making model of adaptive reuse for its application.

Contribution

The contribution of this research is to provide an adaptive reuse decision-making model that incorporates an urban sustainability perspective and focuses on the functional decision-making criteria of what are recognized as BCR such as leprosariums, for heritage conservation and sustainable urban development.

van Laar et al. (2024) mentioned that differences in decision-making criteria across building types should be further explored in future studies. This research fills the above research gap, enriches the functional decision-making system for adaptive reuse of built heritage, and provides a new perspective for the field.

Critically, this study takes into account the differences in decision-making between this particular type of heritage and built heritage in general and expands on the existing literature to include a number of criteria related to urban spatial development, incorporating local urban characteristics, thereby increasing the facilitating role of this type of heritage in the realization of sustainable development goals.

Limitations

The use of this model assumes that the architectural heritage has been identified as being in need of adaptive reuse. Since this study emphasizes the integration of decision models with urban characteristics, the results are difficult to extrapolate, resulting in the need to re-screen the decision-making criteria and alternative functions for different urban objects.

Future studies

This study also hopes to lay the foundation for future research on adaptive reuse strategies, which could involve: (1) expanding the consideration of multiple building types in adaptive reuse decisions; (2) encouraging the participation of experts from different fields to improve the strategic perspective and influential factors; (3) strengthening the coherence of each step in adaptive reuse decisions, such as value assessment and preservation direction.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

10 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04845-5

References

Aigwi IE, Phipps R, Ingham J, Filippova O (2021) Characterisation of adaptive reuse stakeholders and the effectiveness of collaborative rationality towards building resilient urban areas. Syst Pract Action Res 34:141–151

Archives of Macau (2021) LAND of HOPE (Historic Archives Exhibition on Leprosariums in Macau) Cultural Affairs Bureau of the Macau Special Administrative Region Government, Macau

Arfa FH, Zijlstra H, Lubelli B, Quist W (2022) Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: From a literature review to a model of practice. Hist Environ Policy Pract 13(2):148–170

Australia Icomos (2013) The Burra Charter. Deakin University. https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov 2024

Aydın D, Yaldız E, Sıramkaya SB (2015) Evaluation of Domestic Architecture via the Context of Sustainability: Cases from Konya City Center. Archnet-IJAR: Inte J Archit Res 9(1):305–317

Bottero M, D’Alpaos C, Oppio A (2019) Ranking of adaptive reuse strategies for abandoned industrial heritage in vulnerable contexts: a multiple criteria decision aiding approach. Sustainability 11(No. 3):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030785

Bullen P, Love P (2011a) A new future for the past: a model for adaptive reuse decision-making. Built Environ Proj Asset Manag 1(No. 1):32–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/20441241111143768

Bullen PA, Love PED (2011b) Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct Surv 29(No. 5):411–421. https://doi.org/10.1108/02630801111182439

Carlton B (2024) Heritage, resistance and dissonance: reconstructing Pentridge in a prison tourism theme park. Int J Herit Stud 30(11):1304–1323

Chan C-S, Long D (2021) Memorandum of Macau historic buildings. The Heritage Society, Macau

Chen C-S, Chiu Y-H, Tsai L (2018) Evaluating the adaptive reuse of historic buildings through multicriteria decision-making. Habitat Int 81:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.09.003

Cheng PWM, Chan TH (2013) Nossa Senhora Village in Ka Ho: The Last Leprosarium in Macau. Macau Polytechnic University, Macau

Choung EH, Choi SH (2020) Sorokdo as a combined dark tourism site of leprosy and colonized past. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25(8):814–828

Chu CL (2015) Spectacular Macau: visioning futures for a world heritage city. Geoforum 65:440–450

Conejos S, Langston CA, Smith J (2011) Improving the implementation of adaptive reuse strategies for historic buildings, International Forum of Studies Titled SAVE Heritage: Safeguard of Architectural, Visual, Environmental Heritage, pp. 1–10. Institute of Sustainable Development and Architecture

