Abstract

China’s commitment in 2020 to its dual-carbon goal, demonstrating its intention to participate in tackling climate crisis, drew the attention of international media, particularly the media of India, which tends to deem China a rival neighbour. Indian media continually reported this announcement and subsequent policies and actions in China, reflecting Indian cognition and attitude toward China’s commitment to climate change and the Sino-Indian relationship. Given that, the present study adopts the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA), using corpus tools Sketch Engine (SkE) and KH Coder to identify and visualise the topics of the 127 reports collected from three mainstream English newspapers in India, namely The Times of India, The Indian Express, and Hindustan Times, analysing the major discursive strategies including nomination, predication, and perspectivization strategy, and explores the national images of China constructed by the reports and uncovers the hidden ideology. The study finds that Indian media are mainly concerned with China’s target, plan, and conditions of the dual-carbon commitment, resorting to specially designed references, negative evaluations, and perspectivization strategies like indirect speech to target China’s energy practice, casting doubt on China’s capability to realise its goal. As regards China’s national image, Indian media construct China as a significant contributor to global climate action while evaluating its international role as a carbon space ‘appropriator’, with ‘too ambitious’ carbon goals and ‘disappointing’ carbon practices. In general, such construction reflects, to some degree, India’s tension against China’s rapid rise in climate governance. In addition, the competition for discursive rights in international carbon politics can also provide an account of the negative construction. The present study visualises the topics and the semantic features, promoting further integration of critical discourse analysis with corpus linguistics. Meanwhile, this analysis contributes to China-related international and regional media studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon neutrality, as defined by the British Standards Institution, entails achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions. Since the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, the need for effective climate governance has emerged as a prominent issue of global concern and intensive discussion in the international media landscape. To surmount this challenge, developed economies, including the United States, Japan and the European Union, dedicated the 21st United Nations Climate Change Conference to adopting The Paris Climate Agreement, pledging to attain ‘net zero emissions’ or carbon neutrality by around 2050 (Zou et al., 2021). Responding to the agreement, China announced its carbon neutrality commitments, also termed the ‘dual-carbon commitment/goal’, at the 75th United Nations General Assembly General Debate in 2020, stating the resolve to reach the carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

China’s announcement of the goal is an obligatory response to climate issues, but it is more of an initiative to reconstruct its national image and enhance its discursive right in global climate governance (Wu et al., 2021). As the largest developing country and the second largest economy, China has been stigmatised as ‘the largest polluter’ or ‘pollution perpetrator’ by the international dominant media, which tarnishes China’s reputation in the global community, of which one of the primary concerns is green development and climate governance (Rauchfleisch and Schäfer, 2018). From this perspective, it is indisputable that China’s dual-carbon goal and plan, which is more drastic and challenging than that of the developed countries though (Zhou et al., 2023), is a self-conscious reaction and determined rectification of its national image, whereby potentially enhancing its discursive right in global governance.

Such an announcement attracted immediate and overwhelmingly excessive attention from India, which can be interpreted as a natural response given the geopolitical concern. On the one hand, India’s mainstream media has long been inclined to align with western media in distortedly interpreting and negatively representing China (Pardesi, 2021), intending to vie with China for possible advantages in every conceivable field (Kapur, 2016). On the other hand, China and India were originally seen as both representative countries as ‘conservative’ in climate governance, lacking the ability to support a comprehensive carbon-neutral transformation (Zhou et al., 2023). China’s proclamation, however, placed India in a disadvantageous position in this field, which induced India, assuming China as the biggest competitor, to display conspicuous insecurity and a certain sense of imbalance (Khan, 2016; Malone and Mukherjee, 2010). Therefore, the Indian mainstream media represented a plethora of reports and comments on China’s carbon-neutral declaration and dual-carbon goals, conveying their appraisal of this policy, and influencing the public’s cognitive preferences.

In recent years, there have been massive studies investigating Indian media’s coverage of China with different topics and events, particularly through the CDA lens, a proven potent instrument for revealing the hidden attitudes, stances, and ideologies (Machin and Mayr, 2012), such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (Khan et al., 2016), the Sino-Indian border conflict (Bhonsale, 2018), the East China Sea issue (George, 2021), etc. It has been found that the Indian media mainly show a particular interest in China’s politics and economy, while the focus on environmental issues is relatively scant, and the construction of China’s image in this regard has barely been investigated. The national image refers to the public recognition and evaluation of situations in manifold fields of a country, which is discursively constructed especially via media discourse (Kunczik, 1997). Media, as the essential channel for people to gain images of world affairs and knowledge of global issues (Chitty, 2007), can effectively affect public views on specific events or entities, particularly and normally of a country, whether portrayed as positive or negative by media reports (Brewer et al., 2003). In the contemporary era, the competition for soft power between countries intensifies. The role of national image, as an important part of the country’s ‘soft power,’ therefore gains prominence in the international arena. Therefore, it leaves the research necessity.

On the above considerations, the present study intends to address the following questions:

-

1.

What are the predominant topics covered by the Indian mainstream media on China’s carbon peak and neutrality?

-

2.

What discursive strategies and linguistic means are predominantly employed?

-

3.

What images of China are constructed by the Indian media? Why?

To address these questions, the present study, with the assistance of corpus tools, adopts the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, 2016; Wodak, 2001) to explore the topic, discursive strategies and linguistic realisations, subsequently exploring what images of China are constructed, and uncovers the underlying ideologies. DHA is chosen as the analytical framework for its wide and adaptable application in exploring image and identity construction (Wodak and Boukala, 2015; Wodak, 2017), which enables the study to delve into the discursive strategies and rhetorical devices used by the Indian media to represent China’s environmental initiatives. Moreover, it helps to reveal the motivations behind the Indian media’s attempts to challenge or undermine China’s efforts to project a positive image in the climate arena.

This paper is structured as follows: ‘Introduction’ is the introduction, in which the research background, research questions, literature review, data and methods, and organisation are covered. ‘Data and Methodology’ presents an introduction to the DHA and the analytical framework drawn on in this study. The elaborated analysis is illustrated in ‘Corpus-based Analysis’, including topic analysis, analysis of discursive strategies, and linguistic realisations, together with images constructed and the underlying ideologies. The discussion of findings and conclusions are presented in ‘Discussion’ and ‘Conclusion’.

Data and methodology

Theoretical framework

DHA is a problem-oriented approach developed by Wodak and her team while researching context and discourse related to anti-Semitism in Austria. It aims at revealing the ideological or stance issues of hegemony, discrimination, and exclusion in discourse, in a bid to improve the public’s cognition of political purpose or designed thoughts and values embedded in the discourse (Wodak and Meyer, 2009). It integrates the socio-political environment and historical background of discourse, and comprehensively analyses the social events and attitudes or stances of the involved actors, which makes it an important theoretical framework for analysing political discourse.

The framework of DHA is ‘triangulated’ (Wodak, 2001: 93), consisting of topics of discourse, discursive strategies, and linguistic means/realisations. The discursive strategy is the kernel part of the DHA framework, with five major strategies distinguished by Reisigl and Wodak (2009, 2016): Nomination, Predication, Argumentation, Perspectivization, and Intensification/Mitigation. Nomination is designed to analyse the names or references of persons, objects, phenomena/events, processes, and actions. Predication focuses on the discursive qualification of specific social actors, objects, phenomena/events, processes, and actions. Argumentation aims at defending and questioning the truth of the claim and the correctness of the standard. Perspectivization is a discursive device that marks the views of discourse producers from a particular stance, so as to indicate intentional participation or disengagement from this position. Intensification/Mitigation plays a part in identifying the ‘deontic’ or ‘epistemic’ (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016: 95) modality of a particular discourse by modifying illocutionary force.

