Abstract

Calls for democratising technology are pervasive in current technological discourse. Indeed, participating publics have been mobilised as a core normative aspiration in Science and Technology Studies (STS), driven by a critical examination of “expertise”. In a sense, democratic deliberation became the answer to the question of responsible technological governance, and science and technology communication. On the other hand, calls for technifying democracy are ever more pervasive in deliberative democracy’s discourse. Many new digital tools (“civic technologies”) are shaping democratic practice while navigating a complex political economy. Moreover, Natural Language Processing and AI are providing novel alternatives for systematising large-scale participation, automated moderation and setting up participation. In a sense, emerging digital technologies became the answer to the question of how to augment collective intelligence and reconnect deliberation to mass politics. In this paper, I explore the mutual shaping of (deliberative) democracy and technology (studies), highlighting that without careful consideration, both disciplines risk being reduced to superficial symbols in discourses inclined towards quick solutionism. This analysis highlights the current disconnect between Deliberative Democracy and STS, exploring the potential benefits of fostering closer links between the two fields. Drawing on STS insights, the paper argues that deliberative democracy could be enriched by a deeper engagement with the material aspects of democratic processes, the evolving nature of civic technologies through use, and a more critical approach to expertise. It also suggests that STS scholars would benefit from engaging more closely with democratic theory, which could enhance their analysis of public participation, bridge the gap between descriptive richness and normative relevance, and offer a more nuanced understanding of the inner functioning of political systems and politics in contemporary democracies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Is technology the answer to the questions of democratic deliberation? Or is democratic deliberation the answer to the questions of technology? In other words, which is the question, and which is the answer? This article explores how this interplay of questions and answers is unfolding within the academic fields that take the social study of technology and democratic deliberation as their central concern, namely, Deliberative Democracy and Science and Technology Studies (STS). Specifically, it examines the parallel framings emerging in these fields, where in Deliberative Democracy, citizen participation is framed as the question to which technology provides the answer, while in STS, technology itself is framed as the question to which citizen participation offers the answer. In doing so, the article aims to highlight the weakened state of interdisciplinary dialogue between these two fields, which does, in some instances, lend itself to technological or participatory solutionism.

There are many ways to frame the apparent tension between technologising democracy and democratising technology. As Levidow (1998) argues, it all depends on how we conceptualise what “technology” and “democracy” are. For many technologists, democratising technology just means making gadgets widely available, and in that sense, technological innovation almost always democratises (Ford, 2021). For others, this tension is best described as an interplay of expertise and institutional decision-making requiring political legitimacy (Bader, 2014). Overall, the concept of “democratisation of technology” is often used in conflicting ways, from widespread usage, collaborative development, sharing profits or democratic governance (Seger et al. 2023).

Others would simply reject that such tension even exists, either subsuming science and technology to democracy or vice versa. For example, famed sociologist of science Robert K. Merton in his 1942 essay “A Note on Science and Technology in a Democratic Order” fundamentally asserted that science and technology despite being autonomous, operate organisationally as a democracy –although he would later point out a tension between “appropriate” and “legitimate” political action that differentiates democracies from expertise (Merton, 1966). Conversely, Bruno Latour famously claimed that “science is politics by other means” (Latour, 1988), and since then, most technology studies have been based on the idea that innovation has displaced politics (Nahuis and van Lente, 2008). More recently, with the advent of digital democracy narratives, both technology and democracy are seen as deeply intertwined (Ford, 2021).

For this article, I take a narrower approach and interrogate the relationship between citizen deliberation and technology, with a special focus on how this relationship is enacted within the specialised academic communities of Deliberative Democracy and Science and Technology Studies.

Briefly put, Deliberative Democracy is a field of study that combines a theoretical foundation rooted in political theory, focusing on reason-giving and communication, with an empirical investigation into how political forums—at both micro and macro levels—enable such communication in an inclusive, authentic and consequential manner (Dryzek, 2009a; Bächtiger and Parkinson, 2019; Curato et al. 2020). As the term suggests, this field emphasises deliberation as the core object of study, understood as decision-making based on reason-giving, critical questioning, and mutual listening (Bächtiger and Dryzek, 2024) –although even the centrality of the practice of deliberation is itself contested within the field (Scudder, 2023).

There are significant overlaps, but also important distinctions, between Deliberative Democracy and related concepts such as Participatory Democracy and Democratic Innovations (Lafont, 2019; Asenbaum, 2021; Veri, 2023). In this article, I focus on Deliberative Democracy as the primary framework, because Democratic Innovations often centre on “processes or institutions” (Elstub and Escobar, 2019a) whereas this discussion is more concerned with the conceptual level. Moreover, within contemporary Deliberative Democracy as a diverse conceptual landscape there are many researchers increasingly integrating insights from participatory models of democracy (Palumbo, 2024), fostering a complementary relationship where “participation and deliberation go together” (Curato et al. 2017).

An equally diverse conceptual landscape, STS is an interdisciplinary field that centres on the co-production of science and technology, on the one hand, and society, on the other (Sismondo, 2010; Felt and Irwin, 2024). It involves both the theoretical and empirical study of the mutual shaping of technology and social life as inseparable and intertwined dimensions (Felt and Irwin, 2024). In STS, technology is examined as much more than mere “things,” focusing instead on technology as complex cultural processes that intersect material features with symbolic and discursive dimensions—what is referred to as the technology as culture frame (Magaudda, 2024). This approach rejects the dominant model of technological determinism, in which artefacts are depicted as autonomous entities that unidirectionally impact society (Williams and Edge, 1996). In this sense, I centre my discussion on STS due to its more holistic understanding of technology and society as co-produced and mutually shaping, thereby highlighting the role of politics and democracy as a crucial category in this analysis.

An important caveat to keep in mind is that there are relevant theoretical differences between the uses of concepts such as “technology” or “democracy”. For once, STS has developed many different social theories regarding what technology is and its role in society, which will not be explored in this discussion –for a classical overview see Bijker, Hughes and Pinch (1989). Moreover, deliberation in the sense of Deliberative Democracy can be seen as conceptually distinct from public participation as STS scholars use it, yet most relate to the overall idea of “talk-centric” (Chambers, 2003) citizen-led governance. The main two-way communication practices that fall beyond that description are citizen science processes, or broadly speaking, practices that fall under what Einsiedel (2014) calls knowledge production formats.

Building on these theoretical distinctions, it is also worth noting that there are significant epistemological affinities between the two fields. Both Deliberative Democracy and STS adopt an interpretive outlook, resisting the assumption of the legitimacy of political or knowledge domains a priori (Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2023c). However, their approaches diverge in emphasis. Deliberative Democracy is explicitly grounded in normative theory, prioritising ideals such as fairness, justice, and equality to assess and guide democratic practices (Chambers, 2024). In contrast, STS tends to maintain a symmetrical approach, methodologically avoiding predetermined judgments about the correctness of postulates being explained (Lynch, 2017). Instead, as Soneryd and Sundqvist (2023) describe, STS often develops a “shadow theory” that foregrounds the hidden complexities and contradictions underlying socio-technical systems and knowledge practices.

The spirit of this discussion is not to dilute the rich nuances and conceptual differences between the two fields’ use of technology and democracy. Rather, I claim that despite those differences, both fields, in a very profound way, mirror each other in a game of “questions and answers”. To explore this, I will discuss below how technology is playing an increasingly critical role within deliberative democracy. Later, I will discuss how public participation has been used within STS as a core piece in larger puzzles around expertise and normativity. Finally, I present an integrated description of the parallel between the two sections and the risks this presents to both Deliberative Democracy and STS, focusing on what both fields could gain from more engaged interdisciplinary dialogue.

