Abstract

Intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is a valuable cultural resource produced by human beings in the process of environmental adaptation. Its inheritance and protection play a vital role in sustainable social development and human well-being. To address pressing challenges in ICH protection, including improving the effectiveness of conservation funds and achieving integrity living protection, we established universal categories and criteria from a cultural ecology perspective. The intangible cultural heritage threatened-level categories and criteria are intended to be an explicit, easily, and widely understood system for protecting ICH projects according to their threatened risk. Our evaluation criteria assess the threatened level of ICH from the standpoints of both habitats and practitioners. The threatened level of ICH is determined by the higher of the evaluated threatened levels between ICH practitioners and habitats. This level can be further determined by integrating with the existing ICH list systems of various countries, such as the administrative level in China’s Four-tier List System. By applying this system to assess 100 ICH projects spanning 11 categories in Dali Prefecture, China, we demonstrated its simplicity, operability, and applicability across most ICH categories, and consistency with experts’ judgment even in case of incomplete ICH project data. This criteria system marks a pioneering step towards a comprehensive approach applicable to all ICH categories. It seamlessly integrates with China’s ICH Four-tier List System and is well-suited for routine monitoring in cultural ecology reserves precedently established by China, as well as compatible with ICH list systems globally. Through practical implementation, we envision the gradual refinement of this criteria system to enhance ICH protection efforts and bolster global initiatives in safeguarding these invaluable ICH resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intangible cultural heritage (hereinafter referred to as “ICH”) is the crystallization of wisdom and precious wealth created by human beings in the process of adapting to environments. It is a crucial resource for enhancing a nation’s soft power and a valuable part of human civilization, offering historical, cultural, artistic, scientific, and economic values. Protecting ICH contributes to maintaining cultural diversity, fostering human imagination and creativity, and promoting sustainable development in human society.

Japan has been a pioneer in global ICH protection. In the 1950s, Japan took the lead by enacting relevant laws and policies, establishing the Cultural Properties Protection Committee (later renamed the Agency for Cultural Affairs) and other specialized institutions to carry out the identification and protection of ICH resources and their inheritors (Yuan and Gu, 2009). Influenced by Japan, UNESCO has gradually become a promoter and advocate for global ICH protection from the 1970s onwards. Through the issuance of a series of documents, UNESCO promoted the concept of safeguarding ICH to various countries and provided guidance for their ICH protection efforts. The culmination of these efforts was marked by the adoption of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003, which officially led to the initiation of ICH protection work by countries worldwide.

In August 2004, China officially became a contracting party to the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, signaling its entry into the international framework for ICH protection. In response to the Convention’s requirements, China established a Four-tier List System including the national, provincial, municipal, and county administrative levels for compiling the ICH lists. In 2007, China introduced the “Management Measures for National Cultural Ecology Reserves,” and subsequently established national-level cultural ecology reserves and experimental protection zones to ensure the integrity conservation of ICH and its original ecological environments. China’s initiative with cultural ecology reserves is considered an innovative practice in the field of ICH protection and serves as a commitment to fulfilling the obligations of the Convention. Subsequently, China enacted the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Intangible Cultural Heritage” in 2011 and the “Measures for the Recognition and Management of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Inheritors” in 2019, providing legal foundations for the identification and protection of ICH resources and their inheritors. China’s top ranking in the UNESCO World Intangible Cultural Heritage List demonstrates its leading position in the field of ICH protection.