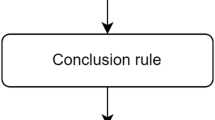

The present paper, however, mainly focuses on nomination, predication, and perspectivization, on account of their predominant occurrence in our data. Referred to DHA and its theoretical framework, the analytical framework of the present paper is designed and shown in Fig. 1:

This figure, taking DHA framework as reference, indicates four analytical steps for the current study: topic analysis, identification of discursive strategies majorly including nomination, predication, and perspectivization, linguistic realisations of three strategies, and finally the image construction analysis. Notably, the second and third steps are combined for the analysis since they are correspondent.

Data and corpus tools

Since the focus of the analysis is to reveal China’s national image constructed by Indian media through the news reports on China’s dual-carbon commitment, a corpus of Indian media’s related coverage was compiled to identify topics and the discursive strategies employed within. As shown in Fig. 1, the main topic of China’s dual-carbon commitment and specific subtopics that Indian media focused on and massively reported pertains to the first step of the analysis. Then, discursive strategies, namely nomination, predication, and perspectivization, and their linguistic realisations will be examined and analysed. Finally, China’s national image will be explored and discussed. During the whole analysis process, diverse corpus tools and corpus-based analytical methods are used to figure out the overall picture.

The corpus of the present study is taken from three mainstream Indian media outlets, namely, The Times of India, Indian Express, and Hindustan Times. They are all English language media because (i) they typically demonstrate the voice of the Indian upper class and are widely concerned by governance groups; (ii) most of the representative and influential views that shape public opinion toward China come from the non-government strategic analysts, retired generals, and civil servants who often express their opinions in these English-language media (Tang, 2010). Thus, the English-language media were chosen as they have a significant influence on public opinion and the institution of Indian foreign policies.

The incorporation of the corpus method aims to assist the analysis in order to avoid subjectivity or the problem of arbitrary data collection (Baker et al., 2013) as much as possible. Two corpus tools were applied in this study, namely Sketch Engine and KH coder. The former was used to generate frequency lists of key terms, helping to identify the most recurrent topics in the discourse, which provided a quantitative foundation for understanding media focus on China’s dual-carbon commitment. KH Coder, on the other hand, was applied for its ability to visualise co-occurrence networks, revealing relationships between these high-frequency words and the clustering of specific topics. The use of the KH Coder allowed for a deeper qualitative insight into the discursive patterns. These tools complement each other, and together ensure a robust and balanced analysis of the discursive strategies used by Indian media.

Research method

The media reports were downloaded from Factiva, covering the period from Sept. 22, 2020, when China officially declared its dual-carbon goal, to Jun. 22, 2022, the day when the current research commenced. The search keywords consisted of ‘China SAME (carbon neutrality or carbon offset or net-zero or carbon neutral carbon peak),’ encompassing the prevalent terms of the carbon neutrality that emerged globally, and setting the simultaneous presence of China and keywords within the same paragraph to increase the relevance. Out of the 203 reports retrieved, 127 were deemed as evidently related and chosen for further identification and analysis, after discarding some irrelevant news. Meanwhile, this research uses Sketch Engine (SkE) and KH coder as corpus tools to annotate and analyse the data. The selected 127 reports with about 68,000 words are processed into a corpus by SkE.

The analysis is divided into three steps: topic analysis, discursive strategies, and image analysis. For the sake of specificity and logicality, the topic analysis consists of two parts. First, the general topic of the entire data collection was identified by listing and analysing the top high-frequency words. Then, the analysis attempted to clarify which aspects of China’s dual-carbon commitment were emphasised and reported by Indian media discourse, which can be called the specific topics, by examining the co-occurrence network. The clarity of China’s dual-carbon goal, which encompasses various aspects and receives differential attention from the media (Shi and Tong, 2021), is conducive to preventing a diffuse and dispersed analysis. The study selected the top 30 high-frequency notional words (mostly nouns) with the Loglikelihood value at least above 3.84 in SkE to ensure the statistical significance at the 95% confidence level, and derived the list. After that, by importing the whole corpus into the KH coder and highlighting these words, the variation of centrality among high-frequency words was scrutinised more rigorously to ascertain the topic effectively. For measuring word distance, the Jaccard coefficient was selected as its emphasis on whether specific words co-occur or not. In addition, once a high-frequency word alone was found insufficient to identify a topic, the reading was extended to a larger stretch, like concordance lines, paragraphs, texts, and even the full article. In terms of the second step, discursive strategies were annotated, with relevant words and concordance lines according to each discourse strategy analysed. Finally, on the results of the above steps, China’s images constructed were analysed and explained.

Corpus-based analysis

Topic analysis

It has been found that Indian media’s discourse on China’s dual-carbon commitment is multifaceted, covering environmental, policy, economic, and technological aspects. It also suggests a narrative closely tied to the bilateral relations between India and China, with a critical eye on the implementation and impact of China’s environmental policies. To be specific, the kernel part of the corpus indicates that the current ‘climate action’ which necessitates financial and technical support ought to be considered and conducted, and countries, in particular China and India, prominent emitters around the world, have to take actions and be responsible for the reduction of carbon emission, finally achieving the goal of net-zero. The list and the co-occurrence network are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2:

Each node in this figure corresponds to a high frequency word (30 in total) in Table 1, showing the centrality betweenness (in Jaccard index) of these words. The darker the colour of the node, the higher betweenness of the node word, which indicates the number of shortest paths for a node to traverse the network, meaning that the node bridges other nodes and reoccurred in significant contexts and topics in the corpus, i.e., China, India, emission, climate. The thicker edge indicates a stronger connection between the nodes and vice versa. MST in the figure means ‘minimum spanning tree’, which helps to understand which elements of a story are most closely linked, revealing the structure and focus of the corpus.

It is explicit that ‘India’ and ‘China’, with the highest frequency or centrality, are the core of Fig. 2, indicating a strong focus on the two geopolitical entities. Other frequently occurring words like ‘climate’, ‘emission’, ‘carbon’, ‘net-zero’, etc., otherwise suggest a significant emphasis on environmental issues, which is the major topic to be concerned. Words like ‘target’, ‘plan’, ‘goal’, ‘action’, ‘commitment’, and ‘neutrality’ point towards discussions on policy-making and action plans. Meanwhile, ‘year’ and ‘time’ highlight the importance of timelines and the scheduled time for achieving dual-carbon goals. In addition, ‘finance’ and ‘technology’ indicate the financial and technological considerations of the commitment, corresponding to the kernel part of the corpus.

Since the words of policy/plans and schedule time are mostly connected with China, it can be inferred that China has already made an announcement with detailed schedule and plans in dealing with the consumption of fossil energy, which is the major force of emission production, so as to realise an energy transition. Therefore, the reported China’s dual-carbon commitment should be a complex, multifaceted plan, which is necessary to identify further the specific aspects of the commitment that the Indian media is particularly focusing on. In other words, the contents following ‘China’ or ‘China’s,’ which are mostly specific subtopics related to China’s dual-carbon commitment, that is, to explore the co-occurrence network with the limitation of taking ‘China’ and ‘China’s’ as the core.

