Abstract

The central aim of this research is to investigate the underlying mechanism between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity in adolescents, addressing a pivotal area as moral development significantly influences the overall ethical conduct and societal integration of young individuals. In this analysis, 4921 Chinese adolescents aged 12–20 years participated by filling out an anonymous self-report questionnaire. Our findings revealed that: (1) the teacher–student relationship has a positive relationship with moral sensitivity; (2) both perceived social support and moral identity served as mediators in the connection between the teacher–student relationship and moral sensitivity; (3) the teacher–student relationship indirectly influenced moral sensitivity through the sequential mediation of perceived social support and moral identity; and (4) problematic social media use does not significantly moderate the positive impact of teacher–student relationships on moral sensitivity. Based on these discoveries, the research has pinpointed potential factors and proposed actionable strategies to enhance moral sensitivity among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moral sensitivity—the capacity to recognize moral dimensions and respond to ethical dilemmas in social contexts—serves as a fundamental determinant of ethical behavior and prosocial development (Kraaijeveld et al., 2021). As a crucial component in Rest’s four-component model of moral behavior, moral sensitivity functions as the cognitive gateway through which individuals perceive and process moral issues, thereby guiding subsequent moral judgment, motivation, and character development (Savur, 2022). Enhanced moral sensitivity correlates with improved ethical decision-making capabilities (Fowler et al., 2009) and reduced aggressive behaviors (Chen et al., 2018), while its diminishment may lead to moral disengagement and antisocial tendencies (Marples, 2022). Given these significant implications for adolescent development and social functioning, identifying key factors that shape moral sensitivity remains a critical research imperative.

Previous investigations have predominantly focused on cognitive factors (Riedel et al., 2022), contextual influences (Kara et al., 2016), and personality traits (Abbasi-Asl and Hashemi, 2019) in moral sensitivity development. However, the role of social relationships, particularly within educational contexts where adolescent moral formation primarily occurs, remains insufficiently explored. According to ecological systems theory, schools constitute the primary microsystem for adolescent development beyond family structures, with teacher–student relationships playing a pivotal role in social-moral development (Hampden-Thompson and Galindo, 2017). While positive teacher–student relationships foster moral exploration and ethical growth (Zheng, 2022), strained relationships may impede moral sensitivity development (Kang and Zhang, 2023).

Crucially, emerging research suggests that the mechanisms linking teacher–student relationships to moral sensitivity may be more complex than previously understood. Recent theoretical developments in social cognitive neuroscience indicate that perceived social support might serve as a critical mediating mechanism, given its role in facilitating moral information processing and ethical awareness (Wilke et al., 2024). Similarly, moral identity—conceptualized as the centrality of moral values to self-concept—has emerged as a potential mediating factor, particularly salient during adolescence when identity formation peaks (Lapsley and Hardy, 2017). Furthermore, in today’s digital landscape, problematic social media use represents an increasingly important moderating factor, potentially disrupting traditional social-moral learning processes in educational settings (Huang et al., 2023).

This study seeks to explore the intricate pathways through which teacher–student relationships influence moral sensitivity, with a specific focus on the mediating roles of perceived social support and moral identity. Additionally, the moderating effect of problematic social media use will be examined to better understand how digital behaviors shape or hinder moral development in adolescents. By integrating these relational, cognitive, and contextual factors into a unified framework, this research aims to fill critical gaps in the literature and provide actionable insights for fostering moral sensitivity within the dynamic landscape of modern educational environments.

Literature review

The association between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity

Attachment theory posits that early relationships exert a profound influence on emotional and social development throughout life (Bowlby, 1979; Snyder et al., 2024). Secure attachments, formed through consistent and responsive caregiving, provide a foundation for individuals to navigate their environment and build trusting relationships (Ainsworth et al., 2015; Bowlby, 1982). These early experiences significantly shape subsequent social interactions and moral development (Moreira et al., 2021). Teachers are the formal authorities in the education system who not only impart knowledge, but also convey socially accepted values and ethics through their words and actions. Adolescents are heavily exposed to and imitate the behavior of teachers in the school environment, which has a direct impact on the formation of their moral sensitivity (Malti et al., 2021). Teachers act as role models, dealing with conflict and treating students in ways that are imitated by students, which in turn influences their moral judgments and behavioral choices (Gui et al., 2020). Research has shown that teachers’ emotional support, academic guidance, and nurturing of social skills are positively associated with higher levels of moral perception and conduct in students (Jianga et al., 2022). Students are more likely to demonstrate higher levels of moral sensitivity and pro-social behavior when they perceive teachers as fair and caring role models (Su and Wang, 2022).

In the context of adolescence, the teacher–student relationship often serves as a crucial attachment figure (García-Moya and García-Moya, 2020). A secure attachment in this relationship, characterized by trust, empathy, and emotional support, empowers adolescents to confidently explore moral dilemmas and engage in open discussions about ethical concerns. Such relationships foster emotional security and enhance adolescents’ ability to understand others’ perspectives, which is essential for fostering moral development (García-Rodríguez et al., 2023). Attachment theory posits that individuals who form secure attachments are more inclined to demonstrate empathy and compassion toward others, qualities that are also essential for fostering effective moral development (Deneault et al., 2023).

Therefore, our first hypothesis (H1) is that the teacher–student relationship may be positively associated with adolescents’ moral sensitivity.

Perceived social support as a mediator

Perceived social support, defined as individuals’ perception of respect, care, and assistance from significant others, including family, friends, and teachers (Zimet et al., 1988; Luan et al., 2023), plays a critical role in shaping interpersonal dynamics and social cognition. According to social information processing theory (Wyer and Srull, 2014), individuals interpret new social information based on pre-existing schemas and experiences, which include notions of support, assistance, rejection, and harm. Perceived social support provides a cognitive framework of interpersonal interactions that equips individuals with prior experiential knowledge to process moral issues, which often arise in social contexts (Caban et al., 2023). Consequently, this framework can enhance moral sensitivity by enabling individuals to recognize and respond to moral dilemmas more effectively. Empirical evidence further supports this link, as Xiang et al. (2020) demonstrated that higher levels of social support positively correlate with enhanced moral sensitivity.

Within educational settings, the teacher–student relationship serves as a pivotal source of perceived social support. Teachers’ behaviors, such as providing care and respect, significantly shape students’ perceptions of being valued within their broader social networks, including family and peers (Sabol and Pianta, 2012). Positive teacher–student relationships create environments where students feel safe, respected, and supported, thereby strengthening their perception of social support (Amerstorfer and Freiin von Münster-Kistner, 2021). This enhanced perception of social support equips students with social and emotional resources to better navigate interpersonal interactions, ultimately contributing to greater moral sensitivity.

In exploring the complex interplay involving teacher–student relationships, perceived social support, and moral sensitivity, a plausible conjecture (Hypothesis H2) emerges that perceived social support potentially functions as an intermediary variable in the association between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity.