Technology in deliberative democracy

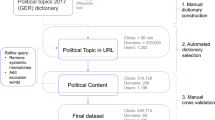

Technology has always been part of political systems (Braun and Whatmore, 2010). In ancient Greece, marked pebbles (psephos) or pottery shards (ostraka) were used as voting tokens to protect secrecy and coordinate citizens. The Kleroterion (see Fig. 1), a randomisation machine, was used to select citizens to serve in political roles for the Polis. Candidate citizens from every tribe could insert their tokens and a secretive mechanism then allocate a random column to the available slots.

The invention of the printing press reshaped the arena of political communication and political debate. Even that breakthrough depended on previous technology of paper and ink manufacturing, and typesetting, among others. This observation made by Habermas (1991) was fundamental in his understanding of the public sphere. Contemporary deliberative mini-publics (randomly selected groups of citizens deliberating on public issues –arguably the modern equivalent to the Athenian format) depend on technology as well. More sophisticated technologies of sortition and voting, slideshow tools, and amplification, just to name a few, but technologies nonetheless.

However, when the notion of technology is mobilised within political discourse it is usually to refer to a specific kind of technology, namely, emerging digital tools. As Vinsel and Russell (2020) assert, the digital has dominated (and restricted) our collective imaginaries of technologies. Democratic theory has not been an exception to this capture (Bernholz et al. 2021).

There are different ways in which digital technologies have shaped democratic practices, and more specifically, the application of deliberative democracy. Digital participation has permeated and hybridised almost all types of democratic innovations (Elstub and Escobar, 2019a). Internet technology has allowed for video calls to support distributed citizen engagement, or the development of dedicated websites and apps to aggregate citizen ideas, opinions, and votes.

It is now common to refer to these digital tools as “civic technologies” or civic techs for short. The constitution of the field of civic tech is inexorably linked to the dynamics of commodification of participation software and the prospects of profitable (or social) investment (Saldivar et al. 2019; Russon Gilman and Carneiro Peixoto, 2019; Wadekar et al. 2020). In fact, the very origin of the term “civic technology” can be traced back to a 2013 report by the Knight Foundation on social investing opportunities (Patel et al. 2013).

Civic techs can take many forms, but they are usually thought of as online platforms used by convenors to organise and set up deliberation, coproduction or crowdsourcing. These digital tools not only afford and restrict certain behaviours but also drive framings and imaginaries of democracy. Particularly, what has emerged from this technological diffusion is a sort of “platformisation” of participation (Robinson and Johnson, 2023). Civic techs also distribute power and attention. For instance, their design tends to emphasise user experience within deliberation more than how deliberation is translated politically into institutional action (Mellon et al. 2022).

These tools also construct a political economy as they are mostly paid for and usually purchased with public funding via contracts with the administrative state (Robinson and Johnson, 2023). Software may be sold under the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) scheme, or software itself may be freely distributed but consultancy advice charged. Moreover, private companies can charge services to institutions and use open-sourced tools to deliver them. Institutional clients can, nonetheless, resent civic technologies drawing too much from the business innovation model or being too ‘business-y’ (Boehner and DiSalvo, 2016).

Simultaneously, several civic tech initiatives have sought to resist commodification and embrace a “commons” approach through open-sourced designs or Creative Commons licencing. Many authors see civic technology as a critical component of digital activism and not a for-profit endeavour (Justice et al. 2018). In fact, many well-known civic techs originate from social movements worldwide (Peixoto and Sifry, 2017; Russon Gilman and Carneiro Peixoto, 2019).

However, many of these open-source civic technologies just end up stagnating in online repositories (Cibrario and Mejia, 2023). In part, this can be explained by the fact that civic tools are often fragmented instead of interconnected (Gastil and Richards, 2017). But also, as Science and Technology scholars have extensively shown, scientific and technological adoption depends greatly on actors’ rhetorical capacity to convince others (Sismondo, 2010). On the one hand, most non-profit organisations presumably have less marketing and public relations muscle to get their products “out there”. On the other hand, open-sourced civic techs typically demand more efforts from Governments to upkeep and update the software on their own (Shaw, 2018; Russon Gilman and Carneiro Peixoto, 2019).

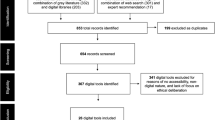

Critically, one must understand that open-sourced digital tools are mainly hosted in highly technical code repositories, such as Github. In that sense, the expectation that they can be easily used by communities and organisations seems taxing. In practice, that requires them to either have strong IT skills in-house or that they hire a private company to set it up. Figure 2 depicts what a person would encounter by trying to install an open-sourced civic tech—in this case, Decidim. Because of this, new platforms are being created to offer easy-to-use graphic user interfaces and hosting for already existing open-source tech. For instance, Decidim forms alliances with “official partners” that can help install and run—and charge for—mini-publics based on their open-source tech. An example of this sort of secondary civic tech at the time of writing is Voca.City.

Recovered from https://github.com/decidim/decidim.

Despite the abundance of actors and tools, there are pressures for market consolidation. As the CEO of the civic tech company, Fluicity argues “There are a lot of competitors, but I would say that there are only a few mature competitors that have enough investment capacity to play internationally. […] I foresee that consolidation of the market will come soon.” (quoted in García, Idea (2023)). In a way, the excessive production of slightly different open-source alternatives helps sustain the “tragedy of the digital commons” (Greco and Floridi, 2004), in which individual actions just saturate the infosphere. Deliberative democrats, in that sense, should keep in mind that commons designs can turn meaningless unless commonly used.

Beyond the commodification of digital technology by civic tech companies or non-profits, interesting developments are taking place within social computational analysis for democratic innovations. Specifically, the area of computational analysis often called “Natural Language Processing” (NLP) has been fundamental for the development of digital tools for citizen engagement, especially in the space of analysis and analytics. According to Romberg & Escher (2023), NLP tools used for analysing citizen engagement can be organised into three main categories.

-

Grouping Data Collection by Topic or pre-defined concepts

In Topic Modelling, there are two primary methods for categorising citizen contributions by topic. In supervised machine learning, the model predicts predefined topic labels for data points using labelled training data. Conversely, unsupervised machine learning identifies latent topics in the data, forming clusters of thematically similar contributions without requiring training data. Other approaches, for instance, Dictionary-based techniques allow matching words to pre-defined criteria. For instance, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) predefines a set of words that relate to specific cognitive and relational processes (Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010).

-

Identifying and re-constructing citizens’ arguments

Recent developments in the field of Argument Mining show promise in the automated filtering of texts to identify the sentences that have argumentative content (sentences that express a standpoint and justifications of that position). Moreover, there have also been successful attempts to automatically classify those sentences as against or for a specific political statement (Schaefer and Stede, 2021). This would allow us to reconstruct entire deliberation transcripts as arguments for and against controversial statements.

-

Identifying attitudes and emotions towards topics

Sentiment analysis, also called Opinion Mining, is a collection of computational tools that help detect and categorise attitudes toward a specific topic. Generally, these classifiers label citizen statements on a one-dimensional scale from negative to positive (polarity). However, other studies not covered in Romberg & Escher’s (2023) review, typically add intensity as another factor (Tian et al. 2018), that allows for more nuanced emotion labelling.

Building upon these computational techniques, democratic support software often provides at least some basic form of categorisation and/or topic that helps stakeholders have a sense of what was discussed. Beyond that, other more nuanced uses include the assessment of deliberative quality (Falk and Lapesa, 2023; Goddard and Gillespie, 2023), or to identify intensity and sources of political polarisation (Németh, 2023). However, most deliberation-specific applications are quite recent and require more testing before widespread diffusion.

Looked at from a more conceptual standpoint, there are at least two main justification themes that explain the increasing symbolic capital of digital technologies for democratic engagement. As I will expand below, one of these themes focuses on the epistemic benefits of technology, and the other on the normative potential of technology to reunite deliberation and mass politics.

