Abstract

Currently, sustainable supply chain management practices have become an important strategy for firms to improve performance and gain competitive advantage. However, there is a current debate over the performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management practices. Additionally, the role of stakeholder pressure is frequently overlooked. Drawing on Natural Resources-Based View and Stakeholder Theory, this study aims to elucidate the ambiguous connection between sustainable supply management, sustainable process management, stakeholder pressure and performance, and investigate the mediation role of sustainable process management and the moderation effect of stakeholder pressure. Our analysis, based on data collected from 235 Chinese manufacturing firms, reveals significant insights. First, stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and performance, while negatively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. Second, sustainable process management has a complete mediation effect on the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. The conclusion not only explains the inconsistent relationship between sustainable supply chain management practice and performance, but also reveals clearly the relationship between sustainable supply management and sustainable process management. Besides, it also highlights the difference in performance outcomes of sustainable supply management and sustainable process management under stakeholder pressures, and has valuable guidance to the practice of sustainable supply chain management in Chinese manufacturing firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social and environmental concerns have garnered widespread attention within both business and academic circles. More than 3000 large corporations endure economic losses amounting to as much as $2 trillion due to issues encompassing resource wastage, environmental degradation, and the fulfillment of firm social responsibilities (Sutherland et al., 2016). Manufacturing firms, in particular, are facing severe economic and environmental pressures (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020; Toke & Kalpande, 2024). These issues have sparked continuous attention from governments and the public, compelling firms to implement sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) practices in anticipation of gaining novel competitive advantages(Sánchez-Flores et al., 2020). However, The outcomes of SSCMimplementation are not always satisfactory, and firms often fail to receive the desired returns from the adoption of SSCM practices (Dai et al., 2021).

SSCM practices are considered a complex, comprehensive, and dynamically intersecting system engineering to address bidirectional pressures and challenges from both external and internal sources (Wiredu et al., 2024). Zhu et al. (2012) emphasize that internal and external sustainable supply chain practices interact and work together to achieve coordinated economic, environmental, and social development. Therefore, this paper approaches sustainable supply chains from both internal and external perspectives, dividing them into sustainable supply management and sustainable process management. The primary purpose of implementing SSCM practices is to enhance performance (Feng et al., 2018). The performance of sustainable supply chains typically includes environmental, social, and economic performance (Zhu et al., 2013), and Abdallah & Al-Ghwayeen (2020) suggest that it should also include operational performance. Thus, to comprehensively analyze and deeply understand the performance outcomes of SSCM practices, this paper categorizes them into environmental, social, economic, and operational performance.

There is still controversy in current research regarding the relationship between SSCM practices and performance (Balon, 2020; Yadav et al., 2023). Most scholars believe that SSCM practices can effectively help firms address social and environmental issues, thereby enhancing competitiveness and bringing about positive economic performance (Paulraj et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2014). However, other scholars question this conclusion. Hahn et al. (2010) and Green et al. (2015) maintain that sustainability or green supply chain management practices have a negative impact on firm profitability and financial performance. Gopal & Thakkar (2016) and Zhu et al. (2012) argue that there is no clear positive relationship between SSCM practices and operational performance, and firms lack sufficient motivation to implement green supply chain management practices. The inconsistent relationship between SSCM practices and performance can be attributed to two main reasons.

Firstly, the relationships among dimensions of SSCM practices are unclear. Most studies posit that sustainable process management has a positive impact on sustainable supply management, such as Gavronski et al. (2011) finding that internally standardized green manufacturing process capabilities promote the development of supplier management capabilities. Gualandris & Kalchschmidt (2014) believe that firm sustainable process management is a prerequisite for sustainable supply management. However, a minority of studies suggest that sustainable supply management can react to sustainable process management (Sanders & Premus, 2005), as Vachon (2007) proposes that collaboration with supply chain partners can facilitate product- or process-based improvements. Secondly, environmental variables have been overlooked in the study of the relationship between SSCM practices and performance (Paulraj et al., 2017), particularly the contingent effects of stakeholder pressure (Wolf, 2014).Current research primarily regards stakeholder pressure as antecedent variable or driving factor, such as Awan et al. (2017) finding that stakeholders influence key resources needed by firms, thereby affecting SSCM practices and sustainable development performance. Truant et al. (2023) believes that the effective promotion of sustainable supply chain practices can be achieved by enhancing the transparency of the supply chain and expanding the impact of stakeholder pressure on firms.

Based on the above analysis, this paper attempts to explain the inconsistent relationship between SSCM practices and performance. Simultaneously, it aims to understand the roles of stakeholder pressure and sustainable process management from a comprehensive and complete perspective, seeking to address the following questions: (1) How does stakeholder pressure moderate the relationship between sustainable supply management, sustainable process management, and performance? (2) How does sustainable process management mediate the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance? The answers to these questions help to understand the relationships between stakeholder pressure, SSCM practices (sustainable supply management and sustainable process management), and performance (social, environmental, operational, and economic performance). This study also contributes to enriching and improving research related to SSCM practices, furnishing guidance for firms implementing SSCM practices.

Theoretical foundation and research hypotheses

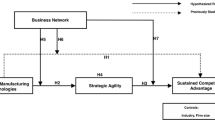

This section first introduces stakeholder theory and the natural resource-based view theory. Building upon theory foundation, Sections Moderating Role of Stakeholder Pressure and Mediating Role of Sustainable Process Management present research hypotheses and theoretical models concerning the relationships between sustainable supply management, sustainable process management, stakeholder pressure, and performance. This part not only provides theoretical support for subsequent empirical analysis and hypothesis testing, ensuring the coherence and consistency of the research, but also help understand the overall framework and logical structure of the study.

Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory posits that government agencies, political groups, industry associations, unions, communities, suppliers, employees, and customers, among others, participate in and influence a firm’s decision-making. The status of stakeholders arises from their ability to influence the firm and other stakeholders (Parmar et al., 2010). In recent years, stakeholder theory has been applied to complex supply chain management (Genovese et al., 2013). Park-Poaps & Rees (2010) argue that to meet the expectations of different stakeholders, firms must not only consider a wide network of participants in their strategy to ensure the profitability and survival of the business but also avoid compromising their operational qualifications by contravening labor and human rights standards. Furaiji et al. (2012) find that when firms identify consumer preferences for environmental friendliness, they signal the market with environmentally friendly products and services, promoting the formation of a green and environmentally friendly industrial ecosystem. Justine Marty et al. (2023) also demonstrated that the involvement of stakeholders such as customers and consumers can make supply chains more sustainable. Stakeholders hold different key resources needed by the firm, and decisions must consider stakeholder demands and accept their supervision(Jagriti et al., 2022). Therefore, stakeholder pressure can affect the effectiveness of SSCM practices.

The Natural Resource-Based View theory

The Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV), proposed by Hart (1995), addresses the shortcomings of traditional resource-based theory in neglecting the role of the external natural environment. It emphasizes that a firm’s development is not only constrained by internal resources but also by the availability and cost of external natural resources (Hart & Dowell, 2011). The theory indicates that a firm’s ability to coordinate the management of internal and external natural resources is a key factor in determining sustainable competitive advantage. Simultaneously, it suggests that preventing environmental pollution, managing products, and facilitating sustainable development can help firms gain irreplaceable sustainable competitive advantages, ultimately enhancing various aspects of performance (Sarfraz et al., 2023). Shi et al. (2012) develop a green supply chain management model based on the NRBV, and explain the relationship between driving factors and relevant performance indicators. Shibin et al. (2020) based on the NRBV, explored the impact of institutional pressure, top management commitment, and strategic resources on social, environmental, and economic performance. Therefore, the NRBV helps to elucidate the connection between the internal and external management of sustainable supply chains, and the varying effects that each has on performance.

Moderating Role of Stakeholder Pressure

Since ecological deterioration and social discrepancy are intensifying, multiple stakeholders are driving companies to incorporate sustainability in their supply chains (Siems et al., 2023). At the same time, stakeholders harbor expectations regarding the ultimate outcomes of sustainable supply chain management, and the pressure resulting from these expectations is integrated into the process of sustainable supply management (Wolf, 2014). High stakeholder pressure leads firms to demand higher environmental protection and social responsibility from suppliers (Wu et al., 2024), prompting a more detailed assessment of the environmental and social sustainable development capabilities of suppliers. This, in turn, reduces the negative external effects resulting from supplier environmental pollution and social responsibility lapses. When stakeholder pressure is low, attention to supplier management is diminished, potentially leading to neglect of suppliers’ environmental protection and social responsibility capabilities. This may not only cause accidents in the environmental and social aspects but also reduce the flexibility of supplier management, ultimately decreasing firm performance. Wolf (2014) find that shareholder pressure increases firms’ control over suppliers, thus enhancing sustainable development performance. Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and social performance

H2: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and environmental performance

H3: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and operational performance

H4: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and economic performance

During the implementation of sustainable process management, high stakeholder pressure compels firms to prioritize requirements related to environmental-friendly products, sustainable processes, and workers’ human rights and labor conditions. On one hand, firms will actively undertake environmental protection and social responsibility, enhancing social and environmental performance by optimizing product process designs and improving production processes (Beske & Seuring, 2014; Busse, 2016). On the other hand, stakeholders will provide key resources to help firms restructure outdated production processes, optimize production management systems, enhance turnover speed, and decrease production operation costs, ultimately improving economic and operational performance. Conversely, when stakeholder pressure is low, firms may neglect environmental protection and social responsibility, potentially leading to inefficient production processes and a lack of attention to worker working conditions, negatively impacting social performance. Bhatia & Jain (2013) believe that under high consumer environmental concerns, firms enhance their market competitiveness by increasing the marketing and publicity of eco-friendly products, elevating their green technology standards. Conversely, when consumer environmental concerns are low, firms may neglect green concepts and lack motivation to produce environmentally friendly products. Following this analysis, the subsequent hypothesis is posited:

H5: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and social performance

H6: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and environmental performance

H7: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and operational performance

H8: Stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and economic performance