By inputting the corpus and high-frequency words into the KH coder for processing and generating the co-occurrence network, four parts were found to be mainly involved in reports, presented in Fig. 3.

This figure, anchoring ‘China/China’s’ as the core word, uses modularity network to identify which specific topics were focused in the corpus. Modularity network analysis can identify the modular structure of a network, that is, a tightly connected group of nodes. By generating different colours of node groups, the clustering of topics and the intensity of the relationship associated with ‘China/China’s’ can be observed.

There are four major branches in the figure that are in different colours. By examining the concordance lines, it can be clear that the left branch, where the core word ‘China’ is located, indicates the context of China’s announcement of the dual-carbon commitment, i.e., ‘the world climate crisis’, ‘the economic recession caused by COVID-19’, ‘China, as the world’s largest emitter’. The upper branch demonstrates China’s target and its scheduled time, which is net zero by 2060. Furthermore, the bottom branch focuses on China’s plan and detailed actions to achieve the target, i.e., ‘adjust the use of fossil fuel’, ‘conduct energy transition’, ‘manage the use of electricity’, ‘the cooperation of power sectors’, while the right branch is concerned with the requiring preconditions/capabilities for China to implement the strategy, such as ‘finance’, ‘technology’, etc. Therefore, the specific topics by Indian media on China’s dual-carbon commitment can be identified as (i) target/goal, including the target of the commitment and time to achieve the dual-carbon goal; (ii) plan, including policies, actions, measures and effects they have brought about; (iii) abilities or conditions for implementing the goal and latent problems within the process.

Discursive strategies and linguistic means

Nomination

As previously mentioned, the nomination strategy refers to the names or references of persons, objects, phenomena/events, processes, and actions. To be specific, the strategy focused on how the actors involved with the dual-carbon commitment are named and referred to linguistically. It is found that those Indian reports predominantly presented China with two types of actors: China (authority) and Chinese corporation. The recurrent referential terms are shown as follows:

As shown in Table 2, in addition to the common references such as ‘China’ to refer to China when mentioning such national strategy (Wang et al., 2020), the ‘professional anthroponomy’ (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p.112) like ‘Chinese government’, ‘proper name’ (ibid) such as ‘(Chinese) President Xi’, the ‘deictic and phoric expressions’ (ibid) like ‘Beijing,’ some ‘collectives’ (ibid) like ‘major/largest emitter/polluter,’ and ‘China’s internet/tech firms’ are also used by the media reports. In further exploration of the concordance lines and broader texts, the six nominations were found to have connections separately with the three subtopics, shown in Table 3.

The term ‘(Chinese) President Xi’ can also be understood as a metonymic reference in the discursive construction of social actors in nomination strategy, with metonymic meaning: leader for (represents) the nation. With the examination of concordance lines, such reference is found frequently co-occurred with the ‘Target’ of China’s dual-carbon commitment, illustrated in examples (1) and (2).

-

(1)

Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged to bring the country’s climate-warming emissions to a peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

(Hindustan Times, 21/4/2021, 28/5/2021)

-

(2)

President Jinping has said that his country will aim for its emissions to reach their highest point before 2030 and for carbon neutrality to be achieved by 2060.

(The Times of India – Times Now, 17/9/2021)

Chinese President Xi Jinping, for the first reference, is presented as the central actor (‘the leader’) who has made a pledge to address climate-warming emissions. The term ‘pledge’ emphasises a personal commitment and authority. By framing it as a pledge, the President’s individual responsibility and determination are highlighted so as to nominate him as the key agent responsible for addressing emissions and achieving carbon neutrality, positioning him as a decisive figure in the national strategy. In the following example, President Xi Jinping’s statement is framed as an aim for China’s emissions trajectory. The term ‘aim’ suggests a strategic goal, and by attributing it to the President, it is nominated as the driving force behind the emission trajectory and dual-carbon goal, reinforcing the role in shaping the national strategy.

To further elaborate, compared to using ‘China’ or ‘Chinese government’ as the subject, the reports highlight individual agency and decision-making power, as well as implying personal involvement and ownership. It achieves the function of empowerment, accountability, and strategic communication: 1) the choice empowers the leader, emphasising their agency in addressing critical issues; 2) it holds the leader accountable for achieving stated goals; 3) such phrases simplify complex narratives for public consumption (Bunders et al., 2021; Palmieri and Mazzali-Lurati, 2021; Zhang and Orbie, 2021). Meanwhile, it may trigger the argument about the oversimplification of complex decision-making processes, or overlooking the collective efforts of experts, advisors, and institutions.

Therefore, such a construction of carbon commitment is attributed to less rationality, potentially obscuring the collective decision-making involved (Franks et al., 2003). A similar construction is also shown in example (3).

-

(3)

President Xi Jinping promised to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

(Hindustan Times, 21/11/2020)

The word ‘promised’ prominently shows the power of a political leader (Susilowati and Ulkhasanah, 2021), underlining the personal weight of leaders and strengthening the negative perception of China’s dual-carbon commitment.

Concerning the ‘Plan,’ the reports predominantly paid attention to the implementation effect so as to make a judgement on the rationality of the specific plan of the strategy, with a particular focus on Beijing, the capital of China, also the ‘metonymic toponym’ (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p.112) in nomination strategy: capital for (represents) the nation. Indian media, in this case, tends to simplify the complex issue of energy management and climate change as well as potentially shift the blame to a single entity, which can have implications for how the public perceives the effectiveness and rationality of the policies in question. The example is as follows:

-

(4)

…the backdrop of crippling energy shortages that China faced in September and October, partly triggered by coal companies cutting production to meet Beijing’s climate change pledges.

(Hindustan Times, 10/11/2021)

As mentioned above, the subtopic ‘plan’ includes specific actions and effects. Example (4) described such an action as coal production cut, and the effect brought by the action was crippling energy shortages, indicating that the implementation of carbon neutrality is unsatisfactory. The final part of the example contains an intention for impute, ascribing negative results to Beijing’s pledge and conduction and thus depreciating the whole implementation.

Regarding ‘condition’, Indian media intended to label China’s role, that is, to underline a specific attribute, in this case, its negative role in carbon emissions, while potentially downplaying other aspects or efforts of the country, thus questioning China’s ability to complete the carbon goal. Examples are as follows:

-

(5)

Its actions will still be more progressive compared to the largest emitter, since India’s cumulative emissions (1900–2100) would be lower than China’s.

(Hindustan Times, 14/10/2021)

-

(6)

However, as the world’s biggest carbon polluter, questions over whether China could complete its climate change commitments loom large.