Overall, ICH conservation has achieved notable achievements. However, with evolving recognition and developmental challenges, new hurdles have emerged, which are also urgently highlighted by the UNESCO (2003), such as: (1) Balancing the ICH protection and utilization for sustainable development. The current protection of ICH often falls into extremes: either overly rigid preservation or excessive commercialization; how to explore the value of ICH while maintaining its inheritance and contributing to sustainable social development is an urgent problem that needs to be addressed (Liu, 2007; Alison, 2014). (2) Improving the efficiency of conservation, particularly in allocating funds to protect threatened and less-noticed projects. Some scholars argue that existing national list systems in China, Japan, and other countries cannot fully reflect the actual threatened situation of ICH projects well. For instance, high-level projects in the Four-tier List System of China often receive more attention and have greater advantages in accessing protection resources compared to low-level projects (Xiao et al., 2023; Duan and Sun, 2017). (3) Achieving integrity living protection through the construction of cultural ecology reserves. The construction of a cultural ecology reserve in China is aimed at maintaining and cultivating an ecology environment conducive to cultural health and sustainable development, thereby achieving integrity protection of ICH projects (Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). Hence, the dynamic monitoring of ICH projects and their habitats, along with targeted management based on monitoring, should become the core processes of cultural ecology reserves.

To effectively tackle these challenges, it is essential to establish a comprehensive evaluation framework for the regular monitoring, assessment of threatened status, and sustainable utilization of ICH resources. This framework should facilitate the allocation of funds for ICH protection, the establishment of cultural ecology reserves, the assessment of protection outcomes, the formulation of integrity protection policies, and the promotion of public awareness and education on ICH preservation. In developing this evaluation framework, it is crucial to prioritize living protection principles while ensuring simplicity in application and widespread acceptance. Thus the evaluation criteria should not only consider the ICH and its surrounding environment but also focus on operational ease. Drawing inspiration from established practices in conservation biology within the field of ecology and Steward’s theoretical framework in cultural ecology (Steward, 1955)—which utilizes ecological methodologies to investigate the interplay between culture and the environment—this research establishes an evaluation framework for assessing the threatened status of ICH projects from a cultural ecology perspective. By referencing the well-established indicator system of the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Red List Categories and Criteria in biodiversity conservation, this study aims to systematically examine and address the evaluation of threatened levels and protection strategies for ICH projects.

Materials and methods

Theoretical framework

In exploring the preservation of biological and cultural diversity, several key similarities emerge. First, both biology and ICH are treasured resources meant for the benefit of future generations. Their conservation efforts aim to uphold diversity and sustainability for posterity (Nsamenang, 2015). Secondly, the dynamic nature of animal populations and cultural practices necessitates continuous monitoring and adaptable protection strategies, emphasizing the importance of long-term vigilance. Thirdly, globalization, urbanization, and climate change pose significant threats to both biological and cultural entities, with challenges such as habitat destruction requiring urgent attention (Piccardo & Canepa, 2020). Lastly, effective conservation in both realms relies heavily on community involvement, underscoring the vital role of local knowledge and practices in crafting successful preservation strategies. Their differences distinguish the conservation approaches for biology and ICH. While biological populations serve as the carriers of inheritance in the realm of biology, practitioners embody the carriers of cultural heritage. Furthermore, the focus of protecting biological populations centers on natural ecosystems crucial for their survival, whereas safeguarding culture demands consideration of the social ecosystem.

The theory of cultural ecology, pioneered by Julian Steward in “Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution” (1955), underscores the interplay between culture and its environment, recognizing them as dynamic entities that evolve in tandem. This approach stresses the adaptation and evolution of culture within ecological and social systems, emphasizing the influence of natural resources, climate, terrain, and geographic location on cultural expressions. Regrettably, the application of cultural ecology theory to ICH protection remains under-explored, with limited studies delving into individual ICH projects through this lens. China’s innovative establishment of cultural-ecological conservation areas underscores the parallel between protecting culture and its environment and wildlife conservation, advocating for the integration of cultural ecology theory into ICH preservation efforts. By leveraging this theory, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of culture and ecosystems, a more holistic and effective approach to safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage can be achieved.

The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria is the most widely used system for global biodiversity conservation (IUCN Species Survival Commission, 2010). It evaluates the endangered status of biological populations from two aspects: species population status and habitat condition. Similarly, this ICH threatened level evaluation criteria include the perspectives of ICH practitioners and habitats. Among them, practitioners are equivalent to the population in biodiversity conservation, representing the carriers and foundation of ICH inheritance. Habitats are equivalent to habitats in biodiversity conservation, providing the necessary conditions for the generation, development, and evolution of ICH projects. Drawing from ecological theories, the study first defines the concepts related to ICH practitioners and habitats.