Mediating Role of Sustainable Process Management

A firm is a collective composed of various intangible and tangible resources (Wernerfelt, 1984), and the development of its internal management depends to a certain extent on the resources provided externally. Suppliers, recognized as one of the most influential external resources shaping a firm’s development (Busse et al., 2016), exert an impact on sustainable process management through two primary avenues. First, strong collaborative relationships with suppliers can augment internal management flexibility (Vachon & Klassen, 2008) and reduce the costs associated with internal management (Ageron et al., 2012). Leveraging these established and robust cooperative relationships significantly enhances the efficiency of internal process management. Second, suppliers, as a primary driver of technological innovation (e.g., pollution control technologies) (Green et al., 1998), engage in the development of environmentally friendly materials and technologies. To align with the resources provided by suppliers, firms may transform and optimize their internal processes or products environmentally, ultimately enhancing sustainable process management. Vachon & Klassen (2006) suggest that through good cooperation with suppliers and customers, firms can effectively improve internal green supply chain practices. Therefore, sustainable supply management can provide favorable resource and external relationship conditions, promoting internal optimization and innovation, thereby benefiting sustainable process management. Then, sustainable process management will affect performance in sequence. On one hand, effective environmental management can enhance environmental performance by reducing resource waste, minimizing harmful substance emissions, and promoting sustainable product reuse (Beske & Seuring, 2014). It can also indirectly improve workshop environments, reducing damage to worker health and minimizing pollution emissions to the local environment, thus gaining a good social reputation (School of Management et al., 2019). On the other hand, scientifically reasonable processes and management systems can address issues such as inadequate production efficiency and an inability to respond promptly to market demands. They can also increase a firm’s resource utilization rate, effectively addressing resource waste and waste emissions. This study posits that the impact of sustainable supply management on performance is sequential. Sustainable supply management influences performance through sustainable process management, affecting social, environmental, operational, and economic performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Sustainable process management mediates the relationship between sustainable supply management and social performance

H10: Sustainable process management mediates the relationship between sustainable supply management and environmental performance

H11: Sustainable process management mediates the relationship between sustainable supply management and operational performance

H12: Sustainable process management mediates the relationship between sustainable supply management and economic performance

In summary, this study proposes the theoretical model shown in Fig. 1. This model includes seven structural variables: sustainable supply management (SSM), sustainable process management (SPM), social performance (SCO), environmental performance (EMP), operational performance (OPE), economic performance (ECO), and stakeholder pressure (SP).

Methodology

To investigate the relationship between sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance, as well as to analyze the role of stakeholder pressure in this relationship, we collected cross-sectional data through questionnaire survey and employed SEM.

Study design

We first elucidated the concepts and implications of relevant variables, including sustainable supply chain management practices, stakeholder pressure, and organizational performance. Subsequently, we selected established and validated scales from high-quality literature to develop a preliminary research questionnaire, and employ a systematic approach that included translation, back-translation, and expert discussions. Then, we revised the questionnaire multiple times by checking for completeness, enhancing clarity, and gathering feedback from enterprises through field visits, which resulted in the second version of the questionnaire. Finally, we validated and revised the questionnaire through a pilot survey to ensure precise wording and clear meanings, ultimately confirming the final version. This comprehensive process ensured the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, providing a solid foundation for subsequent data collection and analysis.

China, renowned for its robust economic growth, abundant data resources, and favorable conditions for manufacturers to launch extensive successful sustainable practices, stands out as an ideal location for data collection. Considering the time and economic costs associated with the questionnaire survey, as well as the uneven development of the manufacturing industry, we strategically selected representative firms from Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shaanxi, and Beijing for questionnaire distribution. We randomly selected sample companies from government directories and identified their CEOs, vice presidents/directors, operations managers, and supply chain managers as respondents, as they are likely to be familiar with SSCM strategy and operation. We sent out the questionnaires along with cover letters that provided detailed descriptions of our research objectives. To enhance the response rate, we adopted the method suggested by Frohlich (2002), where we made follow-up phone calls to potential respondents who had not replied to the survey after one month. Among the 720 successfully distributed questionnaires, a total of 235 usable responses were obtained, yielding a satisfactory overall response rate of 32.64%. Table 1 displays that the samples encompass different types of firms, including state-owned and private companies, with variations in size and ownership structures, and represents a wide spectrum of industries, such as food, textiles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and communication, ensuring a high level of representativeness.

In empirical research, cross-sectional data are widely used due to their ease of access and immediate reflection of current conditions, but their limitation lies in the difficulty of establishing temporal causality. Drawing on the research by Maier et al. (2023), we strive to mitigate the limitations of cross-sectional data studies by enhancing the verifiability of our research through detailed and transparent reporting, ensuring the appropriateness of sampling methods to strengthen sample representativeness, and adopting a clear and structured perspective to more comprehensively understand the relationships between variables. We conducted a reliability test on the sample data. Firstly, we performed a homogeneity test to analyze the consistency of data obtained from paper questionnaires and emails. We employed the chi-square test to determine whether there were significant differences in the collected questionnaire data between the two delivery methods. Additionally, we selected three questionnaire items related to respondents’ age, position, and education level for the chi-square test. The results showed no significant differences between the data collected through the two delivery methods for the three items. This indicates that the data collected from paper questionnaires and emails are from the same population and can be combined for analysis. Secondly, following Lambert et al. (1978) suggestion, we divided the sample into two groups: questionnaires collected after reminders (non-respondents) and questionnaires collected without reminders (respondents) based on the chronological order of the survey. We then used independent sample t-tests to compare whether there were significant differences in the means of sample characteristic variables (such as position, sales volume, ownership form, etc.) and key variables (such as stakeholder pressure, etc.) between the two groups. Ultimately, the results of the one-way t-test showed that all variable indicators were not significant at the 0.05 level, indicating no significant differences in various variables. Therefore, this study’s data does not suffer from serious non-response bias (Swink & Song, 2007).

Measurement Indicators

The measurement indicators for the variables in this study mainly come from established questionnaires. However, considering the differences in social and cultural backgrounds between foreign countries and China, we made specific adaptive modifications and adjustments to the indicators tailored to the Chinese context. The items used Likert scales, with scores ranging from 1 to 7 reflecting respondents’ agreement with the items. After the reliability and validity evaluation, we add the scores of each item in each variable and calculate the average value as their measure, and take the annual sales of the enterprise as the control variable in the concrete model.