The first line of argumentation lies within the epistemic tradition of deliberative democracy. Briefly put, for epistemic democrats, emerging digital technology works as a proxy for “augmenting our intelligence”(Martí, 2021). The connection between the “collective intelligence” approach to democracy and emerging digital tools is almost ontological, as most of these tools are equally predicated on the power of volume and heterogeneity of information (Noveck, 2018). Moreover, for Collective Intelligence scholars, digital information technology and participatory democracy both serve the purpose of enacting and expanding collective consciousness (Hallin, 2023). Public institutions have drawn from the collective intelligence approach to fund initiatives that promise to enhance collective decision-making, collaboration and connecting voices (Grobbink and Peach, 2020).

The second line of argumentation relates to the normative core of deliberative democracy. For some deliberative democrats, digital technologies promise to close the gap between careful deliberation and mass participation (Landemore, 2024). Especially after the so-called systemic turn in deliberative democracy research (Mansbridge et al. 2012), there is renewed attention to the interplays of democratic innovations and the wider political system. In parallel, Cristina Lafont’s (2020) recent critique of the assumption that the public sphere ought to blindly defer to the conclusions of mini-publics has strengthened the need to better articulate how deliberation can integrate with the whole of democracy, or at least to “scale up” its capacity for discursive regulation (Niemeyer and Jennstal, 2018). Of course, this criticism is not new and can be traced to Simone Chambers’s (2009) provocative question: “Has deliberative democracy abandoned mass democracy?”

For democratic innovations to become closer to mass participation, the normative values of deliberation, for instance, authenticity, inclusivity and consequentiality (Dryzek, 2009), along with the extensive expertise of participation designers and facilitators would have to scale up as well. This goes back to deliberative democracy’s rejection of pure aggregation of opinions and to Habermas’s (1998) idea of informed public opinion as the preferences people “would express after weighting the relevant information and arguments” (p.336).

In that sense, technologies that just aggregate ideas (e.g. crowdsourcing tech) would hardly meet these criteria. But surfing the hype of new AI developments, scholars have explored the potential of LLMs (Large Language Models) to automatise some of the normative requirements of deliberation. For instance, AI has been used to automatise facilitation as a means to address power inequalities within groups (Kim et al. 2021; Mikhaylovskaya, 2024), and translation and real-time interpretation as a means of inclusion (Ovadya, 2023).

The use of AI to “augment” deliberative democracy is not without its critics. As Nardine Alnemr (2020) points out, without proper deliberation, the deployment of these technologies forces citizens to passively accept the role of digital technologies and democracy and the parameters set by their expert designers. Moreover, in the case of automated moderators, it removes participants’ right to engage in mutual justification as algorithms cannot, in a meaningful way, justify their decision-making.

In fact, after the widespread diffusion of technology ethics concepts, such as algorithmic bias and the black box problem, as well as in line with worldwide widespread concerns about the new generation of large language models (LLMs), technology has increasingly been problematised in deliberative democracy. There is a sense in which democracy is now the answer to the problems of technologies within the field of deliberative democracy (Ovadya, 2023; Yang and Roberts, 2023). This is best exemplified by recent calls to conduct Global Assemblies or more local Alignment Assemblies to reimagine AI governance.

In sum, there is an intricate historically constructed relationship between technology and deliberation to be unpacked. Technology is not a new guest of democracy, but a constitutional pillar since its very foundation. The emergence of technological imaginaries centred around the digital (and its hype) has indeed had an impact on the practices and discourse of deliberative democracy. On the one hand, technological developments in NLP and AI have opened up new possibilities for analysing and scaffolding deliberation. On the other hand, we are witnessing their constitution as “civic techs” as part of a wider confrontation between commodified and common political economy.

In all cases, digital technology is seen as a promising solution to articulate some of the fundamental challenges of deliberative theory. Namely, bringing forth “collective intelligence” to achieve the epistemic objectives of citizen deliberation, and re-aligning deliberation and mass participation by scaling up some of the discursive features of good deliberative settings. In other words, technology has become an answer to the question of deliberation, without a more profound examination of the impact of the “technoscientification” of democracy (Voß and Amelung, 2016).

Citizen Participation in Science and Technology Studies

Public participation has been a central theme in STS from its inception, and it continues to be a major topic in contemporary research (Kearnes and Chilvers, 2024; Macnaghten, 2024). However, a closer look at its specific uses shows that typically, the notion of participation has been mostly used to support larger debates of mainstream STS literature, rather than as a topic of discussion in itself. In that sense, it has operated as an answer to the question of technoscience—the progressive interconnectedness of science and technology (Davies, 2024).

On the one hand, participating publics have served as a paradigmatic point of view in the deconstruction of expertise. Case studies such as Wynne’s (1992) research on sheep farmers in Cumbria and Epstein’s (1995) account of AIDS political activists in the 1980s (see Fig. 3) have had a significant impact on STS. Wynne’s (1992) case study highlights the nuanced understanding sheep farmers had of the effects of radiation in the soil, with some even predicting the ineffectiveness of certain government experiments. Epstein (1995) documented how AIDS activists posed systematic challenges to established medical experts, ultimately reshaping medical guidelines. Both cases contributed to STS by reinforcing the idea that fixed boundaries between lay citizens and experts are problematic. This has been widely interpreted as evidence that lay citizens can offer valuable insights, and that excluding them from decision-making poses an epistemic risk.

One of the organisations documented by Steven Epstein’s (1995) influential work.

In a slight counter-move, Collins and Evans’s (2002) “third wave” Programme, as it has come to be known, questioned the degree to which STS (by then) recent efforts to bring out lay expertise have rendered the role of expertise in society meaningless. In that vein, they asked the question of whether there should be a limit to public participation in technoscientific affairs. This is what they call the “problem of extension”.

According to Collins and Evans (2007), it is true that lay citizens can produce relevant tacit knowledge, and they can even be socialised into the language of scientific expertise (such as the AIDS activists or Collins himself in physics and gravitational waves), however, this “interactional expertise” would still be different to the kind of contributory expertise produced by the specialists. It must be noted that Wynne (2003) argued that his work was not meant to be understood as concerned with the exclusion of “people with authentic but unrecognized expertise” (p.402) to the arena of expert deliberation about propositional truths. Rather, he was making the substantive claim that as lay citizens and experts share different forms of life, their ways of knowing cannot easily, if at all, be reduced into a unified language and practice. Thus, making the legitimacy of science a complicated endeavour. Hence, public participation is not thematised as a thing in itself, but as a piece in the puzzle of the ontology of scientific expertise.

On the other hand, public participation has served as part of the overall STS normative understanding of knowledge-making. The sociological observation underlying this perspective is that scientists and engineers are, in practice, also policymakers, insofar as they find themselves in the policy room many times, in advisory roles, as science communicators or managers (Pielke (2007); Miller and Neff, 2013). In this sense, there is a political dimension to scientists and engineers that begs the question of legitimacy, especially when lay citizens are excluded from the decision-making sphere to which experts do indeed get an invitation. However, more broadly the theoretical argument is that the scientific, the governmental and the publics are co-produced (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2020), and thus, participation is a constitutional system of both technoscience and democracy (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2020).

From this co-production theoretical standpoint, also derive normative expectations for public participation in technoscientific governance and science policy. Citizen views are seen as invaluable for completing the picture of anticipating the socio-political consequences and implications of new science and technology. As Jasanoff (2016) puts it, the practice of anticipation “offers an opportunity for citizens to work together with scientists, engineers, and public officials to envision more inclusive technological futures” (p.238). Others, inspired by participatory literature, such as the famous—and often criticised—Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of participation have called for more pervasive public participation, in upstream technological development (Bauer et al. 2021) and the science-making process itself (i.e., citizen science; (Strasser et al. 2018). This can clearly be observed in the STS-driven Responsible Research and Innovation movement that has called for more upstream public deliberation and participation as one of its four constitutional values (Owen et al. 2013). More recently, this baton of public participation has been taken up by the renewed institutional interest in Open Science/Open Research that focuses on wider collaboration with communities (European Commission – Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, 2021; UNESCO, 2022).