Basic concepts

Practitioner

In this study, practitioners of ICH projects refer to individuals engaged in specific ICH projects, encompassing representative inheritors, general inheritors, and learners (Table 1). According to the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Intangible Cultural Heritage” (hereinafter referred as “the ICH Law”), practitioners who are proficient in inheriting ICH, representative in specific fields, have significant influence in certain regions, and actively carry out ICH activities are considered representative inheritors. Although not officially recognized by the ICH Law, general inheritors who fully grasp and effectively practice ICH projects are regarded as an essential component of inheritors, with the potential to become representative inheritors (Huang and Qian, 2016). Learners refer to individuals engaging in the study of ICH. While they lack the ability to independently inherit ICH, they possess the potential to become inheritors in the future. These three roles serve as the carriers for the inheritance of ICH projects, with their relationship illustrated in Fig. 1. Inheritors (including representative and general inheritors) and learners can be considered as adults and juveniles of ICH “populations”, respectively, and should be incorporated into this evaluation system collectively.

A healthy inheritance structure should be pyramid-shaped, with a larger number of learners and a smaller number of representative inheritors. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Na Li; copyright © Na Li, all rights reserved.

Habitat

The habitat of ICH refers to the environment (including natural and social contexts) in which ICH projects rely for survival, analogous to the habitat of species in biodiversity conservation. It encompasses the populations affected by ICH projects and their spatial distribution range, etc. Based on temporal scope, habitats can be categorized into current and potential habitat, representing the respective present and future environments that affect ICH projects (Table 1).

Threatened-level categories of intangible cultural heritage projects

The classification of the threatened levels of ICH projects is constructed by referencing the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (version 3.1), which include the following categories, listed from highest to lowest threat levels: Extinct, Extinct in the Wild, Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened and Least Concern. In practical application, we have made modifications to two of these categories: Extinct has been redefined as “Complete Extinct,” and Extinct in the Wild has been adjusted to “Functional Extinct” from a cultural perspective.

Evaluation criteria for intangible cultural heritage projects

Accordingly, we developed an evaluation system for assessing the threatened level of ICH projects based on practitioners and habitats.

Practitioner evaluation criteria

Drawing from the theory of conservation biology in ecology, this study analogizes the inheritors and learners of an ICH project as the adults and juveniles: as the adults gradually decline in number, juveniles mature into adults to replenish the ranks, and these adults subsequently “reproduce” new juveniles. Based on this framework, we developed an evaluation system for inheritors and learners, taking into account their number and structure, age structure, and dynamic changes in number.

The study anticipates that ICH projects classified as critically endangered, endangered, near threatened, and vulnerable will account for 5–10%, 10–20%, 20–30%, and 30–40% of the total, respectively. The range of population sizes for these categories was determined based on the recorded number of inheritors (0–100) across all 706 ICH projects documented in Dali Prefecture, China.

In population ecology, age structure is a crucial factor affecting population continuation. If a population has a larger number of young and juvenile individuals, indicating a pyramid-shaped structure, the population is considered to be in a healthy state (Fig. 1). Therefore, based on population ecology and with regard to the ability to inherit the ICH project, we set the age limits for young individuals as 35 years old and middle-aged as 60 years old. In ecology, the dynamic changes in population numbers reflect the population growth trends, which provide significant guidance for population conservation. Therefore, the dynamic changes in the number of ICH practitioners are one of the main criteria for evaluating the threatened level.

Habitat evaluation criteria

Habitat embodies the foundational milieu for the sustenance and development of ICH. Similar to biodiversity conservation efforts, where monitoring the populations of organisms is essential, habitat considerations are equally important. Likewise, the implementation of living protection strategies for ICH also necessitates the assessment of its habitat. The area of occupancy and its dynamic changes for an ICH project are direct reflections of the habitat’s environmental state. ICH projects occupy areas from the township scale to the national scale, corresponding to the threatened levels that range from Critically Endangered to Least Concern. Considering the actual situation of ICH projects and based on consultation of expert opinions, inheritance and learning mechanism, cultural added value, and conservation funds constitute pivotal elements of their habitats.