Moral identity as a mediator

Moral identity refers to a set of cognitive schemas centered around moral qualities, including moral values, goals, and behavioral scripts (Narvaez and Lapsley, 2009), with dimensions encompassing internalization and symbolization. Internalization of moral identity denotes the core extent to which an individual’s moral qualities are integrated into their self-concept, indicating the importance of moral qualities to the self (Aquino and Reed, 2002). As proposed by Aquino et al. (2009), the social cognitive model of moral behavior suggests that a stronger internalized moral identity enhances the salience of moral schemas in an individual’s working self-concept, which in turn increases their accessibility in cognitive processes. This facilitates the more frequent and swift use of these moral schemas to evaluate both personal and others’ actions from a moral standpoint, thereby leading to heightened moral sensitivity. Furthermore, Sparks (2015), expanding on this framework, has shown that a more deeply internalized moral identity is a positive predictor of moral sensitivity.

The teacher–student relationship represents a pivotal social dynamic within educational contexts, exerting profound influences on adolescents’ moral identity formation (Schipper et al., 2023). Moral identity, a construct rooted in social cognitive theory, pertains to the internalization and integration of moral values into one’s self-concept (Rullo et al., 2022). This identity development is significantly shaped by interpersonal interactions, with educators serving as crucial figures in this process (Brezina and Piquero, 2017). According to social learning theories, individuals acquire and refine moral behaviors through observation, modeling, and interpersonal reinforcement (Bandura, 1986; Bock and Samuelson, 2014). Within the educational setting, teachers function not only as instructors but also as role models who demonstrate ethical behaviors and norms (Lian et al., 2020). Positive teacher–student relationships characterized by trust, respect, and support foster an environment conducive to moral development (Wang, 2023). Conversely, negative or distant relationships may impede adolescents’ moral identity formation by limiting opportunities for moral reasoning and ethical reflection (Fatima et al., 2020). Thus, the quality of teacher–student relationships emerges as a critical determinant in shaping adolescents’ moral identity, underscoring the profound impact of educational environments on ethical development during formative years.

Thus, we expect that moral identity might function as a mediating element in the connection between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity (Hypothesis H3).

The chain mediating role of perceived social support and moral identity

Perceived social support asserts that individuals’ perceptions of support from their social networks and environment shape their cognitive and emotional processes, thereby impacting their self-concept and identity development (Yang et al., 2022). Specifically, for adolescents navigating the complex terrain of moral identity formation, perceived social support serves as a crucial determinant. According to social support theory, perceived support from family, peers, and community provides adolescents with a sense of belonging and validation, fostering their moral self-concept (Sisodia and Bhambri, 2024). This validation and affirmation from significant others help adolescents internalize societal norms and ethical principles, thus reinforcing their moral identity development. Moreover, adolescents who perceive higher levels of social support are more likely to exhibit greater moral clarity and adherence to ethical standards, as they draw upon supportive relationships to navigate moral dilemmas and conflicts (Gawronski, 2022). Therefore, perceived social support acts as a critical determinant in shaping adolescents’ moral identity through its influence on their cognitive and emotional responses to moral challenges and ethical decision-making processes.

Building on the previous discussion, it can be inferred that there exists an interrelated framework connecting the teacher–student relationship with perceived social support, as well as the association between perceived social support and moral identity, which ultimately influences the link between moral identity and moral sensitivity. Hence, it suggests that the teacher–student relationship might influence moral sensitivity indirectly through a sequentially mediated process that encompasses perceived social support and moral identity variables (Hypothesis H4).

Problematic social media use may impact the association between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity

Technological conflicts theory posits that the pervasive integration of digital technologies, such as social media platforms, introduces new dynamics into interpersonal relationships, including those within educational contexts (Ling, 2012). Specifically, concerning teacher–student relationships, which traditionally serve as crucial conduits for moral development and ethical understanding in educational settings (Ibrahim and El Zaatari, 2020), problematic social media use may undermine these dynamics. According to technological conflicts theory, excessive engagement with social media can lead to diminished face-to-face interactions and reduced quality of interpersonal communication (Kolhar et al., 2021). As a result, the depth and authenticity of teacher–student relationships may be compromised, thereby potentially weakening the transmission of moral values and ethical principles from teachers to students (Biesta, 2015; Pinar, 2019). Moreover, problematic social media use might contribute to distractions, misunderstandings, and conflicts within these relationships, detracting from the fostering of moral sensitivity among students (Baumeister and Leary, 2017; Zimmer, 2022).

Thus, it is likely that problematic social media use acts as a moderating factor between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity (Hypothesis H4).

The present study

The complex array of influences on adolescent moral sensitivity, encompassing school and individual factors, underscores the necessity of promoting moral sensitivity beyond a single-domain approach. The current findings indicate that the teacher–student relationship serves as a significant predictor of moral sensitivity, with perceived social support and moral identity potentially acting as mediating factors. Furthermore, the influence of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity may be contingent upon the extent of problematic social media use, where higher levels could moderate this relationship. This study contributes to the advancement of effective intervention strategies aimed at fostering adolescent moral sensitivity, an area that remains underexplored in existing literature. To the best of our knowledge, this research represents the first investigation into the combined effects of the teacher–student relationship, perceived social support, moral identity, and problematic social media use on adolescent moral sensitivity.

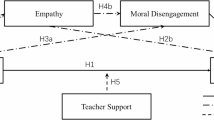

Aligned with our research objectives, we propose a series of hypotheses, labeled H1 through H5, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): an enhanced teacher–student relationship is associated with higher levels of moral sensitivity in adolescents. Hypothesis 2 (H2): perceived social support mediates the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity. Hypothesis 3 (H3): moral identity mediates the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity. Hypothesis 4 (H4): perceived social support and moral identity exhibit a chain mediating effect in the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity. Hypothesis 5 (H5): problematic social media use attenuates the positive impact of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity among adolescents.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): an enhanced teacher–student relationship is associated with higher levels of moral sensitivity in adolescents.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): perceived social support mediates the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): moral identity mediates the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): perceived social support and moral identity exhibit a chain mediating effect in the relationship between teacher and student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): problematic social media use attenuates the positive impact of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity among adolescents.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study enrolled a cohort of 4921 participants from 9 junior high schools and 10 senior high schools situated across the provinces of Shanxi, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Guangdong, Liaoning, Guizhou, Hainan, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi in China, utilizing a combined method of stratified and random cluster sampling. Data collection commenced in May 2024. Institutional approvals were obtained from the respective schools, and both participants and their guardians provided informed written consent. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, consent forms were designed without participant signatures or names. Participants were clearly informed of the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to withdraw at any point. Separate questionnaires were administered to parents and adolescents. Trained research assistants supervised students during school hours as they independently completed paper-based questionnaires. Questionnaires returned with missing pages or incomplete responses to more than three items were excluded from the analysis. Completed questionnaires were securely sealed in envelopes for further processing.

After a comprehensive review of the data, 235 questionnaires were excluded due to missing or incomplete information. The final dataset comprised 4,921 meticulously scrutinized questionnaires, demonstrating a robust response rate of 95.44%. Participants’ ages ranged from 12 years to 20 years (M = 15.51, SD = 1.572), with males accounting for 42.3% (N = 2,083) and females 57.7% (N = 2,838) of the sample. The research ethics committee at the university where the first author is affiliated approved all methodologies employed in this study.