The core content of the literature questionnaire includes three parts. The first part consists of measurement items for the SSCM practice dimension, setting two dimensions and six items, including sustainable supply management and sustainable process management. Sustainable supply management includes supplier assessment and supplier cooperation, and its measurement indicators mainly come from Gualandris & Kalchschmidt (2014). The main indicators of sustainable process management source from Gualandris & Kalchschmidt (2016). The second part involves the design of measurement items for stakeholder pressure, including three items, with measurement indicators coming from Sarkis et al. (2010)‘s research. The third part includes measurement items for the performance dimension, including four dimensions and thirteen items—social, environmental, operational, and economic performance. The measurement indicators for environmental performance mainly come from Vachon & Klassen (2008), and the measurement indicators for social performance mainly refer to the research by Amjad et al. (2017). Operational and economic performance are used to measure the speed of firm response to consumer demand, punctuality of delivery, inventory turnover rate, profitability, and cost. The measurement indicators for these two dimensions mainly draw on the research by Flynn et al. (2010).

Reliability and Validity Analysis

Following Fornell & Larcker (1981), this study adopted Cronbach’s alpha values to test reliability. As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables reached the threshold of 0.7, indicating that each variable involved in this study has good reliability(Murtagh & Heck, 2012). At the same time, we found that the construct reliability (CR) values for each latent variable ranged from 0.81 to 0.92, all exceeding 0.8, further confirming the reliability of each variable in this study (Kerlinger et al., 2000).

Additionally, this study conducted tests for content validity, convergence validity, and discriminant validity. Firstly, in formulating the questionnaire, we prioritized selecting measurement indicators from authoritative studies and invited experts and scholars in related fields to conduct thorough evaluations and make iterative modifications to the questionnaire. Therefore, we believe that the questionnaire used in this study has strong content validity.

Secondly, for convergence validity, we can see from Table 2 that the loading factors of each corresponding indicator for each latent variable are greater than 0.6, indicating that each indicator corresponding to each latent variable has high representativeness. Additionally, the CR values for each latent variable are all greater than 0.8, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values are all greater than 0.5. Meanwhile, χ^2/DF = 1.388, RMSEA = 0.041, SRMR = 0.037, NFI = 0.930, IFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.979. All of these fit indices meet the established threshold, indicating an excellent fit and ensuring convergence validity. Finally, for discriminant validity, as seen in Table 3, the HTMT values between each latent variable are all less than 0.9, indicating that the HTMT test passed, and there is good independence between latent variables (Henseler et al., 2015). Furthermore, as shown in Table 4, the AVE values are the maximum in each row, and the square root of AVE is greater than the correlation coefficient between variables, suggesting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

In addition, we evaluated a potential endogeneity by applying the Gaussian copula approach (Hult et al., 2018). As a first step, the Gaussian copula technique requires that the regressors have nonnormal distributions. Both the Shapiro–Wilk test and the Anderson–Darling test showed that the distributions of SSM and SPM were not normal (p < 0.05; Table 5). Next, we find none of the copula terms was statistically significant at the 5% probability of error level in Table 6, indicating low risks of possible endogeneity issues(Becker et al., 2022).

Then, we check all combinations of Gaussian copulas included in the models. The results in Table 6 show none is significant, suggesting that a potential endogeneity issue did not exist in this study.

Hypothesis Testing and Results

Main Effects and Moderating Effects Testing

This study used structural equation modeling to test the hypotheses and the theoretical model. The results in Table 7 show that sustainable supply management significantly positively influences sustainable process management (β = 0.82, p < 0.01). However, its impact on social performance (β = 0.13, p > 0.05), environmental performance (β = 0.20, p > 0.05), operational performance (β = 0.03, p > 0.05), and economic performance (β = 0.6, p > 0.05) is not significant. Sustainable process management has a significant positive impact on social performance (β = 0.20, p < 0.001), environmental performance (β = 0.17, p < 0.05), operational performance (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), and economic performance (β = 0.17, p < 0.01). Simultaneously, stakeholder pressure has a significant positive impact on social performance (β = 0.84, p < 0.01), environmental performance (β = 0.79, p < 0.01), operational performance (β = 0.73, p < 0.01), and economic performance (β = 0.85, p < 0.01).

H1-H4 predicted the moderating effect of stakeholder pressure on sustainable supply management and performance. As shown in Table 7, the interaction between stakeholder pressure and sustainable supply management on social performance (β = −2.483, p < 0.001), environmental performance (β = −2.532, p < 0.001), there were significant negative effects on business performance (β = −2.294, p < 0.001) and economic performance (β = −2.331, p < 0.001), suggesting a negative moderating effect of stakeholder pressure, contrary to our hypothesis, which does not support H1-H4. H5-H8 assessed the moderating effect of stakeholder pressure on sustainable process management and performance. As shown in Table 7, the interaction between stakeholder pressure and sustainable process management had significant positive effects on social performance (β = 3.31, p < 0.001), environmental performance (β = 3.127, p < 0.001), business performance (β = 2.974, p < 0.001) and economic performance (β = 2.936, p < 0.001), this suggests that stakeholder pressure has a positive moderating effect, which supports H5-H8.

Mediation Effects Testing

This study used the Bootstrapping method to test the mediation effects, referring to the research by Zhao et al. (2010). H9-H12 investigated the relationship between sustainable process management and performance within the context of sustainable supply management. The results are shown in Table 8, and the indirect effects of sustainable supply management and social, environmental, operational, and economic performance are 0.20, 0.14, 0.19, and 0.18, respectively. The Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for these indirect effects do not include 0, indicating that sustainable process management has significant mediating effects on the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. Additionally, the Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the direct effects of sustainable supply management on social, environmental, operational, and economic performance all include 0. Therefore, we believe that sustainable process management has a complete mediating effect on the relationship between sustainable supply management and social, environmental, operational, and economic performance. That supports our hypothesis H9-H12. In summary, the main and mediating effects are supported, with the results of hypothesis testing presented in Table 9.