Evaluation process

Evaluations should first be conducted separately from the perspectives of ICH practitioners and habitats. After completing evaluations from both perspectives, the higher of the two levels would taken as the final threatened level result.

Application of these categories and criteria

To test the practical application of this evaluation criteria, we stratified randomly selected 100 ICH projects from 11 categories in Dali Prefecture of China for trial evaluation. The material was collected from the Center of Dali Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection through the official application. We conducted the evaluation following the criteria developed by us based on the existing data source of these projects.

At the same time, we also requested three experts with over 10 years of experience to assess the threatened levels of these 100 projects based on their experience. For the Complete Extinct, Functional Extinct, and Data Deficient categories, they referenced the definitions provided in Table 2. For the remaining five threatened levels, they evaluated the likelihood of each project becoming Functionally Extinct within the next 5 to 10 years. The experts assigned the following likelihood categories: unlikely, slightly likely, likely, very likely, and extremely likely, which correspond to Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable, Endangered, and Critically Endangered, respectively. In the first round, the experts were asked to conduct individual assessments using a questionnaire distributed via email. In the second round, we shared the evaluation results with each expert and revisited the projects where there was disagreement among them. This process continued until a consensus was reached through discussion.

We finally compared the results obtained from our criteria and the experts’ experience to judge the applicability of the criteria.

Results

Threatened-level categories of intangible cultural heritage projects

The classification of threatened levels constructed in this paper is divided into three major groups and seven specific categories, ranging from high to low levels of threat: Complete Extinct, Functional Extinct, Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened and Least Concern. And other two categories are: Data Deficient and Not Evaluated, as outlined in Table 2.

Evaluation criteria for intangible cultural heritage projects

The evaluation system for assessing the threatened level of ICH projects, which is based on the perspectives of practitioners and habitats, is outlined below.

Practitioner evaluation criteria

The practitioner evaluation criteria were constructed based on the number and structure (Criterion A), age structure (Criterion B), and dynamic changes in the number (Criterion C) of inheritors and learners (see Table 3). Criterion A evaluates conditions “a. number of inheritors” and “b. number of learners” simultaneously, with the higher threat level between the two being selected as the final result. Additionally, condition ‘c. structure of the number of inheritors/learners’ is considered—if the structure is healthy and reasonable, the threat level is downgraded from the evaluation result of conditions ‘a’ and ‘b.'

Criterion B upgrades the evaluation level based on result of Criterion A, according to the age structure of inheritors and learners. Criterion C, in turn, evaluates the dynamic changes in the number of inheritors and learners, potentially further increasing the threat level as determined by Criteria A and B. While Criteria A and B address the situation of inheritors and learners at a specific point in time, Criterion C reflects their dynamic changes. A detailed explanation of the evaluation process for inheritors/learners is provided in Table 3.

Habitat evaluation criteria

This criteria delineates five principal facets for habitat: area of occupancy (Criterion D), dynamic of survival form (Criterion E), inheritance and learning mechanism (Criterion F), cultural added value (Criterion G), and conservation fund (Criterion H), as shown in Table 4.

The concept of “area of occupancy” (Criterion D) indicates the traditional locations where the ICH project is originated and practiced. Dynamic of survival form (Criterion E) not only highlights the area of occupancy and its fragmentation (Criterion E.a,b), but also encompasses its income modes (Criterion E.c), including innovative sales strategies that impact a larger audience or the expansion of the practice into new regions. For instance, the Chinese Woodblock Printing, recognized as an urgent safeguarding priority on the UNESCO ICH list, can leverage the market reach enabled by e-commerce platforms, such as online sales of DIY products (Fig. 2). In this context, e-commerce represents an expanded dimension of its income modes. Cultural added value (Criterion G), encompassing the social recognition and economic significance of ICH, plays a crucial role in its survival and development, serving as a vital component of its habitat.