Measures

Teacher–student relationship. The teacher–student relationship scale, initially devised by Pianta (1994) and subsequently adapted by Zou et al. (2007) to reflect the Chinese educational setting, is extensively applied to evaluate interactions between teachers and students in China. This modified scale comprises 23 items distributed across four categories: intimacy, conflict, support, and satisfaction. It is evaluated by students and has been prominently used in recent empirical investigations into teacher–student dynamics, including studies by Wu and Zhang (2022) and Yang et al. (2023). An example provided in the questionnaire states, “The relationship between the teacher and myself is intimate and warm”. The assessment employs a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 ‘strongly agree,’ with the items in the conflict dimension being reverse-scored prior to averaging them with the scores from the other dimensions. A higher aggregate score suggests a more positive teacher–student relationship. The indices of CFA showed an excellent fit for the 23-item four-factor structure: CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.047, SRMR = 0.035. Notably, the scale exhibits robust internal reliability, achieving a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.955.

Moral sensitivity. Moral sensitivity was measured using the ‘Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire’ developed by Guo and Du (2013), which is based on Rest’s et al. (1997) four-component model of moral behavior, specifically focusing on the moral sensitivity component. This scale is a robust instrument whose validity and reliability have been established in prior research (Lu and Fu, 2021). This questionnaire encompasses four factors: responsibility sensitivity, normative sensitivity, emotional sensitivity, and interpersonal sensitivity. Responsibility sensitivity reflects an individual’s acuity in recognizing moral obligations and includes aspects of tolerance and responsibility attribution. Normative sensitivity gauges an individual’s acuteness to the moral norms of behavior, encompassing awareness of societal morals and respect for others. Emotional sensitivity measures an individual’s keen grasp of both their own and others’ emotions, including expressive and understanding capabilities. Interpersonal sensitivity assesses an individual’s sharp awareness of interpersonal relations, involving handling interpersonal differences and caring for others. The questionnaire contains 35 items, with an example item stating, “If a trash bin is far from me, I would dispose of my trash on the ground without considering the increased workload for the cleaning staff.” Scoring is on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of moral sensitivity. CFA results demonstrated a good model fit for the 35-item four-factor structure: CFI = 0.955, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.042. The overall internal consistency coefficient of the questionnaire in this survey was 0.975.

Perceived social support. Perceived social support was evaluated using the Chinese adaptation of the Perceived Social Support Scale, initially developed by Zimet et al. (1988) and subsequently revised by Jiang (1999). This instrument has been validated and its reliability confirmed in prior research (Gong et al. 2022; Tan et al. 2022). This scale includes 12 items that measure the degree of social support an individual perceives from significant others such as family, teachers, and friends. An example item from the questionnaire is, “I can receive emotional help and support from my family when needed.” The responses are scored on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support. The 12-item scale showed excellent fit indices in CFA: CFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.045, and SRMR = 0.031. The reliability of this measure was confirmed by a robust Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.954.

Moral identity. Moral identity was measured using the Moral Identity Scale developed by Aquino and Reed (2002), which assesses the level of moral identity among university students. The questionnaire consists of two components: explicit moral identity and implicit moral identity, comprising a total of ten items, such as “I would feel good about being a person who has these characteristics.” Responses to all items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 signifies “strongly disagree” and 5 indicates “strongly agree.” Items 8 and 9 are scored in reverse. A higher overall score suggests a higher level of moral identity. Studies involving Chinese students have demonstrated the questionnaire’s strong validity and reliability (Hu and Xiong, 2024; Wang et al., 2017). CFA results for the 10-item two-factor structure indicated a good fit: CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.037. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the questionnaire was 0.857.

Problematic social media use. This study employed the Adolescent Problematic Social Media Use Assessment Questionnaire developed by Jiang (2018) to measure problematic social media use among adolescents. This instrument is noted for its robust psychometric properties in evaluating Chinese adolescents, as documented by Li (2024). The questionnaire comprises 20 items organized into five factors: increased attachment, physiological impairment, fear of missing out, guilt, and cognitive failure. An example item reads: “I often feel worried and anxious when my phone cannot connect to the internet and I cannot access social media apps.” Scoring is based on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more severe issues with social media use among adolescents. The 20-item five-factor model demonstrated excellent fit indices: CFI = 0.972, TLI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.033. Notably, the instrument has demonstrated strong internal reliability, reflected by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.956.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0 and MPLUS version 8.3. To initially assess the potential presence of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. Following this, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were employed to examine the relationships among the key variables. For all constructs in the study, the mean scores of the observed items were calculated and directly used in all subsequent analyses, including the structural equation modeling (SEM) and moderation analysis. This approach allowed for a simplified model while preserving the validity of the constructs. Prior to calculating mean scores, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted for each scale to verify unidimensionality and internal consistency. All scales demonstrated excellent fit indices (e.g., CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, SRMR < 0.08) and high internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.85), supporting the use of aggregated mean scores as representative of the latent constructs. Based on these mean scores, structural equation modeling was utilized to examine the proposed chain mediation model, in which the teacher–student relationship served as the predictor, perceived social support and moral identity functioned as mediators, and adolescent moral sensitivity was the outcome variable. Mediation was considered established if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect did not include zero, with significance determined through bootstrapped CIs derived from 5000 resampled iterations. Finally, moderation analyses were performed using the PROCESS 4.0 macro in SPSS. Moderation effects were tested by creating interaction terms between the predictor and the moderator (e.g., problematic social media use). All moderation analyses incorporated relevant covariates, and simple slopes analysis was performed to interpret significant interactions.

Results

Common method bias test

Harman’s single-factor test was utilized to assess potential common method bias (Zhou and Long, 2004). Exploratory factor analysis identified 12 factors, each with eigenvalues surpassing 1. The principal factor accounted for 28.279% of the total variance, falling below the commonly cited threshold of 40% which signifies substantial common method bias. This finding indicates that concerns regarding common method bias are unlikely, thus permitting continued analysis without this constraint.

Correlation analysis of variables

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations (SDs), and Pearson correlation coefficients for the key variables under investigation. The findings indicate significant associations among these variables. Specifically, the teacher–student relationship showed positive correlations with moral sensitivity (r = 0.548, p < 0.001), perceived social support (r = 0.520, p < 0.001), and moral identity (r = 0.480, p < 0.001), and a negative correlation with problematic social media use (r = −0.134, p < 0.001). Similarly, moral sensitivity exhibited positive correlations with perceived social support (r = 0.601, p < 0.001) and moral identity (r = 0.518, p < 0.001), and a negative correlation with problematic social media use (r = −0.251, p < 0.001). Additionally, perceived social support demonstrated positive associations with moral identity (r = 0.540, p < 0.001) and problematic social media use (r = 0.034, p < 0.05), whereas moral identity was negatively correlated with problematic social media use (r = −0.256, p < 0.001).

Mediation analysis

The initial phase of the analysis involved calculating the mean values of the variables under investigation, followed by constructing a structural equation model (SEM). The resulting comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) both attained perfect scores of 1, while the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) registered values of zero. These metrics collectively indicate that the research model employed in this study demonstrates robust predictive validity. Subsequently, a sequential mediation model was evaluated, encompassing three indirect pathways: (1) perceived social support mediated the relationship between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity; (2) moral identity served as a mediator between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity; and (3) teacher–student relationship exerted an indirect influence on moral sensitivity through the sequential mediating roles of perceived social support and moral identity (see Fig. 2).