Discussion

Discussion on the Moderating Role of Stakeholder Pressure

Our finding reveals that stakeholder pressure negatively moderates the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. This aligns with the findings of Siems et al. (2023), and they emphasize the complexity of stakeholder pressure, noting that excessive pressure can result in adverse effects, and thereby illuminated the significance and role of stakeholders within sustainable supply chain management. On the one hand, from the perspective of external relations in SSCM practice, establishing and maintaining good supplier relationships require significant resources and costs (Wang et al., 2018). On the other hand, coordinating with external suppliers is challenging, and short-term effectiveness is not guaranteed (Clarkson, 1995). It is difficult to balance the demands of other stakeholders when coordinating with suppliers. The heightened pressure exerted by stakeholders compels firms to institute elevated environmental protection standards and shoulder augmented social responsibility obligations (Phillips & Caldwell, 2005). Consequently, firms are prompted to prioritize the assessment of suppliers based on their proficiency in fulfilling social responsibility and environmental protection during development and evaluation processes (Wolf, 2014). Nonetheless, this elevation in standards substantially augments cost pressures on suppliers, thereby intensifying the challenges associated with coordination between companies and suppliers (Busse, 2016). Consequently, there is a notable escalation in coordination costs (Dash et al., 2018).

In addition, different stakeholders have different demands and expectations, often difficult to coordinate under high pressure. For example, consumers may be more concerned about the environmental performance of products and corporate social responsibility, while investors may be more concerned about corporate economic performance and profitability (Haleem et al., 2022). When these demands and expectations are not fully consistent with the enterprise’s sustainable supplier management strategy, it may lead to conflicting pressure from stakeholders on the enterprise, thus to a certain extent, the impact of sustainable performance (Siems et al., 2023).Conversely, when stakeholder pressure is low, firms can focus more on maintaining relationships with suppliers, exchanging environmental information and technology, and collaboratively developing environmentally friendly products to meet market needs, and the contradiction of each stakeholder pressure is not obvious. Consequently, the environmental, social, operational, and economic performance of firms are all improved.

Our study results also indicate that stakeholder pressure positively moderates the relationship between sustainable process management and performance. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Adomako & Tran (2022), and they maintain that stakeholder pressure strengths the relationship between sustainable initiatives and innovation. Sustainable process management serves as an internal mechanism for firms to enhance their social and environmental performance (Gualandris & Kalchschmidt, 2014; Gualandris et al., 2015). Firms do not need to divert their efforts to deal with external suppliers, allowing them to better respond to the demands and expectations of customers, shareholders, and other stakeholders. When stakeholder pressure is high, internal stakeholders and employees become drivers of sustainable process management (Yu & Ramanathan, 2015). Shareholders not only focus on costs but also value other factors that promote the development of the firm, such as external reputation (Meixell & Luoma, 2015). Employees, due to a good working environment and green production processes, can ensure their health and other rights, and pay more attention to internal environmental and social responsibility management (Ahmed et al., 2020). Therefore, under high pressure, firms can focus on meeting the sustainability requirements of various stakeholders and quickly resolving environmental and social responsibility issues within the firm (Hyatt & Berente, 2017). In addition, effective process management improves the turnover capability of firms, reduces production costs, and ultimately improves performance (Yu & Ramanathan, 2015). When stakeholder pressure is low, the overall emphasis on sustainable development within the firm decreases. Although internal coordination is easier, it may lead to neglect of environmental aspects in the implementation of sustainable process management, causing issues such as resource waste, waste emissions, and neglect of workers’ rights and interests. This reduces environmental and social benefits.

Mediating Role of Sustainable Process Management

Our results show that sustainable process management plays a mediating role in the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. This finding is consistent with the research results of Gualandris & Kalchschmidt (2014), which suggests that sustainable supply management can have an indirect impact on manufacturing firm performance through sustainable process management. Thus, the influence of sustainable supply management on performance is sequential, initially affecting sustainable process management and subsequently exerting a further impact on performance. Suppliers are the most important external factors and resources affecting the development of firms (Busse et al., 2016). Based on the NRBV, only when firms have enough external resources in implementing sustainable supply management can internal management develop. Vachon & Klassen (2006) believe that cultivating effective collaboration with suppliers proves advantageous for the internal development of firms.

As a means for firms to internally implement sustainable management, sustainable process management is closely related to environmental management and social responsibility management within the firm (Gualandris & Kalchschmidt, 2014). Firstly, effective environmental management can not only reduce resource waste, harmful substance emissions, and increase the sustainable use of products (Beske & Seuring, 2014), but also reduce the harm of operational environments to workers’ health by improving workshop conditions (Busse et al., 2016). Secondly, internal social responsibility management can guarantee the health and safety of workers through health and safety certification, and also promote communication and development with the local community through social activities, enhancing firm social influence and satisfaction (Busse et al., 2016). This ultimately affects the environmental, social, economic, and operational performance of the firm.