The left image represents a traditional area of occupancy, while the right image shows a new income mode, a commodity used as a gift. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of www.ihchina.cn; copyright © 2018 China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network·China Intangible Cultural Heritage Digital Museum, all rights reserved.

In conservation biology, scientists define habitat fragmentation as the process by which a large, continuous area of habitat is divided into smaller, isolated patches, which may increase the extinction risk for a species. In response to habitat fragmentation in biodiversity conservation, we here define the habitat fragmentation of ICH projects as: the number of basic distribution units is less than 3, or the combined area of these basic distribution units is less than 50% of the area of their minimum convex polygon. For example, consider an ICH project distributed within a single county comprising nine township-level basic units: Case A. If the project is present in all nine townships, the habitat is not fragmented (Fig. 3a). Case B. If the project is present in six townships, and the combined area of these six townships exceeds 50% of the area of their minimum convex polygon, the habitat is not fragmented (Fig. 3b). Case C. If the project is present in four townships and the combined area of these four townships is less than 50% of the lined minimum convex polygon area, then the habitat is fragmented (Fig. 3c).

a Habitat is not fragmented, with all basis units occupied (marked with a star); b habitat is not fragmented, and the combined area of occupied units exceeds 50% of lined minimum convex polygon area; c habitat is fragmented, and the combined area of occupied units is less than 50% of lined minimum convex polygon area. Fragmentation is related to the distributed area and distribution pattern of an ICH project. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Na Li; copyright © Na Li, all rights reserved.

When evaluating habitat conditions, the assessment begins with Criterion D to assign an initial threat level based on the following five conditions. Subsequently, adjustments to this level are systematically applied using Criteria E through H, following a nuanced and layered refinement approach, as outlined in Table 4.

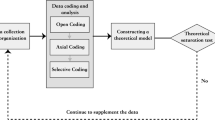

Evaluation process

When conducting assessments of intangible cultural heritage (ICH), evaluations are carried out separately from the perspectives of practitioners and habitats, following the specified order outlined in evaluation forms (Table 3 and Table 4, as previously outlined). After completing assessments from both perspectives, the higher of the two identified threat levels is selected as the final result for this evaluation system, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Additionally, the evaluation results can be effectively integrated with existing national classification systems. For instance, the classification of ICH projects within the national system can be combined with the evaluation results of our system, ultimately forming comprehensive assessment outcomes. For example, when aligning with China’s Four-Tier list system, ICH projects could be classified as ‘National Endangered’ or ‘Provincial Vulnerable’ based on the evaluation results.

Application of this categories and criteria: 100 ICH projects in Dali as case

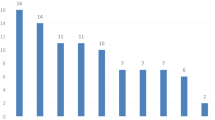

The evaluation results derived from both this criteria and the experts of each ICH project are present in Table 5. Detailed information regarding the basis for these results is provided in Supplementary Information Appendix I. The findings demonstrate a high level of consistency, with 92 out of 100 projects receiving identical ratings according to both the evaluation criteria and expert assessments, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. This consistency validates the accuracy and reliability of our evaluation system in determining the threatened levels of ICH. Discrepancies between the framework’s assessments and expert opinions were primarily observed in the categories of traditional music, drama, and handcrafts, with differences of one or two levels noted in these cases, as summarized in Table 5. To further explore the relationship between ICH and environmental and biodiversity factors, we also categorized these 100 projects according to UNESCO (2003) Convention (Fig. 5b). Notably, projects categorized under “Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe” exhibited a higher degree of inconsistency between expert opinions and our evaluation criteria. This finding underscores the need for further refinement of our criteria to better protect these ICH elements in the context of rapidly changing environmental and biodiversity landscapes.

a Category of Chinese national legislation; b Category of the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003, UNECOS. Blue-The evaluation results are consistent between the criteria and experts, Yellow-The evaluation results are inconsistent between the criteria and experts. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of Na Li; copyright © Na Li, all rights reserved.