The findings demonstrated that the teacher–student relationship and moral sensitivity exhibited a significant and positive relationship (β = 0.548, t = 54.987, p < 0.001). When controlling for various confounders, the direct effect of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity remained significant and positive (β = 0.269, t = 12.649, p < 0.001). Additionally, a positive and significant association was observed between the teacher and student relationship and perceived social support (β = 0.520, t = 42.352, p < 0.001), with perceived social support also showing a significant and positive correlation with moral sensitivity (β = 0.354, t = 21.447, p < 0.001). Further, the teacher–student relationship correlated positively and significantly with moral identity (β = 0.273, t = 14.512, p < 0.001), which notably exhibited a significant and positive effect on moral sensitivity (β = 0.197, t = 10.090, p < 0.001). Moreover, a substantial and positive link between perceived social support and moral identity was also established (β = 0.398, t = 23.421, p < 0.001).

Furthermore, as illustrated in Table 2, the total effect of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity was estimated at 0.548 (SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.512, 0.583], p < 0.001), with a direct effect observed at 0.269 (SE = 0.021, 95% CI [0.227, 0.311], p < 0.001). Both effects demonstrated statistical significance. The indirect pathway from the teacher–student relationship through perceived social support to moral sensitivity yielded an indirect effect of 0.184 (SE = 0.009, 95% CI [0.167, 0.202], p < 0.001), constituting 33.577% of the total effect (0.548). Additionally, the indirect effect via the path from the teacher–student relationship to moral identity and subsequently to moral sensitivity was calculated at 0.054 (SE = 0.006, 95% CI [0.042, 0.067], p < 0.001), representing 9.854% of the total effect. Another indirect effect of 0.041 (SE = 0.005, 95% CI [0.032, 0.051], p < 0.001) was identified in the pathway involving both perceived social support and moral identity, accounting for 7.482% of the total effect. These three indirect effects were statistically significant, as evidenced by Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals that excluded zero. The analysis underscores that the impact of the teacher–student relationship on moral sensitivity is significantly mediated through perceived social support and moral identity, acting as robust and positive partial mediators within this relational context.

Moderation analysis

Table 3 presents findings that clarify the moderating influence of problematic social media use on the association between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity. Initially, the regression coefficient for teacher–student relationships was 0.496, demonstrating statistical significance at the 0.1% level (p < 0.001). However, the coefficient for the interaction term between teacher and student relationships and problematic social media use was 0.013, which was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

As depicted in Fig. 3, an in-depth examination of the moderating effect was conducted through a simple slopes analysis, considering conditions of low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of problematic social media use. The results confirmed a significant moderating influence across all cohorts. However, the positive relationship between the teacher–student relationship and moral sensitivity did not exhibit a statistically significant difference between individuals with high and low levels of problematic social media use.

Discussion

The teacher–student relationship is positively associated with the moral sensitivity of adolescents

The findings of this study provide strong support for the initial hypothesis (H1) that posited the significance of teacher–student relationships in fostering moral sensitivity among adolescents. The observed correlation underscores the pivotal role that these relationships play in shaping moral development during this critical developmental stage. By cultivating a supportive and nurturing environment, teachers not only impart knowledge but also contribute significantly to the ethical framework within which students navigate their social and moral decisions.

It has been demonstrated that positive teacher–student relationships have a beneficial impact on the moral sensitivity of teenagers, manifesting in a number of ways at different levels. The provision of emotional support enables students to engage in learning in a secure and respectful environment, which encourages the intrinsic pursuit of moral values and sensitivity to moral situations (Gholami and Tirri, 2012). Secondly, as moral exemplars, teachers internalize noble moral qualities and correct moral behaviors, thereby influencing the values and codes of conduct of students through their own conduct (Osman, 2019). This process enhances students’ attention and sensitivity to moral issues. Furthermore, the interactive dialog between teachers and students facilitates the exercise of moral thinking and the enhancement of moral sensitivity, enabling students to examine moral issues from different angles and cultivate an open and inclusive moral mentality (Van Der Leij et al., 2022). Conversely, teachers’ timely feedback and guidance mechanisms, whether positive encouragement or error correction, facilitate students’ comprehensive comprehension and internalization of moral norms, thereby strengthening their moral self-discipline and moral sensitivity (Dastgir and Fakhar-Ul-Zaman, 2023). Consequently, a favorable teacher–student relationship can advance the moral sensitivity of teenagers through emotional support, exemplar demonstration, interactive dialog, and feedback guidance.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is rooted in the socio-emotional support provided by teachers. Adolescents often navigate complex moral dilemmas during their formative years, and teachers who establish caring and trusting relationships may create a conducive environment for moral development (Lu et al., 2023; Reyes et al., 2012). Such relationships can enhance students’ awareness of ethical considerations and foster empathy toward others’ perspectives. Moreover, consistent positive interactions with teachers may influence adolescents’ self-concept and identity formation, thereby shaping their moral reasoning abilities (Wentzel, 2015). When students feel valued and respected by their teachers, they may be more inclined to internalize moral values promoted within the educational context (Coyle et al., 2022).

The supportive and trusting environment created by positive teacher–student relationships likely encourages students to reflect on ethical dilemmas and consider the perspectives of others. This aligns with Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, wherein interpersonal relationships are crucial for progressing toward higher levels of moral reasoning (Razak et al., 2022; Kurtines and Greif, 1974). Comparing our results with those of similar studies reveals consistent patterns across different educational contexts. For instance, Narinasamy and Mamat (2018) found that students who reported closer bonds with their teachers demonstrated greater empathy and moral reasoning abilities. Likewise, Altavilla et al., (2021) identified a positive correlation between teacher support and students’ ethical decision-making skills. These collective findings strengthen the argument that teacher–student relationships are pivotal in shaping moral sensitivity during adolescence.

By contextualizing our findings within existing literature and theoretical frameworks, we highlight both the consistency and advancements in understanding the intricate dynamics shaping moral development. Future research endeavors should continue to explore these dynamics comprehensively, thereby enriching our insights into effective strategies for promoting ethical awareness and behavior among young individuals.

The mediating effect of perceived social support and moral identity between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity in adolescents

This study provides robust empirical support for our second hypothesis (H2), indicating that perceived social support acts as a significant mediating factor in elucidating the relationship between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity among adolescents. Our findings underscore that the quality of teacher–student interactions play a crucial role in shaping adolescents’ moral awareness, with perceived social support serving as a mechanism through which these relationships exert their influence. The identification of perceived social support as a mediator advances our understanding of how supportive educational environments contribute to moral development during adolescence. When students perceive higher levels of support from their teachers, they may experience a greater sense of security and belonging within the school community, fostering their sensitivity to moral issues and ethical decision-making.