In this sense, participation plays a key role as a normative expectation derived from a co-productionist standpoint of science policy and technology governance. Under this perspective, it simply is not fair that scientists and experts communicate “top-down” (Trench, 2008) to citizens issues that, because of their political and cultural nature, they are entitled to discuss and shape. Moreover, these are issues that without their voice, any risk assessment would be, at the very least, incomplete (Jasanoff, 2016). This is what I would call a deontological argument for participation, which is often present after the “normative turn” in STS (Lynch and Cole, 2005). By deontological, I mean arguments that take the form of institutional duty or obligation to invite citizens.

Public participation has also played a normative role in discussions of science communication. STS scholars were critical of the 1960 to 1990 prominent scientific literacy movement that reproduced a “deficit model” (Sturgis and Allum, 2004) of the public that framed them as lacking the relevant information to engage meaningfully in the sociotechnical dimensions of society. Against this background, STS scholars called for two-way communication between experts and the public under the motto of “deficit to dialogue” (Irwin, 2014; Stilgoe et al. 2014). In turn, this movement towards participation led to a reframing of science communication from ideas of Public Understanding of Science (PUS), to Public Engagement with Science and Technology (PEST).

More recently, STS scholars have also positioned themselves and public participation in the ever more present “crisis of expertise” (Eyal, 2019) that creates tension in modern democracies. According to Eyal (2019), the crisis of expertise is double, on the one hand, technical experts have lost the public confidence as the main decision-makers (which some colloquially name a post-truth society), and, on the other hand, we live in an increasingly technified and expert society that permeates all spheres of life. Even STS’ role in bringing about this crisis is still largely debated (Sismondo, 2017; Collins et al. 2017).

In this context of crisis, STS scholars have suggested the importance of more engagement for reconstructing trust (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2020; Stilgoe et al., 2014), while other STS scholars have suggested reinvigorating the role of experts. For instance, Collins et al. (2022) advocate for a model of democracy in which citizens, governments and bodies of experts are only one of the many institutions, mutually regulating, but with differentiated responsibilities and roles in complex societies. Under that model, the boundaries of expertise ought to be defended, as they play a critical part in democratic checks and balances. This is what they call “structured choice democracy”, which is presented as an alternative to both populism and technocracy, which are perceived to have produced this crisis.

In sum, it seems that public participation has played an auxiliary role in much larger debates in STS. When participation is mobilised within STS, I assert these can be understood in two main justification themes; the expansion of the ontology of expertise and the need to politicise the technical.

The first relates to the ontology of expertise. Once the role of experts as bearers of objective knowledge with a view-from-nowhere is challenged and the contingencies of their practice brought to the forefront (Laurent, 2023), it seems almost natural to seek to expand or flexibilise the boundaries of “who” gets to be an expert. This can be linked with increasing attention to “lay expertise” (Akrich and Rabeharisoa, 2023; Epstein, 2023), but also with broader calls used by participation practitioners that citizens are experts in their own experience (Krick and Meriluoto, 2022; Krick, 2022).

The second relates to the rejection of technocratic governance and the challenge of value-free technical practice (Beck, 2011; Beck and Forsyth, 2020). Once the ability of technoscience to solve political conflict and even the boundaries of the two are challenged (Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2023), public participation can seem like an attractive tool to re-socialise and re-politicise the technical by bringing value contestation to the forefront. This idea is applied both to technological policy (Lynch, 2014) and the production of technology itself (Stilgoe et al. 2014). As Beck and Forsyth (2020) put it, participating publics are mobilised in conjunction with the question “Whose values and visions count”? (p. 220).

All and all, it seems that participation has been thematised in STS mostly not as a topic in itself, but as a piece in bigger puzzles relating to expertise, and the interface of science and technology with policy and democratic politics (Eyal & Medvetz, 2023). Moreover, STS scholars often find themselves in the tricky position between promoting extensive participation in science and technology and critically examining its practices (Douglas-Jones, 2022; Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2022). Perhaps because of this, not enough attention has been placed in the pursuit of theorising participation itself, rather than being seen as an auxiliary concept with a conceptual function in explaining expertise, or legitimacy. This relates to what Horst and Davies (2021) call a shift from an instrumentalist view of public communication (what it is for) to a cultural view (what it is).

Emerging STS literature has indeed taken more seriously a substantive analysis of participation and democracy. STS, as a field, holds a privileged position to critically explore how democracy and the technosciences are co-produced (Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2023), and how interfaces and infrastructures operate within ‘technodemocracies’ (Birkbak and Papazu, 2022). Recent calls for “remaking” participation as reflective practices that operate ecologically, contingently and that require responsibility (Chilvers and Kearnes, 2020) move in this direction.

Among other developments, there has been growing interest within STS in framing participation as a form of technology in its own right. In this context, participation can be understood as a technology insofar as deliberative events are best described as highly artificial and orchestrated spaces, designed by trained participation experts to foster specific forms of communication (Macnaghten, 2024). This perspective also brings attention to the entanglement of material and political processes in how various participatory spaces contribute to the infrastructuring of what it means to be a citizen (Felt and Sepehr, 2024). Consequently, this view has led STS to focus more on the diverse technologies of participation that form complex ecologies, rather than fixating on any single type of deliberative engagement technology (Kearnes and Chilvers, 2024). This view differs from that of contemporary Deliberative Democracy, as it challenges the very division between participation and technology as separate domains.

However, for these more nuanced perspectives to flourish, the field must first decisively move away from an instrumental use of participation as a technology of legitimation (Harrison and Mort, 1998). In other words, participation has become an answer to the normative questions of technoscience without a more profound theory of democracy in itself (Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2023).

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, I engaged in a twofold conceptual exploration. On the one hand, I explored how technology is mobilised in the practice and theory of the field of Deliberative Democracy. On the other hand, I discussed the role that citizen participation has played in the field of Science and Technology Studies. The purpose of that twofold exploration is to establish a parallelism between the two fields in order to make a more general point. The parallel between the two fields can be stated this way: whereas in Deliberative Democracy, citizen participation is turned into a question for which technology is the answer, in STS, technology is turned into the question for which citizen participation is the answer.

Drawing on the concepts of frame analysis (Goffman, 1974; Mendonça and Simões, 2022), we can structure this parallelism in terms of dominant frames circulating within deliberative democracy and STS, in which the problems constructed and the treatment or remedy to those problems are inverted. Using Entman’s (1993) classical description of the four functions of frames, Table 1 describes the parallelism of those dominant frames.

In this context, I take “lack of efficiency” to mean the perceived struggles to take deliberative democracy to the masses or to get the best out of its epistemic properties. We see this frame clearly in action when, for instance, Hélene Landemore titles her work asking “Can Artificial Intelligence Bring Deliberation to the Masses” (Landemore, 2024) or when acclaimed practitioner Audrey Tang asserts that “AI can help democracy by assisting collective intelligence” (Spinney, 2024). But also, we see it play a role when technology is framed as “enhancing deliberation” (Mikhaylovskaya, 2024), “reducing the burden”(Deseriis, 2023), “improving decision-making” (McKinney, 2024), creating “democratic quality” (McKinney, 2024) or even fostering “ethical deliberation” (Sleigh et al. 2024). Of course, mobilising this frame does not mean that actors do not perceive risks and trade-offs, but rather, that they share a common problem definition around participation’s ability to meet its intended goals and technology as a potential solution for that.