Cucco P, Maselli G, Nesticò A, Ribera F (2023) An evaluation model for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage in accordance with 2030 SDGs and European Quality Principles. J Cult Herit 59:202–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2022.12.002

Cultural Affairs Bureau (2021a) The 3rd batch of the proposed immovable property classification of Macau—Summary Report of Public Consultation

Cultural Affairs Bureau (2021b) Reply to Legislative Council Member Wu Guochang’s Written Consultation. available at: https://www.al.gov.mo/uploads/attachment/2021-02/589776038a5eac9a86.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov 2024

Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macau (2023) Macau Cultural Heritage. available at: https://www.culturalheritage.mo/en/list/9. Accessed 2 Jul 2024

Della Spina L (2021) Cultural heritage: a hybrid framework for ranking adaptive reuse strategies. Buildings 11(3):132

Dell’Ovo M, Dell’Anna F, Simonelli R, Sdino L (2021) Enhancing the cultural heritage through adaptive reuse. A multicriteria approach to evaluate the Castello Visconteo in Cusago (Italy). Sustainability 13(8):4440

Foster G, Saleh R (2021) The adaptive reuse of cultural heritage in European circular city plans: a systematic review. Sustainability 13(No. 5):2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052889

Foucault M (1984) Of other spaces: Utopias and hetertopias. Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, translated by J. Miskowiec. Retrieved 24 December 2022, from Website: https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf

Fung IWH, Tsang YT, Tam VWY, Xu YT, Mok ECK (2017) A review on historic building conservation: a comparison between Hong Kong and Macau systems. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 71:927–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.121. pp

Gao J, Lin SS, Zhang C (2020) Authenticity, involvement, and nostalgia: understanding visitor satisfaction with an adaptive reuse heritage site in urban China. J Destin Mark Manag 15:100404

Gibbeson C (2023) After the asylum: value, stigma, and strategic forgetting in three historic former asylums. Int J Herit Stud 29(6):566–580

Gravagnuolo A, Angrisano M, Bosone M, Buglione F, De Toro P, Girard LF (2024) Participatory evaluation of cultural heritage adaptive reuse interventions in the circular economy perspective: a case study of historic buildings in Salerno (Italy). J Urban Manag 13(1):107–139

Haroun H-AAF, Bakr AF, Hasan AE-S (2019) Multi-criteria decision making for adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: Aziza Fahmy Palace, Alexandria, Egypt. Alex Eng J 58(No. 2):467–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2019.04.003

Joseph A, Kearns R, Moon G (2013) Re-imagining psychiatric asylum spaces through residential redevelopment: Strategic forgetting and selective remembrance. Hous Stud 28(1):135–153

Karami S (2022) No longer a prison: the logistics and politics of transforming a prison as work of architecture. Space Cult 25(3):415–433

Kearns R, Joseph AE, Moon G (2010) Memorialisation and remembrance: on strategic forgetting and the metamorphosis of psychiatric asylums into sites for tertiary educational provision. Soc Cult Geogr 11(8):731–749

Kistner U (2014) Heterotopographies of a Restless Heritage: The West and the Rest of Pretoria, South Africa. Soc Sci 42(5/6):81–101

Kucik LM (2004) Restoring life: the adaptive reuse of a sanatorium. Master’s thesis, University of Cincinnati

Labadi S, Giliberto F, Rosetti I, Shetabi L, Yildirim E (2021) Heritage and the sustainable development goals: Policy guidance for heritage and development actors. ICOMOS. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/89231/1/ICOMOS_SDGs_Policy_Guidance_2021.pdf

Lai M-C (2020) Farewell to stigma: from Leprosarium to Nossa Senhora Village in Ka Ho. Proceedings of the 2020 Haojiang New Language Doctoral Forum, Macau University of Science and Technology. The Past, Future and Present of Ka Ho Village. 29 Oct 2020