Consistent with our findings, previous research by Khan et al. (2024) demonstrated similar mediation effects, emphasizing the robustness of perceived social support as a mediator in educational settings. Perceived social support from teachers plays a crucial role in adolescents’ psychosocial well-being and moral understanding (Hellfeldt et al., 2020). When students perceive their teachers as supportive and caring, they are more likely to feel valued and understood within the educational context (Virat, 2022). This positive perception can enhance adolescents’ moral sensitivity by facilitating greater empathy, ethical reasoning, and consideration of moral principles in decision-making processes (Cingel and Krcmar, 2020).

Regarding the third hypothesis (H3), our findings supported that moral identity act as the intermediary through which teacher–student relationship impacts the development of moral sensitivity among adolescents. This finding underscores the importance of moral identity formation within the context of educational interactions. The findings indicate that the quality of teacher–student relationships are pivotal in shaping adolescents’ moral sensitivity, with moral identity acting as a mechanism through which these influences are transmitted. This aligns with social-cognitive theories that emphasize the role of interpersonal relationships in moral development (Bandura, 1986; Eisenberg, 2000). Specifically, when teachers establish supportive and respectful relationships with students, adolescents are likely to internalize these values into their moral identity, thereby enhancing their sensitivity to moral issues.

Several factors may contribute to the observed mediation effect. Firstly, teachers serve as role models whose behaviors and ethical standards adolescents may emulate (Wentzel, 2002). Positive interactions with teachers can foster a sense of moral agency and responsibility among students, influencing their moral reasoning and decision-making processes (Kohlberg, 1969). Secondly, the supportive environment created by strong teacher–student relationships may encourage open communication about moral dilemmas and ethical considerations, facilitating adolescents’ moral growth (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

The results of our study corroborated the fourth hypothesis (H4), which suggests a sequential mediation process in which perceived social support and moral identity jointly mediate the connection between the teacher and the student relationship and adolescent moral sensitivity. The sequential mediation model proposed in our study extends previous research by elucidating the specific mechanisms through which teacher–student relationships influence moral development in adolescents. By identifying perceived social support and moral identity as successive mediators, we highlight the importance of both emotional and cognitive processes in shaping moral sensitivity during adolescence.

Perceived social support serves as the initial mediator, wherein adolescents who perceive higher levels of support from their teachers experience greater emotional security and connectedness within the school environment (Cohen and Wills, 1985). This emotional foundation, in turn, fosters the development of a moral identity—a self-concept grounded in ethical values and principles (Hardy and Carlo, 2005). Moral identity, functioning as the second mediator in our model, reflects adolescents’ internalization of moral standards and their commitment to upholding these principles in their actions and decisions (Aquino and Reed, 2002). Through identification with morally exemplary figures, such as supportive teachers, adolescents integrate these values into their self-concept, thereby enhancing their sensitivity to moral issues and ethical dilemmas.

The chain mediation model proposed in our study advances understanding by elucidating the sequential processes through which teacher–student relationships influence moral sensitivity. This model underscores the dynamic interplay between interpersonal relationships, emotional experiences, and cognitive developments in shaping adolescents’ ethical awareness and decision-making capacities (Erikson, 1968).

Several factors contribute to the robustness of the observed chain mediation effects. Firstly, the quality of teacher–student relationships influences the emotional climate of the classroom, facilitating opportunities for supportive interactions and moral discussions (Hamre and Pianta, 2001). Such environments nurture adolescents’ perception of social support, fostering a sense of safety and belonging essential for moral identity formation (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Moreover, the educational context shaped by positive teacher–student relationships cultivates moral reflection and ethical reasoning among adolescents (Kohlberg, 1969). By engaging in dialogs about moral dilemmas and ethical responsibilities, students consolidate their moral identities and refine their sensitivity to moral issues within diverse social contexts.

The absence of a moderating effect of problematic social media use on the relationship between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity in adolescents

Contrary to our initial hypothesis (H5), our study found that problematic social media use does not moderate the positive influence of teacher–student relationships on moral sensitivity in adolescents. This indicates that despite the negative connotations associated with excessive social media use, its presence does not necessarily weaken the beneficial effects that strong interpersonal relationships in educational settings can have on moral development.

This finding contrasts with some prior research, which has often highlighted the disruptive role of excessive social media use in various aspects of youth development. For instance, studies like those conducted by Kross et al. (2013) suggest that problematic social media engagement can diminish the effectiveness of real-world relationships and educational outcomes. However, our results suggest that the foundational benefits of teacher–student relationships remain robust, capable of sustaining their positive impact on moral sensitivity, regardless of the level of social media use. This resilience of teacher–student relationships aligns with the findings of Wentzel (2002), who noted that the quality of direct interpersonal interactions within schools could override external influences, including digital ones.

According to compensatory media theory and multiple motivation theory, adolescents may overuse social media because of motives such as social demands and the desire to belong (Throuvala et al., 2019). However, such patterns of use are more related to their individual psychological characteristics and need rather than the influence of teacher–student relationships on adolescents’ moral sensitivity (Peris et al., 2020). For instance, adolescents may experience peer rejection (Xu et al., 2022; Demircioğlu and Göncü Köse, 2021) or family relationship risks.

It is also important to consider the complexity of social media’s impact on adolescents. Previous research indicates that the effects of social media can vary widely depending on usage type, content consumed, and individual differences among users (Valkenburg and Peter, 2013). In educational practice, there are significant differences in the frequency, mode, and preference of social media use among different students. Some students may make more use of social media for learning and socializing, while others may be more likely to indulge in gaming, entertainment, or consumption of undesirable information (Tremolada et al., 2022). In addition, it is often difficult for teachers in educational practice to fully monitor and guide students’ social media use, further adding to the complexity and uncertainty of this effect. Additionally, our study focused specifically on problematic use, characterized by addictive behaviors and negative consequences, which may not fully capture the broader spectrum of social media interactions. Future research should investigate different dimensions of social media use, such as passive versus active use, to better understand their potential moderating effects.

The absence of a moderating effect implies that interventions aimed at enhancing teacher–student relationships could be universally beneficial, regardless of adolescents’ social media habits. Educators and policymakers should prioritize fostering positive teacher–student relationships as a fundamental strategy for promoting moral sensitivity and overall well-being in adolescents.

In conclusion, while problematic social media use does not moderate the relationship between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity, the enduring positive impact of strong teacher–student relationships highlights their critical role in adolescent development. Further research is needed to explore the multifaceted interactions between social media use and adolescent development, considering various types and contexts of social media engagement.