In addition, when firms engage in sustainable supply management, they will adjust internal processes according to the needs of supplier cooperation. By establishing scientific and robust production and operation processes, as well as improving management practices, firms can enhance their performance and competitiveness (Nadarajah & Kadir, 2014). Rigorous and refined production processes expedite production speed and enhance product quality. Enhanced management practices tackle challenges like inadequate production efficiency and delayed responses to market demands, aiding firms in improving consumer demand responsiveness and delivery speed (Vom Brocke et al., 2012). Moreover, improved production and operation processes increase resource utilization efficiency, effectively address issues such as resource waste and emissions, and in turn, reduce waste disposal costs, increases product sales, and ultimately contributes to improved overall performance. Thus, sustainable supply management indirectly influences economic, operational, environmental, and social performance through sustainable process management.

Conclusion and Insights

This study, based on the NRBV and stakeholder theory, explored the relationships among SSCM practices, performance, and stakeholder pressure. It particularly analyzed the moderating role of stakeholder pressure and the mediating role of sustainable process management. Our findings reveal two primary insights. First, stakeholder pressure enhances the relationship between sustainable process management and performance but inhibits the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. This moderating effect not only explains the inconsistency in the relationship between SSCM practices and performance but also expands the application of stakeholder theory in SSCM practices. Second, sustainable process management exhibits a complete mediating effect on the relationship between sustainable supply management and performance. This clarifies the contradictory relationship between sustainable supply management and sustainable process management, providing strong evidence for the positive impact of sustainable supply management on sustainable process management. Moreover, it elucidates the indirect impact of sustainable supply management on performance, offering further insights into the varied pathways through which sustainable supply management influences performance.

In addition to theoretical contributions, this study provides practical implications for businesses. In contexts of high stakeholder pressure, firms should actively promote sustainable process management, focusing on internal SSCM practices. They should respond to stakeholder demands for environmentally friendly products and workers’ rights by optimizing internal processes through reforms. By designing environmentally friendly products and actively engaging in community communication, firms can enhance the performance of sustainable process management in response to stakeholder pressure (Shafique et al., 2017). When stakeholder pressure is low, firms should prioritize the development of sustainable supply management. This involves strengthening relationships with suppliers and engaging in external SSCM practices. Additionally, firms should recognize the importance of external resources for internal management and performance improvement (Wolf, 2014). By selecting suppliers with resource and capability advantages, building trust through complementary advantages or strategic cooperation agreements (Dash et al., 2018), and utilizing supplier resources for internal process optimization, firms can enhance resource utilization efficiency, address waste-related issues, and promote the development of sustainable process management, ultimately improve firm performance (Meixell & Luoma, 2015).

While this study makes significant contributions, there are limitations that warrant further research. First, this study relies on cross-sectional data from manufacturing firms in China, providing a static perspective on the relationships between variables. However, the use of cross-sectional data has significant limitations, such as the lack of a temporal dimension to reveal dynamics and causality, potential homogeneity bias leading to insufficient sample representativeness, difficulty in directly interpreting causal relationships, and potential endogenous issues(Cummings, 2018). Although we have employed various methods to mitigate these effects, longitudinal research methods should be considered as a more suitable alternative (Maier et al., 2023). Future research could collect time-series data to explore how the relationships between variables change over time in response to evolving environments and SSCM practices. Second, the study does not classify stakeholder pressure based on different economic or social attributes. Future research could investigate the diverse effects of different types of stakeholder pressure. Lastly, additional environmental variables should be considered. This paper focused solely on stakeholder pressure without accounting for risk factors. In today’s world, geopolitical issues, natural disasters, and unexpected events increasingly impact demand, technology, and supply, posing significant risks to supply chains and firms (Priya et al., 2021). Future studies should incorporate risk and other contextual factors into the research model to further enrich and expand the findings and provide stronger practical insights.

Data availability

Our data originates from corporate research. The rationale for not making it publicly available is twofold: 1. The dataset contains proprietary information that companies have not authorized for public release. 2. The data are currently being used in an ongoing research initiative that is still in progress. Howevre, summary statistics can be provided by the corresponding author upon receipt of a reasonable and justified request.

References

Abdallah AB, Al-Ghwayeen WS (2020) Green supply chain management and business performance: The mediating roles of environmental and operational performances. Business Process Management Journal 26:489–512

Adomako S, Tran MD (2022) Environmental collaboration, responsible innovation, and firm performance: The moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Business Strategy Environment 31:1695–1740

Ageron B, Gunasekaran A, Spalanzani A (2012) Sustainable supply management: An empirical study. International journal production economics 140:168–182

Agyabeng-Mensah Y, Afum E, Ahenkorah E (2020) Exploring financial performance and green logistics management practices: examining the mediating influences of market, environmental and social performances. Journal cleaner production 258:120613

Ahmed KS, Shujaat MM, Simonov K, Imran ZS, Alam KSH (2020) Social sustainable supply chains in the food industry: A perspective of an emerging economy. Corporate Social Responsibility Environmental Management 28:404–418

Amjad M, Jamil A, Ehsan A (2017) The impact of organizational motives on their performance with mediating effect of sustainable supply chain management. International Journal Business Society 18:585–602

Awan U, Kraslawski A, Huiskonen J (2017) Understanding the relationship between stakeholder pressure and sustainability performance in manufacturing firms in Pakistan. Procedia Manufacturing 11:768–777

Balon V (2020) Green supply chain management: pressures, practices, and performance—An integrative literature review. Business Strategy Development 3:226–244

Becker J-M, Proksch D, Ringle CM (2022) Revisiting Gaussian copulas to handle endogenous regressors. Journal academy marketing science 50:46–66

Beske P, Seuring S (2014) Putting sustainability into supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: International Journal 19:322–331

Bhatia, M, Jain, A (2013) Green marketing: A study of consumer perception and preferences in India. Electronic Green Journal 1