Lanz F, Pendlebury J (2022) Adaptive reuse: a critical review. J Archit 27(No. 2-3):441–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2022.2105381

Lee AH, Wang WM, Lin TY (2010) An evaluation framework for technology transfer of new equipment in high technology industry. Technol Forecast Soc Change 77(1):135–150

Lerario A (2022) The role of built heritage for sustainable development goals: from statement to action. Heritage 5(3):2444–2463

Li Y, Zhao L, Huang J, Law A (2021) Research frameworks, methodologies, and assessment methods concerning the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: a review. Built Herit 5:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43238-021-00025-x

Loh KS (2011) No more road to walk’: cultures of heritage and leprosariums in Singapore and Malaysia. Int J Herit Stud 17(3):230–244

Maselli G, Cucco P, Nestico A, Ribera F (2024) Historical heritage-multicriteria decision method (H-MCDM) to prioritize intervention strategies for the adaptive reuse of valuable architectural assetsz. MethodsX 12:102487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2023.102487

Markus TA, Mulholland H (1982) Order in Space and Society: architectural form and its context in the Scottish Enlightenment. Edinburgh: Mainstream

Mısırlısoy D, Günçe K (2016) Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: a holistic approach. Sustain Cities Soc 26,:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2016.05.017

Mukhametzyanov I, Pamučar D (2018) A sensitivity analysis in MCDM problems: a statistical approach. Decis Mak Appl Manag Eng 1(No. 2):51–80. https://doi.org/10.31181/dmame1802050m

Nabas B (2019) The role of uncomfortable heritage in sustainable development. Int J Herit Mus Stud 1(1):57–79

Nadkarni RR, Puthuvayi B (2020) A comprehensive literature review of multi-criteria decision making methods in heritage buildings. J Build Eng 32:101814

Nations U (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations, New York. Dep Econ Soc Aff 1:41

Pendlebury J, Wang Y-W, Law A (2017) Re-using ‘uncomfortable heritage’: the case of the 1933 building, Shanghai. Int J Herit Stud 24(No. 3):211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1362580

Pereira M, Caballero G (2016) Challenges of the Casino and Historic City of Macau: preserving heritage amidst the creation of stage-set townscapes. International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA), Brussels, IFLA, 1-9

Pieris A (2018) Re-reading Singapore’s “Black and White” architectural heritage: the aesthetic affects and affectations of adaptive reuse. Archit Theory Rev 22(3):364–385

Pintossi N, Kaya DI, van Wesemael P, Roders AP (2023) Challenges of cultural heritage adaptive reuse: a stakeholders-based comparative study in three European cities. Habitat Int 136:102807

Ren L, Shih L, McKercher B (2014) Revitalization of industrial buildings into hotels: anatomy of a policy failure. Int J Hosp Manag 42:32–38

Ribera F, Nesticò A, Cucco P, Maselli G (2020) A multicriteria approach to identify the highest and best use for historical buildings. J Cult Herit 41:166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2019.06.004

Saccaggi B, Delport T (2015) Occupying heritage: from a Leprosy Hospital to an informal settlement and beyond. J Community Archaeol Herit 2(1):40–56

Sahoo SK, Goswami SS (2023) A comprehensive review of multiple criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods: advancements, applications, and future directions. Decis Mak Adv 1(1):25–48

Saaty TL (1980) The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting. Resource Allocation, RWS Publications, USA

Sharifi AA, Farahinia AH (2023) A theoretical framework for developing the MAU model todetermine the most appropriate use for historic buildings. Eng, Constr Archit Manage 30(1):238–258

Shehata W, Langston C, Sarvimäki M, Smith J (2023) Challenging uncomfortableness: the adaptive reuse of Bendigo Gaol into Ulumbarra Theater and School. Herit Soc 16(2):109–133

Shen LY, Langston C (2010) Adaptive reuse potential. Facilities 28(No.1/2):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/02632771011011369