According to the evaluation criteria, the 100 projects were distributed across different threatened levels as follows: 62 projects were classified as Critically Endangered, 11 as Endangered, 5 as Near Threatened, 11 as Vulnerable, 1 as Least Concern, and 10 as Data Deficient. These results suggest that ICH projects facing higher levels of threat are more likely to be documented and recognized, highlighting the importance of our evaluation system in identifying and prioritizing ICH for conservation efforts.

Discussion and outlook

Although extensive research has been conducted on the protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) and several evaluation criteria have been established, existing frameworks exhibit notable limitations. First, many of these criteria are narrowly focused on specific ICH categories, failing to achieve universality (Xie, 2017). Second, they often list indicators without providing operational procedures, limiting their practical application (Qiu, 2018). Third, the evaluation process is frequently overly complex, making implementation difficult (Yang and Lu, 2019). In contrast, the criteria established in this study, grounded in the perspective of cultural ecology, demonstrate robust applicability across most ICH projects. Not only are they easy to comprehend and utilize, but preliminary trials have also yielded promising results, underscoring their potential for broad dissemination and application. Furthermore, it is essential to emphasize the importance of refining these criteria through continuous monitoring of ICH projects, thereby fostering advancements in ICH protection efforts and enhancing their effectiveness.

Operability and applicability

In the field of social sciences, the importance of interdisciplinary thinking in the protection of ICH has long been recognized (UNESCO, 2003; Zhao, 2009). Cultural ecology is an interdisciplinary field that uses ecology as a template to study cultural issues. Our evaluation system is rooted in this cultural-ecological perspective, integrating ecological theories and methodologies to assess ICH. By drawing inspiration from the established IUCN criteria for evaluating the endangerment levels of species in biodiversity conservation, we have developed a quantitative approach that examines ICH projects from both the perspectives of practitioners and their habitats, accounting for their dynamic changes.

The application of our criteria to a randomly selected sample of 100 ICH projects in Dali Prefecture resulted in high consistency with expert judgments, indicating that this evaluation system is suitable for different categories of ICH projects. Many ICH projects lack information, such as data on general inheritors, learners, and habitat-related information. Despite these limitations, our evaluation system achieved over 90% agreement with expert judgments. This robust performance can be attributed to the system’s dual focus on both practitioners and habitats, prioritizing the higher threatened evaluation level as the final assessment. This approach provides a clear, practical, and adaptable operational framework suited to real-world challenges. Even in scenarios with limited data availability, our evaluation criteria maintain a high level of accuracy, underscoring its excellent usability, scientific rigor, and broad applicability.

Future improvement

During the trial evaluation of 100 ICH projects in Dali Prefecture, we found that the information of the inheritors was relatively complete, while the habitat information was seriously insufficient. Although some ICH projects are evaluated as having a high threatened level from the perspective of practitioners, the situation is not as dangerous as it seems, such as the cooking skills of sour and spicy fish, chess, etc. However, despite having a large number of inheritors, the habitat conditions for some ICH projects, such as the Bai ethnic group’s Dabenqu and Erzi songs, are not optimistic. It is necessary to pay timely attention to these situations and supplement habitat materials through monitoring. This indicates the urgency of applying this evaluation system to carry out ICH monitoring and protection.

The establishment and improvement of the ICH threatened-level categories and criteria and the monitoring of ICH projects are closely interconnected. Monitoring requires guidance from the criteria, while the refinement of the evaluation system depends on systematic monitoring results. Drawing parallels to the development of the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria in biodiversity conservation, which began with simple and easily accepted classification criteria, it underwent a iterative process of “criteria setting—application—refinement—application” to achieve comprehensive effectiveness (Jiang and Fan, 2003). Even though the current version still has shortcomings, it remains vital in biodiversity conservation (Jiang and Luo, 2012; Jiang et al., 2016). Similarly, we should not expect a flawless ICH threatened-level evaluation criteria from the outset. Avoiding a deadlock of “which came first, the chicken or the egg,” we should initiate with the criteria, select ICH projects for targeted monitoring, and use feedback from experts to optimize and enhance the criteria continuously.