Busse C (2016) Doing well by doing good? The self‐interest of buying firms and sustainable supply chain management. Journal Supply Chain Management 52:28–47

Busse C, Schleper MC, Niu M, Wagner SM (2016) Supplier development for sustainability: contextual barriers in global supply chains. International Journal Physical Distribution Logistics Management 42:442–468

Clarkson ME (1995) A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy management review 20:92–117

Cummings, CL (2018) Cross-sectional design. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc. Retrieved

Dai J, Xie L, Chu Z (2021) Developing sustainable supply chain management: The interplay of institutional pressures and sustainability capabilities. Sustainable Production Consumption 28:254–268

Dash A, Das RK, Tripathy S, Nayak S (2018) Supply chain coordination voyage towards supplier relationship management: a critical review. International Journal Procurement Management 11:586–607

Feng M, Yu W, Wang X, Wong CY, Xu M, Xiao Z (2018) Green supply chain management and financial performance: The mediating roles of operational and environmental performance. Business Strategy Environment 27:811–824

Flynn BB, Huo B, Zhao X (2010) The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. Journal Operations Management 28:58–71

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal marketing research 18:39–50

Frohlich MT (2002) Techniques for improving response rates in OM survey research. Journal Operations Management 20:53–62

Furaiji F, Łatuszyńska M, Wawrzyniak A (2012) An empirical study of the factors influencing consumer behaviour in the electric appliances market. Contemporary Economics 6:76–86

Gavronski I, Klassen RD, Vachon S, do, Nascimento LFM (2011) A resource-based view of green supply management. transportation research part E: logistics transportation review 47:872–885

Genovese A, Koh SL, Acquaye A (2013) Energy efficiency retrofitting services supply chains: Evidence about stakeholders and configurations from the Yorskhire and Humber region case. International journal production economics 144:20–43

Gopal P, Thakkar J (2016) Sustainable supply chain practices: an empirical investigation on Indian automobile industry. Production Planning Control 27:49–64

Green K, Morton B, New S (1998) Green purchasing and supply policies: do they improve companies’ environmental performance? Supply Chain Management: International Journal 3:89–95

Green KW, Toms LC, Clark J (2015) Impact of market orientation on environmental sustainability strategy. Management Research Review 38:217–238

Gualandris J, Kalchschmidt M (2014) Customer pressure and innovativeness: Their role in sustainable supply chain management. Journal Purchasing Supply Management 20:92–103

Gualandris J, Kalchschmidt M (2016) Developing environmental and social performance: the role of suppliers’ sustainability and buyer–supplier trust. International Journal Production Research 54:2470–2486

Gualandris J, Klassen RD, Vachon S, Kalchschmidt M (2015) Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. Journal Operations Management 38:1–13

Hahn, T, Figge, F, Pinkse, J, Preuss, L (2010) Trade‐offs in corporate sustainability: You can’t have your cake and eat it. Wiley Online Library, pp. 217–229

Haleem F, Farooq S, Cheng Y, Waehrens BV (2022) Sustainable management practices and stakeholder pressure: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 14:1967

Hart SL (1995) A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy management review 20:986–1014

Hart SL, Dowell G (2011) Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal Management 37:1464–1479

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal academy marketing science 43:115–135

Hult GTM, Hair Jr JF, Proksch D, Sarstedt M, Pinkwart A, Ringle CM (2018) Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. Journal International Marketing 26:1–21

Hyatt DG, Berente N (2017) Substantive or symbolic environmental strategies? Effects of external and internal normative stakeholder pressures. Business Strategy Environment 26:1212–1234

Jagriti S, Kumar PK, Anil K, Farheen N, Sunil L (2022) Drivers, barriers and practices of net zero economy: An exploratory knowledge based supply chain multi-stakeholder perspective framework. Operations Management Research 16:1059–1090

Kerlinger FN, Lee HB, Bhanthumnavin D (2000) Foundations of behavioral research: the most sustainable popular textbook by Kerlinger & Lee (2000). Journal Social Development 13:131–144

Lambert DM, Robeson JF, Stock JR (1978) An appraisal of the integrated physical distribution management concept. International Journal Physical Distribution Materials Management 9:74–88

Maier, C, Thatcher, JB, Grover, V, Dwivedi, YK (2023) Cross-sectional research: a critical perspective, use cases, and recommendations for IS research. Elsevier, p. 102625

Marty J, Martin C, Ageron B (2023) Making supply chains more sustainable through customer and consumer engagement: the case of rare metals. Corporate Social Responsibility Environmental Management 31:895–908

Meixell MJ, Luoma P (2015) Stakeholder pressure in sustainable supply chain management. Management 45:69–89

Murtagh, F, Heck, A (2012) Multivariate data analysis. Springer Science & Business Media

Nadarajah D, Kadir SLSA (2014) A review of the importance of business process management in achieving sustainable competitive advantage. TQM journal 26:522–531

Park-Poaps H, Rees K (2010) Stakeholder forces of socially responsible supply chain management orientation. Journal Business Ethics 92:305–322

Parmar BL, Freeman RE, Harrison JS, Wicks AC, Purnell L, De Colle S (2010) Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Academy Management Annals 4:403–445

Paulraj A, Chen IJ, Blome C (2017) Motives and performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management practices: A multi-theoretical perspective. Journal Business Ethics 145:239–258

Phillips R, Caldwell CB (2005) Value chain responsibility: A farewell to arm’s length. Business Society Review 110:345–370

Priya SS, Cuce E, Sudhakar K (2021) A perspective of COVID 19 impact on global economy, energy and environment. International Journal Sustainable Engineering 14:1290–1305