Theoretical contribution and practical implications

The findings of this research are both meaningful and offer valuable insights from theoretical and practical standpoints. From a theoretical perspective, this study makes a noteworthy contribution by shedding light on the complex interplay between teacher and student relationships and adolescent moral sensitivity, thereby enhancing our understanding of the factors that influence moral development during this critical stage. Moral sensitivity, a pivotal aspect of moral development influencing ethical conduct and societal integration in young individuals, has been explored in the context of educational settings and social dynamics. Firstly, our findings establish a positive association between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity among Chinese adolescents aged 12–20 years. This direct relationship underscores the role of supportive educational environments in fostering moral awareness and ethical decision-making. Secondly, the study introduces perceived social support and moral identity as critical mediators in this relationship. Perceived social support acts as an intermediary mechanism through which positive teacher–student relationships enhance adolescents’ moral sensitivity. Furthermore, moral identity emerges as another mediator, reflecting how a strong teacher–student bond contributes to the internalization of moral values and principles among students. Moreover, the sequential mediation analysis reveals a nuanced pathway where teacher–student relationships influence moral sensitivity indirectly through the sequential mediation of perceived social support and moral identity. This sequential mediation model deepens our understanding of the underlying processes through which educational contexts shape moral development in adolescents. Additionally, the study’s exploration of problematic social media use as a potential moderator reveals that such usage does not significantly alter the positive impact of teacher–student relationships on moral sensitivity. This finding challenges assumptions about the pervasive negative effects of social media on adolescents’ moral development and suggests that positive educational relationships may offer a protective buffer against the potential adverse influences of social media. In sum, these contributions collectively advance the field of moral education by providing a comprehensive model that integrates relational, social, and individual determinants of moral sensitivity.

Our findings also have practical implications. Firstly, fostering supportive and respectful teacher–student relationships is crucial, as these relationships positively correlate with moral sensitivity. Educators should prioritize professional development programs aimed at enhancing teachers’ interpersonal skills and promoting a nurturing classroom environment. Secondly, interventions should focus on strengthening adolescents’ perceptions of social support from teachers and peers, recognizing its pivotal role as a mediator. Initiatives such as peer mentoring programs, counseling services, and extracurricular activities should be implemented to enhance social connectedness and emotional well-being. Thirdly, cultivating moral identity through educational programs can significantly enhance moral sensitivity. Integrating moral education into the curriculum should emphasize ethical decision-making, moral reasoning, and reflection on personal values, encouraging students to explore their beliefs and values in relation to societal norms and responsibilities. Fourthly, while concerns about social media’s negative effects are valid, our research indicates that strong teacher–student relationships can mitigate potential adverse impacts. Therefore, schools should focus on promoting healthy digital habits while simultaneously strengthening interpersonal relationships in the classroom. Digital literacy programs that teach responsible social media use, coupled with efforts to enhance face-to-face interactions, can offer a balanced approach. Lastly, policymakers should integrate findings from this study into educational policies and initiatives aimed at promoting holistic development in adolescents. This may include allocating resources for comprehensive school-based interventions that foster positive teacher–student relationships and support moral growth.

Limitations

This study faces several limitations. Firstly, the use of cross-sectional data provides only a snapshot of the relationship between teacher and student interactions and moral sensitivity, capturing temporal dynamics but potentially missing longitudinal changes. To establish causality and track developmental trajectories, future investigations should adopt longitudinal methodologies, following cohorts over extended periods. Secondly, reliance on self-report surveys introduces biases inherent in subjective participant perspectives, which may diverge from objective assessments. Future research should incorporate diverse sources of information, such as parental, peer, and educator perspectives, to offer a more comprehensive and unbiased understanding of how teacher–student relationships influence moral sensitivity. This multifaceted approach also offers the potential to identify and mitigate biases inherent in self-reported data. Thirdly, the study did not delve deeply into a variety of other factors that might influence moral sensitivity. To offer a more thorough understanding of the processes involved, future research should broaden its scope to include additional variables, such as cultural, ethnic, and neurobiological factors, which could further clarify the complex mechanisms that contribute to the development of moral sensitivity.

Conclusions

The present study investigated moral sensitivity in adolescents and explored its antecedent factors. It highlighted the role of the teacher–student relationship in fostering moral sensitivity among this demographic. Furthermore, the study identified perceived social support and moral identity as mediators in the relationship between teacher and student interactions and moral sensitivity in adolescents. The mediating pathway examined was as follows: teacher–student relationship → perceived social support → moral identity → moral sensitivity. Additionally, the research found that problematic social media use may moderate the association between teacher and student relationships and moral sensitivity. The positive effect of teacher–student relationships on moral sensitivity is not significantly influenced by problematic social media use. This study contributes significantly both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, it expands the current understanding of how teacher–student relationships influence moral sensitivity in adolescents by elucidating underlying mechanisms. Practically, the study integrates social and individual factors in nurturing moral sensitivity, offering a more nuanced perspective on adolescent development. Ultimately, these findings offer valuable insights for stakeholders interested in fostering moral sensitivity among adolescents.

Data availability

Participants were informed during the data collection process that their information would remain confidential and that no one outside the research team would have access to the data, so the datasets generated and analyzed in this study cannot be shared publicly as this was explicitly stated in the consent forms.

References

Abbasi-Asl R, Hashemi S (2019) Personality and morality: role of the big five personality traits in predicting the four components of moral decision making. Int J Behav Sci 13(3):123–128

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN (2015) Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Psychology Press, New York

Altavilla G, Manna A, Lipoma M (2021) Relevance of empathy in educational relationships and learning processes. J Phys Educ Sport 21:692–695

Amerstorfer CM, Freiin von Münster-Kistner C (2021) Student perceptions of academic engagement and student–teacher relationships in problem-based learning. Front Psychol 12:713057

Aquino K, Reed II A (2002) The self-importance of moral identity. J Personal Soc Psychol 83(6):1423–1440

Aquino K, Freeman D, Reed II A, Lim VK, Felps W (2009) Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: the interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. J Personal Soc Psychol 97(1):123–141

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs NJ 1986(23–28):2

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (2017) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal development. Psychol Bull 117:57–89

Biesta GJ (2015) Beyond learning: democratic education for a human future. Routledge, New York, p 176

Bock T, Samuelson PL (2014) Educating for moral identity: an analysis of three moral identity constructs with implications for moral education. J Character Educ 10(2):155

Bowlby J (1979) The bowlby-ainsworth attachment theory. Behav Brain Sci 2(4):637–638

Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. Am J Orthopsychiatr 52(4):664–678

Brezina T, Piquero AR (2017) Exploring the relationship between social and non-social reinforcement in the context of social learning theory. In: Social learning theory and the explanation of crime. Routledge, pp 265–288

Caban S, Makos S, Thompson CM (2023) The role of interpersonal communication in mental health literacy interventions for young people: a theoretical review. Health Commun 38(13):2818–2832

Chen C, Martínez RM, Cheng Y (2018) The developmental origins of the social brain: empathy, morality, and justice. Front Psychol 9:2584

Cingel DP, Krcmar M (2020) Considering moral foundations theory and the model of intuitive morality and exemplars in the context of child and adolescent development. Ann Int Commun Assoc 44(2):120–138

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98(2):310–357

Coyle S, Weinreb KS, Davila G, Cuellar M (2022) Relationships matter: the protective role of teacher and peer support in understanding school climate for victimized youth. In: Child & youth care forum, vol 51. Springer US, New York, pp 181–203

Dastgir G, Fakhar-Ul-Zaman DAA (2023) Unveiling the hidden curriculum: exploring the role of teachers in shaping values and moral lessons for students through the hidden curriculum beyond the classroom. Jahan-e-Tahqeeq 6(3):516–524

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268

Demircioğlu ZI, Göncü Köse A (2021) Effects of attachment styles, dark triad, rejection sensitivity, and relationship satisfaction on social media addiction: a mediated model. Curr Psychol 40(1):414–428