(The Times of India – Times Now, 11/11/2021)

The special nomination can have a significant impact on the perception of those actors. Example (5) presents China as ‘the largest emitter’, highlighting its current negative contribution to the international climate crisis. The ‘cumulative emissions (1900–2100)’ refers to a historical and future perspective, which adds a sense of fairness and responsibility to Indian media reports. In example (6), the reference ‘the world’s biggest carbon polluter’ implies a negative and critical evaluation. By using these terms, the media can influence the audience’s understanding of China’s role in global emissions, suggesting a dominant and negative contribution to the issue of climate change. The use of the superlative degree in these examples serves to single out China as the most significant ‘contributor’ to carbon emissions, which can create a sense of urgency or blame, and also lead to questioning China’s ability or commitment to achieving its carbon goals, as mentioned in the second example. The phrase ‘questions over whether China could complete its climate change commitments loom large’ implies doubt and scepticism about China’s intentions and actions regarding its climate pledges, leaving a lack of trust and confidence in China’s capability.

Such description contributes to a discourse that holds 1) China is inept in reducing adequate carbon emissions to complete its 2060 commitment in such a short period because of China’s current huge number of emissions, intending to constrain the public eye merely on China’s polluting factor, and 2) China solely responsible for the challenges in meeting global climate goals, potentially ignoring the contributions and responsibilities of other nations. In addition, such a construction also put China, the largest emitter, into an opposite position to those developed, less-emitted economies, dividing China into the group that could not achieve the goal of carbon neutrality rather than the group that has embarked on the path of carbon neutralising for decades and been on the verge of success with sufficient financial and technical support, in which those economies stand.

In summary, Indian media highlights China’s role as a major carbon emitter, casting doubt on its ability to fulfil its climate change commitments. This strategy simplifies the narrative and can influence public perception and international discourse on climate action and responsibility.

However, a handful of constructions have used anthroponyms as an explanation and defence of China’s poor preconditions for achieving the goal, as illustrated below.

-

(7)

As the largest producer and consumer of coal and coal-based thermal power, it is understandable that China would prefer a gradual reduction rather than total elimination.

(Indian Express, 15/11/2021)

The expression ‘it is understandable’ is used to refer to China’s compromising action, which implies a sympathetic and empathetic evaluation. It can be seen from the example that not all media reports constructed and presented China’s dual-carbon commitment negatively.

To conclude, the nomination is a frequently adopted discursive strategy for constructing China’s image on the dual-carbon commitment by Indian media, intending to create a deliberate divide between policymakers and the masses, between regions and the capital, thereby weakening the legitimacy of the strategy and shaping negative public opinions.

Predication

The predication strategy is designed to discursively qualify social actors, events, objects, etc. It can, for example, which is also the most frequent cases, be realised as evaluative attributions of negative and positive traits in linguistics form of implicit or explicit predicates, adding labels, and thus has to be examined related to nomination strategy (Susilowati and Ulkhasanah, 2021). The analysis, in accordance with the definition, explores high-frequency evaluative words or collocations that occur as the modifier of references listed above (Table 4):

Various evaluative attributions were intensively used to qualify different references that were analysed in the nomination strategy. In general, it is common to use ‘China’ or ‘Chinese government’ as a subject in related statements or descriptions when discussing and focusing on such national strategy. Meanwhile, Table 4 shows that a considerable proportion of focus and weight are also allocated to ‘Chinese president/president Xi’ and ‘Beijing’, corresponding to the previous analysis: to highlight the authority of the individual leader and the capital. The purposes of such constructions will be analysed later.

As illustrated, Indian media constructed ‘China’ by means of mixed predications, such as neutral, declarative predications: ‘deliver climate plans,’ ‘pledge to reach carbon neutrality,’ ‘committed to net-zero goal,’ negative predications: ‘have appropriated 73% of the carbon space’ (example 8), ‘is categorised as highly inefficient’ (example 9), as well as positive predications: ‘China committed… is a big breakthrough’ (example 10)

-

(8)

…China’s emissions will be between 29.5% of global emissions between 2012 and 2030…the analysis (Climate Change: Science and Politics, a book released by the Centre for Science and Environment) revealed

(Hindustan Times, 24/10/2021)

The old industrialised countries and the new entrant, China, have appropriated 73% of the carbon space till 2019

(Hindustan Times, 29/10/2021)

-

(9)

Though China has declared that it will be carbon neutral by 2060, it is in the ‘highly insufficient’ category according to the climate action tracker.

(The Times of India, 20/11/2020)

(The Times of India - Mumbai Edition, 19/11/2020)

(The Times of India - Hyderabad Edition, 19/11/2020)

-

(10)

China committed itself to a net-zero target…is a big breakthrough, especially since countries have been reluctant to pledge themselves to such long-term commitments

(Indian Express, 3/10/2020)

In example (8), China is constructed as ‘appropriated’ most of the carbon spaces (about 30% in 73% total), that is, the space for carbon emission. The development of a country is inseparable from energy consumption and emissions, and the emission space is the common aspiration shared by most developing countries, essentially representing the right to development (Yang and Chen, 2022). The use of the verb phrase implies that both the old industrialised countries and China have taken over or seized the ‘carbon space’ without proper authority or consent, and have deprived other countries of their fair share of the developmental spaces. Such construction, therefore, undoubtedly puts China on the opposite of not only developing countries but also countries that crave development, separating it from the ‘developing’ group where China should have been placed. Also, this description may guide the public to believe that the implementation plan of China’s dual-carbon commitment is to continue to appropriate emissions space, thereby reducing the rationality of the plan at the international level. The phrase ‘has declared’ in example (9) suggests that China has promised or pledged to the international community and expects to be held accountable for it. However, China is attributed as ‘highly insufficient’ in achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 with the quotation of a report from Climate Action Tracker, a European independent scientific project, which means that China does not take responsibility for its commitments. Such a construction is justified as it is a consequence of following authoritative voices about specific issues (Reyes, 2011), exposing China’s inconsistency and insufficiency in climate action and questioning China’s reliability and sincerity in achieving carbon neutrality.

Given that, China is negatively constructed, and the audience’s opinions are effectively shaped as they are more likely to adhere to authority (Reyes, 2011). However, this claim is a kind of ‘fallacy’ (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p.117) of authority-preferred. It does not make sense to negate or depreciate the entire national strategy only by authority voice, needless to say whether the ‘authoritative’ voice is exactly correct and impersonal. In spite of this, the above representative examples and many similar constructions within the reports formed a robust negative semantic field, creating an image of a rising power of rapid expansion but a lack of sufficient ability.

However, a few reports have praised China’s announcement, as shown in examples (10), taking into account the current gloomy environment and China’s unfavourable conditions. These are the compliments on the ‘target’ of the strategy, while the following two are critical of the ‘target’:

-

(11)

This could depress China’s ambitious climate plans (peak by 2030 and neutrality by 2060).

(Hindustan Times, world-news, 28/5/2021)

-

(12)

…he (president Jinping) has not outlined a plan on how he intends to achieve his extremely ambitious goal.

(The Times of India - Times Now, 17/9/2021)

The example (11) describes the target as ‘ambitious’. Such a word suggests that the target is too high or difficult to achieve. The intention of this predication is to cast doubt on whether China can reduce its carbon emissions and combat climate change on its scheduled time. In example (12), the phrase ‘he has not outlined a plan’ is another negative predication that implies that China’s president is vague or secretive about his strategy. The word ‘extremely’ also intensifies the word ‘ambitious’ and makes the goal sound more unrealistic or improbable. The intention of this predication strategy is to question China’s credibility and transparency in its climate goals. Both examples question the rationality of the ‘target’ (scheduled time), conveying a view to audiences that maybe China should reassess and redefine its goals.