In conclusion, these criteria align with UNESCO’s principles of integrity and living protection in ICH conservation, aiming to safeguard both the culture itself and its essential habitats. It emphasizes the culture’s historical roots and its present and future development. The proposed criteria serve as a valuable supplement to ICH conservation efforts, reflecting China’s leadership in cultural ecology reserves. It contributes to enhancing national cultural power and offers significant insights for global cultural heritage protection.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Bingkui Q (2018) Evaluation system for the overall protection effect of intangible cultural heritage [J]. J Jinzhong Univ 35(04):29–32

Chao D, Wei S (2017) Thoughts on Improving the Protection Policy of Intangible Cultural Heritage [J]. J South-Cent Univ Nationalities (Humant Soc Sci) 37(06):62–67

Chongqiao X (2017) Definition and classification of endangered traditional handcrafts[J]. Natl Arts 06:67–74

Fang X, Shi-shan Z, Jun-hua S, Zhi-yao M (2023) Ten question on the protection of intangible cultural heritage[J]. J Ethn Cult 15(01):1–15 + 153

Huang Y, Qian J (2016) The Dilemma and way out of the system for identifying inheritors of intangible cultural heritage in China [J]. J Guangxi Univ (Philos Soc Sci Ed) 38(03):51–57

IUCN (2012) IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. Second edition. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge. iv + 32pp

Jiang Z, Li L, Luo Z et al. (2016) Evaluating the status of China’s mammals and analyzing their causes of endangerment through the red list assessment[J]. Biodivers Sci 24(05):552–571

Julian S (1955) Theory of culture change: the methodology of multilinear evolution [M]. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Kui-li L (2007) On issues concerning culturally ecological reserves[J]. J Zhejiang Norm Univ(Soc Sci) 03:9–12

Li Y, Jun G (2009) Studies on intangible cultural heritage [M]. Higher Education Press, Beijing, pp. 19–21

Li-guo Y, Nai L (2019) Study on assessment of intangible cultural heritage living level—taking Jiangsu province as an example[J]. Resour Dev Mark 35(12):1525–1531

Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China (2018) Management measures for national cultural ecology protection experimental zones [EB/OL]. Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China

Nsamenang AB (2015) Ecocultural theories of development. Int Encycl Soc Behav Sci 6(2):838–844

Piccardo C, Canepa M (2020) Cultural ecology: paradigm for a sustainable man-nature relationship. Partnerships for the goals. Springer. pp. 1–11

UNESCO (2003) Text of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage[EB/OL]. https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

Wain A (2014) Conservation of the intangible: a continuing challenge [J]. AICCM Bull 35(1):52–59

Yanxi Z (2009) On the concept of integrity protection of intangible cultural heritage[J]. Guizhou Ethn Stud 6:49–53

Zhigang J, Zhenhua L (2012) Assessing species endangerment status: progress in research and an example from China[J]. Biodivers Sci 20(5):11

Zhi-gang J, En-yuan FAN (2003) Exploring the endangered species criteria: rethinking the IUCN Red List Criteria [J]. Biodivers Sci 11(5):10

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (Grant No. 2019QZKK0402) and Research on the Integrated Development of Ethnic Minority Culture and Eco-tourism in Northwest Yunnan Province, China (Grant No. SYSX202025). And thanks to Prof. Xuelong Li, Xiangjun Zhao, Jun Yang and Yunxia Zhang for their involvement in assessing the threat levels of the 100 IHC projects. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to the students from the Institute of National Culture Research at Dali University for their assistance in organizing data for the ICH projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Na Li: conceptualization, methodology, interpretation of data, writing-original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; Xiaokang Li: software, data curation, analysis of data, writing-original draft preparation; Wen Xiao: conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Li, X. & Xiao, W. Intangible cultural heritage threatened-level categories and criteria. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 271 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04595-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04595-4