Similarly, I take “lack of legitimacy” to mean the perceived struggles to come up with an answer to whose voices should be entitled to have a say in the political implications of technology. Legitimacy here reflects the question of the “rightful place of expertise”(Grundmann, 2018) or critical challenges as to “whose values and visions count” (Beck and Forsyth, 2020). As Reynolds et al. (2023) assert, public participation is often used as a means to both sociological and normative legitimacy (Reynolds, Kennedy, and Symons, 2023).

Under this light, public participation and technical solutions can act as problems or treatments depending on the frame in which they operate. But there is also a common thread uniting both frames in that they are based on the same normative principle of inclusivity. For deliberative democrats, technology plays a critical role in expanding the number of people who can participate effectively in political decision-making. For STS scholars, public participation plays a critical role in expanding the types of people whose perspectives are considered valid. Both draw from inclusivity understood as broadening who can be included in the specific domain of action.

It is important to note that these frames are not the only dominant frames within deliberative democracy or STS. As I have shown in the previous sections, both public participation in science and technology and the use of emerging digital technologies for deliberation have faced resistance and critical examinations in their respective fields. These frames should be understood as available within a constellation of other competing frames within complex disciplinary boundaries.

This apparent paradox –of technology and deliberation being simultaneously the answer and the question– speaks loudly of both democracy and technology as sources of a complicated mix of societal anxiety, fear, hopes, and hype. It also speaks of a somewhat weakened state of interdisciplinary dialogue between Deliberative Democracy and STS.

It is very strange indeed that deliberative democracy and STS have not been able to build more bridges. In the many areas they intersect, most notably in public engagement, these disciplines are often characterised as disconnected (Berg and Lidskog, 2018) or in conflict (Lövbrand et al. 2011). There are many ways one could go about explaining why this happens. For instance, STS scholars are usually very critical of the first generation of deliberative theorists and their apparent emphasis on rational argumentation, consensus and ideal speech scenarios (Scott, 2023), without necessarily acknowledging how the field has advanced the remaining 20 to 30 years.

In this sense, there are some stereotypes in how STS perceives deliberative democracy. These stereotypes are best captured by the recreated dialogues written in an unpublished piece by Bruno Latour (2005) that sought to capture how politics is debated within STS:

SHE: No conflict, no politics. Deliberative democracy has become the opium of the people. My feeling, for what it’s worth, is that if science studies, which used to be a radical movement, has of late degenerated into a wishy-washy appeal to consultation, roundtables, stakeholder meetings, and talks, talks, talks. then I give up…. It’s all about consensus conferences, focus groups, citizens’ debates. Habermas. Habermas everywhere. It stinks. (p.2).

SHE: This is where you become complacent and where science studies is either apolitical or ends up reviving the most traditional definitions of deliberative democracy: “Let’s talk”. You’re so enamoured with the complexities of the scientific or technical questions that you can’t even decide who is dominated and who is dominant. (p.5).

Funnily enough, Deliberative democrats do not usually engage with STS literature, and when they do, it is mostly with post-humanist theories, like Latour’s, and cyborg theories, like Donna Haraway’s –for instance (Asenbaum, 2021; Mendonça et al. 2024).

In a similar vein, a point of contention for both disciplines is around normativity. STS draws mainly from social constructivism and post-structuralism, whereas deliberative theory has historically found its origin in normative philosophy. That is why concepts like fairness, justice and equality are very prominent in democratic theory overall (Chambers, 2024), but would be very difficult to find non-critically in STS. When STS scholars refer to “the normative turn” (Lynch, 2014; Marris and Calvert, 2020), it is to describe how in practice, STS scholars engage with policy or political activism, not to describe the systematic development of normative theory; it is part of the turn to practice not to theory.

STS has historically been critical and even fearful of becoming explicitly normative (Radder, 1996). By extension, STS scholars are critical of what they perceive as deliberative democracy’s efforts to impose normativity as external guidelines for participation (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2020) in what could be construed as residual realism (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2020). In turn, STS tends to centre the normative assertion of reflexivity, both concerning the inherent uncertainties of knowledge and in how political actors frame issues for participation (Soneryd and Sundqvist, 2023c).

Despite all of these differences, there is arguably much more that binds the two fields. Centrally, their concerns for the use of arbitrary power –either from experts or professional politicians, and the systematic exclusion of citizens from formal power. Indeed, there are many lessons these two fields could draw from each other.

For deliberative democrats seeking to invigorate deliberative initiatives through the use of emerging digital tools, STS’s accumulated wealth of knowledge can be of immense benefit, at the very least in adding nuance to the following dimensions:

-

1.

Materiality matters: STS scholars have not only described and framed the politics of technology, but also how participation is carried out through artefacts. Following Marres’ (2015) approach to “material democracy” or “participation as if things mattered”, deliberative scholars could further inquire into the material entanglement of everyday deliberation, democratic innovations or even deliberative systems. From Ecological Kettles to Eco Show Homes or blogs, in Marres’ (2015) study of environmental politics, she shows how publics are not just mobilised, but enacted and performed through devices. More research is needed to understand the material entanglement of deliberative practices in a similar fashion, from the “little tools of democracy” (Asdal, 2008), to more hidden infrastructures (Star and Ruhleder, 1996) like the internet as a political infrastructure (Musiani, 2024).

-

2.

Design does not end in delivery: STS has extensively shown how technologies are socially shaped in practice (Williams and Edge, 1996). For instance, a critical takeaway from user studies within STS is that technology diffusion and implementation change the socio-technical characteristics of design because use leads to processes of technological domestication and user innovation (Stewart and Williams, 2005; Williams, 2019). In that sense, it is not enough to carefully interrogate the design process of civic technologies, but also how these designs change through implementation. In that sense, the political economy and political design of civic technologies, either for a market-driven vision or the construction of digital commons, are not only fought in development but in diffusion and use. Thus, more research is needed in the user domestication and innovation of civic technologies.

-

3.

Expertise and scientific knowledge cannot provide neutral and balanced learning: As shown in the previous section, the politics of expertise have been at the centre of STS’s concerns. The implications of this go very deep, even at a methodological level. This is why, for instance, participatory Technology Assessments (pTA; a typically STS kind of dialogic engagement) use “problem framing” instead of “learning phase” as it is usually done in deliberative mini-publics. More broadly, STS scholars have explored the fraught relationship between expertise and democratic systems (Eyal & Medvetz, 2023). Among other reasons, because the historical expectation of scientific discourse to domesticate the lay citizen (Akrich and Rabeharisoa, 2023) or even to suspend democratic politics in the name of urgency (Stehr and Ruser, 2023). More research is needed on how to critically and reflectively involve expertise in democratic innovations, and the legitimate role of expertise in deliberative systems.

For STS scholars, relationships with deliberative democracy have changed over time. It has been widely discussed how STS’s understanding of publics was heavily influenced by the first wave of deliberative democrats, including Habermas, Dahl and Cohen (Durant, 2011; Scott, 2023; Thorpe, 2008). However, more recent research has mainly been driven by STS’s own posthumanist or poststructural tradition. Some STS scholars have criticised that the field has lost contact with its political philosophy (Durant, 2010), or that it now takes as obvious a very thin defence of public participation given that “the technical is political, the political should be democratic and the democratic should be participatory” (Moore, 2010).

In that vein, STS scholars would greatly benefit from “reconnecting” with democratic theory, especially in Deliberative Democracy’s renewed interest in a more nuanced justification of democracy (Chambers, 2024) and account of the diversity of deliberation mechanisms (Elstub and Escobar, 2019a; Curato et al. 2021a). What Patrick Hamlett (2003) wrote almost two decades ago still rings true: “deliberative democracy and participatory public policy analysis, offer opportunities for social constructivist scholars to bridge the apparent gap between the program’s descriptive richness and its normative irrelevance” (p.134).