Deneault AA, Hammond SI, Madigan S (2023) A meta-analysis of child–parent attachment in early childhood and prosociality. Dev Psychol 59(2):236

Eisenberg N (2000) Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annu Rev Psychol 51(1):665–697

Erikson EH (1968) Identity: youth and crisis. Norton, New York

Fatima S, Dawood S, Munir M (2020) Parenting styles, moral identity and prosocial behaviors in adolescents. Curr Psychol 41:1–9

Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB (2009) Community violence: a meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Dev Psychopathol 21(1):227–259

García-Moya I, García-Moya I (2020) The importance of student–teacher relationships for wellbeing in schools. The importance of connectedness in student-teacher relationships: insights from the teacher connectedness project. Springer, Switzerland, pp 1–25

García-Rodríguez L, Redín CI, Abaitua CR (2023) Teacher–student attachment relationship, variables associated, and measurement: a systematic review. Educ Res Rev 38:100488

Gawronski B (2022) Moral impressions and presumed moral choices: perceptions of how moral exemplars resolve moral dilemmas. J Exp Soc Psychol 99:104265

Gholami K, Tirri K (2012) Caring teaching as a moral practice: an exploratory study on perceived dimensions of caring teaching. Educ Res Int 2012(1):954274

Gong X, Cai T, Dou F, Wang M (2022) Shyness and fear of missing out among university students: the mediating role of perceived social support and gender differences. Chin J Clin Psychol 42:1121–1125

Gui AKW, Yasin M, Abdullah NSM, Saharuddin N (2020) Roles of teacher and challenges in developing students’ morality. Univers J Educ Res 8(3):52–59

Guo B, Du F (2013) Study on the characteristics of moral sensitivity among middle school students. J Moral Educ Prim Second School 12(1):4–7

Hampden-Thompson G, Galindo C (2017) School–family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educ Rev 69(2):248–265

Hamre BK, Pianta RC (2001) Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Dev 72(2):625–638

Hardy SA, Carlo G (2005) Identity as a source of moral motivation. Hum Dev 48(4):232–256

Hellfeldt K, López-Romero L, Andershed H (2020) Cyberbullying and psychological well-being in young adolescence: the potential protective mediation effects of social support from family, friends, and teachers. Int J Environ Res public Health 17(1):45

Hu Z, Xiong M (2024) The relationship between relative deprivation and cyberbullying among university students: the mediating role of moral disengagement and the moderating role of moral identity. Psychol Dev Educ, 40, 346–356

Huang J, Zhao Y, Tang Y, Zhang H (2023) Neuroticism and adolescent problematic mobile social media use: a moderated mediation model. J Genet Psychol 184(5):372–383

Ibrahim A, El Zaatari W (2020) The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. Int J Adolesc Youth 25(1):382–395

Jiang Q (1999) Perceived social support scale (PSSS). In: Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H (eds.) Handbook of mental health assessment scales (revised edition). Chinese Mental Health Journal, Beijing, pp 131–133

Jiang Y (2018) Development of the adolescent problematic mobile social media use assessment questionnaire. Psychol Tech Appl 10:613–621

Jianga A, Shangb Q, Wen-Hsienc H, Wangd J (2022) A study on teacher-student interactions in STEAM inclusive educational assistance project to Cambodia Remote Rural Primary Schools. J Sci Educ 23(1):33–39

Kang X, Zhang W (2023) An experimental case study on forum-based online teaching to improve student’s engagement and motivation in higher education. Interact Learn Environ 31(2):1029–1040

Kara A, Rojas-Méndez JI, Turan M (2016) Ethical evaluations of business students in an emerging market: effects of ethical sensitivity, cultural values, personality, and religiosity. J Acad Ethics 14:297–325

Khan A, Zeb I, Zhang Y, Fazal S, Ding J (2024) Relationship between psychological capital and mental health at higher education: role of perceived social support as a mediator. Heliyon 10(8):E29472

Kohlberg L (1969) Stage and sequence: the cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In: Goslin DA (ed) Handbook of socialization theory and research. Rand McNally, pp 347–480

Kolhar M, Kazi RNA, Alameen A (2021) Effect of social media use on learning, social interactions, and sleep duration among university students. Saudi J Biol Sci 28(4):2216–2222

Kraaijeveld MI, Schilderman JBAM, van Leeuwen E (2021) Moral sensitivity revisited. Nurs Ethics 28(2):179–189

Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, Ybarra O (2013) Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One 8(8):e69841

Kurtines W, Greif EB (1974) The development of moral thought: review and evaluation of Kohlberg’s approach. Psychol Bull 81(8):453–470

Lapsley D, Hardy SA (2017) Identity formation and moral development in emerging adulthood. In: Padilla-Walker LM, Nelson LJ (eds) Flourishing in emerging adulthood: positive development during the third decade of life. Oxford University Press, pp 14–39

Li X (2024) Adolescent problematic social media use and interpersonal distress: the mediating role of social media fear of missing out. Chin J Clin Psychol 01:96–99

Lian B, Kristiawan M, Ammelia D, Primasari G, Anggung M, Prasetyo M (2020) Teachers’ model in building students’ character. J Crit Rev 7(14):927–932

Ling R (2012) Taken for grantedness: the embedding of mobile communication into society. MIT Press, Cambridge

Lu C, Huang Z, He H, Yiting E (2023) Teacher–student relationships and hope among rural adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Asia Pac J Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2023.2286199

Lu F, Fu S (2021) The impact of teacher-student relationships on the moral sensitivity of rural children: the mediating role of friendship quality. Chin J Special Educ 3:66–72

Luan L, Hong JC, Cao M, Dong Y, Hou X (2023) Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: a structural equation model. Interact Learn Environ 31(3):1703–1714

Malti T, Galarneau E, Peplak J (2021) Moral development in adolescence. J Res Adolesc 31(4):1097–1113

Marples R (2022) Moral sensitivity: the central question of moral education. J Philos Educ 56(2):342–355

Moreira P, Pedras S, Silva M, Moreira M, Oliveira J (2021) Personality, attachment, and well-being in adolescents: the independent effect of attachment after controlling for personality. J Happiness Stud 22:1855–1888

Narinasamy I, Mamat WHW (2018) Caring teacher in developing empathy in moral education. MOJES: Malaysian online. J Educ Sci 1(1):1–19

Narvaez D, Lapsley DK (2009) Moral identity, moral functioning, and the development of moral character. Psychol Learn Motiv 50:237–274

Osman Y (2019) The significance in using role models to influence primary school children’s moral development: pilot study. J Moral Educ 48(3):316–331

Peris M, de la Barrera U, Schoeps K, Montoya-Castilla I (2020) Psychological risk factors that predict social networking and internet addiction in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(12):4598

Pianta RC (1994) Patterns of relationships between children and kindergarten teachers. J Sch Psychol 32(1):15–31

Pinar WF (2019) What is curriculum theory? Routledge

Razak AA, Ramdan MR, Mahjom N, Zabit MNM, Muhammad F, Hussin MYM, Abdullah NL (2022) Improving critical thinking skills in teaching through problem-based learning for students: a scoping review. Int J Learn Teach Educ Res 21(2):342–362