With regard to the reference ‘Beijing,’ the negative constructions were realised by highlighting the devastating impacts of its actions. For instance, Beijing is questioned by the action of increasing coal-fired plants built, as it is ambivalent to the goal of carbon neutrality (example 13), the word ‘lofty’ in this example conveys a sense of arrogance or superiority that China may have in its plan implementation, challenging China’s sincerity and feasibility in its carbon reduction plan. In example (14), China is facing public discontent over its current power cut and energy shortage caused by the implementation of the carbon plan, implying its plan is irrational and helpless in balancing its economic and environmental needs. Both examples implied the wrong decision or execution of Beijing that incurred serious damages to public livelihood at a national level. Therefore, its climate plan is ‘disappointing’ (example 15). Additionally, the phrase ‘the world’s biggest emitter’ in example (15) emphasises China’s responsibility and impact on global climate change as well as criticises China’s lack of action in its climate policy.

-

(13)

The new report titled ‘China’s carbon neutrality target implies planned coal power expansion cannot go ahead’, questions the lofty promise given Beijing’s plans to build more coal-fired plants.

(Hindustan Times, 21/11/2020)

-

(14)

Beijing has to burn more coal to ensure domestic consumption needs are met and to calm anger over power cuts.

(The Times of India – Times Now, 11/11/2021)

-

(15)

Beijing’s new climate plan is disappointing and well off where the world’s biggest emitter needs to be.

(Hindustan Times, opinion, 1/11/2021)

The significant point is that the three reports put Beijing, or to say, the Chinese implementation of carbon goal into a dilemma, as reports negate Beijing’s move to increase coal consumption in example (13), considering it as ambivalent to the carbon neutrality goal, while criticising the power cut caused by Beijing’s carbon reduction and ask to support people’s livelihood in example (14). In other words, no matter what is done, the implementation of Beijing is disappointing, as presented by the media, which also shows the discourse trap embedded in the construction of Indian media discourse toward China and its dual-carbon commitment.

Example (16) and example (17) focus on the role of Chinese internet and tech firms in the implementation of the carbon goal, describing that they have made little contribution to the promotion of achieving the carbon peak and carbon neutrality goal, presenting negative impressions.

-

(16)

The report, however, said that carbon emissions from China’s internet industry are projected to continue to rise through 2035, long after its targeted 2030 national emissions peak, creating complications for the country’s carbon neutrality commitments.

(Hindustan Times, world-news, 28/5/2021)

-

(17)

China’s tech firms are not adopting clean energy ‘fast enough’ to mark their commitment towards carbon neutrality, environmental group Greenpeace has said in a report.

(Hindustan Times, world-news, 20/4/2021)

The words ‘continue to rise’ and ‘creating complications’ in example (16) are negative predications that depict China’s internet industry (firms and companies) as not reducing their carbon emissions and are hindering China’s progress towards its carbon neutrality target, revealing China’s challenge in its carbon reduction plan. In example (17), ‘not…fast enough’ suggests a sense of urgency or pressure that China needs to act more quickly or decisively in its energy transition, claiming China’s current performance and implementation of its plan is far from satisfactory. Either ‘creating complications’ or ‘not adopting clean energy fast enough,’ the reports aim to construct a negative image of these firms, indicative of tension between enterprises and the government as the former is guided by the latter (Qi et al., 2021).

Perspectivization

Perspectivization strategy mainly focuses on the quoted speeches, including (free) direct speech and indirect speech, aiming to locate the author’s point of view and detect the author’s involvement or alienation (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009). Direct speech refers to reporting the exact original words, which is the most faithful to the original speech, without the reporters intervening. Indirect speech refers to the reporter’s paraphrase of the original content without being verbatim. Free direct speech refers to partially presenting the quotation of the original contents. The employment of speeches functions to fill the reports, endow authority and credibility, or even implicitly achieve purposeful discursive construction (Table 5).

In this section, the analysis paid crucial attention to the types and sources of speeches cited in the reports, especially those related to the aforementioned references, aiming to speculate the stances and intentions of the discourse producer. The distribution of speech types is as follows:

It can be seen from the table that indirect speech accounts for the largest proportion, followed by direct speech and free direct speech. By examining the speeches in concordance lines, the main information sources of speeches were identified, namely ‘governmental organisations’, ‘non-governmental groups’, and ‘officials and experts’. Most of the citations came from India, while a portion of those came from Europe, thus the citation source is not the major focus of analysis in this section.

Most direct and indirect speech related to evaluating China’s strategy is frequently used when quoting ‘officials and experts’. Reports adhered to the expert’s voice to indicate China’s scheduled time is unmatched (example 18) or lacks further progressive actions (example 19 and 20).

-

(18)

Referring to the CSE analysis on the issue, she (Sunita Narain, environmentalist and director general of the New Delhi-based policy group, Centre for Science and Environment) said, ‘… The fact is that the world must reach net-zero by 2050, which means that the OECD countries should get there by 2030 and China by 2040.’

(The Times of India, 4/11/2021)

-

(19)

Many experts said China has not committed to much more than what it had promised in 2016.

(Hindustan Times, 2/11/2021)

-

(20)

Lauri Myllyvirta, the lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, tweeted: ‘China’s new climate commitment under the Paris agreement has been published. It turns the 2060 carbon neutrality target and CO2 emissions peak before 2030 into new formal pledges but doesn’t shed more light on the emissions trajectory over this decade.’

(Hindustan Times, 1/11/2021)

In examples (18) and (20), the writer uses direct speech to quote the expert’s words verbatim, which gives more authority and credibility to their voice, as it indicates that the writer respects their expertise and opinion. It also creates a sense of immediacy and vividness, as if experts are speaking directly to the readers, which is assumed to be more persuasive in convincing the audience of the thesis. However, in example (19), the writer uses indirect speech to paraphrase what many experts said. This shows that the writer does not want to give specific names or details of the sources, but rather to generalise and summarise their views. Interestingly, almost all direct speeches were adopted to present the views of experts with clear names, while indirect speech is used more frequently when citing unknown experts. Fairclough (1995, p.61) once pointed out that the media tends to ‘use indirect speech to blur the line between the quoter’s and the quoted’s discourse and drowning out the quoted’s voice with that of the quoter.’ In other words, the discourse producer may only be inclined to dress the individual and biased opinion in the voice of authority.

The type of free direct speech may better achieve the above purpose. It was frequently used in terms of ‘non-governmental organisations’. Examples are as follows:

-

(21)

Though China has declared that it will be carbon neutral by 2060, it is in the ‘highly insufficient’ category according to the climate action tracker.

(Hindustan Times, 21/9/2021)

(Indian Express, 18/11/2021)

-

(22)

China’s tech firms are not adopting clean energy ‘fast enough’ to mark their commitment towards carbon neutrality, environmental group Greenpeace has said in a report.

(Hindustan Times, 22/4/2021)

Both examples partially cited the words or phrases from the original to indicate that China is ‘insufficient’ or not enough to achieve its 2060 carbon-neutral goal. However, the context and exact meaning of the original and the evaluative words remain unknown. The original verbalisation, by means of partial citation, is deliberately interwoven into the constructed sentences, with personal views and understanding towards original contents also infiltrated within, which is inevitably filled with stances. By forming such a patchwork reporting, the media varnished the individual views with the authority of the reports and its organisations, so as to powerfully influence the audience’s judgement.