STS scholars could also benefit from the extensive contemporary literature within Deliberative Democracy that explores the inner workings of political systems. This encompasses the micropolitics of public servants designing engagement processes (Escobar, 2015; Escobar, 2022), the complexities of embedding participation within institutions (Bussu et al. 2022; Boswell et al. 2023), and the challenges of navigating interest politics and realpolitik (Hendriks, 2006; Curato et al. 2019). In summary, STS could gain from a more nuanced understanding of the roles and differences between the polity, politics, and policy of participation (Boswell et al. 2023).

More broadly, there is a shared risk for both academic communities around the temptations of solutionism. For STS, but also technoscientific institutions, there is a risk of reducing the problem of legitimacy to a problem of participation quantum. In other words, to rely on “participatory” solutionism that takes attention away from a more systemic view of democracy (Curato et al. 2021b), and also underemphasises how exclusion happens within the deliberative fora themselves (Young, 1997). As shown by Frahm et al. (2022), large technoscientific institutions have pushed a “democratic deficit of innovation” that frames countries’ complex process of implementing new technologies as if the determining factor is societies’ willingness to participate and engage in governance.

For deliberative democracy, it relates to the very well-known temptations of “technological solutionism” (Morozov, 2013) that when applied to deliberation, will nonetheless likely lead to disappointment (Schuler, 2020). Among other considerations, deliberative democracy should closely examine how democratic “problems” are framed and simplified by technologists when devising solutions, the kinds of political economies that emerge around these processes, and how the technologisation of participation redistributes power to expert communities while keeping other forms of work hidden from view (Birch, 2017; Pfotenhauer et al. 2022). It is worth reflecting on how, without integrating technological adoption with careful social analysis of technology, there is a risk that technological solutions may undermine some of the core principles of deliberative democracy.

I believe interdisciplinary dialogue between STS and Deliberative Democrats will be fundamental to restrict the power of both participatory and technological forms of solutionism that obscure the more complicated problems and potential solutions to societal challenges. In its absence, we may continue to see paradoxical movements in which, for some, technology is the problem, and participation is the quick solution, and for others, participation is the problem and technology is the quick solution.

On a final note, it must be recognised that there is a geopolitical dimension to this interplay of questions and answers. On a global stage, we might ask whose democracy is being solved by whose technology, and whose democracy is solving whose technology. Which countries get to set the rules? Which companies’ technology do governments buy? Who does not get to provide answers or get their questions heard? These questions highlight the unequal power dynamics inherent in the global governance of technology and democracy. They also raise concerns about how dominant narratives from wealthier nations and transnational corporations may marginalise diverse democratic practices and localised technological solutions in less powerful regions.

However, these geopolitical considerations remain beyond the scope of this article, representing a limitation of the current analysis. Future research could seek to address these issues more directly, exploring how these global power imbalances shape both the development of participatory technologies and the implementation of democratic deliberation in technoscience across different contexts.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Change history

24 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04884-y

References

Akrich M, Rabeharisoa V (2023) On the multiplicity of lay expertise: an empirical and analytical overview of patient associations’ achievements and challenges. In: Eyal G, Medvetz T (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Expertise and Democratic Politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 103–133

Alnemr N (2020) Emancipation cannot be programmed: blind spots of algorithmic facilitation in online deliberation. Contemp Politics 26(5):531–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1791306

Arnstein SR (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann 35(4):216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Asdal K (2008) On politics and the little tools of democracy: a down-to-earth approach. Distinktion: J Soc Theory 9(1):11–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2008.9672953

Asenbaum H (2021) Rethinking democratic innovations: a look through the kaleidoscope of democratic theory. 101177/14789299211052890 20(4):680–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299211052890

Bächtiger A, Dryzek JS (2024) Deliberative democracy for diabolical times. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bächtiger A, Parkinson J (2019) Unpacking deliberation. In: Mapping and measuring deliberation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 19–44

Bader V (2014) Sciences, politics, and associative democracy: democratizing science and expertizing democracy. Innov: Eur J Soc Sci Res 27(4):420–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2013.835465

Bauer A, Bogner A, Fuchs D (2021) Rethinking societal engagement under the heading of Responsible Research and Innovation: (novel) requirements and challenges. J Responsible Innov 8(3):342–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1909812

Beck S (2011) Moving beyond the linear model of expertise? IPCC and the test of adaptation. Reg Environ Change 11(2):297–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0136-2

Beck S, Forsyth T (2020) Who gets to imagine transformative change? Participation and representation in biodiversity assessments. Environ Conserv 47(4):220–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892920000272

Berg M, Lidskog R (2018) Deliberative democracy meets democratised science: a deliberative systems approach to global environmental governance. Env Polit 27(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1371919

Bernholz L, Landemore H, Reich R (2021) Digital technology and democratic theory. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, eds

Bijker WE, Hughes TP, Pinch T (1989) The social construction of technological systems: new directions in the sociology and history of technology. MIT Press, Cambridge, eds

Birch K (2017) Techno-economic Assumptions. Sci Cult (Lond 26(4):433–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2017.1377389

Birkbak A, Papazu I (eds) (2022) Democratic situations. Mattering Press

Boehner K, DiSalvo C (2016) Data, design and civics. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp 2970–2981

Boswell J, Dean R, Smith G (2023) Integrating citizen deliberation into climate governance: lessons on robust design from six climate assemblies. Public Adm 101(1):182–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12883

Braun B, Whatmore SJ (eds) (2010) Political matter, NED-New. University of Minnesota Press

Bussu S, Bua A, Dean R, Smith G (2022) Introduction: embedding participatory governance. Crit Policy Stud 16(2):133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2022.2053179

Chambers S (2003) Deliberative democratic theory. Annu Rev Political Sci 6(1):307–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085538

Chambers S (2009) Rhetoric and the Public Sphere. Polit Theory 37(3):323–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591709332336

Chambers S (2024) Contemporary Democratic Theory. Polity, Cambridge

Chilvers J, Kearnes M (2020) Remaking participation in science and democracy. Sci Technol Hum Values 45(3):347–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919850885

Cibrario G, Mejia M (2023) Getting CivicTech right for democracy: setting expectations and conditions for impact. In: Participo. https://medium.com/participo/getting-civictech-right-for-democracy-setting-expectations-and-conditions-for-impact-bf796bd029dd. Accessed 10 Jan 2024

Collins H, Evans R (2007) Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Collins H, Evans R, Weinel M (2017) STS as science or politics? Soc Stud Sci 47(4):580–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717710131

Collins H, Evans R, Innes M, Kennedy EB, Mason-Wilkes W, McLevey J (2022) The face-to-face principle: science, trust, democracy and the internet. Cardiff University Press, Cardiff

Collins HM, Evans R (2002) The third wave of science studies. Soc Stud Sci 32(2):235–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312702032002003

Curato N, Hammond M, Min JB (2019) Power in Deliberative Democracy. Springer International Publishing, Cham

Curato N, Sass J, Ercan SA, Niemeyer S (2020) Deliberative democracy in the age of serial crisis. 101177/0192512120941882 43(1):55–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120941882

Curato N, Dryzek JS, Ercan SA, Hendriks CM, Niemeyer S (2017) Twelve key findings in deliberative democracy research. Daedalus 146(3):28–38. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00444

Curato N, Farrell DM, Geissel B, Grönlund K, Mockler P, Pilet J-B, Renwick A, Rose J, Setälä M, Suiter J (2021a) The diversity of mini-publics: a systematic overview. In: Curato N, Farrell DM, Geissel B, Grönlund K, Mockler P, Pilet J-B, Renwick A, Rose J, Setälä M, Suiter J (eds) Deliberative mini-publics. Bristol University Press, Bristol, pp 17–33