Sánchez-Flores RB, Cruz-Sotelo SE, Ojeda-Benitez S, Ramírez-Barreto ME (2020) Sustainable supply chain management—A literature review on emerging economies. Sustainability 12:6972

Sanders NR, Premus R (2005) Modeling the relationship between firm IT capability, collaboration, and performance. Journal Business Logistics 26:1–23

Sarfraz M, Khawaja KF, Han H, Ariza-Montes A, Arjona-Fuentes JM (2023) Sustainable supply chain, digital transformation, and blockchain technology adoption in the tourism sector. Humanities Social Sciences Communications 10:1–13

Sarkis J, Gonzalez‐Torre P, Adenso‐Diaz B (2010) Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: the mediating effect of training. Journal Operations Management 28:163–176

School of Management, PdM, Facultad de Posgrados, UdLA-E, School of Management, PdM, School of Management, PdM (2019) Sustainability in multiple stages of the food supply chain in Italy: practices, performance and reputation. Operations Management Research 12:40–61

Shafique M, Asghar M, Rahman H (2017) The impact of green supply chain management practices on performance: Moderating role of institutional pressure with mediating effect of green innovation. Business, Management Economics Engineering 15:91–108

Shi VG, Koh SL, Baldwin J, Cucchiella F (2012) Natural resource based green supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: International Journal 17:54–67

Shibin K, Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Hazen B, Roubaud D, Gupta S, Foropon C (2020) Examining sustainable supply chain management of SMEs using resource based view and institutional theory. Annals Operations Research 290:301–326

Siems E, Seuring S, Schilling L (2023) Stakeholder roles in sustainable supply chain management: a literature review. Journal Business Economics 93:747–775

Sutherland JW, Richter JS, Hutchins MJ, Dornfeld D, Dzombak R, Mangold J, Robinson S, Hauschild MZ, Bonou A, Schönsleben P (2016) The role of manufacturing in affecting the social dimension of sustainability. CIRP Annals 65:689–712

Swink M, Song M (2007) Effects of marketing-manufacturing integration on new product development time and competitive advantage. Journal Operations Management 25:203–217

Toke LK, Kalpande SD (2024) Critical analysis of green accounting and reporting practises and its implication in the context of Indian automobile industry. Environment, Development Sustainability 26:3243–3268

Truant, E, Borlatto, E, Crocco, E, Sahore, N (2023) Environmental, social and governance issues in supply chains. A systematic review for business strategy. Journal of cleaner production, 140024

Vachon S (2007) Green supply chain practices and the selection of environmental technologies. International Journal Production Research 45:4357–4379

Vachon S, Klassen RD (2006) Extending green practices across the supply chain: the impact of upstream and downstream integration. International Journal Operations Production Management 26:795–821

Vachon S, Klassen RD (2008) Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. International journal production economics 111:299–315

Vom Brocke, J, Seidel, S, Recker, J, (2012) Green business process management: towards the sustainable enterprise. Springer Science & Business Media

Wang Z, Wang Q, Zhang S, Zhao X (2018) Effects of customer and cost drivers on green supply chain management practices and environmental performance. Journal cleaner production 189:673–682

Wernerfelt B (1984) A resource‐based view of the firm. Strategic management journal 5:171–180

Wiredu J, Yang Q, Sampene AK, Gyamfi BA, Asongu SA (2024) The effect of green supply chain management practices on corporate environmental performance: does supply chain competitive advantage matter? Business Strategy Environment 33:2578–2599

Wolf J (2014) The relationship between sustainable supply chain management, stakeholder pressure and corporate sustainability performance. Journal Business Ethics 119:317–328

Wu W, Shi J, Liu Y (2024) The impact of corporate social responsibility in technological innovation on sustainable competitive performance. Humanities Social Sciences Communications 11:1–13

Yadav S, Choi T-M, Kumar A, Luthra S, Naz F (2023) A meta-analysis of sustainable supply chain practices and performance: the moderating roles of type of economy and innovation. International Journal Operations Production Management 43:802–845

Yu W, Ramanathan R (2015) An empirical examination of stakeholder pressures, green operations practices and environmental performance. International Journal Production Research 53:6390–6407

Yu W, Chavez R, Feng M, Wiengarten F (2014) Integrated green supply chain management and operational performance. Supply Chain Management: International Journal 19:683–696

Zhao X, Lynch Jr JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal consumer research 37:197–206

Zhu Q, Sarkis J, Lai K-H (2012) Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. International Journal Production Research 50:1377–1394

Zhu, Q, Sarkis, J, Lai, K-H, (2013). Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 19, 106–117

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2020R033), Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (No. 2024ZC-YBXM-056), Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (No. 22YJC630173), and Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 72372128).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xuefei Li.The corresponding author, Yi Li, is primarily responsible for communication and financial support. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The survey conducted in this study adhered to the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. There research procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xidian University. (Date:2023.4.5/No. XDU-ECMS-2023-012).

Informed consent

All participants received an interview request and a description of the study via email. Informed consent was obtained orally from all respondents prior to the interviews. The participants were informed about the aims of the research and how their responses will be used anonymously. They were also informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any point, and given the option to review the transcripts after the interviews to adjust/revise as they saw fit.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Li, Y., Li, G. et al. Sustainable supply chain management practices and performance: The moderating effect of stakeholder pressure. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04676-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04676-4

This article is cited by

-

What fuels stakeholder impact on sustainability: a fuzzy DEMATEL analysis of the leather supply chain ecosystem

Discover Sustainability (2025)