Images constructed

Through the analysis of the nomination, predication, and perspectivization strategies, this study identified and analysed the references to the actor of China, the evaluative attributions used to construct different references, and the citation types and sources. The above analysis shows that the Indian media generally constructed a negative image of China in relation to carbon neutrality by applying discursive strategies, questioning China’s capacity and feasibility in implementing dual-carbon commitment.

In order to figure out more elaborate images constructed, some further steps are taken: putting references of China as the centre to find out the modifiers (evaluative attributions) through KH coder, then generating the co-occurrence network and checking the coefficient and centrality to inspect which attributions are most closely connected with those references, coupled with the examination of the voices’ sources through perspectivization strategy. Taking the reference ‘China’ in Fig. 4a, b as examples

Each graph shows the words in different part of speech (POS) that modify the reference ‘China’, while (a) is the adjective modifiers and (b) is the verbal modifiers (verb). Basically, this figure is the enhanced version of centrality network, with coefficient value presented. It reflects the closeness of the nodes in the network, that is, how likely a node’s neighbours are to be connected to each other. A high coefficient value may mean that there is a strong connection between nodes, which means the node is frequently used in modifying/co-occurring with the centre node, and vice versa.

By checking the co-occurrence network, the adjective most closely related to the reference is ‘neutral (0.77)’ in Fig. 4a, while ‘significant’ also has a higher coefficient (0.54) and higher centrality, for which it is selected. On the concordance line, it is stated that China’s announcement of its dual-carbon goal is significant to the global net-zero commitment in general. Meanwhile, the most frequently used verb is also picked up as ‘appropriate (0.99),’ in Fig. 4b, as China has appropriated most of the carbon emission space and has squeezed the development space of other countries. Therefore, in this part, China is constructed as a ‘significant contributor’ to world carbon neutrality but an ‘appropriator’ of developmental space.

Following the steps above, the attributions related to ‘Chinese government’, ‘(Chinese) President Xi’, and ‘Beijing’ are meticulously scrutinised. The occurrence of these three references is much less than that of ‘China’, so it cannot be processed as the centre of a whole network but rather be drawn as the kernel of a separate branch. Hence, as shown in Fig. 5a–c, it can be seen that ‘meet’ has the highest centrality in that branch related to ‘Chinese government’, indicating that China has to meet domestic energy needs so as to ‘calm (0.76)’ public anger; ‘ambitious (0.24)’ and ‘achieve (0.52)’ are the two words with high coefficient toward ‘President Xi’, implying that though China’s dual-carbon goal is difficult to achieve through its leader presents strong verbal dominance and determination. As for the modifiers of ‘Beijing,’ the adjective ‘disappointing (0.98)’ is processed as the frequently co-occurring word, indicating that Beijing’s plan of building more coal-fired plants is disappointing regarding its dual-carbon goal while its action that caused power cut and public anger is also disappointing for society.

Other references like ‘China’s internet/tech firms/companies’ or ‘major/largest emitter/polluter’ cannot be processed and presented in the co-occurrence network because their frequency is less frequent in the corpus. Given that, it can only detect the image by highlighting the evaluative attributions toward those references. With regard to ‘firms/companies,’ China’s role constructed by the discourse can be concluded as ‘Insufficient’ since its tech and internet firms are described as ‘not fast enough’ to adapt to the dual-carbon commitment and ‘creating complications’ on the path of achieving carbon neutrality. The reference ‘polluter/emitter,’ however, can directly play a role in constructing China.

Based on the above analysis, the images of China can be summarised in Table 6:

For the target, the media portrays President Xi Jinping as the central figure driving China’s ambitious carbon neutrality goals. His leadership is highlighted in announcements regarding China’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions, portraying China as an ambitious nation with a strong desire to be engaged in leading global climate governance. However, this ambition is often assumed to be met with scepticism when it comes to the feasibility of these targets, as actual progress toward these goals is perceived as remaining unclear. Thus, while Xi’s leadership contributes to the image of an ambitious announcer, the media also questions the reality of achieving these targets.

Regarding the plan, Indian media’s focus on Beijing frequently frames China’s climate action as disappointing. Officials and experts cite firms and companies as key contributors to this disappointment, as complications arise in implementing carbon reduction plans. Despite ambitious goals, China’s climate actions are interpreted as inadequate to meet global expectations. The media further characterises China as the largest polluter, reinforcing the view that its actions are insufficient relative to its emissions output. As a result, the image of China is one of ambition overshadowed by a disappointing lack of substantial progress, compounded by its role as a significant polluter.

Finally, the media portrays China and the Chinese government in a dual light regarding their ability to meet carbon neutrality goals. On one hand, China is depicted as an appropriator of global carbon space, benefiting from its use of carbon resources while significantly polluting and emitting. On the other hand, China is recognised as a significant contributor to international climate initiatives, particularly in its efforts to cooperate with global climate action plans. Non-governmental organisations often critique the Chinese government for failing to meet carbon neutrality deadlines, which leads to an image of China as both an important player in climate efforts and a major power struggling to seek benefits for its own at the expense of others’ development.

Notably, there is no clear voice source for the attributions towards the references like ‘China’ and ‘President Xi’, which leaves a large room for subjective assessment, such as the evaluative terms ‘appropriated’ and ‘extremely ambitious’. The critical voice towards ‘Chinese government’ and ‘Beijing’ has the same source: Draworld Environment Research Centre of Beijing and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air in Finland, whose report questions over China’s plan to build more coal-fired plants. By quoting such an ‘authority voice’, the audience is more likely to talk into the claim that perhaps China does have a problem in implementing its carbon-neutral plan, which is disappointing. Regarding the source of attribution towards ‘firms/companies’, Greenpeace is the most widely recognised environmental pressure group in the world (Eden, 2004), which has considerable authority in judging China’s actions. Quoting their reports makes the news and its media more convincing. By quoting these established sources, the media not only legitimises its critique of China but also subtly directs the audience’s perspective, encouraging them to adopt a more critical stance. This integration of external authority voices strengthens the media’s evaluative position, amplifying doubts about China’s commitment to achieving its carbon-neutral goals.

Consequently, this combination of strategies serves to construct a complex and often sceptical image of China. Despite the longstanding role of the biggest polluter, Indian media portrayed China as a significant contributor to global climate action, an appropriator of developmental space in the global community, an ambitious contender for climate governance, and a failure in keeping and sufficing the commitment.

Discussion

The Indian media’s portrayal of China’s dual-carbon commitment is complex, with the predominant employment of discursive strategies like nomination, predication, and perspectivization. While the value of China’s dual-carbon goal is identified, the media casts doubt on the feasibility and sincerity of these goals. The analysis further underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of logic and reasons behind held by the media to construct national images. Generally speaking, China’s announcement of dual-carbon goals is believed to have great significance to global climate action, targeting itself as a ‘contributor’ to climate governance. However, considering its current condition of being ‘the largest polluter,’ its goal of achieving the carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 is seemingly too ‘ambitious’ to reach. Furthermore, the actual practice of China is ‘disappointing’: the government needs to ‘meet the public needs’ and guarantee the public livelihood, so it has to provide more fossil fuel energy — the opposite towards the goal of achieving the carbon neutral target and net-zero emission. Given that, China’s current ability to complete its carbon commitment is seen as ‘insufficient’ and does not keep pace with the expected progress. In addition, China’s practice at the international level is also being denounced. Its pursuit of carbon emissions space has crowded out and squeezed other countries’ space for emissions and development, resulting in being entitled to ‘appropriator.’ The media’s framing choices demonstrate what van Dijk (2009) terms ‘ideological square’—realising negative other-presentation through selective emphasis and de-emphasis of different aspects of China’s climate commitments.