Curato N, Farrell DM, Geissel B, Grönlund K, Mockler P, Pilet J-B, Renwick A, Rose J, Setälä M, Suiter J (2021b) Deliberative mini-publics in democratic systems. In: Curato N, Farrell DM, Geissel B, Grönlund K, Mockler P, Pilet J-B, Renwick A, Rose J, Setälä M, Suiter J (eds) Deliberative Mini-Publics. Bristol University Press, Bristol, pp 116–126

Davies S (2024) Science Societies. Bristol University Press, Bristol

Deseriis M (2023) Reducing the burden of decision in digital democracy applications: a comparative analysis of six decision-making software. Sci Technol Hum Values 48(2):401–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211054081

Douglas-Jones R (2022) Convene, represent, deliberate? Reasoning the democratic in embryonic stem cell research oversight committees. In: Birkbak A, Papazu I (eds) Democratic Situations. Mattering Press

Dryzek JS (2009) Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comp Polit Stud 42(11):1379–1402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009332129

Durant D (2010) Public participation in the making of science policy. Perspect Sci 18(2):189–225. https://doi.org/10.1162/posc.2010.18.2.189

Durant D (2011) Models of democracy in social studies of science. Soc Stud Sci 41(5):691–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312711414759

Einsiedel EF (2014) Publics and their participation in science and technology. In: Bucchi M, Trench B (eds). Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology. Routledge, Abingdon

Elstub S, Escobar O (2019a) Defining and typologising democratic innovations. In: Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 11–31

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43(4):51–58

Epstein S (1995) The construction of lay expertise: AIDS activism and the forging of credibility in the reform of clinical trials. Sci Technol Hum Values 20(4):408–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399502000402

Epstein S (2023) The meaning and significance of lay expertise. In: Eyal G, Medvetz T (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Expertise and Democratic Politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 76–102

Escobar O (2015) Scripting deliberative policy-making: dramaturgic policy analysis and engagement know-how. J Comp Policy Anal: Res Pract 17(3):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2014.946663

Escobar O (2022) Between radical aspirations and pragmatic challenges: Institutionalizing participatory governance in Scotland. Crit Policy Stud 16(2):146–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1993290

European Commission – directorate-general for research and innovation (2021) Horizon Europe, open science : early knowledge and data sharing, and open collaboration. Publications Office of the European Union

Eyal G (2019) The Crisis of Expertise. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK

Eyal G, Medvetz T (eds) (2023) The Oxford handbook of expertise and democratic politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Falk N, Lapesa G (2023) Bridging argument quality and deliberative quality annotations with adapters. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, pp 2469–2488

Felt U, Irwin A (2024) Introduction: on encyclopedias, maps and multiplicities in science and technology studies. In: Felt U, Irwin A (eds) Elgar Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 1–11

Felt U, Sepehr P (2024) Infrastructuring citizenry in Smart City Vienna: investigating participatory smartification between policy and practice. J Responsible Innov 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2024.2313303

Ford B (2021) Technologizing democracy or democratizing technology? A layered-architecture perspective on potentials and challenges. In: Digital Technology and Democratic Theory. University of Chicago Press, pp 274–308

Frahm N, Doezema T, Pfotenhauer S (2022) Fixing technology with society: the coproduction of democratic deficits and responsible innovation at the OECD and the European Commission. Sci Technol Hum Values 47(1):174–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243921999100

García DL, Idea I (2023) Democracy technologies in Europe: Online participation, deliberation and voting. international institute for democracy and electoral assistance (International IDEA), Vienna

Gastil J, Richards RC (2017) Embracing digital democracy: a call for building an online civic commons. Polit Sci Polit 50(03):758–763. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000555

Goddard A, Gillespie A (2023) Textual indicators of deliberative dialogue: a systematic review of methods for studying the quality of online dialogues. Soc Sci Comput Rev 41(6):2364–2385. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393231156629

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Harper & Row, New York, NY

Greco GM, Floridi L (2004) The tragedy of the digital commons. Ethics Inf Technol 6(2):73–81

Grobbink E, Peach K (2020) Combining crowds and machines. London

Grundmann R (2018) The rightful place of expertise. Soc Epistemol 32(6):372–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2018.1546347

Habermas J (1991) The structural transformation of the public sphere: an inquiry into a category of Bourgeois society. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Habermas J (1998) Between facts and norms: contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Hallin CA (2023) Collective intelligence, technology, and collective consciousness. In: Boucher S, Hallin CA, Paulson L (eds) The Routledge handbook of collective intelligence for democracy and governance. Routledge, London

Hamlett PW (2003) Technology theory and deliberative democracy. Sci Technol Hum Values 28(1):112–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243902238498

Harrison S, Mort M (1998) Which champions, which people? public and user involvement in health care as a technology of legitimation. Soc Policy Adm 32(1):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00086

Hendriks CM (2006) When the forum meets interest politics: strategic uses of public deliberation. 101177/0032329206293641 34(4):571–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329206293641

Horst M, Davies SR (2021) Science communication as culture. In: Bucchi M, Trench B (eds) Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, Third edit. Routledge, New York, p 16

Irwin A (2014) From deficit to democracy (re-visited). Public Underst Sci 23(1):71–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662513510646

Jasanoff S (2016) The ethics of invention: technology and the human future. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Justice J, Mcnutt JG, Melitski J, Ahn M, David N, Siddiqui S, Ronquillo JC (2018) The civic technology movement: implications for nonprofit theory and practice. In: McNutt JG (ed) Technology, Activism and Social Justice in a Digital Age. Oxford University Press, London & New York

Kearnes M, Chilvers J (2024) Public engagement and participation revisited. In: Felt U, Irwin A (eds) Elgar Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 194–204

Kim S, Eun J, Seering J, Lee J (2021) Moderator chatbot for deliberative discussion. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact 5(CSCW1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449161

Krick E (2022) Citizen experts in participatory governance: democratic and epistemic assets of service user involvement, local knowledge and citizen science. Curr Sociol 70(7):994–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921211059225

Krick E, Meriluoto T (2022) The advent of the citizen expert: Democratising or pushing the boundaries of expertise? Curr Sociol 70(7):967–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221078043

Lafont C (2019) Democracy without Shortcuts. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lafont C (2020) Democracy Without Shortcuts: a participatory conception of deliberative democracy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Landemore H (2024) Can artificial intelligence bring deliberation to the masses? Conversations in Philosophy, Law, and Politics 39–69

Latour B (1988) The pasteurization of France. Harvard University Press

Latour B (2005) Critical distance or critical proximity? https://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/P-113-HARAWAY.pdf

Laurent B (2023) Institutions of expert judgment: the production and use of objectivity in public expertise. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise and Democratic Politics 214–236

Levidow L (1998) Democratizing technology—or technologizing democracy? Regulating agricultural biotechnology in Europe. Technol Soc 20(2):211–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(98)00003-7

Lövbrand E, Pielke R, Beck S (2011) A democracy paradox in studies of science and technology. Sci Technol Hum Values 36(4):474–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910366154

Lynch M (2017) STS, symmetry and post-truth. 101177/0306312717720308 47(4):593–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717720308

Lynch M, Cole S (2005) Science and technology studies on trial. Soc Stud Sci 35(2):269–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705048715

Lynch M (2014) From normative to descriptive and back: science and technology studies and the practice turn. In: Soler L, Zwart S, Lynch M, Israel-Jost V (eds) Science after the practice turn in the philosophy, history, and social studies of science. Routledge, New York, pp 93–113

Macnaghten P (2024) Methods and politics of public engagement and STS. In: Felt U, Irwin A (eds) Elgar Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 137–144