Rest J, Thoma S, Edwards L (1997) Designing and validating a measure of moral judgment: stage preference and stage consistency approaches. J Educ Psychol 89(1):5

Reyes MR, Brackett MA, Rivers SE, White M, Salovey P (2012) Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. J Educ Psychol 104(3):700–712

Riedel PL, Kreh A, Kulcar V, Lieber A, Juen B (2022) A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(3):1666

Rullo M, Lalot F, Heering MS (2022) Moral identity, moral self-efficacy, and moral elevation: a sequential mediation model predicting moral intentions and behaviour. J Posit Psychol 17(4):545–560

Sabol TJ, Pianta RC (2012) Relationships between teachers and children. Handbook of psychology, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Savur SG (2022) Ethical decision-making—synthesizing SK Chakraborty’s classification of ethics with levels of moral judgement and the four-component model. In: Global perspectives on Indian spirituality and management: the legacy of SK Chakraborty (pp 107–121). Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore

Schipper N, Goagoses N, Koglin U (2023) Associations between moral identity, social goal orientations, and moral decisions in adolescents. Eur J Dev Psychol 20(1):107–129

Sisodia N, Bhambri S (2024) SOCIAL BONDS AND SELF PERCEPTION: EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL CONNECTEDNESS AND SELF CONCEPT IN YOUTH. Int J Interdiscip Approaches Psychol 2(4):993–1007

Snyder KS, Luchner AF, Tantleff-Dunn S (2024) Adverse childhood experiences and insecure attachment: the indirect effects of dissociation and emotion regulation difficulties. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 16(S1):S20

Sparks JR (2015) A social cognitive explanation of situational and individual effects on moral sensitivity. J Appl Soc Psychol 45(1):45–54

Su N, Wang HP (2022) The influence of students’ sense of social connectedness on prosocial behavior in higher education institutions in Guangxi, China: a perspective of perceived teachers’ character teaching behavior and social support. Front Psychol 13:1029315

Tan L, Li Q, Guo C (2022) The impact of teacher–student relationships on the academic engagement of left-behind children: a moderated mediation model. Stud Psychol Behav 20(6):782–789

Throuvala MA, Griffiths MD, Rennoldson M, Kuss DJ (2019) Motivational processes and dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use among adolescents: a qualitative focus group study. Comput Hum Behav 93:164–175

Tremolada M, Silingardi L, Taverna L (2022) Social networking in adolescents: time, type and motives of using, social desirability, and communication choices. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):2418

Valkenburg PM, Peter J (2013) The differential susceptibility to media effects model. J Commun 63(2):221–243

Van Der Leij T, Avraamidou L, Wals A, Goedhart M (2022) Supporting secondary students’ morality development in science education. Stud Sci Educ 58(2):141–181

Virat M (2022) Teachers’ compassionate love for students: a possible determinant of teacher–student relationships with adolescents and a mediator between teachers’ perceived support from coworkers and teacher–student relationships. Educ Stud 48(3):291–309

Wang X (2023) Exploring positive teacher–student relationships: the synergy of teacher mindfulness and emotional intelligence. Front Psychol 14:1301786

Wang X, Yang L, Yang J, Wang P, Lei L (2017) Trait anger and cyberbullying among young adults: a moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and moral identity. Comput Hum Behav 73:519–526

Wentzel KR (2002) Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev 73(1):287–301

Wentzel KR (2015) Implications for the development of positive student identities and motivation at school. In: Self-concept, motivation and identity: underpinning success with research and practice. Information Age Publishing, Inc., Charlotte, pp 299–337

Wentzel KR (2002) Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev 73:287–301

Wilke J, Eilts J, Bäker N, Goagoses N (2024) Morality in moderation: profiles of moral self and behavioral problems among children. Deviant Behav 45:1–15

Wu G, Zhang L (2022) Longitudinal associations between teacher–student relationships and prosocial behavior in adolescence: the mediating role of basic need satisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):14840

Wyer Jr RS, Srull TK (2014) Memory and cognition in its social context. Psychology Press, New York

Xiang Y, Cao Y, Dong X (2020) Childhood maltreatment and moral sensitivity: an interpretation based on schema theory. Personal Individ Differ 160:109924

Xu XP, Liu QQ, Li ZH, Yang WX (2022) The mediating role of loneliness and the moderating role of gender between peer phubbing and adolescent mobile social media addiction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(16):10176

Yang Q, van den Bos K, Zhang X, Adams S, Ybarra O (2022) Identity lost and found: self-concept clarity in social network site contexts. Self Identity 21(4):406–429

Yang S, Zhu X, Li W, Zhao H (2023) Associations between teacher–student relationship and externalizing problem behaviors among Chinese rural adolescent. Front Psychol 14:1255596

Zheng F (2022) Fostering students’ well-being: the mediating role of teacher interpersonal behavior and student-teacher relationships. Front Psychol 12:796728

Zhou H, Long L (2004) A statistical test and control method for common method bias. Adv Psychol Sci 12(6):942–950

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess 52(1):30–41

Zimmer JC (2022) Problematic social network use: its antecedents and impact upon classroom performance. Comput Educ 177:104368

Zou H, Qu Z, Ye Y (2007) Teacher–student relationships among primary and secondary school students and their school adjustment. Psychol Dev Educ 23(4):77–82

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Education Sciences Planning Program: Research on the Mechanisms of the Development and Cultivation Paths of Moral Sensitivity in Adolescents (grant ID: BEA230082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuping Yang: conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing—original draft. Hengda Zhang: writing—original draft. Xingchen Zhu: methodology, software, and writing—review and editing. Wencan Li: methodology, software, and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Education at Liaoning Normal University (Ethics approval number: LSDJYXB2024036) on March 20, 2024. This research complies with all relevant ethical guidelines, including the institutional protocols for research involving human participants and the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics approval covered all aspects of the study, including participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis. All procedures were conducted in line with these regulations to ensure the protection of participants’ rights, confidentiality, and informed consent throughout the research.

Informed consent

This study obtained written informed consent from both participants and their legal guardians between April 8, 2024, and April 26, 2024, facilitated by trained research assistants prior to data collection in May 2024. Given the involvement of minors, special care was taken to ensure that consent was appropriately secured. Legal guardians were provided with clear information about the study’s objectives, procedures, and participants’ rights, highlighting the voluntary nature of participation and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Additionally, minors received age-appropriate explanations to help them understand the study’s purpose and their role. Both legal guardians and minors signed the consent forms to confirm their understanding and agreement. Participants were assured that their anonymity and confidentiality would be strictly protected, with no personally identifiable information collected. The consent covered participation in the study, the use of collected data for research purposes, and permission to publish the findings. As a token of appreciation, participants received a small gift (e.g., a pen or card), regardless of whether they completed the study. This gift was provided solely as a gesture of gratitude, not as an incentive, ensuring the voluntary nature of participation was preserved.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Zhang, H., Zhu, X. et al. Associations between teacher and student relationship and moral sensitivity among Chinese adolescents in the digital age: the chain mediation effect of perceived social support and moral identity. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04632-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04632-2