From a view of domestic interests, Indian English-language media, particularly privately owned outlets, tend to adopt a nationalist editorial stance that invariably maintains scepticism toward China’s initiatives (Bhat, 2023), therefore presenting a negative discursive construction. While acknowledging China’s potential contribution to global climate action, the predominant framing focuses on scepticism and potential threats to Indian interests. This reflects the competitive tendency that environmental initiatives are primarily evaluated through the lens of national strategic interests rather than global environmental benefits. The media’s emphasis on China as an ‘appropriator’ of development space particularly reflects this ideological orientation, positioning environmental action as a zero-sum game rather than a collaborative global effort.

In addition, the Indian media is potentially defending and warning their government (Ahmad, 2023). One of the broad functions of media in international broadcasting is to counter the rival’s dominance (O’Keeffe and Oliver, 2010), even if the potential one. Since a promising movement for carbon neutrality is taking form with enormous efforts to realise its objectives, China has already obtained some reputations and discursive rights in the climate governance field. Therefore, Indian media merited to negatively construct China’s actions, so as to defend their power and rights. Besides, India, as a major developing world economy that has predominantly been highly energy-intensive and fossil fuel dependent, has not been able to safeguard its environment from persistent degradation through the discharge of greenhouse gases, making few contributions to the global carbon emissions (Das et al., 2023), which has received considerable criticism. Considering that the massive penetration of media in society and its role in building public opinion on a phenomenon can potentially change social, political, and even security and defence values (Widodo et al., 2022), Indian media intends plausibly to suggest that it is the time to transfer carbon neutrality from vision to action.

From the international view, the attitude and tactics of Indian media towards China are essentially rooted in the competition in international carbon politics and discrepancies of views (Yang and Chen, 2022). In the field of climate governance, in addition to hard power such as technology or economy, soft power and soft influence generated by discursive actions such as designed discourse, ideas, propositions, and announcements (China’s carbon-neutral announcement) are highly emphasised (ibid). Not only does it play a guiding role in the formation of documents such as agreements, conventions, and frameworks in the practice of carbon politics, but also countries will create systems of political symbols in line with their interests through discourse, and carry out ‘symbolic violence’ (Bourdieu, 2003) against other countries, so as to form priorities in competing national interests and obtaining the greater discursive right and rule-making power. Although mitigating climate warming and coping with secondary disasters caused by climate change has become a global consensus, countries like India are still indulging in zero-sum ideology and adopting containment policies accordingly. The growing polarisation between China and India has strengthened India’s resolve to engage in competition with China (Prys-Hansen, 2022), which may account for the negative construction of China.

Furthermore, the current dilemma of carbon politics stems not only from different appeals of national interests but also from the widely divergent ethical standards that countries hold in dealing with climate issues (Jennings, 2023), specifically manifested as the confrontation between the teleological and deontological orientations (Yang and Chen, 2022). As for the former, the practice is reasonable and acceptable as long as it serves its purpose. In other words, if the practice cannot satisfy the initial preferences, it is not sensible and should be criticised. One of the representative instances is the Indian media’s negative evaluation of China’s plan to build more coal-fired plants. Sticking to teleological orientation, Indian media naturally criticised China’s plan as it runs squarely against the carbon neutrality goal, but without an elaborate consideration of the reason and intention behind it. As for the latter, the practice is not acceptable if it is unfair, even if it is effective in achieving the initial preferences. It is unacceptable for China with a deontological orientation and populace viewpoint to neglect public demand and livelihood in practicing dual-carbon commitment. Given that, China must meet public energy demand even if it would drag the process of dual-carbon commitment. The essential conflicts lie in distinct orientations (Jennings, 2023).

Interestingly, Indian media also criticised the effect of energy shortage and damage to public interest brought about by China’s reduction of fossil energy consumption from the perspective of deontological orientation. It can be seen that in the discourse competition with China, India has adopted a considerably flexible moral orientation.

The analysis reveals how Indian media’s ideological stance is shaped by both domestic and international factors. Domestically, the need to preserve national interests and maintain public support for India’s developmental priorities influences how China’s environmental actions are portrayed. Internationally, the media’s framing reflects broader carbon political competition and divergent ethical standards. This ideological positioning helps explain why even potentially positive developments in China’s climate action are often framed with scepticism or concern. Foreseeably, for competing for legitimacy in the arena of great and emerging global powers, this discourse confrontation in the climate governance field will last long (Malone and Mukherjee, 2010).

Conclusion

This paper explores the construction of China’s national image in the reports on China’s dual-carbon commitment by Indian mainstream media. Employing the DHA as an analytical framework, the present study identifies and analyses the topics and discursive strategies with the assistance of corpus tools. It finds that specific references, i.e., ‘Beijing,’ and ‘President,’ were preferred to refer to China, and negative attributions were added in modifying those references, so as to realise the negative discursive construction of China. In addition, the use of the perspectivization strategy foregrounds the authority of those negative evaluations, putting the biased view under the disguise of authority voice, also revealing its impact on public acceptance and preference. With the coordination of three strategies, China is presented as ‘significant’ but an ‘appropriator’ in global climate action with ‘ambitious’ goals, but is ‘disappointing’ in its practice and is ‘insufficient’ in dealing with its current biggest ‘pollution’. Generally speaking, Indian media constructs a negative image of China, by deliberately foregrounding the inconsistency between its words and deeds, reflecting, to some degree, India’s tension against China’s rapid development and its achievement in climate governance. In addition, the competition for discursive rights in international carbon politics can also provide an account for the construction.

The present study is believed to have made some contributions: (i) the analysis shows that DHA as the theoretical framework can be well applied to analysing the construction of national image; (ii) the analysis may partially shed light on the intention of Indian media and its governmental stance, concerning climate governance; (iii) the corpus tool Sketch Engine and KH coder are proved to be powerful in visualised analysis, which may have a broader application in the further exploration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are downloaded from FACTIVA, available in the Figshare, shown as follow: Wu, Yuxin (2025). Data for manuscript ‘Climate action contributor and carbon space appropriator: national image construction of China in dual-carbon commitment from Indian media’s perspective’ in journal H & SSC. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28334486.v1

References

Ahmad S (2023) Indian media’s China dilemma: Sino-India 2020 face-off through the lens of Indian press: analysis of editorials. In: Zhang SI, Peng AY (eds) China, media, and international conflicts. Routledge, London, p 129–147

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, Mcenery T (2013) Sketching muslim: A corpus driven analysis of representations around the word ‘Muslim’ in the British Press 1998–2009. Appl Linguist 34(3):255–278

Bhat P (2023) Hindu-Nationalism and media: anti-press sentiments by right-wing media in India. J Commun Monogr 25(4):296–364

Bhonsale M (2018) Understanding Sino-Indian border issues: an analysis of incidents reported in the Indian media. ORF Occas Pap 143:1–34