Smith L (2006) Uses of Heritage (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203602263

Tourism Development Committee of Macau SAR (2016) The Second Plenary Meeting of Tourism Development Committee 2016 held on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2022, from Website: https://www.cdt.gov.mo/news_view.php?id=1&nid=76&lang=en, Accessed 2 Nov 2024

Ung V-M (2015) The ‘Historic Centre of Macau’ as a World Heritage Site and the preservation of Macuo’s cultural heritage. Rev Cult Chin Ed NO 95:31–46

Vaidya OS, Kumar S (2006) Analytic hierarchy process: an overview of applications. Eur J Oper Res 169(No. 1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2004.04.028

van Laar B, Greco A, Remøy H, Gruis V (2024) What matters when?–An integrative literature review on decision criteria in different stages of the adaptive reuse process. Dev Built Environ 18:100439

Vardopoulos I (2019) Critical sustainable development factors in the adaptive reuse of urban industrial buildings. A fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Sustain Cities Soc 50:101684

Vehbi BO, Günçe K, Iranmanesh A (2021) Multi-criteria assessment for defining compatible new use: Old administrative hospital, Kyrenia, Cyprus. Sustainability 13(4):1922

Wang H-J, Zeng Z-T (2010) A multi-objective decision-making process for reuse selection of historic buildings. Expert Syst Appl 37(No. 2):1241–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2009.06.034

Wang SY (2020) A social approach to preserve difficult heritage under neoliberalism–a leprosy settlement in Taiwan and beyond. Int J Herit Stud 26(5):454–468

Wyatt B (2025) Penal heritage hotels as sites of conscience?: Exploring the use and management of penal heritage through adaptive reuse. Tour Manag 106:105026

Yasemin Çakır H, Edis E (2022) A database approach to examine the relation between function and interventions in the adaptive reuse of industrial heritage. J Cult Herit 58:74–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2022.09.015

Ye X (2021) Making post-colonial place identity: the regeneration of the St Lazarus neighbourhood, Macau. Open House Int 46(1):114–129

Ye X (2024) A heterotopic reading of heritage: The Village of Our Lady in Ka Ho, Macau. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. Wiley Online Library

Yen Y-Y (2013) The history of the historic centre of Macau as a World Heritage Site. Macau, Macau Heritage Ambassadors Association, Macau

Yung EH, Chan EH (2012) Implementation challenges to the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: towards the goals of sustainable, low carbon cities. Habitat Int 36(3):352–361

Zhao LC, Zheng YY, Lin JY, Shen K, Li RT, Xiong L, Zhu BW, Tzeng GH (2024) An ex-ante evaluation model of urban renewal projects for the sustainability potential towards TOD and AUD based on a FDEMATEL-GIS-FI approach. Int J Inf Technol Decis Mak 23(06):2309–2333

Zhu B-W, Xiao YH, Zheng W-Q, Xiong L, He XY, Zheng J-Y, Chuang Y-C (2022) A hybrid multiple-attribute decision-making model for evaluating the esthetic expression of environmental design schemes. SAGE Open 12(2):215824402210872. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221087268

Zhu BW, Feng CW, Xiong L, Zheng WQ, Wang GQ, Zhang X, Tzeng GH (2025) Rule sets for identifying conditional attributes of campus green spaces with enhanced mental restoration effect. J Urban Plan Dev 151(1):04024069

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Faculty Research Grants funded by Macau University of Science and Technology (No. FRG-24-066-FA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenkai Li contributed to conceptualization, investigation, data curation, data curation, writing original draft preparation, and visualization. Xi Ye participated in manuscript reviewing and editing and was responsible for proofreading the manuscript. Bo-Wei Zhu provided research conceptualization, research design, and supervision. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Ye, X. & Zhu, BW. A decision-making model for the adaptive reuse of ‘buildings of control and reform’: the Nossa Senhora Village, Macau. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 231 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04482-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04482-y