Magaudda P (2024) Technology as culture. In: Felt U, Irwin A (eds) Elgar Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 61–71

Mansbridge J, Bohman J, Chambers S, Christiano T, Fung A, Parkinson J, Thompson DF, Warren ME (2012) A systemic approach to deliberative democracy. In: Deliberative Systems. Cambridge University Press, pp 1–26

Marres N (2015) Material Participation. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London

Marris C, Calvert J (2020) Science and technology studies in policy: the UK synthetic biology roadmap. Sci Technol Hum Values 45(1):34–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919828107

Martí JL (2021) The role of new technologies in deliberative democracy. In: Giuliano A, Benedetta B, Cesare P (eds) Rule of Law v. Majoritarian Democracy. Bloomsbury Publishing, Oxford, pp 199–220

McKinney S (2024) Integrating artificial intelligence into citizens’ assemblies: benefits, concerns and future pathways. J Deliber Democr 20(1)

Mellon J, Peixoto TC, Sjoberg FM (2022) The haves and the have nots: civic technologies and the pathways to government responsiveness. The World Bank, Washington, D.C

Mendonça RF, Simões PG (2022) Frame analysis. In: Research methods in deliberative democracy

Mendonça RF, Veloso LHN, Magalhães BD, Motta FM (2024) Deliberative ecologies: a relational critique of deliberative systems. Eur Polit Sci Rev, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000358

Merton RK (1966) Dilemmas of democracy in the voluntary association. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 66(5)

Mikhaylovskaya A (2024) Enhancing deliberation with digital democratic innovations. Philos Technol 37(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-023-00692-x

Miller TR, Neff MW (2013) De-facto science policy in the making: how scientists shape science policy and why it matters (or, why STS and STP scholars should socialize). Minerva 51(3):295–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-013-9234-x

Moore A (2010) Review: beyond participation: opening up political theory in STS. Soc Stud Sci 40(5):793–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312710383070

Morozov E (2013) To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. PublicAffairs, New York

Musiani F (2024) Understanding infrastructure as (internet) governance. In: Padovani C, Wavre V, Hintz A, Goggin G, Iosifidis P (eds) Global communication governance at the crossroads. Global transformations in media and communication research. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 297–314

Nahuis R, van Lente H (2008) Where are the politics? Perspectives on democracy and technology. Sci Technol Hum Values 33(5):559–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907306700

Németh R (2023) A scoping review on the use of natural language processing in research on political polarization: trends and research prospects. J Comput Soc Sci 6(1):289–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-022-00196-2

Niemeyer S, Jennstal J (2018) Scaling up deliberative effects—applying lessons of mini-publics. In: Bächtiger A, Dryzek JS, Mansbridge J, Warren M (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford University Press, pp 328–347

Noveck BS (2018) Crowdlaw: collective intelligence and lawmaking. Anal Krit 40(2):359–380. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2018-0020

Ovadya A (2023) Reimagining democracy for AI. J Democr 34(4):162–170. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2023.a907697

Owen R, Stilgoe J, Macnaghten P, Gorman M, Fisher E, Guston D (2013) A framework for responsible innovation. In: Responsible Innovation. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, pp 27–50

Palumbo A (2024) Deliberative democracy as a conceptual landscape. In: Palumbo A (ed) The Deliberative Turn in Democratic Theory: Models, Methods, Misconceptions. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, pp 1–39

Patel M, Sotsky J, Gourley S, Houghton D (2013) Emergence of civic tech: investments in a growing field

Peixoto T, Sifry ML (2017) Civic tech in the Global South. The World Bank Group

Pfotenhauer S, Laurent B, Papageorgiou K, Stilgoe J (2022) The politics of scaling. Soc Stud Sci 52(1):3–34. 10.1177/03063127211048945/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_03063127211048945-FIG4.JPEG

Pielke JrRA (2007) The Honest Broker. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Radder H (1996) In and About the World: Philosophical Studies of Science and Technology. SUNY Press, New York

Reynolds JL, Kennedy EB, Symons J (2023) If deliberation is the answer, what is the question? Objectives and evaluation of public participation and engagement in science and technology. J Responsible Innov 10(1):2129543. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2022.2129543

Robinson P, Johnson P (2023) The platformization of public participation: considerations for urban planners navigating new engagement tools BT - Intelligence for Future Cities. In: Goodspeed R, Sengupta R, Kyttä M, Pettit C (eds) Intelligence for Future Cities. Springer Nature, Cham, pp 71–87

Romberg J, Escher T (2023) Making sense of citizens’ input through artificial intelligence. Digit Gov Res Pract 5(3):1–30

Russon Gilman H, Carneiro Peixoto T (2019) Digital participation. In: Elstub S, Escobar O (eds) Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 105–118

Saldivar J, Parra C, Alcaraz M, Arteta R, Cernuzzi L (2019) Civic technology for social innovation. Comput Supp Coop Work 28(1–2):169–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-018-9311-7

Schaefer R, Stede M (2021) Argument mining on Twitter: a survey. Inf Technol 63(1):45–58. https://doi.org/10.1515/itit-2020-0053

Schuler D (2020) Can technology support democracy? Digit Gov Res Pract 1(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3352462

Scott D (2023) Diversifying the deliberative turn: toward an agonistic RRI. Sci Technol Hum Values 48(2):295–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211067268

Scudder MF (2023) Deliberative democracy, more than deliberation. Polit Stud 71(1):238–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211032624

Seger E, Ovadya A, Siddarth D, Garfinkel B, Dafoe A (2023) Democratising AI: multiple meanings, goals, and methods. In: Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society. ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp 715–722

Shaw E (2018) Skipping ahead to the good part: the role of civic technology in achieving the promise of E-government. JeDEM 10(2):74–96. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v10i1.455

Sismondo S (2017) Post-truth? Soc Stud Sci 47(1):3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312717692076

Sismondo S (2010) An introduction to science and technology studies, 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester

Sleigh J, Hubbs S, Blasimme A, Vayena E (2024) Can digital tools foster ethical deliberation? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02629-x

Soneryd L, Sundqvist G (2023) Science and Democracy. Bristol University Press, Bristol

Soneryd L, Sundqvist G (2022) Leaks and overflows: two contrasting cases of hybrid participation in environmental governance. In: Birkbak A, Papazu I (eds) Democratic Situations. Mattering Press

Spinney L (2024) AI can help democracy by assisting collective intelligence. N Sci (1956) 263(3498):40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(24)01237-5

Star SL, Ruhleder K (1996) Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: design and access for large information spaces. Inf Syst Res 7(1):111–134. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111

Stehr N, Ruser A (2023) The political climate and climate politics—expert knowledge and democracy. In: Eyal G, Medvetz T (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Expertise and Democratic Politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 134–152

Stewart J, Williams R (2005) The wrong trousers? Beyond the design fallacy: social learning and the user. In: Howcroft D, Trauth EM (eds) Handbook of Critical Information Systems Research. Edward Elgar Publishing

Stilgoe J, Lock SJ, Wilsdon J (2014) Why should we promote public engagement with science? Public Underst Sci 23(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662513518154

Strasser BJ, Baudry J, Mahr D, Sanchez G, Tancoigne E (2018) “Citizen Science”? Rethinking science and public participation. Science & Technology Studies:52–76. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.60425

Sturgis P, Allum N (2004) Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst Sci 13(1):55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662504042690

Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW (2010) The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol 29(1):24–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X09351676

Thorpe C (2008) Political theory in science and technology studies. In: Hackkett EJ, Amsterdamska O, Lynch M, Wajcman J (eds) The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Tian L, Lai C, Moore J (2018) Polarity and Intensity: the two aspects of sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of Grand Challenge and Workshop on Human Multimodal Language (Challenge-HML). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, pp 40–47