Bourdieu P (2003) Symbolic violence. In: Célestin R, DalMolin E, de Courtivron I (eds) Beyond French Feminisms. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, p 23–26

Brewer PR, Graf J, Willnat L (2003) Priming or framing: media influence on attitudes toward foreign countries. Gazette 65(6):493–508

Bunders AE, Broerse JEW, Regeer BJ (2021) Leadership for empowerment: Analysing leadership practices in a youth care organisation using peer video reflection. Hum Serv Organ Manag Leadersh Gov 45(5):431–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2021.1961333

Chitty N (2007) Toward an inclusive public diplomacy in the world of fast capitalism and diasporas. In: Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs (ed) Foreign ministries: adaptation to a changing world. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Thailand, p 1–22

Das N, Murshed M, Rej S et al. (2023) Can clean energy adoption and international trade contribute to the achievement of India’s 2070 carbon neutrality agenda? Evidence using quantile ARDL measures. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 30(3):262–277

Eden S (2004) Greenpeace. N Polit Econ 9(4):595–610

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis. Longman, London

Franks NR, Dornhaus A, Fitzsimmons JP et al. (2003) Speed versus accuracy in collective decision making. Proc Biol Sc 270(1532):2457–2463

George AM (2021) Constructing the China threat: the Indian strategic community’s discursive interpretation of the East China Sea ADIZ. Common Comp Polit 59(3):296–318

Jennings B (2023) Climate change, relational philosophy, and ecological care. In: Pellegrino G, Di Paola M (eds) Handbook of philosophy of climate change. Springer Cham, Switzerland, p 1–17

Kapur A (2016) Can the two Asian giants reach a political settlement? Asian Educ Dev Stud 5(1):94–108

Khan I, Farooq S, Gul S (2016) China-Pakistan economic corridor: news discourse analysis of Indian print media. J Polit Stud 23(1):233–252

Khan Z (2016) China–India growing strides for competing strategies and possibility of conflict in the Asia–Pacific region. Pac Focus 31(2):232–253

Kunczik M (1997) Images of nations and international public relations. Mahweh, N.J., Lawrence Erlbaum

Machin D, Mayr A (2012) How to do critical discourse analysis: a multimodal introduction. Sage Publication, London, (eds)

Malone DM, Mukherjee R (2010) India and China: conflict and cooperation. Survival 52(1):137–158

O’Keeffe A, Oliver A (2010) International broadcasting and its contribution to public diplomacy. Sydney, Lowy Institute

Palmieri R, Mazzali-Lurati S (2021) Strategic communication with multiple audiences: polyphony, text stakeholders, and argumentation. Int J Strateg Commun 15(3):159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2021.1887873

Pardesi MS (2021) Explaining the asymmetry in the Sino-Indian strategic rivalry. Aust J Int Aff 75(3):341–365

Prys-Hansen M (2022) Competition and cooperation: India and China in the global climate regime. GIGA Focus Asien 4:1–11

Qi SZ, Zhou CB, Li K et al. (2021) Influence of a pilot carbon trading policy on enterprises’ low-carbon innovation in China. Clim Policy 21(3):318–336

Rauchfleisch A, Schäfer MS (2018) Climate change politics and the role of China: a window of opportunity to gain soft power? Int Commun Chin Cult 5:39–59

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2009) The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods for critical discourse analysis, 2nd edn. Sage Publication, London, p 87–121

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2016) The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods for critical discourse analysis, 3rd edn. Sage Publication, London, p 23–61

Reyes A (2011) Strategies of legitimisation in political discourse: from words to actions. Discourse Soc 22(6):781–807

Shi WT, Tong B (2021) 习近平生态文明思想国际传播的图景与路径——以推特平台’2060碳中和’议题传播为例 (The prospect and paradigm of international dissemination of ecological civilisation ideas by President Xi: Taking the issue of ‘2060 carbon neutrality’ on Twitter platform as an example). J Commun 219(4):39–44

Susilowati M, Ulkhasanah W (2021) Ideology and power in a presidential speech. Paper presented at the International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Social Science, Malang, Indonesia, 31 October 2020

Tang L (2010) 印度主流英文媒体报道与公众舆论对华认知 (Indian mainstream English-language media report and Indian public’s perception of China). South Asian Stud 91(1):1–14

van Dijk TA (2009) News, discourse, and ideology. In: Wahl-Jorgensen K, Hanitzsch T (eds) The handbook of journalism studies, Routledge, London, p 211–224

Wang Q, Li S, Pisarenko Z (2020) Modeling carbon emission trajectory of China, US and India. J Clean Prod 258:1–15

Widodo A, Wirajuda MH, Widjayanto J (2022) Social media and its influencers: a study of Indonesian state-defending strategy in the 21st century. Strateg Perang Semesta 8(2):133–144

Wodak R (2001) The discourse-historical approach. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods for critical discourse analysis, 1st edn. Sage Publication, London, p 63–94

Wodak R (2017) ‘Strangers in Europe’: a discourse-historical approach to the legitimation of immigration control 2015/16. In: Zhao S, Djonov E, Björkvall A, Boeriis M (eds) Advancing multimodal and critical discourse studies. Routledge, London, p 31–49

Wodak R, Boukala S (2015) European identities and the revival of nationalism in the European Union: a discourse historical approach. J Lang Politics 14(1):87–109

Wodak R, Meyer M (2009) Critical discourse analysis: history, agenda, theory and methodology. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods for critical discourse analysis, 2nd edn. Sage Publication, London, p 1–33

Wu Y, Thomas R, Yu Y (2021) From external propaganda to mediated public diplomacy: the construction of the Chinese dream in President Xi Jinping’s New Year speeches. In: Surowiec P, Manor I (eds) Public diplomacy and the politics of uncertainty. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, p 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54552-9_2

Yang WD, Chen YY (2022) 国际碳政治的话语权博弈: 基于批评话语的分析视角 (The international competition of carbon politics in the context of critical analysis). J Int Relat 59(5):136-154+159

Zhang Y, Orbie J (2021) Strategic narratives in China’s climate policy: analysing three phases in China’s discourse coalition. Pac Rev 34(1):1–28

Zhou JX, Bai YX, Su Y et al. (2023) 应对气候变化治理模式国别比较分析(Country comparison of governance models for addressing climate change). Chin J Environ Manag 15(4):10–17

Zou C, Xue H, Xiong B et al. (2021) Connotation, innovation and vision of ‘carbon neutrality. Nat Gas Ind B 8(5):523–537

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First author: Wu Yuxin, who wrote the whole paper and the revision. Second and corresponding author: Prof. Zhao Xiufeng, who is in charge of supervision and project administration. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests, financial or non-financial, that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Neither WY nor Prof. ZX has any commercial, financial, or personal relationships that might have influenced the research.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it involved analysis of publicly available media content and did not involve human participants, human data, or human tissue. The research methodology referred to established discursive framework and focused exclusively on published news articles and media content that are in the public domain.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for this study as it did not involve human participants or personal data collection. The research analysed publicly available media content and did not require direct interaction with individuals or collection of personal information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Zhao, X. Climate action contributor and carbon space appropriator: national image construction of China in dual-carbon commitment from Indian media’s perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04529-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04529-0